Abstract

This article examines the political consequences of environmental nongovernment organization (ENGO) involvement in protected area conservation in Australia. Rapid growth of a nongovernment protected area (NGPA) estate this century has involved a range of individuals, communities, First Nations, and ENGOs, and has been closely tied to government policy and private finance. Although NGPA conservation achievements have been profound, there has been limited examination of what expanded nongovernment involvement, responsibility, and leadership mean for the practice and governance of nature conservation. Thematic analysis of twenty-four key informant interviews and selective gray literature identifies how financing, accountability, and partisan politics are emerging as key domains in shaping an NGPA estate that reflects a closer alignment with capital and market forces. ENGOs are playing a key role in crafting new political conditions for protected area conservation, where their role in neoliberal governance is not just service delivery, but statecraft and agenda setting. ENGOs are increasingly casting protected area conservation as apolitical, and thereby a bipartisan activity, driven by a “pragmatic” agenda that seeks to secure private financing for land ownership and management obligations. Frameworks of accountability to donors shape ENGO practices and conceptions of conservation through exposure to novel market mechanisms. As a result, ENGO operation permits limited space for plural, ideological, and structural debate about protected area conservation, the public interest, and the root causes of ecological crises to which it responds. The embrace of conservation led by nongovernment actors marks a substantive shift from the formative politics of ENGOs in Australia.

本文探讨了环境非政府组织(ENGO)参与澳大利亚保护区的政治后果。自2000年以来, 非政府保护区(NGPA)快速发展, 涉及到一系列的个人、社区、原住民和ENGO, 并与政府政策和私人融资密切相关。尽管NGPA取得了巨大的保护成果, 但很少研究扩大非政府的参与、责任和领导对自然保护实践和治理的影响。通过对24位关键人物的采访和对部分“灰色文献”的主题分析, 本文确定了融资、责任和党派政治如何成为塑造反映资本和市场力更密切关系的NGPA的关键领域。在为保护区创造新的政治条件方面, ENGO正在发挥着关键作用。ENGO在新自由主义治理中的作用, 不仅是提供服务, 还包括治国方略和议程制定。ENGO受到旨在确保私人融资用于土地所有权和管理义务的“务实”议程的驱动, 越来越多地将保护区视为非政治性的两党活动。通过市场新机制, 捐助者责任框架塑造了ENGO的保护实践和理念。因此, 对于自然保护、公共利益和生态危机的根源的多元、意识形态和结构性的辩论, ENGO提供了有限的空间。由非政府行为者领导环境保护, 标志着澳大利亚ENGO政治的实质性转变。

Este artículo examina las consecuencias políticas del involucramiento de organizaciones ambientales no gubernamentales (ONG ambientales) en la conservación de áreas protegidas en Australia. El rápido crecimiento del patrimonio de un área protegida no gubernamental (NGPA) durante el siglo actual ha implicado una variedad de individuos, comunidades, Primeras Naciones, y ONG ambientales, y ha estado estrechamente vinculado a la política gubernamental y a la financiación privada. Aunque los logros conservacionistas de las NGPA han sido profundos, muy poco se ha examinado lo que significa la mayor la participación no gubernamental, su responsabilidad y liderazgo para la práctica y gobernanza de la conservación de la naturaleza. El análisis temático de veinticuatro entrevistas clave y de una selección de la literatura gris muestra cómo la financiación, la rendición de cuentas y la política partidista están surgiendo como los dominios cruciales para configurar el patrimonio de las NGPA, reflejando una alineación más estrecha con las fuerzas del capital y del mercado. Las ONG ambientales están jugando un rol clave para la creación de nuevas condiciones políticas en la conservación de áreas protegidas, donde su rol en la gobernanza neoliberal no solo es la prestación del servicio, sino también su influencia en la política y en la formulación de agenda. Las ONG ambientales cada vez más intervienen para que la conservación en las áreas protegidas sea apolítica y de esa manera actividad bipartidista, orientada por una agenda “pragmática” que busque asegurar la financiación privada para la propiedad de la tierra y las obligaciones de manejo. Los marcos de rendición de cuentas a los donantes configuran las prácticas y concepciones de la conservación de las ONG ambientales a través de la exposición a nuevos mecanismos de mercado. Como resultado, la operación de las ONG ambientales permite un espacio limitado para el debate plural, ideológico y estructural acerca de la conservación de áreas protegidas, el interés público y las causas profundas de las crisis ecológicas por las cuales responde. La adopción de la conservación orientada por actores no gubernamentales marca un cambio sustantivo desde las políticas formativas de las ONG ambientales en Australia.

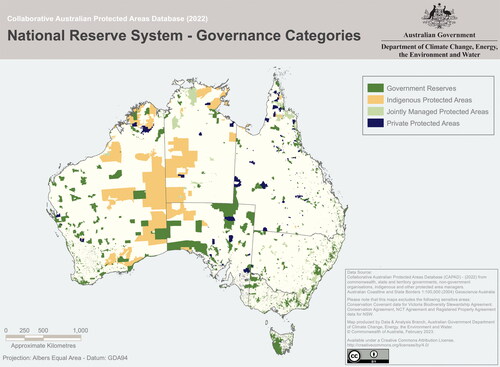

The growing involvement of nongovernment actors in protected areas over the last twenty-five years in Australia has profoundly altered the geography of nature conservation (see ). In the mid-1990s, Australia’s protected areas were almost entirely on public lands and managed by domestic governments. Now 250 percent larger, Australia’s National Reserve System (NRS) encompasses local to global networks of governance, finance, and collaboration across diverse land tenures. Almost all (97 percent) additions to the NRS since 1997 have been on private, leasehold, and First Nations–held lands (Commonwealth of Australia Citation1997, Citation2021). This nongovernment protected area (NGPA) estate now encompasses 12 percent of Australia’s terrestrial surface (Davison et al. Citation2023). Following Brockington, Duffy, and Igoe (Citation2008), we understand the diverse array of public and private actors involved in the NGPA estate as constituting a discrete sector of social and ecological activity, a sector becoming more prominent, coherent, and cohesive over time. The expansion and solidifying of the NGPA sector has also seen nongovernment actors play more empowered roles in conservation efforts to prevent biodiversity loss, including threatened species management (Selinske et al. Citation2017; Archibald et al. Citation2020; Ivanova and Cook Citation2020; Palfrey, Oldekop, and Holmes Citation2022).

Figure 1. The National Reserve System in Australia showing the different categories of protection, including the extent of Private Protected Areas (a key focus of our analysis) and Indigenous Protected Areas. Source: Map produced by Geospatial & Information Analytics Branch, Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment. © Commonwealth of Australia, March 2021.

The shifting geography of Australia’s protected area estate embodies the neoliberal transformation of environmental governance in liberal democracies over recent decades (Holmes and Cavanagh Citation2016). In Australia, the state has rolled back direct public funding and capability for protected area conservation (Higgins, Dibden, and Cocklin Citation2012; Cooke and Lane Citation2020), simultaneously rolling out policies and programs that encourage nonstate actors to participate on terms set by the state (Cooke and Lane Citation2018; Iannuzzi, Santos, and Mourato Citation2020). The scale of state devolution and growing opportunities for nongovernment actors to fill the resulting capability gap means that some environmental nongovernmental organizations (ENGOs) now “look and act increasingly like a morph between trans-national corporations and government development agencies” (Jepson Citation2005, 516).

The neoliberal project partly arose from and has extended the ability of private interests aligned with capital accumulation to reshape state functioning (Harvey Citation2007). The resulting convergence of electoral and economic interests has helped refashion environmental politics in countries such as Australia. In the case of the NGPA sector, this has meant that ENGOs are tightly bound in interdependent networks with state, philanthropic, and for-profit interests (Nasiritousi Citation2019). Operating in this role, the achievements of ENGOs (most notably land conservancies) include acquiring millions of hectares of rare or threatened ecologies for conservation, leveraging millions of dollars in philanthropic donations, and providing avenues for some First Nations to care for their lands (J. Fitzsimons, personal communication, 20 October 2021; see also Fitzsimons Citation2015; Davison et al. Citation2023). ENGOs have also adopted responsibility for delivering conservation science, policy innovation, and consensus building (all previously expected of the state), as well as the formal delivery of some government programs, such as conservation covenant (easement) programs (Davison et al. Citation2023). To date, there is limited analysis of the influence of neoliberal reforms in protected area conservation in Australia.

The establishment of a peak body for the NGPA estate in Australia in 2014—the Australian Land Conservation Alliance (ALCA)—provides an instructive example of the need to explore the political implications of the changing NGPA sector. In 2018, ALCA published a conservation finance scoping paper, “Expanding Finance Opportunities to Support Private Land Conservation in Australia” (Ward and Lassen Citation2018). Funded by the federal government, this scoping paper reflects a narrative that has been central to shaping the Australian NGPA estate. This narrative defines a compelling “problem”—a lack of adequate conservation finance to enable private land to contribute to an urgent conservation need—to which it offers a pragmatic “solution”—expanding the pool of private conservation finance and public–private partnerships (PPPs; Ward and Lassen Citation2018, 31). In this narrative, the NGPA sector is presented as an innovative leader in delivering this solution through new streams of conservation funding, often by leveraging existing partnerships and investments. Ongoing expansion of the NGPA estate within a market-orientated framework then becomes imperative in responding to escalating conservation challenges. One strategy suggested to expand nongovernment conservation finance involves avoiding “the use of highly politicised and ideologically-entwined words. For example, the word ‘environment’ can be a powerful barrier to increasing support for conservation in the mainstream Australian community” (Ward and Lassen Citation2018, 38).

ENGO engagement with markets to address ecological concerns is not new (Igoe and Brockington Citation2007; Brockington, Duffy, and Igoe Citation2008; Larsen and Brockington Citation2018). The ALCA scoping paper, however, accords with a view that conservation has “never before been so enthusiastic about the potential for capitalist solutions to conservation problems” (Holmes Citation2012, 188; see also Brockington and Duffy Citation2010; Mallin et al. Citation2019; Beer Citation2023; Damiens, Davison, and Cooke Citation2023; Louder and Bosak Citation2023). How, we ask, did we get here, and what might be the consequences? We begin by tracing the origins of market logics and mechanisms in Australian national policy areas, those that were once “non-market spheres of allocation” (Beeson and Firth Citation1998, 229); changes that signaled an emerging neoliberal political rationality.

The Shifting Role of ENGOs and the State in Australian Conservation Governance

Australia’s NGPA sector is today shaped by a different set of political ambitions to those of the conservation movement of the 1970s and 1980s, which primarily sat outside government and were largely oriented toward activist and adversarial forms of environmentalist politics (Doyle Citation2000). Prior to the 1980s, environmental governance was mostly the province of individual Australian states. A series of high-profile environmental conflicts saw the federal government become a powerful player in environmental politics (Crowley Citation2021). Emerging and established ENGOs in Australia enjoyed notable success at this time, adopting a largely activist and obstructionist stance that drove regulatory intervention. During the 1980s, the previously local focus of much environmental protest shifted to the national and international scale, putting the environment on the national political agenda (Mulligan and Hill Citation2001). For example, direct action in Australia’s Wet Tropics halted major logging operations and shaped a course for World Heritage listing, and blockades of the Franklin River in Tasmania halted the construction of a hydroelectric dam and propelled the creation of a national “green” party in Australia (Toyne Citation1994). Although selective in its interventions in a manner that aligned with its own political interests, the Labor Federal Government under Bob Hawke demonstrated a willingness for regulatory intervention in response to the concerted and direct efforts of ENGOs and an increasingly engaged citizenry (Doyle Citation1990, Citation2000).

The direct action of ENGOs and the resultant national environmental regulatory interventions of the 1980s coincided with a period of significant political and economic restructuring in Australia. A major economic reform agenda was underway amidst concerns about Australia’s lack of economic competitiveness on the international stage (Beeson and Firth Citation1998). A series of government reports reflected a view that competing in global markets would require—amongst other things—a business-like rationality for public policymaking (McEachern Citation1993; Doyle Citation2000). This included adopting more competitive market principles in policy design and reorganizing a national bureaucracy to prioritize technocratic expertise (Beeson and Firth Citation1998; Doyle Citation2000). These changes ultimately paved the way for outsourcing public sector responsibilities and consolidating bureaucratic power at the managerial level through the 1990s and Citation2000s.

The waning zeal for federal interventionism in environmental conflicts by the late 1980s saw environmental policy subsumed by economic interests (Crowley Citation2021). Moreover, the rise of an ecologically sustainable development (ESD) agenda (the Australian variant of the emerging global sustainable development agenda) offered a pathway for remaking environmental governance through closer alignment with economic objectives. The Federal Labor government used ESD as a gateway to a less confrontational environmental politics, where environment and economic representatives could “sit around the table” and craft a collaborative approach to environmental issues and economic development (Doyle Citation2000; Staples Citation2012). This era saw many of the activist ENGOs of the 1980s become participants in “consensus” politics, working with and consulting government “from the position of ‘insiders’” (Staples Citation2012, 170). As such, environmental interests that remained “outsiders” were framed by government and corporate interests alike as “obstructionist” to a new age of cooperation (Doyle Citation1990). The tightening alignment of nature conservation and capital accumulation over the first two decades of this century reflects a profound shift from the environmental politics of the 1980s that identified capital accumulation as the central mechanism of the destruction of nature (Büscher and Fletcher Citation2020).

This article builds from existing work on ENGOs that document the shift from adversarial politics to active participation in statecraft and market-orientated environmentalism (Doyle Citation1990; Doyle, McEachern, and MacGregor Citation2015; Davison et al. Citation2023), to explore its particular contemporary implications in the context of protected area nature conservation. We focus specifically on how ENGOs have helped to craft the diverse constituencies engaged in and affected by the NGPA estate, what different and potentially competing interests are served through this mode of protected area conservation, and how the benefits of the NGPA estate are accrued and understood. We explore the political implications of NGPA conservation under the themes of finance, accountability, and depoliticization, which emerged inductively through our analysis of qualitative findings. We use these themes to show how ENGO activity in the NPGA estate embodies the pragmatism of formative consensus-building environmental politics, in the context of the rapid financialization and privatization of nature conservation.

Our analysis is not exhaustive, but identifies the overarching alignment of political and economic interests in conservation embodied in the NGPA sector. The majority of our insights here draw from the Private Protected Area () estate (which includes some partnership arrangements between ENGOs and First Nations), although many key informants had knowledge and experience in Indigenous Protected Areas, which they also drew on in their discussions. Forthcoming publications will explore specific political effects related to conservation subsectors and land tenures in more specific detail, such as Indigenous Protected Areas and ranger programs, the technologies of protected area conservation, and issues of long-term security of conservation outcomes on land that has been designated for protection.

Research Design

The study reported here is guided by the following research question: What have been the political consequences of ENGO participation in the emergence and consolidation of the NGPA estate for nature conservation and its governance? Our focus on politics goes beyond formal political institutions to encompass flows of power through social-ecological relationships, including those usually delimited as economic (Fletcher Citation2010; Neumann Citation2015; Büscher and Fletcher Citation2020). We draw on analysis of interviews with key informants and a purposive sample of documents. Key informant interviews centered on actors in government agencies, ENGOs, and private businesses at local, subnational, national, and international scales, who were central to the emergence of the NGPA sector. Interviews considered the changing roles of ENGOs in the NGPA estate across time, among other topics. Participants included sixteen men and eight women who had occupied numerous roles relevant to nature conservation and protected area management, with many working in multiple organizations, including the Australian Land Conservation Alliance; Bush Heritage Australia (hereafter Bush Heritage); Commonwealth Department of Agriculture, Water, and the Environment; Commonwealth Department of Environment (or Energy and Environment); Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization; Environment Victoria; Gondwana Link; Australian Greens Party; International Union for Conservation of Nature; Landcare Australia; National Parks and Wildlife Service NSW; North Australian Indigenous Land and Sea Management Alliance; Odonata Investments; Parks Australia; Pew Charitable Trust; Tasmanian Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment; Tasmanian Land Conservancy; The Nature Conservancy; The Wilderness Society; Trust for Nature, Victoria; and Victorian National Parks Alliance. Participant roles included independent activists, consultants, research scientists, and members of local environmental groups.

Key informant interviews (n = 24) were conducted between December 2018 and November 2019, in line with an informed consent research ethics protocol (Tasmanian Social Science Human Research Ethics Committee H0017689). The majority of the interviews (n = 21) were performed by one of two coauthors (Benjamin Cooke and Aidan Davison). Interviews lasted an average of sixty-eight minutes (range = 45–106 minutes). Most were conducted in person (n = 16), with eight conducted online. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed by a professional service. Participants chose to be identified or anonymous and were given the opportunity to review their transcript. We refer to participants by a code (P01–P24) or, where given permission, by name and deidentified code (P). Interview questions explored the implications of the growth of the NGPA estate, current challenges or opportunities, and the future for protected areas.

Data were analyzed thematically using NVivo 12 software (QSR International). A hierarchical coding tree of 183 codes across four tiers was developed. Deductive coding was primarily descriptive and driven by research questions, matrix categories, and literature. Inductive coding involved an analytical process of open coding, memoing, categorizing, clustering, pattern identification, and sorting. We read across transcripts and codes to identify significant conceptual themes (Cope and Kurtz Citation2017). Themes emerging from interviews were triangulated with key gray (institutional) literature associated with the NGPA sector.

The Politics of the NGPA Estate

In this section we explore the influence and contribution of ENGOs in the emergence of a NGPA estate since the late 1990s, with respect to the themes of financing, accountability regimes, and the depoliticization of protected area conservation. These themes emerged inductively from the analysis of the interviews with key informants described earlier. Our analysis centers on the roles of ENGOs as mediators, coordinators, and translators of neoliberal conservation governance, and the entwining of philanthropic donation, for-profit investment, and private interests in shaping the politics of ENGOs involved in the NGPA estate.

Bridging the Conservation Finance Gap

The NGPA sector has been driven by a widespread perception within environmental movements and environmental professions that nature conservation is chronically underfunded in Australia, a situation exacerbated by worsening conservation problems (Ward and Lassen Citation2018). Until the 1990s, ENGOs focused predominantly on advocating for the responsibility of governments to fund conservation on public lands (Doyle Citation2000). Following the neoliberal economic restructuring of the late 1980s and 1990s discussed earlier, however, conservationists became worried that public funding might become increasingly erratic, opportunistic, short-term, and scarce (Davison et al. Citation2023). In response to these concerns, the emerging NGPA sector has focused on two domains of funding in addition to direct government funding: (1) philanthropic giving (no financial returns but conservation outcomes expected), and (2) private investment (financial returns and conservation outcomes expected; Ward and Lassen Citation2018, 29). As evidenced by ALCA’s conservation finance scoping paper, there is little confidence within the NGPA sector that what they regard as adequate public funding for conservation will be forthcoming anytime soon (Ward and Lassen Citation2018). According to some key informants, any prospect for increased federal funding for conservation depends on further neoliberal privatization of public assets. As one key informant involved in the establishment of the National Reserve System observed, “unless there’s another big public sale of an asset … it’s hard to see where [conservation funding] comes from” (P18).

The privatization of public assets to fund conservation has a powerful precedent in Australia, with $1.35 billion from the initial sale of the national communications network, Telstra, used to create the National Heritage Trust (NHT) in 1997. This sale was a key step in the convergence of neoliberal reform and conservation governance. The NHT promised public good benefits in the form of conservation funding while increasing the electoral palatability of state withdrawal from public services (Davison et al. Citation2023). Later iterations of the NHT (renamed the Caring for Country program) were used to develop a public–private cofunding model to extend Australia’s protected area estate, the NRS, in the late 1990s. The NRS is the basis on which the federal government reports on progress against the Convention on Biological Diversity target of 30 percent terrestrial protected area coverage by 2030.

NHT funding was directly responsible for the rapid growth of the NGPA estate and land conservancy organizations. The federal cofunding model offered ENGOs one-third of the purchase price for high-conservation-value private land, provided the remainder was secured from other sources (often large philanthropic donations). The abrupt end of this federal funding in 2013 precipitated a sudden decline in ENGO land acquisitions (Kirkpatrick et al. Citation2022) and set ENGOs the financial challenge of meeting the costs of managing a growing estate from private sources. Key informant Louise Gilfedder, a former director of Bush Heritage, described this as effectively marking “the complete disappearance of [the NRS]” (P) as a public policy agenda. Key informants indicated that they were aware of the tension between ENGOs’ growing capability to attract philanthropic and other private funding and the tacit permission this could offer state actors to further reduce public conservation funding (Torpey-Saboe Citation2015).

The NHT cofunding model built ENGO capacity to grow and diversify private funding networks while redirecting the responsibility for protected area conservation from public to private landholders, in a seemingly textbook case of neoliberal transformation from state-led to market-led delivery of public good outcomes (Tickell and Peck Citation2002; Morris Citation2008). The goal of such policies is to leverage government funding to create new streams of private funding that can then obviate need for the further government funding, “conditioning” ENGOs to a neoliberal reality of government funding scarcity in the process.

Although predicted by research on neoliberal governance, the withdrawal of federal funding for the NRS was not anticipated to be a logical outcome of neoliberal governance by most of our key informants, who saw the leveraging of public funding to increase flows of private funding as a necessary and ongoing solution to a structural and perennial conservation funding deficit. The withdrawal of federal funding was interpreted by some as an arbitrary, ideologically motivated decision resulting from government ambivalence, if not hostility, toward the environment movement. Furthermore, the failure to anticipate a strategic withdrawal of public investment, combined with the dramatic growth in ENGO land estates and management costs, and the related growing expectations held by both these organizations and their donors and partners, made ENGOs particularly vulnerable to reduced public funding. The resulting intensified imperative to tap reliable and growing flows of investment elsewhere saw ENGOs rapidly experiment, innovate, and partner with private interests.

As a further complication, some participants noted that opportunities to attract philanthropic funding have declined as public funding for the NGPA estate has reduced. The withdrawal of government funding has sparked hesitation in some potential donors who see it as an indication of poor state commitment to conservation and a harbinger of poor policy regimes that might compromise the long-term security of their gift. As the Nature Conservancy’s director of conservation in Australia, James Fitzsimons noted, private money is being “left on the table” because the federal government has not demonstrated direct investment in the public good outcomes of the NGPA sector. Here we see the patchiness of “actually existing neoliberalisms” (Brenner and Theodore Citation2002, 351), with ongoing government action needed to realize neoliberal objectives. Policy frameworks and public funding are critical for ENGOs that are attempting to secure private funding to translate broad state policies into concrete outcomes (Trudeau and Veronis Citation2009).

As evident in the ALCA scoping paper, increasing scarcity of government funding alongside increasing species extinction and habitat loss drive what ENGOs frame as a pragmatic turn to private funding sources to maintain the scope and scale of their activities (Davison et al. Citation2023). Framed as the pragmatic challenge of addressing the conservation financing gap, some key informants saw reduced state funding as an opportunity for innovation. These informants emphasized the potential for new private funders and the chance to craft novel market mechanisms to access new funding streams. The wider governance and political implications of how funding is sourced, including who it is sourced from, were largely absent from participant and organizational narratives. Framed as pragmatism, the conservation funding imperative is reduced to a matter of instrumental means for achieving the ultimate and self-evidently good end of conservation. We examine the wider political implications of this pragmatism later in the discussion but here note that although key informants saw this pragmatic turn as a simple reflection of the core mission of ENGOs, many also described the changes this pragmatism has brought about in the functioning of ENGOs. One participant explained these changes as the rise of a:

really risk averse culture. … Unfortunately it seems to be a trend with NGOs. Once they reach a certain size they start getting some really wealthy good donors that make the budget look really good, and there seems to be this innate tendency to suddenly think, “Oh, we’ve got to do everything that these donors want, because we won’t be viable unless we do.” (P13)

Experiments with for-profit conservation in Australia are also not new but reach back into the origins of the NGPA sector in the 1990s (Davison et al. Citation2023). Earth Sanctuaries Limited (ESL) was the first private conservation business in Citation2000 to trade shares on the Australian Stock Market.Footnote1 Indeed, it was proclaimed by its owners to be “the world’s first listed conservation company” (Wamsley and Davey Citation2020, 119). ESL’s shares were presented as self-generating and regenerating assets based on attributing dollar values to native animals in their sanctuaries. This early experiment in generating a direct return to investors through conservation activities was unsuccessful, with ESL declaring bankruptcy in 2006. The ambition to overcome a growing funding gap, however, has seen experiments with the financialization of ecologies and market approaches advance at great pace (Apostolopoulou et al. Citation2021). Some participants were enthusiastic about what they saw as the transformative potential of private investment: “Investors want to do good, they just don’t know where to go. … You do good and you make just as much money! You can really dream big if money is not the limitation” (P06).

Working in impact investing (the goal of generating financial returns alongside social or environmental benefits), the participant just quoted saw regenerative agriculture as a promising market mechanism for driving conservation financing. The model here is that investors enable conservation activity that supports profitable forms of regenerative agricultural production, which produces price premiums that deliver a return on investment. This participant was confident that through such models, conservation finance could “unlock the private sector value in nature” (P06). Another participant was also bullish about such opportunities and saw the “private sector and the NGO movement [providing] policy leadership” (P12) in facilitating private investment in conservation. Participants in support of for-profit conservation investment appeared increasingly comfortable with repositioning the responsibility of the state from funding toward facilitating and endorsing the NGPA sector. This participant suggested that government is “more willing to talk to us because they know we don’t need their money … but we need their buy-in to support what we do” (P23). Here nongovernment funding is positioned as a vehicle for positively reconfiguring ENGOs and government collaboration. In this collaboration, governments have a role to build policies and programs around diversified private funding streams, thereby enabling ENGO leadership in protected area conservation.

Those key informants who were less enthusiastic about for-profit conservation investment generally reflected a concern of ALCA that “the single most challenging aspect of accessing private sector support for conservation is to identify conservation projects that can generate a financial return” (Ward and Lassen Citation2018, 69). Rather than concern about the political-economic effects of directly linking nature conservation to capital accumulation (Dempsey and Bigger Citation2019; Büscher and Fletcher Citation2020), this challenge was presented as a primarily practical one. With the necessity of private funding taken for granted, questions about how to make conservation profitable were presented as pragmatic questions of achieving the right policy settings or partner engagement. The prospect that linking conservation and capital accumulation might transform the goals and activities of conservation in ways that might compromise those initial goals did not feature in our interviews.

In the absence of a state delivery apparatus, enthusiasm for working with business and operationalizing policy has not only become entrenched but has been seen as necessary for securing the NGPA sector’s future. The task of filling the gap left by the state is considered daunting by many key informants, but some perceive the opportunity of an increasing array of “market-based” financing opportunities as a genuine pathway to achieving this goal. Most notable, however, is the shifting position of ENGOs within networks of consensus building and policymaking in environmental governance (Doyle Citation2000); ENGOs involved in the NGPA estate are now more likely to be the party actively orchestrating and building consensus around policy proposals with government and private interests, as opposed to being invited to the table by government to participate.

Regimes of Accountability: For What and to Whom?

Prior to the twenty-first century, almost all protected areas in Australia were on public lands and thus fell under government frameworks of democratic accountability and public administration. The growing scale, influence, and resources of the NGPA sector, combined with growing reliance on private finance, raise questions about to whom and for what protected area conservation on nongovernment lands is accountable (Jepson Citation2005). As Balboa (Citation2017) noted, although increasingly bound together in regimes of neoliberal governance, government and nongovernment actors are likely to provide “different answers to the questions ‘accountable for what?’ and ‘how?’” (111). Increasingly, regimes of accountability operate more broadly as modes of neoliberal governance that reflect the subsuming of public interests under market rationalities (McEachern Citation1993). We argue that the ways in which ENGOs conceive of and practice accountability are central to understanding the political consequences of the rise and operation of the NGPA sector. This is especially relevant in light of the active governance stance adopted by ENGOs with relation to conservation financing discussed earlier (Jepson Citation2005; Balboa Citation2017).

Our key informants are influential advocates of the national importance of nature conservation. Yet, when asked about public interest and wider benefits of the NGPA sector, few raised the democratic context of nature conservation. Instead, “accountability” was frequently deployed to present the NGPA sector in a transactional and contractual register, similar to that of the private sector (Jepson Citation2005; Raymond Citation2012). Drawn from accounting practice, a distinction between upstream (or upward) and downstream (or downward) accountability is commonly used to differentiate two key considerations in transactional accountability (Ebrahim Citation2003; Unerman and O’Dwyer Citation2010). Upstream accountability is characterized as a need to establish a return on investment (often to shareholders), whereas downstream accountability establishes that the needs of beneficiaries have been met (often framed as customer satisfaction).

Within the NGPA sector, accountability discourse has grown in influence, with particular emphasis placed on upstream accountability to funders. Although democratic narratives linking nature conservation to the national and global public good remain rhetorically important, they might have less influence on the everyday accountability practices of ENGOs. Here we see the potential realization of Jepson’s (Citation2005) warning that “faced with calls for greater accountability there is a risk that ENGOs might apply accountability regimes uncritically from the business or private sector” (515). Accountability rhetoric highlights how the ambition of ENGOs to diversify and expand private funding streams has heightened attention on the needs, expectations, and ambitions of funders. Reflecting an increased reliance of NGPA actors on for-profit investment as well as nonprofit donation, neoliberal innovation had made it “increasingly difficult to say what is philanthropy, what is a commercial transaction, and what is an investment” (Raymond Citation2012, 9). This convergence of altruism and business is increasingly framed through debate about philanthrocapitalism, or the adoption of market-based techniques and strategies in benevolent giving (Betsill et al. Citation2022). A key concern here is the growing potential for philanthropy to be used to shape social, policy, and media contexts of conservation in favor of aligned economic and political interests (Hay and Muller Citation2014; Holmes Citation2015; Cohen and Rosenman Citation2020; Beer Citation2023). Specifically, there is the risk that superrich philanthropists are increasingly granted a governance capacity to “diagnose socio-environmental problems and prescribe the right solutions on behalf of society” (Beer Citation2023, 8).

The specific mechanisms of accountability highlighted by key informants were often related to ENGO interests in attracting and satisfying funders (Davison et al. Citation2023). As Jane Hutchinson, former CEO of Tasmanian Land Conservancy and executive director of the Nature Conservancy (Australia) observed: “Every time I go and talk to a high end donor or a business … they look straight at the financials. Number one.” Doug Humann, former Bush Heritage chief executive and chairman of Landcare Australia, noted: “We had a very large donor … and he required … very sophisticated reporting to demonstrate that his money was being effectively spent.” The emphasis on financial accountability to donors reflects ENGO efforts to differentiate themselves by actively pitching the novel ways in which they report on returns. As one key informant managing partner relationships for an ENGO explained:

If we can show that the act of managing land well has a benefit and that we can create a demand for that product, then we can create a new income stream to protect it. … If … we can say we know what that [benefit] is in a unit measure in terms of improvement in biodiversity outcomes, then if someone wants to pay for that—we have a market. (P10)

Although conservation science has played a vital role in providing policy justification and public legitimacy for protected areas, its more recent role in underpinning quasi-private accountability frameworks raises concerns about potential for conflict between these functions. Here we see the risk that financialized justifications can produce “hierarchies … [of nonhumans that] might attract capital” (Cohen and Rosenman Citation2020, 1267). Such “cherry-picking” (Turnhout, Neves, and De Lijster Citation2014, 583) of conservation objectives aligns conservation goals with the interests of philanthropists and investors (Beer Citation2023), solidifying consensus that capitalist environmentalism is a necessary component of conservation action (Cohen and Rosenman Citation2020). The association of science and private capital in particular highlights the role of science in creating “marketable knowledge products” (Drakopulos Citation2022, 118). In Australia, these practices are also set against a backdrop of scathing recent reviews into the ineffectiveness of conservation efforts, with an overemphasis on market instruments like ecological offsets considered particularly problematic (Greaves Citation2021; Goodwin Citation2022). The accountability practices at play here reflect wider patterns of neoliberal governance in simplifying and atomizing ecologies into discrete units of nature (numbers of wombats), so that legible markets and financial accounting practices can be instituted (Robertson Citation2004; Turnhout, Neves, and De Lijster Citation2014).

The growing concern of ENGOs with their accountability to private funders was linked in some key informant interviews with a perception that ENGOs ought not be subject to scrutiny in relation to the public interest. Doug Humann, for example, argued that questions of public interest should be the domain of government. A notable exception to efforts by ENGOs to resist responsibility for public forms of accountability relates to some recent engagements with First Nations. The Indigenous protected estate now comprises an area as large as the public and private estates combined (Davison et al. Citation2023). Many ENGOs have broken decisively with older environmentalist narratives about wilderness to recognize the fact that ecologies on this continent are the product of cultural management by First Nations people (Ngurra et al. Citation2019; Damiens, Davison, and Cooke Citation2023). ENGO activities increasingly seek to integrate Indigenous and Western scientific forms of ecological knowledge, to support conservation training and management and learning on country programs, and to identify opportunities to hand land back to First Nations.

This recognition of ENGO responsibility to decolonize conservation in the settler-colonial contexts of Australia that continue to dispossess and disenfranchise First Nations is entirely welcome. Yet, it also further complicates the relations of accountability expressed in the NGPA sector, offering insights into the way that accountability rhetoric can highlight how certain interests get prioritized over others (Aldashev and Vallino Citation2019). This includes competing accountability between addressing settler-colonialism and protecting “priority landscapes” for threatened species, driven by philanthropic donors who want to “see where their money went” (P13). For example, Bush Heritage have promoted their collaborations with First Nations peoples in places like the Tasmanian Midlands. As one participant noted, however, the colonial history of this region and ongoing dispossession bring deeper tensions to the surface:

We’ve got the Midlands as the priority landscape, which any Tasmanian knows, we’re talking about big wealthy landowners, who acquired this land off the—well took this land off the Aboriginal community when they first settled, and now we have an NGO coming in and helping these big wealthy landowners fix up the land that they have basically destroyed. So there are obvious questions about why that’s the priority? (P13)

The rapid expansion of the NGPA sector reflects the ability of ENGOs to harness private investment and broker political support. Here we see that this productive relationship between ENGOs and conservation philanthropists and investors has drawn ENGOs into the front lines of neoliberal experimentation in the form of emerging market mechanisms for conservation, as they compete for funding in an increasingly crowded and diversified field. It also exposes ENGOs to the potential influence of investors that seek to affect significant influence over ENGO direction or operations. Indeed, private funding is likely to continue shifting from a gift-giving orientation, where donors fund broader NGO ambitions with limited accountability processes, to “investment targeted at a problem” (Hay and Muller Citation2014, 638; see also Raymond Citation2012) where market-orientated relations direct specific, evaluated outcomes. The application of accountability mechanisms by ENGOs captures the tensions between private funding and public interest, where an adherence to market mechanisms risks a narrowing of pluralist, democratic politics and a reduced emphasis on advocacy for transformative governance in the public sphere (Staples Citation2012).

Depoliticizing Conservation

ENGOs in the NGPA sector have intentionally distanced themselves from issues and debates that could potentially alienate funders and governments. In the process, they have also sought to distinguish themselves from ENGOs that profess political motivations, particularly those that identify themselves with radical or activist forms of environmentalism (Jepson Citation2005). Some NGPA actors, like the Nature Foundation of South Australia, for example, explicitly state that they are an “apolitical organization” on their home page. More generally, however, apolitical positioning is more implicit, as in the conspicuous absence of the highly contentious and polarizing issue of climate change on the Web sites and publications of NGPA organizations, which instead foreground upbeat messages of environmental recovery (Damiens, Davison, and Cooke Citation2023).

One key informant described the impact of the election of the Howard Liberal (conservative) federal government in 1996 as “a huge closeout of the environment movement” (P12), which, as noted earlier, had been increasingly brought into a close policy relationship with government during the 1983 to 1996 period of the Hawke/Keating Labour federal governments (Doyle Citation1990, Citation2000). Environmentalists within and allied to government agencies played a key role in devising the NRS during the early 1990s. The implementation of the NRS in 1997 under the Howard government, however, proved a decisive moment in the creation of the NGPA sector out of earlier environmentalist experiments (Davison et al. Citation2023). As key informant Barry Trail (former director of Pew Charitable Trusts and conservation scientist and advocate for more than twenty-five years) noted, the nascent organizations of the NGPA sector responded quickly to a new political reality, which required them to avoid being “overtly political,” as they sought to act as a bridge between private funders and a conservative government locked in adversarial dispute with environmentalists. As a board member of ALCA described, this took the form of ENGOs in the NGPA sector positioning their contribution as “apolitical, nonadvocacy, on-ground works, working with community” (P23). This positioning enabled ENGOs to maintain government legitimacy and access to policymakers, such as those associated with the NRS, while also promoting the tangible, practical results that can be achieved with private funding.

Led by disputes about climate change, public environmental debate in Australia continued to be characterized by partisan politics in the Citation2000s and 2010s (Tranter Citation2011; Colvin and Jotzo Citation2021). In this context, broad bipartisan support for NGPA objectives over this period has been remarkable. Bipartisanship has enabled a consistency of policy support, particularly across different political administrations, that is otherwise highly unusual in the volatile arena of environmental policy (Kirkpatrick et al. Citation2022). The ability to demonstrate support across the spectrum of electoral politics, however, serves arguably an even more important function for ENGOs; legitimacy in the eyes of a politically diverse network of potential donors, philanthropists, and investors. As a key informant involved with Bush Heritage told us, “We’re not going to be an activist organization as such. And that’s fairly important for most of our donor base” (P19). One consequence of this drive for political neutrality in Bush Heritage has been a need to create strategic distance from their environmentalist origins. Founded in 1990 by one of Australia’s most prominent wilderness activists and leader of the Australian Greens Party, Bob Brown, Bush Heritage has since become highly professionalized, seeking to reconfigure private protected areas as a mainstream and uncontentious activity (Damiens, Davison, and Cooke Citation2023). One participant closely involved with Bush Heritage explained that over the years, some big donors have withdrawn donations after learning that Bob Brown was the founder. This participant explained that, contrary to its early history of small environmentalist donors, “there is a tendency now toward big donors, from the corporate world, who don’t have any type of activist background, or history of supporting environmental campaigns” (P13).

Participants presented the ability of ENGOs to bring together people with different political objectives to participate in conservation as a matter of pride. As Jane Hutchinson, former executive director of strategy and innovation at the Nature Conservancy (and former CEO of the Tasmanian Land Conservancy) explains, ENGOs involved in the NGPA estate have been “very strategic” in not stoking “division.” This is evident in the way that ENGO discourse on protected areas has rarely challenged the suitability of basing conservation on settler-colonial private property rights on stolen First Nations lands, for example. Making property ownership a question of political interests, rather than an economic transaction, is antithetical to formative ENGO objectives. Indeed, the legitimacy of conservation on private land requires a depoliticization of property, which can foreclose wider questions of social and land justice (Gooden and Sas-Rolfes Citation2020). The strategic intent of ENGOs to appeal to wealthy cohorts not previously engaged in conservation is also evident in a deliberate shift in board membership to attract financial, corporate, and legal skill sets in place of passionate, grassroots environmentalists (Martin Citation2016). One NGPA leader put it bluntly: “board members should either have money, can get money or (should) get out” (P09).

ENGO efforts to “mainstream” conservation and grow a diverse donor base have seen these organizations disengage from arguments about the incompatibility of economic growth (and capitalist markets) and nature conservation. Key informant Bob Brown articulated the risks associated with disconnecting the NGPA sector from its political purpose:

We’re in the serious business of saving what we can of the planet from the fire of untrammelled human exploitation, … and the people who own the wealth are the prime drivers of that exploitation. … You have to be careful that the donors to an organization like Bush Heritage or the Nature Conservancy … are donating because of the principles of that organization, and not to change it and make it more comfortable. … [I]t seems to be that part of the thing if you’re going to be a private land conservator is that you don’t mix politics with it, because you’ll run into both donors and politicians, who want you to be quiet, but who want you to be an exemplar of what all environmentalists should be, a part of the market. … And sure, we’re trying to put some of the generated wealth from the exploitation of the planet back into protecting it, but there’s a fog there and it needs lifting.

Recent decades have seen ENGOs focused on marshaling the necessary resources for the maintenance and expansion of the NGPA estate through private funding. To grow the NGPA estate, ENGOs have adopted a non-partisan, apolitical position, rarely seeking to participate in environmental political debates about the causes as well as the solutions to environmental destruction. This aligns with the goal of ENGOs not to alienate either their base of supporters in progressive political parties, or their pool of wealthy donors (or potential donors) who do not wish to be associated with these parties or with political controversy. At the same time, the landholding and land managing interests of ENGOs in the NGPA sector has tightened their connection to private interests and market trends demonstrated through their adoption of accountability regimes. The adversarial politics that grew the power of ENGOs is now largely seen as antithetical to the maintenance and prosperity of the NGPA estate.

From Consensus to Compliance and Pragmatism?

The scale and influence of ENGOs involved in protected area conservation has grown rapidly in Australia, as part of a wider restructuring of environmental policy through the state–market nexus (Doyle Citation2000; Hawkins and Paxton Citation2019). ENGOs in the NGPA sector have participated in a neoliberal transformation of environmental governance through a trajectory that has taken them from civil society actor, to state delivery arm, to leader, agenda setter, and policymaker (Iannuzzi, Santos, and Mourato Citation2020). As we have seen, this trajectory has not been linear, with these roles often overlapping and being performed simultaneously.

The neoliberalization of protected area conservation has produced a dynamic, experimental, and transnational array of financial relationships, geared to attract as many different funding streams as possible. ENGOs in the NGPA sector pursue what they—and their funders—deem to be novel and pragmatic trajectories for conservation funding that assume limited direct government contribution. Philanthropic and for-profit finance has become a default and assumed beneficial practice in the sector, with questions of governance process and public interest framed in terms of an accountability to donors, partners, and investors. This, in turn, is disciplining protected area conservation to logics of philanthropic giving and for-profit investment (Beer Citation2023). ENGOs are actively shaping and leading this trajectory, in concert with their partners, although still reliant on the state for legitimacy and enabling policy. The operation of ENGOs in this capacity raises important questions about how they see themselves and their social responsibilities.

ENGOs have navigated an “in-between” role as they simultaneously navigate and dictate the “translation” (Trudeau and Veronis Citation2009) of neoliberalism into on-ground conservation outcomes. This has not only helped to reconfigure a protected area system, the majority of which is located on private and Indigenous lands and reliant on private investment, but reshaped the purpose and politics of ENGOs in the process. Examining the political and economic dynamics that constitute the NGPA estate has shown how diverse and competing interests and beneficiaries are often held together by ENGOs—sometimes precariously (Fletcher Citation2010). The manner in which the NGPA estate binds together market, civil society, and government actors reveals the prominent influence of private funders and market interests, who are actively shaping what activities are pursued, how conservation success is conceived, and how ENGOs participate in environmental politics.

The way in which the pursuit of funding through markets has become a discrete priority for ENGOs exemplifies the changing nature of their politics over time. This is evident in the way that questions of how and where funding is secured are largely quarantined from questions about the political, ecological, or governance consequences of aligning with capitalist modes of conservation. As a result, a “particular governmentality” (Fletcher and Büscher Citation2017, 230) for protected area governance has emerged, where partnering with private finance and philanthropic interests is positioned as pragmatic, and participation in activist environmental politics is positioned as an indulgence (Doyle Citation2000; Beer Citation2023). Here we see adherence to a hegemonic pragmatism aligned to the need to maintain existing obligations and operations amidst key service delivery roles in protected area conservation, rather than a pluralistic pragmatism that is open to dissent or debate (Brush 2020). This economic pragmatism and associated rhetoric of apolitical impartiality works to reinforce “the necessity, inevitability, and glittering rewards of for-profit conservation” (Dempsey and Suarez Citation2016, 667) and philanthropy. As a consequence, other political possibilities for the NGPA estate are narrowed or foreclosed, and the sector is able to offer little by way of an explanation for or engagement with the root causes of ecological destruction to which they are responding. Nor did most key informants appear to have an appetite for looking outside of existing policy agendas and apolitical consensus for alternative avenues to species conservation. Although many key informants were highly critical of governments, they did not canvas possibilities for the NGPA sector to directly contest policy settings, engage in public campaigns critical of government, or mobilize their member base through activist strategies.

Our key informants rarely discussed the risks of aligning conservation ambitions with the market logics that drive ecological destruction (Büscher and Fletcher Citation2020). A majority assumed that proactive conservation action in the form of an expanding protected area estate and science-led management were self-evidently good ends, regardless of the means used to achieve them. At a personal level, adhering to this instrumental positioning required the conscious projecting of an apolitical, professional status for individuals working in the NGPA sector, even though many did not personally align with this view. In practice, the apolitical status of ENGOs enabled a flexibility that allowed them to morph in different contexts and thereby span a diversity of otherwise contested political interests. An ENGO could simultaneously be delivering a conservation covenant (easement) scheme on behalf of the state, engaging in real estate markets in ways that create a price premium for covenanted properties through “revolving fund” (buy–protect–sell–repeat) mechanisms (Hardy et al. Citation2018), guiding property acquisition choices through an accountability regime dictated by a philanthropic donor, and making nature “investable” by reporting on charismatic species populations in protected properties. Connecting these efforts was a belief that ENGO leadership, capability, and expertise is necessary to deliver conservation outcomes that benefit society, as well as nature, as a whole.

The avowed apolitical mode of ENGO operation in the NGPA sector raises the question of whether advocacy for conservation from civil society actors has been diminished, further separating the sector from its origins. This decline of advocacy can reflect the self-disciplining efforts of ENGOs, as they seek to build partnerships with donors and governments, or the external discipline imposed by partners, or a combination of both. The internal discipline by which ENGOs govern themselves has grown in significance as the benefits of a bipartisan, apolitical approach have seen the sector mature, regardless of changes in government administration. ENGOs play an active role in producing neoliberal governance rationalities within but also beyond the NGPA estate through this legitimizing of nonconfrontational environmental action (Cohen and Rosenman Citation2020). In this way they contribute to wider “postpolitical” dynamics in environmental discourse that associate adversarial politics as “bad” or unconstructive for environmental agendas (Swyngedouw Citation2010), rather than see dissent or disagreement as a necessary component of democratic environmental politics (Brush 2020).

In examining the role of ENGOs in the NGPA estate, we are conscious of a simplistic tendency to position ENGOs as having “a ‘good’ past and … ‘ugly’ present” (Larsen Citation2016, 21). We also acknowledge that the more “radical” environmental political actors and movements often sit outside or at the fringes of ENGOs (Doyle, McEachern, and MacGregor Citation2015), or within smaller or less formal collectives (Mcdonald Citation2016). Yet, as we have seen, the more successful that the NGPA sector has been in leading protected area conservation (and in promoting their successes), the more entrenched neoliberal conservation has become in Australia’s political economy. Indeed, the ability of ENGOs to harness the land purchasing power of philanthropists amidst the prevalence of capitalist private-property ownership in Australia has exposed them to the excesses and risks of neoliberal experimentation, and the subsequent narrowing of environmental politics around attractive solutions rather than disturbing problems, in general, and around the interests of donors and investors, in particular.

The NGPA sector is a complex network of political interests and power relations that is far from singular or consistent. In particular, ENGOs in this sector have had some success recognizing First Nations’ cultural practices and custodial responsibilities to land. In part, due to the positive impetus from significant donors and through the efforts of specific individuals within organizations, ENGOs have made some partial effort to heed calls from First Nations, taking steps to broaden out “who counts” in terms of conservation constituencies. The efforts identified here are notable in light of patchy or absent efforts to decolonize conservation by the state or at international levels (IUCN Citation2000; Neale et al. Citation2019). Yet, as shown in the Tasmanian Midlands example, the neoliberal governance regimes within which ENGOs operate, articulated in this case through accountability frameworks, are likely to present ongoing obstacles to their ability to advocate for First Nations sovereignty. Moreover, it raises the wider question as to the durability of mutually beneficial alliances constructed within neoliberal governance, and whether such alliances might dissolve should prevailing political or economic conditions shift, or if the promise of “win–win outcomes” does not materialize (Dempsey and Suarez Citation2016).

Neoliberal dynamics of government retreat and governing at a distance have combined with market and civil society expansion into new areas of public good delivery. This has weakened the critical mission of NGPA conservation and diluted its formative politics, shaping the pursuit of consensus pragmatism into new forms of compliance and complicity. Framed as a success, the growing political and economic influence of the NGPA sector has reinforced these dynamics. In place of a radical vision, the bipartisan foundation of NGPA governance is a growing consensus around the efficacy and necessity of private finance, the “naturalizing” of neoliberal governance (Mouffe Citation2005; Woronov Citation2019), and strengthening acceptance of the “inevitability of capitalism and a market economy” (Swyngedouw Citation2010, 215) if we wish to care for endemic species and ecologies.

Conclusion

The reconfiguring of protected area conservation through the NGPA estate has required ENGOs to depoliticize their activities so as to cultivate bipartisan political support and prioritize the interests and influence of private donors and investors. ENGOs have established increasingly tight partnerships in which accountability to private financiers shapes the goals, form, and activities of the NGPA estate as part of a wider effort to address “failures associated with public conservation” (Beer Citation2023, 16). As nongovernment actors take more prominent roles in conservation policy and leadership, a consensus has crystallized around the necessity of aligning the NGPA estate with capital accumulation more broadly and experimental market mechanisms in particular. The extent of cooperative experimentation with for-profit and philanthropic financing explored here, and the implications they generate for protected area governance and conservation action, present important insights for understanding ENGO involvement in a global conservation context.

Without government intervention or activist interruption, we anticipate a further entwining of private, for-profit investment interests and conservation outcomes, and an expanding reliance on superrich philanthropists, to maintain the NGPA estate. We identify the dynamics of neoliberal governance as operating through the self-disciplining of ENGOs involved in protected area conservation, as well as through externally imposed discipline. The resulting NGPA estate has been shaped by a self-described ENGO rationality of pragmatism. This is an economic pragmatism driven by the need to maintain and diversify funding, which is used to justify adherence to market logics and sidestep ideological and structural debate on the basis that the goal of protecting nature trumps concerns about the means that might achieve it. Although increasingly presenting an apolitical front, ENGOs work implicitly to legitimate and reinforce dominant political and economic interests, in a marked departure from their more plural and activist political origins. ENGOs risk closing off the possibilities for alternative futures beyond capitalist conservation, at a moment when the trajectory of transformative possibilities for socioecological change must be dramatically widened.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the three reviewers who provided excellent insights and helped to improve this article. We are grateful to the key informants who gave generously of their time, insights, and good will, and to Lydia Schofield who conducted three interviews. Aidan Davison acknowledge the Muwinina and Palawa peoples of Lutruwita and Benjamin Cooke and Lilian M. Pearce acknowledge the people of the Woi Wurrung and Boon Wurrung language groups of the eastern Kulin Nation and the Taungurung people on whose unceded lands and waters we live and work.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Note

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Benjamin Cooke

BENJAMIN COOKE is a Senior Lecturer and Human Geographer at RMIT University, Melbourne VIC 3000, Australia. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests center on the social and political dimensions of nature conservation, including protected areas, governance, conservation practices, and urban greening.

Lilian M. Pearce

LILIAN M. PEARCE is a Lecturer in Environmental Humanities in the Centre for the Study of the Inland, Department of Archaeology and History at La Trobe University, Melbourne, VIC 3086, Australia. E-mail: [email protected]. She is also a Research Fellow in the School of Geography, Planning, and Spatial Sciences at the University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia. Her interdisciplinary research focuses on issues of social and environmental justice and how environmental management practices do political work.

Aidan Davison

AIDAN DAVISON is an Associate Professor in Human Geography and Environmental Studies at the University of Tasmania, Australia. E-mail: [email protected]. He is fascinated by contested concepts of nature, development, technology, and sustainability. His published work spans diverse topics including the urban forest, suburban history, environmentalism, climate change attitudes, the Anthropocene, and education for sustainability.

Notes

1 ESL was criticized for potentially conflicting with the best interests for conservation. In Citation2000 Earth Sanctuaries owned and managed eleven sanctuaries in three states, covering around 100,000 hectares of land (Productivity Commission Citation2001).

References

- Aldashev, G., and E. Vallino. 2019. The dilemma of NGOs and participatory conservation. World Development 123:104615. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104615.

- Apostolopoulou, E., A. Chatzimentor, S. Maestre-Andrés, M. Requena-I-Mora, A. Pizarro, and D. Bormpoudakis. 2021. Reviewing 15 years of research on neoliberal conservation: Towards a decolonial, interdisciplinary, intersectional and community-engaged research agenda. Geoforum 124:236–56. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.05.006.

- Archibald, C. L., M. D. Barnes, A. I. Tulloch, J. A. Fitzsimons, T. H. Morrison, M. Mills, and J. R. Rhodes. 2020. Differences among protected area governance types matter for conserving vegetation communities at-risk of loss and fragmentation. Biological Conservation 247:108533. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108533.

- Balboa, C. M. 2017. Mission interference: How competition confounds accountability for environmental nongovernmental organizations. Review of Policy Research 34 (1):110–31. doi: 10.1111/ropr.12215.

- Beer, C. M. 2023. Bankrolling biodiversity: The politics of philanthropic conservation finance in Chile. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 6 (2):1191–1213. doi: 10.1177/25148486221108171.

- Beeson, M., and A. Firth. 1998. Neoliberalism as a political rationality: Australian public policy since the 1980s. Journal of Sociology 34 (3):215–31. doi: 10.1177/144078339803400301.

- Betsill, M. M., A. Enrici, E. Le Cornu, and R. L. Gruby. 2022. Philanthropic foundations as agents of environmental governance: A research agenda. Environmental Politics 31 (4):684–705. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2021.1955494.

- Brenner, N., and N. Theodore. 2002. Cities and the geographies of “actually existing neoliberalism.” Antipode 34 (3):349–79. doi: 10.1002/9781444397499.ch1.

- Brockington, D., and R. Duffy. 2010. Capitalism and conservation: The production and reproduction of biodiversity conservation. Antipode 42 (3):469–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.2010.00760.x.

- Brockington, D., R. Duffy, and J. Igoe. 2008. Nature unbound: Conservation, capitalism and the future of protected areas. London: Earthscan.

- Büscher, B., and R. Fletcher. 2020. The conservation revolution: Radical ideas for saving nature beyond the Anthropocene. New York: Verso.

- Cohen, D., and E. Rosenman. 2020. From the school yard to the conservation area: Impact investment across the nature/social divide. Antipode 52 (5):1259–85. doi: 10.1111/anti.12628.

- Colvin, R. M., and F. Jotzo. 2021. Australian voters’ attitudes to climate action and their social-political determinants. PLoS ONE 16 (3):e0248268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248268.

- Commonwealth of Australia. 1997. Tasmanian regional forest agreement. Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Commonwealth of Australia. 2021. Collaborative Australian Protected Areas Database (CAPAD) 2020. Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Cooke, B., A. Davison, J. Kirkpatrick, and L. M. Pearce. 2022. Protecting 30% of Australia’s land and sea by 2030 sounds great—but it’s not what it seems. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/protecting-30-of-australias-land-and-sea-by-2030-sounds-great-but-its-not-what-it-seems-187435.

- Cooke, B., and R. Lane. 2018. Plant–human commoning: Navigating enclosure, neoliberal conservation, and plant mobility in exurban landscapes. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108 (6):1715–31. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2018.1453776.

- Cooke, B., and R. Lane. 2020. Making ecologies on private land: Conservation practice in rural-amenity landscapes. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave.

- Cope, M., and H. Kurtz. 2017. Organizing, coding and analyzing qualitative data. In Key methods in geography, ed. N. Clifford, M. Cope, T. Gillespie, and S. French, 642–59. London: Sage.

- Crowley, K. 2021. Effective environmental federalism? Australia’s Natural Heritage Trust. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 17 (1):1–382. doi: 10.1002/jepp.95.

- Damiens, F. L., A. Davison, and B. Cooke. 2023. Professionalisation and the spectacle of nature: Understanding changes in the visual imaginaries of private protected area organisations in Australia. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 6 (3):1825–53. doi: 10.1177/25148486221129418.

- Davison, A., L. M. Pearce, B. Cooke, and J. B. Kirkpatrick. 2023. From activism to “not-quite-government”: The role of government and non-government actors in the expansion of the Australian protected area estate since 1990. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 66 (8):1743–64. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2022.2040452.

- Dempsey, J., and P. Bigger. 2019. Intimate mediations of for-profit conservation finance: Waste, improvement, and accumulation. Antipode 51 (2):517–38.

- Dempsey, J., and D. C. Suarez. 2016. Arrested development? The promises and paradoxes of “selling nature to save it.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 106 (3):653–71. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2016.1140018.

- Doyle, T. 1990. Environmental movement power brokers. Philosophy and Social Action 16 (8):37–52.

- Doyle, T. 2000. Green power: The environment movement in Australia. Sydney, Australia: University of New South Wales Press.

- Doyle, T., D. McEachern, and S. MacGregor. 2015. Environment and politics. 4th ed. London and New York: Routledge.

- Drakopulos, L. 2022. Privatizing the fisheries observer industry: Neoliberal science and policy in the U.S. West Coast fisheries. Geoforum 131:116–25. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2022.03.004.

- Ebrahim, A. 2003. Accountability in practice: Mechanisms for NHOs. World Development 31 (5):813–29. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(03)00014-7.

- Fletcher, R. 2010. Neoliberal environmentality: Towards a poststructuralist political ecology of the conservation debate. Conservation and Society 8 (3):171. doi: 10.4103/0972-4923.73806.

- Fletcher, R., and B. Büscher. 2017. The PES conceit: Revisiting the relationship between payments for environmental services and neoliberal conservation. Ecological Economics 132:224–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.11.002.

- Fitzsimons, J. A. 2015. Private protected areas in Australia: Current status and future directions. Nature Conservation 10:1–23. doi: 10.3897/natureconservation.10.8739.

- Freeman, D., B. Williamson, and J. Weir. 2021. Cultural burning and public sector practice in the Australian capital territory. Australian Geographer 52 (2):111–29. doi: 10.1080/00049182.2021.1917133.

- Gooden, J., and M. Sas-Rolfes. 2020. A review of critical perspectives on private land conservation in academic literature. Ambio 49 (5):1019–34. doi: 10.1007/s13280-019-01258-y.

- Goodwin, I. 2022. Effectiveness of the biodiversity offsets scheme. Audit Office of New South Wales. Accessed May 4, 2022. https://www.audit.nsw.gov.au/our-work/reports/effectiveness-of-the-biodiversity-offsets-scheme

- Greaves, A. 2021. Protecting Victoria’s biodiversity. Victorian Auditor-General’s Office. Accessed May 4, 2022. https://www.audit.vic.gov.au/report/protecting-victorias-biodiversity?section=

- Hardy, M. J., J. A. Fitzsimons, S. A. Bekessy, and A. Gordon. 2018. Purchase, protect, resell, repeat: An effective process for conserving biodiversity on private land? Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 16 (6):336–44. doi: 10.1002/fee.1821.

- Harvey, D. 2007. Neoliberalism as creative destruction. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 610 (1):21–44. doi: 10.1177/0002716206296780.

- Hawkins, G., and G. Paxton. 2019. Infrastructures of conservation: Provoking new natures with predator fencing. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 2 (4):1009–28. doi: 10.1177/2514848619866078.

- Hay, I., and S. Muller. 2014. Questioning generosity in the golden age of philanthropy: Towards critical geographies of super-philanthropy. Progress in Human Geography 38 (5):635–53. doi: 10.1177/0309132513500893.

- Higgins, V., J. Dibden, and C. Cocklin. 2012. Market instruments and the neoliberalisation of land management in rural Australia. Geoforum 43 (3):377–86. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.10.002.

- Holmes, G. 2012. Biodiversity for billionaires: Capitalism, conservation and the role of philanthropy in saving/selling nature. Development and Change 43 (1):185–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7660.2011.01749.x.

- Holmes, G. 2015. Philanthrocapitalism, biodiversity conservation and development. In New philanthropy and social justice: Debating the conceptual and policy discourse. Contemporary issues in social policy: Challenges for change, ed. B. Morvaridi, 81–100. Chicago: Policy Press.

- Holmes, G., and C. J. Cavanagh. 2016. A review of the social impacts of neoliberal conservation: Formations, inequalities, contestations. Geoforum 75:199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.07.014.

- Iannuzzi, G., R. Santos, and J. M. Mourato. 2020. The involvement of non-state actors in the creation and management of protected areas: Insights from the Portuguese case. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 63 (9):1674–94. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2019.1685475.

- Igoe, J., and D. Brockington. 2007. Neoliberal conservation: A brief introduction. Conservation and Society 5 (4):432–49.

- International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). 2000. Financing protected areas: Guidelines for protected area managers. IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA) of IUCN, in collaboration with the Economics Unit of IUCN. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- Ivanova, I. M., and C. N. Cook. 2020. The role of privately protected areas in achieving biodiversity representation within a national protected area network. Conservation Science and Practice 2 (12):1–12. doi: 10.1111/csp2.307.

- Jepson, P. 2005. Governance and accountability of environmental NGOs. Environmental Science & Policy 8 (5):515–24. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2005.06.006.

- Kirkpatrick, J., J. Fielder, A. Davison, L. Pearce, and B. Cooke. 2022. The role of government in a partial transition from public to private in the expanding Australian Protected Area System. Conservation and Society 20 (3):201–10. doi: 10.4103/cs.cs_100_21.

- Larsen, P. B. 2016. The good, the ugly and the dirty Harry’s of conservation: Rethinking the anthropology of conservation NGOs. Conservation and Society 14 (1):21–33. doi: 10.4103/0972-4923.182800.

- Larsen, P. B., and D. Brockington, eds. 2018. The anthropology of conservation NGOs. London: Palgrave.

- Louder, E., and K. Bosak. 2023. Spectacle of nature 2.0: The (re)production of Patagonia National Park. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 113 (2):331–45. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2022.2106176.

- Mallin, M. F., D. C. Stolz, B. S. Thompson, and M. Barbesgaard. 2019. In oceans we trust: Conservation, philanthropy, and the political economy of the Phoenix Islands protected area. Marine Policy 107:103421. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.01.010.

- Martin, S. 2016. Bush heritage Australia: Restoring nature step by step. Sydney, Australia: NewSouth.

- Mcdonald, M. 2016. Bourdieu, environmental NGOs, and Australian climate politics. Environmental Politics 25 (6):1058–78.

- McEachern, D. 1993. Environmental policy in Australia 1981–91: A form of corporatism? Australian Journal of Public Administration 52 (2):173–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8500.1993.tb00267.x.

- Mitchell, B., S. Stolton, J. Bezaury-Creel, H. C. Bingham, T. L. Cumming, N. Dudley, J. A. Fitzsimons, D. Malleret-King, K. H. Redford, and P. Solano. 2018. Guidelines for privately protected areas: Best practice protected area guidelines. Series No. 29. Gland, Switzerland: International Union for the Conservation of Nature.