Yi-Fu Tuan was a giant among geographers. He was among a handful of leading geographers who have transformed the discipline since 1945 and one of the most highly cited. His 1977 book Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience alone has been cited nearly 17,000 times according to Google Scholar (Tuan Citation1977). Very few books by geographers have been cited more. Despite his obvious centrality to the postpositivist trajectory of human geography, Yi-Fu was always something of a maverick in geography, steering his own ship through the turbulent theoretical trajectories in the years since 1970. As he noted in his wonderful autobiography, Who Am I? An Autobiography of Emotion, Mind, and Spirit (Tuan Citation1999), he often felt like a minnow flipping around for attention in the post 1980 firmament of geography. In a period that more or less coincided with the 1970s, however, Yi-Fu and a handful of others were the big fish in the rise of humanistic geography—an approach to geography that was born as both a recognition of the specific qualities of being human and a critique of the overkill of the quantitative revolution. For that long moment, at least, Yi-Fu was one of the flavors of the day. This must have been a surprise to him. As someone who confessed to both geographical and social awkwardness, he was not a scholar who spent a great deal of time networking or attending departmental parties at American Association of Geographers (AAG) conferences. His version of networking later in his career, when I knew him, was his regular meetings with colleagues and students at the Sunprint (later Sunroom) Café on Madison’s State Street. When he wasn’t traveling to give prominent endowed lectures around the world, he could be found somewhere between his apartment on Madison’s Lake Monona, his office in Science Hall, and a number of his favorite cafés on State Street. In his voluminous work since the 1970s, he assiduously avoided engaging with any of the theoretical and political shifts that moved through the discipline, plowing his own furrow while the academic landscape went through dramatic shifts under the influence of Marxism, feminism, poststructuralism and other theoretical trajectories.

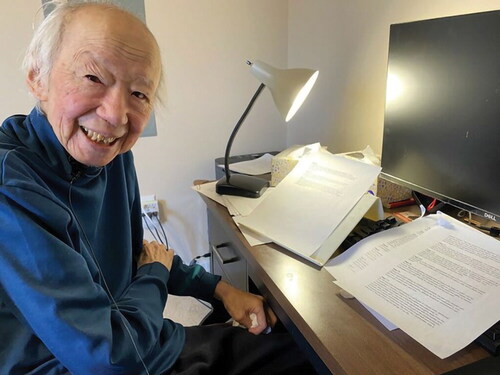

By the end of his life, Yi-Fu had been contributing to published academic geography for sixty-eight years from “Types of Pediment in Arizona,” in the Yearbook of Pacific Coast Geographers in 1954 (Tuan Citation1954) to his final self-published pamphlet in 2022 (Tuan Citation2022). In this final pamphlet he compared this longevity to one of his heroes, Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859).

As to the academic fields we both traversed, there were similarities too, though we lived in different times and places. We both have contributed to physical geography, human geography, and what is known as humanist geography. Humboldt’s magnum opus, Cosmos, opened new areas in physical and geographical science. This is widely known. What is less widely known is that he was the first to show how landscape painting and poetry could be read as people’s more general attitude toward nature and place. Humboldt believed in communication, which meant speaking and writing well. I share this belief, though not the skill. (Tuan Citation2022, 4)

There was no-one quite like Yi-Fu. He managed to come out of a PhD on desert geomorphology and have the single-mindedness and confidence to develop his own path—a lifelong journey considering how we humans make the earth into a home. His most famous work delineated experiential human relationships to space and place—a topic surprisingly absent from a discipline that translates as “earth writing.” Before 1970, there were few who would have said that place was the central theme of human, or indeed all, geography. After 1980 the idea of place was clearly central to what we geographers are about. It remains so. Although Tuan is not the only geographer to have led the way in this transition (see Relph Citation1976; Buttimer and Seamon Citation1980), he was the one who articulated its importance most clearly. Since the 1970s, Yi-Fu continued an extraordinary publishing career considering themes such as morality and human goodness (Tuan Citation1986, Citation1989), the roles of dominance and affection in our relations to the environment (Tuan Citation1984), cosmopolitanism and localism (Tuan Citation1996), the need for aesthetics in human life (Tuan Citation1993), the fantasies of escapism (Tuan Citation1998), and the place of religion (Tuan and Strawn Citation2009). All of these are facets of how humans get meaning from, and experience, this singular planet we are blessed with. Sometimes, of course, these pursuits of Yi-Fu seemed otherworldly, given the wicked problems that humans face—problems such as climate change, geopolitical conflict, human exploitation of other humans, and the persistence of racism. Yi-Fu was often accused of naivete or blindness to genuine human problems. He gently insisted, though, that even with all the problems we face, there remain themes that have the potential to bind all of us humans in a recognition of what it is to be human. It was his insistence and single-mindedness that led to Yi-Fu’s work being lauded well beyond the confines of the discipline. The eminent historian and public intellectual Simon Schama called Yi-Fu “one of the most remarkable and creative forces in the intellectual life of our time,” and a piece in the Chronicle of Higher Education called him “the most influential scholar you have never heard of” (Monaghan Citation2001).

Yi-Fu’s Journey

Yi-Fu was born in 1930 in Tianjin, China. China in the 1930s was suffering from both a civil war between the Nationalist Party and the Red Army of the Chinese Communist Party and, from 1937, war with Japan. As his father, Mao-Lan Tuan, worked for the Foreign Office of the Nationalist government, Yi-Fu was moved at a young age to the temporary capital, Chongqing, to escape the advancing Japanese army. In a film made for the AAG’s Geographers on Film series, Yi-Fu reflected on a childhood “constantly escaping from the Japanese” and hiding during “daily air raids.” At the age of ten, Yi-Fu moved with his family to Australia via Hong Kong involving a dramatic flight over Japanese-held territory. In 1946, the Tuan family moved to the Philippines and then London as Yi-Fu’s father was posted between embassies in the years leading up to the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. After attending school in London for two years, Yi-Fu briefly studied at University College London before moving to University College at the University of Oxford to study geography. He considered Oxford to be the pinnacle of scholarship in the humanities but found human geography in the late 1940s at Oxford to be disappointingly “routine and rather dry.” He was saved by the geomorphology taught by Robert Beckinsale and read the work of the Berkeley geomorphologist John E. Kesseli, which led him to pursue his doctoral work on the geomorphology of desert pediment landforms in southeast Arizona at Berkeley with Kesseli while taking multiple seminars with Carl Sauer. He completed his doctorate in 1957 and took up his first position at the University of Indiana before moving to the University of Chicago for a postdoctoral position in statistics. In 1959 he moved to the University of New Mexico as one of a two-member department, which necessitated wide-ranging teaching but released him from too much publishing pressure for tenure. One consequence of this was that he could reflect on big humanities-based questions he had found missing in Oxford. During his time in New Mexico, surrounded by the desert landscapes he loved, Yi-Fu enacted his conversion from geomorphologist and author of “The Misleading Antithesis of Penckian and Davisian Concepts of Slope Retreat in Waning Development” (Tuan Citation1958) to the proto-humanistic geographer who would write “Attitudes toward Environment: Themes and Approaches,” in a collection edited by his fellow humanist David Lowenthal (Tuan Citation1967). He had also started to contribute to the journal Landscape, produced and edited by J. B. Jackson. In a sign of things to come thirteen years later, one of these contributions was called “Topophilia: or, Sudden Encounter with the Landscape” (Tuan Citation1961). Landscape was an important site for the development of ideas that would become humanistic geography and Yi-Fu and Lowenthal were frequent contributors (Blankenship Citation2018).

In 1966, Yi-Fu went to the University of Toronto for a joint appointment between Geography and Landscape Architecture before moving to the University of Minnesota as Professor of Geography and East Asian Studies, where he spent fifteen years between 1968 and 1983. When Yi-Fu moved to Minnesota in 1968 he was appointed as a full Professor. At the time he was an author of one monograph, The Hydrological Cycle and the Wisdom of God, published as the first of the University of Toronto Department of Geography Research Publications series (Tuan Citation1968). The State of New Mexico was about to publish his coauthored The Climate of New Mexico (Tuan, Everard, and Widdison Citation1969) and his regional textbook, China, was just around the corner (Tuan Citation1970). In addition, he had published a smattering of chapters and papers that must have seemed highly eclectic, reflecting Yi-Fu’s journey from geomorphology to the nascent humanistic geography. The search committee considering his application would have seen both his Annals paper “New Mexico’s Gullies: Critical Re-examination and New Observations” (Tuan Citation1966) and “Mountains, Ruins, and the Sentiment of Melancholy” published in Landscape magazine (Tuan Citation1964), among his recent publications. I suspect a few eyebrows were raised. Although Yi-Fu had used the term humanistic to describe his interpretive method as early as 1963, it was in an article published in the New Mexico Quarterly and unlikely to have been read by many geographers (Tuan Citation1963). Humanistic geography, as such, had not yet been named. By 1972, Yi-Fu’s reputation was already such that the AAG included him for their Geographers on Film series.Footnote1 At that point Yi-Fu had not published any of his major statements of what would become humanistic geography, but he was clearly associated with a growing movement in the discipline that contrasted with the quantitative work of the previous few decades. In the film, where he was interviewed by John Fraser Hart (another contributor to Landscape), he described his focus of interest as “humanistic geography” but only because the wider term “human geography” had already been taken. Humanistic geography, he remarked, denoted an interest in “the human condition” that was a hallmark of the humanities. In the film, Fraser Hart questioned Yi-Fu about his relationship to the geography of the quantitative revolution. Yi-Fu insisted that his humanistic approach was not supposed to replace such approaches but, rather, add to them. When asked if his approach was “exceedingly subjective,” Yi-Fu replied that “in a way humanistic geographers can turn the table around and say we are really being objective because we recognize, explicitly, the subjectivity that enters in … .” It was during Yi-Fu’s time at Minnesota that he adopted Kenneth Olwig as a PhD student. Olwig recalls the atmosphere at Minnesota as Yi-Fu’s humanistic approach began to challenge the hegemony of quantitative approaches as well as the certainties of emerging radical geographies.

Yi-Fu’s inspiration was enormous because he was so genuinely radical, as opposed to many of the self-important quantitative “revolutionaries” and hothouse university “radicals” that came out of the academic woodwork at the time. Yi-Fu was then doing much to deflate the Quantitative Revolution’s positivist balloon. When, following a prominent positivist guest speaker’s presentation at a department seminar, and after the departmental professors had, one by one, each made appropriately professorially polite comments, then Yi-Fu would quietly, in his unprepossessing and self-effacing way, pose a deceptively simple question that would somehow manage to cause the speaker’s entire pseudo-scientific facade to collapse in rubble at the startled department’s feet. Unlike some of the erstwhile positivists, born again as “radicals,” who used impenetrable language and had the right answers, Yi-Fu eschewed both jargon and the believer’s truths, offering, instead, a subverting Socratic arsenal of incisive questions.

In January 1984, Yi-Fu moved to the University of Wisconsin, Madison. In 1985 he became both the Vilas Research Professor and John Kirkland Wright Professor of Geography, positions he held until his retirement in 1998. Whereas the first of these appointments is an established research chair at the University of Wisconsin that entitles its bearer to a reduced teaching load, the second was personal and a title that Yi-Fu chose himself. The choice is significant, as J. K. Wright was one of the very few people that clearly prefigured Yi-Fu’s style and content, most famously in his presidential address of 1947, where he called on geographers to take the geographical knowledge and imaginations of people seriously (Wright Citation1947), but also in his early embrace of literature as sources of geographical information (Wright Citation1924).

Yi-Fu was the author of twenty-three books in addition to a series of self-published pamphlets he continued to write and send to friends and colleagues in his later years. His work has been translated into Chinese, German, Italian, Japanese, Polish, Portuguese, Spanish, and Swedish. Although he is best known as an author of books, Yi-Fu also published more than 150 papers and book chapters, including ten articles in the Annals between 1962 and 2004. Yi-Fu received multiple awards in his long and distinguished career including a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship, the Callum Geographical Medal of the American Geographical Society, the Lauréat d’Honneur of the International Geographical Union, and the Vaudrin-Lud Prize of the International Festival of Geography. In 2013 he received the Inaugural Award in Creativity in Geography from the Association of American Geographers. He was a Fellow of the British Academy, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Among all these national and international honors, he was also voted Best Professor by the Wisconsin Student Association in 1992, an award of which he was particularly proud.

Tuanian Lessons

There are three aspects of Yi-Fu’s work that I think are particularly important for geography and geographers. The first of these surrounds the kinds of things he encouraged geographers to study. When Yi-Fu was studying desert pediments in the U.S. Southwest, there was little or no room for a geographer to ask “What is space?” or “What is place?” Few geographers were asking how landscapes reflected human values and how places from the domestic interior to the whole planet provided us with sources of value and belonging. No one would have written a book about how we relate to pets (real and metaphorical) through twin forces of domination and affection long before similar, but differently expressed, ideas were familiar to geographers from the writing of Foucault (Tuan Citation1984). No one would have ruminated on why humans insist on the most banal of things—a house gutter or a pair of scissors—being attractive or beautiful (Tuan Citation1993). These are the questions Yi-Fu asked in his books. Questions such as these changed what was possible to write about in geography, and we have benefited enormously from this inheritance. He was instrumental in opening up whole areas of our discipline (and others) that we now take for granted. The importance of the body, geographies of the senses, literary geographies, and the study of emotions such as fear (Tuan Citation1979) were all almost absent in geography pre-Tuan. These are exactly the kinds of themes that are now clearly part of geographical enquiry—most clearly in cultural geography and geohumanities. Another theme that Yi-Fu explored throughout his life, reflecting his generally optimistic attitude to life, was “goodness.” Everywhere he looked, and despite the violence and ugliness of which he was clearly aware, Yi-Fu found versions of human goodness both in the biographies of individuals and in the places that humans have made. This could seem overly rosy in a world beset by human-induced troubles that seem so much more pressing, and it is not a theme that has been reflected in geography more widely.

The second aspect of Yi-Fu’s work that we have been lucky enough to inherit is his ability to see geography everywhere. By this I mean the kinds of sources to which Yi-Fu looked to write his books. This included his willingness to look to literature and the arts for evidence of human attachments to the earth (Tuan Citation1978, Citation1991). Human thought lies at the center of Yi-Fu’s geography and humanistic geography more generally and records of that thought are therefore important sources for geographical inquiry. A reference list in a Yi-Fu book is rarely a list of recently published papers. Usually, it is an eclectic mix of classic novels, texts from ancient China, anthropological explorations of diverse cultures, snippets of psychology, children’s stories, or plans of medieval cities. He was willfully magpie-like in his tendencies. Again, when Yi-Fu was completing his PhD at Berkeley, there was very little that was anything like this in geography. Another aspect of Yi-Fu’s attitude to what counts as evidence in humanistic inquiry is well captured by a short essay he wrote in 2001 titled “Life as a Field Trip.” Here he recounts his experience of teaching the course Environment and the Quality of Life, a course I was lucky enough to take in 1989.

One may think that a course of this nature required fieldwork—and if not work then the less sweaty trip or tour. Students expected at least bus tours, and they were somewhat bewildered that none was scheduled. At the first meeting I would try to assuage their anxiety by saying, “Feel at ease, for all of you have already satisfied one basic course requirement, which is a minimum of eighteen years of fieldwork. The challenge now is to make sense of what you have picked up in all that time.” Eighteen years? They quickly realized that I was referring to their life span. They had been in the field all their life without knowing it, except periodically, when they were actively engaged in a project. (Tuan Citation2001, 41)

To Yi-Fu, reflecting on his own experience was part of geographical enquiry—a kind of reflection that had been rigorously bracketed out during the quantitative years. Yi-Fu attempted to convey to his students the benefits of leading an examined life. One of the sources of information for Yi-Fu’s own research and writing was his own experience (Tuan Citation1999).

The third element of Yi-Fu’s work that we have inherited is the permission he has given us to write in a clear, expressive, and often poetic manner. Work in human geography has become much more diverse in the way it is written since the 1970s when Yi-Fu’s work began to be published. There is an element of creative writing in his texts that invites the reader into his internal dialogues. The blurbs on his books, from scholars and writers from many backgrounds, frequently note the poetic quality of the writing. The historian Dominic Pacyga, for instance, called the book Humanist Geography (Tuan Citation2012) “an extraordinary prose poem.” This is not something that could be accurately said about much academic writing in the social sciences, which is often not inviting. Yi-Fu’s writing is an invitation to think with him. It is simultaneously erudite and accessible. There are certain scholars who you can identify through the singular nature of their style—writers who escape a cookie-cutter approach to academic prose and what it should look and sound like. Yi-Fu was one of those as early as his first major book, Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values (Tuan Citation1974). Consider the following quote:

The most intense aesthetic experiences of nature are likely to catch one by surprise. Beauty is felt as the sudden contact with an aspect of reality that one has not known before; it is the antithesis of the acquired taste for certain landscapes or the warm feeling for places that one knows well. (Tuan Citation1974, 94)

These three aspects of Yi-Fu’s gifts to us all suggest that his influence is much greater than his obvious and substantial impact as a founder of humanistic geography in the 1970s. His influence is persistent and can be seen in much of the work of contemporary geographers—in the work of geographers engaging with care, emotions, the senses, embodiment, and place, for instance. It can also be seen in the range of sources geographers of the present day have permission to use in their research—sources that include art, literature, music, and self-reflection that can be found in today’s fields of cultural geography, literary geographies, and geohumanities for sure, but also in geography more widely. Finally, Yi-Fu’s focus on writing is reflected in current attempts to break open the prison of what passes for academic writing—particularly in the field of creative geographies but also in journals like cultural geographies and GeoHumanities, where part of the logic of the journals is to embrace a wider range of forms of expression. Yi-Fu’s legacy is much greater than the moment of humanistic geography in the 1970s.

Personal Reflections

Yi-Fu had a particularly lasting and formative impact on those of us who were fortunate enough to know him as a friend, mentor, supervisor, or colleague. He was generous, often funny, and extremely thoughtful and considered in conversation and when making comments on the work of others. To Steven Hoelscher, now Professor of American Studies at the University of Texas, Austin and a student of Yi-Fu’s, Yi-Fu opened up the possibilities of interdisciplinarity.

Through his writing and in his graduate seminars, Yi-Fu demonstrated that asking and addressing transcendent questions was more interesting, more impactful, than maintaining disciplinary boundaries. The effects of that perspective are wide-ranging and profound. I’m continually astonished at the many colleagues from outside geography—including architecture, art history, comparative literature, English, history, Middle Eastern studies, women’s and gender studies—who tell me how influential Yi-Fu’s books were to them. He certainly opened the door for a geographer like me to feel at home in an interdisciplinary field like American studies.

Another student of Yi-Fu’s, Paul Adams, Professor of Geography also at the University of Texas, Austin, noted that Yi-Fu adopted a general philosophy of “yes, but” rather than the more common critical rejection of viewpoints other than his own. Adams noted how Yi-Fu’s “published and unpublished writings celebrate the practical wisdom and good will of ordinary people, including plumbers, carpenters, and children.” He was inspired by Yi-Fu’s late career turn to religious questions that prompted him to “take it as a personal challenge to better articulate my own philosophy of life.” Theano Terkenli, Professor of Cultural Geography at the University of the Aegean, Greece, visited Madison for a semester while she was undertaking a PhD at the University of Minnesota. Her comments during a recent celebration of Yi-Fu’s life held to mark his ninetieth birthday by the Landscape Research GroupFootnote2 reflected Adams’s comments on the capacity of Yi-Fu’s work to induce self-reflection:

Professor Tuan’s legacy to me has been an abundance of wisdom which finds its place at the basis of my formation as an academician, as a geographer, and which consequently helped shape me as a teacher, as a person, and as a scholar. His contribution to my quest for who I am as a human being, who I want to be as a human being, and what meaning to give my human existence is even greater. It is his lifelong gift to me.

Another one of Yi-Fu’s students, Karen Till, Professor of Cultural Geography at Maynooth University in Ireland, noted how Yi-Fu’s definition of place as a “field of care” as well as the way he supervised her as a PhD student translates into her work with others:

I think of Yi-Fu’s PhD supervisions as a field of care and try to extend relations of respect in my own collaborations with students, artists, activists, and community leaders, in hope that this geographical practice makes more just and healthy places in which to live.

For a significant period of Yi-Fu’s retirement, Kris Olds was the department head in Madison. He reflected on Yi-Fu’s unique retirement habits, telling me:

He remained intellectually active but in particular drew in and engaged with undergraduate students via meetings over coffee, lunches, etc. He loved meeting them in a downtown Starbucks right beside campus; a suitable place to people watch, too. The downtown of Madison, Wisconsin, was the anchor zone for personal engagements. He reveled in this dense university town’s micro-geographies.

Olds reflected on Yi-Fu’s later years when he was no longer able to get around town and was largely confined to his retirement complex.

While correspondence and much praise regularly came in from all over the world via e-mail and the post, and while he was ultimately in love with the Death Valley landscape, it was the local nature of life in a small downtown Midwestern college-town in “America’s Dairyland” that facilitated the personal engagement that helped sustain him until he passed away at 91+ years. Yi-Fu was a kind and generous person until he passed, always curious, with a unique laugh and a sparkle in his eye: we were so lucky to have been able to regularly engage with him after his formal academic career ended.

Drawing to a Close

As Yi-Fu reached the end of his life he often paused for reflection and was uncommonly vulnerable about his own hesitancies and doubts. Yi-Fu’s life and work was not all plain sailing. In his autobiography he acknowledged that he was attracted to other men and that while being a well-traveled cosmopolite, he was also often lonely. Again, comparing himself to Alexander von Humboldt, he noted how both of them had missed the warmth of human companionship—neither had experienced “one thing that ought to be every human being’s birthright—namely, a beloved person to share cookies with before turning to bed” (quoted in Monaghan Citation2001). Yi-Fu also had a complicated relationship with what we might broadly call identity politics. He was a committed universalist, always looking for what he believed people share. Although he frequently experienced racial slurs growing up, and continued to be treated differently as a Chinese man in the United States throughout his life, he was determined to not let this define him. I think his logic was that White people did not have to constantly define themselves as White, so why should he constantly have to write, speak, or act as a Chinese person. In his view, it was patronizing to expect him to represent Chineseness in some way. Having said that, toward the end of life, he noted with some regret that he had not been more vocal or active during the civil rights, free speech, or environmental movements that surrounded him.

Few geographers wrote so much about impending death as Yi-Fu did. He had embraced Christianity as a teenager and his faith became more visible in his last decades, including a book on religion and place (Tuan and Strawn Citation2009). This guided much of his worldview and allowed him to ruminate on death in his self-published pamphlets:

So, what do I fear as death approaches? I fear unbearable pain, yet pain drives away fear of oblivion and, indeed, welcomes it. Other than pain, I fear being alone. Dying is easier if there is one truly caring person in the room and he or she need not even be someone I know. To put this another way, dying is easier if it is preceded by a miracle. The miracle is, for me, the existence and lure of the good, incarnate in Christ and in all who follow his footsteps. (Tuan Citation2020, 154)

My contribution to humanist geography in a nutshell? It is that I have enriched the meaning of the word “human.” Originally a natural science, geographers were intrepid explorers to little-known parts of the world. Even in my time as undergraduate, the professors of geography at both Oxford and Cambridge were explorers, Kenneth Mason in the Himalayas and Frank Debenham in Antarctica. They showed little interest in people. When geographers did include people, they were treated as though they were just another physical force capable of changing the face of the Earth. From the 1930s onward, people were credited with other attributes: first, culture, under the influence of Carl Sauer; then psychology, under the influence of David Lowenthal and Robert Kates (1960s); and lastly, a strong aesthetic/moral drive that began in the 1970s. A mystery to me is how something so obvious about us human beings can be ignored for so long. But it is, which goes to show our subservience to the popular paradigms of the time. Hence, once more, young traveller, have the guts to steer your own ship with only the baffling hints of life below and the stars as your guide. (Tuan Citation2022, 50)

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Paul Adams, Steven Hoelscher, Kris Olds, Kenneth Olwig, and Karen Till for their words and insights, and to Theano Terkenli for inviting me to take part in Yi-Fu’s ninetieth birthday celebrations. Most of all, I am grateful to Yi-Fu.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tim Cresswell

TIM CRESSWELL is the Ogilvie Professor of Human Geography in the School of GeoSciences at the University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH9 3JW, UK. E-mail: [email protected]. His research focusses on geographies of place and mobility and their role in the constitution of social and cultural life.

Notes

1 Both of these films can be seen at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XtufsJ_fU94.

2 For a recording see https://lex.landscaperesearch.org/content/legacy-of-yi-fu-tuan-a-panel-discussion/.

References

- Blankenship, J. D. 2018. Midcentury geohumanities: J. B. Jackson and the “magazine of human geography.” GeoHumanities 4 (1):26–44. doi: 10.1080/2373566X.2017.1386075.

- Buttimer, A., and D. Seamon. 1980. The human experience of space and place. New York: St. Martin’s.

- Heidegger, M. 1967. Being and time. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Monaghan, P. 2001. Lost in place. Chronicle of Higher Education. Accessed December 1, 2023. https://www.chronicle.com/article/lost-in-place/

- Relph, E. 1976. Place and placelessness. London: Pion.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1954. Types of pediment in Arizona. Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers 16 (1):17–24. doi: 10.1353/pcg.1954.0005.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1958. The misleading antithesis of Penckian and Davisian concepts of slope retreat in waning development. Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 67:212–14.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1961. Topophilia: Or sudden encounter with the landscape. Landscape 11:29–32.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1963. The desert and the sea: A humanistic interpretation. New Mexico Quarterly Autumn: 329–31.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1964. Mountains, ruins, and the sentiment of melancholy. Landscape 14:27–30.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1966. New Mexico’s gullies: Critical re-examination and new observations. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 56 (4):573–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8306.1966.tb00581.x.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1967. Attitudes toward environment: Themes and approaches. In Environmental perception and behavior, ed. D. Lowenthal, 4–17. Chicago: University of Chicago.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1968. The hydrologic cycle and the wisdom of God:; A theme in geoteleology. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1970. China. London: Longman.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1974. Topophilia: A study of environmental perception, attitudes, and values. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1977. Space and place: The perspective of experience. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1978. Literature and geography: Implications for geographical research. In Humanistic geography: Prospects and problems, ed. D. Ley and M. Samuels, 194–206. London: Croom Helm.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1979. Landscapes of fear. New York: Pantheon.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1984. Dominance and affection: The making of pets. London: Yale University Press.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1986. The good life. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1989. Morality and imagination: Paradoxes of progress. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1991. Language and the making of place: A narrative-descriptive approach. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 81 (4):684–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8306.1991.tb01715.x.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1993. Passing strange and wonderful: Aesthetics, nature, and culture. Washington, DC: Island Press for Shearwater Books.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1996. Cosmos & hearth: A cosmopolite’s viewpoint. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1998. Escapism. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 1999. Who am I? An autobiography of emotion, mind, and spirit. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 2001. Life as a field trip. Geographical Review 91 (1–2):41–45. doi: 10.2307/3250803.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 2012. Humanist geography: An individual’s search for meaning. Staunton, VA: George F. Thompson.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 2020. Who am I? A sequel. Madison, WI: Author.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 2022. Geography from 1947 to 2022: A travelogue. Madison, WI: Author.

- Tuan, Y.-F., C. E. Everard, and J. G. Widdison. 1969. The climate of New Mexico. Santa Fe, NM: State Planning Office.

- Tuan, Y.-F, and M. A. Strawn. 2009. Religion: From place to placelessness. Chicago: Center for American Places at Columbia College Chicago, distributed by the University of Chicago Press.

- Wright, J. K. 1924. The geography of Dante. Geographical Review 14:319–20.

- Wright, J. K. 1947. Terrae incognitae: The place of the imagination in geography. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 37 (1):1–15. doi: 10.1080/00045604709351940.