Abstract

This article responds to recent calls to “provincialize” (Hawthorne Citation2019) and “pluralize” (Bledsoe and Wright Citation2019a) Black geographies. We do so by adopting a relational, transnational, and multiscalar approach. Drawing on ethnography with Black Lives Matter activists in Sydney, Australia, we adopt a decolonizing framework to argue that Indigenous knowledges, experiences, and actions can extend the epistemologies and cartographies of Black geographies. The mapping of Black geographies in Sydney reveals three multilayered and intersecting ways through which Black agency, place-making, and resistance are made manifest in transnational Black Lives Matter protests: (1) through invoking “stretched out” geographies, forging shared solidarities between African American high-profile cases of policing injustice and Aboriginal deaths in custody; (2) through counterhegemonic attempts to reconfigure Australia Day as Invasion Day, reclaiming colonized histories that subvert the premise of Australia as a “White nation”; and (3) through conjoining transrural cases of violence toward Aboriginal communities living in peripheral places and then strategically amplifying their concerns through place-based activisms in the global city. Finally, we conclude by arguing that further international accounts are crucial to this emerging field.

On 29 December 2015, David Dungay, Jr., a twenty-six-year-old Aboriginal man, exhaled his final breath before dying in his prison cell, at Long Bay Correctional Complex on Gadigal land in Sydney (Justice Action n.d.). David Dungay, Jr., a diabetic, purchased a packet of biscuits from the prison shop. Medical staff became concerned that his blood sugar levels were too high and made the decision to intervene as a “duty of care.” The Immediate Action Team stormed his cell after he refused to stop eating the biscuits. He was pinned face first onto the floor by six guards and forcibly injected with a sedative. Video evidence showed Dungay screaming, “I can’t breathe,” twelve times, to which one guard responded, “If you can talk, you can breathe” (Fuller et al. Citation2018). Dungay soon lost consciousness and was left on the floor for several minutes before anyone attempted resuscitation. David Dungay, Jr. died three weeks before he was due to stand before a parole hearing, with the coroner declaring there was no one to blame for his death. No charges were made against the prison guards involved (Davidson Citation2020).

The final words of David Dungay, Jr., when filtered through the optic of Black geographies (McKittrick Citation2006; McKittrick and Woods Citation2007), serve to map out a global archipelago of state violence enacted on Black bodies. In 2014, Eric Garner, an African American man, was killed in Staten Island, New York, after being placed into a chokehold by police officer Daniel Pantaleo. Despite screaming “I can’t breathe” eleven times, Garner’s pleas were ignored, and he died following an asthma attack (Jee-Lyn García and Sharif Citation2015, 27). In 2020, George Floyd, an African American man, was killed in Minneapolis, Minnesota, after police officer Derek Chauvin kneeled on his neck for nine minutes and twenty-nine seconds. Despite Floyd shouting “I can’t breathe” more than twenty times, he was starved of oxygen and pronounced dead at the scene (Singh Citation2020). It is thus an inescapable fact that David Dungay, Jr., Eric Garner, and George Floyd all uttered the same fatal final words. The statement “I can’t breathe” has not only given impetus to transnational solidarities but is now synonymous with Black Lives Matter activism worldwide.

In contrast, colonial legacies and the subjugation of Aboriginal peoples in the Antipodes connect to long-standing struggles for sovereignty and the dispossession of land (Moreton-Robinson Citation2020). The death of David Dungay, Jr. is then entangled in its own unique place-based histories. In 1987, the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody was formed in response to high incidences of Aboriginal deaths in custody during the 1980s, when more than 100 Aboriginal deaths were investigated (Cunneen Citation2001, 53). In 1991, the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody submitted its report to the federal government and made 339 recommendations. Very few of these recommendations have been implemented, however, and since the 1992 report, more than 572 Aboriginal peoples have additionally died in custody (Porter Citation2023). This makes the issue of racism in the criminal justice system central to campaigns for Black Lives Matter in Australia, demanding an end to Aboriginal deaths in custody.

The murder of George Floyd in 2020 led to a wave of global protests, anchoring Black Lives Matter firmly in the public consciousness. With few exceptions, though (see Joseph-Salisbury, Connelly, and Wagnari-Jones 2021; Balogun and Pędziwiatr Citation2023; Beaman et al. Citation2023), much of the scholarship has emerged in response to Black Lives Matter in the United States. Drawing on ethnographic work conducted in Sydney, Australia, this article explores the adoption and adaption of the Black Lives Matter movement, exposing the difference that place makes in how Black Lives Matter is understood and enacted transnationally. From its origins in the United States, we suggest that transnational Black Lives Matter activism can be understood through the different ways the movement is enacted, reshaped, and reconfigured across time and space. As such, transnational Black Lives Matter activism not only reshapes existing place-based activisms, but also rearticulates broader ideas and meanings of the movement. Moreover, unlike in the United States, Australia’s predominant Black Aboriginal population are Indigenous rather than exogenous, although the nomenclature might contingently include Torres Straits and South Sea Islanders, further complicating the established rubric of settler-colonial relations and the tripartite categories of settler, Indigenous, and exogenous.

The study is located at the intersection of debates on Black geographies, decolonization, and transnationalism. The triangulation is significant as Black studies and Indigenous studies tend to be bifurcated, with each making claims to modes of “exceptionalism” (Leroy Citation2016). In The Black Pacific—a generative elaboration on Gilroy’s (Citation1993) Black Atlantic—Shilliam (Citation2015) documented how in the early 1970s Māori and Pasifika youth in New Zealand “radically undermined the exceptionalist narrative that outlawed any potential connection between anti-Black racism and anti-Polynesian racism” (40) by affiliating with U.S. Black Power movements. Instead, Shilliam remarked how young African American radicals spoke more directly to Māori youth than many elders at the time. Indeed, Leroy (Citation2016) denoted how “slavery and settler colonialism share deep and overlapping histories” (1), whereas King (Citation2019) postulated how “Black and Indigenous life have always already been a site of co-constitution” (21). It is these intersectional activist histories and geographies of Black and Indigenous resistance we seek to illuminate.

Drawing on field work with Black Lives Matter activists in Sydney, we argue that Indigenous knowledges, experiences, and actions can extend the epistemologies and cartographies of Black geographies. By considering Black Lives Matter activism across time and space, we aim to contribute to the emergent literature on Black geographies through adopting a relational, transnational, and multiscalar approach. This is instrumental in unseating the U.S. hegemony on race, for as Hawthorne (Citation2019) noted, “There is an urgent need for Black Geographies research that considers the spatial politics of race and Blackness in other geographical contexts and draws attention to the ‘inherent pluralities’ of Black Geographies” (9). In response our aim is to extend and reconfigure Black geographies through engaging with transnational accounts of Black Lives Matter in Sydney and decolonial debates to identify the multiplicity of ways Black geographies are enacted.

We begin this article by reviewing the emergent corpus of work on Black geographies. Here, we distill some of its central tenets and put forward a case for transnational engagements that traverse the North American context. We then turn to our field work site outlining the unique geographies and histories of settler colonial racism in Sydney, Australia. In this section we discuss our research methods and critically engage with the problematic politics of decolonizing approaches when it comes to geographical theory, method, and practice. This is followed by our ethnography with Black Lives Matter activists to illuminate first how the movement is being adopted and adapted outside of North America as a transnational force, generating shared solidarities. Second, we show how Black Lives Matter disrupts Anglo-Australian nationalism through counterhegemonic decolonial practices responsive to Australia Day as a celebrated public holiday. Third, we show how such “uneven” forms of transnationalism radiate beyond the city to engage with rural issues that supersede the metropolitan focus familiar to much Black Lives Matter activism. Taken together we argue that these findings “provincialize” North American accounts and diversify the trajectories of Black geographies in the ways Hawthorne (Citation2019) intimated.

Black Geographies and the Case for Transnationalism

Recent years have witnessed a burgeoning interest in Black geographies. Evidence of its growing institutionalization is seen through the establishment of the Black Geographies Specialty Group of the Association of American Geographers in 2016, along with a coedited e-journal special issue on Black geographies in Southeastern Geographer (Bledsoe, Eaves, and Williams Citation2017). This nascent body of work is buttressed by a spate of recent reports on Black geographies in journals such as Progress in Human Geography (Derickson Citation2017; Allen, Lawhon, and Pierce Citation2019; Noxolo Citation2022), Geography Compass (Hawthorne Citation2019), and a themed intervention in Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers (Noxolo Citation2020). As other scholars denote, Black geographies is not a “new” field of enquiry but extends the long-standing traditions of radical geographies, urban ethnographies, and scholar-activist research on social justice (Allen, Lawhon, and Pierce Citation2019; Hawthorne Citation2019; Wood Citation2023).

Black geographies is an ontological category of study, replete with particular epistemologies. Core to this is an understanding that “Black matters are spatial matters” (McKittrick Citation2006, xii), as “all social relations are grounded in spatial relations” (Hawthorne Citation2019, 5). Black geographies focus on Black spatial knowledge and agency and how these translate into wider geographical visions of society (McKittrick and Woods Citation2007; Allen, Lawhon, and Pierce Citation2019; Noxolo Citation2022). In the United States, the “power-geometries” of race and space are particularly prescient given the forced displacement of Black bodies from Africa and the Caribbean during the slave trade, the rise of plantation economies in the Deep South, and subsequent Jim Crow laws on segregation. For McKittrick (Citation2006), such spatial demarcation forms the “demonic grounds” on which Black struggle, agency, and resistance are produced. As such, Black geographies not only delineate how the tortured histories and geographies of the “Black Atlantic” figure in the postcolonial present, but also enunciate the “polyphonic qualities of Black cultural expression” (Gilroy Citation1993) that result in global forms of creativity and radicalism. To this extent Black geographies illuminate Black agency in the production of space, generating alternative modalities of spatial practice.

A further contribution of Black geographies is a critical awareness that neoliberal economies are forged through racial capital. Rather than seeing race as simply an outcome or “epiphenomenon” of the economic base, adherents of Black geographies insist that racism and anti-Black violence remain a prerequisite for the perpetuation of capitalism, centering slavery and dispossession at the heart of economic relations in the formation of racial capital (Bledsoe and Wright Citation2019a; Hawthorne Citation2019). As labor historian Roediger (Citation1992) highlighted in The Wages of Whiteness, Whiteness operated as a form of currency in the nineteenth-century U.S. workplace. The first wave of colonial settlers from northern Europe, who were largely Anglo-Saxon Protestants, established their White superior status in juxtaposition to First Nation peoples, American “Negroes,” and uneducated Southern rural peasants. A later, second wave of immigration from southern and eastern Europe, including Irish Catholics, Italians, Jews, and various eastern European people were treated as less-than-White, but over time would forgo their ethnicities, assimilate, and settle for the illusory fiction they were “white workers” (Roediger Citation1994). By splitting the workforce across the “color bar,” capitalist proprietors held out the mantle of Whiteness as a mode of exchange to compensate for low wages and occupational insecurity. New immigrants could aspire to become “White workers,” enabling them to present as “honest,” “reliable,” and “the first hired and last fired.” The factory shop floor and blast furnace are then sites for the smelting of immigrant identities, where the newly minted “White worker” is formed on the capitalist production line and set apart from subsequent newcomers and the unassimilated American “Negro.” These critical insights not only reveal the malleability of Whiteness but extend its hegemony through the power of racial capital, where race and class intertwine in the making of differentiated racial demographics across the labor force.

Political activism, solidarities, and resistance are cornerstones of Black geographies and a necessary conduit for social change. As Bledsoe and Wright (Citation2019b) contended, such forms of Black activism are “inherently pluralistic.” Taking a comparative approach, they explored the Back to Africa nationalist separatist agenda of Marcus Garvey that sought to develop modern independent African nation states governed by Black people. In contrast, the Black Panthers aimed to instigate organic, grassroots communal autonomy within the United States by creating community networks and cooperatives beyond state government, with the aim to subvert brutal policing and improve health, education, and welfare for future Black generations. A third U.S. movement, The New Afrikans, sought to instill the type of self-determination that had been denied through enslavement by creating a “nation within a nation” (Bledsoe and Wright Citation2019b, 429), demanding government cede five states to African Americans as reparation for lack of rights through being classed as chattel. Each of these eclectic movements demonstrate that agency and political activism are sites for the proliferation of Black geographies that are always multiple, in excess, and uncontainable in both Anglophone thought and radical practice.

If the epicenter for Black geographies is the United States (Hawthorne Citation2019; Noxolo Citation2022), as Hawthorne (Citation2019) identified there is now pressing need to begin “provincializing North American understandings of race, racism and Blackness” (8) through further articulations of Black geographies. In Provincializing Europe, Chakrabarty (Citation2000) deployed this term to disrupt conventional European historical narratives that situate Europe as the original site of modernity, from which understandings of the non-Western world flow. For Chakrabarty (Citation2000), the project of modernity “is impossible to think of anywhere in the world without invoking certain categories and concepts, the genealogies of which go deep into the intellectual and even theological traditions of Europe” (4). Kaiwar (Citation2014), one of several critics, regarded the ambit of Chakrabarty’s historical gaze as “remarkably narrow, with rich descriptions on one side (Calcutta) and rather stark schematic outlines on the other (Europe)” (187); his formative critique stemming from a Marxist analysis that locates race and slavery as foundational to global capital. The implications of these strands of Black Marxism are evident where much Black geographies work foregrounds racial capital with its links to trans-Atlantic slavery and plantation economies (hooks Citation1982; McKittrick Citation2006; Bledsoe and Wright Citation2019a). Hawthorne’s (Citation2019) usage of “provincializing” carries some of the disruptive potential of rethinking Western epistemologies, but rather than negating U.S. accounts seeks to add nuance to Black geographies that “connect with [for example] Latinx and Native/Indigenous geographies” (2; see also King Citation2019).

There are some valuable international contributions to the field. In Black Resistance to British Policing, Elliott-Cooper (Citation2021) maintained that to understand antiracist struggles in twenty-first-century Britain, as characterized through movements like Black Lives Matter, it is vital to draw on connections with alternative Black liberation struggles of the past and present, to challenge evolving technologies of police violence. Although the Black Lives Matter movement is predominantly associated with the United States, and specifically in relation to police killings of Black young men (Leach and Allen Citation2017), recent studies show how the movement takes on alternative meaning elsewhere. For example, Balogun and Pędziwiatr (Citation2023) revealed how Black Lives Matter in Poland was stimulated through the hashtag #DontCallMeMurzyn (a Polish expression approximating “Negro”), and how this is refracted through longer histories of race and racism specific to the Polish context. In the United Kingdom, Joseph-Salisbury, Connelly, and Wangari-Jones (Citation2021) showed how Black Lives Matter has emerged in relation to structural racism in the criminal justice system, indicating why we should take seriously calls to defund and abolish the police in Britain.

Regional differences are further apparent in Ellefsen and Sandberg’s (Citation2022) interviews with thirty-eight predominantly young Black activists in Norway where, unlike the United States and United Kingdom, Black Lives Matter protests proceeded peacefully without infringement by right-wing counterdemonstrations. Further research on Black Lives Matter protests has taken place in France (Beaman Citation2021), as well as Denmark, Germany, Italy, and Poland (Beaman et al. Citation2023). Using social media and textual analysis, Shahin, Nakahara, and Sánchez (Citation2024) explored the hybridization of the movement in Brazil, Japan, and India, where certain issues may connect and become situated within a “resonant frame,” whereas others are resisted and relegated to a “reactionary frame” against Black Lives Matter. Through media analysis, they argued that “transnational contiguities and intra-cultural tensions” (216) shape the meanings of Black Lives Matter in these places.

Transnationalism has emerged as an important framework for going beyond the analytic scope of the nation-state, by recognizing the spatial interconnections of people, culture, objects, and economic arrangements (De Jong and Dannecker Citation2018, 494). The concept was particularly useful in early work on migration, offering a means to analyze the “multiple ties and interactions linking people, organisations or institutions across the borders of nation-states” (Vertovec Citation1999, 447). Following critiques that transnationalism neglects the impact of the nation state in terms of shaping power relations (Köngeter Citation2010, 179; Dahinden Citation2017, 1479), Levitt and Glick-Schiller’s (Citation2004) work on migration argued a broad understanding of transnationalism is necessary because migrant experiences are “Often embedded in multi-layered, multi-sited transnational social fields” (1003). Other scholars have responded to criticism by signaling that transnationalism, rather than making the nation-state “obsolete,” has redefined its role as a framework in understanding social phenomena (Osterhammel 2001, cited in Pence and Zimmerman Citation2012, 496; Vertovec Citation2004, 978).

Transnationalism is a critical concept for understanding the global circulation of Black activism. In research on Black political activism, Featherstone (Citation2013) demonstrated how African American volunteers linked the Spanish Civil War to Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia and translocal struggles against White supremacy in the United States. Gowland (Citation2022) also adopted a transnational perspective, exploring how the Bermudian Black Power movement was at the heart of a series of “transnational circulations” making connections to Black Power political formations in the Caribbean and North America, while constituting “a politics of resistance to transnational geographies of white supremacy” (867). There are echoes here of Shilliam’s (Citation2015) research with migrant Pacific youth in New Zealand, where the conjoining of Māori and Pasifika experiences with U.S. Black Power movements ultimately amplifies and extends solidarities and resistance to racism. Bledsoe and Wright (Citation2019a) discussed the collective activism arising from a self-sufficient Brazilian Afro-descendant fishing community in Ilha de Maré, following an oil and chemical spill in the Bay of Aratu, decimating the marine life locals depended on. They argued that Black lives are treated as “a-spatial” and exterior to humanity, where “anti-Blackness is actually a prerequisite for global capitalism” (22). In postapartheid South Africa, Wood (Citation2023) deployed Black geographies to understandings of public transport mobility. In the apartheid era, roads were used to delineate Black and White neighborhoods, governing access to the city. In the postapartheid era, however, public transport provides opportunities for social and spatial transformation generating possibilities for different and diffuse Black geographies.

As De Jong and Dannecker (Citation2018, 497) indicated, we are now in a third phase of work on transnationalism, which seeks to bring the concept into dialogue with other fields of research, such as diaspora and border studies. We contend that bringing the transnationalism into concert with Black geographies by way of Black Lives Matter can develop complex, multilayered, and nuanced understandings of racism, decoloniality, and resistance. The concept also enables us to capture Australia’s diverse Aboriginal communities, including South Sea Islanders and Torres Strait people who are a formative part of Pacific Black Lives Matter insurgencies. Rising to Hawthorne’s (Citation2019) challenge to “provincialize” U.S. understandings of Black geographies, extend these epistemologies beyond the Northern Hemisphere, and proliferate Native and Indigenous geographies, we critically analyze transnational political solidarities, decolonial practices, and antiracist activism in Sydney, Australia.

Situating Sydney, Becoming Decolonizing

Situating Sydney

Sydney has a population of more than 5 million people of which 1.5 percent are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, who comprise the largest of Australia’s diverse Indigenous populations (World Population Review Citation2022). The 2021 Census records the largest exogenous population in Sydney is the English (21.8 percent), followed by those heralding from China (11.6 percent). The triangulation between settler, Indigenous, and exogenous populations make Sydney a vibrant site for the execution, and indeed dissemination, of Black geographies. The Gadigal of the Eora Nation are the traditional custodians of land in Sydney, having inhabited it “since the beginning” (Creative Sprits 2021). Modern-day Sydney was established in April 1770, when HMS Endeavour, captained by James Cook, docked at Botany Bay. The colony of New South Wales was later formed in 1788 when Captain Arthur Phillip arrived with a fleet of eleven vessels carrying more than 1,000 people, including 778 convicts (Phillip Citation2015, 34).

The arrival of British settlers in Australia marks a key event in understanding how legacies of colonialism relate to contemporary struggles for sovereignty, self-determination, and land rights. The arrival of settlers had a devastating impact on Indigenous communities across Australia, through a wave of communicable diseases that were responsible for the depopulation of hundreds of thousands of Aboriginal peoples (Bultin Citation1993, 99). In Sydney, such spreading of disease is believed to have killed approximately half of all Aboriginal peoples (Aboriginal Heritage Office n.d.). As Britain expanded its settlements along the east coast (on land in Brisbane and Melbourne), it responded to resistance by massacring thousands of Aboriginal peoples (Barta Citation1987, 237). The violence attributed by the arrival of the British Empire to Aboriginal communities is illustrated in the diary of Anglo-Australian journalist Edward Wilson ([Citation1856], cited in Harris Citation2013):

In less than twenty years we have nearly swept them off the face of the earth. We have shot them down like dogs. In the guise of friendship, we have issued corrosive sublimate in their damper and consigned whole tribes to the agonies of an excruciating death. We have made them drunkards and infected them with diseases which have rotted the bones of their adults, and made such few children as are born amongst them a sorrow and a torture from the very instant of their birth. We have made them outcasts on their own land and are rapidly consigning them to entire annihilation. (209)

In recent years, Sydney has emerged as one of the most prominent sites of Black Lives Matter activism outside of the United States. In 2016, activists marched to Sydney Townhall in response to Aboriginal deaths in custody, police brutality, and the wider racialization of the criminal justice system (Black Lives Matter Sydney Citation2016), and in 2017, U.S. Black Lives Matter figures visited Sydney in solidarity with Aboriginal peoples who “sadly [face] similar conditions to those of the US and Canada” (Cullors and Diverlus Citation2017). Such bridge-building exercises, conjoining Black and Indigenous studies, showcase the transnational and intersectional links between global Blackness and Indigeneity, racism, and decolonization. A state-wide Black Lives Matter protest was held in Sydney following the death of George Floyd in 2020. Activists stood in solidarity with African Americans, but also drew attention to Aboriginal struggles of racial violence in Australia (Henriques-Gomez and Visontay Citation2020) and White settler territorial dispossession. As such, antiracism is deeply connected to decolonization in the Australian context, reflective of how Black Lives Matter activism manifests in Sydney.

Becoming Decolonizing

Our analysis draws on ethnographic research conducted over a ten-month period in Sydney. This includes thirty semistructured interviews undertaken with Black, Aboriginal, Torres Straits, and South Islander activists; participant observation at protests and decolonial events; the use of digital methods to access Black Lives Matter forums; and the collection of ephemera such as posters, images, and artifacts. Sydney is an exemplar of transnational Black geographies where the voices of diverse Aboriginal participants contribute to the elaboration and reshaping of Black Lives Matter. The methodology is informed by decolonial scholarship and its attempt to unsettle the notion of “researcher as expert” and challenge colonial disciplinary epistemologies (Foley Citation2011; Tuck and Yang Citation2012; Daigle and Sundberg Citation2017; Radcliffe Citation2017; De Leeuw and Hunt Citation2018; Watego Citation2021).

Furthermore, a “settler colonial theory” framework (Jordan Citation2022) can help heal the “impasse” (Leroy Citation2016) between Black and Indigenous studies. Such cross-cutting approaches are supported by King (Citation2019), who sought to place “Black studies into a productive friction with settler colonial studies” (19), whereas Glenn (Citation2015) argued that settler colonialism is “a framework amenable to intersectional understanding” (55). Taking settler colonialism seriously can build alliances, advance decolonization, and highlight the multitude of racisms that pepper global societies. The nascent field of Black geographies can aptly build on a scaffolding of postcolonial (Fanon Citation1965; Said Citation1978; Bhabha Citation1994) and decolonial studies (Tuck and Yang Citation2012; Daigle and Sundberg Citation2017; Nayak Citation2023), critical race theory and critical Whiteness studies (Crenshaw, Gotanda, and Peller Citation1995; Delgado and Stefancic Citation2001; Nayak Citation2007); Black, queer, and Indigenous feminisms (Davis Citation1981; hooks Citation1982; Hill-Collins Citation1990; Crenshaw Citation1991; Barker Citation2015; Radcliffe Citation2017); as well as antiracist activist and environmental struggles (Pulido Citation2017; Bledsoe and Wright Citation2019a; Moulton and Salo Citation2022).

Given the brutality of settler-colonial violence, it would be naive to assume we can decolonize geographical research overnight, although as Barker and Pickerill (Citation2020, 641) suggested, we can at least “become decolonizing” by highlighting and mobilizing decolonizing tendencies. This is attempted in partial, tentative, and fragmented ways. To instigate this process, we began by situating Sydney through a “colonial matrix” of power (Quijano Citation2000) and will go on to explicate how the modernist era of colonialism connects to the contemporary policing and violent geographies of the global city. Second, we recognize our contingent subjectivities, privileges, and positionalities. Dan identifies as White British, is an early career researcher living in the Global North, who received UK government funding for his research. As such, his Whiteness created an “invisible set of unearned privileges” (McIntosh Citation1989) translating into power differentials that feed into the doing of research with Aboriginal peoples. Although Whiteness remains a tension in research on race, many encounters with Aboriginal peoples in Sydney exposed “common ground” (Pickerill Citation2009), based on relational experiences of coming from a working-class background.

Anoop identifies as Black British, has academic tenure in the Global North, and over the last twenty years has benefited from funded scholarships and invites to Australia. On an extended sabbatical, he rented a house in a multiethnic suburb and was mis/recognized by the local Aboriginal community as a “brother,” premised on phenotype and then shoulder-length hair. Such convivial neighborhood encounters were tempered with other incidents, such as being routinely followed by security in local stores, accused of stealing, and being subject to stop and search processes at border control. These heightened lived experiences offer a cursory insight into the emotional, embodied, and relational experience of Indigeneity, but one that was always supported by a mobile set of Global North academic privileges.

Third, “becoming decolonizing” means being reflexive of our disciplinary methodologies and ontologies, including an awareness that geography is tethered to an imperial past and remains a predominantly White discipline (Delaney Citation2002; Desai Citation2017). Drawing on the guidance of Creative Spirits (Korff Citation2021), we use the term Aboriginal throughout, as it was the preferred terminology through which participants identified themselves. Furthermore, our chosen research method of ethnography derives from anthropology, a discipline that adopted a colonial gaze rendering native populations “primitive,” “savage” or “exotic,” thus setting them apart from common humanity. As Wolfe (Citation1999) scathingly asserted, much anthropology has little to impart about Indigenous beliefs and more to say about European colonial discourse. Rather than seeing the arrival of White-Anglo settlers as an event, Wolfe regarded it as an ongoing structure. This forms a colonial matrix where “Settlers’ position at the apex is a sovereign ascendance dependent on keeping the Indigenous and Exogenous in lower and oppositional vertices” (Jordan Citation2022, 466). Given this triangular construction of otherness, we were led to question how we might conduct research “otherwise.” Fourth, in response to this question, we learned to engage in what Back (Citation2007) called “listening with the eye,” substituting the “researcher as expert” with “researcher as active listener.” Evie, an Aboriginal woman, lucidly explained the limits of the modernist framework of “ethical approval”:

You have to be prepared to listen. We have had enough of having others speaking for us. Our voice, our teachings, need to be heard. We can speak for ourselves.

Shared Solidarities: “Stretched Out” Geographies and Black Lives Matter

In dialogue with Black Lives Matter in the United States, our research in Australia found the issue of Aboriginal deaths in custody was at the forefront of campaigns. Evie, an Aboriginal woman and organizer of Black Lives Matter protests in Sydney, who we heard from previously, discussed the transnational connections between high-profile Black and Aboriginal deaths in custody:

In my cousin’s case, David Dungay, you can see Eric Garner. We shadow these two cases from America to here because our poor brother Eric over there and my cousin David here. Their last words that are physically seen and recorded on fucking video are, “I can’t breathe.” (Evie)

Caroline, an Aboriginal woman and community activist, also stretched the contours of Black geographies to make Aboriginal deaths in custody legible within the Australian context:

There are lots of similarities between Black Lives Matter and the oppression by police of Aboriginal people [in Australia] and First Nations in North America as well. These are issues that we have been addressing for quite a long time. What the Black Lives Matter movement has done, is to publicize, and use social media to highlight and document those crimes as they actually occur and then raise the issue more generally. Globally, as well.

Although transnational connections are an important element of Black Lives Matter in Sydney, this is not to suggest that participants viewed this as an extension of the U.S. movement. Like the migrant Pasifika youth Shilliam (Citation2015) discussed, who in 1971 inaugurated the Polynesian Panther Movement in Aotearoa New Zealand, they were heavily influenced by the U.S. Black Panthers, but also sought to reclaim the past heritages that their parents had to leave behind, including traditional clothing and hairstyles. Sydney activists similarly sought to create an interconnected, yet distinct place-based Black Lives Matter movement in dialogue with long-standing issues for Aboriginal, Torres Straits, and Australian South Sea Islanders. For example, Amanda, an Australian South Sea Islander woman, is part of a Sydney-based organization representing the rights of Australian South Sea Islanders.

Amanda: That’s one thing that I did say, we have always had a Black Lives Matter initiative. … Black Lives Matter might be the catch of the day and we are going to ride that wave.

What did you do?

Amanda: I took that slogan straight away, put it on t-shirts and took it to our people to ride it. I put it in the background, and we had a layered effect of Black Lives Matter in the background.

Why did you do that?

Amanda: To ride the wave. It gives more appeal and brings more people together in our struggle.

Amanda’s metaphor, “ride the wave,” is not insignificant. Pacific Islanders are widely credited with inventing surfing (Osmond Citation2011), so her statement, “We have always had a Black Lives Matter initiative,” similarly indicates that antiracist activism, like surfing, is not a U.S. import. Instead, she used the platform to hydraulically “elevate” (Mundine Citation2021, 18) local struggles transnationally. This is significant, not only at a transnational scale, but also within the nation-state, for as Quanchi (Citation1998, 31–32) indicated, despite not being native, Australian South Sea Islanders have long experienced comparable experiences of racial violence to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, yet their rights have largely gone ignored by the state. In this context, Black Lives Matter not only enables Australian South Sea Islanders to affirm “Oceanic connections” (Shilliam Citation2015) with Aboriginal and Torres Strait communities, but also draws attention to their own distinct struggles as they circulate, ebb, and flow through the Pacific diaspora. Blackness is mobilized as a unifying mode of political identification, binding South Sea Islanders with various Aboriginal and Torres Strait peoples, in a global decolonial project. These shared solidarities of Oceania stretch beyond the parochialism of the United States, and signal the pluralistic, intersectional nature of transnational Black geographies.

Invasion Day: Disrupting Nationalism, Producing Oppositional Black Geographies

In her pioneering monograph Battle for the Flag, Johns (Citation2015) offered the earliest empirical analysis of events surrounding the Cronulla Riots that took place in a coastal suburb on the outskirts of Sydney in 2005. We contend that the “battle for the flag” is an ongoing psychosocial spectacle, connected to Australia’s postcolonial present and its manifestation as a “White Nation” (Hage Citation1998). January 26 marks Australia Day, when Australians celebrate the birth of a nation, marking the anniversary of the arrival of British settlers. The national holiday is associated with beach barbeques, picnics in the park, and street events. It is increasingly becoming a source of national rupture, however, where Aboriginal, Torres Strait, and South Sea Islanders protest against the historic marginalization and violence toward Indigenous communities. This repositions the event as a settler-colonial “structure of invasion” (Wolfe Citation1999). On the way to a rally in Hyde Park, Clare, an Aboriginal woman from Melbourne, temporarily working in Sydney as a children’s entertainer, was wearing a Black Lives Matter t-shirt. She explained its significance:

Clare: I wear it because if I change one mind, then that is good for our struggle.

Whose mind do you want to change?

Clare: Everyone’s. Black Lives Matter showed regular people in the world that racism and oppression exist. And by wearing it [the t-shirt], I hope that one person sees this and thinks about why they are celebrating Australia Day. … Aboriginal people are Black too. It’s all about changing minds. (Ethnographic notes: Clare at Invasion Day 26 January 2020)

For participants like Clare, Black Lives Matter is deployed “for our struggle.” She denoted how in the settler imagination, “Aboriginal people are Black too.” Reinscribing Invasion Day against the normative grammar of Australia Day visibly maps Black geographies in ways connected to the nation’s traumatic colonial matrices in the past. For Allen, Lawhon, and Pierce (Citation2019, 1012) this illustrates how Black geographies can be articulated through forms of “relational place-making.” Clare referred to herself as a “fair-skinned Aboriginal woman,” who identifies as Black, opening up spaces of “in-betweenness” and ambivalence within the tripartite relations of settler, Indigenous, and exogenous. That Black Lives Matter touched “regular people” indicates that White people are no longer absolved from race matters. Ultimately, the national celebration of Australia Day can be seen as “enacting a White fantasy of national space” (Hage Citation1998, 22), a ritual means of “purging the nation” (Nayak Citation2017) from its dark colonial past and rising multicultural present.

The compelling trajectories of Invasion Day festivities were evident in a march to Yabun in 2020, for an event held in Victoria Park, Central Sydney, in recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders cultures. Grayson, an Aboriginal man with a strong presence in Black Lives Matter, generated a call-and-response chant, yelled through a megaphone:

Always was, always will be, Aboriginal land!

…

When I say accident, you say murder. Accident … murder! Accident … murder!

…

Whose lives matter? Black lives matter! Whose lives matter? Black lives matter! (Ethnographic notes: Invasion Day 26 January 2020)

A series of issues arise, however, at the intersection between Black geographies and transnational Black Lives Matter activism, connecting Black and Indigenous studies. Grayson’s mention of land is prescient, carving out distinct Black geographies that transcend solidarities and sameness with the United States. The battle for the flag is premised on grounds of terra nullius—the acquisition of “no person’s land” as state territory—which has become enshrined in law, resulting in geographies of appropriation and illegal land dispossession. As Tuck and Yang (Citation2012) noted in a key intervention on decolonization, “Settlers become the law, supplanting Indigenous law and epistemologies” (6–7). These relations structurally locate Aboriginal peoples at the base of the settler, Indigenous, and exogenous pyramid (Jordan Citation2022), as either less-than-human or nonhuman. Indeed, the police in Australia have been pivotal in violently enforcing the dispossession of Aboriginal peoples from their land (Cunneen Citation2020), disclosing the management of national space (Hage Citation1998). Through the assertion of timeless ancestral land rights, “always was, always will be,” Grayson, along with other Aboriginal, Torres Straits, and South Sea Islanders, deploy Black geographies to mark out altogether different understandings of time, space, and landscape. As such, they are implicated in territorial “doings” as “active, relational and embodied practices” (Barker and Pickerill Citation2020, 640), running counter to the White hegemonic constitution of Australia Day. What is at stake in the battle for the flag, epitomized by the split between Australia Day and Invasion Day, are core understandings of what it means to be human; a spectacle that routinely draws on discourses of citizenship, sovereignty, and territory. The battle is ongoing. Following the 2023 Referendum to alter the Australian Constitution and politically recognize First Nations by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice, over 60 percent of Australians voted against the measure. This suggests that the modern “White Nation” (Hage Citation1998), and by implication the materialization of White humanity, is dependent on the suffocating silencing of Black and Aboriginal voices as part of its condition of existence, epitomized by “I can’t breathe.”

Rural Connectivity: The City as Amplifier for Transrural Black Geographies

Despite the transnational emergence of Black Lives Matter in recent years, the movement is widely recognized for its activism in urban environments (Spencer Citation2017, 21). Indeed, Kelly and Lobo (Citation2017) highlighted the “quiet” and “noisy” ways that Aboriginal peoples demonstrate agency through street protests and holding vigils in attempting to reclaim access to public space in the urban contexts of Broome (Western Australia) and Darwin (Northern Territory). The transnational case of Sydney reveals a further dynamic, however, where the urban is also employed as a strategic site to draw attention to rural forms of race violence. Our ethnography uncovered a multitude of racialized police encounters in rural environments, which, despite being met with community protest, had limited impact because of their isolated location. Maria, an Aboriginal woman, organized a state-wide Black Lives Matter protest in Sydney together with multiple families from small rural towns beyond the north of the city. She, like her fellow rural activists, had experienced the loss of Aboriginal family members, whose deaths were insufficiently investigated by the police.

We need to be seen because in our hometowns, we don’t get seen. We don’t get heard. Folk have been waiting thirty-plus years to get justice. But we don’t get heard, we don’t get seen. We have to find a way to be seen. Not just Australia, I want the world to see that this is what we face over here. … There were heaps of people getting involved. We had people joining in. Black Lives Matter is a powerful thing. The atmosphere was powerful. (Maria)

Despite organizing protests in rural towns, Maria indicated many families felt dismissed by the legal apparatus and had little voice in garnering support outside of their communities, “We don’t get seen. We don’t get heard.” There is widespread belief that many of these cases would not have gained traction had they not coordinated together and deployed Black Lives Matter as an organizing principle for protest. A strength of Black Lives Matter has been its ability to shape solidarities among differently racialized people (Hope Citation2019, 223), and Maria suggested that by building solidarities with Black Lives Matter, illegitimate Aboriginal deaths can be heightened not only in the national consciousness, but “the world.” Through these Oceanic connections, Maria aimed to develop a global critical consciousness to Aboriginal rights. Her observation, “The atmosphere was powerful,” builds on Ellefsen and Sandberg’s (Citation2022, 1104) argument of the importance of emotions to research on activism and the “global diffusion” of Black Lives Matter following the murder of George Floyd. Furthermore, the rally exposed how systemic injustices tied to the deaths of multiple young Aboriginals cannot be reduced to isolated acts of racism or police violence but are part of a continuum (Joseph-Salisbury, Connelly, and Wagari-Jones 2021, 26), where genocide and colonial conquest has enabled White humanity to transpire (Hage Citation1998; King Citation2019).

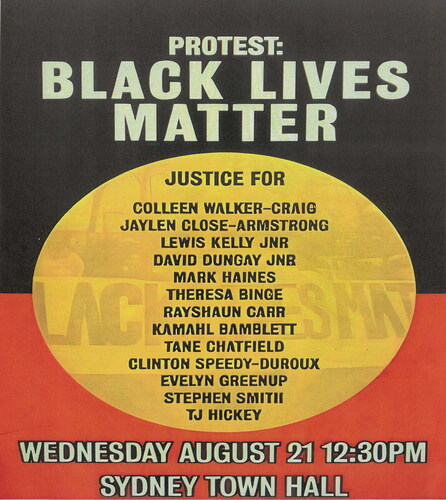

demonstrates the multiscalar potential of Black Lives Matter, connecting parochial rural cases to the regional New South Wales state-wide rally, through national and transnational intersections. The poster used to disseminate information at the rally provides details of the names of young Aboriginal peoples who prematurely lost their lives and whose families continue to fight for justice. The backdrop of the poster provides a powerful visual of the Australian Aboriginal flag. Indigenous knowledge, doings, and practices are evident in the poster where the color black represents Aboriginal peoples, red the dusty earth, and ocher—a color used in ceremonies—the burning sun. Moreover, the flag intimates the powerful connection that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders have with the land and natural environment. The words “Black Lives Matter” emphasize the validity of the movement in the Australian context and its unique connection to Aboriginal rights.

The rural town protests Maria mentioned failed to gain enough attention to generate any form of political or legal action. When asked why she chose Sydney, Maria highlighted the importance of causing disruption and holding the protest in front of Sydney Town Hall, where the mayor and city council reside. For both her and Grayson, “maximum disruption” is a necessity to “being heard”:

We shut the CBD [Central Business District] down. We pretty much shut it down. That was my plan. … I am originally from the coast, where my brother was found [over thirty years ago] on the tracks up in Kempsey. Now, we have rallies in that town, but they don’t go nowhere. It doesn’t go any further, so I thought, all of these families having rallies in their own little communities, and they don’t go nowhere. We need to do something in front of the government. We have to do something at state level. …

Since I had that march, the rally, we shared a lot of stories and how we do things individually as families. And we went away with knowledge. Especially the ones that have never been to Sydney before, they went away with their family with ideas of what to do next. (Maria)

Maria’s account also demonstrates the importance of strategic “place-based activity” in shaping solidarities (Featherstone Citation2012, 30), as diverse rural locations, such as Bowraville, Kempsey, and Toowoomba, gained media coverage under the conceptual umbrella of Black Lives Matter in Sydney. As such, Black geographies are “always erased and yet always present” (Noxolo Citation2022, 1233). Remapping Black geographies of resistance through such relational placed-based activities in Central Sydney enables more remote rural cases of racial violence to coalesce and cohere in meaningful ways. As other scholars have pointed out, the disconnect between rural and urban sites of protest often results in rural Indigenous voices being unrepresented, misrepresented, or misunderstood (Barker and Pickerill Citation2012, 1717; Cremaschi Citation2021, 7). Notably, the Black Lives Matter movement in Sydney not only shapes the activism of rural families, but their cases penetrate broader ideas of Black Lives Matter that come to reshape the Sydney movement. In doing so, they mark out definitive Black geographies that unsettle, disrupt, and counter commonplace metropolitan assumptions of Black Lives Matter as a solely urban movement.

Conclusion: Black Geographies as Relational, Transnational, and Multiscalar

Our study is consciously located at the crossroads of scholarship on Black geographies, Indigenous social movements, decolonization, and transnationalism. This enables new cartographies of place-making and activism to be made intelligible. Simultaneously, it demands a global engagement with the colonial present and how the rarified construct of White humanity coheres through a proliferation of rarified and racialized markers of difference used to assemble the subhuman.

A primary aim has been to bring Black geographies into concert with the concept of transnationalism to view how Black Lives Matter is enacted in Sydney, Australia. In doing so, we respond to current calls to “pluralize” (Bledsoe and Wright Citation2019b) and “provincialize” (Hawthorne Citation2019) Black geographies, by traversing the North American context, and displacing the broader U.S. framing of race scholarship. Our approach has been critically informed by decolonial epistemologies, cognizant of the fact that decolonization is “not a metaphor” but involves the ceding of territories (Tuck and Yang Citation2012) and “unsettles” geographical thought and ways of knowing (Daigle and Sundberg Citation2017). It might then be a conceit to position ourselves and our practices as “decolonial,” where more accurately we are working toward “becoming decolonizing” (Barker and Pickerill Citation2020). Notwithstanding these concerns, we demonstrate the utility of settler-colonial theory as an intersectional, coconstitutive framework (Glenn Citation2015; King Citation2019), where decolonial perspectives can transcend the “impasse” between critical race and Indigenous studies (Leroy Citation2016).

Through an exposition of Black Lives Matter in Sydney, we identify three repertoires of activity, each contributing to the transnational mapping of Black geographies by shedding light on Black agency, place-making, and resistance. The first highlights how Sydney activists create “stretched out” geographies and shared solidarities between African American high-profile cases of policing injustice and Aboriginal deaths in custody. In this way, our participants circumvented the barriers of time and space, actively “shadowing” (Evie) what was happening in the United States and knowingly “riding the wave” (Amanda). As such they were implicated in processes of “relational place-based making” (Allen, Lawhon, and Pierce Citation2019), used to propel Black geographies in the Australian context through the message that Black Lives Matter “here,” not “here as well.” A further strand in this activity network is the multiscalar ways in which participants proved adept at adopting and adapting Black Lives Matter, enabling the movement to land in such a way that it could connect to the local, national, and pan-Pacific circumstances of Aboriginal, Torres Straits, and Australian South Sea Islanders in the forging of “Oceanic connections” (Shilliam Citation2015).

A second repertoire sought to disrupt nationalism and “hollow out” the premise of Australia as a “white nation” (Hage Citation1998). The attempt to reclaim colonial histories culminates in Invasion Day being transposed over the banal Whiteness of Australia Day. In this counterhegemonic interpretation, Australia Day is disclosed as an event saturated in Whiteness, nationalism, and the violent erasure of Black bodies. Activists firmly situate Invasion Day through a colonial matrix, casting light not only on the brutality of the past, but also on the present plight of Australia’s Aboriginal peoples. These highly charged encounters are symptomatic of the “battle for the flag” (Johns Citation2015), symbolized in material objects and ephemera, including activist banners, Black Lives Matter t-shirts, placards, emblems, posters, ensigns, and other paraphernalia. The Black geographies enacted here archive inglorious histories and geographies, are oppositional in nature and are used to stimulate debates on sovereignty, land rights, nationhood, and racism. This marks the production of Black geographies in opposition to White governance and territoriality.

A third repertoire aims to develop transrural connections among Aboriginal communities living in peripheral places, the objective being to raise national and global consciousness of police institutional racism when it comes to the deaths of Aboriginal peoples in remote areas. Having failed to gain much traction through isolated local rallies, activists sought to amplify the cause by connecting rural cases to one another and strategically amplifying them through “high-voltage” place-based activities in the global city. This includes mobilizing protest within the heart of Sydney, demonstrating in front of local government, and creating “maximum disruption” (Maria) through attempts to shut down the CBD. The mapping of rural Black geographies involves bringing hitherto silenced cases to light, making Aboriginal deaths in peripheral areas audible, visible, and accountable. Participants stand in solidarity with the United States, but also demonstrate agency through creating relational place-based movements that reflect their own pan-Pacific struggles. Collectively, the three repertoires pluralize and proliferate Black geographies through transnational practices. If Black geographies are to progress in ways that are pluralistic rather than provincial, we contend that further international accounts are vital to proliferating and diversifying this emerging field.

Acknowledgments

We are immensely thankful to our research participants for sharing their time and experiences with us. We are grateful for the thoughtful comments and insightful suggestions provided by two anonymous reviewers and to the editors at the Annals of the American Association of Geographers for their support throughout the process. We would also like to extend our thanks to Alastair Bonnet (Newcastle University) and Craig Jones (Newcastle University) for their valuable feedback throughout the field work. All authors contributed equally to this article and any errors remain our own.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Daniel Barwick

DANIEL BARWICK received his PhD in Human Geography from the School of Geography, Politics & Sociology at Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU, UK. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests are in the fields of race and racism, Indigenous rights, and transnational activism.

Anoop Nayak

ANOOP NAYAK is Chair in Social & Cultural Geography at Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU, UK. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests are in race, ethnicity, and migration; young masculinities and social change; Black geographies; and decolonial thinking.

References

- Ahenakew, C. 2016. Grafting Indigenous ways of knowing onto non-Indigenous ways of being: The (underestimated) challenges of a decolonial imagination. International Review of Qualitative Research 9 (3):323–40. doi: 10.1525/irqr.2016.9.3.323.

- Allen, D., M. Lawhon, and J. Pierce. 2019. Placing race: On the resonance of place with Black geographies. Progress in Human Geography 43 (6):1001–19. doi: 10.1177/0309132518803775.

- Back, L. 2007. The art of listening. London: Bloomsbury.

- Balogun, B., and K. Pędziwiatr. 2023. “Stop calling me Murzyn”—How Black Lives Matter in Poland. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (6):1552–69. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2022.2154914.

- Barker, A. J. 2015. “A direct act of resurgence, a direct act of sovereignty”: Reflections on Idle No More, Indigenous activism, and Canadian settler colonialism. Globalizations 12 (1):43–65. doi: 10.1080/14747731.2014.971531.

- Barker, A. J., and J. Pickerill. 2012. Radicalizing relationships to and through shared geographies: Why anarchists need to understand indigenous connections to land and place. Antipode 44 (5):1705–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.2012.01031.x.

- Barker, A. J., and J. Pickerill. 2020. Doings with the land and sea: Decolonising geographies, Indigeneity, and enacting place-agency. Progress in Human Geography 44 (4):640–62. doi: 10.1177/0309132519839863.

- Barta, T. 1987. Relations of genocide: Land and lives in the colonization of Australia. In Genocide and the modern age: Etiology and case studies of mass death, ed. I. Wallimann and M. Dobkowski, 237–53. New York: Syracuse University Press.

- Beaman, J. 2021. Towards a reading of Black Lives Matter in Europe. Journal of Common Market Studies 59 (1):103–14.

- Beaman, J., N. Doerr, P. Kocyba, A. Lavizzari, and S. Zajak. 2023. Black Lives Matter and the new wave of anti-racist mobilizations in Europe. European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology 10 (4):497–507. doi: 10.1080/23254823.2023.2274234.

- Bellear, R. 1976. Black housing book. Broadway, NSW, Australia: Amber Press.

- Bhabha, H. 1994. The location of culture. London and New York: Routledge.

- Black Lives Matter Sydney. 2016. Sydney Black Lives Matter anti police brutality group. Accessed July 1, 2023. https://www.facebook.com/events/1751011715157671/.

- Bledsoe, A., L. Eaves, and B. Williams. 2017. Introduction: Black geographies in and of the United States South. Southeastern Geographer 57 (1):6–11. doi: 10.1353/sgo.2017.0002.

- Bledsoe, A., and W. J. Wright. 2019a. The anti-Blackness of global capital. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 37 (1):8–26. doi: 10.1177/0263775818805102.

- Bledsoe, A., and W. J. Wright. 2019b. The pluralities of Black geographies. Antipode 51 (2):419–37. doi: 10.1111/anti.12467.

- Bultin, N. G. 1993. Economics and the dreamtime: A hypothetical history. Melbourne, Australia: Cambridge University Press.

- Chakrabarty, D. 2000. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial thought and historical difference. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Creative Spirits. 2021. What is the correct term for Aboriginal people? Accessed June 4, 2023. https://www.creativespirits.info/aboriginalculture/people/how-to-name-aboriginal-people.

- Cremaschi, M. 2021. Place is memory: A framework for placemaking in the case of the human rights memorials in Buenos Aires. City, Culture and Society 27:100419. doi: 10.1016/j.ccs.2021.100419.

- Crenshaw, K. 1991. Mapping the margins: Identity politics, intersectionality, and violence against women. Stanford Law Review 43 (6):1241–99. doi: 10.2307/1229039.

- Crenshaw, K., N. Gotanda, and G. Peller, eds. 1995. Critical race theory: The key writings that formed the movement. New York: The New Press.

- Cullors, P., and R. Diverlus. 2017. Black Lives Matter in Australia: Wherever Black people are, there is racism—and resistance. The Guardian. Accessed May 7, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/nov/02/black-lives-matter-in-australia-wherever-black-people-are-there-is-racism-and-resistance.

- Cunneen, C. 2001. Assessing the outcomes of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. Health Sociology Review 10 (2):53–64. doi: 10.5172/hesr.2001.10.2.53.

- Cunneen, C. 2020. Conflict, politics and crime: Aboriginal communities and the police. London and New York: Routledge.

- Dahinden, J. 2017. Transnationalism reloaded: The historical trajectory of a concept. Ethnic and Racial Studies 40 (9):1474–85. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2017.1300298.

- Daigle, M., and J. Sundberg. 2017. From where we stand: Unsettling geographical knowledges in the classroom. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 42 (3):338–41. doi: 10.1111/tran.12201.

- Davidson, H. 2020. The story of David Dungay and an Indigenous death in custody. The Guardian, June 11. Accessed October 11, 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/jun/11/the-story-of-david-dungay-and-an-indigenous-death-in-custody.

- Davis, A. 1981. Women, race, & class. New York: Vintage.

- De Jong, S., and P. Dannecker. 2018. Connecting and confronting transnationalism: Bridging concepts and moving critique. Identities 25 (5):493–506. doi: 10.1080/1070289X.2018.1507962.

- De Leeuw, S., and S. Hunt. 2018. Unsettling decolonizing geographies. Geography Compass 12 (7):1–14. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12376.

- Delaney, D. 2002. The space that race makes. The Professional Geographer 54 (1):6–14. doi: 10.1111/0033-0124.00309.

- Delgado, R., and J. Stefancic. 2001. Critical race theory: An introduction. New York: New York University Press.

- Derickson, K. D. 2017. Urban geography II: Urban geography in the Age of Ferguson. Progress in Human Geography 41 (2):230–44. doi: 10.1177/0309132515624315.

- Desai, V. 2017. Black and minority ethnic (BME) student and staff in contemporary British geography. Area 49 (3):320–23. doi: 10.1111/area.12372.

- Ellefsen, R., and S. Sandberg. 2022. Black Lives Matter: The role of emotions in political engagement. Sociology 56 (6):1103–20. doi: 10.1177/00380385221081385.

- Elliott-Cooper, A. 2021. Black resistance to British policing. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

- Fanon, F. 1965. A dying colonialism. New York: Grove Press.

- Featherstone, D. 2012. Solidarity: Hidden histories and geographies of internationalism. London: Zed Books.

- Featherstone, D. 2013. Black internationalism, subaltern cosmopolitanism, and the spatial politics of antifacism. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 103 (6):1406–20. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2013.779551.

- Foley, G. 2011. Black power, land rights and academic history. Griffith Law Review 20 (3):608–18. doi: 10.1080/10383441.2011.10854712.

- Fuller, T., M. Herbert, and H. Davidson. 2018. “If you can talk, you can breathe”: The death in custody of David Dungay. The Guardian, April 11. Accessed April 30, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2018/apr/11/if-you-can-talk-you-can-breathe-the-death-in-.

- Gilroy, P. 1993. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and double consciousness. London: Verso.

- Glenn, E. N. 2015. Settler colonialism as structure: A framework for comparative studies of US race and gender formation. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 1 (1):52–72. doi: 10.1177/2332649214560440.

- Gowland, B. 2022. Narratives of resistance and decolonial futures in the politics of the Bermudian Black Power movement. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 46 (4):795–1021.

- Gregorie, P. 2014. A look back at the Australian Aboriginal rights movements of 2014. Vice. Accessed October 12, 2023. https://www.vice.com/en/article/exmwxp/the-year-in-australian-aboriginal-rights-movements.

- Hage, G. 1998. White nation: Fantasies of White supremacy in a multicultural society. Annandale, Australia: Pluto Press Australia.

- Harris, J. 2013. One blood: Two hundred years of aboriginal encounter with Christianity. Brentford Square, Australia: Australians Together.

- Hawthorne, C. 2019. Black matters are spatial matters: Black geographies for the twenty-first century. Geography Compass 13 (11):e12468. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12468.

- Henriques-Gomez, L., and E. Visontay. 2020. Australian Black Lives Matter protests: Tens of thousands demand end to Indigenous deaths in custody. The Guardian, June 6. Accessed October 21, 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/jun/06/australian-black-lives-matter-protests-tens-of-thousands-demand-end-to-indigenous-deaths-in-custody.

- Hill-Collins, P. 1990. Black feminist thought in the matrix of domination. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment 138:221–38.

- hooks, b. 1982. Ain’t I a woman? Black women and feminism. London: Pluto Press.

- Hope, J. K. 2019. This tree needs water! A case study on the radical potential of Afro-Asian solidarity in the era of Black Lives Matter. Amerasia Journal 45 (2):222–37. doi: 10.1080/00447471.2019.1684807.

- Jee-Lyn García, J., and M. Sharif. 2015. Black lives matter: A commentary on racism and public health. American Journal of Public Health 105 (8):e27–30. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302706.

- Johns, A. 2015. Battle for the flag. Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne University Publishing.

- Jordan, L. S. 2022. Unsettling the family sciences: Introducing settler colonial theory through a theoretical analysis of the family and racialized injustice. Journal of Family Theory & Review 14 (3):463–81. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12453.

- Joseph-Salisbury, R., L. Connelly, and P. Wangari-Jones. 2021. “The UK is not innocent”: Black Lives Matter, policing and abolition in the UK. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion 40 (1):21–28. doi: 10.1108/EDI-06-2020-0170.

- Justice Action. n.d. Death of David Dungay Jr. Accessed May 12, 2023. https://www.justiceaction.org.au/prisons/prison-issues/221-deaths-in-custody/980-death-of-david-dungay-jr.

- Kaiwar, V. 2014. The postcolonial Orient: The politics of difference and the project of provincialising Europe. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Kelly, D., and M. Lobo. 2017. Taking it to the street: Reclaiming Australia in the top end. Journal of Intercultural Studies 38 (3):365–80. doi: 10.1080/07256868.2017.1314256.

- King, T. L. 2019. The Black shoals: Offshore formations of Black and Native studies. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Köngeter, S. 2010. Transnationalism. Social Work & Society 8 (1):177–81.

- Korff, J. 2021. What is the correct term for Aboriginal people? Creative Spirits. Accessed June 4, 2023. https://www.creativespirits.info/aboriginalculture/people/howto-name-aboriginal-people.

- Leach, C. W., and A. M. Allen. 2017. The social psychology of the Black Lives Matter meme and movement. Current Directions in Psychological Science 26 (6):543–47. doi: 10.1177/0963721417719319.

- Leroy, J. 2016. Black history in occupied territory: On the entanglements of slavery and settler colonialism. Theory & Event 19 (4):1–10.

- Levitt, P., and N. Glick-Schiller. 2004. Conceptualizing simultaneity: A transnational social field perspective on society. International Migration Review 38 (3):1002–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2004.tb00227.x.

- McIntosh, P. 1989. White privilege: Unpacking the invisible knapsack. Peace and Freedom, July–August:10–12.

- McKittrick, K. 2006. Demonic grounds: Black women and the cartographies of struggle. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- McKittrick, K., and C. Woods, eds. 2007. Black geographies and the politics of place. Cambridge, MA: South End Press.

- Moreton-Robinson, A., ed. 2020. Sovereign subjects: Indigenous sovereignty matters. London and New York: Routledge.

- Moulton, A., and I. Salo. 2022. Black geographies and Black ecologies as insurgent ecocriticism. Environment and Society 13 (1):156–74. doi: 10.3167/ares.2022.130110.

- Mundine, K. 2021. Black Lives Matter and 30 long years since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. Human Rights Defender 30 (1):18–20.

- Nayak, A. 2007. Critical Whiteness studies. Sociology Compass 1 (2):737–55. [ doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2007.00045.x.

- Nayak, A. 2017. Purging the nation: Race, conviviality and embodied encounters in the lives of British Bangladeshi Muslim young women. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 42 (2):289–302. doi: 10.1111/tran.12168.

- Nayak, A. 2023. Decolonizing care: Hegemonic masculinity, caring masculinities and the material configurations of care. Men and Masculinity 26 (2):167–87.

- Noxolo, P. 2020. Introduction: Towards a Black British geography? Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 45 (3):509–11.

- Noxolo, P. 2022. Geographies of race and ethnicity 1: Black geographies. Progress in Human Geography 46 (5):1232–40. doi: 10.1177/03091325221085291.

- Osmond, G. 2011. The surfing Tommy Tanna: Performing race at the Australian beach. The Journal of Pacific History 46 (2):177–95. doi: 10.1080/00223344.2011.607263.

- Pence, K., and A. Zimmerman. 2012. Transnationalism. German Studies Review 35 (3):495–500. doi: 10.1353/gsr.2012.a488485.

- Perheentupa, J. 2021. Aboriginal housing company and The Block. Redfern Oral History. Accessed March 29, 2023. http://redfernoralhistory.org/Organisations/AboriginalHousingCompany/tabid/209/Default.aspx.

- Phillip, A. 2015. The voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay, digital ed. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Pickerill, J. 2009. Finding common ground? Spaces of dialogue and the negotiation of Indigenous interests in environmental campaigns in Australia. Geoforum 40 (1):66–79. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2008.06.009.

- Pollock, Z. 2008. Aboriginal housing company. Dictionary of Sydney. Accessed October 5, 2022. https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/aboriginal_housing_company.

- Porter, A. 2023. Quantifying an Australian crisis: Black deaths in custody. Pursuit. Accessed June 21, 2023. https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/quantifying-an-australian-crisis-black-deaths-in-custody.

- Pulido, L. 2002. Reflections on a White discipline. The Professional Geographer 54 (1):42–49. doi: 10.1111/0033-0124.00313.

- Pulido, L. 2017. Geographies of race and ethnicity II: Environmental racism, racial capitalism and state-sanctioned violence. Progress in Human Geography 41 (4):524–33. doi: 10.1177/0309132516646495.

- Quanchi, M. 1998. Lobbying, ethnicity and marginal voices: The Australian South Sea Islanders call for recognition. History Teacher 36 (1):31–41.

- Quijano, A. 2000. Coloniality of power, Eurocentrism and Latin America. Nepantla 1 (3):533–80.

- Radcliffe, C. 2017. The sustainable agriculture learning framework: An extension approach for indigenous farmers. Rural Extension and Innovation Systems Journal 13 (2):41–51.

- Roediger, D. 1992. The wages of Whiteness: Race and the making of the American working class. London: Verso.

- Roediger, D. 1994. Towards the abolition of Whiteness. London: Verso.

- Said, E. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon.

- Shahin, S., J. Nakahara, and M. Sánchez. 2024. Black Lives Matter goes global: Connective action meets cultural hybridity in Brazil, India, and Japan. New Media & Society 26 (1):216–35. doi: 10.1177/14614448211057106.

- Shaw, W. 2007. Cities of whiteness. London: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Shilliam, R. 2015. The Black Pacific: Anti-colonial struggles and oceanic connections. London: Bloomsbury.

- Singh, M. 2020. George Floyd told officers “I can’t breathe” more than 20 times, transcripts show. The Guardian, July 8. Accessed March 1, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/jul/08/george-floyd-police-killing-transcript-i-cant-breathe.

- Spencer, R. C. 2017. The language of the unheard—Black Panthers, Black lives, and urban rebellions. Labor 14 (4):21–24. doi: 10.1215/15476715-4209314.

- Tuck, E., and K. W. Yang. 2012. Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization Indigeneity, Education & Society 1 (1):1–40.

- Vertovec, S. 1999. Conceiving and researching transnationalism. Ethnic and Racial Studies 22 (2):447–62. doi: 10.1080/014198799329558.

- Vertovec, S. 2004. Migrant transnationalism and modes of transformation. International Migration Review 38 (3):970–1001. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2004.tb00226.x.

- Watego, C. 2021. Always bet on black (power): The fight against race. Meanjin 80 (3):22–33.

- Wilson, E. 1856. In One blood: Two hundred years of aboriginal encounter with Christianity, ed. J. Harris, 209. Brentford Square, Australia: Australians Together.

- Wolfe, P. 1999. Settler colonialism and the transformation of anthropology: The politics and poetics of an ethnographic event. London: Cassel.

- Wood, A. 2023. Bringing transport into Black geographies: Policies, protests, and planning in Johannesburg. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 113 (4):1020–33. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2022.2151407.

- World Population Review. 2022. Sydney population 2022. World Population Review. Accessed July 5, 2023. https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/sydney-population.