Abstract

How public policies change incrementally over time remains understudied. This paper contributes to the studies of incremental policy change by integrating the theories of policy layering and learning into a theoretical framework of experimental governance (EG). Using a mixed research method, we apply this framework to process-tracing the changing trajectory of China’s central government infrastructure public-private partnership (PPP) policies from 1988 to 2017 by looking at evolving policy goals, policy measures, and policy co-issuing networks. Results suggest that China’s central government infrastructure PPP policy change follows a refined EG approach in which policies change incrementally in a layering pattern, primarily driven by learning. Findings provide a new account of incremental policy change.

Introduction

Most policy changes are relatively incremental.Footnote1 However, two issues on how public policies change incrementally over time remain unaddressed. First, the question of which one—learning, competition, imitation, or conflict—is more likely to drive incremental policy change is underexplored.Footnote2 Second, extant studies on policy change primarily focus on evolving policy goals and measures.Footnote3 A policy goal refers to the end toward which a policy is directed and policy measures include techniques, means, or instruments to attain policy goals.Footnote4 In current complex societies, public policies often aim to address the ‘wicked’ multifaceted problems that require interagency coordination. Multiple agencies negotiate policy goals and measures and then jointly issue multiple policies toward collective objectives, thus forming a policy co-issuing network because policy issues often extend beyond departmental boundaries and multi-departmental collaboration is necessary to tackle their common problems.Footnote5 Yet, how policy co-issuing networks change has not been fully studied.

An experimentalist governance (EG) frameworkFootnote6 has the potential to address these issues. As an analytical framework, researchers have used EG to study how policy actors make, implement, and adjust public policies.Footnote7 EG not only treats the policy process as a recursive one of provisional goals, measuring settings, and revision based on learning by comparing alternatives under different local contexts, but also adopts a horizontal structure of learning.Footnote8 Researchers have applied EG to studying the European Union’s (EU) public policy problem solving in areas ranging from energy, telecommunications, financial services, food and drug safety, and environmental protection, to criminal justice, home affairs, and anti-discrimination. Multilevel participants (EU, national, and local) consistently reflect on policy solutions in a process of collective learning based on the variations of local practice.Footnote9 Researchers have also used EG to study policymaking in other countries—the United States, Australia, and China—to promote economic growth, deliver public services, and protect the environment.Footnote10 While EG has focused on studying policy implementation, it has not yet been applied to examining policy change. We propose that the EG framework can be refined to integrate with existing policy change theories on layering and learning to serve as a useful lens to better understand incremental policy change that also involves a process of policy experimentation in which multilevel participants learn lessons from previous policies and revise current policies.

The empirical case of incremental policy change we examine draws from a very specific setting: that of China’s central government infrastructure PPP policy development between 1988 and 2017. PPPs are defined as cooperation between public and private sectors with a durable character in which risk, costs, and benefits are shared to supply infrastructure.Footnote11

Three reasons make the setting of China’s PPP policy development on infrastructure an ideal one to explore how the refined EG framework helps unpack the process of incremental policy change. First, many countries have designed policies to support PPP development over the past 3 decades.Footnote12 Since the initiation of reform and the opening-up policy in the 1980s, China has issued a series of policies to develop infrastructure PPP projects.Footnote13 The rapid development of PPPs in China faced many challenges, such as failures in attracting private investments and the lack of standards and consistency in PPP regulation.Footnote14 In response to these challenges, over a long period of 30 years, the Chinese central government has continually adjusted its PPP policies without radically altering the core objective of attracting investment to develop infrastructure, thus epitomizing a process of incremental policy change. Second, infrastructure PPP policy development, as one type of economic policymaking, is a knowledge-intensive process clearly associated with the concept of policy learning.Footnote15 Thus, China’s infrastructure PPP policy change is appropriate for researchers to apply the concept of learning embedded in EG. China’s PPP policy change follows a top-down fashion, and thus state-centered theories such as developmentalism are also relevant. However, the theory of developmentalism as a macro theory focuses on the state’s involvement in the mobilization and allocation of resources.Footnote16 The theory does not fully explain meso-level policy change. Third, this case also provides opportunities against which to study the policy-learning process dominated by officials and technical experts because the power of officials and experts to make policy changes should be at its maximum in highly technical fields like PPP policy development and in nations like China that have highly hierarchical and closed bureaucracies. Bureaucrats and experts are key agents who push forward the policy-learning process.Footnote17

This paper treats China’s central government infrastructure PPP policy change as the unit of analysis, including policy goals, policy measurements, and co-issuing networks between 1988 and 2017. We advance scholarly research on policy change by applying a refined EG to tracing the process of China’s infrastructure PPP policy change with the following research questions: Did policies change incrementally? If so, how?

In the next section, we integrate policy layering and learning into the EG framework to better understand incremental policy change. The EG framework refined herein provides a more holistic picture of how China’s infrastructure PPP policies have evolved over time. The following sections describe the data collection of China’s central government infrastructure PPP policy change and mixed methods of process-tracing (PT), bibliometric network analysis, and interviews. The empirical results follow. The final section concludes the paper with theoretical and practical implications and avenues for future research.

Theoretical framework of incremental policy change: refining EG with layering and learning

Three features highlighted in the original EG framework are relevant to incremental policy change.Footnote18 The first feature is regularly reporting on performance and periodically revising policies; second, policies are periodically revised by multiple actors, mostly central and local units,Footnote19 and no single actor has the ability to impose policy goals or measures without incorporating the views of others.Footnote20 Third, a comparison of implementing experiences from different units in decision-making is crucial to EG.Footnote21

The EG approach to incremental policy change can be re-conceptualized as a process of layering. As a relatively new theoretical approach, policy layering focuses on continuity of policy results in a non-radical change process. Policy layering refers to amendments, additions, or revisions to existing institutions and introduces new elements to supplant or crowd-out the old system, thereby altering the rules of the original work.Footnote22 Policy layering is also different from policy conversion. The former preserves many core existing policies. For example, South Korea’s ‘old’ social policies were fairly stable, whereas their ‘new’ policies have grown, following a path of layering.Footnote23 The latter substitutes ‘old’ policy objectives and goals with new goals and actors.Footnote24

The theory of policy layering provides an alternative path without a confrontation with those groups that benefited from and supported the old policies.Footnote25 The policy status and structure involve a gradual changing process by attaching new elements into existing policies over time. Every new element may be a tiny change, but those changes may accumulate and lead to great changes over a long time period.Footnote26 Layering is the product of policy interaction and results in specific social, economic, or political adjustments that correspond with new policies that adjust later.Footnote27 By adding new policy measures to redesign existing ones, policy actors involved in layering create sustainability while still pursuing the original goals.Footnote28 Such a gradual policy change process is similar to Hall’sFootnote29 second-order change where policy goals remain largely the same but the means used to attain them are altered. In a similar vein, EG refers to recursive decision making with a provisional policy setting and revision. In a recursive process, one’s procedural output becomes the input for the next, so that iteration of the same process produces changing results.Footnote30 In line with policy layering, previous policy measures would be renewed. Often, the choice of slow incremental change with a gradual revision-process ‘tango’ that moves several steps forward and then a step or two backward is the best strategy to achieve any change.Footnote31 Therefore, policy layering can be understood as one of EG’s external manifestations of policy change.

Policy learning can foster the EG approach to incremental policy change. Policy learning is defined as a deliberate attempt to renew policies in response to past experience and the availability of new information.Footnote32 Policy learning from previous experiences is a key factor in policy experimentation because learning can change attitudes and norms, thereby fostering changes in practice.Footnote33 New information provides policy windows of opportunities for change. EG focuses on learning from a comparison of experiencesFootnote34 and the periodic review of comparative processes will promote learning beyond experimentalist policymaking.Footnote35 In this sense, learning is EG’s internal driver of policy change. For policy learning as a feedback process to occur, it must meet three conditions: detection of problems from past experiences (e.g. contexts, triggers, hindrances, and pathologies),Footnote36 obtaining new information, and modifying current policy measurements and co-issuing networks in response to problems. Identifying problems from past experiences motivates and justifies a policy change. Availability of new information or some unexpected exogenous events trigger policy change.Footnote37 Therefore, policy learning can be an important trigger of incremental policy change.

Data and mixed research method

Process-tracing

This study followed a qualitative research tradition of PT, involving the in-depth study of causal mechanisms in a single caseFootnote38 for three reasons. First, PT is a research method for tracing causal mechanisms using detailed, within-case empirical analysis of how a causal process plays out in an actual case. Second, it is an analytical tool of systematically examining case evidence selected and analyzed in light of research questions for drawing descriptive and causal inferences. Third, PT is often understood as part of a temporal sequence of events or phenomena.

Data collection

The data collection process primarily involved policy document analysis. We extracted data on China’s central government infrastructure PPP policies from the PKULaw databaseFootnote39 and the China PPP Center’s website affiliated with the State Development and Reform CommissionFootnote40 where we identified 129 infrastructure PPP policy documents from 1988 to 2017. We used the following key words to conduct the search: ‘PPP’, ‘BOT’, ‘政府与社会资本合作’ (PPPs, Zheng fu Yu She Hui Zi Ben He Zuo), ‘公私合作伙伴关系’ (PPPs, Gong Si He Zuo Huo Ban Guan Xi), ‘社会投资’ (Nongovernmental investment, She Hui Tou Zi), ‘私人投资’ (Private investment, Si ren Tou Zi), and ‘融资’ (Financing, Rong Zi). Two researchers first coded the material independently by identifying policy goals and measures. Inter-coding reliability for policy goals and measures ranged from 80% to 85%. Then, the researchers discussed resolving the differences.

To gain a deep understanding of the importance of infrastructure PPP policies on developing PPP projects, we collected a number of China’s infrastructure PPP projects from the Private Participation in Infrastructure (PPI) project database and China’s PPP central project database. The former was built by the World Bank and the latter by China’s Ministry of Finance. Researchers widely use the two databases to study China’s infrastructure PPP projects.Footnote41 We triangulated these two datasets and identified 4,077 PPP projects from 1988 to 2017.

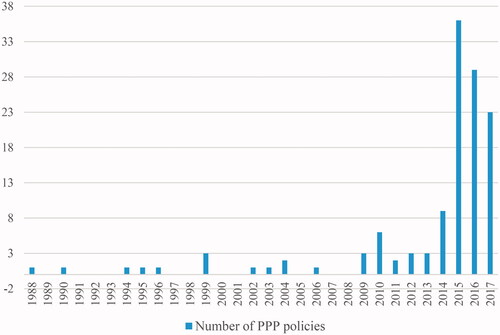

Figure illustrates the annual number of infrastructure PPP polices issued by China’s central government in the past 3 decades (1988–2017), representing different PPP development statuses across different phases. From 1988 to 2008 the number of PPP policies were distributed sporadically. From 2009 to 2013, PPP policies increased gradually and steadily. Policies were issued more intensively than before. From 2014 to 2017, PPP policies experienced an explosive and significant growth.

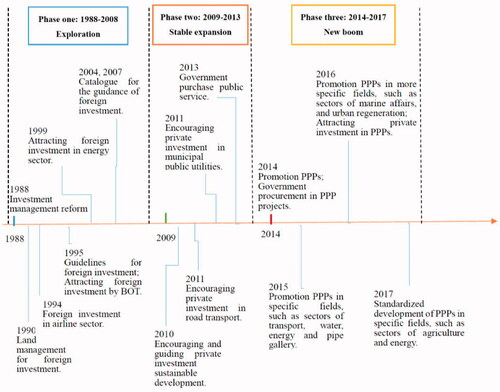

Existing studies have divided China’s infrastructure PPP development into several phases according to the changing number of PPP projects. Some used the year 2009 as a key demarcation of China’s central PPP policies’ developmentFootnote42 whereas others took the years 2009 and 2014 as two watersheds.Footnote43 Drawing on the extant studies and witnessing significant differences in the number of infrastructure PPP projects and PPP policies issued shown in Figure , we used the years 2009 and 2014 to classify China’s central government infrastructure PPP policies’ development into three distinctive stages as follows: Phase I of exploration started from 1988 and ended with the world financial crisis of 2008. The PPP policy development focused on traditional infrastructures such as transport, water, energy, and municipal facilities. Phase II of stable expansion stretched from 2009 to 2013. The area extended to infrastructures in public services such as schools and hospitals. Phase III of a new boom lasted from 2014 to 2017 by adding new infrastructures in high technology, such as smart-cities building.

Phase III has seen a rapid growth of PPP policies, which appear to follow a punctuated equilibrium (PE). As a disjoint and abrupt process of policy change, PE often leads to a policy paradigm shift.Footnote44 However, since 2013, core tenets of China’s PPP policies have not changed. Like those in Phase I and II, PPPs in Phase III were still treated as financial tools rather than a radical governance paradigm shift.Footnote45 Thus, we propose the PPP policy change as an incremental process.

Social network analysis

The fine-grained description of PT sometimes relies on quantitative data. This study used a bibliometric tool—social network analysis (SNA)—to analyze data. With the SNA, we can map out the network structure through a co-word network analysis. The co-word analysis assumes that words can be captured when the words co-occur frequently in the policy document.Footnote46 A co-word network consists of nodes and ties. In this study, we coded policy goals, policy measures, and policy issuers as nodes. Ties between policy goals and measures indicated what measures were used to achieve what goals. The ties between policy issuers indicate the number of policies jointly issued by any two central-government agencies.

Specifically, our analyses included 2-mode networks to delineate policy-measure changes, and a one-mode network to describe policy co-issuing network changes. The 2-mode network means the analysis involves two sets of nodes or a set of nodes and a set of events; the one-mode networks involve only a single set of nodes.Footnote47 In this paper, the 2-mode network depicted relationships between policy goals and measures and the one-mode network illustrated relationships between policy co-issuers. Further, we computed network density, network centralization, and degree centrality to compare changes to policy co-issuing networks. Network density is usually defined as the average strength of ties across all possible ties. Network centralization refers to the extent to which networking relationships concentrate in a few nodes. Degree centrality is one node’s co-appearance with others.

Supplementary interviews and document reviews

We applied two additional approaches to triangulating and interpreting quantitative results. First, we conducted semi-structured interviews in 2019 with 15 academic researchers, government officials, and practitioners who studied and were involved in China’s central government infrastructure PPP policy development. Government officials and experts play the most central role in each instance of learning that leads to incremental policy change in highly technical policy domains. Those groups control the advice going to policymakers and the forecasts on which that advice is based.Footnote48 Epistemic communities and policy entrepreneurs can play important roles in incremental policy change, even in a fragmented bureaucracy and an authoritarian regime like China.Footnote49 Second, we further reviewed additional official reports, policy documents, media news, and academic studies. These interviews and document reviews helped us reveal the role of policy learning in China’s infrastructure PPP policy change from the EG perspective.

Main findings

In this section, we first present the results of data analysis and then discuss whether China’s central government infrastructure PPP policy change follows a refined EG approach with policy layering and learning.

Policy goals’, measures’, and co-issuing networks’ change in different phases

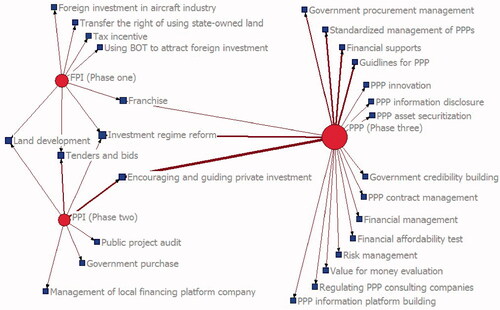

As shown in Figure , core infrastructure PPP policy goals remained unchanged across three phases over the past 3 decades. The core policy goals were to attract enterprises to participate in infrastructure development and to improve the cooperation between governments and enterprises. Policy goals in different phases adapt some minor adjustments and amendments to different environments. Thus, PPP policy change is a layering, rather than a conversion, process.

In Phase I (1988–2008), the infrastructure PPP policy’s goal was to attract and manage foreign capital. China began to enter a period of reform and opening up. China’s government was changing from a planned economy to a market economy. The domestic private capital market was small and weak, especially in the 1990s. Therefore, China urgently needed to attract foreign capital to develop the economy, including infrastructure investments.Footnote50 For example, the central government initiated five build-operate-transfer (BOT) projects, including the Laibin B Power Plant and the Chengdu No. 6 Water Plan.Footnote51 All these BOT projects were partnerships between local governments and foreign investors. After 2000, China’s government issued many laws to regulate foreign investment, such as laws of tenders and bids, government procurements, and franchises.

In Phase II (2009–2013), the core infrastructure PPP policy’s goal was to attract both foreign and domestic private infrastructure investments to stimulate economic growth following the economic crisis. Many researchers showed that investments in infrastructure sectors stimulate economic growth.Footnote52 For example, from 2009 to 2010, China invested four trillion RMB to stimulate the economy. Most projects targeted infrastructure, including low-income housing, rural infrastructure, railways, roads, airports, and environmental improvement.

In Phase III (2014–2017), the infrastructure PPP policy’s goals were to attract enterprise investments in infrastructure and to manage public-private cooperation. Since 2014, China’s government has promoted PPPs in a top-down fashion. The central government’s core policy goal was to still attract enterprise investments in PPP infrastructure projects. To standardize PPP procurement and operation, the central government issued a large number of PPP policies in many sectors, such as municipal utilities, water, agriculture, culture, railway, energy, and transport to provide PPP knowledge for local governments and promote sustainable PPP projects.

Policy measures for achieving policy goals in three phases

To fulfill policy goals, multiple policy measures are often necessary to modify or alter the policy design, processes, and outcomes.Footnote53 The goal of combining individual policy measures, defined as a policy package, helps achieve one or more policy goals.Footnote54 The policy package does not occur in a socio-cultural vacuum; rather, it is created on the basis of special local and historical procedures and environments. The policy package includes primary and additional measures. The former provides a direct manner to achieve policy objectives and the latter provides additional measures to enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of policy intervention.Footnote55 Some primary measures may remain unchanged during the process of policy layering because they can still help achieve new policy goals in different periods. However, new measures would improve or adjust some other primary measures to further address adjusted policy goals.

PPP policy measures change across three phases

Figure shows the evolving policy measures to achieve adjusted policy goals in the past three phases in China. This is a 2-mode network between policy goals and measures. In Phase I, the central government issued many policy measures to stimulate foreign direct investment to achieve the main goal of attracting more foreign capital participation in infrastructure. For instance, governments reformed their investment-management regimes, including further streamlining administration and delegating more power to lower levels, giving enterprises discretionary powers for decision-making, and using tender and bid methods to select investors. Governments also used tax incentives and land development to attract foreign investment in infrastructure. Also, the central government encouraged foreign investors to adopt the BOT and franchises to participate in infrastructure development. These policy measures worked in combination to attract foreign investment. However, some barriers prevented PPPs from being adopted on a large scale; for example, risks were not equitably allocated.Footnote56

Figure 3. Policy measures of 2-mode network. Note. FPI: Foreign participation in infrastructure; PPI: Private participation in infrastructure. The 2-mode data is a rectangular data matrix of policy measures (rows) by phases (columns).

In Phase II, the central government further reformed its investment-management regime to better manage foreign and domestic private investment. For example, the central government reduced investors’ capital requirements in the infrastructure field and issued guidelines for project finance to reduce the risk of financial institutions. Also, the central government encouraged local governments to purchase public services from the market, thereby encouraging governments to become smart buyers and smart managers of contracted service provision.Footnote57 However, in response to the global financial crisis of 2008, the Chinese government invested four trillion RMB to stimulate infrastructure development. Local governments then switched back to traditional procurement methods and crowded-out private investments. Large-scale direct investments again imposed huge financial burdens on central and local governments.

In Phase III, the central governments, especially the State Council, the Ministry of Finance, and the State Development and Reform Commission released many policies to promote infrastructure PPP development from 2014 to 2017 to attract and manage domestic private and foreign investors to the PPP market to relieve financial burdens. These policy measures included the value for money evaluation, financial affordability tests, guidelines for PPPs, PPP contract management, PPP information disclosures, and so on. As in the former two phases of policy measures, Phase III continued to focus on reforming the investment-management regime. In this round of reform, PPPs were seen as an effective way to deliver public services through cooperation among governments and enterprises.

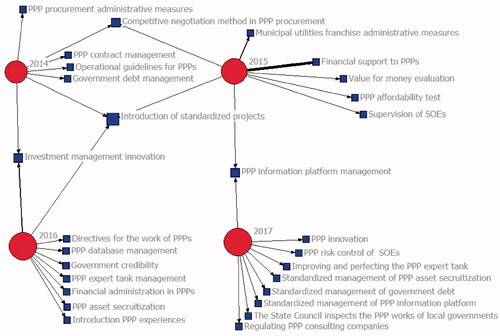

PPP policy measures change from 2014 to 2017

Focusing on infrastructure PPP policies from 2014 to 2017, Figure shows the gradual change process of policy measures in a short time, with 2014 and 2015 as the years in which China started to promote local infrastructure PPPs. Many local government officials did not know what a PPP was and how to use it. Therefore, policy measures in the first 2 years focused on how to operationalize PPPs to guide local governments, such as the PPP operational guidelines, contract management, value for money evaluations, and PPP affordability tests. Central-government agencies (e.g. the Ministry of Finance and the People’s Bank of China) provided direct (e.g. capital subsidies, revenue subsidies, and in-kind) and indirect financial (e.g. government guarantees, and tax deductions) supports to PPP projects.

Figure 4. Policy measures of 2-mode network from 2014 to 2017. Note. The 2-mode data is a rectangular data matrix of policy measures (rows) by years (columns).

PPP policy measures changed from PPP operational procedures to build an institutional environment in 2016. Efforts in institution building included building government credibility, creating a PPP database, disclosing information, and supporting a PPP think-tank. These institution-building measures were useful in contributing to the successful implementation of PPP operational procedures. However, it took a long time to build the institutional system.

Because of poor government-contract-management capacity, immature markets, and a poor institutional environment, infrastructure PPP development in developing countries (e.g. China) faces greater challenges than in developed countries.Footnote58 As a result, the central government issued some policy measures to standardize PPP management in 2017. The key word of policy measures is ‘standardization’, meaning the central government would expend greater efforts to regulate PPP terms and practices, such as agreements, bidding documents, and guidance manuals to achieve substantial risk transfer, value for money, and financial affordability. Standardization was seen as a process change or re-innovation.Footnote59 The main policy measures from 2014 to 2016 focused on how to develop PPPs in China, but in 2017 the focus shifted to how to better manage PPPs.

Changing policy co-issuing networks across three phases

Multiple central-government agencies that issued different infrastructure PPP policies also caused conflict and fragmentation. For example, in 2016, the Ministry of Finance and the State Development and Reform Commission issued separate policies on managing PPP projects in transportation, energy, municipal utilities, and environmental protection. Local governments did not know which policy measures they should follow. The central government was aware of this problem and subsequently coordinated central-government agencies to jointly release policies.

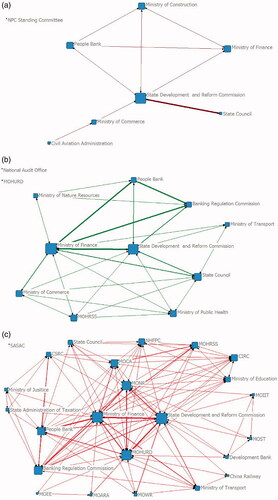

As indicated in Figure , central departments that co-released PPP-related policies from 1988 to 2017 showed a dynamic trajectory of network development. In the network, the node was individual central-government agencies issuing PPP policies. Ties between two nodes are the frequencies of co-releasing PPP policies. The bigger node means the agencies co-released policies more frequently. The wider ties indicate the two agencies co-released a greater number of polices. In addition, we computed the number of actors and ties, network density, network centralization, and normalized degree centrality of the three networks (Figure )) in Table . Network density and network centralization are commonly applied to measuring cohesion or integration of whole networks, and normalized degree centrality is a node-level measure to analyze the position or power of individual nodes in a network.Footnote60 Higher density means nodes in the network have more connections. A decentralized network means the network distributes control to many nodes. The degree centrality measures the node’s importance in the network. The changing scores of density, centralization, and degree centrality provide information on how co-issuing networks change over time.

Figure 5. (a) Co-issuing network in PhaseI. (b) Co-issuing network in PhaseII. (c) Co-issuing network in Phase III. Note. Figures present one-mode networks. The one-mode data is a symmetric data matrix of co-frequency of the departments. CIRC: China Insurance Regulatory Commission; CSRC: China Securities Regulatory Commission; MOARA: Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs; MOCA: Ministry of Civil Affairs; MOEE: Ministry of Ecology and Environment; MOHRSS: Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security; MOHURD: Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development; MOIIT: Ministry of Industry and Information Technology; MONR: Ministry of Natural Resources; MOST: Ministry of Science and Technology; MOWR: Ministry of Water Resources; NHFPC: National Health Commission; NPC Standing Committee: Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress; People Bank: The People’s Bank of China.

Table 1. Comparison of policy co-issuing networks in different phases.

First, the three co-issuing networks showed that increasing numbers of agencies participated in the networks. Issuing PPP policies in Phases I, II, and III in Figure , respectively, were 8, 12, and 24 central departments. The number of ties was 20, 80, and 408 in the three phases, respectively. The department with the highest administrative level was the State Council of the People’s Republic of China. In Figure , the network’s anchor-tenant, the primary or dominant actors in the network,Footnote61 was the State Development and Reform Commission. The anchor-tenant is the main co-issuer of PPP policies. Its normalized degree centrality is 42.857. In Figure , the anchor-tenants become the Ministry of Finance and the State Development and Reform Commission. Their normalized degree centrality scores are 40.909 and 31.818, respectively. In Figure , the main anchor-tenants are also the Ministry of Finance and the State Development and Reform Commission. Their normalized degree of centrality scores are 25.652 and 24.348, respectively. Therefore, the anchor-tenants stayed consistent across the three phases. The State Development and Reform Commission and the Ministry of Finance were the most important central actors to co-release PPP policies across the three phases. The main reasons are that PPPs require local governments to raise capital from the market to develop infrastructure and provide fiscal investments and subsidies to PPP projects. These need Ministry of Finance issued polices to guide local governments to regulate and standardize the PPP market. In addition, PPPs focus on key infrastructure-project investment, which is the State Development and Reform Commission’s one main planning function.

The Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (MOHURD, previously known as the Ministry of Construction in PhaseI), the People’s Bank of China, the Banking Regulation Commission, and the State Council played important roles across the three phases. The stability of network members shows the continuity of key policy issuers during the change process in the three phases. Compared to PhaseIandII, Phase III added more actors to the previous co-issuing networks (e.g. the Ministry of Natural Resources, Ministry of Civil Affairs, and Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security), which means more agencies participated in issuing PPP policies.

Second, as shown in Table , co-issuing network structures gradually changed. Specifically, the network-density score gradually enlarged (1.111, 1.534, and 1.952), which means member organizations are developing more connections to each other.Footnote62 Table also shows that the value of network centralization has gradually diminished (33.33%, 30.91%, and 19.92%), which means the co-issuing network gradually took on a decentralized or shared-governance structure. As policy goals and measures gradually became more complex and diverse, more agencies must collaborate to issue polices. Also, a decentralized network helps achieve high and multiple policy goalsFootnote63 because different departments have their own resources and these departments must rely on each other to complete the multiple policy goals and measures.

A refined EG approach with policy layering and learning to PPP policy incremental change

Keeping core policy goals intact and adjusting them from 1988 to 2017 shows an incremental process of a triplex gradual-layering sequence aimed at addressing new policy concerns while retaining the core purpose of private participation in infrastructure. The three layers work progressively to address the core policy purpose of encouraging non-state participation in infrastructure. For example, the policy’s priority in the first phase was to attract foreign investments because domestic private investors were few and weak during that period. Then, beyond the foreign investments, governments needed to attract domestic private investments. After the first two layers were completed, a new layer to better promote PPP development was introduced not only to continue fulfilling the original purposes (i.e. continuing to attract foreign and domestic private investments in infrastructure), but also to improve efficiency, equity, and sustainable development.Footnote64 During the process, policy goals were considered coherent because they logically related to the same overall policy aims. Policy goals in the different phases can be achieved simultaneously.Footnote65

As the refined EG framework suggests, the layering of policy goals in the three stages can be seen as a process of policy learning. Learning is a reaction to changes in external policy environments.Footnote66 Policymakers must adjust policies accordingly as the political and economic environment changes. Before 2014, China’s local governments’ reliance on traditional procurement to build infrastructures and deliver public services resulted in large public debt.Footnote67 The reduction of debts calls for new financing tools. In November 2013, the central government issued plans to encourage private capital to participate in infrastructure investments and operations through franchises. These plans provided an important window of opportunity to adjust previous financial policies. China’s central government then began to promote PPP development on a large scale in 2014. This process aligned with the three conditions of policy learning in a feedback process. One government official we interviewed recalled, ‘Because of the financial crisis in 2008, many local governments did not have financial capital to build infrastructure and deliver public services. Some western and northeastern cities even needed to borrow money from banks to pay civil servants. The tough economic environment forced the central government to adopt PPPs.’

The refined EG approach to PPP policy measures

During the process of changing policy measures from 1988 to 2017, China’s government retained and preserved some primary measures (see Figure ). For example, PPP primary policy measures such as land development, tenders and bids, and franchises (see Figure ) show a layering process. Those primary policy measures are consistent because they work together to support policy goals. In contrast to the primary policy measures, some additional measures were replaced or deleted. For example, the tax incentive (see Figure in Phase I) was an important measure to attract foreign investments in the 1990s; however, it did not treat domestic private investors equally. Thus, the tax-incentive measure induced unfair competition between foreign and domestic investors and was removed in PhasesIIand III. The dynamic change of primary and additional measures indicated that not all policy measures were coherent. Conflicts existed between policy goals and some additional measures. Most important was maintaining coherency between policy goals and primary measures in the layering process.

The PPP gradual policy-measure change from 2014 to 2017 unfolded through a stepwise triplex process in which new policy measures were added to existing ones to strengthen rather than replace them, with consequences for coherence and consistency.Footnote68 The new policy-measure layers did not result in changing policy goals in Phase III, but rather attracted private investors’ participation in PPP markets in a sustainable way. PPP practices from 2014 to 2017 in China demonstrate that a strong status quo bias induces policy conversion through layering.Footnote69 Such policy-measure amendments changed the PPP-development trajectory and expanded existing PPP policies.

A process of learning also drives changes in PPP-policy measures. Under the EG framework, policymakers can learn from experiences in their own past or from their counterparts elsewhere to address current problems.Footnote70 On one hand, China’s PPP policymakers learned from their own past PPP experiences. Because they detected problems and corrected errors, policymakers were able to modify their policy goals and measures in a double loop learning process. This learning-by-doing process enhanced policymakers’ ability to identify, react, and adapt to the changing environment.Footnote71 For example, the development of PPP projects in China in PhaseIrelied on tax incentives to attract foreign investments (see Figure ). However, this policy measure exacerbated local governments’ financial burdens. Therefore, China gradually reduced the tax incentives and refashioned policies to attract domestic private investment in infrastructure in PhaseII.Footnote72 On the other hand, China’s PPP policymakers also learned from experiences in the UK and France. For example, China issued many PPP policy measures in Phase III to manage how to adopt PPPs (see Figure ), such as creating specialized PPP agencies (e.g. learning from the UK’s treasury taskforce) and releasing the municipal utilities franchise (e.g. learning from France’s experience with franchises).Footnote73 According to one expert on China’s PPP policy development, ‘China’s policymakers also learned from the experience of international organizations, such as the United Nations, the World Bank, and the Asian Development Bank, because these international organizations have rich experience in developing PPP projects around the world.’ In short, policy learning occurs when policymakers adjust policy goals or measures in response to past experience and the availability of new information.

The refined EG approach to the PPP policy co-issuing network

The changes in policy co-issuers in the three networks exhibit a process of layering, that is, adding new layers to an existing hierarchy of government, thereby increasing its density of action and institutional complexity.Footnote74 On the one hand, the anchor-tenants maintained consistency; on the other hand, more policy actors joined the policy co-issuing network. Possibly the most consequential challenge was how to coordinate among those departments. To improve coordination and address potential conflicts among PPP policy issuers, the State Council played a pivotal role because it was at the highest level of government, rendering it one of the important actors issuing PPP policies. As PPP projects extended from traditional to high-tech infrastructure, the number of central government departments involved also increased. It may suggest a policy diffusion. However, we focus on the co-issuing and horizontal coordination among government departments to tackle complex or wicked policy issues that often cut across traditional department boundaries.Footnote75 As indicated in Figure , even though more government departments co-issued the policies, the Ministry of Finance and the State Development and Reform Commission remained as core departments in different phases, suggesting a layering rather than a diffusing process.

More extensive agency participation and a decentralized co-issuing network structure can be seen as a collaborative learning strategy. The process of collaborative learning provides positive feedback to reinforce the collaborative network’s vitality. These changes were made to policy co-issuers primarily in response to dissatisfaction with past policy conflicts and fragmentation. The agencies working together learned, over time, how to effectively collaborate, and these lessons became the basis for jointly developing new policies).Footnote76 Another expert we interviewed agreed: ‘More and more agencies jointly participated in PPP policy development. It was a process of collaborative learning to improve policymaking and implementation. To overcome fragmentation, China’s central government has consolidated agencies since 2012. The PPP policies need more agencies to work together.’ Thus, the policy changing co-issuing networks into a more extensive and decentralized structure aligned with the spirit of EG, valuing diversity and collaborative learning.Footnote77

Discussion and conclusion

This article offers a refined EG framework by which future researchers might systematically examine how public policy changes incrementally, as demonstrated in our study of the gradual policy-change process of China’s central government infrastructure PPP policies between 1988 and 2017. We sought to extend the EG framework in two ways: by using policy layering to describe the patterns of incremental policy change and by using policy learning to delineate the process that drives policy change. Through the EG lenses, we reviewed 129 of China’s central government infrastructure PPP policy documents and used a mixed method to process-trace how PPP policies evolved. As shown in our analysis, the infrastructure PPP policy system in China went through three phases: exploration, expansion, and the new boom.

Results showed that changing PPP policy goals, measures, and co-issuing networks followed the refined EG framework where the pattern of policy layering was driven by policy learning over the past 3 decades. China’s infrastructure PPP policy development was an EG process in conformity with China’s reform and opening-up principle of ‘touching stones to cross the river’ (mozhe shitou guo he), which means the reforms proceeded step by step.Footnote78 First, policy goals in the three phases focused on attracting enterprise investments in infrastructure and managing the cooperation between public and private sectors. Policy goals in different phases are progressive and retain coherence, with new goals added to old ones to reinforce them without abandoning or replacing them. Second, to achieve policy goals, some primary measures in the previous phases were retained and used to achieve the policy goals in the new phases. Policymakers learned from their past experiences and from Western countries’ experiences to change policy measures. Third, the policy co-issuing network gradually and densely integrated, yet remained decentralized. After the change, the policy co-issuing network in Phase III became more tightly integrated and displayed more interagency coordination than in Phases I andII. The decentralized structure and greater agency participation were instrumental to policy learning. Learning from diverse PPP experiences, the periodic adjustment of policy goals and measures, and the decentralized policymaking structure aligned the PPP policy change process with EG.

These findings make several theoretical contributions to EG and policy change studies and can be helpful for future infrastructure PPP policymaking in China and other unitary governments. First, this research deepens understanding of incremental policy change theory by tracing the change process in China’s infrastructure PPP policy. Previous policy-change studies mainly focused on policy goals and the process of policy-measure changes.Footnote79 This paper not only enhances understanding of policy co-issuing networks, but also synthesizes the theories of policy layering and policy learning into the EG framework to address the question of how the incremental policy change process unfolds.

Second, this study contributes to the EG framework by unraveling specific detailed patterns underlying China’s infrastructure PPP policy change. Previous EG studies mainly adopted a horizontal structure of learning from separate units’ efforts from the viewpoint of a periodical revision of policy goals and measures. In the current study, we refined the EG perspective to describe the gradual changing goals, measures, and co-issuing networks. We articulated a fine-grained EG approach to incremental policy change as a layering process driven by policy learning. Therefore, the integration of external manifestations of the policy layering process and the internal motivation of policy learning, as demonstrated in China’s infrastructure PPP policy change, extends EG theory.

Third, this research has some practical implications for China’s infrastructure PPP policymakers. China’s policymakers may continue to revise infrastructure investment policies in the future but should transform policy goals and measures gradually to maintain the continuity of policies. Since 2017, ‘standardization’ has become the key word in China’s infrastructure PPP policies. Greater standardization will be instrumental to investors’ participation. This new policy measure aligns with the World Economic Forum’sFootnote80 recommendation for infrastructure investment policy. The forum has promoted PPP standardization to reduce the many barriers to bidders, such as poor governance structures, excessive information requests, and changing project structures or scopes. Therefore, China’s policymakers should continue to cooperate with the United Nations and other international organizations to standardize infrastructure procurement, implementation, and operational processes at a regional or even global level.

The evolving trajectory of China’s PPP policies may provide a lesson for other countries. China’s PPP policy development is a layering and learning process; therefore, the long-term process can be seen as a temporal factor to address policy sequencing in policy design.Footnote81 For example, the three phases of PPP policies in China highlight the continuity of PPP policy goals: to attract domestic and foreign investments in infrastructure, and to better manage their investment in the PPP market. These PPP development approaches provide lessons or experiences for other developing countries, especially unitary governments, to design PPP policies.

This article, however, has two limitations. First, as a unitary government, China’s central government focuses on policymaking and local governments are responsible for policy implementation. Future work may study a bottom-up policy diffusion (as suggested by Shipan and Volden),Footnote82 which combines central and local PPP policies and explores how the interaction between central and local governments affects central PPP policy changes and PPP project implementation. Second, an examination of the EG theoretical framework on incremental policy change through a single case study will always be incomplete. As a single-case method, PT only allows inferences about the operation of the mechanism within the studied case because of the evidence gathered through tracing the process in the case. To generalize beyond the studied case, future research must couple PT case studies with comparative methods to enable us to generalize about causal processes. A refined theoretical framework, such as EG, to incremental policy change deserves exploration across other policy domains in different countries.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Huanming Wang

Huanming Wang is a professor in the department of Public Administration, Dalian University of Technology. His research interests include public-private partnerships, governance network, urban governance, and co-production. Email: [email protected]

Bin Chen

Bin Chen is a professor in the Austin W. Marxe School of Public and International Affairs, Baruch College, and a doctoral faculty at The Graduate Center, The City University of New York. His research interests include cross-sectoral governance and interorganizational collaboration in public policy implementation, government-nonprofit relations, regional networked governance, comparative public administration and public policy, with a methodological focus on social network analysis and qualitative comparative analysis. Email: [email protected] (corresponding author)

Joop Koppenjan

Joop Koppenjan is a professor in the department of Public Administration and Society, Erasmus University Rotterdam. His research interests include public-private partnerships, governance network, decision making and policy implementation, and democratic governance in policy networks. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Hall, “Policy Paradigms, Social Learning, and the State,” 275–296.

2 Capano, “Understanding Policy Change as an Epistemological and Theoretical Problem,” 7–31; Van de Ven and Poole, “Explaining Development and Change in Organizations,” 510–540.

3 See note 1 above; Moyson et al., “Policy Learning and Policy Change,” 161–177.

4 Linder and Peters, “Instruments of Government,” 35–58.

5 James and Nakamura, “Shared Performance Targets for the Horizontal Coordination of Public Organizations,” 392–411.

6 Sabel and Zeitlin, “Learning from Difference”; Sabel and Zeitlin, “Experimentalist Governance.”

7 Schlager and Blomquist, “A Comparison of Three Emerging Theories of the Policy Process,” 651–672.

8 Sabel and Zeitlin, “Experimentalist Governance.”

9 Overdevest and Zeitlin, “Assembling an Experimentalist Regime,” 22–48.

10 Heilmann et al., “National Planning and Local Technology Zones,” 896–919; Shin, “Neither Centre nor Local,” 607–633; Zhu and Zhao, “Experimentalist Governance with Interactive Central-Local Relations,” 13–36.

11 Klijn and Teisman, “Institutional and Strategic Barriers to Public-Private Partnership,” 137–146; Linder, “Coming to Terms with the Public-Private Partnership,” 35–51.

12 Akintoye et al., Public-Private Partnerships; Hodge and Greve, “On Public-Private Partnership Performance,” 55–78; Verhoest et al., “How Do Governments Support the Development of Public Private Partnerships?,” 118–139.

13 In this paper, we focus on PPP polices and projects in Mainland China. Hong Kong is part of China and is a main city to use PPPs to develop infrastructure, but it has different legal and regulatory regimes from Mainland China under ‘one country two systems’.

14 Chen et al., “When Public-Private Partnerships Fail,” 839–857; Wang et al., “Government Support Programs and Private Investment in PPP Markets,” 499–523.

15 See note 1 above.

16 Garcia, “Grid-Connected Renewable Energy in China,” 8046–8050.

17 See note 1 above.

18 Sabel and Zeitlin, “Learning from Difference,” 271–327.

19 Borzel, “Experimentalist Governance in the EU,” 378–384.

20 Mendez, “The Lisbonization of EU Cohesion Policy,” 519–537.

21 Rangoni, “Architecture and Policy-Making,” 63–82.

22 Mahoney and Thelen, “A Theory of Gradual Institutional Change”; Streeck and Thelen, “Introduction.”

23 Hong et al., “Measuring Social Policy Change in Comparative Research,” 131–150.

24 Beland, “Ideas and Institutional Change in Social Security,” 20–38.

25 Parker and Parenta, “Explaining Contradictions in Film and Television Industry Policy,” 609–622.

26 Mahoney and Thelen, “A Theory of Gradual Institutional Change.”

27 Rocco and Thurston, “From Metaphors to Measures,” 35–62.

28 Daugbjerg and Swinbank, “Three Decades of Policy Layering and Politically Sustainable Reform in the European Union’s Agricultural Policy,” 265–280.

29 See note 1 above.

30 See note 8 above.

31 Bick, “Institutional Layering, Displacement, and Policy Change,” 342–360.

32 See note 1 above.

33 Laakso et al., “Dynamics of Experimental Governance,” 8–16.

34 See note 17 above.

35 See note 20 above.

36 Dunlop and Radaelli, “The Lessons of Policy Learning,” 255–272.

37 See note 1 above; Moyson et al., “Policy Learning and Policy Change,” 161–177; Zittoun, “Understanding Policy Change as a Discursive Problem,” 65–82.

38 Beach and Pedersen, Process-Tracing Methods.

41 Cheng et al., “Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Public Private Partnership Projects in China,” 1242–1251; Wang et al., “Public-Private Partnership in Public Administration Discipline,” 293–316.

42 Chen and Li, “Policy Change and Policy Learning in China’s Public-Private Partnership,” 102–107.

43 Cheng et al., “Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Public Private Partnership Projects in China,” 1242–1251.

44 Jones and Baumgartner, “From There to Here,” 1–20.

45 See note 39 above.

46 Santandrea et al., “Value for Money in UK Healthcare Public-Private Partnerships,” 260–279.

47 Wasserman and Katherine, Social Network Analysis.

48 See note 1 above.

49 Haas, “Introduction,” 1–35; He, “Manoeuvring Within a Fragmented Bureaucracy,” 1088–1110; Mintrom and Norman, “Policy Entrepreneurship and Policy Change,” 649–667.

50 Tan and Zhao, “The Rise of Public-Private Partnerships in China,” 514–518.

51 See note 40 above.

52 Urpelainen and Yang, “Policy Reform and the Problem of Private Investment,” 38–64.

53 Taeihagh, “Network-Centric Policy Design,” 317–338.

54 Givoni et al., “From Individual Policies to Policy Packaging”; Howlett, Designing Public Polices.

55 Givoni et al., “From Individual Policies to Policy Packaging.”

56 See note 40 above.

57 Kelman, “Strategic Contracting Management.”

58 Mouraviev and Kakabadse, “Public-Private Partnerships in Russia,” 79–96; Yang et al., “On the Development of Public-Private Partnerships in Transitional Economies,” 301–310.

59 Van den Hurk, “Learning to Contract in Public-Private Partnerships for Road Infrastructure,” 309–333.

60 Scott, Social Network Analysis.

61 South et al., “How Infrastructure Public-Private Partnership Projects Change Over Project Development Phases,” 62–80.

62 Provan and Sebastian, “Networks Within Networks,” 453–463.

63 Cristofoli and Markovic, “How to Make Public Networks Really Work,” 89–110.

64 Koppenjan and Enserink, “Public-Private Partnerships in Urban Infrastructures,” 284–296; Pinz et al., “Public-Private Partnerships as Instruments to Achieve Sustainability-Related Objectives,” 1–22.

65 Kern and Howlett, “Implementing Transaction Management as Policy Reforms,” 391–408.

66 Bennett and Howlett, “The Lessons of Learning,” 275–294.

68 Rayner and Howlett, “Introduction,” 99–109.

69 Shpaizman, “Ideas and Institutional Conversion Through Layering,” 1038–1053.

70 See note 39 above; Rose, “What is Lesson-Drawing?,” 3–30.

71 Moyson et al., “Policy Learning and Policy Change,” 161–177.

72 See note 39 above.

73 Cheng et al., “Diversification or Convergence,” 1315–1335; Huang, “Practical Experience of PPP Model in France and Its Referential Meaning to China,” 17–21.

74 Capano, “Reconceptualizing Layering-From Mode of Institutional Change to Mode of Institutional Design,” 590–604; Van der Heijden, “Institutional Layering,” 9–18.

75 See note 5 above.

76 Ansell and Gash, “Collaborative Platforms as a Governance Strategy”; Chen, “Antecedents or Processes?,” 381–407.

77 Fossum, “Reflections on Experimentalist Governance,” 394–400.

78 Schoon, “Chinese Strategies of Experimental Governance,” 194–199.

79 See note 64 above; See note 50 above.

80 World Economic Forum, “Infrastructure Investment Policy Blueprint.”

81 See note 50 above.

82 Shipan and Volden, “Bottom-up Federalism,” 825–843.

References

- Akintoye, Akintola, Beck Matthias, and Cliff Hardcastle. Public-Private Partnerships: Managing Risks and Opportunities. Oxford: Blackwell, 2003.

- Ansell, Chris, and Alison Gash. “Collaborative Platforms as a Governance Strategy.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 28, no. 1 (2018): 16–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mux030.

- Beach, Derek, and Rasmus Brun Pedersen. Process-Tracing Methods. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013.

- Beland, Daniel. “Ideas and Institutional Change in Social Security: Conversion, Layering, and Policy Drift.” Social Science Quarterly 88, no. 1 (2007): 20–38.

- Bennett, Colin J., and Michael Howlett. “The Lessons of Learning: Reconciling Theories of Policy Learning and Policy Change.” Policy Sciences 25, no. 3 (1992): 275–294. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00138786.

- Bick, Etta. “Institutional Layering, Displacement, and Policy Change: The Evolution of Civic Service in Israel.” Public Policy and Administration 31, no. 4 (2016): 342–360. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0952076715624272.

- Borzel, Tanja A. “Experimentalist Governance in the EU: The Emperor’s New Clothes?” Regulation & Governance 6 (2012): 378–384.

- Capano, Giliberto. “Understanding Policy Change as an Epistemological and Theoretical Problem.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 11, no. 1 (2009): 7–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13876980802648284.

- Capano, Giliberto. “Reconceptualizing Layering- From Mode of Institutional Change to Mode of Institutional Design: Types and Outputs.” Public Administration 97, no. 3 (2019): 590–604. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12583.

- Chen, Bin. “Antecedents or Processes? Determinants of Perceived Effectiveness of Inter-Organizational Collaborations for Public Service Delivery.” International Public Management Journal 13, no. 4 (2010): 381–407. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2010.524836.

- Chen, Cheng, and Dan Li. “Policy Change and Policy Learning in China’s Public-Private Partnership: Content Analysis of PPP Policies Between 1980 and 2015.” Chinese Public Administration 2 (2017): 102–107. (in Chinese)

- Cheng, Zhe, Yongjian Ke, Jing Lin, Zhenshan Yang, and Jianming Cai. “Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Public Private Partnership Projects in China.” International Journal of Project Management 34, no. 7 (2016): 1242–1251. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2016.05.006.

- Cheng, Zhe, Yongjian Ke, Zhenshan Yang, Jianming Cai, and Huanming Wang. “Diversification or Convergence: An International Comparison of PPP Policy and Management Between the UK, India, and China.” Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 27, no. 6 (2020): 1315–1335. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-06-2019-0290.

- Chen, Cheng, Michael Hubbard, and Chun-Sung Liao. “When Public-Private Partnerships Fail.” Public Management Review 15, no. 6 (2013): 839–857. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2012.698856.

- Cristofoli, Daniela, and Josip Markovic. “How to Make Public Networks Really Work: A Qualitative Comparative Analysis.” Public Administration 94, no. 1 (2016): 89–110. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12192.

- Daugbjerg, Carsten, and Alan Swinbank. “Three Decades of Policy Layering and Politically Sustainable Reform in the European Union’s Agricultural Policy.” Governance 29, no. 2 (2016): 265–280. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12171.

- Dunlop, Claire A., and Claudio M. Radaelli. “The Lessons of Policy Learning: Types, Triggers, Hindrances and Pathologies.” Policy & Politics 46, no. 2 (2018): 255–272. doi:https://doi.org/10.1332/030557318X15230059735521.

- Fossum, John E. “Reflections on Experimentalist Governance.” Regulation & Governance 6, no. 3 (2012): 394–400. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5991.2012.01158.x.

- Garcia, Clara. “Grid-Connected Renewable Energy in China: Policies and Institutions Under Gradualism, Developmentalism, and Socialism.” Energy Policy 39 (2011): 8046–8050.

- Givoni, Moshe, Macmillen James, and Banister David. 2010. “From Individual Policies to Policy Packaging.” In European Transport Conference. Glasgow Scotland.

- Haas, Peter M. “Introduction: Epistemic Communities and International Policy Coordination.” International Organization 46, no. 1 (1992): 1–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300001442.

- Hall, Pater A. “Policy Paradigms, Social Learning, and the State: The Case of Economic Policymaking in Britain.” Comparative Politics 25, no. 3 (1993): 275–296. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/422246.

- He, Alex Jingwei. “Manoeuvring Within a Fragmented Bureaucracy: Policy Entrepreneurship in China’s Local Healthcare Reform.” The China Quarterly 236 (2018): 1088–1110. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741018001261.

- Heilmann, Sebastian, Lea Shih, and Andreas Hofem. “National Planning and Local Technology Zones: Experimental Governance in China’s Torch Programme.” The China Quarterly 216 (2013): 896–919. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741013001057.

- Hodge, Graeme A., and Carsten Greve. “On Public-Private Partnership Performance: A Contemporary Review.” Public Works Management & Policy 22, no. 1 (2017): 55–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1087724X16657830.

- Hong, Ijin, Eunsun Kwon, and Borin Kim. “Measuring Social Policy Change in Comparative Research: Survey Data Evidence from South Korea.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 21, no. 2 (2019): 131–150. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2017.1418207.

- Howlett, Michael. Designing Public Polices: Principles and Instruments. Milton Park: Taylor & Francis, 2010.

- Huang, Xiaojun. “Practical Experience of PPP Model in France and Its Referential Meaning to China.” China Water & Wastewater 33 (2017): 17–21. (in Chinese)

- James, Oliver, and Ayako Nakamura. “Shared Performance Targets for the Horizontal Coordination of Public Organizations: Control Theory and Departmentalism in the United Kingdom’s Public Service Agreement System.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 81, no. 2 (2015): 392–411. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852314565998.

- Jones, Bryan D., and Frank R. Baumgartner. “From There to Here: Punctuated Equilibrium to the General Punctuation Thesis to a Theory of Government Information Processing.” Policy Studies Journal 40, no. 1 (2012): 1–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00431.x.

- Kelman, Steven. “Strategic Contracting Management.” In Market-Based Governance: Supply Side, Demand Side, Upside, and Downside, edited by John D. Donahue and Joseph S. Nye. Washington, DC: Brookings Institute Press, 2002.

- Kern, Florian, and Michael Howlett. “Implementing Transaction Management as Policy Reforms: A Case Study of the Dutch Energy Sector.” Policy Sciences 42, no. 4 (2009): 391–408. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-009-9099-x.

- Klijn, Erik-Hans, and Geert R. Teisman. “Institutional and Strategic Barriers to Public-Private Partnership: An Analysis of Dutch Cases.” Public Money and Management 23, no. 3 (2003): 137–146. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9302.00361.

- Koppenjan, Joop, and Bert Enserink. “Public-Private Partnerships in Urban Infrastructures: Reconciling Private Sectors Participation and Sustainability.” Public Administration Review 69, no. 2 (2009): 284–296. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2008.01974.x.

- Laakso, Senja, Annukka Berg, and Mikko Annala. “Dynamics of Experimental Governance: A Meta-Study of Functions and Uses of Climate Governance Experiments.” Journal of Cleaner Production 169 (2017): 8–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.04.140.

- Linder, Stephen H. “Coming to Terms with the Public-Private Partnership: A Grammar of Multiple Meanings.” American Behavioral Scientist 43, no. 1 (1999): 35–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/00027649921955146.

- Linder, Stephen H., and B. Guy Peters. “Instruments of Government: Perceptions and Contexts.” Journal of Public Policy 9, no. 1 (1989): 35–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00007960.

- Mahoney, James, and Kathleen Thelen. 2010. “A Theory of Gradual Institutional Change.” In Explaining Institutional Change: Ambiguity, Agency, and Power, edited by Mahoney, James, and Kathleen Thelen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mendez, Carlos. “The Lisbonization of EU Cohesion Policy: A Successful Case of Experimentalist Governance?” European Planning Studies 19, no. 3 (2011): 519–537. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2011.548368.

- Mintrom, Michael, and Phillipa Norman. “Policy Entrepreneurship and Policy Change.” Policy Studies Journal 37, no. 4 (2009): 649–667. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2009.00329.x.

- Mouraviev, Nikolai, and Nada K. Kakabadse. “Public-Private Partnerships in Russia: Dynamics Contributing to an Emerging Policy Paradigm.” Policy Studies 35, no. 1 (2014): 79–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2013.875140.

- Moyson, Stephane, Peter Scholten, and Christopher M. Weible. “Policy Learning and Policy Change: Theorizing Their Relations from Different Perspective.” Policy and Society 36, no. 2 (2017): 161–177. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2017.1331879.

- Overdevest, Christine, and Jonathan Zeitlin. “Assembling an Experimentalist Regime: Transnational Governance Interactions in the Forest Sector.” Regulation & Governance 8, no. 1 (2014): 22–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5991.2012.01133.x.

- Parker, Rachel, and Oleg Parenta. “Explaining Contradictions in Film and Television Industry Policy: Ideas and Incremental Policy Change through Layering and Drift.” Media, Culture & Society 30, no. 5 (2008): 609–622. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443708094011.

- Pinz, Alexander, Nahid Roudyani, and Julia Thaler. “Public-Private Partnerships as Instruments to Achieve Sustainability-Related Objectives: The State of the Art and a Research Agenda.” Public Management Review 20, no. 1 (2018): 1–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1293143.

- Provan, Keith G., and Juliann G. Sebastian. “Networks Within Networks: Service Link Overlap, Organizational Cliques, and Network Effectiveness.” Academy of Management Journal 41, no. 4 (1998): 453–463. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/257084.

- Rangoni, Bernardo. “Architecture and Policy-Making: Comparing Experimentalist and Hierarchical Governance in EU Energy Regulation.” Journal of European Public Policy 26, no. 1 (2019): 63–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1385644.

- Rayner, Jeremy, and Michael Howlett. “Introduction: Understanding Integrated Policy Strategies and Their Evolution.” Policy and Society 28, no. 2 (2009): 99–109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2009.05.001.

- Rocco, Philip, and Chloe Thurston. “From Metaphors to Measures: Observable Indicators of Gradual Institutional Change.” Journal of Public Policy 34, no. 1 (2014): 35–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X13000305.

- Rose, Richard. “What is Lesson-Drawing?” Journal of Public Policy 11, no. 1 (1991): 3–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00004918.

- Sabel, Charles F., and Jonathan Zeitlin. “Experimentalist Governance.” In The Oxford Handbook of Governance, edited by D. Levi-Faur. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Sabel, Charles F., and Jonathan Zeitlin. “Learning from Difference: The New Architecture of Experimentalist Governance in the EU.” European Law Journal 14, no. 3 (2008): 271–327. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0386.2008.00415.x.

- Santandrea, Martina, Stephen Bailey, and Marco Giorgino. “Value for Money in UK Healthcare Public-Private Partnerships: A Fragility Perspective.” Public Policy and Administration 31, no. 3 (2016): 260–279. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0952076715618003.

- Schlager, Edella, and William Blomquist. “A Comparison of Three Emerging Theories of the Policy Process.” Political Research Quarterly 49, no. 3 (1996): 651–672. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/449103.

- Schoon, Sonia. “Chinese Strategies of Experimental Governance: The Underlying Forces Influencing Urban Restructuring in the Pearl River Delta.” Cities 41 (2014): 194–199. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2014.01.008.

- Scott, John. Social Network Analysis. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Sage, 2013.

- Shin, Kyoung. “Neither Centre nor Local: Community-Driven Experimentalist Governance in China.” The China Quarterly 231 (2017): 607–633. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741017000923.

- Shipan, Charles R., and Craig Volden. “Bottom-up Federalism: The Diffusion of Antismoking Policies from U.S. Cities to States.” American Journal of Political Science 50, no. 4 (2006): 825–843. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00218.x.

- Shpaizman, Ilana. “Ideas and Institutional Conversion Through Layering: The Case of Israeli Immigration Policy.” Public Administration 92, no. 4 (2014): 1038–1053. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12112.

- South, Andrew, Kent Eriksson, and Raymond Levitt. “How Infrastructure Public-Private Partnership Projects Change over Project Development Phases.” Project Management Journal 49, no. 4 (2018): 62–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/8756972818781712.

- Streeck, Wolfgang, and Kathleen Thelen. 2005. “Introduction: Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies.” In Beyond Continuity: Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies, edited by Wolfgang Streeck and Kathleen Thelen. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Taeihagh, Araz. “Network-Centric Policy Design.” Policy Sciences 50, no. 2 (2017): 317–338. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-016-9270-0.

- Tan, Jie, and Jerry Zhirong Zhao. “The Rise of Public-Private Partnerships in China: An Effective Financing Approach for Infrastructure Investment.” Public Administration Review 79, no. 4 (2019): 514–518. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13046.

- Urpelainen, Johannes, and Joonseok Yang. “Policy Reform and the Problem of Private Investment: Evidence from the Power Sector.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 36, no. 1 (2017): 38–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.21959.

- Van de Ven, Andrew H., and Marshall Scott Poole. “Explaining Development and Change in Organizations.” The Academy of Management Review 20, no. 3 (1995): 510–540. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/258786.

- Van den Hurk, Martijn. “Learning to Contract in Public-Private Partnerships for Road Infrastructure: Recent Experiences in Belgium.” Policy Sciences 49, no. 3 (2016): 309–333. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-015-9240-y.

- Van der Heijden, Jeroen. “Institutional Layering: A Review of the Use of the Concept.” Politics 31, no. 1 (2011): 9–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9256.2010.01397.x.

- Verhoest, Koen, Ole Helby Petersen, Walter Scherrer, and Raden Murwantara Soecipto. “How Do Governments Support the Development of Public Private Partnerships? Measuring and Comparing PPP Governmental Support in 20 European Countries.” Transport Reviews 35, no. 2 (2015): 118–139. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2014.993746.

- Wang, Huanming, Yuhai Liu, Wei Xiong, and Dajian Zhu. “Government Support Programs and Private Investment in PPP Markets.” International Public Management Journal 22, no. 3 (2019): 499–523. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2018.1538025.

- Wang, Huanming, Wei Xiong, Guangdong Wu, and Dajian Zhu. “Public-Private Partnership in Public Administration Discipline: A Literature Review.” Public Management Review 20, no. 2 (2018): 293–316. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1313445.

- Wasserman, Stanley, and Katherine Faust. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- World Economic Forum. 2014. “Infrastructure Investment Policy Blueprint.” http://120.52.51.14/www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_II_InfrastructureInvestmentPolicyBlueprint_Report_2014.pdf

- Yang, Yongheng, Yilin Hou, and Youqiang Wang. “On the Development of Public-Private Partnerships in Transitional Economies: An Explanatory Framework.” Public Administration Review 73, no. 2 (2013): 301–310. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02672.x.

- Zhu, Xufeng, and Hui Zhao. “Experimentalist Governance with Interactive Central-Local Relations: Making New Pension Policies in China.” Policy Studies Journal 49, no. 1 (2021): 13–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12254.

- Zittoun, Philippe. “Understanding Policy Change as a Discursive Problem.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 11, no. 1 (2009): 65–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13876980802648235.