Abstract

This paper investigates the influences of change recipients’ supportive behaviors toward the national reform in the Chinese football sector. Qualitative data were collected through semi-structured interviews (n = 29), which were conducted with change recipients from national and local football associations and commercial football clubs. Drawing on an integrated conceptual framework, the findings suggest that the change-supportive behaviors demonstrated by the change recipients were influenced and incentivised by managerial factors (i.e., management competency, communication channels, participation in decision-making, leaders’ commitment to change, and principal support); and contextual factors (i.e., an amenable football environment and the perceived political pressure to change). Three manifestations of change-supportive behaviors were identified: a) showing understanding of the change but pessimistic about the outcome; b) supporting the change and being willing to take risks; and c) supporting the change and actively seeking alternative solutions.

1. Introduction

Sport organizations exist in fluid environments with constant change pressure because of the intensively competitive global market, rapid technological innovation, and pressure for return on capital investment (Amis et al., Citation2002; Cunningham, Citation2006a, Citation2009; Fahlén & Stenling, Citation2019). The change management process has posed challenges for sport managers because the majority of change initiatives fail (Cunningham, Citation2006b). Amongst the various reasons that have been identified to explain the failure, or unintended consequences of organizational change are the timing of change (Saxton, Citation1995), institutional resistance (Kikulis, Citation2000; Kikulis et al., Citation1992), organizational conflict (Zheng et al., Citation2019), mistrust or distrust in the organizational setting (O’Boyle & Shilbury, 2016) and the cost of change (Kihl et al., Citation2010). However, the lack of consideration given to human experience (e.g., change recipients’ readiness for change) in the change process is considered to be the primary reason for the failure of many organizational change initiatives (Fahlén & Stenling, Citation2019). Kim et al. (Citation2011) argued that change-supportive behaviour (CSB), or employees’ behaviors to support change, despite its importance in an organizational change process, has received little attention in organization studies. Factors that lead to various supportive behavioural reactions as well as the demonstrations of CSB in a non-western sport context, in particular, remain unclear.

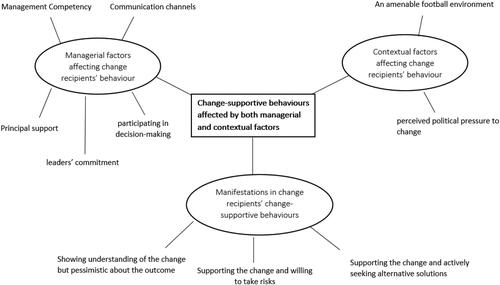

Against this backdrop, this paper aims to address the paucity of research on change-supportive behaviour in a non-western sport context. The aim is realised by examining both managerial and contextual factors as well as the manifestations of the change-supportive behaviors of change recipients during the 2015 Chinese national football reform. An integrative conceptual framework () that captures CSB related managerial and contextual factors and CSB manifestations is applied to underpin the study and address the following two research questions:

Figure 1. Conceptual framework: change-supportive behavior-related contextual and managerial factors, and the manifestations of change-supportive behavior.

Research Question 1: What managerial and contextual factors affected the change recipients’ CSB during the 2015 Chinese football reform?

Research Question 2: How was the CSB manifested during the Chinese football reform?

2. Literature Review: Conceptual Framework

2.1. Change-Supportive Behaviour (CSB): A Panoramic View on the Conceptual Framework

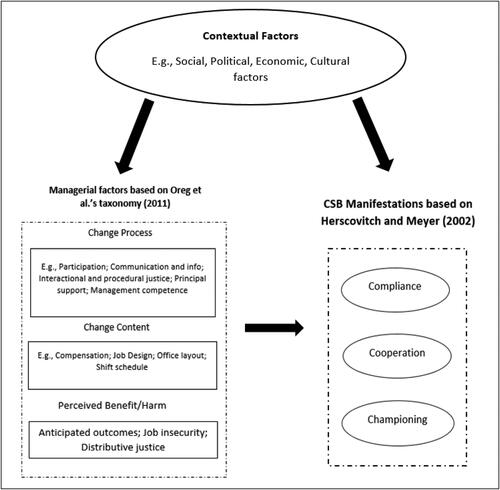

Change-supportive behaviour (CSB) refers to actions that employees take to actively participate in, facilitate, and contribute to a planned change initiated by the organization (Kim et al., Citation2011). To fully capture change recipients CSB during the 2015 Chinese football reform, this paper draws on an integrated conceptual framework comprising of three theoretical components, namely, managerial and contextual factors contributed to CSB as well as manifestations of CSBs, which will be detailed below.

The first theoretical component, the managerial factor, was drawn from Oreg et al. (Citation2011). It is necessary to point out that Oreg et al. (Citation2011, p. 466) original model identified three elements of the organizational change process: antecedents, explicit reactions, and change consequences. This study was particularly concerned with the antecedents, specifically the intra-organizational and managerial factors which affect change recipients’ behaviour was included in the framework. Explicit reactions and change consequences were not included in the framework because these concepts were theoretically irrelevant to the research objectives on supportive behavioural reactions and manifestations of CSB.

The second theoretical component of the framework concerns contextual factors that impact change recipients’ CSB. Despite the usefulness of Oreg et al. (Citation2011) typology, it failed to capture external factors such as the social, cultural, economic and political context in which the case was situated. Contextual factors are an important influencer in organizational change (Fahlén & Stenling, Citation2019), where they have potential to affect change management as well as individuals’ decisions to resist or accept a change (Welty-Peachey & Bruening, Citation2011). Contextual factors were, therefore, included in the conceptual framework.

The last component in the conceptual framework concerns manifestations of CSB, which are the change-supportive behavioural reactions as defined by Herscovitch and Meyer (Citation2002). Despite Oreg et al. (Citation2011) model mentioning ‘behavioural reaction’, it did not specify exactly how supportive behaviors might be manifested by change recipients. The three behavioural reactions defined by Herscovitch and Meyer (Citation2002) served as a useful typology to examine the CSBs in this study. Originally, there were four behavioural types identified by Herscovitch and Meyer (Citation2002), nonetheless ‘resistance’ is not a ‘supportive’ behaviour and was excluded. Previous sport management research has used this typology that has proved to be a useful lens in examining CSBs (e.g., Cunningham, Citation2006b; Cunningham & Sartore, Citation2010)

As summarised in , the developed framework provided a nuanced theoretical lens to address the research questions. Next, each of the three theoretical components as well as the rationales for the integration will be elucidated.

2.2. Managerial Factors Affecting Change Behaviors

Numerous scholars in sport management have examined change antecedents (Amis et al., Citation2002; Bloyce et al., Citation2008; Cunningham, Citation2002; Heinze & Lu, Citation2017; Welty-Peachey & Bruening, Citation2011). Oreg et al. (Citation2011) systematic taxonomy reviews managerial influences on the change process. This taxonomy consists of three elements: (1) the change process (e.g., participation, communication and information, interactional and procedural justice, principal support and management competence); (2) change content (e.g., compensation, job design, office layout, shift schedule); and (3) perceived benefit or harm (e.g., anticipated outcomes, job insecurity, and distributive justice).

Change process is defined as the progression of change that is characterized by a disrupted balance and an appearance of conflicts, chaos and/or integration of new ideas until it reaches a new balanced status quo (Oreg et al., Citation2011). Several common types of practice have been identified in the change process that can influence the change recipients’ behavioral reaction.

The first type of practice is participation. The participation of change recipients in the change process is likely to create a sense of agency, competence, and interpersonal trust over the changing setting (Oreg et al., Citation2011). Those who experience high levels of participation throughout the change process tend to accept and support the change. Communication about the change and the quantity and quality of information available to change recipients could also affect their behaviors (Legg et al., Citation2016). There is a positive correlation between the degree of openness and transparency of the change information to the change recipients on the one hand, and the level of support for the change on the other (Skille, Citation2011).

Second, interactional justice refers to the level of fairness and the treatment change recipients receive from decision makers (Oreg et al., Citation2011). This practice, combined with procedural justice and the procedures employed to implement decisions, can affect employee attitudes towards the change process (Cunningham, Citation2006a). For example, if the sport organization undertakes a process of restructuring without following a process that change recipients consider reasonable, change recipients are likely to display behaviors resistant to the change. In a similar sense, if the decision-making process for the change is not perceived to be transparent, less supportive behaviors will become evident throughout the change process (Logan & Ganster, Citation2007).

Third, principal support is known as the provision of resources such as financial and human resources by sport managers who, as change agents and opinion leaders, facilitate the change (Oreg et al., Citation2011). In particular, the amount, efficiency, and timing of support provided during the change process could have substantial implications for change recipients’ readiness to change (Lawrence & Callan, Citation2011).

Finally, change recipients’ perceptions of the management teams’ degree of competence in managing the change process can affect change recipients’ behavioral reactions. An illustrative example is a sport manager’s ability to address the issues raised from the change process by creating effective solutions. Failing to adequately address the situation will likely increase the level of change recipients’ stress, which can lead to negative behavior such as scepticism and demotivation (Vakola, Citation2016).

Change content is concerned with the nature or substance of the change initiative and is an important determinant of change recipients’ attitudes towards change (Oreg et al., Citation2011). The actual content that the change entails include the financial compensation recipients acquire during the change process, new job design, possible different office layouts or the shift in schedule that impact on employees’ attitudes and commitment to change (Oreg et al., Citation2011). In general, impact that the change content has on change recipients will vary and the reactions of individuals to such changes are often influenced by “how a specific change has touched their lives” (Self et al., Citation2007, p. 213).

Perceived benefit and harm are interpreted as an individual’s perception of the change process and the determination of whether the change outcome is favorable or unfavorable to an individual’s wellbeing (Oreg et al., Citation2011). Vakola (Citation2016) noted that the perceived outcome of the change could affect an individual’s readiness to change and concomitantly, their behavioral reactions. Bayraktar (Citation2019) argued that there is a positive correlation between the information the change recipients gather throughout the change process and change recipients’ understandings of what the change means for their job security. It is observed that during the organizational change process, a recipient’s likelihood to behave supportively is dependent on the opportunities and resources (e.g., time, money and skill) available to them (Ajzen, Citation1991). For instance, when a participant believes their chances of being promoted to a senior manager position is generally high based on the perceived information, he or she is more likely to display actions that support the change process.

2.3. Contextual Factors Affecting Change Behaviors

In addition to managerial factors, the external context in which investigated organizations reside can also impact change recipients’ CSB. The potential impact can be broadly viewed as a demonstration of structure over agency, that is, the institutional context (structure) can transform organizational practices and structure as well as individual behaviors (agency) (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983; Houlihan, Citation2005). Prior sport management studies have explored the impact contextual factors have on the organizational change process from perspectives such as institutional pressure (e.g., Fahlén & Stenling, Citation2019; Slack & Hinings, Citation1992); perceived social and cultural pressures to perform or halt the change (e.g., Cunningham, Citation2008; Legg et al., Citation2016), as well as political pressure which can stem from dependent relationships with other organizations (e.g., Welty-Peachey & Bruening, Citation2011).

Ajzen (Citation1991) claimed that personal beliefs about the social world can influence an individual’s intention and thereby their actual behavioral engagement. For example, a number of studies suggest that individuals tend to foster the loyalty to others who are important to them by acting in a compliant way (e.g., Jeon & Lee, Citation2006). In an organizational change context, these beliefs usually originate from either the extra- or the intra- organizational environment (e.g. Oliver, Citation1991). Extra-organizational norms include institutionalized values and traditions from the community, the political environment, and the socio-economic status of individuals supporting the change (Pollis & Pollis, Citation1970). These norms reflect how most group members behave and therefore, lead to acceptance or rejection in a group (Guimond et al., Citation2018).

The three elements of Oreg et al. (Citation2011) taxonomy of managerial change factors are utilized in this research because they provide an appropriate theoretical lens to delve into the internal managerial reasons behind employees’ reactions to change. Contextual factors provide insights into the external factors that affect organizational modus operandi and structure as well as individual change behaviors.

2.4. Manifestations of Change-Supportive Behaviors

In addition to aforementioned managerial and contextual factors that play an integral part in the change process, manifestations of change-supportive behaviors are also noteworthy. Change recipients can exhibit positive or negative reactions to change. Herscovitch and Meyer (Citation2002) outlined three types of supportive behaviors that are associated with change commitment: (1) compliance; (2) cooperation; and (3) championing.

Compliance refers to the minimal level of support required from change recipients to facilitate the change process (Herscovitch & Meyer, Citation2002). It depicts the change recipients’ “instrumental involvement” in a change process for specific extrinsic rewards (O’Reilly & Chatman, 1986, p. 493). Cooperation is known as the behaviors supportive of change and a willingness to accept modest sacrifices (Herscovitch & Meyer, Citation2002). Championing is considered the most active change-supportive behavior. This behavior is demonstrated by a change recipient’s enthusiasm and willingness to considerably sacrifice considerably personal benefits to promote the value of the change to others (Kim et al., Citation2011).

In short, the integrated conceptual framework is comprised of three theoretical dimensions with one addressing the managerial factors (Oreg et al., Citation2011), one addressing contextual factors, and the other emphasizing the manifestations of CSB (Herscovitch & Meyer, Citation2002). While other theoretical perspectives, such as the institutional theory (Oliver, Citation1991), could provide an alternative lens to look at the change process, we argued that this three-dimensional integrated approach adopted for this study potentially provides a more detailed and diagnostic approach to understanding the managerial and contextual motivators as well as manifestations of the change recipients’ supportive behaviors during the change process.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Context

The study was conducted against the background of Chinese public sector reform efforts led by the central government (Chinese State Council, Citation2015). shows the timeline of the national football reform that occurred between 2015 and 2017. In 2015, the national governing body of football (i.e. the Chinese Football Association, CFA) was required to be decoupled from the superior government body (i.e., General Administration of Sport of China, GASC) to operate as an autonomous organization (Peng et al., Citation2019). In the following two years, similar organizational change was sequentially implemented at the local level. To elaborate, 44 provincial-level football associations were also instructed to be separated from their local sport bureaus to become independent organizations. Additionally, 46 professional football clubs were also restructured according to the CFA policies. Data collection was conducted two years after the change had been announced (i.e., 2017) to ensure that that the change process would have been underway in the majority of the local FAs and clubs.

Table 1. The timeline of the 2015 Chinese national football reform.

A salient characteristic of this change was the new managerial rights devolved by the GASC to the CFA. These managerial rights included a range of change content for both the CFA and its local member associations, ranging from organizational structure, project management, finance and salary control, to human resource and international partnership management (Chinese State Council, Citation2015). As a consequence of the managerial rights devolved by the GASC to facilitate the change, all employees in the CFA and local football associations were able to choose whether to stay within the CFA or their local member associations and accept the change, or to leave their respective organizations. Employees who chose the latter option the GASC reallocated them to a work in an equivalent position with a similar sport organization affiliated to the GASC (with equivalent salary scale), so there was no financial pressure for those who chose to leave.

3.2. Research Design

This study employed a case embedded study design because it was intended to gain a “holistic understanding of a set of issues, and how they relate to a particular group, organization, sports team, or an individual” (Gratton & Jones, Citation2004, p. 119). Yin (Citation2018) suggested that a case study design has distinctive value in answering the ‘what’, ‘why’ and ‘how’ questions, because this research design enables investigators to focus on a case and retain a holistic and real-world perspective. An embedded case study design (Yin, Citation2018) was adopted for this study because this research does not only focus on the organizational change of the CFA as the main case, but also examines other units of analysis such as local member football associations as well as commercial football clubs in the change setting.

3.3. Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews were used as the primary data collection technique to gain a deep understanding of the motivation for, and demonstrations of, change recipients’ behaviors. A total of 29 semi-structured interviews were conducted with employees from the CFA local member football associations and professional football clubs across three top divisions in 2017. The reason that interviews were conducted two years after the reform and not earlier (i.e., in 2015 or 2016) was that the reform process was gradually implemented. Stakeholders such as provincial-level football governing bodies that did not become involved in the process until 2016 and in some cases, not until 2017 (see ). Conducting interviews too early would have not allowed the stakeholders to provide first-hand accounts of the experiences in the reform process. Twelve face-to-face interviews were conducted with the CFA employees, seven video interviews with staff of provincial football associations, and ten video interviews with staff of professional football clubs. The majority of participants were over the age of 40 years of age, in senior management roles (e.g., directors of departments), and were predominately male (95%) (see ).

Table 2. A summary of the profile of interviewees.

Corresponding to the accessibility of interviewees, a mixed sampling approach was adopted, comprised of purposive and snowball sampling. Purposive sampling is, in nature, a non-probability form of sampling used to locate all possible cases of a highly specific and difficult-to-reach population (Bryman, Citation2012). A purposive sampling was applied within the CFA to understand the impact organizational change at the national level. Following this, a snowball sampling approach was employed based on referrals recommended by the CFA officials to identify interviewees at the provincial level (local member associations and professional clubs) (Bryman, Citation2012). provides a detailed summary of the interviewee profile.

Interview questions were asked in a semi-structured manner, that is, in response to the inquiring process and the informants’ behaviour (Bryman, Citation2012). This approach enabled a natural flow of conversation between the researcher and the interviewee (Bryman, Citation2012). Each interviewee was asked to reflect on the reform process, from its initiation in 2015 up until the current time. The aim was to gain a deep understanding of the change process, the change content, and change recipients’ individual intentions to support or resist the change. Interviews were digitally recorded and ranged in length from 30 to 120 minutes. For confidentiality reasons, respondents were assigned pseudonyms (i.e., R1, R2, R3, R4…R29). All data was collected in Chinese. The interviews were first transcribed verbatim, and participants were given the opportunity to verify their transcripts for accuracy. Transcripts were then translated into English by the lead author and back translated by the fifth author to ascertain linguistic consistency. The data were finally imported into NVivo 12 for analysis.

3.4. Data Analysis

Data analysis followed a three-step content analysis model recommended by Attride-Stirling (Citation2001). This approach was sequential and included the following steps: (1) the reduction or breakdown of text based on the conceptual framework (see ); (2) exploration of the text for new themes; and (3) integration of themes from both Step One and Step Two. In specific terms, the initial coding process started with comparing and contrasting the interview transcripts. The conceptual framework identified in was used to frame the coding process, which led to a total of seven codes being created by the end of Step One. These codes were (1) communication; (2) management competence; (3) principal support; (4) participation; (5) compliance; (6) championing; and (7) cooperation. Then, the initial coding framework was applied to the textual data to dissect it into text segments and look for new themes that did not fit into the initial coding framework. After the refinement of these themes, further grouping and condensing were conducted until three main themes emerged. The three themes were: (1) managerial factors affecting change recipients’ behavior; (2) contextual factors affecting change recipients’ behavior and (3) manifestations in change recipients’ change-supportive behaviors, as presented in . ‘Trustworthiness’ was pursued through meeting standards of confirmability and credibility by using triangulation of data types and respondents, transparency of the methodological approach, as well as member checking of the findings (Bryman, Citation2012).

4. Findings

4.1. Managerial Factors Affecting Change Recipients’ Behaviour

Five managerial factors (communication channels, participating in decision-making, leaders’ commitment, principal support, and management competency) were identified to have affected change recipients’ attitudes and intentions toward change when interacting with their management team during the change process. The management team in this case mainly refers to the CFA.

First, communication channels were considered crucial for change recipients. Specifically, creating more channels of communication with the management team in the change process can increase change recipients’ readiness for and acceptance of the change, as noted in the following quote:

The CFA has constantly organized meetings with us since the reform… and I was often invited to these meetings. I felt that we have more opportunities to speak out our minds than before… you can see they (CFA) were making efforts to make some changes, which makes me feel worthwhile to participate in the change… (R14)

Every year (since the reform), the CFA would organize departmental or disciplinary meetings and invite representatives from the counterparts of member associations and clubs to attend… All attendees would sit together, talk about the implementation process and give their honest opinions about what went wrong and how it could be improved. I think it is an example of good practice to communicate regularly with key stakeholders in the change process … and none of this had happened before…

However, some respondents still demonstrated negative attitudes towards the change despite communication between the management team and the change recipients. This was particularly related to the second basic theme – participation in the decision-making process. This factor was notable when the management team dismissed change recipients’ feedback without explanation. This led to a heightened level of frustration and resistance towards the change.

Yes, we have more channels to voice our opinions. In fact, these issues were often brought up in those meetings with the leaders… but, it is useless because all the decisions made were top-down I think, and our feedback makes no difference… this is frustrating and not really encouraging for me to further participate in these meetings. (R19)

Another respondent provided an interesting example to illustrate this point:

Despite the opportunities to provide suggestions, it is a completely different story when it comes to the CFA choosing to adopt these suggestions or not. Just as my old manager said, if he were to offer the suggestion which were made to the CFA at meetings like these ten years ago, those suggestions could have still been of great use today… I think there is no problem for us to speak at these occasions, but if there is no explicit impact afterwards, what is the point? (R13)

The third basic theme concerns the leaders’ commitment to change perceived by the change recipients in the change process. The commitment to improving Chinese football at all levels, which was demonstrated by the leaders within the CFA, have had an impact on the change recipients’ attitudes toward the change as illustrated in the following quoted:

Football has never been prioritised on the national policy agenda before… This really demonstrates the determination of the leaders in improving Chinese football. We are very motivated by this level of commitment and support…and because of this commitment, we are more motivated to support the change… (R3)

All of the member associations and clubs are watching the CFA now – how the change is carried out in the CFA, what new regulations have been issued, and other areas… as long as the CFA is committed to the change, all of us will follow its steps and undertake our own responsibility to ensure that the change is successful. (R15)

We believe that to ensure local FAs reform a success, the CFA should prepare a systematic supporting policy along with the announcement. Only in that way, we can be confident about the separation of provincial-level FAs from their governments. However, since 2015, there has not been much support coming from them, except a few actions taken in 2016. (R15)

The quote suggested that change recipients from local FAs were seeking support from the management team. In particular, change recipients tended to be more confident towards the change when the essential support was furnished. Financial support is particularly important for some organizations to ensure their survival in the reform process. R13 mentioned the benefit of receiving the support:

The CFA has provided some financial support to national youth training base, which includes an annual investment of one million yuan into five reserve teams. This support is beneficial for local FAs because we can keep these bases running without disruption.

What we have been doing in the past two years is simply implementing whatever the higher-level superiors asked us to do… other member associations have been receiving investments from their provincial-level governments, but this is not the case for our organization. We even had to “borrow” staff from other organizations to run events at occasions… after the reform, we (will) have to “beg on the street” …

For those economically well-developed provincial divisions, the separation of the football governing system from their government is not a puzzling problem. However, for us, it is quite challenging because we are often short of financial resources. Hence, when we do not receive sufficient support from the management team, I do worry about our survival in the change process. (R19)

The last basic theme is associated with the management competency perceived by the change recipients during the reform. To elaborate, the findings revealed that the perceived competency to lead and manage the change process can affect the recipients’ attitude towards the change. This was highlighted by Respondent 6 who stated that:

Previously, the management team was a bit unorganized and unspecialised and now, the fact that more specialised employees have been recruited to the relevant posts has enabled the overall competency and efficiency to be significantly enhanced. This change was what the managers had promised in the beginning of the reform and its realisation is very assuring and motivating for us to be part of this course… (R6)

Our leaders have set up this rule of “banning any forms of signing fees” which makes me think it is too amateur an action. Although the intention is undoubtedly good for the transfer market (to avoid immoderate investment), when reading these policies, you just cannot help wondering about the competency of the people responsible for making them and worrying about the future… (R26)

When compared with Oreg et al. (Citation2011) taxonomy (see above), the key difference revealed from the data of this study was that the perceived leaders’ commitment to change by the change recipients was often mentioned. That is, the more committed the leader’s perceived commitment to the change, the more supportive change recipients were towards change. This finding supports previous research that has shown that if organizational leaders are willing to devote resources (e.g., human or financial) to the change initiative, change recipients are more likely to believe that the change will succeed and therefore are willing to positively participate in the change process (Ahmad & Cheng, Citation2018).

Similarly, Cunningham (Citation2006a) and Herscovitch and Meyer (Citation2002) have previously noted the positive impact of leader commitment on change recipients’ behaviors. Interestingly, although the change content mentioned by the respondents (e.g. the change in policies, organizational structure, and ways of interacting with other stakeholders) was different from the change content outlined by Oreg et al. (Citation2011), what was evident in the data was the marked impact of these changes upon the recipients’ attitude towards change. The findings also showed that individual change in the attitude towards the reform is in accordance with their perception of the benefits and harm derived from the change process. In specific terms, when the change recipients believed that the change process was conducive to their individual career, they tended to express a positive attitude towards change.

4.2. Contextual Factors Affecting Change Recipients’ Behavior

Two contextual factors associated with the provincial-level government and/or the central government (including the GASC and State Council) were identified to have influenced change recipients’ behaviors: an amenable football environment, and the perceived political pressure to change.

The first theme describes how the amenable environment was a welcoming and healthy football development atmosphere that affected change recipients’ behavior. Respondent 25 highlighted:

From what I see, the domestic football environment has become healthier and it makes me want to continue working in this field. The previous large sum of capital investment certainly was appealing, yet it inflated the (capital) bubble dangerously. The CFA did not allow this to worsen and has formulated relevant policies in a timely way to intervene and safely guarded the development… (R25)

The reform has prompted many changes in the past years. I think we are following the right direction. For instance, the emphasis on youth training and directing clubs to invest immoderately have made the football environment healthier than before. (R10)

When the Reform Plan was released in 2015, I was feeling so encouraged. I believe that it is the prime time for Chinese football as well as my own career. Since President Xi is so supportive of football development, I believe that politicians working in provincial-level governments will take the same interest in developing football and create more opportunities for us. (R11)

As member associations, we have to comply with the CFA to be decoupled from the government system – there is no negotiation. Our leaders required our member associations to start the change process in 2016. However, because of various difficulties most notably the shortage of money and staff, we were just not able to start then… there was considerable pressure on us. (R17)

… we need to be careful with what we choose… For a club member, no matter how the reform turns out, we have to adhere to the direction of the national policy. We are a state-owned club, and state-owned clubs always comply with the Party. The CFA follows the Party as well. Everybody shares the same direction, and this is why we choose to support the reform and we will continue doing so in the future… (R20)

To be honest, I think that member associations are quite politically oriented. Let me give you an example. In the past, whenever the CFA decided to promote new football programmes and no matter whether it is in our benefit or not, we never hesitated to follow them (the CFA) and provided the best support we could…This time, it is the same. (R13)

A key insight from the findings was that the respondents interpreted supporting the change as a way of demonstrating their political orientation. It was found that change recipients perceived political pressure to support the change, but no explicit consequences were indicated should they choose not to support the change process.

The findings suggested that the recipients’ change-supportive behaviors were also attributed to contextual factors. A generally positive attitude towards the idea of football reform was found because it was considered beneficial to overall football development in China. In other words, an amenable environment created by the Chinese government had boosted change recipients’ confidence in supporting and participating in the football reform. Moreover, another distinctive factor was identified as leading to the change recipients’ supportive behaviors, namely, the perceived pressure to align with the political agenda of the government. The findings showed that change recipients who perceived a necessity to conform to the central government or the CCP’s change goals were more likely to support and engage in the change process. The Chinese government’s policy agenda represents the Party’s ideology, which has a long tradition of high levels of political intervention in the operation of governmental or non-governmental sport organizations. As a result, this political pressure was a critical factor that determined the change recipients’ decision to support the change.

4.3. Manifestations of Change Recipients’ Change-Supportive Behavior

The third organizing theme was the manifestations in change recipients’ change-supportive behaviors. Supportive behaviors of change were manifested by: (1) showing understanding of the change but pessimistic about the outcome; (2) supporting the change and being willing to take risks; and (3) supporting the change and actively seeking alternative solutions. The first supportive behavior was characterized by change recipients’ awareness of the politically correct nature to accept the change but a relatively lack of confidence about the implementation of change. This is explained by the different challenges faced by the change recipients as noted by Respondents 17 and 19:

We understand that the reform is good for Chinese football development and of course I am happy to see some changes in the football system. However, things can be rather complicated in China because the economic conditions in each province vary considerably. For us, we have always struggled financially. All we can do is to implement what we have been told to do…Once separated from the government, we probably can no longer survive. (R17)

I am supportive of the change because it is good for our country’s football development. However, the idea of football associations to be separated from government is daunting because once we are separated, we are no longer the authority and we will be like a civil organization with no power… Anyway, I suppose that this is the reform trend in our country and all we can do is to strive to comply with the policy. (R19)

Change recipients who were supportive of change and were willing to take some (though not considerable) risks were representative of the second type of supportive behavior of the change. Almost all participants demonstrated their understanding of the football reform in benefiting Chinese football, some respondents even expressed their willingness to take risk:

… football has never been prioritized on the national policy agenda before … this reform is inexorable… Although we are all exploring in this journey without knowing where the future heads, we do support the change programme and are willing to take some risks for a better future… (R3)

My boss has invested more money in the club these two years because he believed that the national policy would be a good drive for the development of Chinese football. However, now they are starting to wonder whether to withdraw their investment because there is almost zero turnover which is a negative sign for an enterprise in the long term. (R26)

The final form of supportive behavior was supporting the change by taking considerable risks and actively seeking alternative solutions when problems occurred. Compared to the previous two types of reactions, this form of supportive behavior appeared to be the most engaged behavior in the change process. Change recipients demonstrated more enthusiasm and willingness to champion the change, rather than passively comply with the orders from the senior management team. When exchanging views on the common challenge of establishing reserve teams in clubs because of the lack of talent resources, a club manager commented how he sought innovative ways to champion the change:

Our potential young players are based in schools and because we cannot communicate with the education system directly, we decided to write a proposal to the local government and ask them to coordinate with local schools. And it is actually working… We now manage to launch conversations with local schools to promote a joint project on youth team development. (R24)

There are approximately ten member-associations in my region, and many of us are striving to support the reform. Some places even subsidize football development with money earned elsewhere. We are in deficit of 80,000 to 100,000 yuan now, but these are “normal”. We all should sacrifice something for our country. (R14)

The second type of manifestation, supporting the change and being willing to take risks, was associated with a higher level of cooperative behavior. Herscovitch and Meyer (Citation2002) suggested that change-supportive behaviors are demonstrated by a willingness of change recipients to take risks, as such, this was seen as cooperation behavior (see ). Cooperative intentions were driven by the change recipients’ perceived personal benefit associated with the reform. This personal benefit can be sourced from the positive development of Chinese football, which would provide a platform for career advancement. Although the reform may be characterized by short-term risks and challenges for these change recipients, there was a willingness to accept these risks and challenges.

The final type, supporting the change and actively seeking alternative solutions, was the most supportive behavior identified. According to Herscovitch and Meyer (Citation2002), this type of behavior can be defined as championing (see above), which is a demonstration of change recipients’ strong intentions and enthusiasm to support the change by championing the change process. These change recipients were not only ready to take risks, but also willing to actively undertake responsibility of what they were asked to do. The data showed that these change recipients demonstrated a passion for the change by actively seeking solutions when problems occurred. They did not wait for instructions to solve problems. Instead, they utilized the resources available to them to champion the change agenda.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

The purpose of this paper was to examine the managerial and contextual factors leading to change recipients’ behaviors, as well as provide insight into the manifestations of the change-supportive behaviors during the 2015 Chinese football reform. To date, the factors leading to various change-supportive behaviors and the manifestations of these behaviors have remained an understudied terrain. By analyzing the change-supportive motivators and behaviors, this paper contributes to theory on change-supportive behaviors in two ways. First, it identified managerial and contextual factors, which led to the change-supportive behaviors. This contribution provides a deeper understanding of the human experience in the change process and how various factors can positively or negatively affect individual behavioral reactions. In particular, the data provide a novel explanation for change-supportive behaviors – the pressure for change recipients to align with the political agenda of the ruling Communist Party.

Second, an integrated conceptual framework was developed to shed light on those managerial and contextual factors that influence the change process and the manifestations of change-supportive behaviors. This framework also synthesized Oreg et al. (Citation2011) and Herscovitch and Meyer (Citation2002), which combined to highlight the challenges and complexities with which the organizational change process can be confronted within a non-western political context.

This research has a number of noteworthy practical implications for sport managers to consider when implementing change. The aforementioned integrated conceptual framework advanced in this research provides sport managers with a change management tool to understand, assess and facilitate the change process. Specifically, by understanding how managerial factors can facilitate positive attitudes towards change, sport managers can create opportunities for the voice of employees to be heard throughout the change process. Moreover, for sport managers implementing similar reforms among other Chinese sports organizations, it is worthy of considering engaging change recipients in the decision-making process and providing timely and sufficient support for them to overcome the challenges of the change process.

This research has opened a number of possibilities for future research. First, the conceptual framework developed can be applied in different cultural and political contexts to determine if it captures the vagaries and complexities of change in different settings. Second, future research evaluates the interrelationship among managerial and contextual factors and manifestations of CSB using quantitative data to further explore the causal relationships between each of the CSB influencers and individual manifestation type. Third, a more in-depth exploration of psychological factors that influence change recipients’ attitudes and behaviors throughout the change process would be effective in informing change managers in establishing support for the change process. This exploration could be timely because sport organizations are expanding into new markets (Giulianotti & Robertson, Citation2007) and concomitantly, there is a growing recognition that successful change requires change managers to pay attention to the psychological well-being of employees throughout the change process (Kim et al., Citation2019).

This research is not without its limitations. First, due to the sensitivity of the topic, to approach personnel who had ‘resisted’ the reform was not within the realm of possibility. Therefore, the interviewees participated in this study were those who were supportive of the reform. However, the impact of this limitation has been alleviated by capturing the variations within the change-supportive behaviors and analyzing the reasons why certain change recipients were not optimistic about the reform. Second, given the case study design, data from this study can only reflect the change recipients’ attitudes and behaviors at a certain period of time during the change process. Finally, considering the relatively distinctive Chinese context, the transferability of the findings are limited, which is an innate feature of the case study design.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Qi Peng

Qi Peng (Ph.D., Loughborough University). Lecturer, Department of Economics, Policy and International Business, Manchester Metropolitan University. Her research interests include sport policy and management, with a particular interest in studying Chinese football.

James Skinner

James Skinner (Ph.D., Victoria University), Professor of Sport Business and Director of the Institute for Sport Business, Loughborough University London. James has conducted key research for national and international governing bodies, as well as professional sporting organisations and the Australian Sports Commission. His research interests are in four distinct areas: Organisational Change, Culture and Leadership in Sport; Doping in Sport; Sport and Social Capital; Research Design and Methods for Sport Business.

Barrie Houlihan

Barrie Houlihan (Ph.D. University of Salford), Emeritus Professor Sport Policy at Loughborough University and Visiting Professor at the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences. His main research interests are in the policy process for sport particularly in the areas of doping, and sport development.

Lisa A. Kihl

Lisa A. Kihl (Ph.D., University of British Columbia), Associate Professor of sport management at the University of Minnesota, USA. Her research focuses on corruption in sport, athletes’ roles in sport governance, corporate social responsibility, and leadership. She has published her work in the Journal of Sport Management, European Sport Management Quarterly, Sport Management Review, and Administration and Society.

Jinming Zheng

Jinming Zheng (Ph.D., Loughborough University). Lecturer, Department of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation at Northumbria University. Jinming’s research interests mainly comprise elite sport policy and development, Olympic medal distribution and configuration analysis particularly for non-major nations and nations’ Olympic strategy.

References

- Ahmad, A. B., & Cheng, Z. (2018). The role of change content, context, process, and leadership in understanding employees’ commitment to change: The case of public organizations in Kurdistan region of Iraq. Public Personnel Management, 47(2), 195–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091026017753645

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Amis, J., Slack, T., & Hinings, C. R. (2002). Values and organizational change. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 38(4), 436–465. https://doi.org/10.1177/002188602237791

- Attride-Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 385–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/146879410100100307

- Bayraktar, S. (2019). How leaders cultivate support for change: Resource creation through justice and job security. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 55(2), 213–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886318814455

- Bloyce, D., Smith, A., Mead, R., & Morris, J. (2008). Playing the game (plan)’: A figurational analysis of organizational change in sports development in England. European Sport Management Quarterly, 8(4), 359–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184740802461637

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Chinese Football Association. (2015). The Chinese Football Association Adjustment Reform Plan. http://www.thecfa.cn/ggwj/20150817/20140.html

- Chinese Football Association. (2016). Suggestions on Local Football Associations’ reform and adjustment. http://www.jxszqxh.com/a/zuqiugaige/20190522/373.html

- Chinese State Council. (2015). The overall program of football reform and development. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-03/16/content_9537.htm

- Cunningham, G. B. (2002). Removing the blinders: Toward an integrative model of organizational change in sport and physical activity. Quest, 54(4), 276–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2002.10491779

- Cunningham, G. B. (2006a). Examining the relationships among coping with change, demographic dissimilarity and championing behaviour. Sport Management Review, 9(3), 253–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1441-3523(06)70028-6

- Cunningham, G. B. (2006b). The relationships among commitment to change, coping with change, and turnover intentions. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 15(1), 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320500418766

- Cunningham, G. B. (2008). Creating and sustaining gender diversity in sport organizations. Sex Roles, 58(1–2), 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9312-3

- Cunningham, G. B. (2009). Understanding the diversity-related change process: A field study. Journal of Sport Management, 23(4), 407–428. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.23.4.407

- Cunningham, G. B., & Sartore, M. L. (2010). Championing diversity: The influence of personal and organizational antecedents. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40(4), 788–810. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00598

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Collective rationality and institutional isomorphism in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

- Fahlén, J., & Stenling, C. (2019). ( Re)conceptualizing institutional change in sport management contexts: The unintended consequences of sport organizations’ everyday organizational life. European Sport Management Quarterly, 19(2), 265–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2018.1516795

- Giulianotti, R., & Robertson, R. (2007). Sport and globalization: Transnational dimensions. Global Networks, 7(2), 107–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2007.00159

- Gratton, C., & Jones, I. (2004). Research methods for sport studies. Routledge.

- Guimond, F., Brendgen, M., Correia, S., Turgeon, L., & Vitaro, F. (2018). The moderating role of peer norms in the associations of social withdrawal and aggression with peer victimization. Developmental Psychology, 54(8), 1519–1527. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000539

- Heinze, K. L., & Lu, D. (2017). Shifting responses to institutional change: The national football league and player concussions. Journal of Sport Management, 31(5), 497–513. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2016-0309

- Herscovitch, L., & Meyer, J. P. (2002). Commitment to organizational change: Extension of a three-component model. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3), 474–487. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.474

- Houlihan, B. (2005). Public sector sport policy: Developing a framework for analysis. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 40(2), 163–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690205057193

- Jeon, S. Y., & Lee, S. G. (2006). The effect of changes in attitude and subjective norm on treatment compliance in hypertension patients. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research, 11(3–4), 265–287. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9861.2007.00009

- Kihl, L. A., Leberman, S., & Schull, V. (2010). Stakeholder constructions of leadership in intercollegiate athletics. European Sport Management Quarterly, 10(2), 241–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184740903559917

- Kikulis, L. M. (2000). Continuity and change in governance and decision making in national sport organizations: Institutional explanations. Journal of Sport Management, 14(4), 293–320. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.14.4.293

- Kikulis, L. M., Slack, T., & Hinings, B. (1992). Institutionally specific design archetypes: A framework for understanding change in national sport organizations. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 27(4), 343–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/101269029202700405

- Kim, T. G., Hornung, S., & Rousseau, D. M. (2011). Change-supportive employee behavior: Antecedents and the moderating role of time. Journal of Management, 37(6), 1664–1693. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310364243

- Kim, M., Kim, A. C. H., Newman, J. I., Ferris, G. R., & Perrewé, P. L. (2019). The antecedents and consequences of positive organizational behavior: The role of psychological capital for promoting employee well-being in sport organizations. Sport Management Review, 22(1), 108–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.04.003

- Lawrence, S. A., & Callan, V. J. (2011). The role of social support in coping during the anticipatory stage of organizational change: A test of an integrative model: Role of social support during organizational change. British Journal of Management, 22(4), 567–585. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2010.00692

- Legg, J., Snelgrove, R., & Wood, L. (2016). Modifying tradition: Examining organizational change in youth sport. Journal of Sport Management, 30(4), 369–381. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2015-0075

- Logan, M. S., & Ganster, D. C. (2007). The effects of empowerment on attitudes and performance: The role of social support and empowerment beliefs. Journal of Management Studies, 44(8), 1523–1550. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00711

- O’Boyle, I., & Shilbury, D. (2016). Exploring issues of trust in collaborative sport governance. Journal of Sport Management, 30(1), 52–69. https://doi.org/10.1123/JSM.2015-0175

- Oliver, C. (1991). Strategic responses to institutional processes. Academy of Management Review, 16(1), 145–179. https://doi.org/10.2307/258610

- Oreg, S., Vakola, M., & Armenakis, A. (2011). Change recipients’ reactions to organizational change: A 60-year review of quantitative studies. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 47(4), 461–524. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886310396550

- O’Reilly, C. A., & Chatman, J. (1986). Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: The effects of compliance, identification, and internalization on prosocial behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 492–499. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.492

- Peng, Q., Skinner, J., & Houlihan, B. (2019). An analysis of the Chinese football reform of 2015: Why then and not earlier?International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 11(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2018.1536075

- Pollis, N. P., & Pollis, C. A. (1970). Sociological referents of social norms. The Sociological Quarterly, 11(2), 230–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.1970.tb01447

- Saxton, T. (1995). The impact of third parties on strategic decision making: Roles, timing and organizational outcomes. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 8(3), 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534819510090150

- Self, D. R., Armenakis, A. A., & Schraeder, M. (2007). Organizational change content, process, and context: A simultaneous analysis of employee reactions. Journal of Change Management, 7(2), 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697010701461129

- Skille, E. Å. (2011). Change and isomorphism — A case study of translation processes in a Norwegian sport club. Sport Management Review, 14(1), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2010.03.002

- Slack, T., & Hinings, B. (1992). Understanding change in national sport organizations: An integration of theoretical perspectives. Journal of Sport Management, 6(2), 114–132. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.6.2.114

- Vakola, M. (2016). The reasons behind change recipients’ behavioral reactions: A longitudinal investigation. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 31(1), 202–215. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-02-2013-0058

- Welty-Peachey, J. W., & Bruening, J. (2011). An examination of environmental forces driving change and stakeholder responses in a football championship subdivision athletic department. Sport Management Review, 14(2), 202–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2010.09.002

- Xinhuanet. (2017). The National Football Management Centre annulled. http://www.xinhuanet.com/2017-01/06/c_1120262358.htm

- Yin, R. (2018). Case study research and applications design and methods (6th ed.). Sage.

- Zheng, J., Lau, P. W. C., Chen, S., Dickson, G., De Bosscher, V., & Peng, Q. (2019). Interorganizational conflict between national and provincial sport organizations within China’s elite sport system: Perspectives from national organizations. Sport Management Review, 22(5), 667–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.10.002