Abstract

This article contributes to the geographical understanding of how mobile online presence enabled by smartphones transforms human spatial practices; that is, people’s everyday routines and experiences in time and space. Contrasting a mainstream discourse concentrating on the autonomy and flexibility of ubiquitous (anywhere, anytime) use of social media, we examine new and mounting constraints on user agency. Building on time-geographic theory, we advance novel insights into the virtualities of young people’s social lives and how they are materialized in the physical world. Critically, we rework the classical time-geographic conceptions of bundling, constraints, rhythms, and pockets of local order; draw on the emerging literature on smartphone usage; and use illustrative examples from interviews with young people. We suggest a set of general and profound changes in everyday life and sociality due to pervasive and perpetual mediated presence of friends: (1) the emergence of new coupling constraints and the recoupling of social interaction; (2) the changing rhythms of social interaction due to mediated bundles of sociality becoming more frequent and insistent; (3) the shifting nature of the streaming background of online contacts, which are becoming more active, intervening in, and intruding on ongoing foreground activities of everyday life; and (4) the reordering of foreground activity as well as colocated and mediated presences, centering on processes of interweaving, congestion and ambivalence, and colocated absence. Key Words: intervening background, local and mediated pockets of order, online copresence, rhythm, spatial practice.

本文对于由智能手机所促成的行动网路上的在场,如何改变人类的空间实践——亦即人们在时空中的日常起居与经验——之地理理解作出贡献。与社交媒体的普遍使用(不论何时何地)具有自主性与弹性之主流论述相反的是,我们检视对使用者主体产生的崭新且加剧的限制。我们根据时间地理学理论,将崭新的洞见推进年轻人社交生活的虚拟性,及其如何在实体世界中实践。我们批判性地修改地方秩序的束缚、限制、节奏与小块地区之经典时间地理概念,并运用访谈年轻人的解说案例。我们提出因普遍且永久透过媒介的朋友的在场所导致日常生活与社会性中一系列普遍且深刻的改变:(1)崭新连结限制的浮现和社会互动的再连结;(2)因受媒介束缚的社会性而改变的社会互动节奏变得更为频繁且持续; (3)网路接触中改变中的串流背景之本质,变得更为积极、干预并侵入每日生活中进行的前景活动;以及(4)前景活动与同一地点和中介的在场之重新排列,聚焦相互交织、拥塞与矛盾,以及同一地点的缺席之过程。关键词:干预的背景,地方与中介的小块区域秩序,网路共同在场,节奏,空间活动。

Este artículo contribuye a entender geográficamente la manera como la presencia móvil en la red, posibilitada por los teléfonos inteligentes, transforma las prácticas espaciales de la gente; o sea, las rutinas cotidianas y experiencias humanas en el tiempo y en el espacio. Contrastando un discurso generalizado que se concentra en la autonomía y flexibilidad del uso ubicuo (donde quiera, en cualquier tiempo) de los medios sociales, nosotros examinamos nuevas y crecientes limitaciones sobre la agencia del usuario. A partir de la teoría geográfica del tiempo, desarrollamos nuevas perspectivas en las virtualidades de la vida social de la gente joven y sobre cómo ellas son materializadas en el mundo físico. En plan crítico, reelaboramos sobre las clásicas concepciones del tiempo en geografía sobre empaquetamiento, limitaciones, ritmos y bolsones de orden local; nos basamos en la literatura emergente sobre el uso del teléfono inteligente; y utilizamos ejemplos ilustrativos derivados de entrevistas con gente joven. Sugerimos la aparición de un conjunto de cambios profundos y generales en la vida cotidiana y en la socialidad debido a la penetrante y perpetua presencia de los amigos promovida por los medios sociales: (1) la aparición de nuevas limitaciones acopladas y el reenganche de la interacción social; (2) los ritmos cambiantes de la interacción social debido a que los paquetes mediados de socialidad se hacen cada vez más frecuentes e insistentes; (3) la naturaleza cambiante del trasfondo fluente de los contactos en red, que cada vez son más activos, intervinientes y entrometidos en las actividades que siguen su curso de cotidianidad; y (4) el reordenamiento de la actividad principal lo mismo que las presencias co-localizadas y mediadas, centrándose en procesos de entrecruzamiento, congestión y ambivalencia, y ausencia co-localizada. Palabras clave: bolsas de orden locales y mediadas, co-presencia en red, práctica espacial, ritmo, trasfondo interviniente.

In a recent small-scale study of young students’ everyday lives, repeating a study conducted in 2000, it became evident that large parts of social life and interaction with friends had moved online (Thulin Citation2017).1 The smartphone was always there, immediately accessible, and social media was always on. The smartphone was either in the foreground of the individual’s activity or standing by in the background, demanding attention. During the day, online social interaction took place whenever and wherever there was “dead time.” At other times and places, online interaction was seamlessly integrated with other activities (both offline and other online activities) but consistently also interfered with ongoing activities and attention.

Compared with the early 2000s, before the ubiquity of smartphones, particularly the projects and practices of companionship and maintaining social relations had gained a qualitatively new level of independence from fixed places and times. Absent friends who were not in direct physical proximity were always near in a virtual sense. Important ingredients of friendship—such as making and updating plans, exchanging and discussing thoughts and experiences, hanging out in groups, confirming feelings, sharing and keeping track of vital events and happenings in each other’s lives—had taken on new virtual dimensions. Furthermore, “smart” practices had reoriented mobile social communication toward visual messaging, many-to-many contact, and mediated copresence as an intensified background setting. Text messaging and voice calls, which completely dominated mobile phone usage among preceding cohorts fifteen years ago, have now been displaced from the center of social communication. As noted by many (e.g., Ling Citation2012; Bertel and Stald Citation2013; Bertel and Ling Citation2016; Thulin Citation2018), a first wave of mobile phone usage has been superseded by a second one; that is, the contemporary era of smartphones and social media, enabling a continuous stream of social contact online.

This radical relaxation of space and time constraints on social interaction represents a new situation. It augments the mediated copresence of absent friends.2 It concerns qualitative differences in the transmission of presences, as regards location, continuity, and rhythm. It encourages an incessant stream of (potential) contact running in parallel in the background, integrating or intervening in the ordinary stream of activities making up everyday life. Moreover, it seems that the collective outcome of many individuals’ autonomous, flexible, and ubiquitous uses of smartphone technology produce and reinforce new and emerging constraints on user agency and activity.

Aim and Scope

Knowledge of how this increasingly extensive and always mediated presence of “absent friends” influences people’s everyday lives is scarce and scattered, requiring further study. Whereas research has so far investigated the increased flexibility afforded by the smartphone (e.g., regarding its instrumental and expressive functionalities) as well as concerns over second-order effects (e.g., anxiety, stress, and sleep disorders), this article concentrates on the emergence of new bindings and constraints potentially associated with the widespread use of new technology. In doing so, we aim to advance the theoretical understanding of how smart mobile media are reshaping patterns of online social contact and influencing human spatial practices. We focus on young people, who have long been established users of such media. Starting from a time-geographic theoretical perspective (e.g., Hägerstrand Citation1970, Citation1982, Citation1985; Ellegård Citation2000, Citation2019), we concentrate on and develop two related issues of spatial concern: first, how the intensified streams and rhythms of mediated copresence impose new constraints on daily life and, second, how mediated copresence, perpetually on in the background, intersects with and reorders foreground activities and colocated presences and how these processes are negotiated in practice.

In elaborating on these issues, we draw on experiences from the current literature on how mobile information and communication technologies (ICTs) are incorporated in the lives of young people and cite examples from a recent qualitative study of mobile phone practices among youth performed by the authors (Thulin Citation2018). The study included qualitative interviews with eighteen typically middle-class senior high school students, all highly experienced smartphone users, living in the city of Gothenburg, Sweden. Because the aim of this article is to theorize, the empirical materials are used to illustrate selected points rather than to offer comprehensive evidence for all arguments.

In the next section we briefly review the literature on how young people initially domesticated mobile phones and on the ongoing changes due to the spread of smartphones. Then we present the interviews illustrating the subsequent theoretical discussion. We then start developing the theoretical approach leaning on time geography situated in the context of current thought on virtual geographies. After that, we elaborate on the issues just introduced and discuss how smartphones have influenced and reshaped patterns of online social contact, the presence (and absence) of other people, and the situated stream of actions making up daily life. The final section concludes and discusses the need for future research.

Literature Review: The Meaning and Function of Mobile Media among Youth

Abundant literature on mobile ICTs emphasizes how young people use and incorporate technologies in their everyday lives by attributing meaning and function to them. This focus on user agency largely entrenches an “anyplace, anytime” story of decoupling, flexibilization, and reduced constraints on contact in which people seize the mediated opportunities to transcend the space–time bindings and frictions of social interaction. Early studies illustrated how first-generation mobile phone technology and its unique opportunities for instant and ubiquitous contact quickly moved to the center of youth social life across the Global North. Remarkably quickly, it became an indispensable part of social contact, being used in planning and coordinating social activities and get-togethers (Ling and Yttri Citation2002; Larsen, Axhausen, and Urry Citation2006; Thulin and Vilhelmson Citation2007, Citation2009) and for confirming friendship and building confidence, particularly among close friends (Johnsen Citation2003; Kasesniemi and Rautiainen Citation2004; Licoppe Citation2004; Oksman and Turtiainen Citation2004; Ling and Yttri Citation2006; Thulin Citation2018). Recent studies, predominantly in European and North American contexts, demonstrate that the shift to smart technologies—mobile devices that integrate the phone, Internet access, and a camera and that were widespread among young people by around 2010—has further developed and redefined the basic role and functions of mobile media. For example, mobile media are becoming more visual, group oriented, and distributed and more likely to include contact with weak social ties (Katz and Crocker Citation2015; Bayer et al. Citation2016; Bertel and Ling Citation2016; Thulin Citation2018).

Previous literature suggests that a range of varied and interrelated projects dominate young people’s mobile phone usage (e.g., Ling Citation2004; Cope and Lee Citation2016). To support, maintain, and advance social contact with friends is the most important of those projects.3 From a spatial practice perspective, the mobile phone has become integral to realizing and coordinating offline get-togethers over different time horizons (from impulsive to planned), and an ongoing practice of updating plans has gained importance in the contact patterns of young people (Ling and Yttri Citation2002; Larsen, Axhausen, and Urry Citation2006; Ling and Lai Citation2016; Thulin and Vilhelmson Citation2019a). With the spread of smartphones, microcoordination is more often undertaken in groups rather than person-to-person, involving not only close friends and family but increasingly weak social ties as well (Ling Citation2017).

Another tendency with implications for spatial practices is that mediated social contacts among young people increasingly involve hanging out with friends in “mobile messenger groups” of different sizes and linked to various social networks (e.g., close friends and classmates) but also including an extended network of weaker ties (Bertel and Ling Citation2016; Ling Citation2017). Online groups are considered always-open meeting places where one can hang out and socialize with friends, joking, teasing, talking about mundane situations and major events, discussing sensitive topics and schoolwork, and following the conversation in the group even when one is not directly involved.

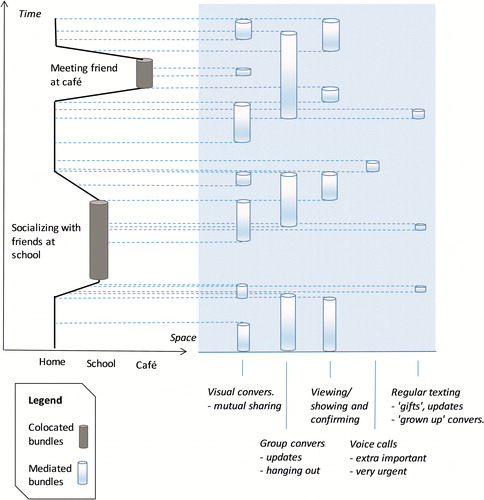

Social mobile use is largely linked to the mutual sharing of everyday contexts (in terms of activities, feelings, emotions, and thoughts) maintained throughout the day in multiple settings. Such sharing entails the exchange of virtual “gifts” that support feelings of friendship and closeness (Johnsen Citation2003; Oksman and Turtiainen Citation2004; Ling and Yttri Citation2006). From previously being text based (short message service [SMS]; Ling and Yttri Citation2002), this sharing has become increasingly image oriented and visual with smartphones (Hunt, Lin, and Atkin Citation2014; Thulin Citation2018). Social mobile use now tends to involve acts of viewing, showing, and confirming, through which one gets glimpses of sender-selected exciting or attractive parts of one another’s lives—travel, pleasing images, places, and parties—after which confirmation is sought through “likes.” Images are the focal point of such mobile use, with viewing and displaying being increasingly common smartphone practices (Katz and Crocker Citation2015; Bayer et al. Citation2016). In line with the basic understanding of adoption as a never-finished and perpetual process, recent literature also finds that traditional nonsmart mobile phone usage (i.e., person-to-person text messaging and voice calls) has been radically repositioned. Texting and calling have lost their centrality in youth culture and are now mostly associated with grown-up contact with parents and partners (Bertel and Ling Citation2016; Thulin Citation2018).

Interviews: Illustrations of Current Smartphone Use

Earlier, references were made to a recent qualitative study of smartphone practices among Swedish youth (Thulin Citation2018). We use quotations from these interviews to illustrate arguments made in the sections that follow. The interviews were performed by one of the authors in 2016 and included eighteen senior high school students living in the city of Gothenburg, Sweden.4 The sample was made up of ten women and eight men sixteen to eighteen years old, who were predominantly middle class and born in Sweden. The interviewees were highly experienced smartphone users who had owned smartphones for several years. They were selected through personal visits to four classes at a high school in the city center. Interviewees first recorded their daily activities and ICT use in a three-day time-use diary. The diaries served as a tool for raising awareness and prompting interviewees to reflect on their mobile phone use and context before being interviewed. The interviews lasted fifty to seventy minutes and were structured according to themes related to the main types of ICT use and spheres of everyday activity. They were recorded and subsequently transcribed. The analytical work, aided by the use of NVivo software, focused on identifying main tendencies in mobile phone practices, roles, and experiences, which were then discussed in light of previous literature.

The data are limited to the extent that they relate to the doings and sayings of a small group of young people who were quite homogenous in their background and demographic characteristics. Nonetheless, the materials that are available for this group are rich and open up the possibility to theorize the relationships between spatial practices and smartphone usage for young people in a way that can inform further research with other social groups in other places.

Theoretical Approach: Virtualizing Time Geography

As shown earlier, previous literature has suggested how mobile digital media have afforded new ways of socializing in space and time for young people. It has done so by considering the detailed uses, meanings, and functions of such media and recognizing how online social contacts are becoming as important and taken for granted in social life as are face-to-face meetings and offline interaction.

In terms of theory, the dominant theoretical approach has been the domestication approach (Silverstone and Haddon Citation1996; Bakardjieva Citation2005; Bertel and Ling Citation2016; Haddon Citation2016, Citation2011), especially outside geography. This approach foregrounds the “domesticating” role of user agency in human–mobile media relationships, meaning that individuals are not regarded as passive receivers and consumers of technology but as highly active in the ongoing process of negotiating and renegotiating technology’s meanings, functions, and representations within the contexts of the peer group, youth culture, and society at large. Other lines of theorizing view the adoption of mobile communication through the lens of actor–network theory and closely related approaches. These emphasize the complex interrelationships and multiple agencies of active elements in sociotechnological arrangements (McBride Citation2003; Couldry Citation2008). Smartphones are not considered neutral intermediaries of individual intentions, as they are equipped with apps, software, and code “calling for” attention, immediacy, responsiveness, and maintenance (e.g., audio and visual notifications, “like” buttons, “points” for maintenance, and alerts on opening messages) that trigger individual awareness and action (Crang, Crosbie, and Graham Citation2006; Kinsley Citation2014; Schwanen Citation2015; Rose Citation2017). Still other ideas tend to stress problematic and addictive phone use (e.g., Kuss and Lopez-Fernandez Citation2016), and others consider the smartphone a “social entity” (e.g., Carolus et al. Citation2018), related to its owner not as a mere technical device but rather as an emotional “digital companion,” constantly in touch with its user and perpetually interacting with her, transforming human–human relationships into human–smartphone relationships. In short, most theoretical approaches recognize that humans and devices play active and entangled roles in the emerging composition, rhythms, constraints, and orders of online social interaction that are examined here.

In terms of geographical research on smartphones and other perpetually online technologies, inquiries (as reviewed by, e.g., Kinsley Citation2014; Rose Citation2017; Ash, Kitchin, and Leszczynski Citation2018) have been more concerned with how smartphones are embedded in the reproduction of urban space; for example, via smart city apparatuses (Coletta and Kitchin Citation2017), surveillance systems (S. Graham Citation2013), and in the performance of identities (Boy and Uitermark Citation2017). The agency of technological infrastructures is then set in focus. Also highlighted is the production of differences in access to and use of mobile technology associated with intersecting axes of social difference (gender, race, class, etc.), regional and local labor and housing markets, and digital infrastructures (e.g., Gilbert Citation2010; M. Graham et al. Citation2014; Silm and Ahas Citation2014). As emphasized by Rose (Citation2017) and others, however, studies focusing on the digitalization of human spatial activities and practices are limited and light on theoretical development, although specific contributions have been made concerning the fragmentation of projects and activities (e.g., Couclelis Citation2004; Hubers, Dijst, and Schwanen Citation2008), the relaxation of time–space constraints (Schwanen and Kwan Citation2008), and mobility practices at various scales (Vilhelmson and Thulin Citation2008).

In the following sections, we move beyond the meanings and functions of smart mobile media and devices, looking deeper into the massive stream of mediated presence being produced by smartphones and the human–device entanglements involved. By building on and further elaborating time-geographic theory, we examine how mediated contact is materialized in and reshapes the social lives and time–space practices of young people. The classical concepts and understanding of time geography for approaching human–technology interrelations are well recognized and shall not in extenso be reiterated here (see original work by Hägerstrand [Citation1982, Citation1985], and further applied by Ellegård [Citation2000, Citation2019] and Krantz [Citation2006]). Simply put, the perspective visualizes how basic relationships constrain and shape the individual’s time–space practices in the physical world. The starting point is the individual as an indivisible corporeal entity, constantly localized somewhere and always in temporal motion. The basic time-geographic model of the individual life path (or space–time trajectory) emphasizes the continuous chain of activities in various places that make up the broader projects of everyday life. The conduct of activities is not arbitrary but shaped and ordered, in accordance with a number of basic conditions and constraints and in constant competition with all other potential activities the individual must, should, and needs to take part in (within a twenty-four-hour time budget). New communication technologies play a key role by unlocking restrictions and expanding the range of possible time–space practices. Technological development might also create new constraints and lock-ins, however, especially over time, as a result of many people’s technology use and the fact that people are closely involved in each other’s time use, places, activities, and projects.

Being a corporeal approach basically oriented toward the material aspects of bodies, artifacts, and contexts making their paths through time and space, the shortcomings of the (original) time geography approach to virtual geographies have been noted (e.g., Shaw Citation2010; Ash, Kitchin, and Leszczynski Citation2018). As argued by Shaw (Citation2010), although time-geographic concepts were developed mainly for human activities in physical space, these concepts are relevant and applicable to human activities enabled by ICTs such as the Internet and mobile phones. Yet, they need to be modified and elaborated. A number of previous efforts have been made to “virtualize time geography” by incorporating conceptions of virtual space, mobility, and access. For example, by developing the concept of human extensibility originally proposed by Janelle (Citation1973), Adams (Citation2000, Citation2005) broadened the classical model of the time–space path by integrating almost all kinds of bodily, mental (emotional), virtual, and mediated relationships across space. The corporeal individual is then associated with many fluctuating extensions operating at varying distances and according to varying chronologies (see also Kwan Citation2016). Couclelis (Citation2009), also drawing on the extensibility concept, developed a conceptual framework of time–space behavior in a multidimensional structure, enabling representation and analysis of the increasing variety of activities carried out in “cyberspace” with the help of ICTs. Shaw and Yu (Citation2009) also made important contributions by developing geographic information system (GIS) design and methods for analyzing and visualizing interactions in hybrid physical and virtual space.

This article contributes to previous efforts by advancing the time-geographical understanding and representation of human social interaction and shared activity in virtual space. Also, we add to previous studies by focusing on how this virtuality is materialized in everyday life. In the following, we rework classical time-geographic conceptions of bundles, coupling constraints, rhythms, and pockets of local order into an era of mobile digital media and view them from a mediated space perspective. By also drawing on incipient literature on smartphone usage and sampling from our own interviews with young people, we discuss a set of profound changes that reinforce the locking in and linking of activities in everyday life. More specifically, we first highlight the materialization of new constraints on user agency and the recoupling of social interaction. Second, we identify the changing rhythms of social interaction due to mediated bundles of sociality becoming more insistent. Third, we uncover the shifting nature of the streaming background of online contacts, which are becoming more active, intervening in and intruding on ongoing foreground activities of everyday life. Discerning the potential reordering of colocated and mediated presences, we suggest three common processes of interaction: interweaving, congestion and ambivalence, and colocated absence.

Recoupling and the Changing Rhythms of Social Interaction

Bundling: Corporeal and Mediated

The literature conceptualizes online, or mediated, presence in various ways. One important starting point is the concept of copresence, originally referring to physical, colocalized contact between people or between people and objects (Goffman Citation1963; Hägerstrand Citation1970; Giddens Citation1991) and increasingly associated with online communication and contact in virtual environments (e.g., Zhao and Elesh Citation2008; Grabher et al. Citation2018). Using the mobile phone, the Internet, and social media, people establish a sense of presence and continuity; for example, with family members when at work or traveling, with colleagues when at home, or with friends after moving to distant places (e.g., Bittman, Brown, and Wajcman Citation2009; Haunstrup Christensen Citation2009; Aguiléra, Gulliot, and Rallet Citation2012). Licoppe (Citation2004) discussed how young people, through frequent, short, and “momentous” exchanges (seen as communication “gifts”), early on developed a connected presence, a sense of continuous togetherness, between friends. In the same vein, Ito and Okabe (Citation2005) argued that the continuous nature of mobile exchanges creates a state of background awareness of friends, located at the midpoint of the traditional contact–noncontact binary. Smartphones reinforce the potential constant copresence of absent friends. This enables flexibility and choice in social interaction, yet also introduces new bindings, requirements, and constraints in everyday life that are important to explore.

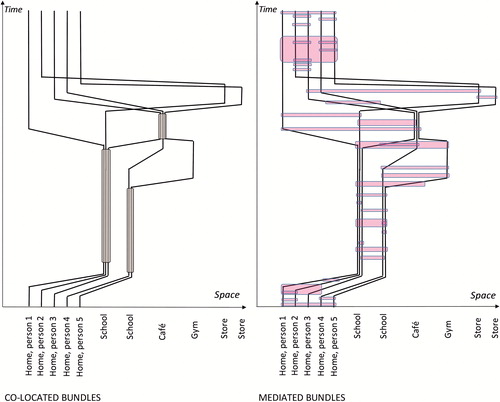

The theoretical understanding of the constraining latency of online presence in the context of smart mobile technologies can be developed by drawing on the time-geographic conceptualizations of presence, coupling constraints, and bundles (Hägerstrand Citation1970, Citation1982, Citation1985). In time geography, the notion of the presence–copresence of people and things is a main issue stemming from the basic need to be within and out of reach, to couple and decouple, when performing daily activities (Ellegård Citation2019). It relates to the concept of bundle and associated constraints and the axiomatic fact that any form of corporeal social interaction and meeting rests on the convergence—or bundling—of the life paths of individuals in time and space. In time geography, a bundle is usually displayed as a grouping of two or more individual life paths colocated in time and space, revealing the times of arriving at and leaving a place and conveying information about the amount of time the involved individuals spend together. portrays a principal example illustrating the time–space trajectories of five friends (all carrying smartphones) during the course of one weekday and their internal (within-group) bundling. The left side of portrays the colocated bundling of the friends, in school and after school at a café. Not all of them meet in person on this particular day as they go to different schools.

Figure 1. Colocated and mediated bundles. The figure portrays a principal example illustrating the time–space trajectories of five friends with smartphone devices during the course of one weekday and their internal (within-group) bundling, viewed from a colocation and a mediation perspective.

The formation and dissolution of couplings are shaped by, and generate, time–space constraints. For example, hanging out at a café with friends is fixed, as it must take place within given time windows (e.g., outside school hours, in the evening, and on weekends) and at an accessible place not too far away, reducing the range of other activities the persons involved can undertake at the same time. Bundling is negotiated and shaped in a social context and highly dependent on the capabilities, activity patterns, and time schedules of the involved individuals.

Although the concept of bundling was originally developed with reference to offline activity and copresence in the physical world, it can improve our understanding of the preconditions and implications of mediated copresence and online social interaction. Everyday life activities and projects also rely on what could be regarded as mediated bundles, following the basic logic of coming together and leaving, being present and absent, taking up time and fitting within the sequence of everyday activities. The right side of portrays all of the mediated bundling occurring between the friends during this day in various constellations of two or more persons, sometimes going on in parallel. (Note: Left out from is that some of the bundles might also include other individuals; e.g., classmates or friends of a friend.) If combining the two bundling perspectives we will find a multilayered weave of colocated and mediated presences and absences; for example, when being with friends at the café and interacting with absent friends on the smartphone or when socializing online with the persons you have next to you in the classroom. We then also find occasions of total decoupling among this group of friends.

Yet, as further developed later, mediated bundles also differ from corporeal ones; for example, as regards the basic dynamics of immediacy (of entrance and disengagement) and synchronization (sociospatial, activity, and temporal) between the individuals involved. Notably, mediated bundles are also human–technology entanglements, requiring that individuals and their contact devices (i.e., smartphones) always be together. The contact devices are not neutral intermediates of presence but designed objects (equipped with apps, software, and code) that actively inflect the mediated compositions and rhythms emerging (Kinsley Citation2014; Schwanen Citation2015; Rose Citation2017). In applying the concept of mediated bundles, we first consider the aspects of bundling that enable decoupling and recoupling.

The Decoupling and Recoupling of Mediated Copresence

Mobile ICTs and mediated social contact are often discussed in terms of their inherent flexibility; that is, their capacity to lift time–space constraints and decouple online contact from specific places, such as the home or workplace, and certain “free” times of day. Especially since the uptake of text messaging, the requirement for synchronic and mutually attentive interaction has been relaxed as well. This engendered potential for individuals to be “present” anytime and anywhere promotes the ideals of flexibility and choice. Arguably, however, a fuller understanding of the use and implications of mobile technologies must recognize that mediated social contact basically relies on couplings, not in an offline or colocated sense but as bundles of online coattentiveness and meeting.

Theoretically, as illustrated in , the streams of online bundles could differ in content, purpose, and meaning. As regards personal involvement, they might differ in size, including two or many individuals, and be initiated by the individual or by someone else in one’s close or extended social network. Mediated bundles’ frequency, intermittency, regularity, and duration can vary. They can be handled passively (noted but not further reacted to) or actively (eliciting immediate or delayed responses), be momentary or extended in duration, and be more or less mutual in terms of required synchrony. They can occur simultaneously, involving multiple (and competing) threads of different sizes and characters that the individual must attend to concurrently. From a time-geographic perspective, online bundles of social interaction are expected to add new layers of coupling constraints to young individuals’ everyday lives and social contact, thereby engendering new kinds of spatial and temporal fixities and dependencies. As suggested later, this is closely linked to an emerging discourse of semisynchrony. Paradoxically, many people’s decoupled use of social media has undesirably turned into a process of recoupling. One important mediator of this concerns the changing rhythm of social interaction as regards pace and synchronization of demanded involvement.

Figure 2. Offline and online copresence in an era of smart mobile media. A time-geographic representation of corporeal (offline) social bundles and mediated (online) social bundles intersecting in time and space. Mediated bundling via different kinds of social media (allowing visual conversation, text messages, group conversation, etc.) intersects with corporeal activities at a certain rhythm during the day.

By conceptualizing rhythm, Hägerstrand (Citation1982) supplemented the notion of a continuously flowing time by stressing the role of pacesetters in the synchronization of bundles of activities. Pacesetters prompt the starting and ending times of colocated presence in terms of working hours, school hours, and opening hours of shops, restaurants, cinemas, and sports facilities, and schedules of TV programs, public transport, and so on. Drawing on Parkes and Thrift’s (Citation1980) chronogeography and Lefebvre’s (2004) rhythmanalysis, multiple geographers have suggested that rhythm is a multifaceted concept (e.g., Schwanen et al. Citation2012; Coletta and Kitchin Citation2017). One aspect concerns the varying character and constraining power of rhythms being biological, physical, or social, for example, inscribed by institutions or by collective agreement. Rhythms differ in frequency, intensity, and regularity, sometimes interweaving harmoniously, sometimes colliding and clashing, and sometimes going on in parallel (Edensor and Holloway Citation2008; Schwanen et al. Citation2012). They form polyrhythmic ensembles (Parkes and Thrift Citation1980) involving place or, rather, the individual in her concrete space and time setting. In this ensemble, certain pacesetters have stronger capacities to impel others to take over and adjust to their rhythms. Mulıcek, Osman, and Seidenglanz (Citation2016) suggested that collectively regulated pacesetters, whether of local (concerning work or consumption) or external character (e.g., TV), have declined considerably in importance in postindustrial societies, whereas individually defined pacesetters are on the increase, shattering the uniform rhythm of a place into a mosaic of rhythms.

Accordingly, rhythms come in many shapes, entities, and agencies—from church bells, factory whistles, and door openings and closings to timetables and phone signals. To this is now added the rhythm and pacesetting enabled by online mobile technologies and mediated social contact, on the one hand, seemingly releasing individuals from many institutionalized schedules (e.g., when and where to watch films, buy food, or work), on the other, prompting and binding individuals’ everyday spatial practices in new ways. Moreover, the pacesetting capacity of smartphones also lies in the design of the smartphones’ technology and this is where the sociomaterial entanglements as emphasized by Kinsley (Citation2014), Rose (Citation2017) and Schwanen (2015), for example, come into play. Smartphone apps, designed for visual dialogue, instant sharing of context, live group interaction, easy and quick confirmation, and so forth, are in other words intertwined in the rhythms of online sociality emerging.

Changing Rhythms of Online Social Interaction

Recoupling is marked by the changing rhythm of mediated social coupling evolving in an era of smart mobile media. Rhythm concerns the frequency, intermittency, duration, and, not least, intensity of social contact that binds and structures individual attention and time use over a day. This change in rhythm partly depends on the resynchronization potential of a technology originally designed for the flexibility of asynchronous communication. The first wave of mobile usage was associated with the emergence of a discourse of asynchronicity, largely linked to the use of SMS, which could be done “as time allowed,” freed from the necessity of temporal copresence and immediate response (Kwan Citation2002; Yin, Shaw, and Yu Citation2011). It was portrayed as a nonintrusive, instantaneous, and under-the-radar form of contact or background awareness (Ling Citation2004; Ito and Okabe Citation2005). Recent studies note the emergence of a discourse of semisynchronicity associated with the growth of smart mobile media (Rettie Citation2009; Thulin Citation2018). Here copresence is viewed as neither discretionary/asynchronous nor fully mutually attentive. Rather, online copresence is coupled with increased social expectations and a built-in logic and rhythm of immediacy and responsiveness; for example, in the urgency of real-time updates as vital last-minute microadjustments or modified plans for the day and week, calls for impulsive meetings “at short notice,” or the ability to track friends and acquaintances in school and the city. Although smartphones facilitate the process of updating, largely directing it to mobile messenger groups, their rise has also led to a broader context (from a wider network) of notifications, information, and adjustments to track (Bertel and Stald Citation2013; Ling Citation2017), escalating the felt need and effort to keep updated. Certain groups, the members of which might have different power, influence, skill, or dominance, as well as individuals (e.g., high-status friends and acquaintances or “influencers”) are then perceived as more important to follow and respond to. They can act as online pacesetters. Online copresence is also found in the developing practices of continuous mutual sharing of everyday contexts through visual conversations—fast and dialogue-like rhythms of image exchange (Hunt, Lin, and Atkin Citation2014; Katz and Crocker Citation2015; Bayer et al. Citation2016)—through rapidly providing comprehensive information, answering the “never-ending” contextual questions arising from distant social interaction (“Where are you, what are you doing?”), as well as through expressing one’s personal identity and self-image (Litt and Hargittai Citation2016; Robards and Lincoln Citation2017). As examples from our case study illustrate, slowly or not replying when one’s friends “are there” is considered arrogant and indifferent:

You see if people have read or not, and then people may think it’s very arrogant if you do not answer directly, if they ask a question. But I’ll answer as quickly as possible, but then there may be pressure that you need to be connected and, yes, always be able to answer. (David)

You want to get a response, so I usually answer … yes, because it’s not fun if you send something and you do not get a response when you know that seven girls are watching their mobiles so that … it’s a bit like a job, so now I have answered. (Ebba)

The intervening, ordering, and binding character of the online presence of absent friends is also made manifest through mediated contacts that cannot be postponed (or time-shifted; Wajcman Citation2015) for even a short period. In essence, this means that one must be there when something happens or the moment is lost. A clear example of this is the increasingly prevalent group conversations characterized by extended and semiconcentrated sequences of coattentiveness (Ling Citation2017; Thulin Citation2018). These sequences have a pacesetting capacity and can trigger rhythms of waiting and delay. The corollary is that quite short periods of inattention can result in trouble catching up later, as the content of the conversation or thread (i.e., what has been said and decided on) is lost. In our study, we find many examples of this binding in time:

This morning when I went to school, there was a group chat that started … then I saw it a bit late, and so I had to open up/log in and catch up on reading, then you get a little stressed, get frustrated because you do not, like, get it. (Oscar)

Furthermore, promises of meeting or being available to absent friends can be considered equally important and constraining, similar to joining in face-to-face get-togethers, including similar reactions to “missing out” or “not showing up.” For example, Emma described what happened when she fell asleep very early in the evening, without saying “goodnight” to her friends online:

Yes, but for example, this evening, at half past eight, I was very tired. I thought I’d just take a short power nap … so you always write to your friends to say good night, now I’m going to bed, or good morning, now I’m getting up. So you are constantly updating each other. And at eight o’clock I fell asleep and slept to four this morning, and then I was kind of panicking when I woke up … so I could have slept two more hours because I was getting up at six … but then I really felt … I had to [get up] because I checked the mobile and saw that I had received a lot. So no, I had to see what she wrote and I had to see what he was sending. And then I went in, or took the phone, and then I responded to all the snaps, and sent new snaps to everyone, and responded to all the SMSs. (Emma)

Our case study also illustrated how much attention and effort are devoted to informing one another in advance about not being present online or “disappearing” for a while, meaning that answers might be delayed when one is away, and also to saying “goodnight” and “good morning.” Similarly, valid excuses are given for online absences; for example, that one has to study, it is family dinner time, a lesson is going on, or one is at the theater and mobiles must be turned off.

Possibly, but then you have an explanation … but I needed to sleep or I had to study as well, and you cannot argue with it. I do not think so. (Anton)

But I usually say in advance, I will be studying, so maybe I will respond more slowly or later. And it usually seems to work, telling [them] in advance. (Moa)

These examples illustrate our argument that today’s mobile social contact can no longer be regarded as a form of illusive background awareness. Rather, it includes bundles of individual coattentiveness and copresence and is often perceived as just as “real” (or “there”) as nonmediated forms of social interaction. This stream of bundles orders and reorders not only everyday patterns of social activity but the use of time and the experience of place. This intervening background needs further consideration.

The Active and Intervening “Background”

Local and Mediated Pockets of Order

If mediated copresence has recoupling effects on young individuals’ daily lives, then it is vital to develop an understanding of how online mediation interacts with and influences their time use and activities more generally. This is because recoupling online social contact not only changes an individual’s foreground activity and attention but is increasingly taking place in the background setting of daily life. Being in the background does not necessarily mean that the online is subordinate in terms of attentiveness but that it is largely performed in parallel to the various foreground activities that constitute an individual’s sequences of activities that demand more or less cognitive effort and commitment. From a time-geographic perspective, this dual pattern of foreground and background activity could be portrayed as an unbroken sequence of foreground activities performed by a person in different locations combined with a digital background including bundles of mediated copresence performed in parallel.

This understanding underlines the common observation that modern ICTs increase the importance of simultaneity in organizing time use and daily activity, often alluded to in concepts such as multitasking, time-deepening, intensification, and acceleration (e.g., Robinson and Godbey Citation1997; Urry Citation2000; Wellman Citation2001; Kenyon and Lyons Citation2007; Schwanen and Kwan Citation2008; Wajcman Citation2015). This simultaneity is found, for example, when media use (e.g., listening to music) goes on passively in the background while people actively engage in foreground activities or when mobile communications (e.g., phone calls and SMSs) are time-shifted to fill gaps in passive time use, natural pauses, or periods of “dead time” (e.g., travel time) in everyday life (Lyons and Urry Citation2005; Bittman, Brown, and Wajcman Citation2009).

With the rise of smartphones, the nature of the “background” has changed on many occasions. A background filled with mediated bundles of socializing is not only becoming more prevalent but is increasingly active and potentially intrusive in ongoing foreground activity compared with the time when mobile phones were predominantly used for texting and calling. Online social interaction is often not as easily time-shifted to empty moments or passive foreground activities but is potentially bound to almost any activity, time, and place. In this way, it often ends up reshuffling the stream of located activities and presences or the contexts in time geography called “pockets of local order” (Hägerstrand Citation1985; Lenntorp Citation2005). The pocket of local order concept refers to the fact that fulfilling the projects of daily life requires bounded time–space contexts ensuring closeness to necessary persons, objects, other artifacts, and domains in which the projects can be ordered purposefully. These pockets also require the creation of more or less porous boundaries or domain walls that shield individuals or groups of people from the outside world and ensuring the absence of unwanted influences and disturbances that otherwise threaten the realization of activities. This local anchoring, arrangement, and shielding of activity performance is often and increasingly challenged by the always-on streams of online background activity. Arguably, pockets of order are becoming redefined and reordered in several ways. One crucial way is that mobile media have made such domain walls more permeable to outside influences. Bundles of online presences are always “there,” potentially interfering with attentiveness and time for other activities. Also important is that these “ordering pockets” are not only corporeally constituted in physical proximity but are increasingly established online as well. Young individuals’ online social projects increasingly rely on mediated pockets of local order with their own inherent rhythms and logics (as discussed in the previous section). They represent different threads of interaction, often going on in parallel, sometimes connected but at other times divergent and competing for attention. Principally, this transformation increases tensions in everyday life, in which contexts and orders collide, activities are delayed, and projects wrecked. Not least, in young people’s everyday lives, the multiple and parallel streams of colocated and mediated presences potentially make pockets of order more unruly and ordering more difficult to establish. How these practices are developed, experienced, and negotiated in everyday life merits further consideration.

The Reordering of Colocated and Mediated Presences: Dominant Processes

Principally, the active and intervening background of mediated presence can redefine activity boundaries and alter existing pockets of local and mediated order. At the same time, it is important to recognize that the influence of new technologies on people’s lives is rarely clear-cut but mutually constitutive, complex, and divergent. We currently lack knowledge of how individuals in practice juggle and experience the multiple and parallel colocated and mediated presences in everyday life. Reflecting on the emerging literature and our interviews, we suggest three dominant processes of reordering occurring among young people in countries such as Sweden, including processes of interwoven presence, ambivalence and congestion, and colocated absence.

Interwoven Presence.

A first characteristic process is the harmonious interweaving of located and mediated presences and rhythms as deeply integrated in social activity. Pockets of socializing are largely constituted by high permeability and intertwined presences and contexts. This underlines the importance of not starting from a binary either–or understanding of online or offline contexts (as argued by, e.g., Kinsley Citation2014; Grabher et al. Citation2018). Online and offline presences are to be viewed as mutually conditioning and characterized by increased simultaneity and amalgamation. This is supported by the recurrent suggestion within Internet research that the online and offline, the physical and virtual, should not be considered separate realms but are so closely interwoven that they cannot really be separated (e.g., Valentine and Holloway Citation2002; Nunes de Almeida and Delicado Citation2015). Obviously, this observation becomes more pointed in the era of smart mobile media, and our case study provides many indicative examples of the intertwining of online and offline presences. The mediated presences of absent friends are included as normal parts of face-to-face get-togethers (e.g., through images and comments shown on the mobile), and face-to-face gatherings and situations are continuously posted to absent friends online, in a never-ending loop of mediated and colocated sharing:

Yes, sometimes you only sit with your mobile and “hang out” even when you meet at someone’s place, check different things on Facebook, and talk to each other about it. Everyone has his smartphone, like that, and then you show people, and check here. (Philip)

These continuous online exchanges also spill over to face-to-face socializing; for example, when one already “knows everything there is to know” about each other’s days and weeks when meeting up offline:

Then it seems that you were there yesterday—well, how was the cinema—then you know from Snapchat that she was at the cinema, and then you talk about it when you see each other … and so, having conversation topics on social media really contributes to a lot of conversation topics … and I think that is still quite important … then you get to know each other a little better, kind of, yes … and on social media, I have records of everything—the kind of humor I have, or something like that—and then you get confirmed in another way. (Gustaf)

The online and offline contexts are also intertwined when doing schoolwork together while in separate locations, asking questions and helping each other out in messenger groups. Overall, these examples illustrate how mediated and colocated presences can be tightly intertwined elements of social activity and, importantly, not perceived as parallel or separate streams always competing for attention.

Lingering Ambivalence and Intensified Congestion.

The conception of interweaving and smoothly integrating the online and offline realms, however, is accompanied by another process characteristic of young people’s everyday activity patterns and time use. This process involves the concurrently ongoing and partly conflicting orders of mediated and located contexts and of unruliness and mutual intrusion. Current research suggests the existence of a perpetual and unresolved clash between connected togetherness and the inherent constraints and pressure of online social contact (Hall and Baym Citation2011; Hoffner, Sangmi, and Park Citation2016) that can generate a state of ambivalence (Lagerkvist Citation2014, Citation2015). This indicates that the streams of foreground activity, on one hand, and the digital background, on the other, each embody a juggling of multiple and discrete copresences and pockets of order, including different (matching/clashing) expectations, norms, rhythms, and constraints on attentiveness. This points to the occurrence of congestion, in which mediated presences hamper, delay, or threaten the socially competent conduct of activities. This can occur in particular for nonelastic activities that are subject to considerable space–time constraints and demand significant cognitive commitment of the individuals involved, as with schoolwork and lecture (Janco and Cotton Citation2012; Judd Citation2013).

Young individuals handle such congestion by developing various strategies of refining their online social contacts, fitting them more smoothly into their everyday routines (e.g., using smartphone apps that enable visual conversation to speed up exchange) or disciplining the mediated presence of absent friends through boundary formation. Such strategies are rarely clear-cut but include constant and complex decision processes also taking social status and hierarchy (as regards who, what, and by what channel) into consideration when determining, for example, whether things are “let through/responded to” or time-shifted to a later point (Bittman, Brown, and Wajcman Citation2009; Wajcman Citation2015):

Mmm … for me, I feel like I’d like to know what it says … and I get a message, so it’s very hard to just let it be, but I’d like to know what the person wants … but to answer, no, if it’s not important then I can let it be. But then I think that the person can wait a bit, because what I’m doing now is more important. Oh, so I can still set the phone aside … but I’d like to know what the message is first. (Sofi)

Our limited study found that these are commonly perceived to be well-functioning strategies in an everyday context. On the other hand, they come with an underlying ambivalence and disharmony, expressed by constant “micro decision making” and negotiation. Several examples illustrate the continuous deliberation of presence versus absence as accompanied with uncertainty and unease:

I might have received such a long SMS from a friend and I can’t reply right away, then there will be a lot of question marks. And then if you sit and study and put on “do not disturb,” not to receive any notices or hear it [i.e., the message alert], it usually helps. But then you come back to the phone later and see that there are lots of question marks and so on. It’s stressful because I do not want to be the one who is ignoring, or have them feel that I am. (Emily)

The Colocated Absence.

A third suggested tendency concerns how extensive mediated copresences reinforce a sense of absence in the ordered pockets of everyday life because connectivity to distant places trumps corporeal proximity. People feel absent when being together; for example, when together in the same room with someone but mostly being attentive to mediated people in other places (Zhao and Elesh Citation2008; Park Citation2013). This can be highly intentional, for example, when seeking distance from people in public places or not wanting to talk on the bus during morning hours (a frequent example cited in our case study). Park (Citation2013) described how mere engagement with digital devices serves as an “involvement shield,” creating a private cocoon enabling privacy and detachment.

Personal distance and absence are also created unintentionally, however, as an undesirable side effect of the couplings and constraints of mediated copresence. Experiences of colocated friends being cognitively absent because of their mobiles are very frequent and described in terms of, for example, people who stop listening, slow and detached answers, and “meetings” continually filled with silence:

One of my friends does this when we’re alone, when we hang out, she sits there with her mobile, and then I realize how hard it feels for me when I talk and she’s looking down at her mobile … she’s listening and she answers, but sometimes it will be, like, me talking, she doesn’t talk when she’s sitting with it [i.e., the phone], so we go on in silence. (Amanda)

This illustrates how online and offline contexts sometimes collide and compete for attention. It suggests that face-to-face conversations are also increasingly included in the semisynchronous discourse of social interaction, not receiving full concentration and containing periods of waiting and inattention.

Conclusion

Social and media research on young people and mobile media has framed mobile phones in general and smartphones in particular as social mediation technologies (Ling Citation2012) that enable people to restructure their daily use of time and space (e.g., Ling Citation2004, Citation2012; Bakardjieva Citation2005; Ling and Campbell Citation2009; Haddon Citation2011). By emphasizing individual user agency, this research has achieved important insights into the adoption and incorporation of mobile phone use, the realization and justification of individual access, and how smartphone use has become ubiquitous, taken for granted, and socially embedded across most of the Global North.

This article contributes to the wider literature by turning attention to how the collective acceptance and many peoples’ use of smart mobile devices impose new logics and constraints on daily life, potentially reordering the use of time, space, and place, among adolescents and young adults in particular. Importantly, in just a few recent years, the conditions for such a transformative reordering have been set in place. Although previous research examined nonsmartphone technology, dominated by intermittent person-to-person calling and texting, the widespread dissemination of smartphones has made online social interaction into an incessant background to people’s daily lives. The growing, often unintended, implications of these conjoint processes of collective acceptance and perpetual online background presence have so far been inadequately studied and theorized.

Conceptually, our article addresses this lack by examining the digitalization of human spatial practices through the lens of time-geographic theory. By reworking classical conceptions of bundles, coupling constraints, rhythms, and pockets of local order for the era of mobile digital media, we improve understanding of the virtualities of young people’s social lives and examine upcoming new constraints on user agency and the reorganizing of daily practice and bundling. Against a mainstream discourse emphasizing decoupling, flexibility, and anywhere, anytime social contact mediated by smartphone technology, we discern and suggest certain contrasting themes of profound change that reinforce the locking in and linking of activities in everyday life.

A first theme concerns the collective production of new time–space constraints and the recoupling of social interaction. Mediated bundles of sociality are becoming more frequent, insistent, and locked in time. This partly has to do with the changing rhythm and pace of online social interaction, which are produced by entanglements of individual intentions, online social projects, and smartphone apps designed for immediacy and responsiveness (e.g., enabling visual dialogues, instant sharing of context, live group interactions, easy and quick confirmations, and more).

A second theme concerns the transforming of relationships between individuals’ foreground activities and online social activities going on in the background. This is not only a question of online contacts reordering the located stream of foreground activities making up daily life. Social mediation technologies, such as smartphones and tablets, also change the role and meaning of the online background, which is becoming more active, intervening in and intruding on ongoing foreground activity. The active yet constrained users of this technology more or less successfully juggle and negotiate multiple colocated and mediated presences. Arguably, this profound transformation of daily activity is captured by the dominant processes of interweaving, ambivalence, and congestion, as well as increased colocated cognitive absence.

Our observations are partly based on a study among middle-class adolescents in a major Swedish city whose daily lives are dominated by extensive smartphone usage. Given the fast spread of smart mobile media, it is reasonable to believe that cooccurring tendencies are increasingly found in other segments of the population as well. Our conclusions serve to inform future geographical research into the relationships among ICTs and social change. Framing our discussion in time-geographic terms, we highlight the importance of theoretically developing such a digital geography. As discussed by Ash, Kitchin, and Leszcynski (Citation2018), much of that effort has so far echoed developments in other disciplines or produced debates about epistemology and methods, rather than considering how the digital inflects geography and human spatial practice.

Notes

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Eva Thulin

EVA THULIN is Associate Professor of Human Geography at the University of Gothenburg, SE 405 30 Gothenburg, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected]. Her research interests include time-geography, digitalization, and how the ubiquitous presence of digital spheres restructures people’s everyday lives, their sociality, and uses of time and place. Research topics include the leisure-time shifts and relocations occurring in the Swedish population due to digitalization; the recoupling of online sociality and the mounting binds and constraints associated with massive use of mobile media; and the implications of mobile ICTs on the boundaries of work and family life.

Bertil Vilhelmson

BERTIL VILHELMSON is Professor of Human Geography at the University of Gothenburg, SE 405 30 Gothenburg, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests concern human spatial mobility (virtual and corporeal) and its integration with people’s activity patterns, their use of time and place, and well-being. Recent research highlights include generational and gendered changes in daily travel, ongoing shifts in teleworking, and how the increased time spent on the Internet affects daily life in terms of time, space, and sociality. Ongoing projects also concern the role of proximity and slow modes of transport in promoting sustainable accessibility in urban areas.

Tim Schwanen

TIM SCHWANEN is Associate Professor of Transport Studies and Director of the Transport Studies Unit in the School of Geography and Environment at the University of Oxford, Oxford, OX1 3QY, UK. E-mail: [email protected]. From July 2016 to June 2019 he was also Visiting Professor of Human Geography at the School of Business, Economics and Law of the University of Gothenburg. His research interests include the everyday mobilities of people, goods, and information; just transitions toward low-carbon mobility and living; urban transformations triggered by technological change; and the geographies of well-being.

Notes

1 We refer to two qualitative studies of the daily mobile phone and computer use of high school students. The studies were performed in the same school and classes in Gothenburg, Sweden, the first in 2000 (reported in Thulin and Vilhelmson Citation2007, Citation2009) and the second in 2016 (Thulin Citation2018; Thulin and Vilhelmson Citation2019a).

2 Mediated copresence is here understood as interpersonal contact and companionship experienced through the use of technologies (old or new, stationary or mobile); for example, the telephone, computer, and smartphone. It denotes the notion that the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of individuals are influenced by the actual, imagined, and implied presence of others.

3 This article deliberately concentrates on online social interaction, as social media are ingrained in everyday life and dominate young people’s attachment to and use of smartphones (Bertel and Ling Citation2013; Thulin Citation2018; Vanden Abeele, De Wolf, and Ling Citation2018). Even so, a wide range of other online activities—gaming, entertainment, films, information searches, school work, shopping, and so on—also make up their daily mobile media diet. Such uses could play important roles and have effects in quite different ways, even discouraging outgoingness and social interaction among friends, as found in studies from the era before smartphones (Mannell, Kaczynski, and Aronson Citation2005; Shen and Williams Citation2011; Thulin and Vilhelmson Citation2019b).

4 For a detailed description of this qualitative study, see Thulin (Citation2018) and Thulin and Vilhelmson (Citation2019a, Citation2019b).

References

- Adams, P. C. 2000. Application of a CAD-based accessibility model. In Information, place and cyberspace: Issues in accessiblity, ed. D. Janelle and D. Hodge, 217–39. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer.

- Adams, P. C. 2005. The boundless self: Communication in physical and virtual spaces. New York: Syracuse University Press.

- Aguiléra, A., C. Gulliot, and A. Rallet. 2012. Mobile ICTs and physical mobility: Review and research agenda. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 46:664–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2012.01.005.

- Ash, J., R. Kitchin, and A. Leszczynski. 2018. Digital turn, digital geographies? Progress in Human Geography 42 (1):25–43. doi: 10.1177/0309132516664800.

- Bakardjieva, M. 2005. Internet society: The Internet in everyday life. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Bayer, J. B., N. B. Ellison, S. Y. Schoenebeck, and E. B. Falk. 2016. Sharing the small moments: Ephemeral social interaction on Snapchat. Information, Communication & Society 19 (7):956–77. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2015.1084349.

- Bertel, T. F., and R. Ling. 2016. “It’s just not that exciting anymore”: The changing centrality of SMS in the everyday lives of young Danes. New Media & Society 18 (7):1293–1309. doi: 10.1177/1461444814555267.

- Bertel, T. F., and G. Stald. 2013. From SMS to SNS: The use of the internet on the mobile phone among young Danes. In Mobile media practices, presence and politics: The challenge of being seamlessly mobile, ed. K. Cumiskey and L. Hjorth, 198–213. London and New York: Routledge.

- Bittman, N., J. E. Brown, and J. Wajcman. 2009. The mobile phone, perpetual contact and time pressure. Work, Employment and Society 23 (4):637–91.

- Boy, J. D., and J. Uitermark. 2017. Reassembling the city through Instagram. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 42 (4):612–24. doi: 10.1111/tran.12185.

- Carolus, A., J. F. Binder, R. Muench, C. Schmidt, F. Schneider, and S. L. Buglass. 2018. Smartphones as digital companions: Characterizing the relationship between users and their phones. New Media & Society 21 (4):914–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818817074.

- Coletta, C., and R. Kitchin 2017. Algorhythmic governance: Regulating the “heartbeat” of a city using the Internet of things. Big Data & Society 4:1–16.

- Cope, M., and B. Y. H. Lee. 2016. Mobility, communication, and place: Navigating the landscapes of suburban U.S. teens. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 106 (2):311–20.

- Couclelis, H. 2004. Pizza over the Internet: E-commerce, the fragmentation of activity and the tyranny of the region. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 16 (1):41–54. doi: 10.1080/0898562042000205027.

- Couclelis, H. 2009. Rethinking time geography in the information age. Environment and Planning A 41 (7): 1556–75.

- Couldry, N. 2008. Actor network theory and media: Do they connect and on what terms? In Connectivity, networks and flows: Conceptualizing contemporary communications, ed. A. Hepp, F. Krotz, S. Moores, and C. Winter, 93–110. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton.

- Crang, M., T. Crosbie, and S. Graham. 2006. Variable geometries of connection: Urban digital divides and the uses of information technology. Urban Studies 43 (13):2551–70. doi: 10.1080/00420980600970664.

- Edensor, T., and J. Holloway. 2008. Rhythmanalysing the coach tour: The ring of Kerry, Ireland. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 33 (4):483–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-5661.2008.00318.x.

- Ellegård, K. 2000. A time-geographical approach to the study of everyday life of individuals: A challenge of complexity. GeoJournal 48 (3):167–75.

- Ellegård, K. 2019. Thinking time geography: Concepts, methods and applications. London and New York: Routledge.

- Giddens, A. 1991. Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Gilbert, M. 2010. Theorizing digital and urban inequalities. Critical geographies of “race”, gender and technological capital. Information, Communication & Society 13 (7):1000–18. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2010.499954.

- Goffman, E. 1963. Behavior in public places. New York: Free Press.

- Grabher, G., A. Melchior, B. Schiemer, E. Schüßler, and J. Sydow. 2018. From being there to being aware: Confronting geographical and sociological imaginations of copresence. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 50 (1):245–55. doi: 10.1177/0308518X17743507.

- Graham, M., B. Hogan, B. R. K. Straumann, and A. Medhat. 2014. Uneven geographies of user-generated information: Patterns of increasing informational poverty. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 104 (4):746–64. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2014.910087.

- Graham, S. 2013. Geographies of surveillant simulation. In Virtual geographies: Bodies, space and relations, ed. M. Crang, P. Crang, and J. May, 140–57. London and New York: Routledge.

- Haddon, L. 2011. Domestication analysis, objects of study, and the centrality of technologies in everyday life. Canadian Journal of Communication 36 (2):311–23.

- Haddon, L. 2016. The domestication of complex media repertoires. In The media and the mundane: Communication across media in everyday life, ed. K. Sandvik, A. M. Thorhauge, and B. Valtysson, 17–30. Göteborg, Sweden: Nordicom.

- Hägerstrand, T. 1970. What about people in regional science? Papers of the Regional Science Association 1 (24):7–21.

- Hägerstrand, T. 1982. Diorama, path and project. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 73 (6):323–39.

- Hägerstrand, T. 1985. Time-geography: Focus on the corporeality of man, society and environment. In The science and praxis of complexity, ed. S. Aida, 193–216. Tokyo: The United Nations University.

- Hall, J. A., and N. K. Baym. 2011. Calling and texting (too much): Mobile maintenance expectations, (over)dependence, entrapment, and friendship satisfaction. New Media & Society 14 (2):316–31. doi: 10.1177/1461444811415047.

- Haunstrup Christensen, T. 2009. Connected presence in distributed family life. New Media & Society 11 (3):433–51. doi: 10.1177/1461444808101620.

- Hoffner, A., L. Sangmi, and S. J. Park. 2016. “I miss my mobile phone!”: Self-expansion via mobile phone and responses to phone loss. New Media & Society 18 (11):2452–68. doi: 10.1177/1461444815592665.

- Hubers, C., M. Dijst, and T. Schwanen. 2008. ICT and temporal fragmentation of activities: An analytical framework and initial empirical findings. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 99 (5):528–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9663.2008.00490.x.

- Hunt, D. S., C. A. Lin, and D. J. Atkin. 2014. Communicating social relationships via the use of photo-messaging. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 58 (2):234–52. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2014.906430.

- Ito, M., and D. Okabe. 2005. Technosocial situations: Emergent structurings of mobile email use. In Personal, portable, pedestrian: Mobile phones in Japanese life, ed. M. Ito, D. Okabe, and M. Matsuda, 257–74. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Janco, R. A., and S. R. Cotton. 2012. No A 4 U: The relationship between multitasking and academic performance. Computers & Education 59:505–14.

- Janelle, D. G. 1973. Measuring human extensibility in a shrinking world. Journal of Geography 72 (5):8–15. doi: 10.1080/00221347308981301.

- Johnsen, T. 2003. The social context of the mobile phone use of Norwegian teens. In Mediating the human body: Technology, communication and fashion, ed. L. Fortunati, J. E. Katz, and R. Riccini, 161–70. London: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Judd, T. 2013. Making sense of multitasking: Key behaviours. Computers & Education 63:358–67. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2012.12.017.

- Kasesniemi, E.-L., and P. Rautiainen. 2004. Mobile culture of children and teenagers in Finland. In Perpetual contact: Mobile communication, private talk, public performance, ed. J. E. Katz and M. Aakhus, 170–84. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Katz, J. E., and E. T. Crocker. 2015. Selfies and photo messaging as visual conversation: Reports from the United States, United Kingdom and China. International Journal of Communication 9:1861–72.

- Kenyon, S., and G. Lyons. 2007. Introducing multitasking to the study of travel and ICT: Examining its extent and assessing its potential importance. Transportation Research Part A 41:161–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2006.02.004.

- Kinsley, S. 2014. The matter of “virtual” geographies. Progress in Human Geography 38 (3):364–84. doi: 10.1177/0309132513506270.

- Krantz, H. 2006. Household routines—A time–space issue: A theoretical approach applied on the case of water and sanitation. Applied Geography 26 (3–4):227–41. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2006.09.005.

- Kuss, D. J., and O. Lopez-Fernandez. 2016. Internet addiction and problematic Internet use: A systematic review of clinical research. World Journal of Psychiatry 6 (1):143–76. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v6.i1.143.

- Kwan, M.-P. 2002. Time, information technologies, and the geographies of everyday life. Urban Geography 23 (5):471–82. doi: 10.2747/0272-3638.23.5.471.

- Kwan, M.-P. 2016. Algorithmic geographies: Big data, algorithmic uncertainty, and the production of geographic knowledge. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 106 (2):274–82.

- Lagerkvist, A. 2014. A quest for communitas: Rethinking mediated memory existentially. Nordicom Review 35:205–18.

- Lagerkvist, A. 2015. The netlore of the infinite: Death (and beyond) in the digital memory ecology. New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia 21 (1–2):185–95. doi: 10.1080/13614568.2014.983563.

- Larsen, J., K. W. Axhausen, and J. Urry. 2006. Geographies of social networks: Meetings, travel and communication amongst youngish people. Mobilities 1 (2):261–83. doi: 10.1080/17450100600726654.

- Lefebvre, H. 2004. Rhythmanalysis: Space, time and everyday life. London: Continuum.

- Lenntorp, B. 2005. Path, prism, project, pocket of local order: An introduction, 2004. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 86 (4):223–26. doi: 10.1111/j.0435-3684.2004.00164.x.

- Licoppe, C. 2004. Connected presence: The emergence of a new repertoire for managing social relationships in a changing communications technoscape. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 22 (1):135–56. doi: 10.1068/d323t.

- Ling, R. 2004. The mobile connection. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann.

- Ling, R. 2012. Taken for grantedness: The embedding of mobile communication into society. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Ling, R. 2017. The social dynamics of mobile group messaging. Annals of the International Communication Association 41 (3–4):242–49. doi: 10.1080/23808985.2017.1374199.

- Ling, R., and S. W. Campbell, eds. 2009. The reconstruction of space and time: Mobile communications practices. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

- Ling, R., and C.-H. Lai. 2016. Microcoordination 2.0: Social coordination in the age of smartphones and messaging apps. Journal of Communication 66 (5):834–56. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12251.

- Ling, R., and B. Yttri. 2002. Hyper-coordination via mobile phones in Norway. In Perpetual contact: Mobile communication, private talk, public performance, ed. J. E. Katz and M. Aakhus, 139–69. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Ling, R. and B. Yttri. 2006. Control, emancipation, and status. The mobile telephone in teens’ parental and peer relationships. In Computers, phones, and the Internet. Domesticating information technology, ed. R. Kraut, M. Brynin, and S. Kiesler, 219–34. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Litt, E., and E. Hargittai. 2016. The imagined audience on social network sites. Social Media + Society 2 (1):1–12.

- Lyons, G., and J. Urry. 2005. Travel time use in the information age. Transportation Research Part A 39:257–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2004.09.004.

- Mannell, R. C., A. T. Kaczynski, and R. M. Aronson. 2005. Adolescent participation and flow in physically active leisure and electronic media activities: Testing the displacement hypothesis. Society and Leisure 28 (2):653–75. doi: 10.1080/07053436.2005.10707700.

- McBride, N. 2003. Actor–network theory and the adoption of mobile communications. Geography 88 (4):266–76.

- Mulıcek, O., R. Osman, and D. Seidenglanz. 2016. Time–space rhythms of the city—The industrial and postindustrial Brno. Environment and Planning A 48 (1):115–31.

- Nunes de Almeida, A., and A. Delicado. 2015. Internet, children and space: Revisiting generational attributes and boundaries. New Media & Society 17:1436–53. doi: 10.1177/1461444814528293.

- Oksman, V., and J. Turtiainen. 2004. Mobile communication as a social stage: Meanings of mobile communication in everyday life among teenagers in Finland. New Media & Society 6 (3):319–39. doi: 10.1177/1461444804042518.

- Park, Y. J. 2013. Offline status, online status: Reproduction of social categories in personal information skill and knowledge. Social Science Computer Review 31 (6):680–702. doi: 10.1177/0894439313485202.

- Parkes, D., and N. Thrift. 1980. Times, spaces and places: A chronogeographic perspective. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

- Rettie, R. 2009. SMS: Exploiting the interactional characteristics of near-synchrony. Information, Communication & Society 12 (8):1131–48. doi: 10.1080/13691180902786943.

- Robards, B., and S. Lincoln. 2017. Uncovering longitudinal life narratives: Scrolling back on Facebook. Qualitative Research 17 (6):715–30. doi: 10.1177/1468794117700707.

- Robinson, J., and G. Godbey. 1997. Time for life: The surprising ways Americans use their time. University Park, PA: Penn State Press.