Abstract

This article draws on findings of long-term field research in upland central Laos, examining the rapidly changing dynamics of language among multilingual Indigenous communities in the upper reaches of Laos’s massive Nam Theun 2 Hydropower Project. The case study of sudden language shift in the context of new transport infrastructure finds disruption of distributional flow at multiple levels, from natural forces to built networks to the circulation of communicative norms and social encounters. This is understood in terms of layered infrastructures, which are distinguished at three main, interarticulated levels: natural (e.g., river systems), technological (e.g., transport networks), and institutional (e.g., language ecologies). A key finding is that linked infrastructures are causally interdependent through mechanisms of flow piracy (intercepting flows and transforming them for new purposes) and percolation (denuding networks and critically reconfiguring them). The case study from Laos of rapid change in the context of a hydropower dam not only refines our conception of infrastructure, but the idea of language itself as an infrastructure helps us to better understand its spatialized dynamics, foregrounding language as a new empirical domain in the study of infrastructure and other socially spatialized networks.

Este artículo se basa en los hallazgos de una investigación de campo a largo plazo en la zona montañosa del centro de Laos, destinada a examinar la dinámica rápidamente cambiante del lenguaje, entre comunidades indígenas multilingües que habitan las tierras más altas del enorme Proyecto Hidroeléctrico de Nam Theun, en Laos. El estudio de un caso de cambio lingüístico súbito dentro del contexto de una nueva infraestructura de transporte, revela la alteración del flujo de distribución a múltiples niveles, desde las fuerzas naturales hasta las redes construidas, pasando por la circulación de normas comunicativas y los encuentros sociales. Lo anterior se entiende en términos de infraestructuras estratificadas, en las que se distinguen tres niveles mayores inarticulados: el natural (por ejemplo, los sistemas fluviales), el tecnológico (por ejemplo, las redes de transportes) y el institucional (por ejemplo, las ecologías lingüísticas). Un descubrimiento clave es que las infraestructuras interconectadas son interdependientes causalmente a través de los mecanismos de piratería de caudales (la interceptación de flujos y su transformación para nuevos propósitos) y la percolación (denudar redes y reconfigurarlas críticamente). El estudio de caso de Laos sobre cambio rápido en el contexto de una presa hidroeléctrica no solo refina nuestro concepto de infraestructura, sino la propia idea del lenguaje como infraestructura que nos ayuda a entender mejor su dinámica espacializada, colocando en primer plano al lenguaje como un nuevo dominio empírico para el estudio de la infraestructura y otras redes espacializadas socialmente.

根据对老挝中部高原的长期实地研究, 本文探讨了老挝大型Nam Theun 2水电项目的上游多语言土著社区在语言上的快速变化。在新的交通基础设施背景下, 我们研究了语言的突然转变, 发现了对水流的多层次破坏:自然力、人工网络、交流规范和社会接触循环。可以从层次化基础设施角度来理解这种破坏, 主要有三个相互关联的层面:自然(例如, 河流水系)、技术(例如, 交通网络)和制度(例如, 语言生态)。研究发现, 通过“水流劫持”机制(拦截水流并按照新目标进行改造)和“渗透”机制(剥离并重新配置网络), 相连接的基础设施相互依存。本文对水电站大坝背景下的快速变化的案例研究, 完善了我们对基础设施的理解。本文提出的语言本身也是基础设施的理念, 有助于我们更好地理解其空间变化, 并将语言作为基础设施等社会空间网络研究的新经验性领域。

This article examines local community impacts of the $1.45 billion Nam Theun 2 (NT2) hydropower project—one of Laos’s biggest infrastructure schemes (Tran and Suhardiman Citation2020; Suhardiman and Geheb Citation2022; Kenney-Lazar, Suhardiman, and Hunt Citation2023)—with a focus on linguistic practices of the Indigenous communities who inhabit the dam’s protected catchment area, the Nakai-Nam Theun (NNT) watershed. State and corporate electricity projects draw narratives of development (Bennett Citation2005; Singh Citation2009; Swyngedouw Citation2015; Harvey, Jensen, and Morita Citation2017a; Whitington Citation2018) and can bring welcome benefits to citizens, from power supply to improved access. As ventures of “infrastructural colonization” (Dunlap and Arce Citation2022, 457), however, these projects can also bring disaster (Gergan Citation2020), dispossession (Kelly Citation2021), and social and environmental violence (Baird Citation2021). Since the NT2 project began generating electricity for international export in 2010 (Singh Citation2009; Baird and Quastel Citation2015; Shoemaker and Robichaud Citation2018; Whitington Citation2018; Marks and Zhang Citation2019), there have been signs of acceleration in watershed residents’ use of Lao, the national standard language of Laos, along with an imminent decline in usage of Indigenous languages. This case of change in language value and practice exposes the role of infrastructure in the disruption of sociocultural agency. As we shall see, the fact that language is lured and channeled by infrastructure leads naturally to the idea that language itself is a spatialized infrastructure that similarly serves to lure and channel, not just water and goods, but ideas, social relations, and indeed language itself. This opens a new way of thinking about language in spatialized terms.

There is, of course, a long history in geographical thinking and practice around language. Language cartography has tapped into speakers’ native fascination with the territoriality of ethnicized language varieties, as well as the political arguments leveraged by maps in land claims by groups ranging from Indigenous communities to state actors to military forces (Kaplan Citation1994; Auer and Schmidt Citation2009; Lameli, Kehrein, and Rabanus Citation2010; Rabanus Citation2020). Global maps of linguistic features figure centrally in research on structural diversity in language (Haspelmath et al. Citation2005; Dryer and Haspelmath Citation2013; Comrie Citation2020), in turn raising causal questions of the diversification process across space and time (Nichols Citation1992). Wherever languages are found in the same place there are processes of language contact (Weinreich Citation1953; Thomason and Kaufman Citation1988; Thomason Citation2001) as studied in areal linguistics (e.g., Muysken Citation2000; Aikhenvald and Dixon Citation2001; Aikhenvald Citation2002). Social dominance in language-contact dynamics is often attributed to physical geography, for example where mountainous environments can affect language structure (Urban 2020) or where different proximity to river edges can create conditions for speech-community inequalities (Muysken and Van Gijn Citation2015). The image of linguistic elements moving and evolving through spatialized populations of agents has invited models of cultural epidemiology (Sperber Citation1985; Enfield Citation2003) for understanding how language is distributed the way it is.

Current human geography acknowledges a need for closer attention to language. Brickell (Citation2013) remarked that “geographers have failed to devote sustained attention to speech as a practice that provokes meanings in, and of, different spaces” (207). Medby (Citation2020) stated that in political geography there is a need to engage more with language and language practices. Accordingly, geographers are increasingly interested in processes by which “words construct relevance and irrelevance” (Adams Citation2022, 1) and thus build shared conceptions of space. Language can make and remake identities and “change the way that spaces are ordered” (Valentine, Sporton, and Nielsen Citation2008, 376). Geographers are looking to language for measures of how environmental forces may be represented and framed, for example by analyzing grammatical and lexical choice (Bailey et al. Citation2014), through frame analysis or critical discourse analysis (Bolsen and Shapiro Citation2018), by using sentiment analysis (Jost, Dale, and Schwebel Citation2019) or the study of metaphor (Jackson Citation1999). Linguistic resources can build shared understandings of environmental experience, for instance with the expression of gradient qualities of temperature (Adams Citation2022), and more broadly in dialogue about place, in which “place meanings emerge through interactions between human agency and the nonhuman agency of place” (Adams and Kotus Citation2022, 1; see also Adams Citation2016).

The concept of infrastructure provides a natural link between spatial interests in research on language and linguistic interests in research on place. How does thinking infrastructurally help us understand the dynamics of language contact and change? In considering this question, we find not only that language is a spatially distributed—and distributing—network, but that the insights go in the other direction, too: Language dynamics shed new light on the theoretical understanding of infrastructure. By thinking about the intertwined fates of languages and other assemblages, we will better understand the spatialized ontology of infrastructure itself.

In the rest of the article, I first describe the data, methods, and positionality adopted in this study. I then introduce the NT2 hydropower project and its impacts on upland watershed communities over the last decade or two, with a focus on changes in transport networks and associated mobilities. The next section introduces conceptual tools (including assemblage, articulation, network, and distribution) needed for a definition of infrastructure that is general enough to apply equally well to ontologically unalike systems—from rivers to roads to languages—and to define how such systems might be causally interlinked, while being specific enough not to imply that everything, and therefore nothing, is infrastructure. The same section also introduces the key concepts of flow piracy and percolation, two kinds of flow-diverting perturbation that can transform structure and value within and across any level in an infrastructural assemblage. We then return to the evolving language situation in the NNT watershed. We see that mechanisms of piracy and percolation occur in natural, technological, and institutional infrastructures of the watershed. These mechanisms intercept and redirect agents’ opportunities to engage in social encounters, in turn reconfiguring the communicative economy that languages and other sociocultural conventions depend on for their existence.

Methods, Data, and the Research Process

This study draws on long-term field work conducted since 2004 with villagers of the NNT watershed, especially the upper reaches of the Nam Noi River. The project started with a focus on the Kri language and its speakers, whose social agency is bound up in intergroup relations. The linguistic ecology of the area is characteristic of upland mainland Southeast Asia, where minoritized languages are in intensive contact, due to the intergroup connectivity widely observed in this part of the world (Leach Citation1954; Scott Citation2009).

This article draws on data and findings from research conducted during eleven field trips to Nakai District in the period between 2004 and 2020. I have applied and combined a range of methods, including participant observation in diverse domains of practice (including cohabitation in family homes, inter- and intravillage social visits, forest walks, participation in agricultural practice, ritual practice, etc.); video recording and photographic documentation of these practices, especially informal social interaction in homes; focused linguistic and ethnographic elicitation and transcription sessions (often reviewing video and photographic materials); and semistructured interviews to check, probe, and evaluate hypotheses and findings. I resided for weeks at a time as a guest in numerous homes in four village settings (Mrkaa, Srôô, Palààt, and Pung) in which the Kri language is learned by children. I also frequently visited, by day or on overnight stays, many other villages in the NNT Watershed. In 2018 to 2020, the project’s scope expanded to include collaborators in linguistics and anthropology (Weijian Meng, Gus Wheeler, and Chip Zuckerman), working on the relation between language, ethnic identity, mobilities, social and ritual relations, and linguistic ideology in the context of spatialized interactions between speakers of Kri, Saek, and Bru, as well as nation-state languages Lao and Vietnamese.

Regarding my positionality as a researcher, first, I am an outsider or other to NNT community members. They regard me as adept with matters of the modern world while lacking even the most basic skills and knowledge shared among NNT Watershed residents. Second, the government representative who has accompanied me on my trips to the watershed (as required by state regulations) is an insider to the area, a native speaker of Saek from Ban Beuk. This provided a valuable inroad to watershed-internal networks and perspectives. Third, as a man, I am assumed to have certain gendered knowledges, skills, and interests rather than others, and my access to the affairs of, and interactions with, men is naturally easier than with women. Finally, as a university-trained researcher, I maintain a liberal science positionality (Rauch Citation2013), whereby any understandings that are proposed, or that I conjecture, are regarded as provisional and ever open to criticism and correction (Popper Citation1994).

In their engagements with me and my co-researchers, NNT watershed villagers have not only been extraordinarily generous, but have also been excited about the project’s focus on language and cultural practices, by contrast with many more familiar state-sponsored projects that focus on socioeconomic and security objectives. My NNT watershed hosts, collaborators, and teachers are not only highly engaged with this linguistic-anthropological work, but have approached it with great intellectual seriousness.

Background: Twenty-First Century Developments in the NNT Watershed

Inhabitants of the NNT watershed are accustomed to constant change, although the developments introduced by the NT2 hydropower project have been especially sudden. The sections that follow focus on human ecology, language ecology, physical geography, and transport networks.

Human Ecology

Evidence from travelers, ethnographers, and living memory attests that up to and including the twentieth century, many NNT watershed residents were nomadic hunter-gatherers (Chamberlain Citation2020), ranging across the watershed’s periphery. By the turn of the twenty-first century, most villagers of the watershed had become reliant on subsistence agriculture, including paddy rice and swidden upland rice, cassava, and maize, supplemented by village-scale fishing, hunting, and gathering. During my earliest field trips to the area in 2004, some villages (e.g., Teung) were permanent settlements of up to a hundred households, whereas others (e.g., Mrkaa) were smaller, more temporary hamlets, with some five to ten households per settlement. Frail dwellings would be abandoned within a decade before families would move on to new locales. In 2004, watershed village infrastructure (houses, huts, etc.) was constructed exclusively by villagers from forest products using machetes: light timber, bamboo, rattan, and palm leaves, without nails, bricks, boards, or tiles. After a rapid critical transformation in housing and settlement patterns since 2010, timber boards and roof tiles are now the norm in house construction, meaning that most settlements are now effectively permanent (Zuckerman and Enfield Citation2022). Accordingly, although livelihoods still depend on a mix of crops and hunter-gathering, a more sedentary lifestyle favors paddy farming, which in turn puts ecological constraints on settlements in terms of terrain and water supply.

Language Ecology

Five language varieties are spoken in the NNT watershed (including two dialects of Kri). See .Footnote1

Table 1. Language varieties of the Nakai-Nam Theun watershed

Of the three minority languages, Kri varieties have been present in the area longest, followed by Saek, whose speakers migrated into the area around 300 years ago, and then Bru, whose low internal diversity in the watershed suggests arrival within the last two centuries (Chamberlain Citation2020, 1603–04). The linguistic ecology is complex, due especially to widespread multilingualism among watershed residents.

Language in the NNT watershed plays a key role in interethnic contact of a kind that has characterized life in mainland Southeast Asia for millennia (Leach Citation1954; O’Connor Citation1995; Scott Citation2009). Today, the dynamic involves communities at opposite ends of the demographic spectrum. Speakers of relatively threatened languages like Kri and Saek, who number in the hundreds, engage with speakers of nation-state languages like Lao and Vietnamese, whose speakers number tens of millions. The difference in language-group size spans five orders of magnitude.

As a social technology, language serves the function of social coordination, from home and village life to interpersonal conflict to the expression of shared identity. When social conditions are relatively stable, language conventions become focused enough that we can identify distinct languages (Le Page and Tabouret-Keller Citation1985; Dixon Citation1997). Numerous languages might coexist, creating situations of language contact (Weinreich Citation1953; Thomason and Kaufman Citation1988; Chappell Citation2001; Thomason Citation2001; Aikhenvald Citation2002) and stable multilingualism (Auer and Wei Citation2007). In the watershed, social encounters between Indigenous residents and monolingual speakers of Lao are increasing with new connections to lowland networks and associated state and market forces. There is more in-migration from the lowlands, with some watershed children now born to Lao-speaking parents and growing up monolingual in Lao. This is leading to a tipping point in some villages away from receptive multilingualism—that is, where people speak their own language rather than all converging to a common lingua franca (ten Thije and Zeevaert Citation2007; Bahtina and Thije Citation2013)—and toward Lao monolingualism (e.g., Serk Village, which rapidly shifted from Bru to Lao in the decade between 2008 and 2018).

Formal schooling in the Lao language was virtually nonexistent in prereservoir times. Today, watershed children learn Lao from a young age in village schools. In our surveys of multilingual competence in the watershed, people’s command of Indigenous languages is declining in favor of Lao as the dominant second language. Within a generation, the state standard language—Lao—will dominate the NNT watershed.

Physical Geography

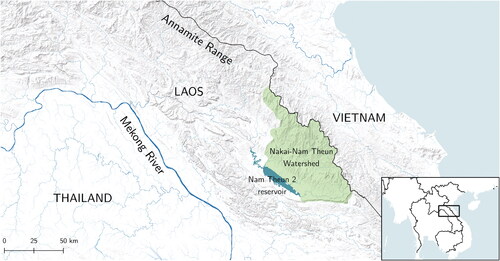

The NNT watershed is situated 300 km east of the Lao capital Vientiane (). It covers approximately 4,000 km2 (Descloux et al. Citation2016, 10) of protected forest in the Northern Annamites Rain Forests area (Ecoregion code IM0136; ADB/UNEP Citation2004, 68–69), one of 867 terrestrial ecoregions recognized by the World Wide Fund for Nature, and one of the Global 200 “outstanding examples of biodiversity” (ADB/UNEP Citation2004, 72).

Figure 1. Location of the Nakai-Nam Theun watershed: The Nakai-Nam Theun National Park drains into the Nam Theun 2 Reservoir (center). Map by Angus Wheeler. Source: Data from NASA Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) (2013). Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) Global. Distributed by OpenTopography. https://doi.org/10.5069/G9445JDF.

The NNT watershed topography is hilly, but its watercourses are mostly gentle, with linked river pools and floodplains affording unencumbered foot travel along waterways. Most foot travel is along two rivers: the Nam Theun and the Nam Noi. At the western or downstream edge of the watershed is a sharp, rocky, and thickly forested descent that serves as a natural obstacle to foot transport and settlement, being steep and difficult to traverse or cultivate. Below this, the land opens onto the expansive Nakai Plateau, which afforded free movement by foot prior to the dam’s impoundment. With the buffer separating watershed and plateau, residents would travel mostly within the watershed while occasionally going beyond. The plateau and its settlements (see ) were permanently inundated in 2008.

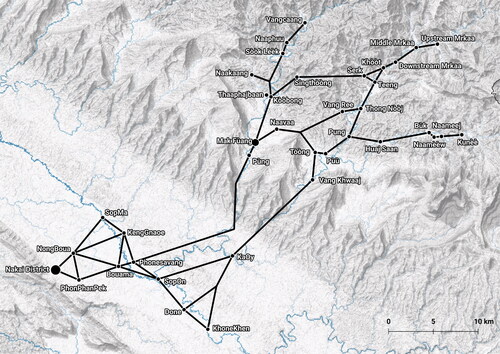

Figure 2. Main lines of transportation in the Nakai-Nam Theun watershed, prereservoir (2004). Nodes are villages, lines are foot trails (as straight lines for simplicity). Boats were not widely used other than for intravillage travel. Walking time from Upstream Mrkaa to Nakai District was up to twenty-four hours, requiring two overnight stays. Map by Angus Wheeler. Source: Date from NASA Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) (2013). Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) Global. Distributed by OpenTopography. https://doi.org/10.5069/G9445JDF.

Recent changes in transport infrastructure have radically altered the distribution of social encounters in the watershed.Footnote2 People now travel much faster and have less opportunity to interact during their travels, but they still travel mostly along rivers. Thus, the physical geography of the watershed channels people’s movements along the natural flowlines of water. Rugged hillsides are protected by their inaccessibility. Residents only occasionally venture onto the thick slopes when in search of forest products not found near their village base (e.g., Livistona palm leaves for roof thatching).

The topography has also shaped livelihoods. Saek speakers in the villages of Teung, Huaj Saan, Bùk, Naamèèw, and Naameej are descendants of relatively recent Tai migrations driven by the search for flat land for paddy farming. Their long-established village settlements adjoin flat expanses of land for wet rice cultivation and permanent water supply (rivers and streams) for ditch-dike irrigation. Kri- and Bru-speaking villagers are, similarly, settled along rivers, but focus more on swidden rice agriculture, mainly on sloping land. That said, these villagers prefer to work gentle land near their home base. Thus, livelihood practices are shaped by affordances of landscape, keeping people near flat land along permanent watercourses.

In sum, the ecology of the NNT watershed is a natural infrastructure for the spatial distribution not only of water but of human mobilities, livelihoods, settlements, and social encounters, funneling populations into common channels of flow and sites of residence, and creating common fate in opportunities for interaction. As we shall see next, this natural infrastructure sets constraints on built infrastructure.

Transport Networks

A transport infrastructure is readily conceived in network terms; that is, as lines that connect nodes (Newman Citation2018). depicts the transport networks (mostly walking trails) in the NNT watershed prior to the impoundment of the NT2 hydropower reservoir in 2008.

As shows, the transport network before the dam had a decentralized, braided structure. The villages are roughly an hour’s walk apart, the preferred maximum commute time for residents traveling between villages or to and from swiddens. This fits the universal Zahavi–Marchetti rule: People are willing to commute an hour per day (Zahavi Citation1974; Marchetti Citation1994). To avoid longer commutes, people would occasionally decamp. Temporary settlements would pop up during periods of intensive labor at swiddens, as when clearing new land, weeding plantations, or guarding nearly ripe crops.

When the NT2 dam wall was completed in 2008, the plateau was inundated and became a permanent reservoir. This immediately blocked pedestrian traffic across the plateau. From then, all travel between the watershed and the district center at Nakai District town was by boat. Passenger boats now travel daily to and from the watershed village of Mak Fùang. From 2009, the Watershed Management Protection Authority (WMPA), following the World Bank’s environmental protection stipulations, installed a road network inside the watershed to facilitate motorcycle and hand-tractor traffic (while—by design—disallowing car or truck transport). Prior to 2008, there were two hand tractors in the watershed, and no motorbikes. By 2020 there were dozens of hand tractors and at least fifty motorbikes.

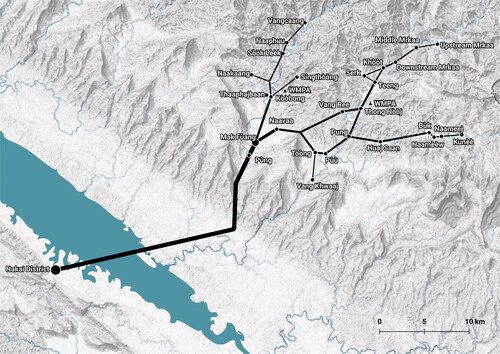

The hydropower reservoir’s sudden redirecting of transportation flow reconfigured the prereservoir braided network pattern of , creating the captured stream layout shown in .

Figure 3. Major lines of transportation in the Nakai-Nam Theun watershed, postreservoir (2020). Nodes are villages, lines are paths (straightened for simplicity) built for light motor vehicles (or rivers as paths for boats). Triangles marked WMPA are field stations of the Watershed Management Protection Authority. The thickest line is the daily passenger-boat route. All plateau villages (see bottom left quadrant of ) have been relocated to the southwest shore of the reservoir (Hunt, Samuelsson, and Higashi Citation2018). Map by Angus Wheeler. Source: Data from NASA Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) (2013). Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) Global. Distributed by OpenTopography. https://doi.org/10.5069/G9445JDF.

All travel between watershed villages and Nakai District now passes through the port hub of Mak Fùang, and most of it, being motor-powered, now dramatically reduces travel time, in a kind of time-space compression (Harvey Citation1989) also noted by Baird and Vue (Citation2017) for Hmong social networks elsewhere in Laos. Mrkaa village to Nakai center is no longer a three-day hike but a five-hour ride by motorbike and passenger boat.

Interarticulated Distributional Networks

The changes experienced by communities of the NNT watershed since the 2008 impoundment of the hydropower reservoir reveal numerous interdependencies among diverse networks, including those shaped by physical geography, mobility patterns, transport systems, livelihood practices, and social interactions. My goal here is not simply to describe these relations. I want to understand the causes of language change in the context of infrastructure change. This demands that we develop a conceptual framework for theorizing those interconnections and processes. That is the goal of this section.

We draw now on literatures from human geography, and beyond, that have theorized infrastructure and its elements. I argue that these not only help us understand the dynamics of this case, they help us understand how infrastructures can be causally interlinked, and in turn they help us better understand the anatomy of infrastructure itself.

In what follows, we first introduce the key concept of assemblage, a whole with parts, and the corollary puzzle of articulation: how assemblages hold together in greater wholes. We focus on assemblages that are spatially extended and have the function of distribution. With these concepts in hand, we propose a modality-free definition of infrastructures as horizon-exceeding distributional networks. We then consider how such networks can change, through two types of system-reorganizing process: flow piracy and percolation. The conceptual reference points thus established provide the tools for a deeper understanding of language dynamics as concerted infrastructure change, to which we then return.

Assemblage, Articulation, Extension, and Distribution

Networks that direct flows of water, vehicles, and language-mediated encounters are made from assemblages (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1987; DeLanda Citation2016): “wholes whose properties emerge from the interactions between parts” (DeLanda Citation2006, 5; Escobar Citation2008, 287). Examples of assemblages include households, villages, markets, road systems, riverine ecologies and, of course, hydropower projects. Because assemblages can incorporate diverse elements of nature, technology, society, culture, and cognition, something like a large dam must be understood as far more than a concrete wall (Sneddon Citation2015, 7; Swyngedouw Citation2015, 21). The NT2 hydropower project is a prime example, stretching as it does from the protected rainforests of the Annamite Chain to the air-conditioned luxury malls of central Bangkok, drawing tens of millions of people into its dominion, harnessing the incorrigible force of gravity on water and turning that planetary compulsion into economic and political power.

Assemblages, in turn, are linked by relations of articulation, defined as a connection or mechanism that can “make a unity of two different elements” (Hall Citation1996, 141). Articulation thus derives higher level assemblages (Swyngedouw Citation2015, 7) such as hydropower projects, transport networks, and language ecologies. For assemblages to hang together as they do, “ontologically diverse actants” must have agency in the soft-assembled “provisional orderings” that cohere within sociospatial contexts (Anderson et al. Citation2012, 173). Assemblages must interconnect in ways that are, on the one hand, concrete enough to be navigable by agents who inhabit the networks, and on the other hand, flexible enough to remain negotiable and dispensable in contexts of transformation and change. Infrastructures and other higher order assemblages are rife with “relational discontinuities,” where “intervals of difference and ambiguity” between assemblages create space for movement and plasticity (Harvey Citation2012, 88).

A full theory of articulation must account for coherence in the framing of sociospatial relations, as in concepts of territory, place, scale, and network (Jessop, Brenner, and Jones Citation2008). It must also account for relations of coherence between ontologically distinct levels at which sociospatial relations are created, and in turn have creative force (Kockelman Citation2006). This study shows that although articulation remains mostly subliminal to the analyst—that is, as long as everything is running smoothly, we do not notice the structures that hold it all together—disruptions arising from flow interception and diversion can bring it into view.

Articulation provides the glue that holds assemblages together in ever-larger systems. This allows higher level networks to extend across space, far beyond the local horizons of human actors. This, I argue, is criterial to infrastructure, a concept that has been theorized in diverse fields of geography and beyond. This work has established that infrastructure systems are as informational as they are material, as political as they are technical, as symbolic as they are functional. Infrastructures both foster and hamper the agency of their users, while harboring master narratives of the technical, financial, and state powers that design, install, and wield them (Scott Citation1998; Star Citation1999; Foucault Citation2010; Furlong Citation2020). Being assembled from heterogenous elements, an infrastructure is “material, social, and philosophical” (Howe et al. Citation2016, 549); it spans “the technical, the urban, and the human” (Kanoi et al. Citation2022, 10), the “local and global, material and social, science and everyday life” (Blok et al. Citation2016, 18). Infrastructures are known to “structure social relations” (Harvey, Jensen, and Morita Citation2017a, 5) and “organize social interactions” (Angelo and Hentschel Citation2015, 311; see also Rodgers and O’Neill Citation2012, 402). Infrastructure is therefore “a fundamentally relational concept” (Star and Ruhleder Citation1996, 113). As such, an infrastructure is both a “material substrate underlying social action” (Harvey, Jensen and Morita Citation2017b, 615) and “a terrain of power and contestation” (Appel, Anand, and Gupta Citation2018, 2). These qualities are achieved through infrastructure’s facilitation of flow, circulation, and connectivity (Larkin Citation2013, 328; Di Nunzio Citation2018, 2).

Although any infrastructure must incorporate the complex coherence of the flow-directing, power-imbued assemblage, it will have two further specific defining features. First, as noted, thanks to the power of articulation, an infrastructure has spatial extension (Harvey, Jensen, and Morita Citation2017b, 5). An infrastructure is horizon-exceeding, extending beyond what an agent who resides within that infrastructure can view or access at any moment. Second, and relatedly, an infrastructure facilitates distribution. By providing “a path to a destination” (Kockelman Citation2010b, 15), an infrastructure functions to “generate, disseminate, and stabilize” our representations, judgments, and actions (Kockelman Citation2010b, 58). Distribution serves a crucial function of any system that links production to consumption, be it a mammalian circulatory system, an agricultural economy, a cycle of ritual exchange, or a hydroelectric grid.

With these notions of assemblage, articulation, extension, and distribution in hand, we can define infrastructure as any horizon-exceeding interarticulated assemblage that facilitates distribution. This definition is modality-free, meaning that it applies at any ontological level, including natural (e.g., a river watershed or mammalian circulatory system), technological (e.g., a road network or electricity grid), and institutional (e.g., a language or a legal code).Footnote3 We see in the NNT watershed that infrastructures can be laminated onto each other, like overlaid diagrams, secured to each other by relations of articulation. But they do more than just exist in parallel. They affect and condition each other. They exchange flow across modalities, such that disruption in one layer can perturb and transform structure and value in another layer. We now turn to two of the most important change-inducing mechanisms.

Infrastructural Perturbations: Flow Piracy and Percolation

Spatialized assemblages are fluid and “always under construction” (Massey Citation2005, 9). What are the properties of distributional assemblages that so persistently allow them to change? Here we focus on two mechanisms that can reorganize networks. These mechanisms are flow piracy and percolation. They create network change and thus disclose sites of articulation that hold layered networks together. They show how interceptions that occur in one ontological level of infrastructure (e.g., a river system) can have collateral effects on another level (e.g., a language system).

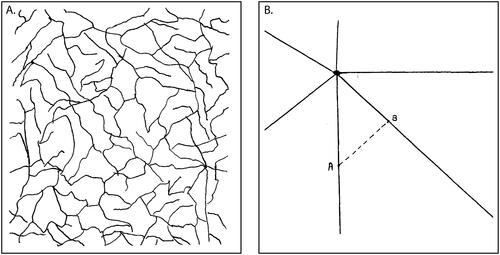

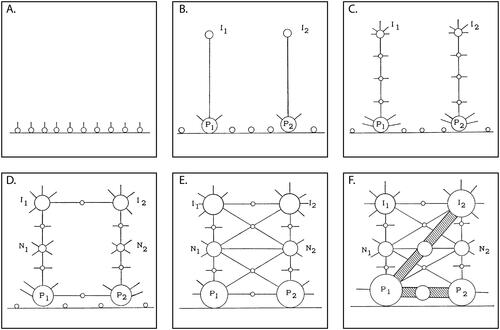

The reconfigured transport infrastructure depicted in shows the results of one kind of perturbation of a distributional infrastructure. This is flow piracy (or channel piracy), a concept defined in twentieth-century hydrogeology (Horton Citation1945, 366; see also Bowman Citation1904; Crosby Citation1937; Normark Citation1970), whereby a network’s structure is simplified and the speed and scale of flow through a part of the network increases. Imagine parallel rivulets, one just uphill of the other. In time, the earth containing the uphill rivulet erodes, letting it spill into the lower rivulet, intercepting its flow. The resulting event of flow capture halves the number of local network paths (from two to one) while doubling the volume of flow along a single path.

This process of interception and flow piracy is a form of parasitism (Serres Citation2007; Kockelman Citation2010a). It is observed when rhizomatic, crisscrossing, braided networks of old transport routes are collectively channeled into simpler, higher throughput links such as state-built highways. Looking at the effects of large-scale state-planned development projects, Scott (Citation1998, 74–75) contrasted a latticed network of communication routes “created by use and topography” () with a “centralized traffic hub” model () in which, to get from A to B, one is forced to pass through the center.

Figure 4. Flow piracy and percolation, before and after. (A) “Paths created by use and topography” (resembling “a dense concentration of capillaries”); (B) Centralized traffic hub” (forcing travel through the center). Illustrations are from Scott (Citation1998, 74–75).

An example of the process depicted in can be seen across six centuries of transport development in coastal West Africa (Taaffe, Morrill, and Gould Citation1963). By a form of “hinterland piracy,” new routes concentrated the flow of transport such that “the feeder networks of certain centers reach out and tap the hinterlands of their neighbors” (Taaffe, Morrill, and Gould Citation1963, 511). When the sequence began in the fifteenth century, “networks of circuitous bush trails connected the small centers to their restricted hinterlands” (Taaffe, Morrill, and Gould Citation1963, 506). These trails were the first to have their flow pirated in the process of infrastructure upscaling. As the process repeated, ever increasing the speed and scale of transport flow, the structure became simpler, although more hierarchized. shows the sequence (with the old, dense networks left implicit, in the empty spaces that are later filled).

Figure 5. Flow piracy and percolation, before and after. “Ideal-typical sequence of transport development”: Ghana, C15–C20 (Illustrations from Taaffe, Morrill, and Gould Citation1963, 504). The spikes on hubs are points of articulation where higher flow network links intercept and pirate the flow of smaller hinterland trails (not shown).

We have witnessed the same process of network reconfiguration in the NNT watershed as those described by Taaffe, Morrill, and Gould (Citation1963) and Scott (Citation1998). Channels have intercepted neighboring channels, pirating and redistributing their flow and concentrating it along remaining links in the network.

The contrast between and explicates the process of percolation (Fisher and Essam Citation1961): “taking a network and removing some fraction of its nodes, along with the edges connected to these nodes” (Newman Citation2018, 569). By reconfiguring and simplifying networks, percolation can lead to critical threshold phenomena, sudden changes and reorientations of a network’s structure and scale. By these means, new transport infrastructure in the postreservoir NNT watershed has radically reconfigured residents’ mobility through new networks for motorized transport.

Let us summarize the upshot of this section. We have established that an infrastructure is a delivery network built out of structured parts (assemblages), where those parts are connected by relations of articulation. Infrastructures of different ontological types—natural, technological, and institutional—can be layered and interdependent. When flow is perturbed by piracy and percolation, the effects can spread in two ways: first, horizontally, throughout an infrastructural network; and second, vertically, across articulations between layered networks, such that change in value of a flow in one level causes change in value on another level. As we shall see in the next section, this model of change in infrastructural flow allows us to better understand and explain the dynamics of language change in the context of the NT2 hydropower project.

Dynamics of Language as Infrastructure for Distributing Encounters

With this finer grained conception of infrastructure in hand, we now return to our NNT watershed study, and consider how mechanisms of flow disruption are causally manifest in the dynamics of language change in pre- and postreservoir NNT society. Changes in the physical distribution of water affect the flow of transportation, which in turn affects the distribution of opportunities for social interaction. This not only reshapes the traffic of information, ideas, relationships, and values, but also the flow of the communicative medium itself. Language opens paths for the transmission of social meaning and action but because language is built from learned conventions, language itself must also be transmitted. A language is a train that endlessly lays its own evanescent tracks. When walkers pass each other on a forest trail and stop to chat for a few minutes in the Kri language, they are not just exchanging news and gossip, they are circulating pieces of the language itself, contributing to the continued maintenance of its utility as a mode of social encounter.

In the following sections, we now unpack how these changes are experienced by NNT watershed villagers, affecting ethnicity, personhood, and interactions, the changing functions of language pre- and postreservoir, and the changing status of villages across the watershed.

Proximity and Ethnicity

Mobilities in the NNT watershed create networks for distributing opportunities for social encounters. Spatial proximity has an obvious effect. NNT residents are more likely to encounter people who live in their own village—and thus who are more likely to be speakers of the same language—than people who live elsewhere. Such encounters include planned gatherings as well as accidental moments of copresence. Encounters might occur at village-wide rituals, official meetings, while bathing at riverbanks, drinking tea socially on house verandas, or buying things from a merchant or in a local shop. Covillagers are more likely to share mutual communicative codes and ritual practices—that is, they will be ethnically and linguistically similar.

In our conversations and interviews with NNT villagers about language and identity,Footnote4 people use this principle of similarity through proximity as a rule of thumb in estimating others’ linguistic abilities. When one Saek man judged a covillager’s Bru language competence as low, he reasoned that it was because they had grown up in Teung, a Saek-speaking village. When we surveyed villagers’ evaluations of covillagers’ linguistic abilities, they often mentioned that residents of the same village speak the same common language.

People also cite ethnicity when reasoning about the languages people speak. Thus, when that same Saek man rated a covillager as a good Saek speaker, he mentioned ethnicity: “He’s a Saek person.” Such bundlings of ethnicity and language are the “secondary explanations” that Boas (Citation1910) noted have “nothing to do with their historical origin” but are invented as needed (e.g., to satisfy an inquisitive ethnographer; Boas Citation1911; Hymes Citation1968; Gal and Irvine Citation2019). These heuristics are not inflexible; people are readily able to set them aside. For example, NNT watershed villagers widely recognize that Serk village is ethnically Bru yet the Bru language is not dominant in that village. Similarly, Kri speakers recognize that the labels Kri Phòòngq and Kri Mrkaa refer to distinct linguistic varieties and to distinct ethnic identities, but also that one’s dialect and ethnicity need not pattern together. Thus, for example, a person who identifies as Kri Phòòngq might nevertheless natively speak the Kri Mrkaa dialect (Zuckerman and Enfield Citation2022).

Ethnolinguistic categories are heuristics that allow people to make educated guesses about who people are. They also give meaning and substance to social, moral, and political projects. I emphasize that these powerful resources for social action are both network-distributed contents of culture and vehicles for such distribution. In this way, language provides the materials for forming institutional infrastructures that in turn distribute encounters for the traffic of actions, roles, and identities, and their interpretations.

Multilingualism and Horizon-Exceeding Personhood

In the NNT watershed, a person’s capacity to move through social networks and across ethnic boundaries is greatly facilitated if they are multilingual. This capacity naturally broadens one’s opportunities for social encounters. It allows for more extended networks of friendship, kinship relations across villages, openness to travel for work, adventure, or study in the lowlands. High-functioning multilingualism is valued in the watershed, and it is a sign of masculine prestige. It is imagined as an index of having traveled far and wide, of having exceeded the horizons of villages and valleys, and thus of languages and traditions, of building networks of social relations beyond the horizons of home.

The spatialized nature of multilingualism is evident in local discourse around language learning. Siang Phòòng, a Bru man from Serk, explained how he knows multiple languages: “Because I come and go, because I have friends to meet with. Because when I come back, I don’t abandon those friends.” A frequent reference in NNT watershed discourse around well-traveled villagers is the forging of ritual friendship bonds in distant villages with people of other ethnicities and language groups.Footnote5 Tiw, a Kri woman, explained why some people learn languages and others do not: “Some leave the village, others stay home.” Siithaa, a Saek man who married a Bru-speaking woman, said the reason he does not know Bru is that he “hasn’t been” to Bru-speaking places. In contrast, he knows Vietnamese because he “goes all the time” to Vietnam. When Siithaa’s wife, Liang, a trader who knows Vietnamese, Lao, Bru, Kri, and Saek, was asked to evaluate the multilingual competency of some Mrkaa villagers, she gave one man a very low competency rating, explaining that she “had never seen him go anywhere.” After ranking another man highly in Lao competence, she said he was “a person who has gone places.”

Thus, in the NNT watershed, a person’s multilingualism is treated as an index of the horizon-exceeding spatial extension of their personhood, something that is enabled by layered infrastructures of mobility. The process is reminiscent of how Gawan Islanders of Papua New Guinea construct value and personhood beyond spatial horizons by cultivating fame throughout the Kula Ring in the Massim archipelago (Malinowski Citation1922; Munn Citation1986). Competent multilingualism implies a sociospatial expansion of the self over the course of life through the building of valuable relationship networks across space. Essential to this process is the horizon-exceeding extension of language as an infrastructure for distributing opportunities for social encounters.

Interoperability of Cultural Infrastructure for Encounters

Ethnolinguistic boundary crossings and language-mediated flows are enabled in part by the sociocognitive interoperability that a common language lends to mobile agents. These crossings and flows are also enabled by the corresponding conceptual interoperability of cultural ideas in the watershed, from marriage rules to agricultural practices, as common frames of reference. For example: Kri, Bru, and Saek villages all have both house spirits and village spirits, with similar logics and protocols for propitiation. Kri, Bru, and Saek people have easily translated ritual sanctions around marriage, including expectations regarding matrilocality, bridewealth, and in-law relationships. The Kri, Bru, and Saek languages show extensive similarities, both in structure and ideology (Zuckerman and Enfield Citation2022, Citationforthcoming; Enfield and Zuckerman Citationforthcoming). At the same time, there are also substantial differences between the communities’ cultural systems, a prominent example being agriculture: Saek speakers practice wet rice cultivation on flooded, flat, fields, whereas Kri and Bru speakers mostly practice swidden farming. This implies significant differences in calendar of work, skill set, and technological know-how.

The interoperability of sociocultural categories among NNT watershed inhabitants is both an effect and a cause of the distribution of social encounters. Although the result is convergence in conventions of meaning for communication and coordination, the affordances of such convergence are not equally enjoyed by all. Those who are more widely traveled, and who have cultivated the relevant competences, acquire special access to institutional infrastructures of meaning. They can cross boundaries, allowing agents with different group identities to intercept each other’s semiotic flow and make sense of each other for purposes of social coordination. Horizon-exceeding institutional infrastructure is thus both a product of and a facilitator for exchange—from prosociality to piracy—across sociocultural boundaries.

With this overview of the flow and distribution of social encounters in the NNT watershed in hand, we now see how recent changes expose articulations between infrastructures at different levels, as we consider the functional load on language infrastructure in pre- and postreservoir interactions.

Functional Load on Language Infrastructure, Prereservoir

In prereservoir times, an equalizer for NNT watershed residents was speed of travel. Everyone traveled on foot. Daily walk time of one or two hours was enough to reach fields or gardens and return to base each day. Longer journeys of greater cost—half- or full-day hikes—reveal more clearly the interface between mobility and encounter-mediated social relations. Here are some examples of significant travel events associated with interpersonal exchange:

A Mrkaa villager had an illness that would not improve; he hiked for six hours to Vang Khwaaj village to consult a spirit medium in hope of relief.

During a rice shortage in Vang Ree village due to crop damage from the sun, several villagers walked four hours to Mrkaa to borrow rice from fictive relatives.

Two teenage girls from Sing Thòòn village walked six hours, over the ridge separating the Nam Noi and Nam Theun valleys, to stay overnight with a ritually bonded best friend.

A Mrkaa man’s wife was in a hospital in Vietnam; wanting to talk with her, he walked two hours to Teung village where there is sometimes cell phone reception; he bought phone credit but could not find service and returned home.

A Saek villager staying in Mrkaa walked upstream for three hours on a fishing expedition to apply a technique for cornering and netting a fish species (Poropuntius sp.) in river pools; he took a Mrkaa villager as a guide and to help carry the catch.

Sometimes, prereservoir watershed villagers needed to go further afield. They could go east over the ridge to the nearest villages of Vietnam, requiring a full-day hike through thick forest and winding streams. Or they could cross the buffer zone downstream at the southwestern edge of the watershed to attend the district center in Nakai, covering 50 km or more on foot (see ). This might be to buy needed goods, to visit relatives, to receive provisions from government agencies, or to attend government briefings. For example, in 2005 a party of young Mrkaa village men made a week-long return hike to receive government-supplied latrine kits that they were mandated by the state to install at their homes.

These hikes could be arduous, often on steep, muddy, rainforest tracks, with the constant annoyance of insects and leeches. Travelers would make regular stream crossings, teetering across often-unsafe makeshift bridges, or fording streams, sometimes at waist height. In prereservoir times, all manufactured goods came into the watershed on foot. Exceptions were rare. Goods that did not travel on the backs of local villagers (or Vietnamese traders)—from salt to liquor to iron tools to clothing—came by helicopter on occasional ad hoc visits by Lao police or military, or power company officials. This put heavy limits on what could be transported, limits that locals would push to extremes. In 2004, I observed two petrol-powered hand tractors in Teung village. These machines weigh 150 kg, are two meters long and a meter high, the dimensions of a small car. With no way to transport the tractors in one piece, Teung villagers dismantled them in Nakai town and carried them piece-by-piece on their backs, reassembling them once at home deep inside the watershed.

Such journeys would presuppose and create enduring relationships: People rely on others for hospitality, debts are incurred, and investments are drawn on. This traffic of social relations is moderated by the inequalities that facilitate exchange, inherent in flow-generating imbalances of debt, knowledge specialization, and (fictive) kin relations. Thus, the slow rate of prereservoir pedestrian transport—caused by constraints of natural and built infrastructure—in turn shaped social relations across the watershed. It created contexts for recurrent social encounters, from path-side meetings to rest breaks on home verandas to overnight stays in villages, including on the plateau below the buffer zone. Pedestrian transport was key in creating and maintaining the cultural pluralism and receptive multilingualism that characterized the institutional and sociocultural infrastructure of prereservoir NNT watershed life. Slower, more localized traffic fostered the emergence of local, interlinked social networks reflecting mutual reliance between people of neighboring villages.

Consider the implications for language maintenance of these chained network structures. With locally clustered social networks around villages roughly an hour’s walk from each other, each network is linked at a higher level. Each subnetwork is thus an assemblage that is articulated to a neighboring assemblage by the bridging social ties that more mobile individuals maintain (Granovetter Citation1973, Citation1983; Zachary Citation1977; Brashears and Quintane Citation2018). More mobile individuals can broker information and exchange relationships between local networks (Burt Citation1992; Aral and Van Alstyne Citation2011). This is an important dynamic in language contact (Milroy Citation1980, Citation2004; Lippi-Green Citation1989; Trudgill Citation1996; Wiklund Citation2002; Tribur Citation2017; Sharma and Dodsworth Citation2020), as it leverages inequalities of agency within a community, allowing more highly connected, mobile, and multilingual individuals to influence the flow of language conventions in and across distributed networks.

In sum, the pre-2008 transport infrastructure—a braided network of walking trails (), itself shaped by the natural infrastructure of water flow—has shaped the distribution of opportunities for interpersonal encounters (Adams Citation2017, Citation2018), in turn shaping the social-relational and communicative ecology of the prereservoir watershed and its most powerful tools of social coordination: the practices of language.

Functional Load on Language Infrastructure, Postreservoir

Postreservoir changes in transport infrastructure have had numerous collateral effects on sociocultural infrastructure, including a dramatic amplification of inequalities, in line with the logic of flow piracy. After the NT2 hydropower reservoir was impounded in 2008, the sudden introduction of motorized transport introduced new and radical inequalities of mobility. Suddenly, some residents had access to motorbikes and much faster travel, whereas others could only travel on foot. Some had access to hand tractors and much greater carrying capacity, whereas others could only take what they could carry by hand. These inequalities were a function of buying power, where availability of cash came with local political position, especially through outside social contacts of the kind reviewed earlier. Men who had cultivated social relations beyond the horizon could now draw on their investments, activating these links to trade forest products for cash. This enabled them to buy motor vehicles to use on the new transport routes, which in turn gave them unique access to further benefits through transporting goods for trade, and so on.

New transport infrastructure increased travel speed dramatically. Before 2008, Mrkaa villagers’ three-day hike to Nakai would entail hours of conversation and relationship-forging shared adventure among party members as well as the creation of social-relational debts between overnight guests and their village hosts, often entailing sustained interactions in receptive multilingual mode. With the creation of the reservoir, though, many plateau villages were relocated, beyond the horizons of most watershed travelers (Hunt, Samuelsson, and Higashi Citation2018). Inside the watershed, the switch to using motor vehicles and more direct routes, afforded by new high-flow infrastructure, meant that travelers would now naturally choose the fastest option.

Thus, the flow of mobility was intercepted and pirated, eliding many of the old opportunities for social encounters. Passing through a village would once mean stopping to rest, talk, and open up channels for the flow of language, information, and social capital. Postreservoir percolation has now pruned those channels, as evidenced in the now-regular sight of a motorcycle raising dust as it speeds through a village on its way to somewhere else.

Inequality of Postreservoir Outcomes for Watershed Villages

Thus, the effects of flow piracy and network percolation are stark. The removal of nodes and links in transport infrastructure (see )—caused, ultimately, by the piracy of water flow in natural infrastructure for conversion into electricity through technological infrastructure—has intercepted and concentrated the flow of both commodities and social relations through centralized hubs and high-flow links, also for conversion into new kinds of products. One effect is to enhance inequalities through preferential attachment (Yule Citation1925; Simon Citation1955; Barabási and Albert Citation1999), also known as the rich get richer principle. To illustrate, we consider the diverse postreservoir fates of three differently situated villages.

Mak Fùang: Riverside Village to Bustling Port

Mak Fùang (encompassing the hamlet of Pùng) was the furthest-downstream village along the Nam Theun, although not the largest. Postreservoir, it has become the watershed’s sole port access point for ferries from Nakai District (and thus the sole path between the watershed and the rest of Laos). Mak Fùang now has well-stocked shops with everything from toys to rice to fertilizer to power tools. Daily passenger boats from Nakai District disembark there. Area schools are now located there. There is a constant stream of visitors: government officials, entrepreneurs, traders from elsewhere in the watershed and from neighboring provinces. A concert was held there on New Year’s Eve in 2018. For many people who travel to the watershed, Mak Fùang is the only place they see. It is the NNT watershed’s postreservoir boomtown.

Vang Khwaaj: Highway Stop to Backwater

Vang Khwaaj is the furthest downstream village along the Nam Noi. In prereservoir times, many watershed travelers heading for Nakai would follow the Nam Noi all the way down through the buffer zone toward KaOy (see ), meaning that many would stay overnight in Vang Khwaaj, especially if walking from villages far upstream such as Mrkaa. This constant traffic put Vang Khwaaj at the center of transportational, informational, and social networks that spanned both the watershed and the plateau. Postreservoir, however, that flow has been intercepted and siphoned off entirely. There is no longer any traffic through the buffer zone along the Nam Noi (see ). Vang Khwaaj has transformed overnight from bustling highway stop to sleepy cul-de-sac.

Mrkaa: Stable Border Post

The upstream-most village of Mrkaa—at the opposite end from Vang Khwaaj in the string of Nam Noi villages—is seeing less change. The main hamlets of Mrkaa village are relatively cut off from Teung village, which is about two hours’ walk away. The pathways leading upstream and downstream still only allow foot travel, with boats beginning to be used along certain sections. Because upstream motorboat traffic links Mrkaa to the border with Vietnam, the village is now more strongly oriented to the markets and social networks there. As evidence, whereas in the small home-based shops in Teung one can buy Lao-sourced snacks and cigarettes, in Mrkaa, the selection is entirely from Vietnam. Just over the border, in Hà Tĩnh Province, Mrkaa villagers maintain close social relations in villages of the Vietnamese uplands.

As these three examples show, from interceptions and percolations of horizon-exceeding distributive networks, there are winners and losers. Inequalities are inherent to these systems, and indeed it is debt, or its anticipatory corollary of investment—in forms ranging from the potential energy of intercepted water poised above a hydropower station to the lending of rice to a distant acquaintance during famine—that powers the continuing transformation of physical and institutional realities.

Repeated exchange is both created by and required by perduring social relations, revealing ambiguities in the direction of causation. On the one hand, the postreservoir decline of many social and linguistic relationships that once sustained rhizomatic travel networks could be interpreted as collateral damage from the hydropower project, a subtraction from the lives of the watershed people. The inverse could also be true, though. Could it be that the old extended institutional networks of social relations were themselves collateral effects of the unavoidable slowness of prereservoir travel, as shaped by braided patterns of flow through both technological and natural infrastructure? In the old world of multiday hikes, the body’s need for shelter and rest made it necessary for people to invest in the social relations that created contexts for social exchange in the needed forms of sustenance.

Conclusion: Infrastructures for the Distribution of Social Encounters

In seeking to understand the dynamics of language shift in upland Laos, we have seen three distinct levels of infrastructural assemblage at play: natural, technological, and institutional. Despite their distinct causal ontologies, they share the same essential logic: Each infrastructure is an interarticulated assemblage that facilitates distribution in horizon-exceeding networks. One level distributes materials by natural causes (water flow driven by gravity); another distributes motor vehicles by technological design (vehicles acquired, maintained, and driven by purposive agents); a third level distributes ideas, actions, rights, and duties by institutional norms. In this third level, we have located the infrastructures of language.

An infrastructure that circulates opportunities for social encounters is an infrastructure for the interactional order itself (Goffman Citation1983) and in turn for culture and social structure, through the spatiotemporal distribution of people, commodities, information, social relations, and cultural conventions (Adams Citation2017, Citation2018). As we have seen, the infrastructure for distributing opportunities for social encounters is linked to those other infrastructural levels by processes of interception that tap into channels of flow and convert them into new forms of energy and value.

The transformations are visible in the contrasts shown in .

Table 2. Some contrasts between pre- and postreservoir Nakai-Nam Theun watershed

Prereservoir infrastructures conspired to facilitate dense, interwoven social relations internal to the watershed, with ethnic pluralism and receptive multilingualism the norm. Recent processes of network piracy and percolation within and across these spatially distributed infrastructural levels, however, have touched off a coordinated threshold event by which natural, built, and institutional networks have been rapidly and simultaneously reconfigured. A meandering river has been stemmed and is now a reservoir. A dense network of footpaths has been pruned and funneled into major thoroughfares. The flow of an interlaced network of Indigenous languages is being intercepted by the state’s homogeneous national standard.

Because language flows through networks, there are constant opportunities for interception and flow capture. Indeed, notions of parasitism are foundational to theorizing the infrastructured traffic of information (Shannon Citation1948; Serres Citation2007; Kockelman Citation2010a). The idea of interception has been central to our account of infrastructural assemblages and the relations of articulation that bind them together. With language, though, the pirate’s spoils come neither from the selling of captured energy nor from economies of scale as in transport corridors. To be sure, social investments can bring material benefits. The primary fruits from piracy of language flows, however, are in the social relations—and their constituent rights, duties, and values—that depend for their existence on channels linking signers to interpreters.

There are corollary effects of intercepting language flow, in the processes of language shift, dominance, and decline (Nettle and Romaine Citation2000; Sallabank Citation2010). Thus, when we see a watershed child in an encounter with the Lao language facilitated by new transport infrastructure, we are looking at the interception of a communicative channel that would have otherwise carried the flow of an Indigenous language. This is a first step away from linguistic diversity and toward a state-centralized standard. It is a concerted form of flow piracy that will soon percolate the network and see the critical reorganization of linguistic practice and attendant language demise (Grenoble and Whaley Citation1998; Bromham et al. Citation2022).

Of the NT2 hydropower project, Whitington (Citation2018) wrote that “the technological apparatus of the dam is not opposed to ecology; it is an unexpected iteration of the river that affirms a certain, small number of ecological parameters at the expense of others. It is a singular and improbable intensification of that river” (73). Something similar must be said about the increasing dominance of the Lao language along the same flowlines: In the context of flow piracy and percolation of communicative infrastructure in the postreservoir watershed, we are seeing a singular—although perhaps less improbable—intensification of that language.

Flows happen by different means at different infrastructural levels: Natural infrastructures impose physical forces; built infrastructures retool or enhance those forces by design; and institutional infrastructures impose rights, duties, and values as biases on available paths for distribution. In turn, forces at higher levels can work back down. Each kind of infrastructure has channels for distributional flow, whether it is from high land to low land, between banks spanned by a bridge, or between a speaker and a listener. Where there is a channel, there is an opportunity to intercept, capture, exploit, transform, or even destroy what passes along it (Serres Citation2007; Kockelman Citation2010a). These interceptions are mechanisms by which agents tap into—and create—new forms of value. They also provide articulations between levels of infrastructure. Thus, the built infrastructure of a hydropower dam is predicated on the interception of flow in the natural infrastructure of a river system, just as the institutional infrastructure of a language is predicated on the interception of flow in networks of human mobility.

Our tracking of these processes began with a focus on the distribution of social encounters and led us to theorize infrastructure more generally. Understanding how a diverse set of spatially distributed forces coordinate around the social-interactional order has required us to develop a modality-free definition of infrastructures, as horizon-exceeding distributional networks. This conception provides a necessarily generalized underlying anatomy to infrastructure and a way to understand how diverse infrastructures—as interarticulated assemblages—are causally related. I submit that this generalized conception of infrastructure not only helps us understand the complex transformations observed in post-megadam Laos, it can be applied in a maximally diverse range of cases in which interceptions and interfaces between horizon-exceeding networks are implicated: how Canada’s emergence as a political entity derived from the fur trade and its interceptions and interactions among watercourse networks, lifeways of the beaver, diffusion of firearm technology, and settler–Indigenous social relations (Innis Citation1930); how Ghana’s transport infrastructure since the fifteenth century developed in ways constrained both by physical access to the sea and trading relations with peoples of the interior (Taaffe, Morrill, and Gould Citation1963); and how actors ranging from ocean currents to fishing communities to marine scientists to predatory starfish inserted themselves into the fates of the scallops of the Bay of Saint-Brieuc (Callon Citation1986). We can view these cases, and many more like them, as variations on a theme: worlds that are made and played by piracy and percolation in spatially extended, horizon-exceeding distributional networks; in a word, infrastructures.

Acknowledgments

I thank the audiences in various contexts at which this work was presented in draft form, at the University of Sydney, the University of Melbourne, the Australian National University, and the Austrian Academy of Sciences. For helpful comments, I thank Paul Adams, Keith Barney, Ian Baird, Phil Hirsch, Paul Kockelman, Weijian Meng, Alan Rumsey, Kendra Strauss, Gus Wheeler, Charles Zuckerman, and several anonymous reviewers. For helping me understand the dynamics of upland Laos in countless conversations over the years, I gratefully acknowledge Jim Chamberlain, Rachel Dechaineaux, Gérard Diffloth,† Grant Evans,† Chris Flint, Joost Foppes, Bill Robichaud, and Martin Stuart-Fox. I am particularly grateful to my co-researchers in the NNT watershed, Weijian Meng, Gus Wheeler, and Chip Zuckerman, and the many community members who welcomed us and helped us during our field work. The maps were created by Gus Wheeler.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest is reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

N. J. Enfield

N. J. ENFIELD is Professor of Linguistics in the School of Humanities, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Sydney, NSW 2006 Australia. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests include the confluence of language, culture, mind, and society from a complex systems perspective. His field research is conducted in mainland Southeast Asia, especially Laos.

Notes

1 Ethnolinguistic terminology is always fraught. Different terms have different connotations (insider/outsider terms, respect/derogatory terms, etc.). Also, Roman-script spelling of these labels varies given that they are seldom written (or if they are, the Lao script is used). Here, for example, I choose Bru (used by Green Citation1996; Pholsena 2002; Wheeler 2023), which is also sometimes spelled Bruu (Thongkham 1979), or Brou (“National Assembly approves Brou as New Ethnic Minority group”; KPL Lao News Agency 6 December 2018).

2 We focus on transportation changes. Other infrastructures include agricultural systems (ditch-dike networks for wet rice cultivation, used primarily by Saek speakers) and telecommunications, including mobile phones and television, new to the watershed in the last decade; cf. Baird and Vue (Citation2017) on similar changes experienced by other minoritized communities of Laos.

3 The institutional infrastructure in focus here is language. Others would include systems of kinship and marriage practice, systems of belief concerning supernatural entities, and local codes of law and justice around property rights and injury or murder. These are all amenable to the analysis advanced here.

4 This section and the next draw on collaborative work with Charles H. P. Zuckerman.

5 On the siaw1 ritual bond relationship in Laos, see Zuckerman (Citation2022).

References

- Adams, P. C. 2016. Placing the Anthropocene: A day in the life of an enviro-organism. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 41 (1):54–65. doi: 10.1111/tran.12103.

- Adams, P. C. 2017. Geographies of media and communication I: Metaphysics of encounter. Progress in Human Geography 41 (3):365–74. doi: 10.1177/0309132516628254.

- Adams, P. C. 2018. Geographies of media and communication II: Arcs of communication. Progress in Human Geography 42 (4):590–99. doi: 10.1177/0309132517702992.

- Adams, P. C. 2022. “Not a big climate change guy”: Semiotic gradients and climate discourse. Environmental Communication 16 (1):79–91. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2021.1964998.

- Adams, P. C., and J. Kotus. 2022. Place dialogue. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 47 (4):1090–1103. doi: 10.1111/tran.12554.

- ADB/UNEP. 2004. Greater Mekong subregion atlas of the environment. Manila: ADB and UNEP Regional Resources Centre for Asia and the Pacific, Pathumthani.

- Aikhenvald, A. Y. 2002. Language contact in Amazonia. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Aikhenvald, A., and R. M. W. Dixon. 2001. Areal diffusion and genetic inheritance. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Anderson, B., M. Kearnes, C. McFarlane, and D. Swanton. 2012. On assemblages and geography. Dialogues in Human Geography 2 (2):171–89. doi: 10.1177/2043820612449261.

- Angelo, H., and C. Hentschel. 2015. Interactions with infrastructure as windows into social worlds. City 19 (2–3):306–12. doi: 10.1080/13604813.2015.1015275.

- Appel, H., N. Anand, and A. Gupta. 2018. Temporality, politics, and the promise of infrastructure. In The promise of infrastructure, ed. H. Appel, N. Anand, and B. O’Neill, 1–38. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Aral, S., and M. Van Alstyne. 2011. The diversity-bandwidth trade-off. American Journal of Sociology 117 (1):90–171. doi: 10.1086/661238.

- Auer, P., and J. E. Schmidt, eds. 2009. Language and space: An international handbook of linguistic variation. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter. doi: 10.1515/9783110220278.

- Auer, P., and L. Wei, eds. 2007. Handbook of multilingualism and multilingual communication. Berlin, Germany: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Bahtina, D., and J. D. t Thije. 2013. Receptive multilingualism. In The encyclopedia of applied linguistics, ed. C. A. Chapelle, 1–6. Oxford: Blackwell. doi: 10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal1001.

- Bailey, A., L. Giangola, and M. T. Boykoff. 2014. How grammatical choice shapes media representations of climate (un)certainty. Environmental Communication 8 (2):197–215. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2014.906481.

- Baird, I. G. 2021. Catastrophic and slow violence: Thinking about the impacts of the Xe Pian Xe Namnoy dam in southern Laos. The Journal of Peasant Studies 48 (6):1167–86. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2020.1824181.

- Baird, I. G., and N. Quastel. 2015. Rescaling and reordering nature–society relations: The Nam Theun 2 hydropower dam and Laos–Thailand electricity networks. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 105 (6):1221–39. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2015.1064511.

- Baird, I. G., B. P. Shoemaker, and K. Manorom. 2015. The people and their river, the World Bank and its dam: Revisiting the Xe Bang Fai River in Laos: The people and their river revisited. Development and Change 46 (5):1080–1105. doi: 10.1111/dech.12186.

- Baird, I. G., and P. Vue. 2017. The ties that bind: The role of Hmong social networks in developing small-scale rubber cultivation in Laos. Mobilities 12 (1):136–54. doi: 10.1080/17450101.2015.1016821.

- Barabási, A.-L., and R. Albert. 1999. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science 286 (5439):509–12. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.509.

- Bennett, J. 2005. The agency of assemblages and the North American blackout. Public Culture 17 (3):445–66. doi: 10.1215/08992363-17-3-445.

- Blok, A., M. Nakazora, and B. R. Winthereik. 2016. Infrastructuring environments. Science as Culture 25 (1):1–22. doi: 10.1080/09505431.2015.1081500.

- Boas, F. 1910. Psychological problems in anthropology. The American Journal of Psychology 21 (3):371. doi: 10.2307/1413347.

- Boas, F. 1911. Introduction. In Handbook of American Indian languages, ed. F. Boas, 5–83. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

- Bolsen, T., and M. A. Shapiro. 2018. The US news media, polarization on climate change, and pathways to effective communication. Environmental Communication 12 (2):149–63. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2017.1397039.

- Bowman, I. 1904. A typical case of stream-capture in Michigan. The Journal of Geology 12 (4):326–34. doi: 10.1086/621160.

- Brashears, M. E., and E. Quintane. 2018. The weakness of tie strength. Social Networks 55:104–15. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2018.05.010.

- Brickell, K. 2013. Towards geographies of speech: Proverbial utterances of home in contemporary Vietnam: Towards geographies of speech. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 38 (2):207–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-5661.2012.00503.x.

- Bromham, L., R. Dinnage, H. Skirgård, A. Ritchie, M. Cardillo, F. Meakins, S. Greenhill, and X. Hua. 2022. Global predictors of language endangerment and the future of linguistic diversity. Nature Ecology & Evolution 6 (2):163–73. doi: 10.1038/s41559-021-01604-y.

- Burt, R. S. 1992. Structural holes: The social structure of competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Callon, M. 1986. Some elements of a sociology of translation: Domestication of the scallops and the fishermen of St Brieuc Bay. In Power, action and belief: A new sociology of knowledge?, ed. J. Law 196–223. London and New York: Routledge. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.1984.tb00113.x.

- Chamberlain, J. R. 2020. Vanishing nomads: Languages and peoples of Nakai, Laos, and adjacent areas. In Handbook of the changing world language map, ed. S. D. Brunn and R. Kehrein, 1589–1605. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-02438-3_17.

- Chappell, H. 2001. Language contact and areal diffusion in Sinitic languages. In Areal diffusion and genetic inheritance, ed. A. Y. Aikhenvald and R. M. W. Dixon, 328–57. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Comrie, B. 2020. Mapping the world’s languages: From data via purpose to representation. In Handbook of the changing world language map, ed. S. D. Brunn and R. Kehrein, 61–76. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-02438-3_131.

- Crosby, I. B. 1937. Methods of stream piracy. The Journal of Geology 45 (5):465–86. doi: 10.1086/624559.

- DeLanda, M. 2006. A new philosophy of society: Assemblage theory and social complexity. London: Continuum.

- DeLanda, M. 2016. Assemblage theory. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press.

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 1987. A thousand plateaus. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Dennett, D. C. 1995. Darwin’s dangerous idea. London: Penguin.

- Descloux, S., P. Guedant, D. Phommachanh, and R. Luthi. 2016. Main features of the Nam Theun 2 hydroelectric project (Lao PDR) and the associated environmental monitoring programmes. Hydroécologie Appliquée 19:5–25. doi: 10.1051/hydro/2014005.

- Di Nunzio, M. 2018. Anthropology of infrastructure. Governing Infrastructure Interfaces – Research Notes 1:1–4.

- Dixon, R. M. W. 1997. The rise and fall of languages. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.