Abstract

Climate change adaptation is a power-laden process that requires engagement and negotiation between people with diverse needs, interests, and levels of authority. Entrenched hierarchies in adaptation decision making influence what is considered legitimate policy and action, whose values are prioritized, and the interests of which actors are excluded. Through content and discourse analysis of interviews and focus group discussions with policymakers and decision makers across multiple spatial and jurisdictional levels, we illustrate how specific actors involved in adaptation efforts comprehend and engage with tensions, institutional politics, and community-level power dynamics, focusing on the experiences of rural farmers who are often sidelined in adaptation processes. We advance critical scholarship on the politics of adaptation and the politics of scale to demonstrate how power relations move within and across levels of decision making, by scrutinizing the discursive and material construction of scales and subjects. We argue that nuanced investigations of power and its (re)production across levels and scales are crucial to expose the underrepresentation of marginalized citizens in adaptation debates and to envision subversive political interventions toward climate justice. Key Words: agriculture, climate change adaptation, climate justice, decision making, Ghana.

气候变化适应是一个充满权力的过程, 需要不同需求、不同利益、不同权威等级人群的参与和协商。在适应决策中, 根深蒂固的等级制度影响了哪些政策和行动是合法的、哪些价值观具有优先权、哪些人的利益被排除在外。通过对采访内容和叙述的分析, 以及多空间管辖尺度的政策制定者和决策者的焦点小组讨论, 我们展示了适应的行为者如何理解和参与对抗、体制性政治和社区权力变更, 重点关注了适应过程中常常被边缘化的农民的经历。本文批判性地研究了适应和空间尺度的政治性, 探讨了对尺度和主题的话语构建和物质建构, 展示了权力关系如何在决策等级之内和之间进行传递。我们认为, 深入研究跨等级、跨空间尺度的权力及其(再)生产, 对于揭示边缘人群在适应争辩中的代表性不足、设想对气候正义的颠覆性政治干预, 至关重要。

La adaptación al cambio climático es un proceso cargado de poder que requiere del compromiso y la negociación entre gente con diversas necesidades, intereses y niveles de autoridad. Las jerarquías afincadas en la toma de decisiones sobre la adaptación influyen sobre lo que se consideran políticas y acción legítimas, cuyos valores se priorizan, y en los intereses sobre cuáles actores deben excluirse. Por medio del análisis de contenido y discurso de las entrevistas y las discusiones de grupos focales con políticos y tomadores de decisiones, a través de múltiples niveles espaciales y jurisdiccionales, ilustramos cómo actores específicos involucrados en los esfuerzos de adaptación comprenden y se comprometen con las tensiones, las políticas institucionales y las dinámicas del poder a nivel comunitario, centrándonos en las experiencias de los agricultores rurales que a menudo son dejados de lado en los procesos de adaptación. Avanzamos la erudición crítica sobre las políticas de adaptación y las políticas de escala para demostrar cómo las relaciones de poder se desplazan dentro y a través de los niveles de toma de decisiones, por medio del escrutinio de la construcción discursiva y material de escalas y sujetos. Argüimos que las investigaciones matizadas sobre el poder y su (re)producción a través de niveles y escalas son cruciales para exponer la infrarrepresentación de los ciudadanos marginados en los debates sobre adaptación, para vislumbrar intervenciones políticas subversivas hacia la justicia climática.

Human geographers and other social scientists have repeatedly demonstrated the disproportionate impacts of the climate crisis. Inequalities embedded in uneven power relations continue to mandate who is most at risk to climatic hazards and how (Thomas et al. Citation2019; Barnett Citation2020). Individual citizens, governing authorities, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and international agencies are at the frontlines of climate action as the need to adapt and build resilience is increasingly urgent for societies to avoid loss of lives and livelihoods. Adaptation is a dynamic process that requires agents to negotiate across needs, interests, and levels of authority (Eriksen, Nightingale, and Eakin Citation2015; Harris, Chu, and Ziervogel Citation2018; Leck and Simon Citation2018), with many seeking power over resources and climate-related agendas that are shaped by multiple spheres of influence. Entrenched politics and hierarchies delineate approaches to adaptation (Ziervogel Citation2019) and produce “winners” and “losers” with respect to who can adapt to climate change and who is left out of adaptation policy and decision making (Scoville-Simonds, Jamali, and Hufty Citation2020).

Governments in low- and lower middle-income countries face complex economic, political, and social challenges when addressing climate-related impacts (Phuong, Biesbroek, and Wals Citation2018). In such contexts, rural agrarian communities are especially at risk from temperature rise, erratic rainfall, and drought and flooding events that threaten food and livelihood security (Abbam et al. Citation2018). Ghana—the focus of this empirical study—has demonstrated innovation and progress in adaptation responses. Despite efforts toward decentralization, however, a top-down system of authority undermines opportunities for community participation in adaptation planning. Moreover, rural adaptation interventions often adhere to informal politics and long-standing patriarchal structures that prioritize specific actors while disregarding others along the lines of gender, age, clan lineage, and political affiliation. National adaptation plans often overlooked the consequential roles of power and politics that shape adaptive decision makingFootnote1 and outcomes.

Human geography, we argue, could play a more prominent role in conceptualizing and identifying power and politics at work in the fragmented and contested fabrics of climate change adaptation. Here, we align with critical debates on the politics of adaptation (Eriksen, Nightingale, and Eakin Citation2015; Tschakert et al. Citation2016; Nagoda and Nightingale Citation2017) and the politics of scale (Marston, Jones, and Woodward Citation2005; Jones Citation2017; Cobarrubias Citation2020) to examine distinct levels of adaptive decision making in Ghana. Theorizations of “scales” and “levels” have advanced significantly due to inquiries into spaces, places, and people involved in policy and governance (Marston, Jones, and Woodward Citation2005). For this study, we adopt the term scale as conceptualized by Gibson and colleagues (Citation2000) to refer to spatial and jurisdictional dimensions of adaptive decision making. We define levels as the units of our analysis located at different points on a dimensional scale (Cash et al. Citation2006). Although we identify these levels for analytical purposes, we do not view them as a “nested hierarchy” that neatly encompasses the local, national, and global. Rather, we view them as socially and politically constructed, hinged on formal structures of governance and the everyday practices of social actors (Jones Citation2017; Cobarrubias Citation2020).

In this critical analysis, we draw on Foucault’s (Citation1980) notion of power as relational, diffuse, intersectional, embodied, and ever circulating, yet also a constant in the complex workings of everyday life. We apply this notion of power to expose how such fluid and uneven dynamics strengthen or erode adaptive opportunities of marginalized farming populations in the context of Ghana’s hierarchical adaptation planning. Specifically, we investigate the discursive and material processes through which farmers are subjectified in relation to other stakeholders across levels of decision making, and the extent to which such subject making affects their positions of power in adaptation planning and action. To do so, we apply content and discourse analysis approaches to material collected through interviews and focus group discussions with Ghanaian stakeholders involved in climate change policy and planning. We begin by examining how specific actors comprehend and engage with tensions that arise from cross-level interactions and political agendas that govern adaptation efforts. We then illustrate how institutional politics and power dynamics travel within and across levels of adaptive decision making, paying particular attention to how such flows of power maintain established hierarchies or allow disenfranchised actors to (re)negotiate scalar boundaries. Finally, we assess how actors brought into fluid power relations uphold or contest dominant discourses that (re)produce boundaries between decision-making levels and subjects with respect to who can adapt, and when and where.

Through this explicit focus on how power travels and operates in Ghana’s adaptation landscape, we make three contributions to advance critical scholarship on climate change adaptation. First, by bringing into conversation the literatures on the politics of adaptation and the politics of scale, we expose the discursive and material processes that both maintain and confront the fluid nature of power asymmetries in adaptation efforts. Nuanced snapshots, rather than a comprehensive picture of adaptation as a power-laden process, illustrate how biases in adaptive decision making are materially and discursively constructed as actors across levels and scales are implicit in sustaining (or challenging) oppressive hierarchies that further sideline the needs and aspirations of already disenfranchised citizens.

Second, we bring to the fore procedural and recognitional injustices with respect to who is represented and who is silenced across levels and scales in the relational web of adaptive planning and action. Although procedural injustices in climate-related policy—those that lead to the exclusion of vulnerable groups (Chu and Michael Citation2019)—are relatively well documented (Bailey and Darkal Citation2018; Schapper Citation2018; Brandstedt and Brülde Citation2019; Shi Citation2021), the ways power and domination constrain recognition, and by extension the participation of marginalized individuals in adaptive decision making, remain underexplored (Wood et al. Citation2018).

Third, through such a fine-grained investigation of cross-level and cross-scale operations of power and their (re)production, we argue that it is possible to not only unmask systemic processes of oppression and subservience but also to subvert these processes and envision more just political interventions that benefit those most at risk from the climate crisis.

Literature Review

We begin with an overview of pertinent concepts and debates that foreground geographic perspectives on hierarchies and power, and their contributions to the scholarly field of climate change adaptation: (1) theorizations of scales and levels of adaptive decision making; (2) the politics of scale; (3) the politics of adaptation; and (4) power in multi- and cross-level adaptive decision-making processes.

Scales and Levels of Adaptive Decision Making

Scholars across the natural and social sciences have fought fierce battles over the usage and meanings of the concepts of scales and levels (Neumann Citation2009), generically defined as spatial, temporal, and jurisdictional modes of operation (Gibson, Ostrom, and Ahn Citation2000; Cash et al. Citation2006). In human geography and political ecology, these two concepts have undergone profound theoretical transformations (Neumann Citation2009; Jones et al. Citation2017). Most notably, the fields have moved away from notions of levels and scales as predetermined, territorial, and natural entities (Bulkeley Citation2005) to a more nuanced understanding of their constructed, dynamic, and contested nature (Benson Citation2010; see next section). Central to this conceptualization is the notion of performativity, indicating the actors who exist within levels and scales as complicit in the complex interactions, perceptions, and subjectivities that uphold scalar boundaries (Glass and Rose-Redwood Citation2014). In the context of climate change adaptation, level and scale have been used to examine a myriad of interactions, negotiations, policies, and structures that mandate societies’ and individuals’ capacities to act and make adaptive decisions (Yates Citation2014; Holland Citation2017; Leck and Simon Citation2018; Pradhan Citation2018; Stock, Vij, and Ishtiaque Citation2021).

Despite such long-standing empirical and theoretical inquiry, there remains a lack of consensus on the use of the terms level and scale, as they are often used interchangeably or haphazardly, even in critical scholarship. Early on, Moore (Citation2008) expressed concern that scale had “become an unwieldy concept laden with multiple, contradictory and problematic meanings” (203). The configuration of levels and scales presents particular theoretical challenges. Some scholars have distinguished scales as the “spatial, temporal, quantitative, or analytical dimensions used by scientists to measure and study objects and processes” (Gibson, Ostrom, and Ahn Citation2000, 219) and levels as “units of analysis that are located at different positions on a scale” (Cash et al. Citation2006, 3). We find this differentiation useful as it allows, as Cash and colleagues (Citation2006) showed, for researchers to conceptualize broad dimensions of decision making while identifying specific levels organized by areas and political units.

Nonetheless, a number of human geographers have contested so-called vertical theorizations of scale, arguing they portray a nested hierarchy of units and spaces within static boundaries (Jones Citation2017). Early on, Marston and colleagues (2000, Citation2005) contended that scale was not a vertical structure comprised of the local, regional, national, and global. Instead, it entails complex interrelations that hinge on formal structures of governance, the everyday practices of social actors, and the power that circulates across and between them. Yet, Leitner and Miller (Citation2007) argued that abolishing spatial and scalar thinking altogether would have problematic and unproductive implications. By identifying spaces and jurisdictions in place, scholars are better able to pinpoint existing power imbalances and visualize alternative structures and methods of resistance.

The Politics of Scale

A substantial body of geographical scholarship has focused on the politics of scale; it investigates how decision-making entities are constructed by a “diverse set of actors engaged in political transformations” (Jones et al. Citation2017, 142). Central to this inquiry is the notion that scales are “non-inherent, and determined through political, economic, and social processes characteristic of a particular social system” (Blackburn Citation2014, 103). Like scales themselves, boundaries or “borders” between scales emerge, shift, and disappear as societies and individuals uphold or reject them according to social mobilities over time (Cobarrubias Citation2020). Marston (Citation2000) offered a notable example in the turn-of-the-century United States when (middle-class) women redefined their identities. Through social movements and popular domestic practices, women were able to assert their roles as “female citizens” (Marston Citation2000, 235) and carve out new spaces in municipal, state, and federal government affairs.

Other work demonstrates how scale is manipulated in contexts of disaster risk management and adaptive decision making. Marks and Lebel (Citation2016), for instance, found that disputes over scalar arrangements for managing floods in Thailand were used to both uphold and contest efforts to decentralize power. Competing narratives allowed national leaders to assert their authority over local organizations while communities blamed state politicians for flood damage. Moreover, as shown in the alignment of UK urban adaptation strategies with global science-policy agendas (Kythreotis et al. Citation2023), boundaries between levels of decision making can be dismantled when resources and flows of information become more accessible to cities.

Coming to grips with scales and boundaries as social and political (re)productions widens the analytical lens and allows researchers to assess power relations that shape governance in climate change adaptation (Pradhan Citation2018; Garcia et al. Citation2022). Nonetheless, how levels and scales of adaptive governance are infused by dynamic and embodied power relations remains poorly understood. As Yates (Citation2014) recommended, efforts to democratize adaptation require moving beyond conceptualizations of fixed hierarchies and addressing power processes within, between, and across scales.

The Politics of Adaptation

The role of power and politics in shaping adaptation processes across geographical contexts is now well documented (Eriksen, Nightingale, and Eakin Citation2015; Tschakert et al. Citation2016; Harris, Chu, and Ziervogel Citation2018). The term politics of adaptation refers to the “political interactions shaping adaptation efforts” (Holland Citation2017, 393) and decision making built into a composite of everyday actions, policies, and interventions (Gonda Citation2019). Within institutionalized structures of governance, technocratic and top-down approaches to adaptation are easily dominated by powerful actors who assert and control agendas (Nightingale Citation2017). By contrast, the micropolitics of adaptation denotes the informal political processes and interactions that shape adaptive decision making at household, community, and district levels (Tschakert et al. Citation2016). Social actors reproduce broader power relations in their everyday lives through norms and behaviors that maintain existing inequalities and risk engendering discriminatory adaptation outcomes (Eriksen, Nightingale, and Eakin Citation2015; Tschakert et al. Citation2016).

Just as scales of adaptive decision making are constructed through social and political relations, subjects in adaptation are produced through everyday interactions between social actors and external modes of governance (Eriksen, Nightingale, and Eakin Citation2015). We align with early work by Foucault (Citation1982) to conceptualize the “subject” as embodying both a person’s internal configuration of their identity and the process of being subjected by powerful actors and institutions of authority. Evidence shows how groups and individuals are brought into complex relations of power that influence who benefits from adaptation and who is sidelined (Eriksen, Nightingale, and Eakin Citation2015). For example, flood barriers in Lagos, Nigeria, are geographically positioned to protect the wealthy while endangering the poor, including Ogu Indigenous communities subjectified as racially and economically inferior (Tuana Citation2019). Such uneven subject making positions specific individuals as seemingly less deserving and less capable of protecting their lives and livelihoods (Yami et al. Citation2019).

The role of discourse in (re)producing subjects is not new, including when actors strategize adaptation options across levels of decision making. For example, Gay-Antaki (Citation2020) illustrated how essentialist narratives of women in meetings of the Conferences of the Parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change outflanked alternative perspectives and underprioritized gender equality in deliberations over climate policy. Dominant discourses in decision making, as Manuel-Navarrete and Pelling (Citation2015) argued, are central to the exercise of power as they work to “keep political subjects aligned along [… an agenda-driven] pathway” (560). The discursive construction of authority and subjects in decision making might paradoxically undermine the claimed objectives of institutions tackling socioecological problems as they inadvertently (re)produce sociopolitical barriers to adaptation and well-being (Manuel-Navarrete and Pelling Citation2015).

Some actors in adaptation, however, find openings for using the fluidity of power to strategically remold their subjectivities as “powerless” individuals (see Tschakert et al. Citation2016; Van Aelst and Holvoet Citation2016). Nuanced investigations into the politics of adaptation across levels and scales of decision making make it possible to trace how agency and power are mobilized on the ground (Arora-Jonsson Citation2017; Kaika Citation2017). This entails close attention to how vulnerable populations harness political capabilities and contest adaptive decision making (Holland Citation2017), thereby becoming part of climate justice struggles (Porter et al. Citation2020). Although there are clear similarities between framings of how subjects and scales are (re)produced in adaptation processes, advances on the politics of scale and the politics of adaptation have remained largely separate in human geography and climate change debates.

Power in Multi- and Cross-Level Adaptive Decision-Making Processes

Although the discursive and material construction of subjects and scales substantially influences how adaptation is put into practice, a complex web of interlocking power relations and co-constitutive structures of oppression—Osborne (Citation2015) referred to this dynamic as kyriarchy—ultimately determines how adaptive actions materialize on the ground. So far, only limited attention has been paid to how Foucault’s conceptualization of power as dispersed, embodied, and circulating intersects with sociospatial power hierarchies in state-driven adaptation policymaking, planning, and implementation. This is undeniably a formidable task.

Some scholarship has examined how power differentials and competing policy interests are maneuvered and, at times, (re)negotiated. Funder and Mweemba (Citation2019), for instance, showed street-level bureaucrats in Zambia following state agendas while discretely prioritizing adaptation measures that align with community-level needs. In Kenya, as Smucker, Oulu, and Nijbroek (Citation2020) illustrated, subnational governments successfully use informal, cross-level, and collaborative arrangements to undertake adaptation, disaster risk reduction, and land restoration. These and other examples offer glimpses into the fluidity and maneuvering of power, as scalar hierarchies and relational webs can be challenged or even reconfigured.

What is lacking is an explicit focus on how socially, economically, or otherwise disadvantaged groups navigate power in politics and policymaking to strengthen their adaptive capacities. There is no doubt that multilevel decision-making processes are rife with power asymmetries that serve influential actors while silencing those at lower levels of the pecking order (Hamilton Citation2018). For instance, this happens when institutional experts disregard aggrieved citizens’ claims of environmental injustice as lacking scientific grounding, thereby rendering their experiences illegitimate (Holland Citation2017). Even when governing institutions seek the participation of community-level actors in decision-making processes, they might inadvertently reinforce entrenched inequalities. For instance, as demonstrated by Nagoda and Nightingale (Citation2017), social hierarchies in Nepal permeated adaptation-related committee meetings and stifled input from those most vulnerable to climate variability and change.

These and other pieces of evidence suggest that power travels in ways that both entrench existing hierarchies and reshape scalar arrangements (Scoville-Simonds, Jamali, and Hufty Citation2020). As a Foucauldian understanding of power as being everywhere would suggest, pursuing fluid politics of scale can expand adaptive decision making. What remains underexplored is how sociospatial hierarchies of power are maintained, for instance through elite capture. This coexistence between fluid and entrenched power could well exacerbate rather than reduce practices of silencing in adaptive decision making and undermine institutional approaches aiming to embolden disadvantaged citizens in the framing and enacting of just climate solutions (Schapper Citation2018). Such tensions and pushback can stifle fair procedures and shelve the recognition of stakeholder values and identities. This study aims to address this contested space with a case study of adaptive decision making in Ghana.

Case Study Background and Context

In many ways, Ghana has led the way for political change in sub-Saharan Africa since independence in 1957 (Haynes Citation1993). Following the 1993 Local Governance Act, the country shifted to a decentralized system of administration, aiming to delegate more power to local authorities and engender more democratic policy and decision making. However, competing political agendas, institutional arrangements in disarray, and constraints on resources continue to hamper grassroots development initiatives (Fridy and Myers Citation2019). Moreover, climate change exerts additional pressure on authorities as most rural residents rely on agriculture now threatened by increasing temperatures and rainfall variability, and more intense drought and flooding events (Abbam et al. Citation2018). Hence, the central government has amplified efforts to support the agricultural sector in adapting to these challenges.

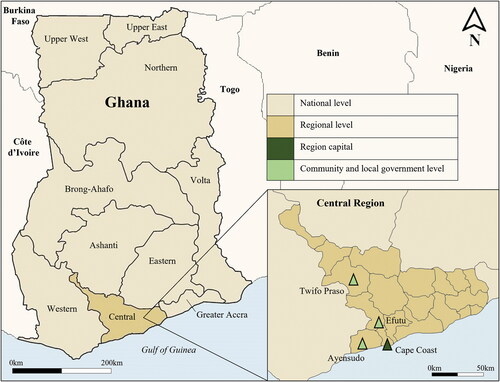

For this study, the research team chose multiple spatial and jurisdictional levels of adaptive decision making to establish scope and collect data (). In addition to community, local government, regional, and national levels, we also assess international influences on adaptation initiatives, for instance NGOs and donors. Although these levels may well be situated on a vertical hierarchical scale mirroring a top-down political structure, we approach them here as fluid entities that shift, intersect, and overlap with social and political mobilities. Moreover, we recognize the designated levels do not represent a comprehensive picture of Ghana’s adaptive efforts, but rather parts of a complex web of actors, networks, and interrelations.

Figure 1. Study area in Ghana’s Central Region with spatial and jurisdictional levels of policy and decision making.

Two key documents have outlined the government’s national approaches to climate change adaptation: the National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy (2012) and the Ghana National Climate Change Policy (2013). In the context of agriculture, adaptation plans typically centered on technological innovation, water management, agricultural diversification, alternative livelihoods, and research and education (Ghana Environmental Protection Agency Citation2015). Major challenges for meeting adaptation targets were inadequate infrastructure, limited capacity for human resources, unsound subregional networks, and inadequate financial resources (United Nations Environment Program and United Nations Development Program Citation2012). In addition, strategy and policy documents note gendered inequalities that inhibit women’s access to resources and opportunities to adapt. More recently, Ghana’s National Adaptation Plan Framework (Ghana Environmental Protection Agency Citation2018) foregrounded the need for shared, participatory decision making in adaptation planning and efforts that respond to social inequalities. Yet, to date, national adaptation approaches have largely overlooked the consequential roles of politics and power in controlling adaptation agendas. This potentially perpetuates systemic inequalities that further marginalize rural farmers.

A case in point is Ghana’s Central Region () where most residents live in rural communities. Many work in food cropping, forestry, and fish farming, and services, sales, and creative trades, primarily in urban centers, provide alternative occupations (Ghana Statistical Service Citation2013). Local governance structures are deeply entangled in community-level politics as development initiatives often comply with informal structures of power and authority embedded in traditional chief-based systems. For instance, customary land tenure arrangements divert resources and opportunities for expansion to high-status actors, whereas others, particularly women, are often confined to working on small plots for household consumption and petty trade.

Three rural farming communities in the Central Region were chosen for data collection on community and local-level perspectives on internal and external processes of power that affect farmers’ opportunities for adaptation (). Most residents across the study sites have limited access to electricity and running water and are crop farmers for subsistence and commercial benefit. Local assemblies and agricultural departments liaise between residents and the central government and offer extension services. The dominant ethnicity is Akan, with a small percentage of non-Akan migrants having relocated from other parts of the country. Residents are primarily Christian, with a small number of Muslims and individuals without religious affiliation. All three communities embody largely conservative social and political structures, with men representing the majority of household heads (over 80 percent) and local unit committees led by resident chiefs and elders.

Methods

Data for this study were collected between February 2018 and April 2019 during five months of field work over two seasons. The lead researcher, with assistance from a Ghanaian collaborator (third author), conducted individual interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) with 122 participants involved in climate change adaptation policy and decision making across community, local government, regional, national, and international levels ().

Table 1. Participant distribution across research activities by level of decision making, community, and gender

During the first field work phase, community leaders and elders helped the research team to recruit farmers over the age of eighteen for participation in individual interviews (forty-one) and FGDs (sixty-nine participants, nine groups). Their median age was forty-nine, much higher than in regional census data. This was due to many younger community members having migrated to urban centers in search of alternative employment. Discussions lasted for up to two hours and were conducted with assistance from the third author who is fluent in Akan.

During the second field work season, interviews with six practitioners and representatives working in nearby government assemblies and agricultural extension services were arranged via contacts with connections to local authorities. These interviews took up to one hour and were conducted in English, with translation where needed.

Finally, six interviews were conducted with international, national, and regional scholars affiliated with universities and research institutes who work (or have worked) in climate change adaptation research, policy, and intervention in Ghana. At the national level, one respondent had also been a practitioner on agricultural adaptation projects. These interviewees were identified through the research team’s networks and Ghanaian collaborators. Discussions went for up to one hour in English, online, over the phone, or face-to-face.

We acknowledge the small albeit vital sample size of international, national or regional, and local-level respondents, several of whom did not work as adaptation practitioners and none for an NGO. This could temper our understanding of adaptation as a (power-laden) process. Scant NGO presence in the study areas, staff shortages in local government departments, and poor contactability of prospective interviewees made the recruitment of additional nonfarmers difficult.

Interview questions were adapted according to differences between participants across levels of decision making. Specifically, contextual grounding of questions was customized to acknowledge the reality of uneven educational, cultural, and institutional backgrounds. Topics covered in the interviews are outlined in .

An inductive approach was used to code FGD and interview transcripts into overarching nodes using NVivo. Nodes were determined as they emerged throughout the coding process, with some predetermined based on field work insights. After several rounds of content analysis, cross-checking, and fine-tuning nodes, information was organized into three main themes: (1) planning and strategizing across levels of adaptive decision making, (2) tensions and agendas, and (3) power and politics in adaptation. Graphs were generated to visually demonstrate similarities and divergences in stakeholders’ understandings of and experiences with specific aspects from the second and third themes.

In addition, a discourse analysis grounded in Foucault’s (Citation1980) seminal work on power and discourse (Sharp and Richardson Citation2001) was applied to the same transcripts to go beyond assessing “who said what” and investigate how discourse influences agendas and opportunities with respect to adaptation. First, transcripts were coded manually and the text was organized into categories representing the (re)production or contestation of dominant subjectivities (subjects) and boundaries between levels of decision making (scales). The coded text then underwent a second round of digital coding into categories representing discursive mechanisms for “building the world” (Gee Citation2011), for instance, through power building (depicting actors or jurisdictions as powerful, powerless, or as asserting power over others) and compassion and sensitivity building (toward specific actors who face injustices). Nodes used during both rounds of coding were determined in accordance with discourse analysis tools from the literature (Gee Citation2011) and critical scholarship on the politics of adaptation and scale (see Literature Review). The context, use of language, and emotions expressed verbally in interviews and FGDs were closely examined to streamline the coding process. Because interviews with farmers were recorded in Akan and later translated into English, their emotions could not be analyzed to the same degree and depth as those in transcripts and recordings with English-speaking scholars and practitioners.

This multipronged analysis offers a vital glimpse into how power operates within and across levels of adaptive decision making, and how specific actors uphold or contest the material and discursive construction of subjects and scales. These insights make it possible to comprehend power as more fluid than a strictly hierarchical structural arrangement would suggest. Nonetheless, as the data show, scalar institutional structures in Ghana remain pervasive and self-reproducing in practice. To avoid reproducing a top-down, nested hierarchy, we aimed to trace how power travels within and across levels and scales in ways that are neither vertical nor unidirectional. This meant treating boundaries as porous to capture fluidity, whenever possible, while accepting boundaries as persistent scalar structures where needed. This tension points to a long-standing challenge for critical scholars to develop new methodological (and representational) tools for exposing the inequitable structures that permeate decision-making processes while accounting for the ambivalence of power (Butler Citation1997).

Results

The analysis of the FGDs and interview data provides novel insights into how power asymmetries are mobilized in adaptation landscapes and how disadvantaged actors, who are supposed to be the beneficiaries of Ghana’s adaptation policy and action, are relegated to the lowest ranks of decision-making hierarchies. In the following two sections, drawing from our content analysis, we first present similarities and divergences in the ways participants comprehend and engage with complex tensions and political agendas in adaptation. We then demonstrate how these processes intersect with politics and power dynamics that flow within and across levels of decision making. In the final results section, drawing from our discourse analysis, we show how actors are brought into fluid and circulating power relations and the discursive (re)production of subjects and scales in adaptation.

Tensions and Agendas Across Levels of Decision Making

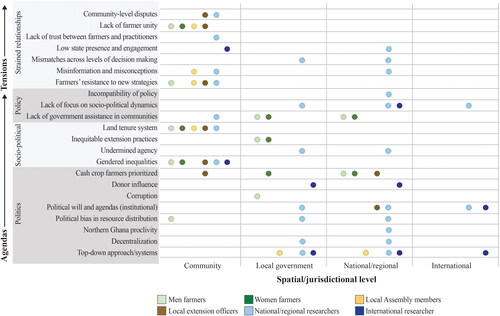

Participants described complex tensions and political agendas that could explain conflicting accounts of the adaptation response measures available to farmers. shows these specific tensions and agendas that constrain the recognition, and by extension, the participation of rural farmers in adaptive decision making. They are categorically grouped under strained relationships, policy, sociopolitical aspects, and politics, with various adverse effects across spatial and jurisdictional levels. Numerous tensions related to strained relationships between social actors and jurisdictions and agendas were described as deeply entangled within biased institutional procedures and inequalities.

Figure 2. Tensions and agendas constraining adaptation and adaptive decision making in Ghana, grouped into (1) strained relationships, (2) policy, (3) sociopolitical, (4) politics. Colored circles indicate which respondent groups described specific tensions or agendas. The horizontal positioning of the colored circles shows the level(s) of decision making affected by these dynamics.

Tensions between rural communities and institutions were viewed by respondents as detrimental to the cohesive and effective management of adaptation projects as they fortify perceived boundaries between levels of adaptive action. A noteworthy example is the lack of trust between farmers and practitioners such as extension officers and NGO workers, often related to inadequate project delivery in communities. One scholar recounted an NGO’s experience attempting to launch a savings and loans scheme:

They go and sensitize people to form groups and they don’t go there again. So the next time you ask [farmers] to form another group, nobody will mind you. So it’s a long history of distrust that has caused that kind of situation … . (National researcher/academic 1)

Some people just don’t like to learn. When they hear of a new method, instead of asking how it is done, the procedure, they will not. They … like to do it on their own and they will get it wrong. (Farmer, man, thirty-nine years old)

Political agendas were outed as rampant across adaptation policy and decision-making spheres, with adverse consequences for the representation of marginalized actors. For example, a top-down system of governanceFootnote2 entrenches the biases of governing authorities and undermines local and regionally driven initiatives, as evidenced here:

Administratively, they have decentralized but if you look at … a district officer, who they’re responsive to, decentralization actually hasn’t changed anything because the district officers aren’t elected locally and they’re not responsible locally. They’re appointed by Accra [the capital]. As a result, a district officer is always going to do what Accra wants over what the local population wants. (International researcher/academic)

It’s not sufficient … . We don’t have a say. They are providing for us so they say they want to give you this much and that is it. We can’t say anything. They are providing so they determine how much to give. (Local Assembly member 1)

This factory has been built almost four years but there’s no sugarcane to process. Why? Because in that vicinity there [was] no feasibility study. Now the factory has been closed almost a year. (National researcher/academic 2)

At times, the underrepresentation of community-level actors in adaptive planning was attributed to political agendas to promote economic growth. Cash crop growers are often prioritized in national policies that allocate improved seeds and fertilizer to those farming at commercial scales, as indicated by one local practitioner and several farmers (15 percent). State officials went so far as to rebuke a local agricultural department after it promoted sustainable rubber farming in place of cocoa plantations:

The government was saying they weren’t happy that … we are discouraging the growing of cocoa. Cocoa is the major export crop of the nation. So there is conflict there. (Local extension officer 1)

These agric[ultural] extension officers, every year they will come here and give us promises. Sometimes when you invite them they will not even come. Everything now is about corruption. If you don’t give them tips, they won’t come to your farm. (Farmer, woman, forty-eight years old)

Overall, the tensions and agendas depicted here suggest fractured relationships and prejudiced treatment by governmental offices that remain pervasive in adaptation policy and decision making. Although these examples merely scratch the surface of the multitude of complex interrelations that shape adaptation in practice, they highlight the material construction of subjects and scalar arrangements that constrain opportunities for farmers to act in response to the climate crisis. Identifying such dynamics, even if seemingly bounded, is crucial for exposing inequitable structures and unjust procedures that are all too easily hailed as beneficial adaptation.

Power and Politics in the Context of Adaptation

The tensions and agendas regarding adaptive decision making described earlier are inevitably tied to politics and uneven power dynamics. Structural hierarchies are maintained by everyday professional and personal interactions within and across spatial and jurisdictional levels. Still, processes of power are never fixed; rather, they transcend boundaries between people, places, and jurisdictions. Here, we illustrate this skewedness in the movement of power and how it can work to either entrench existing power hierarchies or allow adaptation actors to (re)negotiate scalar boundaries and empower the agency of rural farmers to take adaptive action.

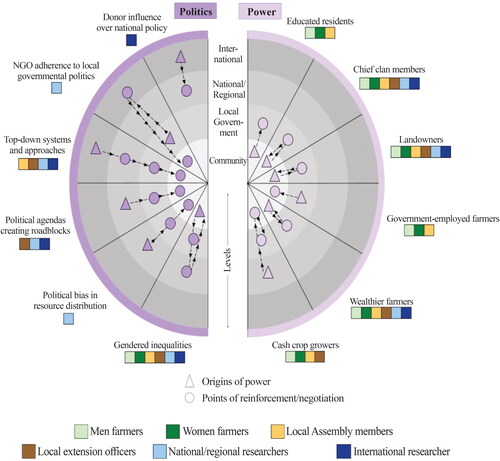

Such “power geometries” () illustrate how power travels in Ghana’s adaptation landscape, moving between the power held by ordinary citizens to politics and policymaking at local, national, and international levels. Although it is a simplified representation of how power operates, the visual tracing of power movements helps to locate openings for subverting the systemic marginalization of vulnerable citizens in decision-making processes.

Figure 3. Power geometries illustrating how politics and power dynamics travel across and between spatial and jurisdictional levels of adaptive decision making. The purple shapes demonstrate the specific level(s) of decision making from which authority and influence originate (triangle), and the points at which power asymmetries are entrenched or (re)negotiated (circle). Arrows show the reach of power and politics, and the direction(s) in which they travel. The green to blue colors show which politics and power dynamics were described by the various respondents.

Participants’ accounts of power and politics that move within and across levels of decision making highlight multiple, intersecting, and at times juxtaposing spheres of influence that govern how power asymmetries in adaptation processes are entrenched and (re)negotiated, in three distinct ways.

First, Ghana’s top-down system of authority allows international donors to have a strong influence over how national adaptation policy takes shape. This demonstrates how cross-scale power relations can solidify the structural hierarchies in adaptation processes. State-level decision making reinforces global agendas by prioritizing regions and projects anticipated to yield rapid results, such as those involving large-scale export crops. This curtails space for locally driven initiatives to situate adaptation efforts within the lived realities of rural farmers:

The Ghanaian government is very, very influenced by the donors. If the donor wants to pay for X, the Ghanaian government wants to do X. When you’re operating in a top-down environment that means that in some ways you’re dealing with top-down from whoever is funding, all the way down to the community level where stuff is just getting dropped in the communities. (International researcher/academic)

The cocoa farmers are more privileged than the rest of the farmers in this community in the sense that any time there are fertilizers the suppliers send it to them directly. So we don’t receive such. (Farmer, woman, fifty-three years old)

Second, as a juxtaposing example, local authorities can (re)negotiate and even override top-down decision making through their interactions with farmers and NGOs. As such, power is seen as circulating in fluid ways, reshaping hierarchies in adaptation. For instance, local assemblies grant external organizations access to communities and connect them with residents. Consequently, local-scale agendas and politics maneuver vertical power structures by influencing who is prioritized and who may be left out of adaptation interventions:

The NGOs … seem to be independent [but] for some reason they have to play along with local politics and rules to survive … . While the NGO is in the district or within the local government area, the local government authorities may have power to negotiate what can be done and what cannot be done. (National researcher/academic 1)

Even if you are fortunate to get little [farming resources], it’s been politicized. So, if you belong to their party, you are going to get something. If you don’t, then you will be left waiting. (Farmer, male, fifty-two years old)

The third, interlinked sphere of influence relevant to the movement of power in adaptation relates to the role of community-level micropolitics in influencing how and when local practitioners engage with farmers. Farmers who own large portions of land decide which adaptation strategies are used on their farmed and rented-out plots. On the one hand, this power advantage was strategically employed to maintain community-level hierarchies and “discipline” (in a Foucauldian sense) less privileged actors. On the other hand, wealthier landholders and those with chief clan lineage were able to stipulate discounts and subsidies on resources from local practitioners. This shows how power held by the same individuals can transcend scalar boundaries, magnifying their wealth and cementing their control over available adaptation options:

When the Government brings fertilizer, for instance, you realize that the rich farmers … amass all the fertilizers for themselves. They convince the caretakers to give [resources to] this farmer, and not [to another farmer]. So they are very influential. (Farmer, woman, fifty-two years old)

In summary, power and politics are omnipresent in adaptation efforts, ranging from socially embedded power differentials to the assertion of long-standing biases in global–national interactions. Participants’ accounts illuminate how power moves within and across levels, often ensconcing existing hierarchies. Yet, it also circulates in ways that are neither vertical nor one-directional. Such nuanced snapshots of traveling power highlight the fluidity of subjects and scalar arrangements that are (re)produced and (re)negotiated within the shifting nature of adaptation. Investigations that trace such movements are essential for locating openings to subvert multiscalar systems of domination for enhancing the adaptive capacities of disadvantaged citizens.

(Re)producing Scales and Subjects Through Dominant Discourse

In addition to the sociopolitical and institutional dynamics examined so far, insights from our discourse analysis reveal how the participants themselves were implicit in perpetuating or challenging dominant narratives that discursively position vulnerable groups and individuals as second-rate citizens. The fact that specific subjects become (re)produced in adaptation only reinforces perceived boundaries between spatial and jurisdictional levels of decision making. At the same time, actors use insurgent speech or subtle verbal contestations to push back on dominant yet problematic narratives. Hence discourse can be used to both mobilize power and challenge scalar positionings. As noted by Harris and colleagues (Citation2018), power dynamics and political agendas that pervade adaptation processes are constantly upheld, negotiated, and contested by the social and professional actors entangled within them.

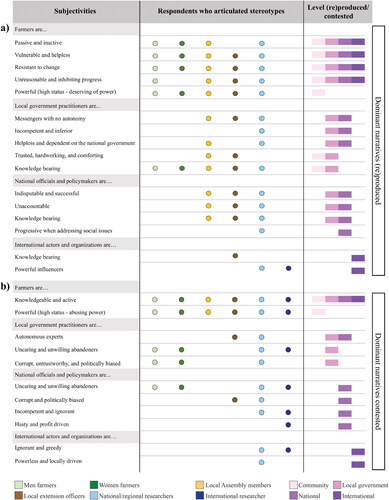

Here, we pinpoint and visualize () instances in which respondents discursively (re)produced specific subjects as well as moments when such subject making reinforced or contested boundaries between levels of adaptive decision making. In making these moments of (re)production visible, we shed light on the inner workings of domination, subservience, and agency that nourish or inhibit inclusive adaptive responses and the rights and aspirations of otherwise sidelined groups. Moreover, by demonstrating how discursive configurations of subjects and scales are mutually reinforcing, we advance current understandings of the politics of adaptation and the politics of scale as co-constitutive. In the following two sections, we first demonstrate the ways in which actors across levels engaged in narratives that reassert Ghana’s hierarchical system of decision making. We then illustrate how, at times, the same actors verbally challenged existing structures by pushing against pervasive subjectivities and contesting scalar hierarchies.

Figure 4. Subjectivities that (A) (re)produce, or (B) contest dominant narratives that perpetuate power asymmetries and boundaries between levels of adaptive decision making. Colored circles indicate which respondent groups (by category) articulated particular subjectivities. The level(s) of decision making (re)produced or contested through such engagements are shown on the right.

(Re)producing Power Asymmetries. As shown in , respondents across levels reinforced existing power asymmetries through their descriptions of dominant actors. For example, some portrayed international NGOs and donors as “powerful influencers.” This risks undermining the government’s sovereignty and capability in driving policy agendas and protecting their citizens. Others reasserted the scalar positioning of global institutions, including large NGOs who they admired, as key actors in adaptation planning and action. Similarly, the central government’s control over resources and adaptive decision making was discursively condoned by most national and local-level respondents. In particular, practitioners were visibly uncomfortable discussing institutional political dynamics, agendas, and deficiencies. One local Assembly member, who acted as a liaising officer between farmers and external governing bodies, appeared worried after criticizing the bureaucratic nature of the country’s adaptation solutions. He immediately rescinded claims of officious procedures and praised the opportunity to work for the government:

You are working for the government … and Ghana is very bureaucratic. [Some] people will say we are not working but it’s not that. But the work is good. It’s good work. You don’t get any other one. … We are praying. (Local Assembly member 2)

As an individual I cannot do anything because the government is superior. I mean, how can I just walk to the government and say we want this, we want that? (Farmer, man, sixty-six years old)

You can’t really say or do anything … . Every four years there might be a [political candidate] change. So when they come and tell us “we’re going to do this, we will do that” … , they don’t do it so there’s nothing that we can do as farmers. (Farmer, man, fifty-seven years old)

At times, farmers also reproduced intracommunity power dynamics and hierarchies. More than half of these respondents, particularly middle-aged men, displayed subservience toward powerful actors. Senior, educated, wealthy, and land-owning farmers, as well as political figures, cash crop growers, and those with clan lineage were all described in ways that implied righteous authority and leadership. In particular, dutiful portrayals of senior men as movers and shakers of community and household adaptation uphold social contracts that position them as eminent decision makers:

Here, if you are a leader or if you are of age and you are able to address the needs of the people they respect you. They give you that maximum power or support. But if you don’t address the issues of the people, you are not regarded and respected in this community. (Farmer, woman, forty-two years old)

Some people have an education background so they can use that vision. But those who have not attended anywhere don’t have any background of education. Those who have education, they can achieve a lot. (Local Assembly member 3)

Contesting Dominant Narratives. Although most respondents across levels were complicit in upholding hierarchies of adaptive decision making, several subtly and some forthrightly contested dominant narratives and existing structures. The latter reveals that the fluid and circulating nature of power as discourse can indeed be mobilized to (re)negotiate existing scalar hierarchies. At times, such contestations arose through direct criticism of governing authorities. For instance, government-led assistance for adaptation was depicted as scarce or nonexistent, especially by farmers (88 percent) who portrayed local and national-level officials as “conscious abandoners.”

Politically driven practices that erode well-intentioned policy and research were also denounced in conversations with national and regional-level scholars. Some academics fervently challenged dominant narratives and scalar arrangements that position government jurisdictions as indisputable decision makers:

There is the Planting for Food and Jobs Program which is a political program. Sometimes our big farmers are prioritized when it comes to these issues. You may need a fertilizer but you won’t get access … if you do not belong to their political party. (National researcher/academic 4)

There are some investments that we channel resources to in the same agricultural sector. If we had done it through the agricultural extension service, we would have had a better result. … For me, those on the ground should be the focus. Those on the ground doing the work. (National researcher/academic 1)

We don’t have to assume that … they are passive actors sitting down for the climate to kill them. They are very active, they make decisions based on rational choices and then they know what is good for them. (National researcher/academic 1)

With respect to intracommunity power dynamics, some respondents contested traditional hierarchies that further marginalize rural farmers through their anomalous views of powerful residents. Several participants depicted landowners, chief clan members, and wealthier farmers as “powerful exploiters” who use their authority as a coercive tool to control adaptation options. One scholar criticized land tenure systems that prevent disenfranchised residents from undertaking adaptive actions:

Access to land is surrounded by power play. Certain types of people cannot own land. … Those who are connected to, or who have political connections … will determine what access you have to combat climate change. (National researcher/academic 4)

Even when you have an idea … that you think will help the household or the community, [the community] won’t take it in because you don’t have money. If you don’t have money … you are seen as good for nothing. Here, it’s about the rich. It’s about money. (Farmer, woman, sixty-eight years old)

Discursive efforts to push back on dominant narratives, such as those presented here, signal the agency of diversely positioned actors to confront scalar hierarchies and pervasive subjectivities that sanction unequal representation in adaptive decision-making processes. Admittedly, moments in which groups and individuals use speech to challenge oppressive structures are spatially and temporally confined. Nonetheless, they provide important insights into when and how verbal contestations can open new spaces for subverting, and possibly dismantling, unjust ideologies, norms, and practices.

Discussion and Conclusion

Insights into the scalar elements of adaptation underscore the need to move beyond conceptualizations of fixed hierarchies to address power processes within, between, and across scales (Yates Citation2014). A geographic lens attuned to the fluid and scalar dynamics of power has long been overdue in critical adaptation scholarship. Our study demonstrates a few effective examples that epitomize Foucault’s (Citation1980) notion of power as traveling, maneuvering, and ever circulating while also remaining a constant, here in Ghana’s hierarchical landscape of adaptive decision making. We apply this notion of power to expose how subjects and scales are constructed via discursive and material processes that influence state-driven adaptation policymaking, planning, and implementation. In doing so, we attest to Osborne’s (2015) conceptualization of adaptation as embroiled in a dynamic web of interlocking power relations and co-constitutive structures of oppression.

Despite the obvious parallels in their focus on power, analyses of the politics of adaptation and the politics of scale have remained largely separate in the climate change adaptation literature. We bring these two overlapping strands of thinking together to show how actors across levels are entangled in complex relations of power and (re)produce subjects and scales in adaptation. Some scholars have scrutinized cross-scalar power dynamics that inhibit marginalized actors from acting in the face of environmental threats, for instance Blackburn (Citation2014) in the context of disaster risk governance in Jamaica. We advance current understandings of how such power asymmetries are mobilized through our examination of the discursive subjectification of vulnerable groups as powerless and incapable, and how this keeps disadvantaged actors at the lowest ranks of decision-making hierarchies. Nuanced investigations of cross-level and cross-scale operations of power and (re)production open up space to make visible both blatant and seemingly trivial processes of disenfranchisement as well as agency that shape the capacities of vulnerable actors to effectively respond to and prepare for climate change. They also enable new spaces to envision and experiment with subversive political interventions that address persistent inequalities in climate change adaptation.

Scholars investigating the disproportionate effects of climate change have made great strides in reimagining conceptualizations of justice. Such novel visions of climate justice, driven largely by insights from urban adaptation, start from the premise that procedural and recognitional injustices inflict “damage on both oppressed communities and the image of those communities in larger cultural and political spheres” (Chu and Michael Citation2019, 141). Our study provides nuanced snapshots of interlocking structures of oppression in Ghana that could erode procedural justice with respect to rural actors’ contributions to decision making.

To overcome such obstructions, proponents of more just visions advocate for radical shifts in focus, to move from climate apartheid (Tuana Citation2019) and climate gentrification to emancipatory climate justice that recognizes differential risk claims and invests in the capabilities of the marginalized and oppressed (Anguelovski and Pellow, cited in Porter et al. Citation2020). Reimagining climate justice also entails efforts to scrutinize processes of othering that are patronizing and vilifying, from the less-than-human to more-than-human entities that bind us humans together (Tschakert et al. Citation2020) and pragmatic ways to decolonize adaptation. The latter consists of acknowledging the power of Indigenous (and other historically dispossessed) people to decide for themselves “what is valuable, what is threatened, which losses matter, and what should be done about this” (Naarm/Birraung-ga et al., cited in Porter et al. Citation2020, 318).

The challenge is not only to expose injustices, but to (re)design operational procedures to increase people’s abilities to contest unfair and dehumanizing treatment and steer processes that affect their lives (Bailey and Darkal Citation2018). First, this means bringing actors who are not recognized into political processes and “treating them as full partners … worthy of equal respect and esteem” (Holland Citation2017, 395). For Pellow (Citation2017), this means committing to an ethics of indispensability. Collaborative governance between national and local governing bodies and efforts to dissolve vertical hierarchies, as Leck and Simon (Citation2018) argued, could help break down obstacles to inclusive decision making and equitable adaptation outcomes. This would also allow for skills and resources from diverse institutions and stakeholders to be harnessed, collectively. Such desirable results seem achievable only when national governments acknowledge regional and local decision makers as agents of change, well positioned to mobilize local actors and co-produce “place-tailored solutions based on local knowledge” (Dabrowski Citation2018, 840).

Second, governing bodies would be well served to work more readily with communities so they better comprehend their vulnerabilities and capabilities as core ingredients for co-designing inclusive and procedurally just adaptation policies (Holland Citation2017). As Parsons, Fisher, and Nalau (Citation2016) illustrated, approaches that nurture a co-production of policy and decision making with rural actors who become more emboldened in everyday negotiations of adaptation are more likely to lead to inclusive and fair outcomes. Methods of co-production typically aim to redistribute authority in structural hierarchies to avoid undermining the political capabilities of vulnerable populations. Hence, they are less susceptible to strategic control or elite capture (Holland Citation2017), making it possible to go “beyond narratives of loss and victimization” (Shi Citation2021, 30) and prefigure much-needed pathways toward climate justice.

Such visions of hope established collectively between authorities, scholars attuned to operations of power, and community-level agents of change might seem like a far cry in times of climate crisis. Efforts to defeat procedural injustices across scales of climate change decision making, as Grove, Cox, and Barnett (Citation2020) warned, could nonetheless reproduce uneven representation. Moreover, scholarly efforts to increase the recognition of marginalized individuals and societies in how adaptation is planned, deliberated, and enacted have rarely gone beyond perfunctory attempts. Human geographers have a prominent role to play in confronting our complicity within exclusionary institutional practices, particularly in Global South contexts where the interests of underprivileged groups are too often obscured by multiple and interlocking axes of power. We conclude by calling for a climate justice agenda anchored in scalar politics, equipped to confront the complexity of power at work in the intersecting, fragmented, and contested fabrics of adaptive decision making. During a time of global uncertainty, finding respectful and responsible ways to empower the full range of human capabilities required for people to live safe and dignified lives is now more critical than ever.

Acknowledgements

This research would not have been possible without the generous and forthcoming contributions of the research participants, to whom we extend immense gratitude and deepest regards during these trying times. We would also like to thank our colleagues in Ghana, who played an integral role in facilitating rich and productive research relationships on the ground. In particular, we must thank Dr. William Boateng for his ongoing support and assistance. Finally, we extend warm thanks to Associate Professor Fay Rola-Rubzen and Emeritus Professor Lynette Abbott at the University of Western Australia for their feedback on this article and ongoing guidance as Alicea Garcia’s PhD cosupervisors.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Table 2. Content of discussions with actors at distinct levels of decision making

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alicea Garcia

ALICEA GARCIA completed her PhD with the Department of Geography and Planning at the University of Western Australia, Perth, Western Australia 6009. E-mail: [email protected]. Her PhD research investigated how entrenched processes of power and subject making determine pervasive social inequalities and differential capacities for societies and individuals to adapt to climate change. Her work spans critical scholarship on climate change adaptation, political ecology, climate justice, and transformation.

Petra Tschakert

PETRA TSCHAKERT is a human–environment geographer, applied anthropologist, and Professor of Geography and Global Futures at the School of Media, Creative Arts and Social Inquiry, Curtin University, Perth, Western Australia 6102. E-mail: [email protected]. She conducts research at the intersection of political ecology, climate change adaptation, livelihood security, and climate justice, with a focus on power dynamics, vulnerability, and inequalities. She combines critical social science insights with grounded, participatory methods for collective learning and social change, based on extensive experience working with rural populations in West Africa, mainly Ghana and Senegal.

Nana Afia Karikari

NANA AFIA KARIKARI is a Lecturer at the School of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Energy and Natural Resources, Sunyani, Ghana. E-mail: [email protected]. She is a sociologist with research interests and expertise in medical sociology, gender and sexuality, social policy, climate adaptation, rural sociology, sustainable development, and qualitative research methodologies.

Notes

1 Here, adaptive decision making refers to the procedures and interactions that underpin decisions related to adaptation across different spatial and jurisdictional modes of operation.

2 The shortcomings of efforts to decentralize power in Ghana are detailed in critical work by Fridy and Myers (Citation2019).

References

- Abbam, T., F. A. Johnson, J. Dash, and S. S. Padmadas. 2018. Spatiotemporal variations in rainfall and temperature in Ghana over the twentieth century, 1900–2014. Earth and Space Science 5 (4):120–32. doi: 10.1002/2017EA000327.

- Arora-Jonsson, S. 2017. The realm of freedom in new rural governance: Micro-politics of democracy in Sweden. Geoforum 79:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.12.010.

- Bailey, I., and H. Darkal. 2018. (Not) talking about justice: Justice self-recognition and the integration of energy and environmental-social justice into renewable energy siting. Local Environment 23 (3):335–51. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2017.1418848.

- Barnett, J. 2020. Global environmental change II: Political economies of vulnerability to climate change. Progress in Human Geography 44 (6):1172–84. doi: 10.1177/0309132519898254.

- Benson, M. H. 2010. Regional initiatives: Scaling the climate response and responding to conceptions of scale. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 100 (4):1025–35. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2010.497317.

- Blackburn, S. 2014. The politics of scale and disaster risk governance: Barriers to decentralisation in Portland, Jamaica. Geoforum 52:101–12. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.12.013.

- Brandstedt, E., and B. Brülde. 2019. Towards a theory of pure procedural climate justice. Journal of Applied Philosophy 36 (5):785–99. doi: 10.1111/japp.12357.

- Bulkeley, H. 2005. Reconfiguring environmental governance: Towards a politics of scales and networks. Political Geography 24 (8):875–902. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2005.07.002.

- Butler, J. 1997. The psychic life of power: Theories in subjection. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Cash, D. W., W. N. Adger, F. Berkes, P. Garden, L. Lebel, P. Olsson, L. Pritchard, and O. Young. 2006. Scale and cross-scale dynamics: Governance and information in a multilevel world. Ecology and Society 11 (2):1–13. doi: 10.5751/ES-01759-110208.

- Chu, E., and K. Michael. 2019. Recognition in urban climate justice: Marginality and exclusion of migrants in Indian cities. Environment and Urbanization 31 (1):139–56. doi: 10.1177/0956247818814449.

- Cobarrubias, S. 2020. Scale in motion? Rethinking scalar production and border externalization. Political Geography 80:102184. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102184.

- Dabrowski, M. 2018. Boundary spanning for governance of climate change adaptation in cities: Insights from a Dutch urban region. Environment and Planning 36 (5):837–55.

- Eriksen, S., A. J. Nightingale, and H. Eakin. 2015. Reframing adaptation: The political nature of climate change adaptation. Global Environmental Change 35:523–33. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.09.014.

- Foucault, M. 1980. Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings 1972–197, ed. C. Gordon. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Foucault, M. 1982. The subject and power. Critical Inquiry 8 (4):777–95. doi: 10.1086/448181.

- Fridy, K. S., and W. M. Myers. 2019. Challenges to decentralisation in Ghana: Where do citizens seek assistance? Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 57 (1):71–92. doi: 10.1080/14662043.2018.1514217.

- Funder, M., and C. E. Mweemba. 2019. Interface bureaucrats and the everyday remaking of climate interventions: Evidence from climate change adaptation in Zambia. Global Environmental Change 55:130–38. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.02.007.

- Garcia, A., N. Gonda, E. Atkins, N. J. Godden, K. P. Henrique, M. Parsons, P. Tschakert, and G. Ziervogel. 2022. Power in resilience and resilience’s power in climate change scholarship. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 13 (3):e762.

- Garcia, A., P. Tschakert, and N. A. Karikari. 2020. “Less able”: How gendered subjectivities warp climate change adaptation processes in Ghana’s Central Region. Gender, Place & Culture 27 (11):1602–27. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2020.1786017.

- Gay-Antaki, M. 2020. Feminist geographies of climate change: Negotiating gender at climate talks. Geoforum 115:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.06.012.

- Gee, J. P. 2011. How to do discourse analysis: A toolkit. London and New York: Routledge.

- Ghana Environmental Protection Agency. 2015. Ghana’s third national communication report to the UNFCCC. Accra: Ghana Environmental Protection Agency.

- Ghana Environmental Protection Agency 2018. Ghana’s national adaptation plan framework. Accra: Ghana Environmental Protection Agency.

- Ghana Statistical Service. 2013. 2010 population and housing census. Accra: Ghana Statistical Service.

- Gibson, C. C., E. Ostrom, and T. K. Ahn. 2000. The concept of scale and the human dimensions of global change: A survey. Ecological Economics 32 (2):217–39. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00092-0.

- Glass, M. R., and R. Rose-Redwood (eds). 2014. Performativity, politics, and the production of social space. New York and London: Routledge.

- Gonda, N. 2019. Re-politicizing the gender and climate change debate: The potential of feminist political ecology to engage with power in action in adaptation policies and projects in Nicaragua. Geoforum 106:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.07.020.

- Grove, K., S. Cox, and A. Barnett. 2020. Racializing resilience: Assemblage, critique, and contested futures in greater Miami resilience planning. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 110 (5):1613–30. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2020.1715778.

- Hamilton, M. 2018. Understanding what shapes varying perceptions of the procedural fairness of transboundary environmental decision-making processes. Ecology and Society 23 (4):1–10. doi: 10.5751/ES-10625-230448.

- Harris, L. M., E. K. Chu, and G. Ziervogel. 2018. Negotiated resilience. Resilience 6 (3):196–214.

- Haynes, J. 1993. Sustainable democracy in Ghana? Problems and prospects. Third World Quarterly 14 (3):451–67. doi: 10.1080/01436599308420337.

- Holland, B. 2017. Procedural justice in local climate adaptation: Political capabilities and transformational change. Environmental Politics 26 (3):391–412. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2017.1287625.

- Jones, J. P., III. 2017. Scale and anti‐scale. In International encyclopedia of geography: People, the earth, environment and technology, ed. D. Richardson, N. Castree, M. F. Goodchild, A. Kobayashi, W. Liu, and R. A. Marston, 1–9. Hoboken, NJ: John WIley & Sons.

- Jones, J. P., III, H. Leitner, S. A. Marston, and E. Sheppard. 2017. Neil Smith’s scale. Antipode 49:138–52. doi: 10.1111/anti.12254.

- Kaika, M. 2017. “Don’t call me resilient again!”: The new urban agenda as immunology … or … what happens when communities refuse to be vaccinated with “smart cities” and indicators. Environment and Urbanization 29 (1):89–102. doi: 10.1177/0956247816684763.

- Kythreotis, A. P., A. E. Jonas, T. G. Mercer, and T. K. Marsden. 2023. Rethinking urban adaptation as a scalar geopolitics of climate governance: Climate policy in the devolved territories of the UK. Territory, Politics, Governance 11 (1):39–59. doi: 10.1080/21622671.2020.1837220.

- Leck, H., and D. Simon. 2018. Local authority responses to climate change in South Africa: The challenges of transboundary governance. Sustainability 10 (7):2542. doi: 10.3390/su10072542.

- Leitner, H., and B. Miller. 2007. Scale and the limitations of ontological debate: A commentary on Marston, Jones and Woodward. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 32 (1):116–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-5661.2007.00236.x.

- Manuel-Navarrete, D., and M. Pelling. 2015. Subjectivity and the politics of transformation in response to development and environmental change. Global Environmental Change 35:558–69. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.08.012.

- Marks, D., and L. Lebel. 2016. Disaster governance and the scalar politics of incomplete decentralization: Fragmented and contested responses to the 2011 floods in Central Thailand. Habitat International 52:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.08.024.

- Marston, S. A. 2000. The social construction of scale. Progress in Human Geography 24 (2):219–42. doi: 10.1191/030913200674086272.

- Marston, S. A., J. P. JonesIII, and K. Woodward. 2005. Human geography without scale. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 30 (4):416–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-5661.2005.00180.x.

- Moore, A. 2008. Rethinking scale as a geographical category: From analysis to practice. Progress in Human Geography 32 (2):203–25. doi: 10.1177/0309132507087647.

- Nagoda, S., and A. J. Nightingale. 2017. Participation and power in climate change adaptation policies: Vulnerability in food security programs in Nepal. World Development 100:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.07.022.

- Neumann, R. P. 2009. Political ecology: Theorizing scale. Progress in Human Geography 33 (3):398–406. doi: 10.1177/0309132508096353.

- Nightingale, A. J. 2017. Power and politics in climate change adaptation efforts: Struggles over authority and recognition in the context of political instability. Geoforum 84:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.05.011.

- Osborne, N. 2015. Intersectionality and kyriarchy: A framework for approaching power and social justice in planning and climate change adaptation. Planning Theory 14:130–51. doi: 10.1177/14730.95213.516443.

- Parsons, M., K. Fisher, and J. Nalau. 2016. Alternative approaches to co-design: Insights from indigenous/academic research collaborations. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 20:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2016.07.001.

- Pellow, D. N. 2017. What is critical environmental justice? Cambridge UK: Wiley.

- Phuong, L. T. H., G. R. Biesbroek, and A. E. Wals. 2018. Barriers and enablers to climate change adaptation in hierarchical governance systems: The case of Vietnam. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 20 (4):518–32. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2018.1447366.

- Porter, L., L. Rickards, B. Verlie, K. Bosomworth, S. Moloney, B. Lay, B. Latham, I. Anguelovski, and D. Pellow. 2020. Climate justice in a climate changed world. Planning Theory & Practice 21 (2):293–321. doi: 10.1080/14649357.2020.1748959.

- Pradhan, S. 2018. Understanding the role of politics of scale and power relations in local governance of climate change adaptation: Case study from coastal Odisha, India. PhD dissertation, University of Reading.

- QSR International Pty. 2018. NVivo qualitative data analysis software (version 12). Burlington, MA: QSR International.

- Schapper, A. 2018. Climate justice and human rights. International Relations 32 (3):275–95. doi: 10.1177/0047117818782595.

- Scoville-Simonds, M., H. Jamali, and M. Hufty. 2020. The hazards of mainstreaming: Climate change adaptation politics in three dimensions. World Development 125:104683. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104683.

- Sharp, L., and T. Richardson. 2001. Reflections on Foucauldian discourse analysis in planning and environmental policy research. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 3 (3):193–209. doi: 10.1002/jepp.88.

- Shi, L. 2021. From progressive cities to resilient cities: Lessons from history for new debates in equitable adaptation to climate change. Urban Affairs Review 57 (5):1442–79. doi: 10.1177/1078087419910827.

- Smucker, T. A., M. Oulu, and R. Nijbroek. 2020. Foundations for convergence: Sub-national collaboration at the nexus of disaster risk reduction, climate change adaptation, and land restoration under multi-level governance in Kenya. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 51:101834. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101834.

- Stock, R., S. Vij, and A. Ishtiaque. 2021. Powering and puzzling: Climate change adaptation policies in Bangladesh and India. Environment, Development and Sustainability 23 (2):2314–36. doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-00676-3.

- Thomas, K., R. D. Hardy, H. Lazrus, M. Mendez, B. Orlove, I. Rivera‐Collazo, J. T. Roberts, M. Rockman, B. P. Warner, and R. Winthrop. 2019. Explaining differential vulnerability to climate change: A social science review. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 10 (2):e565. doi: 10.1002/wcc.565.

- Tschakert, P., P. J. Das, N. S. Pradhan, M. Machado, A. Lamadrid, M. Buragohain, M. Buragohainand, and M. A. Hazarika. 2016. Micropolitics in collective learning spaces for adaptive decision making. Global Environmental Change 40:182–94. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.07.004.

- Tschakert, P., D. Schlosberg, D. Celermajer, L. Rickards, C. Winter, M. Thaler, M. Stewart‐Harawira, and B. Verlie. 2020. Multispecies justice: Climate‐just futures with, for and beyond humans. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change e699:1–10.

- Tuana, N. 2019. Climate apartheid: The forgetting of race in the Anthropocene. Critical Philosophy of Race 7 (1):1–31. doi: 10.5325/critphilrace.7.1.0001.