Abstract

This paper provides an analysis of a nostalgic Myspace discourse that contradicts the narrative of Myspace as a failed platform. The Myspace nostalgia discourse is especially dominant on Twitter and responds to what Miltner refers to as the “coding fetish discourse”. It re-imagines Myspace through the lens of digital skill development and reinforces the framing of coding as a net good for social mobility, particularly for women and people of colour. It also offers trenchant critiques aimed at platform capitalism and platform governance that position Myspace as a foil for “toxic” and “gentrified” contemporary social media platforms. Contrary to previous popular framings of Myspace as an unsafe environment, Myspace coding Tweets offer a generative reimagining of Myspace as a place where young people learned valuable skills. In doing so, these Tweets take the very elements that supposedly caused Myspace’s decline—its chaotic aesthetics and the dominance of people of colour and young women—and reposition them at the core of Myspace’s value and worth. We argue that these nostalgic reframings of Myspace ultimately reflect contemporary discourses about coding and social media platforms: Myspace may have “died”, but it is our current sociotechnical ideals and anxieties that brought it back to life.

Introduction

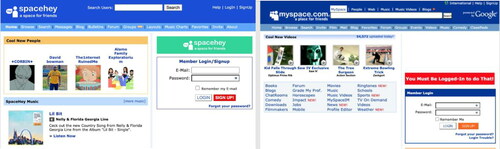

In November 2020, a new social network called SpaceHey was launched by An, a German 18-year-old. With the tagline “a space for friends”, SpaceHey has functionality that differs from what’s available on many current social media platforms: blogs, bulletins, an Instant Message function, and, crucially, the ability to use HTML and CSS to customize profiles and play music. If this sounds familiar to social media users from the 2000s, it should: SpaceHey was recreated to look exactly like the original Myspace. “I was just a few years old when Myspace was around, so I never had a chance to use it”, An explained to BuzzFeed. “I think that there’s no platform compared to Myspace nowadays, so I came up with the idea to create a new platform, similar to the OG Myspace where everyone can be creative, and there are no algorithms around” (Heinrich, Citation2021). An’s idea certainly seemed to resonate: as of April 2021, SpaceHey had 120,000 registered users (ibid) ().

Although it might come as a surprise to An and the users of SpaceHey, the original Myspace still exists, although—as the popularity of SpaceHey makes evident—it is largely seen as a “dead” platform (Solon, Citation2018). Launched in 2003, Myspace soon became the most visited website in the United States (Cashmore, Citation2006). But by 2009, it was surpassed by Facebook (Albanesius, Citation2009), which became (and has remained) the dominant Western social network. Although there are a variety of explanations for Myspace’s downturn (e.g. Dredge, Citation2015), a prevalent narrative surrounding the platform’s failure focuses on the racialized, gendered, and classed tastes of its least desirable users—particularly, girls and BIPOC youth—combined with the perception that the platform was unsafe for children. At the peak of its decline, Myspace was seen as a place where “ghetto” tastes prevailed, leading to “white flight” amongst more privileged teens (boyd, Citation2013), a perception that was also reflected in popular media at the time (see Mims, Citation2010). Members of the tech establishment made similar inferences, describing it as a “junk heap of bad design” (Tsotsis, Citation2011); even Tom Anderson, Myspace’s founder, called it a “cesspool” after he left the company (Gabbatt, Citation2011). Myspace was also the subject of a full-blown moral panic around child victimization, driven almost entirely by media sensationalism (Marwick, Citation2008; see also BBC News, Citation2006; Reuters, Citation2007).

However, a new discourse around Myspace has been circulating in the past decade that reframes and reimagines Myspace in contrast to previously accepted narratives of danger and poor taste. This discourse, which we call the Myspace nostalgia discourse, views Myspace through a nostalgic lens, positioning it as an idealized social media platform where young people—girls and BIPOC youth in particular—learned valuable technical skills. While elements of this discourse can be found within online newsmedia (e.g. Janjigian, Citation2016), it is particularly visible on Twitter, where Tweets romanticizing Tom Anderson as “sweet, smiling Tom” who “gave us everything” rack up tens of thousands of likes and retweets (e.g. @akirathedon, 17 August Citation2018). Niemeyer (Citation2014) explains that, more than a trend or fashion, nostalgia is often related to imagining and (re)inventing the past, present, and future (p. 2). Taking inspiration from Niemeyer’s provocation, “what is nostalgia doing?” (ibid.), we ask, where did this longing for the “old” Myspace come from? Given Myspace’s previous reputation as an unsafe environment that exemplified tacky internet aesthetics, why is it now being nostalgically reimagined as an idealized playground of skill development for the youth that were supposedly so at risk there?

An analysis of over 2,000 sampled Tweets from 2012–2021 suggests that the emergence of the Myspace nostalgia discourse is connected to the development and convergence of two discrete social phenomena: the emergence of what Miltner (Citation2019) calls the “coding fetish” and dissatisfaction with social media platform governance and its relationship to “platform capitalism” (Srnicek, Citation2017). Myspace users needed to learn basic HTML and CSS to creatively customize their profiles, affordances that are mostly absent from contemporary social media platforms; this skill acquisition is now being framed as Myspace’s “coding legacy” (Codecademy, Citation2020) that has allegedly enabled entry for traditionally excluded groups into highly paid technology careers. This idealization of Myspace as a coding playground reflects the broader obsession with coding as essential for access to the most desirable and highly paid labor markets, particularly for minoritized groups such as women and people of color. Relatedly, the view of Myspace as creative and customizable also serves as a foil to contemporary social media platforms, which are seen to prioritize individuals’ monetizable behaviors rather than their creative self-expression, and to engage in data extraction, expansion/monopolization, surveillance, and censorship.

Viewed through these contemporary lenses, the Myspace nostalgia discourse takes some of the very elements that supposedly caused Myspace’s decline—its chaotic aesthetics and the dominance of people of color and young women—and repositions them at the core of Myspace’s value and worth. Overall, what the Twitter instantiation of the Myspace nostalgia discourse offers us is an important reflection on how technologies’ societal perceptions and perceived value can change dramatically in response to contemporary discourses, and—responding to the themes of this special issue—how platforms once seen as “dead’’ can be given new life through shifts in sociocultural ideals, values, and market conditions.

Literature review

Platform politics: then and now

Founded in late 2003 by Tom Anderson and Chris DeWolfe, Myspace has cemented its place in the cultural imagination like few other social media platforms. At the crux of Myspace’s popularity was its “considerable flexibility” (Jones et al., Citation2008, n.p.): anyone with a Myspace account could use Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) and Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) to customize their personal profiles in a manner unparalleled by contemporary social media platforms (Gallant et al., Citation2007). Myspace was one of several sites in the 2000s to offer personalized profiles—including Xanga, Blogspot, tumblr, BlackPlanet, and LiveJournal, among others—situating it in a distinct moment of internet history. Myspace enjoyed several years of popularity, surpassing Google as the most visited website in the U.S. in 2006 (Press, Citation2018), but it was soon overtaken by the then-hot new platform: Facebook. danah boyd’s (Citation2013) research explains Myspace users’ “flight” to Facebook: although, for a time, teens continued to use both sites, their user bases became divided along racial lines, with white teens feeling that Myspace became dominated by what they saw as “subcultural” (p. 207) music tastes—that the site had become too “ghetto” (p. 203), to quote one research participant. The earliest Facebook adopters also had to have a .edu email address to register with the site, making it a marker of “status and maturity” (p. 207) for teens, further heightening its appeal. While white teens dominated Myspace at the height of its popularity (Jones et al., Citation2008), Facebook’s then-reputation as the more “mainstream” (boyd, Citation2013, p. 207) platform meant Myspace became increasingly valuable to minoritized teens, particularly those who were Black or Latinx. As Lingel (Citation2021) notes, Myspace’s demise sits within a broader “gentrification of the internet”, where conflicts over “accessing resources, expressing identity, and the ability of communities to grow and thrive” shape the platform landscape, particularly as “digital platforms welcome some groups more than others” (p. 22).

Panic-laden media coverage also contributed heavily to Myspace’s demise. As Marwick explains, the site was “consistently portrayed in the mainstream media” as a place which facilitated “interactions between ‘online predators’ and minors for purposes of sexual activities” (2008, n.p.). These concerns—which, as Marwick concludes, were “disproportionate to the amount of harm produced by the site” (2008, n.p.)—were also echoed in academic accounts of Myspace. Literature often focused on the dominance of “risky” behaviors on Myspace, like certain sexual behaviors and references to substance use (e.g. Bobkowski et al., Citation2012; Moreno et al., Citation2009). Fears about young people’s privacy also prevailed in press coverage of Myspace (Marwick, 2008) and in academic literature (e.g. Fogel & Nehmad, Citation2009; Moreno et al., Citation2007). Myspace was one of the first globally popular social media sites to ask for detailed information about its users (standard information like birthday and gender, along with information about music preferences and “top” friends), though it never faced the kinds of data mining controversies common to contemporary platforms (Kennedy, Citation2016). In the Myspace era, critics were concerned about the volume of information young people were publishing about themselves on the internet and, by extension, the ease with which “predators” could find and potentially harm them (Marwick, 2008). Though, as Jones et al. (Citation2008) note, the volume of self-disclosure present among young Myspace users was not significant enough to warrant such a panic.

The “risks” characterising Myspace at the height of its popularity are very different from those related to now-popular platforms. In the years since Myspace’s “passing”, so to speak, social media technologies have become more embedded into everyday life (Hine, Citation2015). This means anxieties around currently dominant platforms have less to do with worrying conflations between “online” and “offline” lives and far more to do with, for example, the volume of data that is inferred from their usage, a lack of public trust around tech companies’ data handling following scandals like Cambridge Analytica, and the use of digital data to further entrench social inequalities (e.g. Benjamin, Citation2019). The politics of content moderation are another major concern, particularly around the failure of tech giants to adequately or appropriately moderate harmful content including racist material (Matamoros-Fernández & Farkas, Citation2021) and posts promoting self-harm or suicide (Gerrard, Citation2018). We can see these contemporary anxieties reflected in the Myspace nostalgia discourse, particularly when it comes to anxieties and scepticism around current platform governance practices. These concerns are also combined with another dominant sociotechnical discourse around technical skill development that particularly focuses on coding.

The coding fetish and its discourse

At the core of Myspace’s nostalgic reimagining is the idea that it taught its young users how to code in a way that was, in retrospect, beneficial to them as adults on the labor market (or would have been, had they continued to code post-Myspace). This idea is connected to a broader obsession with coding that has taken hold within the technical, educational, social, cultural, and political landscapes of the West; Miltner (Citation2019) has conceptualized this obsession as the “coding fetish”. A fetish involves “endowing real or imagined objects or entities with self-contained, mysterious, and even magical powers to move and shape the world in distinctive ways’’ (Harvey, Citation2003, p. 3). Harvey suggests that fetishes develop when “we endow technologies—mere things—with powers they do not have”, such as the capacity to ameliorate social ills, stimulate the economy, or improve our lives (ibid.). In the case of the coding fetish, coding—a technical practice that is, in its simplest form, writing a series of instructions for a machine to follow—has been unrealistically imbued with the ability to address a series of entrenched structural problems involving gendered, racialized, and economic inequalities. Despite the fact that learning to code is not (and cannot) be the solution to major societal issues like racism and sexism, the coding fetish is incredibly powerful: since it took hold around 2012, a plethora of for-profit and nonprofit organizations have been established, policy initiatives proposed and implemented, and legislation enacted, all with code-as-solution at their core (Greene, Citation2021; Miltner, Citation2019; Williamson, Citation2015; Citation2016; Williamson et al., Citation2019).

Miltner (Citation2019) explains that the coding fetish is both articulated and perpetuated by a discourse that suggests that “anyone can code”; this discourse claims that if certain social groups (such as women and racialized minorities) acquire coding skills, any or all of three interrelated outcomes will come to fruition: one, economically marginalized individuals and/or groups will secure well-paid employment that will simultaneously facilitate social mobility while addressing a tech “skills gap”; two, the often-problematic gender and racial politics of the tech industry will be ameliorated; and three, that people (but children especially) will be prepared for a highly automated future dominated by artificial intelligence. Of course, these claims entirely ignore the long-standing and complex nature of the problems that learning to code purports to solve, but the “charisma” (Ames, Citation2019) of coding as a solution means that even when faced with evidence to the contrary, coding is still positioned as an answer to some of society’s most intractable problems (see also Greene, Citation2021).

One of the reasons that the coding fetish is so appealing is that it offers seemingly straightforward solutions to complex issues. Miltner (Citation2019) explains that the coding fetish offers three key rationales as to why certain social groups should learn to code; two of them are particularly relevant to the nostalgic reimagining of Myspace. The first of these rationales centers on economic arguments, suggesting that those who learn to code will be hired into highly paid and stable careers that will act as a “pathway to the middle class”, as in the US (The White House, Citation2012) or a “pipeline to prosperity”, as in the UK (see Davies & Eynon, Citation2018). The second rationale positions coding as a solution for the diversity problems within the tech industry, particularly concerning women and minoritized racial groups; this often positions learning to code in terms of a STEM “pipeline” and various Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion initiatives. In these ways, women and people of color (and especially those from poor backgrounds) have been positioned at the center of the coding discourse, where they have been encouraged to learn to code for the benefit of themselves, the tech industry, and the economy—often with little concern for the broader structural contexts that kept these groups out of computing to begin with. As will be discussed shortly, these elements of the coding fetish discourse are at the crux of why MySpace has been idealized in retrospect, as part of the nostalgic yearning for Myspace is centered on its perception as a place of technical development for youth from social groups that are excluded from traditional computing “pipelines”.

Nostalgia

Definitions and understandings of the term “nostalgia” have changed considerably over time, originating in the 17th century as a medical term referring to a nervous disease (see Boym, Citation2001) and transforming into a word that most commonly describes a specific emotion, mood state (e.g. Schwarz, Citation2009), or “structure of feeling” á la Raymond Williams (e.g. Tannock, Citation1995). Nostalgia has been described as “the name we commonly give to a bittersweet longing for former times and spaces” (Niemeyer, Citation2014, p. 1), or “as a contemplative, bitter-sweet mood, combining the sweetness of the past memory and the sorrow of its passing” (Schwarz, Citation2009, p. 351). Nostalgia is both individual and social, and concerned with the relationship between personal memory and collective memory (Boym, Citation2007, p. 9). Or, as Niemeyer describes it, nostalgia is “a liminal, ambiguous phenomenon that migrates into deep emotional and psychological structures as well as into larger cultural, social, economic and political ones” (2014, p. 6).

How nostalgia is defined or understood is also related to what it is seen to achieve. In response to the questions, “what is nostalgia doing?” and “what is ‘hidden’ behind these longings?” Niemeyer (Citation2014) suggests that nostalgia is “relating to a way of living, imagining, and sometimes exploiting or (re)inventing the past, present, and future” (p. 2). Pickering and Keightley (Citation2006) suggest that a “specifically modern” concept of nostalgia “has been used to identify both a sense of personal loss and longing for an idealized past, and a distorted public version of a particular historical period or a particular social formation in the past” (p. 922). Tannock similarly argues that nostalgia is a “periodizing emotion” that distinguishes between “then” and “now” (Citation1995, p. 456). He explains that nostalgic rhetoric invariably incorporates three ideas: a prelapsarian world (e.g. a Golden Age), a lapse (e.g. a separation or differentiation), and then the present, postlapsarian world that is perceived as lacking or deficient in some way.

This longing for an idealized but distorted past is also central to nostalgias focused specifically on media and technology. Technostalgia is a concept that describes a specific nostalgia reserved for “outdated” communication forms (Bolin, Citation2016; Pinch & Reinecke, Citation2009). In his research on nostalgia in generational media experiences, Bolin (Citation2016) found that technostalgia was partly a mourning of dead media technologies, particularly media technologies central to “formative youth experiences” and childhood memories. Technostalgia, Bolin argues, is “highly collective”, representing the shared experiences of people who have similar understandings of “bygone or outdated media technologies” (p. 261)—something that can be clearly seen in the Myspace nostalgia discourse. Indeed, Myspace is positioned within the discourse as emblematic of an idealized, prelapsarian era of social media that encouraged creativity and eschewed the problems of the postlapsarian present, such as data extraction and content moderation issues. Connecting specific practices (i.e. coding) to a yearning for technologies from a “simpler” time (i.e. early social media platforms), those who perpetuate the Myspace nostalgia discourse invoke current technological discourses around coding and the harms of platform capitalism to recast Myspace in a radically different light from how it was perceived at both the height of its popularity and the early stages of its demise.

The ethics and methods of Twitter research

To find a broad range of Tweets addressing Myspace nostalgia, we used the Web Data Research Assistant (WebDataRA) tool.Footnote1 Using this tool, we collected Tweets using the term “Myspace” plus five additional search terms in a Boolean string: code OR coded OR coder OR coding OR HTML. We originally included a broader assortment of similar search terms—for example, Myspace + programming, or Myspace + CSS—but they returned near-identical results. Our original data collection period took place across the month of January 2021 and so, to ensure consistency, we collected all Tweets using the above-listed five search terms from every January over a ten-year period (2011–2021).Footnote2 We did a reverse-chronological search from 2021 backwards, stopping in 2011 because there were no Tweets that fit our search terms after 2012. These Tweets were obtained from the “Latest” search function on Twitter, which shows users a chronological list of Tweets pertaining to their search terms.Footnote3 After “cleaning” the data and removing 668 irrelevant Tweets, we were left with a total of 2146 Tweets. The following table shows how many Tweets were posted to our four search terms in total each January ().

Table 1. Total number of Tweets posted to each search term per year (2011–2021).

To get a sense of what themes were the most resonant/popular outside of our sampling period, and to ensure we found the most “viral” Tweets that involved our search terms, we also used Twitter’s Advanced Search function to search for Tweets that received over 100 “likes”. Interestingly, while we searched all the way back to the launch of Twitter (2006), these search terms only yielded results from 2013 onwards, suggesting that the rise of Myspace nostalgia is connected to the broader coding fetish discourse, which began in 2012. This process gave an additional 159 Tweets, bringing us to a total of 2305 Tweets.

To obtain a clearer understanding of Myspace nostalgia among Twitter users, we conducted a qualitative thematic analysis of the 2305 Tweets in our dataset (Gibson & Brown, Citation2009; Guest et al., Citation2012). We developed 36 initial coding categories but, as Guest et al. (Citation2012) predict, many of our codes were “difficult to distinguish and should in fact be collapsed into a single defined code” (p. 71). The final version of our codebook therefore consisted of three top-level themes and nine sub-themes. “To maintain rigor” (Guest et al., Citation2012, p. 12), each author split the dataset in half and allocated primary codes to their half of the dataset. They then switched datasets to assign alternative primary codes if necessary.

This project presented ethical challenges at all stages of the research process. As Gerrard (Citation2020) notes, content that is “unprotected by users’ privacy settings” (p. 6) should not be readily viewed as “public” data and therefore fair game to use for research purposes. At the same time, the volume of Tweets in our dataset hindered us from obtaining informed consent from every user whose Tweets we collected. To address these ethical conundrums, we protected our participants’ identities in two main ways: (1) for non-repeated/unique Tweets, we used what Markham (Citation2012) calls “fabrication”, which is the construction of representative interactions without the reproduction of exact language that may be searchable and traceable. We did not include usernames for these Tweets, to abide by Twitter’s Developer Terms (Twitter, Citation2020), and (2) for Tweets that are reproduced without editing with high frequency in our dataset, or for “viral” Tweets with thousands of likes and retweets, we attributed that Tweet to its original author.

“I miss coding on Myspace”: the Myspace nostalgia discourse

Our thematic analysis of the dataset revealed three dominant trends about what we call the Myspace nostalgia discourse. Tweets about Myspace and coding first appeared in 2012, which is the same year that the coding fetish discourse became prevalent across the West; this timing suggests that the specific Myspace nostalgia in play is closely, if not directly, connected to the emergence of the coding fetish discourse. The number of Tweets is relatively stable across each year, except for 2021, which saw an uptick in attention (rising from 258 to 583 Tweets in the space of one year). A combination of these factors led Myspace to “trend” on Twitter in early 2021 (Ngo, Citation2021): then-U.S. President Donald Trump being banned from Twitter and a host of other social media platforms, prompting Twitter users to joke that he might have to start using Myspace (Campbell, Citation2021), and the launch and rise of SpaceHey ().

Table 2. Tweets coded to each theme, organised by year.

We have divided our data analysis into three main categories, each of which speaks to the dominant themes that emerged through our empirical data: (1) General Nostalgia (largely about missing Myspace as an exemplar of a “simpler” time in the history of social media), (2) Skills (that Myspace was a place for skill development, particularly “coding” and HTML, often developed during a person’s youth), and (3) Platform Politics (the nostalgia for Myspace was often oppositional in the sense that Myspace was seen as a “purer” alternative to untrustworthy modern platforms like Facebook).

General nostalgia

General Nostalgia was the second most common primary coding category (25%) applied to the Tweets in our dataset. Although General Nostalgia was allocated its own theme in our dataset, it is worth noting that this theme had by far the most crossover with others; indeed, general nostalgia underpinned the entire dataset. Tweets within this theme are largely focused on Twitter users missing Myspace and reminiscing wistfully about their “Myspace days”. As Bolin (Citation2016) explains, people often feel nostalgic for older media, and that this is a natural part of the “generational experience” (p. 250) which is “developed towards media technologies and content from one’s formative youth period” (pp.250–251). Both Niemeyer (Citation2014) and Bolin (Citation2016) explain that this kind of media-based nostalgia is “bittersweet”, almost tragic, as it captures “something that one longs back for at the same time as one knows that this moment is impossible to regain” (Bolin, Citation2016, p. 252). In the case of the General Nostalgia tweets, it seems that this bittersweet yearning for the “simpler” times of one’s youth also reflects a longing for an earlier, more “innocent” phase in social media’s seemingly increasingly problematic history ().

Some of the first Tweets we coded as General Nostalgia were posted to the hashtags #MiddleSchoolMemories and #HighSchoolMemories. These Tweets often reminisce fondly about the “hours and hours” spent editing HTML and changing profile “layouts”, often in conjunction with other cultural touchstones (e.g. hairstyles and fashion trends, musical artists/genres) from the mid-00s. While we cannot make firm claims about Twitter users’ ages or identities, the references made in these Tweets suggest that users are likely at a specific age, perhaps in their mid-20s to early-30s, who would have been adolescents or young adults during Myspace’s peak. For many Twitter users of this demographic, Myspace was popular at a point in their youth when things were “simpler”:

“it’s 2006, i’m logged into Myspace, my basic coding skills are only impressive to myself, i’ve just completed a survey that asked if i had [a] crush, i put “maybe” in hopes my crush will see. simpler times”. (@oriananichelle, 8 January Citation2021)

At the same time, however, our findings suggest that the idealization of Myspace that is represented in the Myspace nostalgia discourse is far more than a wistful nod to a person’s youth; rather, it is a referendum on some perceived failures of the contemporary social media landscape. This dissatisfaction with current social media platforms is primarily reflected in Tweets that associate Myspace with a time when social media was “fun” and creative, before it was an “endless hellscape” filled with technologies of artifice, such as filters. A Tweet from 2021 typified the kind of direct comparison between Myspace and newer platforms in our dataset, saying:

Jesus bless Tom from Myspace. That was when social media used to be fun and focused on my friends and the only filters were a selfie angles and sparkles. And my coding skills were the best.

These tweets echo the type of “modern” nostalgia referenced by Pickering and Keightley (Citation2006), which combines both a sense of personal loss (e.g. when “my coding skills were the best”) and a longing for an idealized past (e.g. when sparkles were the only filters). It also reflects a new version of the “distorted public version” of Myspace that is focused on “fun” and is “focused on my friends”—a reimagining that ignores how Myspace was popularly perceived in its own time as a risky place that endangered children (e.g. boyd, Citation2013; Marwick, 2008). This is a far cry from how Myspace is seen now—as an idealized creative playground where marginalized and minoritized youth learned valuable digital skills.

Skills

Although nostalgia was present throughout the dataset, the most dominant theme by far (66%) connects to the portrayal of Myspace as a place for skill development, specifically “coding” and HTML, and particularly for women/girls, Black people, and young people. These Tweets directly reflect specific claims of the coding fetish discourse, particularly around the professional and monetary value of coding skills.

Just under half of the Tweets in the Skill category were simple Tweets either stating that the author learned coding skills on Myspace (“I learned HTML on Myspace”), expressing a general gratitude to Myspace for imparting technical skills (“Thanks for teaching me to code, Myspace”), or seeking social confirmation on their shared experiences (“Remember when we were learning to code on Myspace?”). These Tweets had a phatic quality to them (see Miller, Citation2017); their purpose seemed to be more social than informative, as if to identify themselves in some way—as someone who knows how to code, or as someone who is part of a “Myspace generation”.

Beyond these phatic Tweets, the most significant thread within the Skill theme concerned the perceived value of skills associated with participation on Myspace. These Tweets largely asserted that engagement with Myspace, particularly during childhood or teenage years, imparted skills that continue to be valuable in present-day careers or educational settings. For people in non-tech careers, these Tweets were often framed in terms of gratitude and/or incredulity that the HTML or coding skills that they picked up on Myspace are useful in their day-to-day responsibilities at work. A 2018 Tweet to this end reads, “Seriously, I figured out how to fix a problem in an email newsletter thanks to my old Myspace coding skills. So glad I had to have that killer background and embedded video when I was a teen”.

A common theme within the Tweets that focused on the value of Myspace coding experiences was the idea that Myspace was “secretly” teaching people to code, or that people were learning to code through profile customization and “didn’t even know it”. These Tweets suggest that activities that were previously seen as simple fun or part of basic engagement on the Myspace platform (e.g. profile customization with HTML) have now been reframed as valuable in light of the coding fetish discourse. A viral Tweet with 64,800 likes from user Nuff (@nuffsaidny, 14 July Citation2020) encapsulates this reframing, stating that “Myspace had everybody coding in HTML, CSS & JavaScript. Tom had us all doing front-end web development”.

This reframing of Myspace participation in relation to professional programming was common within our dataset, particularly amongst Tweets that expressed regret or dismay at the fact that they no longer had coding skills or did not pursue programming professionally; these Tweets overwhelmingly focused on the perceived financial benefits of coding. The Tweets in this theme are exemplified by user Kailah (@kailah_casillas, 19 August Citation2019) who Tweeted, “Remember when we all learned how to code so that we could personalize our Myspace pages? I should have stuck with that I’d probably be rich by now”. This theme was also represented in a series of now-deleted, viral Tweets by @ChrisTheHuman_ and @StillEWills that framed Myspace participation as “flirting” with a skill set worth $60,000 or $100,000, which reference commonly cited annual salaries for software engineers (e.g. Lohr, Citation2015).

In the later years of our dataset (2018 onward), we saw a bit of pushback against the idea that participation on Myspace constituted “coding”; a representative Tweet to this end from 2018 reads, “People love talking about Myspace and coding—searching for ‘Myspace layouts’ and copying and pasting the coding does not make you a programmer. Stop it”. Nevertheless, this pushback occupied a small percentage of our dataset. The idea that Myspace operated as a gateway for programming, especially for women, was far more common; furthermore, this narrative was pushed both individually and institutionally. Accounts for organizations Girls Who Code, DataWomen, and POC in Tech all published Tweets with links to interviews from women tech professionals who credited their start in the field with the Myspace profile customization of their youth. This narrative was also repeated by tech workers themselves; in a viral Tweet that received over 70,000 likes and 14,000 retweets, Ada Powers (@mspowahs, 23 August Citation2018) said,

Fine, I’ll spell it out: Myspace, LiveJournal, and NeoPets were able to teach kids—all kids, yes, but, and this is very important, largely girls—how to code because the coding education happened incidentally, outside the pipelines where people are told what they can and can’t do.

This perspective was also echoed in similar Tweets that defended Myspace and other Web 2.0 platforms (i.e. LiveJournal, NeoPets, tumblr) as sources of legitimate skill development.

The idea that participation on social media platforms operates as a form of informal skill acquisition, particularly for youth, appeared frequently within the dataset. Former Myspace users reflected on how advanced their “coding” skills were at such a young age; these Tweets also overlapped with the “regret” theme. For example: “Myspace taught an entire generation of 13-year-old girls basic HTML code”; “I learned basic HTML and CSS at age 11 lmao, wish I’d kept it up”; “It blows my mind that we were really out here coding our Myspace profiles in school”. An increase in discussions of youth and skill acquisition occurred in 2021, largely due to the soaring popularity of video-sharing platform TikTok, which allows users to create and share short multimedia clips. Several Twitter users drew comparisons between Myspace and TikTok, claiming “TikTok is this generation’s Myspace” and that videography and TikTok are to “Gen Z” what Myspace and coding were for “Millennials” (for a similar argument, see Khaled, Citation2019). A related thread that emerged in 2021 was about the dismissal of skills young people are currently learning on TikTok (i.e. video editing and compositing), which some Twitter users compared to the discounting of time spent on Myspace as a “waste of time”.

The Skills theme within our dataset clearly aligned with the core claims of the coding fetish discourse, namely the suggestion that coding offers a beneficial and remunerative career path for women and BIPOC. Indeed, the perception of Myspace as an unacknowledged or even dismissed source of skill acquisition is reflected in many of the skill-related Tweets and is portrayed as a unique and differentiating characteristic that sets Myspace apart from contemporary social media platforms.

Platform politics

The final overarching theme in our dataset was concerned with social media platform politics. In this theme, which comprised 9% of our overall dataset, Myspace nostalgia takes form in a comparative sense, with Myspace portrayed as an idealized social media platform in relation to contemporary social media platforms (and Facebook in particular). In many ways, the Platform Politics theme is less about Myspace itself and more of a critique of the contemporary social media landscape; specifically, key platform governance issues as well as certain features of what Srnicek (Citation2017) has labelled “platform capitalism”. It is important to note that although the Platform Politics theme is proportionately the smallest of the three main themes within our dataset, it is also comparatively recent, with 75% of the Platform Politics Tweets occurring from 2018 onward. This suggests that, just as the overall Myspace nostalgia connects to the emergence of the coding fetish discourse, the Platform Politics theme also connects to prevailing discourses that are highly critical of social media platforms, particularly concerning practices around data extraction (e.g. Kennedy, Citation2016; Srnicek, Citation2017), mis/disinformation (e.g. The Media Manipulation Casebook, n.d), and the regulation of harmful content (e.g. Gillespie, Citation2018).

In an overlap with the General Nostalgia and Skills categories, the Platform Politics Tweets often invoke a nostalgia for the affordances that made Myspace customizable, and for a “simpler” time when social media was “nicer”. However, unlike the Skills category, which suggest that the creativity and skill acquisition fomented by Myspace were benefits in and of themselves, the Platform Politics Tweets invoke Myspace’s affordances in the service of critiquing dominant social media platforms. In these Tweets, Myspace is positioned as a foil to these platforms: where Myspace offered “raw, unrestrained freedom”, dominant social media platforms are “super constrained”; where Myspace users were “expressing themselves”, current social media users are “online lemmings”; where Myspace offered “magic”, dominant social media platforms offer “utilitarian interfaces”; where Myspace “taught you HTML”, dominant social media platforms “taught people to be offended” and “the children to be fake”. Facebook in particular was the target of many of these comparisons; a Tweet typical of this theme stated, “A whole generation learned coding and web design from Myspace, Facebook is just a data thief”.

The complaint that dominant social media platforms, such as Facebook, “steal” users’ information was also at the heart of a meme that emerged in 2018 in conjunction with Mark Zuckerberg’s testimony in front of the U.S. Senate (see Cole, Citation2018). The “shout out to Tom” meme positions the Myspace founder Tom Anderson in opposition to other social media founders (e.g. Mark Zuckerberg), and celebrates him for refraining from “typical” social media platform ills, such as data extraction, monopolization, and mis/disinformation; some versions of the meme also lament “forsaking” Tom/Myspace for other, supposedly inferior platforms. A Tweet circulating the “shout out to Tom” meme had the highest metrics out of any other Tweet in our dataset by a large margin: the following Tweet from the Blerds OnlineFootnote4 (@BlerdsOnline, 28 December Citation2019) account received 212,700 likes and 46,100 retweets:

Shout out to Tom from Myspace. Homie cashed his check, and bounced. He never tried to influence elections, be an advocate for "free speech," purchase competitors, sell our information or any of that. Just taught us all some basic HTML and rolled out.

Although the “shout out to Tom” meme conveniently elides uncomfortable truths about Myspace’s data practices and their long-tail consequences (Cole, Citation2018), the accuracy of the meme is largely beside the point. Rather, the nostalgic reimagining of Myspace is less about the reality of Myspace as a platform and more about offering an ingress for complaints about (and distrust in) dominant social media platforms that reflect both academic and popular critiques of platform governance issues and key features of platform capitalism.

This pronounced distrust in dominant social media platforms was also reflected in another theme which appeared regularly in the Platform Politics Tweets. Appearing for the first time in 2017, these Tweets suggest that the “real” reason behind Myspace’s decline is that the powers-that-be (“Big Business”, “the government”, “they”) recognized Myspace as a site of skill development for marginalized groups (e.g. Black and brown youth; teenagers; “the masses”) and actively brought about the downfall of the site to prevent said groups from acquiring power/agency. A Tweet from user Big Elly (@mdeeeeee_, 14 October Citation2019) which received 2,100 likes and 1,300 retweets, provides a good example of this motif, stating, “Someone said Myspace stopped being popular because black and brown kids started to learn how to code and got good and they couldn’t have that and I think about that a lot”. While the attribution of Myspace’s downfall to an undefined group of nefarious stakeholders may seem somewhat conspiratorial, this perspective was also promoted by influential blogger, entrepreneur, and technologist Anil Dash. In response to rapper Junglepussy’s viral Tweet asking, “WHY DID I STOP CODING AFTER MYSPACE” (@junglepussy, 6 November Citation2018), Dash responded, “Because the tech industry fought like hell to erect barriers against platforms like Myspace & Neopets that were letting underrepresented folks actually *make* the web instead of just consuming it”. (@anildash, 9 November Citation2018).Footnote5 Again, whether the decline of platforms like Myspace and Neopets can be fully attributed to a concerted effort by industry insiders to deprive minoritized youth of digital opportunity is debatable. What seems clear, however, is that nostalgic reframings of Myspace directly reflect widespread, contemporary technological discourses about technical skill and access, as well as the lopsided power relations between social media platforms and their users.

Conclusion: “dead” platforms and the meaning of nostalgia

The original question underpinning this paper was, “what are the contours of contemporary Myspace nostalgia, and where did it come from?” This paper suggests that the Myspace nostalgia discourse has developed in response to two interrelated sociotechnical phenomena: the emergence of the coding fetish and growing public dissatisfaction with key features of platform capitalism (e.g. data extraction) and platform governance concerns (e.g. content moderation). This discourse re-imagines Myspace through the lens of digital skill development, reinforcing the framing of coding as a net good for social mobility and inclusion in tech, particularly for women and people of color. It also offers trenchant critiques of platform capitalism and platform governance that position Myspace as a foil for “toxic” and “gentrified” contemporary social media platforms. In doing so, the Myspace nostalgia discourse takes the same elements that were purportedly at the heart of Myspace’s decline—its supposedly undesirable user base and their technical practices in particular—and reframe them as Myspace’s enduring “legacy”.

As we have argued, the view of Myspace as an idealized platform where youth were both free from the ills of contemporary platform capitalism and imbued with valuable technical skills is an almost complete reimagining of what Myspace was and where its value laid. At the height of its popularity, Myspace was not commonly regarded as a place for skill development, but as a place of risk—both from predators and from supposedly “undesirable” cultural influences. There was some academic literature that suggested that Myspace encouraged “copy and paste” literacies that would be valuable in a broader digital media landscape (e.g. Perkel, Citation2008), but even within the academic literature of the time, youth-at-risk was a primary focus.

So where did this shift come from? First, it’s important to note the Myspace nostalgia discourse is coming, at least partially, from adults who used Myspace in their youth. The discourse of risk was one that was generated by adults about youth at the time; whereas the nostalgia discourse comes from those same youth who are now adults. Clearly, former Myspace users’ perceptions of what they were doing as young people on Myspace do not align with the moral panic that influenced the views of their parents and other adults—e.g. they weren’t at risk, they were learning important technical skills that are now highly valued on the contemporary labor market. However, it is also worth pointing out that this nostalgia for Myspace is not just perpetuated by former users, but by young adults—like An, founder of SpaceHey—who never experienced Myspace in its heyday.

It is here where we come to the crux of the issue, which is that Myspace’s revival is less about the reality of Myspace’s history and user practices and more of a reflection of other powerful—and most importantly, contemporary—sociotechnical discourses. Tannock (Citation1995) asserts that any critical reading of nostalgic rhetoric or discourse should focus on how a Golden Age is constructed, as well as how the (dis)continuity between that Golden Age and the present is established. Without a deep cultural investment in the value of coding and what it supposedly can do in terms of social mobility and well-paid, stable employment, the framing of Myspace as this creative, technical sandbox would mean very little; furthermore, the idea of “sweet, sweet Tom” Anderson as this benevolent leader who “never deleted a post/never suspended an account/never rearranged a timeline” (@akirathedon, 17 August Citation2018) would have very little resonance or traction without current public anxieties about specific features (or “harms”) of social media.

Indeed, Myspace is not the only “dead” platform that is subject to this kind of treatment. Tiidenberg et al. (Citation2021) explain that tumblr—still alive, though barely—is facing a similar reimagining, with journalists wistfully remembering the platform for teaching its young users about everything from gender identities to writing skills. In our dataset, other platforms mentioned in conjunction with Myspace (e.g. BlackPlanet, Neopets, Xanga, tumblr), and some of the Tweets in our dataset were written in response to nostalgic tweets about other social networking sites, such as LiveJournal. In Citation2018, user bletchley punk wrote:

People like to shit on LiveJournal, but having one inspired me to learn:

HTML/CSS

hex code (for picking theme colors)

how to make animated gifs

image compression

basic webhosting

basic security

a ton of Photoshop

content & community (@BletchleyPunk, 9 Nov 2018)

This tweet echoes the main thrust of the “Skills” thread in the Myspace nostalgia discourse, which in turn, reflects the key tenets of the coding fetish discourse, particularly in terms of the inherent worth of coding and other technical skills.

Overall, what the Twitter instantiation of the Myspace nostalgia discourse offers us is an important reflection on how technologies’ societal perceptions and perceived value can shift dramatically in response to contemporary discourses. In the space of a decade, Myspace went from being perceived as a “cesspool” (Gabbatt, Citation2011) to being heralded as the ideal social media platform because the very same elements at the root of those assessments—its user base, its aesthetics, its customizability, its perceived dissimilarity to Facebook—shifted in their perceptions of worth over time. This is not just the case for “dead” platforms, either; some of the very same elements that originally drew users to Facebook—its fixed design, for example—are now seen as evidence of its “soulless’’ and “evil” nature. Never mind that both Facebook and Myspace were (and are) both owned by media conglomerates, and that they both engage(d) in many of the same platform capitalist practices, particularly regarding data extraction (see Cole, Citation2018).

Coming back to the question of “what is nostalgia doing?”, in the case of Myspace, it’s reflecting our own values and anxieties back at us. The past is almost always viewed through the lens of the present; the re-evaluations of late 1990s and early 2000s popular culture after #MeToo and other social justice movements, for example, make that quite clear (e.g. Petersen, Citation2021; Stark, Citation2021). The meaning that we assign to Myspace—or any sociotechnical object—is not fixed, but instead shifts over time. Myspace may have “died”, but it is our current sociotechnical ideals and anxieties that brought it back to life.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kate M. Miltner

Kate M. Miltner is a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions TRAIN@Ed Fellow at the Centre for Research in Digital Education and a Research Affiliate at the Edinburgh Futures Institute, University of Edinburgh.

Ysabel Gerrard

Dr. Ysabel Gerrard (she/her) is a Lecturer in Digital Media and Society at the University of Sheffield, UK. Her research on digital media has been published in venues like New Media and Society, and she is the current Chair of ECREA’s Digital Culture and Communication section.

Notes

1 WebDataRA was developed by Professor Leslie Carr of the Web and Internet Science Research Group.

2 We acknowledge that some Tweets may be “missing” from our dataset for various reasons, as discussed by Driscoll and Walker (Citation2014).

3 As opposed to an algorithmically organised list, see Twitter (Citation2020).

4 “Blerds” is a portmanteau for “Black nerds”.

5 NB: The crux of Dash’s argument, which he originally put forth in 2012, was less about depriving underrepresented folks from digital opportunity and more about a shift toward a closed, proprietary web. See https://anildash.com/2012/12/13/the_web_we_lost/

References

- Ada Powers. [@mspowahs] (2018, August 23). Fine, I’ll spell it out: Myspace, LiveJournal, and NeoPets were able to teach kids—All kids, yes, but, and this is very important, largely girls—How to code because the coding education happened incidentally, outside the pipelines where people are told what they can and can’t do [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/mspowahs/status/1032738596992606209

- AKIRA THE DON. [@akirathedon]. (2018, August 17). Sweet, smiling Tom Never deleted a post Never suspended an account Never rearranged a timeline You gave us everything and we forsook you ☺ [Tweet]. https://t.co/KyVJHlGD1w; https://twitter.com/akirathedon/status/1030495910386515969

- Albanesius, C. (2009, 16 June). More Americans go to Facebook than Myspace. PC Mag. https://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,2817,2348822,00.asp.

- Ames, M. G. (2019). The charisma machine: The life, death, and legacy of one laptop per child. MIT Press.

- Anil Dash. [@anildash. (2018, November 9). Because the tech industry fought like hell to erect barriers against platforms like MySpace & Neopets that were letting underrepresented folks actually *make* the web instead of just consuming it. [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/anildash/status/1060754945434157056

- BBC News. (2006, 7 December). Myspace to “block sex offenders”. Retrieved March 1, 2021, from http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/technology/6216736.stm.

- Benjamin, R. (2019). Race after technology: abolitionist tools for the New Jim Code. Polity Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soz162

- Big Elly. [@mdeeeeee_]. (2019, October 14). Someone said Myspace stopped being popular because black and brown kids started to learn how to code and got good and they couldn’t have that and I think about that a lot [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/mdeeeeee_/status/1183527253323505664

- Blerds Online. [@BlerdsOnline]. (2019, December 28). Shout out to Tom from Myspace. Homie cashed his check, and bounced. He never tried to influence elections, be an advocate for “free speech”, purchase competitors, sell our information or any of that. Just taught us all some basic HTML and rolled out [Tweet]. https://t.co/PCZdUJhGtP; https://twitter.com/BlerdsOnline/status/1210776410295422978

- bletchley punk. [@alicegoldfuss]. (2018, November 9). People like to shit on LiveJournal, but having one inspired me to learn:—HTML/CSS—hex code (for picking theme colors)—How to make animated gifs—Image compression—Basic webhosting—Basic security—A ton of Photoshop—Content & community [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/alicegoldfuss/status/1060963295090200576

- Bobkowski, P. S., Brown, J. D., & Neffa, D. R. (2012). “Hit Me Up and We Can Get Down”: US youths’ risk behaviors and sexual self-disclosure in MySpace profiles. Journal of Children and Media, 6(1), 119–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2011.633412

- Bolin, G. (2016). Passion and nostalgia in generational media experiences. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 19(3), 250–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549415609327

- boyd, d. (2013). White flight in networked publics: How race and class shaped American teen engagement with Myspace and Facebook. In L. Nakamura & P. A. Chow-White (Eds.), Race after the internet (pp. 203–222). Routledge.

- Boym, S. (2007). Nostalgia and its discontents. The Hedgehog Review: Critical Reflections on Contemporary Culture. Summer 2007. [Online]. Retrieved February 26, 2021, from https://hedgehogreview.com/issues/the-uses-of-the-past/articles/nostalgia-and-its-discontents.

- Boym, S. (2001). The future of nostalgia. Basic Books, Inc.

- Campbell, I. C. (2021, 27 January). YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook continue bans over Trump election claims. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2021/1/27/22251338/twitter-facebook-youtubeelection-misinformation-ban-trump.

- Cashmore, P. (2006, 11 July). Myspace, America’s number one. Mashable. https://mashable.com/2006/07/11/myspace-americas-number-one/?europe=true#7X596_tOZ5qR.

- Codecademy. (2020, 14 February). Myspace and the coding legacy it left behind. https://news.codecademy.com/myspace-and-the-coding-legacy/.

- Cole, S. (2018, December 4). Actually, myspace sold your data too. Vice. https://www.vice.com/en/article/43bbbn/myspace-tom-viant-time-inc-facebook-cambridge-analytica

- Davies, H. C., & Eynon, R. (2018). Is digital upskilling the next generation our ‘pipeline to prosperity’? New Media & Society, 20(11), 3961–3979. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818783102

- Dredge, S. (2015, 6 March). Myspace—what went wrong: “The site was a massive spaghetti-ball mess”. The Guardian. Retrieved March 1, 2021, from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/mar/06/myspace-what-went-wrong-sean-percival-spotify.

- Driscoll, K., & Walker, S. (2014). Working within a black box: transparency in the collection and production of Big Twitter Data. International Journal of Communication, 8, 1745–1764.

- Fogel, J., & Nehmad, E. (2009). Internet social network communities: Risk taking, trust, and privacy concerns. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(1), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2008.08.006

- Gabbatt, A. (2011, December 30). Myspace Tom to Google+: Don’t become a cesspool like my site. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2011/dec/30/myspace-tom-google-censorship

- Gallant, L. M., Boone, G. M., & Heap, A. (2007). Five heuristics for designing and evaluating web-based communities. First Monday, 12(3). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v12i3.1626

- Gerrard, Y. (2018). Beyond the hashtag: Circumventing content moderation on social media. New Media & Society, 20(12), 4492–4511. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818776611

- Gerrard, Y. (2020). What’s in a (pseudo)name? Ethical conundrums for the principles of anonymisation in social media research. Qualitative Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794120922070

- Gibson, W. J., & Brown, A. (2009). Working with qualitative data. Sage.

- Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the internet: Platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media. Yale University Press.

- Greene, D. (2021). The promise of access: Technology, inequality, and the political economy of hope. MIT Press.

- Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2012). Applied thematic analysis. Sage.

- Harvey, D. (2003). The fetish of technology: Causes and consequences. Macalester International, 13(1), 7.

- Heinrich, S. (2021, April 19). A Gen Z’er created a replica of the OG myspace, and it’s blowing my mind. BuzzFeed. Retrieved June 21, 2021, from https://www.buzzfeed.com/shelbyheinrich/spacehey-myspace-og-replica

- Hine, C. (2015). Ethnography for the internet: Embedded, embodied and everyday. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Janjigian, L. (2016). Here’s why some women in tech cite MySpace as their entry point. Business Insider. Retrieved June 24, 2021, from https://www.businessinsider.com/women-in-tech-myspace-2016-12

- Jones, S., Millermaier, S., Goya-Martinez, M., & Schuler, J. (2008). Whose space is Myspace? A content analysis of Myspace profiles. First Monday, 13(9). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v13i9.2202

- JP. [@JUNGLEPUSSY]. (2018, November 6). WHY DID I STOP CODING AFTER MYSPACE [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/JUNGLEPUSSY/status/1059878929752883201

- Kailah. [@kailah_casillas]. (2019). August 19). Remember when we all learned how to code so that we could personalize our Myspace pages? I should have stuck with that I’d probably be rich by now [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/kailah_casillas/status/1163536806630973440

- Kennedy, H. (2016). Post, mine, repeat: Social media data mining becomes ordinary. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Khaled, A. (2019, 7 August). The kids are learning video editing from TikTok. OneZero. Retrieved February 27, 2021, from https://onezero.medium.com/the-kids-are-learning-video-editing-from-tiktok-a84bafc56021.

- Lingel, J. (2021). The gentrification of the internet: How to reclaim our digital freedom. University of California Press.

- Lohr, S. (2015, July 29). As tech booms, workers turn to coding for career change. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/29/technology/code-academy-as-career-game-changer.html

- Markham, A. (2012). Fabrication as ethical practice: Qualitative inquiry in ambiguous internet contexts. Information, Communication and Society, 15(3), 334–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2011.641993

- Marwick, A. E. (2008). To catch a predator? The MySpace moral panic. First Monday, 13(6), https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v13i6.2152

- Matamoros-Fernández, A., & Farkas, J. (2021). Racism, hate speech, and social media: A systematic review and critique. Television & New Media, 22(2), 205–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476420982230

- Miller, V. (2017). Phatic culture and the status quo: Reconsidering the purpose of social media activism. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 23(3), 251–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856515592512

- Miltner, K. M. (2019). Anyone Can Code? The Coding Fetish And The Politics Of Sociotechnical Belonging [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. University of Southern California.

- Mims, C. (2010, July 14). Did Whites Flee the ‘Digital Ghetto’ of MySpace? MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2010/07/14/202026/did-whites-flee-the-digital-ghetto-of-myspace/

- Moreno, M. A., Parks, M. R., Zimmerman, F. J., Brito, T. E., & Christakis, D. A. (2009). Display of health risk behaviors on MySpace by adolescents: Prevalence and associations. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 163(1), 27–34.

- Moreno, M. A., Parks, M., & Richardson, L. P. (2007). What are adolescents showing the world about their health risk behaviors on MySpace? Medscape General Medicine, 9(4), 9.

- Ngo, H. (2021, 8 January). Here’s why Donald Trump has “Myspace” trending on Twitter. The List. Retrieved March 1, 2021, from https://www.thelist.com/309751/heres-why-donald-trump-has-myspace-trending-on-twitter/.

- Niemeyer, K. (2014). Media and nostalgia: Yearning for the past, present and future. Palgrave Macmillan.

- NUFF. [@nuffsaidny]. (2020, July 14). Myspace had everybody coding in HTML, CSS & JavaScript. Tom had us all doing front-end web development [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/nuffsaidny/status/1283032175726690308

- Oriana Nichelle. [@OrianaNichelle]. (2021, January 8). it’s 2006, i’m logged into Myspace, my basic coding skills are only impressive to myself, i’ve just completed a survey that asked if i had crush, i put “maybe” in hopes my crush will see. Simpler times [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/OrianaNichelle/status/1347348806950481920

- Perkel, D. (2008). Copy and paste literacy? Literacy practices in the production of a Myspace profile. In: K. Drotner, H.S. Jensen & K. C. Schroder (Eds.), Informal learning and digital media (pp. 203–224). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Petersen, A. H. (2021, May 23). The Millennial Vernacular of Fatphobia. Culture Study. https://annehelen.substack.com/p/the-millennial-vernacular-of-fatphobia

- Pickering, M., & Keightley, E. (2006). The modalities of nostalgia. Current Sociology, 54(6), 919–941. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392106068458

- Pinch, T., & Reinecke, D. (2009). Technostalgia: How old gear lives on in new music. Sound Souvenirs: Audio Technologies, Memory and Cultural Practices, 2, 152.

- Press, G. (2018, 8 April). Why Facebook triumphed over all other social networks. Forbes. Retrieved March 1, 2021, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/gilpress/2018/04/08/why-facebook-triumphed-over-all-other-social-networks/?sh=9909d386e918.

- Reuters. (2007, 24 July). Myspace deletes 24,000 sex offenders. Retrieved March 1, 2021, from https://www.reuters.com/article/domesticNews/idUSN2424879820070724?feedType=RSS&rpc=22&sp=true.

- Schwarz, O. (2009). Good young nostalgia: Camera phones and technologies of self among Israeli youths. Journal of Consumer Culture, 9(3), 348–376. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540509342045

- Solon, O. (2018, 6 June). Meet the people who still use Myspace: “it’s given me so much joy”. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/jun/06/myspace-who-still-uses-social-network.

- Srnicek, N. (2017). Platform capitalism. John Wiley & Sons.

- Stark, S. (2021, February 5). Framing Britney Spears. [Documentary].

- Tannock, S. (1995). Nostalgia critique. Cultural Studies, 9(3), 453–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502389500490511

- The Media Manipulation Casebook. (n.d.). Retrieved March 1, 2021, from https://mediamanipulation.org/.

- The White House. (2012, July 25). Fact Sheet: Creating pathways to the middle class for all americans. Whitehouse.Gov. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2012/07/25/fact-sheet-creating-pathways-middle-class-all-americans

- Tiidenberg, K., Hendry, N. A., & Abidin, C. (2021). Tumblr. Polity.

- Tsotsis, A. (2011, 11 July). Sean Parker on why Myspace lost to Facebook. TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2011/06/28/sean-parker-on-why-myspace-lost-to-facebook/.

- Twitter. (2020). Display requirements: Tweets. Retrieved February 4, 2020, from https://developer.twitter.com/en/developer-terms/display-requirements.

- Williamson, B. (2015). Programming power: Policy networks and the pedagogies of ‘learning to code. In A. Kupfer (Ed.), Power and education (pp. 61–87). Springer.

- Williamson, B. (2016). Political computational thinking: Policy networks, digital governance and ‘learning to code. Critical Policy Studies, 10(1), 39–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2015.1052003

- Williamson, B., Bergviken Rensfeldt, A., Player-Koro, C., & Selwyn, N. (2019). Education recoded: Policy mobilities in the international ‘learning to code’ agenda. Journal of Education Policy, 34(5), 705–725. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2018.1476735