ABSTRACT

To explore school nurses’ roles globally through their own perceptions of what they do and how they do it and to compare the realities for the role its representation in professional literature. A comprehensive narrative literature review, using ENTREQ guidelines, with “qualitizing” of the quantitative literature, and athematic analysis was carried out. Findings were reviewed in relation toestablished theory. CINAHL, Medline, Cochrane Library, and Embase were systematically searched from 2000–2021. Included studies focused on school nurses’perceptions of their own practice. Five themes: direct care, health promotion, collaboration,support from school and health authorities and promoting the school nurses’role were found. These themes were closely aligned to the National Associationfor School Nurses’ framework for 21st century practice. However, the schoolnurses signposted areas where they need support in carrying out their job tothe highest standard. School nurses are important to support thehealth needs of students while at school. They also, particularly in areas likethe United Arab Emirates where resources are being invested in the role, have a unique role to play in health promotion, leading to improved health literacy,as positive health behaviors tend to be learned young. However, worldwide, thepotential for the school nursing role needs to be recognized and supported by healthand education providers, by families and within the schools for its fullpotential to be achieved.

Introduction

School nursing services have long been introduced throughout educational settings worldwide with a view to improving overall population health. However, the role of school nurses can be described as diverse; where policies and practices may have evolved over time and are influenced by either evidence-based research, bureaucratic policymakers or a combination of both (Hall, Citation1999). Whatever the case may be, understanding the defining features of school nurses can be a complex yet valuable endeavor to further professionalize the role. School nurses represent an initial image of nurses amongst children and youth. They are also responsible for carrying out preventive public health services such as immunizations, education through various means and on numerous topics, and a vast array of services from recording measurements of height and weight to providing advice on sexual and mental health (Hoekstra et al., Citation2016; Stockman, Citation2009). Only through continuous exploration and analysis of the school nurse role can we develop a deeper understanding of its ability to address the ever-changing needs of students and how to address them through various cultural contexts and perspectives

Background

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has a relatively young, but fast developing health service. The school nurses’ roles and responsibilities there are influenced by bureaucratic policymakers due to the scarcity of nursing research in the country (Al-Yateem et al., Citation2016). Further to that, only 3% of the UAE’s nursing workforce are national nurses while the rest are transitory expatriates (McCreaddie et al., Citation2018), presumably coming with an image of school nursing as observed in countries where they have lived and/or practiced. As the UAE is prepared to invest many resources into school nursing with a view to building a healthy population (School Clinic Regulation, Citation2016), it is important to understand how the role is evolving with a view to optimizing this exciting investment in population health. To this end we decided to explore the role of the school nurse worldwide from the perspective of school nurses. Although they will obviously adhere to local guidelines, this is the working knowledge which expatriate nurses will bring to UAE and which will therefore underpin their practice.

Aim

The aim of this narrative review was to explore school nurses’ roles globally through their own perceptions of what they do and how they do it and to compare the realities for the role to its representation in professional literature.

Methods

To this end, a narrative review of the literature, examining the experiences and working responsibilities of school nurses worldwide, was carried out. Reporting is guided by the ENTREQ guidelines (Tong et al., Citation2012)

Design

On scoping the literature it was clear that there were both qualitative and quantitative literature available which would contribute to an understanding of this complex area. Traditionally it has been difficult to combine data from both paradigms in a single review with convergent and sequential synthesis designs for doing so debated (Hong et al., Citation2017). As convergent methods have proved more popular, we adapted the methods offered by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) (Stern et al., Citation2020) by “qualitizing” those studies which used quantitative methods so that themes could be identified.

Search methods

To conduct an effective and efficient search, the research question utilized a PEO (Population, Exposure, Outcomes) approach. The words applied to achieve maximal impact were:

Population: School nurses

Exposure: Schools

Outcomes: Roles/Responsibilities/Perceptions/Experiences/Attitudes

Nonetheless, the population and exposure were merged in the search terms for clarity and convenience as the term school nurse addresses both population and exposure.

The limitations set for the search included articles in the English language, full text and abstract available, publishing date between 2000–2021, and lastly, from peer-reviewed journals. These limitations were set to ensure the author understands the language articles are written in, have accessibility to read abstracts and subsequent full text, view articles published within the last 21 years to ensure inclusion of any seminal literature, and from peer-reviewed journals to ensure credibility and rigor of selected articles.

The search

A comprehensive literature search was conducted utilizing Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Medline (EBSCO), Cochrane Library, and Embase (OVID). A manual search was also conducted by reviewing reference lists of already identified studies to extract additional studies (Cronin et al., Citation2008). Boolean operators (AND and OR) were utilized to refine the search strategy by combining or using alternate words. The Boolean Logic System utilizes relationship between keywords by using AND, OR and NOT (Cronin et al., Citation2008).

Critical appraisal

All studies identified in this research were proofread by the author to ensure they met the inclusion criteria. Furthermore, JBI critical appraisal checklists for qualitative and analytical cross-sectional studies were utilized to critically appraise studies included in the narrative review.

Data analysis

After “‘qualitizing’” of the studies (Stern et al., Citation2020), Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2019) reflexive thematic analysis was employed to conceptualize the themes. In their conversation with Nikki Hayfield (Braun et al., Citation2022) Braun and Clarke were adamant that the practice of using thematic analysis on quantitative data, as described by Boyatzis (Citation1998), was completely unsuitable for analysis use with their methods. The process of qualitizing should overcome this problem. These conceptualized themes were synthesized into a narrative review through comparison with the National Association of School Nurse’s (NASN) framework for 21st Century School Nursing Practice (NASN, Citation2024).

Findings

Search outcome

Results from the database search yielded 283 studies after removal of four duplicates while other sources yielded no additional records. In the screening phase, record titles and abstracts were skimmed for their relevance where 173 records were not suitable to include in the narrative review. The third eligibility phase examined records to assess for suitability of inclusion deeming 73 records not relevant and were therefore excluded. The remaining 37 articles were comprehensively screened and examined where 26 articles were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. Therefore, 11 articles were included in the narrative review based on their relevance in addressing the research question ().

Data abstraction

Studies included in the literature review were a combination of qualitative and quantitative studies where seven studies explored the school nursing role utilizing constructivist principles whilst four other studies examined the role by employing post-positivist principles. As summarized in , the studies were methodologically diverse and incorporated various means of data collection including focus groups, one to one interviews, closed ended questionnaires, and surveys. Moreover, data analyses varied and ranged from thematic analysis to establishing associations and correlations through statistical means. It was possible, however, to identify qualitative themes in those studies which used quantitative methods and we therefore were able, while abstracting data, to qualitize the findings (Stern et al., Citation2020).

Table 1. Studies by country, objectives, design, participants, sample size and major findings “qualitized”.

Quality appraisal

All eleven selected articles were appraised in accordance with the JBI checklists and found to be of sufficiently good quality to be included in the review (see supplementary material).

Thematic analysis

Numerous overlapping focuses were induced from the studies with 5 themes, supported by 15 subthemes. The five overarching themes were 1. Direct care, 2. Collaboration, 3. Health promotion, 4. Support from school management and health authority and 5. Promoting the role of the school nurse ().

Table 2. The themes conceptualized from the studies.

Theme 1: direct care

This came in many forms with general agreement that school nurses are responsible, to some extent, for routine health checks (Hoekstra et al., Citation2016; Stockman, Citation2009). A lot of their time can also be taken up with caring for children with chronic illness such as asthma and allergies (Krause-Parello & Samms, Citation2011). This role extends to making appropriate referrals (Barnes et al., Citation2004; Stockman, Citation2009), which overlaps with the theme of collaboration.

Direct care extends to dealing with psychological, emotional and sexual health (Borup & Holstein, Citation2011; Hoekstra et al., Citation2016), although there was some evidence that this role is not completely recognized and supported by other professionals (Clancy et al., Citation2012)

Theme 2: health promotion

School nursing roles have evolved throughout history from carrying out periodic medical inspections to promoting student health and wellbeing. Health promotion amongst the examined studies was seen as a defining feature to school nurses’ functioning (Barnes et al., Citation2004; Krause-Parello & Samms, Citation2010, Citation2011; Stockman, Citation2009). Some countries have enacted mandatory health education and promotion sessions to aid in curbing the spread of various ailments amongst school pupils (Barnes et al., Citation2004). Health promotion is seen as developing from an activity which is dependent on family support in younger children to a tool for the empowerment of older children through health literacy (Borup & Holstein, Citation2011). Nonetheless, in order to carry out efficient and effective health promotion, collaboration, support, and marketing the role need to be further addressed within respective countries to further advance school nurses’ roles and improve the health and wellbeing of students, families and the surrounding community. Mäenpää et al. (Citation2012) found that communication between families, the school nurse was problem based rather than routine, and they suggested that better collaboration would lead to better care.

Theme 3: collaboration

Collaboration in the examined studies was portrayed on various levels amongst numerous stakeholders. In the UK, for example, Hoekstra et al. (Citation2016) elaborated on collaboration as a pivotal foundation for school nurses to function optimally as they work in collaboration with other healthcare professionals to improve students’ health and wellbeing. While in the USA, Krause-Parello and Samms (Citation2010, Citation2011) emphasized the importance of collaboration as 79.4% of school nurses agreed collaborating with teachers and administrators significantly improved overall wellbeing of students. Likewise in countries like Finland, Australia, Sweden and Norway, collaboration or as Mäenpää et al. (Citation2012) coined it, cooperation, is essential. It is vital in order to ascertain various needs of students ranging from health education and promotion to referrals outside of the school setting whether to family counselors, drug and addiction services, mental health services, etc. (Clancy et al., Citation2012; Klein et al., Citation2012; Reutersward & Hylander, Citation2016).

Theme 4: support

The support theme encompassed three sub-themes including nursing empowerment, support from school management and health authorities (Barnes et al., Citation2004; Hoekstra et al., Citation2016; Klein et al., Citation2012; Krause-Parello & Samms, Citation2010; Mäenpää et al., Citation2012; Reutersward & Hylander, Citation2016; Reutersward & Lagerstrom, Citation2010). Nursing empowerment was regarded in most studies as a major driving force to enacting health promotion activities and directly correlated with school nurses’ image amongst students, parents, teachers and school management. Therefore, how school nurses perceived themselves and their role impacted how the previously mentioned stakeholders perceived the school nursing role. School nurses’ roles and responsibilities were affected by the amount of support received from teachers, head teachers and other school staff. Moreover, it can take at least 2 years for new school nurses to fully integrate in a school setting, meaning that school nurses must take initiative in promoting their role and services (Barnes et al., Citation2004). Support from health authorities underpinned the quality of communication between school nurses and health authority stakeholders who are responsible for generating policies that guide school nurses’ scope of practice. Ultimately, active communication between stakeholders can aid in linking policy to practice to further enhance school nursing services. Therefore, support was addressed on various levels involving numerous stakeholders highlighting empowerment and collaboration as main factors to enhancing support.

Theme 5: marketing the role

Marketing the role was also a shared theme as awareness of school nurses’ functioning was ambiguous in terms of roles, responsibilities, and scope of practice. General confusion around the role was experienced not only amongst parents and healthcare professionals but also amongst teachers, head teachers and other school staff. Role confusion was prevalent in most countries like Australia, UK, Finland, Denmark and the USA highlighting the importance of marketing the role amongst the many collaborators school nurses work with (Barnes et al., Citation2004; Hoekstra et al., Citation2016; Klein et al., Citation2012; Krause-Parello & Samms, Citation2010; Mäenpää et al., Citation2012; Reutersward & Hylander, Citation2016). Ultimately, it is the responsibility of the school nurse to market her/his role whether by attending school assemblies, putting introductory notes in teachers’ pigeonholes, or through health promotion activities involving active communication with various stakeholders. By marketing their role, various stakeholders can further recognize school nurses’ roles and responsibilities, eventually heightening awareness on what the role entails and to what extent school nursing services extend to.

Discussion

School nurses hold a pivotal role in improving public health through health education and promotion activities, drop-in sessions, classes and initiatives (Hoekstra et al., Citation2016; Klein et al., Citation2012; Krause-Parello & Samms, Citation2010; Reutersward & Hylander, Citation2016). The needs of school-based populations have shifted incrementally over the decades from infectious communicable diseases tackled by immunizations to an array of other needs like caring for chronic illnesses such as diabetes, asthma and mental/sexual health (Al-Yateem et al., Citation2016). Moreover, advances in technology and availability of the internet/smart phones pose a new challenge for school nurses in addressing cyberbullying, welfare needs and safeguarding of younger vulnerable pupils (Byrne et al., Citation2018).

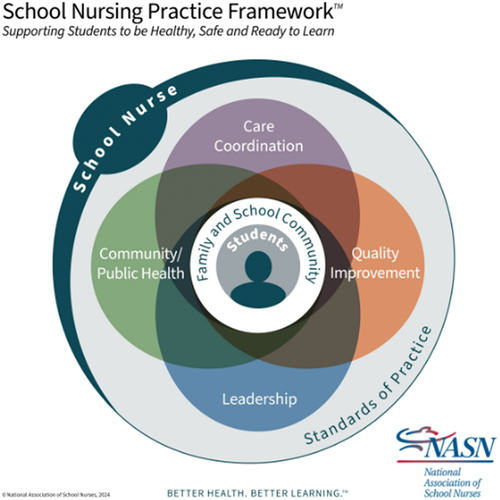

Our aim was to explore the experiences of school nurses worldwide and, having done so, the conceptualized themes from our narrative review were compared with the NASN Framework for 21st Century School Nursing Practice (National Association of School Nurses [NASN], Citation2024, ). This framework could be described as a “gold standard” for modern school nursing practice and is representative of literature from other countries (Loschiavo, Citation2020; NASN, Citation2017; Selekman et al., Citation2019). We were interested to see how the actual experiences of school nurses measured up to the theoretical literature on role. Central to the NASN framework is the student, surrounded by family and school community in a nonhierarchical fashion. Supporting the student, family and school community are 4 domains, care coordination; leadership; quality improvement and community/public health. Every domain interlaps with the others highlighting the complexity of the school nurse role. The standards of practice encapsulate the entire framework representing utilization of up-to-date evidence-based research to operationalize the framework efficiently and effectively.

Our direct care theme directly mirrored the central responsibilities of school nurses to keep their students safe, healthy and ready to learn. We found that in many countries the school nurses described protocol-driven rather that student-centric care, with only the more experienced school nurses developing more student-focused practice (Reutersward & Lagerstrom, Citation2010). We found that a more student (child) focused practice developed as the students got older (Borup & Holstein, Citation2011) reflecting what happens in mainstream children’s and young people’s nursing (Coyne et al., Citation2016). There is a strong suggestion however that dealing with mental, sexual and emotional health issues learned skill which school nurses tend to gain only with experience (Klein et al., Citation2012; Reutersward & Lagerstrom, Citation2010). Mäenpää et al. (Citation2012) finding that communication with families was problem driven rather than routine suggests that there is scope to wrap the family, as well as the school community, more tightly around the student, particularly in the younger age groups, and this might be possible in practice where the service is resource rich such as in the UAE. While school nurses must be guided by an agreed scope of practice, our findings suggest that when the autonomy of the school nurse is increased, it is possible to interpret the guidelines in a more child and family centric way (Reutersward & Hylander, Citation2016). Thus school nursing can be used as a vehicle to improve overall health, but particularly that of children with chronic conditions which require “hands on” care.

Our collaboration theme maps directly with the care coordination domain, where the framework (NASN, Citation2024) suggests that the health and safety of the student are supported by collaborative efforts between school nurses and the various stakeholders in child health. This is imperfectly achieved in the real world with school nurses seeing their efforts to collaborate with parents undermined by unsupportive school administration policies (Krause-Parello & Samms, Citation2011). Moreover, administrative support is vital in supporting the school nurse as a health promoter (Klein et al., Citation2012), which will ultimately lead to quality improvement (NASN, Citation2024). We can view the theme which we called “promotion of the school nurses’ role” as equating to the leadership domain (NASN, Citation2024). It then becomes easy to see how, when the various stakeholders: family, school education/administrative staff and various health providers, understand and respect the school nurse role, both health-dependant readiness to learn for the students and quality improvement become more achievable for the school nurse. It would take effort in overcoming the thread of role confusion, which ran through the literature (Barnes et al., Citation2004; Hoekstra et al., Citation2016; Mäenpää et al., Citation2012). There is a reciprocal relationship between the school nurse acting as a leader in order to empower the profession and the school nurse being empowered to lead.

Further research is required to explore exactly what support from school administration, health authority and families is needed to enhance the role at both school and health authority levels. Furthermore, assessing nursing empowerment can aid in highlighting the level of competency and drive amongst school nurses to act as change agents which can be seen as an enabler to promoting their role and obtaining required support.

Lastly, our health promotion theme maps directly to the community/public health domain. Although our subjects concentrated on health education within the school environment, there is scope for health promotion be made age appropriate and collaborative (Leahy et al., Citation2015). Recently a project in Germany, where school nursing is not well established, showed that concentrated efforts within the schools improved the health literacy of not only the students, but their teachers and their families (de Buhr et al., Citation2020). There is strong evidence internationally that health literacy, learned at a young age, equips children with the cognitive ability of make good choices throughout their lives (Nash et al., Citation2021). With more education and support school nurses are well positioned to assess the needs of students, family, and surrounding community. However to customize health promotion educational materials and activities to best suit the community’s needs, but they may need to embrace digital/ehealth strategies in order to best reach their target group (Champion et al., Citation2019). Moreover, assessing the needs of the above-mentioned stakeholders can empower the community to take charge of their health by providing them the autonomy to voice their needs and increase awareness of the prevalent community/public health needs.

With the UAE willing to invest so much in the school nurses role a conscious effort is needed to learn from these experiences, brought by the immigrant nurses, and to build a school nursing service which is truly reflective of the NAAN framework. As an added bonus, understanding the role of school nurses and the evolution of their tasks and responsibilities can carry significant value in improving the general image of nurses in UAE, highlighting the profession’s ability to contribute to public health efforts to address the ever-changing needs of populations for generations to come. Improving nurses’ image through showcasing a professional school nurse is crucial to tackle the increasing worldwide shortage as the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates 9 million additional nurses and midwives will be needed by 2030 (WHO, Citation2020). Furthermore, nurses play a critical role in disease prevention, health promotion and delivery of primary and community care (WHO, Citation2020). As initial exposure to nurses, particularly school nurses, amongst young children and adolescents shapes their perceptions of what nurses and nursing in general has to offer (Hoeve et al., Citation2013), enhancing these interactions through understanding and improving the role may serve to market the profession, inevitably reducing the gap on the forecasted shortage.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this review is that much consideration was given to the way in which qualitative and quantitative research can be thoughtfully combined in a single review. The reviewers have expertise in health, in children’s nursing and in sociology. The main weakness is that only research findings published in the English language could be used in the review.

Conclusion

In order to apply NASN’s theoretical framework within the UAE’s context, five domains need to be reevaluated in the light of what school nurses are reporting from their experiences in the real world. The standards of practice domain necessitates reviewing the current scope/s of practice to ensure it is contextually appropriate and up to date; but school nurses also need to be educated and empowered to interpret guidelines in light of real world problems. The care coordination domain requires assessing and extending collaboration between school nurses and their stakeholders. The leadership and quality improvement domains necessitate exploring and strengthening the support already in place for the school nurses and promoting the school nurse role through robust campaigning. Lastly, the community/public health domain requires assessing student, family, and surrounding community’s public health needs to contextually adapt the school nurse role and responsibilities to best suit the needs of the country.

Author contributions

Made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; MA, KB and BB

Involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; MA, KB and BB

Given final approval of the version to be published. Each author should have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content; MA, KB and BB

Agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. MA, KB and BB

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (32.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/24694193.2024.2377202.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Al-Yateem, N., Docherty, C., Brenner, M., Alhosany, J., Altawil, H., & Al-Tamimi, M. (2016). Research priorities for school nursing in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The Journal of School Nursing, 33(5), 393–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840516671783

- Barnes, M., Courtney, M. D., Pratt, J., & Walsh, A. M. (2004). School-based youth health nurses: Roles, responsibilities, challenges, and rewards. Public Health Nursing, 21(4), 316–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0737-1209.2004.21404.x

- Borup, I., & Holstein, B. (2011). Family relations and outcome of health promotion dialogues with school nurses in Denmark. Nordic Journal of Nursing Research, 31(4), 43–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/010740831103100409

- Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Hayfield, N. (2022). ‘A starting point for your journey, not a map’: Nikki Hayfield in conversation with Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke about thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 19(2), 424–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2019.1670765

- Byrne, E., Vessey, J. A., & Pfeifer, L. (2018). Cyberbullying and social media: Information and interventions for school nurses working with victims, students, and families. The Journal of School Nursing, 34(1), 38–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840517740191

- Champion, K. E., Parmenter, B., McGowan, C., Spring, B., Wafford, Q. E., Gardner, L. A., Thornton, L., McBride, N., Barrett, E. L., Teesson, M., Newton, N. C., Chapman, C., Slade, T., Sunderland, M., Bauer, J., Allsop, S., Hides, L., Stapinksi, L., Birrell, L., & Mewton, L. (2019). Effectiveness of school-based eHealth interventions to prevent multiple lifestyle risk behaviours among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Digital Health, 1(5), e206–e221. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(19)30088-3

- Clancy, A., Gressnes, T., & Svensson, T. (2012). Public health nursing and interprofessional collaboration in Norwegian municipalities: A questionnaire study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 27(3), 659–668. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01079.x

- Coyne, I., Hallström, I., & Söderbäck, M. (2016). Reframing the focus from a family-centred to a child-centred care approach for children’s healthcare. Journal of Child Health Care, 20(4), 494–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493516642744

- Cronin, P., Ryan, F., & Coughlan, M. (2008). Undertaking a literature review: A step-by-step approach. The British Journal of Nursing, 17(1), 38–43. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2008.17.1.28059

- de Buhr, E., Ewers, M., & Tannen, A. (2020). Potentials of school nursing for strengthening the health literacy of children, parents and teachers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2577. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072577

- Hall, D. (1999). School nursing: Past, present and future. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 81(2), 181–184. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.81.2.181

- Hoekstra, B., Young, V. L., Eley, C. V., Hawking, M. K. D., & McNulty, C. A. M. (2016). School nurses’ perspectives on the role of the school nurse in health education and health promotion in England: A qualitative study. BMC Nursing, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-016-0194-y

- Hoeve, Y., Jansen, G., & Roodbol, P. (2013). The nursing profession: Public image, self-concept and professional identity. A discussion paper. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(2), 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12177

- Hong, Q., Pluye, P., Bujold, M., & Wassef, M. (2017). Convergent and sequential synthesis designs: Implications for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Systematic Reviews, 6(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0454-2

- Klein, J., Sendall, M. C., Fleming, M., Lidstone, J., & Domocol, M. (2012). School nurses and health education: The classroom experience. Health Education Journal, 72(6), 708–715. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896912460931

- Krause-Parello, C., & Samms, K. (2010). School nurses in New Jersey: A quantitative inquiry on roles and responsibilities. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 15(3), 217–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6155.2010.00241.x

- Krause-Parello, C., & Samms, K. (2011). School nursing in a contemporary society: What are the roles and responsibilities? Issues in comprehensive pediatric nursing. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 34(1), 26–39. https://doi.org/10.3109/01460862.2011.555273

- Leahy, D., Burrows, L., McCuaig, L., Wright, J., & Penney, D. (2015). School health education in changing times: Curriculum, pedagogies and partnerships. Routledge.

- Loschiavo, J. (2020). School nursing: The essential reference. Springer Publishing Company.

- Mäenpää, T., Paavilainen, E., & Åstedt‐Kurki, P. (2012). Family–school nurse partnership in primary school health care. Scandanavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 27(1), 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01014.x

- McCreaddie, M., Kuzemski, D., Griffiths, J., Sojka, E. M., Fielding, M., Al Yateem, N., & Williams, J. J. (2018). Developing nursing research in the United Arab Emirates: A narrative review. International Nursing Review, 65(1), 93–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12405

- Nash, R., Patterson, K., Flittner, A., Elmer, S., & Osborne, R. (2021). School‐based health literacy programs for children (2‐16 years): An international review. The Journal of School Health, 91(8), 632–649. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.13054

- NASN. (2017). School nursing scope and standards of practice (3rd ed.). Silver Springs, ANA.

- National Association of School Nurses. (2024). Framework for 21st century school nursing practice: National Association of School Nurses. Retrieved June 19, 2024, from https://www.nasn.org/nasn-resources/framework

- Reutersward, M., & Hylander, I. (2016). Shared responsibility: School nurses’ experience of collaborating in school‐based interprofessional teams. Scandinavian Journal of Care Sciences, 31(2), 253–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12337

- Reutersward, M., & Lagerstrom, M. (2010). The aspects school health nurses find important for successful health promotion. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 24(1), 156–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2009.00699.x

- School Clinic Regulation. (2016). Ministry of health and prevention. https://www.mohap.gov.ae/School%20clinic%20Regulation.pdf

- Selekman, J., Shannon, R. A., Yonkaitis, C. F. (2019). School nursing: A comprehensive text. F. A. Davis.

- Stern, C., Lizarondo, L., Carrier, J., Godfrey, C., Rieger, K., Salmond, S., Apóstolo, J., Kirkpatrick, P., & Loveday, H. (2020). Methodological guidance for the conduct of mixed methods systematic reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(10), 2108–2118. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00169

- Stockman, T. (2009). Different expectations can lead to confusion about the school nurse’s role. British Journal of School Nursing, 4(10), 478–482. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjsn.2009.4.10.45592

- Tong, A., Flemming, K., McInnes, E., Oliver, S., & Craig, J. (2012). Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 12, 1–8.

- World Health Organisation. (2020). Nursing and Midwifery. https://www.who.inter/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/nursingandmidwifery