Abstract

Borders are sites of epistemic struggle. Focusing on the illegal tactic of the “pushback,” which is routinely deployed by state authorities to forcefully expel asylum seekers from European Union territory without due process, this article explores the uneven politics of knowledge that helps to support or unsettle this clandestine border violence. Drawing on long-term qualitative research on the Croatia–Bosnia border, including interviews with pushback survivors and activists, as well as a database of border violence reports, we explore the competing truth claims and epistemologies that help to conceal, or counter, the pushback regime. Informed by postcolonial perspectives and contributing to political geographies of violence, we argue that “epistemic violence” (Spivak Citation1988) is a central feature of contemporary borders. We propose that epistemic borderwork is regularly used by state authorities to silence unwanted voices, undermine insurgent perspectives, and stifle the capacity of refugees to draw attention to their own mistreatment. In opposition to this injustice, activists are documenting, mapping, and archiving pushback survivor testimony to construct a counternarrative of refusal, which subverts the harmful knowledge claims of state authorities. In doing so, refugees and activists create epistemic friction, which helps to resist the ontological violence of borders, and “pushes back” against the pushback regime.

边境是认知斗争的场所。国家经常非法运用“拒绝”策略, 以非正当的程序将寻求庇护者强行驱离欧盟。本文探讨了支持或扰乱这种隐秘边境暴力的不均衡知识政治。通过对克罗地亚—波斯尼亚边境的长期定性研究(包括对拒绝的幸存者和活动家的采访、边境暴力报告数据库), 我们探索了掩盖或对抗拒绝体制的各种真相主张和认知论。根据后殖民理论和暴力政治地理学, 我们认为, “认知暴力”(Spivak 1988)是边境的核心特征。我们建议, 国家经常通过“认知边境工作“, 来压制不同的声音、破坏反对人士的观点、扼杀难民吸引外界关注难民受虐待的能力。为了反对这种不公正, 活动人士正在记录、绘制和保存拒绝幸存者的证词, 建立反拒绝的描述, 颠覆国家当局的有害知识主张。由此, 难民和活动人士制造了认知摩擦, 有助于抵抗边境本体暴力、“反制”拒绝体制。

Las fronteras son lugares de lucha epistémica. Centrándose en la táctica ilegal del “pushback”, rutinariamente desplegada por las autoridades estatales para expulsar por la fuerza a quienes buscan asilo en el territorio de la Unión Europea, saltándose los procedimientos normales, este artículo explora las políticas desiguales de conocimiento que contribuyen a apoyar o desmontar esta violencia fronteriza clandestina. Basándonos en investigaciones cualitativas de amplia duración en la zona fronteriza entre Croacia y Bosnia, que incluye entrevistas con sobrevivientes y activistas del pushback, lo mismo que la base de datos de informes sobre la violencia fronteriza, exploramos las reivindicaciones de la verdad y las epistemologías enfrentadas al respecto que contribuyen a ocultar, o a contrarrestar, este régimen irregular de expulsión. Apoyándonos en las perspectivas poscoloniales y contribuyendo a las geografías políticas de la violencia, argüimos que “la violencia epistémica” (Spivak 1988) es un rasgo central de las fronteras contemporáneas. Planteamos que las autoridades estatales usan con regularidad el control epistémico fronterizo para silenciar las voces no deseadas, socavar las perspectivas insurgentes y sofocar la capacidad de los refugiados para llamar la atención sobre su propio maltrato. En oposición a esta injusticia, los activistas están documentando, cartografiando y archivando los testimonios de los supervivientes que han sido expulsados de ese modo, para construir una contranarrativa del rechazo, que subvierte las perjudiciales pretensiones de las autoridades estatales. Haciendo esto, los refugiados y los activistas crean una fricción epistémica, que ayuda a resistir la violencia ontológica de las fronteras, y a combatir el régimen de facto del pushback.

Palabras clave::

Important geographic research has analyzed the political technologies of border violence used against irregular migrants (see Jones Citation2016; Mitrović and Vilenica Citation2019; Tazzioli and De Genova Citation2020). Such scholarship has often explored the bio- or necro-political underpinnings that help sustain such border brutality (Davies, Isakjee, and Dhesi Citation2017; De Genova and Roy Citation2020; De Genova et al. Citation2021; Tazzioli Citation2019), as well as the role of systemic racism and the uneven deportability of people on the move (Danewid Citation2017; Isakjee et al. Citation2020; Walia Citation2021). Likewise, geographers and critical migration scholars have conducted significant research into the role of border activism and solidarity in shaping the experiences of migrants and refugees (Sandri Citation2018; Dadusc and Mudu Citation2020; Pallister-Wilkins Citation2022; Picozza Citation2021). While inspired by this scholarship, this article focuses on the politics of knowledge that helps construct but also resist the ongoing violence of borders. Drawing on field work at the Croatia–Bosnia border,Footnote1 we explore the epistemic struggle taking place to enforce and oppose the violent border praxis of the European Union (EU). In doing so, we argue that borders are not only constructed by an assemblage of barbed wire, border guards, and the bureaucracy of biometric surveillance (Amoore Citation2006), they are also shielded by epistemic violence: guarding truth claims, silencing unwanted voices, and shutting out perspectives that expose the injustice of the border itself. Such “epistemic borderwork,” where insurgent knowledge claims are denied access to credibility, acts as scaffolding around the EU’s violent border regime, and is precisely what those bearing witness to this violence are attempting to undermine.

From the treacherous waters south of Malta, to the land borders of Croatia, Hungary, and Poland; and from Ceuta in North Africa to the Turkey–Greece frontier, the “pushback” has become a dominant strategy adopted by EU states to illegally reject unwanted—and racialized—asylum seekers. As Breed (Citation2016) explained: “pushbacks constitute irregular returns of refugees or migrants to neighboring states from within a state’s territory without any form of individual screening” (21). Our research in the Balkans explores how authorities in Croatia are not only routinely expelling large numbers of would-be refugees from EU space without processing their asylum claims, but how these illegal pushbacks are often also accompanied by theft, intimidation, and severe police violence. Drawing on qualitative research in Bosnia, together with postcolonial scholarship, this article provides evidence for this systematic border brutality, focusing particularly on the “epistemic violence” (Spivak Citation1988) and “testimonial injustice” (Fricker Citation2007) that is central to the perpetuation of the EU’s violent pushback regime.

In this article we cast a spotlight on the Croatian state’s attempts to flatten the “unwanted ideology” (Bennett Citation2007, 154) of pushback survivors, whose testimonies threaten the workings of the pushback regime. Censoring the capacity of migrants and refugees to bear witness to their own suffering and admonishing their truth claims is, we suggest, a key function of contemporary borders. Put differently, epistemic injustice is central to the survival of what geographers have named “violent borders” (Jones Citation2016; Pallister-Wilkins Citation2020). Although we find that migrant bodies and epistemologies are regularly being targeted by the pushback regime, we also locate pockets of resistance that erode the state’s capacity to hide pushbacks from public knowledge. By focusing on the political work of autonomous border violence monitoring groups, we find that—set against the backdrop of the state’s epistemic injustice—there are practices that refuse its oppressive knowledge claims. We suggest that the autonomous practices of recording, archiving, and mapping border violence by grassroots activists both elevates nonhegemonic truth claims and creates what critical race scholar Medina (Citation2013) called “epistemic friction” (234), by refusing to silence the testimony of pushback survivors (see Ellison and Van Isacker Citation2021). We therefore not only focus on what the state does to admonish truth claims—which we call epistemic borderwork—we also center the epistemologies of border violence activists who attempt to do the exact opposite.

This article unfolds in five parts. After briefly discussing our research methods and epistemology, the first section outlines how pushbacks work in practice. This is based on empirical research with pushback survivors during ethnographic observations and interviews in Bosnia, as well as an archive of more than 1,500 pushback testimonies collated by grassroots border activists working in the region. Second, we draw on literature surrounding the postcolonial notion of “epistemic violence” (Spivak Citation1988) to interrogate the role that knowledge plays within geographies of violence. Combining this with geographic scholarship on “testimonial injustice” (Fricker Citation2007), we discuss how harm is caused when truth claims and epistemologies are dismissed. Building on this literature, in the third section we argue that the denigration of migrant testimony by the Croatian state works to bolster the pushback regime in a process we name epistemic borderwork. Here, we suggest that a political geography of testimonial admonishment has emerged at the EU border, where the forced illegality of asylum seeking inside the EU preordains migrant testimony as inherently untrustworthy, therefore allowing the Croatian state to undermine insurgent knowledge claims, and thus perpetuate border violence. In the fourth section, we give two detailed examples of autonomous pushback reports that outline the plurality of violence that pushback survivors face. In the final section of the article, we explore the various tactics of refusal adopted by border violence monitors to expose this violence, who—along with local Bosnian residents—are one of many groups attempting to push back against the pushback regime.

Militant Methods and Epistemologies

This article is based on a research project ongoing between 2017 and 2022 that combines a mixture of field-based qualitative methods and document analysis. The field work includes ethnographic research alongside pushback survivors and border violence monitors on the Croatia–Bosnia border, predominantly in the Una-Sana Canton of northwest Bosnia. Participant observation took place in migrant squats, informal encampments, and formal refugee camps near the Bosnian border towns of Bihac and Velika Kladuša on the EU frontier, as well as alongside grassroots solidarity organization No Name Kitchen with whom we collaborate, which provides warm food, showers, first aid, and clothes for people on the move. These ethnographic field observations, which the research team conducted over the course of a month with funding from an Antipode Foundation Scholar-Activist Grant, are combined with thirty-six interviews with pushback survivors trapped in this region, as well as nine in-depth interviews with autonomous border violence monitors, and a further set of elite interviews with Frontex and EU Commission staff. Additionally, the article is supported by analyzing government documents released by the Croatian Ministry of the Interior, as well as a substantial archive of more than 1,500 pushback testimonies that were recorded, collated, and published by the grassroots collective Border Violence Monitoring Network (BVMN), whose own methods we discuss later in this article.

De Genova (Citation2013) rightly argued that within migration research “there is no neutral vantage point” (252). Such are the high stakes and flagrant injustices of contemporary borders, that scholars, activists, and activist-scholars alike, have no choice but to be “part of the conflict, a party to the dispute … a partisan, a ‘militant’” (252). We do not claim to stand apart from our research or speak from a position of indifference. To do so would be to deny our emotional experiences, including anger and frustration, after witnessing multiple instances of border injustice in the Balkans, and hearing multiple firsthand accounts of violent pushbacks at the EU border. As Lorde (Citation1984) articulated—in line with bell hooks (Citation1996)—“anger is loaded with information and energy” (127), and geographers, too, have suggested that anger often acts as a catalyst for critical geographic research (Blomley Citation2007).

As we discuss in what follows, violent borders are reliant on an uneven hierarchy of knowledge production, with state actors often given the most credibility, and the truth claims of migrants are dismissed or ignored. As academics, we are not separate from this asymmetrical politics of credibility. We remain aware of the uneven epistemic power we hold as scholars compared to those with whom we research (Fricker Citation2007), and the ethical need to use our epistemic privilege to elevate certain voices. To be “militant” within research-activism not only requires political solidarity with migrant collaborators, but also a commitment to “distribute knowledge after the research is completed, in an equally politically minded fashion” (Apoifis Citation2017, 5; see also Clare Citation2017, Citation2019). As such, this article forms part of this effort: having a legitimacy not afforded to the border violence monitors with whom we collaborate, nor the local Bosnian activists who are often overlooked, nor the pushback survivors themselves, whose testimony is so often dismissed. Following Liboiron’s (Citation2021) important intervention against “firsting in research,” we also acknowledge that we are not the “first” to uncover this border violence: That experience is held by the pushback survivors themselves, without whom this research would not be possible. To the limited extent that an academic publication can affect change, we hope this article will direct well-needed attention to the social injustice happening at the EU’s violent borders.

The Anatomy of a Typical Pushback

We were lined up and taken one by one to be beaten by two officers at a time, from opposite sides. Beatings continue even after you fall to the floor. (Afghan pushback survivor, 2019, Bosnia)

Although each collective expulsion from EU territory is different, typical pushbacks from Croatia share a number of key characteristics. First, they almost always take place during the night along remote parts of the Bosnian and Serbian border. After confinement—sometimes for hours—inside overcrowded police vans within the EU, groups of migrants and asylum seekers are driven to the EU border by people wearing Croatian police uniforms. At the border, pushback survivors report having torches shone into their eyes while being beaten by police, who often conceal their identities by wearing balaclavas. During these assaults, police routinely use truncheons, tasers, and tear gas to incapacitate detainees, as well as fists and boots. Adding to this degrading activity further, asylum seekers are often pushed into ravines and down slopes as they are forced out of EU territory. Sometimes they are made to wade or swim through rivers at the border—a particularly dangerous activity during the freezing nights of winter. In addition to the physical harm that pushback survivors are subject to, many reported having their money stolen, their phones smashed, and the straps on their bags cut by Croatian police. They are often made to undress at the border, and have their shoes and clothes burned in front of them, thus forcing them to walk seminaked through the Bosnian or Serbian countryside in search of shelter (interviews). As one pushback survivor, who had been violently expelled from EU territory into Bosnia several times without being allowed to claim asylum, described:

They beat us. Clothes and everything get put on fire. We come back with bare feet. When they deport us, they push us. …

The preceding description of a typical pushback, which is compiled from hundreds of testimonies and interviews with displaced people trapped in Bosnia and Serbia, presents a shocking “arsenal of horrors” (Foucault Citation1977, 32), but it is by no means unusual. Border violence monitoring groups, which have been collecting data on pushbacks in the Balkans for more than five years, estimate that a projected 25,000 instances of such mistreatment were instigated by Croatian authorities in 2019 alone (BVMN Citation2020). Such is the subterfuge used by the Croatian state, however—who have flatly denied using pushbacks—that it is difficult to assess the true scale of this state-sponsored criminality. As a group of scholar-activists who have been committed to field work and observation in the region since 2017, we estimate that in the summer months especially, hundreds of refugees are facing this fate every week at the hands of the Croatian state as they attempt to make their way north into the Schengen Area of the EU, often to claim asylum (Isakjee et al. Citation2020).

Unlike premodern forms of corporeal discipline that relied on the overt “spectacle of the scaffold” to coerce biopolitical compliance (Foucault Citation1977, 32), here, violent pushbacks are often deliberately concealed from public knowledge. Great care is taken by state and suprastate organizations such as the EU to mask and deny the existence of this political technology, lest it tarnish “humanitarian” values that those organizations purport to uphold (see Isakjee et al. Citation2020). What evidence is there to support the claim that violent pushbacks are regularly being used against large numbers of asylum seekers inside the EU? After all, such inhumane activity would contravene multiple acts enshrined within the European Convention of Human Rights (especially Articles 18 and 19) and several principles of the Council of Europe, as well as international norms relating to refugees set out by the 1951 Geneva Convention (specifically Articles 32 and 33).

One growing source of evidence comes from a coalition of grassroots border activists, including the BVMN who—together with other independent organizations—have been diligently monitoring, recording, and archiving violence committed against people on the move in the Balkans since late 2016.Footnote2 As stated on the organization’s Web site, since monitoring began, “the frequency of such incidents has risen and the level of violence has reached shocking levels” (BVMN Citation2020). Unlike large-scale nongovernmental organizations that have repeatedly been accused of complicity with neoliberal border regimes (Pallister-Wilkins Citation2020; Papada et al. Citation2020), organizations such as BVMN operate autonomously and in solidarity with people on the move (Mitrović and Vilenica Citation2019; Jordan and Moser Citation2020; Ellison and Van Isacker Citation2021). Their aim is principally related to advocacy and movement building, creating a database of evidence: “thick rivers of fact” (Cmiel Citation1999, 1246) that could become useful to a range of activist and human rights organizations, making it more difficult for border agencies and governments to deny and ignore claims of abuse.

As Dadusc and Mudu (Citation2020) explained, based on their experience of border resistance groups in Italy, Greece, and the Netherlands, “[r]ather than ‘filling the gaps’ of the state or ameliorating borders and their violence, autonomous practices of migrant solidarity seek to ‘create cracks’ in the smooth operation of border regimes” (1). In this way, border violence reporting in the Balkans, which we outline next, can be read as a form of resistance to the ontological violence of borders. Such are the epistemic challenges that border violence monitors face, however, that their monitoring activity can be read as a “tactic … of the weak” used against the much more powerful “strategy” of the EU’s pushback regime (De Certeau Citation1984, 37). Central to this state strategy is not only the direct force involved in the pushback, or the technologies used, including night vision goggles, drones, dogs, and other equipment funded by the EU (Bird et al. Citation2021), but also a discourse of denialism and—as in other border regimes—the offsetting of blame to migrants themselves. As Gerst (Citation2019) identified, “contemporary political borders not only have a geographical but also an epistemic dimension” (145).

We argue that alongside the social injustice of violent border regimes is a further hidden layer of harm, what Science and Technology Studies scholars as well as postcolonial writers have called “knowledge injustice” (Egert and Allen Citation2019, 351), where witnesses to violence, who in this case literally embody the brutality of the border, have their truth claims denied or denigrated. The grassroots groups who collate, archive, and publicize the truth claims of refugees and migrants therefore help combat what Fricker (Citation2007) named “epistemic injustice” and Spivak (Citation1988) called “epistemic violence”; that is, “a type of violence that attempts to eliminate knowledge possessed by marginal subjects” (Dotson Citation2011, 236). As geographers have noted, epistemic harm has a sustaining and multiplying effect on other forms of violence (Davies Citation2022); it entrenches the “cultural,” “structural,” and “direct” forms of brutality that society tolerates (Galtung Citation1990), as witnessed in the existence of violent border regimes not only in the EU, but across the world (Jones Citation2016; Tazzioli and De Genova Citation2020). It is therefore vital to counter, or push back, against violence that is predicated on the dismissal of knowledge.

Epistemic Violence and Testimonial Injustice

At first glance, knowledge might seem too detached from the brutish harms we describe in this article: “too respectable, too academic, too genteel” (Norman Citation1999, 353). Yet as geographers have noted, violence itself “can result from epistemic and political dominance of particular narratives or understandings” (O’Lear Citation2016, 4). As postcolonial writer Spivak (Citation1988) identified, the foreclosure of certain knowledge claims is central to the Othering that Said (1973) first noted. In other words, there is violence to be found in the “asymmetrical obliteration” of colonized subjectivity (Spivak Citation1988, 280). This is far more than a matter of vague disrespect, or the trampling of local know-how. Rather, “epistemic injustice,” as the philosopher Fricker (Citation2007, 44) described, can have very real and material consequences for people whose knowledge claims are marginalized or ignored.

Epistemic violence is often entangled within complex geographies of social injustice. We see such epistemic harm mobilized in petrochemical sacrifice zones in the United States or China (Mah and Wang Citation2019; Davies Citation2022), where the “slow observations” and testimonies of pollution-affected communities are routinely sidelined, allowing racialized groups to suffer the peculiar terror—and violent consequences—of contamination (Davies Citation2018, 1549). We see it, too, in debates surrounding climate change (Mahony and Hulme Citation2018), where dominant climate science perspectives steamroll over more progressive alternatives, thus setting a path toward the “slow violence” of climate chaos (Nixon Citation2011; O’Lear Citation2016). We see it also across a variety of environmental justice struggles, where the “silencing of certain truths may have toxic consequences” (Davies and Mah Citation2020, 3). In these instances of epistemic violence, it becomes very clear, very quickly, that not all knowledge claims are rendered equal. Just as some lives—and deaths—are valued more highly than others, so, too, are some knowledge claims assigned the status of credibility, whereas others are ignored or dismissed, becoming “subjugated knowledge” (Foucault Citation1980, 81). Fricker (Citation2007) described a “credibility economy” (30), where credibility is distributed unevenly among different speakers. In other words, being “cast as a knower” and deemed worthy of “testimonial competence” (Dotson Citation2011, 243–44) is an epistemic privilege that oppressed groups, including refugees, rarely experience; especially—as in the case of pushback survivors—if their truth claims have the potential to unsettle the legitimacy of the state.

Drawing on Fricker’s (Citation2007) ideas, geographers and allied scholars have described “systematically skewed distributions of believability” (Barnett Citation2018, 319), and have located epistemic violence in faster forms, such as the workings of White supremacy in racist carceral regimes (McKittrick Citation2011); the epistemic harms of neoliberal “development” that ignores local perspectives in postconflict settings (Asher Citation2020); or the ongoing history of Black women’s truth claims being silenced and rejected by White patriarchal society (Collins Citation2000). In short, ignoring the perspectives of subaltern groups works to sustain, entrench, and normalize systemic violence: “rendering certain populations and geographies vulnerable to sacrifice … as lives and communities that are of limited value” (Davies Citation2022, 13). Turning the lens inward for a moment, geographers have situated the workings of epistemic violence within the discipline of geography itself, which often privileges certain knowledges at the expense of others (see Ahmet Citation2020). As Radcliffe (Citation2017) expanded, “racism and colonial-modern epistemic privileging are often found in student selection and progress; course design, curriculum content; pedagogies; staff recruitment; resource allocation; and research priorities and debates” (331). Here, we locate epistemic violence in the state-sponsored dismissal of witness testimony and other evidence provided by thousands of migrants and refugees who claim to have been violently and illegally expelled from EU territory.

Underneath this dismissal of migrant testimony, we can find the “misanthropic skepticism” alluded to by Maldonado-Torres (Citation2007, 245), characterized as a racist and imperial attitude that questions the very humanity of racialized people. At its most extreme, postcolonial scholars have argued that “the murder of knowledge” (de Sousa Santos Citation2014, 92)—or epistemicide—is a vital prerequisite for the mass killings conducted in the name of colonialism, patriarchy, and global capitalism: the erasure of knowledge sine qua non the erasure of people. Drawing on Foucault’s (Citation1980) notable discussions of power and knowledge, Collins (Citation2000) articulated in Black Feminist Thought that “far from being the apolitical study of truth, epistemology points to the ways in which power relations shape who is believed and why” (270). Indeed, the ability to create knowledge and testify your truth claims is inherently political. Of note to the testimonies of violence highlighted in this article, Fricker (Citation2007) identified “testimonial injustice” as a specific manifestation of epistemic harm, where “to be wronged in one’s capacity as a knower is to be wronged in a capacity essential to human value” (44). In other words, having your testimony of events dismissed, denounced, and silenced—as is the case here—is to suffer an intrinsic trauma: a polyphonic violence—once on the subaltern body, and once again on subaltern knowledge. Dotson (Citation2011) furthers this still, by suggesting “testimonial quieting and testimonial smothering” (237) are key mechanisms through which epistemic harm is enacted on marginalized groups. As we discuss later in this article, this regularly takes place at the borders of the EU.

Epistemic Borderwork

The severity of beatings was so bad that people are breaking their bones. You need to tell the UN! (Afghan pushback survivor, interviewed in Bosnia)

At its simplest, epistemic violence occurs when truth claims come into conflict with hegemonic power. Given the significance that border regimes continue to hold over contemporary geopolitics and sovereign authority, it is little surprise that borders are common sites of epistemic struggle. Based on our research in the Balkans, we suggest that a specific political geography of testimonial silencing has emerged at the EU border. The forced “illegalization” (De Genova and Roy Citation2020) of asylum-seeking within the EU gives a certain circular logic to the deployment of epistemic violence at the border: The very fact that would-be asylum seekers have to “illegally” enter EU space to claim asylum predetermines them as “criminals”; this in turn means their later testimony about being exposed to border violence at the hands of Croatian authorities—including reports of torture and forced expulsion from the EU—can be readily dismissed as untrustworthy. As one border violence monitor explained in an interview for this project, “Our asylum system is built such that people have to do illegal things in order to make a legitimate asylum claim.” Asylum seekers, in other words, are always already preordained as epistemically compromised, and thus often suffer what Fricker (Citation2007) called a “credibility deficit” (21). This circular logic is sometimes directly articulated by Croatian politicians. For example, when former president of Croatia Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović (2015–2020) was questioned about multiple reports of unlawful expulsions of irregular migrants from her country, she responded, “Illegal pushbacks? We are talking about illegal migrants, people who want to come to Croatia illegally” (cited in Human Rights Watch Citation2019). Despite a range of international laws designed to protect the rights of asylum seekers, entering EU space by “illegally” crossing a border becomes the original sin (an inchoate crime) from which the testimony of pushback survivors can be readily dismissed, even before it is given.

Despite mounting evidence that Croatia is contravening a number of fundamental human rights by systematically conducting violent pushbacks—as well as accusations from the Council of Europe (Citation2020) and even whistleblower statements from police officers addressed to the Croatian Ombudswoman (Isakjee et al. Citation2020)—the Croatian state regularly mobilizes epistemic violence as part of its border enforcement regime, conducting what we call epistemic borderwork through the systematic dismissal of thousands of stories that pushback survivors provide. The term borderwork is commonly used throughout critical border studies literature to highlight the active ways that borders are reproduced (see Rumford Citation2008; Pallister-Wilkins Citation2022). By epistemic borderwork we refer to practices designed to deny, conceal, or undermine knowledge about the violence of borders. Epistemic borderwork can take place in subtle ways, such as framing migrants and refugees as animals (Vaughan-Williams Citation2015), smugglers (Augustova, Carrapico, and Obradovic-Wochnik Citation2021), or criminals (De Genova Citation2002) who—by inference—cannot be trusted; or, as critical race scholars have identified (see inter alia Spivak Citation1988; Collins Citation2000; Dotson Citation2011; Medina Citation2013), through the racialization of migrants as less worthy of attention, especially when set against a European backdrop of structural racism (Davies and Isakjee Citation2019; De Genova and Roy Citation2020). As the following examples show, epistemic borderwork also occurs in more blatant forms of testimonial admonishment, where pushback survivors are simply accused of lying.

To take one example, a violent pushback in May 2020 that was recorded by border activists and covered in the media (see Tondo Citation2020b), described how thirty-three migrants were beaten, robbed, and spray-painted with red crosses on their heads by Croatian police as they were pushed back into Bosnia, after first being apprehended deep inside EU territory near the border of Slovenia. Faced with accusations of breaching fundamental human rights, which the Croatian Ministry of the Interior (CMI) described in a press release as “completely absurd” (CMI Citation2020), the Ministry later told the Guardian:

We find it highly probable that thousands of migrants are ready to use all means at their disposal to accomplish their goal, including giving false testimonies against police officers. (CMI Citation2020)

This statement—a typical rebuttal of the Croatian state—is epistemic violence in action: an attempt to denigrate the reliability of firsthand testimony and silence the truth claims of pushback survivors. Unlike other aspects of violent borders, where migrants are targeted through direct physical injury (Tazzioli and De Genova Citation2020), deliberate neglect (Davies, Isakjee, and Dhesi Citation2017; Gross-Wyrtzen Citation2020), or even threats of death (Stierl Citation2016), here the target of such epistemic borderwork is their capacity to know. Adding to this epistemic bordering further, the Ministry also stated in a subsequent press release that the grassroots organizations that record, archive, and publish violence reports “do not provide any information or data which can be investigated” (CMI Citation2020), thus not only framing pushback survivor testimony as unworthy, or “subjugated knowledge” (Foucault Citation1980, 7), but also disregarding the epistemology of border violence monitoring groups.

This kind of epistemic borderwork is common in statements from the CMI. For example, they similarly described a damning report published in September 2019 by the Serbian Commissariat for Refugees and Migration, that accused Croatia of torturing an Afghan minor with electric shocks before he was illegally expelled from the EU, as “factually unsubstantiated” [činjenično nepotkrijepljenih] with “no basis in reality” [nikakvo uporište u stvarnosti] (see CMI Citation2019a). This was despite being based on evidence from medical documentation, injury photographs, and the testimony of the sixteen-year-old pushback survivor involved (N1 Citation2019). Likewise, the Croatian state also claimed that a later report published by Human Rights Watch (Citation2019) presented “no concrete evidence” (CMI Citation2019b), despite being based on multiple testimonies provided by pushback survivors, and in this case, even video footage of an unlawful pushback taking place.

In those rare instances in which the Croatian state does tacitly acknowledge the presence of large numbers of injured migrants at its borders, it employs another version of epistemic borderwork, where it attempts to blame migrants themselves for the injuries they suffer, reflecting other forms of racialized institutional discourse, such as so-called Black-on-Black violence. For example, formal statements released by the CMI point to “numerous cases of violence among the migrants in Bosnia” (CMI Citation2020) as explanation for the large number of injuries reported by pushback survivors and grassroots organizations. Indeed, this victim-blaming narrative was echoed during a research interview with a representative from Frontex. In doing so, this epistemic borderwork attempts to divert attention from state culpability, and feed into the colonial story of the uncivilized other at the gates of Europe (Isakjee et al. Citation2020). Yet the scale of the pushback regime, it seems, is only matched by the Croatian state’s capacity to deny its existence: Further hidden-camera footage, obtained by BVMN and published in the The Guardian (Tondo Citation2018), showed a total of 368 people being frog-marched out of Croatia at gunpoint by police in a forested area near the Bosnian town of Lohovo (coordinates: 44.7316124, 15.9133454) in fifty-four separate pushback incidents that were recorded over an eleven-day period (). The Croatian state’s response to this footage was, in the words of BVMN (Citation2020), one of “point blank denial.”

Figure 1 7 October 2018: A still from hidden-camera footage obtained by BVMN showing a pushback in progress at the Bosnian border by men in Croatian police uniform (coordinates 44.7316124, 15.9133454). The policeman in the foreground has his gun drawn. Seconds later, the policeman in the background kicks a detainee.

Epistemic borderwork that attempts to hide the pushback regime is not the preserve of Croatia alone. Leaked e-mails from the Internal European Commission indicate that EU officials are also complicit in an “outrageous coverup” (Tondo and Boffey Citation2020) after withholding evidence that the Croatian state was regularly breaching the human rights of people on the move. Within this context, the information provided by humanitarian groups—no matter what form it takes—always falls short of a moving threshold of that which warrants investigation, existing below what Foucault (Citation1980) called “the required level of erudition or scientificity” (7), not least because the CMI is the ultimate arbiter of what counts as nonsubjugated knowledge and who counts as a knower (Dotson Citation2011). In other words, every accusation the Croatian state is faced with is rebutted through an epistemic challenge.

With the Croatian state acting as judge, jury, and executioner over what signifies “data,” “evidence,” or even “information”—and with no meaningful oversight from Frontex or other legal authorities—this epistemic borderwork creates an impasse, insulating the pushback regime from accountability. As in other racialized geographies of uneven epistemic violence, “violence does not persist due to a lack of arresting stories … but because those stories do not count” (Davies Citation2022, 3). Here, when we think through the hundreds of eyewitness testimonies from pushback survivors, which we explore in the next section, this question arises: How can such nonhegemonic stories be made to count? If the pushback regime relies on epistemic borderwork, then what means are available to resist its grip?

Assessing the Evidence: A Geography of Violence

Returning to the work of border violence monitors in the Balkans, with whom we have been collaborating in an activist-scholar capacity, we argue that their work helps to undermine the epistemic violence of the Croatian state, creating “cracks” in its hegemonic narrative. These international, antiracist groups, which engage in “autonomous migrant solidarity” (Dadusc and Mudu Citation2020), have—at the time of writing—documented more than 1,500 individual cases of pushback, each one involving the forced refoulement of between one and 189 people at a time. Croatia is responsible for 70 percent of the pushbacks documented by BVMN, with 53 percent of migrants and refugees being pushed into Bosnia, and 34 percent expelled into Serbia. The reports detail key components of the pushback, including the number of people involved, the geographic coordinates of each pushback, the number of police who participated, and the types of violence endured. Along with these individual records of pushback, No Name Kitchen and BVMN also produce detailed monthly and annual reports about border brutality that often highlight how particular police practices used against refugees and migrants evolve over time (see BVMN Citation2019). Together, these reports have become a substantive and publicly available archive of violence, a militant example of “counter-hegemonic storytelling” (Armiero et al. Citation2019, 10) that not only records the basic facts about each pushback, but crucially in terms of the border’s epistemic struggle, also documents the testimonies of those targeted for forced expulsion.

For the sake of brevity, in this article we showcase two illustrative examples of the pushback testimonies documented by activists working near the Croatian border in northern Bosnia. Both examples are typical for their brutality and reflect a repeating pattern of collective expulsion that is characteristic of pushbacks from the EU (see Augustova and Sapoch Citation2020). As one border violence monitor explained in an interview for this project, “There is a spectrum of violence, there is a range of brutality. … [But] once you get to hear it fifteen or twenty times, that’s intentionality.” In other words, there is a pattern of behavior witnessed in the documented pushbacks that indicate that this is a deliberate state strategy, as opposed to resulting from the individual whim of “bad apples” within the Croatian police force. As another border violence monitor explained, “What the Croatian police is doing is definitely something more systematic.” In other words, the “Black sheep argument,” as she described it, which Croatian authorities might attempt to use as part of their epistemic borderwork, can therefore be dismissed (see Human Rights Watch Citation2019).

Together, these pushback reports present a geography of violence that is archived and mapped on the BVMN Web site. Our aim here is not to analyze the specific biopolitical practices and technologies of border enforcement used by EU authorities. Rather, we focus on the politics of knowledge that helps to enforce, but also—as the remainder of this article argues—resist the violence of the pushback regime. Central to this resistance are the border violence reports that elevate the testimonies of pushback survivors; knowledge claims that, as we have seen, the state attempts to silence. The two example pushbacks that follow are a small part of a much wider assemblage of testimonies that reflect what Medina (Citation2013) called “resistant epistemic agency” (302). As such, the pushback survivor testimony that is made visible through the solidarity actions of border violence monitors, becomes insurgent knowledge that pushes back against the power of the state’s epistemic borderwork.

Example Pushback Reports

Pushback 1 (Coordinates: 44.85946948792225, 15.733665723998001). The first example—dated 20 June 2019—describes how a family of nine people from Afghanistan, between the ages of six and thirty-four, were detained at gunpoint by police at 3:00 a.m. near the Croatian village of Željava. The family, who had set out by foot from the Bosnian city of Bihać with the intention of claiming asylum in the EU, were refused this legal right, being told by a policeman after detention, “Here is not your house.” As one of the respondents explained, “The police only laughed then they slapped me in the face.” According to the violence reports collated by BVMN, this is not unusual; for example, in 2018, 68 percent of pushback survivors expressed their intention to ask for asylum before being forcibly expelled from EU space (BVMN Citation2020). Instead of having their asylum claims processed, their phones were confiscated, their money was stolen (2,700 Euros), and several members of the family were subjected to physical violence. The police—who numbered nine or ten at the time of detention—used fists, batons, and boots during these assaults. As one respondent explained in the report, “Any time we tried to talk to the police they gave us one punch and one kick in the back in the head.” After the asylum seekers were driven in a police van back to the Bosnian border, three police officers started a fire and demanded the asylum seekers burn all their possessions, which included sleeping bags, shoes, and fifteen days’ worth of food. These supplies were necessary to complete the clandestine journey from northwest Bosnia toward asylum in the EU via Croatia and Slovenia, a perilous trek often sardonically referred to by research participants as “The Game” (see Minca and Collins Citation2021). In the words of one respondent interviewed in the report:

They told us “Throw your bag in the fire.” We didn’t throw our bags in the fire, but they started beating us, so we threw it in. They didn’t care, they just said “Throw it.” They even wanted our jackets, so we had to throw our jackets in too.

Unlike during other pushbacks documented by BVMN, the two children involved, aged six and seven, were not physically injured by the police. The children were clearly traumatized by what they had witnessed, however. The report explains that “since the time that this pushback occurred, one of the girls in the group has wet the bed every night.” Indeed, children are regularly among the refugees and migrants illegally expelled by Croatian authorities: Of the more than 1,500 violence reports documented by BVMN, the number of pushbacks where minors are involved fluctuated between 46 percent in 2018 and 53 percent in 2021.

Pushback 2 (Coordinates: 45.240047, 15.88256). As a second example, a violence report, dated 7 March 2020, describes how a group of six Moroccan men between the ages of eighteen and twenty-four were apprehended by police at 12:30 a.m. in the forest near the Croatian village of Crni Potok. After their belongings and money were stolen, the detainees were beaten by Croatian police with fists and batons. This resulted in the broken arm of one group member, before they were all expelled from EU territory into Bosnia. In the words of one of the pushback survivors, who was interviewed in the report:

When the police arrived, I was saying to them “Please, peace with us, peace,” but they weren’t interested in that and pulled guns on us. I heard that they loaded it. One of the officers came to me with his gun and put it directly on my head while he was shouting on me [sic], “Who’s the leader? I know it’s you.” … The officers ordered to us to make a line. We were sitting on the knees on the ground. The police put all our phones, money, power banks and food they found in a big [garbage bag]. After that, we were beaten with iron rods.

The interviewee went on to explain how the “team of police took also our clothes to make us cold.” Being forced to undress in this way during pushbacks is a regular strategy used by Croatian police, and like most nights in early March in this part of Croatia, that evening temperature was close to freezing: “This is torture,” explained one of the pushback survivors interviewed in the report. Indeed, an annual document published by BVMN stated that over 80 percent of pushbacks documented in 2019 contained testimony of violence that constituted breaches of international law relating to “torture or cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment” (see BVMN Citation2019). In this pushback, which was recorded by No Name Kitchen, six group members “were left in just their underwear in front of the officers who were described as laughing while watching them” (No Name Kitchen Citation2020). By around 4 a.m., having been driven in a police van to the border, the men were thrown into the Glina River, which marks the geopolitical boundary between Croatia and Bosnia, and were forced to swim to the other side: “They carried me until the river where an officer in ski mask was and threw me in [the river].” As this pushback suggests, humiliation, theft, violence, and exposure to the elements are common characteristics of these illegal expulsions from the EU (Augustova and Sapoch Citation2020; Augustova, Carrapico, and Obradović-Wochnik Citation2021).

Epistemic Friction

As these accounts show, the pushback is EU border policy laid bare. Gone are the violent euphemisms of “hostile environments” (Jones et al. Citation2017) or the “hotspot approach” (Mitchell and Sparke Citation2020); gone, too, are the subtleties of “violent inaction” (Davies, Isakjee, and Dhesi Citation2017), or deliberate state abandonment (Dhesi, Isakjee, and Davies Citation2018; Gross-Wyrtzen Citation2020); gone also are the technological niceties of biometric surveillance (Amoore Citation2006). Instead, in the testimonies of pushback survivors we find border policy crystallized in all its dumb brutality: a distilled geopolitics of violence. The pushback, as witnessed in the preceding examples, has more in common with premodern banishment than contemporary sophisticated forms of border management. Foucault (Citation1977) described how banishment was often “preceded by public exhibition and branding,” and how “fines were sometimes accompanied by flogging” (33). All of these tropes ring true for the pushback regime: the theft of money (fines), the routine beatings (flogging), and even the “branding” of flesh through bruises, scars, and spray paint—each echoing this archaic form of discipline and control. Yet the pushback regime is anything but a “public exhibition” (33). Indeed, such is the bloody, bare-faced, and crass nature of this organized violence, which runs counter to EU laws and so-called European values (Isakjee et al. Citation2020), that epistemic borderwork becomes a vital practice for state authorities, shielding it from public knowledge. On the other side of this epistemic struggle, however, as we have seen in the preceding accounts, are the stories of people who have lived through it. Their testimony, and the capacity of grassroots border violence monitors to elevate and publicize their experiences, works to resist the epistemic borderwork of the EU’s pushback regime.

The violence reports collated by BVMN, and especially the words of those interviewed within them, are an example of what Mignolo (Citation2011, 273) called “epistemic disobedience”: acts that gnaw away at the dominant discourse of the border. Such “guerilla narratives” (Armiero et al. Citation2019, 10) place value on the experiences and epistemologies of the oppressed. As such, the violence reporting becomes a way of resisting this illegal activity. Crucially, the reports are coproduced by grassroots activists with pushback survivors, with care taken to not reveal the identities of those featured in the reports, and time taken to actively listen to what they say. The violence reports are produced through “political listening,” referring to a mode of listening that creates the possibility of resisting “oppression [that] happens partly through not hearing certain kinds of expressions from certain kinds of people” (Bickford Citation1996, 129). As geographers have argued, “like storytelling, listening is political” (Pascoe et al. Citation2020), and the process of listening is itself a vital aspect of border violence monitoring. For example, a border violence monitor who had listened to the testimony of hundreds of pushback survivors and written more than fifty violence reports, explained how:

So many people have these stories with them when they come back from the borders and they have such few outlets to have people to listen to them. And if we’re not listening to these stories and if we are not writing them down, then it is very likely that nobody hears them. (Border violence monitor, Velika Kladuša 2019)

Listening, recording, and taking seriously the knowledge claims of border violence survivors also works to counter the “predatory discourse” (Bennett Citation2007, 151) that Croatian authorities use to hide the pushback regime, a regime that not only attempts to damage the bodies of people on the move, but also their capacity to draw attention to their own mistreatment.

The brutality described by pushback survivors not only attests to the harms of contemporary borders and their racial underpinnings. The recounting of these stories themselves is also an affirmation of resistance and agency (Pascoe et al. Citation2020). In a context where epistemic borderwork seeks to shield state authorities from scrutiny, elevating the testimonies of pushback survivors becomes a means of political defiance, guaranteeing what Medina (Citation2013) called “the constant epistemic friction of knowledges from below” (293). This friction, of alternative truth claims and insurgent knowledge, might not overturn the EU’s pushback regime in one decisive moment of abolition, but it nevertheless allows the subjugated testimony of pushback survivors to puncture, trouble, and undermine normative border narratives; narratives not only produced by the Croatian state through their epistemic borderwork, but also reproduced and encouraged by EU organizations such as Frontex, through their words, maps, and practices (van Houtum and Lacy Citation2020). The recording, publicizing, and mapping of the pushback survivors’ truth claims—as shown earlier and discussed in what follows, ensures that “the experiences and concerns of those who live in darkness and silence do not remain lost and un-attended, but are allowed to exert friction” (Medina Citation2013, 293). Put simply, operating against the state’s epistemic borderwork are acts of epistemic resistance. In what remains of the article, we detail two important ways in which this friction is exerted by border violence monitors, focusing on practices of archiving and mapping.

Archives of Refusal

The two example pushbacks detailed earlier show the plurality of violence that people on the move are regularly exposed to during expulsions from Croatia. Compiled on the BVMN Web site,Footnote3 together with hundreds of other violence reports, they collectively form a counterhegemonic archive of the border: a catalog of alleged crimes committed by EU authorities. This archival record of violence can be filtered by date, country of pushback, keyword search, or whether minors were involved. Each search unearths new stories of pushback, and the great depths to which EU authorities have sunk to exclude unwanted asylum seekers. Within the archive, for example, are multiple reports of police dog bites (5.7 percent; e.g., coordinates 44.830972, 15.764639), gunshots (10.4 percent; e.g., coordinates 45.0922077, 15.791496199999983), and “chain pushbacks” (17.0 percent; e.g., coordinates 45.033085, 15.759291), where multiple EU countries are implicated. A common chain pushback route, for example, involves asylum seekers being apprehended in northeast Italy, before being covertly passed between Italian, Slovenian, and Croatian police forces, and then finally being pushed across the EU border into Bosnia. As one border violence monitor explained, “If we can make this information public and presentable in one place, so [journalists] can read it, and have a better understanding for when they make their own reports, this is very important.” Like other archives, the reports often include partially redacted documents, diagrams (of injuries), and photographs: of scars, wounds, and bruises; the body itself becoming its own reluctant repository of state violence; the politics of the EU border traced and transcribed onto subaltern bodies. Each new border violence report that is recorded and archived on the BVMN Web site increases the friction that can be brought to bear on the state’s epistemic borderwork.

Postcolonial anthropologist Stoler (Citation2002) cautioned that “scholars should view archives not as sites of knowledge retrieval, but of knowledge production” (87). In other words, instead of mining archives—or indeed the lives of migrants (see De Genova Citation2002, 423)—in an extractive way, we should be more ethnographic in our approach, and move “from archive-as-source to archive-as-subject” (Stoler Citation2002, 87). Here we take up this challenge by focusing on the political work that the BVMN’s border violence archive does. Historical geographers have often suggested that as a zone of academic inquiry, archives are “a space of ‘traces’, ‘fragments’ and ‘ghosts’” (Hodder Citation2017, 45). Here, however, the growing assemblage of pushback reports form a “living” archive of sorts, not haunted by a past that has long faded from view and must be skillfully exhumed by historians, but an archive enlivened by an ongoing present that the state does everything in its power to conceal. Preserving and curating this growing archive of border violence is therefore a political act—an “epistemological experiment” (Stoler Citation2002, 87) that challenges normative understandings of the border.

With the politics of knowledge playing a key role in this border struggle, border violence monitors are very aware of the importance of their own epistemology in creating this archival data. For example, one border violence monitor described how she takes “a technical approach to the whole process” to create the most rigorous data. Similarly, another border violence monitor described how the systematic approach of documenting border violence is “a pseudo academic thing,” making the information more trustworthy. As he explained:

We’ve really built them up into something, you know, credible, reliable, and factual. I think that we reworked the methodology that we conduct the reports with … we’ve been doubling down on training people, we are doing the reports to make them more consistent.

Indeed, the desire to “become more professional” as another border violence monitor described, is in direct response to the Croatian state’s epistemic borderwork where it routinely attempts to dismiss these violence reports as unreliable.

In December 2020, BVMN published a 1,500-page Black Book of Pushbacks that documented the violence suffered by more than 12,000 people during violent removals from the EU over the previous four years. Described as a “definitive archive of evidence,” the two-volume book was presented to the EU commission in Brussels (Tondo Citation2020a). By documenting pushback testimony and making it public, border violence monitors perform what Medina (Citation2013) described in his book Epistemic Resistance as “radical solidarity” (3), by which he meant actions that take seriously nonhegemonic perspectives and are centered on “an ethics and a politics of acknowledgement” (Medina Citation2013, 267). As geographers have argued, borders are not only sites of hostility for marginalized groups; they can also become spaces of refusal. Jones (Citation2012) described how “a space of refusal is a zone of contact where sovereign state practices interact with alternative ways of seeing, knowing, and being” (687). This database, and the more than 1,500 pushback testimonies that have been systematically documented within, become an archive of refusal: The chronicled pushbacks stand in stark opposition to—and create friction with—the Croatian state’s epistemic borderwork and the violent complicity of the EU.

Maps of Refusal

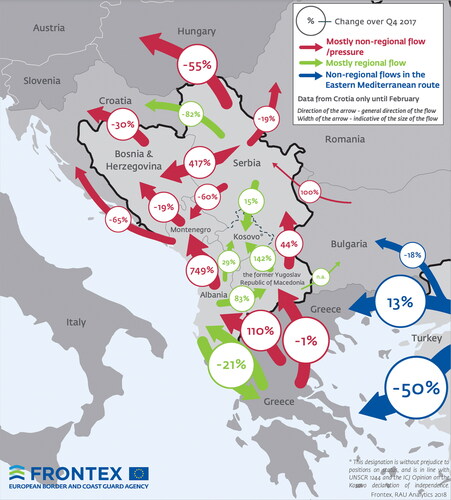

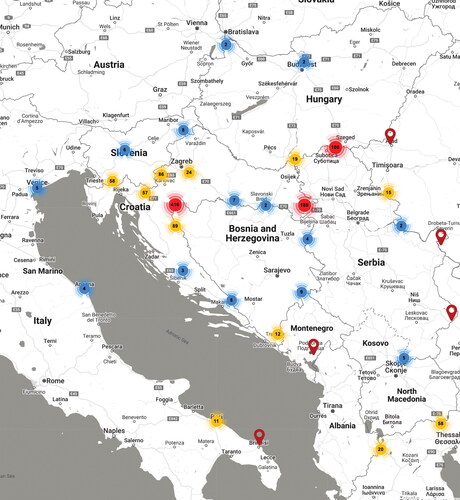

Another important way that border violence monitors create friction with the state’s epistemic borderwork is through mapping. Each archived pushback is accompanied by coordinates that pinpoint the geographic location where the violence took place. Using these data, the BVMN archive is translated into an interactive map documenting each pushback. As one border violence monitor explained, “The whole approach we have for this border violence thing is about finding the patterns, and like, finding the systematic in it, and you have a clear image of a pushback process.” Much like archives, “maps are embodiments of power” (Firth Citation2014, 156), and compared to the Frontex maps of the region (), which present migration as a threat, the BVMN’s interactive map creates a “counter-cartography” where the violence of the border regime takes center stage (Dalton, Mason-Deese, and Counter Cartographies Collective Citation2012). Like the Frontex map of the western Balkans shown in , formal migration maps have been described as “cartography [that] peddles a crude distortion of undocumented migration that smoothly splices into the xenophobic tradition of propaganda cartography” (van Houtum and Lacy Citation2020, 196). The large red, green, and blue invasion arrows representing the “flow” and “pressure” of migrants, which are often found on government maps, are themselves a cartographic form of epistemic borderwork, and displace the epistemologies of the very people being mapped. Like the archive of refusal, the BVMN maps help to counter this erasure, creating cartographic friction.

Figure 2 Map showing the “flow/pressure” of migrants in the so-called Balkan Route, with no mention of violent pushbacks. This is a cartographic example of epistemic borderwork (Frontex Citation2018, 7).

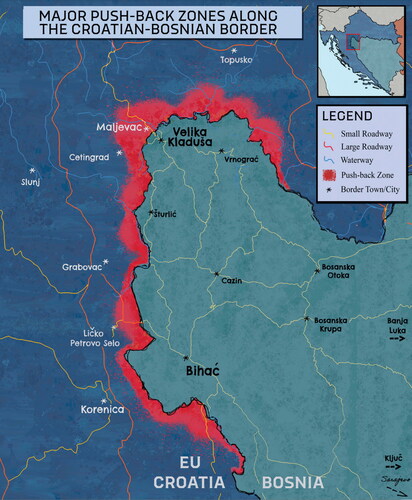

This countercartography created through border violence monitoring unbalances the regime of legitimation that Frontex and other state actors attempt to fashion with formal maps. As Dalton, Mason-Deese, and the Counter Cartographies Collective (Citation2012) argued, alt-mapping or “counter-maps” (Peluso Citation1995, 396) can be used as a form of militant research (Ellison and Van Isacker Citation2021), where “counter-maps [become] checks on power whose aim is to contest the oppressive message, application and implications of hegemonic cartographic depictions” (van Houtum and Lacy Citation2020, 208). The BVMN maps refuse the hegemonic depiction of migration, and instead of using arrows to denote movement, they show data points that can be expanded, linking them to the full archived violence report for each location (see ). They also produce maps that subvert the nature of standard border maps entirely, by focusing on the “major push-back zones” themselves (see ).

Figure 3 Open-source map of refusal created by BVMN (Citation2020) showing geographic instances of pushback by border authorities.

Figure 4 Map of refusal showing the location of major pushback zones along the Croatian–Bosnian border (BVMN Citation2019).

The production of archives and maps of refusal by border violence monitors echoes the epistemology of militant research, an approach that not only produces radical and transformative knowledge, but also knowledge that is “‘useful’ to those with whom you are struggling” (Clare Citation2017, 378). As such, the border violence archive, which is carefully recorded, transcribed, uploaded, geotagged, and mapped, can be read as a form of militant bureaucracy, a sharp counterpoint or resistive shadow to the bureaucratic violence of neoliberal border regimes (see van Houtum and Lacy Citation2020). As Ellison and Van Isacker (Citation2021) astutely observed, producing such nonhegemonic border knowledge can “reframe not only understandings and imaginings of borders in many different fora (even those stacked against autonomous movements), but the ways in which they can be resisted” (368).

The work of border violence monitors is a form of epistemic resistance, denoting “the use of our epistemic resources and abilities to undermine and change oppressive normative structures” (Medina Citation2013, 3). McWhorter (2009, 394) described “insurrections of subjugated knowledges,” and the archive and maps produced by BVMN, containing the words, descriptions, testimonies, and truth claims of pushback survivors, is exactly that. Together, they create a counter-pushback geography that undermines the pushback regime, becoming a powerful example of epistemic friction. The utility of this database is therefore flexible rather than, for example, as legal testimony to be used to seek restitution of rights for individuals. Activists who use testimony are not merely translators or presenters of information, but actively repurpose narratives to become part of a wider political project (see Patel Citation2012). In short, set against the horror of the pushback regime and the epistemic violence that underpins it are also acts of resistance: The testimony of pushback survivors and the work of border violence monitors creates epistemologies of refusal that can sabotage the state’s epistemic borderwork.

Conclusion: On the Limits of Data

This article has shown how borders are not only a product of violence, geography, and geopolitics, they are also epistemic constructions. Refugees and migrants at the EU border not only face the direct physiological injuries of the pushback regime—the traces of which are often left on their bodies—they also experience the violence of testimonial admonishment and what we have called epistemic borderwork.

It is precisely because violent pushbacks break the covenant of “acceptable” norms of biopolitical behavior that state authorities need them to remain hidden. The attempt to invalidate, ignore, and undermine pushback survivor testimony speaks to the determination of European states to buttress their liberal façades and humanitarian pretentions (Isakjee et al. Citation2020). Every effort is made to hide and deny this social injustice. The “misanthropic skepticism” (Maldonado-Torres Citation2007, 245) that survivors of border violence are subjected to also serves to further dehumanize them as racialized subjects. And yet border violence monitoring, as we have seen, plays an important role in resisting this harm. Against a backdrop of epistemic borderwork is an assemblage of evidence—including whistleblower accounts from Croatian police, observations from large humanitarian groups, and even statements from the Council of Europe—but also archives and maps of refusal coproduced by autonomous activists and people on the move. Alongside this, local Bosnian citizens also bear witness to the aftermath of border violence and create vital spaces of solidarity and support for pushback survivors. Together, these resist the epistemic injustice of the pushback regime. This assemblage of insurgent narratives about border violence are not monolithic, but instead provide “counter-evidence” (Ellison and Van Isacker Citation2021, 357) that resonates with what Klein (Citation2015) called “blockadia,” where multiple perspectives, movements, and insurgencies from disparate actors across the world become “interconnected pockets of resistance” (253). In this way, the epistemic friction created by whistleblower statements, migrant testimonies, local observations, and border violence reports become mechanisms to counter the epistemic borderwork of the state, and the inherent violence it enforces.

Border violence monitors provide a radical alternative to the systemic violence of borders. Such hopeful work is important; as de Sousa Santos (Citation2014) argued in the introduction to Epistemicide, “Nothing is so oppressive as to eliminate the sense of a nonoppressive alternative” (x). At the same time however, we acknowledge that data alone will never be enough to correct issues that are political in nature (Davies and Mah Citation2020). As with environmental justice disputes—where even large-scale, real-time, big data measurements of pollution repeatedly fail to halt its spread—the creation of ever-more information about border violence will only get us so far. Put differently, contributing to a “data treadmill” (Shapiro et al. Citation2020, 301) about the pushback regime will not combat its structural injustice unless it is paired with political change. No hypothetical border violence sensor or panoptic humanitarian CCTV—even if such a thing existed—would be enough to dissuade the persistence of a pushback regime that is so thoroughly underpinned by neocolonial power structures, systemic racism, and the epistemic violence of the border. Yet as we have shown, holding a torch to the violence of the border creates a friction, and through that friction an opportunity to push back against the pushback regime. Mbembe (Citation2019) suggested that “the idea according to which life in a democracy is fundamentally peaceful, policed, and violence-free does not stand up to the slightest scrutiny” (16). In this article we suggest that to hold governments to account and combat epistemic borderwork, scrutiny is exactly what is needed. The militant bureaucracy and epistemic friction generated through archives of refusal and countercartography that border violence monitoring provides plays a crucial role in bringing us closer to this aim and creating less violent geographies.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (30.5 KB)Acknowledgments

This publication would not have been possible without the generosity of many people. We are indebted to No Name Kitchen and BVMN, and we would particularly like to thank Karolína Augustová, Jack Sapoch, Simon Campbell, and Bruno Álvarez for their ongoing support with the wider research project. We also thank the reviewers and editors of the Annals of the American Association of Geographers who helped strengthen this article. We are extremely grateful to the many people who shared their knowledge and experiences with us in Serbia and Bosnia. This article is written in solidarity with all people affected by violent border regimes.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher's site at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2022.2077167.

Notes

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Thom Davies

THOM DAVIES is an Associate Professor in the School of Geography, University of Nottingham, Nottingham NG72QL, UK. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests include refugees, environmental justice, toxic geographies, and violence.

Arshad Isakjee

ARSHAD ISAKJEE is a Lecturer in the Department of Geography and Planning, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L697ZT, UK. E-mail: [email protected]. His research lies at the intersection of borders, race, and migration.

Jelena Obradovic-Wochnik

JELENA OBRADOVIC-WOCHNIK is a Senior Lecturer in Politics and International Relations at the School of Social Sciences and Humanities, Aston University, Birmingham B4 7ET, UK. E-mail: [email protected]. Her research includes violence, borders, and refugee support in southeast Europe.

Notes

1 Bosnia is used in this article as a recognizable informal shorthand for Bosnia and Herzegovina and is widely used by our respondents and research participants in the Balkans.

2 BVMN is comprised of grassroots groups including No Name Kitchen, Aid Brigade, Balkan Info Van, Collective Aid, Escuela con Alma, Fresh Response, [Re:]ports Sarajevo, and Rigardu, as well as independent border violence monitors working in the region.

3 See www.borderviolence.eu

References

- Ahmet, A. 2020. Who is worthy of a place on these walls? Postgraduate students, UK universities, and institutional racism. Area 52 (4):678–86. doi: 10.1111/area.12627.

- Amoore, L. 2006. Biometric borders: Governing mobilities in the war on terror. Political Geography 25 (3):336–51. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2006.02.001.

- Apoifis, N. 2017. Fieldwork in a furnace: Anarchists, anti-authoritarians and militant ethnography. Qualitative Research 17 (1):3–19. doi: 10.1177/1468794116652450.

- Armiero, M., T. Andritsos, S. Barca, R. Brás, S. Ruiz Cauyela, Ç. Dedeoğlu, M. Di Pierri, L. d O. Fernandes, F. Gravagno, L. Greco, et al. 2019. Toxic bios: Toxic autobiographies—A public environmental humanities project. Environmental Justice 12 (1):7–11. doi: 10.1089/env.2018.0019.

- Asher, K. 2020. Fragmented forests, fractured lives: Ethno‐territorial struggles and development in the Pacific Lowlands of Colombia. Antipode 52 (4):949–70. doi: 10.1111/anti.12470.

- Augustova, K., and J. Sapoch. 2020. Border violence as border deterrence: Condensed analysis of violence push-backs form the ground. Movements 5 (1):219–31.

- Augustova, K., H. Carrapico, and J. Obradović-Wochnik. 2021. Becoming a smuggler: Migration and violence at EU external borders. Geopolitics 1–22. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2021.1961223.

- Barnett, C. 2018. Geography and the priority of injustice. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108 (2):317–26.

- Bennett, K. 2007. Epistemicide! The tale of a predatory discourse. The Translator 13 (2):151–69. doi: 10.1080/13556509.2007.10799236.

- Bickford, S. 1996. The dissonance of democracy. London: Cornell University Press.

- Bird, G., J. Obradović-Wochnik, A. Beattie, and P. Rozbicka. 2021. The “badlands” of the “Balkan Route”; policy and spatial effects on urban refugee housing. Global Policy 12 (Suppl. 2):28–40. doi: 10.1111/1758-5899.12808.

- Blomley, N. 2007. Critical geography: Anger and hope. Progress in Human Geography 31 (1):53–65. doi: 10.1177/0309132507073535.

- Border Violence Monitoring Network (BVMN). 2019. Torture and cruel, inhumane, or degrading treatment of refugees and migrants in Croatia in 2019. Accessed December 25, 2020. https://www.borderviolence.eu/wp-content/uploads/CORRECTEDTortureReport.pdf.

- Border Violence Monitoring Network (BVMN). 2020. Discrediting NGOs will not die the evidence at the EU’s external borders. Press release. Accessed December 25, 2021. https://www.borderviolence.eu/discrediting-ngos-will-not-hide-the-evidence-at-the-eus-external-borders/#more-14604.

- Breed, D. 2016. Abuses at Europe’s borders: Forced migration review. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://www.fmreview.org/sites/fmr/files/FMRdownloads/en/destination-europe/breen.pdf.

- Clare, N. 2017. Militantly “studying up”? (Ab)using whiteness for oppositional research. Area 49 (3):377–83. doi: 10.1111/area.12326.

- Clare, N. 2019. Can the failure speak? Militant failure in the academy. Emotion, Space and Society 33:100628. doi: 10.1016/j.emospa.2019.100628.

- Cmiel, K. 1999. The emergence of human rights politics in the United States. The Journal of American History 86 (3):1231–50. doi: 10.2307/2568613.

- Collins, P. H. 2000. Black feminist thought. London and New York: Routledge.

- Council of Europe. 2020. Croatian authorities must stop pushbacks and border violence, and end impunity. Accessed December 20, 2022. https://www.coe.int/en/web/commissioner/-/croatian-authorities-must-stop-pushbacks-and-border-violence-and-end-impunity.

- Croatian Ministry of the Interior (CMI). 2019a. Reagiranje na optužbe Komesarijata za izbjeglice i migracije Republike Srbije [Responding to the allegations of the Commissariat for Refugees and Migration of the Republic of Serbia]. Press release, Accessed November 11, 2021. https://mup.gov.hr/vijesti-8/reagiranje-na-optuzbe-komesarijata-za-izbjeglice-i-migracije-republike-srbije/284701.

- Croatian Ministry of the Interior (CMI). 2019b. Response of the Ministry of the Interior to the report of Human Rights Watch. Press release, Accessed March 17, 2022. https://mup.gov.hr/news/response-of-the-ministry-of-the-interior-to-the-report-of-human-rights-watch-285861/285861.

- Croatian Ministry of the Interior (CMI). 2020. Reaction of the Croatian Ministry of the Interior to the article of the British news portal The Guardian. Press release, Accessed April 10, 2022. https://mup.gov.hr/news/response-of-the-ministry-of-the-interior-to-the-article-published-on-the-online-edition-of-the-british-daily-newspaper-the-guardian/286199.

- Dadusc, D., and P. Mudu. 2020. Care without control: The humanitarian industrial complex and the criminalisation of solidarity. Geopolitics 1–26. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2020.1749839.

- Dalton, C., L. Mason-Deese, and Counter Cartographies Collective. 2012. Counter (mapping) actions: Mapping as militant research. ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 11:439–66.

- Danewid, I. 2017. White innocence in the Black Mediterranean: Hospitality and the erasure of history. Third World Quarterly 38 (7):1674–89. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2017.1331123

- Davies, T. 2018. Toxic space and time: Slow violence, necropolitics, and petrochemical pollution. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108 (6):1537–53.

- Davies, T. 2022. Slow violence and toxic geographies: “Out of sight” to whom? Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 40 (2):409–27. doi: 10.1177/2399654419841063.

- Davies, T., and A. Isakjee. 2019. Ruins of empire: Refugees, race, and the postcolonial geographies of European migrant camps. Geoforum 102:214–17. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.09.031.

- Davies, T., A. Isakjee, and S. Dhesi. 2017. Violent inaction: The necropolitical experience of refugees in Europe. Antipode 49 (5):1263–84. doi: 10.1111/anti.12325.

- Davies, T., and A. Mah. 2020. Toxic truths: Environmental justice and citizen science in a post-truth age. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

- De Certeau, M. 1984. The practice of everyday life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- De Genova, N. P. 2002. Migrant “illegality” and deportability in everyday life. Annual Review of Anthropology 31 (1):419–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.31.040402.085432.

- De Genova, N. 2013. “We are of the connections”: Migration, methodological nationalism, and “militant research.” Postcolonial Studies 16 (3):250–58. doi: 10.1080/13688790.2013.850043.

- De Genova, N., and A. Roy. 2020. Practices of illegalisation. Antipode 52 (2):352–64. doi: 10.1111/anti.12602.

- De Genova, N., M. Tazzioli, with C. Aradau, B. Bhandar, M. Bojadzijev, J. D. Cisneros, N. D. Genova, J. Eckert, and E. Fontanari. 2021. Minor keywords of political theory: Migration as a critical standpoint. A collaborative project of collective writing. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 1–95. doi:10.1177/2399654420988563

- de Sousa Santos, B. S. 2014. Epistemologies of the South: Justice against epistemicide. Boulder, CO: Paradigm.

- Dhesi, S., A. Isakjee, and T. Davies. 2018. Public health in the Calais refugee camp: Environment, health and exclusion. Critical Public Health 28 (2):140–52. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2017.1335860.

- Dotson, K. 2011. Tracking epistemic violence, tracking practices of silencing. Hypatia 26 (2):236–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-2001.2011.01177.x.

- Egert, P. R., and B. L. Allen. 2019. Knowledge justice: An opportunity for counter-expertise in security vs. science debates. Science as Culture 28 (3):351–74. doi: 10.1080/09505431.2017.1339683.

- Ellison, J., and T. Van Isacker. 2021. Visual methods for militant research: Counter-evidencing and counter-mapping in anti-border movements. Interface: A Journal on Social Movements 13 (1):349–74.

- Firth, R. 2014. Critical cartography as anarchist pedagogy? Ideas for praxis inspired by the 56a infoshop map archive. Interface: a Journal for and about Social Movements 16 (1):156–84.

- Foucault, M. 1977. Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. London: Penguin.

- Foucault, M. 1980. Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings. New York: Pantheon.

- Fricker, M. 2007. Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Frontex. 2018. Frontex western Balkans quarterly, Accessed February 22, 2022. https://frontex.europa.eu/assets/Publications/Risk_Analysis/WB/WB_Q1_2018.pdf.

- Galtung, J. 1990. Cultural violence. Journal of Peace Research 27 (3):291–305. doi: 10.1177/0022343390027003005.

- Gerst, D. 2019. Epistemic border struggles: Exposing, legitimizing, and diversifying border knowledge at a security conference. In Border experiences in Europe, ed. B. Nienaber and C. Wille, 143–66. Baden-Baden, Germany: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft.

- Gross-Wyrtzen, L. 2020. Contained and abandoned in the “humane” border: Black migrants’ immobility and survival in Moroccan urban space. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 38 (5):887–904. doi: 10.1177/0263775820922243.

- Hodder, J. 2017. On absence and abundance: Biography as method in archival research. Area 49 (4):452–59. doi: 10.1111/area.12329.

- hooks, b. 1996. Killing rage: Ending racism. London: Penguin.

- Human Rights Watch. 2019. EU: Address Croatia border pushbacks abuses should rule out Schengen Accession. Accessed February 22, 2022. https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/11/08/eu-address-croatia-border-pushbacks.