Abstract

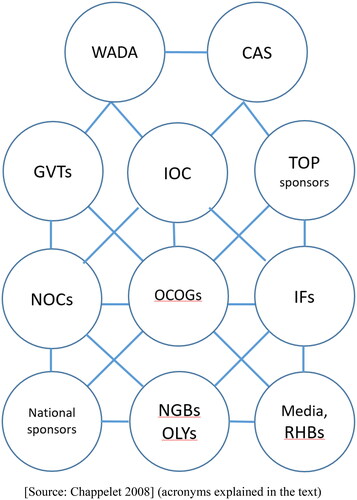

This paper describes how the number of stakeholders involved in staging the modern Olympic Games has grown and how this growth affects the resulting (Olympic) system’s governance. Relationships between stakeholders in the current Olympic system are now so varied and complex that purely hierarchical (led by the International Olympic Committee or by States) or market-based approaches to its governance are unsuitable. A possible alternative would be a collaborative form of governance that takes into account actors whose salience has increased greatly in recent years—elite athletes, civic groups, national courts of justice, as well as local, regional, and national governments.

1. Introduction

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) was created in 1894, following the Paris congress convened by Pierre de Coubertin to revive the Olympic Games. Since then, it has overseen the staging of the Olympic Games by a major city—at first in Europe or the United States, later throughout the world—every four years, except during times of global conflict (the 1916, 1940, and 1944 Olympics were cancelled because of World Wars I and II). The only peacetime exception to this rule occurred very recently, when the worldwide coronavirus pandemic resulted in the Citation2020 Tokyo Olympics being postponed until 2021 (while retaining the name Tokyo Citation2020). From its earliest days, the IOC has mounted the Summer Olympics, and subsequently the Winter (launched in 1924) and Youth (launched in 2010) Olympics, in conjunction with other bodies, all of which are stakeholders in a true multi-organizational social system that has become increasingly complex over the Olympiads.

This paper describes how the Olympic system has evolved from its relatively simple beginnings in 1894 into today’s much more complex system in which numerous stakeholders, some more important than others, contribute to executing one of the biggest projects undertaken in times of peace: putting on the modern Olympic Games. Understanding this evolution is essential for the current Olympic system’s governance, which can no longer be limited to its management by the IOC alone. The following conceptual analysis combines detailed knowledge of the Olympic system, acquired through many years’ observations of its day-to-day workings and its official documents, with the perspectives provided by stakeholder theory (e.g. Freeman et al., Citation2018) and the concept of collaborative governance (e.g. Shilbury et al., Citation2016). It suggests a way in which the current system’s governance could evolve in order to better integrate its most important stakeholders, whether they are nonprofit organizations, public bodies, private corporations or individuals. Major sources in the literature were Chappelet and Kübler-Mabbott (Citation2008), Parent (Citation2016) and Jedlicka (Citation2018).

Section 1 summarizes the events behind the birth of the Olympic system, starting with the creation of the IOC and the staging of the first modern Games in Athens in 1896. Section 2 describes the emergence of the classic Olympic system, consisting of the IOC and four new (at the time) stakeholders: Organizing Committees for the Olympic Games, National Olympic Committees, and National and International Sport Federations. Section 3 covers the period from the 1960s to the early 2010s, during which the classic Olympic system of stakeholders evolved into the regulated Olympic system. These changes began with increased interest in the Olympic Games from the media, governments, and sponsors, which enabled the Olympic system to become self-financing, and culminated with the addition of two new regulatory bodies—the Court of Arbitration for Sport and the World Anti-Doping Agency. Section 4 concludes this overview by describing how the growing importance of elite athletes, civic groups, and national courts of justice, three formerly minor stakeholders, has shaped the current governance of the Olympic system. Finally, Section 5 shows how identifying the current Olympic system’s main stakeholders can help determine an appropriate model for its governance in the future.

2. The IOC and the First Modern Olympics Stakeholders (1894–1900)

The French aristocrat Pierre de Coubertin is widely known as the founder of the modern Olympics, although he was not the first or only person to suggest ‘reviving’ the ancient Games. For example, Greece’s Evangelos Zappas had tried to resurrect the Olympics in the form of what became known as the ‘Zappas Olympics’, which were held in Athens in 1859, 1870, 1875, and 1888 (Weiler, Citation2004). Coubertin launched his project at a meeting in Paris in June 1894, to which he invited the era’s most important sport organizations from around the world. Ostensibly, they were there to discuss the issue of amateurism within the sports competitions that were beginning to be held, but Coubertin expanded the agenda at the last minute to include a motion on reviving the Olympic Games ‘on a basis conform with the conditions of modern life’ (Coubertin, Citation1892, p. 58). The delegates unanimously accepted Coubertin’s proposition and agreed to create the International Committee of the Olympic Games (renamed the IOC soon after) with Coubertin as its general secretary, an association of natural persons to award the Games to a city every four years. Although Coubertin wanted the first edition of the event to be held in 1900 in Paris, his hometown, where he felt he could control their organization, the delegates chose to inaugurate the modern Games in Athens in 1896.

Coubertin visited Athens in the autumn of 1894 to form a local organizing committee but came up against strong opposition from the Greek government, which was reluctant to invest the resources needed to stage a series of competitions in modern sports that were still little known in Greece. On the other hand, he received enthusiastic support from Danish born Greece’s king, who saw the event as a way of associating the monarchy with Ancient Greek traditions and thereby legitimizing his position. Greece’s crown prince agreed to head a local organizing committee, which, helped by a change of prime minister, staged the first Olympic Games of the modern era in April 1896. Centered round the ancient Panathinaikos Stadium, rebuilt for the occasion by a wealthy Greek benefactor, the event attracted athletes from 14 countries, who competed in nine sports. The first modern Olympics were a great success with the Greek public and monarchy, who wanted to see Athens host the Games every four years (Mandell, Citation1976).

Although Coubertin had been sidelined by the Greek organizers, the statutes adopted at the 1894 Paris congress ensured he took over the presidency of the IOC following the Athens Games. Because he was convinced that the revived Olympics would be a lasting success only if they were hosted by a different city in a different country every four years, Coubertin ignored Greece’s demands and the second edition of the Games was held in Paris, in 1900, as originally planned. He also believed that host cities should be chosen by the IOC, in other words by him, as the IOC at this time consisted of 15 of Coubertin’s acquaintances (only 7 of whom had attended the Games in Athens) who followed his proposals without demur. Nevertheless, in 1906 Greece staged ‘Intermediary Games’, celebrating the 10th anniversary of the modern Games, but this was the only time such an event was held. Thus, the IOC increasingly established itself as the permanent body responsible for selecting host cities, while entrusting the staging of the event to local organizers.

3. The Classic Olympic System Governance (1900–1960)

After the 1896 Games, Coubertin felt it would be easy to set up an organizing committee for the 1900 Paris Olympics. However, the first committee had to abandon the task in 1899 due to a lack of support within sporting circles. To Coubertin’s dismay, responsibility for staging the Games was given to a commission for ‘international competitions in physical fitness and sports’ and subsumed into the 1900 Paris Exposition. This gigantic World’s Fair was a great success, but it overshadowed the Olympic Games to such an extent that some participants did not realize they had taken part in the second Games of the modern era until long after the event (Mallon, Citation1998). Similarly, the IOC attributed the 1904 Olympics to Chicago only for the event to be moved to Saint-Louis (Missouri) and incorporated into the 1904 World’s Fair, held to celebrate the Louisiana Purchase. The local organizers persuaded US President Theodore Roosevelt to be the Games’ honorary president but pushed aside the IOC and went on to do a poor job of organizing the event, most of whose participants were Americans. Coubertin did not attend, preferring to hold that year’s meeting of the IOC in London.

The first Olympics to be organized by a proper Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games (OCOG), as such committees would later become known, was London 1908. Again, the Games took place at the same time as a major fair, in this case the 1908 Franco-British Exhibition celebrating the Entente Cordiale, but they were held on a completely separate site, centered round a large stadium with its own velodrome and swimming pool. Nevertheless, the 1908 Olympics were not free from controversy, due to a dispute between the Americans and the British over which rules should apply to the competitions (Coates, Citation2004).

One reason for such disagreements was the rarity of what we now call international sport federations (IFs). In fact, the only IFs to exist prior to the creation of the IOC were the Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique (FIG), founded in 1881, the Fédération Internationale des Sociétés d’Aviron (FISA, today World Rowing) and International Skating Union (ISU), both founded in 1892. These pioneers were followed by most other major sports during the early decades of the 20th century, which saw the founding of the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI, 1900), Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA, 1904), International Weightlifting Federation (IWF, 1905), International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF, 1908), Fédération Internationale de Natation Amateur (FINA, 1908), International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF, 1912, today World Athletics), etc.

Many of these IFs were created in conjunction with editions of the Olympic Games in order to define standard rules for their disciplines and thereby avoid the sort of controversies that marred London 1908. Their role in the Olympic Games is to ensure competitions are run according to international rules and to supply judges and referees in collaboration with the appropriate national federation or governing body (NGB). During their early days, IFs were run by volunteers and did not usually have paid staff. This was also the case for the IOC, which was run single-handedly by Coubertin. In 1921, the IOC invited the IFs to Lausanne for an Olympic Congress (the first to be held after World War I), so they could ‘finalize’ the rules applied at the Games. IFs, at the instigation of the UCI, used this gathering to create a ‘permanent bureau of international sport federations’ to defend their interests vis-à-vis the IOC. This bureau would not, however, survive World War II. It was replaced in 1967 by the GAISF (General Assembly of Internal Sport Federation) which was a powerful organization until the 1980s.

Like IFs, National Olympic Committees (NOCs) were also starting to emerge at the beginning of the 20th century. Coubertin quickly called upon every country to create an NOC to select and send a team to each edition of the Games. In fact, competitors at the first editions of the Olympics were simply athletes who were already in the host country (often because it was their home country) or students who were able to travel to the Games (e.g. the United States’ team for the first Olympic Games consisted of a few students from Princeton and Harvard; Mandell, Citation1976, p. 114). Although some NOCs claim to have existed since the IOC was created (United States, France, Greece, etc.), because representatives from these countries attended the 1894 Paris congress, the first true NOCs did not come into being until just before World War I (e.g. the Austrian Olympic Committee, founded in 1908, and the Swiss Olympic Committee, founded in 1912, following the Stockholm Olympics). Most of today’s NOCs were founded when their country gained independence following World War II.

NOCs are associations of their country’s national governing bodies (NGBs) for Olympic sports. Since the 1970s, many NOCs have become Olympic and Sport Confederations that include the NGBs for Olympic and non-Olympic sports. For example, in 1972, the French Olympic Committee merged with France’s National Sport Committee to form the French National Olympic and Sport Committee (CNOSF). Switzerland’s and Germany’s NOCs have done likewise (in 1997 and 2006, respectively). The main exception in Europe is the British Olympic Association which concentrates on sports featured in the Olympics. It is not the umbrella organization for the United Kingdom’s NGBs, as there often are separate governing bodies for each sport in each of the UK’s constituent nations (England, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland).

NGBs are national umbrella organizations for clubs within a given sport. Their role with respect to the Olympic Games is to supply their NOC with athletes in their sport, who could participate in the Olympics if they achieve a minimum qualifying standard set by the IF (which usually organizes qualifying competitions, especially for team sports). Because countries may enter only three (and sometimes fewer) athletes in each event, if more than three athletes achieve the qualifying standard set by the IF, the NGB may organize selection trials. Conversely, if a country does not have any athletes who meet the qualifying standard in any of the athletics or swimming disciplines, the NOC may still enter a man and a woman in each of these sports in order to make participation in the Games more universal. NOCs generally accept their NGBs’ recommendations for which athletes to send to the Games. NGBs were created throughout the 20th century, as sports grew in popularity at different times in different countries. For athletes in a given sport to be able to compete in the Olympics and world championships, their NGB must be a member of its country’s NOC and of the IF for their sport.

A minimum of five NGBs (including three of Olympic sports) are needed to form an NOC. In Citation2020, the IOC recognized 206 NOCs. (NOCs are not members of the IOC as many believe.) Most NOCs represent ‘an independent State recognized by the international community’ (Rule 30 of the Olympic Charter). However, past moves by the IOC to maximize the number of NOCs means that the list of recognized NOCs also includes some non-independent territories (e.g. Hong Kong, Guam, British Virgin Islands). Today, an NOC of a country or territory that is not a member of the United Nations has little chance of obtaining IOC recognition. Kosovo, which gained IOC recognition in 2014, is a notable exception to this rule. A few NOCs (e.g. Gibraltar, Faroe Islands, Catalonia) are not recognized by the IOC, even though some IFs recognize these territories’ NGBs. Nevertheless, IFs have begun restricting membership to countries recognized by the ‘international community’, which will automatically limit the potential number of new NOCs.

Furthermore, the IOC does not recognize all IFs and for the IFs it does recognize it differentiates between those for sports on the Olympic program (33 for Tokyo Citation2020, 7 for PyeongChang 2018) and those for sports that are not on the Olympic program (around 40, e.g. bowling, cricket, orienteering). All IFs can be accepted as members by the Global Association of International Sport Federations (GAISF), a distant successor to the ‘permanent bureau of international sport federations’ set up in 1921 and the former GAISF set up in 1967 (see above). For an IF, being granted GAISF membership is today considered recognition of the discipline as a distinct sport.

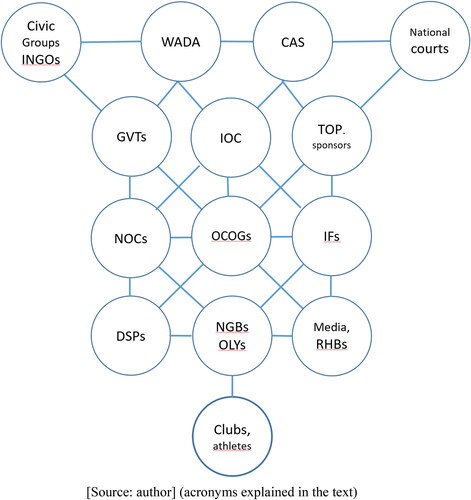

Thus, four key, or primary (Freeman et al., Citation2018, p. 17), Olympic stakeholders emerged during the first half of the 20th century, in chronological order: OCOGs, IFs, NOCs, and NGBs. Together with the IOC, created in 1894, these stakeholders form the classic Olympic system, shown in by five circles, like the five interlocking rings of Coubertin’s Olympic logo, but arranged differently. The lines between stakeholders show the above-described ties of recognition and cooperation for staging the Olympic Games. The link between the IOC and the OCOGs is contractual (via the so-callled ‘host city contrat’). The governance of this system is mostly hierarchical (by the IOC which is the oldest actor, and the self-proclaimed ‘leader of the Olympic Movement’ according to the Olympic charter, the set of rules that govern the IOC and the Olympics) although the IFs disputed this dominance through GAISF until de 1980s.

Figure 1. The classic Olympic system.

Source: Chappelet (Citation1991, p. 67) (acronyms explained in the text).

4. The Regulated Olympic System Governance (1960–2010)

After World War II, the classic Olympic system strengthened its ranks and the Olympic Games took on greater importance with each Olympiad and therefore began attracting the interest of four new types of stakeholder: in chronological order: 1) the media, 2) national and regional governments, 3) domestic sponsors, and 4) international sponsors. These stakeholders would soon enable the entire system to become self-financing.

The media had taken an interest in the modern Games from their inception, providing coverage according to the techniques of the time. Thus, early editions of the Olympics were reported in newspapers and magazines, occasionally with photographs (as of 1896). Indeed, in an early example of commercialization, the OCOG for Stockholm 1912 sold the right to print ‘official’ photographs of the Games as postcards. However, there are almost no moving pictures of the Games from before World War I, even though cinema was invented a year before the 1896 Athens Olympics. Substantial radio coverage of the Olympics began at Paris 1924, with local television trials following 12 years later, at Berlin 1936, and after World War II, at London 1948. The practice of selling television rights for the Olympic Games was begun by the OCOG for Rome 1960, which sold the rights to the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), for networks in western Europe (via the Eurovision live broadcast system), and to Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), for the United States. CBS was not yet able to show the event live, as film taken in Rome had to be flown to New York before being broadcast across the United States. This changed just four years later, at Tokyo 1964, which saw the first live satellite broadcasts. Coverage of the Olympics has continued to incorporate advances in broadcasting technology (video recorders, color, high definition, cloud, etc.) ever since.

Selling the ‘television rights’ to Rome 1960 earned the OCOG US$1.2 million, a small percentage of which it gave to the IOC. In contrast, the IOC sold the television rights for Tokyo Citation2020 for more than US$3.1 billion, a large proportion of which it redistributed to the OCOG, NOCs, and IFs involved. Today, television rights are bundled with internet broadcasting rights and account for approximately three-quarters of the IOC’s revenue (more than US$4.5 billion every four years). Rule 48.1 of the Olympic Charter requires the IOC to take all necessary steps in order to ensure the widest possible audience in the world for the Olympic Games. This is ensured by requesting Right Holding Broadcasters (RHBs) in their contracts with the IOC to provide 200 hours of free-to-air coverage of the Olympic Games on non-subscription channels in their territory, in order to ensure maximum exposure for the Games. On the other hand, the print media and photographers are accredited but do not pay rights. The IOC also gives accreditation to broadcasters other than RHBs, but these broadcasters cannot show moving pictures of the Olympics and are limited in how they can report the Olympics as news (IOC Citation2017 ; IOC Citation2019b).

National governments did not initially show much interest in the Olympic system and, for their first four decades, the Olympics remained an essentially private affair, organized by an OCOG for elite athletes from around the world. Coubertin and OCOGs always took care to invite heads of state to Olympic ceremonies and local authorities were necessarily involved in staging the event, but input from national or regional governments (GVTs) was limited. This began to change in 1936, when the Nazi regime turned the Berlin Olympics into a showcase for the ‘new Germany’. All subsequent OCOGs were largely subsidized by their national government, which saw hosting the Games as a way of marking their country’s presence on the world stage (nation branding) and/or highlighting its (re)acceptance into the ‘concert of nations’. This was the case for countries such as Italy (Rome 1960), Japan (Tokyo 1964), Mexico (Mexico City 1968), Germany (Munich 1972), South Korea (Seoul 1988), and China (Beijing 2008). As a result, by the 1970s national and regional, as well as local, governments had become crucial, primary stakeholders in the Olympic system.

The 1970s also saw a huge increase in sport’s political importance, both internationally, due to the Cold War (the Soviet Bloc used the Games to demonstrate the superiority of the communist system), and nationally, due to the massive growth in grassroots sport, especially among women. Many governments responded to this growing importance by subsidizing their NGBs and NOC. In addition, many countries, including Switzerland (1972), France (1975), and the United States (1978), introduced legislation to structure non-professional sport, and UNESCO adopted an International Charter for Physical Education and Sport (in 1978). These normative documents have been regularly updated and now cover grassroots sport and physical activity, as well as elite sport and physical education.

Corporate support for local and national sports activities is at least as old as government subsidies and programs (e.g. Kodak advertised in the 1896 Olympics brochures), but it started expanding rapidly in the 1980s, at first nationally and then internationally, notably during the Olympic Games. Munich 1972 and Montreal 1976 presaged this growth, as they both drew up sophisticated domestic sponsorship programs with companies (called domestic sponsors) that were prepared to contribute to the OCOG, in cash and in kind, in exchange for the right to associate their brands with the OCOG’s emblem (with the Olympic rings) in the host country’s territory (only). In 1985, the IOC launched its own program—now entitled The Olympic Partners (TOP)—which enables TOP multinationals to associate themselves with consecutive Winter and Summer Olympics throughout the world, and with all the NOCs and their Olympic teams (Wenn & Barney Citation2020, chapter 6). Today, domestic sponsors are the largest source of revenue for OCOGs (more than US$3 billion for Tokyo) and TOP sponsors provide about a quarter of the IOC’s income (approximately US$2 billion during the current quadrennium 2017-Citation2020/1).

Between the 1960s and 1980s, the media, national and regional governments, domestic sponsors, and international (TOP) sponsors gradually became indispensable Olympic stakeholders and integral parts of the Olympic system. They became primary stakeholders, directly involved in value creation for the Olympic system (economic stake). During the 1990s they were joined by two very different stakeholders—the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) and the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA).

Although the CAS was created by the IOC in 1984, it did not come into its own, and gain a large degree of independence, until the 1990s (McLaren, Citation2010). It is now recognized by every Olympic IF (and the IOC) as the competent authority for arbitrating regulatory or financial disputes between Olympic parties, notably athletes and IFs (Chappelet, Citation2021). Since Atlanta 1996, the CAS has operated an ad hoc arbitral tribunal at each edition of the Games in order to rapidly settle disputes that could affect subsequent stages of a competition.

WADA was set up in 1999 as a foundation funded equally by the Olympic movement (IOC, IFs, and NOCs) and State-parties to the 2005 UNESCO International Convention against Doping in Sport. WADA publishes a regularly updated World Anti-Doping Code that ‘harmonizes anti-doping policies, rules and regulations within sport organizations and among public authorities around the world’ (WADA, Citation2020). The code designates the CAS as the appellate body for decisions taken under the code (Chappelet & Van Luijk, Citation2018).

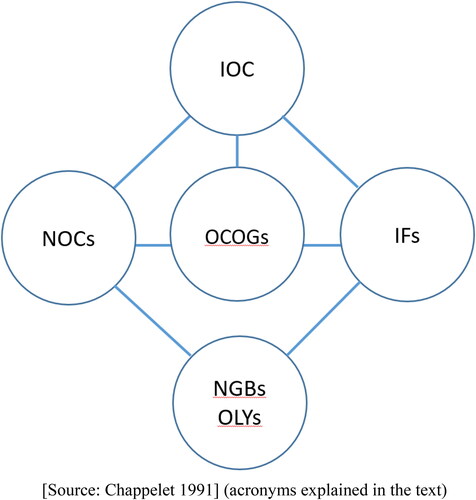

These two bodies, together with those described in the previous section, form what Chappelet and Kübler-Mabbott (2008) call the ‘regulated Olympic system’ (). Connecting lines show the above-described ties between these stakeholders, all of which contribute to staging the Games.

Figure 2. The regulated Olympic system.

Source: slightly adapted from Chappelet and Kübler Mabbott (Citation2008, p. 18) (acronyms explained in the text).

5. The Current Olympic System Governance (2010–Today)

The growth of the Olympic Games and the (regulated) Olympic system triggered the creation of many other types of Olympic secondary stakeholder at the end of the 20th century. These organizations include the Association of National Olympic Committees (ANOC), founded in 1979; the Global Association of International Sport Federations (GAISF, originally founded in 1967 as the General Assembly of the International Sport Federations and since relaunched several times); the Association of Summer Olympic International Federations (ASOIF) and its winter equivalent, the AIOWF, both founded in 1983; and the World Federation of the Sporting Goods Industry (WFSGI), founded in 1978. In addition, professional leagues of athletes and teams began working with the Olympic system so professional athletes in sports such as tennis, basketball, ice hockey, and golf would be allowed to take part in the Games. Then, at the beginning of the 21st century, three long-standing stakeholders that had previously had little impact on the Olympic system—elite athletes, civic groups, and national courts of justice—began making their voices heard. Incorporating these new stakeholders into the regulated Olympic system created the current Olympic system ().

Until recently, potential Olympic athletes and clubs had little influence over the Olympic system, as they had no direct representation and could eventually express themselves only via their IF, NGB or NOC. This began to change in the 2010s, especially for Olympic athletes (known as Olympians - OLYs), thanks to the athlete commissions set up by bodies within the classic Olympic system and to several ad hoc associations that were created to give them a voice. These bodies include the World Olympians Association, created in 1995 by the IOC and relaunched in the 2010s; the World Players Association, founded in 2017; Global Athlete, founded in 2018; and the Athletics Association (Chappelet, Citation2020). Athletes are now much more willing to speak out, as they demonstrated during the Russian doping crisis (2016–Citation2020), when several athletes openly criticized decisions taken by WADA, and the IOC. More recently, they complained about the time taken to postpone the Tokyo Citation2020 Olympics (Reuters, Citation2020).

Civic Groups (pro and most often against the Olympics) and public opinion also became more important for the Olympic system in the early 21st century. Although it is difficult to talk about a worldwide public opinion, as public opinions can differ greatly both locally and globally, the Olympic Games are facing increasingly vocal criticism from sections of the public (sometime organized as civic groups) in many countries and communities, and this criticism is having a major impact on bids to host the Games. For example, numerous cities interested in hosting the 2022 and 2026 Winter Olympics or 2024 Summer Olympics withdrew their candidacies following negative referendums (or threats of referendums). One of these cities was Boston, which withdrew its bid for the 2024 Games in the face of strong local, organized opposition, despite being the US Olympic Committee’s official candidate (Dempsey & Zimbalist, Citation2017). These local public opinions, supported by ad hoc activist, civic groups, are gradually coalescing into a sort of international anti-Olympic movement that regularly makes itself heard in both designated Olympic cities and potential candidate cities (Boykoff, Citation2014; Ganseforth, Citation2020; Lenskyj, Citation2008). Global public opinion and some international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) are largely supportive of this informal movement, as problems at recent editions of the Games, such as respect for human rights, the lack of legacies and huge costs of Sochi 2014 and Rio 2016, continue to tarnish the Olympics’ formerly (overly) idyllic image.

Before the turn of the 21st century, sports organizations within the classic Olympic system had almost never had to account for their actions before national courts of justice, whether in the countries in which they are based (most notably Switzerland) or hold their events (e.g. Brazil), or sometimes in relation to international law arising from treaties between States (e.g. European law). The creation of the CAS, under Swiss law (with appeals possible to Switzerland’s highest court, the Tribunal Fédéral), in 1984 had helped sports organizations largely avoid such legal scrutiny, as it acted as a sort of private legal system for sport. This began to change in the 2000s when numerous criminal accusations of corruption against high-profile members of organizations such as FIFA, the IAAF, the IOC, and the International Biathlon Union led several national justice systems (USA, France, Switzerland, Brazil, Norway, Austria, etc.) to take an interest in the operations of the classic Olympic system. In addition, elite athletes (Bosman, Meca-Medina, Cañas, Mutu, Pechstein, Semenya, etc.) have become more willing to take their cases to the European Court of Justice or to the European Court of Human Rights (of the Council of Europe) and not only to the CAS. Indeed, the CAS is only an arbitration tribunal, not a court of law, and it does not examine criminal cases (such as sport corruption).

In concert with the growing importance of civic groups, regional and national governments (GVTs) have been much more inclined to intervene in the Olympic system since the turn of the century than they were during the period of the regulated Olympic system (1960–2010). In fact, the Olympic Games have outgrown the organizational capacities of local governments (municipalities) and every host country since the Sydney 2000 Olympics has passed special legislation—known as Olympic laws—to cover the staging of the Games within their territory. This legislation generally includes exemptions to standard rules, most notably with respect to taxation and urban planning, and allows for the creation of ad hoc public agencies to build infrastructure, organize transportation, and provide security, etc. Olympic hosts must also create coordination mechanisms between the different local, regional, and national stakeholders, and the regional or national government will often appoint an Olympic minister (e.g. Sydney 2000, Turin 2006, London 2012, Tokyo Citation2020).

For example, the British government created an ‘Olympic Board’ to coordinate the actions of the various local stakeholders involved in the London 2012 Olympics (Theodoraki, Citation2007, p. 152). This board comprised senior members of the London Organising Committee for the Olympic Games (LOCOG), the Olympic Delivery Authority (a public agency responsible for building Games infrastructure), the British Olympic Association (Britain’s NOC), and the Greater London Authority (regional government). It was chaired jointly by the Mayor of London (municipal and regional governments) and the Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport (Olympic minister in the national government). The postponement of the Tokyo Citation2020 Olympics further highlighted the growing importance of national governments, as this unprecedented decision was finalized during a telephone conversation between Japan’s prime minister and the president of the IOC, who announced the decision jointly (Meinhardt, Citation2020). A ‘Joint Steering Committee’, comprising two executives from the OCOG and two from the IOC, was set up to manage the postponement and to resolve the issues, especially financial, it raised (IOC, Citation2020b).

The IOC’s strategic roadmap, Olympic Agenda Citation2020, adopted in 2014, recognizes the need to work with governments in order to protect the independence of sports organizations: recommendation 28 (IOC, Citation2014) reads: ‘The IOC to create a template to facilitate cooperation between national authorities and sports organizations in a country’. In fact, Agenda Citation2020s repeated references to cooperation and collaboration with other stakeholders in the Olympic movement shows that the IOC might be considering to orient the current Olympic system towards the type of collaborative governance proposed by Ansell and Gash (Citation2007) and Bryson et al. (Citation2015) in the fields of policy and public administration (because the Games are more and more a public affair), and developed by Shilbury et al. (Citation2016) for the field of sport.

6. Collaborative Governance of the Olympic System in the 21st Century

The previous sections describe how the Olympic system has expanded by gradually attracting new primary stakeholders (). This expansion has made the governance of the Olympic system much more complex, as staging the Olympic Games now requires close collaboration between numerous primary (and secondary) stakeholders, each of which plays a specific and crucial role. In addition, each stakeholder possesses, to varying degrees, all three attributes—power, legitimacy, and, as the Games approach, urgency—defined by Mitchell et al. (Citation1997) to characterize a focal organization’s (here the IOC) most salient stakeholders.

Table 1. Increase in the Olympic system’s main stakeholders over successive Olympiads.

The IOC has a lot of power because it decides which cities will host the Games and because it largely finances the classic Olympic system (as well as CAS and WADA) from the huge sums it earns by selling Olympic broadcasting and commercial rights to RHBs and TOP sponsors. Although the IOC considers the Olympic Games to be its ‘exclusive property’ (Rule 7.2 of the Olympic Charter, IOC, Citation2019a), the Olympics cannot take place without the NOCs (which send teams), IFs (which sanction the competitions), and OCOGs (which stage the Games), all of which have strong legitimacy. For example, some NOCs have boycotted previous editions of the Games (mostly in the 1970s–1980s, often following pressure from their government). Individual IFs are less likely to boycott the Olympics because they all want to take part in the Games in order to promote their sport and to receive a share of the resulting cash revenues. With a few exceptions (such as FIFA), they are financially dependent on the IOC. NOCs are also dependent on cash and value in kind (functioning grants, athletes’ and coaches’ scholarships, various courses, advisory, etc.) they receive from their continental associations and from Olympic Solidarity, the IOC department responsible for distributing the share of IOC broadcasting and marketing revenues to the NOCs. Many NOCs also depend on subsidies from their government and collaborations with public authorities (Meier & Garcia, Citation2019). One in seven are politically linked to governments according to a recent survey by Play the Game (Citation2017).

The classic Olympic system, comprising the IOC, OCOGs, IFs, NOCs, and NGBs with OLYs, expanded greatly in the 1960s, largely due to the growing importance of several new stakeholders. The media and sponsors quickly became essential to the IOC’s business model, while national and regional governments were increasingly being called upon to provide the extensive infrastructure, security, diplomatic, health, and other services required by the Olympics but which the OCOG and local government could not supply alone. They were subsequently joined by two regulatory bodies that have been indispensable stakeholders since the 1990s: the CAS, which has operated an ad hoc chamber in the Olympic city since 1996 (see above), and WADA, founded in 1999, whose World Anti-Doping Code is a central element in the fight against doping in all sports and all countries.

Today, three additional stakeholders—elite athletes, civic groups, and national courts—are becoming more powerful. Elite athletes, especially potential Olympians, have realized they are indispensable to the Games and are demanding a greater say in how they are run (Chappelet, Citation2020). It has also become clear that the Olympic system cannot afford to ignore public opinion, both local and global, expressed through civic groups, the international media and some INGOs. Finally, national, and sometime European, courts of justice, including those outside Olympic host countries (e.g. Switzerland, cf. Baddeley, Citation2019, and the United States, cf. Henning, Citation2016) have begun taking an interest in the classic Olympic system, especially with respect to possible criminal acts committed by individuals within it. These three external, secondary (not directly creating value) but legitimate stakeholders now have considerable influence over the Olympic system, which has had to show it is governed ‘responsibly’ in order to maintain its autonomy (Chappelet, Citation2015).

The 14 most important stakeholders in the current Olympic system, listed in , are a mixture of non-profit organizations (IOC, OCOGs, NOCs, IFs, NGBs, WADA, CAS), public bodies (GVTs, Courts), private companies (media, domestic and TOP sponsors), and more-or-less structured groups of individuals (OLYs, athletes, clubs, civic groups). These stakeholders are independent from each other but collaborate closely within an ‘inter-organizational sport network’ (Wäsche et al., Citation2017), a form of coordination that is intermediate between state and market (Powell, Citation1990). The ‘lead or focal organizations’ in this network are no longer the OCOGs, as was the case when they alone negotiated television rights (from Rome 1960 to Los Angeles 1984). Today, this position is held by the IOC, the self-proclaimed ‘leader’ of the Olympic Movement (Olympic Charter, Rule 7.1). In fact, the OCOGs, and the IOC’s other non-profit stakeholders (IFs, NOCs, CAS, WADA, etc.), have been dependent on the IOC since the 1988 Winter (Calgary) and Summer (Seoul) Olympics, when the IOC took over global negotiations for Olympic broadcasting and marketing rights (Preuss et al., Citation2020), and began redistributing these revenues to its stakeholders forming the classic Olympic system.

Nevertheless, the IOC should not consider itself omnipotent within the system because the Games (which are its main product and almost its only source of revenue) cannot be staged without numerous stakeholders that are not directly dependent on the IOC but are directly involved in Olympic value creation, either through IOC recognition which grants them key responsibilities (e.g. NOCs, IFs) or through contracts (e.g. OCOGs, RHBs, domestic and TOP sponsors). The postponing of the Tokyo Citation2020 Olympics to the summer of 2021, in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, exemplifies this, as the IOC could not make this decision alone (IOC, Citation2020a). Pressure to postpone the event came from many potential Olympians and certain well-established NOCs (Canada, Australia, Brazil, etc.) (Reuters Citation2020). However, the final decision had to be made by the IOC in conjunction with the Japanese authorities (national government and Tokyo Metropolitan Government), because a unilateral decision by the IOC would have broken innumerable contracts, notably the host city contract (‘mother of all contracts’) that Tokyo and the Japanese NOC had signed with the IOC in 2013, and would have had incalculable legal consequences. Public opinion as well as civic groups, in Japan and around the world, were also a major factor in the postponement decision, as the IOC is aware of the growing impact of these new stakeholders on the success of the Games and cities’ desire to host future editions.

Hence, the current and future governance of the Olympic system must be increasingly collaborative in order to ensure the IOC satisfies the expectations of all its main stakeholders. This is particularly important, because failing to collaborate would risk losing the support of two essential stakeholders in ensuring the Games are a success: the public opinion (through civic groups and INGOs) and, consequently, local, regional and national host governments. Collaboration should not be only between the IOC (representing IFs and NOCs) and the OCOG, but should include national, regional and local governments as well as other Olympic stakeholders such as athletes, civic groups, sponsors and media. Such a wider collaboration will entice better public opinion support. For instance, the regular so-called ‘coordination commissions’ organised between the IOC and the OCOG should include other stakeholders.

7. Conclusion

This paper describes the evolution of the governance of the Olympic system, which can be divided into four phases: foundation (1894–1900), classic system (1900–1960), regulated system (1960–2010), and current system (2010-present) (). Each phase saw the addition of further stakeholders, beginning with the IOC, the founding and sole member of the initial Olympic system, and culminating with the incorporation of elite athletes, civic groups and national courts of justice, all of which started playing larger roles in the governance of the Olympic system at the beginning of the 21st century.

Although all the stakeholders in the classic Olympic system (OCOGs, NOCs, IFs, and NGBs) depend on the IOC, subsequent iterations of the system have included ever more stakeholders that are largely independent of the IOC despite creating essential economic value. Hence, the governance of the current Olympic system cannot be hierarchical, whether led by states or by Olympic bodies, or be left to market forces (represented by the Olympic media and sponsors); it must bring together all 14 primary stakeholders and be hybrid in order to protect the Games’ festive atmosphere, in accordance with the Roman notion of ‘res communis’ or common thing. As such, the Games must remain free and accessible to residents and visitors, for example, through the urban parks, live sites, and fan zones that have become a feature of recent Olympic editions. Indeed, the Olympic Games in the early 21st century are much more than a sports event; they have come to resemble what they were at their apogee in Ancient Greece: a meeting place for the known world. Consequently, they are closer to being a ‘commons’ (that generate a ‘bundle of rights’) than only a private property and must therefore adopt the very specific form of governance such entities need, as outlined by Elinor Ostrom (Citation1990) in her seminal book on the issu. This perspective requires further research. Most importantly, such governance must involve many stakeholder, including all levels of government within the host country, civic groups, and athletes or potential Olympians, as well as the classic Olympic movement organizations (IOC, OCOG, NOCs, IFs, NGBs).

The stakeholder perspective adopted in this paper provides a better understanding of why, after operating for more than a century, the Olympic system must now be governed as a collaborative network. Responsibility for implementing the necessary changes falls to the system’s self-proclaimed leader, the IOC. Despite the urgency, it remains to be seen how quickly these changes can be implemented.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jean-Loup Chappelet

Jean-Loup Chappelet (Ph.D., University of Montpellier, France) is an emeritus professor of public management at the Swiss Graduate School of Public Administration (IDHEAP) of the University of Lausanne, Switzerland since 2018. He was the Dean of this school for ten years. His reseearch interests are in the governance of sports organisations in particular the IOC (International Olympic Committee) and the delivery and legacy of major sports events, including the Summer and Winter Olympic Games which I have attended in various capacities since respectively 1972 and 1980.

References

- Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2007). Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(4), 543–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum032

- Baddeley, M. (2019). The extraordinary autonomy of sports bodies under Swiss law: Lessons to be drawn. The International Sports Law Journal. 20, 3–17. https:// https://doi.org/10.1007/s40318-019-00163-6

- Boykoff, J. (2014). Activism and the Olympics: Dissent at the games in Vancouver and London. Rutgers University Press.

- Bryson, J. M., Crosby, B. C., & Stone, M. M. (2015). Designing and implementing cross‐sector collaborations: Needed and challenging. Public Administration Review, 75(5), 647–663. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12432

- Chappelet, J.-L. (1991). Le système olympique. Presses universitaires de Grenoble.

- Chappelet, J.-L. & Kübler-Mabbott, B. (2008). The IOC and the Olympic system, the governance of world sport. London: Routledge.

- Chappelet, J.-L. (2015). Autonomy and governance: Necessary bedfellows in the fight against corruption in sport. In Transparency International Global Corruption Report 2015: Sport (pp.16–28). London: Routledge.

- Chappelet, J.-L. (2020). The unstoppable rise of athlete power in the Olympic system. Sport in Society, 23(5), 795–809. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2020.1748817

- Chappelet, J.-L. (2021). The governance of the Court of Arbitration for Sport. In D. Chatziefstathiou, B. García, & B. Seguin (Eds.), The handbook of Olympic and Paralympic studies (pp. 309–320). Routledge.

- Chappelet, J.-L., & Van Luijk, N. (2018). The institutional governance of global hybrid bodies: The case of the World-Anti Doping Agency. In A. Bonomi Savignon, L. Gnan, A. Hinna, & F. Monteduro (Eds.), Hybridity in the governance and delivery of public services (pp. 167–191). Emerald Publishing.

- Coubertin, P. D. (1892). Conférence faite à la Sorbonne, 25 novembre 1892. In François d'Amat (ed.) Le Manifeste olympique. Lausanne: Editions du Grand-Pont.

- Coates, J. (2004). London 1908. In J. E. Findling & K. D. Pelle (Eds.), Encyclopedia of the modern Olympic movement (pp. 51–56). Greenwood Press.

- Dempsey, C., & Zimbalist, A. (2017). No Boston Olympics: How and why smart cities are passing on the torch. University Press of New England.

- Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., & Zyglidopoulos, S. (2018). Stakeholder theory. Cambridge University Press.

- Ganseforth, S. (2020). Anti-Olympic rallying points, public alienation, and transnational alliances. The Asia-Pacific Journal, 18(5), 1.

- Henning, P. J. (2016). Road map for pursuit of soccer charges. The International New York Times, June 29.

- IOC. (2014). Olympic Agenda 2020, 20 + 20 recommendations. International Olympic Committee.

- IOC. (2017). Guidelines for editorial use of the Olympic properties for media organisation, Lausanne, International Olympic Committee. . Retrieved April 25, 2020, from https://library.olympic.org/Default/doc/SYRACUSE/170781/guidelines-for-editorial-use-of-the-olympic-properties-by-media-organisations-international-olympic-?_lg=fr-FR

- IOC. (2019a). Olympic charter in force as from June 26, 2019. International Olympic Committee.

- IOC. (2019b). News access rules applicable to the Games of the XXXII Olympiad Tokyo 2020. International Olympic Committee.

- IOC. (2020a). IOC and Tokyo 2020 Joint Statement. IOC Press Release, April 16. . Retrieved October 3, 2020, from https://www.olympic.org/news/ioc-and-tokyo-2020-joint-statement-framework-for-preparation-of-the-olympic-and-paralympic-games-tokyo-2020-following-their-postponement-to-2021

- IOC. (2020b). IOC and Tokyo 2020 Joint Statement. IOC Press Release, April 16. . Retrieved April 25, 2020, from https://www.olympic.org/news/ioc-and-tokyo-2020-joint-statement-framework-for-preparation-of-the-olympic-and-paralympic-games-tokyo-2020-following-their-postponement-to-2021

- Jedlicka, S. R. (2018). Sport governance as global governance: Theoretical perspectives on sport in the international system. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 10(2), 287–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2017.1406974

- Lenskyj, H. (2008). Olympic industry resistance: Challenging Olympic power and propaganda. State University of New York Press.

- LOCOG. (2013). London 2012 Olympic Games: The official report, Vol. 3: Summary of Olympic Games preparations. The London Organising Committee for the Olympic Games and Paralympic Games.

- Madison, M. J., Frischmann, B. M., & Standburg, K. J. (2008). Constructing commons in the cultural environment (Legal Studies Research Series, WP 2008-6, PITT-LAW). University of Pittsburg.

- Mallon, B. (1998). The 1900 Olympic Games: Results for all competitors in all events, with commentary. McFarland & Company.

- Mandell, R. (1976). The first modern Olympics. University of California Press.

- McLaren, R. H. (2010). Twenty-five years of the court of arbitration for sport: A look in the rear-view mirror. Marquette Sports Law Review, 20(2), 305–333.

- Meier, H. E., & Garcia, B. G. (2019). Collaborations between National Olympic Committees and public authorities. Final report for the IOC Olympic Studies Centre Advance Olympic Research Grant Programme 2019/2020 Award. WWU Münster Loughborough University.

- Meinhardt, G. (2020). How does it feel to be a bogeyman, Herr Bach? Die Welt, April 12. www.welt.de/sport/article207203027/IOC-President-How-does-it-feel-to-be-a-bogeyman-Herr-Bach.html

- Mitchell, R. K., Agle, B. R., & Wood, D. J. (1997). Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of Management Review, 22(4), 853–886. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1997.9711022105

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons, the evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press.

- Parent, M. M. (2016). The governance of the Olympic Games in Canada. Sport in Society, 19(6), 796–816. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2015.1108652

- Play the Game. (2017, June 8). One in seven Olympic Committees are directly linked to governments. Retrieved October 3, 2020, from https://www.playthegame.org/news/news-articles/2017/0311_one-in-seven-olympic-committees-are-directly-linked-to-governments

- Powell, W. W. (1990). Neither market nor hierarchy: Network forms of organization. Research in Organizational Behaviour, 12, 295–336.

- Prell, C. (2012). Social network analysis: History, theory and methodology. Sage.

- Preuss, H., Koenigstorfer, J., & Dannewald, T. (2020). Contingent valuation measurement for staging the Olympic Games: The failed bid to host the 2018 Winter Games in Munich. In S. Roth, C. Horbel, & B. Popp (Eds.), Perspektiven des Dienstleistungs managements aus Sicht von Forschung und Praxis (pp. 461–478). Springer Verlag.

- Reuters. (2020, March 23). Canada, Australia pull out of Olympics as pressure mounts on Tokyo to postpone 2020 Games. . Retrieved October 3, 2020, from https://www.france24.com/en/20200323-canada-pulls-out-of-olympics-as-pressure-mounts-on-tokyo-to-postpone-2020-games (Last consulted 03.10.20).

- Shilbury, D., O’Boyle, I., & Ferkins, L. (2016). Towards a research agenda in collaborative sport governance. Sport Management Review, 19(5), 479–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2016.04.004

- Theodoraki, E. (2007). Olympic event organization. Elsevier.

- Wäsche, H., Dickson, G., Woll, A., & Brandes, U. (2017). Social network analysis in sport research: An emerging paradigm. European Journal for Sport and Society, 14(2), 138–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2017.1318198

- Weiler, I. (2004). The predecessors of the Olympic Movement, and Pierre de Coubertin. European Review, 12(3), 427–433. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1062798704000365

- Wenn, S. R., & Barney, R. K. (2020). The gold in the rings. Chicago University Press.