Abstract

Military geographies have engaged with the subject of nonhuman nature in diverse and fruitful ways, mainly under the analytics of environment, landscape, territory (and terrain), and the more-than-human. Despite the diversity of contexts studied, spaces of displacement have not drawn scholarly attention within this literature. Starting from the position that human–nonhuman relations are emplaced, we offer an exploration into the natures of forced displacement during war. Specifically, we show that by extending our vision to spaces of displacement, we can see militarized nature under new, including more hopeful, lights. Drawing empirical material from the published memoirs of women and men displaced to the islands of the Aegean archipelago during the Greek Civil War (1946–1949), we make a twofold case. First, spaces of displacement should be seen as key in the study of militarized geographies, as they explode the ways militarized nature is understood to be reproduced. Second, nonhuman nature, in the context of the spaces of displacement, can act as a vector of emplacement, resistance, resilience, and reworking against the violence of the post–World War II liberal state.

军事地理学以多样且有效的方式开展了对非人类大自然的研究, 主要分析环境、景观、领土、地形和超人类。尽管有多种研究背景, 但迁移空间并未引起学术界的关注。基于人类与非人类关系被安置的观点, 我们探讨了战争期间被迫迁移的大自然。如果将视野扩展到迁移空间, 在这个全新的、更具希望的视角下, 我们可以看到军事化的大自然。我们从希腊内战(1946-1949)期间被迁移到爱琴海群岛的女性和男性回忆录中, 发掘了经验性材料, 提出了一个双重论点。首先, 由于迁移空间能颠覆对军事化大自然的理解, 因此迁移空间应被视为军事化地理的关键。其次, 在迁移空间的背景下, 非人类大自然能够承载安置、抵抗、恢复和改造二战后自由国家的暴力。

De maneras diversas y fructíferas, las geografías militares se han involucrado con el tema de la naturaleza no humana, principalmente bajo las analíticas del medio ambiente, el paisaje, el territorio (y el terreno) y las categorías más-que-humanas. Pese a la diversidad de los contextos estudiados, los espacios del desplazamiento no han atraído atención académica dentro de esta literatura. Empezando con el supuesto de que las relaciones entre humanos y no humanos están emplazadas, presentamos una exploración de las naturalezas del desplazamiento forzado en la guerra. Específicamente, mostramos que, al extender nuestra visión hacia los espacios del desplazamiento, podemos percibir la naturaleza militarizada bajo ópticas mucho más novedosas y esperanzadoras. Con base en material empírico derivado de las memorias publicadas por mujeres y hombres desplazados al archipiélago del Egeo durante la Guerra Civil Griega (1946-1949), identificamos una circunstancia doble al respecto. Primero, los espacios del desplazamiento deben verse como claves en el estudio de las geografías militarizadas, en la medida en que ellas hacen estallar las formas como se cree es reproducida la naturaleza militarizada. En segundo término, la naturaleza no humana, en el contexto de los espacios del desplazamiento, puede actuar como un vector de emplazamiento, resistencia, resiliencia y reelaboración, contra la violencia del estado liberal posterior a la Segunda Guerra Mundial.

On 20 February 1948, a navy frigate sailed to Makronisos, a tiny island off the shores of Attica. Its officers warned the banished, unarmed soldiers gathered by the coast that unless those in charge of the previous day’s riot surrendered, they would open fire. The soldiers did not and the frigate opened fire. The soldiers replied by throwing stones, the same stones they carried Sisyphus-like in their daily work-cum-torture. Officially seventeen soldiers died, although testimonies put the number in the hundreds.

Aegean islands have been used as spaces of banishment since antiquity. In the twentieth century, it was the infamous Law 4229 (1929) that inaugurated mass banishment, or ektopismos in its official term (from ek-topos, literally dis-placement). Focusing on the islands of the Aegean at the time of the Greek Civil War (1946–1949), in this article we seek, first, to extend the scope of critical military geographies to include the spaces of displacement vis-à-vis military (im)mobilities (Merriman et al. Citation2017). Second, we suggest that spaces of displacement can multiply what “militarised natures” (Gregory Citation2016) can be. In doing so, we unearth a wartime role for nonhuman nature as a vector of emplacement (Roy Citation2017), resistance, resilience, and reworking (C. Katz Citation2004).

Recently, a vibrant strand of geographical scholarship has emerged that is interested in how the materialities of nature (or terrain, or territory) become the “medium through which military and paramilitary violence is conducted” (Gregory Citation2016, 4; Elden Citation2021). These largely posthumanist accounts have traced how the materialities of nature such as topography (Gordillo Citation2018) or sand (Forsyth Citation2017b) can be “weaponised for military gain” (Jackman et al. Citation2020, 1) or influence the tactics of war. From the mud of the trenches in World War I leading to voluminous warfare (Gregory Citation2016) and desert sand in northern Africa leading to World War II covert warfare experiments (Forsyth Citation2017b), to Hamas harnessing the “elemental agency of the sub-surface” (Slesinger Citation2020, 19), “biophysical formations” (Gregory Citation2016) are understood “as the media through which tactics and technologies of warfare are legitimised and enabled” (Forsyth Citation2019, 6).

Although diverse, these understandings of militarized nature are circumscribed, due to at least two features. First, although the spaces that are being studied are not limited to the battlefield or battlespace, they usually exclude spaces associated with military (im)mobilities (Merriman et al. Citation2017). Second, militarized nature is mostly studied in relation to standing armies, less to other types of combatants (Gordillo Citation2018), and very rarely to those displaced by, exiled by, or fleeing war (Merriman et al. Citation2017).

We seek to integrate and expand on these literatures by introducing “ecologies of displacement.” According to Jones (Citation2000, 281–82), “the spaces where […] encounters between humans and animals occur […] determine to a significant degree the nature of the encounter.” We thus expect that moving into the hitherto understudied spaces of displacement could provide different understandings of militarized natures. We are inspired by the relationality of post-Agambenian research on refugee camps that shows that (informal) camps are not just biopolitical spaces but spaces “where new political subjectivities and solidarities emerge” (I. Katz Citation2015, 85). Analogously, we hypothesize that the materialities of nature (or terrain, or territory) vis-à-vis militarized spaces of displacement are not just enrolled by the military but are also a “source of tactics of survival” (Martin, Minca, and Katz Citation2020, 749) for the displaced. Our hypothesis is supported by contemporary archaeologies of displacement (Hamilakis Citation2017) that indicate that the things used, constructed, collected, or kept by the displaced (wooden spoons, elaborate vases, flowers, rocks, gardens, stone ovens) are testaments to their resilience under deprivation.

Drawing from Pugliese (Citation2015), we mobilize the term ecologies instead of natures to draw attention to the relational and contingent geographies that characterize militarized nature. Often—but not always—the literature on militarized natures distributes agency in a way that favors the “natural” (Klinke Citation2019). In our case, we maintain a focus on ecologies to underline how the human and the nonhuman form “interlinked and networked assemblages of heterogeneous actors and relations that are mutually constitutive within situated formations” (Pugliese Citation2015, 6). In essence, we agree with Elden (Citation2021) that to overcome agential asymmetries, a focus on “ecologies might be a better model” (note 4).

We draw empirical material from the published memoirs and autobiographical novels and testimonies (martiries) written by displaced men and women. In selecting the corpus, we included documents from many islands, reflecting a variety of displacement modes (exile, prison, reeducation camp), as well as different physical geographies. Thus, all major islands of displacement are included in the corpus: Makronisos (several types of confinement), Yaros (prison camp), Trikeri (prison camp), and Chios (prison). Furthermore, all of these islands are different in terms of physical geography. Makronisos and Yaros are uninhabited, with very few to no sources of fresh water and little to no vegetation; Trikeri is a small but inhabited island with a diverse landscape, including olive groves and pine tree woodlands; and Chios is a big, inhabited island with many different landscapes. We also included documents written by voices that are often marginalized in military geographies, such as women and civilians (Jackman et al. Citation2020). All documents are either published or available through curated digital and physical museum collections.

We start by setting the context of displacement during the Civil War. We follow with empirical findings: First, we discuss the production of nature-as-torture to break the bodies and minds of the displaced; we then describe how the displaced used the same nonhuman natures to produce ecologies of emplacement, resistance, reworking, and resilience. We close by discussing our findings in relation to related literatures.

Aegean: The Archipelago of Displacement

In Greece, World War II was followed by a civil war (circa 1946–1949). The two sides were the Greek government with the aid of Britain and the United States and the Democratic Army of Greece, the military wing of the Greek Communist Party, aided by neighboring communist countries. The war, “the first major postwar counterinsurgency campaign” by the United States (Chomsky Citation1997, 329), was won by the Greek state. It was during the Civil War that ektopismos took on unprecedented dimensions, with tens of thousands forcibly displaced in the state’s effort to control its territory (Voglis Citation2020). The diplaced were communist fighters; resistance fighters (against the Axis powers as members of EAM, the National Liberation Front); members of their families; Communist Party members; communists and communist sympathizers; men and women; young, old, and children; victims of revanchist snitching; rural and urban; educated and illiterate. Importantly, tens of thousands of soldiers of suspect background (i.e., suspected of being communists, communist sympathizers, or even members of EAM) were displaced to Makronisos to serve their military conscription.

Makronisos is the emblematic island of displacement. It is here that “torture, solitary confinement, propaganda, hard labour, wretched living conditions, and, in one instance, mass killing” (Voglis Citation2002, 529) were deployed by military authorities. Ostensibly, the goal was the “rehabilitation” of the displaced “through enlightenment and education” (Voglis Citation2002, 529). Rehabilitation was measured by signing the “declaration of repentance” (dilosi). All of the displaced were forced to sign these declarations—although not all of them did (see the unrepentant soldiers in the first paragraph). What made Makronisos exceptional was the degree to which torture was involved. This model of military-led “reeducation camps” was eventually emulated in all other Civil War camps (Trikeri, Yaros) and by the British elsewhere (Malaya in 1949; Khalili Citation2013). Thus, in contrast to previous (interwar) and subsequent (the military junta of 1967–1974) eras of dissident (usually communist) island displacement in Greece when the police were in charge, the Civil War was marked by the overall leadership of the army, making the Aegean an archipelago of military forced displacement.

Plural Ecologies of Displacement

The memoirs, literary works, and letters written by the displaced contain countless references to nonhuman nature: birds, the sea, stones, (the absence of) trees and plants, flowers, water, dust, the wind, the sun, thorny bushes, fish and fishing, and pebbles. “Elements of nature” (stoiheia tis fisis), as they are often called by the displaced, are entangled with their lives in the various ways we describe next.

Displacement and Martirio: The “Satanic Alliance between Our Torturers and Nature”

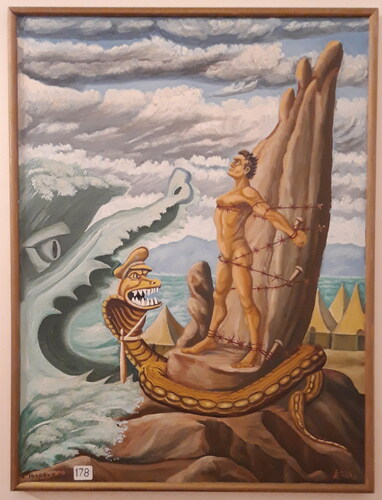

Nitsa Gavriilidou recounted from Makronisos that the women were forced outside their tents at dawn for a propaganda-cum-beating session: “Outside the cold is biting. Even the elements of nature are against us” (Γαβριηλίδου Citation2004, 46). Civilian Andreas Nenedakis, from Yaros, noted (in Συλλογικό Citation2003), “The sea crushed on [the soldiers’] boots and wetted our stuff. And it was as if the sea herself was trying to torture us” (232; see ).

Figure 1. Μακρόνησος, by former ektopismenos and self-taught artist Kostas Pouloupatis, n.d. The naked body of a man and the martiria of the sea and stone as monsters or serpents. The original hangs in the Museum of Makronisos; image used courtesy of the museum. The depiction of the army policeman as a serpent points to the “satanic alliance with nature.”

This feeling of living against the “elements of nature” was common among those who wrote about life on the islands. This emnity between the displaced and nature should not be viewed as a mere symptom of the materialities of nature but as part of the ecologies of displacement of the Civil War. In a rare admission by a post–World War II bureaucrat, in 1953 Judge Bizimis made the following observations in relaying the reasons the Hellenic Army General Staff chose Yaros as an island of displacement:

A difficult problem arose related to the transportation of the prisoners to an isolated place that would not be exposed to the danger of anarchist attack. … [Yaros] is rugged, barren, treeless, arid; life on it was considered and was indeed hell. (Χατζηπαρασκευαΐδης Citation2018, 208)

Here, the judge admitted that the islands of displacement were chosen because of the materialities of their terrain (Gordillo Citation2018). Aphroditi Mavroede-Penteleskou confirmed him:

Those who have not been to Makronisos cannot imagine the satanic alliance between our torturers and nature. The wind pounds this bare rock with relentless fury; it … creates hailstorms of sand and pebbles. … Mice nest inside our mattresses, scuttling over our bodies, making rest impossible. (Mavroede Citation[1950] 1978, 122)

The military production of nature-as-torture, or martirio as the displaced called it, is clearly discerned in the writings of the displaced: martirio of thirst, martirio of stone, martirio of sun and heat, and martirio of the sea.

The martirio of water is a thread linking all of the islands, modes, and genders of displacement, highlighting how nature was militarized by the Greek post–World War II state to subjugate the bodies and minds of its enemies. In Chios, the women talked about the “martirio of thirst … one of the most nightmarish deprivation measures” (Γαβριηλίδου Citation2004, 76–78). Athina Konstantopoulou (in Σύλλογος Πολιτικών Εξορίστων Γυναικών Citation2008, 32) remembered that “often they would be offered salt-cured herring for dinner … and no water for almost 24 h making the martirio unbearable.” Eleni Lefka (Λεύκα Citation1964) condemned the Commander for forbidding “the locals [in Trikeri] to offer us any water” (47). In waterless Makronisos and Yaros, water was carried by boat and strictly and punitively rationed: The ecologies of thirst “dried their bodies” and “hard-baked their throats” (Κορνάρος Citation1952, 18).

Makronisos was the island that defined displacement. The sea, the sun (or its absence, darkness), and stones define the ecologies of displacement here. We start from the infamous “martirio of stone.” Men and women, civilians and soldiers, under threat of or under violence were forced to carry heavy stones for various works, or even without purpose, as a means of torture. From our perspective, it is the ecologies of displacement—that is, the entanglements between “elements of nature,” their manipulation by the military personnel, and their effects on the bodies and minds of the displaced—that are of importance. Thus, it is the ecologies of the different martiria that made life hard for the displaced. The combination of excessive heat with hard manual labor under conditions of water deprivation was repeatedly mentioned (Λότσης in Βαρδινογιάννης και Αρώνης 1996; Ραφτόπουλος Citation1997; Συλλογικό Citation2003), entangled here with dust, eyes, hot air, sweat, and mud.

The heat is unbearable … 1000 men are carrying rocks. … The sun is burning them vertically. A light breeze, hot like coming from a kiln, is washing over them, and no water. … The stones on the back of their necks are wet with their sweat, which flows mudding their chests. … Their eyes are swollen from the dust. (Πικρός Citation2013, 54–55)

The absence of sunlight was also militarized as martirio, so much so that Helias Staveris (in Βαρδινογιάννης και Αρώνης Citation1996, 179), a soldier in Makronisos, noted: “A dark story begun daily in the darkness of the night. Our guards were guided by the darkness. Their success was to a large extent based on darkness.” Similarly, Aphroditi Mavroede-Penteleskou (Βαρδινογιάννης και Αρώνης Citation1996, 250–52) also noted that “what scared us the most was being taken out of the tent in the darkness. … We prayed for the light of day, for this horrible night of terror to end.” For it was during the nights that the torturers started their work of extracting declarations of repentance, mobilizing beatings, intimidation, and various disingenuous forms of torture, including through the sea.

Lambrinos recorded several martiria that deployed the “blue, tame sea that hugs the naked island” (Λαμπρινός Citation1949, 17). They would force the displaced to enter the sea barefoot until their feet got puffy and then had them run back and forth between the hill and the sea until the salt would burn their swollen and bloody feet. Or they would hogtie someone inside a wool sack and throw him in the sea and back out, again and again, “not to die, but to face the prospect of his death, lose his humanity and become an animal driven by the instinct to live” (Λαμπρινός Citation1949, 17).

Nevertheless, for the displaced, nature was not the enemy; “nature . . . does not go to war,” as Klinke (Citation2019, 7) noted in a criticism of “vitalist temptations” within contemporary political geographies on the natures of war. Arguably, the displaced did talk about the agency of nature but always in “heterogeneous … situated formations” (Pugliese Citation2015, 6), particular ecologies of displacement, which were at best “enabled” (Forsyth Citation2019) by nonhuman nature. It was their tormentors who, through nature, in “satanic alliance” with biophysical formations, turned these islands into “devilislands” (Πετρόπουλος Citation2008): “only in cooperation with anthropos does nature transform into hell” (Παλαιολόγος in Συλλογικό Citation2003, 393).

The description of nonhuman nature and the lives of the displaced so far is in line with some of the literature on nonhuman nature, albeit in a new setting. In fact, we can speak of an alliance with and through the elements of nature that were mobilized by the Greek army to create martyrs out of the thousands who went through these islands of displacement. In terms more aligned to the literature, the “elemental … materialities and processes of the physical environment” (Slesinger Citation2020, 17) were the medium through which the Greek army enacted militarized ecologies of displacement-as-martirio.

Displacement and Hope: “The Light of Day Remained Our Constant Friend and Comrade”

In this section, we show how the very same “elements of nature” that were used by the torturers were also instrumental for the displaced in coping with, reworking, and resisting (C. Katz Citation2004) their displacement. For example, the sun, which “flayed the skins” of the displaced (Ραφτόπουλος Citation1997, 8), was also welcomed as a comrade against the darkness of the night: “The light of day remained our constant friend and comrade. We dealt with everything much easier under the sun” (Σταβέρης in Βαρδινογιάννης και Αρώνης Citation1996, 180). For the women, who did not have an easier time during those endless nights, “the only thing giving us courage is the light of dawn. … The day will sooth us and keep away our soul’s and nature’s darkness” (Γαβριηλίδου Citation2004, 56).

One of the central concerns for the men and women who spent time on the islands of displacement was to “get out of here alive and strong” (Κεφαλίδου in Σύλλογος Πολιτικών Εξορίστων Γυναικών Citation2008, 58). In that sense, practices of resilience were common, as nonhuman nature was definitely entangled in ecologies of personal and collective care.

Foraging and collecting were central. In Chios, the women “burned leaves from the eucalyptus in the yard” to keep from coughing (Γαβριηλίδου in Σύλλογος Πολιτικών Εξορίστων Γυναικών Citation2008, 92). In Trikeri, they made “tea from herbs picked from the mountainsides” to alleviate dysentery, went “looking for mushrooms and wild vegetables” to cook, or collected “branches and pinecones” for kindling small fires in their tents (Theodorou Citation1986, 111, 129). They collected thorny bushes, such as afanes or asphodels, to use as pillow stuffing or under their mattresses to ward off the soil’s humidity (Γαβριηλίδου Citation2004). They would also collect rainwater to refresh themselves from the summer’s unbearable heat (Γαβριηλίδου Citation2004). Fishing or seafood foraging was also repeatedly mentioned (e.g., Theodorou Citation1986). Raftopoulos (Ραφτόπουλος Citation1997, 179) described the time when a fellow soldier he had previously helped brought him “fried sea breams” he had “caught illegally by the rocks”: “the most touching gift I have ever been given.”

The sea, militarized in the various martiria previously described, was also central in the ecologies of personal and collective hygiene. Plousia Liakata, ektopismeni to Trikeri, noted that “fortunately, the sea was nearby” and “we could wash ourselves” (Λιακατά in Βαλσαμή Citation2019, 93). Maria Meremeti (in Βαλσαμή Citation2019, 87) stressed that there were “no toilets or anything like that” in Trikeri; “we would go to the sea. … We were young women with periods.” In Makronisos, although access to the sea was strictly regulated, there are many accounts of soldiers and civilians using the sea for personal care and hygiene. Palaiologos (in Συλλογικό Citation2003) described a day he “got out the sea and lied on a smooth rock … like a dog lying in front of the fireplace, enjoying the happiness of the moment” (391). Geladopoulos (Γελαδόπουλος Citation1965, 27) described a quiet day when everyone “strolled to the sea and lit fires to boil seawater … mass laundry was always a lively and happy occasion.” Some of these practices of resilience were often collectively organized, as was often the case in the islands of displacement (Kenna Citation2001). As Theodorou described,

To each group we assigned rotating tasks … washing and bathing, fighting mice and flies. … When we caught any fish, our joy had no bounds as were able to offer fresh fish to a child. … We stuffed mattresses and pillows with dry asphodels, and with their long leaves we wove hats, mats, and baskets.

Creating arts and crafts using various found “elements of nature” such as seashells or large pebbles was a common pastime (), an ecology of emplacement (Roy Citation2017). Women in Trikeri during Christmas made “wreaths from pines and mastic branches and hung them on their tents” (Theodorou Citation1986, 139). They also made “wall hangings from driftwood and shells [and] decorated [their] tents with them or gave them to each other as presents on name-days” (Theodorou Citation1986, 123). Although these practices might seem trivial, they were not. Poet Yiannis Ritsos (1909–1990), himself an avid stone collector and painter, writing some decades after his displacement, underlined the importance of stones for the displaced, as an element of nature that is other-than-martirio (Ρίτσος Citation1975, 33–34): “The exiles … found good company in the stones, they exchanged secrets, built true friendship with the stones.” In this instance, Ritsos injects a relational ecology of human–nonhuman expression at the heart of militarized natures, an ecology of displacement that was equally present—and in the same space—as the ecologies of displacement enacted by the Greek state.

Figure 2. Arts and crafts created by the displaced. Clockwise from top left: Stone painting and etching; a vase made from seashells; decoration made from dried flowers. Items held in the Museum of Makronisos (https://pekam.org/). Photographs used courtesy of the museum.

The centrality of these ecologies to the lives of the displaced is the reason why access to nonhuman nature was often punitively withdrawn by the military authorities and why defending them, or demanding them, was so common. This element of reworking and resistance sensu (C. Katz Citation2004) is of particular importance, as it was often a collective practice. When the “martirio of thirst” was unbearable, it was “shouting and loud chants for water” that forced the Command in Chios to give the women water (Σύλλογος Πολιτικών Εξορίστων Γυναικών Citation2008, 32–33). In Trikeri, the women saw through the army commander’s “veneer of toughness” and “began to ignore his rules”; “we resumed our walks in the olive groves, looking for mushrooms and wild vegetables, and we reclaimed the clean beaches for bathing and laundry” (Theodorou Citation1986, 129–30). Collective practices were also central in resisting martiria through the same elements of nature that were mobilized by the Greek Army. In a striking passage, Marigoula Mastroleon-Zerva (Μαστρολέων-Ζέρβα Citation1986, 92) described how a group of women managed to resist and humiliate the military police that tried to torment them by having them collect thorny bushes (afanes) with their bare hands.

How could we uproot these thorny bushes without some type of tool? … That’s when we heard old Koliousena calling us, … “Girls, come close, observe how I do it, and do the same.” And she started stepping on the afana from the root upwards, cutting the dry thorns near the root. Then she would use a stone to hit the afana near the root to cut it. … We followed her lead and started cutting afanes … hitting them with stones.

To paraphrase Panourgiá (Citation2010, 199), “Where sovereign power recruits [nonhuman nature] as part of its apparatus, resistance movements appropriate this same [nonhuman nature] as means of opposition.” The state and the army could not control the ecologies of displacement coproduced on the islands by the displaced. The ecologies of care, emplacement, resilience, or resistance were coproduced from the same “elements of nature” the military enacted—ecologies of displacement-as-martirio. From stones and the sea, to the sun and thorny bushes, individually or collectively, the displaced’s ability to create homes and rework and resist their oppression was “enabled by” and “mediated through” (Forsyth Citation2019) the same “elements of nature” that were used in their martiria.

The Natures of War and the Ecologies of Displacement

Militarized spaces of displacement have been key topoi in the extended battlegrounds of World War II, the Cold War, and contemporary wars (Merriman et al. Citation2017). As such, they should be included in the study of militarized nonhuman natures. Ecologies of displacement allow for a richer, more complex, and eventually more hopeful palette of human–nonhuman nature encounters to emerge. Crucially, we documented that militarized nonhuman nature apart from the military is also “enrolled, produced and used” (Forsyth Citation2017a, 498) by convicts, exiles, detainees, men and women, soldiers, and civilians in a variety of ways.

Our analysis of the islands of displacement during and after the Greek Civil War offers another way of bodying geopolitics: mapping and recording how geopolitics are manifest, subverted, and resisted in the lives, bodies, and practices of everyday people. Displacement ecologies-as-martirio, in the dual context we gave earlier (creating martyrs and torturing), should not be considered in isolation from the wider geopolitical context into which these spaces were inserted. The Greek Civil War was the first war of the Cold War (Chomsky Citation1997) and the last war of the Cold War in Europe (Voglis Citation2002). Thus, nonhuman nature in these camps was more than weaponized or militarized—it had been “geopoliticised” (Sundberg Citation2011) to protect the West from “Communist danger.”

Nevertheless, analogous to how post-Agambenian camp studies decenter the dehumanizing aspects of refugee internment by considering informal camps (Martin, Minca, and Katz Citation2020), focusing on spaces of displacement in the context of militarized natures allows us to extend established notions of militarized nature toward a more fully relational understanding. In other words, just as makeshift camps “are created by the migrants and refugees in order to facilitate their own lives and movements” (I. Katz Citation2015, 85), so are different ecologies coproduced by the displaced to cope, resist, rework, and live life in displacement. From this perspective, ecologies of displacement can start paving a path for understanding how “humans [can] extricate themselves from these powerful entanglements of nature, technology and flesh” that are militarized natures (Klinke Citation2019, 7).

In comparison to the scholarship so far, our excavation of the various uses of nature from the diaries, novels, and other literary works of the displaced paints a more hopeful picture than the doom and gloom of “militarized nature.” This is not to diminish the effects of war on nature, nor to underestimate the ways in which the materialities of nonhuman nature enable and shape the waging of war. The ecologies of military (im)mobilities we have uncovered, however, point to a more plural understanding of the relationship between anthropos and nonhuman nature during war. They point to ecologies of care, ecologies of emplacement, artistic or aesthetic ecologies, ecologies of sustenance, and ecologies of resilience, reworking, and resistance—plural ecologies of displacement.

In the hope of contributing to the existing literature, we advance the following considerations. First, by focusing on militarized spaces of displacement we showed that the “natures of war” (Gregory Citation2016) are indeed relationally coproduced in a plethora of different ways. Because our understanding of “nature” includes recent work on the materialities of territory, terrain, and the elemental, we argue that grappling “with the question of the interaction of the material landscape with military action” (Elden Citation2021, 180) could be enriched by centering spaces of military (im)mobilities. Second, we showed that armies are not the only actors entangled in the ecologies of militarized displacement: Civilians, including women, were equally central in the army-run camps of the Aegean. Our reading of the literary works of the displaced renarrates the masculinized power geometries that often dominate accounts of militarized nature. Finally, we showed how soldiers and civilians, individually and collectively, enrolled nonhuman nature in myriad ways, coproducing ecologies of displacement-as-resistance, as-resilience, as-reworking, and emplacement. These ecologies of military (im)mobilities point to a more open reading of militarized nonhuman natures, gesturing to the ecologies “of possibility” (Martin, Minca, and Katz Citation2020, 754) the displaced, enabled by and through nature, can tear open through the geopoliticized and weaponized ecologies of the army and state.

Acknowledgments

We thank the reviewers for their suggestions that greatly improved the article. We express our gratitude to Professor Kendra Strauss for curating this collection and for her excellent stewardship of our article. Finally, we thank Makronisos Digital Museum (https://www.makronisos.org/) and the Museum of Makronisos (https://pekam.org/) for providing access to material regarding the lives of the displaced. We also thank the staff at the Museum of Makronisos for their invaluable help during our visits. Naturally, all shortcomings remain ours.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Dimitrios Bormpoudakis

DIMITRIOS BORMPOUDAKIS is a Research Fellow in the Department of Anthropology and Conservation, University of Kent, Canterbury CT2 7NZ, UK. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests include the sounds of infrastructure, the political ecologies of displacement, and neoliberal natures.

Panos Bourlessas

PANOS BOURLESSAS is a Lecturer in Human Geography in the Department of History, Archeology, Geography, Fine and Performing Arts of the University of Florence, Florence 50121, Italy. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests revolve principally around geographies of care and homeless subjectivities but expand as well toward the broader cultural geographies of our lifeworlds.

References

- Chomsky, N. 1997. World orders, Old and new. London: Pluto.

- Elden, S. 2021. Terrain, politics, history. Dialogues in Human Geography 11 (2):170–89. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820620951353.

- Forsyth, I. 2017a. A bear’s biography: Hybrid warfare and the more-than-human battlespace. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 35 (3):495–512. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775816664098.

- Forsyth, I. 2017b. Piracy on the high sands: Covert military mobilities in the Libyan desert, 1940–1943. Journal of Historical Geography 58:61–70. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhg.2017.07.007.

- Forsyth, I. 2019. A genealogy of military geographies: Complicities, entanglements, and legacies. Geography Compass 13 (3):e12422. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12422.

- Gordillo, G. 2018. Terrain as insurgent weapon: An affective geometry of warfare in the mountains of Afghanistan. Political Geography 64:53–62. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.03.001.

- Gregory, D. 2016. The natures of war. Antipode 48 (1):3–56. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12173.

- Hamilakis, Y. 2017. Archaeologies of forced and undocumented migration. Journal of Contemporary Archaeology 3 (2):121–39. doi: https://doi.org/10.1558/jca.32409.

- Jackman, A., R. Squire, J. Bruun, and P. Thornton. 2020. Unearthing feminist territories and terrains. Political Geography 80:102180. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102180.

- Jones, O. 2000. (Un)ethical geographies of human–non-human relations: Encounters, collectives, and spaces. In Animal spaces, beastly places: New geographies of human-animal relations, ed. C. Philo and C. Wilbert, 267–90. London and New York: Routledge.

- Katz, C. 2004. Growing up global: Economic restructuring and children’s everyday lives. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Katz, I. 2015. From spaces of thanatopolitics to spaces of natality. Political Geography 49:84–86. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2015.05.002.

- Kenna, M. E. 2001. The social organisation of exile: Greek political detainees in the 1930s. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers.

- Khalili, L. 2013. Time in the shadows: Confinement in counterinsurgencies. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Klinke, I. 2019. Vitalist temptations: Life, earth and the nature of war. Political Geography 72:1–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.03.004.

- Martin, D., C. Minca, and I. Katz. 2020. Rethinking the camp: On spatial technologies of power and resistance. Progress in Human Geography 44 (4):743–68. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519856702.

- Mavroede, A. [1950] 1978. Makronisos journal. Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora 5 (3):115–28.

- Merriman, P., K. Peters, P. Adey, T. Cresswell, I. Forsyth, and R. Woodward. 2017. Interventions on military mobilities. Political Geography 56:44–52. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2016.11.003.

- Panourgiá, N. 2010. Stones (papers, humans). Journal of Modern Greek Studies 28 (2):199–224. doi: https://doi.org/10.1353/mgs.2010.0423.

- Pugliese, J. 2015. Forensic ecologies of occupied zones and geographies of dispossession: Gaza and occupied East Jerusalem. Borderlands 14 (1):1–37.

- Roy, A. 2017. Dis/possessive collectivism: Property and personhood at city’s end. Geoforum 80:A1–11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.12.012.

- Slesinger, I. 2020. A cartography of the unknowable. Geopolitics 25 (1):17–42. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2017.1399878.

- Sundberg, J. 2011. Diabolic caminos in the desert and cat fights on the Rio: A posthumanist political ecology of boundary enforcement in the United States–Mexico borderlands. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 101 (2):318–36. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2010.538323.

- Theodorou, V. 1986. The Trikeri journal. In Greek women in resistance, ed. E. Fortouni, 81–119. New Haven, CT: Thelphini Press.

- Voglis, P. 2002. Political prisoners in the Greek Civil War, 1945–50: Greece in comparative perspective. Journal of Contemporary History 37 (4):523–40. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/00220094020370040201.

- Voglis, P. 2020. Controlling space and people: War, territoriality and population engineering in Greece during the 1940s. In Local dimensions of the Second World War in southeastern Europe, ed. X Bougarel, H. Grandits, and M. Vulesica, 88–105. London and New York: Routledge.

- Βαλσαμή, O. 2019. Η ανάπτυξη πολιτιστικής δραστηριóτητας απó τις ɛξóριστες στο Τρίκερι κατα την περίοδο 1949–1953. Διπλωματική Εργασία, Σχολή Κοινωνικών Επιστημών, Εληνικó Ανοιχτó Πανɛπιστήμιο

- Βαρδινογιάννης, Β. κ Π., and Π. Αρώνης. 1996. Οι μισοί στα σίδερα [Half of us behind bars]. Αθήνα: Φιλίστωρ.

- Γαβριηλίδου, Ν. 2004. Απόψε χτυπούνε τις γυναίκες [Tonight they are torturing the women]. Αθήνα: Ιδιωτική έκδοση.

- Γελαδόπουλος, Σ. 1965. Μακρόνησι [Makronisos]. Αθήνα: Ιδιωτική έκδοση.

- Κορνάρος, Θ. 1952. Γράμματα απ’ τό Μακρονήσι [Letters from Makronisos]. Βουκουρέστι: Εκδοτικό Νέα Ελλάδα.

- Λαμπρινός, Γ. 1949. Μακρονήσι [Makronisos]. Βουκουρέστι: Εκδοτικό Νέα Ελλάδα.

- Λεύκα, Ε. 1964. Γυναίκες στην εξορία [Women in exile]. Βουκουρέστι: Πολιτικές και Λογοτέχνικες Εκδόσεις.

- Μαστρολέων-Ζέρβα, Μ. 1986. Εξόριστες [Exiled]. Αθήνα: Σύχγρονη Εποχή.

- Πετρόπουλος, Γ. 2008. Μακρονησος: Εξήντα χρόνια από τη μεγάλη σφαγή [Makronisos: Sixty years from the great massacre]. Ριζοσπάστης, March 23. Accessed August 25, 2021. https://www.rizospastis.gr/story.do?id=4475728.

- Πικρός, Γ. 2013. Το χρονικό της Μακρονήσου (3η έκδοση) [The chronicle of Makronisos, 3rd ed.]. Αγ. Ανάργυροι: Εκδόσεις Δρόμων.

- Ραφτόπουλος, Λ. 1997. Το μήκος της νύχτας [The length of the night]. Αθήνα: Καστανιώτης.

- Ρίτσος, Γ. 1975. Πέτρες, κόκκαλα, ρίζες. Αντί 75:Ε1–Ε5.

- Συλλογικό. 2003. Μακρόνησος: ιστορικός τόπος [Makronisos: Historic topos]. Αθήνα: Σύχγρονη Εποχή.

- Σύλλογος Πολιτικών Εξορίστων Γυναικών. 2008. Στρατόπɛδα Γυναικών. Αθήνα: Αλφɛίος

- Χατζηπαρασκευαΐδης, A. 2018. Το αλφαβητάρι της Γυάρου. Συριανά γράμματα (περ.Β’) 2–3:208–17.