ABSTRACT

The present review examines whether commonalities and differences can be detected in the content of eudaimonic entertainment. We focused on two features: the fundamental human needs that were threatened, and the specific virtues that were portrayed. The results showed that the examined materials often included a combination of portrayals of threats to the fundamental human needs for safety, health and relatedness, and portrayals of the virtue of humanity, like love and kindness. Two subcategories could be distinguished in the materials, one in which the focus is on the portrayal of virtue as an answer to threatened needs, and one in which the focus is on the portrayal of threatened needs in which characters struggle even though they also have virtue.

Over the last decade, the research area of eudaimonic entertainment has grown rapidly. More and more research is being done on the nature and effects of eudaimonic entertainment (e.g. Janicke & Oliver, Citation2017; Krämer et al., Citation2019; Slater et al., Citation2018). In this research area, a wide variety of entertainment content is used, ranging from YouTube videos about acts of human kindness, such as paying it forward (Neubaum et al., Citation2020), a shortened version of the film Hotel Rwanda in which a hotel manager deals with the consequences of civil war in Rwanda (Wirth et al., Citation2012) to a clip from the animated film Up that shows a long and loving marriage that ends in loss (Slater et al., Citation2018). This wide variety in materials used raises the question what they have in common, i.e. whether systematic commonalities and potential differences can be detected across eudaimonic content.

To answer this question, we set out to do a review of the materials that are used in eudaimonic entertainment research. By analyzing the similarities and differences between the materials in these studies, we aim to uncover features that are common in eudaimonic entertainment according to the researchers in this field and features that distinguish between different subcategories of eudaimonic entertainment. Specifically, we focus on two central features on the basis of previous theorizing in the literature. One aspect is that eudaimonic entertainment is expected to show fundamental human needs that are threatened (Slater et al., Citation2018). Another key aspect assumed of eudaimonic entertainment is the specific virtues that are portrayed (Oliver & Bartsch, Citation2011). By reviewing the materials used in eudaimonic entertainment research on these features, we synthesize the extant research with a focus on content which can, in turn, further inform theory on eudaimonic entertainment and the design of empirical studies in this field.

Eudaimonic entertainment

The concept of eudaimonic entertainment is based on notions of eudaimonic happiness, which can be traced back as far as Aristotle (Citation1931; Oliver et al., Citation2018; Janicke-Bowles et al., Citation2021). It refers to individuals living a life in which their personal potentials are fulfilled, i.e. to self-realization (Waterman, Citation2008). Eudaimonic happiness involves positive psychological functioning such as having a purpose in life, being able to grow personally, accepting oneself, and having positive relations with others (Hofer & Rieger, Citation2019). It is also called psychological well-being and it is often contrasted to hedonic happiness or subjective well-being, which is derived from maximizing pleasure and minimizing pain. Instead of short-term, pleasure-oriented hedonic happiness, eudaimonic happiness is related to long-term fulfillment of human potential (Ryff & Singer, Citation2008). As such, eudaimonic happiness can be described as flourishing as a human being and living a fulfilled life (Oliver & Bartsch, Citation2011).

Eudaimonic entertainment can contribute to eudaimonic happiness (Hofer & Rieger, Citation2019; Janicke-Bowles et al., Citation2021). Foundations for this conception of entertainment were laid when it became clear that traditional ideas of entertainment as optimizing pleasure and amusement do not apply to all cases of entertainment, such as sad films (Oliver, Citation2008; Schramm & Wirth, Citation2008). Instead, such entertainment that makes us reflect on the meaning of life, gives us greater understanding of the human condition or lets us emotionally connect to others may increase our flourishing in life. Another term that is often used for this type of entertainment is meaningful entertainment (Hofer, Citation2013; Oliver & Bartsch, Citation2011).

Eudaimonic or meaningful entertainment is generally conceptualized based on responses to entertainment. Oliver et al. (Citation2018, p. 381) for instance note that audience reactions are central to defining meaningful media; it refers to content that elicits responses that recipients identify as meaningful. Three dimensions of such eudaimonic responses are identified: mixed affect in which the viewer feels both joy and sadness at the same time, cognitive effort in which the viewer engages in reflection prompted by the entertainment, and fulfillment of intrinsic needs in which viewers’ human needs like autonomy and relatedness are satisfied (Oliver et al., Citation2018). By and large, empirical research supports these three dimensions in receiver responses, although operationalizations across studies differ (Janicke-Bowles et al., Citation2021; Raney et al., Citation2020).

However, this user-based conceptualization of eudaimonic entertainment does not mean that no further insight can be gained into the content of entertainment that is eudaimonic for most viewers. In fact, although individual responses may vary, it is possible to find tendencies in which content is generally regarded as meaningful (Oliver et al., Citation2012; Oliver & Hartmann, Citation2010). This means that because of its basis in responses, all kind of content may be meaningful for some viewers, but specific content is found meaningful by most viewers. For example, scholars have noted that films that were identified as meaningful by viewers often included similar portrayals, such as portrayals of altruistic values (Oliver et al., Citation2012). Likewise, others have remarked that some content is more likely to call up meaningfulness (Oliver & Hartmann, Citation2010; see also Bartsch et al., Citation2016). Building on this reasoning, this review focuses on entertainment content that is eudaimonic in this sense, i.e. it is expected to elicit meaningful responses in most viewers. By focusing on features that are likely eudaimonic for most viewers, we aim to detect general patterns, which can inform future research about this type of entertainment.

Eudaimonic entertainment content

A few researchers describe content that they consider typical for eudaimonic entertainment. Oliver and Bartsch (Citation2011, p. 31) for instance identify entertainment that focuses on human moral virtue as eudaimonic. In addition, Slater et al. (Citation2018, p. 82) describe eudaimonic narrative as showing crucial life events, such as loss and other life transitions, highlighting human vulnerability and the temporary quality of one’s stay on earth. Thus, while acknowledging that eudaimonic entertainment is based on meaningful responses, researchers also have a notion of content that is generally eudaimonic. In addition to explicit descriptions of this content which only a few researchers give, these notions are also implicit in the materials that researchers use to examine eudaiomonic entertainment, because they select content that they consider eudaimonic. This review gives an overview of what is considered eudaimonic entertainment in this field by analyzing the materials that are used in eudaimonic entertainment research.

Starting from the descriptions of eudaimonic entertainment in the literature, we specifically focus on two features in our review. First, as eudaimonic stories are described as including human vulnerability, transience and loss (Cohen et al., Citation2020; Slater et al., Citation2018), we expect that they often involve threats to fundamental needs of characters, like the need for safety and the need for relatedness (Maslow, Citation1943, Citation1968). For example, when a protagonist loses a loved one, this is a threat to their basic need for relatedness. Such portrayals of threatened needs show that things of value are transient and lost in the course of time (Cohen et al., Citation2020). In the present study, we review which specific needs are threatened in the materials of previous eudaimonic entertainment research and identify general patterns.

Second, we look at virtues that are portrayed in eudaimonic content, as virtue is also considered central to eudaimonic entertainment (Oliver & Bartsch, Citation2011). Several virtues are mentioned by researchers such as persistence, care and generosity (Bartsch & Oliver, Citation2016; Oliver et al., Citation2017). These can be categorized as the main human virtues of courage and humanity (Peterson & Seligman, Citation2004). For example, a protagonist helping someone or sharing with others portrays the virtue of humanity. Other virtues are justice, temperance, wisdom and transcendence. This review examines which specific virtues are portrayed in the content used in eudaimonic entertainment research and analyze general patterns.

To summarize, the focus of this review is on the content of eudaimonic entertainment. It is a descriptive review of the materials that have been used in eudaimonic entertainment research. We create an overview of the content of this entertainment to gain more insight into the features of eudaimonic entertainment. By analyzing the similarities in the content, we can find common features in eudaimonic entertainment as it is used in this research area. By inspecting the differences in the content, we can uncover different subcategories of eudaimonic entertainment. An important contribution of this review is to reveal shared notions of typical content of eudaimonic entertainment. By showing whether, and if so which threatened needs and human virtue are portrayed in most materials, it becomes clear what is regarded as eudaimonic entertainment content by the experts in this research field and whether these accord with the descriptions given in the literature.

The research questions that guide this review are:

RQ1: Which common features can be distinguished in the content of the materials of eudaimonic entertainment research?

RQ2: Which subcategories can be identified in the content of the materials of eudaimonic entertainment research?

Method

Search strategy

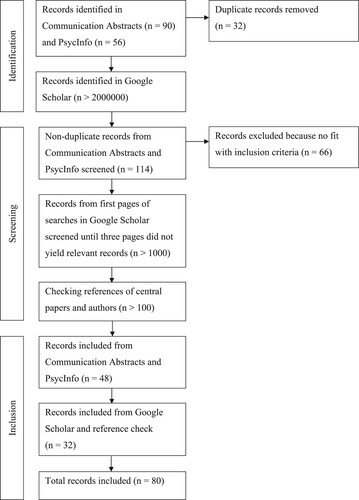

We conducted an extensive literature search of empirical studies on the topic of eudaimonic entertainment. The databases Communication Abstracts and PsycInfo were searched because communication and psychology are the disciplines in which most research on eudaimonic entertainment is being done. In addition, Google Scholar was used because it yielded multiple relevant studies that were not present in the searches in Communication Abstracts and PsycInfo. We used the following combinations of keywords to search the full text in all databases: eudaimonic and entertainment, eudaimonic and narrative, eudaimonic and media, meaningful and entertainment, and meaningful and media (the combination meaningful and narrative yielded no relevant records). We used these keywords to ensure that papers were found in which entertainment is studied that researchers identify as eudaimonic, of which meaningful is used as a synonym on the basis of the conceptualization of eudaimonic entertainment by Oliver et al. (Citation2018).

The combined searches in Communication Abstracts and PsycInfo resulted in a total of 114 non-duplicate documents, which were perused on whether they fit the selection criteria. Google Scholar provided too many hits to look at each document individually (more than 2 million documents for meaningful media). As Google Scholar sorts documents by relevance, we checked the first pages of search results, until 3 pages did not yield any more documents that fit the selection criteria. In addition, we checked reference lists of central theoretical and empirical papers on eudaimonic entertainment for relevant references. Also, we searched for articles that referred to these papers with the function ‘cited by.’ Finally, we checked whether authors of which multiple papers had appeared in the search had other papers on this topic.

Selection criteria

We used several criteria to decide whether or not to include a document in the review. First, to ensure that the paper addressed eudaimonic entertainment, it needed to report on a study about media entertainment in which the term ‘eudaimonic’ or ‘meaningful’ was used to refer to the entertainment that was studied. This term could be used to refer to the content of the entertainment and/or to the recipients’ responses to the entertainment. Some studies referred to eudaimonic motivations, which are strictly speaking not responses to entertainment as they precede exposure, but these were also taken to indicate that the study was about eudaimonic entertainment and thus included. Second, it was an empirical study in which data was collected about recipients’ responses to entertainment and/or about features of the entertainment. All types of measurement were allowed, such as self-report and physiological measures, as well as qualitative studies. Third, it was a study about non-interactive audiovisual entertainment. Thus, studies about other media like written narratives were excluded. In addition, we excluded papers that were exclusively about interactive media, like games, because these are not the focus of this review. This left many types of audiovisual entertainment to be included, such as (clips of) films, television shows and YouTube videos. Finally, only papers published in peer-reviewed journals and dissertations were included in this review to ensure the quality of the studies and only papers published in English were included based on limitations in the languages spoken by the researchers.

A total of 80 papers was selected based on these criteria (see flowchart of selection process in ), which were published between 2008 and 2020. These papers reported on 102 (non-duplicate) empirical studies on eudaimonic entertainment. Many of the studies were experiments (n = 57). In 48 experiments, participants were exposed to videos in different conditions, such as a eudaimonic vs. a non-eudaimonic condition (e.g. Slater et al., Citation2019) or a eudaimonic video with a happy ending vs. a sad ending (e.g. Wirth et al., Citation2012, study 1). In 9 experiments, participants were randomly assigned to report on different types of audiovisual entertainment they had watched before, such as a particularly meaningful film vs. a particularly pleasurable film (e.g. Oliver et al., Citation2012). In addition, many studies were surveys (n = 40). In 11 surveys, all participants were exposed to the same entertainment stimulus, like a shortened version of a film, and then answered questions about this stimulus (e.g. Wirth et al., Citation2012, study 2). In 29 surveys, all participants were asked to report on entertainment they had watched before, such as their favorite movie (e.g. Janicke & Ramasubramanian, Citation2017). Finally, 2 studies were content analyses and 3 studies used a qualitative method.

Analysis

In the present paper, all selected studies were reviewed for information regarding the content of eudaimonic entertainment. Not all studies used the terms ‘eudaimonic’ or ‘meaningful’ to refer to the content of entertainment, because these terms may also refer to entertainment responses or motivations. Nonetheless, we assumed that also in these studies, the researchers used audiovisual materials or asked questions about content that they consider eudaimonic. That is, the researchers probably selected content that they expected to call up in most viewers the eudaimonic responses they were interested in. Thus, a starting point of this review is that the materials that were used in the selected studies (unless they belong to a control condition that was explicitly stated to be non-eudaimonic) are eudaimonic according to the researchers. The results of this review can therefore be said to reflect the collective intuitions about eudaimonic content of the experts in the field of eudaimonic entertainment research.

The selected studies varied in the extent to which they provided information relevant for our research questions. Many of the studies included audiovisual materials to which the participants were exposed. We collected the descriptions that were given of these materials. As these descriptions are selections of what is shown in the video, especially when it is a longer video, it is possible that not all instances of threatened needs or virtue that were present in the materials (but not in the descriptions) were analyzed. However, we assumed that the researchers selected the elements that they judged to be most relevant in their description and thus our analysis gives an account of the ideas of researchers of what is important in eudaimonic entertainment. For some studies, links were provided to YouTube or the Open Science framework on which the videos could be viewed. In some other studies, descriptions were not sufficient to analyze whether threatened needs or virtue were portrayed. In those cases, we used descriptions on the internet movie database (imdb.com) to get an idea of the main content, but only in so far as it was plausible that this content was present in the video that was shown (e.g. trailer, scene). In experiments that explicitly stated to compare a eudaimonic condition to another (e.g. hedonic) condition, only the materials for the eudaimonic condition were included in the analysis. In addition, studies that did not expose participants to entertainment, often did include questions about specific entertainment and can in this way also provide information about the content of eudaimonic entertainment. For instance, by descriptions given by participants of meaningful films they recollected or by film titles given by researchers as eudaimonic. This information was analyzed separately.

Of the descriptions of study materials, we did a qualitative content analysis, based on the principles of thematic analysis (TA). TA is a method for identifying patterns of what is common across a dataset (Braun & Clarke, Citation2012). Although multiple patterns can be discerned in any dataset, TA is guided by what is relevant to the specific topic(s) under investigation (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). In the present analysis, these topics were the portrayals of threatened needs and human virtue in the materials, based on the descriptions of eudaimonic content in the literature (Oliver & Bartsch, Citation2011; Slater et al., Citation2019). The threat to human needs was analyzed based on Maslow’s (Citation1943, Citation1968) basic needs hierarchy, as this provided the most fitting and encompassing classification of human needs in the present dataset. The 5 fundamental needs in this hierarchy are: Physiological needs, which refer to conditions necessary for the body to survive such as food and drink, but also sufficient sleep and general health (Taormina & Gao, Citation2013). Safety needs, which refer to being protected from things that could harm us such as crime, war, natural catastrophes, and disease, but also to the need for financial security such as insurance (Maslow, Citation1943). Belongingness or relatedness needs, which refer to the longing for love and affectionate relations to others such as a partner, friends or family members (Maslow, Citation1968). Esteem needs, which refer both to self-esteem or seeing yourself as a competent and worthy person and to esteem from others or being respected and having prestige (Maslow, Citation1943, Citation1968). Self-actualization needs, which refer to the desire for self-fulfillment or to become what one truly is (Taormina & Gao, Citation2013). Because health concerns are present in both physiological (the need for a healthy body) and safety needs (the need to be safe from disease), the need for health was categorized separately.

The portrayal of human virtue was categorized on the basis of the core human virtues identified by Peterson and Seligman (Citation2004). They distinguish 6 human virtues that comprise different character strengths, which are the following: Wisdom, which refers to cognitive strengths that entail the acquisition and use of knowledge, such as curiosity and creativity. Courage, which refers to emotional strengths that involve the exercise of will to accomplish goals in the face of external or internal opposition, like bravery and persistence. Humanity, which refers to interpersonal strengths that involve tending and befriending others, like love and kindness. Justice, which refers to civic strengths that underlie healthy community life, like fairness. Temperance, which refers to strengths that protect against excess, like modesty. Transcendence, which refers to strengths that forge connections to the larger universe and provide meaning, like appreciation of beauty (Peterson & Seligman, Citation2004, pp. 29–30). In accordance with principles of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006), categories were discussed with two independent researchers, which then informed the refinement of themes, their definition and naming. This refinement led to the inclusion of the category non-virtuous behavior or behavior that goes against one or more of the virtues, like harming or killing others. On the basis of this analysis, we uncovered similarities in the content indicating common features, and identified differences indicating subcategories.

Results

In , an overview is given of the materials that participants watched in the selected studies that exposed participants to entertainment. The descriptions of the materials and the categorizations on the two features, fundamental human needs that are threatened and virtues that are portrayed, are presented in the table.

Table 1. Descriptions of materials used in studies that exposed participants to entertainment.

Portrayals of threatened needs: characters struggling

Almost all of the materials contained portrayals of threats to fundamental needs of characters. For instance, Wirth et al. (Citation2012) used a shortened version of the film Hotel Rwanda, in which a hotel manager deals with the consequences of civil war and genocide in Rwanda in 1994, which is a threat to the human need for safety. Additionally, one of the clips used by Slater et al. (Citation2019) from the film Stand by Me showed the protagonist struggling with the death of his older brother, which presents a threat to the need for relatedness shared by all humans. These portrayals of threatened needs show characters dealing with negative events and circumstances, or in other words they show characters struggling. In these portrayals, it is shown what it is like for the character(s) to experience adversity and misfortune.

As can be seen in , needs that were threatened most often in the materials were safety needs. Typical examples of this kind of struggling were being in a war like the civil war in Rwanda in Hotel Rwanda (Wirth et al., Citation2012), or living in other negative settings like a gang environment in The Wire (Bailey & Ivory, Citation2018) and an immigrant detention center in Illégal (Angulo-Brunet & Soto-Sanfiel, Citation2020). In addition, the fundamental need for relatedness was threatened in approximately a quarter of the categorized descriptions of struggling. This was often the loss of a loved one, such as a spouse in the animation film Up (Slater et al., Citation2019) or a child in the film Mystic River (Khoo & Oliver, Citation2013). Other threats to relatedness needs include problematic relations between family members, such as between parents and children in the television show Supernanny (Tsay-Vogel & Krakowiak, Citation2016). In a similar number of portrayals, the need for health was threatened. In many of these portrayals, characters suffered from a potentially fatal disease, like an aggressive form of cancer in the film One Week (Rieger & Hofer, Citation2017) or characters struggled with a disability, like an athlete with a prosthetic leg in a television spot about the Paralympics (Bartsch et al., Citation2018). Finally, a threat to the human need for esteem was identified in a few portrayals, such as a character who was bullied in the tv show Freaks and Geeks (Bailey & Ivory, Citation2018). In sum, in portrayals of struggling, needs that were threatened most often were the needs for safety, relatedness and health. Other needs like the needs for esteem and self-actualization were not threatened often in the descriptions of eudaimonic entertainment.

Portrayals of virtue: characters acting in a morally good way

The analysis revealed that many of the materials used in eudaimonic entertainment research contained portrayals of virtue, showing characters who behave in a morally good way. In these portrayals, characters do good deeds and act in a ‘just’ way. For instance, Neubaum et al. (Citation2020) used a series of videos showing human kindness, such as a chain reaction of people observing prosocial acts and afterwards doing good deeds themselves. In addition, several studies (e.g. Janicke et al., Citation2018; Slater et al., Citation2019) used a video in which a boy who needs medicine for his mother is helped by a man who pays it for him. Then 30 years later, when the boy has become a doctor, he repays the favor by covering the man’s medical expenses.

As becomes clear in , the virtue that was by far most often portrayed in the materials of the studies was the virtue of humanity, which includes love and kindness. A lot of these portrayals showed love for family members, such as the self-sacrifice of a mother for her son in Dancer in the Dark (Hofer et al., Citation2014) and a brother spraying a graffiti for his sister to see from her bedroom (Clayton et al., Citation2019), and other acts of kindness, such as helping each other pay medical expenses in the video used by multiple researchers (e.g. Janicke et al., Citation2018; Slater et al., Citation2019), and including isolated others in social activities like having lunch (Jang et al., Citation2019). Thus, the virtue that is shown most often is humanity, like helping and giving to others. Other virtues that were portrayed in only a few of the materials were courage, like athletes showing persistence and willpower in the spots for the Paralympics (Bartsch et al., Citation2018), and justice, like a coach’s speech about the value of winning fairly in Cool Runnings (Das et al., Citation2017).

Next to portrayals of virtue, approximately a quarter of the categorized descriptions included portrayals of non-virtuous behavior as well. This ranged from minor offenses like stealing a jacket in the film Red Jacket (Bartsch et al., Citation2014), through larger transgressions like falsely accusing someone of rape in the film Atonement (Knobloch-Westerwick et al., Citation2013) to major crimes like killing an innocent man in the film Mystic River (Khoo & Oliver, Citation2013). This means that portrayals of virtue are not the only characteristic of eudaimonic entertainment that is used in research, as non-virtuous portrayals are also regularly present.

Juxtaposition of threatened needs and virtue

Portrayals of virtue often occur together with portrayals of threatened needs. For instance, a story used by Slater et al. (Citation2019) features a disabled middle school student, which presents a threat to his need for health, and he is helped to score a touchdown by his school’s football team, which shows kindness as an act of the virtue of humanity. Similarly, Neubaum et al. (Citation2020) included a video of a police man in Manhattan who gave his shoes to a homeless man, which combines kindness and a threat to the need for safety. These examples show that being kind and loving towards people who are struggling as their needs are threatened is a recurring theme in entertainment content seen as eudaimonic. Also, the character who is struggling may show kindness towards others. Hofer (Citation2013) used a story of a woman with incurable cancer who starts to arrange for the lives of her husband and two daughters after she will die and records tapes telling them she loves them. Other virtues may also be combined with portrayals of struggling, like in the video used by Clayton et al. (Citation2019) of a former child soldier who was taken from his mother to fight in the war, but when he was freed he showed perseverance in getting an education and eventually became a lawyer, thus portraying the virtue of courage. In sum, portrayals of virtue often go together with portrayals of threatened needs. As humanity is the virtue shown in most of the portrayals, the threats to different needs mostly go together with portrayals of humanity.

Focus on virtue over threatened needs

Even though the materials often combine portrayals of virtue and threatened needs, differences can be discerned in the degree to which they focus on one or the other, suggesting different subcategories of eudaimonic entertainment. For instance, the video that was used in several studies (e.g. Janicke et al., Citation2018) about the boy who becomes a doctor and repays the man who helped him, includes both virtue – the boy is helped and later helps the man – and threatened needs – the boy is poor and his mother is ill and the man also becomes ill and can’t pay the hospital bills. However, the focus of the story is on the good deeds done by both the man for the boy and the grown-up boy for the older man. These good deeds alleviate the struggling both go through and thus positive effects of virtue are focused on in this story. This is similar for many other materials in which kindness is central, such as a sister cutting her hair to support her brother going through chemotherapy (Krämer et al., Citation2017) and a football player having lunch with an autistic student who sits alone (Jang et al., Citation2019). In these cases, the struggling with threatened needs – often portrayed first – serves as a contrast by which the good deeds stand out, emphasizing the goodness of the virtue. This can be seen as a subcategory of eudaimonic entertainment in which virtue is portrayed in the presence of struggling.

Focus on threatened needs over virtue

In other materials, the focus is on threatened needs. For instance, the shortened version of Dancer in the Dark used by Hofer et al. (Citation2014) in which an immigrant woman struggles a lot, losing her eyesight, the money she saved up and her freedom, also includes portrayals of virtue as she saves up the money for the love of her son. However, the focus of the story is on the threats to her fundamental needs for safety and health. In this case, the love and sacrifice for her son emphasizes the difficulty of her struggles with these threats. Similarly, Khoo and Oliver (Citation2013) used a shortened version of the film Mystic River, in which an ex-con loves his daughter a lot. When she is murdered, he is grief-stricken. He starts to suspect an old friend of the murder and kills him in revenge. However, it turns out that this is the wrong man and, in the end, the man is also stricken with guilt. Although the love for his daughter could be seen as a portrayal of virtue, the focus of this story clearly is on struggling with the threat to his need for relatedness that is presented by the loss of his daughter. In these cases, characters’ struggling with threatened needs is central. This can be seen as a subcategory of eudaimonic entertainment in which struggling is portrayed in the presence of (some) virtue.

Juxtaposition of virtue and non-virtuous behavior

In most of the materials that included non-virtuous behavior, the characters also show at least some virtue. For instance, the immigrant woman in Dancer in the Dark who sacrifices herself for the love of her son, shoots and kills the man who stole her money. In a different example, the coach of a bobsled team in Cool Runnings tells his team about his own cheating in the past and turns this into a lesson about the value of winning in a fair way (Das et al., Citation2017). The combination of non-virtuous portrayals with portrayals of virtue results in the presence of morally ambiguous characters in the materials of the studies on eudaimonic entertainment. These characters are not only good or bad, but show both morally good and bad behavior (see Krakowiak & Oliver, Citation2012). Typically, morally ambiguous characters occur in the subcategory where the focus is on threatened needs.

Rare portrayals

Some of the studies on eudaimonic entertainment contained content that was only present in a few of the materials. For instance, Krämer et al. (Citation2019) included videos portraying the beauty of the earth, such as beautiful landscapes, and the unity of human kind, such as a video of a man dancing with locals at various places in the world (Krämer et al., Citation2019). These portrayals can be linked to the virtue of transcendence (see Janicke-Bowles et al., Citation2021), because they imply that we are connected to a larger whole (Peterson & Seligman, Citation2004). In the studies that exposed people to eudaimonic entertainment, these portrayals were used by one group of researchers (Krämer et al., Citation2017, Citation2019). These portrayals were the only ones in the materials of eudaimonic entertainment research that did not include threatened needs.

Another portrayal that was rare in the materials can be described as intellectually difficult narratives. For instance, Hall and Zwarun (Citation2012) used a story in which an empty box represents a microcosm of the barren world he lives in and he can replenish this world by placing a flower in it. This story is atypical of the materials examined in this review in that it employs metaphor that viewers need to decode. Thus, it is possible that this is part of eudaimonic entertainment, but it is not a common feature in the materials.

Corroboration from other studies

So far, the analysis has used the materials of studies about eudaimonic entertainment that exposed participants to certain content. However, other studies used questionnaires about specific entertainment, e.g. lists of meaningful films, which show similarities to the materials analyzed above, like the film Schindler’s List (e.g. Bartsch & Hartmann, Citation2017; Hofer, Citation2016; Oliver & Bartsch, Citation2010). This film is set in the second world war that presents threats to the need for safety, and shows the main character saving many Jewish people, which clearly portrays virtue. Other studies had participants name meaningful films, which also resulted in films with similar features, such as The Pursuit of Happyness, in which a father struggles with threats to relatedness and financial safety by a divorce and job problems, but perseveres to ensure a good life for his son (Janicke & Ramasubramanian, Citation2017). In addition, qualitative research that asked participants themes of meaningful films confirmed that the portrayal of virtue was important in meaningful films, such as love, caring, and enduring interpersonal ties (Oliver & Hartmann, Citation2010). Similarly, meaningful films were judged to contain more portrayals of connectedness, love and kindness than pleasurable films (Janicke & Oliver, Citation2017). Also, values found to be important in films participants found meaningful were altruistic values which are related to the virtue of humanity, such as caring for the weak (Oliver et al., Citation2012).

Discussion

The aim of this review was to identify common features and subcategories in the content of eudaimonic entertainment by examining the materials used in previous eudaimonic entertainment research. With regard to RQ1 about common features, the results revealed that the materials often portrayed threats to the fundamental human needs for safety, health and relatedness. Characters struggle with negative circumstances and events, like war, poverty, disease and the loss of loved ones. Virtues that were portrayed in eudaimonic entertainment center around humanity. Characters love and care for each other and they show kindness, like helping and generosity. Some materials contained other threatened needs and other virtues as well, but researchers mainly selected materials with these features as indicative of eudaimonic entertainment. Thus, this review indicates that portrayals of threatened needs for safety, health and relatedness and portrayals of the virtue of humanity are the most common features in eudaimonic entertainment research.

With regard to RQ2 about subcategories, the analysis suggested two main subcategories of eudaimonic entertainment on the basis of the materials used in the studies. One subcategory focuses on portrayals of virtue over threatened needs. These portrayals show good deeds in a context of struggling with threatened needs and present these acts of kindness or love as an answer to struggling, which emphasizes the goodness of the virtue. For instance, a typical portrayal in this subcategory shows kind acts towards people who are ill. The other subcategory focuses on portrayals of threatened needs over virtue. These portrayals show difficult situations for (partially) good people, which emphasizes the difficulty of the situation and events. For instance, a typical portrayal shows characters who commit crimes out of love for others. Both these subcategories are seen as eudaimonic entertainment by researchers in this field.

These findings contribute to the research field in multiple ways. First, it is shown that shared notions of eudaimonic entertainment include both portrayals of threatened needs and portrayals of virtue, thus indicating that the description of eudaimonic entertainment content should combine earlier notions that eudaimonic entertainment deals with human vulnerability, transience and loss (Slater et al., Citation2018) and portrays virtue (Oliver & Bartsch, Citation2011). Our findings further extend previous research by showing that, out of 6 different virtues, the virtue of humanity, i.e. love and kindness, is omnipresent in materials from eudaimonic entertainment research. Although other virtues that are also mentioned in the literature like courage and justice could be discerned in a few of the materials, the virtuous acts that were by far most often shown were love and kindness for others. The finding that researchers (implicitly) regard this the virtue portrayal most typical for eudaimonic entertainment raises the question if the portrayal of other virtues has similar, or lesser potential to evoke eudaimonic experiences. If the virtue of humanity exerts stronger effects, this might point to a link to research on kama muta, the power of love (Janicke-Bowles et al., Citation2021; Zickfeld et al., Citation2019), and thus a narrower conceptualization of eudaimonic media. If the virtue of humanity exerts similar effects to other virtues, this would further strengthen theoretical considerations of eudaimonic experiences. Future research should therefore take the presently observed pattern as a starting point for empirical tests of eudaimonic responses to portrayals of different virtues.

Second, our findings add to the literature by showing that often-threatened needs in previous eudaimonic media research were the basic needs for safety and health. These are lower order needs of which satisfaction is required before further needs come into play (Maslow, Citation1968). The finding that lower order needs played such a pivotal role is striking in the light of previous theorizing about the important role of higher order needs in eudaimonic entertainment (Oliver et al., Citation2018; Wirth et al., Citation2012), like the needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness from Self-Determination Theory (SDT, Ryan et al., Citation2008). Our findings therefore suggest that the relationship between portrayals of threatened needs and fulfillment of viewers’ personal needs is not one-on-one, but rather indirectly triggered by the combination of a basic need with a human virtue. Seeing how characters deal with their needs being threatened plausibly promotes insight into coping with similar situations, and as a result may increase efficacy in viewers, which is a part of the need for competence (Ryan et al., Citation2008). Even portrayals of relatedness, which is also part of SDT may not translate directly to impact on the need for relatedness in the viewer, but rather teach viewers through mechanisms like empathy (Coplan, Citation2004; Tal-Or & Cohen, Citation2015). More generally, portrayals of how characters react to threats to needs in a morally sound way may give viewers who do not face such threats themselves insight into how to live life well, contributing to their needs for growth and self-actualization. As such, the imaginary experience of struggling with threatened needs through watching eudaimonic entertainment may provide an opportunity to vicariously practice with such situations from which viewers can learn and gain insight into life (see Gottschall, Citation2012).

Third, the results of this study add to previous research by providing evidence for a distinction between the subcategory of eudaimonic entertainment that focuses on virtue over struggling and the subcategory that focuses on struggling over virtue. In research on eudaimonic entertainment, this distinction has not been taken into account yet. Nevertheless, findings from studies using materials that focus on virtue may not be comparable to findings from studies with materials that focus on struggling. Thus, this distinction is important in organizing previous as well as future studies. Although the present study did not assess viewer responses, it is plausible that the subcategories identified in this review may trigger different eudaimonic media responses. For example, the subcategory of portrayals that focus on virtue in the presence of struggling may mainly trigger meaningful affective responses (i.e. mixed affect, Oliver et al., Citation2018), because in those cases, the struggling emphasizes the goodness of the virtue and watching others behave in a morally good way elicits such emotions as gratitude and elevation (Haidt, Citation2003). The subcategory of portrayals that focus on struggling in the presence of (some) virtue may be more likely to elicit cognitive responses. These portrayals are typically more complex by showing both morally good and bad behavior, thus showing that even though portrayals of the virtue of humanity are central in notions of eudaimonic entertainment, non-virtuous behavior is also present in a part of the content. This results in the presence of ambiguous characters which behave in both morally good and bad ways (Eden et al., Citation2017; Krakowiak & Oliver, Citation2012). These complex portrayals may be more likely to trigger reflection on the themes in the narrative (see Bartsch et al., Citation2016; Khoo & Oliver, Citation2013). Our findings thus provide a solid basis for future research and empirical tests of the hypothesis that subcategories of eudaimonic content evoke different responses.

The present research focused on needs and virtues, but other features of eudaimonic entertainment may also be influential in eliciting eudaimonic responses in most viewers. For example, the composition of features may be important, e.g. first a portrayal of struggling and then of virtue may be more ‘heart-warming’ than first a portrayal of virtue and then of struggling, but also other elements like the presence of music or an open ending may be influential in the elicitation of eudaimonic responses. Moreover, characteristics of the viewers and their situation are likely to affect eudaimonic responses. For instance, viewers’ personal experience with themes in the movie may increase their perceptions of meaningfulness (see Khoo, Citation2016; Klimmt & Rieger, Citation2021) and limited resources in the real world may motivate viewers to engage with the story world (TEBOTS, Slater et al., Citation2014). Future research should explore how such features interact to produce eudaimonic entertainment experiences.

Limitations and future directions

Limitations of this review include the selection of studies. Even though we attempted to obtain a wide sample by including studies that used the term eudaimonic for entertainment content (e.g. ‘eudaimonic narrative’) as well as studies that used this term for responses to entertainment (e.g. ‘eudaimonic experience’), there were also studies that used other terms which are related to eudaimonic entertainment (e.g. ‘elevating media’) but that did not use the term eudaimonic (e.g. Oliver et al., Citation2015). Future research should specify the distinctions and overlap between these concepts. Furthermore, the description of materials was not always optimal. Sometimes we could not determine which needs were threatened or whether virtue was portrayed. In order to facilitate research into the content of eudaimonic entertainment, researchers should always clearly describe the materials they use.

Additionally, this review addressed non-interactive audiovisual entertainment and thus results of this review cannot be generalized to other media like interactive games or written narratives. Other studies should address eudaimonic entertainment in these media to examine whether content is similar to our findings or not. Also, the review mainly focused on portrayals of threatened needs and human virtue based on descriptions of eudaimonic entertainment. However, other elements like the presence of a moral dilemma, an open ending, music, or cinematographic elements can be explored in further studies. Also, we included only published studies (and dissertations). Perhaps there are unpublished studies that could be added. However, because this review focused on the materials and not on effects, we do not consider this as a large threat to our conclusions. The results present what the main (published) authors in this research field selected as eudaimonic content. Another way to examine the notions of researchers is to interview them. It is an interesting suggestion for further research to compare this to our results.

It should be noted that the approach of this study to eudaimonic entertainment is not the only possible approach. Next to approaches that focus on the satisfaction of intrinsic needs (Rigby & Ryan, Citation2016), research has focused on (re)appraisals, in which viewers evaluate their emotions, which can produce further emotions in complex ways (Bartsch et al., Citation2008; Schramm & Wirth, Citation2008). In addition, research has addressed moral aspects of entertainment by linking responses to moral intuitions in domains such as harm/care and fairness (Tamborini, Citation2011). Nevertheless, the approach of eudaimonic entertainment as eliciting meaningful responses is a general approach that is acknowledged in many studies on this topic.

In addition to the novel subcategories of portraying virtue in a context of struggling and struggling in a context of (ambiguous) virtue, there may be other subcategories of eudaimonic entertainment. For instance, portrayals of the beauty of the earth, that were used in only two of the studies that exposed participants to eudaimonic materials included in this review (Krämer et al., Citation2017, Citation2019), may be related to the virtue of transcendence which is seen as important for a specific form of eudaimonic entertainment (see Janicke-Bowles et al., Citation2021). Content analyses indicate that portrayals of beautiful nature are prevalent in eudaimonic YouTube videos (Dale et al., Citation2017; Rieger & Klimmt, Citation2019). In addition, these studies include other categories like portrayals of art and religious symbols that have not been found in this review. Future research should look for other categories and examine how these are related to eudaimonic responses. Nonetheless, this review has focused on the content of the storylines in eudaimonic entertainment, because most of the materials contained stories, making it likely that elements of the story are relevant for eudaimonic entertainment.

Conclusion

The present review has created an overview of the content of materials used in eudaimonic entertainment research. It has shown that typically, eudaimonic entertainment portrays characters struggling with threatened needs for safety, health or relatedness, combined with the virtue of humanity, like kindness, care and love. This combination either focuses on virtue as an answer to threatened basic needs, or it focuses on struggling with need threats in the presence of (some) virtue.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References (studies included in the review are marked *)

- *Angulo-Brunet, A., & Soto-Sanfiel, M. T. (2020). Understanding appreciation among German, Italian and Spanish teenagers. Communications: The European Journal of Communication Research, 45(1), 5–27. https://doi.org/10.1515/commun-2018-2018

- *Appel, M., Slater, M. D., & Oliver, M. B. (2019). Repelled by virtue? The dark triad and eudaimonic narratives. Media Psychology, 22(5), 769–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2018.1523014

- Aristotle. (1931). Nicomachean ethics (W. D. Ross, Trans.). Oxford University Press.

- *Bailey, E., & Wojdynski, B. W. (2015). Effects of “meaningful” entertainment on altruistic behavior: Investigating potential mediators. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 59(4), 603–619. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2015.1093484

- *Bailey, E. J., & Ivory, J. D. (2018). The moods meaningful media create: Effects of hedonic and eudaimonic television clips on viewers’ affective states and subsequent program selection. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 7(2), 130–145. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000122

- *Barriga, C. (2011). Thoughtfulness and enjoyment as responses to moral ambiguity in fictional characters [Doctoral dissertation]. Cornell University. https://ecommons.cornell.edu/handle/1813/29125

- *Bartsch, A. (2012a). Emotional gratification in entertainment experience. Why viewers of movies and television series find it rewarding to experience emotions. Media Psychology, 15(3), 267–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2012.693811

- *Bartsch, A. (2012b). As time goes by: What changes and what remains the same in entertainment experience over the life span? Journal of Communication, 62(4), 588–608. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01657.x

- *Bartsch, A., & Hartmann, T. (2017). The role of cognitive and affective challenge in entertainment experience. Communication Research, 44(1), 29–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650214565921

- *Bartsch, A., Kalch, A., & Oliver, M. B. (2014). Moved to think: The role of emotional media experiences in stimulating reflective thoughts. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications, 26(3), 125–140. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000118

- *Bartsch, A., & Mares, M. L. (2014). Making sense of violence: Perceived meaningfulness as a predictor of audience interest in violent media content. Journal of Communication, 64(5), 956–976. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12112

- *Bartsch, A., Mares, M. L., Scherr, S., Kloß, A., Keppeler, J., & Posthumus, L. (2016). More than shoot-em-up and torture porn: Reflective appropriation and meaning-making of violent media content. Journal of Communication, 66(5), 741–765. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12248

- Bartsch, A., & Oliver, M. B. (2016). Appreciation of meaningful entertainment experiences and eudaimonic well-being. In L. Reinecke & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of media use and well-being: International perspectives on theory and research on positive media effects (pp. 80–92). Routledge.

- *Bartsch, A., Oliver, M. B., Nitsch, C., & Scherr, S. (2018). Inspired by the Paralympics: Effects of empathy on audience interest in para-sports and on the destigmatization of persons with disabilities. Communication Research, 45(4), 525–553. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650215626984

- *Bartsch, A., Scherr, S., Mares, M.-L., & Oliver, M. B. (2020). Reflective thoughts about violent media content – Development of a bilingual self-report scale in English and German. Media Psychology, 23(6), 794–819. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2019.1647248

- *Bartsch, A., & Schneider, F. M. (2014). Entertainment and politics revisited: How non-escapist forms of entertainment can stimulate political interest and information seeking. Journal of Communication, 64(3), 369–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12095

- Bartsch, A., Vorderer, P., Mangold, R., & Viehoff, R. (2008). Appraisal of emotions in media use: Toward a process model of meta-emotion and emotion regulation. Media Psychology, 11(1), 7–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213260701813447

- *Bonus, J. A., Wulf, T., & Matthews, N. L. (2019). The cost of clairvoyance: Enjoyment and appreciation of a popular movie as a function of affective forecasting errors. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000268

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper (Ed.), The handbook of research methods in psychology (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association.

- *Clayton, R. B., Raney, A. A., Oliver, M. B., Neumann, D., Janicke-Bowles, S. H., & Dale, K. R. (2019). Feeling transcendent? Measuring psychophysiological responses to self-transcendent media content. Media Psychology, 24(3), 359–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2019.1700135

- *Cohen, E. L. (2016). Exploring subtext processing in narrative persuasion: The role of eudaimonic entertainment-use motivation and a supplemental conclusion scene. Communication Quarterly, 64(3), 273–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2015.1103287

- Cohen, J., Appel, M., & Slater, M. D. (2020). Media, identity, and the self. In M. B. Oliver, A. A. Raney, & J. Bryant (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (4th ed., pp. 179–194). Routledge.

- Coplan, A. (2004). Empathic engagement with narrative fictions. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 62(2), 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-594X.2004.00147.x

- *Dale, K. R., Raney, A. A., Janicke, S. H., Sanders, M. S., & Oliver, M. B. (2017). YouTube for good: A content analysis and examination of elicitors of self-transcendent media. Journal of Communication, 67(6), 897–919. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12333

- *Das, E., Nobbe, T., & Oliver, M. B. (2017). Moved to act: Examining the role of mixed affect and cognitive elaboration in “accidental” narrative persuasion. International Journal of Communication, 11, 4907–4923.

- *Delmar, J. L., Sánchez-Martín, M., & Velázquez, J. A. M. (2018). To be a fan is to be happier: Using the eudaimonic spectator questionnaire to measure eudaimonic motivations in Spanish fans. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(1), 257–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9819-9

- *Eden, A., Daalmans, S., & Johnson, B. K. (2017). Morality predicts enjoyment but not appreciation of morally ambiguous characters. Media Psychology, 20(3), 349–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2016.1182030

- *Ellithorpe, M. E., Ewoldsen, D. R., & Oliver, M. B. (2015). Elevation (sometimes) increases altruism: Choice and number of outcomes in elevating media effects. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 4(3), 236–250. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000023

- *Ellithorpe, M. E., Huang, Y., & Oliver, M. B. (2019). Reach across the aisle: Elevation from political messages predicts increased positivity toward politics, political participation, and the opposite political party. Journal of Communication, 69(3), 249–272. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqz011

- Gottschall, J. (2012). The storytelling animal: How stories make us human. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Haidt, J. (2003). The moral emotions. In R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer, & H. H. Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of affective sciences (pp. 852–870). Oxford University Press.

- *Hall, A., & Zwarun, L. (2012). Challenging entertainment: Enjoyment, transportation, and need for cognition in relation to fictional films viewed online. Mass Communication & Society, 15(3), 384–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2011.583544

- *Hall, A. E. (2015). Entertainment-oriented gratifications of sports media: Contributors to suspense, hedonic enjoyment, and appreciation. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 59(2), 259–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2015.1029124

- *Hofer, M. (2013). Appreciation and enjoyment of meaningful entertainment: The role of mortality salience and search for meaning in life. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications, 25(3), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000089

- *Hofer, M. (2016). Effects of light-hearted and serious entertainment on enjoyment of the first and third person. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications, 28(1), 42–48. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000150

- *Hofer, M., Allemand, M., & Martin, M. (2014). Age differences in nonhedonic entertainment experiences. Journal of Communication, 64(1), 61–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12074

- *Hofer, M., Burkhard, L., & Allemand, M. (2015). Age differences in emotion regulation during a distressing film scene. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications, 27(1), 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000134

- Hofer, M., & Rieger, D. (2019). On being happy while consuming entertainment: Hedonic and non-hedonic modes of entertainment experiences. In J. A. Muniz & C. Pulido (Eds.), Routledge handbook of positive communication (pp. 120–128). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315207759-13

- *Igartua, J.-J., & Barrios, I. (2013). Hedonic and eudaimonic motives for watching feature films. Validation of the Spanish version of Oliver – Raney’s scale. Communications: The European Journal of Communication Research, 38(4), 411–431. https://doi.org/10.1515/commun-2013-0024

- *Jang, W., Lee, J. S., Kwak, D. H., & Ko, Y. J. (2019). Meaningful vs. Hedonic consumption: The effects of elevation on online sharing and information searching behaviors. Telematics & Informatics, 45, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2019.101298

- *Janicke, S. H., & Oliver, M. B. (2017). The relationship between elevation, connectedness, and compassionate love in meaningful films. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 6(3), 274–289. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000105

- *Janicke, S. H., & Ramasubramanian, S. (2017). Spiritual media experiences, trait transcendence, and enjoyment of popular films. Journal of Media & Religion, 16(2), 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348423.2017.1311122

- *Janicke, S. H., Rieger, D., Reinecke, L., & Connor, W. (2018). Watching online videos at work: The role of positive and meaningful affect for recovery experiences and well-being at the workplace. Mass Communication & Society, 21(3), 345–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2017.1381264

- Janicke-Bowles, S. H., Bartsch, A., Oliver, M. B., & Raney, A. (2021). Transcending eudaimonic entertainment: A review and expansion of meaningful entertainment. In P. Vorderer & C. Klimmt (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of entertainment theory (pp. 363–381). Oxford University Press.

- *Janicke-Bowles, S. H., Raney, A. A., Oliver, M. B., Dale, K. R., Jones, R. P., & Cox, D. (2019). Exploring the spirit in US audiences: The role of the virtue of transcendence in inspiring media consumption. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 98(2), 428–450. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699019894927

- *Khoo, G. S. (2016). Contemplating tragedy raises gratifications and fosters self-acceptance. Human Communication Research, 42(2), 269–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/hcre.12074

- *Khoo, G. S. (2018). From terror to transcendence: Death reflection promotes preferences for human drama. Media Psychology, 21(4), 719–749. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2017.1338965

- *Khoo, G. S., & Oliver, M. B. (2013). The therapeutic effects of narrative cinema through clarification: Reexamining catharsis. Scientific Study of Literature, 3(2), 266–293. https://doi.org/10.1075/ssol.3.2.06kho

- *Kim, J., Seo, M., Yu, H., & Neuendorf, K. (2014). Cultural differences in preference for entertainment messages that induce mixed responses of joy and sorrow. Human Communication Research, 40(4), 530–552. https://doi.org/10.1111/hcre.12037

- Klimmt, C., & Rieger, D. (2021). Biographic resonance theory of eudaimonic media entertainment. In P. Vorderer & C. Klimmt (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of entertainment theory (pp. 384–402). Oxford University Press.

- *Knobloch-Westerwick, S., Gong, Y., Hagner, H., & Kerbeykian, L. (2013). Tragedy viewers count their blessings. Feeling low on fiction leads to feeling high on life. Communication Research, 40(6), 747–766. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650212437758

- Krakowiak, K. M., & Oliver, M. B. (2012). When good characters do bad things: Examining the effect of moral ambiguity on enjoyment. Journal of Communication, 62(1), 117–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01618.x

- *Krämer, N., Eimler, S. C., Neubaum, G., Winter, S., Rösner, L., & Oliver, M. B. (2017). Broadcasting one world: How watching online videos can elicit elevation and reduce stereotypes. New Media & Society, 19(9), 1349–1368. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816639963

- *Krämer, N. C., Neubaum, G., Winter, S., Schaewitz, L., Eimler, S., & Oliver, M. B. (2019). I feel what they say: The effect of social media comments on viewers’ affective reactions toward elevating online videos. Media Psychology, 24(3), 332–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2019.1692669

- *Lewis, R. J., Grizzard, M. N., Choi, J. A., & Wang, P. L. (2019). Are enjoyment and appreciation both yardsticks of popularity? Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications, 31(2), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000219

- *Mares, M.-L., Bartsch, A., & Bonus, J. A. (2016). When meaning matters more: Media preferences across the adult life span. Psychology and Aging, 31(5), 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000098

- *Mares, M. L., Oliver, M. B., & Cantor, J. (2008). Age differences in adults’ emotional motivations for exposure to films. Media Psychology, 11(4), 488–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213260802492026

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

- Maslow, A. H. (1968). Toward a psychology of being (2nd ed.). Van Nostrand.

- *Meier, Y., & Neubaum, G. (2019). Gratifying ambiguity: Psychological processes leading to enjoyment and appreciation of TV series with morally ambiguous characters. Mass Communication and Society, 22(5), 631–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2019.1614195

- *Möller, A. M., & Kühne, R. (2019). The effects of user comments on hedonic and eudaimonic entertainment experiences when watching online videos. Communications, 44(4), 427–446. https://doi.org/10.1515/commun-2018-2015

- *Myrick, J. G., & Oliver, M. B. (2015). Laughing and crying: Mixed emotions, compassion, and the effectiveness of a YouTube PSA about skin cancer. Health Communication, 30(8), 820–829. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2013.845729

- *Neubaum, G., Krämer, N. C., & Alt, K. (2020). Psychological effects of repeated exposure to elevating entertainment: An experiment over the period of 6 weeks. Psychology of Popular Media, 9(2), 194–207. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000235

- *Odağ, Ö., Hofer, M., Schneider, F. M., & Knop, K. (2016). Testing measurement equivalence of eudaimonic and hedonic entertainment motivations in a cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 45(2), 108–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/17475759.2015.1108216

- *Odağ, Ö., Uluğ, Ö. M., Arslan, H., & Schiefer, D. (2018). Culture and media entertainment: A cross-cultural exploration of hedonic and eudaimonic entertainment motivations. International Communication Gazette, 80(7), 637–657. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048518802215

- *Oliver, M. B. (2008). Tender affective states as predictors of entertainment preference. Journal of Communication, 58(1), 40–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00373.x

- *Oliver, M. B., Ash, E., Woolley, J. K., Shade, D. D., & Kim, K. (2014). Entertainment we watch and entertainment we appreciate: Patterns of motion picture consumption and acclaim over three decades. Mass Communication and Society, 17(6), 853–873. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2013.872277

- Oliver, M. B., Bailey, E., Ferchaud, A., & Yang, C. (2017). Entertainment effects: Media appreciation. In P. Rössler (Ed.), The international encyclopedia of media effects. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118783764.wbieme0164

- *Oliver, M. B., & Bartsch, A. (2010). Appreciation as audience response: Exploring entertainment gratifications beyond hedonism. Human Communication Research, 36(1), 53–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2009.01368.x

- Oliver, M. B., & Bartsch, A. (2011). Appreciation of entertainment: The importance of meaningfulness via virtue and wisdom. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications, 23(1), 29–33. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000029

- *Oliver, M. B., & Hartmann, T. (2010). Exploring the role of meaningful experiences in users’ appreciation of “good movies”. Projections: The Journal for Movies and Mind, 4(2), 128–150. https://doi.org/10.3167/proj.2010.040208

- *Oliver, M. B., Hartmann, T., & Woolley, J. K. (2012). Elevation in response to entertainment portrayals of moral virtue. Human Communication Research, 38(3), 360–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2012.01427.x

- Oliver, M. B., Kim, K., Hoewe, J., Chung, M. Y., Ash, E., Woolley, J. K., & Shade, D. D. (2015). Media-induced elevation as a means of enhancing feelings of intergroup connectedness. Journal of Social Issues, 71(1), 106–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12099

- *Oliver, M. B., & Raney, A. A. (2011). Entertainment as pleasurable and meaningful: Identifying hedonic and eudaimonic motivations for entertainment consumption. Journal of Communication, 61(5), 984–1004. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01585.x

- Oliver, M. B., Raney, A. A., Slater, M., Appel, M., Hartmann, T., Bartsch, A., Schneider, F. M., Janicke-Bowles, S. H., Krämer, N., Mares, M.-L., Vorderer, P., Rieger, D., Dale, K. R., & Das, H. H. J. (2018). Self-transcendent media experiences: Taking meaningful media to a higher level. Journal of Communication, 68(2), 380–389. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqx020

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. American Psychological Association.

- *Prestin, A., & Nabi, R. (2020). Media prescriptions: Exploring the therapeutic effects of entertainment media on stress relief, illness symptoms, and goal attainment. Journal of Communication, 70(2), 145–170. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqaa001

- *Raney, A. A., Janicke, S. H., Oliver, M. B., Dale, K. R., Jones, R. P., & Cox, D. (2018). Profiling the audience for self-transcendent media: A national survey. Mass Communication and Society, 21(3), 296–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2017.1413195

- Raney, A. A., Oliver, M. B., & Bartsch, A. (2020). Eudaimonia as media effect. In M. B. Oliver, A. A. Raney, & J. Bryant (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (4th ed., pp. 258–274). Routledge.

- *Rieger, D., & Bente, G. (2018). Watching down cortisol levels? Effects of movie entertainment on psychophysiological recovery. SCM Studies in Communication and Media, 7(2), 231–255. https://doi.org/10.5771/2192-4007-2018-2-103

- *Rieger, D., Frischlich, L., Högden, F., Kauf, R., Schramm, K., & Tappe, E. (2015). Appreciation in the face of death: Meaningful films buffer against death-related anxiety. Journal of Communication, 65(2), 351–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12152

- *Rieger, D., Frischlich, L., & Oliver, M. B. (2018). Meaningful entertainment experiences and self-transcendence: Cultural variations shape elevation, values, and moral intentions. International Communication Gazette, 80(7), 658–676. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048518802218

- *Rieger, D., & Hofer, M. (2017). How movies can ease the fear of death: The survival or death of the protagonists in meaningful movies. Mass Communication & Society, 20(5), 710–733. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2017.1300666

- Rieger, D., & Klimmt, C. (2019). The daily dose of digital inspiration: A multi-method exploration of meaningful communication in social media. New Media & Society, 21(1), 97–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818788323

- *Rieger, D., Reinecke, L., & Bente, G. (2017). Media-induced recovery: The effects of positive versus negative media stimuli on recovery experience, cognitive performance, and energetic arousal. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 6(2), 174–191. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000075

- *Rieger, D., Reinecke, L., Frischlich, L., & Bente, G. (2014). Media entertainment and well-being-linking hedonic and eudaimonic entertainment experience to media-induced recovery and vitality. Journal of Communication, 64(3), 456–478. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12097

- Rigby, C. S., & Ryan, R. M. (2016). Time well-spent? Motivation for entertainment media and its eudaimonic aspect through the lens of self-determination theory. In L. Reinecke & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of media use and well-being international perspectives on theory and research on positive media effects (pp. 34–48). Routledge.

- *Roth, F., Weinmann, C., Schneider, F., Hopp, F., & Vorderer, P. (2014). Seriously entertained: Antecedents and consequences of hedonic and eudaimonic entertainment experiences with political talk shows on TV. Mass Communication & Society, 17(3), 379–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2014.891135

- *Roth, F. S., Weinmann, C., Schneider, F. M., Hopp, F. R., Bindl, M. J., & Vorderer, P. (2018). Curving entertainment: The curvilinear relationship between hedonic and eudaimonic entertainment experiences while watching a political talk show and its implications for information processing. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 7(4), 499–517. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000147

- Ryan, R. M., Huta, V., & Deci, E. L. (2008). Living well: A self-determination theory perspective on eudaimonia. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 139–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9023-4

- Ryff, C., & Singer, B. (2008). Know thyself and become what you are: An eudiamonic approach to psychological wellbeing. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 13–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9019-0

- *Schneider, F. M., Bartsch, A., & Oliver, M. B. (2019). Factorial validity and measurement invariance of the appreciation, fun, and suspense scales across US-American and German samples. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications, 31(3), 149–156. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000236

- *Schneider, F. M., Weinmann, C., Roth, F. S., Knop, K., & Vorderer, P. (2016). Learning from entertaining online video clips? Enjoyment and appreciation and their differential relationships with knowledge and behavioral intentions. Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 475–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.08.028

- Schramm, H., & Wirth, W. (2008). A case for an integrative view on affect regulation through media usage. Communications: The European Journal of Communication Research, 33(1), 27–46. https://doi.org/10.1515/COMMUN.2008.002

- *Schramm, H., & Wirth, W. (2010). Exploring the paradox of sad-film enjoyment: The role of multiple appraisals and meta-appraisals. Poetics, 38(3), 319–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2010.03.002

- *Shafer, D. M., Janicke, S. H., & Seibert, J. (2016). Judgment and choice: Moral complexity, enjoyment and meaningfulness in interactive and non-interactive narratives. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 21(8), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-2106010106

- Slater, M. D., Johnson, B. K., Cohen, J., Comello, M. L. G., & Ewoldsen, D. R. (2014). Temporarily expanding the boundaries of the self: Motivations for entering the story world and implications for narrative effects. Journal of Communication, 64(3), 439–455. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12100

- *Slater, M. D., Oliver, M. B., & Appel, M. (2019). Poignancy and mediated wisdom of experience: Narrative impacts on willingness to accept delayed rewards. Communication Research, 46(3), 333–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650215623838

- *Slater, M. D., Oliver, M. B., Appel, M., Tchernev, J. M., & Silver, N. A. (2018). Mediated wisdom of experience revisited: Delay discounting, acceptance of death, and closeness to future self. Human Communication Research, 44(1), 80–101. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqx004

- Tal-Or, N., & Cohen, J. (2015). Unpacking engagement: Convergence and divergence in transportation and identification. Annals of the International Communication Association, 40(1), 33–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2015.11735255

- Tamborini, R. (2011). Moral intuition and media entertainment. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications, 23(1), 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000031

- Taormina, R. J., & Gao, J. H. (2013). Maslow and the motivation hierarchy: Measuring satisfaction of the needs. The American Journal of Psychology, 126(2), 155–177. https://doi.org/10.5406/amerjpsyc.126.2.0155

- *Tsay-Vogel, M., & Krakowiak, K. M. (2016). Inspirational reality TV: The prosocial effects of lifestyle transforming reality programs on elevation and altruism. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 60(4), 567–586. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2016.1234474

- *Tsay-Vogel, M., & Sanders, M. S. (2017). Fandom and the search for meaning: Examining communal involvement with popular media beyond pleasure. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 6(1), 32–47. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000085

- *Waddell, T. F., Bailey, E., & Davis, S. E. (2019). Does elevation reduce viewers’ enjoyment of media violence? Testing the intervention potential of inspiring media. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications, 31(2), 103–109. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000214

- Waterman, A. S. (2008). Reconsidering happiness: A eudaimonist’s perspective. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(4), 234–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760802303002

- *Weinmann, C. (2017). Feeling political interest while being entertained? Explaining the emotional experience of interest in politics in the context of political entertainment programs. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 6(2), 123–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000091

- *Weinmann, C., Schneider, F. M., Roth, F. S., Bindl, M. J., & Vorderer, P. (2016). Testing measurement invariance of hedonic and eudaimonic entertainment experiences across media formats. Communication Methods and Measures, 10(4), 248–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2016.1227773

- *Wirth, W., Hofer, M., & Schramm, H. (2012). Beyond pleasure: Exploring the eudaimonic entertainment experience. Human Communication Research, 38(4), 406–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2012.01434.x

- *Wulf, T., Bonus, J. A., & Rieger, D. (2019). The inspired time traveler: Examining the implications of nostalgic entertainment experiences for two-factor models of entertainment. Media Psychology, 22(5), 795–817. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2018.1532299

- *Zhao, D. (2018). Mood management, self-transcendence, and prosociality: Selective exposure to meaningful media entertainment and prosocial behavior [Dissertation]. Florida State University. https://diginole.lib.fsu.edu/islandora/object/fsu%3A647324

- Zickfeld, J. H., Schubert, T. W., Seibt, B., Blomster, J. K., Arriaga, P., Basabe, N., Blaut, A., Caballero, A., Carrera, P., Dalgar, I., Ding, Y., Dumont, K., Gaulhofer, V., Gračanin, A., Gyenis, R., Hu, C.-P., Kardum, I., Lazarević, L. B., Mathew, L., … Fiske, A. P. (2019). Kama muta: Conceptualizing and measuring the experience often labelled being moved across 19 nations and 15 languages. Emotion, 19(3), 402–424. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000450