OCCUPATIONAL APPLICATIONS

Ergonomics knowledge transfer is one of the potential challenges in organizations in industrially developing countries. For the effective implementation of a systemic ergonomics knowledge transfer process, the involvement of all organizational levels is necessary, especially workers, with the facilitation of ergonomics expert. Applying a participatory ergonomics process with different participatory approaches for participant involvement – including a top-down approach, as a pushing tactic for intentional learning, and a bottom-up approach, as a pulling tactic for voluntary learning – can play a key role in the transfer and application of practical ergonomics knowledge. The results of this study showed that active involvement of all organizational levels, especially workers through action learning and a learner-centered approach, and using the ILO ergonomic checkpoints, could improve participant learning of ergonomics principles. In addition, this process can lead to improved competence of personnel in identifying problems and providing and implementing solutions to improve working conditions, especially low-cost solutions. Accordingly, if this process continues as a constant improvement process through multiple learning cycles, it can improve participation and ergonomics culture and achieve additional practical benefits of the Human Factors/Ergonomics.

TECHNICAL ABSTRACT

Background: Implementing ergonomics principles in workplaces requires good knowledge transfer with the participation of professionals, workers, and managers.

Purpose: This study aimed to investigate practical ergonomics knowledge transfer to support the participatory ergonomics process that could lead problem identification and the implementation and development of feasible and low-cost solutions.

Methods: This was action research on the type of intervention and conducted in four phases. Accordingly, 106 participants from different organizational levels of a manufacturing company, facilitated by an ergonomist by forming 14 action groups, were involved in practical ergonomics knowledge transfer to identify and solve problems of work divisions. Participant reflections were obtained through interviews and field notes.

Results: The results contributed to the presentation of 145 solutions to improve working conditions by the action groups. Most solutions were low-cost and 57.5% were implemented. The interviews showed the development of a participation culture, learning and institutionalizing ergonomics principles in practice, and improving competence in identifying problems and implementing solutions.

Conclusions: The key findings were achieved by the participatory ergonomics intervention approach through different tactics of participant engagement, including a pushing tactic for intentional learning and a pulling tactic for voluntary learning, which resulted in the improvement of working conditions and promotion of a participatory culture.

1. Introduction

Participatory approaches are among successful approaches that improve working conditions, productivity, and make good changes via the participation of individuals involved in the change process (Vink et al., Citation2008). However, studies on the application of ergonomics within organizations of Industrially Developing Countries (IDCs) show that many organizations suffer from the lack of an appropriate human-centered and participatory approach that, consequently, creates adverse impact on the individuals and on organization performance (Helali, Citation2008; Shahnavaz, Citation2002). Compared to developed countries, many organizations in IDCs face more problems in their work systems, such as poor working conditions, low income, health problems, and low productivity (Scott, Citation2009). In these countries, the lack of sufficient awareness and knowledge about the potential benefits of ergonomics, as well as the limited number of specialists are the main reasons for a low application rate of this science (Scott et al., Citation2010).

Knowledge is the main source to achieve such goals as safety, health, and ergonomics management (Sherehiy & Karwowski, Citation2006); however, ergonomics knowledge transfer is a potential challenge in IDC organizations (Helali, Citation2009a; Citation2008). Industries in IDCs often do not have the proper tools to quickly acquire knowledge, and therefore knowledge providers do not have the necessary support in knowledge transfer. These situations probably make knowledge recipients suffer from a lack of incentives to understand the concepts of knowledge transfer and an inability to find functional difficulties in practical knowledge transfer (Huang et al., Citation2008). Researchers have argued that, to achieve more effective ergonomics interventions, it is necessary to apply appropriate strategies to enable knowledge transfer and emphasize its impact (Dagenais et al., Citation2017).

Neumann et al. (Citation2012) stated that due to the gap between research and practice in ergonomics research and intervention, ergonomists need to consider appropriate methodologies, such as action research in the transfer and application of ergonomics knowledge in close collaboration with researchers and stakeholders. For this reason, implementing ergonomics principles in workplaces requires a proper knowledge transfer, with the participation of professionals, workers, and managers (Boatca et al., Citation2018). Studies on ergonomics knowledge transfer have indicated that using a participatory ergonomics process with an action research methodology, especially participatory action research, is key to improving work system (Helali, Citation2009a; Citation2008) and that it reduces musculoskeletal disorders in the workplace (Rosecrance & Cook, Citation2000).

Knowledge transfer strategies can be explained by participatory ergonomics and can be effective in solving the safety, health, and ergonomics problems according to the performance of the work teams (Kramer & Wells, Citation2005). Haines and Wilson (Citation1998) emphasized that participatory ergonomics involves people in planning and controlling a significant amount of their work activities, with sufficient knowledge and the ability to affect processes and outputs to achieve the goals. The effectiveness of participatory ergonomics intervention in different fields such as improving physical and mental health (Capodaglio, Citation2022; Vink et al., Citation1995), reducing stress at work (Kogi et al., Citation2016; Shojaei et al., Citation2020), empowering individuals to identify and resolve problems in workplaces and job enrichment (Dastranj & Helali, Citation2016), and improving economic and productivity (Tompa et al., Citation2013), are emphasized in different workplaces in developed countries and IDCs (Broday, Citation2021; Burgess-Limerick, Citation2018; Kogi, Citation2012).

Participatory ergonomics with a human-centered approach and bottom-up intervention, which emphasizes the involvement of all levels of the organization, particularly workers, and empowers them with an action learning approach and learning strategies for change, can be helpful in improving quality of life in organizations (Dastranj & Helali, Citation2016; Ingelgård & Norrgren, Citation2001). Moreover, worker participation is a key factor in the development and success of ergonomics interventions (van Eerd et al., Citation2010), as workers have more understanding of their jobs and can provide useful resources (Hess et al., Citation2004), which has a positive effect on job satisfaction and performance by building trust and commitment (Brown, Citation2004).

The participatory ergonomics cycle introduced by Haines and Wilson (Citation1998) presents the principles of the participatory ergonomics used by individuals to get involved in designing and analyzing work-related problems by employing different types of involvement. This is called as the “Participatory Ergonomics Process” (PEP), with a kind of support in developing ergonomics intervention techniques (Helali, Citation2009a; Citation2008). Ergonomists could use different tactics to involve participants in the PEP through “learning by doing”. These tactics can be top-down and bottom-up in an organization, which is called push-pull tactics (Helali, Citation2008). Applying the PEP creates an atmosphere in which participants learn from each other in an appreciative way and can observe improvement in their technical and social skills (Dastranj & Helali, Citation2016). In this regard, it is recommended that appropriate training tools be used, such as different checkpoints of the International Labor Organization (ILO) (ILO, Citation2010) with an action learning approach to improve technical and social skills of participants involved in the PEP (Dastranj & Helali, Citation2016; Helali, Citation2009b; Shojaei et al., Citation2020).

Utilizing ergonomic checkpoints, in a systematic and highly participatory way among workers, with an emphasis on internal capabilities and local resources, can be efficient in developing practical programs to improve working conditions and a human-centered approach (Kawakami & Kogi, Citation2005; Kogi, Citation2012). Also, utilizing ergonomic checkpoints with a participatory approach is effective in identifying and implementing low-cost and easy solutions, especially in organizations in IDCs that face limited resources (Dastranj & Helali, Citation2016; Helali, Citation2009b; Kawakami & Kogi, Citation2005; Kogi et al., Citation2016).

This study investigated practical ergonomics knowledge transfer to support the PEP that could lead to the identification of problems and implementation and development of feasible and low-cost solutions, by using the ergonomic checkpoints in an “appreciative way.” Specifically, by working with people, tools, and company, instead of working on them (Ghaye, Citation2007). Our research question was: How can we apply a practical ergonomics knowledge transfer to support the PEP by using the ergonomic checkpoints in an appreciative way?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The present study was conducted in one of the main departments of a power plant production company. The production department consisted of seven divisions and 142 personnel. Six divisions including 134 people were selected. In compliance with the department managers, production conditions, and the interest of the relevant personnel, 103 people voluntarily participated in this action research study based on convenience and voluntary sampling methods. Three participants participated from the Health, Safety and Environment (HSE) division that included an ergonomist (the first author as a researcher, who was present in the company two days a week), the head of division, and an occupational health expert. They were an internal coordinator and facilitator, but the ergonomist, as the main facilitator, played a key role in the study and ergonomics knowledge transfer.

Participant characteristics are summarized in . Mean age and job tenure were 29.9 and 5.8 years, respectively, and most of the participants had a diploma (65%). Due to the high physical load of jobs in the production department, and the company’s preference for recruiting men with high physical strength, all participating personnel from the operational divisions were men.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of participants.

Organizational characteristics are summarized in . The largest number of participants came from a grinding division (25 persons), and the majority of participants (79%) were workers. Workers worked in two or three working shifts in different divisions, and each working shift had a supervisor.

Table 2. Organizational characteristics of participants.

Following meetings with different organizational levels and explaining the objectives and implementation phases of the study, individuals agreed to voluntarily participate in the study. This study was conducted in coordination with the HSE division and with the consent of senior organizational officials of the studied company. Ethical considerations including the confidentiality of participants’ personal information were followed.

2.2. Material

The Persian version of the ergonomic checkpoints book published by ILO (Citation2010) (Dastranj & Helali, Citation2015; ILO, Citation2010) was utilized in this study. ILO’s ergonomic checkpoints provide practical and easy-to-implement solutions to improve safety, health, and working conditions. It is comprised of a checklist and checkpoints on nine different topics chapters, including materials storage and handling (17 checkpoints), hand tools (14 checkpoints), machine safety (19 checkpoints), workstation design (13 checkpoints), lighting (9 checkpoints), premises (12 checkpoints), hazardous substances and agents (10 checkpoints), welfare facilities (11 checkpoints), and work organization (27 checkpoints).

2.3. Procedures

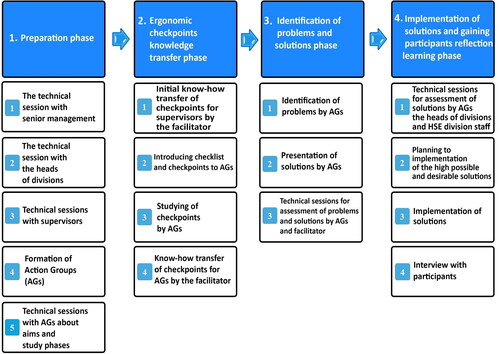

The present action research on the type of intervention was conducted over 2 years and 2 months and with the active involvement of participants from different organizational levels to transfer and apply ergonomic checkpoints knowledge. It was implemented in four phases, as different phases of action research, including planning, acting, observing, and reflecting. It was done according to the action research model reported by Meyer (Citation2000), and data collection was carried out by performing the following different phases ().

Phase 1. Preparation Phase (as Planning Phase)

In this phase, a meeting was held initially about the research objectives with the ergonomist, the head of the HSE division, and the senior management of the operational division. Upon agreement of senior management to start the study, a second session, with the heads of the divisions in the form of four persons as the head of six divisions (), was held on the importance and necessity of the PEP, the objectives of the study, and its implementation phases. Of note, the heads of divisions were responsible for coordinating the personnel within their divisions in the implementation phases and playing supporting roles in assessment and implementing the solutions.

Then, the ergonomist held a technical session with all the supervisors of the divisions (14 persons) about the objectives of the study. With the supervisor of each division, together with the head of the division and the ergonomist, technical sessions were organized (a session per division) on how the Action Groups (AGs) were formed and how the different chapters of the ILO’s ergonomic checkpoints were assigned, according to the conditions in the divisions. In this phase, 14 AGs were formed (each AG included 4 to 9 people), consisting of 98 people from six working divisions in different work shifts. Each AG included a supervisor, who was the coordinator of each division and each work shift, and the workers of the division based on the work shift. To select ergonomic checkpoints chapters for the divisions, at first the ergonomist had a conversation with supervisors and workers on their workplace problems in addition to field observations. Related sessions were also held with the head of the HSE division. Accordingly, for all divisions jointly, all checkpoints of four chapters of the ergonomic checkpoints book were selected, including materials storage and handling, hand tools, machine safety, and workstation design. As needed, two checkpoints of the lighting chapter for the Tooling and Milling division, as well as two checkpoints of the hazardous substances and agents chapter for the Drilling and Grinding division, were also selected. Depending on the working conditions of other divisions, informal conversations were held with AGs on the lighting and hazardous substances and agents checkpoints. Then, independent technical sessions, in the form of discussion and appreciative conversation with the supervisor of each division and AGs in the workplace, were held about the research objectives, the formation of AGs, and implementation phases. For better coordination of AGs to use ergonomic checkpoints, inside each division, each AG was assigned one or two chapters of checkpoints so that all selected chapters would be studied.

Phase 2. Ergonomic Checkpoints’ Knowledge Transfer Phase (as Acting Phase)

After the forming AGs, a technical session (two hours) was held with supervisors to familiarized them with the checklist and the ergonomic checkpoints’ knowledge transfer method. Subsequently, the ergonomist and supervisors held technical sessions within the working divisions, first explaining the checklist and ergonomic checkpoints to the AGs, then providing time for individual study of the checkpoints. In addition, informal sessions were held in the form of AGs and collective discussions and appreciative conversations between the ergonomist and the AGs during different working shifts on selected chapters of ILO ergonomic checkpoints, over a period of three months (each AG held 4-6 sessions, and each session lasted 1 to 2 hours). Moreover, these sessions were held individually or in groups, face to face, based on the work schedule of the workers and in coordination with the supervisors and heads of divisions.

Phase 3. Identification of Problems and Solutions Phase (as Observing Phase)

To identify the problems and provide practical solutions by the AGs, using the ILO ergonomic checklist, they first identified the problems in different divisions and accordingly the AGs, in the form of technical and informal sessions (with each AG in two sessions and each session for half an hour to 2 hours), and presented their solutions with the help of the ergonomist. The problems and solutions identified by the AGs were completed in the assigned forms and provided to the ergonomist. Then, sessions were held with the ergonomist and the AGs (with each AG in a technical session for an average of 2 hours) for initial review of the proposed problems and solutions and preliminary screening of the solutions.

Phase 4. The Implementation of Solutions and Gaining Participant Reflections on Learning (as Reflecting Phase)

To assess the desirability and feasibility of the proposed solutions, 12 technical sessions (two sessions for each division) were held with the supervisors and representatives of the workers from AGs, HSE division staff (the head of the division, ergonomist, and an occupational health expert), and the heads of divisions. Ultimately, solutions with high feasibility and desirability (determined by participants’ collective comments) were set up for implementation, and then the relevant authorities and timing of implementation were demonstrated. Outcomes of the technical sessions were collected by the ergonomist and provided to the participants to implement the solutions. Also, the HSE division staff, supervisors, and the heads of the divisions followed up on some solutions that needed consultation with other divisions, such as the repair and installation division.

Additionally, the head of the HSE division and the ergonomist held separate sessions with senior management about the allocation of time (without interruption in production) and the budget needed to implement the solutions. Then, the budget needed to implement low-cost solutions was allocated. Furthermore, the ergonomist and the occupational health expert recorded the implementation of the solutions in different divisions through field visits and following up with the heads of divisions and supervisors. It should be noted that the first to the third phase of the study lasted eight months, and the fourth ending phase, regarding the implementation of the solutions, lasted 1.5 years (see for an overview).

Table 3. Technical sessions and their durations in terms of hours and person-hours during the four phases of the study.

To understand the participant’s perceptions of effectiveness of the process, the ergonomist recorded field notes based on observations and informal conversations. At the end of the study, the ergonomist also visited the divisions and conducted simple interviews (for 15 to 60 minutes) to gain reflections from participants. The interviews were conducted among 12 people, including eight workers, three supervisors, and the head of the HSE division. The selection of interviewees was via purposive sampling, and the questions were asked accordingly from informed participants based on the time provided by the company.

2.4. Data Analysis

To analyze quantitative data, including the number of problems and solutions identified and implemented by AGs, descriptive statistics were utilized. A qualitative content analysis method was also applied to analyze interview results and field notes. After transcribing the interviews, the texts of the interviews were coded with an inductive approach, and the codes were read several times. Then, conceptually similar codes were classified into one class. As the process of analysis developed and the evaluation of the extracted codes and themes was repeated, similarities and differences were identified. Eventually, via a continuous comparison, sub-themes were merged and the main theme was extracted. MAXQDA 10 software was used to manage textual data during the coding process.

3. Results

By creating a working team including the ergonomist and 14 AGs, in four phases, the participants’ involvement led to the creation of empirical evidence including improving participants’ competence in providing the problems and solutions, as well as implementing low-cost solutions. (Note: ILO’s ergonomic checkpoints indicate low-cost solutions include solutions that could be solved based on available resources and capabilities of internal forces of an organization.). These results are presented subsequently.

3.1. Problems and Solutions Presentations by the AGs

As indicated in , during the third phase the AGs identified 147 problems after being placed in technical sessions in six different domains of the ergonomic checkpoints, following technical sessions, and provided 145 solutions to improve their working conditions. Based on the technical sessions held in the fourth phase, 134 solutions were approved in terms of feasibility and desirability of the solutions, and the costs required to implement low-cost solutions. Subsequently, 77 solutions (57.5%) were implemented, and 26 solutions (19.4%) entered the planning stage for implementation (), most of which were low-cost solutions. The rest of the solutions were not implemented during the follow-up period, due to the impossibility of implementation, technical changes in the production line, the lack of sufficient funding, or they were included in a long-term implementation plan as development goals. According to follow-ups by the research team, considering the adverse effects of economic sanctions on the financial status of the related company, the implementation of these solutions lasted for a long time but the officials gradually prioritized their implementation. Based on the overall estimation of the proposed solutions (145 solutions), 105 solutions (72.4%) were eligible to be implemented. Based on the capabilities and resources of the manufacturing, 66 solutions were implemented by the end of the last phase.

Table 4. Problems and solutions presentations by the AGs.

3.2. Low-Cost Solutions Implemented in the Different Divisions

In terms of implementation cost, 104 out of 105 solutions were classified as low-cost solutions, and the remaining case as high cost. Among the low-cost solutions, 66 solutions were implemented in different divisions. Some of these solutions are presented in .

Table 5. Examples of low-cost solutions implemented by the AGs in various divisions based on ergonomic checkpoints.

3.3. Results of Participants’ Reflections

According to interviews and field notes, a notable issue about the usefulness of the PEP (main theme) and three sub-themes was proposed. The participants emphasized the importance and effectiveness of the knowledge transfer with ergonomic checkpoints to support the PEP in following sub-themes.

Developing a Participation Culture

According to the participants, the participatory approach of the program led to the consideration of workers’ opinions in improving working conditions. Participants stated that in different phases participation and cooperation between AGs gradually increased, and it led them to work together to suggest solutions and improve their working conditions.

“… The participatory nature of this program was very good. Through the implementation of this participatory program, I realized that the users’ opinion in any organization is very important; however, this is low level in Iranian industries. In this program, the opinion of all colleagues in the division were considered, and we worked together to come up with a series of solutions.” (Supervisor)

“I think that the ergonomics culture is being implemented and personnel consciously do what is necessary, and even some personnel, after completing the program, volunteer to implement other solutions.” (Worker)

Learning and Institutionalizing Ergonomics Principles in Practice

Most of the participants emphasized that utilizing ergonomic checkpoints with the consultation of their colleagues increased their awareness of ergonomics principles. In addition, by implementing some solutions in workstations, they became acquainted with the nature of ergonomics in practice.

“According to the program, our view of ergonomics altered. In other words, by implementing a series of changes, we became better acquainted with the nature of ergonomics. Even after completing the implementation process, I came up with a few solutions myself, and although they were minor solutions, I implemented them.” (Worker)

“Several times, I monitored workers’ behavior during and after the program from the window of my room, which is in front of the main production hall. Most of the time, I see workers trying to follow ergonomics principles, such as carrying the load correctly, sitting down, and then lifting the load.” (The head of HSE division)

Improving Competence of Identifying Problems and Implementing Solutions

According to the participants, this program provided an opportunity to identify the problems in their workplace with the cooperation and participation of HSE division officials and offered solutions to improve working conditions.

“This program helped us to practically identify our problems and implement solutions to improve our working conditions with your help (meaning the ergonomist).” (Worker)

“I think one of the main achievements of this program was that through these checkpoints we were able to provide simple suggestions to improve our working environment. Of course, before this program, I did not think ergonomics could be implemented in workplaces with these simple solutions. Although some of the solutions we have offered are expensive, but they are needed for our division.” (Worker)

Meanwhile, the interviewees suggested 11 recommendations to improve the promotion of the program, which are presented in .

Table 6. Recommendations for improvement and continuation of participatory ergonomics intervention by interviewees.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

This action research study was conducted with the active participation of different organizational levels, especially AGs, and was based on the PEP. Accordingly, the AGs interacted with the ergonomist during different technical sessions (both formal and informal, ) using ergonomic checkpoints knowledge, and consequently different results were achieved to identify problems and provide and implement solutions to improve working conditions ().

The total time spent on technical sessions was 41 hours, involving 1400.5 person-hours (). The technical sessions emphasized action learning inside the workplace and in close interaction between the ergonomist and AGs, instead of focusing just on training, especially in training classes.Thus, the participants were taught with a “learner-centered” approach (i.e., what does the learner do?). One of the important factors in the success of knowledge transfer in safety, health, and ergonomics is the use of a learner-centered approach (Albert & Hallowel, Citation2013; Guzman et al., Citation2008). Yet, most ergonomics interventions focus on training (in the short term) rather than action learning (Helali, Citation2008). From a systematic review, Faisting and de Oliveira Sato (Citation2019) emphasized that most ergonomics interventions, through training, have left little impact on the reduction of work-related physical injuries or the development of ergonomics principles. Therefore, ergonomics interventions based on action learning and a participatory approach can have better effects on improving working conditions (Dastranj & Helali, Citation2016; Helali, Citation2009b).

One of the important issues in ergonomics knowledge transfer is to create a discourse among all levels of an organization (Boatca et al., Citation2018) and to have their physical presence in the intervention environment, to create appropriate communication with appropriate solutions to improve working conditions (Trudel & Montreuil, Citation1999). In the present study and through the implementation phases, different informal and appreciative conversation sessions were held between the ergonomist and AGs () about ergonomic checkpoints, problems, and solutions ( and ). According to the outcomes of interviews, this approach helped the AGs to acquire necessary skills in identifying problems and improving their working conditions.

Given the emphasis on previous theoretical evidence about the use of different tactics in involving participants in the PEP for ergonomics knowledge transfer (Helali, Citation2008), participants in this study, with the direct guidance of the facilitator, were involved in the PEP via a top-down approach of participatory ergonomics, as a pushing tactic for intentional learning (for 8 months) in the first to third phases. Thus, through “learning by doing” the ergonomic checkpoints, they were able to provide 145 solutions to improve their working conditions, of which 104 (72%) solutions were low-cost and could be implemented based on organizational capabilities and resources (). Furthermore, in the fourth phase the participants were involved in the PEP with indirect guidance of the facilitator, with a bottom-up approach of participatory ergonomics as a pulling tactic for voluntary learning (for 1.5 years). Based on that, 77 solutions were implemented, most of which (66 solutions) were low-cost (see and ). The model of participatory ergonomics was introduced by Haines and Wilson (Citation1998) and shows the principles of the participatory ergonomics used by individuals to get involved in designing and analyzing work-related problems, by employing different types of involvement that were introduced by Brown (Citation2002). Therefore, according to , the implementation of different phases created an atmosphere to transfer practical ergonomics knowledge by using ergonomic checkpoints and participants’ learning from each other in an appreciative way. Based on the results of the interviews, they were able to understand the improvement of their technical and social skills.

According to the results of the interviews, the participants emphasized that during different phases, AGs participation gradually increased, and they were able to provide and implement effective solutions to improve their working conditions in different aspects of ergonomic checkpoints () with mutual cooperation. They stated that this participatory approach helped them to realize that their opinion is important in the organization, and they can be efficient in improving their workplace. According to the participatory ergonomics cycle (Haines & Wilson, Citation1998), when people are involved in a problem-solving process, it improves their technical and social skills and further increases their confidence and motivation for more participation.

The results of the interviews also indicate that participants could understand the effectiveness of the PEP through “learning by doing” (as practical knowledge) of practical ergonomics knowledge. It helped them voluntarily implement some solutions in their workplace even after completing the implementation phase. In fact, it promotes a participation culture and institutionalization of ergonomics principles among participants and their workplace. This issue was emphasized by the participants in interviews. Further, it is what Hendrick (Citation1995) has argued, that the output of macroergonomics interventions as top-down (i.e., strategic approach to analysis), bottom-up (i.e., participatory ergonomics), and middle-out approaches (i.e., focus on processes) could lead to a change in culture. Therefore, in the process of positive change with the participatory ergonomics approach, the role of the ergonomist is as a change agent (Helali, Citation2008; Hendrick & Kleiner, Citation2002; Kuorinka, Citation1997). Ergonomists can have a positive effect on ergonomics knowledge transfer, and improve the learning of ergonomics principles and a culture of applying them by facilitating the empowerment of people involved in the change process (Dastranj & Helali, Citation2016; Helali, Citation2009b).

Participants in the interviews stated that by the ergonomist facilitation they acquired the necessary skills to identify problems and solutions and to implement them and improve their working conditions. Although some of the participants, based on the culture change, could voluntarily and independently present and implement new solutions, as they stated () an ergonomist is needed to follow the process of change and continuous learning in the workplace.

Participants gave recommendations for the continuation of the program (). This feedback indicates that the participants, along with understanding the positive effects of the program, were able to make suggestions for improving the implementation of this type of intervention. Along with these suggestions, there is a need for continuous and ongoing planning and continuous learning, as well as a top-down approach with full support of top managers that should be considered in the implementation of the “Ergonomics Intervention Program Technique” supported by the PEP (Helali, Citation2008; Citation2009a). There is also a need for systemic ergonomics intervention work, based on organizational knowledge with the different learning levels (Helali, Citation2015). Hence, to apply systemic ergonomics intervention work more effectively, in addition to bottom-up intervention through PEP, it is necessary to consider macroergonomics intervention (Hendrick & Kleiner, Citation2002) at all three levels in the organizations, including top-bottom, middle-out, and bottom-up in practice.

This suggestion emphasizes that to maximize the benefits of ergonomics knowledge, an awakened need for change should be created to apply ergonomics in the work system of organizations (Abdollahpour & Helali, Citation2016; Helali & Abdollahpour, Citation2014). In this regard, inspired action and improvement in the practical ergonomics knowledge transfer to support the PEP could be led to different learning levels of organizational knowledge, including: 1) Learning by studying, as a theoretical understanding with an emphasis on the ergonomics knowledge transfer and by applying ergonomic checkpoints in an appreciative way; 2) Learning by using, as a strategic understanding of the applied bottom-up intervention approach (participatory ergonomics approach); 3) Learning by doing, as a practical understanding by applying participatory ergonomics process with different participatory approaches for participant involvement, such as a top-down approach, as a pushing tactic for intentional learning, and as a bottom-up approach, as a pulling tactic for voluntary learning; 4) Learning by meta-reflection, meaning thinking again about reflection-on-practice that was achieved by obtaining reflection learning from participants through interviews. These different levels of learning are adapted from Abdollahpour and Helali (Citation2016). These authors suggested continuous learning in ergonomics interventions and emphasized that different levels of learning need to be considered based on Deming’s (Citation1982) continuous improvement cycle, which is Plan-Do-Study-Act.

In this study, the implementation phase faced the lack of budget due to sanctions and extra-organizational problems that affected the implementation of the high-cost solutions. Due to their impact on the supply and implementation of high-cost solutions, it is suggested that the lack of budget and extra-organizational problems should be considered in future studies. A main focus of the heads of divisions on the production process and the difficulty in coordinating the implementation of these programs in production divisions, along with limited time allocated to follow the related tasks, were other limitations. In addition, there was resistance to initiate this study, especially among supervisors, due to weakness in the internalization of some of the previous improvement programs implemented in the company. These limitations caused interruptions in the implementation process. However, with repeated follow-ups by the ergonomist and other HSE division staff, these limitations were solved during the study.

On the other hand, we focused more on physical ergonomic checkpoints. Accordingly, the implemented solutions focused on improving the physical ergonomics conditions, which the participants emphasized. One of the requirements for improving such studies is taking into account the psychosocial conditions of personnel and implementing the relevant solutions (see ). Therefore, in future studies it is suggested to use ILO’s stress at work prevention checkpoints (ILO, Citation2012) along with ILO’s ergonomic checkpoints (ILO, Citation2010). It is also recommended that in future studies, to understand the effectiveness of this type of ergonomics interventions, cost calculations should be examined that are performed especially for solutions.

In conclusion, the results of this study showed that the successful implementation of practical ergonomics knowledge transfer could be done through applying PEP with different tactics for participant engagement. Such tactics include: 1) a pushing tactic approach for intentional learning (for eight months), and 2) a pulling tactic approach for voluntary learning (for 1.5 year) that led through PEP to change outcomes. Using this approach, both improvement of working conditions and promotion of participatory culture were achieved.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants, including workers, supervisors, and production division managers, as well as HSE division officials who participated and contributed to this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not report any conflicts of interest that may have inappropriately influenced this work

References

- Abdollahpour, N., & Helali, F. (2016). Implementing ‘awakened need of change' for applying ergonomics to work system with macroergonomics approach in an industrially developing country and its meta-reflection. Journal of Ergonomics, 6 (6): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.4172/2165-7556.1000182

- Albert, A., & Hallowel, M. R. (2013). Revamping occupational safety and health training: Integrating andragogical principles for the adult learner. Construction Economics and Building, 13(3), 128–140. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v13i3.3178

- Boatca, M. E., Draghici, A., & Carutasu, N. (2018). A knowledge management approach for ergonomics implementation within organizations. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 238, 199–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2018.03.024

- Broday, E. E. (2021). Participatory ergonomics in the context of Industry 4.0: a literature review. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science, 22(2), 237–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/1463922X.2020.1801886

- Brown, O. (2002). Macroergonomic methods: Participation. In H. W. Hendrick, & B. M. Kleiner (Ed.), Macroergonomics: Theory, methods, and applications (pp. 25–44). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Brown, O. (2004). Participatory ergonomics (PE). In Handbook of human factors and ergonomics methods (pp. 777–784). CRC Press.

- Burgess-Limerick, R. (2018). Participatory ergonomics: evidence and implementation lessons. Applied Ergonomics, 68, 289–293. 3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2017.12.009

- Capodaglio, E. M. (2022). Participatory ergonomics for the reduction of musculoskeletal exposure of maintenance workers. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics: JOSE, 28(1), 376–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2020.1761670

- Dagenais, C., Plouffe, L., Gagné, C., Toulouse, G., Breault, A.-A., & Dupont, D. (2017). Improving the health and safety of 911 emergency call centre agents: an evaluability assessment of a knowledge transfer strategy. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics: JOSE, 23(1), 50–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2016.1216355

- Dastranj, F., & Helali, F. (2015). Ergonomic checkpoints, practical and easy-to-implement solutions for improving safety, health and working conditions (Translated ILO book 2010, International Labour Office, Geneva). Farhange Rasa.

- Dastranj, F., & Helali, F. (2016). Implementing “job enrichment” with using ergonomic checkpoints in an ‘Appreciative Way' at a manufacturing company in an industrially developing country and its meta-reflection. Journal of Ergonomics, 6(4): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.4172/2165-7556.1000172

- Deming, W. E. (1982). Out of the crisis. MIT Press.

- Faisting, A. L. R. F., & de Oliveira Sato, T. (2019). Effectiveness of ergonomic training to reduce physical demands and musculoskeletal symptoms-An overview of systematic reviews. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 74, 102845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ergon.2019.102845

- Ghaye, T. (2007). Building the reflective healthcare organisation. John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470691809

- Guzman, J., Yassi, A., Baril, R., & Loisel, P. (2008). Decreasing occupational injury and disability: The convergence of systems theory, knowledge transfer and action research. Work, 30(3), 229–239.

- Haines, H., & Wilson, J. R. (1998). Development of a framework for participatory ergonomics. Institute for Occupational Ergonomics for the Health and Safety executive.

- Helali, F. (2008). Developing an ergonomics intervention technique model to support the participatory ergonomics process for improving work systems in organizations in an industrially developing country and its ‘Meta-Reflection. Lulea University of Technology. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:999826/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Helali, F. (2009a). The ergonomics ‘know-how' transfer models to IDC’s industries: concept, theory, methodology, method, technique. LAMBERT Academic Publishing.

- Helali, F. (2009b). Using ergonomics checkpoints to support a participatory ergonomics intervention in an industrially developing country (IDC)-a case study. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics : JOSE, 15(3), 325–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2009.11076811

- Helali, F. (2015). Building taxonomy knowledge ‘systemic ergonomics intervention work’: A product Joining up practice with theory in an industrially developing country and its' meta-reflection. Paper Presented at the Triennial Congress of the International Ergonomics Association, August 9–14, 2015.

- Helali, F., & Abdollahpour, N. (2014). How could you implement ‘awakened need of change’ for the applying ergonomics to work system in industrially developing countries? [Paper presentation]. International Symposium on Human Factors in Organisational Design and Management (ODAM) 46th Annual Nordic Ergonomics Society (NES) Conference, (Ed.),^(Eds.). 17–21 August 2014 Copenhagen, Denmark: 17/08/2014-21/08/2014.

- Hendrick, H. W. (1995). Future directions in Macroergonomics. Ergonomics, 38(8), 1617–1624. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139508925213

- Hendrick, H. W., & Kleiner, B. (2002). Macroergonomics: Theory. Methods, and Applications. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. https://doi.org/10.1201/b12477

- Hess, J. A., Hecker, S., Weinstein, M., & Lunger, M. (2004). A participatory ergonomics intervention to reduce risk factors for low-back disorders in concrete laborers. Applied Ergonomics, 35(5), 427–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2004.04.003

- Huang, C. M., Chang, H. C., & Henderson, S. (2008). Knowledge transfer barriers between research and development and marketing groups within Taiwanese small‐and medium‐sized enterprise high‐technology new product development teams. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing, 18(6), 621–657. https://doi.org/10.1002/hfm.20130

- ILO. (2010). Ergonomic checkpoints: practical and easy-to-implement solutions for improving safety, health and working conditions (2nd ed.). International Labour Organization. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_protect/@protrav/@safework/documents/instructionalmaterial/wcms_178593.pdf.

- ILO. (2012). Stress prevention at work checkpoints: Practical improvements for stress prevention in the workplace. International Labour Office. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/@publ/documents/publication/wcms_168053.pdf

- Ingelgård, A., & Norrgren, F. (2001). Effects of change strategy and top-management involvement on quality of working life and economic results. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 27(2), 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-8141(00)00041-X

- Kawakami, T., & Kogi, K. (2005). Ergonomics support for local initiative in improving safety and health at work: International Labour Organization experiences in industrially developing countries. Ergonomics, 48(5), 581–590. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140130400029290

- Kogi, K. (2012). Practical ways to facilitate ergonomics improvements in occupational health practice. Human Factors, 54(6), 890–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720812456204

- Kogi, K., Yoshikawa, T., Kawakami, T., Lee, M., & Yoshikawa, E. (2016). Low-Cost Improvements for Reducing Multifaceted Work-Related Risks and Preventing Stress at Work. Journal of Ergonomics, 06 (01): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.4172/2165-7556.1000147

- Kramer, D. M., & Wells, R. P. (2005). Achieving buy-in: building networks to facilitate knowledge transfer. Science Communication, 26(4), 428–444. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547005275427

- Kuorinka, I. (1997). Tools and means of implementing participatory ergonomics. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 19(4), 267–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-8141(96)00035-2

- Meyer, J. (2000). Qualitative research in health care. Using qualitative methods in health related action research. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 320(7228), 178–181. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7228.178

- Neumann, W. P., Dixon, S. M., & Ekman, M. (2012). Ergonomics action research I: shifting from hypothesis testing to experiential learning. Ergonomics, 55(10), 1127–1139. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2012.700327

- Rosecrance, J. C., & Cook, T. M. (2000). The use of participatory action research and ergonomics in the prevention of work-related musculoskeletal disorders in the newspaper industry. Applied Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 15(3), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/104732200301575

- Scott, P. (2009). Ergonomics in developing regions: Needs and applications. CRC Press.

- Scott, P., Kogi, K., & McPhee, B. (2010). Ergonomics guidelines for occupational health practice in industrially developing countries. International Ergonomics Association.

- Shahnavaz, H. (2002). Macroergonomic considerations in technology transfer. In Macroergonomics: Theory, methods, and applications, (pp. 311–322). Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

- Sherehiy, B., & Karwowski, W. (2006). Knowledge management for occupational safety, health, and ergonomics. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing, 16(3), 309–319. https://doi.org/10.1002/hfm.20054

- Shojaei, Z., Helali, F., Ghomshe, S. F. T., Abdollahpour, N., Bakhshi, E., & Rahimi, S. (2020). Stress Prevention at Work with the Participatory Ergonomics Approach in one of the Iranian Gas Refineries in 2017. Iran Occupational Health Journal, 17(1), 1–16. http://ioh.iums.ac.ir/article-1-2732-fa.html.

- Tompa, E., Dolinschi, R., & Natale, J. (2013). Economic evaluation of a participatory ergonomics intervention in a textile plant. Applied Ergonomics, 44(3), 480–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2012.10.019

- Trudel, L., & Montreuil, S. (1999). Understanding the transfer of knowledge and skills from training to preventive action using ergonomic work analysis with 11 female VDT users. Work (Reading, Mass.), 13(3), 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/154193120004401274

- van Eerd, D., Cole, D., Irvin, E., Mahood, Q., Keown, K., Theberge, N., Village, J., St Vincent, M., & Cullen, K. (2010). Process and implementation of participatory ergonomic interventions: a systematic review. Ergonomics, 53(10), 1153–1166. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2010.513452

- Vink, P., Imada, A. S., & Zink, K. J. (2008). Defining stakeholder involvement in participatory design processes. Applied Ergonomics, 39(4), 519–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2008.02.009

- Vink, P., Peeters, M., Gründemann, R. W. M., Smulders, P. G. W., Kompier, M. A. J., & Dul, J. (1995). A participatory ergonomics approach to reduce mental and physical workload. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 15(5), 389–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-8141(94)00085-H