ABSTRACT

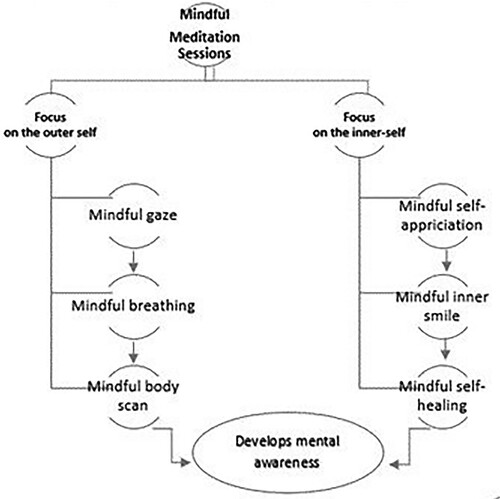

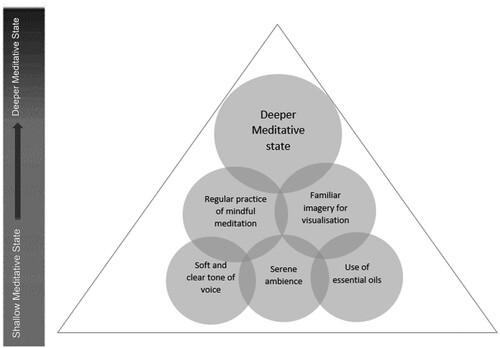

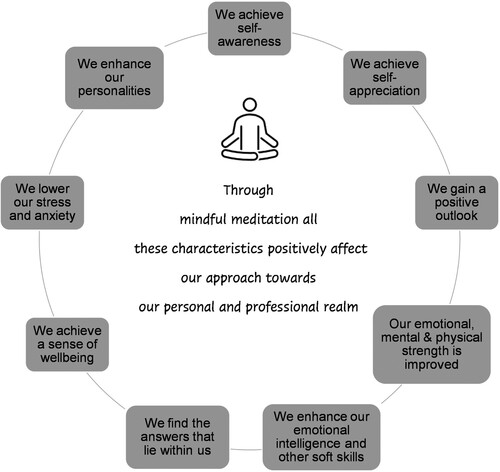

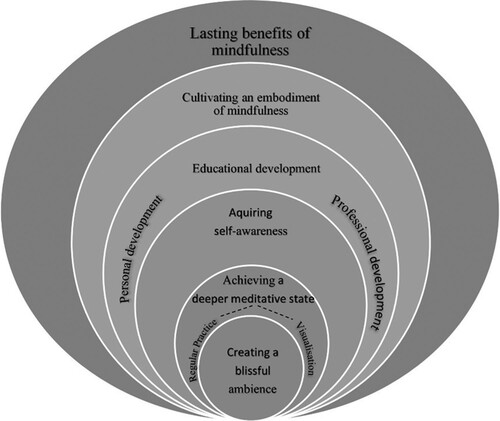

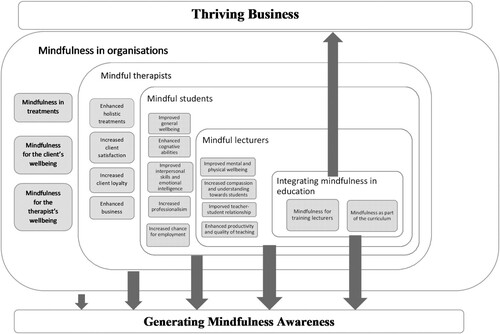

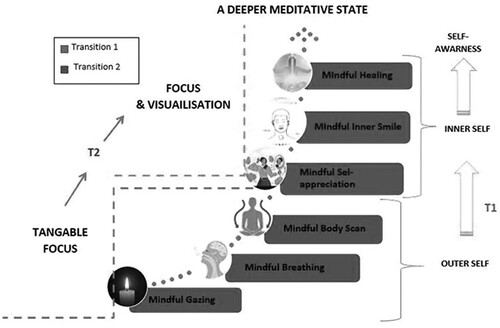

This study explores the integration of mindfulness and aromatherapy-enhanced mindfulness in vocational education to help educators and beauty therapy students better manage their stress and enhance their personal and professional wellbeing. Moreover, it focuses on understanding the applicability of mindfulness within the beauty industry and its impact on business. This research opted for a qualitative narrative inquiry methodology using thematic narrative analysis to examine the experiences of three vocational educators and three beauty therapy students from a vocational college in Malta. Moreover, two local beauty salon owners were also chosen to participate in this study. The findings showed that mindfulness enhanced the wellbeing of educators and beauty students, improving their work performance and personality. Additionally, mindfulness can potentially improve the service provided, clients’ wellbeing, and beauty therapists’ wellbeing. A total of five models emerged from this study. Model 1 illustrates the impact of one's surroundings on their mindfulness experience. Model 2 shows a set of interconnected requirements that facilitate a deeper meditative state. Model 3 demonstrates how achieving self-awareness enhances our wellbeing. Model 4 offers a framework for meaningful and effective mindfulness practice. Model 5 illustrates how integrating mindfulness within the educational field can potentially lead to a thriving organisation.

Introduction

One's work, home, and personal issues can all be potential stressors (Payne & Donaghy, Citation2010). How stress affects a person depends on how one responds to the stressors created by the stressful event (Pitman, Citation2019). Therefore, learning to destress is crucial; otherwise, stress build-up will negatively affect one's overall health (Lauren, Citation2017; Pitman, Citation2019).

Various researchers consider teaching a high-stress job compared to some other professions (Green, Citation2021; Redín & Erro-Garcés, Citation2020). Therefore, educators will likely suffer from stress-related conditions (Worth & Van den Brande, Citation2019). The symptoms of stress also affect students. The Richmond Foundation (Malta) reports that the demand for their services has increased by over 1000% in the past two years. According to the Youth Mental Health Barometer, 70% of participating youths aged between 13 to 25 experience anxiety symptoms (Richmond Foundation, Citation2022). According to the OECD (Citation2017), students’ primary stress stems from the fear of failing, the worry of having challenging assignments and the intense pressure felt while studying. Although no studies were found to link these stressors to beauty therapy students specifically, they likely experience similar difficulties. Aspiring beauty therapists must be knowledgeable in both the theoretical and practical aspects of numerous face and body treatments. The beauty curriculum also encompasses subjects such as anatomy and physiology, dermatology, client handling and product marketing (Bredlöv, Citation2022; McKenzie et al., Citation2018).

Moreover, beauty therapy students are instructed to control their emotions to ensure clients receive a positive salon experience. They are taught that this enhances the therapist's quality of work, client satisfaction, and the salon's reputation (Bredlöv, Citation2022). However, suppressing one's emotions will inevitably impose additional stress, leading to emotional exhaustion and negatively affecting one's personal and professional life (Hanson, Citation2019; Yoo et al., Citation2014).

Therefore, as high-stress levels become a global concern, various educational institutions, professional sectors, and organisations have shifted their attention toward Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) therapies, such as mindfulness and aromatherapy, to help find some equilibrium (Brown, Citation2018; Soto-Vásquez & Alvarado-García, Citation2017; Tregenza, Citation2008; Yager, Citation2009).

Purpose of study

This study explores how integrating mindfulness or aromatherapy-enhanced mindfulness in vocational education can help educators and beauty students better deal with their stressors and thus gain a sense of wellbeing personally and professionally. Moreover, the study focuses on understanding the potential applicability of mindfulness in the beauty industry and its impact on business. The research questions underpinning this study are:

How can integrating mindfulness or aromatherapy-enhanced mindfulness into a vocational educational curriculum aid educators’ and beauty students’ stress management, and what influence can these practices have on their personal and professional lives?

What potential applicability does mindfulness have in the beauty industry, and what impact does it have on business effectiveness?

Research justifications

According to Farrell et al. (Citation2016), narrative researchers commence by addressing three kinds of justifications, namely:

Personal justification

This justification contextualises the personal experiences and positioning throughout the research process. This includes personal experience with mindfulness and aromatherapy, the beauty industry and vocational education.

Practical justification

This justification makes the need for the study visible through the participants’ narrative experiences (Clandinin, Citation2016). Since stress seriously threatens one's health (Brannon & Feist, Citation2007; Payne & Donaghy, Citation2010), this study intends to provide practical and feasible suggestions to aid the wellbeing of educators, beauty students, and salon workers. The recommendations also aim to enrich the educational system and enhance the beauty industry.

Social justification

This study aims to act as an agent for change, illustrating how mindfulness or aromatherapy-enhanced mindfulness can 1) serve as a stress management tool for educators and beauty students to improve their personal and professional lives, 2) its applicability within the salon to enrich the service and strengthen the business and 3) its contribution to developing a better society.

Research design

This research aims to draw meaning and understanding from the participants’ experiences. Thus, a qualitative narrative approach was chosen. To examine the told experiences, a thematic narrative analysis was used as it focuses on the “told” (Riessman, Citation2008). Tools for data collection tools include observations, field notes, the participants’ journals, individual interviews, focus groups and the researcher's reflexive journal.

Literature review

Defining wellbeing

In attempt to accurately define wellbeing, Dodge et al. (Citation2012) propose the following definition,

"Stable wellbeing is when individuals have the psychological, social, and physical resources they need to meet a particular psychological, social and /or physical challenge. When individuals have more challenges than resources, the see-saw dips, along with their wellbeing and vice-versa” (p.230).

Taylor (Citation2003) agrees with this definition, stating that not having the appropriate resources to meet the current challenges can cause various stressors.

Stress and anxiety

The body's perception of harm unconsciously generates a stress response (Pitman, Citation2019). Additionally, scientists have detected connecting mechanisms in the brain that naturally link stress with anxiety and depression (Science Daily, Citation2010). Taylor (Citation2003) states that sometimes the expectation of a stressor is more stressful than the event itself. Worryingly, anxiety symptoms can emerge without warning, causing significant disruption to one's life (Dobetsberger & Buchbauer, Citation2011). To this end, the use of mindfulness and aromatherapy are advocated for their ability to relieve stress and anxiety symptoms (Dias et al., Citation2017; Redstone, Citation2015).

What causes educators’ stress and anxiety

According to the National Education Association (NEA), 55% of educators contemplate leaving their profession due to burnout and stress (Walker, Citation2022). Studies indicate a significant overlap between burnout, stress, anxiety, and depression (Aydogan et al., Citation2009; Liu et al., Citation2021; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, Citation2020). The scoping review conducted by Agyapong et al. (Citation2022) found that various factors contribute to educators’ burnout, stress, anxiety, and depression, including gender, age, marital status, school infrastructure, teaching experience, workload, class size, subject taught, and job satisfaction. Similarly, an online survey conducted among Maltese educators revealed that disruptive behaviour, time constraints, and pressure to cater to differentiated learning are among their main challenges (Vella, Citation2018). To address these issues, researchers suggest collaborating with school boards, governments, and policymakers to develop and implement measures that improve educators’ personal and professional wellbeing (Agyapong et al., Citation2022; Cassar & Formosa, Citation2011).

What causes students’ stress and anxiety

Students have their fair share of ongoing day-to-day stressors (Pascoe et al., Citation2020). Statistics indicate that fear of getting poor grades, the worry of having complex assessments and the feeling of extreme tension when studying are the leading cause of students’ stress (OECD, Citation2017). Such stressors can negatively impact one's overall health, learning abilities, academic attainments, and employability. Therefore, it is crucial that students are taught how to better deal with stress (Pascoe et al., Citation2020).

Mindfulness

Mindfulness is defined by Kabat-Zinn (Citation2003) as “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment” (p. 145). Practising mindfulness allows individuals to better understand themselves, others, and their surroundings, contributing to a better social society (Brookes, Citation2014; Godfrey, Citation2018; Shapiro et al., Citation2016; Whieldon, Citation2016). It guides individuals to access a deeper inner self and achieve a higher state of consciousness by generating awareness of one's thoughts and promoting deep reflections (Biswas-Diener & Teeny, Citation2021; Shapiro, Citation2009; Sharma, Citation2015). According to Shapiro (Citation2009), mindfulness “seeps into daily life, bringing greater non-judgmental consciousness to everything that one does, feels and experiences” (p. 602).

Mindfulness practice aims to foster positivity, compassion, gratitude, and wisdom and is considered an acceptable tool for enhancing one's holistic wellbeing and overcoming challenging behaviour (Shapiro et al., Citation2016; Whieldon, Citation2016). Mainstream professionals also promote wellbeing through mindfulness events and programmes (Greenberg & Harris, Citation2012; Whieldon, Citation2016). However, it is argued that the intended outcome may differ when mindfulness is separated from its original traditions (McCaw, Citation2020). Nonetheless, Whieldon (Citation2016) reports that mindfulness has so many positive effects that this practice can only do good.

Neuroscience of mindfulness

MRI scans indicate that after an eight-week mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) programme, there was significant growth in the parts of the brain responsible for learning, retaining memory, regulating emotions, compassion and empathy. In contrast, the scans showed a decrease in the part of the brain that responds to flight or fight situations, thus concluding that regular mindfulness allows the individual to handle stressful events better, even when the stressors remain the same (Hölzel et al., Citation2011). However, Van Dam et al. (Citation2018) state that lack of clarity and difficulty of providing valid neuroimaging estimates limit MRI results.

The benefit of mindfulness in Vocational Education and Training (VET)

Mindfulness has gained recognition for having a positive influence on various aspects related to the educational system, namely the type of learning provided, the behaviour and attitude of both educators and students, as well as their wellbeing (Hyland, Citation2014; Karunananda et al., Citation2016; Weare, Citation2018). According to Hyland (Citation2014), introducing mindfulness practices to improve VET is far more promising than any strategy implemented in the past. Moreover, mindfulness is believed to provide the workforce with the necessary skills that target industry demands (Nixon, Citation2019).

Increased learning

Docksai's (Citation2013) findings indicate that the group of students that followed an eight-week mindfulness course increased their test scores by 16%. Based on these findings, the author concludes that mindfulness can positively affect students’ achievements by enhancing their concentration and decreasing stress and anxiety. Weare (Citation2018) agrees that when mindfulness is taught correctly, there is reliable proof that mindfulness increases cognition and executive function, improves behaviour, and enhances physical health.

Improved wellbeing

Various studies conclude that mindfulness in school curricula positively influences students and shows promising results in decreasing students’ stressors (Bamber & Schneider, Citation2016; Kuyken et al., Citation2013). According to Tang et al. (Citation2015), this outcome is due to an improved activity of the frontal asymmetry due to a significant improvement in blood flow to the brain. Furthermore, according to Sapthiang et al. (Citation2019), their findings indicate that integrating mindfulness-based interventions (MIB) in schools can not only aid adolescents’ mental wellbeing but can likewise improve that of educators and parents.

Enhanced behaviour and attitude

According to Moss et al. (Citation2017), mindful reflection enables the individual to reflect and respond adaptively on the spur of the moment, thus empowering the individual to respond rather than react to a challenging situation. The authors link reflective mindfulness to becoming aware of internal and external experiences, thus developing interpersonal and intrapersonal skills. Tarrasch (Citation2017) also associates mindfulness with self-regulation, as the findings indicate that mindfulness aids in decreasing impulsivity and generates a positive influence across the school. Moreover, Kiken and Shook (Citation2011) state that mindfulness increases optimism and positive judgments.

A sustainable workforce

According to Nixon (Citation2019), mindfulness is “the quintessential” skill needed for the twenty-first century as it empowers our cognitive abilities (problem-solving, enhanced attention) and our emotions (greater empathy and compassion), thus completing the requirements for a thriving business. Hence, Nixon recommends the inclusion of mindfulness as a common curriculum and encourages policymakers to invest in educating and training the general society in mindfulness (Nixon, Citation2019).

The benefits of mindfulness for tertiary educators and students

According to Gouda et al. (Citation2016), mindfulness could provide students with a positive school experience as it supports their adolescent development and enhances their resilience to stress. In contrast, the effects of mindfulness on educators present a two-way fold, namely, a substantial improvement in one's general wellbeing as well as positively contributing to class interactions and attitude. Tarrasch (Citation2017) states that schools present the ideal setting to practice mindfulness and believes that with proper collaboration, mindfulness programmes can be developed to suit the students’ needs and the school's setting.

Challenges of integrating mindfulness in schools

To successfully integrate mindfulness in schools, one must first answer the questions of when, where and how (Lynn, Citation2010). Moreover, demonstrating the intended principles of mindfulness demands adequately trained personnel who have cultivated a personal transformation in their demeanour, practices, and beliefs (Jean-Baptiste, Citation2014). Such a transformation requires time and commitment, thus, adding more pressure as educators are already struggling with time constraints. According to Weare and Bethune (Citation2020), time restriction is a high-rank factor hindering the integration of mindfulness in schools. Moreover, one needs to ensure that students and educators will be willing to embrace the concept of mindfulness (Lynn, Citation2010).

Mindfulness in organisations

With studies promoting mindfulness as a tool for improving personal achievement and reducing burnout (Hülsheger, Citation2015; Kersemaekers et al., Citation2018), various mindfulness programmes are being introduced into business organisations (Kersemaekers et al., Citation2018). However, authors warn about the misuse of mindfulness in organisations (Endrissat et al., Citation2015; Karjalainen et al., Citation2021). This misconduct includes (a) secluding mindfulness from its original roots and moulding it to fit the business (Vu & Gill, Citation2018), (b) using mindfulness as a “humanistic” front to gain control over employees’ mental and physical entities (Purser, Citation2018; Walsh, Citation2018), and using mindfulness to subtly pressurise employees to be more self-sufficient, indirectly leading them to a more demanding workload (Purser, Citation2018).

Islam et al. (Citation2022) call for an unbiased study as, currently, mindfulness is either praised for its benefits or criticised for its malpractices.

Mindfulness in the salon

To relate the applicability of mindfulness within the salon, one needs to understand the role of a beauty therapist. The professional therapist is expected to evaluate the client's lifestyle, nutrition, habits, physical and mental health by using visual, manual, and verbal assessment techniques during treatment (McKenzie et al., Citation2018). In addition, the therapist's job involves selling products and taking care of clients. Both aspects are essential for the salon's survival. Nevertheless, if clients do not feel their emotional needs are met, they may not want to return to the salon, as argued by Sharma and Black (Citation2001). With this consideration, mindfulness in the salon can have various applications, as discussed in the subsequent sections.

A mindful approach

According to Walker (Citation2013), statistics indicate that 50% of twenty-first-century customers pay for the “feel good” factor as well as the service. The author states that customers choose the overall experience as the key differentiator between one company and another. This factor has been amplified further due to COVID-19 since customers have become increasingly aware of one's wellbeing, thus, driving the wellness sector towards a shift as beauty regiments are undergoing changes placing greater emphasises on self-care to lessen the effects of anxiety (Baird, Citation2020; Rančić Demir et al., Citation2022). Therefore, this indicates that besides the therapist's trade skills, one must have a skill set that allows them to show a compassionate and empathetic attitude towards their clients. The act of showing such socially expected emotions while engaging in service-related interactions was defined as emotional labour by Ashforth and Humphrey (Citation1993, as cited in Yang & Chen, Citation2021).

Mindfulness for the beauty therapist's self-care

Thich Nhat Hanh (Citation2014) says, “Once we love and take care of ourselves, we can be much more helpful to others.” (p. 104).

Besides dealing with one's stressors, beauty therapists often take on their clients’ stressors. Hanson (Citation2019) argues that clients often disclose their stressors in the salon and expect to be listened to. However, the author warns that while empathetic listening is therapeutic for the client, it could cause emotional labour for the service provider. Additionally, the study of Frost et al. (Citation2023) points out that besides managing clients emotionally burdensome narratives, other emotional demands must be considered. These include displaying the “appropriate” emotions despite one’s lack of energy or feelings of distress as well as having to negotiate with clients to ensure they fully understand the importance of respecting and observing established sexual boundaries. Yang and Chen's (Citation2021) comprehensive review of emotional labour also acknowledges the negative impact emotional labour can have on the employee. However, it also discusses studies (Hülsheger & Schewe, Citation2011; Wang et al., Citation2011) whose findings show that emotional labour enhances job satisfaction and one's performance with no repercussions to one's wellbeing.

Nonetheless, in beauty therapy, one must keep in mind that most beauty treatments have an element of touch therapy. According to Larkin (Citation2011), touch therapy is a mutual experience likely to affect the receiver as much as the giver. Andersson et al. (Citation2007) highlight how being in the present moment can aid therapists render the treatment more effective while maintaining control over one's energy and inner balance. Furthermore, coping strategies such as mindfulness, positive thinking, self-awareness and setting boundaries were also found to aid spa therapists’ work performance (Frost et al., Citation2023).

Merging mindful practices with beauty treatments

In recent years, beauty salons across the globe have been merging beauty treatments with mindfulness practices. For instance, a facial treatment would begin with a short mindfulness meditation, which would also include mindful breathing and finish with a guided visualisation (McGroarty, Citation2019). According to Cinti (Citation2021), this development has been awakened further as the challenges posed by COVID-19 provide spas the opportunity to renew their offers in response to the crisis by providing a sense of wellbeing. Such merged treatments are not yet widespread in Malta, meaning that integrating mindfulness training within the Maltese vocational beauty therapy curriculum could pave the way for new and innovative beauty treatments, potentially boosting students’ employability, and success rate.

According to Rančić Demir et al. (Citation2022), the customer’s main motive for visiting a spa is for relaxation purposes, followed by physical and mental activities, healing and medication. The authors also state that customers are ready to embrace new and alternative treatments and urgently recommend spas to adapt to this demand.

The mindful meditation sessions

The mindful meditation sessions used for the purpose of this study were inspired from a range of mindfulness literature and the established MBSR programme by Jon Kabat-Zinn (Citation1990). As illustrated in and , the sessions targeted wellbeing through heightened self-awareness—both physical sensations (outer self) and emotions (inner self), fostering holistic awareness. briefly outlines the relevance of the six chosen sessions to this study.

Figure 2. Illustrates how each mindful meditation session leads the individual to transition into a deeper meditative state.

Table 1. The chosen mindfulness meditation sessions.

The role of visualisation in mindfulness meditation

Visualisation cultivates the mind, enhances attentiveness, and provides harmony as the brain produces images from our senses (Lauren, Citation2017; Smith, Citation2018). In turn, visualisation can help reduce stress, improve cognitive function, increase one's healing ability and attain a higher state of consciousness (Lauren, Citation2017; Smith, Citation2018). However, it is important that the person guiding the session must use a soft and clear voice, as the live voice can be relaxing and therapeutic (Payne & Donaghy, Citation2010).

The mindful ambience

The mindful ambience should offer a sense of positivity and tranquillity (Brookes, Citation2014). According to Banfalvi (Citation2014), music heals the mind and the heart, relieves stress and uplifts one's spirit. Hence soft background music is recommended. A cluttered room is not ideal, as this can be distracting (Salzburg, Citation2017). Lighting candles around the room can give a sense of peace and happiness (Banfalvi, Citation2014). Moreover, diffusing essential oils in the air increase awareness, focus and concentration and helps create a holistic ambience (Godfrey, Citation2018).

Aromatherapy

Aromatherapy uses essential oils extracted from leaves, flowers, seeds, fruits, resins, and roots (Pitman, Citation2019), each with unique chemical compositions (Ryman, Citation2002) that provide benefits such as boosting the immune system and relieving stress (Pitman, Citation2019). Linalool is a common chemical constituent found in many essential oils and is responsible for reducing stress (Caputo et al., Citation2018). Inhalation is the fastest way for essential oils to enter the bloodstream (Tucker, Citation2015), with oil molecules absorbed by the mucous lining of the nasal cavities and detected by cilia receptors. Neural signals travel through the olfactory nerve to the limbic system, which is responsible for emotions and memory, and that is why smells can trigger different memories and emotions (Godfrey, Citation2018; Gould, Citation2003; Pitman, Citation2019; Tucker, Citation2015).

The aromatherapy blends

The variety of synergistic blends one can create with different essential oils is endless. highlights the therapeutic properties of each essential oil, thus relating them to the purpose of this study.

Table 2. The chosen aromatherapy oils.

Combining mindfulness meditation with aromatherapy

According to Godfrey (Citation2018), essential oils are excellent companions to meditation. Their overarching benefits aid in reducing stress, thus promoting a sense of wellbeing. Unfortunately, literature in this combined field is limited. However, the findings of the available studies that combined the two practices state that participants experienced lower stress and anxiety levels (Redstone, Citation2015; Soto-Vásquez & Alvarado-García, Citation2017; Syafitri et al., Citation2019). Syafitri et al. (Citation2019) explain that whilst meditation encourages the brain to increase the production of serotonin and endorphin hormones, the aromatic chemicals linalool and linalyl help increase relaxation and improve one's mood.

Methods

This study aims to understand if integrating mindfulness or aromatherapy-enhanced mindfulness within VET can support educators’ and students’ general wellbeing and its potential applicability and impact within the beauty industry. Therefore, this research seeks to answer the following questions:

How can integrating mindfulness or aromatherapy-enhanced mindfulness into a vocational educational curriculum aid educators’ and beauty students’ stress management, and what influence can these practices have on their personal and professional lives?

What potential applicability does mindfulness have in the beauty industry, and what impact does it have on business effectiveness?

Research method

A qualitative narrative approach was chosen for this study. As Webster and Mertova (Citation2007) state, narrative inquiry “provides the researcher with a rich framework through which they can investigate the ways humans experience the world depicted through their stories” (p.1). Narrative research allows the exploration and understanding of experiences where narrative phenomena and methodology are intertwined (Clandinin, Citation2016). Narrative inquiry and grounded theory have similarities. However, the narrative approach is more relevant as it focuses on temporality, place, and sociality, thus allowing the researcher to be part of the experience (Riessman, Citation2008). Moreover, narrative inquiry provides richer detail than grounded theory, where experience is broken down into coded segments (Riessman, Citation2008).

Narrative inquiry

To truly understand the lived experiences of people, the narrative researcher must become part of the phenomenon being studied, otherwise known as “entering in the midst” (Clandinin, Citation2016, p. 43). This allows the researcher and participant to share and unfold experiences, create new ones, and draw meaning and understanding out of all that emerges (Clandinin, Citation2016; Riessman, Citation2008). As the participants tell their stories, the researcher views the study from the participant's perspective, thus aiding the researcher in understanding, noting, and observing the individual's actions, emotions, and behaviour (Kramp, Citation2003).

Researcher's role

In narrative inquiry, the researcher is the primary instrument for data collection (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018). Therefore, one must be willing to enter the “unknown world” (Riessman, Citation2008) and learn to listen emotionally and attentively. Creswell (Citation2012) reminds us that good communication techniques actively encourages the collection of valuable data. Furthermore, a collaborative rapport between the participant and the researcher is essential. New meaning and understanding can emerge if the researcher executes their role well.

Reflexivity

Narrative inquiry and reflexivity cannot be separated. This is because the reflexive researcher seeks not only to report stories but is involved in an active process of co-constructing meaning and understanding based on his/her experiences, followed by the curiosity to discover how such interpretations developed (Etherington, Citation2017). The reflexivity process also involves the discourse between participant and researcher, which enhances the quality of work by providing valuable information that can serve as an agent of change.

Research process

The rigorous and labour-intensive planning of this research resulted in creating a research process consisting of the following six stages. (Stages one to four did not apply to salon owners).

Stage 1: Pre-session meeting was held to explain the inquiry process to participants. An aromatherapy consultation was also performed.

Stage 2: Six one-to-one mindful meditation sessions were conducted with educators and students. Due to Covid restrictions, the sessions, the interview and the focus group with students were done online using Microsoft Teams. In contrast, the sessions, interview and focus group with educators occurred in person. A four-part mindful journal was given to the participant. Participants had no time limit to fill in the journal. However, they were instructed to fill in the first three parts before the sessions, whilst the fourth was completed after the session. The strategic plan of the sessions can be seen in and . Throughout each session, the participants’ demeanour was observed, and field notes were taken.

Stage 3: A forty-five-minute in-depth individual interview with each three educators and three students was performed using semi-structured open questions as suggested by Riessman (Citation2008).

Stage 4: Two focus groups, each approximately an hour long, were conducted. One with all three participating educators and another with all three participating students.

Stage 5: A one-to-one in-depth interview was held with two salon owners. Each interview was approximately an hour long.

Stage 6: Finally, the researcher worked on developing the narrative analysis and the analysis of narrative and complete the study.

Research instruments

This study used various instruments to collect primary data: observation, participants’ journals, audio recordings, individual interviews, and focus groups, which allowed participants to express themselves freely (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018).

Sample population

Convenience and purposive sampling were used to select the sample population. Such a sampling technique relies on the researchers’ judgment when choosing the participants (Showkat & Parveen, Citation2017). Since this research is specific to post-secondary vocational colleges located in the small island state of Malta, three local vocational educators and three local beauty therapy students were chosen for this study. Furthermore, the study included two local beauty salon owners. The below provides the participants’ demographical information.

Table 3. Provides the demographical information of each participant.

For the participants to relate better to the benefits of mindfulness meditation and aromatherapy, the chosen participants needed to have a background in health care or beauty therapy. Moreover, salon owners were required to have a minimum of three years of experience running the business and preferably have or had at least one employee.

Process of analysis

The data was analysed through a rigorous and lengthy process that underlines the study's trustworthiness and validity. The process involved creating and inputting transcripts into the MAXQDA software to assist the analysis. Once the sessions were done, audio recordings were listened to several times and transcripts, journals and field notes were read and re-read, eventually elucidating the participants’ narrative. Participants were asked to verify and endorse the content. All participants endorsed their narratives, while one participant pointed out a few minor changes, which were integrated accordingly. The analysis process was a reflexive exercise that explored emotions, feelings, and social conditions. The reflexive journal and collaborative communication helped to maintain the researchers’ focus on identifying potential outcomes related to the research question (Clandinin, Citation2016). In this study, both the analysis of narrative and narrative analysis (Polkinghorne, Citation1995) were developed. However, only the analysis of narrative is presented in this article. As is typically seen in such presentations, whole segments from the individual transcripts were elicited to illustrate various themes. A thematic narrative analysis approach was chosen to examine emergent themes and identify common patterns found across the narratives. Transcripts and narratives were re-read in search for resonances, divergences, and liminalities to emerge. Themes and sub-themes were merged, leaving a total of 14 common themes. MAXQDA software was used to facilitate the process. Following the analysis, the outcome was discussed by producing reliable arguments that are supported by literature and the participants’ experiences.

Ethical considerations

Participants were informed that participation was voluntary. They had the right to withdraw, with no obligation. The participants had the opportunity to make changes to the interim text, and the participants approved the final text. A detailed consultation was conducted before the study to abide by health and safety regulations and ensure that the participants were not contraindicated to any essential oils used.

No business was harmed, no personal protective equipment was required, and no animals were involved in this study.

Confidentiality

As stated by Clandinin (Citation2016), confidentiality and anonymity are essential, especially because narrative inquiry may reveal some sensitive issues. Therefore, no identifying factors related to the participants or salons were mentioned. Participants signed a consent form allowing audio recording of the sessions.

Validity and trustworthiness

In narrative inquiry, the way a researcher conveys a story may vary (Clandinin, Citation2016). Therefore, to ensure validity and trustworthiness.

This study was mapped with peer-reviewed literature.

The discussion section is supported with whole excerpts taken from the transcripts.

A pragmatic approach was taken by including divergences in the emerging narratives contradicting the main discussed themes.

Interviews and focus groups were audio recorded to ensure interpretative validity for all six mindful meditation sessions.

As suggested by Riessman (Citation2008), a trusted person was appointed to go over the created themes providing a co-analysis.

Results through analysis of narrative

below depict the participants’ narratives and identify the emerging themes.

Table 4. Educators’ narratives.

Table 5. Beauty students’ narratives.

Table 6. Salon owners’ narratives.

Discussion

During the analysis, 14 themes emerged from the participants’ narratives. The narratives of educators, beauty students and salon owners were compared to identify resonances, differences, and liminalities. Before discussing the findings, the below helps the reader re-familiarise with the participants.

Table 7. Participants’ information table.

The themes hereunder answer the research questions as they portray an interrelation showing how mindfulness and aromatherapy enhanced mindfulness aided educators and beauty students to manage their stress better. Consequently, positively affecting their personal and professional life. The themes also identify the various applicability of mindfulness within the beauty salon and its positive contribution to the business.

Theme 1: the effects of aromatherapy enhanced mindfulness

Educators and beauty students felt that the aromatic scents instantly triggered their brains to enter a relaxed mindset, aiding their wellbeing. “Essential oils positively contribute to the session. I felt more relaxed.” (P4).

Moreover, participating salon owners also like to combine aromatherapy-enhanced mindfulness with their beauty treatments, as they believe it helps relax the clients and treats them holistically.

This outcome links to Pitman's (Citation2019) claims that aromatherapy helps the body recover quickly and aligns with the relaxing effects of the chemical constituent Linalool (Caputo et al., Citation2018).

Theme 2: the importance of ambience

“The music, the [tone of] voice, the positive energy and all affected me.” (P1).

The above correlates with the literature stating that mindfulness should be practised in a peaceful environment (Brookes, Citation2014). Additionally, literature mentions that the music and the right tone of voice can have a therapeutic and relaxing effect (Banfalvi, Citation2014; Payne & Donaghy, Citation2010).

In contrast, since beauty students had online sessions, they highlighted the need to practice mindfulness away from distractions and clutter. Thus, it is consistent with the literature stating that clutter takes away from the overall experience (Salzburg, Citation2017).

Theme 3: achieving self-awareness

The narratives indicate that educators and beauty students successfully enhanced their self-awareness. It was observed that self-awareness was a process that developed gradually throughout the six sessions. Participant 6 states, “ … by the sixth session, I was surprised with how much I discovered about myself.”

Through enhancing self-awareness, participants became aware of their emotional, physical and mental state. Consequently, they grew more conscious and compassionate towards the people around them and their surroundings. This matches the literature, stating that mindfulness allows for self-awareness and, in turn, enables one to better understand others and their surroundings (Godfrey, Citation2018; Shapiro et al., Citation2016).

Theme 4: achieving wellbeing

All participants claimed that the sessions helped improve their wellbeing and noted a feeling of ease and relaxation, thereby decreasing stress. This resonating outcome is well associated with mindfulness practices (Sapthiang et al., Citation2019; Shapiro et al., Citation2016).

Besides the above, participants experienced other unique factors. For instance, participant 3 felt an energy that holistically improved her state of being. The literature explains that mindfulness teaches the individual how to direct one's healing intention, generating soothing energy (Fulder, Citation2019).

These findings further support recognising mindfulness as a tool to aid wellbeing (Whieldon, Citation2016).

Theme 5: achieving a deeper meditative state

“Once we started the meditation sessions, I started to reflect a lot on my life” (P6). The profound reflections, the vivid visualisations and the metaphorical presence described in the participants’ narratives indicate that although each to a varying degree, all participants experienced a deeper meditative state. In turn, participants enhanced their focus and developed a greater sense of gratitude. In the literature, Biswas-Diener and Teeny (Citation2021) explain that mindfulness allows for a state of higher consciousness since the practice involves the awareness of one's thoughts, allowing for deep reflection and empathy.

Theme 6: mindfulness enhancing our personalities

As previously discussed, the participants’ enhanced sense of self-awareness improved their wellbeing, enabling them to relate better with others. “My eyes are open to other people's perceptions. […] this journey makes you look it your character from a different angle.” (P1)

The participants’ narrative indicates that all experienced characteristically changes such as attaining self-control, enhanced compassion, forgiveness, consideration for others and a positive mindset.

The findings correspond with the literature stating that the prime intention of mindfulness practices is to foster positivity, generosity, compassion, and mental wellbeing, amongst other characteristics (Shapiro et al., Citation2016).

Theme 7: mindfulness enhancing the professional realm

Educators believe this mindfulness experience will help them relate better with their students, thus enhancing their profession. Participant 2 states, “a positive mood helps me see my class in a better light”. This aligns with Mbuva's (Citation2016) study, stating that educators’ wellbeing translates into their delivery and students’ learning.

Beauty students also related mindfulness with their professional growth as it helped improve their focus, enhance their approach towards clients and instigated the idea of combining mindfulness in the salon, thus distinguishing themselves from other therapists.

As Nixon (Citation2019) discussed, mindfulness enhances one's mental, physical, and emotional capacities essential for a successful workforce.

Theme 8: having an embodiment of mindfulness

“ … as a person, I practice mindfulness in everything I do.” (P3)

The above correlates with studies stating that mindfulness becomes part of everyday life (Shapiro, Citation2009). The participants’ narratives discuss transformational changes in one's actions, demeanour, and beliefs. This links to the cultivation of mindfulness, as described by Jean-Baptiste (Citation2014). However, it was noted that some factors might hinder one's process of embodiment. For participant 2, time restrictions were a major issue, and thus, could not implement mindfulness in class. This issue features in the study of Weare and Bethune (Citation2020).

Theme 9: mindfulness within the MCAST curriculum

All participants firmly support integrating mindfulness into the curriculum, especially in an institution that offers courses dealing with community services.

“I believe that mindfulness should be part of the curriculum. As it benefits the student and the service user.” (P2)

The above excerpt relates to the literature stating that mindfulness directs the individual towards the path leading to personal wellbeing that lends itself to having a better community (Whieldon, Citation2016).

These findings further support other professional institutions that have included mindfulness to promote wellbeing (Greenberg & Harris, Citation2012; Whieldon, Citation2016).

Theme 10: educators need mindfulness training

Besides reducing educators’ stress, mindfulness training can help educators build meaningful relationships with their students as they take a mindful approach to their lesson delivery.

“I learned to listen more to the students and understand where their challenging behaviour is coming from. We quickly label students as challenging, but things may improve if you reach out to the student.” (P3)

This correlates with the findings of Gouda et al. (Citation2016), as the authors found mindfulness to aid the educators’ interactions and attitudes in class.

Theme 11: work as a beauty therapist

Salon owners agree that besides having relevant qualifications, the individual must have good intrapersonal skills and emotional intelligence. This aligns with the description provided by McKenzie et al. (Citation2018). Participants explain that in the salon, therapists are expected to put their worries aside and listen emphatically to the client. This correlates with the findings of Hanson (Citation2019) and Yang and Chen (Citation2021), as the authors acknowledge that employees providing service-related interactions are subjected to emotional labour. Moreover, participant 8 states, “ … in our line of work. Our energy is transmitted to the client. If we are tense, they can feel us.”

These findings compare with Larkin's (Citation2011) study, claiming that touch therapy is an experience that reciprocally affects the receiver and the giver.

Theme 12: the applicability of mindfulness in the salon

In their narratives, salon owners illustrate the versatile applicability of mindfulness within the salon. This includes (1) Upgrading regular treatments by combining mindfulness practices such as breathing techniques, meditation, and visualisation. These correlate with the techniques used in other salons across the globe (McGroarty, Citation2019). Moreover, this integration is crucial since it gives the client a sense of belonging and ultimately, “ … if clients feel important, they will keep coming back.” (P8). This links to the statistics, stating that customers seek that “feel good” factor (Walker, Citation2013). (2) Mindfulness for the therapist's self-care. Before opening the salon, both salon owners claim to practice mindfulness as mental preparation for the day ahead. This supports mindfulness as a tool to counteract stress and improve productivity (Kersemaekers et al., Citation2018). (3) Mindfulness beyond the salon as both salon owners teach their clients how to use mindfulness at home.

“ … I encourage the clients to take a deep breath in and smell the products. I tell them to focus on this moment and be mindful of these things at home as well.” (P7)

The above shows how mindfulness seeps into everything we do (Shapiro, Citation2009).

Theme 13: hindrance for mindfulness implementation

The narratives describe issues that might hinder the integration of mindfulness in the curriculum and the salon. Specifically, scepticism, the lack of knowledge and awareness of mindfulness, and the lack of time to implement and commit to mindfulness practice are common issues in both aspects. These issues match the list of factors hindering the integration of mindfulness in schools, as stated by Weare and Bethune (Citation2020). Moreover, participant 8 states, “one could be trained in mindfulness but still not be mindful.” This statement compares to the transformational changes discussed by Jean-Baptiste (Citation2014).

Theme 14: lasting benefits of mindfulness

“ … The impact the sessions had on me two years ago is still very strong in my mind and heart … it was the start of a journey to find peace and cut the chains of negativity” (P1)

The above excerpt is a typical outcome of mindfulness and is pointed out by Shapiro et al. (Citation2016), as the authors state that mindfulness promotes physical, mental, and emotional wellbeing. The participants’ narratives give an encouraging testimonial and demonstrate how one carries within them the mindful experience and how such an impact can grow stronger in one's life.

Discussion of emerged models

The discussed themes are interrelated as they sustain each other. This is evident from the five models that emerged from the above findings.

Model 1: creating a blissful ambience

The findings show that one's surroundings highly influence one's mindfulness experience. shows how the individual's auditory, olfactory, and visual senses can be stimulated to attune to the energy level required for mindfulness meditation. A blissful ambience includes guiding the session with a gentle, firm voice, relaxing background music, natural elements such as plants and diffusing calming aromatic scents.

Figure 3. Model 1 shows how one can create a blissful ambience ideal for practicing mindfulness meditation.

This serene ambience can be viewed as a “stepping stone” that leads the individual to achieve a deep meditative state.

Model 2: achieving a deeper meditative state

The findings show that a deeper meditative state allows for profound thoughts, enhanced self- awareness, inner peace, and several other benefits. provides a structured framework indicating a set of requirements, each sustaining one another, intending to achieve a deeper meditative state. These include,

Practising mindfulness in a blissful ambience. (See )

Practising mindfulness regularly to gradually increase focus, thus potentially leading to achieving a deeper meditative state.

Include visualisation as the experience is potentially more powerful, thus contributing to achieving a deeper meditative state.

Model 3: self-awareness holds the key to our wellbeing

The findings indicate that self-awareness holds the key to our wellbeing. illustrates the positive cycle generated once self-awareness is enhanced, directly influencing our sense of wellbeing, consequently lowering stress and anxiety. Such an outcome improves our academic and work performance. Furthermore, our personality is enhanced, positively affecting our approach to personal, professional, and social interactions.

Model 4: a support framework for mindfulness practice

The characteristics that emerged from this study align with the top ten skills needed to successfully deal with the requirements of this twenty-first century. Mindfulness can be viewed as the bridge connecting personal, educational, and professional development. illustrates how we can make our mindfulness practice more meaningful and effective, thus paving the way to achieving holistic development and embodiment of mindfulness to ultimately keep reaping its benefits.

Model 5: mindfulness from educational field to organisation

The findings show that integrating mindfulness in vocational education can potentially lead to a thriving business. As seen in model 5 (), this can be achieved by firstly integrating mindfulness within the education. This involves (a) providing mindfulness training to educators and (b) including mindfulness as part of the student's curriculum. This combination can potentially lead to enhancing the industry as follows.

Beauty students can project their mindfulness education and training to the industry.

The applicability of mindfulness to the business can aid the employee's personal and professional development, the client's wellbeing, and the business's reputation.

The above contributes to generating awareness of mindfulness in the broader community.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study gives contribution to four important sectors, namely,

Education: The findings show that mindfulness and aromatherapy enhanced wellbeing for educators and beauty students, leading to positive changes in personality and interpersonal relationships. Furthermore, mindfulness training for educators enhanced productivity and lesson delivery, while mindfulness in the beauty therapy curriculum can potentially improve students’ school experience, academic achievements, and employability.

Industry: Integrating mindfulness in vocational education will produce mindful beauty therapy students who will be able to project their knowledge and training of mindfulness within the industry. The findings show that the applicability of mindfulness within the beauty industry has various roles that can positively affect the quality of service provided, the client's wellbeing, and the therapist's wellbeing. Collectively these three aspects contribute to a thriving business.

Society: Mindfulness can be a valuable asset, potentially enhancing one's interpersonal skills and emotional intelligence. The 4th industrial revolution highlighted the importance of attaining such qualities and skills as they are thought to be the key to a brighter future (European Commission, Citation2016). This is highly relevant in the context of the beauty business, as the job includes a significant amount of human interaction. Therefore, our society can greatly benefit from individuals trained to provide a service with a mindful approach.

International: This study fills a research gap on aromatherapy-enhanced mindfulness and can be an agent of change in enhancing education, the beauty industry, and other sectors involving human interaction, improving the local economy.

A limitation of this study was due to Covid-19. To respect health and safety regulations this study was delayed by a few months. This delay coincided with the Institute’s summer recess. Consequently, it was not possible to observe the impact of mindful meditation and the interaction quality between educators and their students. Additionally, the study faced limitations as the mindful meditation sessions with ICS students were conducted online. This hindered my personal connection with the participants and deprived them of the same harmonious environment provided for the lecturers. Hence, the final outcome could have emerged differently.

Further studies can explore developing a mindfulness unit that can be integrated into various course curricula and having timetables that permit educators to attend mindfulness training and allow them enough flexibility to cultivate a mindfulness approach within the classroom. Close communication with the industry is essential throughout the integration process to provide correct information and education about mindfulness and how it can benefit the business. Vocational education is the bridge between education and the industry, and mindfulness can be the right tool for vocational colleges to enhance their commitment to providing the best possible learning environment and produce a professional workforce that contributes positively to society.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nadia Cauchi

Ms Nadia Cauchi is a Senior Lecturer at the Malta College of Arts, Science and Technology (MCAST), where she brings her expertise in the beauty and holistic therapy field. Nadia is currently a third-year doctorate student pursuing the MCAST Professional Research Doctorate on the Competitive Behaviour of Small Organizations (DRes). Her research interests are centred on using holistic therapies, such as mindfulness, to help students and lecturers manage their daily stressors and improve their personal and professional lives. Nadia aims to create a positive impact in the beauty industry by sharing her findings and promoting the use of mindfulness meditation.

Rose Falzon

Dr Rose Falzon’s main Masters and Doctoral academic qualifications are in education, psychotherapy, counselling, practitioner supervision and mentoring, and Qualitative Research in the Humanistic Fields. Dr Falzon’s designation at MCAST is as a Senior Lecturer and Coordinator of the Masters in Research Methods and Supervisor in the Professional Doctorate in Research at MCAST Applied Research and Innovation. Dr Falzon held several workshops and presentations concerning therapy and supervision in conferences both locally and abroad. Apart from her two doctoral thesis, she published diverse articles in MCAST Journal of Applied Research & Practice, European Association for Counselling Online Publications, and the European Journal for Qualitative Research in Psychotherapy. [email protected].

References

- Agyapong, B., Obuobi-Donkor, G., Burback, L., & Wei, Y. (2022). Stress, burnout, anxiety and depression among teachers: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710706

- Ali, B., Al-Wabel, N. A., Shams, S., Ahamad, A., Khan, S. A., & Anwar, F. (2015). Essential oils used in aromatherapy: A systemic review. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine, 5(8), 601–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apjtb.2015.05.007

- Andersson, K., Wändell, P., & Törnkvist, L. (2007). Working with tactile massage -A grounded theory about the energy controlling system. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 13(4), 258–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2007.03.006

- Ashforth, Blake E, & Humphrey, Ronald H. (1993). Emotional Labor in Service Roles: The Influence of Identity. Academy of management review, 18(1), 88–115. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1993.3997508

- Aydogan, I., Dogan, A. A., & Bayram, N. (2009). Burnout among Turkish high school teachers working in Turkey and abroad: A comparative study. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 7, 1249–1268. https://doi.org/10.25115/ejrep.v7i19.1354

- Baird, R. (2020, June). Impact of covid-19 on beauty & wellness. Baird investment advisor co. Ltdhttp://content.rwbaird.com/RWB/sectors/PDF/consumer/Impact-of-Covid-19-on-Beauty-Wellness.pdf.

- Bamber, M. D., & Schneider, J. K. (2016). Mindfulness-based meditation to decrease stress and anxiety in college students: A narrative synthesis of the research. Educational Research Review, 18, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.12.004

- Banfalvi, E. (2014). Meditation defining your space. Balboa Press.

- Bays, J. C. (2011). How to train a wild elephant: And other adventures in mindfulness. Shambhala Publications.

- Biswas-Diener, R., & Teeny, J. (2021). States of consciousness. In R. Biswas-Diener, & E. Diener (Eds.), Noba textbook series: Psychology (pp. 321–336). DEF publishers. http://noba.to/xj2cbhek.

- Brannon, L., & Feist, J. (2007). Health psychology: An introduction to behaviour and health (6th ed). Thomson Wadsworth.

- Bredlöv, E. (2022). Becoming an emotional worker and student: Exploring skin and spa therapy education and training. Studies in Continuing Education, 44(3), 347–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2020.1865300

- Brookes, S. (2014). Meditation made easy. CICO Books.

- Brown, J. (2018, August 3). Psychology: What you're getting wrong about mindfulness. BBC Worklife. http://www.bbc.com/capital/story/20180802-why-everything-you-thought-about-mindfulness-may-not-be-true.

- Burk, D. S. (2014). Idiot's guides to mindfulness. Penguin Group Inc.

- Caputo, L., Reguilon, M. D., Mińarro, J., De Feo, V., & Rodriguez-Arias, M. (2018). Lavandula Angustifolia essential oil and linalool counteract social aversion induced by social defeat. Molecules, 23(10), 2694. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23102694

- Cassar, S., & Formosa, A. M. (2011). The new academic disease: A study on stress among secondary school teachers [Bachelor's thesis, University of Malta]. OAR@UM. https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar//handle/123456789/3865.

- Chia, M. (2002). Taoist ways to transform stress into vitality: The inner smile, six healing sounds. Universal Tao Publications.

- Cinti, M. G. (2021). Turismo termale in italia: Evoluzione, impatti e prospettive di rilancio. Documenti Geografici, 1, 65–88. https://doi.org/10.19246/DOCUGEO2281-7549/202101_04

- Clandinin, D. J. (2016). Engaging in narrative inquiry. Routledge.

- Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed.). Pearson.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, D. J. (2018). Research design qualitative, quantitative & mixed methods (5th ed). Sage.

- Dias, P., Luís, P., Olívia, R. P., & João, S. M. (2017). Aromatherapy in the control of stress and anxiety. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 6, 248. https://doi.org/10.4172/2327-5162.1000248

- Dobetsberger, C., & Buchbauer, G. (2011). Actions of essential oils on the central nervous system: An update review. Flavour and Fragrance Journal, 26, 300–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/ffj.2045

- Docksai, R. (2013). A mindful approach to learning. The Futurist, 47, 8–10. https://ejournals.um.edu.mt/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/magazines/mindful-approach-learning/docview/1425865248/se-2.

- Dodge, R., Daly, A., Huyton, J., & Sanders, L. (2012). The challenge of defining wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(3), 222–235. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v2i3.4

- Dreeben, S. J., Mamberg, M. H., & Salmon, P. (2013). The MBSR body scan in clinical practice. Mindfulness, 4, 394–401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0212-z

- Endrissat, N., Islam, G., & Noppeney, C. (2015). Enchanting work: New spirits of service work in an organic supermarket. Organization Studies, 36(11), 1555–1576. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840615593588

- Etherington, K. (2017). Personal experience and critical reflexivity in counselling and psychotherapy research. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 17(2), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12080

- European Commission. (2016). A new skills agenda for Europe. Working together to strengthen human capital, employability and competitiveness (COM (2016) 381 final).Brussels.

- Farrell, A., Kagan, S. L., & Tisdall, E. K. M. (Eds.). (2016). The SAGE handbook of early childhood research. Sage.

- Filiptsova, O. V., Gazzavi-Rogozina, L. V., Timoshyna, I. A., Naboka, O. I., Dyomina, Y. V., & Ochkur, A. V. (2017). The essential oil of rosemary and its effect on the human image and numerical short-term memory. Egyptian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 4(2), 107–111. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1016j.ejbas.2017.04.002.

- Frost, J., Van Dijk, P., & Ooi, N. (2023). Coping with occupational stress: Exploring women spa therapist’s experiences. International Journal of Spa and Wellness, 6(2), 179–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/24721735.2023.2170017

- Fulder, S. (2019). What's beyond mindfulness? Waking up to this precious life. Watkins.

- Godfrey, H. D. (2018). Essential oils for mindfulness and meditation. Healing Arts Press.

- Gouda, S., Luong, M. T., Schmidt, S., & Bauer, J. (2016). Students and teachers benefit from mindfulness-based stress reduction in a school-embedded pilot study. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 590. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00590

- Gould, F. (2003). Aromatherapy for holistic therapists. Nelson thrones.

- Green, F. (2021). British teachers’ declining job quality: Evidence from the skills and employment survey. Oxford Review of Education, 47(3), 386–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2020.1847719

- Greenberg, M. T., & Harris, A. R. (2012). Nurturing mindfulness in children and youth: Current state of research. Child Development Perspectives, 6(2), 161–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00215.x

- Hanh, T. N. (2014). No mud, no lotus: The art of transforming suffering. Parallax press.

- Hanson, K. (2019). Beauty “therapy”: The emotional labor of commercialised listening in the salon industry. International Journal of Listening, 33(3), 148–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/10904018.2019.1634572

- Hazlett-Stevens, H. (2018). Mindfulness-based stress reduction in a mental health outpatient setting: Benefits beyond symptom reduction. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health, 20(3), 275–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/19349637.2017.1413963

- Hellerstein, D. J. (2011). Heal your brain: How the new neuropsychiatry can help you go from better to well. JHU Press.

- Hölzel, B. K., Carmody, J., Vangel, M., Congleton, C., Yerramsetti, S. M., Gard, T., & Lazar, S. W. (2011). Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 191(1), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.08.006

- Hongratanaworakit, T., & Buchbauer, G. (2004). Evaluation of the harmonising effect of Ylang-ylang oil on humans after inhalation. Planta Medica, 70(07), 632–636. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2004-827186

- Hülsheger, U. R. (2015). Making sure that mindfulness is promoted in organisations in the right way and for the right goals. Industrial and Organisational Psychology, 8(4), 674–679. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2015.98

- Hülsheger, U. R., & Schewe, A. F. (2011). On the costs and benefits of emotional labor: A meta-analysis of three decades of research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(3), 361. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022876

- Hyland, T. (2014). Reconstructing vocational education and training for the 21st century: Mindfulness, craft, and values. Sage Open, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013520610

- Islam, G., Holm, M., & Karjalainen, M. (2022). Sign of the times: Workplace mindfulness as an empty signifier. Organisation, 29, 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508417740643

- Jean-Baptiste, M. (2014). Teachers’ perceptions of mindfulness-based practices in elementary schools [Doctoral dissertation, California State University, Sacramento]. Scholar works. https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/concern/theses/8336h797r.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. Delacourt.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Science and Practice, 10, 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg016

- Karjalainen, M., Islam, G., & Holm, M. (2021). Scientization, instrumentalisation, and commodification of mindfulness in a professional services firm. Organisation, 28, 483–509. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508419883388

- Karunananda, A. S., Goldin, P. R., & Talagala, P. D. (2016). Examining mindfulness in education. International Journal of Modern Education and Computer Science, 8(12), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.5815/ijmecs.2016.12.04

- Kersemaekers, W., Rupprecht, S., Wittmann, M., Tamdjidi, C., Falke, P., Donders, R., & Kohls, N. (2018). A workplace mindfulness intervention may be associated with improved psychological well-being and productivity. A preliminary field study in a company setting. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 195. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00195

- Kiken, L. G., & Shook, N. J. (2011). Looking up: Mindfulness increases positive judgments and reduces negativity bias. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2(4), 425–431. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550610396585

- Kramp, M. K. (2003). Exploring life and experience through narrative inquiry. In K. de Marris, & S. Lapan (Eds.), Foundations for research (pp. 119–138). Routledge.

- Kuyken, W., Weare, K., Ukoumunne, O. C., Vicary, R., Motton, N., Burnett, R., & Huppert, F. (2013). Effectiveness of the mindfulness in schools programme: Non-randomised controlled feasibility study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 203(2), 126–131. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.113.126649

- Larkin, T. (2011). Examining the effects of massage on therapists: How energies are absorbed. International Academy of Massage Inc.

- Lauren, L. (2017). Meditation. Orion Publishing Group Ltd.

- Liu, F., Chen, H., Xu, J., Wen, Y., & Fang, T. (2021). Exploring the relationships between resilience and turnover intention in Chinese high school teachers: Considering the moderating role of job burnout. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6418. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126418

- Lopresti, A. L. (2017). Salvia (Sage): A review of its potential cognitive-enhancing and protective effects. Drugs in R&D, 17(1), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40268-016-0157-5

- Lynn, R. (2010). Mindfulness in social work education. Social Work Education, 29(3), 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470902930351

- Mbuva, J. (2016). Exploring teachers’ self-esteem and its effects on teaching, students’ learning and self-esteem. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 16, 59.

- McCaw, C. T. (2020). Mindfulness’ thick ‘and ‘thin’ - A critical review of the uses of mindfulness in education. Oxford Review of Education, 46(2), 257–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2019.1667759

- McGroarty, B. (2019). Global wellness trends report: Meditation goes plural. https://www.globalwellnesssummit.com/2019-global-wellness-trends/meditation-goes-plural/.

- McKenzie, M., Harreveld, R., & Blayney, W. (2018). Beauty therapy, VET teaching and bio-power: A tale of two training packages. International Journal of Training Research, 16(1), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/14480220.2018.1433614

- Moss, E. E., Hirshberg, M., Flook, L., & Graue, B. (2017). Cultivating reflective teaching practice through mindfulness. In E. Dorman, K. Byrnes, & J. Dalton (Eds.), Impacting teaching and learning: Contemplative teacher education (pp. 29–39). Rowman & Littlefield.

- Nixon, D. (2019). Towards an economy built upon human capacities of heart and mind. The Mindfulness Initiative.

- Obidigbo, G. C. E., & Onyekuru, B. U. (2012). You and your self-concept. Sages Communication.

- OECD. (2017). PISA 2015 results (Volume III): Students’ well-being. PISA, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264273856-en

- Okano, S., Honda, Y., Kodama, T., & Kimura, M. (2019). The effects of frankincense essential oil on stress in rats. Journal of Oleo Science, 68(10), 1003–1009. https://doi.org/10.5650/jos.ess19114

- Pascoe, M. C., Hetrick, S. E., & Parker, A. G. (2020). The impact of stress on students in secondary school and higher education. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2019.1596823

- Payne, R. A., & Donaghy, M. (2010). Payne's handbook of relaxation techniques: A practical handbook for the health care professional (4th ed.). Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier.

- Pitman, V. (2019). Aromatherapy a practical approach (2nd ed.). Lotus Publishing.

- Polkinghorne, D. E. (1995). Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 8(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951839950080103

- Purser, R. E. (2018). Critical perspectives on corporate mindfulness. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 15(2), 105–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2018.1438038

- Rahimi, H., Nakhaei, M., Mehrpooya, N., Hatami, S. M., & Vagharseyyedin, S. A. (2019). The effect of inhaling the aroma of rosemary essential oil on the pre-hospital emergency personnel stress and anxiety: A quasi-experimental study. Modern Care Journal, 16(3), https://doi.org/10.5812/modernc.95082

- Rajpoot, P. L., & Vaishnav, P. (2015). Effect of Trataka on anxiety among adolescents. International Journal of Psychological and Behavioral Sciences, 8, 4004–4007. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1099920

- Rančić Demir, M., Pavlakovič, B., Pozvek, N., & Turnšek, M. (2022). Adapting the wellness offer in Slovenian spas to the new COVID-19 pandemic conditions. International Journal of Spa and Wellness, 5(3), 285–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/24721735.2022.2128589

- Redín, C. I., & Erro-Garcés, A. (2020). Stress in teaching professionals across Europe. International Journal of Educational Research, 103, 101623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101623

- Redstone, L. (2015). Mindfulness meditation and aromatherapy to reduce stress and anxiety. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 29(3), 192–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2015.03.001

- Richmond Foundation. (2022, April 23). Taking care of our youth's mental health. https://www.richmond.org.mt/2022/04/23/taking-care-of-our-youths-mental-health/.

- Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage Publications.

- Ryman, D. (2002). Aromatherapy Bible. Judy Piatkus (publishers) Ltd.

- Sakamoto, R., Minoura, K., Usui, A., Ishizuka, Y., & Kanba, S. (2005). Effectiveness of aroma on work efficiency: Lavender aroma during recesses prevents deterioration of work performance. Chemical Senses, 30(8), 683–691. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bji061

- Salzburg, S. (2017). Real love: The art of mindful connection. Pan Macmillan.

- Sapthiang, S., Van Gordon, W., & Shonin, E. (2019). Mindfulness in schools: A health promotion approach to improving adolescent mental health. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17, 112–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-0001-y

- Schmidt, S. (2004). Mindfulness and healing intention: Concepts, practice, and research evaluation. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine, 10(1), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1089/1075553042245917

- Science Daily. (2010, April 19). Biological link between stress, anxiety and depression identified. ScienceDaily. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/04/100411143348.htm.

- Shapiro, S. (2009). Meditation and positive psychology. In C. R. Synder, & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of positive psychology (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195187243.001.0001

- Shapiro, S. L., Jazaieri, H., & De Sousa, S. (2016). Meditation in positive psychology. In C. R. Synder, S. J. Lopez, L. M. Edwards, & S. C. Marques (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of positive psychology (3rd ed.) (pp. 862–877). Oxford University Press.

- Sharma, H. (2015). Meditation: Process and effects. Journal of Research in Ayurveda, 36(3), 233–237. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-8520.182756

- Sharma, U., & Black, P. (2001). Look good, feel better: Beauty therapy as emotional labour. Sociology, 35(4), 913–931. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038501035004007

- Shonin, E., Van Gordon, W., & Griffiths, M. D. (2014). Loving-kindness and compassion meditation in psychotherapy. Thresholds: Quarterly Journal of the Association for Pastoral and Spiritual Care and Counselling, Spring Issue, 9–12.

- Showkat, N., & Parveen, H. (2017). Non-probability and probability sampling. Media and Communications Study, 1–9. https://www.scirp.org/(S(351jmbntv-nsjt1aadkposzje))/reference/referencespapers.aspx?referenceid=3043744.

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2020). Teacher burnout: Relations between dimensions of burnout, perceived school context, job satisfaction and motivation for teaching. A longitudinal study. Teachers and Teaching, 26(7–8), 602–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2021.1913404

- Smith, D. B. (2018, October 24). Power of the mind 1: The science of visualisation. Science Abbey. https://www.scienceabbey.com/2018/10/24/power-of-the-mind-the-science-of-visualization-1/.

- Soto-Vásquez, M. R., & Alvarado-García, P. A. A. (2017). Aromatherapy with two essential oils from Satureja genre and mindfulness meditation to reduce anxiety in humans. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine, 7(1), 121–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcme.2016.06.003

- Syafitri, E. N., Ratmini, S. A. N. S., & Murdiono, W. R. (2019). Meditation and lavender aromatherapy combinations reducing stress of health students. International Journal of Health Science and Technology, 1(1), 33–38. https://doi.org/10.31101/ijhst.v1i1.942

- Tang, Y. Y., Lu, Q., Feng, H., Tang, R., & Posner, M. I. (2015). Short-term meditation increases blood flow in anterior cingulate cortex and insula. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 212. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00212

- Tarrasch, R. (2017). Mindful schooling: Better attention regulation among elementary school children who practice mindfulness as part of their school policy. Journal of Cognitive Enhancement, 1(2), 84–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41465-017-0024-5

- Taylor, S. E. (2003). Health psychology (5th ed.). Mc Grow Hill.

- Tregenza, V. A. (2008). Looking back to the future: The current relevance of Maria Montessori’ s ideas about the spiritual well-being of young children. The Journal of Student Wellbeing, 2(2), 1–15. doi:10.21913/JSW.v2i2.392

- Tucker, L. (2015). An introductory guide to aromatherapy (2nd ed.). EMS Publishers.

- Van Dam, N. T., Van Vugt, M. K., Vago, D. R., Schmalzl, L., Saron, C. D., Olendzki, A., Meissner, T., Lazar, S. W., Kerr, C. E., Gorchov, J., Fox, K. C. R., Field, B. A., Britton, W. B., Brefczynski-Lewis, J. A., & Meyer, D. E. (2018). Mind the hype: A critical evaluation and prescriptive agenda for research on mindfulness and meditation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(1), 36–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617709589

- Vella, K. (2018, April 29). Survey reveals teachers’ challenges and suggestions. Times of Malta. https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/Survey-reveals-teachers-challenges-and-suggestions.677764.

- Vu, M. C., & Gill, R. (2018). Is there corporate mindfulness? An exploratory study of Buddhist-enacted spiritual leaders’ perspectives and practices. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 15(2), 155–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2017.1410491

- Walker. (2013). Customer 2020: A progress report - More insight for a new decade. Walker Information.

- Walker, T. (2022). Survey: Alarming number of educators may soon leave the profession. NEA Today.

- Walsh, Z. (2018). Mindfulness under neoliberal governmentality: Critiquing the operation of biopower in corporate mindfulness and constructing queer alternatives. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 15(2), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2017.1423239

- Wang, G., Seibert, S. E., & Boles, T. L. (2011). Synthesising what we know and looking ahead: A meta-analytical review of 30 years of emotional labor research. In C. E. J. Härtel, N. M. Ashkanasy, & W. J. Zerbe (Eds.), What have We learned? Ten years On (Research on emotion in organisations, Vol. 7) (pp. 15–43). Emerald Group Publishing Limit. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1746-9791(2011)0000007006

- Warm, J. S., Dember, W. N., & Parasuraman, R. (1991). Effects of olfactory stimulation on performance and stress. The Journal of the Society of Cosmetic Chemists, 42, 199–210.

- Weare, K. (2018). The evidence for mindfulness in schools for children and young people. https://mindfulnessinschools.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Weare-Evidence-Review-Final.pdf.

- Weare, K., & Bethune, A. (2020). Strategy for mindfulness and education. The Mindful Initiative.

- Webster, L., & Mertova, P. (2007). An introduction to using critical event narrative analysis in research on learning and teaching. Routledge.

- Whieldon, A. (2016). Mind clearing: The key to mindfulness mastery. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.