ABSTRACT

Given that Fauvist, Futurist, Rhythmist and Vorticist painting and sculpture took dance and the dancer as an endlessly inspirational point of departure in their exploration of what Clive Bell termed “significant form,” Modernist scholarship has remained neglectful of the mutual borrowings of this synaesthetic relationship. “Above all let us dance and devise dances” wrote Bell, enthused by Henri Bergson’s espousal of rhythmic sequence and gesture in dance to illustrate his philosophy of time, durée and individual consciousness. Modern dance for Bell was on a par with primitive art, “the highest art form” because it too “dispenses with attempts to be representational” (Art 1914). In London’s avant-garde reordering of aesthetic merit, Asia no longer stood for stasis, but the static perfection of the transcendental. While Jacob Epstein’s scandalous assault on London’s architecture at one end of the Strand continued to reverberate, his iconoclastic abandonment of the Greek in favor of East Asian forms found its aesthetic counterpart in Margaret Morris’s ballet Angkorr at the Coliseum Theatre some blocks away. This paper aims to situate Morris within these Bergsonian influenced movements and to position British Modernist dance as a core element of their innovations.

“Angkorr” Margaret Morris’s strangely named dance,

At the Colly has made a furore

No wonder all Tommies on furlough from France,

When the curtain falls, call out “Ang-korr”

(The Era 24 January, 1917, 13)

“The pioneer works of Margaret Morris were presented perhaps before their time for when her ballet Angkorr, inspired by Indian and Cambodian sculpture, was presented at the London Coliseum it was firmly rejected by an audience unused to dancers performing to percussion only and in strangely colourful costumes of cubist design. Yet all who found their way to her studio realized the value of her work.”Footnote1

To put Stoll’s latest offering into some context, another soldiers’ favorite was Chu Chin Chow: A Musical Tale of the East at His Majesty’s Theatre, Haymarket. Just as appealing as the contemporaneity of Vesta Tilley’s “Tommy” was the fabled Orient of Chu Chin Chow. The show had opened the previous summer and would run throughout the war years and beyond.Footnote4 The principal attraction of Chu Chin Chow was its chorus of scantily clad harem girls and it is likely Stoll had this in mind when he booked Angkorr for the Coliseum. Its title’s suggestion of the Far East with its three acts, “The Flower Priestesses,” “The Petals,” and “The Harem Dancers,” promised a similar display of feminine attractions so who could anticipate that Angkorr would be pulled from the program after just one performance?

It was characteristic of Stoll’s hands-on management that he might adjust the content of a program “right up to the very last moment … and the song or business which seemed not to please the audience … would be cut the following week.”Footnote5 Reflecting upon her ballet’s failure to please in an interview with the Dancing Times Morris commented:

You must remember I am not endeavouring to cater for the general public. I was very surprised when the Coliseum booked my ballet ‘Angkorr’ which I was at the time rehearsing for my own theatre. But having booked it, I was sorry they withdrew it after the first performance, as it went much better than I expected, and quite a number of people would have enjoyed it. (May 1917, 248)

In a statement published in the News of the World to coincide with Angkorr’s opening at the Coliseum, Morris had anticipated that her newest work might be challenging: “I do not want the ballet to be called futuristic, for although the colours are particularly bright and scheme and execution are new, I won’t have it labelled with what has now become a meaningless catchword” (January 21, 1917). It would not be the first time a Coliseum audience had been confronted with something startlingly new. In June 1914, F. T. Marinetti’s “Grand Futurist Concert of Noises” had provoked boos and catcalls and was widely derided in gleefully xenophobic terms.Footnote7 Since then the term “futurist” had come to be bandied about by the press to label anything it did not understand. While most of them did in fact resort to “futurist” in their attempts to describe Angkorr, reviewers were more forgiving of Morris than they had been of Marinetti and his Italians:

“Futurist Performances at Chelsea” – We are afraid it will be a long time before Miss Margaret Morris is able to persuade an audience like that of the Coliseum to appreciate her new ballet Angkorr … In a small intimate playhouse, like her own little theatre at Chelsea, her methods of producing ballet are admirable; in a vast house like the Coliseum they are out of place. Possibly the impatience of the audience yesterday was partly due to the fact that the ballet immediately preceded Miss Vesta Tilley, and the patrons of the Coliseum have taken to their hearts her inimitable little character sketch of the mud-stained soldier arriving at Victoria on six days’ leave. (The Times, January 23, 1917)

much indeed to praise in the performance yesterday of Margaret Morris and her little troupe of “futurist” dancers at her own little theatre in Chelsea. … On a big stage before a big popular audience, where there is sure to be a laugh from the gallery at anything out of the common, Miss Margaret Morris and her friends did not, and could not, show anything like their true value. (February 22, 1917)

Angkorr may have flopped at the Coliseum, after all as Marinetti had exulted: “the Variety Theatre destroys the Solemn, the Sacred, the Serious and the Sublime in Art with a capital A,” but it continued to be performed before the more partisan audiences who made their way to the Margaret Morris Theatre in Chelsea.Footnote8

“A Chelsea personality” (The Sketch December 17, 1919)

Morris would claim the distinction of having founded the first of London’s so-called “little theatres.”Footnote9 In June 1914 her plan was announced in the mass circulation paper T. P.’s Weekly: “With the courage of youth Miss Margaret Morris most brilliant of young dancers, is opening a theatre under license from the Lord Chamberlain.”Footnote10 Six months previously, thanks to its growing success, Morris had moved her dance school from its one-room beginnings in the West End to a space “100 feet long” above a temperance billiard hall in the Kings Road, Chelsea, where she installed raised seating at one end while the other, screened off by a hand-painted curtain, did duty as stage or classroom as required.Footnote11 From 1915 these premises would serve also as the venue for the Margaret Morris Club, inaugurated to alleviate the gloom of wartime London with the ambience of Montparnasse, where “free discussion” was to be encouraged and a platform provided for “original creative work in the arts.”Footnote12 A stated “Object Of The Club” was that such work should “be what the artist really wants to do; without any consideration for the feelings of the audience,” there to be “no compromise for the sake of pecuniary gain and popularity.”Footnote13 Musical events, lectures, and buffet suppers with social dancing to gramophone records were regularly attended by figures now firmly established in the Modernist canon, among them Jacob Epstein, Ezra Pound, Wyndham Lewis, the Sitwells, Katherine Mansfield, Constant Lambert, Gordon Craig, Charles Rennie Mackintosh; it would be simpler to list those who didn’t attend than those who did – indeed Bloomsbury might cover it.Footnote14

Yet despite these pioneering credentials Morris generally gets dismissed by dance critics as a minor figure in the British wake of Isadora Duncan’s Hellenic school. Her wide-ranging creative endeavors have been overlooked and her pedagogic achievements sidelined by scholars of modernism.Footnote15 While Matthew Hofer for example, has drawn attention to the “decidedly radical” project of non-institutional education aiming at “interdisciplinarity through the interaction of the arts” as an assertion of the collaborative spirit of London’s pre-war avant-gardes, this is something invariably observed within the purview of Wyndham Lewis and Ezra Pound.Footnote16 It is true that Pound hoped to open a College of Arts which would foster dialogue between “sculpture, painting, music, letters, photography, crafts, and dance” and that Lewis planned to offer “instruction in various forms of applied Art” at his Rebel Art Centre founded with Kate Lechmere in Great Ormond Street.Footnote17 However the Rebel Art Centre, as Lewis was to admit, advertised “lectures that were never delivered, and classes that were never held,” while Pound’s College of Arts, which he advertised in The Egoist in November 1914, never materialized.Footnote18 Meanwhile such Modernist urges towards an integrated aesthetic education, generally accepted as “Lewisian and Poundian ideals,” were ideals that Morris had already succeeded in putting into practice.Footnote19

It is not immaterial that both Pound and Lewis were regular attendees of the Margaret Morris Club and that they were more than familiar with her aims and successes. Lewis for example, would become involved with the Arts League of Service, an educational organization conceived and incubated at the Margaret Morris Club with the intention of making modern art accessible to the public. Among its initial post-war activities were a series of public lectures on “Modern Tendencies in Art.” Morris spoke on Dance, T. S. Eliot on poetry, Eugene Goossens on Music, while Lewis gave the lecture on Painting.Footnote20 After Pound attended a recital by Morris’s former students Hester Sainsbury and Kathleen Dillon, performing as the “Clarissa Company,” he promptly arranged publication of their “Poems for Dancing” in a special issue of Others (October 1915). Pound’s foreword explains their revelatory “new mode of dance poem” as having successfully restored the centrality of rhythm to poetry: “the ‘whole art’” he proclaims “is the words with the dancing” (his italics).Footnote21

In fact, right from her school’s inception in 1910 Morris’s prospectus had promoted the interrelationship between movement and the other arts: “I regard the dance in its broadest sense as presenting action, movement, and grouping of all kinds in strong harmonious forms.”Footnote22 This aspect of her curriculum would become increasingly emphasized: “I first realised the absolute necessity of relating movement with form and colour when studying painting of the modern movement in Paris in 1913. From that time I incorporated it as one of the main studies in my school.”Footnote23 As Nathan Waddell points out, the pedagogic possibilities of synaesthetic creativity were ideas that had united the Paris-based Rhythmists, grouped around the Scottish painter J. D. Fergusson, with whom, in April 1913, Morris had become involved.Footnote24 Their encounter in Paris, as we shall see, was to be mutually galvanizing: “As soon as I got back to London” Morris writes, “I started classes in painting and design along Fergusson’s lines, and made these compulsory.”Footnote25 Incidentally, it was while Kate Lechmere was in France studying under Fergusson that she wrote to Lewis proposing the “modern art Studio in London, run on much the same lines as those in Paris” that would come to fruition as the Rebel Art Centre in March 1914.Footnote26

Joining Morris in London at the outbreak of war, Fergusson took over her painting and sculpture classes. Morris’s students “adored ‘Fergus’ for his patience and efficiency and his faculty for linking up in his lectures the twin plasticities of paint and body movement,” remembered the composer Eugene Goossens who was also closely involved with the curriculum: Fergusson “translated [the] rhythmic improvisations of the dance … into terms of colour and brushstrokes so that … the two arts were synonymous in theory and practice.”Footnote27 Finding no substitute for the creative camaraderie of Parisian artistic life (the Rebel Art Centre had folded after just four months), Fergusson encouraged Morris to start her Club, the popularity of which provided a significant bonus for Morris: “It was a wonderful education for our students to meet such artists as Augustus John, Epstein and Wadsworth, writers like Katherine Mansfield, Middleton Murry, Ezra Pound and the writer-painter Wyndham Lewis.”Footnote28 My intention then is not only to draw attention to Morris’s importance to the development of modern dance but to restore her centrality to early-Modernist creativity more generally.

Little Bright Morris

As a young woman, Margaret Morris rode the wave of the craze for ancient Greek dance. But her involvement with the cultural life of Britain began well before this. The daughter of a minor Victorian painter William Bright Morris by his second wife, Emily Victoria Maundrell, her mother’s scrapbooks testify to a girlhood spent in the theatrical spotlight.Footnote29 “Little Bright Morris” was a child prodigy. At three years old she began giving drawing-room recitals, by five she was entertaining at West End “smoking concerts” with imitations of Ellen Terry and Sarah Bernhardt.Footnote30 From nine she toured for three years with the Ben Greet Shakespearean Company playing Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In her teens she secured a place in the Drury Lane pantomime corps de ballet where “she gained a liberal education into the seamy side of life.”Footnote31 Out of pantomime season she toured with F. R. Benson’s Shakespearean Company, understudying the perennially healthy Mrs Benson for Titania, Juliet, Ophelia, Rosalind and Lady Macbeth. Morris had studied ballet from the age of seven to seventeen with the legendary Drury Lane choreographer John d’Auban and from him picked up her antipathy to the strictures of classical technique.Footnote32

Morris engaged with the political conflicts of her times too, her mother and aunts were active suffrage campaigners and as a sixteen-year old suffragette she filled notebooks with John Stuart Mill’s observations on the subjugation of women, spoke at rallies and provided illustrations for women’s suffrage papers and songsheet covers.Footnote33 In 1910, now a precocious nineteen-year old, she was given the opportunity to choreograph soprano Marie Brema’s staging of Gluck’s Orpheus and Eurydice at the Savoy Theatre. Morris trained the dancers in a technique she had been developing after classes with Raymond Duncan, taking his six classical positions of Greek dance and combining them with “movements of ballet origin such as entrechats and arabesques … in order to equip the dancer as completely as possible, while allowing the fullest personal freedom.”Footnote34 Duncan and his acolytes adopted the robes and sandals of the ancient Greeks for everyday wear and now Morris did the same, an influence that transferred naturally to the costumes and set design of Orpheus.Footnote35 The Daily Express was effusive: “The triumph of the production is Miss Morris’s Dance of the Furies. Nothing like it has ever been seen on the London Stage.”Footnote36 The eminent author and playwright John Galsworthy was at the first night and duly impressed he invited Morris to choreograph and act in his own forthcoming productions The Pigeon (1912) and The Little Dream (1912), commissions she successfully combined with other engagements. She played “Water” in Maurice Maeterlinck’s Bluebird at the Haymarket Theatre (1910), and arranged the dances for Herbert Beerbohm Tree’s Henry V111 at His Majesty’s (1910). Galsworthy would encourage and finance the setting up of her school and they became embroiled in a heady (but unconsummated) love affair.Footnote37

This was an innovative era for the English stage and Morris’s terpsichorean skills were in demand from leading proponents of the “theatre of ideas” or “New Drama” as it was hailed. She worked on Isabelle Pagan’s production of Ibsen’s Peer Gynt at the Little Theatre (1912) and Granville Barker’s Iphigenia in Tauris at the Kingsway Theatre (1912). She collaborated with Rutland Boughton in presenting dancers as “moving scenery” for his Glastonbury Festivals (1913) and produced and performed in Maurice Hewlett’s ballet Callisto at The Royal Court Theatre (1913) where she subsequently took on a short managerial lease to produce her own Season of Dance and Drama, as Margaret Morris and her Dancing Children (1912–1913), the youngest woman actor-manager to have a Royal Court Season. There is not space here for a full account of Morris’s achievements during this period. Her prestigious theatrical engagements between 1910 and 1913 and the range of her contacts among London’s artistic and intellectual circles make impressive reading.Footnote38 Yet her ubiquitous claim to fame for Modernist studies has been little more than the mention, that a Miss Margaret Morris and her Greek Children Dancers performed barefoot at Frida Strindberg’s legendary cabaret club, the Cave of the Golden Calf off Regent Street.Footnote39

Galsworthy ultimately resisted Morris, putting marital fidelity before passion. His termination of their relationship would frustrate her for artistic as much as personal reasons: “if we could have continued to work together I think something of real value to the theatre might have developed” she reflected. However, Morris would find both an antidote to heartbreak and a change of creative direction in Paris where in April 1913 she was engaged to perform with her troupe at the Marigny Theatre on the Champs Elysées.Footnote40 Her reception was encouraging, the Pall Mall Gazette’s Paris Correspondent reporting the French audience as “large and appreciative” of “Miss Morris [as] not merely dancer and ballet mistress, but scene painter and costume designer as well” (April 12, 1913). Nevertheless her intention to “stay there and get hold of the Parisian public” as Galsworthy had encouraged, was sidetracked by what happened next.Footnote41

Paris and Rhythm

Morris had a letter of introduction to J. D. Fergusson from their mutual friend, critic and co-founder of the The New Age, George Holbrook Jackson. Since his move to Paris in 1907 Fergusson had become central to the group that included artists Jessica Dismorr and Anne Estelle Rice (in 1913 Fergusson’s lover of seven years), and writers John Middleton Murry and Katherine Mansfield, all keen espousers of the vitalist philosophy of Henri Bergson which found expression in their magazine Rhythm: Art Music Literature (1911–1913). Fergusson was art editor. Emerging forms of expression in dance were of crucial interest in Modernist circles and Bergson’s utilization of rhythmic sequence and gesture in dance to illustrate his philosophy of time, durée, and individual consciousness had been taken up enthusiastically. “Above all” counselled Clive Bell, “let us dance and devise dances – dancing is a very pure art, a creation of abstract form; and if we are to find in art emotional satisfaction, it is essential that we shall become creators of form.”Footnote42 For Bell and the Rhythmists modern dance was on a par with Primitive art, “the highest art form” because both “dispense[d] with attempts to be representational.”Footnote43 In her dance practice and the pedagogic method she was evolving, Morris embodied the Bergsonian principles which underpinned the aesthetic philosophy of Fergusson and his circle. The previous spring, in London for his solo show at the Stafford Gallery (March 1912) Fergusson and Rice had evidently seen Morris perform. A letter from Holbrook Jackson forwards their compliments: “you will like to hear what they say” he writes, requesting she return the enclosed correspondence.Footnote44

Despite professing “I’m no good at this ‘boosting business’” Fergusson set about publicizing Morris’s appearances at the Marigny amongst his friends.Footnote45 Morris became immersed in Fergusson’s Left Bank milieu and the period would prove a turning point in the development both of her dancing and his painting, confirming their shared commitment to the interdependence of these two arts. Their personal relationship, founded on “advanced” ideals of free love but outwardly conforming to notions of “respectability,” so as not to alienate the parents of prospective students, would last until Fergusson’s death in 1961.Footnote46

Paris provided Morris with an aesthetic re-orientation “momentous in its consequences.”Footnote47 A turn to the traditions of “Indo-China” would distinguish her practice from the Greek revivalist dance sourced by Isadora and Raymond Duncan and was fundamental to the longevity of the Margaret Morris Method.Footnote48 Fergusson, she recalled “led me to share his enthusiasm for Indian and Cambodian art, taking me repeatedly to the Trocadero Museum with its wonderful collection of ancient Eastern sculpture. I made endless sketches of their dancing figures, and this influence can be seen in many of my exercises hitherto based purely on the Greek tradition.Footnote49

“Only they and the Greeks have done it” (Auguste Rodin)Footnote50

The Musée Indo-Chinois housed in the Palais du Trocadéro had been established in 1882 by Louis Delaporte following his encounter with the ruins of Khmer architecture at Angkor Wat in Cambodia almost two decades before. As a young naval officer with a talent for drawing, Delaporte had been assigned to France’s Exploratory Mission of the Mekong (1866) responsible for the pictorial record of its achievements.Footnote51 Imperial rivalry with Britain over claims to Angkor, then under Siamese jurisdiction, motivated the expedition’s reconnaissance trip to the site and the subsequent nationwide dissemination of Delaporte’s drawings. His exoticized images of an ancient city abandoned in the jungle succeeded in engaging the French public. Like his predecessor Henri Mouhot, hailed in 1864 as the French “discoverer” of Angkor Wat, who had described the ruins as “grander than anything left to us by Greece or Rome,” Delaporte would contend that the artistic legacy of the Khmer civilization was more than equal to that of ancient Greece.Footnote52 Determined that there should be a permanent display of Khmer artworks in the French capital, Delaporte set out in 1873 on a return mission to Angkor where, despite Siamese prohibitions, quantities of carvings, statues, and plaster casts of bas reliefs were removed. In 1880 he published Voyage au Cambodge, pronouncing: “Khmer art, issuing from the mixture of India and China, purified, ennobled by artists whom one might call the Athenians of the Far East, has remained the most beautiful expression of human genius in this vast part of Asia.”Footnote53 The eventual foundation of the Musée Indochinois at the Trocadéro in 1882 realized Delaporte’s dream, meanwhile France’s colonial ambitions were also achieved when Angkor was finally ceded to French Indochina in 1907.

Delaporte anticipated that Khmer art would pose an intellectual challenge to French academicians: “it is no longer these majestic colonnades, these great calm surfaces of Greece or Egypt … it is, in short, another form of beauty.”Footnote54 Delaporte’s recognition of “another form of beauty” would foreshadow Modernism’s reordering of aesthetic merit. While the holdings at the Trocadéro were to stimulate the developments of Gauguin, Picasso and the Fauves, the influence of their own museum discoveries on London’s “advanced” sculptors and poets is equally demonstrable. Richard Arrowsmith has traced the seemingly awkward postures of Jacob Epstein’s Strand statues representing Maidenhood directly to the sculptures of Indian temple-dancers he studied in the Asiatic section of the British Museum.Footnote55 Thanks to the efforts of scholars such as Ananda Coomaraswamy and William Rothenstein, Asian art was no longer emblematic of stasis but provided the static perfection of the transcendental. Henri Gaudier-Breszka in BLAST 1 (1914) would challenge the primacy of representational art in sculpture, a legacy of the “fair Greek [who] saw himself only,” while Lewis’s Vorticist painting and Pound’s Imagist poetry were indebted to their absorption of Laurence Binyon’s explication of Chinese “rhythmic vitality” as a representative principle at odd with mimesis.Footnote56 Meanwhile, the ritual poses of the celestial temple-dancers, the divine Apsaras of Angkor Wat, would have a definitive influence on Morris’s choreographic style, her technique from then on incorporating postures that directly echoed those of the bas reliefs she studied at the Musée Indo-Chinois: “I composed a dance inspired by them, (choosing music by Vincent d’Indy), and Anne Estelle Rice, a young American painter to whom I was introduced, designed a costume for me.”Footnote57 Morris doesn’t elaborate further here but Richard Emerson surmises this dance was Le Chant Hindu, performed at London’s Olympia in 1915.Footnote58 The three-act ballet Angkorr, “based upon the rites performed in certain ancient Indian temples” would be her fullest expression of this period. (Stage, 15 February, 1917)

Morris’s visits to the Musée Indo-Chinois coincided with two publications, timely in their attention to dance and, it would seem, additional sources and inspiration for Angkorr. Pierre Loti’s Un Pelerin d’Angkor (A Pilgrimage to Angkor) (1912) is framed by his enamoured portrayal of the Cambodian Royal Ballet whose performance he witnessed in 1904 at the invitation of King Norodom 1 in Phnom Penh.Footnote59 These were the dancers central to Cambodian court tradition, protected as the king’s harem and who, for similar reasons, would captivate Auguste Rodin on their state visit to France in 1906.Footnote60 Loti fancies them the living exponents of the carved Apsaras on the temple walls of Angkor: having escaped from the sacred bas-relief they were “no longer dead, with these fixed smiles of stone, but in the fulness of life and youth, no longer with these breasts of rigid sandstone, but with palpitating breasts of flesh.”Footnote61 Recent postcolonial criticism recognizes that French historiography of the period, in its narration of an unbroken tradition extolling the pure Khmerness of the living dance borne from the statuary of Angkor and negating any intervening Siamese influence, served to justify a “civilizing” French protectorate. Like Loti, Georges Groslier gets implicated in this critique, but in his illustrated study, Danseuses cambodgiennes anciennes et modernes (1913) Groslier took pains to point out significant differences in the costume of the “Khmer women sculpted at Angkor” and the current dance troupe of Norodom’s court. Groslier’s work remains an invaluable resource for dance scholars and given the choreography and costuming of Angkorr it would seem that Morris examined it closely.

According to Groslier, the three movements of the ritual dance of contemporary Cambodian ballet – “the three great gestures” – followed Khmer tradition, comprising harmonious salutations expressed by the undulations of the dancer’s bodies as they proffer lotus flowers.Footnote62 This is replicated in the three acts of Angkorr and in its theme of flowers, while Groslier’s descriptions of the statues at Angkor bear comparison with Morris’s designs.Footnote63 Certain of the Apsaras wear “a great ring-shaped ornament, attached by a cord and dangling between and under the breasts” notes Groslier, “an intriguing accessory seen only at Angkor Wat.”Footnote64 Angkorr’s Harem Dancers feature this detail along with the sampot gathered up with a decorated belt. Some statues, writes Groslier, display “triple point” tiaras similar to a bishop’s “miter” which we see echoed in the headdresses of Angkorr’s Flower Priestesses.Footnote65 Throughout the ballet Morris’s dancers wear upturned slippers in imitation of the hyperextended toes of the barefoot Cambodian dancers: “I had gone beyond the purely Greek tunics and draperies” recalled Morris in the 1960s, “some people did not like my costumes but they would look quite modern now.”Footnote66 She was right, although unlike Chu Chin Chow, which attracted the censure of the Lord Chamberlain, no-one professed to be scandalized by Angkorr’s bare midriffs, veiled as they were by the aura of “art.”Footnote67 In 1984 the Cyril Gerber Gallery in Glasgow held a posthumous exhibition, “The Art of Margaret Morris 1891–1980” in which the costume designs for Angkorr were shown. They feature the bold black outlines of Vorticist influence and are executed in vibrant red, blue and green. The design for “Petals” was retitled “Angkorr” because Morris had chosen this one for her ballet’s advertising poster.Footnote68 It was featured in W. G. Raffé’s Poster Design (1929), its entwined figures exemplifying “essentials in almost abstract design for rhythmic expression.”Footnote69 A review published in The Observer Magazine relates (although unattributed) that the poster had been banned by London Transport in 1917 for being “too sensual.”Footnote70

“Angkorr is new, daringly new; and it is queer, mighty queer” (“A Puzzle in Music and Dance,” The Times, 22 February, 1917, p5.)

The Coliseum’s matinee crowd, anticipating the customary allurements of an “oriental” ballet as they awaited Vesta Tilley’s comic turn on that mid-January Monday, was instead confronted with a blacked out stage. A thunderous gong preceded a rapid drum roll followed by a rhythmic percussive beat that after a four-bar build up, was pierced by a sharp whistle and a flash of light. The scene was illuminated gradually, revealing three groups of three figures, the Flower Priestesses, “facing inwards, heads down, Arms down, covered with cloaks.”Footnote71 As they lifted their elaborately mitred heads and spread out their cloaked arms, a high-pitched baleful flute underscored by the ceremonial tones of the oboe accompanied an incantatory vocal chanting. What ensued over the next fifteen minutes was “a curious weird medley” in which “Miss Morris, in realising her ideals … spare[d] neither musicians, dancers, or her audience” (The Globe, 22 February, 1917, p7).

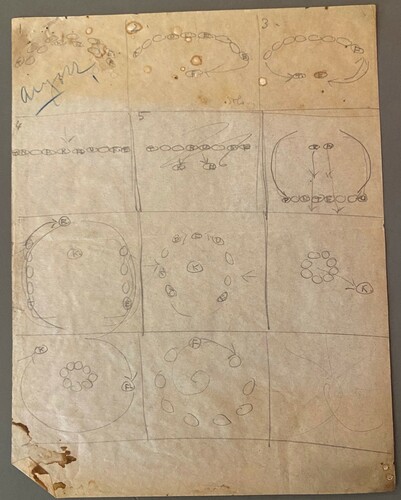

Unfortunately only scraps of Angkorr’s notation survive in the archive although thankfully her handwritten scores for each instrument have been preserved. Of particular interest concerning Morris and Angkorr is the high regard in which this work was held by the composer Philip Heseltine (pseud. Peter Warlock) whose manifesto “Predicaments Concerning Music,” a polemical statement in the style of Pound’s Imagist manifesto (1913), was published contemporaneously in The New Age (May 1917). Among Heseltine’s harangues and strictures is stated: “As yet we have no adequate symbolic language of action to parallel music. Hints for its construction may be taken from dance-experimenters, such as Nijinsky and Margaret Morris” (No 1287, Vol 21, No2). Like Morris, Nijinsky recognized that “notation is indispensable for the development of the art of the dance.”Footnote72 Morris gave an interview to Drawing and Design, in which she refers to the genesis of Angkorr – “the name is that of one of the temples” – as being exemplary of what she believed to be physical movement’s primacy over musical accompaniment: “I designed the dance first, and wrote the music for it afterwards” (April 1917 No 24, Vol 4, p126). She describes the scientific method of dance notation she is evolving as “a symbolic shorthand of the poetry of motion” explaining “the upper hieroglyphs are the arms, and the lower are the legs, the movement being in the direction of the line.”Footnote73 Although she professed to “owe very little to modern productions,” Morris’s extant diagrams for Angkorr in fact suggest an affinity with Nijinsky’s group movements for the “Mystic Circles of the Young Girls” in The Rite of Spring which she attended with Fergusson in Paris in 1913 (See ).Footnote74 While Morris attributes her flamboyant use of colour to her exposure to “the school of Van Gogh,” the waist-length braids of the Harem Dancers may be a nod to Nicholas Roerich’s costumes for the Young Girls.

“‘Angkorr’ is not based on any one particular style” Morris commented, “although there is more of the Cambodian dance in it than of anything else” (Drawing and Design, p126). Elsewhere she explained “a reconstruction of ancient methods would scarcely be sufficient to meet the requirements of today. If dancing is to be a living creative art, it must be progressive, it must be a vital force whose purpose is to interpret life … rather than slavishly to imitate the interpretation of a dead people.”Footnote75 A decidedly original note was struck by Angkorr’s system of onstage costume change, the Flower Priestesses morphing during the First Entre’acte into Petals and after the Second Entre’acte emerging as Harem Dancers. This was described by The Times as “undressing on the stage with the undoing of hooks to music” and more fully in The Star:

As weird a ballet as ever anyone could wish to see. But there is nothing ugly or decadent in its weirdness … The constant changing colour of the dresses reminds one of a beautiful kaleidoscope, and the way this is managed is very original. … the girls wear what seem to be convertible costumes, and as a fresh colour scheme is wanted, each girl undoes a button here and there of her partner’s dress (all in time with the music), and hey presto! An entirely new costume comes into view. (“Weird and Lovely,” The Star, February 24, 1917)

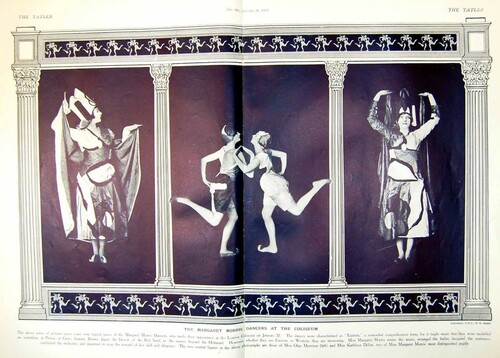

Coomaraswamy’s elucidation of South Asian art and philosophy, of Siva as an “image of the primal rhythmic energy underlying all phenomenal appearances and activity” engaged with modernist aesthetic practice in a way that would find increasing popular relevance in the post-war years in no small part thanks to the work of Margaret Morris.Footnote79 In “Angkor’s heyday” as Groslier explained it, dance was both a venerated art and a religious practice: “The King would learn to dance … moreover was not Siva, the supreme god, known at the great dancer, and is he not often represented in an extraordinary choreographic pose?”Footnote80 Morris now began to emulate the “many headed, many-armed” poses of Hindu deities in her choreography and in carefully composed group tableaux. Artfully photographed in collaboration with London’s most innovative photographers these were assured of publication in the most modish magazines (see ).Footnote81

Overall it would seem that the chief reason for Angkorr’s rejection at the Coliseum was the experimental nature of its music. While “the dancing resolved itself into a series of posturings carried out by nine young ladies evidently capable of better things” wrote the reviewer for The Stage, “the music – rendered by two flutes, one oboe, cymbals, drums and two voices – made one wonder whether the composer was really serious … to put it mildly, ‘Angkorr’ at the Coliseum seems to be so much wasted effort by clever people” (January 25, 1917). For those mainstream critics who ventured down to her theater in Chelsea, the “extreme queerness of its music” continued to baffle. “Miss Morris herself supplied the music This was rather a pity; because various and undeniable as her gifts are, Miss Morris is not yet a remarkable composer” opined the Daily Telegraph (February 22, 1917). Angkorr is “an Oriental affectation – without musical interest … expressed much better by the Russians” reported the Pall Mall Gazette (February 22, 1917). It was perhaps inevitable, not least given the nature of its West End reception, that Angkorr drew such comparisons, The Times concluding: “The spectacle is, shall we say? Cubist; the music … is Stravinkist” (February 22, 1917).

It was the reactionary nature of London’s musical establishment and the jingoism of wartime Britain that had prompted Heseltine to draw up his “Predicaments Concerning Music.” In an article for The Palatine Review he attacked their “promiscuous encouragement of mediocrity” and once again singled out Margaret Morris for praise. Discussing “music as a physical stimulant” Heseltine observes:

in this category we find a great deal of highly interesting primitive music, mainly percussive and purely rhythmical, associated with various forms of dancing. … Its best modern exponents are Igor Stravinsky, Irving Berlin and Margaret Morris. Of these the last two are the more vital in that they are real primitives whose art rises to the surface without the aid of any elaborate technical apparatus. (No 5 March 1917)Footnote82

That these works “were presented before their time” as Lawson reflected of Angkorr, is indicated by the The Times’ summation: “We seem to have fallen on evil days with all these experiments” (February 24, 1917). This might seem overstated given the current situation but it reflects a general association of London’s avant garde with “undesirable” foreign influence. Indeed, Angkorr was a one-woman Gesamtkunstwerk of an exceptional kind. Attention to this forgotten production not only adds formative context to Morris’s career but challenges gendered accounts of early-modernist London that have occluded dance.

Acknowledgements

Fergusson Gallery Archivists: Jenny Kinnear and Amy Fairley. V & A Theatre and Performance Archives: Simon Sladen and Jane Pritchard. To Richard Emerson for many enlightening conversations about Margaret Morris.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anne Witchard

Anne Witchard is Reader in the Dept of English Literature and Cultural Studies at the University of Westminster. Her research interests are in China Studies and Modernism. Recent dance related publications include “Dancing Modern China” in Modernism/modernity Print Plus and “Chiang Yee and British Ballet” in Bevan, Witchard, Zhang eds., Chiang Yee and his Circle: Chinese artistic and intellectual life in Britain 1930–1950 (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2022).

Notes

1 Lawson, A History of Ballet, 136.

2 See Dawson, The Glory of the Trenches, 58. “Last January, during a brief and glorious ten days’ leave, I went to a matinée at the Coliseum. Vesta Tilley was doing an extraordinarily funny impersonation of a Tommy just home from the comfort of the trenches; her sketch depicted the terrible discomforts of a fighting man on leave in Blighty. If I remember rightly the refrain of her song ran somewhat in this fashion: ‘Next time they want to give me six days’ leave, Let ‘em make it six months’ ‘ard.”

3 V & A Theatre and Performance Archives, Margaret Morris File. I am currently transcribing her fifteen minute musical score for Angkorr held at the Margaret Morris Collection, Fergusson Gallery, Perth, Scotland and this will be the subject of a forthcoming paper.

4 From 3 August, 1916 for five years, a record-breaking 2,238 performances.

5 Mullen, The Show Must Go On! 47.

6 The Tatler, Lady’s Pictorial, The Bystander, Illustrated London News, Pearson’s Magazine and The Sketch to name just some.

7 The reception from the gallery was reputed to have lasted a full twenty minutes, giving the Italians “a lesson in [its] own Art of Noises” according to the Times, June 16, 1914, 5.

8 Marinetti, “The Variety Theatre Manifesto,” Daily Mail 21 November, 1913.

9 See Morris, My Life in Movement, 27. From now, MLiM.

10 See Emerson, Rhythm and Colour, 31.

11 Morris, MLiM, 25, 27. For more on the MM Theatre and Club see Emerson, Rhythm and Colour.

12 Morris, MLiM, 33.

13 MMC club leaflet on which Morris has scribbled “not trying to offend audience!”

14 With the exception of Desmond MacCarthy, then prominent theater critic and school patron. His wife Molly was the sister of Morris’s benefactor (and student) Greek scholar Gerald Warre-Cornish (1874–1916). There are numerous reasons for London’s modernist alliances and animosities, among them Faith Binckes’ observation of Bloomsbury’s distaste for the “commitment to the kind of ‘self-culture’ envisaged by T.P. O’Connor and Holbrooke Jackson” (both of whose publications, T.P.’s Weekly and The New Age were strongly supportive of Morris), see Modernism, Magazines, and the British Avant-Garde, 140.

15 See, for example, Naereboot, “In Search of a Dead Rat,” 54.

16 Hofer, “Education,” 78.

17 Cork, Art Beyond the Gallery, 191.

18 Lewis, Rude Assignment, 135.

19 Waddell, “Lawrence Atkinson, Sculpture.” https://doi.org/10.26597/mod.0003.

20 Poorly prepared Lewis kept losing his thread, producing an unfortunate “effect of incoherence” according to a report in The Athanaeum, see O’Keeffe, Some Sort of Genius, p?

21 Foreword to the Choric School. Others, 1:4 (October, 1915).

22 School Prospectus MMC.

23 Morris, Margaret Morris Dancing, 86.

24 Waddell, “Lawrence Atkinson, Sculpture.”

25 Morris, MLiM, 30.

26 Meyers, “Kate Lechmere’s ‘Wyndham Lewis from 1912’,” 161.

27 Goossens, Overture and Beginners, 139.

28 Morris, MLiM, 33.

29 Held at the MMC.

30 She was described in The London Magazine as “perhaps the youngest earner the world has ever known.” Vol 9, (1903), 320.

31 Morris, MLiM, 19.

32 She is singled out in d’Auban’s obituary in the Arts Gazette, 29 April 1922. “Several of the most accomplished dancers of the day were once his pupils, among them Margaret Morris.”

33 Her design for Ethel Smyth’s anthem The March of the Women (1911) is regularly reproduced on calendars and tea towels. Her teenage notebooks at MMC.

34 Morris, MLiM, 20–21.

35 Her “green and purple draperies” made her interviewer for Pearson’s Magazine “wonder why anyone should ever want to wear something so senseless as a modern frock.” She tells him: “nothing would induce me to desert sandals and go back to boots and shoes” (November, 1913, 466 – 468).

36 Cited in Morris, My Galsworthy Story, 22.

37 Galsworthy memorialised their relationship in a novel, The Dark Flower (1913). Morris published his letters and her account of their affair some fifty years later in My Galsworthy Story. Its timing coincided with the TV airing of Galsworthy’s The Forsyte Saga, the BBC’s first major international syndication, watched by 160 million viewers worldwide.

38 See her address books and diaries, MMC.

39 Morris describes the experience in My Galsworthy Story, 105.

40 Morris, MGS, 129.

41 Letter to Morris from Galsworthy dated April 26 1913, in Morris, MGS, 124.

42 Bell, Art, 284.

43 Gillies, Henry Bergson and British Modernism, 55.

44 Letter 19 March 1912 from Holbrook Jackson to Morris, MMC.

45 Morris, The Art of J. D. Fergusson, 65.

46 See their personal correspondence, MMC.

47 Morris, MLiM, 28.

49 Morris, MLiM, 30.

50 Rodin cited in Groslier, Cambodian Dancers, 320.

51 Osborne, River Road to China, 39.

52 Mouhot, Travels in the Central Parts of Indo-China, 275–9. In fact his journey to Angkor had been financed by the British, see Falser, “The first plaster casts of Angkor for the French métropole: From the Mekong Mission 1866–1868, and the Universal Exhibition of 1867, to the Musée khmer of 1874,” 52. Mouhot advocated regeneration by European conquest.

53 Delaporte, Voyage au Cambodge, 12.

54 Ibid.

55 Arrowsmith, Modernism and the Museum, 37–9.

56 In BLAST 2 Pound reviews Binyon’s The Flight of the Dragon quoting “it is not essential that the subject-matter should represent or be like anything in nature; only it must be alive with a rhythmic vitality of its own,” 86.

57 A vital part of the modern movement of his time, d’Indy’s posthumous reputation has been damaged by his profession of anti-Semitic views. Perhaps the music Morris chose was Istar (1898): “On a visit to the British Museum in 1887 [d’Indy] had been captivated by the Assyrian mural sculptures,” see Andrew Thomson, Vincent d’Indy and his World, 111. Morris would supplant Rice, but they all remained on friendly terms.

58 Conversation with Richard Emerson.

59 Loti’s book was translated into English the following year with the by then anachronistic title, Siam. Morris could have read it perfectly well in French. It was also serialised in four editions of L’Illustration between 16 Dec 1911 and 6 Jan 1912.

60 King Norodom’s successor Sisowath accompanied the Cambodian Royal Ballet on a month’s visit to France in 1906. They performed at the Elysée Palace in Paris and then the Colonial Exposition in Marseilles whence they were followed by Rodin who sketched them obsessively.

61 Loti, A Pilgrimage to Angkor, 68.

62 Groslier, Cambodian Dancers, 159.

63 Ibid., 122.

64 Ibid., 151.

65 Ibid., 141.

66 Morris, MLiM, 30.

67 See Emerson, Rhythm and Colour, 50.

68 They are reprinted in the accompanying Margaret Morris: Drawings and Designs and the Glasgow Years, 13, 14, 15.

69 Raffé, Poster Design, 48.

70 Observer 14 April 1984. One can see the influence of Fergusson’s dance painting Les Eus (c 1911) and, in 1987, the design would be wrongly attributed him in Printmaking in Britain 1775–1965: Two Centuries of the Art of the Print in Britain at the William Weston Gallery.

71 Notebook in box labelled “choreography notes on specific dances,” MMC.

72 Hutchinson Guest, Nijinsky’s Faune Restored, 145.

73 Published as The Notation of Movement (London: Kegan Paul, Trench & Trubner, 1928).

74 The dancers, listed in order of Morris’s cipher, who performed Angkorr at the Coliseum, January 15, 1917: Kathleen Dillon (K), Flossie Jolley (Fl), Beatrice Filmer (F), Olga Morrison replaced by Penelope Spencer (P), Violet Faucheux (V), Louise Thrift (T), Millie Escekay (E), Nina Woodhead (N), Rita Thom (R).

75 Told to Fred Daniels, “The Modern Development in Dancing,” Windsor Magazine, 1925, 493–504, 494.

76 Fry, “Oriental Art” 1910.

77 Coomaraswamy, Dance of Siva, 102.

78 Ibid.

79 Ibid., 109.

80 Groslier, Cambodian Dancers, 124.

81 Coomaraswamy, Dance of Siva, 69. Walter Benington (whose work will be familiar from his iconic portraits of Gaudier-Brzeska) took the publicity stills for Angkorr in this vein. Others were taken by Benington’s studio partner Malcolm Arbuthnot while The Tatler commissioned Claude Harris and E. O. Hoppé, and The Bystander, Hugh Cecil.

82 See Smith, The Occasional Writings of Philip Heseltine (Peter Warlock), 67.

83 Gray, Musical Chairs, 112, Smith, Occasional Writings, 70.

Bibliography

- Arrowsmith, Richard. Modernism and the Museum: Asian, African and Pacific Art and the London Avant-Garde. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Bell, Clive. Art. London: Chatto & Windus, 1914.

- Binckes, Faith. Modernism, Magazines, and the British Avant-Garde. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Binyon, Laurence. The Flight of the Dragon: An Essay on the Theory and Practice of Art in China and Japan, Based on Original Sources. London: John Murray, 1911.

- Carrell, Chris, and Jim Hastie, eds. Margaret Morris: Drawings and Designs and the Glasgow Years. Glasgow: Third Eye Center, 1985.

- Coomaraswamy, Ananda K. The Dance of Siva: Fourteen Essays. New York: The Sunwise Turn, 1918.

- Coomaraswamy, Ananda K. History of Indian and Indonesian Art. London: Edward Goldston, 1927.

- Cork, Richard. Art Beyond the Gallery: In Early 20th Century England. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 1985.

- Dawson, Coningsby. The Glory of the Trenches: An Interpretation. New York, London: John Lane Company, 1918.

- Delaporte, Louis. Voyage au Cambodge. L’Architecture Khmer. Paris: Delagrave, 1880.

- Emerson, Richard. Rhythm and Colour: Hélène Vanel, Loïs Hutton and Margaret Morris. Edinburgh: Golden Hare, 2018.

- Falser, Michael. “The First Plaster Casts of Angkor for the French Métropole: From the Mekong Mission 1866-1868, and the Universal Exhibition of 1867, to the Musée khmer of 1874.” Bulletin de l’Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient 99 (2012): 49–92.

- Fry, Roger. “Oriental Art.” Quarterly Review 212 (1910): 226. 234–235.

- Gillies, Mary Ann. Henry Bergson and British Modernism. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1996.

- Goossens, Eugene. Overture and Beginners: A Musical Autobiography. London: Methuen, 1951.

- Gray, Cecil. Musical Chairs: or Between Two Stools Being the Life and Memoirs of Cecil Gray. London: Home and van Thal, 1948.

- Groslier, Georges. Cambodian Dancers: Ancient and Modern (1913). Florida: DatASIA Press, 2012.

- Hofer, Matthew. “Education.” In Ezra Pound in Context, edited by Ira B. Nadel, 75–84. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Hutchinson Guest, Ann. Choreo-graphics: A Comparison of Dance Notation Systems from the Fifteenth Century to the Present (1998). London: Taylor and Francis, 2014.

- Hutchinson Guest, Ann. Nijinsky’s Faune Restored. Netherlands: Gordon and Breach, 1991.

- Lawson, Joan. A History of Ballet and its Makers. London: Isaac Pitman & Sons, 1964.

- Lewis, Wyndham. Rude Assignment: An Intellectual Autobiography (1950). Santa Barbara: Black Sparrow Press, 1984.

- Loti, Pierre. A Pilgrimage to Angkor (1913). Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 1996.

- Meyers, Jeffrey. “Kate Lechmere’s ‘Wyndham Lewis from 1912’.” Journal of Modern Literature 10, no. 1 (March 1983): 158–166.

- Morris, Margaret. The Art of J. D. Fergusson: A Biased Biography (1974). Perth: J. D. Fergusson Art Foundation, 2010.

- Morris, Margaret. Margaret Morris Dancing. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd., 1926.

- Morris, Margaret. My Galsworthy Story. New York: Humanities Press, 1968.

- Morris, Margaret. My Life in Movement. London: Peter Owen, 1969.

- Morris, Margaret. The Notation of Movement. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd., 1928.

- Mouhot, M. Henri. Travels in the Central Parts of Indo-China (Siam), Cambodia, and Laos, During the Years 1858, 1859, and 1860. London: John Murray, 1864.

- Mullen, John. The Show Must Go On! Popular Song in Britain During the First World War. Farnham: Ashgate, 2015.

- Naereboot, Frederick. “‘In Search of a Dead Rat’: The Reception of Ancient Greek Dance in Late Nineteenth-Century Europe and America.” In The Ancient Dancer in the Modern World: Responses to Greek and Roman Dance, edited by F. Macintosh, 39–56. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- O’Keeffe, Paul. Some Sort of Genius: A Life of Wyndham Lewis. London: Pimlico, 2001.

- Osborne, Milton. River Road to China: The Mekong River Expedition 1866-73. Newton Abbot: Readers Union, 1976.

- Simister, Kirsten. Living Paint: J. D. Fergusson 1874-1961. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing Company, 2001.

- Smith, Barry, ed. The Occasional Writings of Philip Heseltine (Peter Warlock) Volume 1. London: Thames Publishing, 1997.

- Thomson, Andrew. Vincent d’Indy and his World. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996.

- Waddell, Nathan. “Lawrence Atkinson, Sculpture, and Vorticist Multimediality.” In Modernism/Modernity Printplus. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.26597/mod.0003.