ABSTRACT

As part of an NHS England pilot scheme, Specialist Community Forensic Teams were developed aiming to support service users’ transition of care from secure forensic inpatient settings to living in the community. This study explored the experiences of service users, carers, health professionals and specialist residential accommodation providers in relation to one of these teams. The Good Lives Model was adapted by the team to inform formulation and intervention. Nineteen participants completed a mixed-methods survey. Data were processed using descriptive statistics and thematic analysis. Findings indicate that the use of a strengths-based model within a forensic setting was perceived by stakeholders as providing an experience of relational security and hopefulness. Most stakeholders surveyed endorsed survey items indicative of a positive experience of the service. The findings from this study suggest that GLM is an acceptable model to stakeholders for formulating the needs and strengths of service users in planning their transition from residing in secure settings to living in the community.

Introduction

Forensic mental health teams are tasked with offering support and treatment to service users in order to alleviate suffering and improve mental health, whist also monitoring, reducing and managing potential risk to the public (Bartlett & McGauley, Citation2010; Campling et al., Citation2004). It is recognized that there is a tension between individual recovery and control exercised by the service; with the latter potentially impacting negatively upon individual autonomy, choice and growth. The recovery process is also made intrinsically more complex by the service users’ offending history which can not only diminish future opportunities but also have negative consequences for self-esteem and identity (Drennan & Alred, Citation2012). Drennan and Alred (Citation2012) identify that hope and self-acceptance, which are central to the principles of recovery, can be problematic for forensic service users who have the additional task of coming to terms with harm they have caused. The outcomes for people leaving secure care are poor across a number of measures including mortality rates, recidivism, employment and achieving positive relationships (Clarke et al., Citation2013; Fazel et al., Citation2016; Humber et al., Citation2011; Ministry of Justice, Citation2018).

Finding a means of integrating both meeting the service users’ needs and mitigating potential risks in their safe discharge from forensic settings represents a complex balancing problem for clinicians. Offender rehabilitation can be approached from two distinct theoretical models focussing respectively upon risk reduction or enhancing pro-social functioning (Ward & Stewart, Citation2003). There is relatively little rigorous research examining what model of service and intervention provides best care for offenders with associated mental health problems (Kenney-Herbert et al., Citation2013; National Mental Health Development Unit, Citation2011). Exploration of service user views has highlighted the importance of improved self-esteem, reduced symptoms of mental health problems, return to employment, independence, a sense of meaning in life, positive relationships and developing community networks (Drennan & Wooldridge, Citation2014; Livingston, Citation2018; Mezey et al., Citation2010; Tregoweth et al., Citation2012). These factors are congruent with the key principles of recovery (Repper & Perkins, Citation2003) and provide a good fit with the central premise of strengths-based models such as the Good Lives Model (Ward & Gannon, Citation2006). The Good Lives Model (GLM) argues that offending behavior can be understood as the individual’s attempt to obtain “primary human goods.” These primary human goods are specifically defined as: “healthy living and functioning, knowledge, excellence in play, excellent in work, excellence in agency, inner peace, relatedness, community, spirituality, pleasure, and creativity” (Purvis, Citation2010; Ward & Brown, Citation2004; Ward & Marshall, Citation2004). Willis and Ward (Citation2013) further posit that primary human goods are achieved via “secondary goods,” which are described as the concrete processes an individual engages in (such as joining a volunteering organization to achieve the “primary good of relatedness”) to obtain the primary good. As such, offending behavior is understood as a maladaptive means of achieving a primary good.

The GLM has been gaining traction as a useful theory and formulation tool within forensic mental health services (Barnao, Citation2013; Barnao et al., Citation2010; Barnao, Ward &, Casey, Citation2016; Barnao, Ward &, Robertson, Citation2016; Gannon et al., Citation2011). The most cited criticism of the GLM is its lack of empirical support (Bonta & Andrews, Citation2003; Ogloff & Davis, Citation2004). However, the GLM is not a treatment theory but is rather a rehabilitation framework that is intended to supply practitioners with an overview of the aims and values underpinning its practice. A systematic review carried out by Mallion et al. (Citation2020) suggests interventions based on GLM principles and assumptions are as effective as standard treatment approaches in support services in preventing relapse, increasing motivation to change and engaging in the therapeutic offer. The studies selected for the latter review were similar to the service presented in this paper, in relation to population served and interventions tasks. This suggests that GLM was an appropriate model for our local population’s needs.

The Five Year Forward View for Mental Health (NHS England, Citation2016a) recommended improvements in the care of forensic patients with recommendations that patients are stepped down to the least restrictive setting possible, reside as close to home as possible and that interventions have a stronger focus on recovery. The Mental Health Secure Care Programme was established in 2016 to deliver these recommendations by establishing 17 sites to pilot the Specialist Community Forensic Team. The Specialist Community Forensic Teams were tasked with supporting patients in transitioning to the community and maintaining stability and recovery once living in the community. This afforded a unique opportunity for an agency with powers of enforcement to adopt a strengths-based model.

This paper examines the stakeholder experiences in relation to one of these pilot teams across the following dimensions:

Was the care delivered by the Assertive Transitions Team experienced as helpful in working toward transition from hospital to the community?

What did stakeholders perceive as being particularly helpful or lacking in the support?

What difference, if any, did the strengths-based approach make to the experience of stakeholders?

Setting

This evaluation (developed on the basis of a doctoral assignment completed by the lead author) took place within a forensic service consisting of community, low secure and medium secure settings. The pilot Specialist Community Forensic Team, named the Assertive Transitions Team (ATT), was an addition to the service and aimed to work pro-actively and intensively with service users in the six months leading up to discharge and for up to a year post discharge from the secure wards to the community. The ATT consisted of a multi-disciplinary team including a psychiatrist, occupational therapists, psychologists, psychiatric nurses, social workers, peer support workers, support workers and housing and employment specialists.

The ATT, in conjunction with inpatient colleagues, identified inpatients who could potentially be safely discharged within the following six months. Service users attended meetings with ATT staff to develop Good Lives formulations, which were used to produce individualized transition plans and included actions convergent with GLM assumptions. These plans were used for coordinating care, reviewing the transition to community living and whether goals had been achieved. This fed into the CPA approach used in UK services, and was used in conjunction with standard risk assessment tools such as the HCR-20v3 (Douglas et al., Citation2014).

Methodology

A mixed-methods non-experimental design was employed using a survey which was sent to four participant groups:

AService users who had been under the care of the ATT (n = 26).

BCarers (identified as friends and family) of service users who had been under the care of the ATT (n = 20).

CHealth professionals employed by the local NHS Trust not working in ATT who supported service users who had been under the care of the ATT (n = 22).

DStaff employed by specialist residential accommodation providers involved in the support of service users who had been under the care of the ATT (n = 11).

Materials

A survey entitled “The Assertive Transitions Team Survey” was developed, exploring the aims of the service identified from the service requirements (NHS England, Citation2016b) and team operational policy. Initial drafts were constructed in collaboration with a clinical psychologist from the ATT, which were then reviewed by ATT staff during a multi-disciplinary team meeting, including input from peer support workers. The survey was consequently amended to enhance face and content validity.

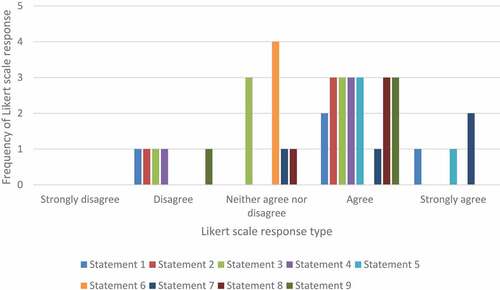

The survey consisted of a total of twelve items. The first nine items were statements requiring respondents to record their level of agreement. Likert scales with a range of one to five (1 = strongly disagree, to 5 = strongly agree) were used to explore stakeholders’ agreement with team goals of listening, collaborative planning, addressing strengths as well as needs, providing support pre- and post-discharge, increasing skills for community living, making community network links and achieving a sense of safety and stability in the community. There was the option of providing additional qualitative feedback for each of these items. A further three further items requested participants to provide views regarding strengths and potential areas for improvement of the team model and functioning, in order to generate rich data regarding the experience of the Good Lives Model. The survey was hosted online using the Qualtrics platform.

Ethical considerations

The project was registered with the audit and information governance teams who considered ethical issues and approved the project from a governance and quality perspective. Service users were invited to take part in the survey during routine contacts with NHS healthcare staff and if in agreement were then sent the link to the questionnaire which included written information regarding consent. Formal consent was recorded prior to completion of the survey. Upon survey completion, participants were provided with debriefing information, supportive contact telephone numbers, and researchers contact information should they have queries. All questionnaires and patient responses were anonymized.

Quantitative data analysis

Twenty surveys were completed; 7 from group A (27% of total eligible participants), 4 from group B (20% of total eligible participants), 7 from group C (32% of total eligible participants), and 2 from group D (18% of total eligible participants). Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. In line with recommendations from Frost et al. (Citation2007), statistical reliability analyses were not conducted given the small sample size.

Qualitative data analysis

Qualitative data were processed using an inductive latent reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The process followed the steps of familiarization with the data, coding, generating initial themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and writing up. Themes were reviewed in discussion with the first supervisor, looking for patterns in the data, and provisional themes were refined through the process of supervision as advocated by Braun and Clarke (Citation2013), with particular focus on the face validity of said themes. Broader themes were identified which were most relevant to answering the research question: “what were the stakeholders” experiences of working with the Assertive Transitions Team?’.

Results

Quantitative results

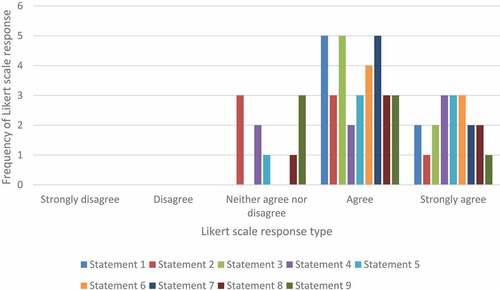

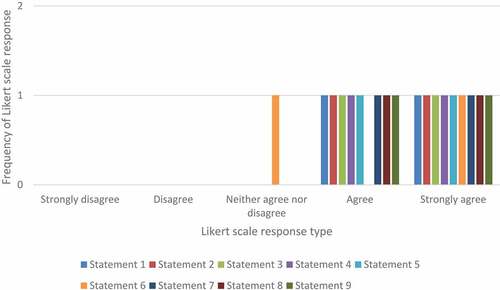

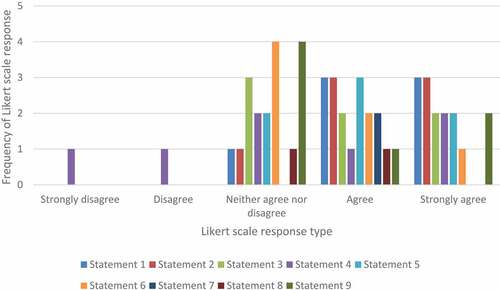

Results predominantly indicated that the majority of Likert scale responses to survey statements were in the 3–5 range in terms of mean, median and modes, suggesting high levels of agreement to survey statements. Highest levels of agreement (with no scores below 3) were given regarding the support provided by the ATT, making links with the community and achieving a sense of safety and stability in the community. Dissatisfaction was expressed by one carer in several domains regarding their lack of involvement in meetings and planning, but they were able to clarify in the narrative that this was because their relative had expressly asked that they not be involved. Two service users expressed dissatisfaction regarding relatives or carers not being involved in meetings and planning; no explanation was given as to why this had not occurred. The results are summarized in and .

Table 1. Mean, median, mode and range of response scores across groups A-D to survey statements.

Figure 1. Frequency of Likert scale response types across survey statements in service user participant group.

Figure 2. Frequency of Likert scale response types across survey statements in carer participant group.

Qualitative results

A total of 141 free text responses were given in response to the 12 survey items. The free text response completion rate was 83.9%, with an average of 20.59 words per response. The sum of all free text responses as a word count was 2904.

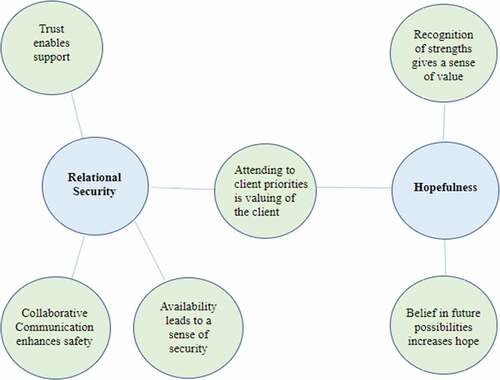

Two superordinate themes and six sub-ordinate themes were developed, which are detailed below, and illustrated with succinct quotes from the original data. A thematic map, illustrating the relationships between themes, is presented in .

Super-ordinate theme 1: relational security

This superordinate theme attends to the experiences that stakeholders described as relating to an experience of feeling safe and secure in their relationships with ATT clinicians and the wider ATT team. The overall experience of relational security is understood as being comprised of a number of care planning processes and interactions which are further illustrated in the sub-ordinate themes.

Sub-ordinate theme 1: collaborative communication enhances safety

A number of responses indicated that collaborative communication between all parties involved in the service user’s care meant that all parties consequently felt safer. Indeed, this sub-theme also encapsulates experiences of feeling listened to and involved in care planning.

Being involved in decisions around my care … made clear any misunderstandings. – Service user D.

They asked my view about risk and that was good because sometimes the NHS teams assume they know best but ATT listened to what I knew about when things went wrong before. – Carer A.

It’s the first time I’ve really felt listened to - and I think I know my relative best so I understand what he needs and what goes wrong. – Carer B.

Sometimes felt that the lack of discussion around risk and history meant that initial plans were unrealistic. However, history was then incorporated. – Health professional E.

They gave us useful information about how to understand and support the service users. The Staying Well plans were really helpful to give clear guidance about how to talk with the service users and what helped them stay stable. – Accommodation provider B.

Sub-ordinate theme 2: trust enables support

This theme was developed on the basis of responses indicating that a level of trust was developed with the ATT and that this was a precursor to being able to accept and use the support on offer. This sub-theme draws on experiences of “knowing” a clinician who is consistently present in their care, as well as an experience of being given time to consider decisions or familiarize with new environments. This suggests that an ability to trust the clinician led to feeling safe in the relationship with them.

They let me get used to the community and just helped me. [It was] eye opening how much help they can give. – Service user A.

I knew he wasn’t messing around or lying, I felt I could trust him. He was a good man and gave me good advise [sic]. – Service user D.

They were really friendly and seemed to genuinely care. They listened to us and we trusted them. – Carer D.

I feel it’s positive for the patient to have that same consistent person who they’ve build rapport with within the inpatient setting, to then be there to support them initially once they’re out of hospital and getting to know the community team. – Health professional C.

Sub-ordinate theme 3: availability leads to a sense of security

This theme attends to stakeholder experiences of being able to interact with ATT when needed. Stakeholders reported that they experienced the ATT as available and accessible which they appreciated and gave them confidence in the transition process. This theme also suggests that experiencing ATT as so available supported stakeholders to feel safe in the relationship with the team, and in the knowledge that support was available should there be concerns about the service user’s wellbeing.

We could phone up if we were worried about anything … they were friendly, available and listened. – Carer A.

We knew the team were there if there were any difficulties even at the weekend. – Carer C.

Always helpful & responsive and available during the weekends. – Placement provider A.

They came to talk with us and to see the service users when things got difficult and helped us to think about what to do. – Placement provider B.

Super-ordinate theme 2: hopefulness

This second super-ordinate theme attends to stakeholder experiencing the ATT as a hopeful service. This theme was developed on the reports of processes and interactions that stakeholders expressed as providing them with hope for the future and for the success of their transition to living in the community.

Sub-ordinate theme 4: attending to client priorities is valuing of the client

This sub-ordinate theme cuts across the super-ordinate themes of “relational security” and “hopefulness.” Responses named numerous issues which were identified as important by the service user and family in making the move from hospital to the community, which were attended to by ATT. This theme encapsulates both a sense of relational security insofar as client priorities were respected and supported, which were also convergent with future-focused tasks which suggest a hopefulness that service users could successfully transition to living in the community. It was also noted that some client priorities may be more or less challenging to achieve, such as goals relating to securing employment.

They got me a bank account up and running which was really helpful. – Service user A.

ATT workers helped arrange voluntary work at a radio station in [town]. – Service user C.

Practical help in setting up home … helped build furniture, put up hooks and rails etc. – Carer C.

Huge leap to go from many years in forensic hospital care to be expected to apply and go for interviews for jobs … Much more work needed on employment side from ATT or MH services in general. – Carer C.

Sub-ordinate theme 5: recognition of strengths gives a sense of value

This sub-ordinate theme encapsulates experiences of service user strengths being recognized by ATT, which provides a sense of being valued. Stakeholders recognized that the ATT was concerned with the service user’s strengths in formulating the care plan and this was connected to experiencing the team as caring and valuing the whole person. Indeed, recognition of strengths is also convergent with a larger super-ordinate theme of hopefulness, insofar as said strengths are highlighted by ATT as being important for a successful transition to community living.

The OT in the team was really good, and was always working with the patient to identify community activities they were interested, and helped signpost them. – Carer A.

ATT were really focussed on getting him the right placement and wanted to know about hobbies and interests. – Carer B.

It’s nice it wasn’t all negative … it was the best team we have worked with. – Carer D.

[Recognising strengths] was the team’s strongest area. They were very person centred and used a strength-based approach. – Health professional C.

Sub-ordinate theme 6: belief in future possibilities increases hope

This theme was developed from responses expressing that the future focussed planning for developing a “good life” in the community increases feeling hopeful. These experiences seem to have been perceived in the context of future-focused conversations with ATT staff, as well as in the more formal care planning process.

It gave me hope when [living in the community] was discussed. – Service user D.

“Chats with staff felt hopeful … more future focussed.” – Service User E.

Having someone to talk to about the future, instead of the present. I want to look to the future to have hope. – Service User F.

They were optimistic and hopeful and respectful … They were interested in him having as good a life as possible. – Carer A.

Helped plan for discharge at an early stage …. which gave the patient hope and something to work towards. – Health Professional C.

Discussion

The findings suggested that all stakeholder groups experienced the ATT as a helpful service. Our findings also suggest that GLM is an acceptable model to a variety of stakeholders in formulating service user needs and strengths in planning their transition from being discharged from secure settings to living in the community. The themes that were developed from the data suggest that the strengths-based approach of the service was applied in a manner that sits well with recovery principles of taking a holistic, person-centered approach, that is supportive of social inclusion and the development of a positive sense of identity (Repper & Perkins, Citation2003). The themes highlighted the quality of the interactions between the team and service users which allowed the building of trust and the forming of hope-inspiring relationships. An interactional relational aspect of the service appeared to run through most of the themes and the results suggested that ATT was perceived as establishing a culture that valued and sustained healthy relationships which, in turn, enabled the team to provide successful support in the transition process. This is perhaps not surprising, as the central role of the relationship between professional and client has been highlighted in relation to therapeutic change (Safran & Muran, Citation2000) and to the recovery process (Ashcraft & Anthony, Citation2006).

It is also apparent from the themes that risk and safety were not side-lined in the pursuit of strengths-based goals, but actually appeared to be a central thread. This is contrast to the Andrews et al. (Citation2011) view that GLM offers a “weak assessment approach.” Relational security is now widely recognized as an important strand in managing risk with forensic patients (Department of Health, Citation2010) and the link made between good communication and safety has been found by many inquiries (see for example, Caring Solutions (UK) Ltd, Citation2016). One healthcare professional participant did voice a concern regarding the possibility of plans being unrealistic due to a lack of discussion about risk but then countered this by saying that the patients’ histories were then incorporated into thinking and planning by the ATT. The study’s findings that the service was experienced as hopeful is important, as hope has been suggested as being a protective factor in forensic risk assessments (Hillbrand & Young, Citation2008).

The operation of the ATT likely presented a stark contrast with the usual risk-orientated approach of the surrounding structure and services. Shepherd et al. (Citation2008) named ten organizational challenges faced by services attempting to incorporate recovery into routine practice and identified that changing the approach to risk assessment and risk management is one of those challenges. The findings suggest that stakeholders experienced that ATT were able to continue to effectively manage risk whilst taking a strengths-based approach.

The feedback referred to the team having the capacity to offer weekend hours and to respond flexibly and intensively to need; one healthcare professional compared this with their own lack of time. It seemed it was advantageous to have a team dedicated to achieving successful transition from secure hospital with ring-fenced time and resources to dedicate to this. As pointed out by one of the carer participants, this transition is a huge step after spending years in forensic hospital and the degree of challenge and potential for decompensation should not be underestimated. The theme highlighting the importance of the detail in the planning is indicative of how easy it might be to miss something seemingly insignificant to the professional system which could potentially lead to destabilization of the whole process. ATT’s success in this area could be connected to the strengths found in communication or possibly, as found elsewhere, related to the presence of peer support workers in the team which enabled holding seemingly small issues as equally important to those more traditionally center stage (Moore & Zeeman, Citation2020).

There were some difficulties associated with being a new team that warrant a mention, including overlap with services already operating and some lack of clarity regarding roles initially, and concern regarding the time-limited nature of the project. These have not been expanded upon as they appear to be clearly related to the status of the team as a pilot project rather than the model of delivery. Conversely, perhaps being a pilot project additional to services already operating allowed the time, energy, and commitment to achieve such positive results. It was quite an accolade for the team to be identified by a carer as “the best team we have worked with.”

Limitations and recommendations

This study was based upon a small sample, and although caution is recommended in generalizing results, our findings may support clinicians to consider how GLM could be used to innovate in their own services. The lead supervisor worked within the ATT service which may have had an impact upon objectivity. The response rate of the whole cohort of stakeholders accessing or collaborating with ATT support was in keeping, or slightly lower than, response rates described as “typical” in mental health services research (Hawley & Cook, Citation2009). The response rate may have been influenced by the survey being completable online only, although we attempted to mitigate this by offering phone calls with researchers as an alternative. The response rate may also suggest that some individuals who may have important differing views did not participate in our study.

The results tentatively add to the growing evidence base advocating for the effectiveness of a strengths-based approach within forensic services. Further research is recommended to expand upon the small number of participants in this study and to expand upon the themes developed in this paper. Longitudinal studies would be useful in examining the impact of a strengths-based approach in reducing length of stay in forensic wards and also increasing stability in the community and reducing the risk of recall.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants who took the time to give feedback regarding their experience of the ATT. We would also like to acknowledge all the team members of the ATT who were dedicated to the implementation of this model of care.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Andrews, D. A., Bonta, J., & Wormith, J. S. (2011). The risk-need-responsivity (RNR) model: Doe adding the good lives model contribute to effective crime prevention? Criminal Justic and Behaviour, 38(7), 735–755. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854811406356

- Ashcraft, L., & Anthony, W. A. (2006). Factoring in structure: Recovery needs a solid foundation to take root. Behavioral Healthcare, 26(8), 16–18. https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/behavioral/article/factoring-structure

- Barnao, M., Robertson, P., & Ward, T. (2010). Good lives model applied to a forensic population. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 17(2), 202–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218710903421274

- Barnao, M., Ward, T., & Casey, S. (2016). Taking the good life to the institution: Forensic service users’ perceptions of the good lives model. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 60(7), 766–786. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X15570027

- Barnao, M., Ward, T., & Robertson, P. (2016). The good lives model: A new paradigm for forensic mental health. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 23(2), 288–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2015.1054923

- Barnao, M. (2013). The good lives model tool kit for mentally disordered offenders. Journal of Forensic Practice, 15(3), 157–170. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFP-07-2012-0001

- Bartlett, A., & McGauley, G. (2010). Forensic mental health: Concepts, systems, and practice. Oxford University Press.

- Bonta, J., & Andrews, D. A. (2003). A commentary on Ward and Stewart’s model of human needs. Psychology, Crime & Law, 9(3), 215–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683/16031000112115

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. SAGE.

- Campling, P., Davies, S., & Farquharson, G. (Eds.). (2004). From toxic institutions to therapeutic environments: Residential settings in mental health services. Gaskell.

- Caring Solutions (UK) Ltd. (2016). An independent thematic review of investigations into the care and treatment provided to service users who committed a homicide and to a victim of homicide by Sussex partnership NHS Foundation Trust. http://www.sussexpartnership.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/vol_1_main_report.final_1.17.10.16.pdf

- Clarke, M., Duggan, C., Hollin, C. R., Huband, N., McCarthy, L., & Davies, S. (2013). Readmission after discharge from a medium secure unit. The Psychiatrist, 37(4), 124–129. https://doi.org/10.1192/PB.BP.112.039289

- Department of Health. (2010). See think act. Department of Health Secure Services Policy Team.

- Douglas, K. S., Hart, S. D., Webster, C. D., & Belfrage, H. (2014). HCR-20V3: Assessing risk of violence – User guide. Mental Health, Law, and Policy Institute, Simon Fraser University.

- Drennan, G., & Alred, D. (2012). Recovery in forensic mental health settings. In G. Drennan & D. Alred (Eds.), Secure recovery (pp. 1–22). Routledge.

- Drennan, G., & Wooldridge, J. (2014). Making recovery a reality in forensic settings (ImROC Briefing Paper 10). Centre for Mental Health and Mental Health Network, NHS Confederation.

- Fazel, S., Fimińska, Z., Cocks, C., & Coid, J. (2016). Patient outcomes following discharge from secure psychiatric hospitals: Systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 208(1), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.149997

- Frost, M. H., Reeve, B. B., Liepa, A. M., Stauffer, J. W., & Hays, R. D.; the Mayo/FDA Patient-Reported Outcomes Consensus Meeting Group. (2007). What is sufficient evidence for the reliability and validity of patient-reported outcome measures? Value in Health, 10(2), 94–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00272.x

- Gannon, T. A., King, T., Miles, H., Lockerbie, L., & Willis, G. M. (2011). Good lives sexual offender treatment for mentally disordered offenders. The British Journal of Forensic Practice, 13(3), 153–168. https://doi.org/10.1108/14636641111157805

- Hawley, K. M., & Cook, J. R. (2009). Do noncontingent incentives increase survey response rates among mental health providers? A randomized trial comparison. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 36(5), 343–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-009-0225-z

- Hillbrand, M., & Young, J. L. (2008). Instilling hope into forensic treatment: The antidote to despair and desperation. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 36(1), 90–94. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18354129/

- Humber, N., Hayes, A., Wright, S., Fahy, T., & Shaw, J. (2011). A comparative study of forensic and general community psychiatric patients with integrated and parallel models of care in the UK. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 22(2), 183–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2010.528010

- Kenney-Herbert, J., Taylor, M., Puri, R., & Phull, J. (Eds.). (2013). Standards for community forensic mental health services. Royal College of Psychiatrists.

- Livingston J. D. (2018). What Does Success Look Like in the Forensic Mental Health System? Perspectives of Service Users and Service Providers. International journal of offender therapy and comparative criminology, 62(1), 208–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X16639973

- Mallion, J. S., Wood, J. L., & Mallion, A. (2020). Systematic review of “good lives” assumptions and interventions. Aggression and Violent Behaviour, 55, 101510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2020.101510

- Mezey, G.C., Kavuma, M., Turton, P., Demetriou, A., & Wright, C. (2010). Perceptions, experiences and meanings of recovery in forensic psychiatric patients. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 21 (5), 683–696. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2010.489953

- Ministry of Justice. (2018). Annex A: Proven reoffending rates for restricted patients statistics, 2010 to 2016. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/proven-reoffending-statistics-quarterly-january-to-december-2014

- Moore, T., & Zeeman, L. (2020). More ‘milk’ than ‘psychology or tablets’: Mental health professionals’ perspectives on the value of peer support workers. Health Expectations, 24(2), 234–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13151

- National Mental Health Development Unit. (2011). Pathways to unlocking secure mental health care. Centre for Mental Health.

- NHS England. (2016a). The five year forward view for mental health.

- NHS England. (2016b). Mental health secure programme. https://www.england.nhs.uk/mental-health/adults/secure-care/

- Ogloff, J. R. P., & Davis, M. R. (2004). Advances in offender assessment and rehabilitation: Contributions of the risk‐needs‐responsivity approach. Psychology, Crime & Law, 10(3), 229–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/0683160410001662735

- Purvis, M. (2010). Seeking a good life: Human goods and sexual offending. Lambert Academic Press.

- Repper, J., & Perkins, R. (2003). Social inclusion and recovery: A model for mental health practice. Bailliere Tindall.

- Safran, J. D., & Muran, J. C. (2000). Negotiating the therapeutic alliance: A relational treatment guide. Guildford Press.

- Shepherd, G., Boardman, J., & Slade, M. (2008). Making recovery a reality. Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health.

- Tregoweth, J., Walton, J.A., & Reed, K. (2012). The experiences of people who re-enter the workforce following discharge from a forensic hospital. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 37 (1), 49–62.

- Ward, T. & Brown, M. (2004). The good lives model and conceptual issues in offender rehabilitation. Psychology, Crime, & Law, 10(3), 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160410001662744

- Ward, T., & Gannon, T. A. (2006). Rehabilitation, etiology, and self-regulation: The comprehensive good lives model of treatment for sexual offenders. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 11(1), 77–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2005.06.001

- Ward, T., & Marshall, W. L. (2004). Good lives, aetiology and the rehabilitation of sex offenders: A bridging theory. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 10(2), 153–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600412331290102

- Ward, T., & Stewart, C. (2003). Criminogenic needs and human needs: A theoretical model. Psychology, Crime & Law, 9 (2) , 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316031000116247

- Willis, G., & Ward, T.et al (2013). The good lives model: evidence that it works. In L.Craig, L.Dixon, and T.A.Gannon (Eds.), What works in Offender Rehabilitation: an evidence based approach to assessment and treatment (pp.305–318). John Wiley & Sons.