Abstract

Stadium districts are almost always located in central cities. One exception, and the focus of this study, is Truist Park–Battery Atlanta, a $1.3-billion baseball stadium development that opened in a suburb outside Atlanta, Georgia, in 2017. Empirical material collected from 134 active voters was used to analyze the perceived impact of the stadium development on the region and consider whether public opinion in this case contrasted with questions traditionally raised in cities affected by urban stadium projects. Nineteen preliminary codes and six categories emerged from a combined approach to qualitative analysis. The primary themes were established a priori based on the goal of identifying both universal and regional attributes. The results provide evidence that public interest in stadium projects may transcend proximity to the urban core, thereby suggesting many—although not all—concerns are universal.

1. Introduction

Today, the constructing of professional sports stadiums (i.e. arenas, ballparks, stadiums) in central city areas is commonplace: across Major League Baseball (MLB), the National Basketball Association (NBA), the National Hockey League (NHL), and the National Football League (NFL), the average distance between a team’s competition venue and the city center is 5.6 miles, 1.7 miles, 3.9 miles, and 7.4 miles, respectively.Footnote1,Footnote2 Furthermore, at least half of all stadiums in MLB (50%), the NBA (83%), and the NHL (74%), and nearly half of all NFL (45%) stadiums, are 2.5 miles or less from their city centers. The proximity of most of North America’s major professional sports stadium to central city spaces suggests team owners, local policymakers, and other stakeholders find value in the urban core, even if that means reckoning with higher land costs, smaller building footprints, higher density neighborhoods, more complex parking and transportation challenges, or imperfect construction conditions (e.g. soil contamination, flood susceptibility).

While the majority of recently constructed stadiums (and associated sports and entertainment districts) are centrally located, there are a few notable exceptions. One such case is Truist Park (previously known as SunTrust Park), the $722-million home of the Atlanta Braves that opened in Cumberland, Georgia, in 2017 (Center for Sport and Urban Policy, Citation2020). Cumberland is an unincorporated suburb about 13 miles north of the team’s former stadium, Turner Field, which opened as a ballpark in downtown Atlanta in 1997. Like other projects leveraging stadiums as catalysts for growth in large downtown commercial and residential hubs, Truist Park anchored a new mixed-use development called The Battery Atlanta; however, this project differed from other stadium districts because it was built on a 60-acre tract of undeveloped land outside Atlanta’s “intown” boundary and well beyond the city’s three most prominent commercial areas (i.e. Downtown, Midtown, Buckhead).

The Braves’ move from its downtown, central location to a new site on the outskirts of the central city was a clear reversal of nearly 30 years of suburb-to-metropolitan stadium migration across North American cities (Rosentraub, Citation2014). The announcement of the Braves’ move caught many in the metro area by surprise, including both intown Atlantans and residents of Cobb, the county in which Cumberland is located, and the source of a $392-million subsidy being used to fund the stadium development. Cobb residents did not directly vote on the subsidy, and polling suggested that while over half of voters favored the plan, 78% would have preferred a referendum on the issue (Tierney, Citation2014). Although it diverged from other stadium projects originating in major metropolitan centers, the Truist Park–Battery Atlanta development paralleled many urban stadium projects because of its aim to use a sports stadium to drive economic growth at a larger, master-planned entertainment district. Unlike traditional urban stadium plans, however, the Cobb ballpark project was designed to concentrate spending outside of the metro Atlanta area, a direct outcome of Cobb policymakers’ successful negotiations (and Atlanta city officials’ failed efforts to come to an agreement) with the Braves to construct a new stadium.

In light of this distinction, the purpose of this study is to examine whether the attitudes of citizens impacted by a suburban stadium district differ from those impacted by stadium projects sited in more usual urban centers. Such research may serve the literature in several ways. First, it may complement previous literature by underscoring contextual differences between both stadium cases and the cities and regions in which the stadiums exist (Santo, Citation2005). Second, in cases where a proposed stadium subsidy is not directly approved by voters, this line of research may be used to evaluate whether legislators’ decisions are congruent with the public will (Kellison & Mills, Citation2020). Third, for a stadium being built in a new market (e.g. in the suburbs, in a new city entirely), such data may be important for stadium tenants as they forecast business opportunities and threats. In the case of a stadium district planned in an atypical location, those investing in the project must not only consider the need to maximize gameday attendance, but also endeavor to sustain public interest and spending in the broader district during non-gamedays and during the offseason.

Each of the aforementioned features may be observed in the Truist Park–Battery Atlanta case: the stadium project was subsidized without the direct vote of citizens, it was constructed in a location far from the Braves’ previous ballpark, and it was designed as the centerpiece of a new commercial and residential suburban hub. These peculiarities separate the Atlanta case from its more urban counterparts. This study explores whether these unique characteristics engender a similarly distinct public response. Consistent with the approach of previous research in this space, in the next section, the study is conceptually framed by (1) earlier work in urban studies and urban planning and (2) the contextual background of the Truist Park–Battery Atlanta case.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Stadium Districts and Neighborhood Development

Since the late 1980s, professional sports stadiums across North America have mostly been situated in the urban core. (Conversely, by and large, European stadium projects have not followed this spatial trend) (cf. Bale, Citation2003; Barghchi et al., Citation2009) In many cases, these facilities have been built in city centers, former industrial sites, or other underutilized metropolitan spaces with the intent of spurring economic activity, boosting urban populations, or anchoring new sports and entertainment districts (Chapin, Citation2004). This planning strategy is in stark contrast to the geographic approach of the 1950s–1970s, a period marked by suburban and exurban stadium construction that offered closer proximity to new home communities, greater highway connectivity, and more abundant parking (Suchma, Citation2005). This trend coincided with the postwar outflow of middle-class families from urban neighborhoods to suburban communities (i.e. “white flight”) (Goldberger, Citation2019; Rosentraub, Citation2010).

A growing number of stadiums are being built as part of larger districts that may include residential, office and retail, dining, and entertainment space (e.g. Arena District in Columbus, The District Detroit). These new “service consumption centers” may concentrate local spending in a designated city zone, which explains why they are often planned in areas intended for revitalization by planners and developers (Humphreys & Zhou, Citation2015). As chronicled in a 2018 New York Times article, as sports teams are moving back from suburban regions, mixed-use developments are becoming more common in city centers:

Across the country, in more than a dozen cities, downtowns are being remade as developers abandon the suburbs to combine new sports arenas with…residential, retail and office space back in the city. The new projects are altering the financial formula for building stadiums and arenas by surrounding them not with mostly idle parking lots in suburban expanses, but with revenue-producing stores, offices and residences capable of serving the public debt used to help build these venues. (Schneider, Citation2018, p. BU3)

The presence of professional sports stadiums can reflect cities’ or regions’ efforts to “differentiate themselves in an increasingly competitive global marketplace” (Mason et al., Citation2015, p. 539). This political and economic strategy has not been limited to global cities and major metropolitan areas, however. In small and mid-sized cities, officials have adopted similar models of urban development (Soebbing et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, in some cases, the attractiveness of stadiums as tools of economic growth has reignited debate between central cities and their inner- and outer-ring suburbs to retain (or relocate) professional sports teams and their associated developments. For instance, Turner and Rosentraub (Citation2002) observed “…in the Sunbelt areas of Atlanta, Dallas, Houston, Los Angeles, and Phoenix, suburban areas, exurban centers, and fringe cities began to compete for every event, venue, corporate location, and economic activity with their older center cities” (p. 487). This city–suburb competition is exemplified in the case of Atlanta, as discussed in the following section.

2.2. Intra-Metropolitan Rivalry in Atlanta, Georgia

2.2.1. Suburban Growth in a Sprawling City

With more than 5.8 million inhabitants, Atlanta is the ninth most populous metro area (formally the Atlanta–Sandy Springs–Roswell, GA Metropolitan Statistical Area; MSA) in the United States, and in 2018, it was the third largest-gaining MSA (U.S. Census Bureau, Citation2018). The city of Atlanta is estimated to have just over 465,000 residents, further indicating Atlanta’s robust suburban population (U.S. Census Bureau, Citation2017). A report by Smart Growth America (Citation2014) named Atlanta the most sprawling large metro area in the US based on development density, land use mix, activity centering, and street accessibility. As Joseph Hurley chronicled in his 2016 essay on Atlanta’s past urbanization efforts, many of the causes of suburban sprawl were intentionally put into place by city planners:

…Urban residential neighborhoods were consumed by a planning ideology that convinced nearly all segments of American society that car-focused and compartmentalized land use development in both suburban and urban areas were common sense. This ideology also convinced the American public that density and commercial activity, even small corner stores, within residential neighborhoods were fundamentally problematic. In the decades after World War II, Atlanta lost many of its urban neighborhoods to this development ideology, which can be understood as a war on density. While some elements of this development mindset seem to be fading as mixed-use development now appears to be desirable, it still holds immense influence on how urban space in Atlanta is configured. (para. 2)

The war on density described above fueled Atlanta’s strategy of rapid annexation, an effort that then-unincorporated areas like Sandy Springs and Cobb County aggressively fought. For example, in the 1960s, Cobb legislators chartered a new city, Chattahoochee Plantation, stretching along the county’s border with Atlanta and neighboring Fulton County (Stokes, Citation2015). In some places, Chattahoochee Plantation’s city limits were a mere 10 feet across, signaling Cobb’s opposition to annexation by effectively forming a barrier between itself and Atlanta. In later years, some suburban communities pursued cityhood—the incorporation of a new city—a trend that continues today. For many of these communities, the appeal of cityhood is the ability to control tax collection and revenue allocation, allowing policymakers to “reprioritize and increase services to meet the needs of their more homogeneous constituencies without raising taxes” (Rosen, Citation2017, para. 4). As more communities pursue cityhood, “metro Atlanta is fracturing along invisible walls surrounding its young suburban cities” (Niesse, Citation2015, p. A1).

In Cobb, demographic changes indicate the county is becoming more racially diverse and less politically conservative (Emerson, Citation2017). It has also proven to be an appealing setting for major corporations including thyssenkrupp Elevator, Lockheed Martin, The Weather Channel, RaceTrac, Six Flags, Synovus, and Yamaha, all of which have established headquarters in the county. Cobb has also attracted business away from the city of Atlanta, including the Atlanta Ballet and Atlanta Opera; both moved operations from Midtown to the Cobb Energy Performing Arts Centre, a 2750-seat, $145-million venue that opened in 2007 (Brett, 2013). One of Cobb’s newest and most prominent tenants is the Atlanta Braves, the major league baseball team that relocated from downtown Atlanta to suburban Cobb in 2017. This move is summarized below.

2.2.2. Truist Park–Battery Atlanta

When they relocated from Milwaukee in 1966, the Braves played in downtown Atlanta in Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium (originally Atlanta Stadium). Following the Centennial Olympic Games in 1996, they moved across the street to the former Olympic Stadium, newly reconfigured and renamed Turner Field. Then, in November 2013, the team made the surprising announcement of their plans to construct a new ballpark in Cobb, a suburban county north of downtown that would be open in time for the 2017 baseball season. Acknowledging Turner Field was less than 20-year old at the time of the announcement, Braves officials cited several reasons for the move. First, Turner Field required costly infrastructure improvements, and the existing site presented traffic and parking issues. Second, a large concentration of ticket buyers lived in the northern suburbs and exurbs, and the new site would put the Braves closer to their core consumer base. Third, the team lacked ownership of the land and properties around the Turner Field footprint, making it difficult for them to advance any initiatives to commercialize the area around the stadium. Relatedly, the high cost and complexity of acquiring additional land in the metro area may have led the Braves to pursue alternative sites.

The absence of control downtown made a move to Cobb especially appealing, as the lack of development around the new site, coupled with the large acreage of the parcel, allowed the Braves to invest in a sizable, mixed-use project anchored by the new ballpark. From a regional perspective, this move re-concentrated spending from one section of the MSA to another, limiting the economic impact on the region; conversely, the team’s real-estate investment represented a new source of revenue for the Braves. In addition to the 41,000-seat stadium, the Battery Atlanta development added a concentration of retail, dining, and office space; a 4000-seat concert venue; a luxury hotel; and several apartment complexes. The total cost of Truist Park was estimated to be $722 million, $392 million of which was subsidized by the county, the Cumberland community improvement district, and the county building authority (Liberty Media Corporation, Citation2017). The estimated cost of The Battery Atlanta was $558 million; the Braves were expected to fund $470 million, while the remainder was financed by other private partners. In sum, total investment in the stadium district exceeded $1.3 billion.

At the center of the plan for the Cobb ballpark district was Tim Lee, then-chairperson of the Cobb County Board of Commissioners. Lee quarterbacked the public financing plan, which was approved 4–1 just two weeks after the Braves’ move was made public (Leslie & Tucker, Citation2013). The project was finalized six months later when county commissioners unanimously approved a group of legal agreements to close the deal. In both meetings, critics argued the project was planned hastily, the decision-making process lacked transparency, and voters should be consulted (Klepal & Schrade, Citation2014). In the absence of a public vote, it was unclear the extent to which Cobb residents supported or opposed the stadium plan. In 2016, Lee’s reelection was challenged by Mike Boyce, an outspoken critic of the Cobb ballpark deal and whose campaign focused largely on the lack of a public vote (Lutz, Citation2016). Lee was defeated soundly, and some voters indicated that although they were supportive of the Braves’ move to Cobb, they “objected to the way the deal was negotiated in secret and committed…public money to build and maintain a new stadium without a popular referendum” (Wickert & Lutz, Citation2016, p. A1).

The Truist Park project is unusual for several reasons. First, the ballpark replaced an existing venue less than 20-year old, raising questions about whether this relatively short lifespan would become a trend among professional sports facilities. Second, as discussed in the introduction, the location of the project outside the central city was uncharacteristic of the vast majority of major sports venues in North America. As shown in , Truist Park is 13.5 mi from the city center, the fourth-longest distance among Major League Baseball stadiums. When correcting for regional idiosyncrasies, no ballpark is further from its city center.

Table 1. Major League Baseball stadium distances to city centers.

Truist Park–Battery Atlanta shares many of the characteristics of the modern stadium district. While usually existing in the urban core, a stadium district situated outside the city center may have additional value by providing a suburban community with the opportunity to build upon its local culture. Despite this unique potential, Cobb residents may nevertheless view the project in the same light as others existing in central cities. Based on this possibility, two research questions (RQs) were developed to guide this inquiry:

RQ1: In what ways are public attitudes toward a proposed suburban stadium district consistent with findings of previous literature (e.g. local impact, tax worries, policymaker criticisms, the political process)?

RQ2: What unique public concerns, if any, may emerge regarding a proposed suburban stadium district?

3. Method

Based on this population of interest, a sample of residents from Cobb County was used. A simple random sampling technique was employed, and records were obtained from the Cobb County Board of Elections and Registration, which provided contact information (including name, address, year of birth, gender, race, voter registration date, and previous elections participated in) of 392,790 active voters. Each case was assigned a random number, and 4000 records were selected to receive survey packets. The packets included a cover letter, survey, and postage-paid reply envelope. Survey packets were mailed upon Institutional Review Board approval. A portion of the survey contained quantitative items that broadly focused on participants’ perception of the ballpark’s tangible and intangible benefits, trust in policymakers, support of the financing plan, team consumption intentions, belief the decision-making process was congruent with democratic norms, attitudes toward policymakers, and level of political apathy. As part of the survey’s design, space was included in which respondents could provide open-ended comments based on their attitudes toward the Truist Park–Battery Atlanta project. The comments returned by participants serve as the basis for this study. Returned responses were reviewed for completeness and relevance, and the empirical material was stored in NVivo 12.

The empirical material was analyzed using Blair’s (Citation2015) combined approach, a hybrid technique in which aspects of both grounded theory methodology (GTM) and template coding are applied. GTM typically consists of three coding stages: open, axial, and selective (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2015). First, in open coding, the researcher uses a bottom-up approach to identify key codes emerging from the text. Second, in axial coding, similar emergent codes are connected to form broader descriptors. Third, in selective coding, the categories are organized around core themes. Conversely, template coding involves applying a top-down approach to produce a list of codes (i.e. the template) representing themes often identified a priori (King, Citation2012). Blair (Citation2015) adopted a combined approach after observing neither a bottom-up nor top-down analytical method was optimal based on his stated research problem and the key literature. He encouraged other researchers to consider similarly customized approaches when appropriate. As Blair (Citation2015) explained, the combined approach reduces the likelihood of confirmatory bias, “as the bottom-up and top-down templates speak to, and counter, one another” (p. 26).

The two interests in this study—public opinion and the ways in which it is consistent with traditional stadium cases—necessitated distinct approaches to analyzing the empirical material. To investigate citizens’ attitudes, it was reasoned that an exploratory approach was preferable, as contextual differences in the Cobb case could yield results that differed from those reported in previous studies (e.g. Santo, Citation2005). Conversely, when comparing with previous research, the existing literature on the subject should be applied in the analysis stage. Thus, the approach to developing a data coding template was informed by Blair’s (Citation2015) combined method. First, the text was reviewed, and emerging codes were identified using open coding (GTM). Then, axial coding was employed to organize the preliminary codes into key categories (GTM). Finally, the categories were analyzed in relation to the literature, and they were arranged into thematic dimensions (template coding).

Following the recommendations of Saldaña (Citation2016) for solo coding, two colleagues familiar with the project were consulted throughout the coding process. Their support was utilized to troubleshoot dilemmas and evaluate the strength of connections made in the empirical material. Additionally, several triangulation approaches were employed to support the trustworthiness of the empirical material and subsequent presentation of results. First, although the quantitative data collected is outside the scope of this study, where applicable, descriptive statistics were reviewed to evaluate the extent to which they were general consistent with the preliminary codes, categories, and themes that emerged from the coding process. Codes, categories, and themes were also cross-referenced with more than 700 news articles published by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, the most widely circulated newspaper in the Atlanta MSA, to ensure the interpretation of the empirical material was consistent with general narratives associated with the stadium project.

The responses are presented using verbatim quotations. When the names of respondents are listed, pseudonyms are used, and the following additional descriptors are provided: age, hometown, political affiliation, and number of Braves games attended in the past five years (using 0, 1–5, 6–10, 11–15, and 16 or more as ranges).

4. Results and Discussion

Of the 369 surveys completed and returned, 134 contained written comments that were retained and analyzed for this study. The median age of respondents was 54.2, and the gender breakdown was 53% men, 47% women. The majority of respondents self-identified as White (80.6%), and more than 74% held a bachelor’s degree or higher. The median per capita income fell between $75,000 and $99,999. The political affiliation most often reported was Republican (43.4%), followed by independent or third party (31.8%), Democrat (15.5%), and other (9.3%). Lastly, over two-thirds of respondents reported attending 1–5 Braves games in the past five years. In , a demographic summary of the sample is provided and compared with all registered voters and all residents of Cobb County. In comparison with all Cobb residents, the sample is generally older, has more formal education, and is more affluent. Based on File’s (Citation2018) profile of demographic trends among U.S. voters, the differences between the average voter in this study and the average Cobb resident is somewhat expected. He found as citizen’s increase in age, levels of education, and earnings, the likelihood they are registered voters tends to increase.

Table 2. Demographic comparison of sample, county registered voters, and all county residents.

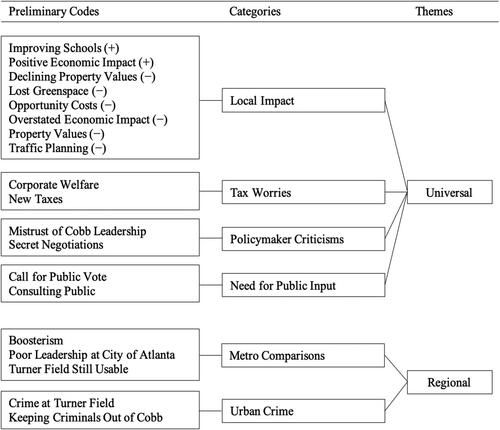

As illustrated in , analysis of the empirical material began with 19 preliminary codes, which were subsequently organized into six higher-order categories. Each category was then assigned to one of two a priori themes based on whether it reflected a universal, enduring concern or if it was a regional, emergent issue. These themes are discussed in turn below.

4.1. Universal and Enduring Questions about a Stadium District

RQ1 related to the ways in which public attitudes toward a suburban stadium project were consistent with those found in previous literature. Four broad categories reflect universal and enduring concerns that can be applied beyond this particular case. That is, concerns related to a project’s economic and non-economic benefits, taxes associated with the public funding of the project, elected policymakers, and the political process are all consistent with previously studied cases, and these categories could be expected to be found in subsequent research.

4.1.1. Local Impact

As expected, respondents demonstrated their vested interest in the prosperity of the community by celebrating events that could contribute to success and expressing concern for those that could cause harm. They identified several consequences of the proposed ballpark district, some positive and some negative. John, a 25-year-old Republican from Marietta who attended more than 15 Braves games over the past five seasons, emphasized the opportunity the Braves’ move to Cobb presented for the county:

This [project] will be a great investment for Cobb County. …There will be more traffic, but the issue is not incurable. However, declining this opportunity is incurable. There are 30 MLB teams. There are 3,100-plus counties in the US. You do the math. Is this an opportunity or a burden? I believe the answer is quite clear.

While many respondents expressed optimism about the proposed ballpark district’s ability to produce meaningful benefits for the people of Cobb, there was also some healthy skepticism. On the subject of job creation, Rachel (36, Acworth, third party, 1–5 games) stated, “Cobb isn’t necessarily a poor county, so their assessment that it will bring jobs seems like an excuse to build it. Not a valid reason.” Additionally, a few respondents challenged the claim that sports stadiums are sources of significantly positive economic impact, an argument that has been similarly challenged in recent research on Truist Park–Battery Atlanta (Bradbury, Citation2020).

Other respondents critical of the ballpark plan discussed its opportunity costs and offered some alternatives preferred over subsidizing the stadium, including education, a county asset that Connor (44, Marietta, Democrat, 6–10 games) felt was being neglected by Cobb policymakers:

We moved to Cobb County because they have some of the best public schools in the state. For several years now, the schools have been underfunded—increasing class sizes and laying off teachers. Education is more important to me than building a stadium for a sports team. Fund the schools—reduce class sizes, bring back art, music, and theatre, bring back the teachers. Give them pay raises and proper supplies. Bring technology to the schools. I am fine with the Braves moving to Cobb County but let them pay to build their own stadium.

Of the 19 preliminary codes identified from the empirical material, those connected to transportation and parking received the most coverage. Concerns that Cobb officials unnecessarily expedited the policymaking process (discussed further below) were substantiated by the lack of an appropriate traffic plan. Corinne (55, Vinings, Democrat, 1–5 games) explained:

I work downtown and see the game crowds. Significant numbers use mass transit. Mass transit plans have not been discussed. I [also] live near the site of the new stadium. Traffic is already at gridlock every single day during rush hour. I will not be able to get home from work during ball games due to traffic. Was the plan to drop off fans by helicopter?

4.1.2. Tax Worries

In any case involving public spending, the fear of increased taxes to support a civic project is expected. In anticipation of this voter anxiety, Cobb officials emphasized the fact that Cobb residents would not face higher taxes as a result of the ballpark project; in reality, public funding was sourced mainly from reallocated “property tax revenue currently used to pay off bonds issued to purchase parkland” (Leslie & Tucker, Citation2013, p. A1). Despite the promise of policymakers, many respondents anticipated an eventual increase in taxes or conveyed dissatisfaction with the reallocation of existing tax revenues. For instance, despite her enthusiasm for the Braves and their move to Cobb, Danielle, a 62-year-old third-party voter from Marietta who attended Braves games sparingly, opposed the use of public money to facilitate the project:

I have lived most of my life in Cobb County. I’ve been a Braves fan forever. Bringing the Braves to Cobb County is exciting but raising taxes to pay for a new stadium, making politicians ‘richer’ is not favorable to me or my neighbors.

The politicians in this county and a lot of residents (Tea Party!) pretend to be so anti-tax. But they are all for ‘corporate welfare.’ The commissioners ignored their Tea Party constituents. The deal was consummated behind closed doors, with little-to-no knowledge by the county citizens. …Very undemocratic.

4.1.3. Policymaker Criticisms

Some respondents expressed the desire to exercise their right to participate in the legislative process during the planning stages of the Cobb ballpark district. Multiple respondents expressed concern that policymakers’ plan to finance the ballpark was made in secrecy; references to the “undemocratic” process, “back door” agreements, and “smoke-filled” rooms were made on multiple occasions. That lack of transparency contributed to several respondents’ mistrust of the leadership in Cobb. For example, Jordan (57, Marietta, Democrat, 6–10 games) cited several aspects of the deal that negatively affected his attitude toward Cobb policymakers:

The lack of transparency during the decision making on [the] part of the commissioners, marginalizing the potential opponents of the ballpark, twisting of the facts that public funds will not be spent on the ballpark have contributed to my lack of trust in the Cobb County government.

I am not opposed to the Braves move to Cobb County. I am very opposed to the secrecy in which decisions were made. As a taxpayer and a voter, I should have been asked, not told, how my tax dollars are going to be spent.

4.1.4. Need for Public Input

In Cobb, some elected officials may have responded to respondents’ claims that they were not properly consulted during the planning stage by arguing that citizens already participated when they voted for their representatives in previous elections; by virtue of being voted into office, these officials were entrusted to govern in the best interests of their constituents (Kellison & Mondello, Citation2014). Conversely, some respondents argued that this particular case mandated additional public consultation via a referendum; this point is illustrated by Rachel, who contended, “We should be allowed to vote for this. I’m especially against it, but if the general public—especially those that live in the area—[is] ok with it, then I’m ok with it.”

Several Cobb residents expanded on this desire for a public vote, and responses ranged from bewilderment (e.g. “I don’t understand how something this large with respect to public tax dollars wasn’t put to a vote by Cobb County residents”) to anger (e.g. “The deal should never have been finalized without being presented to the voters for approval first.”). Additionally, several respondents specifically blamed Tim Lee, the Cobb commissioner behind the plan, and portended his eventual exit from public office. One respondent simply stated that she anticipated the public “to elect officials that encourage public input in [the] next election.” Rickey (20, Marietta, Republican, 0 games) echoed this point:

The citizens of Cobb County were victims of the corrupt county commissioners, particularly…Tim Lee. If a referendum had been held prior to this being a ‘done deal,’ I would not mind an outcome where the majority of voters agreed to fund the stadium. But Tim Lee, our corrupt chairman, was bought by the Braves and rushed this into place by hiding it from the public and then rigging the public comments period. I will vote against the current commissioners when I get a chance.

An emerging theme from this study is that many Cobb residents were conflicted about the value of the ballpark district. Even some who showed great enthusiasm for the plan and anticipated sizable benefits for Cobb expressed dismay at the apparent lack of a public process to inform the policymaking process. In other words, even those who were pleased with the outcome sought the opportunity to exercise their rights by participating in the process. This desire to participate was driven by several significant concerns, as summarized in the following section.

4.2. Regional and Emergent Concerns about the Truist Park–Battery Atlanta Development

RQ2 centered on the unique public concerns raised by local residents regarding the stadium district plan. The unique characteristics of this case—namely, the suburban location of the stadium district—yielded some context-specific results that differed from previous literature. First, some respondents offered distinctions between Cobb and the city of Atlanta. Second, some residents expressed concern about urban crime in metro Atlanta and the possibility it would follow the Braves to Cobb, a reprisal of a racist ideology that has persisted in Atlanta–Cobb affairs and U.S. urban politics more generally. These categories are considered regional, emergent concerns because they are considered atypical and represent significant issues relating specifically to the Truist Park–Battery Atlanta development.

4.2.1. Metro Comparisons

Even among those respondents skeptical of the project’s positive impact on Cobb, there was still recognition that the Braves could no longer be considered a purely “Atlanta” institution. As Jason (59, Powder Springs, no party affiliation, 1–5 games) argued, “The name should be changed to ‘Cobb Braves’. Forget ‘Atlanta’”; this “Cobb Braves” idea was a popular refrain among several respondents. This concept also underscores the city–suburb rivalry, which is illustrated in Cobb residents’ assessment of the city of Atlanta. Among the chief arguments against the city was that it suffered from poor leadership; even among Cobb residents who favored the Braves’ move, there was some sense that Atlanta’s mayor and city officials should have “worked harder” and “made a strong public effort” to keep the Braves in the city.

Many of the respondents who supported the ballpark district displayed boosterism when it came to the expected impact on Cobb. For example, Joe, a 54-year-old third-party voter from Marietta who frequently attended Braves games downtown, emphasized the pride he felt from the team’s move to Cobb:

You have no idea the pride I feel when my Braves will be arriving soon in Cobb County. The majority of fans that attend the Atlanta sports events are from the great county of Cobb! The travel distance is not much less, but the pertinent fact is ‘the Braves are Cobb County’s!’

I believe the new ballpark will bring a lot of new business to the area. I lived in Houston when the Astros built the new ballfield. There was a huge increase in attendance and the amount of pride for Houston and the Astros.

Closely tied to concerns about the near-$400-million public investment were questions about the wisdom of abandoning an existing ballpark less than 20 years old. In Sarah’s (49, Marietta, Democrat, 1–5 games) view, replacing a still-functional Turner Field was a poor public investment:

It really is quite a shame and a huge waste of taxpayers’ money to build a new Braves stadium. …Turner Field is beautiful and is designed with every comfort for the fans in mind. There really is no need for a new stadium other than to cost fans, and taxpayers, more money.

Turner Field was more than adequate! Congestion, both traffic and human, are extremely high in this new area already. Local leaders are more interested in their own best interests, which is the norm in politics. Very bad idea to tear down more raw land in an already overly-congested location to put up a new ballpark and leaving an empty venue/complex in an already depressed area.

4.2.2. Urban Crime

Nowhere were the perceived differences between the city of Atlanta and Cobb made more evident than in respondents’ discussion of crime. In media coverage of the Braves’ decision to relocate from Turner Field to Cobb, some analysts presumed the move was based, in part, on the perception that fans were deterred from attending games at Turner Field because of the threat of crime and violence (Crasnick, Citation2013). In this study, some respondents cited crime in the surrounding areas of Turner Field as the reason they did not attend games in the city, and others expressed serious concerns that the new stadium would result in increased crime in Cobb. A quotation from Kristina, a 62-year-old Marietta native with no party affiliation, exemplifies this apprehensiveness:

I quit going to Braves games because of safety issues. I abhorred the parking areas, crime-ridden streets, and overall ‘minority’ attitude. I fear bringing the Braves to Cobb…may also bring more crime and undesirable sorts that seem to be drawn to crowds.

These explicit and implicit expressions of racism reflect the historical social tensions between urban Atlanta and suburban Cobb, tensions that may be shifting as the county diversifies, as discussed by Lutz and Brasch (Citation2017) in an Atlanta Journal-Constitution report:

…The stadium and surrounding mixed-use development also represent changes that have slowly erased some of the divisions that once separated Cobb County, long regarded as a white-flight bedroom community, from the city of Atlanta. Truist Park is both cause and effect of the county’s increasing urbanization as a new generation of affluent, diverse and educated young professionals seek to combine the amenities of a city with the comforts of the suburbs. …

It also reignited old arguments about public transportation, policing and development that have historically been fraught with racial and political overtones in a county that was home to the state’s last openly segregationist governor, Lester Maddox, for whom the I-75 bridge from Atlanta to Cobb is named. (p. A1)

The morons running the county will use this as an opportunity to extend MARTA into Cobb County. Public transportation into Cobb will bring public nuisance from Atlanta. Crime will rise after the stadium is built and public transportation is in place.

As this section has shown, the Cobb ballpark plan provided citizens with the opportunity to consider what a major stadium initiative would mean for the Cobb community. Respondents expressed a wide range of opinions toward the proposed ballpark district, and there was no obvious agreement about its favorability or unfavorability. Still, there was a general concern that residents’ right to participate in the decision-making process was not recognized by Cobb policymakers.

In summary, the plan to construct a suburban ballpark district provided an environment (built and hypothetical) for citizens in the Cobb community to express their civic identity. Individuals demonstrated their membership by identifying positive and negative consequences of the ballpark plan exclusive to Cobb; additionally, they made comparisons with the central city, providing evidence that Cobb’s civic identity was indeed different from the city of Atlanta. Furthermore, respondents desired to express their right to participate in the planning process by calling for a referendum, threatening to vote out policymakers responsible for the plan, and stressing concerns related to taxes and traffic. In the concluding section, the implications of the study are discussed. The article closes with a statement of limitations and directions for future research.

5. Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to examine whether citizens’ concerns toward a suburban stadium project differed from those associated with more traditional urban venues. As the results showed, concerns raised by citizens toward a suburban sports venue (prospective or built) are, in many ways, consistent with other urban stadium projects, although some emergent issues are indeed place-dependent. While many of these pressures relate to economics, others center on deep-rooted political and social tensions found in major U.S. cities.

The Truist Park–Battery Atlanta development was noteworthy for several reasons, including its distant location from the central city. Also considered in this study was the district as a space for building culture and human capital. This perspective is important, as Bacot (Citation2008) explained, “Place and setting, both historically and geographically, appear to be significant features for understanding a community’s culture” (p. 413). Moreover, this study responded to Buckman and Mack (Citation2012) call for research on stadium projects in sprawling metropolitan areas.

The results of the study indicate residents in Cobb appraised the ballpark district plan both within the context of their civic identity and thinking about Cobb’s place in the greater Atlanta MSA. Although there was some excitement about the Braves’ move to the suburbs, there was also considerable apprehension about the project’s impact on the county. Even among citizens who favored the move, questions remained whether their right to participate in the decision-making process was circumvented.

The results of the study provide evidence that the issues contained in the categories of local impact, tax worries, policymaker criticisms, and need for public input are enduring; that is, they are likely stable and consistent regardless of context. In that sense, organizations considering similar moves to the suburb can expect to face the same public concerns than if they were staying in the central city. Conversely, the emergent categories associated with metro comparisons and urban crime are less common, and the transferability of these issues to other stadium-related cases is uncertain. These two categories underscore the perceived differences (and competitiveness) between some suburban cities and metropolitan centers. Some participants made clear contrasts between Atlantans and Cobb residents, particularly in their comments about crime and safety. Interestingly, some of these concerns (e.g. urban crime, traffic) mirror the perceived problems that prompted postwar suburbanization in the United States.

This study contributes to a more robust conceptual understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. To guide researchers building on this study, several limitations are acknowledged. First, when compared with all registered voters in Cobb and all Cobb residents, the sample was generally older, had more formal education, and had higher incomes; the sample also had an inverted gender ratio. Furthermore, it is likely the sample was made up mostly of individuals with at least some understanding of the proposed ballpark development. Conversely, nonrespondents may have been unaware of or lacked interest in the plan. Therefore, it may be necessary to adopt alternative research methods to attract the participation of apathetic voters. Similarly, the population of interest could be expanded to include citizens who were not registered as voters. Additionally, some responses may have been primed by the content that preceded the open-ended comment section (e.g. tangible and intangible benefits, trust in and attitudes toward policymakers, belief the decision-making process was transparent). Finally, the survey was administered in the months that followed the initial announcement of the Cobb plan; that is, citizens’ attitudes were measured during the initial stages of construction. Now that Truist Park and The Battery Atlanta are fully operational, further investigation might yield different perspectives on the ballpark district and the political, economic, and social aspects that define a community.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Timothy Kellison

Timothy Kellison (Ph.D., Florida State University, USA) is an Associate Professor and Director of the Center for Sport and Urban Policy at Georgia State University, USA. His research focuses on sport in urban environments, with special emphasis in sport ecology and urban and regional planning. His work has appeared in such journals as the Journal of Sport Management, Sport Management Review, and European Sport Management Quarterly.

Notes

1 Distance is the shortest driving distance computed using the Google Maps navigational tool. City center is determined by the location of a city’s primary municipal government building (e.g. city hall, city council chambers). Each team’s assigned city is based on: (1) team name (e.g. Pittsburgh Penguins: Pittsburgh), (2) city with population of at least 250,000 in which the sports facility is located (e.g. Golden State Warriors: Oakland), or (3) metropolitan statistical area in which the facility is located (e.g. New England Patriots: Boston). For MLB ballparks, when adjusting for alternate city assignment (i.e. Los Angeles Angels: Anaheim replaces Los Angeles; Texas Rangers: Arlington replaces Dallas; Tampa Bay Rays: St. Petersburg replaces Tampa), average distance is 3.5 miles. For NFL stadiums, when adjusting for alternate city assignment (i.e. Dallas Cowboys: Arlington replaces Dallas; San Francisco 49ers: Santa Clara replaces San Francisco; Arizona Cardinals: Glendale replaces Phoenix), average distance is 5.3 miles. For NHL arenas, when adjusting for alternate city assignment (i.e. Florida Panthers: Sunrise replaces Miami; Arizona Coyotes: Glendale replaces Phoenix), average distance is 2.3 miles. Full dataset available at stadiatrack.org/distance.

2 In metric units, MLB: 9.0 km, 5.6 km adjusted; NBA: 2.7 km; NHL: 6.2 km; 3.7 km adjusted; NFL: 11.9 km, 8.5 km adjusted.

References

- Bacot, H. (2008). Civic culture as a policy premise: Appraising Charlotte’s civic culture. Journal of Urban Affairs, 30(4), 389–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.2008.00405.x

- Bale, J. (2003). Sports geography (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Barghchi, M., Omar, D., & Aman, M. S. (2009). Cities, sports facilities development, and hosting events. European Journal of Social Sciences, 10(2), 185–195.

- Blair, E. (2015). A reflexive exploration of two qualitative data coding techniques. Journal of Methods and Measurement in the Social Sciences, 6(1), 14–29. https://doi.org/10.2458/v6i1.18772

- Bradbury, J. C. (2020). The impact of sports stadiums on localized commercial activity: Evidence from a business improvement district. SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3647552

- Brett, J. (2013, November 12). Arts groups: Move to Cobb good for business. Atlanta Journal-Constitution, A5.

- Buckman, S., & Mack, E. A. (2012). The impact of urban form on downtown stadium redevelopment projects: A comparative analysis of Phoenix and Denver. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 5(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2012.659071

- Center for Sport and Urban Policy. (2020). Publictrack. http://www.stadiatrack.org/public

- Chapin, T. S. (2004). Sports facilities as urban redevelopment catalysts. Journal of the American Planning Association, 70(2), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360408976370

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). SAGE Publications Inc.

- Crasnick, J. (2013, November 11). Braves set up for a brighter future. ESPN. http://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/9961921/atlanta-braves-making-wise-decision-departing-turner-field

- Emerson, B. (2017, April 30). Once a white bastion, county is nearing a racial tipping point. Atlanta Journal-Constitution, A1.

- Estep, T., & Wickert, D. (2019). MARTA expansion faces familiar fears. Atlanta Journal-Constitution, A1.

- File, T. (2018). Characteristics of voters in the Presidential Election of 2016. U.S. Census Bureau.

- Goldberger, P. (2019). Ballpark: Baseball in the American city. Alfred A. Knopf.

- Groothuis, P. A., Johnson, B. K., & Whitehead, J. C. (2004). Public funding of professional sports stadiums: Public choice or civic pride? Eastern Economic Journal, 30(4), 515–526. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40326145

- Humphreys, B. R., & Zhou, L. (2015). Sports facilities, agglomeration, and public subsidies. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 54, 60–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2015.07.004

- Hurley, J. A. (2016, February 3). Atlanta’s war on density. Atlanta Studies. https://www.atlantastudies.org/atlantas-war-on-density/

- Johnson, B. K., Mondello, M. J., & Whitehead, J. C. (2007). The value of public goods generated by a National Football League team. Journal of Sport Management, 21(1), 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.21.1.123

- Kellison, T., Kim, Y., & James, J. D. (2019). Secondary outcomes of a legislated stadium subsidy. Journal of Global Sport Management. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/24704067.2019.1604074

- Kellison, T., & Mills, B. M. (2020). Voter intentions and political implications of legislated stadium subsidies. Sport Management Review. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2020.07.003

- Kellison, T. B. (2016). No-vote stadium subsidies and the democratic response. International Journal of Sport Management, 17(3), 452–477.

- Kellison, T. B., & Mondello, M. J. (2014). Civic paternalism in political policymaking: The justification for no-vote stadium subsidies. Journal of Sport Management, 28(2), 162–175. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2012-0210

- King, N. (2012). Doing template analysis. In G. Symon & C. Cassell (Eds.), Qualitative organizational research: Core methods and current challenges (pp. 426–450). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Klepal, D., & Schrade, B. (2014, May 28). Cobb approves major stadium agreements: Supporters dominate, criticals shut out at meeting. Atlanta Journal-Constitution, A1.

- Leslie, K., & Tucker, T. (2013, November 27). Cobb oks Braves move. Atlanta Journal-Constitution, A1.

- Liberty Media Corporation. (2017). Annual report. Liberty Media Corporation.

- Lutz, M. (2016, July 31). Some question Boyce’s vision for Cobb County: Newly elected chair says he’s ready to set the tone of transparency. Atlanta Journal-Constitution, B1.

- Lutz, M., & Brasch, B. (2017, April 14). SunTrust Park Opening Day: Park pulls Cobb closer to Atlanta: Baseball stadium reflects change in suburb’s view of city. Atlanta Journal-Constitution, A1.

- Mason, D. S. (2016). Sport facilities, urban infrastructure, and quality of life: Rationalizing arena-anchored development in North American cities. Sport & Entertainment Review, 2(3), 63–69.

- Mason, D. S., Washington, M., & Buist, E. A. N. (2015). Signaling status through stadiums: The discourses of comparison within a hierarchy. Journal of Sport Management, 29(5), 539–554. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2014-0156

- Mondello, M. J., Schwester, R. W., & Humphreys, B. R. (2009). To build or not to build: Examining the public discourse regarding St. Petersburg’s stadium plan. International Journal of Sport Communication, 2(4), 432–450. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsc.2.4.432

- Monroe, D. (2012, August 1). Where it all went wrong. Atlanta Magazine.

- Niesse, M. (2015, February 22). New cities drive new rift in region: Incorporations divide area by class, race. Atlanta Journal-Constitution, A1.

- Pyun, H. (2019). Exploring causal relationship between Major League Baseball games and crime: A synthetic control analysis. Empirical Economics, 57(1), 365–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-018-1440-9

- Rosen, S. (2017, April 26). Atlanta’s controversial ‘cityhood’ movement. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2017/04/the-border-battles-of-atlanta/523884/

- Rosentraub, M. S. (2010). Major league winners: Using sports and cultural centers as tools for economic development. CRC Press.

- Rosentraub, M. S. (2014). Reversing urban decline: Why and how sports, entertainment, and culture turn cities into major league winners (2nd ed.). Taylor & Francis.

- Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Sant, S.-L., & Mason, D. S. (2019). Rhetorical legitimation strategies and sport and entertainment facilities in smaller Canadian cities. European Sport Management Quarterly, 19(2), 160–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2018.1499789

- Santo, C. (2005). The economic impact of sports stadiums: Recasting the analysis in context. Journal of Urban Affairs, 27(2), 177–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0735-2166.2005.00231.x

- Schneider, K. (2018, January 21). Welcome to the redeveloped neighborhood. New York Times, BU3.

- Smart Growth America. (2014). Measuring sprawl 2014. Smart Growth America.

- Soebbing, B. P., Mason, D. S., & Humphreys, B. R. (2016). Novelty effects and sports facilities in smaller cities: Evidence from Canadian hockey arenas. Urban Studies, 53(8), 1674–1690. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015576862

- Stokes, S. (2015, April 27). How Atlanta was kept out of Cobb County by a 10-foot-wide city. WABE. https://www.wabe.org/how-atlanta-was-kept-out-cobb-county-10-foot-wide-city/

- Suchma, P. C. (2005). From the best of times to the worst of times: Professional sport and urban decline in a tale of two Clevelands, 1945–1978 [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. The Ohio State University.

- Tierney, M. (2014, September 17). To mixed reaction, Braves begin work on stadium outside downtown. The New York Times, B14.

- Turner, R. S., & Rosentraub, M. S. (2002). Tourism, sports and the centrality of cities. Journal of Urban Affairs, 24(5), 487–492. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9906.00133

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Profile of general population and housing characteristics. 2010 Census of Population and Housing. https://factfinder.census.gov/

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2014). ACS demographic and housing estimates. 2010–2014 American Community Survey 5-year estimates. https://factfinder.census.gov/

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2017). ACS demographic and housing estimates. 2013–2017 American Community Survey 5-year estimates. https://factfinder.census.gov/

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2018). New Census Bureau population estimates show Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington has largest growth in the United States [Press release]. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2018/popest-metro-county.html

- Van Mead, N. (2018, October 25). A city cursed by sprawl: Can the BeltLine save Atlanta? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2018/oct/25/cursed-sprawl-can-beltline-save-atlanta

- Wickert, D., & Lutz, M. (2016, July 27). Challenger ousts Cobb chairman: Lee, who lured Braves to county, concedes defeat to retired colonel. Atlanta Journal-Constitution, A1.