Abstract

This article reviews the history and working mode of the Central Commission for Comprehensively Deepening Reform (CCCDR) to shed light on the underpinnings of ‘top-level design’ in China’s policy process. We demonstrate the paradoxical nature of the CCCDR’s ‘hard steering’: on the one hand, agenda-setting and the creation of major reform policies has been centralized and highly formalized; on the other hand, local circumstances are not adequately taken into account, resulting in low resource-efficiency in policy implementation. This article makes an important contribution to our understanding of the Chinese policy process under conditions of ‘top-level design’. By showing how political steering is conducted at the central level and by drawing on a case study, we also critically assess the CCP’s governing capacity in the Xi Jinping era.

Introduction

Reform has been a central focus of the CCP’s governing strategy since the late 1970s. The concept of ‘deepening reform’ emerged as a political signal to underscore the Party’s commitment to avoiding institutional stagnation and has been consistently emphasized by China’s top leaders since the 1980s. In the initial decades of the ‘reform and opening up’ period, the prevailing approach to reform was described by the slogan ‘crossing the river by touching the stones’. This metaphorical description highlighted a cautious reform strategy without a fixed roadmap, that encouraged local government officials to initiate and implement policy measures to address local issues. Experimenting with local policy and the replicating successful models across the country are crucial governance techniques of the CCP and a significant contributor to the longevity of one-party rule in China (Heilmann Citation2018; Teets and Hasmath Citation2020).

However, the CCP also has a longstanding tradition of top-down planning, which feeds into the central leadership’s aspiration for comprehensive policy guidance. This has created tension between agenda-setting and policy design at the central level, and policy implementation at the local level. This tension reflects the complex relationship between the central and local levels in the Chinese political system, which is arguably the most critical factor for regime stability and legitimacy in post-Mao China (Li Citation2010; Oi Citation2020). As the saying goes, excessive decentralization and loosening (fang) can lead to chaos, while excessive tightening of power (shou) at the top can result in deadlock (yifang jiuluan, yiguan jiusi). In fact, striking a balance between fang and shou, or finding a middle ground between top-down guidance and bottom-up initiative, has been an ongoing challenge for Chinese policymaking since the early days of China’s reform (Chen Citation2017).

After three decades of incremental and cautious reform, a new strategy based on ‘top-level design’ (dingceng sheji) was introduced towards the end of the Hu-Wen era in 2010. This approach aimed to address the problem of scattered and selective policy implementation nationwide.Footnote1 In the early stages of his tenure as CCP General Secretary, during a visit to Guangdong in December 2012, Xi Jinping highlighted the importance of a roadmap and timetable for comprehensively deepening reform (Xi Citation2018a). He also stated that ‘to address a series of significant contradictions and challenges facing China’s further development, we must deepen reform and opening up’ (Xi Citation2018b). Subsequently, the concept of ‘top-level design’ (TLD) emerged as the primary approach to China’s policy process. It was embodied in the ‘Decision of the CPC Central Committee on Several Major Issues Concerning the Comprehensive Deepening of Reform’ (referred to as the ‘Decision’), adopted during the Third Plenary Session of the 18th CCP Central Committee in November 2013. The introduction of TLD led to the establishment of the Central Leading Group for Comprehensively Deepening Reform (CLGCDR/Zhongyang shenhua gaige lingdao xiaozu), which is discussed in this article. Obviously, Xi Jinping took the task of centralizing coordination in the policy process seriously, aligning with the urgency articulated by his predecessors at the Party’s helm in shaping China’s future reform path by more steering from the top.

At first glance, the governance mode of ‘top-level design’ (TLD) appears to have diminished a long period of bottom-up ‘experimentation under hierarchy’ during the Hu Jintao era, which was loosely guided by the Party center (Ahlers and Schubert Citation2022). According to the official narrative, after four decades of relatively decentralized policymaking, China encountered formidable challenges that could only be effectively addressed through the systematic centralization of policymaking. This centralization was seen as a prerequisite for overcoming vested interests and ideological barriers (Xi Citation2018c). Specifically, the widespread dispersion of policy initiatives and implementation at the local level had resulted in an uncoordinated reform landscape and eroded the authority of the central leadership. Moreover, public policy in China had become highly departmentalized, characterized by a complicated interplay between horizontal and vertical command lines, commonly known as the ‘tiao-kuai’ system. This system reflected what was called ‘fragmented authoritarianism’ (Lieberthal and Ochsenberg Citation1988) in Western terms or the ‘departmentalization of public power’ (gongong guanli bumenhua) in Chinese Party speak.Footnote2 The implementation of ‘top-level design’ aimed to facilitate a smoother interaction between the ‘tiao’ (departments) and ‘kuai’ (units), curb the influence of parochial interests within central bureaucracies and local governments, and reestablish the authority of the party-state center. It was believed that a more centralized approach would enhance coordination and enable the party state to tackle complex challenges more effectively.

The concerns about inefficiency in policymaking at the end of the Hu-Wen era were not unfounded. Fragmented policymaking has two dimensions. One is fragmented policy formulation by different ministries at the central level. The prevalence of vertical command lines, which make up over 50 percent of the national ministries (Li Citation2009; Zhou and Li Citation2009), has long been recognized as a significant contributing factor to the crisis in local governance that was widely acknowledged within the party state leadership when Xi Jinping assumed power (Baranovitch Citation2021). The central government exercises vertical control over powerful and resource-rich ministries, such as the State Taxation Administration and the State Administration for Market Regulation. Over time, this has led to an expansion of regulatory authority and increased corruption within the subordinate line departments of each vertical system across different administrative tiers (Gao Citation2013). As local governments face significant limitations in their regulatory authority over the operations of these departments, there was widespread frustration in local policymaking, as line departments could easily block local reform initiatives. This impacted negatively on the central government’s control as local governments sought to circumvent the interference of line departments in their policy agendas (Zhao Citation2013).

The other dimension refers to selective policy implementation on the local level and fragmented policy outcomes due to diverging interests of subordinate governments. Moreover, economic growth in many developed regions of China has strengthened the fiscal independence of local governments, further loosening their ties with the central government. Finally, the principle of ‘managing cadres one level below’ (ganbu xiaguan yiji) has significantly restricted the central government’s oversight of personnel over the years. After three decades of accumulating reform experience, the new leadership under Xi Jinping came to the conclusion that the strategy of ‘crossing the river by touching the stones’ should be combined with a more systematic approach. In essence, ‘top-level design’ was pursued to address issues of uncoordinated agenda-setting, fragmented policy formulation, and selective policy implementation. It aimed to control rent-seeking interest groups and strengthen central authority in the policy process, thus overcoming the shortcomings of a highly fragmented party state bureaucracy.

This article reviews the history and operating mode of ‘top-level design’ in China’s policy process by zooming in on the Central Commission for Comprehensively Deepening Reform (CCCDR). Drawing on Political Steering Theory, we look at how agenda-setting by the CCCDR translates into policy formulation at ministerial level. We find that ‘hard steering’ by the CCCDR is realized through heightened leadership attention and informal communication with steering objects, financial incentives, continuous performance evaluation and tight supervision, while the response of central ministries and local governments highlights different coping strategies. However, the paucity of our data on the latter allows only sporadic analysis of local policy implementation.

Our findings demonstrate that CCCDR ‘hard steering’ has rendered central-level policy formulation more consistent. However, local circumstances are not adequately taken into account by steering from the top, resulting in low resource-efficiency when implementing policies. Therefore, as our case study on the ‘Three-Year Action Plan on Rural Living Environment Improvement’ (Nongcun renju huanjing zhengzhi sannian xingdong fangan, 农村人居环境整治三年行动方案)Footnote3 suggests, while TLD may succeed in streamlining the policy process at the upper tiers of the Chinese tizhi, it cannot guarantee effective implementation of central-level policies on the ground. Our analysis draws on official documents issued by the party state leadership (the center) passed down to lower-level governments for further processing and interviews with officials responsible for local policy-implementation.Footnote4

Analytical framework: political steering

Drawing upon Political Steering Theory, which has recently emerged as a valuable framework for examining China’s governance mode of ‘top-level design’ (Schubert and Alpermann Citation2019), this study focuses on the concept of ‘hard steering’ within the Chinese policy process. Political Steering Theory, originally developed by German scholars in the 1970s, explores the conditions necessary for effective state intervention or guidance to address social, economic, and political issues within a given society. By applying this theory, we can gain a deeper understanding of the Chinese policy process in the context of the ‘New Normal’ and the specific role of the CCCDR as the core institution of ‘top-level design’ in the Chinese ‘partocracy’ (Guo Citation2020).

‘Hard steering’ is one of several steering modes employed by a government to achieve its policy objectives. Within Political Steering Theory, it is conceptually distinct from ‘negotiation’, ‘competition’, and ‘soft steering’, and refers to top-down state intervention in the policy process to ensure that central state objectives are effectively implemented by local governments with minimal deviation.Footnote5 In an ideal scenario, ‘hard steering’ entails systematic command and control, limited consultation with lower-level government bureaucracies, and the utilization of various steering instruments and tactics to streamline the policy process. These include mobilization through political campaigns, the use of ‘signal politics’ (such as anti-corruption campaigns), supervision via inspections, and regular performance evaluation (Heffer and Schubert Citation2023). ‘Hard steering’ therefore emphasizes strict upper-level guidance to ensure consistent policy implementation throughout the country.

Political Steering Theory zooms in on the interactions between steering subjects and steering objects throughout the administrative hierarchy. It examines how those in higher positions attempt to steer, while those in lower positions respond through compliance, shirking, coping, or even counter-steering. These dynamics shape policy outcomes, reflecting the level of state capacity and system governability. The main objective of this article is to provide a detailed analytical description of ‘hard steering’ in the Xi Jinping era, zooming in on agenda-setting and policy formulation at the central level. Our analysis centers around the Central Commission for Comprehensively Deepening Reform (CCCDR) as a prominent steering subject. We examine the CCCDR’s major functions in agenda-setting and policy formulation and focus on its guidance of policy implementation and evaluation. Specifically, we investigate the overall operational mode of the CCCDR by shedding light on its internal working mechanisms and processes. We also present a case study on the CCCDR’s design of the ‘Three-Year Action Plan for Rural Living Environment Improvement’, a significant national policy. By focusing on these aspects, we aim to provide a more comprehensive understanding of ‘hard steering’ in the Xi Jinping era than has so far been offered by the scant literature on the CCCDR.Footnote6

Brief account of the CCCDR’s historical background

The establishment of the State Council System Reform Office (Guowuyuan tizhi gaige bangongshi) in 1980 marked the initiation of Deng Xiaoping’s ‘reform and opening up’ project (Deng Citation1988). This office was later upgraded to the National Commission for Restructuring the Economic System (NCRES, Tigaiwei) in 1982. Led by the Premier of the State Council, the Tigaiwei was entrusted with the task of designing economic reforms, coordinating efforts among government departments, conducting policy pilots, and providing overall guidance for reform implementation across the country. Ministries and commissions were required to seek advice and comments from the Tigaiwei before their reform initiatives could be included in the State Council’s working agenda. The Tigaiwei played an active role in initiating significant economic reforms and providing the ideological foundations for these reforms. It introduced concepts such as the ‘socialist commodity economy’ and spearheaded reforms in areas such as the shareholding system in state-owned enterprises (SOEs), the financial system, urban housing, land reform, and social welfare provision in both urban and rural areas. Shao Bingren, a former deputy director of the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), noted that the former Tigaiwei had no vested interests and lacked definitive approval authority. Its primary objective was to promote reform.Footnote7 These early institutions laid the groundwork for China’s subsequent economic transformation and set the stage for the central leadership’s role in guiding and driving the reform process. In 1998, during a reorganization and streamlining of central government entities, the Tigaiwei was downgraded to an office (Tigaiban) and ceased to be a subordinate agency of the State Council.Footnote8 Then, in March 2003, the Tigaiban was incorporated into the newly established National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC/Guojia fazhan gaige weiyuanhui). The NDRC quickly gained prominence and became a significant government organization that many scholars in the West refer to when analyzing Chinese national policymaking (Heilmann and Melton Citation2013). In the Hu-Wen era, the NDRC assumed the core responsibility of approving reform initiatives and became the highest authority in designing major economic reform policies.

However, in March 2012, Chi Fulin, who had previously worked for the Tigaiwei, proposed the establishment of a central-level reform coordination organization during the sessions of the National People’s Congress (NPC) and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC). As a member of the CPPCC National Committee, Chi expressed the need for a broader portfolio for the NDRC, stating that as reforms entered a more complex phase with diverse interests and increased social conflicts, the NDRC alone was unable to mediate tensions within the social system.Footnote9 Following this proposal, in April 2013, Gao Shangquan, a former deputy director of the Tigaiwei, submitted suggestions for the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee. Gao recommended the establishment of a high-level coordination mechanism to implement China’s policy reforms. As a result, the ‘Central Leading Group for Comprehensively Deepening Reform’ (CLGCDR or Zhongyang quanmian shenhua gaige lingdao xiaozu) was established in the early days of the Xi Jinping era. This leading group was headed by the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), with the Premier of the State Council serving as the deputy leader. The CLGCDR assumed the role of designing and implementing future reforms, urging lower-level government and party tiers to refine and carry out the decided measures. Local Comprehensively Deepening Reform Groups have been established at every administrative level down to the county level. Leading Groups are a government instrument dating back to the Ya’an period in the 1930s. They control and smoothen decision-making and policy implementation by coordinating and integrating the interests and opinions of government bureaucracies and Party branches (Tsai and Zhou Citation2019; Jiang Citation2023).

Following the 17th Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Congress held in late 2017, the Third Plenary Session of the 19th Central Committee initiated a new round of organizational restructuring at the central level in March 2018. As part of this restructuring, several ministries and commissions were abolished, and the Central Leading Group for Comprehensively Deepening Reform (CLGCDR) was elevated to the status of the ‘Central Commission for Comprehensively Deepening Reform’ (CCCDR or Zhongyang quanmian shenhua gaige weiyuanhui). Local CCCDRs were also replicated at each administrative tier down to the county level.Footnote10 Unlike the temporary nature of the previous Leading Groups, the ‘Commission’ is formally integrated into the Chinese political system. The CCCDR is a ministerial-level organization, which means it has more authority over Party, government and PLA bodies when it comes to national policy-making.

Compared to the NCRES and the NDRC, the authority of the CCCDR has been strengthened in three key areas. To begin with, the scope of the reforms launched by CCCDR ‘top-level design’ has been expanded. Since its enhancement, the CCCDR has spearheaded reforms across all policy fields. Officially, it sits under the CCP Central Committee, with lower-level CCCDRs answering to Party committees at corresponding administrative tiers. This is a notable shift from the previous Tigaiwei, which was subordinate to the State Council and primarily focused on economic reform. The CCCDR comprises six sub-groups, each dedicated to distinct policy areas: economic system and ecological civilization system reform, democracy and legal field reform, culture system reform, social system reform, party-building system reform, and disciplinary inspection system reform. The broadened scope signifies a heightened commitment to comprehensive reforms across various policy sectors under the CCP Central Committee’s leadership.

Secondly, the CCCDR’s organizational authority has been bolstered by the elevated ranks of its members, reflecting heightened leadership attention to the commission’s work.Footnote11 Prior to the 20th Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Congress held in October 2022, the Central Commission for Comprehensively Deepening Reform (CCCDR) consisted of 23 members. Among them, four held seats in the Standing Committee of the CCP Politburo, who are all national level cadres (zhengguoji): Xi Jinping, Li Keqiang, Wang Huning (Head of the CP Secretariat), and Han Zheng (First Vice Premier of the State Council). The remaining 19 members were leaders above the deputy national level (fuguoji).Footnote12 Each CCCDR sub-group is chaired by the head of a lead agency responsible for the respective policy field. For example, the sub-group for party-building system reform is headed by the director of the Central Organization Department (Zuzhibu), while the disciplinary inspection system reform sub-group is under the leadership of the secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (Zhongyang jilü jiancha weiyuanhui). In addition to the sub-groups, the CCCDR has a special office called the Shenggaiban, which is affiliated with the CCP Central Policy Research Office (Zhonggong zhongyang zhengce yanjiushi). The Central Policy Research Office is an important Party agency primarily concerned with ideological and theoretical work. One of the three deputy heads of the CCCDR, Wang Huning, serves as both the director of the Shenggaiban and the Central Policy Research Office,Footnote13 highlighting the strong connection between policy formulation, ‘ideological policing’ and ensuring strict oversight by the party leadership.

Finally, national policymaking is based on expanded cross-departmental deliberation and cooperation, utilizing the principles of ‘joint appointment’ (jiaocha renzhi) and ‘holding overlapping positions’ (shenjian shuzhi) to incorporate more policymakers in the agenda-setting process. These principles ensure that the CCCDR has influence and decision-making power across various levels of the political hierarchy. By establishing separate commissions for deepening reform at subordinate government levels, the CCCDR ensures the steady communication of the center’s reform agenda throughout the Party-state bureaucracy. Put differently, this institutional setup streamlines the reform discourse and continuously communicates the center’s attention to the importance of reform through the party state apparatus. By invoking the old proverb that ‘a little attention from the boss can resolve age-old problems in a stroke’ (laoda nan, lao da wenle jiu bu nan) it reflects the expectation of the party state leadership that higher-level attention and guidance can swiftly address long-standing issues.Footnote14

Tracing ‘hard steering’ by the CCCDR

Broadly, the CCCDR is entrusted with the task of formulating long-term reform strategies to overcome institutional fragmentation and reshape the distribution of bureaucratic interests, ultimately enhancing the overall effectiveness of policymaking. To fulfill this mandate, the CCCDR has, from its inception in 2014 through 2023, developed and ratified five significant reform implementation plans. Notably, on January 22, 2014, its predecessor, the CLGCDR, initiated the ‘Important Task-Distribution Plan for the Relevant Departments on Comprehensively Implementing the Central Decisions of the Third Plenary Session of the 18th CPC Central Committee’, outlining 336 different policy programs and measures. Subsequently, on August 18, 2014, the CLGCDR’s fourth meeting released the ‘Implementation Plan for the Important Reform Initiatives of the Third Plenary Session of the 18th CPC Central Committee (2014-2020)’, encapsulating Xi Jinping’s seven-year comprehensive reform agenda. This kind of five-year or even longer-term overall planning for reform differs from the ‘crossing the river by touching the stones’ approach, which was based on solving each problem as it arose.Footnote15

In addition to its extensive reform initiatives, the CCCDR is actively involved in designing and approving policies that address significant social concerns, which are the subject of widespread public debate and have garnered attention from top leaders. Among the 477 reform measures outlined, many are specifically targeted at addressing highly debated social issues. For instance, in response to the vaccine quality issues in Changchun on July 25, 2018, which raised serious public health concerns, the Standing Committee of the Central Political Bureau, led by Xi Jinping, convened a meeting on August 16 to address this issue. Subsequently, on September 20, during the 19th session of the CCCDR’s fourth meeting, the ‘Opinions on Reforming and Improving the Vaccine Management System’ were reviewed and approved, providing a response to these public concerns.

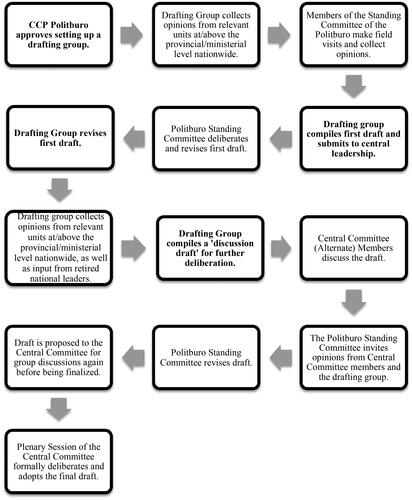

The formal process behind the formulation of the ‘Decision’, a pivotal reform-setting document from the Third Session of the 18th CPC Central Committee in the Xi Jinping era, is paradigmatic of CCDCR agenda-setting. This political show suggests an iterative and all-inclusive process designed to garner broad support across the party-state bureaucracy and various leadership groups, clearly employing the ‘thought unification’ methodology (tongyi sixiang) inherent in the Marxist tradition of policymaking. The process commenced in February 2013 when a drafting group of over 60 members, led by Xi Jinping, was formed. The early drafting stage involved consultations with more than 100 Party units, government departments, military organs, former leaders, ethnic minority representatives, the All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce, and selected non-Party members. Their inputs were further deliberated by the CCP Central Committee members, reviewed twice by the Politburo’s Standing Committee, and finally approved in the CCCDR plenary session. In addition to internal deliberations of central policy-making organs, there was extensive central–local interaction. In April 2013, the CPC Central Committee issued a notice to all provinces, autonomous regions, and centrally administered municipalities, as well as to central Party and state organs, the PLA, and various people’s organizations, soliciting their views on the new reform document. Within a month, 118 submissions and suggestions were collected. Concurrently, the Standing Committee of the CCP Politburo conducted field investigations across the country, leading to several additional rounds of comments on the draft ‘Decision’.

On July 25, 2013, the Committee decided to return the draft to the original drafting group for further review, resulting in a revised document for more consultation. This revised version was redistributed on September 4 to all involved parties. On September 17, Xi Jinping hosted a forum to hear the opinions of democratic party heads, the All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce, and non-Party members on the updated draft. This process yielded an additional 2,564 comments and suggestions. From November 9–12, the 204 Central Committee members and 169 alternate members attending the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee provided further feedback. Xi Jinping chaired this session, leading to another revision before the final approval by the Central Committee (see ). All five general reform implementation plans promulgated by the CCCDR since its establishment, eventually approved by the CPC Central Committee, have followed this cumbersome procedure.

Policy-formulation at central level is communicated through the CCP’s meticulous system of issuing documents. The CCCDR typically approves three types of documents. The first includes ‘regulations’ (guiding), ‘measures’ (banfa), ‘guidelines’(zhunze), ‘implementation rules’ (shishi xizhe), and ‘circulars’ (tongzhi), which provide detailed policy implementation guidelines. The second type is ‘opinions’ (yijian), offering general requirements and fundamental principles, allowing flexibility for local adaptation (yindi zhiyi). The third type, ‘plans’ (guihua), outlines future steps in reform planning and is comparatively less mandatory. Issuing documents through the Party-state system grants the CCCDR institutional authority, with varying levels of urgency for lower-level officials and governments. The highest authority is reflected in documents jointly issued by the General Office of the CPC Central Committee and the State Council’s General Office. Those from either body alone, or other ministries, carry less weight. Among the 477 CCCDR-approved documents analyzed, most were issued jointly by the Two Offices, while fewer, often addressing specific issues like household registration, came solely from the State Council’s General Office. Significant documents like the ‘Three-Year Action Plan for Rural Living Environment Improvement’ are typically joint issuances due to their broad impact and involvement of multiple ministries. We now turn to this reform program to assess the CCCDR’s impact on policy implementation and evaluation.

Policy implementation under CCCDR political steering – a case study

Case selection and description

We select the case study of the ‘Rural Living Environment Improvement Project (农村人居环境整治工程)’, which involved the joint participation of 18 ministries and commissions, requiring a great deal of coordination and considerable financial input. The reform began in 2017, after the Shengaiwei reviewed and approved the ‘Three-Year Action Plan for Improving Rural Living Conditions’, which was later inspected and evaluated in 2020. This was followed by the next round of reforms in 2021, implemented through the ‘Five-Year Action Plan on Rural Living Environment Improvement (2021–2025)’. As a typical case of hard steering, the empirical case contributes to a thorough interpretation of the policy process within the top-level design, showing a complete chain of policy formulation, implementation, monitoring and inspection.

In June 2003, Xi Jinping, then-Secretary of the Zhejiang Provincial Party Committee, initiated the ‘Zhejiang Green Rural Revival Program’, which aimed to enhance production (shengchan), living standards (shenghuo), and the ecological environment (shengtai) in rural areas. Around 10,000 villages (out of approximately 40,000) were selected for comprehensive improvement, with about 1,000 of them becoming designated demonstration villages for achieving a ‘moderately prosperous society in all respects’ (quanmian xiaokang shifancun). In Max 2013, ten years after the project began, Xi Jinping pushed for the Zhejiang experience to be promoted nationwide. The Central Leading Group for Rural Work took summarized Zhejiang’s experience and organized the National Conference on Improving Rural Living Environment, held in Tonglu, Zhejiang, on October 9. Premier Li Keqiang delivered a speech at the conference, emphasizing the need for systematic advancement in the comprehensive improvement of the rural living environment and the acceleration of beautiful village construction. During the Central Government’s Rural Work Conference in late 2013, the improvement of the rural living environment was once again emphasized as a major policy objective. Local governments started incorporating similar programs into their development agendas, and some regions established ‘rural living environment improvement offices’. However, at that time, essential supporting policies, such as financial assistance from the central authorities, were not significant, so each locality implemented its own policies independently. As a result, the implementation of rural development measures was sluggish at the local level, as local authorities had to contend with other policies deemed more important.

Agenda-setting and policy formulation

In October 2017, Xi Jinping emphasized in his report to the 19th National Congress that the reform of the ecological civilization system should prioritize addressing significant environmental issues and improving the rural living environment. A month later, on November 20, 2017, the first meeting of the 19th session of the CLGCDR approved the ‘Three-Year Action Plan for Rural Living Environment Improvement’ (Nongcun renju huanjin zhengzhi sannian xingdong fangan).Footnote16 Thus, it took over fourteen years for the Rural Living Environment Improvement Action Plan to be included in the CCCDR’s policy agenda, after its initial implementation in Zhejiang province. Two main factors contributed to this extended timeframe. First, the scope and urgency of the core problem addressed by the program were immense. Rural development and living standards faced significant challenges amidst rapid urbanization, leading to issues like ‘hollow villages’ and the ‘three left behind’.Footnote17 Obviously, these problems were too complicated to be resolved within a few years at local level alone. Second, there was no national policy initiative to guide and adequately fund comprehensive reform at the local level.

On January 2, 2018, the CCP Central Committee and the State Council jointly issued the ‘Opinions on Implementing the Rural Revitalisation Strategy’ in response to the widespread local indebtedness regarding rural infrastructure and people’s livelihood. These opinions aimed to address fiscal issues over a three-year period and ensure the creation of a livable, productive, and beautiful countryside. On January 23, 2018, the General Office of the CPC Central Committee and the General Office of the State Council jointly issued the ‘Three-Year Action Plan for Rural Living Environment Improvement’, formalizing the decision-making process of the CCCDR. This document emphasized the importance of learning from pioneering regions like Zhejiang and provided explicit requirements for policy implementation, evaluation, and performance assessment. It demonstrated strong guidance through ‘top-level design’. The plan established specific quantitative target indicators tailored to regions with varying levels of economic development, a task usually delegated to lower-level governments. These adjustments were made to ensure effective policy implementation at the grassroots level.

As a top-level designed policy, local differences have been taken into account. However, this has been done in a simplified fashion by only distinguishing between overall economic conditions. According to the plan, in areas with healthy economic conditions, such as the eastern region and the developed surroundings of central and western cities, the rural living environment needed comprehensive improvement. This included the establishment of a rural household waste disposal system, the introduction of private toilets with basic treatment of toilet waste, an increase of treated sewage water, visible beautification of villages, and the implementation of a long-term management and maintenance mechanism.Footnote18 For areas in the central and western regions with moderate levels of development, the focus was on comparatively improving the quality of the rural living environment. Targets included treating around 90 percent of household waste in villages, achieving an 85 percent installation rate of environmentally friendly toilets, controlling the indiscriminate discharge of household sewage water, and visibly improving village access to roads. In remote and economically underdeveloped areas, the emphasis was on meeting the basic conditions of a clean and tidy living environment.Footnote19

The central government required provinces, autonomous regions, and central-administered municipalities to develop their own implementation plans for rural living environment improvement by the end of March 2018. However, local governments also had to employ top-level design in implementing their rural blueprints and had to adhere to the national requirement of distinguishing between the economic conditions of the localities within their respective jurisdictions.Footnote20 These plans were to be submitted to the Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development, the Ministry of Environmental Protection, and the National Development and Reform Commission for central assessment and resource allocation. The provincial-level implementation plans needed to identify the specific sub-provincial jurisdictions where policy implementation should have top priority. They were also required to designate the responsible departments for implementation oversight, allocate funding, and outline the benchmarks and evaluation methods for the projects. Furthermore, the central government established procedures for each province to follow and urged them to initiate policy pilots, following the example of Zhejiang. Provinces were instructed to implement policies in selected demonstration sites, showcasing and refining local knowledge related to technology, operation, and environmental sustainability. The aim was to create replicable and scalable models that could be expanded to neighboring areas.

During the implementation period, relevant central departments were tasked with providing guidance to localities in the construction of demonstration villages for rural livelihood improvement, demonstration counties for rural waste separation and recycling, and model counties for sewage treatment. The central government maintained ongoing communication with provinces and lower levels of government to assess and gradually select the best practices, technical solutions, and management models suitable to be implemented nationwide. The entire implementation process thus demonstrated a ‘hard steering’ approach, as local discretion was monitored and kept within clearly defined boundaries.

Cross-departmental cooperation in task-assignment

In terms of the number of documents produced during the implementation process, there was substantial cross-departmental cooperation at the central level, with a focus on various implementation domains. On December 29, 2018, the Central Rural Work Office and the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, in collaboration with the National Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Science and Technology, the Ministry of Finance, and 18 additional ministries and commissions, jointly issued the ‘Rural Living Environment Improvement and Village Cleaning Action Plan’. They advocated for a ‘three clean-ups and one change (sanqing yigai)’ campaign throughout the entire year of 2019. This initiative aimed to address the cleanliness of rural areas by targeting household waste, village ponds and ditches, livestock farming manure, and other agricultural waste.

On October 21, 2019, the Central Office of Rural Works, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, and the Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development convened an on-site meeting in Lankao, Henan Province, to discuss the national rural household waste management system. Subsequently, the Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development issued the ‘Guiding Opinions on Establishing and Improving the Rural Household Waste Collection, Transfer, and Disposal System’. In parallel, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, in collaboration with eight other ministerial-level organs, released the ‘Guiding Opinions on Promoting the Treatment of Rural Domestic Sewage’. This effort also encompassed the inclusion of agricultural and rural pollution control within the central environmental protection inspection mechanism. Furthermore, the Ministry issued the ‘Guiding Opinions on Promoting the Control of Black and Malodorous Water in Rural Areas’, supplemented by the ‘Guidelines for the Compilation of Water Pollutant Discharge Control Standards for Rural Household Sewage Treatment Facilities (Trial Implementation)’.

The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural affairs has also addressed the recycling of rural resources and the re-cultivation of agricultural land. In collaboration with relevant departments it has issued three notices: The ‘Notice on Doing a Good Job in the Implementation of the 2019 Livestock and Poultry Manure Recycling Project’, the ‘Guiding Opinions on Promoting the Return of Livestock and Poultry Manure to the Field and Strengthening the Governance of Breeding Pollution (yangzhi wuran zhili) according to the Law’, and the ‘Notice on Further Doing a Good Job in the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Management of Current Large-Scale Pig Breeding’. Finally, in promoting village planning, five departments, including the Central Office of Rural Works (Zhongyang nongban), the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, the Ministry of Natural Resources, the National Development and Reform Commission, and the Ministry of Finance, advocated for integrated-planning (duogui heyi, 多规合一) and issued the ‘Opinions on Coordinating the Promotion of Village Planning Work’.

The enumeration of these documents may seem mundane, but they highlight significant characteristics of the ‘hard steering mode’. With policymaking entrusted to the CCCDR, which holds supreme authority, every government organ is mandated and mobilized to participate. To illustrate this point, we can examine the policies implemented by the Ministry of Agriculture. Typically, major policies enacted by ministerial-level organs are communicated through the State Council Bulletin (Guowuyuan Gongbao). Before the establishment of the CCCDR in 2014, spanning the years 2003 to 2013, a total of 117 policies enacted by the Ministry of Agriculture were issued via the State Council Bulletin. Among these, 39 were jointly formulated, usually involving three to four ministries, often in collaboration with the National Development and Reform Commission and the Ministry of Finance. Subsequently, after the establishment of the CCCDR, covering the period from 2014 to 2023, a total of 158 documents enacted by the Ministry of Agriculture (later known as the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs) were recorded. Out of these, 73 were jointly enacted, typically involving eight to nine ministries.

‘Firearm shooting’ in policy-implementation

As mentioned above, the ‘Three-Year Action Plan for Rural Living Environment Improvement’ was reviewed and approved by the CLGCDR on November 20, 2017, but not immediately released by the Two Offices. However, only two weeks later, on December 5, the Jilin Provincial Leading Group Office of Rural Living Environment Improvement started to encourage municipal and county governments to submit their own implementation plansFootnote21 – a typical example of policy implementation by sudden ‘firearm shooting’ (qiangpaoshi zhixing/抢跑式执行), which is very common in TLD-steered policy implementation, as local governments aim to win sympathy or praise from their superiors by taking prompt action or adding policy requirements to their development blueprints.Footnote22 During the drafting process of its Action Plan, the Jilin provincial government first held a forum to listen to grassroots opinions, sent cadres to cities, counties, towns, and farmers to carry out field research, sent more officials to other provinces on inspection tours to study local policy implementation, contacted the National Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development several times, and solicited 23 comments and suggestions from 20 provincial departments and nine municipal governments. Obviously, the process mimicked the policy-formulation process of the ‘Decision’ described above. On March 29, Jilin’s governor convened a special meeting to discuss the Action Plan, which was submitted to the provincial Party secretary for approval and then reported to the National Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development, the National Ministry of Environmental Protection, and the National Development and Reform Commission on March 30. They agreed in principle to Jilin’s design but also proposed starting from practical experience (shiji chufa), making local adjustments (yindi zhiyi), classifying guidance (fenlei zhidao), giving priority to tackling the rural sewage and waste problem and toilet renovation in ecologically sensitive areas, and focusing on pilot implementation and work in selected pilot sites (shidian). Following the recommendations from the central government, Jilin province revised the Action Plan. On April 26, 2018, representatives from the provincial government attended the National Conference on Improving the Rural Living Environment held in Anji County, Zhejiang Province.Footnote23 Some of the requirements for proper implementation of the National Action Plan discussed at this meeting were then incorporated into the provincial counterpart, resulting in a final draft version ready for review. On May 11, the Standing Committee of the Provincial Party Committee reviewed and adopted the Action Plan, which was officially issued by the General Office of the Provincial Party Committee and the General Office of the Provincial Government on May 16, 2018.

Sticks and carrots in policy supervisions and evaluation

Policy supervision and evaluation under ‘top-level design’ are achieved through rigorous oversight and substantial financial support, employing both sticks and carrots. The process involves three supervisors and three inspectors (sandu sancha/三度三差) for supervision and performance evaluation. This means that the supervision process not only monitors the tasks, progress, and effectiveness of a policy but also inspects the awareness, responsibility, and work style of those implementing it.Footnote24 The institutional framework for supervision is divided into several levels: the CCCDR integrates the entire system, while its subordinate special groups coordinate program supervision. The leading government departments within these special groups are responsible for overseeing policy implementation at the local level. The supervision reports submitted by the different sub-groups are a major focus of discussion during the annual work meetings of the CCCDR. During the implementation of the ‘Three-Year Action Plan on Rural Living Environment Improvement’, two rounds of large-scale inspections were organized by the responsible CCCDR special group on Economic System and Ecological Civilization System, along with the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. Additionally, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs had the authority to assess the local implementation process at any time. This arrangement should secure a timely identification of problems, as performance evaluations were conducted midway through project implementation. The results of these evaluations were linked to project funding for the following year.

In the CCCDR’s ‘hard steering’ of policy implementation, the resources and financial incentives provided by the center are explicitly defined. In 2019, for example, central budget expenditures for the National Action Plan focused on three support policies. The first policy provided subsidies and rewards for launching the ‘rural toilet revolution’ (nongcun cesuo geming), with funds of seven billion RMB allocated by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs and the Ministry of Finance. The second policy, in response to the relatively backward situation in the central and western regions, was initiated by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, together with the National Development and Reform Commission, and allocated three billion RMB of special funds for the ‘County Renovation Promotion Project for Rural Living Environment Improvement’. This policy targeted 141 counties nationwide, selected by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. Each county received financial support of more than 20 million RMB to invest in the comprehensive improvement of rural household sewage, household waste, toilet and manure treatment, and the beautification of villages (cunrong cunmao). The third policy was directed at supervising incentive assessment. According to the ‘Notice of the General Office of the State Council on Further Strengthening Incentive Support for Local Governments Visibly Getting Things Done’, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs and the Ministry of Finance, based on local recommendations, selected 19 counties that had achieved remarkable results in the prior improvement of the rural living environment and awarded each of them 20 million RMB. Apart from these three newly launched policies, the existing support measures from other sources remained unchanged, such as those for rural sewage treatment, livestock and poultry manure treatment, and toilet construction in tourist locations.

The State Council organized a major inspection round. From November 26 to December 4, 2019, 14 teams were dispatched to 14 provinces and municipalities to conduct field inspections. These inspections took place in the middle of project implementation. In November 2020, various departments, including the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, the National Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, the Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development, the Health and Wellness Commission, and the National Federation of Supply and Marketing Cooperatives, sent their own officials to assess implementation and assess the visible results. The assessment was smooth and found that all the policy objectives of the Three-Year Action Plan had been completed as scheduled, indicating satisfactory implementation effectiveness. According to official sources, by the end of 2020, the penetration rate of sanitary toilets in rural areas across the country had surpassed 68 percent. The proportion of natural villages where household waste was collected and treated stood at over 90 percent, and the rate of rural household sewage treatment had reached 25.5 percent. Furthermore, more than 95 percent of villages nationwide had carried out clean-up actions. All towns and villages considered suitable for project implementation got access to paved roads and passenger buses, and over 50,000 beautiful and livable (yiju) villages were built in various regions.Footnote25

Critical assessment

As always, the official reports painted an overly beautiful picture. The implementation of the Action Plan in this case study is a typical example of ‘hard steering’ in Xi Jinping’'s China, where local governments have limited discretion to implement policies according to local conditions. Decision-making, resource allocation, goal setting, and implementation scheduling are all determined from the top down with strict quantitative assessment and supervision. Unfortunately, this approach has resulted in several negative consequences.

Firstly, in their rush to meet deadlines, local governments have cut corners, leading to poor quality of projects. Secondly, insufficient research into farmers’ needs and the local reality has resulted in project-related constructions that are either ‘built but not used’ (jian er bu yong) or that farmers ‘want to use but are unable to’ (xiang yong bu neng yong).Footnote26 For instance, media reports have highlighted that out of the more than 80,000 toilets built in the northern city of Shenyang, 50,000 have been abandoned, wasting over 100 million RMB of public funds.Footnote27 Some of these toilets were constructed without considering the harsh northern climate, rendering them unusable as outdoor temperatures drop below −20 degrees Celsius during winter. Others were converted into indoor toilets placed opposite stoves, making regular cleaning difficult due to a lack of pump water supply. Some toilets were even relocated to abandoned yards by local officials solely to meet ‘toilet installation by household’ targets. In some cases, households were equipped with three toilets to fulfill numerical targets, resulting in unnecessary duplication. Issues such as how to construct sanitary toilets, determining the appropriate capacity to serve the population, allocation of funds, provision of supporting facilities, and addressing post-maintenance demands all require a significant degree of local policy initiative and adjustment. However, under the conditions of ‘hard steering’, which limits local discretion, these adjustments seem to be difficult to make.

Despite the central government’s call for local adaptation, lower-level governments are still subjected to quantitative target evaluation, which adds pressure and strict timelines. As a result, local cadres often lack sufficient time to investigate implementation problems or find effective solutions. Consequently, they resort to a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach, leading to inefficiency in accomplishing their assigned tasks. Balancing effective and efficient policy implementation (Ahlers and Schubert Citation2015), which necessitates local flexibility, with the hard steering mode of ‘top-level design’, presents a major challenge in contemporary Chinese governance. In fact, it may result in more implementation problems compared to the previous system that allowed for greater local discretion.

At the end of 2021, a new ‘Five-Year Action Plan for Rural Living Environment Improvement (2021–2025)’ was announced. This plan introduces several notable enhancements compared to its predecessor, the Three-Year Action Plan. Firstly, the policy objective has been elevated from the pursuit of ‘clean and orderly villages’ to the aspiration for ‘aesthetically appealing and cherished villages’. This upgrade is accompanied by more specific goals related to the installation of sanitary toilets, household sewage and waste treatment systems, and village beautification efforts. Secondly, recognizing the previous lack of farmer participation in the implementation of the Three-Year Action Plan, the Five-Year Action Plan emphasizes the crucial role of farmers in executing the policies. It encourages local governments to respect farmers’ preferences, harness their enthusiasm, and stimulate their intrinsic motivation to improve their living conditions. However, the fundamental issue of reconciling the rigid top-down directives with the need for adaptable local adaptation remains unresolved. The failure to address this core contradiction in policy implementation raises concerns about the long-term viability and sustainability of the new Action Plan.

Conclusion

This article examines the Chinese policy process in the contemporary era of ‘top-level design’, as guided by the Central Commission of Comprehensively Deepening Reform (CCCDR), which was established in 2013 and further institutionalized in 2018. Our tracing of a specific policy aimed at improving rural living conditions sheds light on the ‘hard steering’ approach by the principal TLD institution in the current regime. The study traces the stages of agenda-setting, formulation, implementation, and evaluation in national policymaking under the direction of the CCCDR, as well as the responses of local governments. The issuance of documents serves as the most visible form of policy guidance from the CCCDR, revealing the enduring nature of protracted policymaking, even within a recentralized policy process under ‘top-level design’. Assessing the effectiveness of cross-departmental vertical and horizontal policy coordination and the overall state of the CCP’s governing capacity over the past decade is challenging for China scholars. Access to policymakers has become particularly difficult, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the limitations in our findings under current circumstances, this article still sheds light on significant issues related to the contemporary top-level design of major party-state policies. Despite the significant pressure on lower-level governments and party committees to implement upper-level policy guidelines, including specific prescriptions, empirical scrutiny suggests that implementation on the ground, as demonstrated by the example of the ‘Three Year Action Plan of Rural Living Environment Improvement’, has been far from satisfactory.

It is crucial to underline that our primary focus is on reporting a formal process, and we are refraining from making immediate judgments regarding the extent to which it reflects reality. However, what does seem apparent from the empirical reality is that the implementation outcomes present a facade of success based on predetermined standardized evaluation indicators. Other critical dimensions, including costs, sustainability, and regional variations, are evidently overlooked. Despite the increased formal rigor of supervision and evaluation in the Xi Jinping era, local governments still appear to have considerable leeway to evade top-down ‘hard steering’, as evidenced by the gap between actual and reported policy implementation on the ground. Our study therefore suggests that ‘top-level design’, in conjunction with the anti-corruption campaign, has partially addressed entrenched interests impeding institutional reform across the country; its effectiveness in meeting top-level targets is evident; its efficiency in ensuring comprehensive and cost-effective policy implementation is not.Footnote28

The limitations of ‘hard steering’ in a vast country like China are obvious. The CCCDR is cracking the hard bones left by the bottom-up reform approaches of the past. On the other hand, when top-down design becomes mainstream, it is difficult to avoid the situation in which it becomes normal to wait for superiors to make a decision rather than finding one’s own solutions. Reducing the flexibility of lower-level governments to tailor national policies to local circumstances risks incurring high opportunity costs, which may outweigh the benefits of increased top-down control.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

X. C. Chen

X. C. Chen is a PhD candidate at the Department of Chinese Studies at Tübingen University. She specializes in local governance and cadre evaluation in the PRC.

Gunter Schubert

Gunter Schubert is Chair Professor of Greater China Studies at the Department of Chinese Studies at Tübingen University. His research focuses on local governance and policy implementation in China’s local state, state-business relations and private sector reform in contemporary China, and the cross-strait political economy.

Notes

1 In 2010, the importance of ‘top-level design’ for conducting overall planning (zongti guihua) in the context of reform was emphasized by the 5th Plenum of the 17th CCP Central Committee. This emphasis was reiterated in the 12th Five-Year Plan. Furthermore, the National Economic Work Conference held on December 10, 2010, confirmed the need for strengthening overall reform design. For more information, see ‘Zhongyang jingji gongzuo huiyi gongbao 2010/2010 年中央经济工作会议公报’ (Communiqué of the 2010 Central Economic Work Conference). Accessed June 23, 2023. http://www.china-cer.com.cn/zhongdian/2021090914627.html

2 See ‘Jinti bumen lifa beihou de liyi kuozhang xianxiang/警惕部门立法背后的利益扩张现象’ (Beware of the expansion of interests behind departmental legislation)’. Accessed November 29, 2023. http://www.gov.cn/ztzl/2006-03/12/content_225372.htm

3 This reform was adopted by the CCCDR in 2017, evaluated in 2020 and then upgraded to the ‘Five-Year Action Plan on Rural Living Environment Improvement’ (Nongcun renju huanjing zhengzhi tisheng wunian xingdong fangan/农村人居环境整治提升五年行动方案) (2021-2025).

4 Between June 2020 and March 2022, we conducted interviews in Anhui, Henan and Fujian provinces with five different groups of respondents: villagers, village cadres, township cadres, county cadres and policy advisors in research institutions. To protect our interlocutors, we do not mention their names or affiliations.

5 While ‘hard steering’ is characterized by authority and hierarchy, ‘negotiation’ relies on non-hierarchical approaches and mutual agreement through consensus-building. ‘Competition’ involves policymaking through non-hierarchical, market-based decision-making processes. ‘Soft steering’ refers to semi-hierarchical, discursive steering primarily achieved through the ideological framing of policies. Each steering mode employs specific steering instruments (e.g., fiscal transfers and subsidies, cadre and performance evaluation mechanisms, policy experimentation, anti-corruption campaigns) and steering tactics (e.g., building policy networks or advocacy coalitions, cooperating with social actors) to guide policy implementation and evaluation (Schubert and Alpermann Citation2019, 213).

6 Unfortunately, at this point of our research we cannot say too much about the responses of local governments to ‘hard-steering’, particularly regarding specific coping, shirking or counter-steering strategies. However, political steering theory does not necessarily require a full-fledged analysis assessing both the state’s steering capacity and governability.

7 ‘Chongshe Tigaiwei/重设体改委’ (Reestablish the Tigaiwei), China Youth Daily, 8 March, 2012. Accessed November 29, 2023. http://zqb.cyol.com/html/2012-03/08/nw.D110000zgqnb_20120308_4-01.htm

8 ‘Notice from the General Office of the State Council on the Issuance of Regulations on the Organizational Structure and Staffing of the Office of Economic System Reform of the State Council [1998 (34)]’ (国务院办公厅关于印发国务院经济体制改革办公室职能配置内设机构和人员编制规定的通知国办发〔1998〕34号). Accessed November 29, 2023. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2010-11/17/content_7844.htm

9 ‘Pandian shisanci shengaizu huiyi kenxia naxie yinggutou 盘点十三次深改组会议啃下哪些硬骨头’ (Track the Hard Bones Cracked by Thirteen Shengaizu Meetings), Beijing Youth Daily. 8 June 2015. Accessed November 29, 2023. http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2015/0608/c1001-27116868.html

10 ‘Decision of the CPC Central Committee on deepening the reform of the Party and state institutions’ (中共中央关于深化党和国家机构改革的决定). Accessed November 30, 2023. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2018-03/04/content_5270704.htm. Other DRCs were set up in central ministries and commissions, special economic zones, state-owned enterprises and even the military. An estimated 800 DRCs had been established across the country in mid-2014 (Naughton Citation2014).

11 See Chen et al. (Citation2019) and Pang (Citation2019) on the importance of leadership attention in China’s bureaucratic apparatus.

12 After the 20th Party Congress, the new heads of the CCCDR are Xi Jinping, Li Qiang (Premier of the State Council, Wang Huning (Chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference) and Cai Qi (First Vice Premier of the State Council).

13 Wang Huning’s term as director of the Central Policy Research Office ended in October 2020, but he is still in charge of this office as a member of the Standing Committee of the CCP Politburo.

14 Interview, Oct. 2021. One of our reviewers rightfully expressed doubts about the effectiveness of holding more meetings for policy finetuning to improve policy implementation. However, in our experience, increased formal deliberation requirements are not futile in promoting serious deliberation. In practice, cross-departmental deliberation under the supervision of a higher-ranked cadre indicates higher priority in the working-agenda. Besides, such arrangements provide platforms for political actors to integrate their departmental interests or wider policy objectives, often resulting in policy blueprints that carry more authority as they make their way down the administrative hierarchy.

15 The PRC’s five-year plan for national economic and social development focuses on economic reform and follows the line of the National Development and Reform Commission.

16 ‘Xi Jinping: Quanmian guanqie dang de shijiuda jingshen jianding buyi chiang gaige tuixiang shenru/习近平: 全面贯彻党的十九大精神 坚定不移将改革推向深入’ (Xi Jinping: Fully implement the spirit of the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China and unwaveringly push reforms to a deeper level), Xinhua News, 20 November 2017. Accessed November 29, 2023. https://news.12371.cn/2017/11/20/ARTI1511182315185837.shtml

17 ‘Hollow villages’ describe rural areas devoid of male labor, where capital has migrated to cities, leaving behind empty houses and unused infrastructure, accompanied by a lack of funding and desolate productivity. The term ‘three left behind’ refers to children, women, and elderly individuals left behind when others migrate to urban areas for work.

18 This mechanism basically refers to linking financial subsidies by the local authorities to contributions by the village collective and individual villagers according to the principle that those who benefit pay a share.

19 ‘Nongcun renju huanjing zhengzhi sannian xingdong fanga/农村人居环境整治三年行动方案’ (Three-Year Action Plan for Rural Living Environment Improvement), issued by the General Office of the CPC Central Committee in the January of 2018 (Document No. 5).

20 To ensure effective implementation, the CPC Office on Agricultural Affairs and the Ministry of Rural Affairs, as the relevant Party-state departments, provided implementation guidelines. They mandated provinces to categorize the counties within their jurisdictions based on their economic conditions and location when setting targets in their respective three-year action plans. Category I counties enjoyed good economic conditions and were typically located in eastern cities and the suburbs of central and western cities. Category II counties were moderately developed and located in central and western China. Category III counties were economically less developed and mostly situated in remote areas.

21 Jilin Provincial Leading Group Office of Rural Living Environment Improvement, letter regarding the Key Work Plan for Improving Rural Living Environment Application (关于申报改善农村人居环境重点工作计划的函), 2017 (Document No. 28).

22 Interviews, June 2020.

23 The National Conference on Rural Living Environment Improvement (全国改善农村人居环境工作会议) was held twice by the State Council in 2013 and 2018.

24 ‘Zhongyang quanmian shenhua gaige lingdao xiaozu di ershiliu ci huiyi zhaokai/中央全面深化改革领导小组第二十六次会议召开 (Opening of the 26th Work Meeting of the CCCDR)’, 22 July 2016. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-07/22/content_5093982.htm

25 ‘Nongchun renju huanjing xiang zhengti tisheng wanjin/农村人居环境向整体提升迈进’ (Rural living environment takes a step towards overall improvement), Economic Daily. 8 December 2021. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-12/08/content_5659221.htm

26 Interview, January 2022.

27 ‘Shenyang wuwan qiren gace kanchen xingshizhuyi biaoben’/沈阳五万气人”尬厕” 堪称形式主义”标本” (Shenyang’s 50,000 angry “embarrassing toilets” can be called formalism ‘specimens’), Xinhua Daily Telegraph, 28 January 2021. Accessed November 30, 2023. http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2021-01/28/c_1127034481.htm

28 See Ahlers and Schubert (Citation2015) on the conceptual difference between effective and efficient policy implementation.

References

- Ahlers, Anna L., and Gunter Schubert. “Effective Policy Implementation in China’s Local State.” Modern China 41, no. 4 (2015): 372–405. doi:10.1177/0097700413519563.

- Ahlers, Anna L., and Gunter Schubert. “Nothing New Under ‘Top-Level Design’. A Review of the Conceptual Literature on Local Policymaking in China.” Issues & Studies 58, no. 01 (2022): 34. pages. doi:10.1142/S101325112150017X.

- Baranovitch, Nimrod. “A Strong Leader for a Time of Crisis: Xi Jinping’s Strongman Politics as A Collective Respone to Regime Weakness.” Journal of Contemporary China 30, no. 128 (2021): 249–265. doi:10.1080/10670564.2020.1790901.

- Chen, Sicheng, Tom Christensen, and Liang Ma. “Competing for Father’s Love? The Politics of Central Government Agency Termination in China.” Governance 32, no. 4 (2019): 761–777. doi:10.1111/gove.12405.

- Chen, Xuelian. “A U-Turn or Just Pendulum Swing? Tides of Bottom-Up and Top-Down Reforms in Contemporary China.” Journal of Chinese Political Science 22, no. 4 (2017): 651–673. doi:10.1007/s11366-017-9515-6.

- Deng, Xiaoping. “Maintaining Moderate Development of Production in the Reform Process (Zai gaige zhong baochi shengcan de jiaohao fazhan).” In Deng Xiaoping Selected Works (Deng Xiaoping Wenxuan), Vol. 3, 268. Beijing: Renmin, 1988.

- Gao, Kuo. Industrial and Commercial Productions Quality Inspection was Re-decentralized to Local-level. Gongshang zhijian chongxin xiafang defang guanli), Qilu Evening News (Qilu Wanbao), 15 October 2013, 2013.

- Guo, Baogang. “A Partocracy with Chinese Characteristics: Governance System Reform under Xi Jinping.” Journal of Contemporary China 29, no. 126 (2020): 809–823. doi:10.1080/10670564.2020.1744374.

- Heffer, Abbey S., and Gunter Schubert. “Policy Experimentation under Pressure in Contemporary China.” The China Quarterly 253 (2023): 35–56. doi:10.1017/S0305741022001801.

- Heilmann, Sebastian. Red Swan. How Unorthodox Policy Making Facilitated China’s Rise, Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2018.

- Heilmann, Sebastian, and Oliver Melton. “The Reinvention of Development Planning in China, 1993-2012.” Modern China 39, no. 6 (2013): 580–628. doi:10.1177/0097700413497551.

- Jiang, Jiying. “Leading Small Groups, Agency Coordination, and Policy Making in China.” The China Journal 89 (2023): 95–120. doi:10.1086/722600.

- Li, Linda Chelan. “Central-Local Relations in the People’s Republic of China: trends, Processes and Impacts for Policy Implementation, Journal of.” Public Administration and Development 30, no. 3 (2010): 177–190. doi:10.1002/pad.573.

- Li, Song. “Blowing the Cold Wind of Vertical Management (Cuixiang Chuizhi Guanli de Lengfeng).” Journal Liaowang (Liaowang), no. 27 (2009): 10–12.

- Lieberthal, Kenneth G., and Michel Oksenberg. Policy-Making in China: Leaders, Structures, and Processes. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988.

- Naughton, Barry. “Deepening Reform’: The Organization and the Emerging Strategy.” China Leadership Monitor, no. 44 (2014): 1–14.

- Oi, Jean C. “Future of Central-Local Relations.” In Fateful Decisions: Choices That Will Shape China’s Future, edited by Thomas Finger, and Jean C. Oi, 107–120. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2020.

- Pang, Mingli. “领导高度重视: 一种科层运作的注意力分配方式 (Leaders Attach Great Attention: an Attention Distribution Approach of Hierarchical Operation).” Chinese Public Administration (中国行政管理) 4 (2019): 93–99.

- Schubert, Gunter, and Björn Alpermann. “Studying the Chinese Policy Process in the Era of ‘Top-Level Design’: The Contribution of ‘Political Steering’ Theory.” Journal of Chinese Political Science 24, no. 2 (2019): 199–224. doi:10.1007/s11366-018-09594-8.

- Teets, Jessica C., and Reza Hasmath. “The Evolution of Policy Experimentation in China.” Journal of Asian Public Policy 13, no. 1 (2020): 49–59. doi:10.1080/17516234.2020.1711491.

- Tsai, Wen-hsuan, and Wang Zhou. “Integrated Fragmentation and the Role of Leading Small Groups in Chinese Politics.” The China Journal 82 (2019): 1–22. doi:10.1086/700670.

- Xi, Jinping. “Reform and Opening-up Do Not Stop (Gaige butingdun, kaifang buzhibu).” In Discourse on Persisting in Comprehensively Deepening Reform (Lun jianchi quanmian shenhua gaige), 2. Beijing: Zhongyang Wenxian, 2018a.

- Xi, Jinping. “Deepening Reform and Opening-up is the Only Way to Uphold and Develop Socialism with Chinese Characteristics (Shenhua gaige kaifang shi jianchi he fazhan zhongguo tese sehuizhuyi de biyou zhilu).” In Discourse on Persisting in Comprehensively Deepening Reform (Lun jianchi quanmian shenhua gaige), 4. Beijing: Zhongyang Wenxian, 2018b.

- Xi, Jinping. “Reforms Do Not Stop, Opening-up Does Not Stop (Gaige bu tingdun, kaifang bu zhibu).” In On Persisting in Comprehensively Deepening Reform (Lun jianchi quanmian shenhua gaige), 1. Beijing: Zhongyan Wenxian, 2018c.

- Zhao, Shukai. “The Crisis and Change of Governance on County and Township Government, Structural Adjustment of Power Distribution and Interaction Mode (Xianxiang zhengfu zhili de weiji yu biange, shiquan fenpei yu hudong moshi de jiegouxing tianzheng).” Journal of People’s Forum (renmin luntan) 21 (2013): 14–30.

- Zhou, Zhencao, and Anzeng Li. “Analysis on Dual Leadership in Government Management (Zhengfu guanli zhong de shuangchong lingdao yanjiu).” Dongyue Luncong, 30, no. 3 (2009): 134–138