Abstract

This paper explores the development of the ‘problem/solution nexus’ of a cancelled mega urban transport project in Melbourne, Australia. The East-West Link (Eastern Section) was the most recent iteration of a cross-town motorway connection that has been proposed numerous times since the 1960s, most recently in early 2013. After a State parliamentary election in November 2014, in which the opposition party defeated the incumbent, the project contracts were cancelled, amid widespread community discontent. This research employs the concept of ‘problem/solution nexus’ – in which problem and solution are recursively generated and arise in tandem – to explore the historical framing of the problems the project was intended to solve. We perform a discourse analysis of planning documents and government reports, complemented by interviews with several policy-makers and analysts. Our work demonstrates how the problematisation of the project was changed in key documents to make the solution appear more viable, which propelled the project forward and means a likely return in the future.

1. Introduction

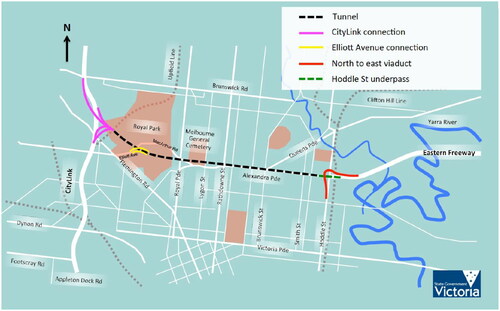

In 2014, the Minister for Planning in the Australian state of Victoria approved a AU$6.8 billion 4.4 km road tunnel project (see ). Soon thereafter in 2015, the project was cancelled by the newly elected State Premier. The East-West Link (Eastern Section) was seemingly a ‘solution’ in search of a problem – and a solution that has, in some form or another, lingered in Melbourne since the 1960s.

Figure 1. Base case designs solution of the East-West Link (Eastern Section), not including ancillary upgrades or the extension to the port. Central Melbourne is at the bottom centre of the map (Department of Transport Citation2013, 89). © State of Victoria, under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In this paper, we explore the notion of a ‘problem/solution nexus’ (Sturup Citation2015) in the case of the East West Link (henceforth EWTFootnote1). Drawing on the governmentality literature, we show how the proposed solution, and the problems it was to solve, recursively generate each other through practices of technical rendition (Li Citation2007). In highlighting how problem and solution align, we identify a set of tropes that were mobilised to build support for the project – the problem of cross-town travel, the (related) problem of freeways that just end, and the problem of value for money. We explore how these stories were elaborated to produce a solution that more adequately addressed the problem, and also to produce understandings of problems that the solution could solve. Identifying these processes gives us insight into the structures of knowledge that most recently gave life to the EWT, and may offer some insight into its re-emergence, when that eventually happens.

2. The project

This paper is about the EWT’s most recent iteration, which met its demise in June 2015 when the recently elected Premier of Victoria finalised its cancellation (Andrews Citation2015). Solutions like the EWT have been proposed numerous times over the past half-century, though. The EWT first appeared during the 1960s during the first wave of comprehensive transportation plans. The 1969 Melbourne Transportation Plan proposed an extensive grid of motorways across metropolitan Melbourne, which included a route corresponding to the EWT project (Metropolitan Transportation Committee Citation1969). The route would traverse established neighbourhoods a few kilometres north of central Melbourne – but on the surface, rather than as a tunnel. Slated for construction in the 1971 Planning Policies for Metropolitan Melbourne, as part of a larger Eastern Freeway route (Gleeson, Curtis, and Low Citation2003), a segment similar to the EWT was scrapped in March 1973 in the face of community opposition (Rundell Citation1985). Construction continued on the segment now known as the Eastern Freeway.Footnote2 In the early 1990s, a short, westward extension to the Eastern Freeway was proposed, and community groups constructed ramparts of household junk in the median of the correspondingFootnote3 cross-town route in protest (Farrant Citation1994). The periodic resurrection of the project makes understanding the mentalities that drive it all the more crucial.

3. Approach and methods

The focus of this paper is the problem/solution nexus in the most recent manifestation of the EWT, between approximately 2003 and 2015. We selected the EWT as a subject because it presented a timely opportunity to explore the problem/solution nexus in an unsuccessful mega urban transport project (MUTP).

Methodologically, the problem/solution nexus of a project is explored by documenting changing practices of technical rendition and problematisation and by tracing the histories of how a problem is understood with respect to its matched solution. We base our approach on Sturup’s (Citation2010, Citation2015) previous inquiries, which explored more broadly the art of government of three successfully-completed MUTPs in Australia. We saw this framing as useful because we wanted to demonstrate that the presence of mentalities of megaprojects were not related to the success, or lack thereof, of megaprojects. The mentalities of government specific to MUTPs include the problem/solution nexus, explored in this paper in more detail, sovereign power structures in decision-making processes, and the sublime of project (Sturup Citation2010, Citation2015).

The sources of data for this research are official planning and project documents where the EWT is included as a component of the plan or as the focus of the document, and we supplement the narrative with periodical articles about the project published between 2003 and 2015. Together, these comprise a representation of the public record about this project. summarises the documents we used to characterise the problematisation of the EWT. Each of these documents was authored by or on behalf of the relevant configuration of the Victorian infrastructure or transport department, which while having different names, was essentially the same ministry. We selected these sources because they comprise the set of documents representing the problematisation of the EWT over the study period, and while other documents may have included reference to the EWT, they did not do so in a way that advances our analysis.

Table 1. Key documents problematising the East-West Tunnel.Footnote3

We also conducted eight semi-structured interviews with actors involved in planning the EWT to supplement the historical narrative produced from documentation. Each of the interviewees had a role in EWT problematisation, either in the production of technical or planning documents, as advisers, or as anti-EWT campaigners. Interviewees and their relationship to the EWT project are listed in . Most respondents opted to remain anonymous in publication.

Table 2. Key informants interviewed in this study.

We note the limited number of interviews with elected representatives. Our focus in this paper is not explicitly on the political dimensions of decision-making, but rather on how the problem and solution underpinning the EWT emerged and sustained the project. Project and planning documentation and the reflections of actors involved in document production provide representation of the logics that co-produce problem and solution. In the earlier stages of this research, we did reach out to state politicians, but had no success in achieving on-the-record comments about the project.

4. The promise of megaprojects

Megaprojects have been the subject of much debate in the literature. They are attractive because they promise social, economic, or environmental transfiguration to the urban and regional areas they are constructed in, but they challenge strategic spatial and transportation planning by substituting these longer term planning practices with infrastructure projects (Dodson Citation2009). They are growing in ‘number, size, complexity, and cost’, with little regard for inter- and intra-generational equity (Ward and Skayannis Citation2019, 27, 48), nor for environmental stewardship (Sturup and Low Citation2019). In this section, we illustrate and problematise some of the transformative promise of MUTPs, making space for our discussion about the co-determination of problem and solution.

The narratives of MUTPs are constructed in ways that extend their problematisation beyond the realm of transport planning. Peters (Citation2010) points to how a bundled package of MUTPs through the centre of Berlin was bound up in the discourses of German reunification, so much so that the central station of Berlin was moved from its former location at Friedrichstraße to a greyfields area near the path of the Berlin Wall to facilitate urban renewal, while also linking the project into reunification discourses. Using a framework developed from actor-network theory, Boholm (Citation2005) explores the troubled Hallandsås railway tunnel in rural southern Sweden. Early construction of the Hallandsås tunnel was rife with problems, including the poisoning of groundwater resources, but was eventually driven forward by discursive reorientation towards a greater environmental good and ideals of European integration, since the project would facilitate rail travel between Gothenburg in Sweden and Copenhagen in Denmark. In each of these examples, the MUTP is saddled with additional, non-transport aims, in which the transport solution addresses numerous, often amorphous, non-transport problems.

Part of the transformative promise of MUTPs is in how they provoke a sense of both fear and sublime, often using metaphor to communicate their large-scale engineering fixes. During the construction of Melbourne’s CityLink tollways, advertisements for the project used the biological metaphor of a triple heart bypass to drive public support, complete with imagery of the central city as a beating heart surrounded by arteries/arterials (Low, Gleeson, and Rush Citation2003). Without the project, Melbourne as bodily metaphor would suffer, which communicated a sense of urgency and necessity to the CityLink MUTP. Using the post-earthquake reconstruction of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge in California, Trapenberg Frick (Citation2008) shows how the ‘technological sublime’ fuels creative engineering processes. In this case, the project was propelled forward precisely because it was difficult.

With the mega-transformation promised by MUTPs, however, comes complexity and risk. Much of the earlier work on the success and failure of MUTPs (for example Altshuler and Luberoff Citation2003; Kumaraswamy and Morris Citation2002; Rothengatter Citation2008; Samset Citation2008) is concerned with improving the production of projects through the objective and systematic analysis of difficulties in the project phase. Priemus (Citation2010) reviews of some of these pitfalls of megaprojects, which relate to scoping, problem definition, internal project processes, and the ever-changing political context. One key piece of advice he offers for addressing these pitfalls is ‘do not start with a solution’ (1031), and to consider alternatives. Financially, MUTPs come at vast expense, often run over budget, and as Siemiatycki (Citation2009) indicates, risk is often transferred back to the public when projects are configured as public-private partnerships.

In addition to cost over-runs, predicted travel benefits are often not realised ex-post evaluation – where evaluations are even available. Forecast traffic levels and derivative benefits are often not met after project completion, which expands as an issue in tandem with project scope (Flyvbjerg Citation2007). In a systematic review of academic literature, Nicolaisen and Driscoll (Citation2014) demonstrate bias and imprecision in both road and rail project forecasting, and also a paucity of available and inter-compatible data with which to conduct ex-post assessment of projects. Nicolaisen and Næss (Citation2015) argue that the dystopian futures of congestion and excess travel demand in base case scenarios are often overstated, especially in already congested travel environments.

Whether an MUTP is considered successful is contingent on the technologies used to develop it and the subjects it produces. The Cross City Tunnel in Sydney, Australia, for example, went bankrupt after not meeting traffic projections, and is generally considered to be a failure (Haughton and McManus Citation2012). Success and failure are bound up in how the actors within a project are constituted (Sturup and Low Citation2015). For actors involved, a key measure for the Cross City Tunnel was that a tunnel was produced, on which the project can be considered a success. The storyline of success was however displaced by one of failure – the storylines were transformed so that the solution no longer solved the problem.

The EWT provides a fresh perspective to the MUTP discussion. It and its numerous ancestor projects have failed to deliver a road link. It was controversial within the community, but still has an active present and a likely future. It is this long history and persistent revival of the EWT that led local comedian, Rod Quantock, to refer to the EWT as a ‘zombie project’ during a public meeting. Some research exists on the EWT: Legacy (Citation2016) explores the role of community groups in successfully agitating for a counter-narrative to the road project, De Martinis and Moyan (Citation2017) explore the administrative factors that led to project failure, and Searle and Legacy (Citation2019) highlight some of what was excluded from the project’s business case. In exploring how problem and solution were aligned throughout the recent life of the EWT, our paper adds to this discussion by contributing an understanding not of why the EWT was cancelled, but how it was kept alive.

Melbourne is not alone in cancelling major projects. The freeway revolts around the world in the late 1970s saw many projects cancelled, especially in the United States (Mohl Citation2004). In Toronto, Canada, a prominent example is found in the Jane Jacobs-led resistance against the Spadina Expressway. This ultimately resulted in the scaling down of inner-city highway plans (Perl, Hern, and Kenworthy Citation2015), meaning that new urban freeway construction in inner Toronto is for all purposes no longer planned. Despite the expensive and controversial cancellations of present and historical versions of the East West Link, the pace of major road building in Melbourne has not slowed. While the EWT is not actively being pursued as a project, it sits somewhere between life and death, and we wait for the zombie to once again rear its head.

5. What is the problem/solution nexus?

We refer to this process of problem and solution alignment as the problem/solution nexus (PSN): a core feature of the mentality of mega urban transport projects (MUTP), generating an inescapable, circular logic through which the construction of the project becomes the only solution to a problem (Sturup Citation2015). As a structure, it sits alongside the other features of the art of government of MUTPs: they are strongly sovereign in the structuring of power, and that they are difficult to observe critically from within because of the personal attachment people within the project acquire (Sturup Citation2010).

Mentalities of MUTPs indicate the world view of those who operate within them. Explicating the mentalities of MUTPs allows us to understand the way that projects are driven forward, the actions that will be taken, and the context within which protest will be heard. Mentalities of government are not directly observable, so we take an indirect approach, analysing the texts, speech, and actions of government (Huxley Citation2008; Rose, O’Malley, & Valverde, Citation2006). By more specifically engaging in the changing modes of technical rendition, we seek to demonstrate the historical development of the problem/solution nexus in this MUTP. These changes, at times, appear to align the problem and solution, which may lend understanding as to why the project was propelled forward, despite its limited public appeal.

Problem/solution nexus is a concept we draw from the governmentality scholarship, a field which takes as its concern ‘how we think about governing’ (Dean Citation2010, 24). In this sense, government refers to ‘the conduct of conduct’ (Foucault, 1982, in Dean Citation2010, 17), which is understood as a broad, non-hierarchical power targeting individual and social behaviours, directing them towards specific, elaborated goals. It is fruitful to understand megaprojects as infrastructural government. In the case of the EWT, certain desired behaviours would be induced and facilitated (east-west travel, for example) by creating the physical capacity for these behaviours to be more easily conducted than others (by selecting a road solution instead of a public transport or land-use solution).

A governmentality discussion is not about the Government in its contemporary manifestation as the State (Miller and Rose Citation1990; Rose, O’Malley, and Valverde Citation2006). In the governmentality literature, the State remains as a prominent actor, but one in a broader cast whose ultimate interests are in the conduct of conduct. Our specific interest in this paper, though, is less in what decisions were made, although they are important punctuations throughout the narrative, and more in the forms of knowledge, technology, rationality, and subjectivation that scripted those decisions (Dean Citation2010).

Problem/solution nexus (PSN) describes how a perceived problem and a proposed solution arise recursively and iteratively over the lifespan of a project, as identified by Sturup (Citation2015). As the programmatic translation of the will to improve, the problem-solution nexus relates to technical rendition and problematisation (Li Citation2007) through practices of calculation and the setting of boundaries around the knowable (Miller and Rose Citation1990). Programmers ‘circumscribe an arena of intervention in which calculation can be applied’ (Li Citation2007, 2), which in this case, is the arena of travel demand.

The result of technical rendition and problematisation is that

the identification of a problem is intimately linked to the availability of a solution. [Problem and solution] coemerge within a governmental assemblage in which certain sorts of diagnoses, prescriptions, and techniques are available to the expert who is properly trained (Li Citation2007, 7).

Technical rendition and problematisation translate the political-economic into terms knowable within the field of intelligibility, which ‘limits and shapes what improvement becomes’ (Li Citation2007, 8). That is, the problem/solution nexus can be thought of as that moment at which a solution and a problem align, or when the solution ‘solves’ the problem, and in doing so, seeks to exclude politicised understandings of the problem. This involves both rearticulating the problem, usually in terms of the solution, and re-aligning the solution to better fit in with problem articulation. Through these processes, problems are rendered solvable, which provides impetus for action, because the governmentalised State is supposed to solve problems (Sturup Citation2010).

The governmentality literature hints towards technical rendition as being an important process in both the construction and production of urban mobilities and circulations. Jensen, Cashmore, and Elle (Citation2017) document how changing methods of data collection and calculation on cycling in Copenhagen, Denmark has produced observable changes in policy regimes, with the incorporation of health benefits into benefit-cost calculations producing ‘new epistemic visibility’ (473), meaning that cycling became visible to the national government. Usher (Citation2014) explores the history and development of water infrastructures in Singapore, arguing that ‘changing principles underlying state intervention can tangibly be discerned in the urban form, where in this case, the shift in governmental practice was reflected down at the water’s edge’ (567) – that is, mentalities of rule can be read in their impacts on infrastructures and circulation. In these examples, cycling and water were rendered technical, producing new modes of mobility and circulation, while also ruling out other possibilities.

Our research adds to these discussions. We are expanding on current understandings of problem and solution construction using an exceptional case from the largest sort of project – the megaproject. In this case, we offer an exploration of an MUTP that was cancelled, though we are not able to be certain about what conditions produced its cancellation. While there is an extensive history of transport projects as ideas, rarely do large transport projects reach the contracting stage only to be cancelled, as these projects normally have significant momentum. Further, we develop problem/solution nexus and technical rendition as an analytical frame by offering a demonstration of its capacity to illustrate mentalities of government.

6. Findings: the PSN in key planning documents

Here, we sketch out some of the main documents in which the EWT was problematised in its most recent iteration. In subsequent sections, we identify the tropes that were mobilised in the construction of the PSN.

6.1. The Northern Central City Corridor Strategy Draft (NCCCSD)

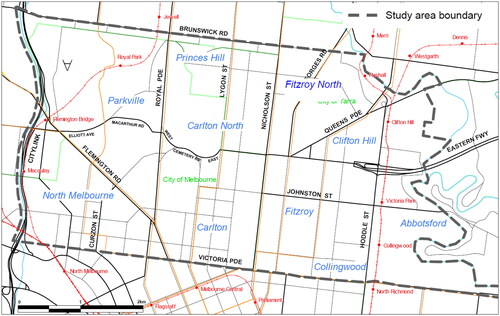

In 2003, the Northern Central City Corridor Strategy Draft (NCCCSD) (Department of Infrastructure Citation2003) presented two solutions: the first, an east-west tunnel that would bypass the central city two kilometres to the north,Footnote4 and second, a tunnel directly into the central city.Footnote5 Its concern was mainly around increasing public and active transportation mode share, while improving local amenity, within the context of Melbourne 2030s twenty percent transit mode share target. NCCCSD analysed passenger and freight movements in the inner-north area of Melbourne, bounded by the CityLink to the west and the Eastern Freeway terminus to the east (see ) – specifically chosen because ‘it is the primary area of influence of a possible road tunnel link’ (Department of Infrastructure Citation2003). NCCCSD recommended that ‘due to their high cost in comparison to their benefits no further investigation should take place on road tunnel options in the inner north’ (Department of Infrastructure Citation2003). For the EWT-like tunnel, the analysis was uncertain about the project’s ability to reduce traffic on surface streets due to induced traffic (Department of Infrastructure Citation2003). Given the then-stated aim of increasing transit mode share to twenty percent across the entire metropolitan area, the sorts of improvements required to do this, according to one of the lead NCCCSD analysts, would reduce traffic in the area, further undermining the case for an EWT (ID 02). The solution instead was to improve relevant railway lines, tram routes, and cross-town bus services, alongside a suite of land-use, parking, and active transportation measures.

Figure 2. The geographically constrained study area of the Northern Central City Corridor Strategy Draft (Department of Infrastructure Citation2003, 2). © State of Victoria, under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

6.2. Meeting Our Transport Challenges, Investing in Transport, and The Victorian Transport Plan

Problematisation of cross-town travel also occurs in the 2006 transportation strategy, Meeting Our Transport Challenges (MOTC), however this is done without specific reference to a solution like the EWT (Department of Infrastructure Citation2006). In interview, a lead NCCCSD analyst suggested that NCCCSD had effectively removed an EWT project from the Bracks government’s agenda, until his replacement, John Brumby, was taken on a helicopter ride and given a birds’ eye view of the traffic congestion at the Eastern Freeway terminus, shortly after he took over in 2007 (ID 02).

MOTC’s problematisation occurs around congestion and efficacy of the M1 motorway corridor within a broader context of the metropolitan region – much broader than NCCCSD. The M1 is characterised as having multiple roles – as a commuter route to the CBD, and as a freight route around the Port of Melbourne – and that it is close to capacity and that this will only worsen. The solution here, though, is a $740 million upgrade to the M1 corridor, as well as suggesting further problematisation of east-west travel in the form of a technical assessment, rather than any specific solution in the EWT corridor. This deferral to external assessment was reportedly a way for Bracks to evade questioning about an EWT solution (ID 04).

Investing in Transport: East West Link Needs Assessment (EWLNA), conducted on behalf of the transport/infrastructure department in 2008 by Rod Eddington (Eddington Citation2008), undertook the technical assessment suggested by MOTC. It is in EWLNA that the EWT project in its most recent form begins to take shape. EWLNA considers a wider study area than NCCCSD, but more constrained than MOTC, which nonetheless leads to specific ways of problematising. In this frame, there is an overreliance on the M1 Corridor, because Melbourne only has two cross-town motorways (the other being the Metropolitan Ring Road, much further to the north). Other cross-town routes are constrained because of the Maribyrnong and Yarra Rivers, and nonetheless are not suited to regional traffic. These cross-town routes are important because of surplus population in the western suburbs that travels towards the east for employment, education, and recreation. Freight movement from the Port of Melbourne further complicates this picture.

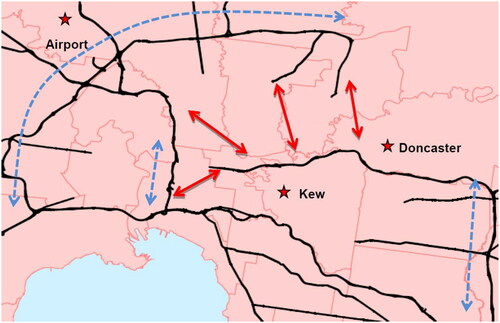

Figure 3. Lines on a map: selective representation of the major roads of Melbourne. Arterials/freeways are black, circumferential roads blue, and network ‘gaps’ red (Department of Transport Citation2013, 35). © State of Victoria, under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

EWLNA presented a large package of MUTP solutions, and per a member of the analysis team, formed much of the basis of transport planning for years to come (ID 03). Its intent was to begin a staged pipeline of infrastructure construction, with priority given to two railway MUTPs. EWLNA included a three-stage East-West Link, from the Western Ring Road in Sunshine to the Eastern Freeway terminus in Abbotsford (Eddington Citation2008). The first, central stage would connect key western arterial roads to the Port of Melbourne via a short tunnel. The second stage was the eastern half of the East-West Link (the EWT of this paper), and the third stage is the remaining western section of the road link to either the Western Ring Road or the West Gate Freeway. The full East-West Link and the other projects presented in EWLNA were to improve the economic and social disadvantage of the western suburbs, while providing more resilient transportation connections.

Later in 2008, the Government of Victoria released an updated metropolitan transportation strategy: the Victorian Transport Plan (VTP) (DTPLI Citation2008). This plan incorporated Stage 1 of EWLNA, because it responded most effectively to the greatest perceived need – an additional crossing of the Maribyrnong River to act as an alternative to the West Gate Bridge. For the most, however, VTP’s response to the east-west travel problematisation was to prioritise the construction of the Tarneit railway link from EWLNA, now branded as the RegionalFootnote6 Rail Link. The aim of the RRL project was to provide additional, dedicated trackage for inter-city rail services from Geelong, Ballarat, and Bendigo, cities to the west of Melbourne, while also providing a new railway corridor in the western suburban growth corridor.Footnote7 This would enable existing infrastructure to be allocated to improved suburban railway services, resolving much of the east-west travel problematic that had been identified in EWLNA.

6.3. Plan Melbourne and the EWT business case

In 2010, a State parliamentary election saw the defeat of Brumby’s Labor party and the accession of the opposition Liberal party under the leadership of Ted Baillieu. During this time, the eastern section of the full EWT re-appeared on the agenda. According to an interviewee (ID 05), Baillieu and other cabinet ministers found the EWT particularly attractive because it would wedge left-leaning, inner-urban electorates. Significant advances in understanding the problem were taking place, but these were hidden behind confidentiality provisions. The eventual solution decided on was presented in more detail in the East-West Link Business Case (EWTBC) from March 2013 (Department of Transport Citation2013), however this particular document was only made publicly available after the crucial election that saw the EWT project stopped.

In early March 2013, Baillieu stepped down and was replaced as Premier by Denis Napthine (ABC News Citation2013). Under Napthine’s premiership, an updated metropolitan land-use and transportation strategy named Plan Melbourne (PM14) was produced (DTPLI Citation2014), led by a Ministerial Advisory Committee (MAC). PM14 included the EWT in its transport chapter, to be followed by a western section and river crossing at a later time. Inclusion of the EWT in PM14 was contentious, though, with a member of the MAC indicating that the Minister for Planning’s office had shoehorned in a new transport chapter that included the EWT, where the earlier, MAC-led drafts had focused on public transport (ID 08). As such, five of the six ministerial advisers quit the committee in December 2013 (Dow Citation2013).

There is a familiar set of justifications in PM14. The full EWL would ‘transform the way people move around Melbourne, help alleviate our reliance on the M1 corridor for cross-city road connections, and provide greater resilience in the transport network’ (Department of Transport Citation2013). Unlike previous iterations, though, the eastern section would be constructed before the western section – this, per EWTBC, would fix congestion at the Eastern Freeway terminus by connecting disconnected freeways, allow for a new cross-city link, and improve north-south public transport routes. The issue of a lack of river crossings, as stressed in EWLNA and VTP, is less prominent in the PM14/EWTBC problematisation – a useful discursive shift, as the EWT does not cross any river.

The EWT, however, was not to be. In the context of an upcoming November parliamentary election, the Leader of the Opposition Labor party, Daniel Andrews, promised not to proceed with the EWT should his party win the election – which they went on to do (Campbell, Johnston, and Ainsworth Citation2014).

7. Cross-town travel and the problem of freeways that just end

There are two closely-related stories that were repeatedly told in the documents in question – that discontinuous freeway networks are a bad thing, and that cross-town travel is becoming increasingly difficult in Melbourne. Each of these relates to that central problem of transport planning – the physical separation of activities in cities. That the Eastern Freeway ends is a major problem, in part because of where it ends, but also because of discourses of hierarchy, resilience, and, of course, congestion. Related to this is an emerging discussion about the difficulties of travelling from west to east in metropolitan Melbourne. These tropes are related because they are similarly problematised – they emerge out of a discussion reliant on techniques of transport modelling. Studies in which modelling is structured around road network bottlenecks will unsurprisingly produce solutions that are roads.

The ‘disconnected freeway’ is a recurring discursive formation in the source documents over the study period. Perhaps one of the better ‘demonstrations’ of the missing links in the road network can be found in EWTBC, attached here as . This image selectively represents the road network to make it appear as though the motorway and arterial network contains major gaps. It is part of the production of the discourse of the disconnected freeway, which can be solved by the construction of a freeway.

The horror of the freeway that ends takes place within logics of road hierarchies and technologies of civil engineering. These discourses hold that different roads have different purposes, local traffic should not mix with regional traffic, and traffic should be, where possible, as free-flowing, and fast as possible (Low, Gleeson, and Rush Citation2003). NCCCSD, EWLNA, and PM14/EWTBC all agree that creating a motorway link along the project corridor would be solve the Eastern Freeway ending abruptly, allowing cross-town traffic to bypass local and arterial streets.

NCCCSD frames traffic congestion as being primarily a problem local to the (relatively small) study area – yet only 10% of vehicles completed the entire cross-town trip to the CityLink corridor. In the more broadly scoped EWLNA, the way in which ‘city’ and ‘cross-city’ are defined is different to NCCCSD. Using the two riversFootnote8 as a screen line, the Eddington Report predicts 40% more traffic by 2031 – and recommends a new road link in the form of the full East-West Link, linking the Western Ring Road to the Eastern Freeway. Because NCCCSD did not extend as far as EWLNA geographically, its understanding of the problem of cross-town traffic was substantially different. The inclusion of the greater western suburbs in EWLNA traffic modelling renders the solution more viable, but even in this case, EWLNA made explicit that the connections in the western part of the broader corridor were of a higher priority, and that railway projects were of a higher priority.

That changing the parameters of a study leads to different conclusions should not come as a surprise, nor is the refinement of technical knowledge in practices of project planning something undesirable. However, it is of interest here as this refinement relates to the spending of multiple billions of dollars, and it is also bound up in and communicated through the central tropes of the problem/solution nexus. A lucid demonstration of this can be found in EWLNA in a series of maps visualising the government's argument for the tunnelFootnote9. In a short section characterising the Eastern Freeway, the disconnected freeway line is deployed in the very first sentence. The section seeks to dispel “prevailing myths” (Eddington Citation2008, 129) about the Eastern Freeway, including that Eastern Freeway traffic is predominantly bound for the city centre, to the south of the freeway terminus, rather than through to the western and northern suburbs. EWLNA produced a series of comparative maps aiming to dispel this particularly myth: the traffic distribution from the original NCCCSD, the NCCCSD traffic distribution, but re-calculated by modelling firm Veitch Lister on behalf of EWLNA, and finally, the modelling conducted under EWNLA parameters by Veitch Lister (figures 69, 70, & 71 respectively, Eddington Citation2008, 130–131). These three maps are all communicated in a comparable design, presumably to highlight the differences between the historical and present studies to a audience of politicians, non-trained policymakers. The differences are stark – in the original (fig 69) and updated (fig 70) NCCCSD modelling, less than 10% of the Eastern Freeway traffic continues to the. Eastern Freeway traffic continues to the West, whereas in EWLNA (fig 71) this is almost 25%. Importantly, though, what we observe here is that how in constructing the perceived ‘need’ for mega infrastructure, there is also a process of changing technical parameters to fit the mega infrastructure. EWLNA, in part through its broader focus, re-centred the need for an east-west motorway link.

The use of a cross-town travel trope is instructive here, because it ends up being irrelevant: the version of the EWT that was eventually contracted and cancelled did not actually cross either of the rivers, so it is not clear how the tunnel was to solve the river crossing problem or improve network resilience, something several actors pointed to in interview (ID 01, 05). The major driver behind support for the full East West Link in EWLNA was the additional crossing of the Yarra and Maribyrnong river corridor, so that the EWT solution did not address this problem allowed for those involved in the project to question its efficacy. The EWT solution did not solve the problem of over-reliance on the West Gate Bridge.

MUTPs shape and structure the thinking about transport in cities. The continual and repeat narrowing of scope to corridors and subsections of Melbourne trains professionals to conduct their studies in this way, and is reflective of the infrastructure turn (Dodson Citation2009). A senior bureaucrat pointed to the project-oriented approach to transport planning, and the sorts of knowledge it produces. While in no way dismissing the aptitude or will to improve of analysts, the informant suggested that professional experience in projects means that the world is seen in terms of the constrained geographies of projects, rather than taking a more holistic, network wide approach (ID 01). This is demonstrated in how the east-west divide was elucidated in several of the key reports. As suggested by much of the governmentality literature, part of the practice of problematisation includes the shifting and reshaping of the intelligible field; and in this case, it also includes the establishment of conceptual boundaries inside a geography, which produce a geography that can be governed via MUTP.

For a lead analyst in EWLNA, the elucidation of an east-west divide in Melbourne was somewhat eye-opening. Traditionally, Melbourne had been considered divided into the north and the south – culturally, at least – whereas what EWLNA allowed was for an understanding of a major divide between the central and eastern sections of the city and the rapidly growing western suburbs (ID 05). The extent of this problem meant that it needed to be solved, and this was framed in moral terms – that the jobs-poor west needed access to the centre and east of the city. During this process though, other actors inside EWLNA campaigned for the inclusion of railway connections from the western suburbs to the city centre, resulting in the inclusion of two railway MUTPs. Initially, said a railway campaigner in interview, the study team ‘got straight into designing road links and drawing lines on maps and working out options for different routes’, but after several tense and often combative months, railway connections were included in the study (ID 02) – and ultimately ended up being prioritised over the very road EWLNA was supposed to be problematising.

These changes to the scope of problematisation speak to the heart of problem-solution nexus conceptually. How the problem was defined is altered, leading to certain solutions appearing more viable – in this case, the full East-West Link. EWLNA included a broader geographic scale and a changed geographic definition.Footnote10 That is, by changing how the geography of the studies was defined, EWLNA was able to present a case that was more supportive of the solution that it was set up to test the viability of. Whether an east-west link is needed depended on where the line between east and west is drawn in a specific problematisation.

The definition of east and west plays an important role in the technical rendition of travel in the EWT project. When the geographical scope of the respective transport studies is changed – or, when the mode of technical rendition is altered – the available solutions change. A tunnel solution is presented in NCCCSD because of perceived traffic problems, but is rejected because the estimates of future traffic problems in the are not substantial enough to warrant proceeding. Traffic is measured differently in subsequent documents, making a tunnel an increasingly viable solution. It is here, through technologies of travel demand forecasting, that we see attempts to construct a problem/solution nexus based around east-west travel.

8. The problem of value for money

The problems of disconnected freeways and cross-town travel are related to a value for money trope, in that the rectification of these connectivity problems underpins the major technology of the VFM trope: benefit-cost analysis (BCA). BCA considers the welfare effects of project implementation and non-implementation against a base case (Rouwendal Citation2012). For a project or course of action to make economic sense, its benefits should be higher than its costs. BCA appears to be an important technology used in PSN formation, because it speaks of the economic viability of the solution, feeding into a sense of moral imperative. This section tracks the evolving use of forms of BCA technologies in the construction of the EWT’s PSN.

Each of the iterations of the EWT family of projects recognises the potentially large direct benefits of an EWT solution. Infrastructure projects are understood to have wide-ranging economic benefits, including, for the EWT, ‘travel time savings, reduced vehicle operating costs, fuel savings, accident reductions, reduced carbon dioxide emissions, increased agglomeration, and attraction of greater labour supply’ (Department of Transport Citation2013). While NCCCSD recognised the potential benefit of an EWT project in removing traffic from local streets, further discussion of a tunnel was not recommended because of the predicted high costs compared to benefits. An EWT project would be ‘unlikely to give economic returns in proportion to the investment required, [and] the high level of investment required will divert resources from investment in other transport needs’ (Department of Infrastructure Citation2003).

While the BCA presented in NCCCSD was rudimentary this nonetheless demonstrates how the technology used in PSN formation was altered for the solution to appear viable. When rendered technical through traditional modes of BCA, the EWT was not a viable solution. For the EWT to become a viable solution, the boundaries of the ‘intelligible field’ (Ferguson, in Li Citation2007, 7) of the project had to be broadened.

This story begins to change in EWLNA and EWTBC. EWLNA presented a benefit-cost analysis of the MUTP pipeline proposed therein. The total package of projects would cost an estimated AU$15 billionFootnote11, with the EWT being approximately AU$5.5 billion (Eddington Citation2008). The benefits in EWLNA, however, are only presented in aggregate across all projects. EWTBC included numerous BCRs of various solution configurations, with a financial cost of AU$6.8 billion.Footnote12 A summary of the BCRs is presented in .

Table 3. Comparison of the different modes of benefit-cost analysis on some of the EWT iterations (Eddington Citation2008; Department of Transport Citation2013).

The inclusion of WEBs into the economic techniques of EWT problematisation is a crucially important discursive turn, as it enabled the solution to more effectively and convincingly solve a more clearly understood problem. In both EWLNA and EWTBC, project proponents incorporated wider economic benefits (WEBs) into BCA, which makes the BCR for the EWT marginally positive in certain configurations. Traditional measures of project benefits (travel time savings, decreased fuel costs, decreased accident costs) could not justify any of the solution iterations, with the major exception of EWTBC’s surface option, which would have involved an at-grade motorway through a densely developed urban area. Widening the scope of economic benefits is chiefly conducted by the inclusion of agglomeration economies and other related welfare effects (Legaspi, Hensher, and Wang Citation2015). WEBs render the solution worthwhile because they (mostly) push the BCR above one, where the traditional, direct approach for the EWT indicated that the project was not worth it.

This is not to say, however, that WEBs were included in analysis to make viable the EWT solution, or any of the other EWLNA projects. This change to the BCA techniques may be read in the context of a broader turn in which the role of infrastructure in contemporary urban economies was increasingly understood. An EWLNA analyst (ID 03) stated that discursively, Eddington’s review was amongst the earliest elucidations of the importance of cities to the economy, especially the mediatory role of infrastructure. To this end, another interviewee (ID 06) specifically pointed to the incorporation of WEBs into EWLNA’s economic analysis as being a central innovation in recent Australian transport planning. A change in the method of technical rendition of a project has resulted in the viability of the solution.

9. Conclusions

The problem/solution nexus limits available solutions in terms of specified problems, while also working to limit available problems in terms of specified solutions, meaning that the solution that eventually arises should not be understood as selected based solely on its capacity to solve some pre-existing problem. We demonstrated this in the case of the EWT by exploring how the technical parameters of technologies of travel demand forecasting and benefit-cost analysis were manipulated in the recent history of the project. Changing how the project was rendered technical – such as the addition of WEBs in BCA – made the EWT solution appear more viable. There is a sense that the project was decided upon before it was clearly problematised.

We do not argue for or against the relative merits of an idealised, rational approach to infrastructure planning; nor do we expect to stamp out the practice of problems and solutions co-generating each other. We ask questions of reflection, to try to identify where PSNs occur in practice, and to allow for possibility that other competing modes of technical rendition might be incorporated into transportation decision-making – such as technologies of participatory governance. Given the well documented limitations and problems of travel demand forecasting (Nicolaisen and Driscoll Citation2014) and benefit cost analysis (Rouwendal Citation2012), different ways of knowing transportation problems and solutions can only serve to improve decision-making, as Searle and Legacy (Citation2019) suggest in their work on the EWT.

This discussion adds to the governmentality literature in several important ways. We have attempted to build upon the existing discussion of problem/solution nexus and technical rendition in their many guises. We do so by illustrating the beginnings of a methodological pathway for exploring problem/solution co-definition, and where this has already been occurring in the literature. Additionally, we have presented an analysis of a calculative practice that has thus far been relatively untouched by the governmentality literature. While the census has been a popular topic (Hannah Citation2009; Starkweather Citation2009), the potential for further study of transport planning as calculative practice of government is immense. Drawing the attention of the governmentality literature to infrastructure planning may also help in understanding why and how such large projects are so appealing to policy-makers, via the promise of a sort of mega-government.

Through exploring the problem/solution nexus of the EWT, we have demonstrated a troubled history of problematisation of a project in this corridor. In NCCCSD, public transport absorbed much of the travel growth, leading to a reduction in road traffic in the corridor and restricting the perceived need for the EWT. In EWLNA, rail-based transit projects were the preferred solution. In EWTBC, the knowledge produced using calculative techniques provided only limited support for an EWT. While traffic models indicated that the road would be used, the economic models required expansion of both the project scope and the definition of benefits to predict a positive economic return on the project.

Road building and megaproject construction continues in Melbourne. Since the cancellation of the EWT, the Victorian government has contracted three major motorway projects. The West Gate Tunnel project is a combined sections 1 b and 3 of the full East West Link as envisaged in EWLNA. The North East Link project connects different disconnected motorways together, and at its widest spans twenty lanes across (Towell Citation2018). And in Melbourne’s south-eastern suburbs, a freeway under construction will pass through significant wetland environments (Jacks Citation2019). This is in addition to over seven hundred kilometres of additional arterial roads in the ever-growing fringe developments around Melbourne (Pittman, Stone, and Sturup Citation2017). In the most recent election, the State Labor government promised a 90 km railway loop connecting Melbourne’s middle and outer suburbs. Mostly underground, the Suburban Rail Loop is presently estimated to cost $50 billion (Carey Citation2019). While this manifestation of the EWT was cancelled, the conditions that enabled its existence remain.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful reflections on and contributions to this paper. We would also like to acknowledge that an earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2017 State of Australian Cities conference in Adelaide, Australia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We refer to the East West Link (Eastern Section) as the EWT for short – where T refers to tunnel.

2 The Eastern Freeway is shown on the right side of Figure 1.

3 Henceforth, these plans will be referred to respectively as NCCCSD, MOTC, EWLNA, VTP, EWLBC, & PM14

4 In Figure 2, this corresponds to the corridor running east-west through the centre of the map, from Citylink to Eastern Freeway

5 In Figure 2, this would be a path from the Eastern Freeway terminus at Clifton Hill, to the centre-bottom of the map.

6 In Australian English usage, ‘regional’ refers to the areas outside of the main coastal metropoles.

7 The RRL took on an additional nation-building frame when it was selected for additional funding by the Australian commonwealth government as part of the stimulus package to mitigate against the Global Financial Crisis.

8 The Yarra and the Maribyrnong.

9 We sought to reproduce these maps for clarity, but were unable to resolve copyright ownership in time for publication

10 In this case, the location of the centreline was altered from the CityLink to the Maribyrnong River.

11 This figure is drawn from table 23, page 234 of Eddington 2008, however there is some inconsistency between project costs throughout the document.

12 This is the “estimated total risk adjusted capital cost” for the EWT per the 2013 Business Case, not including additional extensions to the Port of Melbourne. The risk adjusted capital cost for all three sections is estimated at AU$16.1 billion.

References

- ABC News. 2013. “Baillieu stands down as Victorian Premier.” ABC News, March 7. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2013-03-06/baillieu-stands-down-as-victorian-premier/4557014

- Altshuler, A., and D. Luberoff. 2003. Mega-Projects: The Changing Politics of Urban Public Investment. Washington: Brookings Institution Press.

- Andrews, D. 2015. “East West Link Deal Finalised.” June 15. https://www.premier.vic.gov.au/east-west-link-deal-finalised/

- Boholm, Å. 2005. “Greater Good’ in Transit: The Unwieldy Career of a Swedish Rail Tunnel Project.” Focaal 2005 (46): 21–35.

- Campbell, J., M. Johnston, and M. Ainsworth. 2014. “East West Link contracts are not binding, says Daniel Andrews.” Herald Sun, September 30. https://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/victoria/state-election/east-west-link-contracts-are-not-binding-says-daniel-andrews/news-story/fcbcdfd9b13cf630854b45cad266cc8b

- Carey, A. 2019. “Game-changer or white elephant: experts weigh in on suburban rail loop.” The Age, May 13. https://www.theage.com.au/federal-election-2019/game-changer-or-white-elephant-experts-weigh-in-on-suburban-rail-loop-20190513-p51mwo.html

- De Martinis, M., and L. Moyan. 2017. “The East West Link PPP Project’s Failure to Launch: When One Crash-through Approach is Not Enough.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 76 (3): 352–377.

- Dean, M. 2010. Governmentality: Power and Rule in Modern Society. 2nd ed. London, UK: Sage.

- Department of Infrastructure. 2003. Northern Central City Corridor (NCCC) Strategy Draft. Melbourne, Australia: State of Victoria.

- Department of Infrastructure. 2006. Meeting Our Transport Challenges: Connecting Victorian Communities. Melbourne, Australia: State of Victoria

- Department of Transport. 2013. East West Link: Business Case (22 March 2013). Melbourne, Australia: Victorian Government. http://www.premier.vic.gov.au/east-west-link-announcement

- Dodson, J. 2009. “The ‘Infrastructure Turn’ in Australian Metropolitan Spatial Planning.” International Planning Studies 14 (2): 109–123.

- Dow, A. 2013. “Doubts over planning strategy after key advisers quit.” The Age, December 12. https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/doubts-over-planning-strategy-after-key-advisers-quit-20131212-2z8lz.html

- DTPLI. 2008. The Victorian Transport Plan. Melbourne, Australia: State of Victoria.

- DTPLI. 2014. Plan Melbourne: Metropolitan Planning Strategy. Melbourne, Australia: State of Victoria. http://www.planmelbourne.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/131362/Plan-Melbourne-May-2014.pdf

- Eddington, R. 2008. Investing in Transport: East West Link Needs Assessment. Melbourne, Australia: State of Victoria.

- Farrant, D. 1994. “Freeway protesters keep watch on junk.” The Age, October 16. https://fairfaxmedia.newspapers.com/image/122996241/

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2007. “Policy and Planning for Large Infrastructure Projects: Problems, Causes, Cures.” Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 34 (4): 578–597.

- Gleeson, B., C. Curtis, and N. Low. 2003. “Barriers to Sustainable Transport in Australia.” In Making Urban Transport Sustainable, edited by N. Low and B. Gleeson, 201–220. Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hannah, M. G. 2009. “Calculable Territory and the West German Census Boycott Movements of the 1980s.” Political Geography 28 (1): 66–75.

- Haughton, G., and P. McManus. 2012. “Neoliberal Experiments with Urban Infrastructure: The Cross City Tunnel.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 36 (1): 90–105.

- Huxley, M. 2008. “Space and Government: Governmentality and Geography.” Geography Compass 2 (5): 1635–1658.

- Jacks, T. 2019. “Mordialloc Freeway risks polluting water feeding to UN-protected wetlands, documents reveal.” The Age, February 24. https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/mordialloc-freeway-risks-polluting-water-feeding-to-un-protected-wetlands-documents-reveal-20190224-p50zvn.html

- Jensen, J. S., M. Cashmore, and M. Elle. 2017. “Reinventing the Bicycle: How Calculative Practices Shape Urban Environmental Governance.” Environmental Politics 26 (3): 459–479.

- Kumaraswamy, M. M., and D. A. Morris. 2002. “Build-Operate-Transfer-Type Procurement in Asian Megaprojects.” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 128 (2): 93–102.

- Legacy, C. 2016. “Transforming Transport Planning in the Postpolitical Era.” Urban Studies 53 (14): 3108–3124.

- Legaspi, J., D. Hensher, and B. Wang. 2015. “Estimating the Wider Economic Benefits of Transport Investments: The Case of the Sydney North West Rail Link Project.” Case Studies on Transport Policy 3 (2): 182–195. doi:.

- Li, T. M. 2007. The Will to Improve: Governmentality, Development and the Practice of Politics. Durham, London: Duke University Press.

- Low, N., B. Gleeson, and E. Rush. 2003. “Making Believe: Institutional and Discursive Barriers to Sustainable Transport in Two Australian Cities.” International Planning Studies 8 (2): 93–114.

- Metropolitan Transportation Committee. 1969. Melbourne Transportation Study/Prepared for Metropolitan Transportation Committee by Wilbur Smith and Associates and Len T. Frazer and Associates. Carlton, VIC: Metropolitan Transportation Committee.

- Miller, P., and N. Rose. 1990. “Governing Economic Life.” Economy and Society 19 (1): 1–31.

- Mohl, R. A. 2004. “Stop the Road: Freeway Revolts in American Cities.” Journal of Urban History 30 (5): 674–706.

- Nicolaisen, M. S., and P. A. Driscoll. 2014. “Ex-Post Evaluations of Demand Forecast Accuracy: A Literature Review.” Transport Reviews 34 (4): 540–557.

- Nicolaisen, M. S., and P. Næss. 2015. “Roads to Nowhere: The Accuracy of Travel Demand Forecasts for Do-Nothing Alternatives.” Transport Policy 37: 57–63.

- Perl, A., M. Hern, and J. Kenworthy. 2015. “Streets Paved with Gold: Urban Expressway Building and Global City Formation in Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver.” Canadian Journal of Urban Research 24 (2): 91–116.

- Peters, D. 2010. “Digging through the Heart of Reunified Berlin: Unbundling the Decision-Making Process for the Tiergarten-Tunnel Mega-Project.” European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research 10 (1): 89–102.

- Pittman, N., J. Stone, and S. Sturup. 2017. “Impending traffic chaos? Beware the problematic West Gate Tunnel forecasts.” The Conversation, July 7. https://theconversation.com/impending-traffic-chaos-beware-the-problematic-west-gate-tunnel-forecasts-79331

- Priemus, H. 2010. “Mega-Projects: Dealing with Pitfalls.” European Planning Studies 18 (7): 1023–1039.

- Rose, N., P. O’Malley, and M. Valverde. 2006. “Governmentality.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 2 (1): 83–104.

- Rothengatter, W. 2008. “Innovations in the Planning of Mega-Projects.” In Decision Making on Mega-Projects: Cost-Benefit Analysis, Planning and Innovation, edited by H. Priemus, B. Flyvbjerg, and B. Van Wee, 66–84. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Rouwendal, J. 2012. “Indirect Effects in Cost-Benefit Analysis.” Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis 3 (1): 1–27.

- Rundell, G. 1985. “Melbourne Anti-Freeway Protests.” Urban Policy and Research 3 (4): 11–21.

- Samset, K. 2008. “How to Overcome Major Weaknesses in Mega-Projects: The Norwegian Approach.” In Decision Making on Mega-Projects: Cost-Benefit Analysis, Planning and Innovation, edited by H. Priemus, B. Flyvbjerg, and B. Van Wee, 173–188. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Searle, G., and C. Legacy. 2019. “Australian Mega Transport Business Cases: Missing Costs and Benefits.” Urban Policy and Research 37 (4): 458–473.

- Siemiatycki, M. 2009. “Delivering Transportation Infrastructure through Public-Private Partnerships: Planning Concerns.” Journal of the American Planning Association 76 (1): 43–58.

- Starkweather, S. 2009. “Governmentality, Territory and the U.S. Census: The 2004.” Political Geography 28 (4): 239–247.

- Sturup, S. 2010. Managing Mentalities of Mega Projects: The Art of Government of Mega Urban Transport Projects. Doctor of Philosophy, University of Melbourne, Melbourne.

- Sturup, S. 2015. “The Problem/Solution Nexus and Its Effect on Public Consultation.” In Instruments of Planning: Tensions and Challenges for More Equitable and Sustainable Cities, edited by R. Leshinsky and C. Legacy, 45–58. Milton, UK: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Sturup, S., and N. Low. 2015. “Storylines, Leadership and Risk: Some Findings from Australian Case Studies of Urban Transport Megaprojects.” Urban Policy and Research 33 (4): 490–505.

- Sturup, S., and N. Low. 2019. “Sustainable Development and Mega Infrastructure: An Overview of the Issues.” Journal of Mega Infrastructure & Sustainable Development 1 (1): 8–26.

- Towell, N. 2018. “North-East Link: Superhighway through Melbourne’s east.” The Age, September 9. https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/north-east-route-revealed-20180909-p502nd.html

- Trapenberg Frick, K. 2008. “The Cost of the Technological Sublime: Daring Ingenuity and the New San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge.” In Decision-Making on Mega-Projects: Cost-Benefit Analysis, Planning and Innovation, edited by H. Priemus, B. Flyvbjerg, and B. Van Wee, 239–262. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Usher, M. 2014. “Veins of Concrete, Cities of Flow: Reasserting the Centrality of Circulation in Foucault’s Analytics of Government.” Mobilities 9 (4): 550–569.

- Ward, E. J., and P. Skayannis. 2019. “Mega Transport Projects and Sustainable Development: Lessons from a Multi Case Study Evaluation of International Practice.” Journal of Mega Infrastructure & Sustainable Development 1 (1): 27–53.