Abstract

Chinese were first imported to the Mississippi Delta1 as the solution to the shortage of Black laborers and the maintenance of the plantation system after the Civil War. As foreigners and people of color, the Delta Chinese found the economic niche of grocery stores in the Jim Crow South. Simultaneously concentrated and scattered around the Delta region, these grocery stores served as multiscalar, multiracial, and multifunctional space triangulated between White and Black, not only as one of the most racially mingled spaces in the Jim Crow South but also as a space for self-mobilization and cultural preservation. By examining the Chinese experiences and Chinese grocery stores in the Mississippi Delta during the Jim Crow Era through a multiscalar lens, this article attempts to incorporate space/place/scale2 into racial triangulation theory. Racial formation is both relational and spatial. Space/place/scale are not only axes of racialization but also constituted, produced, and transformed by historical, socioeconomic, and political processes of racialization and racial formation. The Chinese experience between Black and White exemplifies the power of human agency in rescaling the hegemony of White supremacy through the making of place and identity. This article also echoes with Black geographies and calls for the geographies of non-Whiteness that cross-examine multiracial relationships and advocate for cross-racial solidarity against racism and White supremacy.

美国密西西比三角洲早在美国内战后就引进了中国人,旨在解决黑人劳动力短缺的问题和维持种植园制度。作为外国人和有色人种,三角洲华人在种族歧视的南方发现了杂货店这个经济商机。这些杂货店集中分布的同时,也分散在整个三角洲地区,形成一个多尺度、多种族、多功能的空间,与白人和黑人共同组成了三角关系。这不仅是种族歧视的南方地区种族最混杂的空间,也是一个自我动员和文化保护的空间。本文从多尺度的角度,考察了种族歧视时代密西西比三角洲的华人经历和华人杂货店。本文试图将空间/地点/尺度纳入种族三角互证理论。种族形成既有关联上的、也有空间上的特点。空间/地点/尺度不仅是种族化的坐标轴,其形成、产生和转化也源自种族化和种族形成的历史、社会经济和政治过程。中国人与黑人和白人的经历,体现了人类的能动性,通过塑造位置和身份去重新配置白人霸权。这篇文章也呼应了黑人地理学,并呼吁非白人地理学,探讨多种族关系,主张跨种族的团结,反对种族主义和白人至上。

Los chinos fueron traídos primero al Delta del Mississippi para solucionar la escasez de trabajadores negros y para el mantenimiento del sistema de plantación, después de la Guerra Civil. Como extranjeros, y además gente de color, los chinos del Delta encontraron ubicación en el nicho económico de las tiendas de abarrotes del Sur de Jim Crow. Al mismo tiempo concentradas y dispersas alrededor de la región del Delta, estas tiendas sirvieron como un espacio triangulado multiescalar, multirracial y multifuncional entre negros y blancos, no solo como uno de los espacios más racialmente entremezclado en el Sur de Jim Crow, sino también como un espacio de auto- movilización y preservación cultural. Al examinar las experiencias chinas y las tiendas de abarrotes chinas en el Delta del Mississippi durante la Era de Jim Crow, a través de una lente multiescalar, este artículo intenta incorporar espacio/lugar/escala en la teoría de triangulación racial. La formación racial es a la vez relacional y espacial. Espacio/lugar/escala no son solo ejes de la racialización, sino están también constituidos, producidos y transformados por procesos históricos, socioeconómicos y políticos de racialización y de formación racial. La experiencia china entre el negro y el blanco ejemplifica el poder de la agencia humana para re-escalar la hegemonía de la supremacía blanca por medio de la construcción de lugar e identidad. Este artículo hace también eco a las geografías negras y hace un llamado por las geografías de la no blancura que reexaminan las relaciones multirraciales y abogan por una solidaridad interracial contra el racismo y la supremacía blanca.

Well, cotton used to be king, and that’s one reason the Chinese made it to the South, because, you know, everybody said they’re going to Gam Sahn [Gold Mountain], but then down in Mississippi it was called Men Fah Sahn [Cotton Mountain] because of cotton.

—Female, age eighty-three, Boyle, Mississippi

The rich alluvial soil of the Mississippi Delta and its proximity to the national and global market via the Mississippi River gave birth to the system of cotton plantations, which was founded on slavery and White supremacy and still permeates into the present and the future (Woods Citation2017). Both the stories about the racial relations in the American South between White and Black and the history of the Chinese immigrants originating from the “Golden Mountain” on the West Coast have been well told. Less well known is the “Cotton Mountain” that attracted Chinese immigrants to the American South (Loewen Citation1988). Thus, this research attempts to narrate the Chinese experience in the Delta and disrupt the bifurcated White–Black framework in the American South by spatializing racial triangulation theory and triangulating race and space/place/scale. What were the sociospatial and political contexts of the emergence of the Chinese grocery stores in the Delta? What were the Chinese experiences between Black and White in the Jim Crow South? What were the strategies of survival and resistance against racialization? More important, what were the roles of space/place/scale not only as manifestations of but also as axes of power in shaping the Chinese experiences in the Delta? By anchoring within the framework of race and space/place/scale, this article aims to contribute to Asian American studies, Black geographies, and the geographies of the American South.

Racial triangulation theory was among the first attempts to conceptualize racial relations beyond the White and Black binary paradigm (C. J. Kim Citation1999). Space/place/scale are not only the manifestation of racial relations but also axes of power (Delaney Citation2002). Although the racial triangulation theory expanded the single-dimensional racial stratification into two dimensions by adding the axis of insider–outsider, the studies based on the racial triangulation framework have rarely incorporated space/place/scale. The research on race–space relations has neglected the linkage between immigration and race and largely focused on the Black and White dichotomy (Liu Citation2000; Lai Citation2012). Thus, adding space/place/scale to the racial triangulation theory is critical in not only complicating the White–Black narrative but also expanding the understanding of the relationships between race and space/place/scale.

This research draws on interviews, fieldwork, and archival research (historical museums, the Delta Chinese families, city directories, and the online archives of local newspapers) conducted between 2016 and 2019 in the Delta. Almost all major cities and towns where Chinese grocery stores were located were visited, photographed, and mapped. On most of the field trips I was accompanied by Delta Chinese informants. Twenty-nine interviews were conducted about the Chinese experience in the South (including nine driving interviews, where the interviewees drove with me in different cities and towns and identified the Chinese grocery stores while recollecting their memories and experiences). Additionally, fifty-seven interviews archived by the Mississippi Delta Chinese Heritage Museum (Cleveland, Mississippi) were used. Also, many families generously shared their family books, letters, photographs, and other relevant materials and objects to illustrate their experiences. To protect the interviewees’ confidentiality, the names of the informants have been omitted from the interview quotes used in this article.

As a transplant myself, who grew up in China, I have lived in the United States for ten years, most recently in the American South for five years. I entered this subject matter as an outsider. Being an outsider offered me a fresh lens through which I learned, documented, and contextualized, rather than assumed. Throughout the project I made connections with many of my interviewees who have become my friends. They generously shared their culture, memories, and family stories. Over my five years living in the South as a Chinese and four years of conducting this research, I have gradually grown toward being an insider. Occupying the space of in-betweenness of insider–outsider provides me with access to rich narratives and resources for this project while allowing me to maintain a balance between objectivity and subjectivity. For many, the American South might seem like a place in the past. For the Delta Chinese, though, the South is a lived place, past and present. Most of my interviewees still live in the area. Some moved away for years and decided to come back; some moved away for good but have families in the South. Those who moved away still come back frequently for reunions and homecomings. Much of the South has changed: Stores closed or are gone, street names have changed, neighborhoods have shifted, and people have moved away. These changes posed certain challenges for the project, primarily in the identification of the store locations and street names. Drawing from multiple sources for data triangulation and verification helped address this issue, however. On some occasions, multiple interviewees were asked the same question or took me on a tour of the study area for the purpose of verification. Despite changes in the Delta, much has remained the same. Racial disparity and segregation still haunt the South, and so does the racial positioning of Chinese between White and Black. Place is multiple, complex, and evolving, and so is the people–place relationship. This research does not aim to provide an exhaustive description of the Delta, which is an impossible task to accomplish, but rather to faithfully document the lived experiences of its people within a specific time and space, as well as to contextualize this particular piece of story within the broader histories and geographies of the South.

This article is structured as follows. First, I contextualize this research within the literature about space/place/scale and race, the racial triangulation theory and its applications, as well as the blossoming studies about the American South and Black geographies. I then detail the spatial distribution and differentiation of Chinese grocery stores at the regional scale, followed by the embodied experience of Chinese between White and Black at the individual scale, both of which contribute to the place-making of the Chinese grocery stores at the local scale. Further, I examine the decline of the Chinese grocery stores that resulted from a combination of historical, socioeconomic, cultural, and geographical factors. Finally, this article concludes with the meaning of being a Delta Chinese American, not only as a racial or ethnic identity but also as a place identity.

Literature Review

Scaling Race and Space (Place)

How does the racial formation shape space, give meanings to places, and condition the experience of embodied subjects emplaced in and moving through the material world?

—Delaney (Citation2002, 7)

Racialization and spatialization are mutually constructed and reinforced. Both are axes of power, processes, and consequences of each other (Anderson Citation1987; Delaney Citation1998, Citation2002; McKittrick Citation2000; Pulido Citation2000; Schein Citation2006; Lipsitz Citation2007, Citation2011; Shabazz Citation2015; Hawthorne Citation2019; Wright Citation2021). Racialization is not only manifest in the formation of space and place but also further perpetuated and reproduced by space and place, whether plantations, prisons, Chinatowns, Black ghettos, Japanese internment camps, or Native American reservations. As Gilmore (Citation2002) argued, “The territoriality of power is key to understanding race” (22). The tripling of power, difference, and space is the recipe for the social construction of space and race. Racial hierarchy and boundaries are not only social, ideological, and metaphorical but also materialized in the physical world. Thus, racialization is also a spatial process, and spatialization perpetuates racism and alienation. For example, Chinatown suggests an exoticized and imagined space constructed out of the Western racial ideology (Anderson Citation1987). It is a spatial symbol of yellow peril, inferiority, and unlawfulness. The spatial construction of Chinatown further institutionalizes the racialization of Chinese people.

Racial formation is manifest spatially across different scales, ranging from bodies, home, schools, and churches to cities, nation-states, and transnationalism (Gilbert Citation1998; Kobayashi and Peake Citation2000; Marston Citation2000; McKittrick Citation2000; Delaney Citation2002; Gilmore Citation2002; Woods Citation2002; Pulido Citation2016). These spatial manifestations of race at various scales are differentiated and relational. Along with the space and race, scale should be understood as socially constructed, both as an outcome and as a force of sociopolitical relations (Smith Citation1992; Howitt Citation1998; Marston Citation2000; Delaney Citation2002). In studying the environmental racism in Los Angeles through the framework of White privilege, Pulido (Citation2000) argued that scale must be recognized as a social process rather than simply the unit of analysis: “Not only must our analysis operate at several scales simultaneously, but we must also consider the functional role of those places and their interconnections” (20). Similarly, in the study of place-naming of Black spaces, Alderman (Citation2003) argued that scaling is not a static but rather a contested process shaping the spatial politics of commemoration (Alderman Citation2003). Thus, scale is not just a methodological reference within which the relationship between race and space is analyzed and interpreted but also part of the dynamic and relational processes of racialization and spatialization. These processes at various scales need to be examined relationally and simultaneously.

Yet, the role of scale in racialization, racial identification, and place-making deserves more attention. The research about race, space, and scale has been largely focused on how the forces at the macroscale (e.g., globalization, capitalism, nation-state, labor markets) shape the experiences and identities at the microscale. Individuals and communities are not just passive recipients of hegemony, however, but human agencies of survival, resistance, and rescaling against the social structure, largely through self-identification and place-making, such as homes, churches, communities, organizations, and individuals (hooks Citation1990; Gilbert Citation1998; Alderman Citation2003; Lipsitz Citation2011; Woods Citation2017). The (re)making of place from below through engagement, emplacement, and empowerment in the face of territoriality and exclusion from above (Cox Citation1998; Marston Citation2000; Nielsen and Simonsen Citation2003; Cidell Citation2006) is referred to by Smith (Citation1992) as “jumping scale” in his study of homelessness. Woods’s (Citation2017) blues epistemology depicted a vivid example of rescaling in which everyday Black experiences were documented and celebrated through blues as the space of survival and resistance under the violent plantation system. Similarly, Lipsitz (Citation2011) argued that whereas the “white spatial imaginaries” materialized White privilege and racism into spatial exclusivity and segregation, “black spatial imaginaries” gave rise to spatial practices of empowerment and place-making. Black geographies center around Black sense of place in the exploration of its connections with the multiscalar sociopolitical structures (McKittrick Citation2000, Citation2011; Eaves Citation2017; Harris and Hyden Citation2017). Similarly, the landscape of Asian American resistance against racism and alienation ranges from the poems carved on the walls of Angel Island Immigration Station during the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, to the emergence of ethnoburb and ethnopolis that challenge the racialization and stigmatization of Asian American “ghettos,” to the numerous fights for Asian American civil rights in the Jim Crow South (Laquerre Citation2000; Hoskins Citation2006; Li Citation2009; Hinnershitz Citation2017). Although it is important to understand the hierarchical nature of scale and how the power imbalance leads to the landscape of racial inequality, it is equally crucial, if not more, to unpack the complex, relational, and dynamic nature of scale as both individuals and communities are actively engaged in creating the spaces of mobilization and humanity.

Moreover, these spaces and strategies of resistance, survival, and identification are placed, diversified, and multiscalar due to the differentiated processes of racialization, localization, and intersectionality (Bonnett Citation1996, Citation1997; Kobayashi and Peake Citation2000; Wilson Citation2002; Bailey and Shabazz Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Bledsoe and Wright Citation2019; Hawthorne Citation2019). Bledsoe and Wright (Citation2019) called for the “pluralities of Black Geographies” to recognize the multiplicity of Black experiences and activism. Similarly, the experiences of Asian American are heterogeneous and spatially diversified. In her research on a multiracial neighborhood in suburban Los Angeles, Cheng (Citation2013) conceptualized regional racial formation by arguing that racial identities are spatially differentiated. The national racial ideology does not always translate into the local hierarchy, because smaller scale contexts, such as regions and neighborhoods, complicate and disrupt the national racial discourse and thus create uneven racial landscapes. Thus, the antiracist struggles and strategies are situated and need to be understood in place. As Kobayashi and Peake (Citation2000) argued, “Strategies of resistance are also diverse, they are expressed through distinctive racialized identities and take many forms that may range from everyday cultural practices to political movements, and may cover the ideological spectrum” (398). One of many examples of the distinctive and placed antiracist struggles are the Chinese grocery stores across the Jim Crow South.

A major task for geographers of race is to recognize and examine the plural racial experiences due to sociospatial processes at various scales. Although there are similarities among Chinese Americans based on a shared racial history and identity, these experiences are placed and diversified. Even within the locality of Mississippi Delta, the Chinese experience varies across cities, towns, and rural areas. Therefore, this research acknowledges the heterogeneity of Chinese experience in the South and grounds the study of race in place and scale, by simultaneously examining the racialization processes at the national, regional, local, and individual scales.

Racial Triangulation

Yellow is a shade of black, and black, a shade of yellow.

—Okihiro (Citation1994, 34)

Numerous scholars have challenged and extended the bifurcated White–Black paradigm by positioning Asian Americans in the structure of racial hierarchy (Okihiro Citation1994; Omi and Winant Citation1994; C. J. Kim Citation1999; Wu Citation2002; Ancheta Citation2006). Some scholars elaborated on the social construction of Asian Americans as a strategy to transfer White and non-White tensions to Black and Asian tensions to conceal structural racism and White supremacy, as is seen in the replacement of Black slaves with Chinese coolies, the construction of a model minority, the backlash against affirmative action, and the manufactured conflicts between Blacks and Koreans during the 1992 Los Angeles riots (Okihiro Citation1994; Park Citation1996; C. J. Kim Citation1999; J. Y. Kim Citation1999; Wu Citation2002; Ancheta Citation2006). Wu (Citation2002) stated that instead of the White–Black paradigm, the racial hierarchy in the U.S. social and legal system is featured with Whites, Blacks, honorary Whites, and constructive Blacks. In answering the question “Is Yellow Black or White?” Okihiro (1994) recounted the shared histories between Asian and African Americans of enslavement and subordination under the system of White supremacy and the global network of labor and capitalism. Ancheta (Citation2006) echoed Okihiro in stating that Asian Americans are primarily treated as constructive Blacks due to the shared experiences of racial violence and civil rights protections. Taylor (Citation1991) examined the complex interracial relationships between Blacks and Japanese in the pre–World War II Seattle characterized by competition, tolerance, and solidarity. Both groups experienced similar discriminations and ostracism, yet sought mobility via different approaches: Japanese Americans through entrepreneurship and education, African Americans through protests and political movements. Harden (Citation2003) described the Japanese American experience in Black and White Chicago as “double crossing,” meaning that the Japanese Americans occupy an in-between racial space of non-Black (not to be seen as a problem) and non-White (discrimination and ostracism). The Japanese–Black relationship was portrayed as antagonistic by the government and media, which damaged the potentiality of Japanese–Black coalition and boundary crossing. These literatures shared the concerns about insufficiency of the White–Black dichotomy in racial theory and looked beyond the cultural lens into the economic, social, legal, and political structure in understanding racial differences and relationships. Yet, despite numerous literatures that discuss Asian–Black relationships, very few works focus on the American South, a region that has long been framed under the bifurcated White–Black paradigm (Loewen Citation1988; Jung Citation2006; Bow Citation2010).

Among the attempts to fit Asian Americans in the White–Black racial history in the United States, C. J. Kim’s (Citation1999) racial triangulation theory began to conceptualize a nonbinary racial relation. Racial triangulation theory argues that the racialization processes of Asians and Blacks are not separate but mutually constitutive of one another. These processes result from the conjunction of two axes of power in force: “relative valorization” (superior/inferior) and “civic ostracism” (insider/foreigner). Asian Americans are kept in their racial positions via the triangulation of these two dimensions: superior (colorism) but alien (nativism) compared to Blacks. These two forces are inextricably connected in the maintenance of White supremacy and privileges. Racial triangulation theory also explains the construction of Asian Americans as both perpetual foreigner and model minority, as well as the differentiated attitudes toward Asian Americans by Whites and Blacks (Xu and Lee Citation2013). The anti-Asian violence in the United States results from a combination of nativism (un-American) and racism (non-White; Ancheta Citation2006), which caused the killing of Vincent Chin in 1982 in Detroit. Chin, a Chinese American, was mistaken as a Japanese native amidst the hatred toward the Japanese rise in the automobile industry. The coupling of colorism and nativism still haunts Asian Americans today, as increasing incidents of anti-Asian violence have been reported since the COVID-19 pandemic started in early 2020. Racial triangulation theory applies not only for Asian Americans but also for the racial and ethnic groups that are positioned in between Black and White, such as Native Americans, Latinx, and various non-White immigrant groups (C. J. Kim Citation1999).

The studies based on a racial triangulation framework seldom consider space/place/scale. As was previously mentioned, the research on race and space/place/scale largely focused on the binary White–Black relationships. Lai’s (Citation2012) work on urban renewal in San Francisco’s Japantown was groundbreaking for spatializing racial triangulation theory. Lai also emphasized the importance of scale in the formation of Japantown where Japanese Americans and African Americans coexisted after World War II. At the cross-national scale, the urban redevelopment of Japantown resulted from the rescaling of the Cold War economy, the geopolitics between the United States and Asia, and transnational connections with Japan. At the state level, the colorblind racial approach and the construction of the model minority at the expense of African Americans fueled the construction of Japantown. At the urban scale, the economic restructuring in postindustrial San Francisco capitalized on multiculturalism in the making of the global city. Unfortunately, the shared history of racialization and segregation between Asian Americans and African Americans does not necessarily lead to economic codependence or political alliance and solidarity (Lai Citation2012).

In many ways, the Chinese–Black relationship in the South resembles the Japanese–Black relationship in San Francisco. The emergence of Chinese grocery stores in the American South also resulted from the spatialization of racial triangulation. Chinese American experiences differ from Japanese American experiences, however. The Delta is not San Francisco. More important, whereas Japantown was constructed from above to racialize and exoticize Asian Americans at the expense of African Americans, Chinese grocery stores were built from below as a space of coexistence and codependence with Blacks in the face of the segregation and alienation in the Jim Crow South.

By studying the Chinese experience in the South through the lens of racial triangulation, this article also echoes with Black geographies that have been a fertile ground for challenging colonialism and White supremacy within and beyond geography and its lack of engagement with race (Hawthorne Citation2019). Black geographies touch on not only the space of diaspora, dispossession, surveillance, and violence but also the intersectionality with geographies of gender and sexuality, as well as a Black sense of place and the spatial practices of survival and resistance (McKittrick Citation2000, Citation2011; Pulido Citation2000, Citation2015, Citation2016, Citation2017; Lipsitz Citation2011; Bailey and Shabazz Citation2014a, Citation2014b; McCutcheon Citation2015; Shabazz Citation2015; Eaves Citation2017; Harris and Hyden Citation2017; Woods Citation2017; Allen, Lawhon, and Pierce Citation2019; Bledsoe and Wright Citation2019; Wright Citation2021). Examining the space of interracial encounters and coexistence between Chinese and Black communities, which is largely lacking in the geographic studies of race, makes the system of colonialism, racial capitalism, and White supremacy more revealing. The origin of Chinese immigrants in the South is traced back to the system of the global racial capitalism and plantation bloc, the same system that displaced Black bodies. Both Chinese and Black people struggled against, negotiated, and survived racism and segregation in the Jim Crow South. The confluence of the spatial practices of Black and Chinese agencies converged into the emergence of Chinese grocery stores, which served as a microcosm of interracial relationships and codependence that contributes to both a Chinese sense of place and a Black sense of place. Consequently, the decline of the Chinese grocery stores was directly caused by the destruction of Black communities: deindustrialization, urban crisis, incarceration, and a shrinking Black working class. Additionally, the Chinese grocery stores in the Delta were the main source of food distribution and consumption for the Black communities. Therefore, this research also potentially contributes to the Black geographies of foodscape (McCutcheon Citation2015; Ramírez Citation2015; Reese Citation2019). Black geographies not only confront racism, colonialism, and White supremacy but also “center those subjects, voices, and experiences that have been systematically excluded from the main stream spaces of geographical inquiries” (Hawthorne Citation2019, 8). Thus, this research echoes the call by emphasizing the power of human agency and experiences in the place-making of antiracism struggles.

More broadly, this article calls for the geographies of non-Whiteness and its connection with geographies of diaspora. The struggles of Black communities and other communities of color are intimately intertwined. Racial triangulation theory provides an entry point for the cross-examination of Black geographies with other geographies of non-Whiteness. The construction of Whiteness is contingent on the construction of non-Whiteness, not only between Black and Chinese but also between other communities of color. Instead of improving the working conditions for Black workers in the poultry industry in Mississippi, Latinx immigrants were used as a replacement and racialized against Blacks for their “belief in God,” “family values,” and “good work ethics” (Stuesse and Helton Citation2013). Vietnamese immigrants were racialized as the “model minority” to problematize Latinx and Cuban immigrants in Arkansas (Guerrero Citation2017). These are vivid examples of using one racial group against another for the maintenance of White supremacy, racial hierarchy, and labor exploitation. Moving beyond the White–Black binary lens and looking through the geographies of non-Whiteness interconnectedly not only reveals the nature and mechanics of capitalism, racism, and White supremacy but also invites the space of cross-racial solidarities, both ontologically and epistemologically.

Why the American South?

Stop talking about the South. As long as you are South of the Canadian border, you are South.

—Malcolm X (Citation1966, 417)

There have been numerous significant works on the American South by geographers, among which the topic of race and place draws particular attention (Delaney Citation1998; Crutcher Citation2010; Alderman and Graves Citation2011; Inwood Citation2011a, Citation2011b; Alderman and Inwood Citation2013; McCutcheon Citation2015; Eaves Citation2017; Harris and Hyden Citation2017; Williams Citation2017; Woods Citation2017). Several special issues in geography were launched with a southern focus, such as New Memorial Landscapes in the American South (Alderman Citation2000), Innovation in Southern Studies within Geography (Alderman and Graves Citation2011), and Black Geographies in and of the United States South (Bledsoe, Eaves, and Williams Citation2017).

Among these works about the South, Woods’s (Citation2017) work on the Mississippi Delta conceptualized the plantation bloc as a hegemonic power system that institutionalizes race and racism, (re)produces social domination, and exploits racial differences and cheap labor. Woods also paralleled the institutional hegemony with human agency and resistance that fertilizes the birth of social movements and blues. Woods laid out an analytical framework of understanding not only the South but also the world, and not only the past, but also the present and the future (McKittrick Citation2013). The legacies of the plantation system and Jim Crow still haunt the South and the United States. Over the years, the plantation system has altered into different forms: urban ghettos, prisons, and schools, not only in the South but across the nation.

Thus, southern exceptionalism does not stand well. Region itself is limiting in understanding the heterogeneity of landscapes. The South has long been overgeneralized and underrated. The image of the South exclusively bundled with racism, backwardness, and singular religiosity is internal orientalism (Jansson Citation2010, Citation2017; Nagel Citation2016), which falsely implies that the rest of the country is immune from these social issues and neglects the fact that the South is a lived space for many marginalized communities who also identify as southerners (Jansson Citation2017). Nevertheless, to challenge the essentialization of the South does not mean to deny the uniqueness of the place but quite the opposite: to examine both the distinctiveness and the interconnectedness of the South with the rest of the world and thus recognize the South as a multiple, dynamic, and heterogenous place. More important, the South has been a fertile land for myriad creative place-makings that contribute to the geographies of survival and resistance (Weise Citation2015; Eaves Citation2017; Harris and Hyden Citation2017).

Thus, the studies of the South illuminate and complete the understandings of the North, the nation, and the world, and one of the major roles for geographers is to disrupt the “normalized regionalism and the production of space” (Eaves Citation2017, 93). To do so, Southern geographers are encouraged to engage more with the topics beyond race and place, such as the intersectionality with religion, gender, class, and sexuality (Moore Citation2000; Brunn, Webster, and Archer Citation2011; Eaves Citation2017). One of the other major entry points to de-essentialize the South is to situate the place within the context of globalization and immigration (Winders Citation2005, Citation2006, Citation2011; Campanella Citation2007; López-Sanders Citation2012; Rodríguez Citation2012; Chaney Citation2015; Weise Citation2015; Nagel Citation2016; Guerrero Citation2017; Hinnershitz Citation2017; Yu Citation2018), which has increasingly drawn attention to the “New South” or “Nuevo South.” Although the “New/Nuevo South” challenges the bifurcated White–Black paradigm that has long been dominating the South, claiming the South “new” due to the recent arrivals of the immigrants ignores the region’s long history of immigration and its linkage to globalization and capitalism since the very existence of the South: Jewish people were among the earliest immigrant arrivals in the Delta during the mid-nineteenth century; Chinese, Lebanese, and Italians began to appear shortly after the Civil War (Loewen Citation1988; Canonici Citation2003; Walton and Carpenter Citation2012); Latinx immigrants arrived in the Deep South as early as the beginning of the twentieth century (Weise Citation2015); and Arkansas was the location of Japanese internment camps and refugee programs for Cubans and Vietnamese (Guerrero Citation2017). Although the size of immigrant populations in the Delta is less than the major gateway areas on the West Coast or in the Northeast, their impacts on shaping demographic, cultural, and sociopolitical landscapes locally and nationally are equally critical, if not more. Geographically, the Delta is located roughly at the intersection of the east–west and north–south midpoints of the United States, so it easily serves as a second stop of migration. New Orleans was the major gateway city for immigrants, an equivalent of San Francisco on the West Coast. More important, what drove immigrants to the South is the same system that brought slavery and maintains racial order: global and racial capitalism and the plantation bloc. Williams (Citation2017) argued that “racial competition” was used to legitimize the racialization of the other minorities as a means to suppress Black resistance to domination in the postbellum South. Similarly, Guerrero (Citation2017) argued that the “Nuevo South” is the new plantation regime, founded on White supremacy and exploitation of racial differences for the purpose of social control and material gain. Therefore, the plantation bloc conceptualizes the institutionalization of not only Black bodies but also bodies of immigrants and other communities of color. It determines the economic specialization and thus sociopolitical hierarchy in the South: Chinese concentration in the grocery stores, Italians in agriculture, Latinx in the poultry industry and construction, and Vietnamese in the shrimping and fishing industry. Thus, situating the South in the context of global capitalism and immigration echoes with the call for the geographies of non-Whiteness that emphasizes historical and contemporary multiracial understanding of the South. Studying the Chinese immigrants in the Jim Crow South contributes to a more nuanced understanding not only of the South where Asian Americans have long been left out of the narrative but also of Asian American studies that have largely left the American South out of the picture of the Asian diaspora.

Racial Triangulation in History: The Chinese Solution to a “Negro Problem”

There is but one solution out of the difficulty into which the South has been precipitated by the indifference and laziness of negro. We must employ Chinese immigrants.

—Memphis Daily Appeal (Citation1869)

In the summer of 1869, the three-day-long Chinese Labor Convention was held in Memphis, joined by planters from the South including Tennessee, Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, Virginia, Kentucky, South Carolina, and Georgia. The Convention was driven by the eagerness to revive the southern wealth and plantation system in the postbellum South, which was faced with increasing competition for the global cotton market (Memphis Daily Appeal 2 September 1869). The increasing mobility and job opportunities among the emancipated Blacks threatened Whites and led to a dearth of labor in the southern plantations due to the large-scale Black outmigration. Racial competition was a common tool for the Whites to prove Black inferiority by comparing them to another racialized minority group (Williams 2017). The goal of the Convention was to discuss the alternative options of cheap labor to replace Blacks and sustain the cotton plantation and agriculture in the South. The main strategy was the importation of Chinese immigrants to address the “Negro problem” (Memphis Daily Appeal 15 July 1869).

Around that time, the Chinese were only exposed to the South through the missionaries mostly as nothing more than “the Heathen Chinee” or cheap laborers working in railroad construction, manufacturing, domestic service, and plantations concentrated in California and the Caribbean (Cohen Citation1999). The Convention referred to the success of Chinese coolies replacing “lazy Negros” in the West Indies after the emancipation to convince the southern planters that Chinese were not only submissive but also ideal materials to be Christianized and civilized (Memphis Daily Appeal 15 July 1869). Some southern plantation owners even visited California to observe Chinese laborers’ manners, behavior, and work ethics on the sites of factories, mines, and railroad constructions (Memphis Daily Appeal 29 August 1869). They concluded that Chinese would be the ideal solution to replace Black slaves and revive the wealth of the South. The Memphis Daily Appeal reported on 26 June 1869:

They (The Chinese) are quiet, orderly, good tempered, docile, cheerful, willing workers; easily controlled, and so intelligent. … They are just the men, these Chinese, to take the place of the labor made so unreliable by Radical interference and manipulation. As to their heathenism that can be readily neutralized.

The cost, value, and suitability of having Chinese laborers were constantly compared to those of Black slaves: Chinese were cheaper, more intelligent, more industrious, less radical, and cleaner, coming from “a half-civilized country instead of a total barbarian one” (Memphis Daily Appeal 16 July 1869), hinting at the superiority of Chinese coolies to African slaves. Additionally, the Convention made comparisons of agricultural environment between China and the Delta:

The empire of China extends within the limits of the tropics, where in the valleys of her great rivers, rice, sugar, tobacco and all other products flourish as they with us. And it is well known that where rice and sugar grow the climate must be unfriendly to the white men who labor in the sun. It is, so here, and it is the same there; therefore, the Chinaman comes to us acclimated—prepared to withstand malarial attacks in our river bottoms and alluvial lands. (Public Ledger 1 July 1869)

It was argued that Whites were too fragile for the harsh climate in the South and Blacks were too lazy and radical. Not only were Chinese constructed to be the ideal cheap laborers for the Southern plantations but laborers from rural China were preferable to city dwellers (Memphis Daily Appeal 15 July 1869). The comparison implied not only the racial triangulation between Chinese and Blacks but also spatial triangulation between the imaginative geographies of Asia and Africa, as well as between rural and urban China. The rationale of replacing Black slaves with Chinese exemplifies not only racialization within the nation but also environmentalism and Orientalism under colonialism around the world (Said Citation1979). The processes at both scales determined the migration patterns at the regional scale for the maintenance of American South as the Cotton King of the world.

The Convention was also joined by the Immigration Committee and Transportation Committee and discussed the practicality of importing Chinese: the time and monetary cost of obtaining and delivering Chinese coolies to the Southern states (Memphis Daily Appeal 15 July 1869). Memphis was envisioned to be the center for receiving and redistributing the Chinese laborers. The Convention also called for an immigration labor company to financially support the importation of Chinese laborers. Among these interested capitalists, Nathan Bedford Forrest himself pledged $5,000 toward the company and planned to pay for 1,000 Chinese coolies with cash (Memphis Daily Appeal 16 July 1869). Interestingly, the plan also mentioned one critical condition under which the importation of Chinese could happen (Memphis Daily Appeal 29 August 1869): “The protection when they come into our country, and the enjoyment of the rights” supposedly granted by the 1868 Burlingame Treaty.3 On one hand, the alien status provided a layer of protection for Chinese that Blacks did not possess; paradoxically, the alien status was fundamental in the formation of the perpetual foreign and ambiguous identity among the Chinese who chose to stay in the South.

Although the Convention gained strong momentum, it also drew nation wide fear and criticism. One concern was that the increasing competition between Chinese and Blacks would further radicalize the Blacks and destabilize the social order (Memphis Daily Appeal 17 July 1869). Additionally, xenophobia was widespread, holding that importing Chinese who were a “pagan race” from the “heathen land” would only complicate the existing racial issues and threaten Christianity and White supremacy (Memphis Daily Appeal 14 July 1869). Eventually, the nativism and national fear that Chinese would steal jobs and land from Americans led to the anti-Chinese campaign on the West Coast and the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act.

The plan of importing Chinese to the South eventually failed due to a lack of financial support. Nevertheless, several experiments of using Chinese coolies in railroad and plantations in the South were carried out. The first shipload of Chinese to the South arrived in New Orleans in 1870 and the Chinese were dispersed to plantations in Arkansas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Later on, more Chinese were recruited from California, the Northeast, China, and the Caribbean to work in railroad construction and on plantations across the Mid-south. These experiments did not last long, however. Nationally, the Chinese coolie system was condemned as new slavery instead of free labor of voluntary emigrants. The coolie trade was officially banned in the United States by the federal government in the 1862 Anti-Coolie Act. This Act created more barriers to attempts to import Chinese laborers to work on the Southern plantations (Cohen Citation1999; Jung Citation2006). Additionally, China and Hong Kong (under British rule) began to restrict and regulate emigration. More important, the Chinese laborers turned out to be nothing but “docile” and “submissive” in the face of the harsh working conditions, meager payment, racism, and broken contracts (Cohen Citation1999; Hinnershitz Citation2017). They protested and rebelled against the exploitation and violence and eventually abandoned the work sites (Cohen Citation1999).

The Chinese Labor Convention was only one chapter of the larger picture of the Chinese coolies being sold and exploited under the global capitalism system of plantation economy. Although the plan of replacing Black slaves with Chinese coolies in the South failed, the attempt reflected the maintenance of the plantation system and White supremacy through racial and spatial triangulation between Chinese and Blacks, through objectification and commodification of laborers, and through the racialization of one minority group against another. The Chinese laborers were constructed to be the ideal solution to the “Negro problem” and the key to revitalize the postwar South. Many Chinese laborers who left railroad construction across the mid-South or were dispersed from the failed experiments on plantations remained in the South and sought various economic opportunities, largely in grocery businesses but also scattered in laundry businesses, farming, and sharecropping (Cohen Citation1999). Interestingly, the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act gave more leniency toward businessmen than laborers and so did not affect the immigration paths of the Chinese grocers in the South as much as it did in other parts of the United States. Back in China, the Japanese invasion during World War II and the Communist party’s control over mainland China closed the door for many Chinese to return to their homeland. As more and more Chinese chose to claim the Delta as their home, the “Chinese as solution” became “Chinese as problem” as they struggled with the racial positioning between Black and White in the Jim Crow South, as both foreigners and people of color.

Space/place/scale play a major role in the racial triangulation between Chinese coolies and Black slaves, as they present a global–regional–local–individual matrix of spatial power and practices: the ambition of the postbellum South to dominate the cotton kingdom in the world and the fear of the emancipated Black bodies; the geographical imagination and racialization of non-Western countries and people during colonialism; the shifted immigration and emigration policies due to changing geopolitics; the formation of the racial state by the Jim Crow laws and the Chinese Exclusion Act; the location of Memphis as both a transportation hub and market center for cotton and slave trade; and the not so “docile” Chinese laborers in the face of exploitations and racism. These factors, at global, national, regional, local, and individual scales, fertilized the emergence of Chinese grocery stores in the land of cotton. The next section focuses on the spatial distribution and redistribution of Chinese grocery stores at the regional scale and the scale of region as a force that shapes race and place.

The Spatial Distribution and Differentiation of Chinese Grocery Stores in the Delta

Although small in size this region (the Mississippi Delta) is known nationally and internationally as a center of tragedy and schism; of extreme levels of poverty and wealth; and of historic movements of repression and freedom; and as the center of both plantation culture and the African American working-class culture known as the blues.

—Woods (Citation2017, 2)

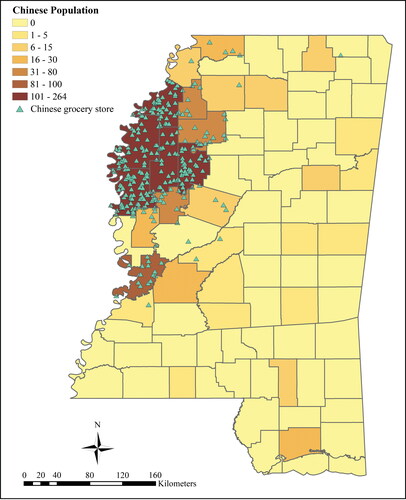

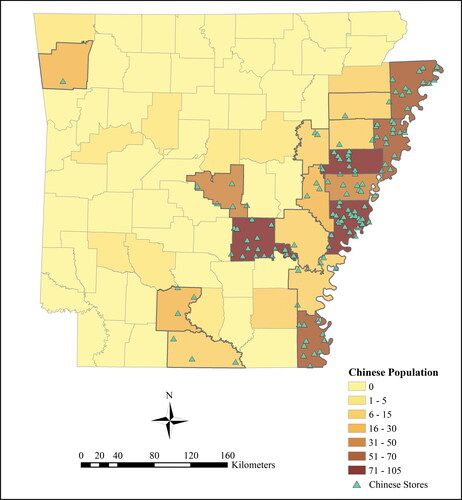

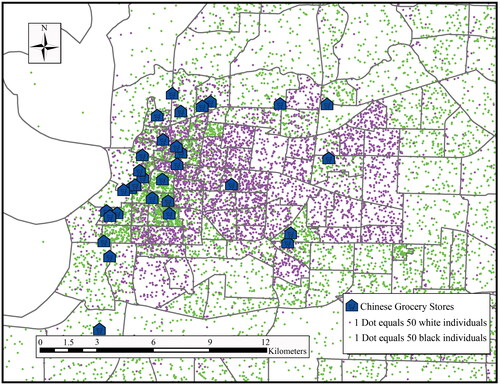

When the experiment of replacing Black slaves with the Chinese coolies failed in the South, many Chinese chose to stay and seek other economic opportunities. The majority of Chinese found their way into the grocery businesses that eventually spread across the Delta region. As the maps of the geographical distribution of Chinese grocery stores in Mississippi and Arkansas illustrate ( and ), the Chinese and the Chinese grocery stores were clustered in the Delta region where cotton plantations, sharecroppers, and Black laborers were concentrated. In the urban areas, the Chinese grocery stores were largely located in the Black neighborhoods, as is illustrated on the map of Chinese grocery stores in Memphis (). The unique regional geography, history, and economic and social structure in the Delta together contributed to the emergence and concentration of Chinese grocery stores, which Loewen (Citation1988) referred to as the “near monopoly” in the “pre-supermarket past” (36). The rich soil and flat topography in the Yazoo–Mississippi River Delta region were ideal for cotton plantations, which was the foundation for the social and economic stratification and power structures in the Delta. Along with the abolishment of the slavery system after the Civil War, the commissaries that most plantations provided for croppers for basic goods also vanished. Thus, there was an increasing demand among the Blacks for grocery stores. Under the rigid social stratification and spatial segregation during the Jim Crow era, most of the White grocery stores did not serve Blacks. After decades of exploitation by the slavery and sharecropping systems that disfranchised Blacks from land ownership, resources, and capital, it was nearly impossible for Black communities to start their own grocery businesses. The housing limitations for Chinese in the White part of town and the reliance on Black clientele contributed to the concentration of Chinese stores in Black neighborhoods. Finally, being both non-White and foreigners, Chinese had limited job opportunities in the Jim Crow South. Therefore, they heavily depended on ethnic, kinship, and transnational ties within the Chinese community. Paradoxically, being an outsider of the existing social caste meant that the Chinese were perceived as less threatening and less judged for catering their business toward Blacks. Later, the established Chinese grocery business owners helped bring their family and friends to the Delta to open more Chinese grocery stores, which eventually spread all across the Delta. Thus, the shared geographic origins and strong social ties among the Chinese immigrants in the Delta also facilitated their economic clustering in the grocery business. Interestingly, some interviewees mentioned that southern China (where the majority of the Delta Chinese were originally from) and the Mississippi Delta shared a similar physical environment: rural, fertile, agricultural, humid, and hot, which brought a sense of nostalgia and comfort among the Delta Chinese

Figure 1 Chinese population and Chinese grocery stores in Mississippi, 1952. Data source: 1960 U.S. Census, Social Explorer; Mississippi State County Boundaries Map, U.S. Census TIGER/Line shapefiles. Tri-State Chinese Directory of Mississippi, Arkansas, and Tennessee, published in 1952 by the Chinese Commercial Directory Service Bureau, Greenwood, Mississippi. From the personal collection of the Dunn Family, Memphis, TN.

Figure 2 Chinese population and Chinese grocery stores in Arkansas, 1952. Data source: 1960 U.S. Census, Social Explorer; Arkansas State County Boundaries Map, U.S. Census TIGER/Line shapefiles. Tri-State Chinese Directory of Mississippi, Arkansas, and Tennessee, published in 1952 by the Chinese Commercial Directory Service Bureau, Greenwood, Mississippi. From the personal collection of the Dunn Family, Memphis, TN.

Figure 3 Chinese grocery stores in Memphis, 1952. Data source: U.S. Census 1950, Social Explorer. Tri-State Chinese Directory of Mississippi, Arkansas, and Tennessee, published in 1952 by the Chinese Commercial Directory Service Bureau, Greenwood, Mississippi. From the personal collection of the Dunn Family, Memphis, TN.

Geographically, unlike the Chinatowns in major cities in the Northeast and on the West Coast, the Chinese population and Chinese grocery stores in the South were simultaneously concentrated and scattered across different cities, towns, and rural areas adjacent or accessible to plantations via trains and roads, mainly due to their reliance on the plantation economy and sharecroppers. In larger cities like Memphis and Greenville, the majority of the grocery stores were located in the Black neighborhoods, or along the borders between Black and lower income White neighborhoods. Although the social and cultural bonds among Chinese who lived in the larger cities (e.g., Memphis, Greenville, Cleveland, and Helena) were not as strong as those in small towns and rural areas in the Delta, the cities were the major locations for social and cultural gatherings among Chinese across the whole Delta region. In these larger cities, there were a few Chinese restaurants and laundry businesses but not to the economic scale of the major immigration gateway cities such as New York City. These Chinese businesses did not exist in rural areas or small towns in the Delta, largely because there was hardly demand for laundry businesses or “exotic” Chinese cuisine among sharecroppers living on meager wages in the small southern towns. Midsized Delta towns such as Rosedale, Clarksdale, and Forrest City and small towns like Pace, Louise, Lula, and Earle often had a range of two to five Chinese stores located side by side sharing the same customer base. Other grocery stores were located along the major highways in between the cities and towns.

Although the Delta Chinese shared similar experiences and their social networks were maintained via place of origin, kinship, and marriage, their experiences were differentiated across class lines and across localities. Racism and discrimination toward Chinese in the Jim Crow era were universal but their day-to-day experience and the levels of tolerance from the locals varied among places. Local demographics, culture, and politics engaged differently with national and regional narratives and thus generated a heterogeneous landscape of inclusion and exclusion. One interviewee grouped Chinese of the South into “three Chinese”: Mississippi Delta Chinese, Memphis Chinese, and small-town Arkansas Chinese. Generally, Memphis and the Arkansas Delta were more tolerant toward Chinese people than the Mississippi Delta. In towns where the number of Chinese was not visible enough for them to be seen as a threat, Chinese were treated as “near-White” and the relationship between White and Chinese was usually more civil. In those towns, Chinese were allowed to purchase property in the White part of town and their children could go to White schools. In comparison, in the towns where the Chinese population was sizable and concentrated enough to be threatening, the locals tended to be more conservative. The hostilities toward Chinese in some towns (such as Rosedale, Mississippi) increased as the number of Chinese grew over time. Additionally, the size of the city or town matters. Normally, the larger the city or town, the more tolerant the locals were toward the Chinese, as if the “threat” was diluted by a larger population base. William Alexander Percy, a Greenville planter, described Chinese in Greenville, Mississippi, in 1941: “They (Chinese) are not numerous enough to present a problem-except to the small white store keepers” (Percy Citation2006, 18). This suggests that the racial hostilities against Chinese were compounded by economic competitions with White grocers. Often, the factor that differentiated town from town was the White elites who determined the local social and racial caste and whether Chinese belonged to “just Black” or “near White.” One of the unique examples was Marks, Mississippi, where Chinese were among the early founders of the town, and they were relatively accepted, intermingled, and respected. There was even a street named after a Chinese family.

Interestingly, the differentiation of racism and discrimination toward Chinese among the Delta localities also affected the social and cultural ties within the Chinese community. Seemingly paradoxical, but where the discrimination was more prevalent, the social and cultural bonds appeared to be tighter. For example, the Chinese in the Mississippi Delta seemed to maintain a stronger place and cultural identity than Chinese in the Arkansas Delta and Memphis, and their voices were more documented and represented in the Southern history. In addition, social and cultural ties at the transnational scale contributed to the differentiation among the Delta Chinese. Even though the Delta Chinese were mostly from Guangdong Province in China, there were cultural and linguistic differences across localities of origins, mainly between Toy Shan and San Hui (equivalent of counties in the current U.S. administrative system). Chinese from the same home village tended to maintain their regional ties after moving to the United States. Overall, though, the smaller size of the Chinese community thinly spreading across the Delta did not diminish their shared strong social connection and cultural identity.

This spatial differentiation of the Chinese experiences in the Delta also determined the redistribution and migration patterns because of the unevenness of political, social, and cultural contexts across different localities. Among many factors, educational inequality led to either short-term commuting or long-term regional or international migration. The educational system in the Delta during Jim Crow was segregated and not equal between White and Black schools. The drastic differences of resources and infrastructures for White and Black children still persist today. In many conservative cities and towns, Chinese were lumped together with Blacks as “colored” and denied admission to the White public schools. The conditions in Black public schools did not live up to the standards of Chinese parents. Some Chinese families chose to send their children back to China for education, until the Japanese invasion in China during World War II. Some Chinese families hired private tutors or built Chinese schools by pulling resources from the church and the Chinese community (Wong and Lee Citation2011). Other families sent their children to live with their friends or relatives where they could register with the White schools. These children often commuted daily or weekly (living with their relatives on weekdays and working at the stores during weekends). Some Chinese families relocated their entire stores to cities or towns where their children could be accepted in White schools. In Gong Lum v. Rice (Citation1927), a Chinese family fought all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court when their children were prohibited from attending the White school in Rosedale, Mississippi. After they lost the fight because the Court ruled that Chinese were colored and therefore should go to Black schools, the family eventually moved the store to Arkansas so that their children could go to White schools (Berard Citation2016). During this period, there was an increase in enrollment of Chinese students in Memphis schools due to the regional migration of Chinese from the Mississippi Delta. During World War II, both U.S.–China relationships and the status of Chinese Americans improved as many served in the army fighting for the United States. Gradually, many cities and towns opened their doors to the Chinese students. Although the integration of Chinese into the White public schools happened before Brown v. Board of Education, it was not until the civil rights movement that Chinese were widely accepted in White schools. The following interview responses demonstrate the various strategies of dealing with educational inequality in the Delta that led to migration among Chinese.

I was born in Merigold. I lived there ’til I was about seven. There was a Chinese school in Cleveland. We were not allowed to go the public schools. I went there ’til I was in the third grade. Then we moved to Boyle because it was one of the two towns or three towns at that time that did have a place for the Chinese to go to a public school. (Female, age eighty-six, Merigold, Mississippi)

I grew up in Leland, Mississippi, and did not go to school in Leland because it was one of those towns that had selective segregation, I guess you would say. And so I ended up—first of all, in the first grade I had a private tutor that the school board in Leland hired, and I went to this teacher’s house every day for school. And then my father decided that was enough, so he moved the family to Memphis where he bought another grocery store, and I went to school for about a year or so. (Female, age eighty, Leland, Mississippi)

They (my dad and his siblings) were not allowed to go to school in Mississippi. So my grandfather had my daddy take them back to China to go to school. And after a certain period of time, he brought back all of his siblings, and they went to Memphis to go to school. So even though they had to travel, like between Rosedale and Memphis or Rosedale and Greenville, or wherever they could continue their education, they did so. (Female, age seventy, Houston, Texas)

The geographical distribution and spatial differentiation of Chinese experiences and Chinese grocery stores in the Delta resulted from spatializing and scaling racial triangulation. Region is a dynamic, relational, and heterogeneous process that formed and re-formed the spatial experiences and racial identities among the Delta Chinese. To begin with, the revival of the postbellum Delta as the “cotton kingdom” in the face of global market and labor competition encouraged the Chinese immigration to the region and the emergence of Chinese grocery stores. The physical geography of the Delta, similar to southern China where the Delta Chinese originated from, shaped their unique experiences and place identity. Unlike the major U.S. cities in the Northeast and on the West Coast where Chinese populations were sizable enough to form self-sufficient Chinatowns, the Delta had a small number of Chinese simultaneously concentrated and scattered across the rural and agricultural Delta as well as major urban areas. As a result of racial and spatial triangulation in the Jim Crow South, the Chinese grocery stores ended up mostly serving the Black neighborhoods. As foreigners, Chinese relied on transnational, social, and ethnic ties to build their economic niche. Their alien status allowed more resources and tolerance toward catering their small businesses to Blacks. Similar to Mexicans leveraging support from Mexican government as a strategy to survive in the Jim Crow South (Weise Citation2015), the Delta Chinese also had transnational support and protection that Blacks did not possess. As people of color, the Delta Chinese shared a similar experience of oppression and discrimination. Consequently, they maintained a strong social and cultural bond as well as a cohesive and distinctive racial and place identity. Their experiences were differentiated, however, due to the uneven economic, political, and social structures across localities that led to the geographical (re)distribution and intra- and interregional migrations of the Delta Chinese and their grocery stores. Therefore, both the scale of region and locality were crucial in shaping the spatial experiences of the Delta Chinese and their (re)formation of racial and place identity, and thus their everyday life experience at the individual scale, as I discuss in the next section.

People of In-Betweenness: The Delta Chinese Experiences in Everyday Life

It was like one foot in the Black world, one foot in the White world.

—Female, age seventy-two, Memphis, Tennessee)

Body is the primary physical site of personal identity (Smith Citation1992). “History, memory, toleration, hatred and racism are inscribed on the bodies and minds of the characters, and in this, they ‘become’” (McKittrick Citation2000, 129). The hegemonic discourse of racial triangulation translates into the embodied experience and subjectivities in everyday life. The civic ostracism (discrimination and racialization) and the relative valorization (perpetual foreigners) that Chinese faced were universal across the nation (C. J. Kim Citation1999) but particularly magnified in the Jim Crow South as Chinese were striving to fit into the rigid binary racial structure between White and Black. The racial triangulation was further compounded by the geographical distribution of Chinese who scattered thinly across the rural and agricultural Delta land. Roediger (Citation2005) used “inbetween people” to address communities neither securely White nor non-White who experience the spectrum of treatment between hard racism and full inclusion, the study of which must examine both similarities and differences. Chinese occupy a racial and social space of in-betweenness: “just Black” and “near White.” This social space of in-betweenness was materially manifest in the lived space, including homes, schools, churches, hospitals, cemeteries, and work space. One of the questions faced by many Chinese on their arrival in the segregated South was the ambiguity of which space was safe for them: White or Black. This space of in-betweenness also translated into their ambiguous political attitudes toward the civil rights movement:

One of the first times I noticed things, was just going into the train depot: seeing a sign that says “White and Colored,” on the restrooms and on the drinking fountains. But, as a boy, you know, around six years old or so, you’re reading them and you’re wondering, “I’m not White, and I’m not colored. If I had to go to the bathroom or get a drink of water, what should I do?” (Male, age eighty-five, Holy Grove, Arkansas)

In the community where we lived we were quite accepted, but the Blacks considered us as Whites. The Whites considered us as non-Black, but we were kind of stuck in the middle there. (Female, age seventy, Cleveland, Mississippi)

So how did it [the civil rights movement] affect me? You know feeling-wise, I wasn’t truly White. At the same time, I felt badly. We had Black customers. We had a pretty good relationship with the Black neighborhood because our store was right at the edge of the Black area of town. I was torn. (Female, age seventy-four, Drews, Mississippi)

Despite the racial differences between Chinese and Blacks and between Chinese and Whites, this distance is much smaller than that between Whites and Blacks. This racial space of in-betweenness, coupled with being foreigner or outsider, made Chinese the perfect middlemen between Blacks and Whites (Bonacich Citation1973). This led to the economic co-independency between Chinese and Blacks, which necessitated the success of the Chinese grocery stores in the Black neighborhoods. Blacks were served with much more respect in the Chinese stores than in the White stores, most of which had their doors completely closed to the Blacks:

We did make a living off them (Blacks), but we treated them with respect more than if they went to a Caucasian run store. We treat them with respect. We thanked them. We showed them that we appreciated it. We always spoke to them nicely. We never said any bad things to them. We always treated our customers with respect as a human. I think that is the reason why we do so well. I think that is the reason why Chinese in general did well. (Male, age seventy-five, Hollandale, Mississippi)

Economically, Chinese grocery stores relied on Blacks. Socially, however, Chinese were trying to climb the racial ladder toward White while drawing the racial boundaries with Blacks. For immigrants, to become an American also means trying to become White, because Americanization is a process of not only assimilation but also whitening (Roediger Citation2005). Both cultural assimilation and racial whitening measure the fitness for citizenship and resources. Whiteness embodies privilege and socioeconomic mobility, whereas Blackness embodies problems and inferiority. Moving closer to White and all the premises associated with Whiteness involves disassociation from Blacks. In other words, it was not the Black community that Chinese socially distanced themselves from but the experience of dehumanization and disenfranchisement associated with Blackness in the White supremacist society. The Delta is the cradle of blues, an aesthetic documentation and celebration of Black life in the Delta (Woods Citation2017). Yet, the histories of blues and the Delta Chinese seemed like two parallel lines that never intersected. Instead, Chinese chose White space: attending the White church and White public school, having a White name, and socializing with Whites. One interviewee (male, age seventy-one, Greenville, Mississippi) recounted that any association with Black children would potentially jeopardize their opportunities to enter White public schools in Greenville, which were much better resourced than Black schools. When asked about why Chinese families chose to go to White church but not Black church, one interviewee shared, “We do not want to go to Black churches because we don’t want to be seen as Black in the eyes of White” (female, age fifty-five, Shaw, Mississippi). These experiences exemplify that Whiteness is a social construction contingent on the definitions of non-Whiteness, and racial triangulation eventually normalizes White supremacy and translates into everyday life of communities of color under the White gaze.

The distance between Chinese and Blacks was not unusual but resembles the Southern and Eastern European immigrants’ dissociation from Asians, Latinx, and Blacks on their journey to Whiteness in the early twentieth century (Roediger Citation2005) or the strategic use of Whiteness among Mexicans in the Deep South during Jim Crow (Weise Citation2015). The only difference is that Chinese were never truly able to transgress into the noncolored territory. Despite social association with Whites and disassociation from Blacks, Chinese never had the social power to determine the racial hierarchy or the ideological and material processes of racialization. Instead, they survived, adapted, and adjusted. “Fit in and don’t make trouble” (male, age seventy-one, Forrest City, Arkansas) was the survival strategy for many Delta Chinese as non-White, non-Black foreigners in the Jim Crow South. Additionally, Chinese are still perceived to be perpetual foreigners by both Whites and Blacks. Although foreign status could serve as a distraction from colorism, it also suggests being less American. Thus, the Chinese were often constructed as the model minority to pathologize Blacks. In the annual homecoming celebration event in 2018 for the Delta Chinese, one of the speakers, a White male local historian with the intention of praising the contribution of the Delta Chinese, compared them to “the other group who only knows to kneel down in the football field” (referring to Colin Kaepernick). More than three generations since Chinese first landed in the South, the Delta Chinese are still far from being embraced as Americans. They are questioned about where they come from or referred to as “the better minority” to discipline and shame Black communities. Racial triangulation and the construction of the model minority are internalized within the Delta Chinese community, who constantly live under the White gaze. This kind of Whiteness is conditioned by holding on to the image of model minority. For example, despite socioeconomic mobility among the later generations, the majority of the Delta Chinese are concentrated in professions such as engineers, accountants, lawyers, or pharmacists but rarely in art and humanities. To a large degree, the occupational concentration along racial lines today is not unlike the concentration of Chinese in grocery businesses during the Jim Crow era. Both resulted from racial marginalization in economic sectors.

This is not to say, however, that the Chinese were passive recipients of racism and White supremacy. The process of identification as a Delta Chinese is complex, multilayered, and seemingly contradictory at times. Even though the Delta Chinese were transgressing racial lines for economic and social causes, they still strived to maintain their own culture, through food, ceremonies, and social gatherings. Interracial marriage was discouraged and stigmatized not only between Blacks and Chinese but also between Whites and Chinese, due to the fear of losing their Chinese identity. Additionally, although the Chinese were criticized for the lack of participation during the civil rights movement as a collective group, there were numerous cases like Gong Lum v. Rice where Chinese fought for their equal rights in marriage, education, housing, and economic opportunities in the South (Hinnershitz Citation2017).

Race and ethnicity are placed and embodied experiences in everyday life. Unlike Chinatowns in major U.S. cities in the Northeast and on the West Coast, the rural, Southern, Bible Belt Delta during Jim Crow exerted a stronger force of assimilation on the small number of Delta Chinese into becoming American and White. Paradoxically, there were also strong cultural and social bonds within the community. Under the particular geographical and historical contexts, the consequence of racial triangulation was the simultaneity of economic dependence on Blacks, social integration with Whites, and cultural preservation within the Delta Chinese community. These interrelationships between race and space/place/scale exemplify, again, that racial triangulation perpetuates White supremacy. Even though the Delta Chinese took a survival approach different from Black activism in the face of discrimination and racism, they were not passive. Rather, they fought for justice in their own way through self-mobilization, cultural preservation, and the place-making of the grocery stores, which are discussed in the next section.

The Chinese Grocery Stores as the Solution to the Racial Segregation in the Jim Crow South

My daddy would say if the gin went blue then the cotton carts were coming in and we were going be getting busy. (Male, age eighty-five, Louise, Mississippi)

The Chinese grocery stores emerged as a spatial solution to the White and Black segregation in the Jim Crow South. These stores mostly served the Blacks, filling the economic niche that would not have been filled under racial segregation. Located in the Black neighborhoods or on the border between White and Black neighborhoods, these stores were the most racially mingled places in the Jim Crow South. Many Chinese recounted their memories of working in the grocery stores according to the schedule and the need of plantation workers. They also used a credit system so that their customers could make payments based on their payroll schedule, implying the trust between Chinese and Black communities. The following interview responses demonstrated the mom-and-pop store managing model and the stores’ reliance on the cotton plantation system.

We would open at seven ’til about ten every night. We had to open early then, because people would go to the field and want something to take to the field. They would unload a cotton chopper truck. I remember on the weekends, we would be open ’til twelve, one o’clock, or two o’clock in the morning because after they would get through picking cotton, they would come in and do their shopping. (Male, age eighty-five, Louise, Mississippi)

We sold, of course you probably don’t know it. We called them kneepads. When they pick cotton with them because they pick cotton on their knees. We used to have some of the people who owned the plantations would come in and say, hey, I need twenty-five bologna sandwiches. So they would want us to go on and fix the sandwiches so that they can hand them out. We would do things like that. (Female, seventy-four, Drews, Mississippi)

Because Chinese were not allowed to buy property in White areas in many towns, the Chinese families lived at the back of the store, which was referred to as the “living quarters,” where the whole family ate, played, and slept (). The combination of work and life space in the grocery stores allowed flexible and early opening hours to cater to cotton plantation workers. These stores also facilitated the integration of economic, social, familial, and cultural functions. For example, the parents could watch their kids while taking care of the store, and children worked in the stores after school. Having family members work and live in the stores reduced the cost of both housing and labor. These tightly knit, family-run mom-and-pop stores also served as a cultural unit where Chinese values and discipline were passed on to the next generation. In the limited time of closing hours, these stores were often a social gathering place for the nearby Chinese families. It was not until after the civil rights movement when Chinese could buy houses in the White areas that they started to separate living and working space. The following interview excerpts depict the Chinese grocery stores as a multifunctional and multiracial space.

Figure 4 The Original Min Sang & Co. grocery store, Greenville, Mississippi, late 1920s. Photo courtesy of Frieda Seu Quon.

Figure 5 The Seu Brothers and their children inside the Min Sang & Co. grocery store, Greenville, Mississippi, late 1940s. The store was connected to the “living quarter” through a door at the back. Photo courtesy of Frieda Seu Quon.

Figure 6 The front store entrance of the Min Sang & Co. grocery store, Greenville, Mississippi, 2016. Photo by the author.

Figure 7 The “living quarter” behind the Min Sang & Co. grocery store, Greenville, Mississippi, 2016. Photo by the author.

Yeah, it was real convenient. When you cook, you could go back there and eat. Then you can go to work at the same time. You don’t go home because your home is right behind you. (Male, age ninety, Jonestown, Mississippi)

Because the cotton choppers would come in. It would be a whole busload at a time. They would assign one of us kids to each island. You had the potato chips. You had the peanuts. You had the cokes. You made sure you collected whatever went out of your division. So we started doing that at a very early age. We all had our responsibilities. Certain people were supposed to sweep. You had to fill up the drink machines. You had to stack groceries. (Female, age seventy-four, Drews, Mississippi)

And we got to learn a lot about their cultures, you know, so I really considered myself to be tri-cultural, you know—Chinese, Black, and White. I think I learned to appreciate diversity, you know, having to grow up with Caucasians and Blacks, and being Chinese. We just learned how to deal with so many different cultural and ethnic backgrounds—that gave us a great experience of how to deal with people in general. It developed our interpersonal skills and stuff like that. (Male, age seventy-six, Cleveland, Mississippi)