Abstract

In Baltimore, Maryland, more than 55,000 homes—roughly 30 percent of all residential plots—are subject to ground rent, a legacy of British feudal property law. Under this landlord–tenant system, the homeowner makes payments to the ground leaseholder, who maintains rights to the land. During the early 2000s, many Baltimoreans fell behind on their ground rent due to recessionary headwinds and were “ejected” from their homes as leaseholders took ownership (as collateral). Maryland lawmakers responded by passing housing protections in 2007, but several laws were overturned by the courts (Corma Citation2017). Using census and ground rent administrative data, we map the geography of ground rent in Baltimore. Our results reveal that originally a tool of class dispossession, ground rent became racialized in the 1950s and 1960s and today overwhelmingly affects Black communities and low-income households. Drawing on work by critical Marxist geographers, work on the production of decline, anti-Blackness, and property relations theory, we rely on a critical quantitative framework to illustrate how people, place, power structures, and relationality produce the pernicious and predatory “ground rent machine.” Telling the story of ground rent—a largely underexplored topic—illustrates how local racialized property regimes shape the geography of urban segregation and urban inequality.

In 2006, Deloris McNeil of Fayette Street in West Baltimore was notified by local authorities that she no longer owned her home. A place Ms. McNeil called home for twenty years, the house was repossessed by a local developer and then sold because she had fallen behind on her ground rent. Fred Schulte, a journalist for the Baltimore Sun, interviewed Ms. McNeil to understand how the property was sold without her knowledge:

The ground rent. I missed one year of not paying the ground rent. Because it’s not like I deliberately missed it, it’s that I got sick. But sometimes I feel like screaming at the top of my lungs. I’ve done that. I’ve done that. What I do now is the Bible and pray. (Schulte Citation2006)

Our use of the term ground rent should not be confused with ground rent as theorized by Marx or by neoclassical economists, both of which conceptualize ground rent as the generation of surplus through land ownership. Instead, our focus in this article examines the effects of ground rent as a feudal-colonial property relationship in Baltimore. We illustrate how this system maintains the property rights of the landlord while creating tenuous and precarious conditions for the homeowner. Our use of the term hereafter refers to this historical, legal phenomenon, imported into Maryland in the colonial era (Mayer and Johnson Citation1883).

In this article, we map the geography of ground rent and illustrate how ground rent is essential for understanding racialized property relations that undergird racial segregation, dispossession, and inequality in Baltimore. Using census data and ground rent data from the Maryland State Department of Assessments and Taxation (SDAT), we find that ground rent in Baltimore is uneven and unmistakably racialized, targeting Black homeowners. We estimate that until recently, at least $5.5 million per year in ground rent payments was extracted by landlords (or ground leaseholders) from people who own their own homes, but not the land, underscoring wealth dispossession that overwhelmingly affects Black households. Furthermore, the legal infrastructure surrounding ground rent in Maryland allowed landlords to assume ownership of homes and real property when households fell behind on their ground rent. Our analysis shows that roughly $25 million to $33 million in real estate exchanged hands, in a predatory way, between 2000 and 2006 due to ground rent ejectments.

The ground rent system in Baltimore embodies struggle over land, property making, and the (re)production of race through property. We tell the story of ground rent vis-à-vis two theoretical frameworks: (1) property relations theory, and (2) race and political economy of housing. Property relations theory examines how property privileges certain individuals at the expense and exclusion of others (Blomley Citation2004, Citation2016). The myriad of ways that property disadvantages certain populations and simultaneously (re)produces race is reflected in the uneven and racialized geography of ground rent. Therefore, it is necessary to center race empirically (Bhandar Citation2018; Ranganathan and Bonds Citation2022). We also draw from ongoing work by critical Marxist geographers, specifically the work on the production of decline and anti-Blackness, to illustrate how propertied residents and finance capital together create conditions allowing for the capture and extraction of profits from communities of color (e.g., Harvey and Chatterjee Citation1974; Zaimi Citation2022). This scholarship is essential for situating how people, place, power structures, and relationality work together to produce the pernicious and predatory “ground rent machine.”

We explore three key questions. First, what is the geography of ground rent in Baltimore City? Second, to what extent has ground rent become racialized over time? Third, how has ground rent shaped the urban geography of racial segregation and dispossession in Baltimore? After mapping the geography of ground rent, we address the second and third questions by exploring the intersection between ground rent and redlining (racist and classist practice that assigned grades to neighborhoods), as well as blockbusting (establishing Black neighborhoods by provoking White flight). These two practices were common forms of housing discrimination in Baltimore (Orser Citation1997). These three lines of inquiry help (1) demonstrate how ground rent has become increasingly racialized and, (2) frame how ground rent has shaped, and continues to shape, the geography of segregation and urban inequality in Baltimore.

Our results show that the geography of ground rent in Baltimore is uneven and unmistakably racialized, disproportionately affecting Black communities and low-income households. Originally a tool of class dispossession, ground rent became racialized in the 1950s and 1960s due, in part, to blockbusting. The way in which ground rent operates is also important. Ground rent operates as an opaque, convoluted, and highly localized legal-property mechanism that cumulatively drives segregation and racialized dispossession. This structure, which relies on a persistent state of decline through underinvestment, shows that interests of landowners are varied and sometimes competing, furthering our understanding of uneven development beyond the rent gap.

Theorizing fine-grained legal mechanisms and localized aspects of property relationships, as others have pointed out (Blomley Citation2005, Citation2020; Rolnik Citation2013; Bhandar Citation2018; Bonds Citation2019), are essential in contemporary urban geography. Redlining, racial covenants, exclusionary zoning, blockbusting, rent-gouging, and predatory mortgage lending are generally well-understood legal mechanisms that produce profit through racial division and subordination. Ground rent, however, remains largely underexplored. We suspect that the story of ground rent remains largely untold because of localized, complex legal frameworks that produce obfuscation through intentional and neoliberal opacity (Shelton Citation2023).

We use census and ground rent administrative data to empirically demonstrate how ground rent privileges certain individuals at the expense and exclusion of others. To fully account for data limitations and avoid the all-too-common atheoretical, empiricist, and positivist epistemological approaches of traditional quantitative geography, we rely on a critical quantitative geography framework. Critical quantitative geography embraces a relational and postpositivist theoretical approach, allowing us to use numbers to tell the stories of people and place in a reflexive way that scrutinizes power structures, problematizes data objectivity and neutrality, and accounts for the politics of categorization (e.g., Haraway Citation1988; Sayer Citation1992; Lawson Citation1995; Carter Citation2009). Framing the quantitative fingerprints of ground rent through broad urban theory demonstrates how data, when properly situated in theory, is a powerful tool for advancing progressive human geography (Sheppard Citation2001).

The article is structured as follows. First, we provide an overview of the brief history of ground rent and explain how the ground rent machine produces racialized land predation across the urban landscape. Second, we outline the methods for our analysis. Third, we explain how ground rent has shaped and continues to shape the urban geography of racial segregation and housing inequality in Baltimore in the results section.

Lords of Predatory Extraction

What is the history of ground rent? When did ground become racialized? How does ground rent produce harm? In this section, we (1) review property relations theory to understand how property privileges certain individuals while excluding others, (2) provide an exhaustive history on ground rent in Maryland, and (3) discuss predatory mechanisms of capital extraction in housing. This framework is essential for contextualizing how the structural mechanisms of ground rent, working in concert like elements of a machine, allow capitalists to extract profit through racialized land predation.

The Genealogy and Dispossession of Property

Centering property relations, and in particular, the struggles over property and land, is essential for understanding deepening income inequality, racial segregation, and racialized dispossession across U.S. cities. Geographers have only recently begun to fully contextualize the localized struggles over property and land. By thinking about land and property as pedagogy, property relations theory centers localized struggles over property and land as a set of relations for understanding how property privileges certain individuals at the expense and exclusion of others (see Blomley Citation2004, Citation2016). A foundational step to mapping property relations involves documenting the genealogy of property. This approach, outlined by Ranganathan and Bonds (Citation2022), reveals the “stories that are used to justify the emergence of private property as a self-evident institution, but that also reveal the violence and impunity through which property-making proceeds” (198).

Documenting the genealogy of property helps tell the story of who owns land, on what terms, who profits, and regulation of land by the state. This approach, referred to as the “urban land question,” explores how social and economic systems, as well as legal infrastructures of property relations, create unequal housing conditions (e.g., Rolnik Citation2013; Blomley Citation2016; Roy Citation2017; Bonds Citation2019). Individuals of color and the poor, in particular, have long been excluded and marginalized in the struggle over land. Critical property research, including Bhandar’s (Citation2018) research, documents this struggle and the importance of investigating “racial regimes of ownership” to reveal the constitutive nature of property and race (Ranganathan Citation2016; Bonds Citation2019). The urban land question asks how land becomes dispossessed from existing owners or inhabitants and enrolled in new or additional processes of capital accumulation. Critical property research has primarily leveraged qualitative research methods (some notable exceptions include Wyly et al. Citation2012; Immergluck Citation2018; Shelton Citation2018; Zaimi Citation2022; Seymour and Akers Citation2023). Despite being “public” data, one persistent issue is that property genealogy data are difficult to access and sometimes not in digital formats. For example, Zaimi (Citation2022) reviewed roughly 10,000 postwar property records in Chicago to understand the history of extraction across Chicago’s South Side. Incorporating local quantitative real estate data—which are opaque, convoluted, and often difficult to access—is essential to advancing critical property research.

The History of Ground Rent in Maryland

A 1981 pamphlet produced by the Maryland SDAT to explain ground rent to Marylanders cheerfully recounts the broad origins of Maryland’s system:

Leasing ground is an ancient practice traceable to the time of Moses. The concept endured until, by the time of the Middle Ages, a refined version had become woven into the feudal system in which the tenant owed the landlord … his allegiance and service along with the rent. (Lloyd Citation1981, 3)

Following U.S. independence, land leases in the form of ground rents were mostly abolished and property went through land reform to avoid foreign monarchs holding land and power. Legislative reforms, as well as court decisions, all but eliminated ground rent in Delaware, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania (Allinson and Penrose Citation1888; Chesnut Citation1942). Ground rent remains a fixture in two states, however: Maryland and Hawaii. The Hawaiian ground rent system is a remnant of the Hawaiian Kingdom and laws that were imported as its status as a British protectorate, indicating its shared history to feudal and colonial England. In Maryland, the Maryland General Assembly declared only quit-rents to foreign representatives illegal in 1780 rather than abolishing quit-rent payments altogether like other states (Mayer and Johnson Citation1883). This law handed Maryland landowners a major win: no quit-rent payment obligations to foreign monarchs, but the ability to collect ground rent income.

The British feudal quit-rent system of lord and tenant now formalized in Maryland state law recasts a homeowner with ground rent as a tenant with obligations to pay ground rent to the ground leaseholder in exchange for the right to build, occupy, and maintain a house. Ground rents in Maryland are never-ending, governed by a ninety-nine-year lease that is perpetually renewable (Chesnut Citation1942). The ground rent system requires homeowners make nominal semiannual payments to the ground leaseholder, generally ranging between $24 to $240 per year. As Corma (Citation2017) noted, “a homeowner subject to a Maryland ground rent is technically the owner of personal property but possesses the practical rights and duties of an owner of real property” (222). Until recently, this property regime allowed landowners to create new ground rents—becoming ground leaseholders—on properties they owned.

Under Maryland law, the ground leaseholder can file a lien or seize the home if the homeowner fails to pay ground rent on time (The People’s Law Library of Maryland Citation2022, Citation2023). This process is called ejectment. The leaseholder could, until recently, repossess the entire property from the homeowner (including the homeowner’s equity) even though ground rents in Baltimore are nominal (Schulte and Arney Citation2006b). Ejectment is an all-too-common story for many Baltimoreans each year, including Ms. Deloris McNeil of West Fayette Street in West Baltimore. After becoming sick and falling behind on her ground rent—likely a few hundred dollars—Ms. McNeil had her home repossessed by a local developer. Not having the heart to remove her own home, the developer rented the house to Ms. McNeil (Schulte and Arney Citation2006b). The predatory ground rent machine recast Ms. McNeil as a renter of her own home in a manner of months.

Many Baltimoreans like Ms. McNeil fell behind on their ground rent during the early 2000s, leading to an ejectment crisis. Between 2000 and 2005, almost 4,000 ejectment lawsuits were filed, with ground leaseholders seeking to take ownership (as collateral) by ejecting homeowners from their homes (Schulte and Arney Citation2006b). In an article detailing the factors contributing to the early 2000s ejectment crisis, Corma (Citation2017) noted:

[I]t is notable that the ground rents had never before been exploited in the way they were during the 2000s. It took something more to create the conditions leading to this crisis, which was ultimately brought on by the perfect mix of the following factors: the historical quirks of ground rent law, the modern-day consolidation of investment holdings, declining homeowner knowledge of their rights and remedies, and skyrocketing real estate values. The dysfunctional city bureaucracy, along with courts that were either overworked or indifferent (or both), provided the final pieces of the puzzle. (227)

Homeowners with ground rent also face other negative consequences. For instance, properties with ground rent are typically valued at about $10,000 less than comparable properties without ground rent (“Ground rent got you grounded or confused?” Citation2016). Thus, homeowners with ground rent are effectively penalized in the housing market, and they might have difficulty selling their property or securing a mortgage. Growing awareness of these negative consequences, combined with the ejectment crisis of the early 2000s, led to calls for reform of Maryland’s archaic ground rent laws.

In 2007, Governor Martin O’Malley presented an emergency bill to the Maryland Legislature aimed at protecting homeowners subject to ground rent by (1) creating a ground rent registry, (2) extinguishing any ground rents and transfer of land to ground rent tenants for any ground rent not entered in the ground rent registry by 30 September 2010, and (3) replacing the ejectment process with a “lien-and-foreclosure” process used in mortgage foreclosures (i.e., excess proceeds are returned to the homeowner after the debt is satisfied; Lee Citation2011; Corma Citation2017). The bill (i.e., Senate Bill 396/House Bill 463) was approved by the Maryland Legislature and signed into law by Governor O’Malley in May 2007.

Later that year, a consortium of ground rent owners filed two lawsuits challenging the legality of the ground rent protections (Arney Citation2007). The first case, filed by Charles Muskin in 2007 (Muskin v. State Department of Assessments and Taxation Citation2011), targeted the extinguishment provision, arguing that it “was an unconstitutional taking that infringed on the property rights of ground rent owners” (Corma Citation2017, 241). The Maryland Court of Appeals (now the Maryland Supreme Court) ruled in favor of Muskin in 2011, finding that the automatic extinguishment of ground rent for unregistered ground rents violated leaseholder property rights (The People’s Law Library of Maryland Citation2022). The Court’s decision was also consequential because it reestablished an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 unregistered ground rent leases that were previously extinguished under the 2007 legislation. The rebirth of these so-called zombie leases forced tenants to again pay ground rent to avoid ejectment (Siegel Citation2011). In the second case, filed by Stanley Goldberg (State of Maryland v. Stanley Goldberg, et al. Citation2014), the Court ruled in favor of the ground leaseholders, finding leaseholders “cannot be forced to file foreclosure actions in order to enforce their rights against the people living on the property” (The People’s Law Library of Maryland Citation2022).

The Maryland Legislature passed additional housing protections in 2012 and 2020, establishing important safeguards to protect individuals subject to ground rent.Footnote1 First, no new ground rent leases could be created after 22 January 2007 (Maryland Department of Assessments and Taxation Citation2021a). Second, ground rent leases must be registered with SDAT. Leaseholders with unregistered leases cannot (1) collect ground rent, (2) bring a civil action to enforce any rights under the ground rent lease, or (3) bring an action against the tenant. Third, tenants must receive at least sixty days’ notice of when the ground rent bill is due (Carwell Citation2020). Fourth, Maryland’s current legal framework allows homeowners to retain any equity they have in their home, rather than forfeiting it to the ground rent owner as was the case during the ejectment crisis (The People’s Law Library of Maryland Citation2022). Now, to enforce the collection of ground rent, the ground rent owner may initiate a legal proceeding and has the authority to sell the homeowner’s house, only after providing required notice and a court approves. Maryland’s SDAT announced two additional safeguards for ground rent tenants in 2022: (1) a streamlined process for redeeming ground rent, and (2) the Maryland Homeowner Assistance Fund, which provides financial support for individuals with delinquent ground rent (Maryland Department of Assessments and Taxation Citation2022b).

Predatory Extraction Through Segregation and Decline

In 1911, the Baltimore City Council passed the first racially restrictive exclusionary zoning ordinance in the United States, preventing members of a racial group from buying a house in a city block that was already majority owned by another race (Pietila Citation2010). The ordinance was a “quarantine, meant to keep black people in their place … and away from the rest of the city” (Lieb Citation2018, 210). After the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed exclusionary zoning in 1917 in Buchanan v. Warley, the state and private actors adopted other predatory housing strategies like redlining, blockbusting, rent gouging, land-installment contracts, unfair lending practices, unscrupulous real estate practices, racist covenants, predatory lending, contract-for-deed, and tax foreclosure. These discriminatory housing strategies primarily targeted low-income people of color and immigrants in depopulated and segregated neighborhoods, limiting economic and educational opportunity, especially for Black Americans (Chakraborty et al. Citation2011; Akers and Seymour Citation2018; Immergluck Citation2018; Shelton Citation2018; Seymour and Akers Citation2019; Taylor Citation2019; Zaimi Citation2022).

The city retained its strong segregation ethos even after the Fair Housing Act (FHA) was passed in 1968. The long history of segregation in Baltimore produced significant residential housing market differentiation, creating the conditions necessary for propertied residents and finance capital to capture and extract profits (Harvey and Chatterjee Citation1974). One significant way to capture and extract profits was to impose a “Black tax” by rent-gouging in redlined neighborhoods or charging high premiums to low- and middle-income Black buyers who could not otherwise secure a loan due to FHA discrimination (Harvey Citation1974, 246; Taylor Citation2019). In many cases, Black buyers would enter into land-installment contracts with White property owners who had speculatively purchased the property. The land-installment contract does not allow the purchaser to build equity in the property until the loan is paid off to the owner. If the purchaser was marginally late on a payment, the land-installment contract allows the owner to capture what the purchaser had paid, then recycle and resell the property to another low- or middle-income Black buyer with minimal investment (Harvey Citation1974). The hyperconcentration of Black Baltimoreans in West Baltimore is a result of these strategies (Harvey Citation1974, 196).

Our analysis focuses on two forms of housing discrimination that were common in Baltimore: redlining and blockbusting. The former, implemented in 1934 by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), “graded” neighborhoods according to housing quality, recent sales, and the race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status of neighborhoods (Nelson et al. Citation2022). This racist and classist practice made it difficult, if not impossible, for individuals in “D rated” or “redlined” neighborhoods to secure federally sanctioned mortgages to purchase a home. Blockbusting, common across many U.S. cities in the 1940s to 1960s, occurred when unscrupulous real estate actors established Black neighborhoods by provoking White flight. Although blockbusting provided a pathway to homeownership for some Black households, it was predatory, exposing Black families to social and economic trauma. In his book, Blockbusting in Baltimore: The Edmondson Village Story, Orser (Citation1997, 9) detailed the “exploitative prices” that Black families paid to access housing, the challenges to creating community in an urban neighborhood that experienced profound and seemingly instantaneous racial change, and the subsequent disinvestment in the neighborhood by commercial and municipal services.

These frameworks allow us to tell the story of ground rent responsibly. This means situating how people, place, power structures, and relationality are deeply imbued in the uneven and racialized structural processes of city making. The inseparable logic of anti-Blackness and capitalism has a profound impact on the segregation of cities, by casting Black neighborhoods as empty and threatening, which serves as a justification for their marginalization. Scholars have argued that this process seeks to transform legitimate Black spaces for capital expansion (Bledsoe and Wright Citation2019; Zaimi Citation2022; McKittrick Citation2013). In combining these frameworks, we run counter to narratives that reduce all city making to gentrification. Instead, the story of ground rent necessitates a state of decline, rejecting theories that “imply the wandering or withering of capitalist urbanization” and instead show the ways that ground rent “concretizes capital’s inclination to plunder and profit as a means of building cities” (Koscielniak Citation2019, 58).

Methodology

Critical Quantitative Geography

Quantitative data are a powerful tool for advancing racial and social justice in geography. Unfortunately, the all-too-common atheoretical, empiricist, and positivist epistemological approaches of quantitative geography (with genealogical roots in the quantitative revolution) have left the subfield “distant, unreflexive, ontologically, and epistemologically blind” (Carter Citation2009, 471), cementing its reputation as inadequate for advancing geographic thought and equity-focused public policy (Sheppard Citation2001). Achieving progressive human geography is possible, however, provided scholars adopt postpositivist geographical approaches to quantitative analysis (Sheppard Citation2001; Kwan and Schwanen Citation2009). In other words, quantitative scholars need to properly situate data and analysis in theory (Franklin Citation2023).

One approach for realizing progressive human geography is critical quantitative geography. The relational and postpositivist framework uses numbers to tell stories of people and place in a way that “scrutinizes the power structures that work to place and to keep in place raced and gendered bodies in certain social and physical spaces” (Carter Citation2009, 469). Feminist critiques of positivism and GIScience argue that quantitative data must be situated critically—in appropriate epistemological and methodological frameworks—to account for the politics of quantification (Lawson Citation1995; Schuurman Citation2006; Mahmoudi and Shelton Citation2022). Practically speaking, this means problematizing data objectivity and neutrality (e.g., Sayer Citation1992; D’Ignazio and Klein Citation2020), accounting for the politics of categorization (e.g., Williams Citation2008), and adopting an intentional reflexivity (Haraway Citation1988; Carter Citation2009). Telling the story of ground rent with census and administrative data, therefore, requires we follow two important tenets, in particular. First, counting is an overtly political process. Quantitative data are not neutral and therefore must be theoretically situated to interpret the overly gendered, racist, colonial, and heteronormative ways data are defined, collected, and reported. Second, quantitative data are not simply data points, but (partially) represent the life stories and struggles of everyday individuals. Framing the quantitative fingerprints of ground rent through these tenets—and theory more broadly—is essential for realizing a strategic postpositivism that illustrates how the ground rent machine structurally limits housing justice, making it difficult to realize a fully emancipatory Baltimore (Wyly Citation2011).

Data and Methods

To explore the geography of ground rent in Baltimore, we first mapped ground rent data using QGIS, an open source mapping and geovisualization software. Next, we examined the extent to which ground rent overlaps with redlining and blockbusting geographies across Baltimore. We delineated redlined areas using data from the Mapping Inequality project at the University of Richmond (Nelson et al. Citation2022), and identified blockbusted regions as areas that recorded high levels of White flight (i.e., 50 percent decline or more in the White population between 1950 and 1980; Sadler, Bilal, and Furr-Holden Citation2021). Together, this approach allows us to empirically assess the intersection of ground rent with two common forms of housing discrimination in Baltimore—redlining and blockbusting—while elevating the importance of ground rent in the urban geography of racial segregation and dispossession.

Ground rent data are maintained by the Maryland SDAT (Maryland Department of Assessments and Taxation Citation2021c). We requested property-level data for the state from SDAT for all properties that had ground rent with (1) a property identifier, (2) annual ground rent amount (in dollars), (3) ground rent leaseholder, and (4) ground rent redemption status. SDAT only provided only the property identifier for properties with ground rent (Maryland Department of Assessments and Taxation Citation2021b). The study area includes both Baltimore City and Baltimore County.

The lack of comprehensive data prevented us from conducting a more robust analysis. This situation underscores a larger issue, namely that data obfuscation perpetuates invisibility, making it difficult to fully unpack how ground rent produces harm through racialized land predation. Two additional examples illustrate obstacles we encountered in this study. First, SDAT maintains a Web-based search tool providing data indicating whether properties and parcels are subject to ground rent. Unfortunately, current SDAT regulations prevent users from scraping the site to conduct advanced-level research. Second, SDAT only releases ground rent data to state employees conducting research, preventing the public from submitting custom data requests. The digital curtain surrounding ground rent data is fundamentally different from most real estate data and other data of public record, which are accessible via Web-based multiple listing services.

Using ground rent data, we estimated the neighborhood ground rent density by dividing the number of residential land parcels containing ground rent by the total number of residential land parcels.Footnote2 Census tracts generally contain 4,000 to 6,000 residents and are a preferred census geography for neighborhood-level analysis (Spielman and Logan Citation2013). Therefore, the census tract serves as the unit of analysis in our study. To avoid ecological inference errors—an all-too-common source of bias where researchers make individual-level inferences from aggregate data—analysis and conclusions are relevant to, and must be interpreted at the neighborhood level (Robinson Citation2009).

We examined the racialized nature of ground rent by examining its relationship to the Black, African AmericanFootnote3 population between 1940–1970 and 2015–2019. Race data for the decades from 1940 to 1970 are from the decennial census, courtesy of IPUMS NHGIS at the University of Minnesota (Manson et al. Citation2022). The 2015 to 2019 data are from the American Community Survey (ACS), the largest nationwide annual survey for sociodemographic, economic, and housing conditions in communities across the United States (U.S. Census Bureau Citation2020). Unfortunately, these data sources introduce three limitations. First, individuals were unable to self-identify their race prior to the 1980 Census because racial identity was constructed and recorded by a census enumerator (Anderson Citation2015). Second, decennial census (and ACS) data contain coverage error. This error refers to the routine undercounts of populations of color and overcounts of non-Hispanic, White individuals. In the 2020 Census for example, 3.3 percent of Black, African American individuals were undercounted, meaning that roughly 1.5 million Black individuals were excluded from the census. At the same time, 1.6 percent of non-Hispanic, White individuals were overcounted, resulting in the double counting or erroneous inclusion of more than 3 million White individuals (U.S. Census Bureau Citation2022; Jurjevich [Citationunder review]). Third, ACS data are drawn from a statistical sample and therefore contain sampling error. The ACS data reported here are generally reliable because the sampling error is low relative to the tract-level estimates, so the accompanying statistical error is not reported (Jurjevich et al. Citation2018).

Next, we turned to univariate LISA spatial clustering analysis to assess the statistical significance of ground rent patterns in Baltimore. We conducted this analysis using GeoDa, an open source software for spatial data analysis (Anselin, Syabri, and Kho Citation2010). This geospatial technique accounts for the geographic interaction between and among geographic units, generating inferential statistics that quantify whether there is a statistically significant relationship (Anselin Citation1995). The analysis generates a Moran’s I statistic, which ranges from −1 to 1. Here, 0 represents perfect randomness, while −1 indicates perfect spatial heterogeneity (i.e., negative spatial autocorrelation where dissimilar values are next to each other) and 1 indicates spatial homogeneity (i.e., positive spatial autocorrelation where similar values, in this case ground rent, are spatially clustered).

LISA spatial clustering analysis also produces a map that indicates statistically significant interaction between and among geographic units. The two clusters of interest in our analysis, the high–high (HH) and low–low (LL) clusters, represent census tracts with unusually high and low incidences of ground rent, respectively. This analysis also helps identify additional independent variables important to understanding the geography of ground rent, and simultaneously control for racial hypersegregation.

Analysis

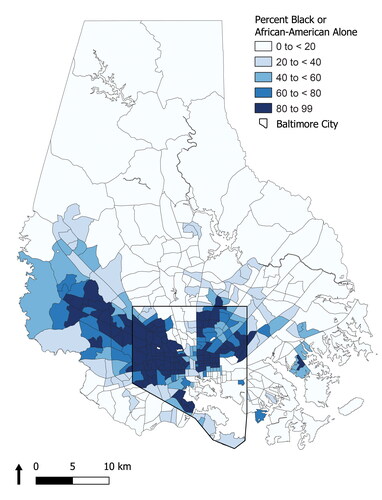

The Baltimore metropolitan area, like most conurbations, has racial segregation reflecting the enduring legacy of institutional housing discrimination and racist housing practices. Almost two-thirds (62.4 percent) of Baltimore City residents are Black or African American compared to 28.9 percent of Baltimore County, according to 2019 data (U.S. Census Bureau Citation2020). Most Black Baltimoreans live in West Baltimore and in Northeast Baltimore, where they comprise more than 90 percent of neighborhood populations (). White Baltimoreans, on the other hand, reside in a small section of Central Baltimore (e.g., Hampden) and in neighborhoods east of Downtown/Inner Harbor (e.g., Fells Point and Canton). In these areas, White, non-Hispanic individuals often make up more than 75 percent of the total population. The majority of Baltimore County is overwhelmingly White, except for a relatively narrow corridor in west central Baltimore County extending toward Lochearn and Randallstown ().

Figure 1. Percentage Black or African American (alone) population by census tract in the City of Baltimore and Baltimore County, 2015 through 2019. Source: Calculated by authors using data from U.S. Census Bureau (Citation2020).

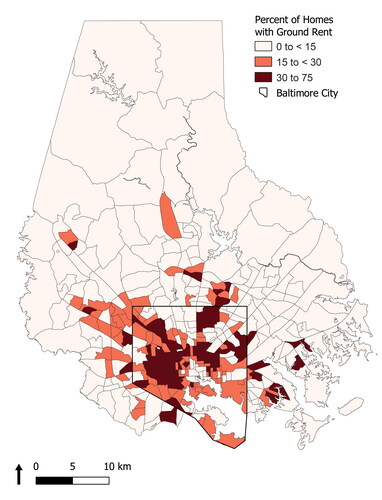

The racially segregated urban landscape in Baltimore is essential context for exploring our first research question: What is the geography of ground rent in Baltimore? Mapping ground rent reveals an uneven and unmistakably racialized geography. The present-day geography of ground rent in Baltimore, illustrated in , shows that ground rent is concentrated in majority-Black, African American neighborhoods, mirroring the racialized geography of the “Black Butterfly” shown in (Brown Citation2021). The highest concentrations of ground rent—where between 30 and 75 percent of residential parcels are subject to ground rent—are in West Baltimore, Northeast Baltimore, and a pocket in Northeast Central Baltimore (e.g., Chinquapin Park, Loch Raven, and Perring Loch neighborhoods near Morgan State University). The rate of ground rent in these neighborhoods is often more than double the citywide average. For example, in Census Tract 1604 in the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood, for example—home to Freddie Gray, Jr., who died in police custody in 2015—more than half (50.4 percent) of all residential properties contain ground rent. At the same time, ground rent is far less common in majority-White neighborhoods in the city. In Census Tract 2714 in the affluent and majority-White Roland Park neighborhood in North Central Baltimore, only 1.5 percent of all single-family residences contain ground rent. Real estate actors developed and built Roland Park and Sandtown-Winchester at nearly the same time in the city’s history (Maryland Department of Assessments and Taxation Citation2021b).

Figure 2. Percentage of residential parcels with ground rent by census tract in the City of Baltimore and Baltimore County, 2018. Source: Calculated by authors using Maryland Department of Assessments and Taxation (Citation2021c) data.

Ground rent is also more prevalent in the City of Baltimore compared to Baltimore County, further underscoring the racialized and uneven geography (). Of the roughly 192,000 single-family residences in the City of Baltimore, roughly 55,800 (29.1 percent) parcels had ground rent in 2018. Put another way, three in ten residential parcels in the City of Baltimore contain ground rent. In Baltimore County, however, just 10.2 percent of all residential parcels contained ground rent in 2018, roughly one-third of the rate in the City of Baltimore. Not all census tracts fit this pattern, however. Several census tracts in Essex, located in eastern Baltimore County, are majority-White and contain significant numbers of properties with ground rent. These areas include a handful of outlier tracts that do not represent broader trends.

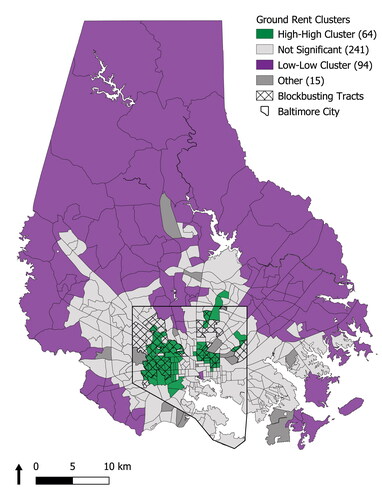

Spatial clustering analysis, illustrated in , provides further statistical evidence confirming the racialized geography of ground rent in Baltimore. The Moran’s I statistic, at 0.529, signals there is statistically significant spatial clustering of ground rent in the City of Baltimore not otherwise due to random chance. The LL cluster, which contains ninety-four census tracts, represents areas with low levels of ground rent surrounded by similar tracts. LL census tracts are almost exclusively located in Baltimore County, except for five LL census tracts in the City of Baltimore. These tracts are located in majority-White North Central Baltimore (e.g., Hampden and Roland Park neighborhoods), as well as a census tract adjacent to downtown, located in historic Little Italy and the rapidly developing Harbor East neighborhoods. The HH cluster contains sixty-four census tracts, located almost exclusively in the Black Butterfly of Baltimore.

Figure 3. Univariate local Moran’s I spatial clustering analysis by census tract in the City of Baltimore and Baltimore County (I = 0.529, p ≤ 0.05), 2018. Source: Calculated by authors using Maryland Department of Assessments and Taxation (Citation2021c) data.

These empirics illustrate that the geography of ground rent is uneven and unmistakably racialized, mirroring the racialized geography of the Black Butterfly. This is not by accident; it is structural. The genealogy of ground rent, like other forms of housing-property discrimination, reproduces racial division, subordination, and inequality. What remains unclear, however, is the extent to which ground rent has become racialized over time. When and why did ground rent become racialized? What is the recent history of ground rent in Baltimore?

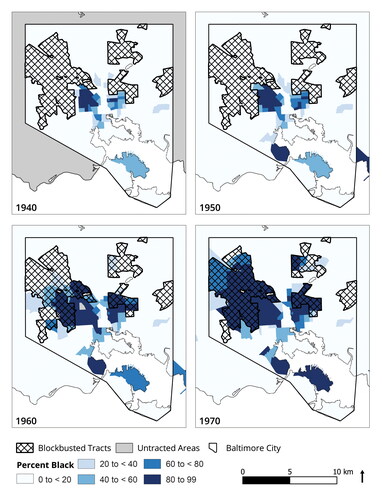

To address these questions, we first mapped the Black, African American population by Baltimore census tract from 1940 to 1970 ().Footnote4 As African Americans moved north in search of good-paying jobs, stable housing, and a more egalitarian social environment as part of the Great Migration, the Black, African American population in Baltimore grew considerably. In 1940, roughly one in five Baltimore residents were Black (166,000 or 19.3 percent) and by 1950, the Black population increased to 226,000 (23.8 percent; Manson et al. Citation2022). Comparing and reveals that ground rent was originally a tool of class dispossession in the mid-twentieth century, more likely burdening Baltimoreans of all racial backgrounds. In 1940, for example, both Black Baltimoreans living in redlined neighborhoods immediately west and east of Downtown/Inner Harbor and White Baltimoreans living on Baltimore’s middle-west side and in East Baltimore resided in neighborhoods with high levels of ground rent ( and ).

Figure 4. Percent Black or African American (alone) population overlay with blockbusted census tracts, City of Baltimore and Baltimore County, 1940 through 1970. Source: Calculated by authors using data from Manson et al. (Citation2022).

The racialization of ground rent began in the 1950s, when robust growth of Black Baltimore—100,000 residents or 44.2 percent growth—led real estate actors to blockbust four areas, the largest on Baltimore’s Westside and three areas in East Baltimore. Blockbusted census tracts are designated with a crosshatch pattern in and . Although widespread blockbusting began in Baltimore during the 1950s, it peaked during the 1960s. In 1950, for example, neighborhoods on Baltimore’s middle-west side (e.g., Mondawmin, Rosemont, Penn North, and Southwest Baltimore) and East Baltimore (e.g., Midtown, Greenmount, and Oldtown) were almost exclusively White. In just ten years, these neighborhoods became exclusively Black, driven by predatory blockbusting. More sweeping changes occurred during the 1960s. By 1970, Edmondson Village, Allendale, Walbrook, Dickeyville, and Beechfield, neighborhoods located on Baltimore’s far westside, became majority Black. Similar demographic changes occurred in the Midway/Coldstream neighborhood on Baltimore’s Eastside, as well as Northwood (represented as an island of blockbusting in North Central Baltimore).

The geographic breadth of blockbusting during the 1950s and 1960s in Baltimore is, without question, largely responsible for racializing ground rent in Baltimore City. Today, ground rent overwhelmingly affects Black communities and low-income households. Redlining, although important, is less directly responsible for the racialization of ground rent since 1950. Redlined areas were largely confined to adjacent areas surrounding Downtown, mirroring the donut area of lower ground rent rates in . This finding aligns with a recent study, which found that blockbusting, not redlining, was important for linking housing discrimination with poor food access in Baltimore (Sadler et al. Citation2021). Comparing the geography of ground rent with the spatial patterns of race, over time, reflects the early metamorphosis of what would become the Black Butterfly. The analysis also underscores how blockbusting racialized ground rent in a way that targets Black households in Black communities, perpetuating racial segregation, dispossession, and inequality.

Our third and final question examined how ground rent shaped the urban geography of inequality and dispossession in Baltimore. How do socioeconomic and housing disparities vary between places with and without ground rent? To understand the on-the-ground situation between places with low and high levels of ground rent in Baltimore, we examined population and socioeconomic statistics for ground rent clusters in the City of Baltimore and Baltimore County (). There are three important takeaways. First, the rate of residential ground rent in the HH cluster is more than double the rate for the entire study area (40.8 percent compared to 18.7 percent), and more than sixteen times the rate in the LL cluster (40.8 percent compared to 2.5 percent; ). These data expose, in no uncertain terms, the proclivity of property to perpetuate unequal opportunity.

Table 1. Selected population and socioeconomic descriptive statistics for spatial clusters in the City of Baltimore and Baltimore County, 2015 through 2019

Second, the racial disparity between the clusters is profound. The data illustrate that almost nine in ten individuals residing in the HH cluster are Black. Conversely, in the LL cluster, almost seven in ten individuals are White, non-Hispanic (). These profound disparities led us to explore the following question: How many individuals are affected by ground rent in Baltimore? Absent individual-level data, we estimate that as many as 63,800 Black Baltimoreans (61,900 and 1,900 in the HH and LL clusters, respectively) live in houses with ground rent alongside 13,100 White Baltimoreans (6,200 and 6,900 in the HH and LL clusters, respectively). Estimates for the HH cluster, for example, are derived first by accounting for the 40.8 percent of the 89,000 housing units that are subject to ground rent (). Next, considering the racial distribution (i.e., 87 percent Black, African American) and the actual persons per housing unit (i.e., 1.96), as many as 61,900 Black Baltimoreans were subject to ground rent in the HH cluster in 2018.

This approach, although helpful, likely underestimates the number of Black Baltimoreans experiencing ground rent. Vacancy rates are high in Baltimore. A decline in the vacancy rate closer to the regional average would boost the number of persons per housing unit, meaning that almost 17,100 more Black Baltimoreans could be subject to ground rent. Also, this approach assumes that the effects are uniformly distributed according to the racial distribution, and evidence from shows this is not the case in Baltimore. Finally, these estimates do not include ground rent in nonsignificant census tracts and do not account for census undercounts of hard-to-count populations.

The third and final important takeaway is that there is severe socioeconomic disparity between the clusters. This supports the idea that ground rent, like other predatory real estate schemes, primarily targets low-income people. The median household income in the HH cluster, $38,209, is slightly more than one-third the median household income of the LL cluster, at $101,394 (). With respect to housing tenure, 45 percent of households in the HH cluster are owner-occupied. This homeownership rate is slightly below the average for Baltimore (47.4 percent) and almost 20 percent below the U.S. average (64.1 percent) in 2019. Meanwhile, 72.1 percent of households in the LL cluster are owner-occupied—more than 27 percent above the homeownership rate in the HH cluster. Taken as a whole, these data do not support the argument that ground rent improves access to homeownership (Lloyd Citation1981). In fact, the data suggest the opposite.

The Ground Rent Machine

How, specifically, does ground rent produce harm? The growth machine refers to the coordination of urban actors to profit from growth through downtown redevelopments (Molotch Citation1976). The decline machine refers to the use of race-class narratives of decline to rationalize the same downtown redevelopments (Wilson and Heil Citation2022). What we term the ground rent machine refers to the predatory racialized extraction of wealth from urban neighborhoods outside the downtown area, using ground rent. In naming this phenomenon, we identify four structural mechanisms that work together like elements of a machine to extract profit through racialized land predation: (1) predatory ejectment, (2) an onerous and unclear process surrounding tenant rights and responsibilities, (3) state-sanctioned property law protecting leaseholders over tenants, and (4) data obfuscation perpetuating invisibility.

First, one of the most predatory aspects of ground rent is ejectment. Individuals who fall behind on their ground rent—like Deloris McNeil—are subject to ejectment, meaning that the ground leaseholder can pursue legal recourse to seize and sell the home. This legal arrangement, combined with the escalation of real estate values in Baltimore in the late 1990s and early 2000s, together incentivized the seizure of homes from struggling homeowners that fell behind on their ground rent. This approach, without question, weaponized ground rent as a tool of wealth extraction. Between 2000 and 2006, more than 500 tenants were ejected from their homes; the majority were located in the Black Butterfly of Baltimore (Schulte and Arney Citation2006a, Citation2006b). Each home in Baltimore had a fair market value of roughly $100,000 during this period, so assuming the homes in lower income neighborhoods (see ) were roughly half to two-thirds of the city’s overall value, we estimate that roughly $25 million to $33 million in real estate was extracted by landlords from people who own their own homes, but not the land, during this period (Fellenz Citation2006). This example (1) illustrates how Black wealth dispossession is a constitutive element of the ground rent machine, and (2) expands our understanding of forms of uneven development beyond the rent gap.

Second, ground rent has long been an insider’s game. The system relies on an onerous and unclear framework that makes it difficult, if not impossible, for many homeowners to realize their rights and responsibilities. “Redeeming” ground rent, for example, remains a complicated and expensive process.Footnote5 Here, homeowners can buy out of future annual ground rent payments by making a lump sum payment to the leaseholder, provided three to five years have commenced on the lease period. The payment amount is calculated by dividing the annual ground rent amount by a percentage, which ranges between 4 percent and 12 percent (depending on when the lease was created), plus three years of the annual ground rent. Redeeming ground rent on a lease established in 1956, for example, at $120 per year would cost the homeowner $2,360 (i.e., [$120/6 percent] + [$120*3]; Maryland Department of Assessments and Taxation Citation2022a), excluding professional and processing fees. A major caveat to redeeming ground rent is this: Redeeming ground rent is not purchasing the land, so the buyout only lasts until property ownership changes, as in cases of property sales or inheritance (Lloyd Citation1981; Corma Citation2017). For example, if the Daniels family redeemed their ground rent in 1998 and sold their home in 2017, the leaseholder could again collect ground rent from the new homeowner.

We estimate that at least $5.5 million per year in ground rent payments is extracted by landlords (or ground leaseholders) from people who own their own homes in Baltimore, but not the land (i.e., assuming an average annual ground rent payment of $100 across 55,000 residential parcels). This wealth dispossession overwhelmingly affects Black households. It is often difficult to ascertain the individuals who own ground rent because many leaseholders rely on limited liability partnerships and other legal frameworks to protect their identity. During the early 2000s, more than half of ground leaseholders in Baltimore City were associated with four groups of individuals and families (Schulte and Arney Citation2006b). Leaseholders acquire ground rents via inheritance or through buying and selling ground rents in the real estate market (Corma Citation2017).

Third, state-sanctioned property law is structured to protect ground leaseholders over tenants. Although recent housing protections passed by the Maryland Legislature establish additional safeguards to protect individuals subject to ground rent, the scales of justice clearly favor leaseholders. Having the rights and duties of owning real property, for example, means that the tenant must pay property taxes on land that is owned by the leaseholder (Moran v. Hammersla Citation1947; McRae Citation2023). To illustrate this point more clearly, consider the situation for the Williamsons (pseudonym), residents of Edmondson Village on Baltimore’s Westside. Tax records indicate that the Williamsons owed roughly $2,900 in property taxes in 2023–2024 based on a $121,200 tax assessment that includes $30,000 worth of land owned by the ground leaseholder (Maryland Department of Assessments and Taxation Citation2021c; City of Baltimore Citation2024).

Fourth, data obfuscation perpetuates a digital invisibility, making it difficult to fully unpack how ground rent produces harm through racialized land predation. For example, despite asking for detailed property-level data (e.g., a property identifier, annual ground rent amount, ground rent owner, and ground rent redemption status), SDAT only provided only the property identifier for properties with ground rent. We implore Maryland officials to address the digital curtain of ground rent data by making detailed data more accessible to citizens, community-focused organizations, and researchers to support more protections for homeowners.

Conclusion

In Baltimore, more than 55,000 homes—roughly 30 percent of all residential plots—are subject to ground rent. This archaic feudal-colonial property relationship recasts the homeowner as a tenant who must make payments to the ground leaseholder who owns the land. In this article, we tell the story of ground rent by investigating three key questions. First, what is the geography of ground rent in Baltimore? Second, to what extent has ground rent become racialized over time? Third, how has ground rent shaped the urban geography of racial segregation and dispossession in Baltimore?

The geography of ground rent in Baltimore City is uneven and unmistakably racialized. Mapping the geography of ground rent illustrates that low-income residents and Black Baltimoreans are far more likely to live in houses with ground rent ( and ). In the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood on Baltimore’s near Westside, for example, more than half (50.4 percent) of all residential properties contain ground rent. At the same time, ground rent is far less common in the affluent and majority-White Roland Park neighborhood in North Central Baltimore, where only 1.5 percent of all single-family residences contain ground rent. Further empirical analysis (i.e., univariate LISA spatial clustering analysis) reveals statistically significant spatial clustering of ground rent, meaning that spatial patterns in Baltimore are not otherwise due to random chance (). In other words, the uneven and racialized geography of ground rent is not accidental; it is structural.

Although ground rent was originally a tool of class dispossession, it became racialized in the mid-twentieth century. In 1940, Black and White Baltimoreans were equally likely to live in neighborhoods with high levels of ground rent ( and ). Ground rent became racialized in the 1950s, however, when real estate actors blockbusted four areas, the largest on Baltimore’s Westside and three areas in East Baltimore (). This history reflects the early metamorphosis of what would become the Baltimore Black Butterfly (Brown Citation2021) and simultaneously underscores the connection between ground rent and present-day racial segregation in Baltimore. Ground rent also perpetuates racialized wealth dispossession in Baltimore. We estimate that (1) at least $5.5 million per year in ground rent payments is extracted by landlords (or ground leaseholders) from people who own their own homes, but not the land; and (2) roughly $25 million to $33 million in real estate exchanged hands, in a predatory way, between 2000 and 2006 due to ground rent ejectments.

Our research contributes to the broader geographic literature by illustrating how this racialized property regime is inextricably linked to the urban geography of Baltimore. Telling the story of ground rent allows us to frame the quantitative fingerprints of ground rent in geographic theory in four ways. First, our analysis shows that ground rent, like other property relationships, privileges certain individuals at the expense and exclusion of others, shaping the geography of segregation and urban inequality in Baltimore. The data are clear, helping us reject the argument that ground rent supports higher rates of homeownership for Black Baltimoreans (Lloyd Citation1981). Second, tracing the genealogy of ground rent vis-à-vis “racial regimes of ownership” shows how people, place, power structures, and relationality—reflected in the mechanisms of the ground rent machine—work together to create an urban landscape where Black Baltimoreans are marginalized and excluded from their own city (Blomley Citation2004, Citation2016; Rolnik Citation2013; Ranganathan Citation2016; Roy Citation2017; Bonds Citation2019). Third, we contribute a clear and localized example of racialized housing dispossession that relationally produces poverty and wealth in uneven geographies. The production of decline in Baltimore’s Black neighborhoods serves to produce wealth, or transfer capital, to White(r) parts of Baltimore and Baltimore County.

Fourth, our work adds to the diverse forms of uneven development beyond dominant rent-gap explanations. Rather than profit through rising property values as is the case in traditional rent-gap forms of uneven development, ground leaseholders profited from individual properties through a perpetual cycle of sale and dispossession through ejectment—retaking ownership to start the cycle over again. This structure, which relies on a persistent state of decline through underinvestment, shows that interests of real estate actors are varied and sometimes competing. In doing so, we contribute to an emerging literature on urbanization based on profit extraction that necessitates and reinforces a neighborhood’s state of decline (Koscielniak Citation2019; Zaimi Citation2022; Seymour and Akers Citation2023). For example, although over half of Baltimore’s ground rents are located in clusters of tracts that are perceived to be devalued, marked by poverty and inequality (), these neighborhoods are not awaiting investment—they are not “unproductive” in terms of capital. Instead, the actions by ground rent owners during the ejectment crisis, for example, revealed the “productivity” of the extraction of profits through the recycling of housing via ground rent, a process of urbanization as decline (Hackworth Citation2019).

Telling the story of ground rent in a critical quantitative geography framework illustrates how data can be used to fight for emancipatory futures. Census and administrative data, situated in a relational and postpositivist approach, can empower individuals and community groups fighting for laws that address this sinister form of profit-making (Carter Citation2009; Wyly Citation2011). These lessons underscore the power of critical quantitative geographic research for advancing progressive human geography (Sheppard Citation2001). We see this as a fruitful avenue for future research and action. Building on the work of the Baltimore Sun, future research should advance the story of ground rent with oral histories of ground rent dispossession. The recent escalation of property values also raises interesting questions surrounding ground rent in Maryland. With the Maryland legislature replacing the ejectment process with a “lien-and-foreclosure” process used in mortgage foreclosures in 2007, what is the geography and prevalence of ejectments? Is the value of ground rent more closely tied to rent payments? Have there been significant changes in ground rent ownership? This work is essential for understanding deepening income inequality, racial segregation, and racialized dispossession across U.S. cities.

Quantitative data are not simply data points but are abstractions and representations of the life stories and struggles of everyday individuals. This principle is important for thinking about the politics of data obfuscation. Why are ground rent data so different from other real estate data and other data of public record, which are accessible and scrapeable via Web-based multiple listing services? Making detailed parcel level data (e.g., creation date of the ground rent, amount of the ground rent, redemptions of ground rent, longitudinal data on ejectments, and the address of the ground leaseholder) accessible to all researchers and community groups is necessary for dismantling digital invisibility and realizing data and racial justice more broadly.

In 2020, the Maryland legislature recently passed limited housing protections for ground rent tenants. This is a welcome step in the right direction. We call for a more robust set of protections in the future that secure the rights of Baltimore homeowners, like Ms. McNeil, leading to more equitable housing outcomes and racial justice.

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this paper to Ms. Deloris McNeil, Ms. Cynthia Walker, Mr. Ernest J. Walker, Jr., and all the Black and low-income Baltimoreans subjected to the archaic system of ground rent. We thank Katie Meehan, Lise Nelson, Jamaal Green, and several anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback on an earlier version of this work, as well as the People’s Law Library of Maryland at Maryland’s Thurgood Marshall State Law Library. The authors contributed equally to this work.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jason R. Jurjevich

JASON R. JURJEVICH is an Assistant Professor in the School of Geography, Development, & Environment at the University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests include critical quantitative methods, census, migration and demographic change, and housing.

Dillon Mahmoudi

DILLON MAHMOUDI is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Geography & Environmental Systems at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, Baltimore, MD 21250. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests include critical GIS and countermapping, urban and economic geography, labor markets, digital geography, and political ecology.

Notes

1 The Maryland Legislature passed Senate Bill 135/House Bill 177 in 2012 (https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/2012rs/billfile/hb0177.htm) and four bills in 2020: (1) Senate Bill 170/House Bill 241 (https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/mgawebsite/Legislation/Details/SB0170?ys=2020RS), (2) Senate Bill 806/House Bill 1182 (https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/mgawebsite/Legislation/Details/SB0806?ys=2020RS), (3) House Bill 172 (https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/mgawebsite/Legislation/Details/HB0172?ys=2020RS), and (4) House Bill 149 (https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/mgawebsite/Legislation/Details/HB0149?ys=2020RS).

2 Our analysis includes land parcels coded as residential for primary use according to the Maryland SDAT land use code.

3 The 2015–2019 ACS data includes individuals identifying as non-Hispanic. Black, African American (alone). Individuals could only identify as one race prior to the 2020 Census, so race data for 1940 through 1970 are, by default, race alone.

4 Longitudinal ground rent data are ideal for examining ground rent geographies over time, but these data are not available from SDAT.

5 Prior to the passage of the 2022 legislation that streamlined ground rent redemptions, the process was so complicated that SDAT recommended homeowners consult an attorney or title company to assist with the redemption process. (see https://web.archive.org/web/20211218092529/https://dat.maryland.gov/realproperty/Pages/Ground-Rent.aspx).

References

- Akers, J., and E. Seymour. 2018. Instrumental exploitation: Predatory property relations at City’s end. Geoforum 91 (May):127–40. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.02.022.

- Allinson, E. P., and B. Penrose. 1888. Ground rents in Philadelphia. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 2 (3):297–313. doi: 10.2307/1879416.

- Anderson, M. J. 2015. The American census: A social history. 2nd ed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Anselin, L. 1995. Local indicators of spatial associationLISA. Geographical Analysis 27 (2):93–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-4632.1995.tb00338.x.

- Anselin, L., I. Syabri, and Y. Kho. 2010. GeoDa: An introduction to spatial data analysis. In Handbook of applied spatial analysis: Software tools, methods and applications, ed. M. Fischer and A. Getis, ed. M. M. Fischer and A. Getis, 73–89. Berlin: Springer.

- Arney, J. 2007. Ground rent owners sue for compensation. The Baltimore Sun, November 2. Accessed June 12, 2022. https://www.baltimoresun.com/business/bal-te.bz.groundrent02nov02-story.html.

- Bhandar, B. 2018. Colonial lives of property: Law, land, and racial regimes of ownership. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Bledsoe, A., and W. J. Wright. 2019. The anti-Blackness of global capital. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 37 (1):8–26. doi: 10.1177/0263775818805102.

- Blomley, N. 2004. Unsettling the city: Urban land and the politics of property. London and New York: Routledge.

- Blomley, N. 2005. Remember property? Progress in Human Geography 29 (2):125–27. doi: 10.1191/0309132505ph535xx.

- Blomley, N. 2016. The territory of property. Progress in Human Geography 40 (5):593–609. doi: 10.1177/0309132515596380.

- Blomley, N. 2020. Precarious territory: Property law, housing, and the socio-spatial order. Antipode 52 (1):36–57. doi: 10.1111/anti.12578.

- Bond, B. W. 1919. The quit-rent system in the American colonies. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Bonds, A. 2019. Race and ethnicity I: Property, race, and the carceral state. Progress in Human Geography 43 (3):574–83. doi: 10.1177/0309132517751297.

- Brown, L. T. 2021. The Black butterfly: The harmful politics of race and space in America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Carter, P. L. 2009. Geography, race, and quantification. The Professional Geographer 61 (4):465–80. doi: 10.1080/00330120903143466.

- Carwell, L. M. 2020. Ground rent: Process and issues. Maryland Volunteer Lawyer Service, April 15. https://mvlslaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/GROUND-RENT-3-1.pdf.

- Chakraborty, A., N. Kaza, G.-J. Knaap, and B. Deal. 2011. Robust plans and contingent plans. Journal of the American Planning Association 77 (3):251–66. doi: 10.1080/01944363.2011.582394.

- Chesnut, W. C. 1942. The effect of quia emptores on Pennsylvania and Maryland ground rents. University of Pennsylvania Law Review and American Law Register 91 (2):137–52. doi: 10.2307/3309212.

- City of Baltimore. 2024. City of Baltimore real property tax search. Accessed March 28, 2024. https://pay.baltimorecity.gov/realproperty/.

- Corma, E. A. 2017. Business is business: Ground rents and ejectments in Baltimore. Rutgers University Law Review 70 (1):221–56.

- D’Ignazio, C., and L. F. Klein. 2020. Data feminism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/11805.001.0001.

- Fellenz, C. 2006. Taken to court over unpaid ground rent. The Baltimore Sun, December 10. http://photos1.blogger.com/x/blogger/789/3608/1600/398139/26823588.gif.

- Franklin, R. 2023. Quantitative methods II: Big theory. Progress in Human Geography 47 (1):178–86. doi: 10.1177/03091325221137334.

- Ground rent got you grounded or confused? 2016. The Frederick News-Post, March 11. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://www.fredericknewspost.com/archive/ground-rent-got-you-grounded-or-confused/article_85193e62-a36b-5b9e-9d96-f80abf7deb38.html.

- Hackworth, J. 2019. Manufacturing decline: How racism and the conservative movement crush the American Rust Belt. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Haraway, D. 1988. Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of the partial perspective. Feminist Studies 14 (3):575–89. doi: 10.2307/3178066.

- Harvey, D. 1974. Class-monopoly rent, finance capital and the urban revolution. Regional Studies 8 (3–4):239–55. doi: 10.1080/09595237400185251.

- Harvey, D., and L. Chatterjee. 1974. Absolute rent and the structuring of space by governmental and financial institutions. Antipode 6 (1):22–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.1974.tb00580.x.

- Immergluck, D. 2018. Old wine in private equity bottles? The resurgence of contract-for-deed home sales in US urban neighborhoods. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 42 (4):651–65. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12605.

- Jurjevich, J. R. Under review. Census undercounts, digital displacement, and data justice: What geographers need to know about the 2020 Census. The Professional Geographer.

- Jurjevich, J. R., A. L. Griffin, S. E. Spielman, D. C. Folch, M. Merrick, and N. N. Nagle. 2018. Navigating statistical uncertainty: How urban and regional planners understand and work with American Community Survey (ACS) data for guiding policy. Journal of the American Planning Association 84 (2):112–26. doi: 10.1080/01944363.2018.1440182.

- Koscielniak, M. R.-J. 2019. How to placemake a killing: Critical encounters with decline-as-urbanization. In New geographies 10: Fallow, vol. 5, ed. J. Smachylo and M. Chieffalo, 58–67. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Graduate School of Design and Actar.

- Kwan, M.-P., and T. Schwanen. 2009. Quantitative revolution 2: The critical (re)turn. The Professional Geographer 61 (3):283–91. doi: 10.1080/00330120902931903.

- Lawson, V. 1995. The politics of difference: Examining the quantitative/qualitative dualism in post-structuralist feminist research. The Professional Geographer 47 (4):449–57. doi: 10.1111/j.0033-0124.1995.449_l.x.

- Lee, E. 2011. Maryland ground rent lease safeguards begin to come undone. Accessed March 24, 2021. https://www.wtplaw.com/news-events/maryland-ground-rent-lease-safeguards-begin-to-come-undone.

- Lieb, E. 2018. “Baltimore does not condone profiteering in squalor”: The Baltimore plan and the problem of housing-code enforcement in an American city. Planning Perspectives 33 (1):75–95. doi: 10.1080/02665433.2017.1325774.

- Lloyd, H. C. 1981. A short short story on ground rents. Baltimore: Maryland State Department of Assessments and Taxation.

- Mahmoudi, D., and T. Shelton. 2022. Doing critical GIS. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 21 (4):327–36.

- Manson, S., J. Schroeder, D. Van Riper, T. Kugler, and S. Ruggles. 2022. Data from National historical geographic information system: Version 17.0 (data set). Accessed June 12, 2022. doi: 10.18128/D050.V17.0.

- Maryland Department of Assessments and Taxation. 2021a. Ground rent registration form. Accessed July 7, 2021. https://dat.maryland.gov/SDAT%20Forms/groundrent_registry.pdf.

- Maryland Department of Assessments and Taxation. 2021b. Home page. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://dat.maryland.gov/.

- Maryland Department of Assessments and Taxation. 2021c. SDAT: Real property data search. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://sdat.dat.maryland.gov/RealProperty/Pages/default.aspx.

- Maryland Department of Assessments and Taxation. 2022a. Ground rent redemption forms. Accessed November 30, 2022. https://dat.maryland.gov/realproperty/Pages/Ground-Rent.aspx.

- Maryland Department of Assessments and Taxation. 2022b. SDAT announces improvements to ground rent system. Accessed September 30, 2022. https://dat.maryland.gov/newsroom/Pages/2022-03-10-GroundRentRelease.aspx.

- Mayer, L., and J. Johnson. 1883. Ground rents in Maryland, with an introduction concerning the tenure of land under the proprietary. Baltimore, MD: Cushings & Bailey.

- McKittrick, K. 2013. Plantation futures. Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 17 (3):1–15. doi: 10.1215/07990537-2378892.

- McRae, D. 2023. What’s been happening on the ground (rent) in Maryland. Accessed March 28, 2024. https://www.rkwlawgroup.com/posts/whats-been-happening-on-the-ground-rent-in-maryland.

- Molotch, H. 1976. The city as a growth machine: Toward a political economy of place. American Journal of Sociology 82 (2):309–32. doi: 10.1086/226311.

- Moran v. Hammersla, 52 A.2d 727 (Md. 1947).

- Muskin v. State Department of Assessments and Taxation, 422 Md. 544, 30 A.3d 962 (2011).

- Nelson, R. K., L. Winling, R. Marciano, and N. Connolly. 2022. Mapping inequality: Redlining in New Deal America. In American panorama: An atlas of United States history, ed. R. K. Nelson and E. L. Ayers, 1–14.https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/.

- Orser, W. E. 1997. Blockbusting in Baltimore: The Edmondson Village story. Reprint ed. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

- The People’s Law Library of Maryland. 2022. Understanding ground rent in Maryland. The People’s Law Library of Maryland. Accessed March 28, 2024. https://web.archive.org/web/20221207071934/https://www.peoples-law.org/understanding-ground-rent-maryland.

- The People’s Law Library of Maryland. 2023. Understanding ground rent in Maryland. Accessed March 28, 2024. https://www.peoples-law.org/understanding-ground-rent-maryland.

- Pietila, A. 2010. Not in my neighborhood: How bigotry shaped a great American City. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee.

- Ranganathan, M. 2016. Thinking with flint: Racial liberalism and the roots of an American water tragedy. Capitalism Nature Socialism 27 (3):17–33. doi: 10.1080/10455752.2016.1206583.

- Ranganathan, M., and A. Bonds. 2022. Racial regimes of property: Introduction to the special issue. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 40 (2):197–207. doi: 10.1177/02637758221084101.

- Robinson, W. S. 2009. Ecological correlations and the behavior of individuals. International Journal of Epidemiology 38 (2):337–41. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn357.

- Rolnik, R. 2013. Late neoliberalism: The financialization of homeownership and housing rights. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37 (3):1058–66. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12062.

- Roy, A. 2017. Dis/possessive collectivism: Property and personhood at city’s end. Geoforum 80:A1–A11. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.12.012.

- Sadler, R. C., U. Bilal, and C. D. Furr-Holden. 2021. Linking historical discriminatory housing patterns to the contemporary food environment in Baltimore. Spatial and Spatio-Temporal Epidemiology 36 (100):100387. doi: 10.1016/j.sste.2020.100387.

- Sayer, R. A. 1992. Method in social science: A realist approach. 2nd ed. London and New York: Routledge.

- Schulte, F., Dir. 2006. Ground rent ejectment – Whose house is it anyway? The Baltimore Sun. Accessed January 3, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o6xASdxrhTY.

- Schulte, F., and J. Arney. 2006a. The new lords of the land. The Baltimore Sun, December 11. Accessed February 9, 2020. https://www.baltimoresun.com/business/real-estate/bal-groundrent2-121106-story.html.

- Schulte, F., and J. Arney. 2006b. On shaky ground. The Baltimore Sun, December 10. Accessed February 7, 2020. https://www.baltimoresun.com/business/real-estate/bal-groundrent1-12102006-story.html.

- Schuurman, N. 2006. Formalization matters: Critical GIS and ontology research. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 96 (4):726–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8306.2006.00513.x.

- Seymour, E., and J. Akers. 2019. Portfolio solutions, bulk sales of bank-owned properties, and the reemergence of racially exploitative land contracts. Cities 89 (June):46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2019.01.024.

- Seymour, E., and J. Akers. 2023. Decline-induced displacement: The case of Detroit. Urban Geography 44 (4):591–617. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2021.2008716.

- Shelton, T. 2018. Mapping dispossession: Eviction, foreclosure and the multiple geographies of housing instability in Lexington, Kentucky. Geoforum 97:281–91. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.09.028.

- Shelton, T. 2023. Challenging opacity, embracing fuzziness: Geographical thought and praxis in a post-truth age. Dialogues in Human Geography 2023:204382062311578. doi: 10.1177/20438206231157891.

- Sheppard, E. 2001. Quantitative geography: Representations, practices, and possibilities. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 19 (5):535–54. doi: 10.1068/d307.

- Siegel, A. 2011. Ground rents that had been canceled are resurrected. The Baltimore Sun, November 11. Accessed March 15, 2020. https://www.baltimoresun.com/maryland/anne-arundel/bs-md-ar-ground-rent-extinguish-20111106-story.html.

- Spielman, S. E., and J. R. Logan. 2013. Using high-resolution population data to identify neighborhoods and establish their boundaries. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 103 (1):67–84. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2012.685049.

- State of Maryland v. Stanley Goldberg, et al., 437 Md. 191, 85 A.3d 231 (2014).

- Taylor, K.-Y. 2019. Race for profit: How banks and the real estate industry undermined Black homeownership. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2020. Data from 2015–2019 American Community Survey 5-year estimates (data set). Accessed June 12, 2020. https://www.census.gov/data/developers/data-sets/acs-5year.html

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2022. Census Bureau releases estimates of undercount and overcount in the 2020 Census. Press Release CB22-CN.02. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2022/2020-census-estimates-of-undercount-and-overcount.html.

- Williams, K. 2008. Mark one or more: Civil rights in multiracial America. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Wilson, D., and M. Heil. 2022. Decline machines and economic development: Rust Belt cities and Flint, Michigan. Urban Geography 43 (2):163–83. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2020.1840736.

- Wyly, E. 2011. Positively radical. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 35 (5):889–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01047.x.

- Wyly, E. C., S. Ponder, P. Nettling, B. Ho, S. E. Fung, Z. Liebowitz, and D. Hammel. 2012. New racial meanings of housing in America. American Quarterly 64 (3):571–604. doi: 10.1353/aq.2012.0036.

- Zaimi, R. 2022. Rethinking “disinvestment”: Historical geographies of predatory property relations on Chicago’s South Side. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 40 (2):245–57. doi: 10.1177/02637758211013041.