Abstract

Over the past several decades, craft brewing has altered physical and cultural landscapes across the United States as fermentation industries have increasingly been at the center of civic (re)development activities. Fermented landscapes are now ubiquitous, producing and maintaining a variety of public goods, whether perceived as beneficial or not. Some breweries offer highly visible examples of advocacy efforts, including the pursuit and promotion of environmental sustainability initiatives or profit-sharing to benefit various causes. It is unclear, however, how prevalent (or, alternatively, extraordinary) these kinds of activities are. Although craft breweries have been studied as agents of landscape change previously, they remain understudied as sociocultural actors that advocate for particular issues or outcomes. Thus, to better understand the kinds of advocacy that breweries pursue, we conducted a qualitatively informed quantitative analysis (including qualitative coding, descriptive statistics, and two analytical visualization techniques) on a random sample of 400 craft breweries in the United States. The resulting typology of advocacy in craft brewing identifies three dozen distinct techniques and approximately two dozen themes of action across three broad axes of advocacy, clarifying how breweries engage in environmental, social (justice), and economic initiatives in both active and passive ways.

在过去几十年中, 酿造产业成为地方(再)发展的核心行为, 手工啤酒酿造改变了美国的自然和文化景观。当前, 酿造景观无处不在, 创造和维系了各种公共商品。这种现象是否有益, 存在着不同的观点。本文将促进行为定义为:旨在造福各项事业的对环境可持续性和利益共享的追求和促进。某些啤酒厂是这种促进行为的例子。然而, 目前尚不了解这些促进行为的重要(或非同寻常)程度。目前的研究认为, 手工酿造啤酒厂是景观变化的推动者, 却忽视了它们对特定问题或结果的社会文化促进作用。为了更好地理解啤酒厂的促进作用, 我们随机选择了美国400家手工啤酒厂, 进行基于定性方法的定量分析(定性编码、描述性统计和两种解析性可视化技术)。本文认为, 手工酿造的促进行为涵盖了三类促进行为中的30种技术和约20种行动主题, 阐明了啤酒厂如何以主动和被动方式参与了环境、社会(正义)和经济举措。

Durante las últimas décadas, la elaboración artesanal de cerveza ha cambiado los paisajes físicos y culturales de los Estados Unidos en la medida en que las industrias de la fermentación cada vez más se sitúan en el centro de las actividades de (re)desarrollo cívico. Los paisajes de fermentación ahora son ubicuos, produciendo y manteniendo una variedad de bienes públicos, así se perciban como benéficos o no. Algunas cervecerías ofrecen ejemplos altamente visibles de actividades de promoción, que incluyen la búsqueda y el fomento de iniciativas de sostenibilidad ambiental, o compartiendo beneficios en favor de diversas causas. Sin embargo, no es claro en qué medida son frecuentes este tipo de actividades (o, alternativamente, extraordinarias). Si bien las cervecerías artesanales se han estudiado anteriormente como agentes de cambio del paisaje, siguen fuera de los esfuerzos de investigación como actores socioculturales que abogan por asuntos o resultados particulares. Entonces, para mejor entender los tipos de promoción que llevan a cabo las cervecerías, realizamos un análisis cuantitativo con información cualitativa (que incluía codificación cualitativa, estadística descriptiva y dos técnicas de visualización analítica) en una muestra aleatoria de 400 cervecerías artesanales en los Estados Unidos. La tipología resultante sobre favoritismo por la cerveza artesanal identifica tres docenas de técnicas distintas y aproximadamente dos docenas de temas de acción a través de tres amplios ejes de aprecio, aclarando cómo las cervecerías participan en iniciativas ambientales, sociales (justicia) y económicas, tanto de manera activa como pasiva.

Breweries have economic, sociocultural, and political significance at a variety of scales and are increasingly interwoven in the economy and culture of diverse locales in the twenty-first century. Inspired by salient, anecdotal examples of advocacy—including the ones referred to in our titleFootnote1—we seek to empirically and systematically examine the roles that craft breweries play in their communities, shaping places beyond merely producing beer. We assess craft breweries’ stated advocacy efforts, as represented via the images and text provided on their Web sites, to determine whether notable, individual examples of advocacy are indicative (or not) of broader trends within the industry. Advocacy in this study refers to explicit efforts to enact or influence specific, identifiable environmental, social, or economic issues—as (re)presented by breweries in their public-facing digital domains.Footnote2

Although the beer industry—especially the craft beer industry—has suffered amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, beer still plays a major role in the U.S. economy and in society more broadly. Although craft brew sales in the United States were down 9.3 percent by volume in 2020 (compared to the previous year; overall sales by volume were down 2.9 percent), the craft beer segment still accounted for 12.3 percent of the market by volume, bringing in $22.2 billion in retail sales, a 24 percent share of the overall beer market by sales (Brewers Association Citation2021a, Citation2021b). From 2020 to 2021, craft beer sales rebounded 7.9 percent and reached 13.1 percent of the total market by volume, as the overall beer market grew by 1 percent in volume. In dollar terms, craft retail value grew 21 percent from 2020, due, in part, to shifts back toward on-site consumption in taprooms as COVID-related restrictions evolved (Brewers Association Citation2022). Per the most recent reports available, retail dollar sales of craft beer account for just under 27 percent of the $100.2 billion U.S. beer market (Brewers Association Citation2022). As has been the case since the 1980s, the number of craft breweries continues to grow, indicating that these social and economic players are not waning in importance soon (Brewers Association Citation2021a). The Brewers Association counted 9,247 craft breweries in 2021, up from 1,545 in 2001, a 499 percent increase in twenty years (Brewers Association Citation2022).Footnote3

Production statistics aside, municipalities and developers alike are recognizing the numerous, auxiliary effects of beer production and sales on both urban and rural locales—including scenarios wherein they promote redevelopment and community building or, sometimes, accompany gentrification and exclusion (Myles and Breen Citation2018; Myles, Holtkamp, et al. Citation2020). Breweries are highly visible social actors, serving as pseudo-public spaces that propel and harness neolocalism (Holtkamp et al. Citation2016). Importantly, some breweries offer highly visible examples of advocacy, including the pursuit and promotion of environmental sustainability initiatives or profit-sharing to benefit various causes.

The practices and activities of breweries reflect contemporary social, environmental, and economic issues and perspectives. As such, in addition to effecting economic impacts, breweries represent prosocial and proenvironmental stances. These include promoting gender equity, public health, housing the houseless, closing educational gaps, or contributing to (or leading) environmental conservation and restoration efforts. Especially in local markets, such support for charitable causes might garner attention and publicity. Breweries clearly and visibly support myriad causes: A quick Internet search is sufficient to reveal numerous and diverse advocacy efforts undertaken across the United States in recent years.

The causes selected by breweries and the marketing campaigns developed to support them span a broad range of social and environmental issues, and often instances of advocacy do not neatly fit within either social, environmental, or economic categories. Each of these operational choices demonstrate breweries’ priorities and values and serve to connect them to their communities, patrons, and physical environment. In other words, breweries’ advocacy efforts reveal them as geographical agents. What is as yet unclear, however, is how prevalent—or, alternatively, extraordinary—these kinds of activities are. Craft breweries have been studied as agents of landscape change previously (Fletchall Citation2016; A. A. Watson Citation2016; Barajas, Boeing, and Wartell Citation2017; Gatrell, Reid, and Steiger Citation2018; Myles Citation2020), but they remain understudied as sociocultural actors that advocate for particular issues or outcomes.

Purpose and Research Questions

Curious about what particular issues breweries demonstrably care about and how they act on those concerns, we hypothesize that breweries use a suite of techniques, spread unevenly among an array of axes and themes, to advocate for social, economic, and environmental issues. Through these actions, they attempt to build strong(er) local communities or connections to place, even to the extent of coconstituting the economic and cultural landscapes they inhabit. Despite a large and growing literature on (the geography of) beer, however, craft breweries remain understudied as sociocultural actors that advocate for particular environmental or social outcomes. As such, we seek to better understand breweries’ contributions to local economies and communities through their advocacy efforts, at least insofar as such actions were reported via their Web sites. Defining advocacy broadly as the ways breweries support economic, environmental, or social causes or otherwise promote equity or justice, we set out to trace the connections between breweries and their respective communities by asking several broad, exploratory questions:

What kinds of advocacy themes, topics, or techniques do breweries in the United States pursue?

What dimensions and patterns of advocacy in brewing are apparent?

How prevalent (or, alternatively, extraordinary) are these kinds of activities?

In this article we detail the axes–themes–techniques typology we developed to better understand the diversity of breweries’ advocacy efforts as well as the results of our various analytical visualization efforts. As we present our specific findings, we identify both the extraordinary and more commonplace (or prevalent) advocacy efforts in the craft brewing industry and paint a picture of the multidimensional landscape of advocacy in brewing.

Background and Literature Review

Geographies of Beer and Fermented Landscapes

As the craft beer industry continues to develop (Kline, Slocum, and Cavaliere Citation2017) and consumers (re)discover the health and community benefits of localized fermented foods (Sarmiento Citation2020), interest in the connections between production, consumption, and distribution of craft beer has grown (Patterson and Hoalst-Pullen Citation2014; Hoalst-Pullen and Patterson Citation2020). Within the body of beer geography literature, studies vary widely in topic, scope, geographic location, and methodology. One prominent trend in (craft) beer research is the examination of breweries’ relationship to place, identity, and culture (Reid, Pezzi, and Stack Citation2020). Other topics of interest have included the consolidation of breweries into large corporate conglomerates (Howard Citation2014), socioeconomic implications of alternative producer proliferation and differentiation (Kline, Slocum, and Cavaliere Citation2017), the rapid growth of the craft brewing segment of the beer industry (McLaughlin, Reid, and Moore Citation2014; Withers Citation2017), and craft brewing’s impacts on economy and environment (Reid and Gatrell Citation2017). In line with a broader disciplinary turn toward “the digital” (Ash, Kitchin, and Leszczynski Citation2018), geographic research methodologies and foci are increasingly tuned to examine the virtual presence and footprint of (craft) beer—including analyses of brewery Web sites (A. J. Mathews and Patton Citation2016), crowdsourced social media (Zook and Poorthuis Citation2014; Myles, Holtkamp, et al. Citation2020), and online beer communities (Chapman, Lellock, and Lippard Citation2017; Savelyev et al. Citation2019).

This sustained, growing scholarly interest is justified in part because artisanal fermentation industries—like craft brewing—have altered landscapes across the United States and the world (Slocum, Kline, and Cavaliere Citation2018; Myles Citation2020). Urban renewal and gentrification have marched hand-in-hand as metropolitan and suburban locales have encouraged the establishment of craft fermenters as a component of their economic and community development strategies. Fermented landscapes (Myles Citation2020) are now ubiquitous and constitute a variety of (micro)movements (Myles and Breen Citation2018), which can produce and maintain an assortment of public goods, whether they are perceived as beneficial or not (Myles, Holtkamp, et al. Citation2020). Indeed, breweries are simultaneously called—and claim—to be spaces of community and belonging (Schnell and Reese Citation2014) even as they are also potentially exclusionary settings (V. Mathews and Picton Citation2014).

Diversity (or Lack Thereof) in Craft Brewing

At least two studies have used qualitative content analysis to examine social justice issues in U.S. craft beer culture. A. J. Mathews and Patton (Citation2016) conducted a content analysis of 1,564 brewery Web sites; their study revealed that neolocal narratives often focus on White male perspectives and might hinder racial diversity in brewery spaces. Using a discursive content analysis of online beer community threads, Chapman et al. (Citation2018) found examples of sexism in both production and consumption of craft beer, including comments about beer styles perceived to be preferred by males or females and the appearance of female brewers. Yet, their study also noted that some participants in these discussions were attempting to undo the gendered nature of beer through their discourse (Chapman et al. Citation2018). Aside from these studies, anecdotal evidence about breweries’ prosocial actions remains more readily available than empirical data.

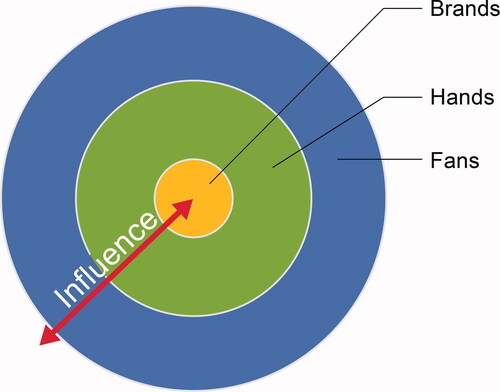

Despite this small presence in the academic literature, the craft beer industry is starting to acknowledge that its culture could benefit from greater advocacy and diversity. In 2019, the Brewers Association published an initial diversity study, concluding that various improvements could be made among the members surveyed (B. Watson Citation2019). Since then, the Brewers Association has invested in diversity grants and established best practices for diversity and inclusion (Brewers Association Citation2021c). For instance, the group’s diversity and inclusion best practices include guidelines for creating diverse branding and working with local “beyond beer” organizations, such as nonprofits (Jackson-Beckham Citation2019). Specifically, Jackson-Beckham (Citation2019) suggested taking a “fans, hands, brands” approach, wherein breweries target diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) goals along several dimensions: their fans (or consumers), hands (or employees), and brands.

In the fans, hands, brands model, brands refer to the “messages, images, and activities that shape your customers’ perceptions of your product and your organization … [including] your marketing and events, packaging and signage, [and] social media presence” (Jackson-Beckham Citation2019, 4). This emphasis on the public face of a brewery is especially relevant for our study, as we analyze images and text volunteered by breweries via their Web sites. Jackson-Beckham’s work suggests that although brand or marketing techniques have a predominantly internal benefit to the brewery—helping to serve and accomplish diversity goals—farther reaching and more tangible, local benefits can result from working with community-based organizations, as breweries extend their effort from brands to hands and fans. Given the potential for varying impacts among different activities, Jackson-Beckham (Citation2019) specifically advocated for additional research and study on this topic, as such data would be useful for creating a “responsibility structure” to potentially transform the craft beer industry.

To achieve diversity and inclusion goals and to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of existing efforts, breweries and their supporters first need to know what is currently being done. As noted earlier, little academic research has focused on what craft breweries advocate for and how they do it. Thus, this article seeks to quantitatively and qualitatively inform craft brewers and geographers of the most ubiquitous and extraordinary advocacy themes and techniques in the craft beer industry in the United States.

Theoretical Framework

The causes breweries advocate for and the mechanisms through which they conduct advocacy convey meaning and signal priorities (Jackson-Beckham Citation2019). Promotional and informational content shared by breweries via their Internet presence provides insights into those causes and mechanisms in the form of textual and image data that can be studied empirically, but brewery Web sites have not yet been systematically investigated in terms of prosocial or proenvironmental advocacy efforts. We approach these sites as a veritable treasure trove of voluntary data. To make sense of this information, we conducted an exploratory analysis of craft brewery Web sites to understand the themes and forms of their advocacy, an increasingly common element of brewery operations.

This research is political-ecological in nature, conceptualizing breweries as social agents with economic and political power to create social or environmental change. Political ecology (PE) foregrounds connections between political, economic, social, and environmental issues, offering methods to critique and expose disparate impacts and benefits while advancing ideas and action regarding the mitigation of those inequities (Robbins Citation2012). We recognize that, far from being apolitical, breweries’ decisions about advocacy (or lack thereof) shape the craft beer “landscape” and the landscape writ large.

It is worth noting that breweries are not monoliths, but rather are actors composed of other actors—brewers, yeast, grist mills, bacteria, water, and packaging machinery, to name a few. In engaging in advocacy, breweries as corporate entities intersect with their staff, patrons, yeast cultures, electrons in fiber-optic cables, Web servers, local organizations, social media networks, nation- and global-scale movements, product designers, and more. Although the primary focus of this article is not to trace these assemblages rigorously, the networks suggested by them are relevant to the typology of advocacy that emerges from our empirical analysis. As a result, actor-network theory (ANT; Law Citation2009) informs our ontological approach to the material-semiotic nature of breweries’ advocacy efforts.

Namely, by rejecting dualistic categorizations and a priori assumptions, we are freed to follow the data along the ant-like tunnels of the assemblage (agencement; Latour Citation2005). ANT is adamantly empirical, making it well-suited to explore new areas of research, especially on topics that are currently undertheorized. Combining the critical lens of political ecology with ANT, we seek to bridge and account for the various actors—human and nonhuman, digital and analog—that comprise advocacy in the craft brewing industry. Understanding brewery-driven advocacy as a complex and interrelated phenomenon that envelops various actors—human and nonhuman—in mutable networks of relationships, we situate our work at the nexus of these approaches.

In our analysis of the dimensions and patterns of advocacy in brewing (whether extraordinary or ubiquitous), we experimented with several forms of network analysis and data visualization, including network diagramming and graphical mapping techniques. Network diagramming is an established technique to quantify and visualize complex spatial and social relationships (Vinciguerra, Frenken, and Valente Citation2010; Fletcher et al. Citation2013). Network analysis is useful for discovering patterns and interactions that highlight areas of isolation, interrelation, and concentration (Giordano and Cole Citation2011). Graphical mapping techniques can be used to demonstrate the relational motors between various phenomena, as shown (for example) via studies focused on neolocalism and sustainability (Buratti and Hagelman Citation2021) and in (re)conceptualizations of “strong” sustainability more broadly (Ghavampour and Vale Citation2019). We applied these various analytical visualization techniques in our study in hopes of illustrating the contours of the relational network within and among material-semiotic advocacy agents in craft brewing in the United States.

Method

Research design and data collection for this study was conducted over the course of more than a year, with analysis and writing spanning another. Following the threads of anecdotal advocacy evident among breweries, we proceeded through several phases of research in an iterative fashion: inductively collecting evidence of advocacy, developing a pilot study to assess project feasibility, applying preliminary results to a new sample, and recoding and reanalyzing our data to compile a typology of advocacy. The decision to work iteratively, allowing the data to guide our direction, was a purposeful decision informed by ANT.

Through this exploratory approach, the research progressed through several phases:

Phase 1: A nonsystematic, “eyeball” inductive review of craft brewery Web sites to find evidence that breweries advocate for social, environmental, and economic issues.

Anecdotally, we knew that such efforts existed, but we wanted to determine to what extent breweries made these efforts public and how to characterize them.

Phase 2: A pilot study of 300 randomly selectedFootnote4 craft breweryFootnote5 Web sitesFootnote6 to test if the trends we saw via a nonsystematic survey of Web sites were replicable in a quantitative way.

In this phase we drafted a rough typology of advocacy and an evaluation matrix based on a “topic, theme, technique” framework.

As we gained a clearer view of the relatively more common and relatively more extraordinary forms of advocacy, though, we clarified our “axes of advocacy” (replacing the term “topic” in our typology).

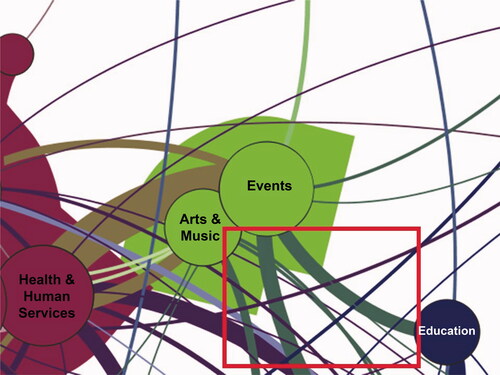

Through our processes of iterative analysis, we began to understand that advocacy in craft brewing is multidimensional (), an insight we further refined in Phase 4.

Phase 3: A second analysis on a fresh, random sample of 400 brewery Web sitesFootnote7 to test the utility and veracity of our evaluation matrix “in the wild,” against a new set of Web sites.

During this phase, we captured and coded photographs, textual descriptions, label art, and product names using our axis, theme, and technique typology.

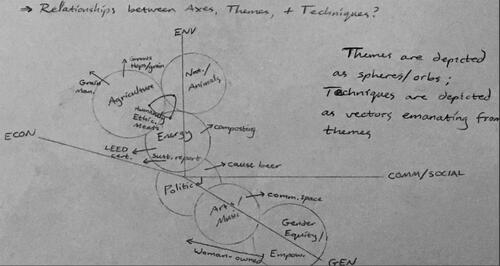

shows a snippet of a brewery Web site and provides labeled examples of how such a Web site would be coded in practice using our evaluation matrix.

Any and every relevant axis, theme, or technique for a given “instance” of advocacy was recorded.

For example, if a brewery organized or hosted an event that supported a cause that was both economically and socially related, two entries were recorded for the single event to capture the nuances of the advocacy effort.

Phase 4: Applying analytical visualization techniques to illustrate the overall advocacy landscape, including constructing a network diagram using an Atlas Force 2 algorithm in Gephi and creating a graphical concept map.

Gephi’s dynamic diagramming application simulates a physical system in which nodes repel, like magnets, and connections attract, like springs (Alarcón, Alarcón, and Alarcón Citation2013).

Several variables, including node size, edge length and thickness, modularity, and average clustering coefficient were analyzed to identify the most common and extraordinary theme–technique relationships along each axis.

The graphical concept mapping helped us synthesize the various components of the advocacy landscape to understand the dynamics and drivers present in the network.

Figure 1 Excerpt from an early concept sketch of the multidimensional space of advocacy in brewing, with themes and techniques arrayed along the axes of economic, environmental, community/social, and gender.

Figure 2 Snapshots illustrating how snippets from three brewery Web sites were coded using our evaluation matrix. (A) An example from Fort George Brewery highlights key phrases and images used for analysis, including the pie charts, which were categorized as a form of active tracking and reporting. (B) Sawtooth Brewery invoked montane and forest landscapes in its label art, a passive approach to promoting nature through representations. (C) Similarly, Stickman Brews championed democratic participation through its label design.

Considerations and Early Insights

As is typical of the tensions apparent in a qualitatively informed quantitative analysis (Savelyev et al. Citation2019), we struggled on occasion with situations wherein we knew that a particular technique was being used by a specific brewery, but that particular technique did not show up in our sample (e.g., due to a given brewery not being included in the sample). The decision to either include or exclude a known technique if it did not appear in our sample was a challenging one; given that we wanted the evaluation matrix to be built on empirical evidence, we ultimately decided against including such techniques in these instances. One way we responded to this challenge was (in addition to explicitly including a host of visible, empirically apparent themes and techniques) including an “other” option to capture anything that had not yet been categorized.

Similarly, we devised our next steps in dialogue with real-world conditions. For example, we chose a larger sample in Phase 3 for several reasons, including the desire to maintain a representative sample of the populationFootnote8 and to ensure statistical validity at the 95 percent confidence level. We also wanted to account for the fact that the number of breweries, both in the directory and “on the ground,” in the United States had increased since our first sample, as it has year after year since the early 1980s (brewersassociation.org). In addition, we wanted to provide a cushion in the likely scenario that a number of entries needed to be eliminated from the study due to Web site availability, as had been necessary during the pilot study conducted in Phase 2. Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic instigated impossible-to-ignore social and economic changes in the United States, and we were cognizant that some of these social and economic pressures had forced many breweries to alter their operations or shut down since our first sample.

Another specific real-time change involved modifying our initial evaluation matrix (designed in Phase 2), which assigned numeric scores to specific advocacy techniques. We ultimately set aside that model following many coding iterations because we determined that some advocacy techniques were difficult to “weight” in this way, given the limited information at our disposal. In addition, numerous advocacy efforts overlapped or did not neatly fit into our typology, despite its iterative refinement. Finally, the quantity of instances of advocacy varied greatly by brewery, making direct, numerical comparisons between them both unwieldy and not especially illuminating. As a result, in Phase 3, we gravitated toward sorting instances of advocacy into the binary categories of “active” and “passive” to capture differences in terms of effort or cost required to enact a given instance of advocacy.

This active or passive determination helped to further specify our codes insofar as it helped assess the tangible effort expended, such as the outlay of financial capital, time spent on planning, staff labor required, or the application of other resources necessary to achieve an objective. Finding the (at times fine) line between active or passive modes of advocacy was often a difficult and subjective process—especially given that our determinations were by design based only on information posted publicly on brewery Web sites. For example, the technique GMO free/gluten free could be applied to a brewery with a single gluten-free beer on the menu or to a brewery whose entire line of beer is gluten-free. In the first case, the label GMO free/gluten free would be considered an instance of passive advocacy because it represents a relatively small part of the brewery’s production or operations; in the second, it would be considered active because gluten-free beer is key to the brewery’s overall business model. This adaptation in our approach enabled a finer-grained analysis, even if it was not as nuanced as we had originally hoped.

Findings: The Dimensions of Advocacy in Brewing

Our data and analysis provide a means to characterize and understand the landscape of advocacy in craft brewing and how breweries serve as sociocultural actors that engage in environmental, social, and economic forms of advocacy. Our results are twofold, offering insights into brewery advocacy as well as serving as a proof of concept for a methodological approach to qualitatively informed quantitative analysis. In this section we describe the results from each of our various analyses—whether quantitative, qualitative, conceptual, empirical, or some combination thereof—each of which provided unique insights and possessed its own inherent challenges and limitations.

Our analyses were iterative and cumulative and resulted in a number of distinct findings and outputs, including the axes, themes, technique framework itself, the resulting typology of advocacy in brewing (including a still-in-development evaluation matrix for the treasure trove of Web site data), and an analysis of the most prevalent topics and tools used to advocate for specific causes. These findings allowed us to trace some contours of the landscape of advocacy in brewing vis-à-vis two different analytical visualization efforts: a network diagram of the advocacy components and a graphical concept map of the axis, theme, technique framework and its dynamics.

A Typology of Advocacy in Brewing: Axes, Themes, and Techniques

At its core, this study was driven by an open-ended, exploratory question: What kinds of advocacy themes, topics, or techniques do breweries in the United States pursue? Our initial analytical efforts focused on discovering what is happening with advocacy in brewing, who is doing it, where it is occurring, and how it is being enacted. Through an iterative and systematic process of inductively coding brewery Web sites, we investigated and documented the breadth of advocacy across craft brewing in the United States, ultimately constructing a typology of advocacy. This semihierarchical typology consists of axes, themes, and techniques used to identify and measure individual breweries’ advocacy efforts. Axes organize the broad advocacy topics uncovered in the study at the highest conceptual level. Themes further specify particular foci of advocacy within each axis. Techniques describe specific advocacy-related actions that address one or more themes. As a particular instance of advocacy might overlap several themes or axes, discrete classification was difficult at times.

Our initial round of data collection and analysis uncovered thirty-five distinct techniques and seventeen themes along four broad axes of advocacy: environmental, social, economic, and gender. This first-go analysis captured 95 percent of the themes and techniques present in the second sample; however, there were a handful of themes and techniques that proved to be hard to specify using this initial set. Therefore, prior to conducting a second analysis, we modified, added, removed, collapsed, expanded, and rearranged themes and techniques as needed over the course of ten collaborative research meetings. In the end, we decided on a revised evaluation matrix that included no new techniques, five new themes, and an “other” designation to capture instances that remained difficult to categorize. We also decided to collapse the once-independent axis of gender into the social axis due to its lack of prominence (see Wiley and Myles Citation2021), leaving just three axes of advocacy:

Environmental, having to do with any environmental efforts or issues.

Social, related to the promotion of community or individual well-being.

Economic, oriented toward financial or monetary goals or outcomes, ranging from issues related to employee benefits to profit sharing.

The finalized typology of advocacy in brewing is outlined in the Appendix and includes thirty-five distinct techniques (as well as an option for “other”), twenty-two distinct themes (plus the option for “other”), and three axes. Whereas many of these themes explicitly connect to a particular axis (e.g., LGBTQ inclusivity clearly fits within the social axis), others, like agriculture & horticulture, or general local charity exhibit aspects of multiple axes (in this case, environmental, economic, and social). At the heart of our typology are thirty-six distinct techniques or actions related to advocacy. These techniques range from very basic (e.g., Website text) to particularly demanding in terms of effort (e.g., 100 percent of profits donated). As is the case with other parts of this nested typology, some techniques of advocacy might fit neatly within certain themes, and others could bridge multiple themes and axes.

Patterns of Advocacy: Exploring the Prevalent and the Extraordinary

In addition to our basic query regarding what kinds of advocacy breweries conduct, we also wanted to get a sense of the relative (un)commonness of various causes and techniques. To do this, we used descriptive statistics to classify the instances of advocacy in our sample by axis, theme, and technique. We learned that the typology of advocacy in brewing, and the analyses used to create it, are well suited to measuring the (in)frequency of advocacy, but are rather poor at measuring their intensity or impact,Footnote9 so we devised a (relatively) simple tool to weigh (in some form) the intensity of particular advocacy actions depending on the perceived effort required or reported resources expended to implement them.

Using our collective expertise, we made (subjective, informed) decisions about each of the instances in front of us. When the instances of advocacy were divided into passive and active groups, there were 568 instances of active advocacy (46 percent) and 679 instances of passive advocacy (54 percent). We conducted descriptive, statistical analysis on the coded data set (our sample of 400 breweries) using our typology alongside the passive versus active refinement tool, with the following results.

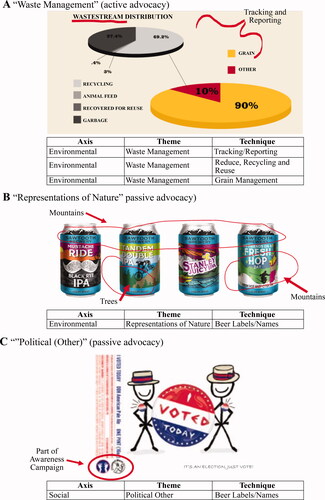

Axes of Advocacy: What Kinds of Issues Do Breweries Engage with? Advocacy for social causes was most prevalent (comprising 56 percent of the total instances of advocacy observed), followed by environmental causes (41 percent of the total instances), with economic advocacy efforts being the least represented (just 3 percent of the instances of advocacy observed). A brewery’s efforts often fell along more than one axis of advocacy, however; in other words, breweries participating in advocacy seemed to do so on multiple fronts (axes). Eighty-five percent of economic advocacy was active, approximately one-third of environmental advocacy was active, and social advocacy was split fairly evenly. Therefore, depending on the axis an instance of advocacy aligns to, a brewery is more likely to use active or passive approaches.

In terms of the count of breweries engaging in advocacy in comparison to the counts of instances of advocacy, the instances of economic advocacy and the number of breweries engaging in it are roughly the same (). There were about twice as many instances of environmental advocacy present versus the number of breweries doing that work, however, and three times as many instances of social advocacy as compared to the number of breweries conducting the advocacy actions. The incongruity between instances of advocacy and number of breweries doing them indicates that some breweries are more active than others, an insight (further) borne out by the fact that sixty-four breweries (16.50 percent of the total sample) did not show any instances of advocacy at all. This could be because no instances were present on the Web site (8.75 percent of the total), no Web site existed (7.00 percent of the total), the Web site did not mention beer at all (0.20 percent of the total), or the brewery had closed permanently (0.50 percent of the total).

Figure 3 Frequency of instances of advocacy and distinct count of breweries engaging in advocacy by axis (economic, environmental, and social).

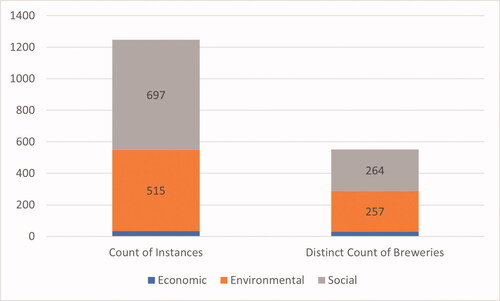

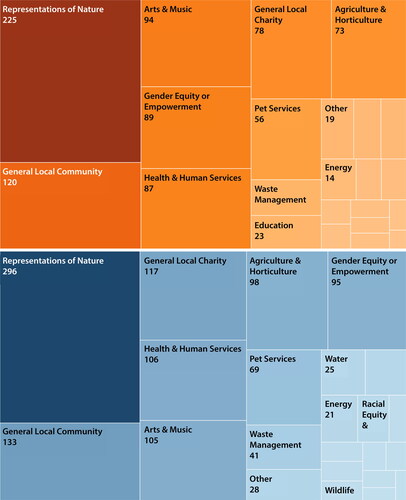

Themes: What Specific Issues Do Craft Breweries (Try to) Act on? Taken together, breweries advocate for a wide range of themes, but the majority of them engage with a narrower set of advocacy issues. displays the frequency counts of advocacy themes by instance and by the number of distinct breweries using them and demonstrates how advocacy efforts tend to cluster around certain topics or themes.

Figure 4 Frequency graphic representing the instances of advocacy (bottom) and distinct count of breweries (top) engaging in advocacy by each theme.

Overall, the most common themes by count of instances also had the largest number of breweries engaged with them. The top three themes were representations of nature, general local community, and general local charity, which accounted for 44 percent of the total instances of advocacy. Furthermore, the incongruity between the number of instances of advocacy and number of breweries employing a specific theme persisted across approximately 75 percent of all themes in the typology, indicating that breweries will use multiple forms of engagement for a single theme. Representations of nature and general local charity have the largest difference between the number of breweries engaged and quantity of relevant instances, with the former having about a third more instances compared to breweries using that theme and the latter having twice as many instances compared to breweries. The more extraordinary themes involved wildlife conservation, transportation, sustainable building, public spaces, LBGTQ +inclusivity, hunger, homelessness, first responders, frontline workers, and other political causes regardless of active or passive.

(top) shows the most common active themes involved working with different local charities, artists, musicians, and health and human services organizations as well as supporting local or sustainable food networks. Passive themes were concentrated into a smaller set, with the majority related to branding maneuvers that highlighted the brewery’s connection to the physical, natural landscape (representations of nature) and the local community (, bottom). Most gender advocacy was also passive, appearing mainly via a brewery having a female owner (or, more often, co-owner) who was mentioned or pictured on an About Us Web page.Footnote10

Figure 5 Frequency graphic representing the instances of advocacy (blue) and distinct count of breweries (orange) sorted by theme, with both active (top) and passive (bottom) designations shown.

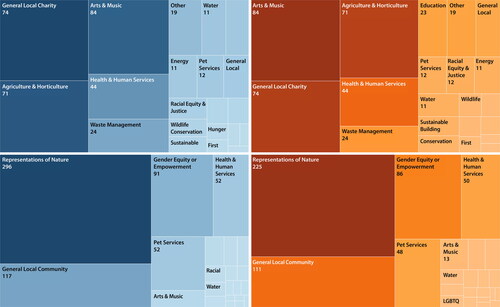

Techniques: What Tangible Activities Are (Re)Presented on Brewery Web Sites? The techniques in our typology yielded similar results. The majority of advocacy actions breweries engage with are concentrated in a narrow set of techniques; however, it is clear that a multitude of techniques are being utilized. shows that only 44 percent of the total instances are captured by the top three techniques (events, monetary donation, and sources local/sustainably), compared to 75 percent of instances captured by the top three themes. The same incongruity between instances of advocacy and number of participating breweries apparent elsewhere also appeared in our analysis of brewery advocacy techniques, demonstrating that breweries often employ more than one technique in service to their advocacy and outreach goals. The more extraordinary techniques involved operating a 501(c)(3), composting, renewable energy generation, GMO or gluten-free ingredients, humanely and ethically raised animals, female ownership, extensive recycling, and self-reporting.

Figure 6 Frequency graphic representing the instances of advocacy (top) and distinct count of breweries (bottom) by each technique.

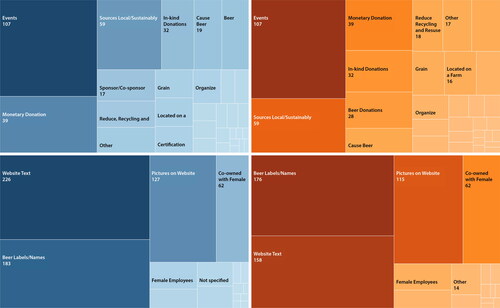

Similar to the split within axes and themes, when we parsed techniques as passive and active, a discrepancy emerged (). The most common active techniques involved event partnership and monetary donation. The most common passive advocacy behavior related more closely to semiotics and discourse via branding and marketing, either in Web site text or on beer label art and names. Passive advocacy also included sourcing from and supporting local or sustainable food networks. In short, the majority of instances of advocacy were concentrated in several top themes and techniques, a phenomenon that was even more apparent when subcategorizing as active or passive.

Figure 7 Frequency graphic representing the instances of advocacy (blue) and distinct count of breweries (orange) sorted by technique, with both active (top) and passive (bottom) designations shown.

A weakness of this kind of frequency analysis is the necessity to use arbitrary cutoffs (e.g., between “extraordinary” or “prevalent” techniques), which inserts subjectivity into the analysis, even when based on natural breaks in the data. This kind of statistical frequency analysis also does not facilitate an exploration of the interactions between themes and techniques, especially among those that are less common, of which there were many. Because our analysis made clear that the frequency of advocacy instances is not normally distributed, we moved toward other, nonparametric analytical approaches to try to encapsulate the interactions between axes, themes, and techniques, including network analysis via analytical visualization techniques. The visualization efforts that followed were aimed at clarifying the multidimensional landscape of advocacy that we had begun to formulate early on.Footnote11

Painting a Picture: Surveying Landscapes of Advocacy in Brewing

As we developed our typology of advocacy, it became clear that there are complex relationships between the axes, themes, and techniques and that these dynamics and interrelations are discoverable, but less discernible, without the use of some form of network analysis to elucidate them. Thus, we experimented with different visualization techniques, including network diagramming and graphical concept mapping techniques, to facilitate the identification of connections and linkages between our variables. These network analyses enabled us to quantify and visualize the complex relationships and interrelated dynamics between various themes and techniques, helping to uncover patterns and model the overall “landscape” of advocacy in craft brewing in the United States.

Building on our early hand-drawn visualization efforts (), we used network diagramming tools to understand the connections between different techniques and themes of advocacy in our sample as we sought to determine which of the apparent topics and approaches were prevalent or extraordinary. As a practical matter, we deliberately pursued a more reductionist approach (compared to ANT) to take a snapshot of the spectrum of advocacy in brewing.

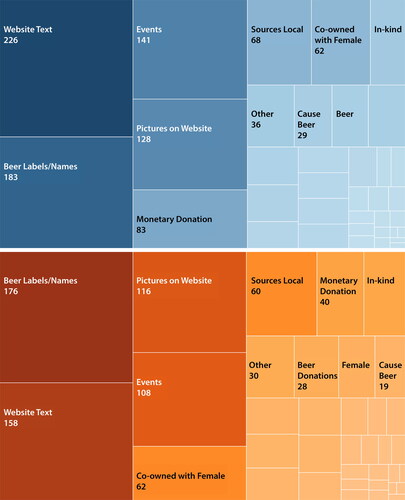

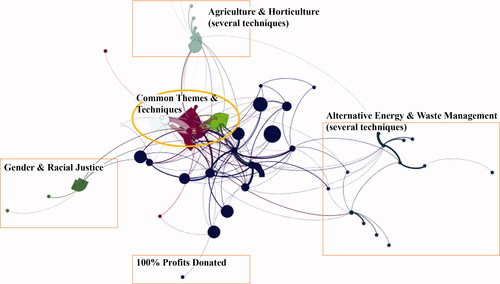

To help visualize the “topography” of advocacy evident from brewery Web sites, we used Gephi, an open-source tool for exploratory data and network analysis. Building a network diagram using Gephi (https://gephi.org/; see ) allowed us to create a rhizomatic (rather than hierarchical or linear) diagram, which better conveyed the myriad and interconnected ways that breweries advocate for social, environmental, and economic causes. These data visualizations offer a means to represent and analyze our empirical findings, helping identify patterns of isolation (denoting more extraordinary efforts) and concentration (indicating greater prevalence) and offering more nuanced ways to display the data than our initial (and more conceptual) hand-sketched diagrams.

Figure 8 A Gephi-derived network diagram displaying the linkages and connections between the various variables in the typology. Not all variables analyzed are labeled in this graphic because this view is zoomed out to show the entirety of the network.

This Gephi network diagram is an exploratory, explanatory representation of a complex network of phenomena. The diagram(s) created (see for one) are not meant to convey the entirety of the network or even the broader assemblage of advocacy in brewing; instead they offer a spatialized representation of our typology of advocacy. A key benefit of this technique is its capacity to (literally) illustrate the connectivity between themes and techniques, helping to validate (and triangulate) our typology, which was developed through qualitatively informed quantitative analysis (namely, coded Web site data and descriptive statistics).

reveals a tightly clustered nucleus with branching appendages that represent connected but less prevalent forms of advocacy.Footnote12 Prevalent themes and techniques are tightly bound together in the nucleus; those close in proximity (i.e., having a higher than average modularity) represent a strong, positive relationship between the variables. The distance between points (nodes) in the network indicates how connected various themes or techniques are to other themes or techniques. Each theme and technique in our topology of advocacy is represented by a node in the network diagram (although not all are pictured in ). The degree of connection between themes and techniques is based on the number of instances of a particular theme–technique combination in the data set. The relative distance between nodes signifies their degree of connectivity to other nodes, which represent both themes and techniques.Footnote13 The size of each node indicates the count of instances for that theme or technique, with larger circles representing larger counts.

In our sample, breweries used the same techniques for certain themes of advocacy almost two-thirds of the time. Despite frequent connections between certain themes and techniques, craft breweries demonstrate a wide range of advocacy efforts, as illustrated by the network’s overall sprawling shape. This is further evidenced by the average clustering coefficient of this network diagram (0.12). In other words, an average node is connected to its neighbors 12 percent of the time. This level of modularity—the degree to which nodes within each cluster or “community” are linked to nodes in other “communities”—indicates less dense connections between different techniques of advocacy, pointing toward the diversity in the overall landscape of craft beer advocacy.

This modeling and visualization approach reveals a lot about our data. For example, in , the nucleus is indicated by a yellow ovalFootnote14 and includes a number of prevalent themes: arts and music, general local community, health and human services, pet services, and representations of nature, indicating their interconnection(s). Techniques inside the nucleus include beer label/names, events, pictures on Web site, and Web site text. Themes and techniques furthest away from the center (bounded by boxes) are the least connected to other themes and techniques in our sample; these are the more “extraordinary” ways of doing advocacy, in comparison to the more prevalent ones clustered closer to the center. This kind of visualization can also help reveal techniques that are not especially prevalent, but that are also common enough not to be extraordinary (GMO/gluten free being an instructive example).

Further, and importantly, a diagram like this also depicts significant connections between themes and techniques. For example, one salient insight gleaned from this diagram is that some less prevalent techniques tend to cluster together because they often relate to similar technique–theme combinations. For example, advocacy in the waste management and sustainable building themes typically occurs through the use of certain techniques (e.g., reduce, reuse, recycle or grain management). Conversely, sometimes a prevalent theme relates to many techniques. For example, the theme of water has connections to a host of other themes and techniques ranging from more common categories like alternative energy and waste management, health and human services, and representations of nature to the extraordinary, like 100 percent profits donated. This robust interconnectivity is not surprising given the importance of water to brewing and given findings derived from other portions of the analysis (namely the qualitative coding of the brewery Web site data). Network diagramming thus supports our quantitative findings by providing a spatialized visualization that (re)presents the empirical data and verifies its apparent connections and dynamics.

To further specify and define the implications of the patterns we found and to clarify the drivers and dynamics of this phenomenon, we developed a conceptual model to explain the apparent features of the advocacy landscape in craft brewing in the United States. Inspired by the “fans, hands, and brands” framework developed by Jackson-Beckham (Citation2019), our graphical conceptual map () depicts breweries’ spheres of influence as a nested set of categories of advocacy in brewing. Brands occupies the innermost ring of the map because the kinds of activities it represents often involve semiotic activities that are passive and mainly affect the brewery only. Hands makes up the middle ring because, although often passive, the impact of these kinds of activities also include employees, who move between their communities and workplaces. Fans makes up the outer ring because advocacy actions oriented toward customers and entities other than the brewery itself might have a greater overall potential impact. The first iteration of this model appeared in Wiley and Myles (Citation2021), which analyzes gender advocacy in brewing in particular. We have modified the map, however, based on our comprehensive analysis of brewery advocacy. Specifically, we updated it with a bidirectional arrow to account for the ways in which influence can flow from within the brewery outward into the community and vice versa, further clarifying the systemic dynamics of industry advocacy.

Figure 9 Graphical concept map of breweries’ spheres of influence. The spatial orientation of the three rings relates to the degree to which brands, hands, and fans have influence external to the brewery.

Although we see good alignment between the two network visualizations in some areas, it is clear that although both models are useful, both are also partial; neither perfectly captures the phenomenon on its own. The placement of the technique events offers an instructive example. Events is highly connected to the theme arts & music (which falls along the social axis) because support for the arts is often enacted through in-house events. Events, however, is also associated with many other categories in the sample, denoted by the thick lines flowing from its node (as shown in shades of green in ). Because events is a prevalent advocacy technique used by breweries, the node representing it is located close to the center of the network diagram, in the nucleus. On the concept map, though, events falls along the outer edge of the model because the technique has significant potential for influencing a wide array of actors (namely, fans). Taken at face value, these differences suggest contradiction, but in actuality, they help to elucidate the complexity of the advocacy landscape. Although the brands, hands, fans model was developed for DEI issues specifically (Jackson-Beckham Citation2019), our analysis demonstrates how the concept can be extended to an array of prosocial and proenvironmental activities that a brewery might choose to pursue. Taken together, the two network visualizations represent the data and dynamics apparent in our study, although they stop short of a truly three-dimensional model.

Discussion

In this study, we set out to answer three exploratory questions. We next discuss each of these questions in turn, summarizing key findings from our research.

What Kinds of Advocacy Themes, Topics, or Techniques Do Breweries in the United States Pursue?

The preceding analysis shows that craft breweries advocate for a range of issues and implement advocacy in many different ways. We constructed a typology of this advocacy using brewery Web sites, discerning three broad axes of advocacy (economic, environmental, and social) as well as twenty-two themes and thirty-five techniques (see the Appendix for a complete list). Our typology captures 98.5 percent of the themes and 97.2 percent of the techniques for all coded instances of advocacy in our second, representative sample. Even though we feel confident that our tool does what it is intended to, ideally future work on this topic would move beyond the voluntary (and potentially incomplete) data offered by brewery Web sites to better capture the motivations for and impacts of any given advocacy effort. Attempts to paint an even more nuanced picture of advocacy using these and other methods are already underway.

What Dimensions and Patterns of Advocacy in Brewing Are Apparent?

We undertook this exploratory study to investigate the topography or landscape of advocacy in craft brewing in the United States. As we learned more about the assemblage of actors and factors in this network of advocacy, we needed to find a way to analyze and visualize our findings to come to (any) conclusions. Thus, we employed two different analytical visualization techniques: network diagramming, to understand the connections and interrelations between themes and techniques, and graphical concept mapping, to gather and (re)present the overall dynamics of the advocacy landscape.

As described earlier, most of the nodes in the network diagram clustered around the nucleus, which represents the most prevalent forms of brewery advocacy. More extraordinary cases of advocacy appear as branching appendages connected to but further from the center. The forms of advocacy represented in the nucleus, whether themes or techniques, generally correspond to more passive advocacy efforts (e.g., Web site text or images of physical geographic features used on beer labels), and the appendages typically correspond to more active efforts (e.g., growing hops on site or pursuing gender equity or inclusion). Further refinement of the typology, however—specifically in the form of devising some measure of intensity or impact—would deepen the analyses possible with this tool. As such, our future efforts will be aimed (among other things) at the completion of an index-style evaluation matrix.

How Prevalent (or, Alternatively, Extraordinary) Are These Kinds of Activities?

In this study, using a dynamic and iterative qualitatively infomed quantitative analysis, we identified an array of themes and techniques that breweries use to advocate for social, environmental, and economic causes. Some themes and techniques are much more prevalent than others; for example, economic-focused advocacy in general is much less common than environmental or social advocacy. Likewise, implicit (passive) forms of advocacy including Web site text, images, and beer labels depicting representations of nature are more common than explicit appeals or efforts to promote causes. The former serve as semiotic markers of breweries’ priorities, even if there is a relative lack of time, money, or effort devoted to supporting them, whereas events and donations are the most prevalent active techniques employed by breweries.

Across the three broad axes of advocacy—social, environmental, and economic—some trends were apparent. For example, 43 percent of the breweries sampled engaged in some sort of social advocacy, which indicates an orientation toward the local community on the part of brewers. This aligns with both popular rhetoric and extant scholarship on craft brewing’s priorities. The breadth of the social axis is potentially problematic, though, suggesting that some elements of the typology merit further exploration. For instance, the theme health and human services includes advocacy efforts ranging from providing support and assistance to at-risk youth and those experiencing poverty to hosting fundraisers for health-focused nonprofits, representing a wide variety of topics that could be further differentiated.

Similarly, nearly a third of sampled breweries engaged in environmental advocacy. Much of the advocacy on this topic appeared as representations of nature in Web site images, label art, or beer names. Whether this level of engagement substantively reflects the values (e.g., recreational habits, political ideologies, beliefs about quality or sourcing) of the clientele, the owners of the establishments, both, or neither, is harder to discern. Although our evidence suggests that brewers often use environmentally focused language in appraising and promoting their beer, this axis could also benefit from more targeted investigation.

In terms of economic advocacy, very few breweries (just 1 percent of the sample) engaged in the direct donation of profits, despite “cause beer” as a highly visible example of brewery advocacy. In fact, in our analysis, cause beer did not even register as a form of economic advocacy. In our framework, economic advocacy involves alternatives to traditional for-profit business models (e.g., B-corp, nonprofit, or limited profit company) or provides benefits for their employees beyond what is typical (e.g., sponsoring green transportation programs or providing a universal living wage). The dearth of economic-focused advocacy might be a reflection of the already-tight margins under which most of these enterprises operate. In other words, despite good intentions, the tough economic realities for businesses like these could be a contributing factor to their lack of action or engagement with economic issues.

All in all, there is strong evidence that breweries are engaging in advocacy across a number of topics and themes via a variety of techniques. Some of these themes and techniques are relatively common, perhaps even ubiquitous, but there are a number of examples of extraordinary advocacy as well, including a brewery that donates all of its profits to social and environmental causes or breweries that make an explicit attempt to engender (so to speak) gender empowerment or inclusivity (a theme) via particular tactics (techniques), like having women in production (or operations or leadership) and female owners. The pursuit of alternative energy is another example of extraordinary advocacy, with just thirteen (out of 400) breweries in the sample exhibiting public-facing efforts to this end. Other extraordinary advocacy efforts include pursuing racial justice, providing explicit LGBTQ + allyship, or adopting charitable business models (e.g., seeking B-corp status or establishing 501(c)(3)s). In one notable case, Faubourg Brewing Company (formerly Dixie Brewing Company) in New Orleans took the extraordinary step of changing its name to reflect the role their brewery can play in “making our home more unified, welcoming and resilient for future generations’' (Faubourg Brewing Co. Citation2021).

Looking Forward, Looking Back

Even (or especially) with these extraordinary cases in mind, it seems there is opportunity for more profound change. For example, the relatively low percentage (just over 11 percent) of the sample engaging in gender-based advocacy could be a mirror to the fact that relatively few craft brewers are female. Women and other marginalized groups (including LGBTQ + communities) are underrepresented in the world of craft brewing, including among the brewery workforce. The current data provided by the Brewers Association indicates that 7.5 percent of head brewers are women and 2.0 percent of breweries are owned solely by women (B. Watson Citation2019). In short, large disparities remain between men and womenFootnote15 in the industry, and diversity and equity issues intersect. Thus, despite gains in terms of diversity and inclusion, the Brewers Association’s best practices have not (yet) permeated the industry at a level indicating real change. Whatever the reason for the overall lack of progress, it will require breweries to set specific goals in each area of the fans, hands, brands model to gain traction on these issues.

There is room for improvement in analyses like those presented here as well. For example, using Web sites as primary sources has the disadvantage of a lack of permanency, as links break, URLs change, and information goes out of date. Moreover, not all breweries are committed to having a comprehensive online presence, so the data available for review and analysis might be partial at best. Significantly, advocacy can be unpredictable and subject to spatial and temporal variation as breweries act in accordance with local circumstances and needs. A case in point is the COVID-19 pandemic. This research project was initiated prior to the pandemic and was ongoing during the (long-lasting) crisis. The pilot study sample was taken prior to the onset of COVID-19 restrictions, and the final sample was pulled during the pandemic. Breweries that had closed or did not have a Web site were not analyzed; thus, any breweries that closed due to COVID-19 were also excluded from the sample. More important to the substance of this research, though, the COVID-19 pandemic has clearly had a huge impact on all facets of economic and social life in the United States, including the craft brewing industry.Footnote16 As such, breweries’ advocacy efforts might have necessarily been relegated to the back burner, as many breweries are (perhaps even more than ever before) simply focused on staying afloat.

In addition, the dualistic categorization of passive versus active advocacy both created challenges and resolved others. A related, relevant element of future research on this topic will be determining how to measure the impact, intensity, or reach of the actions (reportedly) undertaken by breweries. This part of the research is ongoing, as we refine a more comprehensive matrix or index for qualifying and quantifying breweries’ advocacy efforts. So far, although the typology does clearly help us get to the who, what, where, and how of advocacy in brewing, this article focuses mainly on the what and the how. Future work will delve into these other dimensions. Moreover, the why remains elusive in this analysis and approach. We have begun to investigate this component via a smaller, regional study focused on the motivations and drivers for breweries’ advocacy efforts.

Despite these limitations, our typology successfully identifies the most prevalent axes, themes, and techniques comprising the landscape of advocacy in craft brewing in the United States—and pinpoints those breweries that are extraordinary advocates. We plan to share this research directly with the Brewers Association (and via other forms of public scholarship, as possible) to enable scholars and industry professionals to gain a better sense of the state of advocacy in craft brewing and inform decisions regarding where and how the biggest improvements might be made. Clearly, more work is needed to fully understand the nuances of these practices and patterns, but our findings and the tools introduced in this article provide a useful launching point for this work.

Conclusion

In this project we assessed and augmented anecdotal evidence about brewery-related advocacy to comprehensively explore the kinds of themes, topics, and techniques that craft breweries in the United States pursue. Using a political ecological and ANT-inspired approach, we created a typology of three axes, twenty-two themes, and thirty-five techniques that delineate various forms of advocacy (i.e., active vs. passive) and differentiate between more common and more extraordinary examples. This initial foray into craft breweries’ advocacy priorities and approaches uncovers (at least some of) the contours of industry activism at present.

We found that breweries coconstitute the economic and cultural landscapes they inhabit by advocating for larger social and environmental causes, possessing the potential to effect change within communities. These evolving, fermented landscapes are borne out by breweries’ actions and representations. Ascertaining the values and issues prioritized by breweries allows for a holistic view of the networks of businesses, raw materials, people, social media, nonprofits, Web sites, and images that comprise advocacy in brewing, as well as a means for discerning what else—or what more—can be done to address matters of concern. As Jackson-Beckham (Citation2019) noted, measuring and assessing action is crucial to enacting desired structural change. This emphasis on empirical evidence dovetails with ANT as an approach to understanding the complex webs encapsulated in the word advocacy.

Beyond our basic query regarding the kinds of advocacy that breweries conduct, we also explored the relative (un)commonness of various causes and techniques using descriptive statistics to classify the instances of advocacy in our sample by axis, theme, and technique. The connections between the themes and techniques identified in this study were vast and varied, although certain theme–technique relationships frequently emerged. Representations of nature were mainly visible as label art or depicted in Web site images. Web site text often alluded to supporting the local community. Gender-focused advocacy was most often seen in the form of a brewery being co-owned by men and women, with very few being owned by women alone. Charity to local nonprofits was usually apparent in the form of a monetary donation; however, in-kind donations—such as donating beer—also occurred in some locales. Advocacy for the environment was most often done by sourcing materials or ingredients locally or sustainably. Events (as possible in pandemic times) most often supported local artists and musicians. There were some extraordinary examples of advocacy, too, from forging a partnership with the local municipality to build hiking trails to donating backpacks full of everyday essentials for low socioeconomic status residents to operating on 100 percent renewable energy, to name a few.

As the terrain of brewery advocacy becomes more visible, new themes and techniques emerge, making it hard to create a one-size-fits-all tool. Additionally, there are inherent limitations to an approach that uses only reported actions via business Web sites (vs., e.g., observing actions or activities in person). In this project we analyzed these companies’ discourse through their online presence, which might or might not perfectly represent their day-to-day practices. Moreover, the craft brewing industry continues to grow and change, so it can be difficult to characterize it with precision at any given point in time. Still, the typology of advocacy and the attendant analytical network diagramming and graphical concept mapping presented here provide a way to visualize the complex assemblage between the (prevalent and extraordinary) themes and techniques of advocacy in the U.S. craft beer industry. In sum, this research establishes breweries as geographical agents that both respond to and enact cultural and environmental change, revealing the outreach priorities of craft breweries in the United States and underscoring the best practices for issue-based advocacy on the part of these social actors. Equipped with this insight, breweries can better align their values and actions moving forward.

Acknowledgments

This article was conceived prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and work on it began just as the public health crisis commenced. Thus, our efforts were stymied and delayed by numerous personal and workplace challenges. Nevertheless, our commitments to this topic pushed us forward despite the obstacles we faced. We want to acknowledge Dr. Bart Watson at the Brewers Association for sharing a comprehensive list of breweries from which we drew our sample. We also thank the numerous brewers and breweries that provided inspiration for this work through their work in their communities and fermentation tanks. We also appreciate the feedback provided by several anonymous reviewers, whose insights greatly improved the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Colleen C. Myles

COLLEEN C. MYLES is an Associate Professor in the Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Texas State University, San Marcos, TX 78666. E-mail: [email protected]. Her interests include political ecology, fermented landscapes (including the geography of wine, beer, cider, and spirits), and sustainability.

Delorean Wiley

DELOREAN WILEY is an Instructor of Record and PhD Candidate in the Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Texas State University, San Marcos, TX 78666. E-mail: [email protected]. Her research interests include social and environmental justice in fermented spaces, participatory action research, and material–human interactions.

Walter W. Furness

WALTER W. FURNESS is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Texas State University, San Marcos, TX 78666. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests include political ecologies of fermented foods, science and technology studies, and multispecies assemblages.

Katherine Sturdivant

KATHERINE STURDIVANT is a Master’s Candidate in the Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Texas State University, San Marcos, TX 78666. E-mail: [email protected]. Her research interests include environmental advocacy in craft brewing spaces and human–environment interactions.

Notes

1 Our title references two different brewery-driven advocacy efforts, one from a collective of craft brewers (Brewing Change Collaborative Citation2021) and one from the mega-brewer, Budweiser (Brewing Change Citation2021).

2 We recognize that breweries’ advocacy claims might be interpreted as a form of “greenwashing”—wherein businesses or entities undertake actions that look good but might be largely ineffective in terms of producing actual environmental change (Tufts and Milne Citation2015)—but this study, by design, did not attempt to measure breweries’ actual activities, only what they reported via their Web sites.

3 For those seeking to visualize this scale of change, the Brewers Association maintains a variety of publicly accessible statistics and charts that convey the state and status of the craft brewing industry in the United States. See https://www.brewersassociation.org/statistics-and-data/national-beer-stats/.

4 The sample was manually extracted from the Brewers Association member directory in October 2019 and then randomized in Microsoft Excel.

5 There was a broad range of businesses within our sample, from microbreweries to farms to pizza pubs that serve as restaurants as well as brewing beer. By far the most common type of business in the sample, though, was small microbreweries, which by definition have a limited production model and geographically constrained distribution range.

6 Breweries’ social media accounts were deliberately excluded from this study because of their uneven use and ephemeral time scales. Although it is also true that the scope of brewery Web sites can vary considerably, having a durable digital space (a Web site) that features (at least) basic information is a commercial standard.

7 This simple random sample was extracted from a database supplied by Brewers Associates in August 2020.

8 A comparison of the distribution by business type between our sample and the population verified that our simple random sample is representative.

9 We endeavored to solve this dilemma through the development (and aspirational application) of an evaluative matrix for the various themes and techniques brewers employed. The tool we created to do so, however, also (ironically) obscured more than it revealed because it necessitated focusing on the techniques breweries employed in their advocacy. So, for example, one brewery could use several techniques, each of which related to just one theme or axis, and, hypothetically, that brewery could score higher overall than a brewery that used three techniques, across five themes and all three axes. This kind of (potential) outcome seemed counter to the goal of the desired analysis, which was to determine the intensity of effort (or impact) across the spectrum of brewery activities. Thus, we discontinued the development and application of this analytical tool.

10 It is worth noting that existence of a female owner (or brewer) in itself is not a form of advocacy per se, but the purposeful visibility of a female owner or brewer is. In other words, if a brewery has female staff and chooses to highlight that fact, they are engaged in passive advocacy of the issue, at least as we have defined it here.

11 It is worth noting that even with the array of tools we applied to this task, we were still only able to conduct two-dimensional analyses, though the Gephi network diagram created a polarization that mimicked our conceptual sketches of axis interactions, which is the closest we came to a three-dimensional analysis for now.

12 There are other visualization tools available besides Gephi, each of which would have produced a differently styled output; we selected this due to its capacity to visualize connectivity, which was valuable to understanding and verifying our frequency findings and early hypotheses regarding network(ed) interconnections and dynamics in brewery advocacy.

13 The program we used for the analytical network diagram did not allow us to discriminate between themes and techniques, although that would have been preferable.

14 Because this tool allows the user to select the number of clustering “neighborhoods,” one natural consequence is that setting different parameters for this value necessarily (also) reorganizes the neighborhoods. Our selection was empirically driven, derived from the prior (quantitative) analyses conducted on the data.

15 A follow-up study by Wiley and Myles (Citation2021) examines this facet of advocacy in brewing in greater detail.

16 Although we decided against explicitly analyzing the impact of COVID-19 on craft breweries for this article, we did track the number of breweries that mentioned COVID-19 guidelines (eighty-two breweries), had pictures of people wearing masks (twenty breweries), and those that were closed permanently due to the pandemic (one brewery). Overall, this number had a negligible effect on the overall data set, and we ultimately decided to remove mentions of COVID-19 guidelines, reasoning that remarks about COVID-related restrictions were akin to a brewery noting their compliance with other legal and public health guidelines (e.g., ensuring visitors are of legal drinking age) and because COVID-19 restrictions would have applied to breweries whether or not breweries remarked on them or not. On the other hand, images of mask wearing, for example, were retained in the analysis because they demonstrated purposeful brewery action to promote and perform health and safety.

References

- Alarcón, D. M., I. M. Alarcón, and L. F. Alarcón. 2013. Social network analysis: A diagnostic tool for information flow in the AEC industry. In Proceedings for the 21st Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction, 947–56.

- Ash, J., R. Kitchin, and A. Leszczynski. 2018. Digital turn, digital geographies? Progress in Human Geography 42 (1):25–43. doi: 10.1177/0309132516664800.

- Barajas, J. M., G. Boeing, and J. Wartell. 2017. Neighborhood change, one pint at a time: The impact of local characteristics on craft breweries. In Untapped: Exploring the cultural dimensions of craft beer, ed. N. G. Chapman, J. S. Lellock, and C. D. Lippard, 155–76. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press.

- Brewers Association. 2021a. Annual craft brewing industry production report: 2020. Accessed February 25, 2021. https://www.brewersassociation.org/press-releases/2020-craft-brewing-industry-production-report/.

- Brewers Association. 2021b. Brewers Association releases annual growth report for 2019. Accessed August 2, 2021. https://www.brewersassociation.org/press-releases/brewers-association-releases-annual-growth-report-for-2019/.

- Brewers Association. 2021c. Diversity program. Accessed February 25, 2021. https://www.brewersassociation.org/programs/diversity/.

- Brewers Association. 2022. Annual craft brewing industry production report. Accessed May 18, 2022. https://www.brewersassociation.org/press-releases/brewers-association-releases-annual-craft-brewing-industry-production-report-and-top-50-producing-craft-brewing-companies-for-2021/.

- Brewing Change. 2021. Accessed February 25, 2021. https://us.budweiser.com/en/brewing-change.html.

- Brewing Change Collaborative. 2021. Home page. Accessed February 25, 2021. https://brewingchangecollaborative.org.

- Buratti, J., and R. Hagelman, III. 2021. A geographic framework for assessing neolocalism: The case of Texas cider production. Journal of Cultural Geography 38 (3):399–433. doi: 10.1080/08873631.2021.1951004.

- Chapman, N. G., J. S. Lellock, and C. D. Lippard, eds. 2017. Untapped: Exploring the cultural dimensions of craft beer. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press.

- Chapman, N. G., M. Nanney, J. S. Lellock, and J. Mikles-Schluterman. 2018. Bottling gender: Accomplishing gender through craft beer consumption. Food, Culture & Society 21 (3):296–313. doi: 10.1080/15528014.2018.1451038.

- Faubourg Brewing Co. 2021. Our story. Accessed December 14, 2021. https://faubourgbrewery.com/about-us/our-story.

- Fletchall, A. M. 2016. Place‐making through beer‐drinking: A case study of Montana’s craft breweries. Geographical Review 106 (4):539–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1931-0846.2016.12184.x.

- Fletcher, R. J., A. Revell, B. E. Reichert, W. M. Kitchens, J. D. Dixon, and J. D. Austin. 2013. Network modularity reveals critical scales for connectivity in ecology and evolution. Nature Communications 4 (1):1–7. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3572.

- Gatrell, J., N. Reid, and T. L. Steiger. 2018. Branding spaces: Place, region, sustainability and the American craft beer industry. Applied Geography 90:360–70. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2017.02.012.

- Ghavampour, E., and B. Vale. 2019. Revisiting the “model of place”: A comparative study of placemaking and sustainability. Urban Planning 4 (2):196–206. doi: 10.17645/up.v4i2.2015.