ABSTRACT

So far, few studies have assessed emotional rapid response impulsivity (RRI) in incarcerated men. Available studies use varying methodological approaches and show mixed results, but incarcerated individuals are more likely to be impaired by emotional RRI. None of these studies, however, reported on any correlational or regression analysis assessing whether emotional RRI was linearly related to antisocial behavior in general or aggression and misconduct in particular. The current study investigated whether incarcerated individuals (n = 283) show impaired performance on an emotional Go/No-Go task compared to non-incarcerated controls (n = 51), and whether performance is associated with increased trait aggression, and within-prison misconduct. The results indicate that incarcerated individuals indeed show impaired emotional RRI compared to non-incarcerated controls, irrespective of emotional condition, but impaired emotional RRI was not related to trait aggression or within-prison misconduct. The impairment, relative to non-offending controls, could therefore be related to other factors than their anti-social behavior, which could hamper the use of emotional RRI in risk assessment or forensic clinical practice.

Self-control is a central element of the influential “theory of crime,” which states that a combination of (impaired) self‐control and situational opportunity is the primary underlying cause of crime (Gottfredson & Hirschi, Citation1990). Although originally thought to be a stable and unidimensional construct, there is debate about its definition and operationalization (Burt, Citation2020). Studies suggest that self-control may be divided into risk-seeking and impulsivity (Steinberg et al., Citation2008), and these are empirically distinct and develop in divergent ways that are consistent with the dual system model (Forrest et al., Citation2019).

Impulsivity is a central concept in the study of aggressive (Barratt et al., Citation1994), antisocial, or risky behavior (Armstrong et al., Citation2020). Meta-analyses conclude that impulsivity is one of the strongest known correlates of crime (Vazsonyi et al., Citation2017), and recent research suggests that impulsivity is a possible target for intervention within a forensic psychiatric sample (Billen et al., Citation2019). There is, however, considerable debate about defining and measuring impulsivity. Different subdivisions of impulsivity have been proposed, but generally these constructs are poorly correlated, which suggests that referring to these constructs as “impulsivity” is problematic (Cyders & Coskunpinar, Citation2011) and may lead to vague conclusions, obscure existing relationships, and inconsistencies across studies (Cyders, Citation2015). Research should therefore focus on subdivisions of impulsivity, instead of overarching constructs.

Recently, two distinct forms of impulsivity were proposed and described: rapid response impulsivity (Hamilton, Littlefield et al., Citation2015) and choice impulsivity (Hamilton, Mitchell et al., Citation2015). Both articles introducing these concepts include guidance to standardize their measurements and propositions for further research, including their association with risky behavior (Hamilton, Littlefield et al., Citation2015). Choice impulsivity is defined as a reduced capability or willingness to tolerate delays. However, rapid response impulsivity (RRI) indicates a tendency toward immediate and inappropriate action, which does not correspond with the context at hand and which occurs with diminished forethought. RRI has also been described as a diminished ability to inhibit prepotent responses (Hamilton, Littlefield et al., Citation2015) and may include both the failure to refrain from action initiation and failure to stop an ongoing or prepotent action.

The poor conceptualization of impulsivity constructs in studies focusing on forensic populations is problematic because such information is increasingly relevant for the criminal justice system, especially for the treatment of forensic patients (Bootsman, Citation2019), and for risk assessment (Cheng et al., Citation2019; Popma & Raine, Citation2006). Questionnaires – mostly measuring trait impulsivity – are often used for forensic assessment, but recent research suggests that experimental psychology tasks may complement existing assessment tools, because they are less sensitive to socially desirable answers, more versatile, and suitable for individuals across the literacy spectrum (Vedelago et al., Citation2019). Impulsivity measured with self-reported questionnaires or experimental psychological tasks may reflect different behavioral tendencies (Cyders, Citation2015). Questionnaires on impulsivity measure a relatively stable characteristic, whereas experimental psychological tasks are sensitive to different contexts or states. Additionally, experimental psychology tasks may add information on state impulsivity or impulsivity in specific contexts, which may hold relevance for both risk and psychiatric assessment (Brassard & Joyal, Citation2022).

Recent reviews and meta-analyses indicate that offenders experience more difficulties on RRI tasks compared to controls (Vedelago et al., Citation2019) and that RRI is implicated in many psychopathologies and maladaptive behaviors, including attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (Wright et al., Citation2014), aggression (Puiu et al., Citation2018), and antisocial behavior in general (Ogilvie et al., Citation2011). Studies assessing RRI in offending populations generally use non-emotional stimuli (Vedelago et al., Citation2019), whereas RRI problems mainly manifest in emotionally demanding or stressful situations, and reviews therefore stress the importance of contingencies such as emotions and stress in assessing response inhibition (Eben et al., Citation2020; Tittle et al., Citation2003).

Functionally, non-emotional RRI tasks mainly require the activation of cortical structures, including the prefrontal, (pre-)supplementary motor, ventromedial, insular, and parietal cortex (Bari & Robbins, Citation2013; Hamilton, Littlefield et al., Citation2015). Research suggests that these cortical structures are important in the etiology of antisocial behavior and aggression, specifically owing to their capability to control behavior under the influence of stress and emotion. For example, the prefrontal cortex is thought to monitor and regulate amygdala activity (Gillespie et al., Citation2018), and a disruption within this connectivity is thought to underlie antisocial and criminal behavior (Ling et al., Citation2019). Incorporating emotional contingencies within the assessment of impulsivity in general, and response inhibition , specifically, therefore seems paramount.

To date, there have been only three studies comparing emotional RRI in adult offending populations to non-offending controls, two of which report significant impairment in emotional RRI in offenders (Baliousis et al., Citation2019; Turner et al., Citation2018) and one that does not (Meier et al., Citation2012). There are considerable differences in their methodological approaches, for example, regarding subjects, the stimuli that were used, and covariates that were included (see, ). The chosen stimuli differ in each study, which complicates comparisons between studies, on the one hand, but may also indicate higher specificity for the emotional response, which is expected in certain offending subgroups. For example, fake nude images of children are likely to elicit more problems with RRI owing to the high salience of these stimuli for child sexual abusers. Similarly, aggressive populations may have stronger reactions to emotional faces owing to interpretation and hostile attribution biases (Mellentin et al., Citation2015; Tuente et al., Citation2019). The non-significant findings in the study by Meier et al. (Citation2012) are likely owing to the small number of participants (N = 13 per group), both other studies included significantly more participants. Since groups in the study by Turner et al. (Citation2018) differed on age and education, adding these as covariates significantly impairs the interpretability of their findings (Field, Citation2009). Based on the above, incarcerated individuals are likely to be impaired by emotional RRI, but none of these studies reported any correlational or regression analysis assessing whether emotional RRI was linearly related to aggressive or antisocial behavior.

Table 1. Summary table of previous emotional rapid response inhibition studies in offending populations.

The use(ability) of such information from experimental psychological tasks within a criminal justice context (e.g., risk and psychiatric assessment) depends not only on its discriminatory ability between incarcerated/offending populations and non-incarcerated controls but even more so on whether scores on these tasks are related to, and predictive of, antisocial behavior. Studies assessing (non-emotional) RRI show mixed results regarding the prediction of future offending (Aharoni et al., Citation2013; Brassard & Joyal, Citation2022; Fine et al., Citation2016; Zijlmans et al., Citation2021). Two studies applied functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) during an RRI task, one showing that brain activity in the anterior cingulate cortex predicts future rearrests in adults (Aharoni et al., Citation2013), but these fMRI findings were not replicated in young adults (Zijlmans et al., Citation2021). Four studies have also reported behavioral measures of RRI, improving prediction of future offending in 6 months – but not in 12 months – compared to a self-reported questionnaire in a juvenile sample (Fine et al., Citation2016), but again these results were not replicated by Zijlmans et al. (Citation2021), Brassard and Joyal (Citation2022), or Aharoni et al., (Citation2013). The usability of non-emotional RRI for risk assessment is therefore currently inconclusive, possibly owing to its use of non-emotional stimuli.

In conclusion, only few studies use emotional RRI in offending populations, methodological approaches differ between studies, and emotional RRI has not been investigated in relation to antisocial behavior within these offending populations. It therefore remains unclear whether impaired emotional RRI is related to aggressive or antisocial behavior within groups that are characterized by such behavior, and therefore, the possible use of emotional RRI for risk assessment and forensic clinical practice is unclear.

In the current study, we assess emotional RRI differences between non-incarcerated controls and a large sample of incarcerated individuals and assess whether emotional RRI is related to trait aggression and within-prison misconduct. We hypothesize that incarcerated individuals show impaired emotional RRI and that impaired performance is associated with increased (trait) aggression and within-prison misconduct within the incarcerated sample. To evaluate these hypotheses and questions, the current study employed an emotional Go/No-Go task with negative, positive, and neutral faces in both an incarcerated population and in non-incarcerated controls.

Method

Data sources

Data for this study were gathered in two separate projects focusing on (a) neurobiological characteristics of Dutch incarcerated (removed for anonymization) and (b) the (removed for anonymization) on the quality of prison life in Dutch prisons.

Participants

A total of 283 incarcerated men were recruited from six prisons in the Netherlands, located in geographically dispersed regions. Individuals in regular prison and pretrial regimes were eligible for participation, but prisoners in maximum security or psychiatric units were excluded. Participants were required to be incarcerated for at least 3 weeks, because psychophysiological data were collected and initial stress of entering the prison system would otherwise have confounded these data (see (Den Bak et al., Citation2018) for a Dutch report). Participants were recruited through poster advertisements, internal newsletters, and personal communication.

The participating incarcerated men were relatively comparable to the whole prison population (n = 5564), based on age and nationality (see (Den Bak et al., Citation2018) for a Dutch report). Owing to a required minimum of 3 weeks of incarceration, the sample consisted of incarcerated men with a longer than average sentence length (median of 345 compared to 242.5 days) and were more often convicted instead of awaiting trial (55% vs. 32%).

Additionally, 51 non-incarcerated men (NIC) were recruited as a control group through online advertisement, social media, and personal communication. Recruitment was focused on people with lower than average education levels to increase comparability to the incarcerated participants. The study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Psychology Department of the University of Leiden, and participants signed an informed consent form after a thorough explanation of the research procedure – consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki – before participating in the study. Incarcerated and non-incarcerated participants were remunerated for their participation with €10; for incarcerated individuals, this amount was transferred into their prison bank account.

Procedure and instruments

Participants performed several experimental psychology tasks, including – but not limited to – an emotional Go/No-Go task. All participants were tested between March 2017 and February 2018. Several electrodes were placed upon the upper body and the right hand for psychophysiological measurements, which are beyond the scope of this paper and are not reported here. Additionally, participants were requested to fill in several questionnaires.

Incarcerated participants completed the experimental psychological tasks in well lit, quiet rooms within the prison, for example, the library, consulting room, or reintegration center. Control participants completed the task in a room at Leiden University, mimicking the noise/distraction level found in the prison. To reduce the time needed to complete the testing protocol, incarcerated participants could complete the questionnaires within their cell.

Emotional Go/No-Go task

To assess emotional RRI, an emotional Go/No-Go task was administered. During this task, participants were instructed to press the spacebar with their dominant hand as fast as possible when identifying a pre-specified emotional expression (e.g., fearful) but not for another emotional facial expression (e.g., happy), which was not specified beforehand and was presented 30% of the time (“No-Go trials”). The task consisted of six blocks, consisting of 48 trials each, and in each block, a different combination of emotional faces was used: happy(go)-neutral(no-go), fearful(go)-neutral(no-go), neutral(go)-fearful(no-go), neutral(go)-happy(no-go), happy(go)-fearful(no-go), and fearful(go)-happy(no-go). The pictures originated from the NimStim set (Tottenham et al., Citation2009) and include 12 different individuals (6 females). Each picture was presented for 500-ms inter-trial interval was 1000 ms, and task completion took about 8 minutes. Participants with poor understanding and/or compliance with task instructions were removed from analysis when their percentage of correct responses on “Go” trials were below 25% on all emotion conditions (n = 0). In line with Meule (Citation2017), commission error rate (erroneously pressing the button during a No-Go trial) was used as a measurement of response inhibition. Omission errors (reflecting inattention) and reaction time during Go trials (attention/response bias) are used as secondary outcome measures since they lack substantive empirical basis as outcome measures for response inhibition (Meule, Citation2017) and are reported in Supplement 1.

Aggression and prisoner misconduct

The incarcerated participants completed the Dutch version (AVL-AV) of the Aggression Questionnaire (Buss & Perry, Citation1992; Hornsveld et al., Citation2009). This 12-item questionnaire uses a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from completely disagree to completely agree and provides a total aggression score (Cronbach's alpha = 0.88).

Data on misconduct were based on official disciplinary reports, recorded in the Central Digital Depot (CDD+) system of the Dutch Custodial Institutions Agency. Data were available from July 2016 to February 2018 on different types of misconduct, including verbal misconduct, physical misconduct, property misconduct, and possession of contraband. These were combined to include one dichotomous measure that indicated whether someone had received a report for misconducted (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Data analysis

Before the analyses, age was mean-centered, and outliers were determined with Cleveland dot plots and subsequently removed (see above). Data exploration and analysis was executed in RStudio (v1.2.5001) and was based on Zuur et al. (Citation2010) and Heymans and Eekhout (Citation2019)

Data imputation

Unfortunately, not all incarcerated participants completed the questionnaires regarding trait aggression (36.5%) or the emotional Go/No-Go task (2.5%). Those incarcerated individuals with missing data (n = 106) were significantly younger (P = .001) (Mage = 32.7 SD = 11.1) compared to those who did complete the questionnaires (n = 178, Mage = 38.3 SD = 12.4) but did not differ in education level (P = .16). Scores are likely missing because some incarcerated individuals did not return questionnaires after testing procedures ended and owing to failure to complete the emotional Go/No-Go task.

Using multiple-imputation of missing data is regarded as a state-of-the-art technique since it improves accuracy and statistical power relative to other missing data techniques. Therefore, incomplete variables were imputed under fully conditional specification, using the default settings of the mice 3.0 package (Van Buuren & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, Citation2011), resulting in 50 imputed datasets. Derived variables were first computed and then imputed. Imputed data were inspected and compared to observed data using traces and stripplots. All analyses reported below are performed separately on each of these 50 datasets, and both results and estimates are pooled using Rubin's rules.

Group differences

To assess whether incarcerated men showed impaired performance on the emotional Go/No-Go task, a mixed factor ANOVA was performed, with commission error rate as the dependent variable, group (incarcerated/non-incarcerated) as between-subject factor, and emotion (happy(go)-neutral(no-go), fearful(go)-neutral(no-go), neutral(go)-fearful(no-go), neutral(go)-happy(no-go), happy(go)-fearful(no-go), and fearful(go)-happy(no-go).) as within-subject factor. Both interaction and main effects were included in the model at first, and non-significant interaction effects were removed from the final model.

Additionally, similar analyses are presented with omission errors and Go trial reaction times as dependent variables, these are reported in Supplement 1. Since groups differed in age and education levels, these could not be added as covariates since they would violate the ANCOVA assumptions (Field, Citation2009).

Response inhibition and misconduct or aggression

Analyses of the relationship between response inhibition (commission error rate) and aggression or misconduct were conducted only for a sample of incarcerated individuals.

To assess whether commission error rate was related to aggression, a linear regression analysis was performed with aggression as the dependent variable, commission error rate as independent variable, and emotion (happy(go)-neutral(no-go), fearful(go)-neutral(no-go), neutral(go)-fearful(no-go), neutral(go)-happy(no-go), happy(go)-fearful(no-go) and fearful(go)-happy(no-go).) as within-subject factor. Both interaction and main effects were included in the model at first, and non-significant interaction effects were removed from the final model. In a second analysis, both age and education were added as covariates.

To assess whether commission error rate was related to misconduct, logistic regression analyses were performed with misconduct as the dependent variable. Commission error rate was the independent variable, and emotion (happy(go)-neutral(no-go), fearful(go)-neutral(no-go), neutral(go)-fearful(no-go), neutral(go)-happy(no-go), happy(go)-fearful(no-go) and fearful(go)-happy(no-go)) were the within subject-factor. Both interaction and main effects were included in the model at first, and non-significant interaction effects were removed from the final model. In a second analysis, both age and education were added as covariates.

Results

Sample characteristics

As shown in , incarcerated and non-incarcerated men significantly differed in education, age, and trait aggression. A total of 17% of the incarcerated men had a disciplinary report for misconduct.

Table 2. Sample characteristics. This table shows sample characteristics per group. Prevalence rates and interquartile range are denoted within brackets.

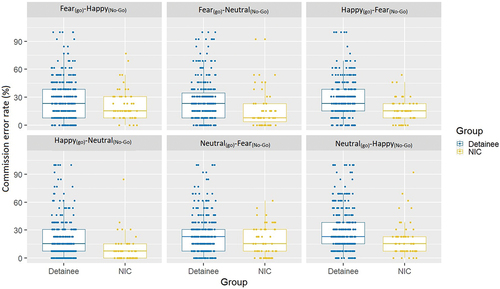

Group differences

The mixed ANOVA analysis revealed that adding the interaction between group and emotion conditions, and their main effects significantly improved model fit compared to an empty model (F(11, 76,880) = 9.184, P < .001), but since the interaction term was non-significant (all p > .15), we excluded the interaction term from the model. A non-significant interaction term indicates that the difference in commission errors between incarcerated individuals and NICs did not fluctuate between emotion conditions, see . The final model (with main effects for group and emotion conditions) did not differ from the model with an interaction (F(5, 2,868,000) = 0.702, P = .62).

Table 3. Commission Error Estimates are compared to a reference category (group: incarcerated individuals and emotion condition: Happy-Fear). Therefore, incarcerated individuals make more commission errors compared to NIC, and both groups make less commission errors in both Happy(go) -Neutral(No-Go) and Neutral(go) – Fear(No-Go) compared to the Happy(go) – Fear(No-Go) condition.

The main effects within this final model indicate that incarcerated individuals make more commission errors, compared to non-incarcerated controls (t(1990.15) = −3.65, P < .001), see . Furthermore, more commission errors were made by participants (aggregating both groups) in the emotion condition: Happy(go)-Fear(No-Go), compared to Happy(go)- – Neutral(No-Go) (t(1752.25) = −7.07, P < .001), and Neutral(go) – Fear(No-Go) (t(1761.44) = −2.61, P < .01). Together, these results show a general deficit in response inhibition for incarcerated individuals, relative to NIC participants irrespective of emotion condition.

Response inhibition and antisocial behavior

Aggression

A linear regression analysis was performed for the incarcerated participants, including aggression as dependent variable, commission errors, emotion condition, and their interaction as independent variables, and subject as within-subject factor. The results indicate that the full model did not improve the model fit compared to an empty model (F(11, 1414.21) = 0.06, P = .99). Removing the non-significant interaction between commission errors and emotion condition (F(5, 1173.83) = 0.12, P = .99), and main effect of emotion condition (F(5, 1185.84) = 0.005, P = .99) from the model did not improve model fit. None of the individual predictors displayed a significant relationship with aggression.

Adding age and education as covariates to the final model did improve model fit (F(3, 785.08) = 13.27, P < .001), and both covariates were significantly related to aggression. A lower age (β =−.09, P < .001) and having a low (vs. high) education were related to higher levels of self-reported aggression (β =−4.3, P < .001), whereas a low (vs. medium) education was not (β =0.58, P = .39).

These results indicate that commission errors are not related to self-reported trait aggression in incarcerated individuals, see supplement 2.

Misconduct

A logistic regression analysis was performed for the incarcerated participants, including misconduct (yes/no) as dependent variable, commission errors, emotion condition, and their interaction as independent variables, and subject as within-subject factor. The results indicate that the full model did not improve model fit compared to an empty model (F(11, 1677.50) = 0.05, P = .99). Removing the non-significant interaction between commission errors and emotion condition from the model did not improve model fit (F(5, 1639.81) = 0.08, P = .99), see supplement 2. None of the individual predictors displayed a significant relationship with misconduct.

Adding age and education as covariates to the final model did improve model fit (F(3, 1679) = 11.62, P < .001), and both covariates were significantly related to misconduct. A lower age (OR = .98, P < .001) and having a low (vs. medium) education (OR = 0.49, P < .01) or low (vs. high) education (OR = 0.51. P= .005) were related to higher levels of misconduct.

These results indicate that commission errors are not related to whether or not incarcerated individuals were reported for misconduct.

Discussion

The concept of impulsivity is poorly defined, which may lead to vague conclusions, obscure existing relationships, and inconsistencies across studies, which severely hampers its usability within clinical (forensic) practice. Impulsivity is more likely to manifest in emotional situations, yet measurements of impulsivity rarely incorporate such emotional contingencies. Experimental psychological tasks enable the use of such emotional stimuli within the assessment of impulsivity and may provide additional information relevant within a criminal justice setting because they are less sensitive to socially desirable answers and more suitable for individuals across the literacy spectrum. Therefore, the current study investigates whether incarcerated individuals make more commission errors on an emotional Go/No-Go task compared to non-incarcerated controls, and whether performance is associated with increased trait aggression, and within-prison misconduct. The results indicate that incarcerated individuals indeed show impaired emotional RRI compared to non-incarcerated controls, irrespective of emotional condition. Within the incarcerated group, emotional RRI was not related to trait aggression or within-prison misconduct. These results therefore do not provide support for the use of emotional RRI for forensic assessment or within forensic psychiatric treatment in its current form.

The reported impaired emotional RRI in incarcerated men compared to non-incarcerated controls is in line with previous studies showing a general impairment in executive functioning in antisocial populations (Ogilvie et al., Citation2011) and with studies assessing emotional and non-emotional RRI in offender populations (Baliousis et al., Citation2019; Turner et al., Citation2018; Vedelago et al., Citation2019). Such differences are thought to be associated with the antisocial behavior exhibited by these groups but may also be related to myriad of other factors on which forensic populations are known to differ from their non-forensic counterparts (Semenza, Citation2018), including lower socioeconomic status, education, or IQ, higher levels of exposure to childhood abuse (Perry et al., Citation2018), and higher levels of traumatic brain injury (Jansen, Citation2020). These factors may offer an alternative explanation for differences in performance on experimental psychology tasks – including emotional RRI – between forensic and non-forensic groups (Stillman et al., Citation2016).

This explanation also fits our non-significant results regarding the association between emotional RRI and both aggression and misconduct within incarcerated individuals and corresponds with the inconclusive results from recent studies on the association between RRI and future offending or antisocial behavior (Aharoni et al., Citation2013; Brassard & Joyal, Citation2022; Fine et al., Citation2016; Zijlmans et al., Citation2021). If performance differences were not associated with the antisocial behavior exhibited by these groups one would not expect a (direct) relationship between (emotional) RRI and aggression or misconduct. It is possible that, for example, traumatic brain injury would increase both aggression (Jansen, Citation2020) and (emotional) RRI (Brassard & Joyal, Citation2022), but this does not have to indicate that (emotional) RRI would also increase aggression. Most previous studies assessing RRI and future offending or antisocial behavior do include relevant covariates; age (Zijlmans et al., Citation2021) or education (Fine et al., Citation2016). No covariates were included by Brassard and Joyal (Citation2022), whereas Aharoni et al. (Citation2013) included age at release, psychopathy, alcohol, and drug abuse as covariates but only revealed activity in the anterior cingulate – and not behavioral performance – to be predictive of future arrests.

Impaired emotional RRI could thus be a consequence of biosocial risk factors be known to this group, but this does not necessarily indicate that the criminal behavior committed by this group is also owing to deficits in emotional RRI. If true, this would severely hamper the usability of experimental psychological tasks for treatment and risk assessment in forensic populations. Future studies should assess whether impulsivity measured through experimental psychological tasks is associated with future offending or aggression, by adding covariates on which forensic populations are known to differ.

Another possible explanation for our results lies within the use of our specific stimuli and questionnaires. It is possible that emotional RRI is related to aggression and misconduct for different emotional facial expressions or for specific forms of aggression (e.g., reactive). We used neutral, happy, and fearful faces as stimuli, because previous studies have shown that forensic outpatients attribute hostility to fearful, angry, and disgusted facial expressions (Smeijers et al., Citation2017). Other studies, however, indicate that violent offenders have a stronger hostile attribution bias toward angry faces compared to fearful faces (Schönenberg & Jusyte, Citation2014; Wegrzyn et al., Citation2017). It is therefore possible that emotional RRI to angry faces would yield results, which are more in line with our hypotheses regarding aggression because (violent) offenders show a more pronounced deficit regarding angry facial expressions. This rationale could also explain the null results regarding the interaction between emotion type and group.

Additionally, studies using criminal records suggest differences in (non-emotional) response inhibition between affective versus instrumental aggression (Van de Kant et al., Citation2020), impulsive versus premeditated aggression (Zhang et al., Citation2017), and violent and nonviolent incarcerated individuals (Meijers et al., Citation2017). We did not collect information on the (index) crime of our incarcerated individuals, and we were therefore unable to assess whether they were convicted of a violent crime, although the incarcerated individuals did show higher levels of trait aggression compared to controls. Future studies might investigate the relationship between emotional RRI and aggression within a subgroup of detainees with high levels of reactive or impulsive aggression or with a subgroup of detainees convicted of a violent crime.

The incarcerated individuals included in this study were from the general prison population, excluding individuals currently incarcerated in maximum security wards. Within the Netherlands, these wards include wards for incarcerated terrorists, wards for incarcerated individuals who exhibit structural problematic behavior (including high levels of verbal and/or physical aggression), and wards for incarcerated individuals who are considered a very high risk for society and/or are considered a flight risk. It is likely that these wards house individuals who exhibit higher levels of RRI and may be more prone to aggression, and it is possible that a replication study with a sample of individuals from these wards would yield different results. Nevertheless, our current sample already reports higher levels of (trait) aggression compared to non-incarcerated controls, and we would expect to conform our hypotheses. If the expected association between emotional RRI and aggression or misconduct is only apparent in such extreme populations, this would considerably reduce the applicability of assessment and clinical practice.

Strengths and limitations

The current study adds to the body of the literature in several ways, since it assessed emotional RRI in a large(r) sample of incarcerated men, compared to previous studies within this field. It furthermore reports on both group differences in emotional RRI and is the first to assess the relationship between aggression and misconduct within a high-risk sample. There are, however, some limitations to consider.

Incarcerated men and non-incarcerated controls differed in age and education as well as in emotional RRI, and both age and education could therefore not be included as covariates within the analysis as it would violate ANCOVA assumptions (Field, Citation2009). Nevertheless, both a younger age and having a lower education are known characteristics of the (Dutch) incarcerated population, and therefore, the uncorrected analyses presented here possibly provide a good representation of the true difference between incarcerated individuals and non-incarcerated controls. Future studies should assess differences in emotional RRI using a well age- and education-matched control group.

In addition, misconduct was assessed using official disciplinary reports, recorded in the Central Digital Depot (CDD+) system of the Dutch Custodial Institutions Agency. A total of 17% of the detainees had at least one official disciplinary report (most of which were related to contraband), whereas 25% self-reported misconduct (Bosma et al., Citation2020), indicating that official data may underreport misconduct. Unfortunately, incarcerated men were not prompted to provide consent for combining self-reported misconduct, whereas they did consent by combining data from experimental psychology tasks with official reports. Future studies may assess whether different impulsivity assessments are related to self-reported misconduct.

Finally, we incorporated a trait aggression questionnaire because we were expecting that incarcerated individuals who show impaired emotional RRI would exhibit stable traits of aggressive behavior. It is possible that emotional RRI is more strongly associated with state, reactive, or impulsive aggression since research indicates that these types of aggression are more sensitive to stimuli (Farrar & Krcmar, Citation2006) .

Conclusion

The current study shows that incarcerated individuals perform making more commission errors on an emotional Go/No-Go task compared to non-incarcerated controls but also that impaired emotional RRI was not related to aggression and misconduct. The impairment, relative to non-offending controls, could therefore be related to other factors, including health and lifestyle risk factors, which are known to be compromised in incarcerated individuals and are related to neurocognitive functioning. Additionally, future studies should investigate more specific (reactive) aggressive subgroups, and whether results would vary when using angry faces within a similar paradigm since these may be more closely related to aggressive behavior.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Dutch Research and Documentation Centre (WODC) under Grant 2708 and 2914. The Life in Custody study was funded by the Dutch Custodial Institutions Agency (DJI) and Leiden University. The opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the DJI. The authors wish to thank the DJI for their support with the administration of the survey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aharoni, E., Vincent, G. M., Harenski, C. L., Calhoun, V. D., Sinnott-Armstrong, W., Gazzaniga, M. S., & Kiehl, K. A. (2013). Neuroprediction of future rearrest. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(115), 6223–6228. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1219302110

- Armstrong, T. A., Boisvert, D., Wells, J., & Lewis, R. (2020). Extending Steinberg’s adolescent model of risk taking to the explanation of crime and delinquency: Are impulsivity and sensation seeking enough? Personality and Individual Differences, 165, 110133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110133

- Baliousis, M., Duggan, C., McCarthy, L., Huband, N., & Völlm, B. (2019). Executive function, attention, and memory deficits in antisocial personality disorder and psychopathy. Psychiatry Research, 278, 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.05.046

- Bari, A., & Robbins, T. W. (2013). Inhibition and impulsivity: Behavioral and neural basis of response control. Progress in Neurobiology, 108, 44–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.06.005

- Barratt, E. S., Monahan, J., & Steadman, H. (1994). Impulsiveness and aggression. Violence and Mental Disorder: Developments in Risk Assessment, 10(61–79.

- Billen, E., Garofalo, C., Vermunt, J. K., & Bogaerts, S. (2019). Trajectories of self-control in a forensic psychiatric sample: Stability and association with psychopathology, criminal history, and recidivism. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 46(9), 1255–1275. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854819856051

- Bootsman, F. (2019). Neurobiological intervention and prediction of treatment outcome in the juvenile criminal justice system. Journal of Criminal Justice, 65, 101554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2018.05.001

- Bosma, A. Q., van Ginneken, E. F., Sentse, M., & Palmen, H. (2020). Examining prisoner misconduct: A multilevel test using personal characteristics, prison climate, and prison environment. Crime and Delinquency, 66(4), 451–484. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128719877347

- Brassard, M. L., & Joyal, C. C. (2022). Predicting forensic inpatient violence with odor identification and neuropsychological measures of impulsivity: A preliminary study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 147, 154–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.01.021

- Burt, C. H. (2020). Self-control and crime: Beyond Gottfredson & Hirschi’s theory. Annual Review of Criminology, 3(1), 43–73. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-criminol-011419-041344

- Buss, A. H., & Perry, M. (1992). The aggression questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(3), 452. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.452

- Cheng, J., O’Connell, M. E., & Wormith, J. S. (2019). Bridging neuropsychology and forensic psychology: Executive function overlaps with the central eight risk and need factors. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 63(4), 558–573. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X18803818

- Cyders, M. A. (2015). The misnomer of impulsivity: Commentary on “choice impulsivity” and “rapid-response impulsivity” articles by Hamilton and colleagues. Personality Disorders, 6(2), 204–220. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000123

- Cyders, M. A., & Coskunpinar, A. (2011). Measurement of constructs using self-report and behavioral lab tasks: Is there overlap in nomothetic span and construct representation for impulsivity? Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 965–982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.06.001

- Den Bak, R. R., Popma, A., Nauta-Jansen, L., Nieuwbeerta, P., & Jansen, J. M. (2018). Psychosociale criminogene factoren en neurobiologische kenmerken van mannelijke gedetineerden in Nederland. doi: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12832/2273.

- Eben, C., Billieux, J., & Verbruggen, F. (2020). Clarifying the role of negative emotions in the origin and control of impulsive actions. Psychologica Belgica, 60(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb.502

- Farrar, K., & Krcmar, M. (2006). Measuring state and trait aggression: A short, cautionary tale. Media Psychology, 8(2), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532785xmep0802_4

- Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS. Sage publications.

- Fine, A., Steinberg, L., Frick, P. J., & Cauffman, E. (2016). Self-control assessments and implications for predicting adolescent offending. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(4), 701–712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0425-2

- Forrest, W., Hay, C., Widdowson, A. O., & Rocque, M. (2019). Development of impulsivity and risk‐seeking: Implications for the dimensionality and stability of self‐control. Criminology, 57(3), 512–543. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12214

- Gillespie, S. M., Brzozowski, A., & Mitchell, I. J. (2018). Self-regulation and aggressive antisocial behaviour: Insights from amygdala-prefrontal and heart-brain interactions. Psychology, Crime & Law, 24(3), 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2017.1414816

- Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press.

- Hamilton, K. R., Littlefield, A. K., Anastasio, N. C., Cunningham, K. A., Fink, L. H., Wing, V. C., & Potenza, M. N. (2015). Rapid-response impulsivity: Definitions, measurement issues, and clinical implications. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 6(2), 168. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000100

- Hamilton, K. R., Mitchell, M. R., Wing, V. C., Balodis, I. M., Bickel, W. K., Fillmore, M., & Moeller, F. G. (2015). Choice impulsivity: Definitions, measurement issues, and clinical implications. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 6(2), 182. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000099

- Heymans, M. W., & Eekhout, I. (2019). Applied Missing Data Analysis with SPSS and (R)Studio. https://bookdown.org/mwheymans/bookmi/

- Hornsveld, R. H., Muris, P., Kraaimaat, F. W., & Meesters, C. (2009). Psychometric properties of the aggression questionnaire in Dutch violent forensic psychiatric patients and secondary vocational students. Assessment, 16(2), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191108325894

- Jansen, J. M. (2020). Traumatic brain injury and its relationship to previous convictions, aggression, and psychological functioning in Dutch detainees. Journal of Forensic Psychology Research and Practice, 20(5), 395–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/24732850.2020.1755923

- Ling, S., Umbach, R., & Raine, A. (2019). Biological explanations of criminal behavior. Psychology, Crime & Law, 25(6), 626–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2019.1572753

- Meier, N. M., Perrig, W., & Koenig, T. (2012). Neurophysiological correlates of delinquent behaviour in adult subjects with ADHD. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 84(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2011.12.011

- Meijers, J., Harte, J. M., Meynen, G., & Cuijpers, P. (2017). Differences in executive functioning between violent and non-violent offenders. Psychological Medicine, 47(10), 1784–1793. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717000241

- Mellentin, A. I., Dervisevic, A., Stenager, E., Pilegaard, M., & Kirk, U. (2015). Seeing enemies? A systematic review of anger bias in the perception of facial expressions among angerprone and aggressive populations. Aggression and Violent Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 25(373–383. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.09.001.

- Meule, A. (2017). Reporting and interpreting task performance in go/no-go affective shifting tasks. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 701. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00701

- Ogilvie, J. M., Stewart, A. L., Chan, R. C., & Shum, D. H. (2011). Neuropsychological measures of executive function and antisocial behavior: A meta‐analysis. Criminology, 49(4), 1063–1107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2011.00252.x

- Perry, B. D., Griffin, G., Davis, G., Perry, J. A., & Perry, R. D. (2018). The impact of neglect, trauma, and maltreatment on neurodevelopment: Implications for juvenile justice practice, programs, and policy. In A. R. Beech, A. J. Carter, R. E. Mann, & P. Rotshtein (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell handbook of forensic neuroscience (pp. 815–835). Wiley Blackwell.

- Popma, A., & Raine, A. (2006). Will future forensic assessment be neurobiologic? Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 15(2), 429–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2005.11.004

- Puiu, A. A., Wudarczyk, O., Goerlich, K. S., Votinov, M., Herpertz-Dahlmann, B., Turetsky, B., & Konrad, K. (2018). Impulsive aggression and response inhibition in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and disruptive behavioral disorders: Findings from a systematic review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 90, 231–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.04.016

- Schönenberg, M., & Jusyte, A. (2014). Investigation of the hostile attribution bias toward ambiguous facial cues in antisocial violent offenders. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 264(1), 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-013-0440-1

- Semenza, D. C. (2018). Health behaviors and juvenile delinquency. Crime and Delinquency, 64(11), 1394–1416. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128717719427

- Smeijers, D., Rinck, M., Bulten, E., van den Heuvel, T., & Verkes, R. J. (2017). Generalized hostile interpretation bias regarding facial expressions: Characteristic of pathological aggressive behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 43(4), 386–397. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21697

- Steinberg, L., Albert, D., Cauffman, E., Banich, M., Graham, S., & Woolard, J. (2008). Age differences in sensation seeking and impulsivity as indexed by behavior and self-report: Evidence for a dual systems model. Developmental Psychology, 44(6), 1764. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012955

- Stillman, C. M., Cohen, J., Lehman, M. E., & Erickson, K. I. (2016). Mediators of physical activity on neurocognitive function: A review at multiple levels of analysis. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10, 626. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00626

- Tittle, C. R., Ward, D. A., & Grasmick, H. G. (2003). Self-control and crime/deviance: Cognitive vs. behavioral measures. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 19(4), 333–365. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOQC.0000005439.45614.24

- Tottenham, N., Tanaka, J. W., Leon, A. C., McCarry, T., Nurse, M., Hare, T. A., Marcus, D. J., Westerlund, A., Casey, B. J., & Nelson, C. (2009). The NimStim set of facial expressions: Judgments from untrained research participants. Psychiatry Research, 168(3), 242–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.05.006

- Tuente, S. K., Bogaerts, S., & Veling, W. (2019). Hostile attribution bias and aggression in adults-a systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 46, 66–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2019.01.009

- Turner, D., Laier, C., Brand, M., Bockshammer, T., Welsch, R., & Rettenberger, M. (2018). Response inhibition and impulsive decision-making in sexual offenders against children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127(5), 471. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000359

- Van Buuren, S., & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. (2011). Mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 45, 1–67. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v045.i03.

- Van de Kant, T. W., Boers, S. F., Kempes, M., & Egger, J. I. M. (2020). Neuropsychological subtypes of violent behaviour: Differences in inhibition between affective and instrumental violence. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry, 5, 158. doi: 10.35248/2475-319X.19.5.158

- Vazsonyi, A. T. M., Kelley, J., & L, E. (2017). It’s time: A meta-analysis on the self-control-deviance link. Journal of Criminal Justice, 48, 48–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2016.10.001

- Vedelago, L., Amlung, M., Morris, V., Petker, T., Balodis, I., McLachlan, K., & MacKillop, J. (2019). Technological advances in the assessment of impulse control in offenders: A systematic review. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 37(4), 435–451. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2420

- Wegrzyn, M., Westphal, S., & Kissler, J. (2017). In your face: The biased judgement of fear-anger expressions in violent offenders. BMC Psychology, 5(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-017-0186-z

- Wright, L., Lipszyc, J., Dupuis, A., Thayapararajah, S. W., & Schachar, R. (2014). Response inhibition and psychopathology: A meta-analysis of go/no-go task performance. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123(2), 429. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036295

- Zhang, Z., Wang, Q., Liu, X., Song, P., & Yang, B. (2017). Differences in inhibitory control between impulsive and premeditated aggression in juvenile inmates. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11, 373. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00373

- Zijlmans, J., Marhe, R., Bevaart, F., Van Duin, L., Luijks, M. J. A., Franken, I., & Popma, A. (2021). The predictive value of neurobiological measures for recidivism in delinquent male young adults. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 46(2), e271–e280. https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.200103

- Zuur, A. F., Ieno, E. N., & Elphick, C. S. (2010). A protocol for data exploration to avoid common statistical problems. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 1(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210X.2009.00001.x