Abstract

Historically, urban developers, politicians, and public water utilities have invented Los Angeles as a semitropical oasis in a dry climate. During the California drought of 2011 through 2016, however, the city’s residential gardens became a new frontier of water conservation policy. Water agencies started to subsidize the replacement of lushly irrigated lawns with California Friendly® landscapes, thereby endorsing a technology-centered “infrastructuring” of gardens to increase water conservation. This approach contrasts with California native plant gardening promoted by nature conservationists, which uses vernacular horticultural techniques to restore native plant biodiversity and reduce irrigation. The article shows that each approach has important political implications for urban space and water use, the value accorded to nature and gardening work, and relations between citizens and experts. Analyzing the differences between these approaches, we critically interrogate Los Angeles’s modern infrastructure regime that shapes water conservation policy. Particular attention is paid to how new material objects, knowledges, and practices in gardening recompose relationships between water, plants, technology, humans, and urban space. We argue that the notion of infrastructuring gardens offers a fruitful lens for ascertaining how expert cultures shape urban environmental change and how alternative gardening practices (re)produce urban nature differently.

历史上,城市开发商、政界人士和公共供水设施,将美国洛杉矶市建设成干旱气候下的亚热带绿洲。然而,2011至2016年加利福尼亚旱灾期间,洛杉矶市的住宅花园成为节水政策的新前沿。水务部门开始资助用“加利福尼亚友好”(California Friendly)景观取代茂盛的灌溉草坪,支持以技术为中心的“基础设施”花园,提高节水能力。这种方法与自然保护主义者提倡的加州本土植物园艺形成反差,即,使用本土园艺技术来恢复本地植物多样性并减少灌溉。本文表明,这两种方法对于城市的空间和用水、自然和园艺工作的价值、公民和专家的关系,都具有重要的政治意义。通过分析这两种方法的差异,我们批判性地审视了塑造水资源保护政策的洛杉矶当代基础设施制度。特别关注园艺新材料、新知识和新方法对水、植物、技术、人类和城市空间关系的重组。我们认为,基础设施花园的概念,为确定专家文化如何影响城市的环境变化、替代园艺方法如何(再)创造不同的城市特性,提供了有效的视角。

Históricamente, los promotores urbanos, los políticos y las empresas públicas del recurso hídrico han dibujado a Los Ángeles como un oasis semitropical en un clima seco. Sin embargo, durante la sequía de California de 2011 a 2016 los jardines residenciales de la ciudad se convirtieron en una nueva frontera de la política de conservación del agua. Las entidades encargadas de controlar el uso del agua empezaron a subvencionar la sustitución de prados de riego exuberante por paisajes de California Friendly ®, respaldando de esa manera una “infraestructuración” de los jardines, centrada en tecnología, para incrementar la conservación del agua. Este enfoque contrasta con el de la jardinería con plantas nativas de California promovido por los conservacionistas de la naturaleza, que usa técnicas vernáculas de horticultura para restaurar la biodiversidad de la vegetación autóctona y reducir la irrigación. El artículo muestra que cada enfoque tiene importantes implicaciones políticas para el espacio urbano y el uso del agua, el valor concedido a la naturaleza y al trabajo de jardinería, y las relaciones entre ciudadanos del común y los expertos. Al analizar las diferencias entre estos enfoques, interrogamos de manera crítica el régimen de infraestructura moderna de Los Ángeles que configura la política de conservación del agua. Se presta atención especial al modo como los nuevos objetos materiales, conocimientos y prácticas de jardinería recomponen las relaciones entre el agua, las plantas, la tecnología, los seres humanos y el espacio urbano. Argumentamos que la noción de jardines infraestructurados presenta una lente fructífera para establecer cómo las culturas expertas configuran la transformación ambiental urbana y cómo las prácticas alternativas de jardinería (re)producen la naturaleza urbana de manera diferente.

Palabras clave::

This article studies endeavors of public water utilities and California native plant advocates to relandscape the thirsty residential gardens of Los Angeles for water conservation. Modern lawned gardens in North American cities have been fetishized as symbols of the human domestication of nature and as markers of cultural belonging. This, however, obfuscates the urban political ecologies of lawn gardens in which considerable labor, technology, and resource inputs produce highly uneven socioecological relations (Robbins Citation2007). In arid climates worldwide, the suburban desire for lush gardens has nourished urban sprawl and exacerbated urban water scarcity (Askew and McGuirk Citation2004; Parés, March, and Saurí Citation2013). Cities in the southwestern United States are prime examples (Larson, Hoffman, and Ripplinger Citation2017). Although the expansion of water networks has facilitated the proliferation of thirsty gardens, these gardens have rarely been actively managed as infrastructure components. We argue that relandscaping endeavors for water conservation reveal not only the power relations that shape urban environmental governance through infrastructure, but also the opportunities for alternative forms for aligning infrastructures with urban nature.

The California drought between 2011 and 2016 brought these dynamics to the fore, and the current drought emergency underscores the urgency to change inherited landscaping practices. In Los Angeles, landscape irrigation represents 54 percent of single-family water use (Mini, Hogue, and Pincetl Citation2014). Although water utilities in California largely depend on revenues from water sales, in 2014, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) and the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California (MWD) turned to residential gardens as their new frontier of water conservation. The agencies set up a joint California Friendly® landscaping program that has subsidized the replacement of lawns with drought-tolerant plants from all over the world and has introduced more efficient irrigation systems. Meanwhile, a small but established California native plant restoration movement of conservationists, horticulturists, and landscape designers has promoted California native plant gardens, viewed as skillfully curated and largely self-sustaining ecologies that require minimal irrigation. Both approaches imply interrelated social, technical, and material changes to Los Angeles’s modern gardens, yet these have attracted little attention. Even less attention has been paid to the shifting relationships between technocratic infrastructure management and gardens as complex spaces of everyday human and nonhuman urban life.

In this article we explore and compare the material politics of retrofitting Los Angeles’s residential gardens through California Friendly landscaping and California native plant gardening. This provides a promising case study for examining conflicts over urban environmental management shaped by technology and different forms of expertise (Cousins Citation2017). Although being mindful of the relationships between aesthetics, the transformation of nature, and social power embodied in landscapes (Cosgrove Citation1998), we uncover the politics of relandscaping through the lens of technology. We frame gardens as “technonatures” (White and Wilbert Citation2009) to analyze the sociotechnical entanglements linking residential gardens with water infrastructures. Inspired by Rutherford (Citation2020), we trace how those entanglements become “material politics.” This entails studying how actors reconfigure material objects to achieve political objectives of relandscaping Los Angeles, which rework substantive relationships between water, plants, technology, humans, and urban space.

Drawing from Blok, Nakazora, and Winthereik (Citation2016), we conceptualize garden retrofits as processes of “infrastructuring” gardens to analyze the contested practices and projects of recombining technical and other material artifacts and knowledges in gardening through which actors seek to facilitate particular infrastructure development. Consequently, dynamics in gardening become part of more enduring patterns of organizing environments that can expand over broader spatial and temporal horizons. Reading gardens as sites of infrastructuring can enrich the critical study of technology in urban environmental governance by highlighting how infrastructure is shaped by technological agency in relation to other human and nonhuman agencies. This perspective reveals the power differentials and the instances of alternative politics of urban nature that occur when technocratic environmental management encounters the “ecological pluriverse” (Gandy Citation2022) of contemporary cities where technology, culture, and nonhuman life intersect.

The analysis starts by discussing the historical coevolution of water network expansion and residential gardens in arid southwestern U.S. cities. Then, building on work on technonatures and urban infrastructures, we construct a conceptual framework for understanding the material politics of infrastructuring gardens. We next outline the emergence of Los Angeles as a semitropical garden city and analyze California Friendly landscaping and California native plant gardening. We show that strict public control of water pricing, technoeconomic imperatives of enhancing local water supplies, and an inherited engineering culture in water management favor a technology-centered infrastructuring of gardens through California Friendly landscaping to maximize water conservation. In contrast, California native plant gardening focuses on restoring autochthonous biodiversity that includes native or endemic speciesFootnote1 and foregrounds alternative horticultural techniques. Comparing these landscaping approaches allows us to critically review the politics of water management in Los Angeles. The diverging choices of material objects, knowledges, and gardening practices have implications for urban space and water use, the value accorded to nature and gardening work, and the relationship between water agencies and citizens. The article concludes by highlighting how analyzing practices of infrastructuring gardens can be a useful way of exposing how expert cultures shape urban environmental change and developing alternative politics of urban infrastructure and nature.

For our research, we analyzed planning and policy documents, technical manuals, legislation, and relevant newspaper articles. The data were collected between 2018 and 2019 in fifty-four semistructured qualitative interviews.Footnote2 Inspired by our theoretical framework, the interviews focused on four analytical dimensions: (1) plants, technologies, forms of expertise, and practices involved in water-efficient gardening; (2) the politics of water management in Los Angeles; (3) actors’ ideas of technology and nature; and (4) the organization, knowledge, and practices of the landscaping industry. In an iterative process, these dimensions structured the qualitative content analysis of the empirical material, but they were also refined during the study and specified through subcategories. We constructed the argument around infrastructuring gardens by interrelating these four categories to explain relandscaping endeavors and their political implications in Los Angeles. The analysis was supplemented by field observation of gardening work, visits to nurseries and model gardens, and participation in a California Friendly landscaping workshop. To better understand the history of Los Angeles as a garden city, we studied sources from the Huntington Library on the environmental history of gardening and urban development in Los Angeles.

Thirsty Gardens in Arid U.S. Cities

In the twentieth century, U.S. suburbs saw the widespread proliferation of English-style lawn gardens, epitomizing a modern suburban lifestyle. After World War II, lawn gardens thrived as part of the Fordist “auto-house-electrical appliance complex” (Roobeek Citation1987, 133), with a mix of natural resources, plants, labor, and technology deployed in pursuit of recreation and economic prosperity (Fishman Citation1987). Maintaining neat lawn aesthetics through constant input of fertilizers, pesticides, and machine-aided labor, Robbins (Citation2007) argued, became a moral obligation of U.S. homeowners. Pursuit of this aspiration sustains a multibillion-dollar garden industry that causes substantial ecological and health damage through watershed pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, and exposure to chemicals (Robbins 2007, 66). More recently, the quest for a “‘good’ lawn—green, uniform and neat” (Brooks and Francis Citation2019, 560) has led to artificial lawns being embraced. Although garden supply companies and water utilities promote artificial lawns for water conservation, these lawns engender new conflicts about plastic waste production, biodiversity loss, and urban heat islands. Appearing at first sight to be a banal appendage to the modern home, lawn gardens imply conflictual decisions about the environments we live in—how we design and sustain them, for what purposes, and at what social and environmental costs.

Technology is deeply interwoven with the politics of residential landscaping in at least two ways. First, in nineteenth-century England and more humid regions of the United States, lawn care emerged as a matter of inputting labor and technology for weeding and mowing (Robbins Citation2007, 45–46). Today, industry’s pursuit of profits and an entrenched consumption culture result in households acquiring equipment such as mowers, edging shears, and leaf blowers. Second, in arid and semiarid climates, irrigation has been indispensable for the rise of lawn gardens and their associated cultures of suburban living. The creation of cities in the southwestern United States as green oases relied on garden irrigation enabled by the geographical expansion of water import networks (Reisner Citation1993; Gober and Trapido-Lurie Citation2006). Since the late nineteenth century, significant public infrastructure investments and the rationalization of service provision through territorial monopolies have fueled urbanization. In the early twentieth century, the centralization and frequent municipalization of water networks ensured universal water supply, which became the domain of expert cultures of engineering and applied economics (Melosi Citation2008, 82ff). Simultaneously, dwelling in their networked homes, citizens became passive recipients of water services. Although public investments in infrastructures have declined in U.S. cities since the 1970s, responsibility for ensuring cheap and abundant water supply often still remains in the public sector (Pincetl Citation2010, 46). The revenue-dependent financing models of utilities continue to favor volumetric water sales and a focus on securing reliable supply for growing cities.

Although largely technologically enabled, the water footprint of residential gardens is also embedded in a web of cultural norms. The settler colonial ideology of turning the desert into a flourishing empire formed a critical cultural underpinning of land development in the southwestern United States (Worster Citation1985). Suburbanization processes nourished by this imaginary drove a socially produced water scarcity, exacerbated by the aesthetic norms of lawn cultures and social conventions of comfort (Robbins Citation2007; Larson, Hoffman, and Ripplinger Citation2017). Meanwhile, Mustafa et al. (Citation2010) showed how water-saving landscapes can feature as markers of environmental consciousness and privilege. Watering a garden thus cannot be reduced to simply using a resource. Instead, gardens feature as arenas of social and cultural differentiation, symbolizing distinct lifestyles and value systems (Head and Atchison Citation2009) and reflecting persistent colonial power structures (Ballard and Jones Citation2011).

The diverse histories of infrastructure-fueled urbanization reveal gardens as highly political entanglements where there is convergence of labor relations, cultural meaning, relationships between water agencies and users, and resource and public infrastructure politics. Residential garden retrofits deployed to achieve a particular infrastructure development reconfigure these complex socioechnical and political relations.

The Material Politics of Infrastructuring Urban Gardens

The notion of “technonatures” (White and Wilbert Citation2009) can be used to explain the complex relationships between gardens and technology. It underscores the central role of technology in creating, maintaining, and experiencing natures. White and Wilbert (Citation2009) argued that ideas of technological change are increasingly shaping political interventions that transform environments. Although the technological features of modern suburban gardens have been “buried beneath swathes of lawn” (Davison Citation2009, 174), these features are becoming increasingly visible through practices of local water harvesting or food production. At its heart, the technonatures concept draws attention to locally contingent interactions between actors, technologies, and nature that give rise to distinct environments. Analyzing sociotechnical practices that produce technonatures can thus reveal the distributed power relations underlying (urban) environments (see also Giglioli and Swyngedouw Citation2008; Sultana Citation2013). Accordingly, tracing the practices of retrofitting gardens for water conservation is a promising approach for exploring the emerging relationships between gardens and water infrastructures.

Urban water infrastructures are complex systems, however, that mediate flows of resources and power in producing urban technonatures (Monstadt Citation2009). Infrastructure scholars have conceptualized urban infrastructures as sociotechnical systems within which technical artifacts are tightly interlinked with institutions, governance structures, actors, practices, knowledges, and flows of materials and money (Coutard and Rutherford Citation2016). Thus, technical artifacts’ particular qualities and arrangements shape infrastructure development and the social interests embedded in infrastructures. Reconfiguring these artifacts provokes distinct “material politics” (Rutherford Citation2020) of sociotechnical change that exert power over interrelated infrastructure and urban development. Thereby, infrastructural objects constitute “the disparate settings and arenas in and through which policy discourse and goals are actively translated into actual concrete actions and political interventions” (Rutherford 2020, 24). In a given urban infrastructure context, infrastructural practices follow systemic rationales and seek to align heterogeneous infrastructure elements accordingly. Consequently, infrastructure constitutes a powerful ordering mechanism (Star and Ruhleder Citation1996). Although infrastructure rationales are embedded in material orders, institutions, standards, and hegemonic conventions of practice, infrastructures also “come into being, persist, and fail in relation to the practices of the diverse communities that accrete around them” (Carse Citation2012, 544).

Drawing on the debates just presented, we can explore and explain how emerging relationships between gardens and water infrastructures are negotiated through material practices and are shaped by infrastructure as an ordering mechanism. Blok, Nakazora, and Winthereik’s (Citation2016) notion of “infrastructuring” brings into focus the “contested practices and projects whereby human groups seek to organize their environment via technical, material, and knowledge interventions” (5). This builds on the idea that at a particular moment, artifacts become infrastructure within a broader set of relationships (Star and Ruhleder Citation1996). Accordingly, we can describe landscape retrofits for water conservation as a process of infrastructuring gardens whereby gardens are rendered part of relatively enduring patterns of organizing environments through infrastructure. We argue that infrastructuring gardens describes the contested projects and practices of recombining technical and other material artifacts and knowledges in gardening, through which actors seek to facilitate particular infrastructure development. When gardens are infrastructured, specific plants or technologies are strategically recomposed according to a given infrastructure rationale or to change this rationale. Practices of infrastructuring gardens thereby engender distinct material politics that modify politically significant relationships between water, plants, technology, humans, and urban space.

Practices of infrastructuring gardens and their political effects depend on material objects and distinct forms of knowledge of how material objects work and interrelate. Infrastructuring practices reconfigure and are shaped by the material composition of gardens. For urban water infrastructure to function smoothly, system builders need to connect many technical objects whose physical properties codetermine how this can be achieved (Tiwale Citation2019). Infrastructuring gardens for water conservation entails changing irrigation systems, plants, or ground cover, thereby sparking novel sociotechnical relations. For instance, water utilities’ decisions about investments and infrastructure planning can be influenced by the water and maintenance requirements of plants in gardens, and, conversely, these decisions can influence which plants are grown in gardens. Plants’ requirements, however, mean that these issues cannot be separated from aspects such as biodiversity or aesthetics. Critical scholars of urban biodiversity have presented accounts of ecological practices that became growing scientific and political concerns and resulted in alternative politics of urban nature (Lachmund Citation2013; Gandy Citation2022). Similarly, through garden retrofits, plant-associated technonatural relations become new concerns of infrastructure management, which could lead to new ecological practices being adopted, thereby advancing infrastructure management. We argue that infrastructure development therefore largely depends on which biotic or abiotic features of urban gardens actors select and foreground through practices of infrastructuring.

The different forms of knowledge involved in garden retrofits shape how actors select and foreground biotic and abiotic features of urban gardens. Practices of infrastructuring gardens draw together hitherto largely separate knowledge cultures of governing urban nature. Water management is dominated by engineering knowledge that focuses on abiotic aspects of the city while having less experience with managing plant ecosystems (Finewood, Matsler, and Zivkovich Citation2019). Water managers are more likely to deploy technical devices to create controllable technonatures that align with existing cost-efficiency and reliability principles. By contrast, landscape design and horticultural knowledge concentrate on the biological processes of plants and the interrelationships between biotic and abiotic elements of landscape ecosystems that serve as templates for practice (McHarg Citation1969). When gardens are rendered functional elements of water infrastructures, infrastructure depends on homeowners’ gardening techniques and skills, landscaping workers, or specialized horticulturists. “Saturated with technologies and techniques” (Davison Citation2009, 181), residential gardens thus provide opportunities to develop new ideas of water infrastructures as systems that rely on different forms of expertise. Which ideas of infrastructure and related forms of governing urban nature ultimately prevail largely depends on how actors portray distinct practices and knowledges as expert ways of doing landscape water conservation.

Altogether, the notion of infrastructuring gardens provides a fruitful way to study the diverse agencies at work and the possibilities of future politics of urban nature at stake when residential gardens are transformed from a given backdrop to public urban life to a systemic component of urban infrastructure. Gardens thereby form sites where existing urban infrastructure regimes might become reconstituted and where these regimes can be challenged and reworked. This conceptual lens expands scholarship on technonatures by discussing infrastructures as both historically layered and continuously contested systems of (re)ordering urban gardens. At the same time, the technonatures concept emphasizes technology as a crucial element of infrastructuring gardens that is itself contested. Consequently, technology forms a particular mode of experiencing and producing gardens through technical interventions dominated by science and engineering rationality. Infrastructuring gardens also involves everyday urban practices that are not technological and that harbor alternative rationales of organizing environments. This perspective allows understanding conflicts over urban environmental management through the instability of different cultures of knowing and managing nature that clash in material disputes over infrastructure design. Drawing on Gandy (Citation2022), infrastructured gardens can further be read as distinctly urban ecological constellations that reflect broader tensions between cities as “generators of new cultures of urban nature” (246) and drivers of global environmental change. Efforts to reconcile the technological, biological, and cultural dynamics in urban gardens to pursue more livable urban futures might point to alternative modernities and spark new ideas for governing urbanization in the Anthropocene.

In what follows, to unpack the material politics of outdoor water conservation in Los Angeles, we describe garden retrofits in terms of outdoor water conservation policies versus the restoration of autochthonous biodiversity. To do so, we scrutinize the distinct material orders, forms of expertise, and practices inherent to these diverging landscaping approaches; explore their particular political configurations of governing urban nature and space; and discuss what their differences reveal about the politics ingrained in sociotechnical arrangements that shape outdoor water conservation in Los Angeles. The analysis is prefaced by a brief discussion of Los Angeles’s combined history of modern water infrastructure and garden city development.

Semitropical Los Angeles Facing the 2011 through 2016 Drought

It’s harder to have a garden than to have a yard. A lawn is very, very easy. As long as it’s greenish and flat and it’s mowed and it’s green, you’ve won. You’ve won. You know, you did it. You succeed. (Interview, expert in water-efficient landscaping, 21 February 2018)

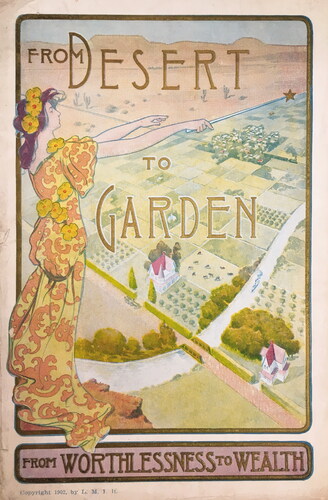

Spanish missionaries founded Los Angeles in the Los Angeles Basin, where a Mediterranean climate and fresh water from the Los Angeles River were conducive for settlement and agriculture. In the twentieth century, expanding water networks turned the relationship between Los Angeles and its water resources inside out—through water imports, water was sourced from distant water catchment basins rather than locally. The construction of the 233-mile Los Angeles Aqueduct in 1913 famously unlocked the “invention” of modern Los Angeles as a semitropical garden city (Sackman Citation2005). Lawned gardens proliferated in the affluent foothills, and autochthonous plants were replaced by “garden tolerant” (Green Citation2017) species from Europe or tropical colonies that thrived in irrigated gardens. Simultaneously, land developers disseminated a powerful “from desert to garden” (Imperial Land Company Citation1902) vision of Southern California that not only boosted urban growth but also established an imaginary rift between a city oasis and its allegedly hostile and worthless “desert” environment (see ). Lush green flourished predominantly on private property after real estate lobbyists had successfully thwarted the creation of a regional public park system in the 1930s (Hise and Deverell Citation2000).

Figure 1 From Desert to Garden book cover (Imperial Land Company Citation1902; The Huntington Library, San Marino, California).

After World War II, water, tools, irrigation systems, and cheap immigrant labor rendered semitropical gardens the norm for middle- and upper-class neighborhoods. The MWD provided additional imported water from the Colorado River and California’s State Water Project, which kept Los Angeles booming and blooming. Since its foundation in 1928, the MWD has been controlled by its member agencies (i.e., Southern California’s public and private water utilities) but has operated as a revenue-driven business. Infrastructure investments in a vast system of dams and aqueducts have historically been made to expand the water supply. Similarly, the public LADWP incorporated an expansionist approach to water provision to keep water prices low and revenues flourishing. The strict control of water pricing through the votes of City Council members on unpopular water rate increases and a rigid regime of local taxes and fees in CaliforniaFootnote3 restrict LADWP’s investment decisions. Throughout the twentieth century, technomanagerial efficiency propelled regional urban growth in a concerted effort of network expansion and urban development (MacKillop and Boudreau Citation2008) and stimulated lock-ins into high consumption patterns. Only since the 1990s has LADWP more strongly embraced indoor water conservation (e.g., through promoting efficient showerheads) and a (somewhat tentative) conservation-oriented rate structure, which has left high-consuming customers with a slightly higher per-unit price. Conservation strategies have been deployed to ensure unfettered growth in the face of finite resources and increasingly unreliable water imports (Hughes, Pincetl, and Boone Citation2013, 54–55).

Today, Los Angeles’s semitropical gardens are sustained by infrastructure and specific technonatural relations. Near-ubiquitous irrigation systems constantly water a cosmopolitan variety of plants. Typically, ground sprinklers are connected to underground piping, a pump, a pressure regulator, and a controller. Lawns, palm trees, and the city’s floral emblem, the South African Bird of Paradise (Strelitzia reginae), require continuous irrigation throughout the year, especially during the long dry period from April until October. Repetitive irrigation cycles—typically watering “10 min, three times a week” (Interview, California native plant horticulturist, 11 April 2019)—flatten seasonal variation in rainfall and normalize high water consumption. What would otherwise require expert knowledge about sprinkler type, soil characteristics, and plant species is left to this standardized popular program formula. Meanwhile, the visual appearance of lawns functions as a proxy for plant health, and gardeners tend to water more to ensure lush green and prevent client complaints. Continuous irrigation and a balmy climate turn semitropical gardens into fast-paced technonatures, with landscape irrigation on average accounting for more than half of single-family water use (Mini, Hogue, and Pincetl Citation2014).

Specific landscaping practices have been developed to curb rapid plant growth. Typically, gardening work in Los Angeles is contracted out to a low-wage, immigrant workforce. Until the 1970s, Japanese gardeners used hand clippers as iconic symbols of their skilled labor, but nowadays the mostly Mexican gardeners rely on power tools (Ramirez and Hondagneu-Sotelo Citation2009, 74). These air-polluting devices standardize gardening work, thereby marginalizing horticulturally skilled gardening techniques. In weekly efforts, “mow-blow-and-go guys” (Interview, expert in water-efficient landscaping, 13 March 2018) mow grass, blow dead plant material off the garden, apply chemicals, prune plants, and remove vast amounts of green waste to keep semitropical gardens in a static form, satisfying modernist aesthetic desires for domesticated nature. At the same time, the livelihoods of undocumented workers depend on frequent labor input, with one job in a suburban residential garden typically taking “30 to 60 min” (Ramirez and Hondagneu-Sotelo Citation2009, 74). An abundance of garden products fuels this thirsty “treadmill” (Interview, municipal sustainable landscape manager, 10 April 2019) ecology of semitropical Los Angeles.

Since the 1980s, xeriscaping, a form of adaptive landscaping in dry climates that strongly promotes efficient irrigation technology and uses drought-tolerant plants, has been adopted by water agencies in the southwestern United States (Sovocool, Morgan, and Bennett Citation2006). Finding that 66 percent of water savings in xeriscapes are realized through irrigation efficiency, Hilaire et al. (Citation2008) underlined that the “emphasis must be placed on irrigation systems” (2086). Not until California’s drought between 2011 and 2016, though, was massive public attention directed at Los Angeles’s semitropical gardens, which were portrayed as the new frontier of water conservation. In May 2015, Governor Jerry Brown (Citation2015) mandated a statewide reduction of urban water use by 25 percent compared to 2013 levels. The order imposed large-scale turf-removal programs and reformed California’s Model Water Landscaping Ordinance to combine water-efficient landscaping with stormwater improvements in landscapes. These endeavors enrolled private gardens in technocratic efforts to maximize water conservation while increasing local water supplies through stormwater reuse (Cousins Citation2017). The Executive Order Making Water Conservation a California Way of Life, signed in 2016, established a mechanism to determine and monitor local water conservation targets and resulted in new legislation promoting the reduction of outdoor water use (California Department of Water Resources Citation2018). In this context, LADWP and the MWD initiated a joint California Friendly landscaping program to tap into the enormous conservation potential of private gardens. This trademarked and specially developed drought-tolerant landscaping scheme was tied to a rebate program for turf removal: Through a $350 million investment from the MWD’s emergency fundFootnote4 and additional LADWP incentives, customers could receive a $3.75 subsidy per square foot of replaced lawn, which sparked “astronomical participation” (Interview, LADWP water conservation managers, 16 March 2018).

The core elements of California Friendly landscapes are a global plant palette of drought-tolerant, low-maintenance species and drip irrigation systems—perforated underground plastic tubes that apply irrigation water directly to the roots (Kent Citation2017). Mulch, rocks, or gravel are required as permeable ground cover. In particular, improvements in irrigation systems mobilize a technology-centered conservation approach that sustains LADWP’s strategy to ensure a cost-efficient and reliable water supply for a growing city under increasing uncertainty.

The attractive rebates led to the emergence of specialized turf-removal businesses. One company, called Turf Terminators, became notorious for installing what was perceived as bare landscapes predominantly of gravel and rocks or artificial grass, with minimal plant cover (see ). Offering to remove turf for customers for precisely the rebate amount, the business received “roughly 12%” (Scott Citation2016) of the MWD’s total rebate fund. Turf Terminators were heavily criticized by Los Angeles’s environmental community and the broader public for creating landscapes that increase plastic waste (for artificial turf), reduce biodiversity, and exacerbate urban heat island effects. The company closed down in 2015, and since 2016 water agencies have stopped subsidizing artificial turf.

The MWD’s $350 million fund was exhausted within a year, and by 2015, Los Angeles residents were receiving only $1.75 from LADWP per square foot of replaced lawn (Luskin Center for Innovation Citation2017, 1). The MWD (Citation2019, 1) resumed the program in April 2018 with a drastically reduced annual budget of $17 million. As participation after the drought remained low, the subsidy was raised again in February 2019 from $1 to $2 per square foot, and plant coverage requirements were relaxed (MWD 2019, 2). Generally, however, the MWD strategically refrained from heavily funded turf-removal subsidies. Having only replaced approximately 3 percent of the lawns in the district’s service area by investing $350 million (Interview, MWD water conservation manager, 26 February 2018), water managers opted instead to promote a paradigm shift in gardening through marketing and education.

A second alternative response to the drought emerged through a niche movement of California native plant conservationists. Since the 1980s, native plant gardening for water conservation has been advocated across the southwestern United States (Mee et al. Citation2003). Rather than being an overarching paradigm, though, native plant advocates see water conservation as a consequence of restoring autochthonous biodiversity. Schmidt’s (Citation1980, 1) early “case for native plants” foregrounded habitat preservation as the prime objective of California conservationists. Today, a network of growers and experts—including specialized landscape architects, contractors, and nurseries—promote a holistic idea of landscaping as facilitating and reestablishing native plant ecologies as “living systems” (Interview, California native plant landscape architect, 14 March 2019) that have been “lost” to urbanization. The emphasis is on the horticultural value of autochthonous plants and their symbiotic relationship with the local fauna and climate and their role as aesthetic markers of a distinct Californian cultural history (Bornstein, Fross, and O’Brien Citation2005; see ). The conservationists emphasize skilled techniques as a form of interaction with landscapes: Detailed plant knowledge, careful plant selection, and vernacular planting and cultivation practices are considered vital to create largely self-sustaining native plant ecologies that minimize technology and resource input.

The Material Politics of Reworking Residential Gardens in Los Angeles

Drought-tolerant landscaping means different things to different communities and is shaped by environmental values. Environmental action might be based on diverging worldviews such as modernist approaches of sustainability or conservationist thinking to restore nature inspired by ideas of wilderness (Davison Citation2009). Although water conservation managers and California native plant advocates in Los Angeles both problematize resource-intensive semitropical gardens, they propose competing landscape ecologies to reinvent this modern urban nature. In this section, we carve out the particular technonatural characteristics and unpack the material politics of the California Friendly landscaping and California native plant gardening approaches by focusing on three themes (see for an overview). We first discuss contested views of the interplay between technologies, plants, and material objects in garden retrofits. Second, we analyze the differing landscaping practices and related forms of expertise and labor. Third, we critically reflect on the sociotechnical context of water conservation policy in Los Angeles and relations between LADWP and citizens as inferred from the city’s gardens.

Table 1. Comparing technonatural characteristics and politics of California Friendly® landscaping and California native plant gardening

Technologies, Plants, and Material Objects

Aside from behavioral change, water agencies’ conservation policies have often been promoted as a matter of technological improvement. Refining irrigation technology is central to cutting water use through California Friendly landscaping. Drip irrigation reduces the amount of water applied to a landscape, and “smart” weather-based irrigation controllers promise to correct the inefficiencies of a “set it and forget it” (Interview, California native plant landscape professional, 13 March 2019) logic dominating garden irrigation. Algorithms are envisioned to automate the background of irrigation, and control apps will enable complex ecosystems to be managed conveniently via a smartphone (Interview, manager in leading lawn and garden supply business, 2 March 2019).

By contrast, California native plant conservationists frame landscape water needs primarily as ecosystem design. Native plants are cultivated as slow-growing but dynamic elements of urban ecosystems adapted to local soil and climate conditions, thereby minimizing water needs and human and technological input (Interview, California native plant horticulturist, 14 March 2019). The plants themselves are at the forefront and center of any intervention. They are mobilized as water conservation tools by selecting locally adapted species that require little or no extra water, designing landscapes that divert rainwater to plants, and facilitating deep root establishment during the wetter winter months (Interview, consultant in water-efficient landscaping, 13 March 2019). Summer dormancy—when the metabolic activity of native plants is reduced to a minimum—challenges the idea that year-round irrigation is a prerequisite for landscaping in Los Angeles. In general, proponents of native plants seek to create interconnected habitat “corridors” (Interview, California native plant horticulturist, 11 April 2019) of autochthonous biodiversity that also serve as a carbon sink and can moderate heat island effects while keeping dynamic water needs low.

Also, a global plant palette for California Friendly landscapes has been carefully assembled, including many species from South Africa, Australia, the Canary Islands, and California native plants (Kent Citation2017). To ensure effective long-term water conservation, the plants selected have low water needs, require little maintenance, are resilient to external disturbances (including harmful gardening practices), and are commercially available. Their use of specific materials also distinguishes California Friendly landscapes. The rebate requirements for plant coverage have recently been loosened—rocks and gravel thus remain important low-maintenance ground covers, and organic mulch is required in a three-inch-deep ring around all plants (MWD Citation2019, 2). Similarly, California’s Model Water Efficient Landscape Ordinance, which sets a maximum for outdoor water use for new development and substantial redevelopment, excludes unplanted backyards from its water budget rating. A sustainability manager of a prominent housing developer explained that developers frequently take advantage of this loophole to provide customers with more choices if they prefer hardscapes, such as a patio or a swimming pool in their backyard (Interview, sustainability manager of a housing development business, 15 March 2019). By so doing, regulators prioritized effective water conservation above increasing the use of adaptive plant ecosystems.

The design choices made for California Friendly landscapes and California native plant gardens reveal divergent ideas on the use of urban water and space, as well as different epistemologies of nature and technology. California Friendly landscapes are devised as scalable technonatures to ensure effective water conservation. Planting drought-resistant plants undeniably introduces ideas of water sufficiency by reducing the water footprint through gardening practices (see Princen Citation2003). A focus on irrigation efficiency, however, limits further exploration of plant-driven water sufficiency. At the heart of California Friendly landscaping is the transformation of gardens to maximize water conservation at minimum cost to ensure that a growing city will be reliably supplied with water in a future of reduced water imports (see ). By assembling robust, low-water plants and enhanced irrigation technology, gardens are infrastructured to contribute to the durability of an inherited system under pressure and to “place the future [of water scarcity] further away” (T. Mitchell Citation2020). Via such infrastructuring, water agencies redefine the use of water and private urban space following abstract ideas of water conservation, and this is hardly publicly debated as a political question. The long-term social and environmental costs of highly engineered outdoor water conservation, however, could perpetuate biologically less prolific urban landscapes and smart irrigation technologies that rely on pumps, sensors, servers, and so on, building increasing energy demand into landscapes.

Coupling water conservation with creating autochthonous biodiversity while reducing technology input, California native plant gardening can leverage political debates about the broader (nonmonetized) social and ecological values of residential gardens beyond water conservation. In particular, the local character of landscape water conservation—as opposed to importing water, which has externalized environmental costs—provides an opportunity for a progressive rethinking of urban landscapes. Contested practices of infrastructuring gardens reveal political relations between the use of urban space and infrastructural relations that mobilize spaces further away to sustain urban life. California native plant gardening foregrounds plants as coagents in governing water and urban space. The low water requirements of autochthonous biodiversity challenge the inevitability of deploying irrigation technology that originated as an agricultural innovation to improve crop productivity. The promotion of urban native plant biodiversity can thus not only enrich public discourse about urban landscapes and outdoor water use. It can also rework the city–nature dualism inherent in conservation thinking. As an alternative way of infrastructuring gardens, California native plant landscaping allows plants to be thought of as active elements of infrastructure provision. Urban water management increasingly becomes a question of dealing with urban biomass, which provides an opportunity to recast entrenched knowledge hierarchies and to critically rethink the wider urban environmental politics of water conservation policies (see ).

Practices, Expertise, and Labor

Drought-tolerant landscapes involve distinct gardening practices and forms of expertise. Watering California Friendly landscapes mostly revolves around enhancing irrigation technology. Nonetheless, landscaping experts agree that advanced irrigation faces many challenges in practice. Broken pipes are frequently unnoticed, making drip irrigation prone to failure, increasing material waste. Furthermore, by assessing plant health from the visual appearance of plants and incorrectly calibrating smart irrigation systems, both homeowners and commissioned landscapers continuously disrupt the smooth functioning of irrigation (Interview, expert in water-efficient landscaping, 21 February 2018). The actual water use of these systems and their dynamic relationship with plant needs is frequently misunderstood, and “overwatering” (Interview, consultant in water-efficient landscaping, 13 March 2019) remains a prime cause of plant (and water) loss. Although smart irrigation algorithms do away with uncertainty about how to water, they can also prevent a more profound practical engagement with landscapes.

Proponents of California native plants place techniques—skilled gardening practices derived from the scientific and practical exploration of vernacular ecosystems—center stage in landscaping. Correct watering is considered a matter of closely observing plants and soils as well as of laboriously “growing” living ecologies instead of quickly “installing” a static landscape (Interview, expert in water-efficient landscaping, 21 February 2018). The growing entails propagating native California species in pots and ensuring that plants establish deep root systems by planting small plants in the fall. Native plant horticulturists deem irrigation technology a “last resort” (Interview, consultant in water-efficient landscaping, 13 March 2019) rather than an inherent element of a garden landscape. They criticize that modern societies grant technology an elevated role in landscape care:

The whole idea of landscaping, it’s also diminished in value because when it really comes down to it, it’s not about tech[nology], it’s about technique. (Interview, consultant in water-efficient landscaping, 13 March 2019)

Water conservation is thus viewed as a consequence of meticulous plant care that does not lend itself to the economy of scale principles. Once established, California native plant landscapes demand infrequent but horticulturally skilled “long-term inputs” (Interview, California native plant horticulturist, 11 April 2019) following the fundamental principles of seasonality, plant life cycles (root growth, strategic pruning), and local material cycles (dead organic material is left in place).

Highly engineered and favoring sturdy plants, California Friendly landscapes are designed for robustness and low maintenance. The approach is applied in an environment in which landscaping maintenance is a highly standardized and machine-aided practice, and specialized horticultural expertise is frequently absent or not used. Hence, irrigation failure, inadequate pruning, and acidic urban soils are still expected to result in moribund California Friendly landscape planting (Interview, expert in water-efficient landscaping, 13 March 2018). More important, however, experts predict landscaping workers will continue their usual ingrained maintenance practices to secure a constant income (Interview, California native plant horticulturist, 14 March 2019). This social context of landscaping work puts into perspective visions of rationalizing outdoor water conservation through mere material changes:

If we devaluate our landscapes from the get‐go, we’re also devaluating the labor force and therefore we’re setting unrealistic expectations as to how we’re hiring to maintain […] the most complex ecological systems that we’ve devised. (Interview, municipal sustainable landscape manager, 10 April 2019)

With landscapes and their upkeep work remaining culturally undervalued and given the high competition among landscapers, wages for gardeners are low. The average monthly rates for garden maintenance in a single-family home in Los Angeles dropped from between $75 and $100 in the 1980s to as low as $50 by the end of the 1990s. More recently, informal gardeners in Los Angeles earned between $50 and $75 per day (Huerta and Morales Citation2014, 69). Self-employed landscapers and small businesses, predominantly run by Mexican immigrants and often undeclared labor, have tailored their business models to the frequent maintenance requirements of semitropical gardens. Successful landscape “worker-entrepreneurs” (Ramirez and Hondagneu-Sotelo Citation2009, 74) are deemed to manage a maximum number of gardens with minimal time expenditure per garden (see also Hondagneu-Sotelo Citation2014).

After significant budget cuts for water conservation in 2015, water agencies embraced landscaping education—a “recognized challenge” (Interview, LADWP water conservation managers, 16 March 2018). Free California Friendly gardening workshops for homeowners addressed irrigation control, California Friendly plants, soil characteristics, climate zones, and garden design templates to standardize turf-removal projects and simplify landscape maintenance. The California Friendly landscaping manual starts with a detailed section on irrigation control before introducing the watering, fertilizing, and pruning needs of California Friendly plants (Kent Citation2017). Although the MWD is collaborating with the California Landscape Contractors Associations on a certification program for professional landscapers, the undocumented status of many landscaping workers limits the outreach of such programs. An expert horticulturalist who trains homeowners and professionals criticized water-agency-sponsored classes for being “irrigation-centric” (Interview, consultant in water-efficient landscaping, 13 March 2019).

Although there are some overlaps between California Friendly landscaping and California native plant gardening, their qualitative differences raise important questions about the value assigned to landscape ecologies and landscaping work. Designed for cost-efficient and reliable water conservation according to institutionalized engineering principles of water management, California Friendly landscapes contrive labor worlds of reduced maintenance work. Water agencies’ budget cuts for water conservation, together with cost-efficiency standards and low water prices, leave little room for well-resourced landscaping industry transformation programs. As carefully selected new infrastructure components, plants enable what Ernwein (Citation2021, 3) called “eco-managerialist” forms of urban environmental management that perpetuate uneven labor relations and an existing skill set of landscaping work. Hence, to facilitate the desired infrastructure development, practices of infrastructuring gardens can, at times, incorporate existing injustices into an emerging infrastructure arrangement. Adding to D. Mitchell’s (Citation1996) idea of “dead labor” materialized in landscapes, the nonhuman work performed by California Friendly plants constitutes a—socially uneven—backdrop of urban water management. Additionally, a huge power differential between immigrant landscaping workers and a multibillion-dollar garden supply industry that benefits from semitropical gardens and high technology input into gardens—two sides of the same coin—obstructs the reinvention of this industry. Although urban green is increasingly portrayed in policy discourses as something universally “good” (Angelo Citation2020), its sustaining technonatural relations frequently remain pervaded by power imbalances. Tracing practices of infrastructuring gardens can reveal how the interplay of technical, human, and nonhuman agencies in local disputes over environmental management is bound up with labor relations or global discourses of urban sustainability.

California native plant gardens are still curated mostly by enthusiastic conservationists or designed as high-end gardens professionally horticulturally maintained for wealthy homeowners. Scaling up these ecologies requires significant shifts in the interplay of technology, plants, knowledge, and labor, and thus a radical transformation of the incumbent political ecology of landscaping. The idea of revaluing skilled horticultural practices through more widespread practical engagement with native plants as infrastructure components implies a powerful critique of low-wage landscaping work and technology-centered garden retrofits. Furthermore, if California native plants are to be grown, the nursery industry needs to shift toward local geographies and seasonal business models of raising and supplying autochthonous plants in big-box stores. Such a move challenges the industry of raising and selling perennial plants that coevolved with irrigation technology. Not least, infrastructuring gardens using native plants blurs the boundaries between public infrastructure and economic development policy. To promote a local Green New Deal, Los Angeles has launched the LA Cleantech Incubator, providing workspaces and funding for technology companies in clean energy. A native plant horticulturist, however, noted that a “landscape incubator” lies beyond the realm of contemporary sustainability policy (Interview, consultant in water-efficient landscaping, 13 March 2019). Rethinking water conservation through California native plants reveals this absence of a public policy that promotes sufficiency-oriented economic and infrastructure development in which plants—rather than technofixes—are center stage.

Gardens, Water Regimes, and Citizens

Garden retrofits in Los Angeles need to be viewed against the backdrop of the city’s current regime of water provision, which becomes renegotiated through practices of infrastructuring gardens.

LADWP and the MWD generate revenue from water sales. Hence, water conservation remains contested within both agencies, where environmentalists argue with proponents of business: “it’s walking a fine line […], the more conservation we do, the less water we sell” (Interview, MWD water conservation manager, 26 February 2018). Coupled with the high infrastructure fixed costs and traditionally low and strictly controlled water rates in Los Angeles, revenues that depend on volumetric water sales structurally disincentivize water conservation (Interview, Los Angeles water policy expert, 2 March 2018). In this context, the curtailing of turf-removal funds after the MDW’s $350 million drought emergency investment signals a return to a less radical water conservation agenda. A technoeconomic rationale of offsetting increasingly costly and energy-intensive water imports from the Colorado River and the California State Water Project is what drives water conservation strategies in Los Angeles. Landscape water conservation can reduce the city’s carbon footprint (Cousins and Newell Citation2015). Moreover, turf removal is considered one of the cheapest new water sources for Southern California’s growing cities compared to other efficiency technologies and new supplies from wastewater recycling or desalination. Cooley and Phurisambam (Citation2016, 3) estimated that conserving one acre-foot of water annually through creating cheap water conservation landscapes can save up to $4,500 because lower landscape maintenance costs outweigh investment costs. Investing in high-end conservation landscapes would cost $1,400 per acre-foot of water conserved annually.

Despite the excellent potential for water conservation, the mobilization of private gardens for water conservation presents a complex challenge for water agencies. An interviewed horticulturist noted that unlike roads, electricity lines, or water pipes, residential landscaping has never “risen to a level of [public] health, safety, and welfare” (Interview, consultant in water-efficient landscaping, 13 March 2019). In fact, modern urban infrastructures have created an apparent rift between public service providers and passive consumers. Furthermore, Los Angeles’s water agencies are adept in the financing, planning, and operating large technical infrastructures, whereas profound ecological and horticultural knowledge has historically been beyond their realm of expertise. Operating on unfamiliar terrain and with strict public control of water rates, LADWP engineers thus deploy irrigation systems to control thirsty plant ecologies and unsustainable watering practices. Technology companies envision automated irrigation as part of a smart home’s “distributed infrastructure” that promises cost-efficient water conservation by allowing water utilities “to prescribe better behavior” based on monitored user data (Interview, manager in irrigation technology business, 10 July 2019).

Smart irrigation undeniably increases water conservation: The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (Citation2017) estimated that replacing clock timers with smart irrigation controllers results in annual savings of 7,600 gallons of water for an average home. Infrastructuring gardens via such devices drives up electricity consumption, tying gardens closer to energy systems, data centers, and greenhouse gas emissions. Although promoting ideas of creating harmonious urban natures in a climate-changing world, such infrastructured gardens bring about new collectives that accelerate the extractive “logics of circuits, chips, and capital” (Gabrys Citation2022, 2). A spokesperson for a smart irrigation business explained that as a “consumer-driven” development, automating irrigation aims “to put the homeowner back into the driver seat” (Interview, manager in irrigation technology business, 10 July 2019) by granting homeowners more control over irrigation and their water bills. Horticulturalists are skeptical about such visions and underline the risk that automation further distances homeowners from a practical engagement with the dynamic ecosystems in their gardens (Interview, municipal sustainable landscape manager, 10 April 2019).

In general, water conservation policies in Los Angeles have traditionally preferred user education—frequently about individual cost savings—and economic incentives for technical retrofitting over conservation-oriented water rates. Acting as “ratepayer advocate,” Los Angeles’s city controller Ron Galperin closely oversees LADWP’s spending in the interest of cheap, abundant, and safe water. Galperin (Citation2015, 2) criticized the cost efficiency of turf-removal rebates between 2014 and 2015; replacing the existing 2.5 million acres of California lawns with a rebate of $3 per square foot would amount to a stunning cost of $403 billion (Galperin 2015, 4). Instead, he suggested encouraging voluntary conservation through subsidizing smart water meters and rewarding individual water savers. Water supply reliability, he argued, should primarily be ensured through investments in wastewater recycling. Expanding supply, instead of investing in conservation, increases the asset value of water utilities (Bell Citation2015, 19). Meanwhile, to foster a culture of individual action, water agencies give out free rain barrels as symbols of water use efficiency: “landscaping is the water efficiency you can see … . It’s like having a Prius in your driveway” (Interview, MWD water conservation manager, 26 February 2018). In turn, excessive garden watering, notoriously in upmarket West Los Angeles neighborhoods, is increasingly being publicly denounced.

Infrastructuring gardens through California Friendly landscapes reconstitutes relationships between water agencies and users. Turf-removal programs reeducate homeowners as “California Friendly” subjects who visibly perform environmental responsibility while realizing individual cost savings. This, however, is socially uneven: Whereas all rate payers fund turf-removal subsidies, the beneficiaries tend to be middle- and high-income homeowners with gardens (Pincetl et al. Citation2017). At the same time, endeavors to fix a culture of abundant outdoor water consumption through California Friendly landscaping do not impinge on politically delicate debates about more progressive water pricing. Users continue to consume an abstract resource and to strictly oversee water rates and their water bills, even as advanced irrigation controls watering inefficiencies. This illustrates how plants and, in particular, technological fixes in California Friendly landscapes such as “smart” irrigation stabilize existing political orders of water governance. In contrast, California native plant gardening reimagines homeowners as civic experts who contribute to a larger public good through informed gardening choices and practices. Being a good homeowner means doing more than conserving water, but curating gardens through skilled practice. Instead of granting agency to automated irrigation technology, a focus on practice lifts gardens as dynamic ecologies into the foreground of everyday urban life and water governance. The infrastructured garden can become an important site where identity is tied to more ecological practices and where novel technonatural imaginaries of the city are created that recast inherited boundaries between public infrastructure provision and the private realm of the city.

Conclusion

Although historically relegated to the margins of public urban life, residential gardens form complex technonatures with profound social and environmental implications for urban development. Infrastructural practices of retrofitting gardens to conserve water render these relationships visible and raise critical questions about the dominant technologically mediated management of urban nature. Furthermore, infrastructural disputes over relandscaping illustrate a crucial dynamic of governing urban nature in the Anthropocene: Systemic endeavors to make the urban fabric at large an infrastructure for climate resilience or resource efficiency goals increasingly clash with alternative approaches to urban nature such as biodiversity restoration or urban rewilding.

This article has explored the material politics of remaking the semitropical residential gardens in Los Angeles through California Friendly landscaping and California native plant gardening. Developed for a subsidized turf-removal program from Los Angeles’s water agencies, California Friendly landscaping translates a rationale of maximizing water conservation into gardens. Meanwhile, California native plant gardening that is advocated by conservationists couples water sufficiency with enhancing autochthonous biodiversity. This approach also promotes skilled horticultural techniques, challenging an inequitable landscaping industry in which the high profits of equipment suppliers contrast with underpaid labor. California Friendly landscaping aims to control watering practices by improving irrigation, which has normalized technology-centered environmental management that has culturally undervalued biology and landscaping work. Water agencies further encourage voluntary garden retrofits by emphasizing individual monetary savings. These retrofits, however, result in money from all ratepayers being redistributed to (relatively well-off) garden owners and stymie debates about more progressive water rates that are more socially just and could encourage alternative gardening techniques. Policymakers need to address such injustices caused by public infrastructure investments, but this raises issues of institutional and governance reform to change the constraints and incentives under which public water managers operate—their revenue largely depends on selling large volumes of cheap water.

Our article illustrates how the politics of Los Angeles’s inherited water infrastructure regime profoundly shape garden retrofits. Confronted with the complexity of urban landscapes, this regime also becomes renegotiated in residential gardens. We have developed the notion of infrastructuring gardens to foreground practices and projects of reconfiguring technical and other material artifacts and knowledges in gardening as political forces that shape new ways of organizing urban nature and space through infrastructure. Practices of infrastructuring gardens reveal power differentials and the instances of emerging alternative politics of urban nature. This perspective can advance geographical debates about urban infrastructure and environmental politics in three distinct ways.

First, as plants, technical artifacts, and other material objects in gardens become reconfigured through novel infrastructural practices, they become agents in governing urban nature and space. As a result, geographies of infrastructural contestations are extended into residential gardens. Adding to urban scholarship on political practices through technology (e.g., Sultana Citation2013), we have shown how plants are rendered mediating components of infrastructure development. Tracing the practices of infrastructuring gardens can highlight rationales of sufficiency or alternative purposes of water use that are embedded in landscape ecosystems. These rationales from the margins can be related to the technomanagerial logics at the center of urban water regimes, advancing geographical work on the malleability of urban infrastructures (Furlong Citation2011; Tiwale Citation2019). Thinking in terms of infrastructuring gardens thus allows us to critically interrogate abstract ideas of relationships between water, technology, and urbanization underlying entrenched urban lifestyles, patterns of urban development, and forms of urban water management. The concept further offers a heuristic to analyze politically significant relations between technology, humans, and nonhumans, which can enrich debates on more-than-human geographies with a more robust conceptualization of technology.

Second, processes of infrastructuring gardens convene different forms of expertise. In many cities, modernist approaches to managing urban nature through technology and engineering remain hegemonic. The practices of remaking semitropical Los Angeles, however, reveal urban gardens as objects of ecological and technical knowledge and formalized and practical knowledge. The political lesson to draw is the need for hitherto separate knowledge cultures to be integrated to create multibenefit urban infrastructures. Analytically, an infrastructure perspective can help foreground the importance of previously undervalued knowledge in urban environmental management. For instance, the mutual dependence of water supply policies and plant ecologies that rely on skilled maintenance can provoke new articulations of valuing urban nature and ecological work that could be seedbeds of more progressive politics of urban nature.

Finally, the notion of infrastructuring gardens outlines a specific take on the clash between the technocratic management of urban nature and gardens as spaces of everyday human and nonhuman urban life. This allows political conflicts over urban environmental management to be understood through exploring the instability of different cultures of knowing and managing nature that clash in technical disputes over infrastructure development. Geographical research on how marginalized cultures of urban nature gain infrastructural relevance alongside technocratic practices can benefit from, and inform, critical studies of technology that examine technology not as “a servant of some predefined social purpose,” but as “an environment within which a way of life is elaborated” (Feenberg Citation2010, 15). Exploring moments of infrastructure formation offers a more open-ended lens on conflicts over environmental management shaped by expertise as scrutinized by urban political ecologists (Cousins Citation2017). Similarly, urban infrastructural change can be explained by tracing how—and at what moments—actors incorporate particular artifacts into infrastructure to realize a particular infrastructure development. Although relying on specific practices, infrastructure consequently constitutes a powerful ordering mechanism of urban processes. Concepts of urban technonatures can be fruitfully expanded by taking account of this ordering power of infrastructure, thereby bringing attention to infrastructural practices and discourses that reconfigure urban technonatural relationships.

Empirically, the expansion of smart technologies from homes into gardens needs to be critically scrutinized concerning the social organization of public goods and inequitable economic relations. Smart gardening further highlights how urban subjectivities are contested at the intersection of ecological and smart city practices, which can inform nascent geographical scholarship on digital urban natures (Moss, Voigt, and Becker Citation2021). Furthermore, an infrastructure lens on urban technonatures can reveal how technically constituted power might pervade uneven political economies of ecological labor (Ernwein Citation2021) or interfere with meaning-making processes through human–plant interactions as debated by cultural geographers (Gandy Citation2022). We argue that studying how gardens become components of urban infrastructures is politically relevant. It provides an opportunity to rework a cultural dominance of technology underlying institutionalized forms of urban environmental governance. Tracing technological agency in relation to other human and nonhuman agencies in practices of infrastructuring gardens can clarify the role of technology in the “ecological pluriverse” (Gandy Citation2022) of contemporary cities. This can advance a critical study of system-based approaches to urban environmental governance. Urban gardens provide a rich repository for such an agenda. They blur the boundaries between technology and nature, public and private, and their complex biophysical and social dynamics evade complete technical control.

Acknowledgments

The Huntington Library was a great source for this research. We thank all interviewees for their time, dedication, and candor. We are grateful to Stephanie Pincetl for hosting Valentin Meilinger at the California Center for Sustainable Communities at UCLA and for inspiring discussions. A special thanks goes to Jonathan Rutherford, Sandra Jasper, three anonymous reviewers, and the editor Katie Meehan for their constructive feedback and insightful comments on earlier drafts of this article. Finally, we are grateful to Joy Burrough for her professional language editing.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Valentin Meilinger

VALENTIN MEILINGER is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Human Geography and Spatial Planning, Utrecht University, Utrecht, 3584 CB, The Netherlands. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests include the shifting relations between infrastructures, water, and landscapes in cities under climate change. He focuses on the role of technology in political disputes about urban nature.

Jochen Monstadt

JOCHEN MONSTADT is Full Professor of Governance of Urban Transitions and Chair of the Spatial Planning section in the Department of Human Geography and Spatial Planning, Utrecht University, Utrecht, 3584 CB, The Netherlands. E-mail: [email protected]. He is also Visiting Professor within the program Future—Inventing the Cities of Tomorrow at the Université Gustave Eiffel, France. His research and teaching revolve around the contingent and place-based transformation patterns of cities and how these are mediated by technical infrastructures. His specific interest is how the sociotechnical design and governance of those critical systems shape the development of cities in the Global North and South.

Notes

1 Conservationists focus on plant biodiversity but always see the latter in relation to faunal biodiversity.

2 We interviewed environmental activists (five), community representatives (two), environmental consultants (three), environmental nonprofits (eight), garden supply businesses (two), home developers (one), landscape architects and consultants (four), landscape practitioners (one), lobby organizations (one), native plant horticulturists (three), nurseries (two), public policy officers (six), public water managers (twelve), and researchers (four). Interviewees were selected to widely cover the network of stakeholders involved in landscaping and water management in Los Angeles and by snowball sampling.

3 California’s Proposition 13 (1978) cut local property taxes extensively and requires a two-thirds voter majority for tax increases. Proposition 218 (1996) regulates public service fees, limiting conservation-oriented water rate structures.

4 This equates to approximately 20 percent of the MWD’s 2018–2019 budget (MWD 2018, 29). Before then, the agency spent $20 million annually on water conservation (Interview, MWD water conservation manager, 26 February 2018).

References

- Angelo, H. 2020. How green became good: Urbanized nature and the making of cities and citizens. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Askew, L. E., and P. M. McGuirk. 2004. Watering the suburbs: Distinction, conformity and the suburban garden. Australian Geographer 35 (1):17–37. doi: 10.1080/0004918024000193702.

- Ballard, R., and G. A. Jones. 2011. Natural neighbors: Indigenous landscapes and eco-estates in Durban, South Africa. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 101 (1):131–48. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2010.520224.

- Bell, S. 2015. Renegotiating urban water. Progress in Planning 96:1–28. doi: 10.1016/j.progress.2013.09.001.

- Blok, A., M. Nakazora, and B. R. Winthereik. 2016. Infrastructuring environments. Science as Culture 25 (1):1–22. doi: 10.1080/09505431.2015.1081500.

- Bornstein, C. D. Fross, and B. O’Brien. 2005. California native plants for the garden. Los Olivos, CA: Cachuma Press.

- Brooks, A., and R. A. Francis. 2019. Artificial lawn people. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 2 (3):548–64. doi: 10.1177/2514848619843729.

- Brown, E. 2015. Executive Order B-29-15. Accessed July 19, 2021. https://www.ca.gov/archive/gov39/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/4.1.15_Executive_Order.pdf.

- California Department of Water Resources. 2018. Making water conservation a California way of life. Sacramento: California Department of Water Resources.

- Carse, A. 2012. Nature as infrastructure: Making and managing the Panama Canal watershed. Social Studies of Science 42 (4):539–63. doi: 10.1177/0306312712440166.

- Cooley, H., and R. Phurisambam. 2016. The cost of alternative water supply and efficiency options in California: Executive summary. Oakland, CA: Pacific Institute.

- Cosgrove, D. 1998. Social formation and symbolic landscape. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Cousins, J. J. 2017. Structuring hydrosocial relations in urban water governance. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 107 (5):1144–61. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2017.1293501.

- Cousins, J. J., and J. P. Newell. 2015. A political–industrial ecology of water supply infrastructure for Los Angeles. Geoforum 58:38–50. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.10.011.

- Coutard, O., and J. Rutherford. 2016. Beyond the networked city: An introduction. In Beyond the networked city: Infrastructure reconfigurations and urban change in the North and South, ed. O. Coutard and J. Rutherford, 1–25. London and New York: Routledge.

- Davison, A. 2009. Living between nature and technology: The suburban constitution of environmentalism in Australia. In Technonatures: Environments, technologies, spaces, and places in the twenty-first century, ed. D. F. White and C. Wilbert, 167–89. Waterloo, ON, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

- Ernwein, M. 2021. Bringing urban parks to life: The more-than-human politics of urban ecological work. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 111 (2):559–76. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2020.1773230.

- Feenberg, A. 2010. Between reason and experience: Essays in technology and modernity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Finewood, M. H., A. M. Matsler, and J. Zivkovich. 2019. Green infrastructure and the hidden politics of urban stormwater governance in a postindustrial city. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 109 (3):909–25. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2018.1507813.

- Fishman, R. 1987. Bourgeois utopias: The rise and fall of suburbia. New York: Basic Books.

- Furlong, K. 2011. Small technologies, big change: Rethinking infrastructure through STS and geography. Progress in Human Geography 35 (4):460–82. doi: 10.1177/0309132510380488.

- Gabrys, J. 2022. Programming nature as infrastructure in the smart forest city. Journal of Urban Technology 29 (1):13–17. doi: 10.1080/10630732.2021.2004067.

- Galperin, R. 2015. Audit of DWP customer-based water conservation programs. Cover letter, Los Angeles.

- Gandy, M. 2022. Natura urbana: Ecological constellations in urban space. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.