Abstract

Few Internet governance issues raised a similar level of public alertness, as it has been the case with network neutrality. Advocates in favour of strict rules feared the end of the Internet itself, while access providers fought against interferences in their business areas. The regulatory process in the European Union was multi-faceted and faced several key changes and turning points. This paper examines the positions at stake from the emergence of the network neutrality debate in 2009 during the amendment of the Telecom Single Market Directive to its aftermath in 2019. Focussing on the implications for public and private online communication, a normative and social value framework provides us with the basis for interpreting key developments. The methodological setting is a multi-method-design consisting of a comprehensive literature review, a document analysis as well as expert interviews with involved stakeholders. The results shed light on the importance of the EU Internet market, its characteristics and challenges and allow to draw a comprehensive image of the European Union’s performance in regulating network neutrality. Albeit the complex institutional setting slowed down the process, the outcome is characterized by the inclusion of multiple stakeholders and the possibility to adapt legal norms on a dynamic basis.

Introduction

The Internet is an indispensable communication resource and a central network for maintaining the nervous system of the network society (Castells, Citation2005; Castells & Cardoso, Citation2016; van Dijk, Citation2012). According to Manuel Castells, “networks constitute the new social morphology of our societies, and the diffusion of networking logic substantially modifies the operation and outcomes in processes of production, experience, power and culture” (Castells, Citation2005, p. 500). Therefore, the Internet as the “network of the networks” has emerged as a key institution in modern societies when it comes to public and individual information and communication needs.

Public policy and Internet governance have to maintain the balance between being an enabling and empowering institution on the one side and fulfilling explicit normative and social values (and duties) on the other side. Network neutrality is currently probably one of the most important issues (Mailland, Citation2018) and the debate surrounding it is key to adapt and redefine rights and obligations of stakeholders in the Internet-centric communications system (Bauer & Obar, Citation2014). In his conclusion on policy perspectives for the network society, Jan van Dijk (Citation2012, p. 290f.) defined several social values. At least two of them are central to the network neutrality debate. If networks are supposed to be the nervous system of societies, access to networks is one of their most vital characteristics. Restricted or marginal access simply means exclusion. Another crucial characteristic that shapes the rate of online engagement is freedom of expression (Benedek & Kettemann, Citation2013), which determines “the boundaries of our freedom to speak, innovate and participate in public and democratic life online” (Mailland, Citation2018, p. 1)

The outline of this paper is to characterise the main policy issues and milestones regarding network neutrality in the European Union from 2009 to 2019. As “network neutrality has come to serve as an all-embracing term for policy matters relating to Internet regulation” (Mansell, Citation2012, p. 167), this needs further specification. There are several reasons why this research focus may contribute to the academic discourse: (1) there is a good amount of literature that considers the network neutrality debate to remain largely US-centric (e.g. Le Crosnier & Schafer, Citation2011; Mailland, Citation2018; Musiani et al., Citation2012; Vogelsang, Citation2010). Although the Internet is global in terms of architecture and design, it is also de-centralised and specific geographical differences have not been analysed adequately from an empirical perspective. (2) The term “network neutrality” entered the academic discourse mainly thanks to the seminal paper “Network Neutrality, Broadband Discrimination” by then University of Virginia law professor Tim Wu (Wu, Citation2003). Despite his profound analysis and his efforts to put the debate both in the academic and public spotlight, key elements of the network neutrality concept were already discussed at least two decades before. One example is the French case on Minitel between the years 1979 and 1982 (Mailland, Citation2018, p. 2). (3) The policy process is highly complex and involves multi-faceted interests of stakeholders. For this purpose, diachronic timeline analysis helps to show the dynamics and power relations within this process. The timeline analysis as a methodological approach includes a literature review, a qualitative document analysis and expert interviews. The analysis is targeted to fill a gap in research, which Des Freedman (Citation2014, p. 70) described as media policy silences.

For these reasons, this paper tries to widen the scope and implications of policy measures with regards to the EU’s policy process of establishing network neutrality regulation. This paper’s results may inform scholars, policymakers and future regulatory policies about the implications for normative standards and values in public and private communication. It provides results on the dynamics of the policy-making and decision-making process. However, this paper also adds insights into the historical perspective as the discussion on network neutrality is exactly how Marsden (Citation2017, p. 17) puts it: “Network Neutrality is the latest phase of an eternal argument over control of communications media.”

Network neutrality – historical context and definition

Since the first attempts to establish a networked communication infrastructure, “... cyberspace is, indeed, a series of tubes, whomever controls these tubes has the physical power to control the data that flows through them” (Mailland, Citation2018, p. 4). Therefore, a good starting point of the network neutrality debate might be traced in the rise of the first technical Internet-like versions even before it was clear which one(s) of them would succeed. To get back to core principles of (globally) networked communication, one has to recall the early days of the technical implementation of today’s Internet, when broad proprietary communication networks (e.g. AOL, CompuServe, Prodigy) set up walled-garden-services. Each company tried to prevail over the others and become the dominant player (Zittrain, Citation2008). However, “they were crushed by a network built by government researchers and computer scientists who had no CEO, no master business plan, no paying subscribers, no investments in content, and no financial interest in accumulating subscribers” (Zittrain, Citation2008, p. 7). One of these pioneers is the inventor of the World Wide Web, Tim Berners-Lee, who worked at CERN (the European Organization for Nuclear Research) in Geneva and developed the communication system most of us are using on a daily basis. In a guest blog for EU-Commission Vice-President Andrus Ansip’s official webpage,1 Berners-Lee highlighted some of his concerns regarding online communication. He argued that openness is a key element that underpins the Internet and that is under threat because of techniques and strategies departing from the principle that every data ‘packet’ should be treated equally (‘end-to-end-principle’) (Berners-Lee, Citation2015).

So, when we talk about the vast potential of the Internet for innovation (e.g. Gershon, Citation2016), inclusion and benefits to society as a whole (e.g. Schroeder, Citation2019; van Dijk, Citation2012), the critical questions about openness and accessibility persist since the early days of technical implementation. Powerful actors like Internet service providers (ISPs) as well as governments and states could interfere in the (initially neutrally designed) Internet traffic processing. Therefore, there is a risk that commercially driven private interests or surveillance requests by states could dominate and discriminate public as well as private online communication. We should therefore clarifiy the key elements and concepts in the net neutrality debate and the context to frame it.

At the beginning, almost every definition of net neutrality begins vague (Rogerson et al., Citation2017, p. 18). As already mentioned, the term was brought into the academic discourse in an US-centric context around 2000–2003 by scholars like Lawrence Lessig (Citation1999) and Tim Wu (Citation2003). In brief, the concept of network neutrality can be understood as a network design principle. In such a network, every kind of content or data is treated equally and is transported from one sending end to a receiving end at best effort without discriminative interference. The publication of the Wu’s paper was parallel to the emerging debate on (potential) Open Internet regulation needs in the United States. In 2006, Lessig and McChesney (Citation2006) argued, ahead of the first US-Congressional vote, that

[…] all like Internet content must be treated alike and move at the same speed over the network. The owners of the Internet’s wires cannot discriminate. This is the simple but brilliant ‘end-to-end’ design of the Internet that has made it such a powerful force for economic and social good: All of the intelligence and control is held by procedures and users, not the networks that connect them. (Lessig & McChesney, Citation2006)

Accordingly, one core aspect of network neutrality is the equal treatment of each data packet and non-interference in its transportation. Network operators and network owners are considered to be neutral carriers. However, while the Internet evolved, online communication has required a certain kind of traffic management in order to avoid or minimize congestion. A balance has therefore to be found between ‘reasonable’ traffic management and the principles of network neutrality (Curran, Citation2009; Curran et al., Citation2009; Fidler, Citation2019; van Schewick, Citation2016).

Another definition by Hahn and Wallsten (Citation2006) adds another aspect to the concept of network neutrality.

Net neutrality has no widely accepted precise definition, but usually means that broadband service providers charge consumers only once for Internet access, do not favour one content provider over another, and do not charge content providers for sending information over broadband lines to end users. (Hahn & Wallsten, Citation2006)

Pricing and charging for services and the technical possibility to charge for a ‘communication services portfolio’ either on the content application provider’s (CAPs) side or on the end user’s side appeared as a substantial and new source of income for ISPs. The issue of pricing and service fees then remains on the policy agenda under the terms specialized services, fast lanes or zero-rating (Belli, Citation2016; DotEcon, Aetha Consulting, & Oswell &Vahida, 2017; Layton & Elaluf-Calderwood, Citation2015).

As already mentioned, the debate on network neutrality was predominantly sparked in the US. Albeit of equal importance to other Internet or broadband markets; this discussion gained momentum a little later on. The European Union took up the debate in 2009. It was in the context of the amendment of the EU telecommunications framework and the search for a policy approach in the Framework Directive2. The purpose of this approach has been “promoting the ability of end-users to access and distribute information or run application and services of their choice.”3 Additionally to the amendment of the Framework Directive, the European Commission published a declaration: “The Commission attaches high importance to preserving the open and neutral character of the Internet, taking full account of the will of the co-legislators now to enshrine net neutrality as a policy objective and regulatory principle […].”4

The debate gained momentum especially with the European Union’s desire to create a Connected Continent,5 with a strong and competitive Digital Single Market. This claimed for a critical study of network neutrality. Non-discrimination and neutral transportation of data is therefore at the heart of the debate, but as Krämer et al. (Citation2013, p. 795) put it, “[…] this historic and romantic view of the Internet neglects that Quality of Service (QoS) has always been an issue for the network of networks.” Quality of Service may mean, that there is a need for a certain type of hierarchy for transmission. For mere text messages the transmission affordances may be quite low, whereas voice communication, communication for artificial intelligence (e.g. autonomous driving) or similar purposes require reliable transmission. Accordingly, the theoretical definition of network neutrality do not match practical affordances (Wu & Yoo, Citation2007; Yoo, Citation2012) – a dilemma that still demands for a policy or regulatory answer.

Krämer et al. (Citation2013, pp. 796–797) propose two definitions of network neutrality in order to get a view for the sensitive regulatory issues at stake. They call the first one strict net neutrality, meaning that ISPs are prohibited from speeding up, slowing down or blocking Internet traffic based on its source ownership or destination. For the second one, the authors are relying on the definition of Hahn and Wallsten (Citation2006), picking up the aspect of extra charging for extra services. This is a derivative of the original concept of network neutrality and probably the most controversial issue of the still ongoing debate (Krämer et al., Citation2013, p. 798)

Methodological approach and research focus

Network neutrality is a multi-disciplinary issue, covered by scholars from engineering/computer science, social sciences, law studies and economics. Although the latter two might be the most prominent disciplines – at least in the initial phase when the discussion popped up (Löblich & Musiani, Citation2014, p. 339f), the issue of net neutrality became increasingly lively in communication research (see e.g. Cooper, Citation2014; Krone & Pellegrini, Citation2012; Powell & Cooper, Citation2011; Vogelsang, Citation2010).

Although (law professor) Yoo (Citation2012) imputes a lack of knowledge on how the Internet technically works to communication scholars, communication research has already a long tradition in addressing and enlightening concepts like freedom of expression (Benedek & Kettemann, Citation2013; Musiani & Löblich, Citation2016), diversity of ownership (Meese, Citation2019), together with democratic values (Christians et al., Citation2009; Trappel & Maniglio, Citation2011) and accessibility/universality (Batura, Citation2016). However, further communication research for these concepts, especially for communication policy research, as “[…] it is a policy area involved in what is at the heart of contemporary society: information, news and cultural production, meaning creation and content curation and the distribution of content and services to individuals” (Puppis & Van den Bulck, Citation2019, p. 3f), is needed.

This paper uses an exploratory methodological approach, which allocates basic milestones and dynamic developments in a timeline analysis. The timeline is constructed as a sequence model in order to analyse policy steps (Lasswell, Citation1956) and is complemented by discussing stakeholder interests, normative values and ideas in a societal context (de Sola Pool, Citation1974, Citation1983). While policy processes are quite complex and sometimes opaque (Freedman, Citation2008, Citation2014), the methodological setting has to be suitable to characterize the obvious policy outcomes (e.g. laws) on the one hand as well as the hidden ‘grey’ areas (e.g. lobbying) on the other hand.

The following analysis is based on a multi-method-design relying firstly on existing literature. This is what Meier (Citation2019) describes as meta-analysis. Following his suggestion of a “meta-analytical literature review” (p. 104), relevant literature and (empirical) studies provide the basis for approaching the research question and underlying assumptions. In a similar way, Braman (Citation2019) describes a certain type of ignorance that should be avoided by researchers. When approaching a communication policy problem “it is tempting to assume that nothing we know from before pertains. Not so.” (p. 657). For the case of network neutrality both scholars are right. Despite the ongoing process, there is already a solid basis of scientific output. However, this basis decreases when focussing geographically on the European Union, and chronologically on the amendment of the Telecom Single Market-Directive (TSM-Directive)6 and its aftermath.

To gather reliable and meaningful primary data, two methods, which are very common for analysing policy processes, are applied. The first one is a document analysis (Karppinen & Moe, Citation2012, Citation2019) focussing on policy documents from official sources (e.g. laws/directives/regulations), publications of regulatory authorities (national regulatory authorities – NRAs, BEREC), industry documents (e.g. ISPs) and publications from particular interest groups (e.g. civil society organisations, like SaveTheInternet). The document analysis allows the identification and characterization of the basic policy process milestones, of the relevant stakeholders involved and of their respective positioning. The following table provides an overview of the documents we used:

Whereas policy documents mainly represent outcomes of a policy process and rather neglect the ‘grey’ area of power structures, lobbying activities and informal negotiations, this shortcoming is complemented by expert/elite interviews (Van Audenhove & Donders, Citation2019). The document analysis has been the starting point for the interviews in order to sequentially identify stakeholder groups, institutions/organizations, and players to be interviewed. During the year 2019, 14 interviews within four different stakeholder categories have been conducted (code in very right column was used for quoting in the following analysis).

Timeline analysis the network neutrality communication policy process in the European Union

The debate on network neutrality is ongoing from the early implementation days of technical Internet infrastructure. Re-vitalised in the US context at the turn of the millennium it took momentum on a global scale afterwards. First, the issues at stake relate to the technical level, followed by legal and economic arguments regarding innovation and competition. For Europe, the debate popped up later on (starting around 2005) when network operators started to explore increased commercial opportunities when partitioning the Internet into more controlled private domains. Brown and Marsden (Citation2013, p. 139f) described these developments as “smart pipes”. ISPs deploy sophisticated traffic management and routing tools (e.g. deep packet inspection – DPI), begin to prioritize certain content over another or block/throttle data flows. This signalled a kind of paradigm shift in Internet architecture? As Mansell (Citation2011, p. 19) underlined it, “the Internet is no more a neutral configuration of technologies than was the earlier media and communication system.” These practices started to raise attention at the regulatory EU level in 2007 when a new Telecom Framework was discussed. Accordingly, in this paper the beginning of the network neutrality communication policy is set in parallel with this date.

Rinas (Citation2019, p. 236) has already strongly describe the stages of this policy process. He identifies three phases. The first one covers the years 2007–2009, when the telecom framework was under review. After this phase, a second period from 2010 to 2013 followed, when EU institutions intensively evaluated current practices and behaviour of market players and users. Finally, Rinas identifies a third phase, when the debate on network neutrality flared up again, leading to the TSM-Directive in 2015 and the BEREC guidelines in 2016.

shows a similar development and is based upon this classification. However, with respect to a slightly different theoretical perspective, the boundaries of these phases may also vary. The timeline starts with the amendment of reviewed telecom framework and a parallel EU Commission declaration in 2009. It ends with the evaluation report of the TSM-Directive (Bird & Bird and Ecorys, 2019) in 2019. The stages in between are described in the following chapters.

3 Main phases – network neutrality milestones

The regulatory debate on Open Internet and network neutrality covered at least ten years and is still going on as the latest public consultation on the renewal of BEREC’s guidelines was held in autumn 2019. Several milestones can be identified.

Phase 1 “detecting problems & raising awareness”: 2009–2013

The freshly amended telecom framework package further paved the way for the opening of markets and the cultivation of competition therein. This package updated already existing regulation from 2002 and addressed especially issues like service provision, access, interconnection, user rights and privacy. However, facing the economic crisis, the EU saw very high-speed broadband or next generation networks (NGN) as a major opportunity and a driver of economic and social progress (Simpson, Citation2012, p. 337). The aim was a harmonized and globally competitive telecom market, enabled by the highly ambitious Digital Agenda for Europe7, which was published in May 2010. One of the pillars of this vision was increased and fair accessibility to digital communication services, both for users and for the industry. At this time, the Internet has become much “more about content than communication” (Tanenbaum & Wetherall, Citation2011, p. 734), meaning that telecommunication networks faced pressure from increased over-the-top (OTT) services on the one hand and a decrease in classic communication (and revenue) services like SMS and phone calls on the other hand (REG2; IND2). Therefore, ISPs had to think about potential new income. In order to overcome the new challenges, they envisioned to use their powerful position of owning the networks and move from a neutral intermediaries and carriers to indispensable gatekeepers.

In 2010, the Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications (BEREC, a network of national regulatory authorities, NRAs) started its activities. One of its first tasks was the assessment of differentiation practices and competition issues within the scope of network neutrality (BEREC, Citation2012a, Citation2012b). The final reports showed practices like blocking and throttling of data flows and prioritizing some services over others (mostly the own services provided by vertically integrated providers). In general, the period from 2009 to 2013 investigated and evaluated prevailing practices in the telecom sector (GOV2). BEREC was of course one of the institutions producing related reports on that matter.

European regulators also had to face a regulatory action in the US market and three national solo runs for pushing forward network neutrality regulation (REG4; REG5). In 2010, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which is the US regulatory authority, published the Open Internet Order to introduce rules on reasonable traffic management and specialized services. In Europe, a co-regulatory agreement for network neutrality was signed in Norway in 2009 (REG2). National laws for network neutrality were implemented in the Netherlands and in Slovenia (both in 2012; Van Daalen (Citation2012). Therefore, there was a need for action and a call for harmonized norms within the EU digital market. The EU commission answered this call with a regulation proposal achieving a “Connected Continent.”8 This proposal consisted of several policy measures for the European Internet market. As will be shown in phase 2, only two of them entered the trialogue negotiations. Regarding network neutrality, the responsible and initiating commissioner Neelie Kroes did not see a pressing issue at the time she held a speech at the ARCEP Conference in Paris in April 2010: “So, I will not be someone who comes up with a solution first and then looks for a problem to attach it to. I am not a police officer in search of a busy corner.” (Kroes, Citation2010, p. 4)

Phase 2 “hands-on regulatory solutions”: 2013 to 2015

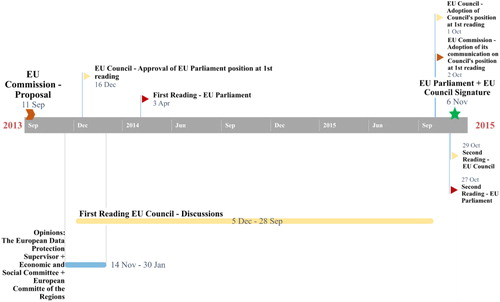

Problems regarding the Internet market in the EU had been identified and BEREC published a great deal of information, mainly related to techno-economic aspects (Marsden, Citation2017, p. 95). These problems were manifold and they were addressed in the Commission’s Connected Continent proposal. The ball then was in the Parliament’s and Council’s court. However, the proposal with its complex and multi-faceted policy issues had from the beginning a very limited chance to be ratified and enshrined into law (GOV1; GOV4; CIV1). One of the reasons at this time was the upcoming European Parliament election in 2014. Commissioner Kroes faced pressure to push through her political plans related to the Digital Agenda before the election (GOV3; CIV1). Therefore, the Connected Continent proposal was formulated very broad and also vague – at this stage it was very unlikely that the full proposal would reach a consensus in Parliament and Council (GOV4). Additionally, some of the policy issues in the proposals were ‘hot potatoes’, at least for some member states (e.g. spectrum policy; GOV5). shows a timeline beginning with the Commission’s proposal in 2013, proceeding with the trialogue negotiations, and ending with the TSM-Directive in 2015.

Figure 2. Development of the Telecom Single Market (TSM) Directive. Procedure 2013/0309/COD. Own illustration, based on EUR-Lex. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/procedure/EN/1041202.

In its initial proposal, the Connected Continent regulation proposed solutions for harmonising network neutrality in the EU, while also allowing priority to specialised services and services potentially interesting for commercial purposes (“fast lanes”). This was bad news for end-users and Internet activists (CIV1; CIV2). In parallel, the proposal also included a general ban preventing ISPs from blocking or throttling third-party content. So far so good – the proposed regulation started into the process with positive as well as negative parts for network neutrality policy (GOV4).

The chances for success were very limited from the beginning (GOV3; GOV4; IND2). Considering the legislative process in the EU, Parliament and Council are co-legislators and a compromise between the two and the Commission is necessary. The Commission’s proposal included too many sensitive policy issues for member states (GOV1; REG3) and also threats to citizens’ rights (CIV1; CIV2), so Parliament, Council and BEREC trashed the Commission’s proposal in its full aspects. This was kind of a political obituary for outgoing Commissioner Kroes (Marsden, Citation2017, p. 98). What remained for further negotiations by the end of 2014 was mobile roaming (“the populist element”) and Open Internet/network neutrality (REG1; IND2; CIV1). In its First Reading, Parliament amended a very strong position on network neutrality policy, which the Committee on Industry, Research and Energy (ITRE) even accentuated (GOV4). One reason for the strong Parliament position might have been high engagement by civil society organisations and accordingly high public alertness (CIV1). This phenomenon was not solely observable in Europe but also in the US ahead of Open Internet Order 2015 (Kirkpatrick, Citation2016) and in India when network neutrality advocates defeated Facebook’s Free basics (Prasad, Citation2018).

Accordingly, the challenges for network neutrality regulation started again. The representing member states were split into two camps (GOV4; GOV5). The first one was quite in favour of the Parliament’s amendments, mostly because the proposed measures would suit very well to their respective national Internet markets and framework. As there were already dedicated laws in the Netherlands and in Slovenia, these countries were opinion leaders in the camp advocating strict network neutrality rules, which would be directly applicable to their national laws (REG4; REG5). The second camp consisted of member states where the telecom sector has a strong lobby and where these states hold majority stakes in the national incumbent telecom operators (GOV1). The bargaining power between those two camps was rather balanced at the time of Council’s first reading and a compromise was far ahead.

The decisive turning point and the key change in the Council’s position might have been Germany’s change of position in early 2015, prior to the Second Reading in Council (Marsden, Citation2017, p. 99). Germany’s initial position on favouring a pro-network-neutrality-approach was advocated by the national public service broadcasters who feared to lose ground in providing content on online channels compared to over-the-top-players (OTTs) and vertically integrated ISPs (GOV4). Lobbying activities led by the industry (see e.g. Höttges, Citation2015) and the appointment of the conservative Commissioner for digital affairs marked a turning point in the German position (CIV1). The change became even more obvious because of Commissioner Oettinger’s statement (Germany) on 5 March 2015. He argued against strong network neutrality rules by stating:

“Net neutrality: Here we’ve got, particularly in Germany, Taliban-like developments. We have the Internet community, the Pirates on the move, it’s all about enforcing perfect uniformity. […] If you want to have real time road safety, our lives are at stake, this has to have absolute priority with regards to quality and capacity.” (EU Commissioner Günther Oettinger, taken from Beckedahl, Citation2015, translated by the author)

The weak balance between both sides was damaged and a majority of member states now favoured soft network neutrality regulation, including specialised services and fast lanes (REG1; GOV1). In the 4th trialogue at the end of June/beginning of July 2015 a preliminary compromise was reached9. After adding some recitals and after the approvals by the Committee of Permanent Representatives (COREPER) and other Committees, Council adopted the trialogue agreement at the beginning of October 2015. Then Parliament voted down amendments for strong network neutrality and confirmed the Council text at the end of October 2015. The new regulation was published in the official journal on 25 November 201510.

What remained in the compromised text was the avoidance of the term network neutrality; the regulation instead uses Open Internet. The main provisions can be found in Articles 3-6. Equal traffic treatment as the basic principle of network neutrality is stipulated in Article 3(3). The highly disputed exception to this principle – the specialised service allowance – follows shortly after in Article 3(5). Article 4 defines transparency duties for ISPs to their customers, thereby facilitating consumer protection. Monitoring, supervision and enforcement are assigned to the national regulatory agencies (NRAs) in Article 5(1). A vaguely defined quality of service (QoS) measure follows in Article 5(2) and penalties for any kind of misbehaviour I the responsibility of the NRAs competencies. An important task is imposed to BEREC in Article 5(3):

By 30 August 2016, in order to contribute to the consistent application of this Regulation, BEREC shall, after consulting stakeholders and in close cooperation with the Commission, issue guidelines for the implementation of the obligations of national regulatory authorities under this Article.

The long way to find a minimum compromise in the trialogue negotiations is reflected in the final text of the regulation. It is vague and crucial elements remain unclear (GOV3; CIV1; REG1). However, the equal treatment provision is included. From a normative public-interest perspective, this can be interpreted as a desirable outcome on the one hand. On the other hand, there is much of a leeway for paid prioritisation and specialised services potentially leading to a “privileged classes” Internet (Lehofer, Citation2015). At the time of its publication, the measures within the TSM-Directive were controversial, its effects on the Internet market(s) vague and much of interpretation for practical application was still remaining (REG5; REG2; CIV2).

Phase 3 “buck-passing the issue”: 2015 to 2019

The TSM-Directive was passed at the end of 2015 and entered into force on 30 April 2016. At this time, one actor at the European level was in the spotlight – BEREC. This regulatory body, consisting of the NRAs of the member states, was confronted with the difficult task of providing a stakeholder forum and of removing ambiguity in applying the TSM-Directive (REG1). The EU legislative institutions made a vague diagnosis and pointed towards a general treatment, whereas BEREC and Internet stakeholders had to swallow the pill (GOV1).

The process of drafting guidelines started with a first stakeholder hearing on 15 December 2015, not even 9 months ahead of the deadline for publication, which was scheduled on 30 August 2016. This was a time of intensive stakeholder interaction and lobbying activities (IND2; CIV1). Several working groups have been involved, mainly of course the Network Neutrality Working Group (NNWG) headed by a representative from NKom (Norway) and Ofcom (UK). These working groups drafted guidelines until June 2016, when there were plenary votes on the drafts, followed by a 20 days period for public consultation. The Commission acknowledged in a press statement that “Europe’s regulators have a long track record in safeguarding open, competitive markets, and the Commission will work closely with the Body of European Regulators of Electronic Communications (BEREC) to ensure that clear guidance is rapidly provided in this field to complement the Regulation itself.”11 BEREC finally delivered in time.

Four topics have been of specific interest: (1) traffic management practices, (2) specialised services, (3) transparency in Internet access quality and (4) commercial practices. On traffic management practices, the Guidelines “clearly provide strict limitations on the provision of specialised services with different price/quality characteristics from standard internet access services.” (Rogerson et al., Citation2017, p. 33). Nevertheless, there was room for service differentiation to be further interpreted by the NRAs. For specialised services, nothing is set in stone and subject to dynamic and changing service requirements. This leaves ISPs as well as content providers with uncertainty (IND1; REG3). The same is true for commercial practices like zero-rating. Following the evaluation report of the TSM-Directive (Bird & Bird, & Ecorys, 2019), no severe violations of network neutrality have occurred. However, ISPs are piloting new contracts and tariffs to check how far they can go and to what degree their behaviour is tolerated by the responsible NRA.

The supervision of network neutrality by BEREC and the NRAs is a working compromise but is still open for further lobbying battles between industry and civil society advocates (IND1; IND2; CIV1). On the one hand, BEREC is a well-networked regulatory body including expert knowledge in several areas. In addition, a network neutrality measurement tool was tendered (REG3) and then contracted in summer 2018.12 On the other hand, the Guidelines are soft law and despite sophisticated organisational structures within BEREC, they bear the risk of being changed in favour of particular interests on a low threshold basis (REG1).

Discussion network neutrality from a regulatory theory perspective and related policy streams

The need for regulatory intervention to promote network neutrality policies in the EU Internet market might be denied by only a few stakeholders meanwhile (IND2; GOV1). Harmonisation of a comprehensive European market and improvement of competition have been the first pro-arguments in the initial phase (GOV2). They were followed by economic arguments that stated that without regulatory interference commercial practices would stifle the innovative potential of a ‘neutral end-to-end best effort model’ (Gans, Citation2015). Communication policy goals are related to freedom of expression and access universality. These goals were addressed by the Connected Continent proposal and followed by provisions within the TSM-Directive later on. The equal treatment of Internet traffic and the ban on discrimination because of commercial interests are good achievements for fostering freedom of expression (REG2; GOV4). Regarding universal service and broadband connectivity, almost every EU citizen has access to a broadband connection. According to the latest Digital Economy and Society Index Report, 97% of EU households are covered with fixed broadband (DESI, 2019). However, a well-established infrastructure and the way traffic is managed are two different aspects when it comes to specialised services and practices like zero-rating (CIV1). The normative goal of universality therefore is constrained.

It is constrained because of favourable rulings for ISPs therefore strengthening their power position. These circumstances have already a long tradition in telecommunication policy research. Laffont and Tirole (Citation1991) characterized this phenomenon as regulatory capture: (1) Actors with significantly higher lobbying resources can influence the regulatory process (and institutions in charge) better than actors who have less resources available. (2) This widens the gap between the two sides and stronger interest groups gain more power from less efficient than efficient regulation. Within that context, BEREC is mainly the institution that needs to be addressed (GOV3). Given its organizational structure of evidence-based and practically-oriented workflows in the expert groups and follow-up votes in contact network and plenary meetings, an ‘unreasonable’ policy proposal is unlikely to be passed (REG2). For the second aspect, NRAs have to be scrutinised, as they are the institutions executing the TSM-Directive (GOV5). Different NRAs might apply a different scope of interpretation in their national competencies. This bears the risk of a fragmented EU Internet market with different national regulatory settings.

The idea to integrate a dynamic and responsive element in an EU Directive, as it has been the case with the TSM-Directive and the stipulated follow-up Guidelines, indicated a new approach to regulate the converging Internet sector. This could be a potential window of opportunity for interest groups with lower resources available. Civil society organisations advocated for clear provisions on free and universally accessible online communication (the principle of strict network neutrality). Potential issues were integrated or dropped, depending on the involved stakeholders’ lobbying powers. Whenever there is a chance to react to changing moods or swings on a regional, national or international level, this discussion can again lead to windows of opportunities. This was the case for the Dutch national network neutrality law and could potentially also become a reality for the EU Internet market.

Conclusion the network neutrality communications process and its implications

In these debates about governance of the Internet (and media and the communication system generally), it seems that one group of stakeholders must lose in order for another to win in the battle over network neutrality. (Mansell, Citation2012, p. 173)

For the policy process on network neutrality in the EU this quote turned out to be very appropriate. The process was about finding a minimum compromise or facing a potential regulatory problem without any substantial regulatory measures. It also became obvious that a fully harmonized EU Internet market was far from reality. National telecom markets still play an important role and so do member states in representing these national characteristics on the EU political level. For political processes, different perspectives may be adopted when considering whether outcomes can be characterized as good or bad politics. Similarly, there are different forms of success (McConnell, Citation2010). EU citizens will have to cope with the fact that they have the right to communicate online equally and without unjustified discrimination – except for the exceptions to this rule. Granting the industry and ISPs the right to offer specialised services and prioritised fast lanes was the compromise, in order to reach a regulatory compromise and an EU agreement on network neutrality. Albeit this is just an EU version of network neutrality “light”. However, the policy process is still going on and marginalized interest groups like civil society organisations might discover new windows of opportunity. The network neutrality communications process in the EU showed that albeit powerful interest groups with high lobbying potential and activity may not necessarily succeed in every aspect. For network neutrality, as the latest phase of an eternal argument over control of communications media (Marsden, Citation2017), there is a need to consider normative and social values in order to further promote the Internet as a key technology within the networked society.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

Notes

1 The blog of former VP Andrus Ansip is offline meanwhile. A short version of Tim Berners-Lee’s guest blog is available here: https://webfoundation.org/2015/02/sir-tim-berners-lee-net-neutrality-is-critical-for-europes-future/ (2019-12-19).

2 EU-Directives are directly applicable in the member states and are comparable to the legal effects of national law (Savin, Citation2018; Schmidt & Schünemann, Citation2013;). The ‘Framework Directive‘provides the legal basis for electronic communications networks and services.

3 Directive 2009/140/EC of 25 November 2009 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32009L0140&from=En

4 Commission declaration on net neutrality (2009/C 308/02) https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri = CELEX:C2009/308/02&from = EN

5 Proposal 2013/0309 (COD) https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri = CELEX:52013PC0627&from = EN

6 Regulation (EU) 2015/2120 of 25 November 2015 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri = CELEX:32015R2120&from = EN

7 Shaping the Digital Single Market https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/policies/shaping-digital-single-market

8 Proposal 2013/0309 (COD) https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri = CELEX:52013PC0627&from = EN

For the normal procedure to create or amend law, the EU Commission delivers a proposal which then has to be decided upon by the Council and the Parliament (Schmidt & Schünemann, Citation2013, p. 209). The Connected Continent proposal has been such a proposal.

9 For a detailed overview of the trilogue process see the European Digital Rights (EDRi) Network Neutrality: document pool II https://edri.org/net-neutrality-document-pool-2/

10 Regulation (EU) 2015/2120 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri = CELEX:32015R2120&from = DE

11 Q&A Roaming charges and open Internet, Memo by the EU Commission (2015-06-30) https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_15_5275

12 Net Neutrality Measurement Tool – Result of the tender, BEREC press release (2018-08-08). https://berec.europa.eu/eng/news_and_publications/whats_new/5045-net-neutrality-measurement-tool-result-of-the-tender

References

- Batura, O. (2016). Access to the network as a universal service concept for the European Information Society. In S. Simpson, M. Puppis & H. Van den Bulck (Eds.), European media policy for the twenty-first century. Assessing the past, setting agendas for the future (pp. 175–192). Routledge.

- Bauer, J. M., & Obar, J. A. (2014). Reconciling political and economic goals in the net neutrality debate. The Information Society, 30(1), 1–19. doi:10.1080/01972243.2013.856362

- Beckedahl, M. (2015, March 06). Günther Oettinger: Netzneutralität tötet, Befürworter sind Taliban-artig. Netzpolitik.org. https://netzpolitik.org/2015/guenther-oettinger-netzneutralitaet-toetet-befuerworter-sind-taliban-artig/

- Belli, L. (Ed.). (2016). Net neutrality reloaded: Zero rating, specialised service, ad blocking and traffic management. FGV Direito Rio.

- Benedek, W., & Kettemann, M. C. (2013). Freedom of expression and the internet. Council of Europe Publishing.

- BEREC. (2012a). Differentiation practices and related competition issues in the scope of net neutrality. BEREC. https://berec.europa.eu/eng/document_register/subject_matter/berec/download/0/1094-berec-report-on-differentiation-practice_0.pdf

- BEREC. (2012b). A view of traffic management and other practices resulting in restrictions to the open Internet in Europe. Findings from BEREC’s and the European Commission’s joint investigation. http://berec.europa.eu/eng/document_register/subject_matter/berec/download/0/45-berec-findings-on-traffic-management-pra_0.pdf

- Berners-Lee, T. (2015). Guest blog: Sir Tim Berners-Lee, Founding Director, World Wide Web Foundation. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/2014-2019/ansip/blog/guest-blog-sir-tim-berners-lee-founding-director-world-wide-web-foundation_en.

- Bird & Bird, & Ecorys. (2019). Study on the implementation of the open internet provisions of the Telecoms Single Market Regulation. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union. https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/dae/document.cfm?doc_id=58874

- Braman, S. (2019). Looking again at findings: Secondary analysis. In H. Van den Bulck, M. Puppis, K. Donders & L. Van Audenhove (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of methods for media policy research (pp. 657–674). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brown, I., & Marsden, C. T. (2013). Regulating code: Good governance and better regulation in the information age. MIT Press.

- Castells, M. (2005). The information age: Economy, society and culture. Volume 1: The rise of the network society. Blackwell Publishing.

- Castells, M., & Cardoso, G. (Eds.). (2016). The network society. From knowledge to policy. Johns Hopkins Center for Transatlantic Relations.

- Christians, C. G., Glasser, T. L., McQuail, D., Nordenstreng, K., & White, R. A. (2009). Normative theories of the media. Journalism in democratic societies. University of Illinois Press.

- Cooper, A. (2014). How regulation and competition influence discrimination in broadband traffic management: A comparative study of net neutrality in the United States and the United Kingdom. DPhil Thesis - Oxford Internet Institute.

- Curran, K. (2009). Internet protocols. In K. Curran (Ed.), Understanding the internet. A glimpse into the building blocks, applications, security and hidden secrets of the Web (pp. 7–16). Chandos Publishing.

- Curran, K., Woods, D., & McDermot, N. (2009). What causes delay in the Internet? In K. Curran (Ed.), Understanding the internet. A glimpse into the building blocks, applications, security and hidden secrets of the Web (pp. 17–26). Chandos Publishing.

- de Sola Pool, I. (1974). The rise of communications policy research. Journal of Communication, 24(2), 31–42. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1974.tb00366.x

- de Sola Pool, I. (1983). Technologies of freedom. Harvard University Press.

- DESI. (2019). Connectivity - Broadband market developments in the EU. DESI - Digital Economy and Society Index. https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/dae/document.cfm?doc_id=60010

- DotEcon, Aetha Consulting, & Oswell &Vahida. (2017). Zero-rating practices in broadband markets. Brüssel: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/publications/reports/kd0217687enn.pdf

- Fidler, B. (2019). The evolution of internet routing: Technical roots of the network society. Internet Histories, 3(3-4), 364–387. doi:10.1080/24701475.2019.1661583

- Freedman, D. (2008). The politics of media policy. Polity Press.

- Freedman, D. (2014). The contradictions of media power. Bloomsbury.

- Gans, J. S. (2015). Weak versus strong net neutrality. Journal of Regulatory Economics, 47(2), 183–200. doi:10.1007/s11149-014-9266-7

- Gershon, R. A. (2016). Digital media and innovation. Sage.

- Hahn, R. W., & Wallsten, S. (2006). The economics of net neutrality. The Economists Voice, 3(6), 1–7.

- Höttges, T. (2015 October 28). Netzneutralität - Konsensfindung im Minenfeld. Deutsche Telekom AG. https://www.telekom.com/medien/managementzursache/291708

- Karppinen, K., & Moe, H. (2012). What we talk about when we talk about document analysis. In N. Just & M. Puppis (Eds.), Trends in communication policy research. New theories, methods and subjects (pp. 177–193). Intellect.

- Karppinen, K., & Moe, H. (2019). Texts as data I: Document analysis. In H. Van den Bulck, M. Puppis, K. Donders & L. Van Audenhove (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of methods for media policy research (pp. 249–262). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kirkpatrick, B. (2016). The historical moment of net neutrality: An interview with former U.S. Federal Communications Commissioner Michael J. Copps. International Journal of Communication, 2016(10), 5779–5794.

- Krämer, J., Wiewiorra, L., & Weinhardt, C. (2013). Net neutrality: A progress report. Telecommunications Policy, 37(9), 794–813. ]. doi:10.1016/j.telpol.2012.08.005

- Kroes, N. (2010). Net neutrality in Europe. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-10-153_en.pdf.

- Krone, J., & Pellegrini, T. (Eds.). (2012). Netzneutralität und Netzbewirtschaftung. Nomos.

- Laffont, J.-J., & Tirole, J. (1991). The politics of government decision-making: A theory of regulatory capture. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(4), 1089–1127. doi:10.2307/2937958

- Lasswell, H. D. (1956). The decision process: Seven categories of functional analysis. University of Maryland Press.

- Layton, R., Elaluf-Calderwood, S. M. (2015). Zero rating: Do hard rules protect or harm consumers and competition? Evidence from Chile, Netherlands and Slovenia. SSRN - Social Science Research NetworkRetrieved from http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2587542

- Le Crosnier, H., & Schafer, V. (2011). La neutralité de l’internet. Un enjeu de communication. CNRS Éditions.

- Lehofer, H. P. (2015, October 5). “Maßnahmen betreffend offenes Internet” und Roaming: die vorläufige Einigung im Trilog. e-comm. Blog zum österreichischen und europäischen Recht der elektronischen Kommunikationsnetze und -dienste. https://blog.lehofer.at/2015/07/offenes-internet.html?pfstyle=wp

- Lessig, L. (1999). Code and other laws of cyberspace. Basic Books.

- Lessig, L., McChesney, R. W. (2006, July). No tolls on the internet. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/06/07/AR2006060702108.html?

- Löblich, M., & Musiani, F. (2014). Net neutrality and communication research. In E. L. Cohen (Ed.), Communication yearbook (vol. 38, pp. 339–367). Routledge. doi:10.1080/23808985.2014.11679167

- Mailland, J. (2018). Building Internet policy on history: Lessons of the forgotten 1981 network neutrality debate. Internet Histories, 2(1-2), 1–19. Retrieved from doi:10.1080/24701475.2018.1450702

- Mansell, R. (2011). New visions, old practices: Policy and regulation in the Internet era. Continuum, 25(1), 19–32. doi:10.1080/10304312.2011.538369

- Mansell, R. (2012). Imagining the internet. Communication, innovation and governance. Oxford University Press.

- Marsden, C. T. (2017). Network neutrality. From policy to law to regulation. Manchester University Press.

- McConnell, A. (2010). Policy success, policy failure and grey areas in-between. Journal of Public Policy, 30(3), 345–362. doi:10.1017/S0143814X10000152

- Meese, J. (2019). Telecommunications companies as digital broadcasters: The importance of net neutrality in competitive markets. Television & New Media https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1527476419833560 doi:10.1177/1527476419833560

- Meier, W. A. (2019). Meta-analysis. In H. Van den Bulck, M. Puppis, K. Donders & L. Van Audenhove (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of methods for media policy research (pp. 103–119). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Musiani, F., & Löblich, M. (2016). The net neutrality debate from a public sphere perspective. In S. Simpson, M. Puppis & H. Van den Bulck (Eds.), European media policy for the twenty-first century. Assessing the past, setting agendas for the future (pp. 161–174). Routledge.

- Musiani, F., Schafer, V., & Le Crosnier, H. (2012). Net neutrality as an internet governance issue: The globalization of an American-Born Debate. Revue Française d Etudes Américaines, 134(4), 47–63. Retrieved from www.cairn.info/revue-francaise-d-etudes-americaines-2012-4-page-47.htm doi:10.3917/rfea.134.0047

- Powell, A., & Cooper, A. (2011). Net neutrality discourses: comparing advocacy and regulatory arguments in the United States and the United Kingdom. The Information Society, 27(5), 311–325. doi:10.1080/01972243.2011.607034

- Prasad, R. (2018). Ascendant India, digital India: How net neutrality advocates defeated Facebook’s Free Basics. Media, Culture & Society, 40(3), 415–431. doi:10.1177/0163443717736117

- Puppis, M., & Van den Bulck, H. (2019). Introduction: Media policy and media policy research. In H. Van den Bulck, M. Puppis, K. Donders & L. Van Audenhove (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of methods for media policy research (pp. 3–21). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rinas, S. P. (2019). Alter Wein in neuen Schläuchen? Netzneutralität im EU-Gesetzgebungsprozess. In W. J. Schünemann & M. Kneuer (Eds.), E-Government und Netzpolitik im europäischen Vergleich (pp. 235–258). Nomos.

- Rogerson, D. A., Seixas, P., & Holmes, J. R. (2017). Net Neutrality: An Incyte Perspective responding to recent developments in the European Union. Australian Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy, 4(4), 17–57. doi:10.18080/ajtde.v4n4.79

- Savin, A. (2018). EU telecommunications law. Edward Elgar.

- Schmidt, S., & Schünemann, W. J. (2013). Europäische Union. Eine Einführung. Nomos.

- Schroeder, R. (2019). Theorizing the uses of the web. In N. Brügger & I. Milligan (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of web history (pp. 86–98). SAGE.

- Simpson, S. (2012). New approaches to the development of telecommunications infrastructures in Europe? The evolution of European Union policy for next-generation networks. In N. Just & M. Puppis (Eds.), Trends in communication policy research. New theories, methods and subjects (pp. 335–351). Intellect.

- Tanenbaum, A. S., & Wetherall, D. J. (2011). Computer networks. Pearson.

- Trappel, J., & Maniglio, T. (2011). On media monitoring - The media for democracy monitor (MDM). In J. Trappel & W. A. Meier (Eds.), On media monitoring. The media and their contribution to democracy (pp. 65–134). Peter Lang.

- Van Audenhove, L., & Donders, K. (2019). Talking to people III: Expert interviews and elite interviews. In H. Van den Bulck, M. Puppis, K. Donders & L. Van Audenhove (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of methods for media policy research (pp. 179–197). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Van Daalen, D. O. (2012). Netherlands first country in Europe with net neutrality. https://www.bof.nl/2012/05/08/netherlands-first-country-in-europe-with-net-neutrality/.

- van Dijk, J. (2012). The network society. Sage.

- van Schewick, B. (2016). Internet architecture and innovation in applications. In J. M. Bauer & M. Latzer (Eds.), Handbook on the economics of the internet (pp. 288–322). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Vogelsang, I. (2010). Die Debatte um Netzneutralität und Quality of Service. In D. Klumpp, H. Kubicek, A. Roßnagel & W. Schulz (Eds.), Netzwelt - Wege, Werte, Wandel. (pp. 5–14). Springer.

- Wu, T. (2003). Network neutrality, broadband discrimination. Journal of Telecommunications and High Technology Law, 2(1), 141–176.

- Wu, T., & Yoo, C. S. (2007). Keeping the internet neutral? Tim Wu and Christopher Yoo Debate. Federal Communications Law Journal, 59(3), 575–592.

- Yoo, C. S. (2012). Network neutrality and the need for a technological turn in internet scholarship. Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper Series (12-35). http://ssrn.com/abstract=2063994

- Zittrain, J. L. (2008). The future of the internet - and how to stop it. Yale University Press.