Abstract

Building on the work of Saidiya Hartman, Black studies scholars have long theorized and analyzed what it means to exist in the afterlife of slavery, which refers to the precarity and devaluation of Black life since chattel slavery. This article draws the natural environment into this discourse to conceptualize the biophysical afterlife of slavery. The biophysical afterlife of slavery describes how the precarity and devaluation of Black life has affected the natural environments in which these lives exist. Slavery left lingering impacts on soil, water, and vegetation regimes as it maneuvered and settled across the earth, but importantly, its ideological and sociopolitical legacies continue to impact Black ecologies today. I argue that to methodologically attend to the biophysical afterlife of slavery there must be a meaningful integration of critical physical geography and Black geographies. As an example of this integration, I suggest that there is a myriad of methods used to reconstruct environmental histories, such as dendrochronology that, when brought together with a Black geographies lens, create mechanisms to analyze the past, present, and future of the biophysical afterlife of slavery.

长期以来, 研究黑人的学者根据赛迪亚·哈特曼(Saidiya Hartman)的研究, 理论化并分析了奴隶制来世(即, 自奴隶制以来黑人生命的动荡和贬值)的含义。本文通过引入自然环境, 对奴隶制的生物物理来世进行了概念化。奴隶制的生物物理来世, 描述了黑人生命的动荡和贬值如何影响黑人所处的自然环境。奴隶制在全球范围内的实施和扎根, 给土壤、水和植被体系留下了挥之不去的影响。重要的是, 奴隶制意识形态和社会政治的遗留, 继续影响着当今的黑人生态。我认为, 如果要在方法论上关注奴隶制的生物物理来世, 必须有机地结合批判自然地理和黑人地理。作为这种结合的例子, 我建议采用多种方法去重建环境历史(例如, 树木年轮学)。这些方法与黑人地理相结合, 可以建立奴隶制生物物理来世的过去、现在和未来的分析机制。

A partir del trabajo de Saidiya Hartman, los estudiosos de problemas negros han teorizado y analizado durante mucho tiempo lo que significa existir en la vida futura de la esclavitud, cosa que se refiere a la precariedad y devaluación de la vida de los negros desde ser una propiedad en la esclavitud. Este artículo incorpora el medio ambiente natural en este discurso para conceptualizar la vida futura biofísica de la esclavitud. El relicto biofísico de la esclavitud describe cómo la precariedad y la devaluación de la vida de la gente negra ha afectado los entornos naturales en los que discurren estas vidas. La esclavitud dejó persistentes impactos en el suelo, el agua y los regímenes de la vegetación a medida que discurría y se asentaba sobre la tierra, si bien, de modo más importante, se evidencia que sus legados ideológicos y sociopolíticos continúan impactando las ecologías negras de la actualidad. Arguyo que para atender metodológicamente los relictos biofísicos de las esclavitud debe mediar una integración significativa de la geografía física crítica y las geografías negras. Como ejemplo de tal integración, sugiero que se dispone de una multitud de métodos usados para reconstruir historias ambientales, como la dendrocronología que, al juntarse con la lente de las geografías negras, pueden crear mecanismos para analizar el pasado, el presente y el futuro de las secuelas biofísicas de la esclavitud.

Black studies scholar Saidiya Hartman (Citation2007) describes the “afterlife of slavery” as “black lives still imperiled and devalued by a racial calculus and a political arithmetic that were entrenched centuries ago. This is the afterlife of slavery—skewed life chances, limited access to health and education, premature death, incarceration, and impoverishment” (6). Building on Hartman’s work, many scholars have examined how anti-Black logics and structures persist in the present day, shaping many aspects of Black life, such as maternal health and reproduction (Weinbaum Citation2013; D. A. Davis Citation2019), prisons and incarceration rates (Dillon Citation2012; Guenther Citation2013; LeFlouria Citation2015), immigration (Willoughby-Herard Citation2014; Sharpe Citation2016), and education (Grant, Woodson, and Dumas Citation2020). In her book In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, Sharpe (Citation2016) positions anti-Black sociopolitical processes and the immanence and imminence of Black premature death as the atmosphere of anti-Blackness surrounding Black life in the wake of the slave ship. In this article, I discuss the significance of the afterlife of slavery and this atmosphere of anti-Blackness to the natural environment.

I develop the notion of a biophysical afterlife of slavery, which I conceptualize as how the precarity and devaluation of Black life have affected the biophysical environments in which these lives exist. This biophysical afterlife is twofold. First, there are long-term ecological impacts of the extractive, expansive, and monocultural practice of slavery. The afterlife of slavery, however, is not only the impact that those practices had on the specific people and places involved in slavery. The afterlife of slavery also encompasses the logics, ideologies, and structures embedded in legal and social systems that legitimated slavery and continue to maintain hierarchies of human life today. Thusly, the biophysical afterlife of slavery also encompasses how those logics, ideologies, and structures affect natural environments throughout the Black diaspora. This framing foregrounds precarity, devaluation, and persistence of Black life as bound up in and with the biophysical environments in which Black people have worked, lived on, cultivated, and love.

I argue that the combination of Black geographies and critical physical geography (CPG) creates the integration of critical studies of race, racism, and racialization and environmental science methods necessary to attend to the ecological entrenchments of slavery and its afterlives. There is a myriad of methods used to reconstruct environmental histories that, when brought together through a Black geographies lens, create mechanisms to analyze the past, present, and future of the biophysical afterlife of slavery. I provide examples of such work, drawing in cutting-edge scholarship from other fields, such as geology, archeology, and ecology. I also explain how dendrochronology, critical environmental justice (EJ), and Black geographies can be harnessed to access memories of anti-Black environmental injustice as well as Black ecological life.

The Afterlife of Slavery in Environmental Politics and Humanities

Scholars studying race, racism, and racialization in various disciplines have provided analyses of the ways anti-Blackness and social legacies of slavery are embedded in environmental politics and relations for some decades now. Wynter explains how the category of the “human” has shifted over time and through various waves of human “enlightenment” and scientific knowledge discoveries, perpetually leaving non-White populations out of the category of human. This stratification of humanity shaped the state of the social and ecological world and the simultaneous violence on racialized others and various ecologies (Wynter Citation1971, Citation1995). Dehumanization and mutual exploitation of both racialized peoples and the environment makes cause for a new conception of what it was and is to be considered “human” and rethink how we relate to each other and the ecological world around us (McKittrick Citation2015).

McKittrick posits that Wynter’s work draws

attention to how race figures into genealogies that ask not only what it means to be human, but also how we came to be human in ways that are adverse to blackness and co-relatedly, how—for the sake of not just our collective selves but the planet, whose environmental decline began with slaves moving across the middle passage, a logic we still adulate and replicate!—we must redefine the human in new ways! (Hudson and McKittrick Citation2014, 236)

This quote draws out some of the lineage of McKittrick’s interventions in geography, and in particular, the ways she identifies how the plantation and its logics have moved through time and space to inform geographic and environmental relations today. McKittrick (Citation2011) argues that the plantation set forth a blueprint for two geographic processes we witness today: positioning Black peoples as ageographic and placeless and the ecological extraction that accompanies this racial violence. Yet, McKittrick’s (Citation2011, Citation2013) body of work highlights that practices from the plantation past, too, inform the insistence and forging of belonging and ecological relationships, even within processes and localities of subjugation and domination.

Plantation legacies in environmental politics, relations, and land use has emerged as a theme in Black geographies. The work of Woods (Citation1998, Citation2017) examines the role of the plantation and its political economic legacies in informing various iterations of extraction, land degradation, and anti-Black politics across the U.S. South, and how the politics and initiatives of this region on this front made their way to the national scale. This literature highlights the interlinkage between politics and capital accumulation undergirded by anti-Blackness and ecological extraction, processes naturalized by slavery (see also Gilmore Citation2007; Bledsoe and Wright Citation2019). In the vein of Woods, several scholars have illuminated various examples of plantation logics interwoven in sites and political processes of environmental injustice, particularly across the U.S. South (Roane and Hosbey Citation2019; Purifoy Citation2021; Williams Citation2021; Wright Citation2021). More than environmental subjugation, Black geographies scholars have illustrated how modes of struggle against domination, place making, and cultivating ecological relationships for survival, particularly in the form of marronage, too, have been passed down to Black populations living in the wake of slavery (Bledsoe Citation2017, Citation2019; Wright Citation2019; Hosbey and Roane Citation2021; Winston Citation2021).

Black geographies scholarship has made it clear that social and political processes that leave Black communities to disproportionately experience environmental pollution and climate change impacts are deeply informed by plantation logics of dehumanization of Black populations and ecological degradation for the sake of capital accumulation. But in addition to deciphering the social, political, and economic processes in this anti-Black atmosphere, we must also remember that the degradation and environmental impact of anti-Blackness are also ecological and biophysical processes. Soils modified. Plant life changed. Wildlife affected. Coastlines, waterscapes, and aquatic life shifted. In the wake of slavery, the very ground beneath the feet of Black communities has been and continues to be affected and altered. This is what I consider the biophysical afterlife of slavery.

The Biophysical Afterlife of Slavery

The sociopolitical aspects that comprise the afterlife of slavery have seeped into ecologies and natural environments around the globe. The project of slavery left long-term impacts on soils (Richter and Markewitz Citation2001; Critical Ecology Lab Citation2021; Pierre and Palawat Citation2021), vegetation regimes (Hanks et al. Citation2021), and oceans and waterways (Divers with a Purpose Citation2021). Slavery, however, did not solely affect the lands and ecologies that it came into contact with as it maneuvered and settled across the earth. As Black studies scholars have indicated, the social impacts of slavery moved beyond the temporal and spatial bounds within which slavery was enacted. So, too, do the ecological impacts. The logics and structures that formulate the social afterlife of slavery also legitimate and naturalize the degradation and decimation of Black ecologies today. This characterizes the biophysical afterlife of slavery, which describes how the precarity and devaluation of Black life has affected the biophysical environments in and with which these lives exist.

Sites of environmental racism in the U.S. South particularly epitomize the biophysical afterlife of slavery for me. The once-stronghold of U.S. slavery currently holds some of the highest concentrations of Black populations in the United States and numerous Black communities facing environmental injustice as they host a disproportionate amount of environmental burdens, particularly oil and gas processing facilities and waste sites (Bullard Citation1990a, Citation1990b; McGlinn Citation2000; Wilson et al. Citation2010). Bullard (Citation1993) declares that the petrochemical domination of the region resembles that of the plantation regime across the “Old South” (13), referring to the slavery era. In this region where enslaved folks once labored in plantations and ranches, now their descendants, too, find their lives and surrounding ecologies imperiled for the benefit of capital. Davies’s (Citation2018) article “Toxic Space and Time: Slow Violence, Necropolitics, and Petrochemical Pollution” provides one example of this. This account includes residents’ descriptions of trees beginning to produce less fruit and leaves changing from a vibrant green to a “yellowish green” in a Black EJ community in Louisiana, specifically in Cancer Alley, a region riddled with numerous oil and gas facilities and recurrent Black premature death. This ecological change stems from and works hand in hand with anti-Black environmental injustice.

These modes of degradation stemming from slavery and its ideological and ecological afterlives do not pass through the landscapes unnoticed. They often leave traces in the trees, in lakes, in soils, and much more. The biophysical afterlife of slavery framework introduces a pathway to integrate environmental science knowledge and theory with work on racial ecologies, shaping an approach that brings nuance and depth to the material and biophysical mechanics of environmental degradation in Black ecologies. This framework argues for the theoretical and methodological integration of Black geographies and CPG to emphasize how questions of race, racism, and racialization are, and have always been, relevant to ecologies and ecological research.

Integrating Black Geographies and Critical Physical Geography

Attending to the biophysical afterlife of slavery requires an interdisciplinary approach. Indeed, McKittrick and Woods (Citation2007) posit that Black geographies “demand an interdisciplinary understanding of space and place-making that enmeshes, rather than separates, different theoretical trajectories and spatial concerns” (7). Black geographies, as an integration of Black studies and geography, epitomizes this interdisciplinarity as scholars draw from archival, policy, ethnographic, artistic, poetry, novels, and traditional social science sources to make powerful insights into Black geographic and ecological life (see also Bledsoe Citation2021). Environmental science methods largely have yet to be incorporated into Black geographies scholarship, however.

CPG, on the other hand, foregrounds environmental science, particularly physical geography, and advocates for critical attention to the social and historical factors that shape biophysical landscapes. Critical physical geographers stress that “socio-biophysical landscapes are as much the product of unequal power relations, histories of colonialism, and racial and gender disparities as they are of hydrology, ecology, and climate change” (Lave et al. Citation2014, 2). The goal of interdisciplinarity in CPG is threefold. First, CPG scholars want to stress the social and biophysical coproduction of landscapes (Lave et al. Citation2014; Holifield and Day Citation2017; Lave, Biermann, and Lane Citation2018). This is particularly an important conviction for those analyzing the Anthropocene and its inherent eco-social nature (Biermann, Lane, and Lave Citation2018; Urban Citation2018; Biermann, Kelley, and Lave Citation2021). Second, they aim to foster critical questioning of traditional scientific practices within the natural sciences (Lave Citation2015; Tadaki et al. Citation2015; Lane Citation2017; Lave, Biermann, and Lane Citation2018). Finally, this scholarship sets out to highlight the socioecological impacts of research and knowledge production (Lave, Biermann, and Lane Citation2018).

CPG scholars have articulated, since its inception, that questions of power and justice are central to the subfield’s agenda (Lave et al. Citation2014; Lave, Biermann, and Lane Citation2018). Scholars have employed a CPG approach to expose inherent coloniality, oppression, and violence in hegemonic environmental science and environmental management practices (Barron et al. Citation2015; Duvall, Butt, and Neely Citation2018; Colucci et al. Citation2021; Correia Citation2022). Moreover, in its aim to produce more reflexive science, CPG has provided studies emphasizing the importance of community voice in shaping research agendas and questions (Biehler et al. Citation2018). Furthermore, CPG scholarship has argued for approaches that increase the policy impact of political ecological research (Lave Citation2014). Although CPG scholars have applied this approach to identify racial disparities in environmental experiences and protections (Biehler et al. Citation2018; Spears Citation2021), there has been little work that integrates critical approaches to geographies of race or nondominant epistemologies (see McClintock Citation2015; Correia Citation2022 for exception).

McKittrick teaches us that naming violence without highlighting the systematic underpinnings and subaltern modes of struggle and living against this violent system leaves us in the same place (McKittrick Citation2011, Citation2016; Hudson and McKittrick Citation2014). “No one moves” (McKittrick, Citation2016, 16). Therefore, naming racial disparities and making policy interventions are important, but we must understand that such policy will be but one thread within a political economic system bound together by plantation and colonial logics. Moreover, how can we do environmental science research and outcomes in and with racialized communities in ways that honor subaltern ways of knowing space and place and modes of struggle for decolonization and abolition? How can we truly hope to abolish the biophysical afterlife of slavery without it?

Understanding, analyzing, and working to abolish the biophysical afterlife of slavery entails a deep understanding of the sociopolitical and ideological processes that hold the afterlife of slavery in place as well as intricate understandings of biophysical function. An integration of the strengths of Black geographies and CPG shapes one appropriate theoretical and methodological framework for this task. This drawing together of Black geographies frameworks and variations of environmental science has largely not been practiced, with a few notable exceptions in geology, archeology, and ecology. Yusoff (Citation2018) draws on extensive research on geology’s rise a as discipline and arbiter of geologic eras. The author highlighted the ways scientific racism and notions of the human have coursed through the field and its process to differentiate scientific time periods. Yusoff (Citation2018) and J. Davis et al. (Citation2019) stress that discourse on the Anthropocene, and even those aiming to nuance this literature by emphasizing the importance of capitalism and the rupture between human and nonhuman life, have largely neglected the role of race and the contributions of Black geographies epistemologies on Black ecological life and repair.

Several archeologists and community scientists of the organization Divers with a Purpose have integrated the science of archeology and ocean conservation principles and practices with work to honor enslaved African ancestors lost in slave trade shipwrecks found in the depths of the ocean (Divers with a Purpose Citation2021). This work has led not only to the discovery and honoring of ancestors at various slave trade shipwreck sites across the Atlantic, but also novel approaches to oceanic mapping and understandings of maroon geographies (Dunnavant Citation2021).

Soils and land have long been central to the description of Black people as enslaved labor, working soils for white capitalist accumulation. Recently, however, various scholars have urged us to move beyond this connection to land that is essentialized to labor (King Citation2019; Moulton Citation2021). Soils have been chronicled as sites of memory and care (Sharpe Citation2018; Moulton Citation2021), connection to place and ancestors (Reese Citation2019; Moulton Citation2021), and sites of resistance and resilience (Jones Citation2019; McCutcheon Citation2019; Reese Citation2019). In addition to this necessary reframing of Black connections to soils, ecologists Suzanne Pierre and the Critical Ecology Lab (Citation2021) are working to highlight the long-term impacts that slavery had on soils and plant communities throughout the Black diaspora. These examples shed light on what it might look like to bring earnest engagements with critical approaches to histories and the present of Black subjugation, living, and struggle to environmental science and vice versa.

These two areas of research might seem rather disparate, but they have always been relevant to each other. In fact, the notion of the past influencing the present and future is not far from ecological research. Ecological memory is a concept that refers to “the capacity of past states or experiences to influence present or future responses of the community” (Padisak Citation1992, 225; see also Peterson Citation2002; Silva Citation2015). In other words, it suggests that the past shapes the present and influences the future, ecologically. Consider also legacy effects, referring to the impacts of the past on present landscapes and biophysical processes (Roman et al. Citation2018), and legacy sediments, which refers to extensive anthropogenic sediment produced or deposited in a particular period of decades or centuries (James Citation2013). These concepts highlight the compatibility of ecological memory research and research on the afterlife of slavery as both look to the past to make sense of the present.

Black Ecological Memory

I propose that we apply what Campt (Citation2021) calls a “Black gaze” to methodologies of assessing ecological histories, such as environmental records, particularly in Black ecologies. Campt describes the Black gaze not only as a Black viewpoint, but also a call to shift one’s perspective to align with the experiences of Black precarity and life. Campt suggests that it allows one to empathize, to be implicated, and to witness. It is a witnessing of Black past, present, and future experiences. Applying a Black geographies lens to research on ecologies of the past and present allows one to understand the biophysical environment as a witness. Witnessing, mutually experiencing, and remembering the ecological ramifications of the precarity and devaluation of Black life, such as soil degradation from the monocultural and exhaustive practice of slavery or contamination from expansive oil and gas production and processing. Through this lens, we can understand these records of past environments in relation to the racial politics and ideologies that shaped the spatialities of degenerative environmental practices.

Understanding the biophysical environment as an archive or a witness is not new. Many in the natural sciences have long dug into trees, soils, lakes, ice sheets, and more to uncover information about past environments. Even within Black studies, scholars have discussed understanding the surrounding natural environment as a witness to what has historically occurred to Black people. For example, one can think of Billie Holiday’s blues song “Strange Fruit” as those trees witnessed the violence of lynching (Wright Citation2021). Also, Black feminist scholars such as Brand (Citation2002), Hartman (Citation2007), and Sharpe (Citation2016, Citation2018) have discussed the materiality of what is left behind today of enslaved folks in holding cells, on the bottom of the oceans, and even in the soil at lynching sites. This offers a reading of the natural environment as holding traces of the past, in particular, relating to slavery and its afterlives.

I draw on these diverse approaches framing the natural environmental as a witness and remembering events in our racialized past to ask these questions: What archives of the entanglement of anti-Blackness and ecological degradation in the afterlife of slavery might the biophysical landscape hold? What has the surrounding environment witnessed? What memories does it hold within it? How might we access those memories? I suggest that methods used to reconstruct environmental histories, such as analyses of tree cores, lake cores, or soils, when brought together with a Black geographies lens, create mechanisms to analyze the past, present, and future of the biophysical afterlife of slavery. The mutual experiences of Black communities and their surrounding ecologies are remembered in various records of environmental history.

Trees are one example of an environmental record with internal characteristics that can be used to reconstruct past environments. In this section, I want to explore how dendrochronology can be deployed to attend to the two parts of McKittrick’s call: positioning racial violence within its systematic underpinnings and centering subaltern modes of struggle, knowing, and living against this violent system.

What Trees Remember

As a scholar focused on anti-Black environmental injustice along the U.S. Gulf Coast, I have focused on the potential for trees to hold histories of contamination in their rings. Many studies within dendrochemistry, the chemical analysis of tree rings, show that, due to their ability to store contaminants within their rings, trees provide natural archives of histories of contamination within industrial areas (Balouet and Oudijk Citation2005; Saint-Laurent et al. Citation2011; Doucet et al. Citation2012; Austruy et al. Citation2019; Muñoz et al. Citation2019; Alterio et al. Citation2020). Contaminants primarily enter trees through atmospheric deposition and absorption from soil (Kabata-Pendias Citation1984; Shaw Citation1990; Engel-Di Mauro Citation2014; Sullivan Citation2017). Furthermore, especially pertinent to my work along the U.S. Gulf Coast, a site with recurrent and increasingly intense hurricanes, dendrochronological studies have shown that trees can be used to understand the various characteristics of tropical cyclones over time (Maxwell et al. Citation2021). Moreover, several studies have found that hurricane and tropical storm events can dislocate and spread contaminants stored in soil and industrial facilities to proximal communities (Reible et al. Citation2006; Santella, Steinberg, and Sengul Citation2010; Horney et al. Citation2018).

Trees in EJ communities mutually experience anti-Black environmental injustice, and they remember. We can access these memories through elemental chemical analysis, most often inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) or X-ray fluorescence (XRF), of tree samples after determining their chronology (Binda et al. Citation2021). Environmental monitoring is usually already practiced in EJ communities; however, trees are not simply a snapshot of the present state of environmental injustice. They are natural archives, presenting data on the present in the more recent rings as well as the bark, but also more historical contamination information from earlier rings. Notably, Muñoz et al. (Citation2019) and Alterio et al. (Citation2020) found that tree archives contain not only a deeper history than environmental agency contamination records, but also these natural archives can contain a more cumulative record of contamination due to the various contaminant entry sites. The importance of this sort of analysis in Black geographies is twofold. First, historical and present contamination information highlights that this experience of high concentrations of pollution and contamination is not just a right-now issue, and it should not be approached as a solely right-now issue. This is evidence of the perpetuation. We need to attend to the systematic, long-standing processes, social and ecological, that brought and continue to bring this situation of disproportionate burden into being; that is, the biophysical afterlife of slavery. And second, these biophysical archives have the potential to provide information about the ecological lives and experiences of racialized others who are often left out of the conventional colonial and hegemonic archives. They can be understood in combination with oral traditions and other subaltern forms of passing down marginalized histories, providing a richness, and importantly, not occluding these traditions.

What Else Happened?

Accessing memories about histories of racialized environmental violence is important. Black geographies, however, asserts that Black life and Black spaces are not solely containers of violence, death, and degradation. When thinking about these tree archives, and the information they make available, I wonder about what McKittrick (Citation2014) calls the “what else happened” (22). This question draws on analytical practice in Black studies to attend to Black life and subjectivity too often left out of traditional archives, but certainly happening (Hartman Citation2008; McKittrick Citation2014; King Citation2019). In this approach, I want to put into practice King’s (Citation2019) suggestion, built off of McKittrick, to “read intertextually” producing “unexpected openings … where different voices are brought into relationship” and allow one to “betray the archive of violence to look, listen, and feel for ‘what else happened’” (30).

King (Citation2019) evokes the notion of porosity to describe the relationality and intimacy between human and nonhuman life. Wood porosity is important for tree growth and much of its interaction with surroundings. Dendrochemical approaches help us to understand trees as witnesses, and even mutually experiencing, anti-Black environmental violence. These trees also mutually survived, however, drawing up, though pores and other openings, trace elements, chemicals, and stories of Black life.

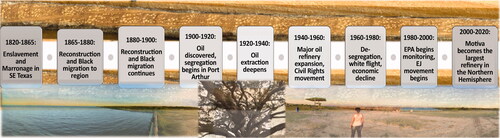

My dendrochemical analysis focuses on Port Arthur, Texas, a Black town nestled in what the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) called the “largest oil refinery network in the world,” which includes the largest refinery in the Northern Hemisphere, the Motiva Refinery (U.S. EPA Citation2010). My own family has generational ties to this city, with many still living there (Bruno Citationforthcoming). depicts a timeline with various events in the racial and social history of Port Arthur, drawn from archival research, atop a high-resolution scan of a tree core from Port Arthur with images representing Black ecological life from the city along the bottom half of the graphic. To read intertextually, my research draws on archives of Black ecological life, including my own lived experience, oral traditions, community members’ oral histories, and community member family albums, to access and imagine what else happened in the mutual life of the trees I study and the surrounding community. Black Port Arthur residents shared profound relationships to community, place, and the environment that have thrived in the midst of decades of racial violence, environmental pollution, and intense climate change impacts.

Conclusion

Scholars in Black studies and Black geographies have provided powerful theoretical and analytical understandings of the legacies of slavery in the broader sociopolitics surrounding Black life, environmental politics, and nondominant ways of knowing and relating to space, place, and the environment. In this article, I honor and expand on this body of literature by proposing the notion of the biophysical afterlife of slavery. The biophysical afterlife of slavery describes how the precarity and devaluation of Black life, which is the essence of the social-political afterlife of slavery (Hartman Citation2007), has affected the biophysical environments that Black people have worked, lived on, cultivated, and love. This framework highlights not only the ways slavery left ecological legacies in soil, water, and vegetation regimes, but also how the ideological, social, and political legacies of slavery continue to affect Black ecologies, biophysically, through pollution, disproportionate impacts of climate change, and other forms of ecological degradation.

I argue that the coalescing of Black geographies and CPG is fertile grounds for integrating deep understandings of various types of environmental sciences with rich understanding of racialized life and the histories that have shaped it. Dialectically, this article intervenes in critical approaches to physical geography. Such work has been deployed to highlight present-day racial disparities in various environmental burdens, degradation, and climate change impacts. Black geographies provide theory and methods to position these disparities historically and within a broader, long-standing system rooted in plantation logics. Moreover, the Black geographies field has cautioned scholars not to solely represent Black life, places, and spaces as containers of blight, death, and degradation. There are life, a sense of place, and strong ecological relationships forged in Black geographies, in spite of these degrading and dominating factors. So what more can CPG do for racial justice than naming violence? How can we know Black ecological life differently?

Various environmental sciences can be deployed to attend to the biophysical afterlife of slavery. One example I have presented is Black ecological memory, which integrates Black geographies and environmental records. I posit that environmental records can be used to understand what Black ecologies remember as they witnessed and mutually experienced anti-Black environmental violence. Moreover, I draw on Black geographies approaches to archives and interdisciplinary methods to explore “what else happened” other than violence and degradation. What was forged despite it?

Knowledge of the nuances and intricacies of the environmental impacts linked to slavery and its afterlives gleaned from CPG approaches can be joined with ecological knowledge passed down to us (Woods Citation2017; Caribbean Women Healers Project Citation2022) for gaining a deeper understanding of the ecological life of ancestors, left out of traditional archives. Importantly, though, this knowledge can be harnessed to know, assess, and act for our biophysical futures informed of the gravity for our communities, cultures, and practices. My overall aim in this article urges those concerned with racial justice and the environment to think about the ways critical approaches to environmental science can be woven into the new, more just, world-building practices imbedded in and coming from subaltern epistemologies, in particular Black geographies.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Laura Pulido, Alaí Reyes-Santos, Lucas Silva, Leigh Johnson, Jordache Ellapen, Ashanté Reese, Caroline Faria, Erin Goodling, Sophia Ford, the University of Oregon Critical Race Lab, and the University of Texas-Austin Feminist Geography Collective for their encouragement and feedback on early drafts of this article. I also thank Katie Meehan and my reviewers for their insightful and critical feedback and guidance that helped strengthen the arguments of this article. Any errors are mine alone.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tianna Bruno

TIANNA BRUNO is a Provost’s Early Career Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Geography and the Environment, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712. E-mail: [email protected]. Her research focuses on the intersection of Black geographies, critical environmental justice, political ecology, and critical physical geography with an aim to foreground Black life, sense of place, and relationships to the environment within spaces of environmental injustice.

References

- Alterio, E., C. Cocozza, G. Chirici, A. Rizzi, and T. Sitzia. 2020. Preserving air pollution forest archives accessible through dendrochemistry. Journal of Environmental Management 264:110462–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110462.

- Austruy, A., L. Yung, J. P. Ambrosi, O. Girardclos, C. Keller, B. Angeletti, J. Dron, P. Chamaret, and M. Chalot. 2019. Evaluation of historical atmospheric pollution in an industrial area by dendrochemical approaches. Chemosphere 220:116–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.12.072.

- Balouet, J. C., and G. Oudijk. 2005. The use of dendroecological methods to estimate the time frame of environmental releases. Environmental Claims Journal 18 (1):35–52. doi: 10.1080/10406020600561309.

- Barron, E. S., C. Sthultz, D. Hurley, and A. Pringle. 2015. Names matter: Interdisciplinary research on taxonomy and nomenclature for ecosystem management. Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment 39 (5):640–60. doi: 10.1177/0309133315589706.

- Biehler, D., J. Baker, J. Pitas, Y. Bode, R. Jordan, A. E. Sorensen, S. Wilson, H. Goodman, M. Saunders, D. Bodner, et al. 2018. Beyond “the Mosquito People”: The challenges of engaging community for environmental justice in infested urban spaces. In The Palgrave handbook of critical physical geography, ed. R. Lave, C. Biermann, and S. Lane, 295–318. Cham: Palgrave.

- Biermann, C., L. C. Kelley, and R. Lave. 2021. Putting the Anthropocene into practice: Methodological implications. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 111 (3):808–18. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2020.1835456.

- Biermann, C., S. N. Lane, and R. Lave. 2018. Critical reflections on a field in the making. In The Palgrave handbook of critical physical geography, ed. R. Lave, C. Biermann, and S. Lane, 559–73. Cham: Palgrave.

- Binda, G., A. D. Iorio, and D. Monticelli. 2021. The what, how, why, and when of dendrochemistry: (paleo)environmental information from the chemical analysis of tree rings. The Science of the Total Environment 758:143672. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143672.

- Bledsoe, A. 2017. Marronage as a past and present geography in the Americas. Southeastern Geographer 57 (1):30–50. doi: 10.1353/sgo.2017.0004.

- Bledsoe, A. 2019. Afro-Brazilian resistance to extractivism in the Bay of Aratu. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 109 (2):492–501. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2018.1506694.

- Bledsoe, A. 2021. Methodological reflections on geographies of blackness. Progress in Human Geography 45 (5):1003–21. doi: 10.1177/0309132520985123.

- Bledsoe, A., and W. J. Wright. 2019. The anti-Blackness of global capital. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 37 (1):8–26. doi: 10.1177/0263775818805102.

- Brand, D. 2002. A map to the door of no return: Notes to belonging. Toronto: Vintage Canada.

- Bruno, T. Forthcoming. More than just dying: Black life and futurity in that face of state-sanctioned environmental racism.

- Bullard, R. 1990a. Dumping in Dixie: Race, class, and environmental quality. London and New York: Routledge.

- Bullard, R. 1990b. Ecological inequities and the New South: Black communities under siege. The Journal of Ethnic Studies 17 (4):101–15.

- Bullard, R. 1993. Confronting environmental racism: Voices from the grassroots. Boston: South End Press.

- Campt, T. 2021. A Black gaze: Artists changing how we see. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Caribbean Women Healers Project. 2022. The Healers Project: Decolonizing knowledge within Afro-Indigenous traditions. Eugene: The University of Oregon.

- Colucci, A. R., J. A. Tyner, M. Munro-Stasiuk, S. Rice, S. Kimsroy, C. Chhay, and C. Coakley. 2021. Critical physical geography and the study of genocide: Lessons from Cambodia. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 46 (3):780–93. doi: 10.1111/tran.12451.

- Correia, J. E. 2022. Between flood and drought: Environmental racism, settler waterscapes, and Indigenous water justice in South America’s Chaco. Annals of the American Association of Geographers. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2022.2040351.

- Critical Ecology Lab. 2021. Ecological scars of slave plantations. Santa Rosa, CA: Inquiring Systems Inc.

- Davies, T. 2018. Toxic space and time: Slow violence, necropolitics, and petrochemical pollution. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108 (6):1537–53. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2018.1470924.

- Davis, D. A. 2019. Trump, race, and reproduction in the afterlife of slavery. Cultural Anthropology 34 (1):26–33. doi: 10.14506/ca34.1.05.

- Davis, J., A. A. Moulton, L. Van Sant, and B. Williams. 2019. Anthropocene, capitalocene, … plantationocene? A manifesto for ecological justice in an age of global crises. Geography Compass 13 (5):e12438–15. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12438.

- Dillon, S. 2012. Possessed by death: The neoliberal-carceral state, black feminism, and the afterlife of slavery. Radical History Review 112 (112):113–25. [Mismatch

- Divers with a Purpose. 2021. About us: Mission and vision. Accessed August 1, 2021. https://divingwithapurpose.org/

- Doucet, A., M. M. Savard, C. Bégin, J. Marion, A. Smirnoff, and T. B. M. J. Ouarda. 2012. Combining tree-ring metal concentrations and lead, carbon and oxygen isotopes to reconstruct peri-urban atmospheric pollution. Tellus B: Chemical and Physical Meteorology 64 (1):19005. doi: 10.3402/tellusb.v64i0.19005.

- Dunnavant, J. P. 2021. Have confidence in the sea: Maritime maroons and fugitive geographies. Antipode 53 (3):884–905. doi: 10.1111/anti.12695.

- Duvall, C., B. Butt, and A. Neely. 2018. The trouble with Savanna and other environmental categories, especially in Africa. In The Palgrave handbook of critical physical geography, ed. R. Lave, C. Biermann, and S. Lane, 107–27. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. dio: 10.1007/978-3-319-71461-5_6.

- Engel-Di Mauro, S. 2014. Ecology, soils, and the left: An ecosocial approach. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gilmore, R. W. 2007. Golden gulag: Prisons, surplus, crisis, and opposition in globalizing California. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Grant, C. A., A. N. Woodson, and M. J. Dumas. 2020. The future is Black: Afropessimism, fugitivity, and radical hope in education. London and New York: Routledge.

- Guenther, L. 2013. Solitary confinement: Social death and its afterlives. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Hanks, R. D., R. F. Baldwin, T. H. Folk, E. P. Wiggers, R. H. Coen, M. L. Gouin, A. Agha, D. D. Richter, and E. L. Fields-Black. 2021. Mapping antebellum rice fields as a basis for understanding human and ecological consequences of the era of slavery. Land 10 (8):831. doi: 10.3390/land10080831.

- Hartman, S. 2007. Lose your mother: A journey along the Atlantic slave route. New York: Macmillan.

- Hartman, S. 2008. Venus in two acts. Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 12 (2):1–14. doi: 10.1215/-12-2-1.

- Holifield, R., and M. Day. 2017. A framework for a critical physical geography of “sacrifice zones”: Physical landscapes and discursive spaces of frac sand mining in western Wisconsin. Geoforum 85:269–79. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.08.004.

- Horney, J. A., G. A. Casillas, E. Baker, K. W. Stone, K. R. Kirsch, K. Camargo, T. L. Wade, and T. J. McDonald. 2018. Comparing residential contamination in a Houston environmental justice neighborhood before and after Hurricane Harvey. PLoS ONE 13 (2):e0192660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192660.

- Hosbey, J., and J. T. Roane. 2021. A totally different form of living: On the legacies of displacement and marronage as black ecologies. Southern Cultures 27 (1):68–73. doi: 10.1353/scu.2021.0009.

- Hudson, P. J., and K. McKittrick. 2014. The geographies of blackness and anti-blackness. The CLR James Journal 20 (1–2):233–40. doi: 10.5840/clrjames201492215.

- James, L. A. 2013. Legacy sediment: Definitions and processes of episodically produced anthropogenic sediment. Anthropocene 2:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ancene.2013.04.001.

- Jones, N. 2019. Dying to eat? Black food geographies of slow violence and resilience. Acme 18 (5):1076–99.

- Kabata-Pendias, A. 1984. Trace elements in soils and plants. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- King, T. L. 2019. The black shoals: Offshore formations of black and native studies. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Lane, S. N. 2017. Slow science, the geographical expedition, and Critical Physical Geography. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien 61 (1):84–101. doi: 10.1111/cag.12329.

- Lave, R. 2014. Engaging within the academy: A call for critical physical geography. ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 13 (4):508–15.

- Lave, R. 2015. Introduction to special issue on critical physical geography. Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment 39 (5):571–75. doi: 10.1177/0309133315608006.

- Lave, R., C. Biermann, and S. Lane. 2018. The Palgrave handbook of critical physical geography, ed. R. Lave, C. Biermann, and S. Lane. Cham: Palgrave.

- Lave, R., M. W. Wilson, E. S. Barron, C. Biermann, M. A. Carey, C. S. Duvall, L. Johnson, K. M. Lane, N. McClintock, D. Munroe, et al. 2014. Intervention: Critical physical geography. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien 58 (1):1–10. doi: 10.1111/cag.12061.

- LeFlouria, T. L. 2015. Chained in silence: Black women and convict labor in the New South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press Books.

- Maxwell, J. T., J. C. Bregy, S. M. Robeson, P. A. Knapp, P. T. Soulé, and V. Trouet. 2021. Recent increases in tropical cyclone precipitation extremes over the US east coast. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 118 (41):1–8.

- McClintock, N. 2015. A critical physical geography of urban soil contamination. Geoforum 65:69–85. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.07.010.

- McCutcheon, P. 2019. Fannie Lou Hamer’s freedom farms and black agrarian geographies. Antipode 51 (1):207–24. doi: 10.1111/anti.12500.

- McGlinn, L. 2000. Spatial patterns of hazardous waste generation and management in the United States. The Professional Geographer 52 (1):11–22. doi: 10.1111/0033-0124.00201.

- McKittrick, K. 2011. On plantations, prisons, and a black sense of place. Social & Cultural Geography 12 (8):947–63. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2011.624280.

- McKittrick, K. 2013. Plantation futures. Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 17 (3):1–15. doi: 10.1215/07990537-2378892.

- McKittrick, K. 2014. Mathematics Black life. The Black Scholar 44 (2):16–28. doi: 10.1080/00064246.2014.11413684.

- McKittrick, K. 2015. Sylvia Wynter: On being human as praxis. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- McKittrick, K. 2016. Diachronic loops/deadweight tonnage/bad made measure. Cultural Geographies 23 (1):3–18. doi: 10.1177/1474474015612716.

- McKittrick, K., and C. Woods. 2007. Black geographies and the politics of place. Toronto: Between the Lines.

- Moulton, A. A. 2021. Black monument matters: Place-based commemoration and abolitionist memory work. Sociology Compass 15 (12):1–16. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12944.

- Muñoz, A. A., K. Klock-Barría, P. R. Sheppard, I. Aguilera-Betti, I. Toledo-Guerrero, D. A. Christie, T. Gorena, L. Gallardo, Á. González-Reyes, A. Lara, et al. 2019. Multidecadal environmental pollution in a mega-industrial area in central Chile registered by tree rings. Science of the Total Environment 696:133915. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.133915.

- Padisak, J. 1992. Seasonal succession of phytoplankton in a large shallow lake (Balaton, Hungary)—A dynamic approach to ecological memory, its possible role and mechanisms. The Journal of Ecology 80 (2):217–30. doi: 10.2307/2261008.

- Peterson, G. D. 2002. Contagious disturbance, ecological memory, and the emergence of landscape pattern. Ecosystems 5 (4):329–38. doi: 10.1007/s10021-001-0077-1.

- Pierre, S., and K. Palawat. 2021. Critical ecology demands an ongoing dialogue between social critique and environmental measurement. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of Geographers, Virtual, April 9, 2021.

- Purifoy, D. M. 2021. The plantation town: Race, resources, and the making of place. In The Routledge handbook of critical resource geography, ed. M. Himley, E. Havice, and G. Valdivia, 114–25. London and New York: Routledge.

- Reese, A. M. 2019. Black food geographies: Race, self-reliance, and food access in Washington, DC. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Reible, D. D., C. N. Haas, J. H. Pardue, and W. J. Walsh. 2006. Toxic and contaminant concerns generated by Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Environmental Engineering 132 (6):565–66. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9372(2006)132:6(565).

- Richter, D. J., and D. Markewitz. 2001. Understanding soil change: Soil sustainability over millennia, centuries, and decades. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Roane, J. T., and J. Hosbey. 2019. Mapping Black ecologies. Current Research in Digital History 2. doi: 10.31835/crdh.2019.05.

- Roman, L. A., H. Pearsall, T. S. Eisenman, T. M. Conway, R. T. Fahey, S. Landry, J. Vogt, N. S. van Doorn, J. M. Grove, D. H. Locke, et al. 2018. Human and biophysical legacies shape contemporary urban forests: A literature synthesis. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 31:157–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2018.03.004.

- Saint-Laurent, D., P. Duplessis, J. St-Laurent, and L. Lavoie. 2011. Reconstructing contamination events on riverbanks in southern Québec using dendrochronology and dendrochemical methods. Dendrochronologia 29 (1):31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.dendro.2010.08.005.

- Santella, N., L. J. Steinberg, and H. Sengul. 2010. Petroleum and hazardous material releases from industrial facilities associated with Hurricane Katrina. Risk Analysis: An Official Publication of the Society for Risk Analysis 30 (4):635–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01390.x.

- Sharpe, C. 2016. In the wake: On blackness and being. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Sharpe, C. 2018. And to survive. Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 22 (3):171–80. doi: 10.1215/07990537-7249304.

- Shaw, A. J. 1990. Heavy metal tolerance in plants: Evolutionary aspects. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Silva, L. C. R. 2015. From air to land: Understanding water resources through plant-based multidisciplinary research. Trends in Plant Science 20 (7):399–401. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.05.007.

- Spears, E. 2021. Reconceptualizing social vulnerability in Brunswick, Georgia: Critical physical geography and the future of sea-level rise. Southeastern Geographer 61 (4):357–80. doi: 10.1353/sgo.2021.0023.

- Sullivan, T. J. 2017. Air pollution and its impacts on U.S. National Parks 1st ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Tadaki, M., G. Brierley, M. Dickson, R. L. Heron, and J. Salmond. 2015. Cultivating critical practices in physical geography. The Geographical Journal 181 (2):160–71. doi: 10.1111/geoj.12082.

- Urban, M. A. 2018. In defense of crappy landscapes. In The Palgrave handbook of critical physical geography, ed. R. Lave, C. Biermann, and S. Lane, 49–66. Cham: Palgrave. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-71461-5_3.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 2010. Port Arthur, Texas Westside community environmental profile. Washington, DC: United States Environmental Protection Agency.

- Weinbaum, A. E. 2013. The afterlife of slavery and the problem of reproductive freedom. Social Text 31 (2):49–68. doi: 10.1215/01642472-2081121.

- Williams, B. 2021. “The fabric of our lives”?: Cotton, pesticides, and agrarian racial regimes in the U.S. South. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 111 (2):422–39. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2020.1775542.

- Willoughby-Herard, T. 2014. More expendable than slaves? Racial justice and the after-life of slavery. Politics, Groups, and Identities 2 (3):506–21. doi: 10.1080/21565503.2014.940544.

- Wilson, S., R. Richard, L. Joseph, and E. Williams. 2010. Climate change, environmental justice, and vulnerability: An exploratory spatial analysis. Environmental Justice 3 (1):13–19. doi: 10.1089/env.2009.0035.

- Winston, C. 2021. Maroon geographies. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 111 (7):2185–99. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2021.1894087.

- Woods, C. 1998. Development arrested: The blues and plantation power in the Mississippi Delta. London and New York: Verso.

- Woods, C. 2017. Development drowned and reborn: The blues and bourbon restorations in post-Katrina New Orleans. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

- Wright, W. J. 2019. The morphology of marronage. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 110 (4):1134–49.

- Wright, W. J. 2021. As above, so below: Anti-Black violence as environmental racism. Antipode 53 (3):791–809. doi: 10.1111/anti.12425.

- Wynter, S. 1971. Novel and history, plot and plantation. Savacou 5:95–102.

- Wynter, S. 1995. 1492: A new world view. In Race, discourse, and the origin of the Americas: A new world view, ed. V. L. Hyatt and R. Nettleford, 5–57. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Yusoff, K. 2018. A billion Black anthropocenes or none. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.