Abstract

This article examines the factors shaping the perception of climate change and the relationship between climate change perception and migration. Drawing on a 691-case survey of climate perceptions in Cambodia, it explores three dimensions of climate change perception. The first is the relationship of climate change perceptions to space, geography, and scale. Second is the influence of livelihoods to climate change perceptions, and third is the relationship of climate perceptions to migration. The results show that perceptions of climate change are not significantly influenced by spatial distance, meaning that divergent or even opposite climate perceptions might coexist within a relatively small geographical area. The data, however, show that climate perceptions are significantly influenced by both engagement in certain primary livelihoods and contextually specified socioeconomic marginality. Despite this subjectivity of climate perceptions, a strong, statistically significant relationship exists between climate change perception and the prevalence of migrants in the household. Overarchingly, the article challenges efforts to infer direct linkages between climate data and human behavior, arguing instead for a more subjectively attuned understanding of the impacts of climate change on migration, to account for the multiple factors that influence perceptions of and responses to climate change.

本文讨论了气候变化认知、气候变化认知与移民关系的塑造因素。通过柬埔寨691 个气候认知调查案例,本文探讨了气候变化认知的三个方面:气候变化认知与空间、地理和尺度的关系,谋生对气候变化认知的影响,气候认知与移民的关系。结果显示,气候变化认知受空间距离的影响不大,意味着不同甚至相反的气候认知可以在相对较小的地理范围内共存。然而,数据显示,某些谋生手段、特定社会经济条件下的边缘化程度,对气候认知的影响非常大。除了主观的气候认知,气候变化认知和家庭成员的移民比重之间有很强的统计相关性。总体来说,为了解释气候变化的认知及反应的影响因素,本文质疑了直接关联气候数据和人类行为的研究,认为应更主观地去理解气候变化对移民的影响。

Este artículo examina los factores que conforman la percepción del cambio climático, y la relación entre percepción del cambio climático y migración. Con base en un estudio de 69 casos de percepciones climáticas en Camboya, el artículo explora tres dimensione de percepción de cambio climático. La primera es la relación de las percepciones del cambio climático con el espacio, la geografía y la escala. La segunda es la influencia de los modos de sustento con las percepciones del cambio climático, y la tercera la relación de las percepciones del clima con la migración. Los resultados muestran que las percepciones del cambio climático no están significativamente influidas por la distancia espacial, lo cual significa que percepciones del clima divergentes o incluso opuestas podrían coexistir dentro de un área geográfica relativamente pequeña. Sin embargo, los datos muestran que las percepciones están influidas significativamente por el compromiso con ciertos medios de sustento primarios, y contextualmente con una marginalidad socioeconómica especificada. A pesar de la subjetividad de las percepciones climáticas, existe una fuerte y estadísticamente significativa relación entre la percepción del cambio climático y la prevalencia de migrantes en el hogar. Por sobre todo, el artículo reta los esfuerzos por inferir lazos directos entre los datos del clima y la conducta humana, respaldando por el contrario un entendimiento de los impactos del cambio climático sobre la migración más a tono con la subjetividad, para tomar en cuenta los múltiples factores que influyen las percepciones del cambio climático y las respuestas al mismo.

As declarations of a “climate emergency” by a succession of countries place climate change “at the centre of policy and planning decisions” (Turney Citation2019, 1), its human impacts have moved to the forefront of contemporary politics and policymaking. In particular, its impacts on human migration have been cast as a key global policy priority in recent years, with a growing list of governments, from the United Kingdom to Germany to the European Union, adopting a securitized lens on the issue (White Citation2012; Boas Citation2015). The result has been a “weaponising” of both migration (Misra Citation2018, 1) and adaptation (K. A. Thomas and Warner Citation2019), wherein the assumed necessity of solutions has come to shape the nature of the phenomena themselves, via a “transfiguration of threatened populations into threatening populations through climate change securitization” (K. A. Thomas and Warner Citation2019, 1).

Above all, the issue of climate migration is pervaded by a sense of exceptionalism: the undergirding assumption that migration promulgated by climate change is fundamentally distinct in character from migration in other forms. Not only does this contribute to its discursive construction as a “problem” but in a practical sense shapes the tools of its investigation. The assumed need to discern that part of mobility that is specifically and separately engendered by climate change has spawned a very particular set of methods. Above all, Ricardian analysis—wherein existing population data sets are cross-referenced with climate data—have come to dominate the analysis of climate migration, with global quantitative figures becoming characteristic of a field increasingly defined by its “quest for ever larger numbers” (Jakobeit and Methmann Citation2012, 301). Well-publicized studies over the years have invariably centered on headline figures, from the Overseas Development Institute estimation of 24 million displaced in 2016, via World Bank (Citation2018) and academic (Jacobson Citation1988; Myers Citation1997, Citation2002; Stern Citation2007) projections of between 140 million and 1 billion climate migrants by 2050, to the current leading figure of 2 billion by 2100 (Geisler and Currens Citation2017).

Despite the range of these estimates, the aim in each case is to discern a more or less direct relationship between physical environmental and human population data, a goal to which much criticism has been addressed for its failure to consider the social contexts and conditions of migration (Piguet et al. Citation2011; Faist and Schade Citation2013; Gesing, Herbeck, and Klepp Citation2014; Nicholson Citation2014). Climate migration scholars have responded by introducing intermediary social and cultural variables (e.g., Adger et al. Citation2013; McCarthy et al. Citation2014). Yet the most intractable problem remains that of scale. Because climate migration research relies on existing climate data sets, the scale of analysis is determined not by the research question at hand but by the logistics of climate measurement infrastructure (Gubler et al. Citation2017). Not only are the “resolution,” coverage, and quality of these data variable—often problematically so in the Global South (Fussell, Curtis, and DeWaard Citation2014; Gubler et al. Citation2017; Johnson and Rampini Citation2017)—but the very nature of the data available has generally precluded quantitative analysis of climate migration at the community scale familiar to migration and adaptation scholars.

This scalar disjuncture has led in recent years to growing interest in subjective climate change perceptions, as a measure of resilience (Clare et al. Citation2017), risk perception (Funatsu et al. Citation2019; Zander, Richerzhagen, and Garnett Citation2019), and risk management (Carmenta et al. Citation2017). Nevertheless, this work has been limited in scope. Up to now, work examining climate perception in the Global South (Maddison Citation2007; Slegers Citation2008; Deressa, Hassan, and Ringler Citation2011; Ejembi and Alfa Citation2012; Vulturius et al. Citation2018; Funatsu et al. Citation2019) has tended to be directed toward testing the closeness of fit between perceived and recorded climate data, with relatively few studies (see Zander, Richerzhagen, and Garnett [Citation2019]; De Longueville et al. [Citation2020], for two recent exceptions), exploring the impact of climate perception on migration specifically.

This study seeks to extend this analysis, demonstrating not only that climate perceptions are significantly related to migration decisions but also the manner in which these perceptions are subjectively attuned to social and livelihoods factors. Decentering the question of fit between physical data and human perceptions of climate change, the article therefore explores the determinants and value of climate perception data, examining in depth the relationship between climate change perception and migration in three Cambodian communities defined by large internal socioeconomic differences between marginal and better-off households. A key point of the article is thus that climate change perceptions are not an effective proxy for physical climate data but should constitute an important sphere of research in their own right when wanting to understand the local impacts of climate change, as well as adaptation measures such as migration.

Connected to this, the article additionally challenges the frequently used contention that adaptation in situ is preferred among those with the resources to do so over migration (Bardsley and Hugo Citation2010; Zander, Petheram, and Garnett Citation2013; Laurice Jamero et al. Citation2017; Stojanov et al. Citation2017). In contrast to the recent literature on climate migration (Richards and Bradshaw Citation2017; Conway et al. Citation2019), our results indicate that socially and economically marginal households are not only less likely to migrate than better-off households—results that closely align with the migration literature in general (Stark and Bloom Citation1985; Skeldon Citation2002)—but less likely also to subjectively perceive changes in the climate.

After outlining the conceptual, methodological, and empirical framing of the study, the article addresses how perceptions are linked to adaptation measures focusing on migration. First, we outline the role of livelihoods in shaping climate perception; second, we highlight the relationship between climate perception and migration; and, finally, we interrogate the assumption that climate migration is most likely to occur among the most marginal members of communities. A discussion of the implications of these findings, focusing in particular on the role of climate perceptions within climate migration research and the need for a more nuanced and subjective approach to linking the two, will follow. A conclusion ends the article.

Climate Migration and the Subjectivity of Climate Perception

Among the myriad impacts of the changing climate, one of the most frequently and passionately discussed is the impact on human migration. In public discourse “we are told that such movement is unprecedented, that it represents a crisis, a flood, a disaster” (Hamid Citation2019, 20). Moreover, this is a position that pervades scientific analysis, encouraging a reliance on “topographies and maps of so-called hot spots of existing and expected climate-change migration,” rather than migration systems more broadly (Klepp Citation2017, 8). Nevertheless, even as the policy relevance of understanding and modeling such relationships increases, criticism of the methods employed to do so has risen in tandem. Climate migration models have been accused of arbitrary causal reasoning on the one hand (O’Brien Citation2013; Nicholson Citation2014; Meyer Citation2016) and binary and monofactoral thinking on the other; that is, does a given environmental variable impact aggregate migration or not—in others (Gómez Citation2013).

In response, “a wave of new social science research into these hitherto under-emphasized cultural dimensions of climate change” (Adger et al. Citation2013, 112) has emerged, bringing much-needed nuance to the field. A key practical challenge facing climate modeling, however, is low-resolution climate data, especially in the Global South (Eklund et al. Citation2016), that leaves many studies with few practical options beyond upscaling and interpolating data in such a way as to elide issues of quality and distribution in certain areas (Eklund et al. Citation2016). Recognizing such shortcomings, efforts have been made to make greater use of alternative, smaller scale data on changing livelihoods, migrations, and adaptations. Nevertheless, a significant discrepancy remains “between the large scale at which biophysical impacts of climate change are generally studied, and the local scale of analysis typically adopted in bottom-up studies” (Conway et al. Citation2019, 504).

In recent years, interest in bridging this scalar lacuna—alongside a wider sense that “people-centred effects cannot be examined through meteorological observation alone” (Rankoana Citation2018, 367)—has resulted in growing attention toward the potential of climate perception as a proxy for climate impacts (see Karki et al. [2020] for a review of the climate perception literature). Studies exploring perceptions of climate change in both the Global North (Diggs Citation1991; Leiserowitz Citation2010; Semenza et al. Citation2008; Weber Citation2010; Akter and Bennett Citation2011; Hansen, Sato, and Ruedy Citation2012; Rankoana Citation2018; Whitmarsh and Capstick Citation2018) and Global South (Vedwan and Rhoades Citation2001; Hageback et al. Citation2005; Maddison Citation2007; D. S. Thomas et al. Citation2007; Ishaya and Abaje Citation2008; Slegers Citation2008; Gbetibouo Citation2009; Mertz et al. Citation2009; Deressa, Hassan, and Ringler Citation2011; Ejembi and Alfa Citation2012) show a majority of the study population having perceived climate change.

As interest in the value of climate perception data grows, however, it is increasingly recognized that the perception of climate change is shaped not only by physical changes in the climate but also by intermediary socioeconomic factors that frame the experience of climate change at community, household, and individual scales. The most recent literature acknowledges “both household internal dynamics and broader external factors, such as agro-ecological, climatic, and institutional economic and political frame conditions” (Žurovec and Vedeld Citation2019, 1). More specifically, acknowledgment is growing that environmental changes are perceived in large part through the lens of people’s livelihoods (Slegers Citation2008; Nielsen and Reenberg Citation2010; Ejembi and Alfa Citation2012; D’haen, Nielsen, and Lambin Citation2014; Macchi, Gurung, and Hoermann Citation2015; Rankoana Citation2018; Žurovec and Vedeld Citation2019; Funk et al. Citation2020) due to their impact on resource availability.

This is in some senses intuitive. Water scarcity—or the unreliability of water availability—for example, is both a key impact of climate change and strongly dependent on the use to which this water is put. Whereas paddy rice, for example, is estimated to require an average of 1,673 liters of water per kilogram to produce, cabbage requires only 237 (Mekonnen and Hoekstra Citation2011). Assuming that both access water from a common source, therefore, a rice farmer is likely to be considerably more sensitive to changes in the availability of water than a cabbage farmer.

From this perspective, the inherent difficulties in disentangling local environmental and broader climatic factors are rendered moot by the centrality of livelihoods to climate knowledge. Climate perception is very likely both a communally and individually mediated knowledge: the product of both received wisdom and subjective, personal experience. People experience risks themselves, but so, too, they invest time “communicating about risks” (Wahlberg and Schoberg Citation2000, 31), meaning that “interpersonal” and “personal” risk perception play a role in shaping conceptions of the climate (Wahlberg and Schoberg Citation2000, 31). Thus, climate perception exists at the nexus of these two framings. It is both tangibly felt and absorbed from the wider milieu, so that group membership, as well as livelihoods themselves, may influence climate perception (Warner Citation2010), especially in countries—such as the one explored in this article—where formal sources of climate data are generally lacking.

Moreover, the corollary here is of equal significance. Just as group membership shapes climate perception, so, too, then must group nonmembership, a principle with far-reaching implications for the much-discussed impact of climate change on marginal communities, or marginal members of communities. Despite nuanced analysis of the nexus of “marginality” and migration in a general sense (see, e.g., Kretsedemas, Capetillo-Ponce, and Jacobs Citation2013), this is a concept often left unpacked in the climate migration literature. Whereas vulnerability is essentially an externally relational state—that is, it describes the “exposure, system sensitivity, and adaptive capacity” (McLeman and Hunter Citation2010, 1) to something distinct from the community itself—marginality is internally relational: Somebody may be marginal regardless of the presence of a given threat. Thus, as a social and political construct, it is both highly variable and profoundly attuned to environmental and social context.

From this standpoint, therefore, this article is directed toward two interlinked objectives. Leaving the discussion of climate perception as a proxy for physical climate data aside, it aims first to clarify the nature of the factors that influence climate perception, the relation of these factors to livelihoods, and the role of marginality in shaping climate perception. Second, the article seeks to demonstrate the utility of climate perception data as a tool within climate migration analysis. In this way, the approaches outlined here serve to advocate a more person-centered, subjective analytical approach to the relationship between climate change and human mobility.

Methodology

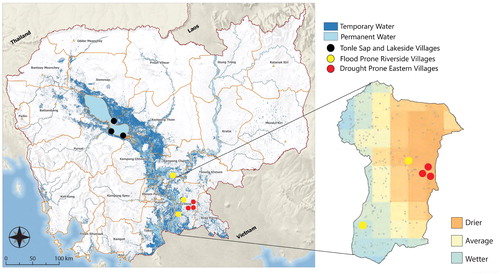

Data were collected across nine village sites (see ) located in some of the most climate-vulnerable regions of Cambodia. The nine sites were selected on the basis of (1) high levels of environmental vulnerability, (2) high levels of migration, and (3) high levels of socioeconomic marginality. They are grouped into three agro-ecological zones that cross-cut provincial boundaries to better reflect the environmental characteristics of the country. The first zone, the Tonle Sap and lakeside zone—incorporating three floating villages in Kampong Chhnang, Pursat, and Kampong Thom—was selected because of the vulnerability of its fisheries to high temperatures and prolonged droughts (Oudry, Pak, and Chea Citation2016; Uk et al. Citation2018). The second zone, the flood-prone riverside zone—incorporating three villages in Kampong Cham and Prey Veng provinces—is distributed across the alluvial regions adjacent to the Mekong River, a zone with a historic propensity to both floods and droughts (Assessment Capacities Project Citation2011). The final zone, the drought-prone east zone—incorporating three villages contained within Prey Veng province—is located in the drought-prone regions close to the eastern border of the country (European Space Agency Citation2019), which have been identified as highly vulnerable to climate change due to the impact of both chronic and severe droughts on heavily rice-dependent monocropping (Assessment Capacities Project Citation2011).

Figure 1 Study site locations, flood and drought in Cambodia (Source: Open Development Cambodia) and Prey Veng province (inset; Source: European Space Agency Citation2019).

Migration also played a crucial role for site selection, with all nine village sites located in provinces where high proportions of the population work outside of their home villages. Of Cambodia’s twenty-five provinces, for example, Prey Veng, in which five of the nine sites are located, has the highest proportion nationally of internal migrants, and Kampong Cham, in which a single study site is located, has the third highest level. Of the three provinces containing the three sites in the Tonle Sap and lakeside zone, Kampong Thom has the fourth highest level of internal migration, Pursat has the seventh highest, and Kampong Chhnang has the eleventh highest. As such, being both climatically vulnerable and associated with high levels of migration, the nine sites are ideal loci to examine the intersection of climate change and migration dynamics.

Finally, to capture the role of marginality in relation to climate migration—and in particular how socioeconomic marginality plays a role in structuring the perceptions and response to climate change (Chu and Michael Citation2019)—the nine sites were additionally selected on the basis of the presence of marginalized groups. Three socioeconomically marginalized groups, brick workers, beggars, and ethnic Vietnamese populations, were selected. Brick workers and their households are characterized by multidimensional marginality rooted in their poverty, lack of assets, and the social stigma attached to their work. Beggars suffer social exclusion and poverty (Beazley and Miller Citation2015; Springer Citation2017; Parsons and Lawreniuk Citation2018; Parsons Citation2019), and Vietnamese communities are characterized by physical and social marginality, as well as political exclusion (Berman Citation1996; Amer Citation2013; Sperfeldt Citation2017; Parsons and Lawreniuk Citation2018; Canzutti Citation2019). From the perspective that marginality is coconstituted by natural environmental, economic, and social factors (Von Braun and Gatzweiler Citation2014; Chu and Michael Citation2019), the three groups were also selected on the basis of their geographical concentration in (and historical association with) parts of Cambodia characterized by ecological and environmental precarity. Thus, three of the target villages had high proportions of brick workers relative to the national average, three had high concentrations of beggars, and three had high concentrations of ethnic Vietnamese households.

In each of the nine villages, every household belonging to one of the three marginalized groups was presampled before the arrival of enumerators. A randomly selected sample of the remaining households of the village, equal in size to the targeted group members, was then selected to provide a comparative data set. Both the marginalized households and randomly selected cohort were then given a survey. The total amount of surveyed households across the nine villages was 691. The survey was designed to collect data on social and demographic indicators, perception of climate change perceptions, livelihoods, and migration patterns associated with each household.

Household characteristics such as composition, income, assets, and social and demographic indicators were collected via the survey. To capture climate impact, eleven indicators were selected: drought, rainfall, temperature, fires, soil problems, wind, insect infestations, livestock diseases, floods, new plant species, and new animal species. These were identified from literature (Migrating Out of Poverty Program Citation2013; International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development Citation2014) and information collected in the villages prior to implementing the surveys. The survey explored perceptions of changes to these eleven indicators over the past ten years, from 2008 to 2018. Although considerably less than the usual thirty-year period for climatic measurement, this ten-year period was selected to balance degradation in recall accuracy over time (Berney and Blane Citation1997; De Nicola and Giné Citation2012) against the minimal period over which to infer trends in the climate over time, identified elsewhere (Australian Bureau of Meteorology Citation2007; Kolawole et al. Citation2016) as ten years.

The surveys were delivered in Khmer by an experienced team of two Cambodian researchers, using the electronic data collection tool Kobo Toolbox. On average one survey took forty-five minutes to conduct. The surveys were conducted in two phases: February to March 2018 and February to March 2019. They were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 24.

In addition, eighty-five qualitative interviews were undertaken with survey informants and local officials to establish the background and context of the quantitative findings. From initial scoping interviews, via the supervision of the quantitative survey, through to qualitative follow-up interviews, the first author visited the surveyed villages on multiple occasions over two periods of two months each, adding insights into social practices and livelihood activities. Alongside informal conversations, the majority of interviews were undertaken in Khmer by a separate two-person team, one of whom is a native speaker and the other of whom is proficient in the language. The remainder of the interviews, either with native, fluent, or proficient English speakers, were conducted in English by the first author. All qualitative interviews were analyzed using the qualitative analysis tool NVivo 11.

Climate Change Data, Mobility, and Perception in Cambodia

In terms of both climate change impacts and migration prevalence, Cambodia is an exceptional site, ranked the world’s second most vulnerable country to climate change in 2014 (Kreft et al. Citation2014; Kreft et al. 2016). Climate change is now routinely described as “a major threat” to the economy and society of Cambodia (Khut Citation2017). Historical records indicate significant changes in rainfall patterns since the 1920s (Diepart Citation2015), and over the last two decades, increasingly sporadic, unpredictable, and intense rains have badly affected farmers’ livelihoods (Diepart Citation2015). In particular, the unpredictability of rainfall has transformed irrigation from agricultural luxury to basic necessity for many farmers, resulting in a growing need for capital investment (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and World Bank Citation2015).

A large share of this capital is obtained via external and internal labor migration (Bylander Citation2015; Oudry, Pak, and Chea Citation2016). Over a third of Cambodians have lived in more than one province in their lifetime, with almost 10 percent of the population living abroad, predominantly for work (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation Citation2018). Migration is also connected to the transition from the traditional transplanting method of farming—wherein seedlings are raised in a nursery plot before replanting—to a system of broadcasting, in which seeds are scattered directly onto larger plots (Liese et al. Citation2014; Shrestha et al. Citation2018). As the labor-intensive transplanting method has been replaced by the broadcasting system requiring only one fifteenth of the labor (Liese et al. Citation2014), a large proportion of rural people have been forced to look elsewhere for employment.

Despite widespread acceptance of the impacts of climate change and rural marketization on Cambodia’s population movement, detailed information on this relationship is sparse (Jacobson et al. Citation2019). This is in large part due to the low resolution and unreliability of climate data across the kingdom’s “instrument-poor” weather monitoring infrastructure (Chhinh and Millington Citation2015, 798). Sparsely positioned weather stations—long acknowledged by the World Bank and others to be lagging behind (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction Citation2010) others in the region—offer accurate data on only a small subsection of each province. Even in those areas, inaccuracies and gaps in data remain an issue (Chhinh and Millington Citation2015). Given the significant differences in rainfall patterns in evidence at both the provincial and subprovincial scales (Vance et al. Citation2004) and across the kingdom’s eight hydrological regions (Thoeun Citation2015), this constitutes a major barrier to effective analysis of the specific impacts of the changing climate. Moreover, the only properly maintained weather stations are usually positioned in close proximity to either the geographic or urban center of each province. Given that many of Cambodia’s most politically marginalized people—in particular those lacking citizenship and property rights—live far from these urban centers (Messerli et al. Citation2015), this leaves understanding of environmental shifts least accurate for those with the fewest resources and the least political agency.

Thus, there is increasing consensus surrounding the need for “a new paradigm that joins traditional climate research with research on climate adaptation” (Overpeck et al. Citation2011, 702) to bridge the gap between top-down and bottom-up approaches, both globally (Conway et al. Citation2019) and in Cambodia (Jacobson et al. Citation2019; Parsons and Chann Citation2019). The role of climate perceptions offers a possible bridge in this respect, offering the potential to relate the physical and social dimensions of climate response in a meaningful and productive manner—especially in relation to the role of marginality in driving climate migration (e.g., Marino Citation2012; Warner and Afifi Citation2014; Panda Citation2017; Conway et al. Citation2019).

Nevertheless, the subjectivity of climate change perceptions has historically been used as an argument against their usefulness (Weber Citation2010; Hansen, Sato, and Ruedy Citation2012). Individuals are assumed, with some basis, to lack the ability to make objective judgments on long-term climatic trends, due to their embeddedness in socioeconomic and cultural systems. In the United States, for example, Smith et al. (Citation2014) identified gender, education, income, and political affiliation as key variables in the perception of climate change. Similarly, in Ethiopia, Deressa, Hassan, and Ringler (Citation2011) summarized that “farmers’ perception of climate change was significantly related to the age of the head of the household, wealth, knowledge of climate change, social capital and agro-ecological settings” (23). Yet positive assessments of the accuracy of climate perceptions in some contexts, ranging from “qualitatively congruent” (Funatsu et al. Citation2019, 7) to “highly accurate” (Hein et al. Citation2019, 1) support the strength of the relationship between climate perception and measurement. Indeed, as outlined in , the data observed through this study appear to indicate that respondents observed climatic changes in all three sites.

Table 1. Perception of climate change indicators disaggregated by agro-ecological zone

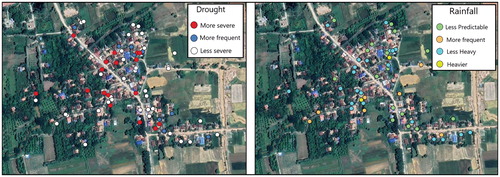

Nevertheless, as with observed climate data, the perception data shown in reveal significant differences across each of the regional contexts. The greatest consistency between sites is exhibited in the perception of temperature, in relation to which between 84.1 percent and 100 percent of respondents noted changes. The greatest range of responses was observed in relation to drought, with responses averaging between 1.1 percent and 75.3 percent according to site. Interestingly, variation was also observed within sites, indicating that the observed variance cannot be explained solely by agro-ecological differences but rather incorporates a socioeconomically determined subjective dimension (). Indeed, as exemplified in , multiscalar analysis reveals the limitations of a purely geographical interpretation of climate perception. Although community-scale differences might be apparently observed at the provincial scale, reducing the scale of analysis reveals the extent to which competing perceptions of climate phenomena are geographically interspersed.

Figure 2 Drought perception at the provincial, commune, and village scales. Each dot represents a respondent household. Green dots are those reporting changes in drought. Red dots are those reporting no change.

An analysis of the direction of environmental issues observed by respondents echoes this finding. Rather than establishing comparable trends regarding, for example, floods and droughts, the data indicate significantly different—often diametrically so—perceptions of environmental trends between households in close proximity of one another, severely undermining the potential of climate perception as a proxy for small-scale climatological data.

Indeed, as shown in , respondents in some cases reported opposite experiences of changes to rainfall and drought over the past decade, despite their homes and agricultural land being in close (i.e., less than 1 km) proximity. Nevertheless, as this article aims to show, the lack of consistency in small-scale geographical reporting of climate perceptions does not render the data useless, nor should inconsistency be confused with randomness. Rather, if, as long noted in the literature on climate perception in the Global North, perceptions are predictably structured by social and economic characteristics, then the same might also be true in the Global South. What follows will explore this position in relation to climate perception and livelihoods specifically.

Climate Perception and Livelihoods

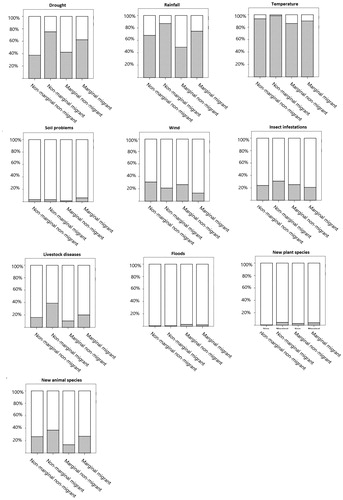

The relationship between climate change perception and livelihoods is both important and underresearched (Kolawole et al. Citation2016; Fadairo, Williams, and Nalwanga Citation2019). Although less readily available in cross-sectional data sets than socioeconomic and demographic indicators such as age, wealth, and gender, data on livelihoods constitute a potentially powerful predictor of climate perception, framing climatic factors according to particular economic sensitivities. Indeed, this relationship is supported by the data here. As highlighted in , a comparison of climate perception data among fishers and nonfishers across all three agro-ecological zones reveals statistically significant differences in climate perception in four out of ten climate variables.

Table 2. Climate perception of fishers and nonfishers

Although certain perceptions relate to the possession of assets—fishers are less likely to possess livestock, for example, and thus less likely to perceive changes in diseases affecting them—many of the perceptions relate specifically to the manner in which climatic variations influence the performance of livelihoods. For example, strong winds and high temperatures are viewed as a problem for fish stocks, heightening fishers’ sensitivity to changes in the wind and thus the likelihood of perceiving them. In addition, this point is further exemplified by an examination of the data on farmers’ perceptions of the climate. As shown in , farmers exhibit a notably different profile of climate perception, less sensitive than fishers to wind and temperature changes but more sensitive than both fishers and the data set average to all other indicators besides floods. This reflects, again, both the possession of assets—farmers are much more likely than fishers to possess livestock, for example—but also how perception of the climate is structured by farmers’ livelihoods. Simply put, droughts and changes in rainfall have a far greater impact on those who depend on readily available water supplies for their livelihood than those, such as fishers or modern sector workers, who do not.

Table 3. Climate perception of farmers and nonfarmers

Although differences in overall reporting of climatic changes are significantly related to livelihoods, reporting on the direction or type of change shows a far weaker relationship. As outlined earlier, respondents demonstrate a limited ability to perceive the same specific changes in their environment. What our respondents are perceiving is therefore likely related to differences in their livelihoods, which they associate with specific environmental needs, challenges, and features. This is highlighted by the lack of statistically significant variations between farmers’ and nonfarmers’ perceptions of the type of changes evident in rainfall, outlined in . Moreover, although the space available here is insufficient to present disaggregated data on each climatic feature, a similar lack of correlation was evident in the case of other indicators of climate perception, such as drought and new animal and plant species.

Table 4. Type of change in rainfall among farmers and nonfarmers

Climate Perception, Migration, and Marginality

The findings reported here have implications for the literature on climate change and migration (e.g., Jacobson Citation1988; Myers Citation1997, Citation2002; International Organisation for Migration Citation2019) because of their implications for the strength and directness of the relationship between climate change, the perception of climate change, and action in response to perceived climate change. In some cases, climate change has been viewed as driver of migration (McLeman and Hunter Citation2010; Black et al. Citation2011), whereas in others (Mortreux and Barnett Citation2009; Kelman et al. Citation2019) it has been viewed as a less significant factor. Nevertheless, the debate is characterized by the assumption that the perception and physical incidence of climate change are covariant, a premise that is rendered problematic by the intermediary role of livelihoods.

As shown in , migration rates vary significantly across the three agro-ecological zones under study. Whereas migration rates in the Tonle Sap and lakeside zone are well below the national average, the flood-prone riverside zone and drought-prone east zones demonstrate far higher levels of migrant households (as well as migrants per household). Informants’ residence across one of the three locations is a significant indicator of migration behavior, yet cross-cutting indicators of climate change perception reveal smaller scale relationships with migration behavior. Indeed, as shown in , significant correlations with household migration are in evidence across all but one indicator of climate perception. Of these, the perception of drought, soil problems, new animal species, and new plant species—all dimensions of climate whose perception is likely to be influenced by agricultural livelihoods—exhibit strong effects on the incidence of migration. Smaller but nevertheless significant relationships with temperature and rainfall also support the link between climate perception and migration incidence. This relationship is further supported by inferential analysis. Constructing an ordinal regression with the presence of migrants in the household as the independent variable and all nine significant climate perception indicators as dependent variables produces a model (χ2 = 124.4, p = 0.00) indicating a significant relationship between climate perception and migration. Given that this significant relationship is evident both within each of the three agro-ecological zones and across the data set as a whole, the data suggest that climate perceptions might offer a geographically cross-cutting piece of data with which to examine migration behavior in relation to climate change.

Table 5. Migrants and migration rates disaggregated by location

Table 6. Climate perception and household migration incidence

As shown in , for example, one finding of this approach is to oppose the contention (see Richards and Bradshaw Citation2017; Conway et al. Citation2019) that marginal groups are more likely to migrate than others, as a result of their inability to adapt in situ. Taking the most marginal, hyperprecarious migrants from each community—in the drought-prone east, those who migrate to beg; in the alluvial riverside regions, those who migrate to debt bondage; and in the Tonle Sap and lakeside zone, ethnic Vietnamese people who lack citizenship and thus migrate without documentation—the data indicate that marginal households in each of the three agro-ecological zones are not only less likely to migrate but also less likely to perceive changes in the climate. Given the strength of the relationship between climate perception and livelihoods demonstrated earlier, this might be due to marginal groups being less likely to possess the productive, predominantly agricultural assets (e.g., farmland or livestock) associated with greater sensitivity to climate change.

Discussion

Climate migration tends to be conceived, a priori, as an undesirable and unusual state of affairs. Both reflecting and shaping trends in governance and policy, public discourse, inclusive of the media, has characterized climate migration as a significant global problem in recent years. Described in the media as a “crisis” (Wernick Citation2019, 1) that will “unleash millions of global warming refugees” (Rowse Citation2018, 1), modeled estimates of up to 2 billion climate migrants by 2100 (Geisler and Currens Citation2017) reflect both widespread concern and a sense of the exceptionalism of the phenomenon. Indeed, the latter is exhibited in relation to the type as well as the extent of climate migration. It is frequently asserted in climate migration scholarship that those who migrate in response to the changing climate are likely to be the most vulnerable and marginal members of the community due to their limited ability to adapt in situ (Marino Citation2012; Stapleton et al. Citation2017; Conway et al. Citation2019). Moreover, this is an assertion that exists across multiple scales of climate migration analysis. Climate change, marginality, and migration are assumed to be linked at the national (Grecequet et al. Citation2017), community (Raleigh and Dowd Citation2018), household (Warner and Afifi Citation2014), and even intrahousehold (Jungehülsing Citation2010) scales. Policy efforts to manage, mitigate, or reduce the risks of climate migration are therefore often directed at stemming the untrammeled flow of those displaced by disaster: the “climate barbarians at the gate” (Bettini Citation2013, 63) whose very vulnerability casts them as a national security threat (K. A. Thomas and Warner Citation2019).

Policy perspectives of this sort derive in large part from top-down scholarship on the climate change–migration nexus (e.g., Myers Citation2002; Geisler and Currens Citation2017; World Bank Citation2018). Such top-down analyses continue to be dominated by large-scale Ricardian modeling of climate data against existing socioeconomic data sets, resulting in analysis showing relatively direct relationships between meteorological phenomena and human behavior (Falco, Donzelli, and Olper Citation2018). As the body of scholarship exploring the climate change–migration nexus grows, however, empirical evidence increasingly reveals “that environmental factors shape human migration patterns in combination with numerous other micro-, meso-, and macro-level contextual factors” (Hunter, Luna, and Norton Citation2015, 382). Subjective positionality and marginality shape the relationship between climate and migration (Clare et al. Citation2017; Vulturius et al. Citation2018), entangling environmental factors in a variety of other socioeconomic characteristics and processes, from age to gender to education. A tension has therefore arisen between bottom-up and top-down analysis of climate migration (Conway et al. Citation2019). Physical climate data indicate large-scale trends, whereas local behavior and impact analyses suggest far smaller and more complex effects rooted in subjective and contextually determined perceptions of the climate.

By presenting data on a range of climate change perception indicators, as reported by people engaged in a variety of livelihoods, this article has aimed to elucidate this complexity and add the aspect of livelihoods to analysis of the climate change–perception–migration nexus. As shown here, livelihoods structure not only the extent of climate perception but also how and which climatic changes are perceived. Those engaged in livelihoods that place a particular emphasis on certain aspects of the climate are more likely than others to notice changes in those aspects—even if they live in close proximity to each other. By extension, those engaged in certain livelihoods are more likely also to react to those changes. Livelihoods therefore play an active role in determining whether or not somebody perceives changes that may constrain or facilitate migration.

From this standpoint, the results question the common contention that climate change will hit the most marginal communities hardest, arguing that this statement requires greater nuance. Rather than enhancing perception and, by extension, experiences of the changing climate, marginality instead shapes these in specific ways. Indeed, marginality might overall diminish marginal populations’ sensitivity to the changing climate. This was highlighted by, first, the relationship between livelihoods and the type of changes to the climate perceived by respondents; second, marginal groups’ relatively low engagement in climatically sensitive primary livelihoods, due to their lack of assets and resources; and, third, the lower levels of migration observed among marginal than nonmarginal groups. Thus, the common explanation among migration scholars, that the most vulnerable lack the social and material resources to migrate, requires further analytical work. Rather than being highly vulnerable to the shifting environment but unable to adapt to it, socially marginalized groups appear in the results presented here to be less likely to perceive changes in their environment but—as shown in —similarly likely to have migrants in their households if they do so. This suggests that it is not only a lack of physical resources to migrate but also the social embeddedness of livelihoods shaping perception of the changing climate itself that might contribute to marginalized communities’ low rates of overall migration.

Despite problematizing dominant analytical approaches that seek to draw direct causal linkages between climate and population data, the aim here is not to undermine the importance of the role of climate change on migration patterns. Rather, it is a call to recognize the embeddedness of climate impacts within economic and social systems and the importance of the perceptions–livelihood nexus in shaping people’s experiences of climate change. Although the climate, as a statistical phenomenon, operates (in part) at a global scale, climate perceptions—and by extension climate impacts—are mediated locally by a broad milieu of social, economic and cultural factors. Simply put, climate change in the physical sense is a top-down phenomenon, whereas climate perceptions emerge from the bottom up. Given the issues related to the use of climate data as a predictor of migration, this is of key importance, offering the potential for locally gathered climate perception data to be used to produce more effective models of migration in a changing climate. Yet it is with further work that the greatest benefits of this position might be gleaned, with the compilation of larger scale data sets on climate perception having the potential to deepen our understanding of the extent to which correlations can be identified, and inferences drawn, between physical climate data and human behavior. Viewed thus, climate perception data have the potential not only to enhance understanding of climate mobility but, in doing so, to provide an epistemological bridge between competing scientific and social scientific ontologies of climate in the analysis of climate change impacts.

Conclusion

This article has sought to further understanding of the determinants and outcomes of climate change perception by exploring three aspects of the perception of the climate: first, the relationship of climate perceptions to geography and space; second the influence of livelihoods on climate change perception; and, third, the relationship between climate change perception and migration.

In relation to the first point, the results show that climate perception is not significantly influenced by spatial distance, with respondents living in close proximity reporting divergent or even opposite perceptions of various aspects of the climate. Crucially, the issue of scale is key here. Although larger scale analyses might indicate coherent differences in climate perception between agro-ecological zones, in many cases this coherence breaks down at smaller scales. This suggests that climate perceptions are influenced by factors other than climate, the influence of which is generally observed at a larger scale.

The second contribution of the article is to emphasize the role of livelihoods in shaping climate perceptions. The data here indicate that certain climate perceptions are significantly influenced by engagement in certain primary livelihoods. Farmers are more likely to observe changes in rainfall, for example, whereas fishers are more likely to observe changes in the wind. In contrast to Ricardian approaches, which assess the likelihood of responding to changes in the climate, therefore, this approach emphasizes instead the subjective nature of climate change perception.

Nevertheless, although the subjectivity of climate perceptions has generally been viewed as undermining their utility, this article demonstrates that they retain a potentially useful role in understanding behavior in response to the climate. Specifically, the article demonstrates the utility of climate perception data for understanding the relationship of climate perception to migration, outlining a statistically significant relationship between the presence of migrants in the household and nine out of ten climate change indicators. In addition, the data here consider the role of marginality on climate perceptions, concluding that marginality has a significant impact on the likelihood of perceiving climate change but not on the likelihood of having migrants in the household.

In broad terms, the article therefore offers two contributions to the literature on climate change and migration. First, it demonstrates that climate perception data constitute a useful means through which to understand the motivations and conditions that shape climate migration. Second, by demonstrating the subjective entanglement of climate perceptions—and thus responses—it problematizes efforts to draw direct correlations between physical climactic phenomena and human behavior. Further work should therefore be directed toward understanding the geographical and social distribution of climate perception, as a complementary lens through which to interpret the climate’s impacts.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Laurie Parsons

LAURIE PARSONS is British Academy Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the Department of Geography at Royal Holloway, University of London. E-mail: [email protected]. His work explores the contested politics of climate change through its impact on socioeconomic inequalities, patterns of work, and mobilities.

Jonas Østergaard Nielsen

JONAS ØSTERGAARD NIELSEN is Professor in Integrative Geography in the Department of Geography and the Integrative Research Institute on Transformations of Human–Environment Systems (IRI THESys), Humboldt University, Berlin, Germany. E-mail: [email protected]. His research covers human adaptation to climate change and the globalization of land use change.

References

- Assessment Capacities Project. 2011. Emergency capacity building project. Secondary data review: Cambodia. Geneva, Switzerland: Assessment Capacities Project.

- Adger, W. N., J. Barnett, K. Brown, N. Marshall, and K. O’Brien. 2013. Cultural dimensions of climate change impacts and adaptation. Nature Climate Change 3 (2):112–17. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1666.

- Akter, S., and J. Bennett. 2011. Household perceptions of climate change and preferences for mitigation action: The case of the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme in Australia. Climatic Change 109 (3–4):417–36. doi: 10.1007/s10584-011-0034-8.

- Amer, R. 2013. Domestic political change and ethnic minorities—A case study of the ethnic Vietnamese in Cambodia. Asia-Pacific Social Science Review 13 (2):87–101.

- Australian Bureau of Meteorology. 2007. About climate statistics. Accessed July 2, 2019. http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/cdo/about/about-stats.shtml.

- Bardsley, D. K., and G. J. Hugo. 2010. Migration and climate change: Examining thresholds of change to guide effective adaptation decision-making. Population and Environment 32 (2–3):238–62. doi: 10.1007/s11111-010-0126-9.

- Beazley, H., and M. Miller. 2015. The art of not been governed: Street children and youth in Siem Reap, Cambodia. In Politics, citizenship and rights, ed. K. Kallio, S. Mills, and T. Skelton, 1–22. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature.

- Berman, J. S. 1996. No place like home: Anti-Vietnamese discrimination and nationality in Cambodia. California Law Review 84 (3):817–74. doi: 10.2307/3480966.

- Berney, L. R., and D. B. Blane. 1997. Collecting retrospective data: Accuracy of recall after 50 years judged against historical records. Social Science & Medicine 45 (10):1519–25. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00088-9.

- Bettini, G. 2013. Climate barbarians at the gate? A critique of apocalyptic narratives on “climate refugees.” Geoforum 45:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.09.009.

- Black, R., S. R. Bennett, S. M. Thomas, and J. R. Beddington. 2011. Climate change: Migration as adaptation. Nature 478 (7370):447–49. doi: 10.1038/478477a.

- Boas, I. 2015. Climate migration and security: Securitisation as a strategy in climate change politics. London and New York: Routledge.

- Bylander, M. 2015. Depending on the sky: Environmental distress, migration, and coping in rural Cambodia. International Migration 53 (5):135–47. doi: 10.1111/imig.12087.

- Callo-Concha, D. 2018. Farmer perceptions and climate change adaptation in the West Africa Sudan savannah: Reality check in Dassari, Benin, and Dano, Burkina Faso. Climate 6 (2):44. doi: 10.3390/cli6020044.

- Canzutti, L. 2019. (Co-) producing liminality: Cambodia and Vietnam’s “shared custody” of the Vietnamese diaspora in Cambodia. Political Geography 71:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.02.005.

- Carmenta, R., A. Zabala, W. Daeli, and J. Phelps. 2017. Perceptions across scales of governance and the Indonesian peatland fires. Global Environmental Change 46:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.08.001.

- Chhinh, N., and A. Millington. 2015. Drought monitoring for rice production in Cambodia. Climate 3 (4):792–811. doi: 10.3390/cli3040792.

- Chu, E., and K. Michael. 2019. Recognition in urban climate justice: Marginality and exclusion of migrants in Indian cities. Environment and Urbanization 31 (1):139–56. doi: 10.1177/0956247818814449.

- Clare, A., R. Graber, L. Jones, and D. Conway. 2017. Subjective measures of climate resilience: What is the added value for policy and programming? Global Environmental Change 46:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.07.001.

- Conway, D., R. J. Nicholls, S. Brown, M. G. Tebboth, W. N. Adger, B. Ahmad, H. Biemans, et al. 2019. The need for bottom-up assessments of climate risks and adaptation in climate-sensitive regions. Nature Climate Change 9 (7):503–11. doi: 10.1038/s41558-019-0502-0.

- De Longueville, F., P. Ozer, F. Gemenne, S. Henry, O. Mertz, and J. Ø. Nielsen. 2020. Comparing climate change perceptions and meteorological data in rural West Africa to improve the understanding of household decisions to migrate. Climatic Change (160):1–19.

- De Nicola, F., and X. Giné. 2012. How accurate are recall data? Evidence from coastal India. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Deressa, T. T., R. M. Hassan, and C. Ringler. 2011. Perception of and adaptation to climate change by farmers in the Nile basin of Ethiopia. The Journal of Agricultural Science 149 (1):23–31. doi: 10.1017/S0021859610000687.

- D’haen, S. A. L., J. Ø. Nielsen, and E. F. Lambin. 2014. Beyond local climate: Rainfall variability as a determinant of household nonfarm activities in contemporary rural Burkina Faso. Climate and Development 6 (2):144–65. doi: 10.1080/17565529.2013.867246.

- Diepart, J.-C. 2015. Learning for social-ecological resilience: Conceptual overview and key findings in Diepart. Learning for resilience: Insights from Cambodia’s rural communities. Phnom Penh, Cambodia. The Learning Institute.

- Diggs, D. M. 1991. Drought experience and perception of climatic change among Great Plains farmers. Great Plains Research 1 (1):114–32.

- Ejembi, E. P., and G. B. Alfa. 2012. Perceptions of climate change in Africa: Regional agricultural perspectives. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences 2 (5):1–10.

- Eklund, L., C. Romankiewicz, M. Brandt, M. Doevenspeck, and C. Samimi. 2016. Data and methods in the environment–migration nexus: A scale perspective. DIE ERDE—Journal of the Geographical Society of Berlin 147 (2):139–52.

- European Space Agency. 2019. EO4SD: Earth Observation for Sustainable Development. Agriculture and rural development: Cambodia. Accessed March 27, 2020. http://eo4sd.esa.int/agriculture.

- Fadairo, O., P. A. Williams, and F. S. Nalwanga. 2019. Perceived livelihood impacts and adaptation of vegetable farmers to climate variability and change in selected sites from Ghana, Uganda and Nigeria. Environment, Development and Sustainability 1–19.

- Faist, T., and J. Schade. 2013. Disentangling migration and climate change: Methodologies, political discourses and human rights. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

- Falco, C., F. Donzelli, and A. Olper. 2018. Climate change, agriculture and migration: A survey. Sustainability 10 (5):1–21. doi: 10.3390/su10051405.

- Funatsu, B. M., V. Dubreuil, A. Racapé, N. S. Debortoli, S. Nasuti, and F. M. Le Tourneau. 2019. Perceptions of climate and climate change by Amazonian communities. Global Environmental Change 57:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.05.007.

- Funk, C., A. R. Sathyan, P. Winker, and L. Breuer. 2020. Changing climate–changing livelihood: Smallholder’s perceptions and adaption strategies. Journal of Environmental Management 259:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109702.

- Fussell, E., K. J. Curtis, and J. DeWaard. 2014. Recovery migration to the City of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina: A migration systems approach. Population and Environment 35 (3):305–22. doi: 10.1007/s11111-014-0204-5.

- Gbetibouo, G. A. (2009). Understanding farmers’ perceptions and adaptations to climate change and variability: The case of the Limpopo Basin, South Africa. International Food Policy Research Institute Discussion paper, No. 849. Accessed September 12, 2019. http://www.ifpri.org.

- Geisler, C., and B. Currens. 2017. Impediments to inland resettlement under conditions of accelerated sea level rise. Land Use Policy 66:322–30. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.03.029.

- Gesing, F., J. Herbeck, and S. Klepp. 2014. Denaturing climate change: Migration, mobilities and space. Artec Paper No. 200.

- Gómez, O. O. 2013. Climate change and migration. ISS Working Paper Series/General Series, 572.

- Grecequet, M., J. DeWaard, J. J. Hellmann, and G. J. Abel. 2017. Climate vulnerability and human migration in global perspective. Sustainability 9 (5):720. doi: 10.3390/su9050720.

- Gubler, S., S. Hunziker, M. Begert, M. Croci-Maspoli, T. Konzelmann, S. Brönnimann, C. Schwierz, C. Oria, and G. Rosas. 2017. The influence of station density on climate data homogenization. International Journal of Climatology 37 (13):4670–83. doi: 10.1002/joc.5114.

- Hageback, J., J. Sundberg, M. Ostwald, D. Chen, X. Yun, and P. Knutsson. 2005. Climate variability and land-use change in Danangou watershed, China—Examples of small-scale farmers’ adaptation. Climatic Change 72 (1–2):189–212. doi: 10.1007/s10584-005-5384-7.

- Hamid, M. 2019. In the 21st century, we are all migrants. National Geographic August:15–20.

- Hansen, J., M. Sato, and R. Ruedy. 2012. Perception of climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109 (37):E2415–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205276109.

- Hein, Y., K. Vijitsrikamol, W. Attavanich, and P. Janekarnkij. 2019. Do farmers perceive the trends of local climate variability accurately? An analysis of farmers’ perceptions and meteorological data in Myanmar. Climate 7 (5):1–21. doi: 10.3390/cli7050064.

- Hunter, L. M., J. K. Luna, and R. M. Norton. 2015. Environmental dimensions of migration. Annual Review of Sociology 41:377–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112223.

- International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and World Bank. 2015. Cambodian agriculture in transition: Opportunities and risks economic and sector work. Report No. 96308-KH, World Bank Press, Washington, DC.

- International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development. 2014. Poverty and vulnerability assessment—A survey instrument for the Hindu Kush Himalayas. Kathmandu, Nepal: International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development.

- International Organisation for Migration. 2019. Migration, climate change and the environment: A complex nexus. Accessed February 18, 2019. https://www.iom.int/complex-nexus.

- Ishaya, S., and I. B. Abaje. 2008. Indigenous people’s perception on climate change and adaptation strategies in Jema’a local government area of Kaduna State, Nigeria. Journal of Geography and Regional Planning 1 (8):138–43.

- Jacobson, J. 1988. Environmental refugees: A yardstick of habitability. Washington, DC: WorldWatch Institute.

- Jacobson, C., S. Crevello, C. Chea, and B. Jarihani. 2019. When is migration a maladaptive response to climate change?. Regional Environmental Change 19 (1):101–112.

- Jakobeit, C., and C. Methmann. 2012. Climate refugees as dawning catastrophe? A critique of the dominant quest for numbers. In Climate change, human security and violent conflict, ed. H. Brach, J. Scheffran, and M. Brzoska, 301–14. Berlin: Springer.

- Jamero, M. L., M. Onuki, M. Esteban, X. K. Billones-Sensano, N. Tan, A. Nellas, T. Hiroshi, G. T. Nguyen, and V. P. Valenzuela. 2017. Small-island communities in the Philippines prefer local measures to relocation in response to sea-level rise. Nature Climate Change 7 (8):581–86. doi: 10.1038/nclimate3344.

- Johnson, L., and C. Rampini. 2017. Are climate models global public goods? In Routledge handbook of the political economy of science, ed. D. Tyfield, R. Lave, S. Randalls, and C. Thorpe. pp. 263–274. London and New York: Routledge.

- Jungehülsing, J. 2010. Women who go, women who stay: Reactions to climate change. A case study on migration and gender in Chiapas, Mexico. Washington, DC: Heinrich Böll Stiftung.

- Karki, S., P. Burton, and B. Mackey. 2020. The experiences and perceptions of farmers about the impacts of climate change and variability on crop production: a review. Climate and Development 12 (1):80–95.

- Kelman, I., J. Orlowska, H. Upadhyay, R. Stojanov, C. Webersik, A. Simonelli, D. Procházka, and D. Němec. 2019. Does climate change influence people’s migration decisions in Maldives? Climatic Change 153 (1–2):285–99. doi: 10.1007/s10584-019-02376-y.

- Khut, C. 2017. Statement to COP23 By His Excellency Khut Chandara, Head of the Cambodian Delegation, Under Secretary of State, Ministry of Environment Bonn, Germany, November 2017. Accessed on 07/10 at https://unfccc.int/.

- Klepp, S. 2017. Climate change and migration. In Oxford Research encyclopaedia of climate science. ed. Hans von Storch. 1–35. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Kolawole, O. D., M. R. Motsholapheko, B. N. Ngwenya, O. Thakadu, G. Mmopelwa, and D. L. Kgathi. 2016. Climate variability and rural livelihoods: How households perceive and adapt to climatic shocks in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Weather, Climate, and Society 8 (2):131–45. doi: 10.1175/WCAS-D-15-0019.1.

- Kreft, S., D. Eckstein, L. Junghans, C. Kerestan, and U. Hagen. 2014. Global climate risk index 2015. Bonn: Germanwatch.

- Kreft, S., D. Eckstein, L. Junghans, C. Kerestan, and U. Hagen. 2014. Global climate risk index 2015: Who suffers most from extreme weather events? Weather-related loss events in 2013 and 1994 to 2013. Berlin: Germanwatch.

- Kretsedemas, P., J. Capetillo-Ponce, and G. Jacobs, eds. 2013. Migrant marginality: A transnational perspective. London and New York: Routledge.

- Leiserowitz, A. 2010. Climate change risk perceptions and behavior in the United States, in S. Schneider, A. Rosencranz, and M. Mastrandrea, eds. Climate Change Science and Policy. Washington DC: Island Press.

- Liese, B., S. Isvilalonda, K. Nguyen Tri, L. Nguyen Ngoc, P. Pananurak, R. Pech, et al. 2014. Economics of southeast asian rice production agri-benchmark working. Paper 2014/1 accessed at http://www.agribenchmark.org/fileadmin/Dateiablage/B-CashCrop/Reports/Report-2014-1-rice-FAO.pdf.

- Macchi, M.,. A. M. Gurung, and B. Hoermann. 2015. Community perceptions and responses to climate variability and change in the Himalayas. Climate and Development 7 (5):414–25. doi: 10.1080/17565529.2014.966046.

- Maddison, D. 2007. The perception of and adaptation to climate change in Africa. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Marino, E. 2012. The long history of environmental migration: Assessing vulnerability construction and obstacles to successful relocation in Shishmaref, Alaska. Global Environmental Change 22 (2):374–81. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.09.016.

- McCarthy, J., C. Chen, D. López-Carr, and B. L. E. Walker. 2014. Socio-cultural dimensions of climate change: Charting the terrain. GeoJournal 79 (6):665–75. doi: 10.1007/s10708-014-9546-x.

- McLeman, R. A., and L. M. Hunter. 2010. Migration in the context of vulnerability and adaptation to climate change: Insights from analogues. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Climate Change 1 (3):450–61. doi: 10.1002/wcc.51.

- Mekonnen, M. M., and A. Y. Hoekstra. 2011. The green, blue and grey water footprint of crops and derived crop products. Hydrology & Earth System Sciences Discussions 8 (1):763–809.

- Mertz, O., C. Mbow, A. Reenberg, and A. Diouf. 2009. Farmers’ perceptions of climate change and agricultural adaptation strategies in rural Sahel. Environmental Management 43 (5):804–16. doi: 10.1007/s00267-008-9197-0.

- Messerli, P., A. Peeters, O. Schoenweger, V. Nanhthavong, and A. Heinimann. 2015. Marginal land or marginal people? Analysing patterns and processes of large-scale land acquisitions in South-East Asia. In Large-scale land acquisitions: Focus on South-East Asia, ed. C. Gironde, C. Golay, and P. Messerli, 136–71. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Meyer, B. 2016. Climate migration and the politics of causal attribution: A case study in Mongolia. Migration and Development 5 (2):234–53.

- Migrating Out of Poverty Program. 2013. Household questionnaire (migrant). Accessed January 15, 2017. http://migratingoutofpoverty.dfid.gov.uk/.

- Misra, T. 2018. On weaponising migration. Accessed February 14, 2019. http://www.citylab.com.

- Mortreux, C., and J. Barnett. 2009. Climate change, migration and adaptation in Funafuti, Tuvalu. Global Environmental Change 19 (1):105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.09.006.

- Myers, N. 1997. Environmental refugees. Population and Environment 19 (2):167–82. doi: 10.1023/A:1024623431924.

- Myers, N. 2002. Environmental refugees: A growing phenomenon of the 21st century. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 357 (1420):609–13. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0953.

- Nicholson, C. T. 2014. Climate change and the politics of causal reasoning: The case of climate change and migration. The Geographical Journal 180 (2):151–60. doi: 10.1111/geoj.12062.

- Nielsen, J. Ø., and A. Reenberg. 2010. Cultural barriers to climate change adaptation: A case study from Northern Burkina Faso. Global Environmental Change 20 (1):142–52. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.10.002.

- O’Brien, K. 2013. Global environmental change III: Closing the gap between knowledge and action. Progress in Human Geography 37 (4):587–96. doi: 10.1177/0309132512469589.

- Oudry, G., K. Pak, and C. Chea. 2016. Assessing vulnerabilities and responses to environmental changes in Cambodia. Phnom Penh, Cambodia: International Organization for Migration.

- Overpeck, J. T., G. A. Meehl, S. Bony, and D. R. Easterling. 2011. Climate data challenges in the 21st century. Science 331 (6018):700–702. doi: 10.1126/science.1197869.

- Panda, A. 2017. Vulnerability to climate variability and drought among small and marginal farmers: A case study in Odisha, India. Climate and Development 9 (7):605–17. doi: 10.1080/17565529.2016.1184606.

- Parsons, L. 2019. Structuring the emotional landscape of climate change migration: Towards climate mobilities in geography. Progress in Human Geography 43 (4):670–90. doi: 10.1177/0309132518781011.

- Parsons, L., and S. Chann. 2019. Mobilising hydrosocial power: Climate perception, migration and the small scale geography of water in Cambodia. Political Geography 75:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.102055.

- Parsons, L., and S. Lawreniuk. 2018. Seeing like the stateless: Documentation and the mobilities of liminal citizenship in Cambodia. Political Geography 62:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.09.016.

- Piguet, E., A. Pécoud, P. de Guchteneire, and P. F. Guchteneire, eds. 2011. Migration and climate change. London: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1093/rsq/hdr006.

- Raleigh, C., and C. Dowd. 2018. Political environments, elite co-option, and conflict. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108 (6):1668–84. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2018.1459459.

- Rankoana, S. A. 2018. Human perception of climate change. Weather 73 (11):367–70. doi: 10.1002/wea.3204.

- Richards, J. A., and S. Bradshaw. 2017. Uprooted by climate change: Responding to the growing risk of displacement. London: Oxfam International.

- Rowse, M. 2018. Climate change must be dealt with before it unleashes millions of global warming refugees. South China Morning Post. Accessed June 27, 2019. https://www.scmp.com.

- Semenza, J. C., D. E. Hall, D. J. Wilson, B. D. Bontempo, D. J. Sailor, and L. A. George. 2008. Public perception of climate change: Voluntary mitigation and barriers to behavior change. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 35 (5):479–87. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.020.

- Shrestha, R. P., N. Raut, L. M. M. Swe, and T. Tieng. 2018. Climate change adaptation strategies in agriculture: Cases from southeast Asia. Sustainable Agriculture Research, 7 (526-2020-482):39–51.

- Skeldon, R. 2002. Migration and poverty. Asia-Pacific Population Journal 17 (4):67–82. doi: 10.18356/7c0e3452-en.

- Slegers, M. F. W. 2008. If only it would rain: Farmers’ perceptions of rainfall and drought in semi-arid central Tanzania. Journal of Arid Environments 72 (11):2106–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jaridenv.2008.06.011.

- Smith, W. J., Jr., Z. Liu, A. S. Safi, and K. Chief. 2014. Climate change perception, observation and policy support in rural Nevada: A comparative analysis of Native Americans, non-native ranchers and farmers and mainstream America. Environmental Science & Policy 42:101–22. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2014.03.007.

- Sperfeldt, C. 2017. Report on citizenship law: Cambodia. Italy: European University Institute.

- Springer, S. 2017. Homelessness in Cambodia: The terror of gentrification. In The handbook of contemporary Cambodia, ed. K. Brickell and S. Springer. 234–244. London and New York: Routledge.

- Stapleton, S. O., R. Nadin, C. Watson, and J. Kellett. 2017. Climate change, migration and displacement: The need for a risk-informed and coherent approach. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Stark, O., and D. E. Bloom. 1985. The new economics of labour migration. The American Economic Review 75 (2):173–78.

- Stern, N. 2007. The economics of climate change: The Stern review. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Stojanov, R., B. Duží, I. Kelman, D. Němec, and D. Procházka. 2017. Local perceptions of climate change impacts and migration patterns in Malé. The Geographical Journal 183 (4):370–85. doi: 10.1111/geoj.12177.

- Thoeun, H. C. 2015. Observed and projected changes in temperature and rainfall in Cambodia. Weather and Climate Extremes 7:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.wace.2015.02.001.

- Thomas, D. S., C. Twyman, H. Osbahr, and B. Hewitson. 2007. Adaptation to climate change and variability: Farmer responses to intra-seasonal precipitation trends in South Africa. Climatic Change 83 (3):301–22. doi: 10.1007/s10584-006-9205-4.

- Thomas, K. A., and B. P. Warner. 2019. Weaponizing vulnerability to climate change. Global Environmental Change 57:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.101928.

- Turney, C. 2019. Sydney declares a climate emergency—What does that mean in practice? Accessed June 2, 2019. http://theconversation.com.

- Uk, S., C. Yoshimura, S. Siev, S. Try, H. Yang, C. Oeurng, L. Shangshang, and S. Hul. 2018. Tonle Sap Lake: Current status and important research directions for environmental management. Lakes & Reservoirs: Research & Management 23 (3):177–89. doi: 10.1111/lre.12222.

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. 2010. Strengthening of hydrometeorological services in southeast Asia: Country report for Cambodia. Phnom Penh, Cambodia: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. 2018. Overview of Internal Migration in Cambodia. Bangkok: UNESCO.

- Vance, W. H., R. W. Bell, and V. Seng. 2004. Rainfall analysis for the provinces of Battambang, Kampong Cham and Takeo, the Kingdom of Cambodia. Unpublished paper. School of Environmental Science, Murdock University, Victoria, Australia.

- Vedwan, N., and R. E. Rhoades. 2001. Climate change in the Western Himalayas of India: A study of local perception and response. Climate Research 19 (2):109–17. doi: 10.3354/cr019109.

- Von Braun, J., and F. W. Gatzweiler. 2014. Marginality: Addressing the nexus of poverty, exclusion and ecology. Berlin: Springer.

- Vulturius, G., K. André, ˚A. G. Swartling, C. Brown, M. D. Rounsevell, and V. Blanco. 2018. The relative importance of subjective and structural factors for individual adaptation to climate change by forest owners in Sweden. Regional Environmental Change 18 (2):511–20. doi: 10.1007/s10113-017-1218-1.

- Wahlberg, A. A., and L. Sjoberg. 2000 Risk Perception and the Media. Journal of Risk Research 3: 31–50.

- Warner, K., M. Hamza, A. Oliver-Smith, F. Renaud, & A. Julca. 2010. Climate change, environmental degradation and migration. Natural Hazards 55 (3):689–715.

- Warner, K., and T. Afifi. 2014. Where the rain falls: Evidence from 8 countries on how vulnerable households use migration to manage the risk of rainfall variability and food insecurity. Climate and Development 6 (1):1–17. doi: 10.1080/17565529.2013.835707.

- Weber, E. U. 2010. What shapes perceptions of climate change? Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 1 (3):332–42. doi: 10.1002/wcc.41.

- Wernick, A. 2019. A climate migration crisis is escalating in Bangladesh. Accessed June 27, 2019. http://www.pri.org.

- White, G. 2012. The “securitization” of climate-induced migration. In Global migration: Challenges in the twenty first century, ed. K. Khory. 13–33. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Whitmarsh, L., and S. Capstick. 2018. Perceptions of climate change. In Psychology and climate change: Human perceptions, impacts, and responses, ed. S. Clayton and C. Manning 13–33. London: Academic Press.

- World Bank. 2018. Groundswell: Preparing for internal climate migration. Washington, DC: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/World Bank.

- Zander, K. K., L. Petheram, and S. T. Garnett. 2013. Stay or leave? Potential climate change adaptation strategies among Aboriginal people in coastal communities in northern Australia. Natural Hazards 67 (2):591–609. doi: 10.1007/s11069-013-0591-4.

- Zander, K. K., C. Richerzhagen, and S. T. Garnett. 2019. Human mobility intentions in response to heat in urban South East Asia. Global Environmental Change 56:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.03.004.

- Žurovec, O., and P. O. Vedeld. 2019. Rural livelihoods and climate change adaptation in laggard transitional economies: A case from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sustainability 11 (21):1–27. doi: 10.3390/su11216079.