Abstract

Present-day energy systems are shaped by past decisions, which were informed by contemporary considerations about different energy sources and visions of the future. Hence, today, at a time when a new energy transition is on the agenda, it is important to understand those past rationales that account for previous energy transitions, notably the introduction of large-scale nuclear power in the 1970s. This article argues that in the debates in the European Parliament, representatives of West European mainstream parties specialising in energy and environmental policy used arguments that reflect the key components of what we today call sustainability. The analysis of the debate on nuclear energy megaprojects in the European Parliament in the mid-1970s examines the arguments used, reflecting expectations about the future that shaped long-term energy planning. Transnational protests at the building sites of nuclear power plants of the mid-1970s were viewed as a threat to what most European policymakers at the time considered an indispensable energy transition. The debate thus offers unique insights into the arguments that underpinned the planned transition to nuclear energy and nuclear megaprojects and attempts to improve popular acceptability, including via better information and participation. The article highlights that those advocating a transition to nuclear power used arguments surprisingly similar to those mobilised in current debates about energy transitions and megaprojects, including the search for nuclear waste disposal sites.

1. Introduction

‘For many years there has been no area of modern technology, no technological development on which opinions have been so controversial […] views are put forward with such reluctance to compromise and such missionary zeal, that one sometimes doubts whether the decisions needed in this sector for the future can in fact be taken’ (European Parliament Citation1976a, 36).

When on 16 January 1976 the European Parliament’s (EP) rapporteur, the West German Christian democrat Hanna Walz, introduced her report on a ‘Community policy on the siting of nuclear power stations taking into account their acceptability for the population’ to the EP plenary in Strasbourg, she was clearly exasperated with the level of controversy around nuclear power. She viewed the critique of nuclear energy as a threat to an energy transition she deemed necessary, and criticised the apparent irrationality of the debate: to her it seemed to be a clash of ‘convictions’, rather than an exchange of rational arguments (European Parliament Citation1976a, 36).

However, controversy was largely absent from the debate in the EP itself, at a time when most political parties in Europe (Mez and Ollrogge Citation1979) and almost all MEPs supported the expansion of nuclear power. Only the Scottish Labour MEP Willie Hamilton objected (European Parliament Citation1976a, 63–4), and a Liberal Danish MEP abstained.Footnote1

The 1970s were the heyday of nuclear megaprojects. Expecting continuously rising energy demand, as experienced during the post-war boom, utilities ordered ever-bigger nuclear reactors. Numerous new plants were built in Western Europe, as well as in Communist Eastern Europe (Josephson, Meyer, and Kaijser Citation2021). The 1973 oil shock accelerated this trend (Bösch and Graf Citation2014). Nuclear power – which had been promoted by governments, international organisations, including the European Communities (EC), industry and science since the 1950s (Curli Citation2017, 103; Reitbauer Citation2015; Josephson and Lehtonen Citation2021; Kirchhof and Meyer Citation2021; Hamblin Citation2021) – seemed the only readily available alternative energy source for an energy transition away from imported oil.

However, by the mid-1970s, public opposition to nuclear power was growing (Presas I Puig and Meyer Citation2021), in particular in Western Europe’s border regions, where many nuclear power plants were constructed along Europe’s major rivers that provided ample cooling water (Kaijser and Meyer Citation2021), and where European power lines intersected (Lagendijk Citation2015; Högselius, Kaijser, and van der Vleuten Citation2016). People on the other side of national borders resented that they were potentially affected, but rarely consulted. This aggravated grievances and fuelled ‘transboundary’ European protest (Kaijser and Meyer Citation2018), such as on the upper Rhine (Kirchhof and Meyer Citation2021).

Cross-border problems called for supranational solutions, or so it seemed to the institutions of the EC, the predecessor of today’s European Union (EU). Already the original Euratom Treaty of 1957 had not only committed the EC to promoting nuclear energy, but also to protecting citizens against radiation (Euratom Citation1957, art. 2), in particular, where nuclear activities had potential cross-border impacts (Euratom Citation1957, art. 31 and 37). Thus, at its January 1976 plenary, the European Parliament (EP) demanded using relevant EC competences to improve the spatial planning of nuclear megaprojects across Western Europe. By taking the initiative on this issue, MEPs pursued three objectives: first, responding to and defusing anti-nuclear protest and transboundary conflicts, secondly, defending the - planned or ongoing - energy transition towards nuclear power, and thirdly, strengthening EC institutions and EC energy policy.

Before the direct elections of 1979, with a view to EC law-making, the EP was a largely powerless assembly. EP members (MEPs) held dual mandates (Hähnel Citation2020). Most MEPs who joined the Strasbourg assembly, were committed to the project of European integration, and familiar with national (energy) debates (Oberloskamp Citation2020; Shaev Citation2021). At the same time, they were active agenda-setters at the European level (Meyer Citation2021, 77; Roos 2021), using instruments such as the ‘own initiative report’, like Walz’ report discussed in January 1976. Such activities impacted on EC policy making (Patel and Salm Citation2021), as also in this case: by the end of 1976, the European Commission (Citation1977) responded to the EP demands by proposing binding European legislation.

Parliamentary debates have been analysed by researchers in order to gain insights into discourses on energy policy, energy transitions, and megaprojects (Edberg and Tarasova Citation2016; Oberloskamp Citation2020). The EP debate can be read as a proxy of the broader discussion among political parties and political elites in the EC. Remarkably, the EP not only provided a public forum for discussion, but also initiated this debate through its report. The January 1976 plenary debate was the first extensive public engagement with the growing conflicts around nuclear megaprojects in an EC context. Previous EP debates on nuclear issues were largely limited to technical and research aspects. Only recently had the EP started to address safety and public concerns in a more critical manner in the context of parliamentary questions (e.g., European Parliament Citation1975).

This article argues that this EP debate was not only about the cross-border impacts of nuclear megaprojects, but effectively a discourse on the ongoing transition to nuclear energy more generally. Remarkably, MEPs justified the need for this transition using arguments that cover all relevant aspects of what we now call sustainability. By examining this debate, we can obtain critical insights for present-day debates defending energy infrastructures for current ‘sustainability’ transitions (Hasenöhrl and Meyer Citation2020). Of course, the debates of the mid-1970s took place under very different political and economic conditions – against the backdrop of an economic - and energy - crisis after almost thirty years of unprecedented growth, under the geopolitical conditions of Cold War competition. At the time, references to nuclear developments in the Communist East were frequently used as (pro-nuclear) arguments. Unlike in Sweden in the 1970s (Ekberg and Hultman Citation2021), climate change had not become an issue in European energy policy (Geyer Citation2016; Sarasin Citation2021, 17–31). Nevertheless, with the rise of environmentalism and the debate about the ‘Limits to Growth’ (Meadows et al. Citation1972), the ecological implications of energy decisions gained greater relevance. Indeed, the longstanding critic of nuclear power Amory Lovins already used the term ‘sustainable sources’ referring to sun and wind (Lovins Citation1976, 75). In this text, ‘sustainability’ and ‘transition’, will be used as analytical concepts – rather than as normative or source terms.

The article is organised as follows. In the subsequent section, I will discuss the role of European institutions in the energy transitions of the 1970s, and provide some background on the speakers during the plenary debate analysed in this article. Thereafter, I will discuss and operationalise the concepts of transitions and sustainability. The third and main part analyses the debate about the siting of nuclear megaprojects with an emphasis on what I call sustainability arguments. The conclusions will highlight some insights for present energy debates.

2. European institutions and the siting of nuclear megaprojects

The EC institutions had long promoted nuclear power in line with a European vision of modernity and peaceful cooperation through public relations (Spiering Citation2011; Leslie and Mercelis Citation2019) and funded nuclear research cooperation since the 1950s (Curli Citation2017; Josephson and Lehtonen Citation2021). Hence, key representatives of the EC institutions viewed the growing transnational and transboundary protests against nuclear power culminating in the spectacular site occupation at Wyhl (West Germany) in February 1975 (Tompkins Citation2016; Milder Citation2017; Häni Citation2018; Pohl Citation2019) as a threat to energy security (Rucht Citation1980, 27–31; European Commission Citation1974a). Given the European dimension of the cross-border impacts of nuclear plants, different EC actors presented ideas for how to resolve the issue at the European level, through regulation.

2.1. Tindemans report

The first response could be found in a document commissioned by the member states to offer new visions for future European integration. In the spirit of European federalism, Belgian Premier Leo Tindemans’ ‘Report on European Union’ of December 1975 (Nielsen-Sikora Citation2007) called for

‘a common body responsible for regulating and controlling nuclear power stations, with similar responsibilities and powers to those of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in the United States. Control should be exerted over the siting, construction and operation of the power stations, the fuel cycle and the disposal of radioactive and thermal waste (Tindemans Citation1976, 27).

Established at the European level, independent of direct member state pressures, Tindemans reasoned, such a body would enjoy more trust among citizens, and thus help to defuse the conflicts over nuclear sites. Tindemans’ proposals were mentioned in the EP debate January 1976, but were never turned into concrete policy.

2.2. European Parliament

Already in the summer of 1974, the members of EP Committee on Energy, Research and Technology had started to discuss how best to react to growing anti-nuclear protest (Walz Citation1975, 3). They opted for an own initiative report (Walz Citation1975). A formal parliamentary resolution (European Parliament Citation1976b) proposed concrete measures for the Commission and the member states to take. Like Tindemans, the EP Committee assumed that more transparency and cross-border consultation would increase public acceptance of nuclear megaprojects it considered indispensable for energy security. The resolution advocated five kinds of measures:

First, a Community siting policy ‘based on a Community map’ and the ‘harmonization of authorization procedures and regulations’ to ensure fair procedures and equal distribution of plants (art. 8–10), also with regard to borders to non-member states (art. 18). Secondly, research and regulatory efforts were to improve and build trust in nuclear safety (art. 12), and to speed up ‘the procedure for authorising the construction of nuclear power stations’ (art. 19). Thirdly, the resolution advocated what Science and Technology Studies (STS) have described as ‘technological fixes’ (Oelschlaeger Citation1979). ‘Nuclear parks’, for instance, would reduce risks of transporting nuclear materials, and ‘platforms at sea or underground nuclear power plants’ (art. 14) would enable locating plants away from the population. Technologies of dry cooling would allow for wider options for siting nuclear plants away from water courses (art. 23), a problem on which Euratom already funded research (European Commission Citation1974b, 2). Fourthly, the resolution demanded informing the public. The goal of such information was to convince citizens of the indispensability of nuclear energy: people ‘must in all cases be given a clear understanding of the alternatives, which entail an impoverishment of the quality of life’ (art. 16). Finally, the resolution advocated improving the legal bases for citizen participation: member states were encouraged to ‘draft legislation, in so far as it does not already exist, that will enable citizens’ associations and environmental organizations to use constitutional means in pressing their claims’ (art. 20). This was a very ambitious demand, as the rules of ‘standing’ were rather restrictive in many EC/EU member states (Krämer Citation2018), unlike in the United States, where some NGOs strongly relied on litigation (Sandbach Citation1978, 108). This resolution induced the European Commission to propose legislation regarding consultation between member states about nuclear sites at intra-European borders (European Commission Citation1977), which however eventually failed to win the necessary unanimous member state support.

On 13 January 1976, the resolution was debated and voted upon in the EP plenary. In line with constructivist assumptions in the literature on the EP, we can interpret the debate as performative action (Roos Citation2020; Krumrey Citation2018). The parliamentary debate primarily served to explain, justify and promote the initiative taken by the EP, and addressed the Commission, who were represented by the Commissioner responsible for Energy and Taxation, the Belgian Socialist Henri Simonet. Within the EC, the EP plenary was an important forum for the exchange between institutions, and served as an (albeit very limited) proxy for a European public sphere (Meyer Citation2020, Citation2011, Citation2010).

2.3. The speakers

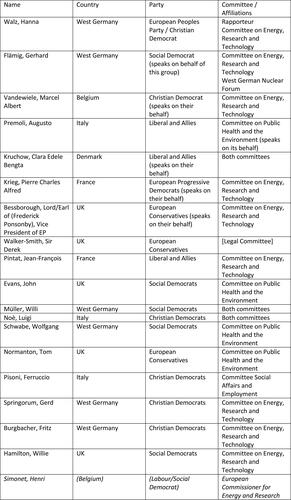

The eighteen MEPs − 16 men and two women – speaking in the plenary debate on 13 January 1976 represented different party groups – Conservatives, Liberals and Socialists – and the two committees involved in the making of the report, the Research and Energy one – in the lead – and that for Public Health and the Environment contributing. Only one of the speakers (Derek Walter-Smith) was not from one of these two committees, but from the EP’s Legal Committee (Meyer forthcoming Citation2022). West German MEPs were most numerous in the debate, accounting for six speakers. Five came from the UK, three from Italy, two from France, and one each from Belgium and Denmark. In terms of party politics, centre-left and centre-right parties held roughly equal weight. From right to left, there were two British conservatives, six Christian democrats, one French Progressive Democrat, three liberals and five social democrats. Various members of the Energy Committee were closely attached to different energy sectors. For instance, Social Democrat Gerhard Flämig held a leading position in the West German Nuclear Forum (Deutsches Atomforum) (NN Citation2002; Spiegel Citation1993), the main nuclear industry lobby. The following table () provides an overview of the speakers and their various attachments.

3. Visions of (European) futures: conceptualising transitions and sustainability

Energy transition and sustainability are highly normative and elusive ‘sponge words’ (Hempel Citation2012, 68), and they both involve references to the future. For analytical purposes, they require some conceptual clarification.

3.1. Transition

Very basically, the ‘idea of transition assumes a movement from one state to another, from a place of departure to one of arrival’, where the place of arrival is often part of a vision of a ‘desirable future’ (Sarrica et al. Citation2016, 1). Energy researchers have emphasised various aspects, such as stages, speed, and also factors conducive – or not – to such transitions, as well as its – often unintended – consequences (Geels et al. Citation2017; Hirsh and Jones Citation2014; Sovacool Citation2016; Smil Citation2016; Sovacool, Hess, and Cantoni Citation2021; Sovacool et al. Citation2021; Araújo Citation2014). Researchers have analysed how political actors, policy communities, scientists and social movements have sought to influence energy transitions, by manufacturing visions of desirable futures, through projections, models, forecasts and scenarios (Aykut Citation2019; Shaev Citation2021). In all of these definitions, the core criterion is the change, and the outright replacement of the main source of energy by another (Sovacool Citation2016, 203). At the political level, this assumption makes the argument for the indispensability of a transition all the more powerful. Historically, however, energy sources have usually complemented rather than supplanted each other (Hasenöhrl and Meyer Citation2020), and some energy researchers have used this observation to attenuate optimistic hopes of a speedy sustainability transition (Smil Citation2016). Already in the 1970s, hopes for a rapid replacement of imported oil by nuclear power proved unrealistic, while ideas for a transition to sources beyond oil and nuclear gave rise to controversy (Lovins Citation1976, 75; Aykut Citation2019; Krause, Bossel, and Müller-Reißmann Citation1980). Nevertheless, most European policymakers in the mid-1970s shared the view that a transition towards new energy sources for the future was necessary. Their ideas about the future involved notions of inevitable progress, the obligation to plan for the future, or anticipation of future characterised by risks – acceptable or not (Graf and Herzog Citation2016, 512). In this sense, the situation was not dissimilar to current energy transitions.

3.2. Sustainability

Sustainability is an old concept from enlightenment forestry, stipulating that no more wood should be used than is growing back in a given period (Warde Citation2011). The term has had a second, more important career as a political concept from the late 20th century onwards (Seefried Citation2021). In 1987, the World Commission on Sustainable Development, the so-called Brundtland Commission, famously defined that making ‘development sustainable’ meant ‘to ensure that it meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (Brundtland Commission Citation1987, 16). In this political document, such future orientation went hand in hand with more ‘Promethean’ hopes or ‘Cornucopian’ technological optimism (Sturup and Low Citation2019, 15; Dryzek Citation2005, 51–71), global justice concerns and a call for ‘effective citizen participation in decision making’ (European Commission Citation1977, 16), reflecting normative principles discussed in Europe already in the 1970s (Nelkin and Pollak Citation1977).

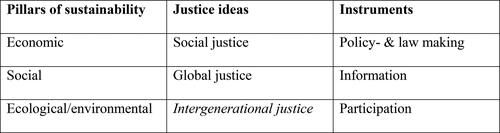

Seeking to make sustainability fruitful as an analytical concept (Sturup and Low Citation2019, 11), researchers have emphasised three components. First, sustainability focuses on three ‘pillars’ relevant for human welfare, namely ‘ecological integrity, social equity and economic vitality’ (Hempel Citation2012, 67; Sarrica et al. Citation2016, 1). Secondly, sustainability involves ideas about justice – not only presently in terms of social justice within societies, and global justice between developed and developing countries in particular, but also intergenerational justice. Sustainability requires – and this is its main innovative aspect – considering the interests of future generations in current decision-making (Hempel Citation2012, 67). Thirdly, as instruments to achieve all this, sustainability requires providing citizens with adequate information and opportunities for participation in policy and law making. The notion of sustainability has effectively served as an appeal to policymakers to make appropriate rules. The following table () provides an overview of the operationalisation of the concept of sustainability.

In the analysis below, these aspects of sustainability will be applied to the EP debate, accessed in its published English translation (European Parliament Citation1976a). From a social constructivist perspective, the debate will be examined as a discourse, i.e., a ‘specific ensemble of ideas, concepts and categorizations that are produced, reproduced and transformed in a particular set of practices’, and which are important because they give ‘meaning’ to ‘physical and social realities’, and thus influence the politics of energy transitions (Hajer Citation1997, 44). These ‘ensembles of ideas’ are examined through a qualitative contents analysis (Mayring Citation2014) focusing on patterns of arguments in an inductive manner, in a procedure that is sensitive to political and historical context (Dimitriou and Field Citation2019).

4. Debating nuclear megaproject siting in the European Parliament

Sustainability arguments will be examined in the following regarding what are the three main themes of the debate on the ‘Community policy on the siting of nuclear power stations taking into account their acceptability for the population’. The first part analyses the justification of an energy transition towards nuclear more generally. The second part addresses MEP’s pleas for political and legal solutions to improve the ‘acceptability for the population’, via a European siting policy – in order to facilitate this transition. These arguments are informed by older visions of ensuring prosperity and peace for the future through nuclear technology and European integration (Curli Citation2017). The third section discusses demands for information and participation that had become more prominent in the course of the 1970s (Nelkin and Pollak Citation1977). The call for information and participation reflects key normative assumptions implicit in sustainability arguments: justice and equity in sustainability transitions can hardly be achieved without democracy and participation (Sovacool, Hess, and Cantoni Citation2021).

4.1. Justifying the transition to nuclear power: indispensable, safe and sustainable?

Economic and social benefits of a transition to nuclear energy in the face of ever-growing energy consumption reigned supreme in MEPs’ statements in the January 1976 debate. Growth and prosperity were key goals; hence most MEPs considered the expansion of nuclear power indispensable to ensure energy security for a growing economy. Visions of the future involved the expectation of continuous growth of energy consumption. Consequently, for instance the Liberal Italian MEP Augusto Premoli anticipated the ‘inevitability of the growth’ of nuclear energy use (European Parliament Citation1976a, 42). This, he presented as an unquestionable fact. Rapporteur Waltz underscored emphatically that ‘in the foreseeable future’, nuclear power would need to constitute part of ‘a vital global energy policy – necessary almost to our survival’ (European Parliament Citation1976a, 36).

In the wake of the oil crisis and the Club of Rome report on the ‘Limits to Growth’ (Meadows et al. Citation1972) nuclear power’s contribution to reducing the dependence on imported oil was an important socio-economic argument, with an ecological tinge. In the face of dwindling ‘fossil energy resources’, and growing energy consumption, only nuclear promised sufficient energy ‘in the long term’, ‘in adequate quantities and under reliable and more favourable price conditions’, Walz argued (European Parliament Citation1976a, 36). As Walz and many of her fellow MEPs assumed a fixed ratio between energy consumption and growth, she warned that not building nuclear power plants would mean ‘unemployment […] on an unprecedented scale’ (European Parliament Citation1976a, 36). The spectre of socio-economic hardship was thus mobilised to defend the transition to nuclear energy.

The British conservative MEP Tom Normanton argued that policymakers had a ‘responsibility’ to prepare and plan for the future, in order not ‘to stand indicted by future generations for failing to make provisions for their future energy needs’ (European Parliament Citation1976a, 59). Unlike most environmental arguments, this socio-economic intergenerational justice argument referred to a short-to-medium-term future. When planning for the future, non-nuclear alternative solutions, such as energy savings or the return to ‘more traditional forms of energy utilisation’ seemed inadequate to Normanton, as well as to many of his fellow MEPs. This reflects widely held contemporary assumptions about progress that led to the rejection of e.g., wind power, which was routinely viewed as belonging to the past (Presas I Puig and Meyer Citation2021, 93). At the same time, ‘new substitute energy sources’ appeared to offer solutions only in a more distant future, if ever. These sources, ‘such as solar, wind energy, or geothermal heat’, ‘wave power’ or ‘thermo-nuclear fusion’, still required much development work, various MEPs argued (European Parliament Citation1976a, 37, 44, 54). Hence, for at least the coming 25 years, nuclear power would be the only option to close the ‘energy gap’, Walz maintained, rejecting alternative energy sources as ‘illusions’ (European Parliament Citation1976a, 37). Other MEPs, such as Premoli, at least mentioned ‘Dutch natural gas’ and North Sea oil as alternatives to imported oil, sources Denmark for instance relied on after giving up nuclear plans (Meyer Citation2019).

For a long time, the promoters of nuclear power have represented nuclear fission as an environmentally friendly source of energy (Espluga et al. Citation2021, 156). Hence, it is not surprising that environmental arguments were mobilised in favour of nuclear energy. Rapporteur Walz described nuclear as the ‘least harmful to the environment’, and emphasised its role for the protection of scarce and precious natural resources (European Parliament Citation1976a, 36). Similarly, the Italian Christian Democrat Ferruccio Pisoni presented nuclear as the ‘cleanest available’ energy source (European Parliament Citation1976a, 60). He and others favourably compared nuclear energy’s apparent cleanliness to the ‘environmental’ and social costs and risks involved in other forms of energy production and use, such as dam building or coal mining, as well as air pollution from coal and petrol combustion (European Parliament Citation1976a, 54, 8, 60)

Finally, Walz defended the transition to nuclear power by reference to social and global justice: ‘Without an energy source of this kind, […] jobs will not be secure, while the developing countries will not be able to count on greater assistance’ (European Parliament Citation1976a, 36). Similarly, Pisoni emphatically argued that ‘sufficient low cost energy’ from nuclear was a necessity to combat ‘hunger and thirst’ and ‘poverty’ ‘throughout the world’ (European Parliament Citation1976a, 60), reflecting an argument made by pronuclear campaigns and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) since the 1950s (Hamblin Citation2021).

Such claims did not go unchallenged. British Labour MEP Hamilton – a miner’s son, maverick in British politics, critic of the monarchy, but a pro-European (Roth Citation2000) – questioned the promises of nuclear energy for global justice in the fight against poverty in ‘underdeveloped countries’. He criticised the capitalist drive of ‘big companies’ that were highly interested in exporting nuclear technology. Such exports would accelerate the spread of plutonium and aggravate proliferation risks (European Parliament Citation1976a, 63–4). Hamilton thus highlighted an issue that was increasingly problematised by contemporary antinuclear movements, while many national governments supported their respective industries’ export efforts (Romberg Citation2020; Bandarra Citation2021).

Nuclear risks hardly featured in most MEPs’ statements, or they were downplayed: ‘We cannot all go back to riding about on bicycles, nor can we live in an environment devoid of risk’. Like Pisoni (European Parliament Citation1976a, 60), almost all MEPs considered nuclear energy sufficiently safe and only posing the usual, accepted risks of the modern world. Many MEPs highlighted the apparently impeccable safety standards and procedures of nuclear industry – as opposed to the traditionally weak safety record of coal-mining, for instance (European Parliament Citation1976a, 45, 54, 7–8, 60). Pisoni explicitly refuted concerns about the risks of radioactivity. Even after a massive expansion of nuclear power, radiation was to remain far below the permissible levels (European Parliament Citation1976a, 61).

Again, Hamilton challenged such views. Nuclear risks were ‘in no way comparable’ to other industry risks. Without using the term, Hamilton questioned the sustainability of nuclear energy on the grounds of nuclear waste, and its long-term impact on future generations. He thus raised the issue of intergenerational justice, while most MEPs like the German Christian Democrat Gerd Springorum expressed Promethean ‘hope’ of future technological fixes: ‘many possible methods will be found’ (European Parliament Citation1976a, 61).

In their advocacy of the transition to nuclear energy, MEPs mobilised various sustainability arguments, most of them relating to socio-economic but at times also to environmental concerns. Intergenerational justice arguments also mattered, on both sides of the debate, interestingly enough.

In the face of the critique of nuclear power, MEPs advocated European policy and law-making – and improved participation and information as instruments to defuse the conflict.

4.2. Europe as a solution: a European siting policy to improve acceptance

As good Europeans, almost all MEPs – with the exception of Hamilton, who from a British perspective did not believe that European legislation would make a difference – agreed with the rapporteur that European Community policy and regulatory measures would help to improve public acceptance of the transition to nuclear energy. The harmonisation of safety standards, of standards for public information and consultation, and a coordinated siting policy for a better distribution of nuclear plants in Europe would help defuse the conflict. Facing national plans for ever larger numbers of nuclear plants, MEPs considered it important to coordinate siting on a European scale, thus limiting the accumulation of certain environmental and socio-economic impacts. Transnational consultation was to become obligatory for plants near international borders. The Belgian Christian democrat Marcel Albert Vandewiele provided an example: ‘two power stations are to be built on either side of the frontier between Luxembourg and Germany at a distance of a few kilometres from each other on the Moselle’ (European Parliament Citation1976a, 41).Footnote2

For all their European ambition, most of the MEPs considered the independent European agency proposed by Tindemans impossible to achieve, considering the differences in local conditions, planning rules and procedures between countries (European Parliament Citation1976a, 51).

MEPs controversially discussed somewhat futuristic technological fixes to deal with risks and popular opposition. Building nuclear parks promised to be useful to minimize the risks relating to the transport of nuclear fuel and waste. However, some MEPs warned that concentrating large-scale energy production in one place would create new risks: it could compromise the resilience of electricity networks and would accumulate risks in cases of failure or military attack. Similarly, views on the feasibility and costs of placing nuclear plants underground or on artificial islands at sea differed. While some MEPs somewhat idealistically argued that the expected benefits in terms of safety and acceptability would be worth the effort and additional investment (European Parliament Citation1976a, 56, 8), an MEP more familiar with the issue, nuclear lobbyist and Social Democratic West German MEP Gerhard Flämig, underlined that such plants would be prohibitively expensive. Their locations would be uneconomically far away from centres of consumption. Moreover such plants would create all kinds of new technical problems and technical and environmental risks regarding ground- and seawater (European Parliament Citation1976a, 39).

4.3. Acceptance in democracy: the ambiguous role of information and participation

The debate about the role of participation and information as instruments to obtain public acceptance for the transition to nuclear power was characterised by ambiguity. On the one hand, the norms of democracy – constitutive of the self-understanding of the MEPs and the project of European integration (Rittberger Citation2007) – required participation in decisions about nuclear megaprojects and their siting. As Liberal Italian MEP Augusto Premoli argued: ‘In the pluralist democratic systems which we enjoy in the Community countries, it is unthinkable to impose on a particular population group the need to live near nuclear power stations’ (European Parliament Citation1976a, 42).

At the same time, in line with the what STS researchers have described as the ‘knowledge deficit model’ (Simis et al. Citation2016), many MEPs claimed that the critique of nuclear energy was based on a lack of knowledge and reason. Thus, they felt they did not have to take the critics of nuclear power and their critique seriously. ‘A well-informed public will not wish to oppose objectively justified needs’ the German Social democratic MEP Willi Müller aptly summarised this assumption that prevented any attempts at serious engagement with the critics right from the start. Similarly, the Italian MEP Luigi Noè argued that ‘participation is desirable’ but maintained that ‘an adequate level of knowledge’ was a precondition for ‘participation’. According to him, those working in nuclear establishments ‘familiar with its problems’ (European Parliament Citation1976a, 57), were the most reliable in providing information. That insider views might be one-sided and shaped by interests, as nuclear critics tended to argue, Noè did not problematise.

Based on such views about a lack of public knowledge, most MEPs stressed the need for more public information, advocating a ‘a rational and complete information policy’ (European Parliament Citation1976a, 55), as MEP Müller argued. A number of national governments in Europe already pursued information campaigns along these lines (Nelkin and Pollak Citation1977; Meyer Citation2019, 94–9; Popp and Lang Citation1977), to debate with but ultimately to convince citizens of the benefits of nuclear power. Rapporteur Walz demanded ‘information campaigns, at national and Community levels’, in order ‘to bring the importance of this technology home to the general public’ (European Parliament Citation1976a, 37). Similar to Tindemans, Walz stressed the role the EC should have in such an information campaign, and MEP Premoli explained the underlying rationale, based on federalist idealism: citizens would consider the European Commission a much more credible and independent source of information than national governments (European Parliament Citation1976a, 42).

British but also non-British MEPs – such as the Danish Liberal Edele Kruchow – presented the British authorities’ information and public participation techniquesFootnote3 as a model to follow. British practice was associated with the absence of protest and general support of nuclear energy (European Parliament Citation1976a, 44, 51). Again, only MEP Hamilton questioned this assessment. Unlike the other MEPs who suggested that more information would convince them of the benefits of nuclear power, Hamilton argued that there was a dearth of information on nuclear risks among common people in the UK (European Parliament Citation1976a, 63). He thus turned the conventional argument on its head, claiming instead that at least in the UK, ignorance contributed to tacit acceptance.

Many MEPs emphasised the need for ‘rational’ information, suggesting that critics were simply driven by emotions: ‘the less knowledge they have on the subject, the more their passions are aroused’, as for instance, MEP John Evans put it (European Parliament Citation1976a, 53). Such dismissive claims about the ‘emotional irrationality’ (European Parliament Citation1976a, 64) of nuclear critics, attributing their opposition to a psychological condition, were a recurrent pattern of argument not only in the EP. As a strategy to medicalise and delegitimise the critique of nuclear power, it has been part of pro-nuclear arguments internationally since the 1950s (Rucht Citation1980, 79; Hamblin Citation2006, 736). In the EP plenary, only nuclear critic Hamilton rejected such insinuations, holding that concerns regarding nuclear power were in fact shared by ‘highly qualified scientists, highly qualified technologists’ (European Parliament Citation1976a, 64).

In many ways, most MEPs apparently viewed information and participation merely as instruments to achieve acceptance, rather than a serious commitment to the norms of democracy or ‘sustainability’.

5. Conclusions

What can we learn from these conflicts and debates for the ongoing ‘sustainability transition’ and the megaprojects it involves? First, since energy planning is a long-term activity, planning decisions on energy megaprojects taken in the 1970s have lasting impacts on the structure of European energy systems. Path dependencies and sunk costs make change difficult (van der Vleuten and Raven Citation2006; van der Vleuten and Högselius Citation2012). Thus, past visions and expectations about future energy needs (Ehrhardt Citation2012), and past narratives and controversies about different energy sources, their risks and promises, continue to influence our present energy infrastructure (Häfner Citation2019), and attempts to deal with the lasting legacy of nuclear waste (Brunnengräber and Di Nucci Citation2019; Kasperski and Storm Citation2020) – another important heritage of those past decisions.

Secondly, some 45 years after the debates analysed above, nuclear power and other energy megaprojects still involve problems of public acceptance. Strikingly, the arguments have hardly changed: The massive growth of nuclear energy megaprojects in the 1970s’ transition to nuclear power was justified by what I analysed as ‘sustainability’ arguments avant la lettre, namely safeguarding the environment, social and economic needs, with a view to the future and global justice. In the face of the oil crisis, perceived as a crisis of energy security, policymakers’ time horizons narrowed. As in many of the crises thereafter, short-term socio-economic concerns outweighed environmental ones. Existing development paths and technologies – ideas of progress and modernity, rather than ‘return to riding bicycles’ as the epitome of a yesterday’s world (Limmer and Zumbrägel Citation2020) – informed expectations about the future and thus the rationale of action. And the Promethean belief in future technological fixes for the externalities of current technologies, such as nuclear waste, remains an attractive political argument in energy debates, lately revived by the advocates of Small Modular Reactors (Kaijser et al. Citation2021, 292–5).

The European federalist idealism displayed by the MEPs advocating European solutions to the acceptance problem of a transition considered indispensable feels a bit outdated. However, given the level of integration today, European (Union) solutions have become standard instruments in responding to European crises (Anderson Citation2021). The public controversy in early 2022 on the European Commission’s taxonomy (European Union Citation2020) of gas and nuclear as ‘sustainable’ sources of energy further illustrates the continued relevance of the European Union in energy policy (Economist Citation2022).

With regard to public information and participation, most MEPs speaking in 1976 found it difficult to accept the legitimacy and seriousness of opposing views. In the EP, this majority view changed over time as the critique of nuclear power became more of a mainstream position in the 1980s. However, building trust through open-ended and honest public engagement (Lehtonen, Cotton, and Kasperski Citation2021), without representing the other side as purely emotional, remains a problem in particular of the nuclear sector, as an expert study commissioned by Euratom after Fukushima highlighted (European Commission Citation2014). This is a lesson that many proponents of nuclear, but also those of other megaprojects, convinced of the benefits of their projects, find difficult to learn.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Edele Kruchow refused to vote in favour of the resolution’s articles that considered nuclear energy necessary (European Parliament Citation1976a, 43–4); this echoed the debate in Denmark where eventually in September 1976 government decided not to authorise nuclear plants until the waste issue was resolved (Meyer Citation2019, 84).

2 Ironically, neither of these two plants was built, but a third plant, Cattenom, with four reactors, upstream in France (Tauer Citation2012).

3 Two of the major public debates on the expansion of the Windscale reprocessing plant took place in December 1975 and January 1976. These events probably raised MEPs’ attention for British activities (Bolter Citation1979), too.

References

- Anderson, Jeffrey J. 2021. “A Series of Unfortunate Events: Crisis Response and the European Union After 2008.” In The Palgrave Handbook of EU Crises, edited by Marianne Riddervold, Jarle Trondal and Akasemi Newsome, 765–789. Cham: Palgrave.

- Araújo, Kathleen. 2014. “The Emerging Field of Energy Transitions: Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities.” Energy Research & Social Science 1: 112–121.

- Aykut, Stefan Cihan. 2019. “Reassembling Energy Policy: Models, Forecasts, and Policy Change in Germany and France.” Science & Technology Studies 32 (4): 13–35.

- Bandarra, Leonardo. 2021. “From Bonn with Love: West German Interests in the 1975 Nuclear Agreement with Brazil.” Cold War History 21 (3): 337–355.

- Bolter, Harold E.. 1979. “The Windscale Inquiry's Contribution to Public Understanding.” In Acceptance of Nuclear Power. ENC '79 – Foratom VII, Hamburg May 6–May 11, 1979, edited by ENC and Foratom, 50–57. Essen: Vulkan.

- Bösch, Frank, and Rüdiger Graf. 2014. “Reacting to Anticipations: Energy Crises and Energy Policy in the 1970s. An Introduction.” Historical Social Research 39 (4): 7–21.

- Brundtland Commission. 1987. "Report of the World commission on environment and development: Our common future." https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf.

- Brunnengräber, Achim, and Maria Rosaria Di Nucci. eds. 2019. Conflicts, Participation and Acceptability in Nuclear Waste Governance: An International Comparison Volume III. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Curli, Barbara. 2017. “Nuclear Europe: technoscientific Modernity and European Integration in Euratom’s Early Discourse.” In Discourses and Counter-Discourses on Europe: From the Enlightenment to the EU, edited by Manuela Ceretta and Barbara Curli, 99–114. London: Routledge.

- Dimitriou, Harry T., and Brian G. Field. 2019. “Clarifying Terms, Concepts and Contexts.” Journal of Mega Infrastructure & Sustainable Development 1 (1): 1–7.

- Dryzek, John S. 2005. The Politics of the Earth. Environmentalist Discourses. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Economist. 2022. “Nein, Danke! Why Germans Remain so Jittery about Nuclear Power.” The Economist (8th January) 182.

- Edberg, Karin, and Ekaterina Tarasova. 2016. “Phasing out or Phasing in: Framing the Role of Nuclear Power in the Swedish Energy Transition.” Energy Research & Social Science 13: 170–179.

- Ehrhardt, Hendrik. 2012. “Energiebedarfsprognosen. Kontinuität und Wandel energiewirtschaftlicher Problemlagen in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren.” In Energie in der Modernen Gesellschaft. Zeithistorische Perspektiven, edited by Hendrik Ehrhardt and Thomas Kroll, 193–222. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Ekberg, Kristoffer, and Martin Hultman. 2021. “A Question of Utter Importance: The Early History of Climate Change and Energy Policy in Sweden, 1974–1983.” Environment and History online fast track: 1–23. doi: https://doi.org/10.3197/096734021X16245313030028.

- Espluga, Josep, Wilfried Konrad, Ann Enander, Beatriz Medina, Ana Prades, and Pieter Cools. 2021. “Risky or Beneficial? Exploring Perceptions of Nuclear Energy over Time in a Cross-Country Perspective.” In Engaging the Atom. The History of Nuclear Energy and Society in Europe from the 1950s to the Present, edited by Arne Kaijser, Markku Lehtonen, Jan-Henrik Meyer and Mar Rubio-Varas, 147–169. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press.

- Euratom. 1957. “Treaty Establishing the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom), Signed 17 April 1957.” Eur-Lex (document 11957A/TXT). http://data.europa.eu/eli/treaty/euratom/sign

- European Commission. 2014. Benefits and Limitations of Nuclear Fission for a Low-Carbon Economy. 2012 Interdisciplinary Study Synthesis Report and Compilation of the Experts’ Reports: 2013 Symposium Agenda and Speakers’ Symposium Speeches Delivered on 26–27 February 2013. Brussels: Publications Office of the European Union.

- European Commission. 1974a. “Nuclear Energy: Promoting the Use of Nuclear Energy: Action Programme Proposed by the Commission, 8 February 1974.” Bulletin of the European Communities 7 (2): 60–61.

- European Commission. 1977. “Proposal for a Council Regulation concerning the Introduction of a Community Consultation Procedure in Respect of Power Stations Likely to Affect the Territory of Another Member State (Submitted by the Commission to the Council on 13 December 1976), COM/76/576FINAL.” Official Journal of the EC 20: 3–5.

- European Parliament. 1975. “Debate on Oral Questions No. 9 by Kurt Härzschel "Safety of Atomic Power Stations in the Community" and No. 10 by Luigi Noè "Construction of Nuclear Power Stations", 9 April 1975.” Official Journal of the European Communities, Annex: Proceedings of the European Parliament, 18 (189), 74–76.

- European Parliament. 1976a. “Debates on "Community Policy on the Siting of Nuclear Power Stations” (13 January 1976)." Official Journal of the European Communities, Annex: Debates of the European Parliament 19 (198), 36–66.

- European Parliament. 1976b. “Resolution on the Conditions for a Community Policy on the Siting of Nuclear Power Stations Taking account of Their Acceptability for the Population.” Official Journal of the European Communities (OJEC) 19 (C28): 12–14.

- European Union. 2020. “Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 June 2020 on the Establishment of a Framework to Facilitate Sustainable Investment, and Amending Regulation (EU) 2019/2088.” Official Journal of the European Union 63 (L 198): 13–43.

- European Commission. 1974b. “The Commission Finalises Energy Research Programme, SEC (74) 2592, Brusssels, July 1974.” Information Memo (P-48): 1–3.

- Geels, Frank W., Benjamin K. Sovacool, Tim Schwanen, and Steve Sorrell. 2017. “The Socio-Technical Dynamics of Low-Carbon Transitions.” Joule 1 (3): 463–479.

- Geyer, Martin H. 2016. “Die neue Wirklichkeit von Sicherheit und Risiken. Wiewir mit dystopischen, utopischen und technokratischen Diagnosen von Sicherheit zu Leben gelernt jaben.” In Die neue Wirklichkeit. Semantische Neuvermessungen und Politik seit den 1970er Jahren, edited by Ariane Leendertz and Wencke Meteling, 281–315. Frankfurt: Campus.

- Graf, Rüdiger, and Benjamin Herzog. 2016. “Von der Geschichte der Zukunftsvorstellungen zur Geschichte ihrer Generierung.” Geschichte und Gesellschaft 42 (3): 497–515.

- Häfner, Daniel. 2019. “Partizipation rückwärts? Zur Aufarbeitung der Konflikte im Bereich der Kernenergie.” In Kursbuch Bürgerbeteiligung #3, edited by Jörg Sommer, 41–57. Berlin: Deutsche Umweltstiftung.

- Hähnel, Paul Lukas. 2020. “Parlamentarier für Europa – Die Vernetzung des Bundestags mit Europäischen interparlamentarischen Körperschaften durch Doppelmandate (1950–1969/70).” Journal of European Integration History 26 (2): 325–344.

- Hajer, Maarten A. 1997. The Politics of Environmental Discourse: Ecological Modernization and the Policy Process. Oxford: Clarendon.

- Hamblin, Jacob Darwin. 2006. “Exorcising Ghosts in the Age of Automation: United Nations Experts and Atoms for Peace.” Technology and Culture 47 (4): 734–756.

- Hamblin, Jacob Darwin. 2021. The Wretched Atom. America's Global Gamble with Peaceful Nuclear Technology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Häni, David. 2018. Kaiseraugst besetzt! Die Bewegung gegen das Atomkraftwerk. Basel: Schwabe Verlag.

- Hasenöhrl, Ute, and Jan-Henrik Meyer. 2020. “The Energy Challenge in Historical Perspective.” Technology and Culture 61 (1): 295–306.

- Hempel, Lamont C. 2012. “Evolving Concepts of Sustainability in Environmental Policy.” In The Oxford Handbook of US Environmental Policy, edited by Michael E. Kraft and Seldon Kaminiecki, 67–92. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hirsh, Richard F., and Christopher F. Jones. 2014. “History's Contributions to Energy Research and Policy.” Energy Research & Social Science 1: 106–111. doi:.

- Högselius, Per, Arne Kaijser, and Erik van der Vleuten. 2016. Europe’s Infrastructure Transition. Economy, War, Nature. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Josephson, Paul R., and Markku Lehtonen. 2021. “International Organizations and the Atom: How Comecon, Euratom, and the OECD Nuclear Energy Agency Developed Societal Engagement in Engaging the Atom.” The History of Nuclear Energy and Society in Europe from the 1950s to the Present, edited by Arne Kaijser, Markku Lehtonen, Jan-Henrik Meyer and Mar Rubio-Varas, 112–144. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press.

- Josephson, Paul R., Jan-Henrik Meyer, and Arne Kaijser. 2021. “Nuclear-Society Relations from the Dawn of the Nuclear Age.” In Engaging the Atom. The History of Nuclear Energy and Society in Europe from the 1950s to the Present, edited by Arne Kaijser, Markku Lehtonen, Jan-Henrik Meyer and Mar Rubio-Varas, 27–51. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press.

- Kaijser, Arne, Markku Lehtonen, Jan-Henrik Meyer, and Mar Rubio-Varas. 2021. “Conclusions: Future Challenges for Nuclear Energy and Society in a Historical Perspective.” In Engaging the Atom. The History of Nuclear Energy and Society in Europe from the 1950s to the Present, edited by Arne Kaijser, Markku Lehtonen, Jan-Henrik Meyer and Mar Rubio-Varas, 279–302. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press.

- Kaijser, Arne, and Jan-Henrik Meyer. 2018. “Siting Nuclear Installations at the Border. Special Issue.” Journal for the History of Environment and Society 3: 1–178.

- Kaijser, Arne, and Meyer. Jan-Henrik 2021. “Nuclear Installations at European Borders: Transboundary Collaboration and Conflict.” In Engaging the Atom. The History of Nuclear Energy and Society in Europe from the 1950s to the Present, edited by Arne Kaijser, Markku Lehtonen, Jan-Henrik Meyer and Mar Rubio-Varas, 254–277. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press.

- Kasperski, Tatiana, and Anna Storm. 2020. “Eternal Care.” Geschichte und Gesellschaft 46 (4): 682–705.

- Kirchhof, Astrid Mignon, and Jan-Henrik Meyer. 2021. “Revealing Risks: European Moments in Nuclear Politics and the Anti-Nuclear Movement.” In Greening Europe. Environmental Protection in the Long Twentieth Century, edited by Anna Katharina Wöbse and Patrick Kupper, 331–361. Berlin: Oldenbourg.

- Krämer, Ludwig. 2018. “Citizens Rights and Administrations' Duties in Environmental Matters: 20 Years of the Aarhus Convention.” Revista Catalana de Dret Ambiental 9 (1): 1–26.

- Krause, Florentin, Hartmut Bossel, and Karl-Friedrich Müller-Reißmann. 1980. “Energie-Wende. Wachstum und Wohlstand ohne Erdöl und Uran.” Ein Alternativ-Bericht des Öko-Instituts, Freiburg: S. Fischer.

- Krumrey, Jacob. 2018. The Symbolic Politics of European Integration: Staging Europe. London: Macmillan.

- Lagendijk, Vincent. 2015. “Europe's Rhine Power: connections, Borders, and Flows.” Water History 8: 23–39.

- Lehtonen, Markku, Matthew Cotton, and Tatiana Kasperski. 2021. “Trust and Mistrust in Radioactive Waste Management: Historical Experience from High- and Low-Trust Contexts.” In Engaging the Atom. The History of Nuclear Energy and Society in Europe from the 1950s to the Present, edited by Arne Kaijser, Markku Lehtonen, Jan-Henrik Meyer and Mar Rubio-Varas, 170–201. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press.

- Leslie, Stuart W., and Joris Mercelis. 2019. “Expo 1958. Nucleus for a New Europe.” In World's Fairs in the Cold War: Science, Technology, and the Culture of Progress, edited by Arthur Molella and Scott Gabriel Knowles, 11–26. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Limmer, Agnes, and Christian Zumbrägel. 2020. “Waterpower Romance: The Cultural Myth of Dying Watermills in German Hydro-Narratives around 1900.” Water History 12 (2): 179–204.

- Lovins, Armory B. 1976. “Energy Strategy. The Road Not Taken.” Foreign Affairs 55 (1): 65–96.

- Mayring, Philipp. 2014. Qualitative Content Analysis: theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution. Klagenfurt: Beltz.

- Meadows, Dennis, Donella Meadows, Erich Zahn, and Peter Milling. 1972. The Limits to Growth. New York: Universe Books.

- Meyer, Jan-Henrik, forthcoming 2022. “The European Parliament and the Constitutionalisation of European Law.” In The History of EU-Law in Transnational and National Perspective, edited by Morten Rasmussen and Bill Davies. Oxford: Hart.

- Meyer, Jan-Henrik. 2010. The European Public Sphere. Media and Transnational Communication in European Integration 1969–1991. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner.

- Meyer, Jan-Henrik. 2011. “Green Activism. The European Parliament's Environmental Committee Promoting a European Environmental Policy in the 1970s.” Journal of European Integration History 17 (1): 73–85.

- Meyer, Jan-Henrik. 2019. "Atomkraft – Nej tak’. How Denmark did not Introduce Commercial Nuclear Power Plants.” In Pathways into and out of Nuclear Power in Western Europe: Austria, Denmark, Federal Republic of Germany, Italy, and Sweden edited by Astrid Mignon Kirchhof, 74–123. Munich: Deutsches Museum.

- Meyer, Jan-Henrik. 2020. “Responding to the European Public? Public Debates, Societal Actors and the Emergence of a European Environmental Policy.” In The Environment and European Public Sphere: Perception, Actors, Policies, edited by Christian Wenkel, Éric Bussière, Anahita Grisoni and Hélène Miard-Delacroix, 221–240. Winwick: White Horse Press.

- Meyer, Jan-Henrik. 2021. “Pushing for a Greener Europe. The European Parliament and Environmental Policy in the 1970s and 1980s.” Journal of European Integration History 27 (1): 57–78.

- Mez, Lutz, and Birger Ollrogge. 1979. Energiediskussion in Europa: Berichte nd Dokumente über die Haltung der Regierungen und Parteien in der Europäischen Gemeinschaft zur Kernenergie, Argumente in der Energiediskussion, 7. Villingen: Neckar-Verlag.

- Milder, Stephen. 2017. Greening Democracy. The Anti-Nuclear Movement and Political Environmentalism in West Germany and Beyond, 1968–1983. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nelkin, Dorothy, and Michael Pollak. 1977. “The Politics of Participation and the Nuclear Debate in Sweden, The Netherlands, and Austria.” Public Policy 25 (3): 334–357.

- Nielsen-Sikora, Jürgen. 2007. “The Ideas of a European Union and a Citizen's Europe: The 1975 Tindemans Report and Its Impact on Today's Europe.” In Beyond the Customs Union: The European Community's Quest for Completion, Deepening and Enlargement, 1969–1975, edited by Jan van der Harst, 377–389. Bruxelles: Bruylant.

- NN. 2002. “Flämig, Gerhard.” In Biographisches Handbuch der Mitglieder des Deutschen Bundestages. 1949–2002; Band 1 A-M, edited by Rudolf Vierhaus, Ludolf Herbst and Bruno Jahn, 216. München: Saur.

- Oberloskamp, Eva. 2020. “Energy and the Environment in Parliamentary Debates in the Federal Republic of Germany, the United Kingdom and France from the 1970s to the 1990s.” In The Environment and European Public Sphere: Perception, Actors, Policies, edited by Christian Wenkel, Éric Bussière, Anahita Grisoni and Hélène Miard, 205–219. Winwick: White Horse Press.

- Oelschlaeger, Max. 1979. “The Myth of the Technological Fix.” The Southwestern Journal of Philosophy 10 (1): 43–53.

- Patel, Kiran Klaus, and Christian Salm. 2021. “The European Parliament during the 1970s and 1980s. An Institution on the Rise? Introduction.” Journal of European Integration History 27 (1): 5–19.

- Pohl, Natalie. 2019. Atomprotest am Oberrhein: Die Auseinandersetzung um den Bau von Atomkraftwerken in Baden und im Elsass (1970–1985). Stuttgart: Steiner.

- Popp, Manfred, and Klaus Lang. 1977. “The Public Discussion about the Peaceful Utilization of Nuclear Energy in the Federal Republic of Germany and the Information and Discussion Campaign of the Federal Government.” In International Conference on Nuclear Power and its Fuel Cycle. Salzburg, Austria, 2–13 May 1977, IAEA-CN-36-81, edited by IAEA, 1–22. Vienna: International Atomic Energy Agency.

- Presas I Puig, Albert, and Jan-Henrik Meyer. 2021. “One Movement or Many? The Diversity of Antinuclear Movements in Europe.” In Engaging the Atom. The History of Nuclear Energy and Society in Europe from the 1950s to the Present, edited by Arne Kaijser, Markku Lehtonen, Jan-Henrik Meyer and Mar Rubio-Varas, 83–111. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press.

- Reitbauer, Magdalena. 2015. “The Origins, Formation, and Development of Euratom.” Zeitgeschichte 42 (5): 299–306.

- Rittberger, Berthold. 2007. Building Europe's Parliament. Oxford: Oxford UP.

- Romberg, Dennis. 2020. Atomgeschäfte: die Nuklearexportpolitik der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 1970–1979. Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh.

- Roos, Mechthild. 2020. “Becoming Europe's Parliament: Europeanization through MEPs' Supranational Activism, 1952–79.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 58 (6): 1413–1432.

- Roth, Andrew. 2000. “Willie Hamilton. MP Who Was an Outspoken Critic of the Royal Family.” The Guardian, 27 January 2000, https://www.theguardian.com/news/2000/jan/27/guardianobituaries.

- Rucht, Dieter. 1980. Von Wyhl nach Gorleben. Bürger gegen Atomprogramm und nukleare Entsorgung. Munich: C.H. Beck.

- Sandbach, Francis. 1978. “A Further Look at the Environment as a Political Issue.” International Journal of Environmental Studies 12 (2): 99–109.

- Sarasin, Philipp. 2021. 1977. Eine kurze Geschichte der Gegenwart. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

- Sarrica, Mauro, Sonia Brondi, Paolo Cottone, and Bruno M. Mazzara. 2016. “One, No One, One Hundred Thousand Energy Transitions in Europe: The Quest for a Cultural Approach.” Energy Research & Social Science 13: 1–14.

- Seefried, Elke. 2021. “Developing Europe: The Formation of Sustainability Concepts and Activities.” In Greening Europe: Environmental Protection in the Long Twentieth Century – A Handbook, edited by Wöbse Anna-Katharina and Kupper Patrick, 389–418. Berlin: De Gruyter Oldenbourg.

- Shaev, Brian. 2021. “Coal and Common Market: Forecasting Crisis in the Early European Parliament.” " In Boom – Crisis – Heritage: King Coal and the Energy Revolutions after 1945, edited by Lars Bluma, Michael Farrenkopf and Torsten Meyer, 71–80. Berlin: De Gruyter Oldenbourg.

- Simis, Molly J., Haley Madden, Michael A. Cacciatore, and Sara K. Yeo. 2016. “The Lure of Rationality: Why Does the Deficit Model Persist in Science Communication?” Public Understanding of Science 25 (4): 400–414.

- Smil, Vaclav. 2016. “Examining Energy Transitions: A Dozen Insights Based on Performance.” Energy Research & Social Science 22: 194–197.

- Sovacool, Benjamin K. 2016. “How Long Will It Take? Conceptualizing the Temporal Dynamics of Energy Transitions.” Energy Research & Social Science 13: 202–215.

- Sovacool, Benjamin K., David J. Hess, and Roberto Cantoni. 2021. “Energy Transitions from the Cradle to the Grave: A Meta-Theoretical Framework Integrating Responsible Innovation, Social Practices, and Energy Justice.” Energy Research & Social Science 75: 102027.

- Sovacool, Benjamin K., Bruno Turnheim, Andrew Hook, Andrea Brock, and Mari Martiskainen. 2021. “Dispossessed by Decarbonisation: Reducing Vulnerability, Injustice, and Inequality in the Lived Experience of Low-Carbon Pathways.” World Development 137: 105116.

- Spiegel. 1993. “Geheimdienste. Unglaublich emsig. Der Generalbundesanwalt ermittelt gegen einen ehemaligen SPD-Bundestagsabgeordneten und Atomexperten, der für die Stasi spioniert haben soll.” Der Spiegel 47 (4): 24.

- Spiering, Menno. 2011. “Atoms for Europe.” In European Identity and the Second World War, edited by Menno Spiering and Michael Wintle, 171–185. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Sturup, Sophie, and Nicholas Low. 2019. “Sustainable Development and Mega Infrastructure: An Overview of the Issues.” Journal of Mega Infrastructure & Sustainable Development 1 (1): 8–26.

- Tauer, Sandra. 2012. “Störfall für die Gute Nachbarschaft?.” Deutsche und Franzosen auf der Suche nach einer Gemeinsamen Energiepolitik (1973-1980). Göttingen: V&R Unipress.

- Tindemans, Leo. 1976. “European Union. Report by Mr. Leo Tindemans, Prime Minister of Belgium, to the European Council. (Commonly Called the Tindemans Report), 29 December 1975.” Bulletin of the European Communities Supplement1 (76): 1–76.

- Tompkins, Andrew. 2016. Better Active than Radioactive! anti-Nuclear Protests in 1970s France and West Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Van der Vleuten, Erik , and Per Högselius. 2012. “Resisting Change? The Transnational Dynamics of European Energy Regimes.” In Governing the Energy Transition. Reality, Illusion or Necessity?, edited by Geert Verbong and Derk Lorbach, 75–100. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Van der Vleuten, Erik, and Rob Raven. 2006. “Lock-in and Change: Distributed Generation in Denmark in a Long-Term Perspective.” Energy Policy 34 (18): 3739–3748.

- Walz, Hanna. 1975. “Report drawn up on Behalf of the Committee on Energy, Research and Technology of the European Parliament on the Conditions for a Community Policy on the Siting of Nuclear Power Stations Taking account of Their Acceptability for the Population, Doc. 392/75, 26 November 1975.” European Parliament Working Documents 1975/76 (PE 40.985/fin.): 1–38.

- Warde, Paul. 2011. “The Invention of Sustainability.” Modern Intellectual History 8 (1): 153–170.