Abstract

Between 1930 and 1932 the three sessions of the Round Table Conference in London drew more than seventy Indian delegates to the city, for up to three months, to debate India’s constitutional future within the British Empire. This article argues that the atmosphere of the conference was central to its successes and failures and that studying atmospheres can help us think about the co-constitution of place, bodies, and politics more broadly. It approaches atmospheres from three interrelated perspectives. First, the atmospheric environment of the conference is set, in terms of both the physical geography of the weather and the human geography of the conference venue. Second, it traces conference bodies, which endured the weather, used it as metaphor, and attuned their politics to the affective atmosphere. The article concludes with reflections on representing non-representational atmospheres. It argues that the current atmospheres literature is oddly deraced, while debates about weather and bodies’ reactions to social and political atmospheres are inherently and always racialized. Analyzing the reactions of and to diverse Indian delegates in 1930s London gives us insights into an interwar colonial geographical imagination and demonstrates the potential for thinking about meteorological and affective atmospheres together. Key Words: atmospheres, conferences, imperialism, India, race.

1930 年到 1932 年间,在伦敦举办的圆桌会议的三大场次,吸引了超过七十位印度代表造访该城最长达三个月,辩论印度在大英帝国中的宪法未来。本文主张,该会议的氛围是其成败的核心,而研究氛围能够协助我们更为广泛地思考有关地方、身体与政治的共同建构。本文通过三大相关视角处理氛围。首先,本文确定该会议在气候的自然地理和会场的人文地理上的氛围环境。第二,本文追溯会议中承受气候的身体,并以此作为隐喻,将其政治与情感氛围调和。本文于结论中,反思呈现非再现的氛围。本文主张,当前的氛围文献,出乎意料地去种族化,而有关天气与身体对社会和政治氛围的反应之辩论,却在本质上永远是种族化的。分析伦敦 1930 年代各印度代表的反应及其所得到的反应,提供我们有关两次世界大战之间殖民地理想像的洞见,并证实共同思考有关气象学和情感氛围的潜力。关键词:氛围,会议,帝国主义,印度,种族。

Entre 1930 y 1932 las tres sesiones de la Conferencia de la Mesa Redonda en Londres atrajeron más de setenta delegados indios a la ciudad, durante tres meses, para debatir el futuro constitucional de la India dentro del Imperio Británico. Este artículo sostiene que la atmósfera de la conferencia era crucial para sus éxitos y fracasos, y que estudiando las atmósferas puede ayudarnos a pensar acerca de la co-constitución de lugar, los cuerpos y las políticas con mayor amplitud. Las atmósferas se pueden abordar desde perspectivas interrelacionadas. Primera, el entorno de la conferencia es determinado, tanto en términos de la geografía física del tiempo atmosférico como de la geografía humana del recinto de la conferencia. Segunda, aquella disposición traza los cuerpos de la conferencia, que aguantaron el tiempo, lo usaron como metáfora y afinaron sus políticas a tono con la atmósfera afectiva. El artículo concluye con reflexiones sobre cómo representar las atmósferas no-representacionales. Se arguye que la literatura actual relacionada con las atmósferas es curiosamente desligada de la raza, en tanto que los debates acerca de las reacciones del tiempo atmosférico y los cuerpos a las atmósferas sociales y políticas son inherente y continuamente racializados. Analizando las reacciones de los diversos delegados indios en el Londres de los años 1930 nos permite ganar perspectivas hacia una imaginación geográfica colonial del período de entreguerras y demuestra el potencial para pensar conjuntamente de las atmósferas meteorológicas y afectivas. Palabras clave: atmósferas, conferencias, imperialismo, India, raza.

While only one speaker in the [parliamentary] debate on the India Office estimates thought it necessary to warn India … that it might be necessary to postpone consideration of an advance until “an atmosphere of calmer commonsense, good faith and goodwill returned,” two or three others referred to the need for a favourable atmosphere in which to follow up the work of the Round Table Conference. Nobody said how the political atmosphere could be improved.1

In November 1930, the first session of the India Round Table Conference (RTC) took place in London, at which the next stage of India’s constitutional development within the British Empire was debated. Although many radical anticolonialists were calling for Purna Swaraj (complete self-rule and independence), the majority of invited delegates were liberal and came to negotiate enhanced devolution and democratization. An outcome that the British failed to anticipate was that representatives of those states that were administered directly (British India) and indirectly (Indian or “Princely” States) agreed to form an Indian Federation, although this would not come to pass until after Indian independence in 1947. Accompanying independence was the partitioning of India, a result of rival Hindu–Muslim geographical imaginations of communities and territories, the tensions between which stymied negotiations at the second sitting of the RTC in 1931. This led many of the followers of the Indian National Congress, the leading nationalist party, to reject the conclusions of the final sitting of the RTC in 1932.

The conference is both central to histories of interwar India and forgotten. When it is recalled, it is remembered as a failure: MK (Mahatma) Gandhi attended the second session and failed to reconcile Hindu–Muslim demands; the plans for federation allowed increasingly doubtful princes to withhold from the proposed unitary state, and the British retained many of their autocratic powers. Yet the resulting constitution, crystallized in the Government of India Act (1935), laid the foundation for India’s independent constitution of 1950, and the conference itself crafted the biographies and policies of leading Indian politicians of the generation. Little is known regarding the experiences of the more than 100 delegates during their prolonged stays in London (ten weeks in 1930, twelve weeks in 1931, six weeks in 1932). The RTC has gone unremarked on within geography, as have the majority of international political conferences. Although studies of geopolitics and the geography of international relations abound, few of them have focused on the meeting spaces in which international and national fates were debated or on the ingredients that went into making such conferences work.

In this article I would like to engage with the substantial body of research that has emerged within and beyond geography in the last ten years regarding “atmospheres” (McCormack Citation2018; Sumartojo and Pink Citation2018) to suggest that the atmospheres of conferences are vital to their effectiveness. This, in part, draws on the interwar vocabulary with which the RTC was described. As the prologue suggests, “political atmospherics” were common parlance at the time.2 Although this atmospheric vocabulary was specific (to English, to period, and to place), it vacillated between the climatic and affective in ways that resonate with theoretical debates today. Regarding a debate over estimates made by the British government (the India Office) regarding preparations for the second session of the RTC, a calm and good atmosphere was felt to be foundational to the conference, a precondition of it meeting again and something that was difficult if not impossible to improve directly.

Being a cultural and historical geography of atmospherics, this account is obviously dependent on conference reportage. It draws on official documents, private archives, memoirs, and, especially, press reports to detect conference atmospheres. Atmospheres will be approached here as preexisting the delegates, as experienced by them, and as objects of reflection, both with hindsight and at the time. This draws on a much broader body of atmospheric research. Much of this research has been led by the work of geographers fathoming the aerial expanses beyond the more familiar historiography of earth writing (geography).

Air Writing: Cutting the Atmosphere with a Knife

Conference Atmospheres

On 20 December 2017, I coorganized a workshop for conference organizers at the University of Nottingham.3 The representatives agreed that the most important thing was to get prospective clients into the venue. While relating a visit of an engaged couple looking into wedding venues, one of the representatives relived a moment when the couple entered an older part of the building, with attractive fittings and lighting. She recalled looking at the couple and seeing something in their eyes that meant that they “got” the venue. We all listened, enrapt at this reliving of a moment of what has been called “envelopment” (McCormack Citation2018); the moment when a place seeps into you and you feel yourself (and your future) seeping in to it. This, in turn, created an atmosphere in the workshop, which evaporated with the next point raised.

The recognition of the importance of such atmospherics to political meetings has not come easily, although an increasingly diverse body of research into political events is opening up the study of conferences as multisensory spaces of engagement. These have addressed the role of commemorations and domestic interiors to diplomatic congresses (Vick Citation2014), the role of places and bodies in diplomacy (Neumann Citation2008, Citation2013), and the theatrics of postcolonial sovereignty at the Bandung Conference of 1955 (Shimazu Citation2012, Citation2014; as Lee [Citation2010] put it, “Although a certain diplomatic complexity undergirded the meeting, the public atmosphere achieved at the conference evinced this sensibility of a new era in global history” [12]).

Within geography there is a growing body of work on the lived spaces of the conference. This includes work on scientific conferences, whether contemporary (on climate see Weisser Citation2014; Weisser and Müller-Mahn Citation2017) or historical (on empire and meteorology see Mahony Citation2016). In the era of decolonization the conference became a key site of both negotiation and cultural display (Craggs Citation2014; Hodder Citation2015), at which successful meetings required the affective “umph” (Craggs Citation2018, 52) of conference organizers. These are all elements of what Craggs and Mahony (Citation2014) termed the “geographies of the conference,” in their call for greater attention to the politics of knowledge, performance, and protest in such spaces. This article forms part of an ongoing response to this call, from the perspective of atmospheres.

Writing about air has proven difficult. Its very nature, for some, makes naming and classifying airs and atmospheres contradictory and futile (Ash and Anderson Citation2015; Sumartojo and Pink Citation2018). Partitioning air is as impossible as cutting it with a knife, yet we still try. The very thing that makes atmospheres analytically appealing is that which makes them difficult to represent. There is no consensus on this problem, but in what follows I approach this issue from three overlapping bodies of work. These emphasize conceptual, staged, and historical-racial approaches to the atmospheric.

Conceptualizing and Attuning to Atmospheres

Although the current debate over atmospheres within geography is situated within the frame of non-representational theory, atmospheres have a much longer and more varied history of conceptualization. The word itself derives from the Greek atmos (vapor) and sphaira (sphere), denoting since the seventeenth century the body of air in which life might survive (Gandy Citation2017). Only in the nineteenth century did the term bifurcate into its scientific usage (a layer of gas enveloping the planet) and its cultural interpretation (a mood of place, whether individual or collective).

Griffero (Citation2014) made it clear that, unlike much recent work in non-representational theory, earlier conceptualizations of atmosphere related it directly to climatic and meteorological atmosphere. Fogs denoted melancholy, confusion, and depression, whereas dawn represented hope against the anonymizing night. All of these atmospheres are inseparable from their place, urban twilights heralding different possibilities to those in rural life. Griffero (Citation2014) showed that, like landscapes, atmospheres braid culture and nature together in particular ways (also see McCormack Citation2008) and are likewise appraised through all of the senses (smells of home or of clinical malls, the vision of a daunting stage or welcoming light, a resonant hymn or song from one’s youth, the taste of a long forgotten dish or of a new cuisine, even the touch of a person, a material, or a downpour). Sumartojo (Citation2019) usefully referred to these processes as atmospheric “attunement.” Griffero (Citation2014) also related atmospheres to politics: to a perception of political threat or optimism; to the ceremonies enhancing the aura of sovereignty; and to the bolstering of social–symbolic relations (also see Closs Stephens et al. Citation2017). Atmospheres can also summon a sense of contingency, change, and future possibility, making people act unpredictably (as we shall see was suggested of the Indian princes in London).

Recent conceptual work in geography has attempted to hold on to the materiality of air, continuing the extension of material geographies beyond the terra (for comparable work on the sea, see Peters, Steinberg, and Stratford Citation2018). Even more so than with water, air forces us to move our methodologies beyond solidity when thinking about materiality, agency, and politics (Jackson and Fannin Citation2011). “Affective atmospheres” present just such a way of thinking about the interpersonal and embodied conditions that shape life, without determining it (Ash and Anderson Citation2015). Whereas existing work on affect has explored individual encounters between humans and nonhumans, atmospheres offer non-representational theories an approach to interpersonal life (which can retrospectively be cast as “collective”). One strand of the debates prompted by this move focuses on whether atmospheres can exist autonomously of collective or solitary individuals and the extent to which every body alters the atmosphere of which it must constitute a part (Bille, Bjerregaard, and Sørensen Citation2015; Anderson Citation2017; Gandy Citation2017). Another regards the wider ranging debate regarding non-representational theory’s reliance on representations of atmospheres (Edensor and Sumartojo Citation2015).

For the purpose of this article I would like to dwell on Anderson’s (Citation2017) attempt to think about how collective affects shape lives by giving sites or episodes a particular feel. Appreciating but moving beyond “structures of feeling” (taken from Raymond Williams) that press and limit the subject, Anderson (Citation2017) argued that collective, affective atmospheres encircle and envelop the individual. He focused on perhaps the core analytical and methodological challenge of atmospheric studies: causality. Given the ephemeral nature of atmospheres, how can one prove they have an effect? This is both a personal quandary (how can you prove that the smell of that bread made you feel that way?) and an academic one (what source could ever prove that an atmosphere had a direct effect on an individual or collective?). Anderson (Citation2017) suggested that causation need not imply a linear relationship between cause and effect nor a clear separation of cause from context. Rather, atmospheres as affective mediation might display what Connolly (Citation2011) called “emergent causality” (as cited in Anderson Citation2017, 156). This is an effect that is causal, rather than simply contextual or relational, but it is also emergent, in that its form is not fixed before it emerges and that it quickly infuses itself into that which it putatively causes. For Anderson (Citation2017), this helps us consider how “an atmosphere is at once an effect that emanates from a gathering, and a cause that may itself have some degree of agentic capacity” (156).

This is a very useful way of bridging cause–effect and subject–object, but this article departs from Anderson in two senses (drawing on Sumartojo and Pink’s work discussed later). First, Anderson reduced atmospheres to affect, neglecting meteorological physical geography as both conceptual origin of atmospheres and as a core component of atmospheric engagement. Second, human geography tends to feature more here as a location of encounter rather than material and affective environment. The second concern is addressed in the section on staging later, and the first has been in part addressed through work that attempts to combine attention to affective and climatic atmospheres.

McCormack (Citation2018) has defined atmospheres as “elemental spacetimes that are simultaneously affective and meteorological, whose force and variation can be felt, sometimes only barely, in bodies of different kinds” (4). Such atmospheres “envelop” bodies (whether human or not), putting them into a condition that is also a process, constituting those things within the atmosphere. This is a technical process (exposing bodies to outsides), an aesthetic process (producing allure and enchantment), and an ethico-political process (exposing some but not others to atmospheres). To study them requires an empiricism that is alive to vague and fleeting variations while not assuming that political atmospherics lack force or permanence: “At stake politically in accounts of atmosphere are the terms of the relations between different bodies, the infrastructures and devices that condition the atmospheres in which they move, and the capacities of those bodies to exercise some influence over these conditions” (McCormack Citation2018, 8).

McCormack (Citation2018, 12) used the balloon as a “lure for thinking” about the elemental force of atmospheric things, and I suggest later that conferences might act as similar lures. Before showing how McCormack’s early work informs the structure of this article, I explore some research that suggests that affective and meteorological atmospheres are just two components of a broader atmospheric repertoire.

Staging Atmospheres

Bille, Bjerregaard, and Sørensen (Citation2015) suggested that although atmospheres blur endless binaries (subject–object, individuals–collectives, nature–culture, etc.) they are often assumed to be authentic, as opposed to inauthentic, manipulated, and staged spaces. Drawing on the work of Böhme, they argued that this goes against the in-betweenness of atmospheres, suggesting rather that atmospheres can be staged although not determined, for aesthetic, artistic, utilitarian, or commercial purposes. Although they appreciated the work on affective atmospheres, for them it usually lacks vigorous analysis of geography and location, so they suggested a reemphasis on the material dimension of atmospheres. For them, atmosphere’s capacity to bridge the discursive and the non-representational should be promoted as much as their capacity to blur emotion and affect, or the personal and general.

In the same year as this intervention, Edensor and Sumartojo (Citation2015) made a comparable case for an emphasis on the agency of designing and staging atmospheres as a corrective to the affective turn. They, likewise, argued that atmospheres exceed the affective, having phenomenological and sensual elements and social, historical, and cultural contexts that demand a greater focus on individual cognition and motivation: “To reiterate, affects, sensations, materialities, emotions and meanings are all enrolled within the force-field of an atmosphere” (Edensor and Sumartojo Citation2015, 253). This allows, for them, a fuller examination of the way in which power and atmospheres operate through staged spaces such as fairgrounds, ceremonies, parades, football matches, rallies, and malls (on the use of “atmotechnics” in the policing of rallies see Wall [Citation2019]).

This perspective is also found in Sumartojo and Pink’s (Citation2018) Atmospheres and the Experiential World. This wide-ranging book is the result of long-standing collaborations with geographers and attempts to bring together the processual interpretations of geography and the ethnographic approach of anthropology (Sumartojo and Pink Citation2018). The aims of the book are threefold: to rethink the relationships between people, space, time, and events; to interrogate sensory and affective modes of engaging atmospheres; and to think about the possibilities of intervening into and designing atmospheres. This experiential and future-focused orientation sets this work against other more philosophically driven approaches, as does the wider ranging definition of atmosphere as a configuration of sensation, temporality, movement, memory, material and immaterial surroundings, and the meanings that people attach to places (Sumartojo and Pink Citation2018).

The emphasis here, as with McCormack, is on emergence and uncertainty and on sensory and affective atmosphere but with a heightened emphasis on environment, social and cultural factors, and specific configurations of places and temporalities (Sumartojo and Pink Citation2018). Such manifestations can serve political purposes, such as cohering people around monuments and rituals, but only in unpredictable ways.

We have a compatibility with Anderson and McCormack here, in terms of the political impacts of directed atmospheres. Yet, unlike McCormack, there is little sense of environment or weather as atmosphere, whereas, unlike Anderson, atmospheres are said to not have causative power, although they do participate in the making of the world (Sumartojo and Pink Citation2018). As with almost all of the examples so far, the emphasis here has also been on examples from the developed world, with an implicitly white atmospheric subject.

Transparently White Atmospheres?

The majority of the atmospheres literature focuses on a racially undifferentiated United States, Europe, and Australia, within which race is not deployed as an analytical category (on this tendency in affect research more broadly, see Tolia-Kelly Citation2006). In his work on balloons, McCormack (Citation2018) admitted as much, non-European traditions of sky lanterns being beyond his ambit. Where this literature does extend beyond the Global North/West (including Australia and New Zealand), there is the temptation to assume a more haptic, enveloping, South/East. Given the racialized geographical imaginations about both the places and bodies of the non-North/West and their epistemic legacies, how might we challenge the inherent whiteness of atmosphere? Moving beyond literature that explicitly brands itself as atmospheric and moving toward the period and focus of this article, there are various resources on which we might draw.

One approach would be to consider the tradition of environmental determinism through the lens of atmosphere (Semple Citation1933). That is, it was not just the heat or land that was presumed to determine culture and capacities but the atmosphere, both meteorological and lived. Such debilitating atmospheres were common assumptions regarding the tropics, creating languorous cultures (Arnold Citation2006). In a recent review of climate and colonialism, Mahony and Endfield (Citation2018) showed just how deeply imbricated ideas about climate and the colonial project were, from racially imperialist assumptions about climate superiority, to technological adaptations to climate by settlers and colonizers, to the scientific knowledge produced about new climates and atmospheres so as to discipline and defeat them (also see Mahony Citation2016).

To confine thinking about race and atmospherics to the (ex-)colonial world, however, would be to uphold another futile binary, that between the imperial core and the colonized periphery. The West was, of course, equally structured by notions of race, imperialism, and climate. These concerns could come together, such as when imperial hopes for air travel met violently with the elemental forces of the atmosphere (as archived in the mass British mourning over the crash in poor weather of Airship R101 in 1931; Mahony Citation2019).

It is also possible to find imperial traces in interpretations of British weather. London fogs were a result of physical geography (the river basin) and economic geography (industrial pollution) but also cultural geography (Nead Citation2017). They seeped into the popular imagination in the nineteenth century, as the great “pea soupers” or “London particulars” (Corton Citation2015). If India had a tropical mal-aria (bad air) then London’s mal-aria was industrial, bringing poor health but also the risk of ill health, accidents, crime, and abundant foggy metaphors of doom, unnaturalness, and collapse. Fog marks air at its most material, closely enveloping the body and restricting one’s ability to be in place (Martin Citation2011), but it can also be considered in this context to reach out to imperial space. For some, the smog-producing factories of London represented imperial production; for others, the unstoppable spread of fog mimicked the expansion of empire; and for others the image of London as the capital of an empire was inherently one of a mysterious, fog-bound metropolis (Alessandrini Citation2012).

A final example returns us to McCormack’s (Citation2008) early work on the 1897 attempt by a Swedish team to reach the North Pole in a hydrogen-filled balloon. This was a specifically imperial ambition, although one aiming north rather than south of Europe. In tracking the flight, McCormack attempted to blur the distinction between meteorological and affective atmosphere through tracing three elements of the journey of the balloon and its pilots: (1) meteorological space as a prepersonal field of affect; (2) the registering of the atmosphere by individual bodies; and (3) emotional reflections on that felt intensity after the event. Although some have criticized this seeming distinction between affect, feeling, and emotion (Bille, Bjerregaard, and Sørensen Citation2015), McCormack’s (Citation2008) intention was to track the passage from and between these three analytical cuts. Borrowing liberally from this framing, the remainder of this article does not track a moving object but instead tracks delegates through the archives of 1930s London, seeking evidence of the emergent causality of meteorological and affective atmospheres at the RTC. First, it explores the atmospheric environments the delegates faced, in terms of weather and conference setting. Second, it registers atmospheres on conference bodies, which endured the weather, used it as metaphor, and attuned their politics to the affective atmosphere.4 Finally, it considers reflections upon the possibility, or not, of representing atmosphere. Unlike standard postcolonial studies of white men and women experiencing foreign atmospheres, this study places the experiences of traveling Indians center stage, during two remarkably miserable London autumns.

Atmospheric Environments

The Weather

Weather and climate are relational, as the following accounts attest, but we can also gauge them against relatively objective meteorological records. In The England and Wales Precipitation Index (beginning in 1766 and continuing to the present day), the year 1930 ranks at 206th out of 253 for rainfall, putting it at the 81st percentile (with 100 being the wettest).5 The data can also be broken down by month, which also puts November (when the delegates arrived and the conference started) at 206/253 (81 percent) and December at 157/253 (62 percent), although the temperature for both months was average. The following year was drier, being ranked at 180/253 (71 percent), although the month of November, during which the second session of the RTC concluded its business, ranked at 215/253 (85 percent). The data can also be ranked by region for the period 1873 to 2018. For southeast England, November 1930 ranked 123/146 months (84 percent), and November 1931 ranked 103/146 (70 percent).

The Meteorological Office also produced monthly reports for the period January 1884 to December 1993, which described broader weather observations.6 Coinciding with the inauguration of the RTC in mid-November 1930, cold weather swept over all districts, bringing local fog and rain until the end of the month. London had ten days of fog in November, but in December fog was described as unusually prevalent throughout England. In London it was reported on half the mornings and was still present on a third of the month’s afternoons. On 22 December the fog was described as the most dense in recent years and caused serious transport dislocation. This confounds the historiographical consensus that London fogs disappeared between the Victorian period and the 1950s (Nead Citation2017).

The press reported on the encroaching fogs, with the Evening Standard marking the “first fog of the season” and the first seasonal frost on 17 November 1930.7 On the following day the same paper printed a photograph of the conference venue, barely discernible through thick fog on the RTC’s first day of official work, and reported on an Oxford hurdles relay trial that was run on frozen tracks.8 The conditions worsened through the month, such that by 27 November, the Evening Standard could report “Noon-day lights of Piccadilly-circus, doing their best to cheer things up when London was enveloped in fog today” (see ).9

The following week a “50-mile fog belt round London” was reported, which had descended suddenly, bringing shipping in the Thames Estuary to a halt and reducing visibility to less than fifteen yards (under 14 m) in parts of the capital.10 Ratcheting up the angst, that weekend the tabloid Sunday Pictorial drew on established metaphorical links between fog and mortality (Corton Citation2015) by reporting on the death of sixty-five people in Belgium due to fog-triggered respiratory disorders (“Valley of Fog Terror—Death Mystery Solved”).11 Ten days later, conditions had worsened, resulting in “a fog ‘blacks-out’ [sic]” due to a “blanket that hung in mid-air” during “the day that never came.”12 Due to an inversion (what meteorologists called a “black smoke fog”), many of the streets were clear, even as the fog hung above, blacking out the light. It forced laborers to work using flares, office lights to be kept on all day, and tramcars to move slowly, pushing “their head-lights cautiously out of the murk, moving like ghostly ships on a fog-bound river.” The conditions eased slightly but on 8 January 1931, eleven days before the end of the first sitting of the conference, the secretary of state for India wrote to the viceroy in New Delhi that at 9:30 a.m. the Cabinet had gotten to work “amidst London in a thick rime.”13 To top off the conference’s first session, four days before its conclusion London was blanketed in snow. It was in this weather-blighted city that the delegates carried out their work and against which the conference organizers felt the need to protect them.

The Stage

Diplomacy and international relations depend on materials, composed in assemblages of affect, buildings, performances, and data (Dittmer Citation2017). Cities are key sites for these assemblages, providing the infrastructures to host significant meetings and providing the buzz and monuments to produce a suitable atmosphere. Imperial cities were created as sites of landscape, display, and identity (Driver and Gilbert Citation1999), with interwar London acting as a dramatic theater of empire and Britishness. By day, the docks to the east of the city traded in the colonial goods of empire, whereas the neo-classical architecture of Whitehall testified to imperial London’s claim on the legacy of Rome. By night, these buildings provided the backdrop for more phantasmagorical displays of the city’s might. This was especially the case during an experimental floodlighting of principal buildings in September 1931 in honor of the International Illumination Congress (for a comparison with atmospheric floodlighting fourteen years later, see Sumartojo Citation2014).14 Writing in September 1931 for an Indian audience, from a Britain facing the Great Depression, the author of a column called “Britain Calling” attempted to represent to India the illuminated nighttime geography of the city:

If you were in London now you never would suspect that this is a city over which there hangs a Great Shadow, — the shadow of a second Budget. For London by night’s more entrancing than ever it has been before. Even Carnival time in Venice fades into insignificance compared with the effects of the flood-lighting on the principal buildings of London. There is nothing blatant about it; nothing harsh. It has not meant a gigantic extension of the flaring lights of Piccadilly. Even a poet could not now write of London as a City of Dreadful Light. Rather would he write of it as the City of a Myriad Moonbeams—beams tinted by the fairies.15

The spectacle was to last a month, during which Londoners were said to have gone “floodlight mad.” The opening night of the spectacle had seen Trafalgar Square busier than at any time since the Armistice (which ended World War I in November 1918). The crush had been worth it, though: “The soul of the city seemed laid bare for us.” Although an extravagance in the austere times of the Depression, the lights would “tell the world that London still leads the world,” and it would brighten everyone up: “Anyhow, we shall want that illumination when the India Round Table Conference begins, and perhaps it is a happy omen that we shall have it. For I can find few optimists in political circles here regarding the outcome of that conference. The atmosphere here has not altered.” Like the prologue to this article, the article was written between the first and second sessions of the RTC. It shows how important the theatricality of London was, how it created an atmosphere that could cheer people up and project London’s greatness to the world, also proffering a metaphor regarding the political atmospherics for the RTC.

The conference itself took place at St. James’s Palace. Built in the 1530s by Henry VIII, the palace had been the center of the Royal Court until being displaced by Buckingham Palace in the early 1800s (Scott Citation2010). Although still a site of royal residence, it also held many official functions. On 25 June 1930, the secretary of state for India, Wedgwood Benn, wrote to the first commissioner of works regarding the need for accommodation for the conference “not merely adequate and sufficient, but worthy of the significance of the occasion.”16 Having hosted the Naval Conference of April 1930, St. James was suggested, and on 5 July the king’s assent was received. The press covered plans to stage the conference, including the news that they would be excluded from daily proceedings, to create the right conference atmosphere: “Although the Conference will be unwieldy in some respects, it is the desire of the convenors that the atmosphere should be such that real confidences can be exchanged. This would be impossible were every spoken word to be given to the world.”17

There was also planning underway regarding the delegate’s climatic atmospheres. Technologies were just emerging that promised material interventions into the air directly (Jankovic Citation2010). In London, hotels attempted to outbid each other to attract the business of delegates, the biggest catches being the famously wealthy Indian princes. The Maharaja of Bikaner always stayed at the Carlton, but the Grosvenor House hotel on Park Lane attempted to attract his patronage in a letter from 13 October 1931. They wrote of their entertaining facilities and of their recent refurbishment, especially regarding “Ventilation—this very important factor has had the most scrupulous attention. A unique system of ventilation ensures a constant supply of fresh air—air washed and cooled in a manner not attempted elsewhere.”18 For an autumn conference the concern in London was not, however, keeping delegates cool but keeping them warm.

This was a particular concern for the conference organizers. Many Indian delegates were drawn from the social, business, and political elite and knew London well, but others did not. There was a genuine fear that the London weather would ruin the atmosphere of the conference and possibly even damage the health of those visiting. As such, special measures were put in place. A social club was provided so that the delegates would have somewhere hospitable and warm to spend their evenings. On 6 September 1930, the social secretary for the conference, FAM Vincent, made the case for dedicated accommodation and socializing space being provided. Beyond keeping the delegates in company, and easily contactable, the British winter was a constant referent. The conference was due to run over the isolating Christmas holidays, and “week-ends, in winter, in London, are factors to be reckoned with.”19 As such, Lord Islington agreed to rent them one of his properties, 8 Chesterfield Gardens in Mayfair. On 2 October 1930, he explained to the conference’s secretary-general that, despite his opposition to the conference aims, this was due to the “solicitude on my part for the comfort and ‘life’ of Indians invited to London and confronted with the climate of January and February.”20

There was also the matter of keeping the delegates warm at work. Plans to host an India Office reception in the courtyard of the Foreign Office were dropped when doubts were expressed by the India Office, on 14 October 1930, about the ability to keep it warm during a November evening.21 This organizational failure was relegated to the private India Office archive. The relative climatic success of keeping St. James’s Palace warm, however, attracted comment in the press, which also gives us some insights into racial assumptions about the bodies of Indian delegates.

On 6 November 1930, a week before the conference was due to begin, The Daily Telegraph reported, “For weeks past huge coal fires have been burning in the spacious grates of the Palace, and they will be kept burning day and night until the Conference is over.”22 A week later, on the day that work began in St. James’s, it was reported that the fires would continue for the duration of the conference in the notoriously difficult to heat State Apartments, in an article titled “Warming the Old Palace” (as opposed to the new Buckingham Palace).23 The following week the Daily Mail noted that in addition to great open hearths hosting flames that would not go out for the duration of the conference, scores of additional electric heaters had been installed, to ensure that the temperature never dropped below 70 °F (21 °C). It commented on the disjuncture of climates, bodies, and settings in St. James’s:

From the heat of India to the frost of a November fog the Indian delegates arrived at St James’s Palace in overcoats and mufflers. A few bright turbans were to be seen in the gloom, but there is nothing of the gorgeous panoply of the legendary East about this assembly. It is a company of men (and two women) in black clothes, very much in earnest, and looking very much like an anxious company meeting in the City.24

These stuffy meetings had produced a healthy atmosphere to match that of the healthy temperature, however. Unlike the Naval Conference and Imperial Conference (of April and October–November 1930, respectively), in which speeches had been listened to in stony silence, this gathering was punctuated by applause between speeches: “Here there is a warmth of feeling which makes this a more human affair.”

Indian enjoyment of the political atmosphere of the conference was attributed to the stoking of a hot house environment in the palace. This was assumed to be pleasing to the Indian body but not to the British: “The rooms to be used by the Conference are for many just now uncomfortably hot; but Indians who have visited them during the past few days regard them as ‘entirely agreeable’.”25 Six weeks later, and with conference proceedings accelerating toward a mid-January conclusion, the political and climatic atmospheres were felt by the “Britain Calling” column to have reached a different sort of union: “The pace at which the India Conference is working is rather like the heat of the great palace room in which the delegates sit. It is—hot.”26 As with the Daily Mail, this staged atmosphere was said to affect location (“the result has been to introduce the Tropics to London”) and bodies differently according to race: “The story is told of a British official, who stumbled weakly through the door, leaving behind him the humid atmosphere suggestive of Bombay at is stickiest. ‘Good Lord!’ said he, ‘now at least I can begin to understand all this talk about the white man’s burden’.” This suggests a British delegate, with no experience of India, unable to cope with the “tropical” atmosphere of the India conference. It hints at the racialized reading of bodies in the context of the unplanned, meteorological atmosphere with which the conference organizers had to contend.

Conference Bodies

Indian Attunements to London Weather

Although moaning about the weather and its health impacts was not uncommon for British delegates, real concern was expressed regarding the health and happiness of Indian delegates. Comments divided into those on Indian vulnerability to, and resilience against, the weather and those that used the weather as a metaphor for the political atmosphere.

No doubt to the surprise and relief of many commentators, the majority of delegates did not suffer ill health due to the climate. Yet, at least one had had to refuse an invitation to the conference due to the weather; Sir Ibrahim Rahimtoola had been given strict doctor’s orders to avoid England with winter setting in.27 The fifty-year-old Maharajah of Bikaner, who had fought several desert campaigns during the War and suffered from recurrent malaria, loathed London’s weather. Toward the end of the first session of the conference, he wrote to his son, who had been with him in London but who had returned to India, “You were praying for these black London fogs! We have had more than enough of them several days at a stretch at times. No snow yet; but that is a pleasure to come no doubt.”28 He was dismayed to be recalled to London for the second session and had to return to India five weeks early. A cable sent from Paris on 24 October 1931 explained that he had to leave Europe on health grounds before the fast-approaching severe winter.29

Others chose to stay and suffered. The Indian Christian delegate KT Paul fell ill after the end of the first session and wrote in a letter of 24 December 1930, “The fogs are hellish. My nerves are simply shattered by them. I imagine all sorts of illness, some of which is true, I fear” (as cited in Popley Citation1938, 195–96). Paul’s health deteriorated during the journey back to India, and he died in April 1931. The pacifist and campaigner Horace Alexander had no doubts about the cause of his death: “His effort in the first Conference in fact killed him. He stayed on too long in the winter and within two months after he went back to India he was dead.”30

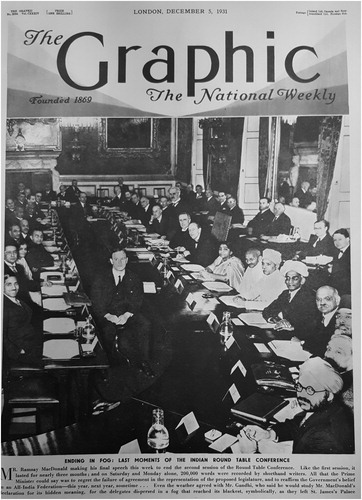

The majority of reports on Indian delegates, however, dwelt on their resilience, although this also served to mark their racial difference, registered through their landscapes and bodies. A December 1930 press report on Indian delegates contrasted the “drab, foggy days” of London during the Christmas recess to the presumed “sunshine and crisp air of their homes” but also noted the delegates’ refusal to complain. One Prince was reported as saying the weather made them feel that they had received the “Freedom of London.”31 This resilience was marked against that of many Londoners. The secretary of state for India noted in his official diary that at an India Office party on 23 December, with “London being enveloped in an almost impenetrable fog,” many European guests stayed away but all Indian guests attended.32 Newspapers regularly featured shots of delegates and staff wrapped in Western coats and, for women, the occasional fur (see from the first day of the second RTC session).33

Figure 2 “An Indian Tour.” Reproduced with permission. © British Library Board (India Office Records, Eur. Mss. G111/4, page 3).

Moving from landscapes to bodies of difference, and mixing its metaphors freely, a newspaper report from November 1930 noted that Indian delegates were not “wilting” under the weather, as many expected them to: “all show considerable ingenuity in adapting their national dress to boreal requirements.”34 That morning an Indian had been spotted crossing Berkeley Square in a downpour, sporting waterproof gaiters and a coat incorporating a hood to cover his turban.

Perhaps the most commented on clothing, especially regarding the weather, was that of Gandhi’s “loincloth.” This was the widely circulating term for his apparel, although as his host in London pointed out, “his dhotie and his fine-spun cashmere shawl seemed as effective in keeping out the cold as any well-cut suit” (Lester Citation1932, 34). Gandhi’s resilience to British politics was read alongside his resilience to the British weather, although the press openly doubted both claims. So while the Evening Standard would report his insistence, made en route from India at Marseilles, that he was “indifferent to climatic conditions,” this “reckless defiance” was said to be oblivious to the inadequacies of his preparations for the English autumn.35 The following day, crossing the English Channel in a driving rain, he admitted that he did not like rain but would put up with anything for Indian freedom.36 The awaiting crowds in London, including many Indians, were likewise resilient to the weather, waiting for three hours in the rain to catch a glimpse.37 Despite this, “a large and cosmopolitan gathering gave him an almost hysterical welcome” at Friends House in Euston.38

At the conclusion of the second session of the conference, Gandhi gave a speech of thanks to the conference chair, Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, linking climate, body, landscape, and the political atmosphere of the conference. Speaking on 1 December 1931, Gandhi complemented MacDonald on his amazing industry, suggesting that this was a product of growing up in a “hardy Scotch climate.”39 With “unexampled ferocity,” MacDonald had worked old men like Gandhi, regardless of physical condition: “But let me say on this matter that although I belong to a climate which is considered to be luxuriant, almost bordering on the equatorial regions, perhaps we might there be able to cross swords with you in industry.” Even if Gandhi could not outwork MacDonald, and even if the conference had brought them to a parting of ways, they would part as friends.

“Conference Autumn”: Atmospheric Metaphors

Gandhi had not evoked weather as metaphor directly, harking rather to environmental determinism while also refuting it. For others, atmospheres offered endless opportunity for metaphorical reflection on the work of the conference. Seasonal migrations, foggy thought, warm hospitality, black horizons of hope, and atmospheres of illusion were used to evoke the conference and, regularly, the difference of Indian landscape and politics.

London’s 1930 “Conference Autumn,” combining the Imperial and Round Table conferences, was said to have already attracted conference swallows, like General Hertzog, in August, in anticipation of the flocks to follow from India.40 Others invoked ingrained climatic assumptions about India as political metaphors. The ex-diplomat and author Harold Nicholson wrote in February 1930, on hearing of the Indian government’s commitment to the RTC, that it should clear the air: “But the air of India is heavy with miasmas, and laden with the poisoned gases of suspicion and fear. Are these the fogs of sundown or the mists which gather before the dawn? We cannot tell.”41

Yet it was the meteorology of London that provided the richest metaphors for conference work. Anticipating the first session, the Maharajah of Alwar wrote to the Maharajah of Bikaner on 31 August 1930: “The weather in London in the mid winter will be something atrocious and I only hope that misty, foggy, snowy London will not contribute to misty, foggy and snowy ideas emanating from persons on all sides.”42 Alwar’s fears were justified regarding the weather, and in a speech on 17 December he appraised the first month of work in London. He claimed to have lost all faith in British seasons, with the summer barely differing from the winter and the winter lacking the charm of snow.43 What it did possess was endless fog, although thicker fogs than those of London were said to exist in human mentalities (the delegates were exempted here). Despite the reputation for Indians being used to broiling in the tropical sun, the roaring fires of hospitality at St. James’s Palace had left them gasping for cool, fresh air.

At the closing of the first session of the conference on 19 January 1931, a meteorological metaphor was also used to comment on the hospitality offered to delegates in London by the Begum Shah Nawaz: “We thank all the British nation for their kind hospitality, help and sympathy; the warmth of our sunny skies which has been lacking in the cold atmosphere of London has been more than supplied by the warmth of the welcome which has been accorded to us.”44 The speech represented the sense of optimism at the end of the first session, with the prospect of an Indian federation in the air. The second session would end with Gandhi’s inability to unite Hindu and Muslim claims and a broader sense of failure.

This had been anticipated, or at least planned for, by Gandhi himself. On departing Bombay for London he had warned his followers, “The horizon is as black as it possibly could be, and there is every chance or my returning empty handed.”45 As the second session neared its close and the chance of meaningful progress seemed to have elapsed, commentators looked to the skies. In an article titled “Fog and Melodrama,” the Manchester Guardian reported a House of Lords debate that had denounced the “atmosphere of illusion and delusion” at the conference, and secretary of state for India, Sir Samuel Hoare, had warned of “drifting into an atmosphere of melodramatic tragedy.”46 When the second session concluded on 1 December, the Daily Express condemned the barren results of the conference: “Nature itself seemed to be in harmony with the occasion. Outside the tall windows of the Palace the chill December fog hung like a funeral mantle over the city, and until the chandeliers were lit the Drawing-room was in semi-darkness.”47 The Graphic splashed a photograph of the concluding session, brightly lit, on its cover but noted that, symbolically, the fog reached its blackest as the delegates left St. James’s Palace (see ).

“The General Afflatus That Prevails in London”: Attuning to the Political Atmosphere

As was apparent in the “Fog and Melodrama” article described earlier, usage of “atmosphere” in a political affective register could be packaged in meteorological terms. Atmosphere was also something that was produced and interpreted at the conference in political terminology that exceeded the climatic, however. Rather than being weather-borne, this atmosphere was affective and interpersonal. It was made by setting and interaction, but it was also transnational. At the opening plenary of the first session on 20 November 1930, the Nawab of Bhopal suggested that Viceroy Irwin had fostered an atmosphere of goodwill in India, which the delegates had brought with them to Britain and that would aid discussion in London.48 As the plenary speeches made it clear that a federation between British and Princely India was likely, the government of India observer, Sir Harry Haig, cabled Delhi on 21 November: “The discussion has produced a distinct atmosphere.”49 The princes’ turn to federation was unanticipated and attributed by another government of India advisor in London, Sir Malcolm Hailey, to the atmosphere. Writing to the Viceroy on 14 November, he admitted that the Princes had been expected to spend time in London simply “airing their tiaras”:50

They, however, have yielded to the general afflatus51 which prevails in London, owing to the deliberations of the Imperial Conference, followed by those of the Indian Conference, and have determined to take a much more definite hand in the proceedings than we could have expected.52

This atmosphere was inconstant and subjective. Newspapers commented on the dimming optimism as the committee work began, when the Hindu–Muslim question threatened to derail the broader work. Yet, by the concluding plenary, the atmosphere of hope, brought from India, could be said to have prevailed. On 16 January 1931 the Maharaja of Rewa claimed, “I think it can fairly be claimed that an atmosphere of good will has prevailed throughout our deliberations; and the creation of this atmosphere is, I believe, in itself a substantial achievement, and one which will go far to assist in the solution of the many problems of detail, some of them sufficiently intractable, which yet await the constitution makers.”53 The task of Indian delegates was to make sure that the seed of hope sown in London would not “wilt in the uncongenial atmosphere of India.”54

The “cordial atmosphere” of the concluding sessions was noted in the press.55 The prime minister’s speech, including a message from the king, was said to have brought “a display of highly charged emotionalism. In such a setting, in such an atmosphere, the voice of reality is out of key.”56 For the Daily Express, the voice of reality told the British that India “is not and never will be a nation,” but others allowed the positive political atmosphere to flourish. The British Liberal delegate Lord Lothian made a speech suggesting that he had never known a conference in which the “spirit” had been so good.57 Reporters commented on the “optimism and good will” with which the delegates were seen off from Victoria Station.58 The good atmosphere was even felt to penetrate the Legislative Assembly in New Delhi, when the conference results were discussed.59

Gandhi’s release from jail and attendance at the second session heightened many people’s optimism. The Federal Structure Committee reassembled before the conference began and assumed their work in “an excellent atmosphere … rather like that of a good public school the evening the boys return from the holidays.”60 All eyes were on Gandhi, but after the “splash” of his arrival, for Indian Christian delegate SK Datta he seemed to focus on his spiritual message and not the “spirit” of the conference.61 Regarding the conference, the British delegate from India representing European business interests, EC Benthall, felt by the end of October that “there is a most depressing feeling about. Gandhi feels rather eclipsed, and misses the publicity which he is used to. … He is feeling the strain, and with a cold snap from the north he is also feeling the weather, having taken to a rather luxurious motor rug to wrap his legs in.”62 On the final day of the second session of the conference, the plenary lacked any “highly charged emotionalism.” The lengthy speeches meant that it ran on past midnight, leaving the prime minister to enter, after a late-night Cabinet meeting, the conference’s “jaded atmosphere.”63 Gandhi’s speech of thanks to the hardy Scottish prime minister followed shortly after, but he left the conference having failed to reconcile Hindu and Muslim nationalist demands.

Gandhi’s speech indicating a parting of ways from the prime minister was interpreted, by some, as signaling a recommitment to civil disobedience. On his return to India, he was arrested and imprisoned in Yervada Central Prison. While there he read a press report by the chair of the Federal Structure Committee, Lord Sankey, that denounced Gandhi’s belligerence at the conference. He wrote a personal letter to Sankey from jail on 2 May 1932, saying how sad he was to be so misrepresented, having worked closely with Sankey (who is placed three seats to Gandhi’s right in ) at the conference.64 He refuted each point and concluded, with a final atmospheric flourish, that

I repeat I am sad. But I am also glad that I am where I am. Perhaps “we shall know each other better when the mists have rolled away.” Yours sincerely, MK Gandhi.65

Conclusion: Reflections on Representing Atmospheres

Following McCormack’s template and having considered the RTC both as meteorological and staged environment affect and as experienced by conference bodies, this article concludes with brief considerations of the reflections that the conference created. This section is, by far, the shortest. The reasons for this are empirical (there was little atmospheric reflection after the event) and epistemological (the much commented-on difficulties of recording atmospheres or of representing the non-representational; see Cresswell Citation2012).

The interest in the RTC and the political capital to be accrued by documenting one’s participation in it led to a veritable cottage industry of conference memoir-ialization. What is striking is how unaffective the accounts of conference atmospheres are in these accounts. Barely any recount the weather, and when political atmospheres are mentioned, they are oddly lifeless. The Princely advisor and later diplomat K. M. Panikkar (Citation1934) would repeat that the RTC created a new atmosphere of collaboration but said little of how it did so or its legacies. The ex-secretary of state, Samuel Hoare, reflected on the traditional atmosphere at the India Office during the RTC, the insensitivities of British politicians to the Indian atmosphere, and Winston Churchill’s constant disruption of the harmonious atmosphere (Hoare Citation1954). The Marquess of Zetland, a British delegate, admitted that St. James provided dramatic qualities and “an atmosphere highly charged with explosive possibilities” (Lawrence Citation1935, 79). The secretary to the British liberal delegation suggested that whereas the first session had opened in a friendly atmosphere, the second opened in an atmosphere of doubt (Coatman Citation1932).

The memoirs lack the vivid prose and affective capacities of the reportage written in the moment, but this is not to suggest that the difficulty of conveying atmosphere is simply a matter of time. This was something that writers struggled with in the moment, too. Writing to his colleague in Calcutta on 19 January 1931, the last day of the first RTC session, EC Benthall explained, “I have tried throughout to keep you informed of all that has been going on with a view to giving you the atmosphere rather than considered opinions, so that you may be in possession of as much useful information as possible and be able to explain why our delegates have done what they have done.”66 Benthall was an attentive observer but still felt that he had struggled to convey the interpersonal relations that undergirded the conference.

The pressure to represent the affective was felt especially keenly by those who were being paid to do precisely that. WH Lewis had been sent from the New Delhi Reforms Office to advise the conference and to keep the government of India informed on developments. He submitted formal reports back to Delhi, but with the end of the conference session in sight, he switched to his own writing paper and filed a personal letter to his Delhi colleague James Dunnett on 6 January 1931. Letting his pen run freely, he suggested, “Reading the proceedings is not an adequate substitute for personal attendance and if I feel that difficulty here in the precincts of St James’s Palace, I can understand that it may not always be easy for you in Delhi to get hold of the atmosphere of the conference.”67 He admitted, on 16 January 1931, that by the end of the first session delegates were exhausted, depressed, and anxious but hopeful for the next session: “There is so much that I want to tell you about it all; some of the impressions not worth writing down others the sort of impression that it would be scarcely proper to put in writing. But I have tried while here to keep my eyes open. By next week I shall have had time to look round + write at greater length.”68 No further letters were, alas, lodged on file. Representational anxieties also featured at the highest level of government. From New Delhi, Viceroy Irwin coveted Sir Malcolm Hailey’s conference body:

Though no doubt the weariness of the flesh must have been almost overwhelming at the time, as you had to sit and listen to interminable speeches, I found myself wishing that I might have been behind the screen to see how it all sounded and felt. It is difficult to catch the atmosphere from here.69

Hailey did not share the Viceroy’s enthusiasm. He was, as Lewis had suggested of the delegates, exhausted. He wrote to Irwin before his Christmas break, anticipating this paper’s interest in his report but also demonstrating the ongoing racialization of the Indian body:

It will be very pleasant to get a couple of days away from all this atmosphere of everlasting discussion in conference and midnight toil outside it. There are times when the Conference Committees seem unbearable; they only seem to alternate in their attitude between the mentality of a bagful of weasels and a cageful of monkeys. But I dare say that at some future date we shall look back on all this as certainly very interesting even if it has not been very profitable.70

Hailey had earlier suggested that the surfacing of Hindu–Muslim tensions was bad for the conference but it would allow the world to “see India for once in its fez and dhoti instead of a top-hat and frock-coat.”71 Comparing the delegates to monkeys might be more explicitly racist than the more familiar commentary on Indian clothing (fez, dhotis, loincloths, and turban hoods), but it forms part of the same continuum by which Indians were attributed to one atmosphere and presumed to react in certain ways to the meteorological and affective atmosphere of imperial London.

This article has not sought to assemble a linear cause–effect relationship between either the weather or the staging of the RTC and its political outcomes. Rather, it has deployed fleeting empiricism to a dispersed archive in the hope of conveying the emergent causality of conference atmospheres. Such atmospheres, whether staged or rolling in on banks of fog, only emerged through the delegates and through commentaries on them but they were still read as causal and of utmost importance to the politics of the conference. These atmospheres registered on Tudor palaces, stoked in turn to keep them warm and hospitable. They registered on human bodies, vulnerable and resilient, who tethered weather to politics in chains of metaphor. This was just one of many strategies through which the elemental and the interpersonal were represented, just as were the frustrations at the limits to discourse.

Although meteorological and affective atmospheres need not always be studied together, this article has argued that there are cases when they must be. Indian conference bodies were seldom read without reference to the presumed landscapes and atmospheres of their origin. Fires were stoked to keep them tropically warm; concerns were raised about their vulnerability to the London autumn and surprise expressed at their resilience to it; metaphors of Indian miasma and illusion were deployed; princes were thought to have yielded to London’s afflatus, while other delegates were described in their fez hats and dhoti clothing, acting like weasels and monkeys. This did the political work of suggesting Indian difference as inferiority or nonmodernity, their out-of-placeness. Unpredictable, emergent, but causal, atmospheres in this study contribute to attempts within cultural geography to represent the non-representational and within historical geography to tease out the more-than-human from the archive. The example of the RTC makes clear that weather, metaphor, and affect are vital components of political meetings and that racial assumptions about all bodies should force us to complicate geographies of solely white atmospheres.

Acknowledgments

I thank the University of Nottingham’s Sensory Studies Network for their series of workshops on atmospheres and Ivan Marković for his advice and support. The paper benefited from discussion at the 2018 Annual Meeting of the American Association of Geographers at New Orleans (and from the ongoing conversations with Shanti Sumartojo that resulted) and at the Spaces of Internationalism conference, which I coorganized at the Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) in December 2018. I am indebted to Mike Heffernan, Jake Hodder, and Ben Thorpe for their collegiality and expert support on the grant project. I am deeply grateful to David Beckingham, Georgina Endfield, Martin Mahony, and Lucy Veale for their detailed comments on early drafts and to Nik Heynen for his generous editorship.

Funding

This research was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council Grant AH/M008142/1: “Conferencing the International: A Cultural and Historical Geography of the Origins of Internationalism (1919–1939).”

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stephen Legg

STEPHEN LEGG is a Professor of Historical Geography in the School of Geography at the University of Nottingham, University Park, Nottingham NG72RD, UK. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests include colonial urban politics and imperial geographies in the interwar period, racial inequalities at international conferences and theoretical methodologies emerging from subaltern and South Asian governmentalities studies.

Notes

1 “Political atmospherics,” The Times of India, 15 May 1931.

2 The newspaper article was quoting the new Secretary of State for India, Sir Samuel Hoare’s House of Commons debate on 13 May 1931.

3 See http://blogs.nottingham.ac.uk/interwarconferencing/2018/02/01/conferencing-and-universities/, accessed on 10 May 2019.

4 Also see https://spacesofinternationalism.omeka.net/exhibits/show/1/scales/body, accessed on 10 May 2019.

5 See https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadukp/, accessed on 21 September 2018.

6 For the monthly weather reports see https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/learning/library/archive-hidden-treasures/monthly-weather-report, accessed on 21 September 2018.

7 “17 degrees of frost,” Evening Standard, 17 November 1930.

8 “Wintry conditions,” Evening Standard, 18 November 1930.

9 “Night-time at noon,” Evening Standard, 27 November 1930.

10 “50-Mile fog belt round London,” Evening Standard, 5 December 1930.

11 “Valley of fog terror—Death mystery solved,” Sunday Pictorial, 7 December 1930.

12 “The day that never came,” Evening Standard, 17 December 1930.

13 BL/European Manuscripts/C152.6/Halifax Viceregal Correspondence, letter from Wedgewood Benn, 8 January 1931 (henceforth Halifax papers).

14 “A flood of light at the cenotaph,” The Star, 1 September 1931; “Lighter London,” The Star, 18 September 1931.

15 “Britain calling, by a wanderer returned from the east,” The Illustrated Weekly of India, 27 September 1931.

16 National Archives, London (NAL), Work/19/248.

17 “India in London,” Indian newspaper clipping, 26 July 1931, newspaper not recorded, from The National Archives of India (NAI)/Home (Poll)/1931/48/II.

18 Maharaja Ganga Singhji Trust Archive (henceforth MGSTA), Bikaner, India, Pad 371/ file 6279.

19 British Library (BL), India Office Records (IOR)/L/PJ/6/2012, File 5080.

20 BL/IOR/L/PJ/6/2012, File 5080.

21 BL/IOR/L/PJ/6/2015, File 5669.

22 “Agenda of India Conference,” The Daily Telegraph, 6 November 1930.

23 “Warming the old palace,” The Daily Telegraph, 13 November 1930.

24 “66 seated at one table: Fires to be kept going day and night,” Daily Mail, 18 November 1930.

25 “Warming the old palace,” 18 November 1930.

26 “Britain calling, by a wanderer returned from the east,” The Illustrated Weekly of India, 14 December 1930.

27 “India Conference,” Times of India, 28 October 1930.

28 Letter from the Maharajah of Bikaner to “Bijey,” 26/12/1930, MGSTA pad 361 file 8261.

29 MGSTA pad 367 file 8557.

30 Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (henceforth NMML), Oral History transcript 12, Horace Alexander.

31 “A prince and the fog,” Evening News, 23 December 1930.

32 Halifax papers, C152.6, Wedgewood Benn diary entry, 23 December 1930.

33 Taken from the newspaper clippings album of W. H. Lewis, BL/European Manuscript/G111/4.

34 “Turbans in the rain,” Evening Standard, 24 November 1930.

35 “Gandhi talks to the Evening Standard: Lands in Europe wearing his Loin cloth: Defiant about the weather,” Evening Standard, 11 September 1931.

36 “Gandhi advises husbands,” Evening Standard, 12 September 1931.

37 “Three hours wait for Gandhi,” The Star, 12 September 1931.

38 “Mr Gandhi on his task,” Evening Standard, 13 September 1931.

39 Government of India, Indian Round Table Conference (Second Session): 7th September, 1931–1st December, 1931. Calcutta: Government of India, Central Publications Branch, 1932, page 296 (henceforth IRT Second Session).

40 “Conference Autumn,” Daily Herald, 22 August 1930.

41 “People and Things,” The Listener, 5 February 1930.

42 MGSTA pad 361 file 2348.

43 Transcript of dinner speeches, NAL/PRO/30/69/578.

44 Government of India, Indian Round Table Conference: 12th November, 1930–19th January, 1931. Calcutta: Government of India, Central Publications Branch, 1931, page 512 (henceforth IRTC).

45 “Gandhi & the Conference: ‘Black Horizon’,” Daily Mail, 4 September 1931.

46 “Fog and melodrama,” Manchester Guardian, 26 November 1931.

47 “Government decision on India,” Daily Express, 2 December 1931.

48 IRTC, page 107.

49 NAI/Reforms/1930/147/30-R.

50 BL/European Manuscripts/E220.34, Letters from Lord Hailey to the Viceroy (henceforth E220.34).

51 Afflatus is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary (2012) as “the communication of supernatural or spiritual knowledge; divine impulse; inspiration, esp. poetic inspiration.”

52 E220.34.

53 IRTC, page 419.

54 Khan Bahadir Hafiz Hidayat Husain, 16 January 1931, IRTC, page 423.

55 “India conference—and the next step,” Daily Telegraph, 20 January 1931.

56 “The Bombay Mob wins,” Daily Express, 20 January 1931.

57 Cited in Halifax papers, C152.6, Wedgewood Benn diary entry, 15 January 1931.

58 “Indian delegates’ departure,” The Times, 25 January 1931.

59 “New sessions in Delhi: Effect of London discussions,” Daily Telegraph, 14 January 1931.

60 “Round-Table Conference,” Manchester Guardian, 8 September 1931.

61 BL/European Manuscript F178.29, Papers of S K Datta, circular to friends from 28 September 1931.

62 Benthall, box 12.

63 “Premier at midnight round table,” Daily Express, 1 December 1931.

64 University of Oxford, Bodleian Library, Papers of John Sankey, Viscount Sankey of Moreton (henceforth Sankey): C539.

65 Sankey: C539. The quote references a hymn of the same title, attributed to Annie H. Barker, 1883.

66 Benthall, box 7.

67 NAI/Reforms/1930/173/30-R.

68 NAI/Reforms/1930/173/30-R.

69 E220.34 Irwin to Hailey, 11 December 1930.

70 E220.34 Hailey to Irwin, 24 December 1930.

71 E220.34 Hailey to Irwin, 15 December 1930. A fez was a hat associated with Muslims in India, and a dhoti was a loincloth associated with Indian Hindus.

References

- Alessandrini, J. A. 2012. “London Fog” and the symbolism of empire: Nineteenth-century artistic representations of atmosphere in London and other imperial sites. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Western Australia.

- Anderson, B. 2017. Encountering affect: Capacities, apparatuses, conditions. London and New York: Routledge.

- Arnold, D. 2006. The tropics and the travelling gaze: India, landscape, and science, 1800–1856. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Ash, J., and B. Anderson. 2015. Atmospheric methods. In Non-representational methodologies, ed. P. Vannini, 34–51. London and New York: Routledge.

- Bille, M., P. Bjerregaard, and T. F. Sørensen. 2015. Staging atmospheres: Materiality, culture, and the texture of the in-between. Emotion, Space and Society 15:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.emospa.2014.11.002.

- Closs Stephens, A., S. M. Hughes, V. Schofield, and S. Sumartojo. 2017. Atmospheric memories: Affect and minor politics at the ten-year anniversary of the London bombings. Emotion, Space and Society 23:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.emospa.2017.03.001.

- Coatman, J. 1932. Years of destiny: India, 1926–1932. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Connolly, W. E. 2011. A world of becoming. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Corton, C. L. 2015. London fog: The biography. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Craggs, R. 2014. Postcolonial geographies, decolonization, and the performance of geopolitics at Commonwealth conferences. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 35 (1):39–55. doi: 10.1111/sjtg.12050.

- Craggs, R. 2018. Subaltern geopolitics and the post-colonial commonwealth, 1965–1990. Political Geography 65:46–56.

- Craggs, R., and M. Mahony. 2014. The geographies of the conference: Knowledge, performance and protest. Geography Compass 8 (6):414–30. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12137.

- Cresswell, T. 2012. Review essay. Non-representational theory and me: Notes of an interested sceptic. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 30 (1):96–105. doi: 10.1068/d494.

- Dittmer, J. 2017. Diplomatic material: Affect, assemblage, and foreign policy. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Driver, F., and D. Gilbert. 1999. Imperial cities: Landscape, display and identity. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

- Edensor, T., and S. Sumartojo. 2015. Designing atmospheres: Introduction to special issue. Visual Communication 14 (3):251–65. doi: 10.1177/1470357215582305.

- Gandy, M. 2017. Urban atmospheres. Cultural Geographies 24 (3):353–74. doi: 10.1177/1474474017712995.

- Griffero, T. 2014. Atmospheres: Aesthetics of emotional spaces. London and New York: Routledge.

- Hoare, S. 1954. Nine troubled years. London: Collins.

- Hodder, J. 2015. Conferencing the international at the World Pacifist Meeting, 1949. Political Geography 49:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2015.03.002.

- Jackson, M., and M. Fannin. 2011. Letting geography fall where it may—Aerographies address the elemental. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 29 (3):435–44. doi: 10.1068/d2903ed.

- Jankovic, V. 2010. Confronting the climate: British airs and the making of environmental medicine. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lawrence, J. L. D. 1935. Steps toward Indian home rule. London: Hutchinson. doi: 10.1093/ia/15.4.594.

- Lee, C. J. 2010. Introduction: Between a moment and an era: The origins and afterlives of Bandung. In Making a world after empire: The Bandung moment and its political afterlives, ed. C. J. Lee, 1–42. Athens: Ohio University Press.

- Lester, M. 1932. Entertaining Gandhi. London: Ivor Nicholson & Watson.

- Mahony, M. 2016. For an empire of “all types of climate”: Meteorology as an imperial science. Journal of Historical Geography 51:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jhg.2015.11.003.

- Mahony, M. 2019. Historical geographies of the future: Airships and the making of imperial atmospheres. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 109 (4):1279–99.

- Mahony, M., and G. Endfield. 2018. Climate and colonialism. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 9 (2):e510. doi: 10.1002/wcc.510.

- Martin, C. 2011. Fog-bound: Aerial space and the elemental entanglements of body-with-world. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 29 (3):454–68. doi: 10.1068/d10609.

- McCormack, D. P. 2008. Engineering affective atmospheres on the moving geographies of the 1897 Andrée expedition. Cultural Geographies 15 (4):413–30. doi: 10.1177/1474474008094314.

- McCormack, D. P. 2018. Atmospheric things: On the allure of elemental envelopment. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Nead, L. 2017. The tiger in the smoke: Visual culture in Britain c.1945–1960. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Neumann, I. B. 2008. The body of the diplomat. European Journal of International Relations 14 (4):671–95. doi: 10.1177/1354066108097557.

- Neumann, I. B. 2013. Diplomatic sites: A critical enquiry. London: Hurst.

- Panikkar, K. M. 1934. The new empire. London: Martin Hopkinson.

- Peters, K. A., P. E. Steinberg, and E. Stratford, eds. 2018. Territory beyond Terra. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Popley, H. A. 1938. K.T. Paul: Christian leader. Calcutta, India: Y.M.C.A. Publishing House.

- Scott, K. 2010. St James’s palace: A history. London: Scala.

- Semple, E. C. 1933. Influences of geographic environment, on the basis of Ratzel’s system of anthropo-geography. London: Constable & Company. doi: 10.1086/ahr/17.2.355.

- Shimazu, N. 2012. Places in diplomacy. Political Geography 31 (6):335–36. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2012.03.005.

- Shimazu, N. 2014. Diplomacy as theatre: Staging the Bandung Conference of 1955. Modern Asian Studies 48 (1):225–52.

- Sumartojo, S. 2014. “Dazzling relief”: Floodlighting and national affective atmospheres on VE Day 1945. Journal of Historical Geography 45:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jhg.2014.05.032.

- Sumartojo, S. 2019. Sensory impact: Memory, affect and photo-elicitation at official memory sites. In Doing memory research: New methods and approaches, ed. D. Drozdzewski and C. Birdsall, 21–38. London: Palgrave.

- Sumartojo, S., and S. Pink. 2018. Atmospheres and the experiential world: Theory and methods. London and New York: Routledge.

- Tolia-Kelly, D. P. 2006. Affect—An ethnocentric encounter? Exploring the “universalist” imperative of emotional/affectual geographies. Area 38:213–17.

- Vick, B. E. 2014. The congress of Vienna: Power and politics after Napoleon. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wall, I. R. 2019. Policing atmospheres: Crowds, protest and “atmotechnics.” Theory, Culture & Society 36 (4):143–62.

- Weisser, F. 2014. Practices, politics, performativities: Documents in the international negotiations on climate change. Political Geography 40:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2014.02.007.

- Weisser, F., and D. Müller-Mahn. 2017. No place for the political: Micro‐geographies of the Paris climate conference 2015. Antipode 49 (3):802–20. doi: 10.1111/anti.12290.