ABSTRACT

Background

Injury perceptions and related risk-mitigating interventions are context-dependent. Despite this, most injury surveillance systems are not context-specific as they do not integrate end-users perspectives.

Purpose

To explore how Maltese national team football players, coaches, and health professionals perceive a football-related injury and how their context influences their perceptions and behaviours towards reporting and managing a football injury.

Methods

13 semi-structured interviews with Maltese female and male national team football players (n = 7), coaches (n = 3), and health professionals (n = 3) were conducted. Data were analysed using thematic analysis.

Results

Three themes were identified: (1) How do I perceive an injury? Consisted of various constructs of a sports injury, yet commonly defined based on performance limitations. (2) How do I deal with an injury? Encapsulated the process of managing the injury (3) What influences my perception, reporting and management of an injury? Comprised personal and contextual factors that influenced the perception and, consequently, the management of an injury.

Conclusion

Performance limitations should be used as part of future injury definitions in injury surveillance systems. Human interaction should be involved in all the processes of an injury surveillance framework, emphasising its active role to guide the injury management process.

Introduction

As part of the four-step injury prevention sequence,(Van Mechelen et al. Citation1992) injury surveillance systems (ISS) have been developed and implemented by sporting organisational bodies.(Junge et al. Citation2004, Citation2011; Yoon et al. Citation2004; Junge and Dvorak Citation2007, Citation2015; Walden et al. Citation2007; Hägglund et al. Citation2009; Stubbe et al. Citation2015; Klein et al. Citation2019; Esteve et al. Citation2020) Such systems aim to describe the injury problem and provide the means to develop injury risk mitigation measures to protect athlete health.(Bahr et al. Citation2020) The definition of a sports injury has been considered a critical factor in injury surveillance studies.(Clarsen and Bahr Citation2014) Most consensus statements on sports injury epidemiology advocate for consistency in studies through the use of standard injury definitions. (Fuller et al. Citation2006, Citation2007; Pluim et al. Citation2009; Timpka et al. Citation2014a; Mountjoy et al. Citation2016; Orchard et al. Citation2016; Bahr et al. Citation2020) For example, in football, the consensus statement emphasises the use of standard injury definitions, namely: (1) any physical complaint, (2) medical attention and (3) time-loss. (Fuller et al. Citation2006)

From an epidemiological perspective, the use of standard injury definitions remains essential for reliable reporting of injuries, allowing comparisons of the magnitude of the injury problem between contexts.(Hägglund et al. Citation2005; Werner et al. Citation2019; Ekstrand et al. Citation2019a) Yet, to reduce injury risk through context-driven strategies, (Bolling et al. Citation2018) standard injury definitions proposed by researchers, may not align with the stakeholders’ injury perception (players, coaches and health professionals). (Bolling et al. Citation2018; Shrier Citation2020) Research within the sports injury prevention field has revealed that injury perception is context-dependent. (Bolling et al. Citation2018) Accordingly, to address the injury problem in context, an ISS requires an injury definition that aligns with the stakeholders’ perception of an injury. (Bolling et al. Citation2018; Shrier Citation2020)

Alongside the injury definition, there is also a need to consider when injuries are or are not reported. The number of reported injuries is influenced by the stakeholders’ socio-ecological factors concerning decisions taken when reporting and managing an injury. (Hammond et al. Citation2011; Ekegren et al. Citation2014, Citation2016) For example, in football, it has been suggested that injuries may be underreported to avoid participation restrictions. (Hammond et al. Citation2014; Nilstad et al. Citation2014) In this sense, socio-ecological factors will affect the accuracy of reported data due to under or overreporting, affecting how an injury is managed. (Hammond et al. Citation2011) In this respect, understanding and ingraining socio-ecological factors into an ISS operationalisation will enhance its value for stakeholders.(Hammond et al. Citation2011; Bolling et al. Citation2018)

Qualitative research can address these issues, as data is collected based on stakeholders’ reports on their meaning, experiences, and practices. (Bekker et al. Citation2020) Therefore, this study aimed to explore (i) how players, coaches, and health professionals perceive a football-related injury and (ii) how their context influences perceptions and, consequently, decisions taken when reporting and managing an injury. As the consensus statement has largely neglected subjective approaches to developing ISS, (Fuller et al. Citation2006) understanding stakeholders’ perspectives will provide new insights to develop context-specific ISS. Data obtained from context-specific ISS will provide stakeholders with strategies to deal with context-specific injury-related issues in real time. After all, they are the end-users of the ISS.

Methods

Design

An exploratory qualitative study was conducted to identify the stakeholders’ perceptions of a football injury and how they deal with injury in their context. The research philosophy of pragmatism underpinned the present study. Pragmatism acknowledges that there are multiple realities and different ways of interpreting reality. Understanding this reality provides a foundation to create practical knowledge for stakeholders. (Morgan Citation2014)

Research setting and participant recruitment

This study was undertaken at the Malta Football Association (MFA), responsible for the Maltese national football teams. Participants included football players, and their support staff, composed of national team coaches (head coaches and physical conditioning coaches) and health professionals (medical doctors and physiotherapists) forming part of the National football senior female and the Under-21 male squads. Based on maximum variation criteria, (Palinkas et al. Citation2015) we included coaches and medical staff from national football teams and various ages and football experience. To limit the researcher’s influence on the player’s participation decision, each head coach was instructed to select five players from their team, aiming for diversity in football experience, ages, professional status and football clubs. Coaches provided potential participants with an information letter about the study. Those who expressed interest were asked to contact the main researcher directly. Participants provided written and oral informed consent before the interview. Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the MFA technical director, and the Cardiff Metropolitan University’s Ethics Committee approved the study (PGR-2573).

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were carried out by the principal researcher (SV) following a flexible interview guide. This method provided in-depth insight into the stakeholders’ perceptions and experiences about injuries, allowing specific areas to be addressed while providing means to probe for further detail.(Sparkes and Smith Citation2014) The interview questions () were developed by the primary researcher (SV), who made use of similar questions from the study about sports injury perception, (Bolling et al. Citation2018) knowledge from literature about decision-making in reporting injuries, (Roderick et al. Citation2000; Hammond et al. Citation2014) and further informed by the researcher’s experience within the field. Questions were further developed through discussions with the research team (CB, EV, IM). Interviews allowed for probing, aimed at obtaining a more detailed description and in-depth understanding of the participants’ experiences of injuries. An example of probe included ‘Can you tell me about a past injury experience and how you dealt with it?’. To enhance rigour, interview questions were tested in two pilot interviews with a player and a physical trainer. Following the pilot interviews, minor changes to the wording of two questions were implemented to improve clarity. These pilot interviews were not included in the study. (Malmqvist et al. Citation2019)

Table 1. Interview guide.

All the interviews were conducted through online videoconferencing using Skype during April 2020 and lasted on average 36 minutes (range: 20–52 minutes). The interviews were conducted in Maltese and English, according to the preferred language of the participant.

After interviewing 11 stakeholders, including multiple stakeholders to cover a wide range of perspectives, responses and ideas became repetitive. To ensure no salient information was missed, two more interviews (a total of 13 interviews) were conducted, with new information elicited, indicating data saturation. (Saunders et al. Citation2018) The thirteen participants (males: n = 9; females: n = 4) included seven players, three coaches (head coaches and physical trainers) and three health professionals (medical doctors and physiotherapists). To protect participants’ anonymity, their demographical data is presented at a group level only ().

Table 2. Demographic data of the participants.

Data analysis

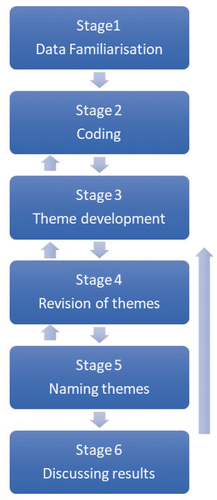

Thematic analysis is a qualitative technique that unearths rich and complex data accounts, allowing for individual and social interpretations of data. A six-stage thematic analysis (Braun et al. Citation2017) with a ‘codebook’ approach was utilised to analyse the data (). (Braun and Clarke Citation2020) This analytic approach provides flexibility in how data collection is undertaken, making it suitable for the pragmatic approach used in this research.

Figure 1. The process of thematic analysis involving six interactive phases (adapted from Braun & Clarke, 2006).

This process involved a measure of recursion, with stages overlapping and interacting in ways that allowed for rigorous data analysis. The following six steps were involved in the process: 1) Interviews were initially transcribed verbatim by the principal researcher (SV) and entered into NVivo QSR 12.0 (QSR International Pty Ltd., Doncaster, Victoria, Australia). Transcripts were repeatedly read for familiarisation. 2) Two researchers (SV, CB) independently open-coded four transcripts through an inductive approach. Divergences of the coding were discussed until consensus was reached. At this stage, themes started to develop, through inductive data engagement and discussions between both researchers. The primary researcher (SV) then coded the remaining nine transcripts, followed by a meeting with CB, to discuss the new codes. 3) Codes were allocated into broader categories, where overarching sub-themes and global themes were further developed and refined through repetitive synthesising, interpretation, and theorising. 4) The analysis was discussed during two consensus meetings with the other two researchers (EV, IM) who were not familiar with the interview content. 5) Global themes and sub-themes were further developed and named. Figures indicating interconnections between the themes, sub-themes and basic themes were developed using the full data set within each theme and according to how these were conceptualised by the research team during the analysis process. Based on the participants’ availability during two national team training camps, the main researcher (SV) presented the developed themes and their relationships to ten of the participants (four players, three coaches and three health professionals) to confirm that the results reflected their perceptions and experiences. All participants agreed that the findings resonated with their experiences. 6) A report was produced, with quotes illustrating the main thematic findings. Quotes in Maltese were translated into English by SV and checked by an academic translator.

To enhance data trustworthiness, several measures were employed.(Smith and McGannon Citation2017) Taking the reflexivity concept, the main researcher (SV) was conscious that his background as an ‘insider’ within the research setting might have influenced the research process. To minimise this influence, data coding was done independently by two different researchers (SV, CB). Confirmability was enhanced through discussion of findings with the other two members of the research team (EV, IM), who provided a degree of neutrality to our findings. Member checking was undertaken to increase the credibility and dependability of our findings.

Results

Key themes

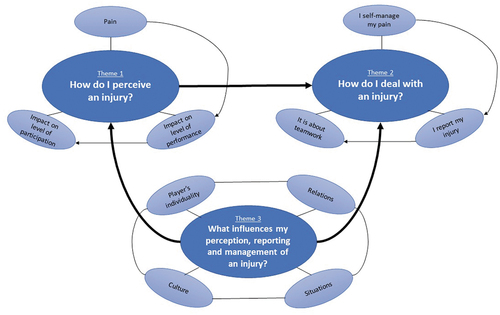

Three main themes and their associated sub-themes were identified from the interviews: (1) how do I perceive an injury? (2) how do I deal with an injury? and (3) what influences my perception, reporting and management of an injury? ()

Figure 2. Main thematic map illustrating the relationships between themes and their associated sub-themes. Participants highlighted their definition of a football injury, mainly in terms of consequences on pain, performance and participation (theme 1). Their perception of an injury influenced how they approached injury management. When in pain, players self-managed their symptoms before reporting them. injury reporting was based on the perceived pain severity, with injury management becoming a shared responsibility between different members of the team (theme 2). Yet, various interacting modulators, namely, player, relational, situational, and cultural related factors, modulate injury perception and, consequently, the way players manage and report their injury (theme 3).

How do i perceive an injury?

‘it’s a complex thing that we can continue to debate about’ (physical trainer coach)

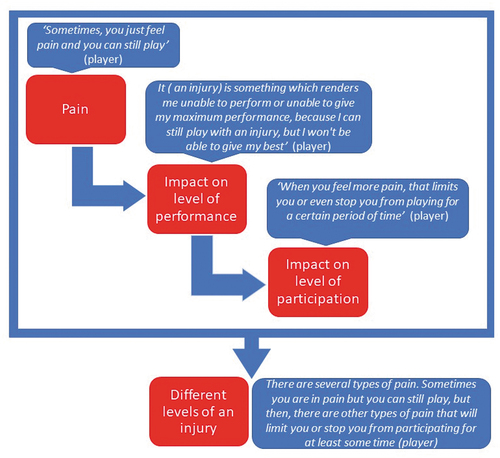

Participants described a football injury based on three main aspects: (i) pain, (ii) impact on optimal performance, and (iii) impact on the level of participation (; ). These aspects were described as different levels of an injury. Yet, on further questioning, most stakeholders expressed that players are injured when their pain hinders their performance. Therefore, pain, modification in training load and absence from participation were acknowledged as subcomponents of an injury, especially to gauge its severity.

Table 3. The theme of injury preception, presented with its subthemes, basic themes and supportive quotes

(1) Pain

Pain was considered normal in football, with some players stating that they never felt pain-free when playing. Pain was described in terms of discomfort rather than in terms of an injury, with ‘dead-legs’ and ‘muscle soreness’ considered examples.

(2) Impact on optimal performance

Participants highlighted that ‘real pain’ is considered as an injury when severe enough to impact performance. For players, this meant that they perceived themselves to be injured when they were participating with pain, but could not give their ‘100%’. When referring to ‘100%’, this was in terms of their maximum performance during training sessions and competitive matches. Also perceived by coaches, performance hindrance is considered as a deterrent to the team success.

(3) Impact on the level of participation

Some of the participants referred to injuries in terms of their consequences on participation in training and matches. Once no longer able to perform due to the high pain severity, players modify the training load or do not participate in training and/or competition to accommodate their severe symptoms.

Figure 3. Injury definition diagram, supported by quotes from participants. This figure describes an injury as a process, with performance limitation described as the main indicator of a football-related injury, while pain and impact on the level of participation are described as subcomponents of an injury within this process.

How do i deal with an injury?

‘ I have to take care of my injury’ (player)

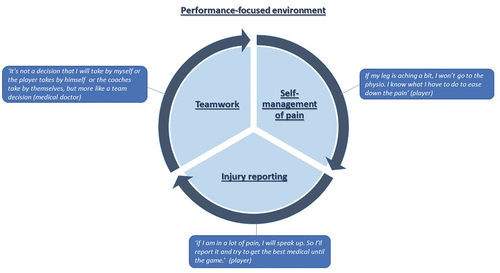

Participants described how their injury perception influenced the injury management process. Players manage their pain before reporting. In reporting injuries, a team approach is considered essential to manage an injury (; ).

Table 4. The theme of injury management, presented with its subthemes, basic themes and supportive quotes

(1) I self-manage my pain

When in pain, players reported how they self-manage their injury. Self-management measures range from managing the training load to managing symptoms. Some players acknowledged that previous experiences with injuries is essential to understanding the fine line between being in pain and being injured.

(2) I report my injury

The decision to report an injury is often based on the perceived pain severity, with players seeking medical treatment to minimise pain levels, especially when it affects their performance or participation.

(3) It is about teamwork

Participants acknowledged that injury risk acceptance is part and parcel of participation at the elite football level. Thus, to seek medical management in reporting an injury, players continue to play with pain as long as they can perform. In this respect, a team decision is considered an essential approach in the management of injury risks. This is enhanced through communication between players and support staff and collaboration between the national team and club staff throughout the season. Intervening at the earliest stages of an injury is essential to mitigate the possible negative impact injuries can have on a player’s optimal performance and participation.

Figure 4. The injury management process, supported by quotes from participants. This figure represents the process of dealing with an injury, with players self-managing their pain before reporting it. In reporting an injury, based on its severity, the interaction between all stakeholders is essential in managing the injury.

What influences my perception, reporting and management of an injury?

‘but then, you have to take everything into consideration, because there are many factors, like the importance of an upcoming match, which affect my decision and whether I should take the risk’ (player)

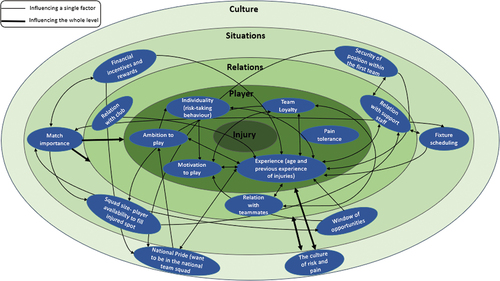

All participants mentioned various contextual factors at different levels, ranging from player to cultural factors, that modulate injury perception (theme 1) and the way an injury is reported and managed (Theme 2; ).

Table 5. The theme of modulating factors of injury perceptions and injury management, presented with its subthemes, basic themes and supportive quotes

(1) The influence of culture

Regarding factors influencing an injury’s perception, there were suggestions of a wider cultural norm of injury risk acceptance and a norm relating to playing with injuries entrenched in a ‘macho’ sporting environment. The cultural influence was mentioned as a prime modulator of the majority of situational, relation and individual factors, reinforcing this cultural norm. This was especially noted when players are called to play for the National team, with players pushing through the pain to participate.

(2) The influence of situations

Injury perceptions and decision-making towards injury management are also modulated by unstable situational moderators occurring across the football season. Modulators included: player’s sense of security of their position within the first team, availability of players to fill the injured spot, financial incentives, window of opportunities for national team selection, fixture scheduling and forthcoming matches with particular importance. These factors were often mentioned in relation to each other, with match importance, acting as a prime influencer of other factors in modulating injury perception and consequently to ‘push through the pain.’

(3) The influence of relations

It was discussed how the players’ relations with their club, support staff, and teammates act as modulators of injury perception, influencing the injury management process. Some players expressed that they perceive no pressure, for instance, to participate in important matches when injured due to the existing open relationships with their support staff and teammates. In contrast, because of the prevailing cultural norm of playing with pain, others mentioned how they perceive pressure to participate, with a risk of worsening their injury. To this end, participants expressed how a trusting relationship between players and support staff is necessary for a risk-taking environment, where players can safely report and manage their injuries.

(4) The influence of the player’s individuality

Personal factors were also mentioned as critical modulators of the player’s view towards an injury. Both the player’s motivation and the ambition to play, especially for the national team, act as a strong modulator of ones own injury perception. Others mentioned their loyalty towards the team as a reason for competing injured. The decision to compete with injuries is also influenced by one’s personality, reflected in risk-taking behaviour and pain tolerance. Yet, it was acknowledged that age and previous experience with injuries modulate most of the above factors. Indeed, experienced players highlighted how, through the experience of their previous injuries, their perceptions of injuries have changed over time. In this sense, they recounted how they were more accountable for their health.

Interaction of factors

Although the above-modulating factors were described separately, various factors at multiple levels were described to be interacting with each other. Accordingly, the dynamicity and fluidity of interactions between these factors during different times and situations influenced and modulated the player’s injury perception, and the way injuries are managed ().

Figure 5. The multi-level map reflects the personal and socio-ecological levels to describe individual factors and their interrelation. The dynamicity and fluidity of interactions between these factors during different times and situations influence how a player perceives and manages an injury. Starting at the centre of the map (injury) and moving distally, the perception of an injury is modulated by 1) individual (player) factors including demographic and psychological related factors; 2) player’s relations with club, support staff and teammates; 3) situational factors across the football season, and the 4) broad football-related cultural messages.

Discussion

This study sought to explore the Maltese National football team stakeholders’ perception of a football injury and how their context influenced this perception, reporting and management. A football injury was defined based on pain, its impact on optimal performance, and its impact on participation level. The perception of injury influenced injury management, with players self-managing their symptoms before reporting them. Reporting an injury, was considered essential for its effective management to keep performing. This process is enhanced through communication and collaboration between stakeholders. Yet, various interconnected personal and contextual factors influenced the perception, reporting and management of an injury.

An injury is an individualised process – yet, it is all about performance

Based on the football consensus statement’s recommendations, (Fuller et al. Citation2006) to date, football injury epidemiological studies have promoted a reductionist view of the injury problem.(Junge et al. Citation2004, Citation2011; Yoon et al. Citation2004; Hägglund et al. Citation2005, Citation2009; Junge and Dvorak Citation2007, Citation2015; Walden et al. Citation2007; Stubbe et al. Citation2015; Klein et al. Citation2019; Werner et al. Citation2019; Ekstrand et al. Citation2019a; Esteve et al. Citation2020) From this perspective, an injury is viewed as a dichotomous concept, with players classified as ‘injured’ or ‘not injured’ based on their availability for participation. Yet, for the study’s participants, a football injury can be conceptualised as a process, with the constructs of pain, performance hindrance and impact on participation intimately interlinked. The OSTRC (Oslo Trauma Research Centre) (Clarsen et al. Citation2020) questionnaire attempts to provide a comprehensive view of an injury by measuring the consequence of an injury based on four constructs, described by participants in this study. Thus, within this context, individualised information gathered from the OSTRC questionnaire enables monitoring of the players’ injury process, facilitating early management of an injury, thereby limiting its consequence on performance and participation.

The injury perception is also closely tied to the player’s context, with an injury considered a dynamic and temporal concept, driven by socio-ecological factors. This reinforces claims that injuries and their risk should be considered through a ‘complexity lens’, by accounting for the interaction between personal and contextual factors.(Wiese-Bjornstal Citation2010; Truong et al. Citation2020) Since a football injury is contextually modulated and therefore a complex phenomenon, injury epidemiological research within this context needs to embrace this complexity. In light of this, a paradigm shift in explaining a football injury from a biomedical, time-loss explanation towards one reflecting a socio-ecological framework is required. This framework considers the person’s level of functioning as a dynamic interaction between the injury, the personal and contextual factors. (World Health Organisation Citation2001; Timpka et al. Citation2014b) For instance, for the same injury, a player may perceive himself or herself injured during the pre-season due to no important forthcoming matches. In contrast, such injury perception may be altered due to an important upcoming match at the end of the season. It is, therefore, conceivable that in viewing the notion of an injury as a process, players are reporting the outcome of a process that is influenced by the dynamic socio-ecological context. In this respect, the outcome reinforces the notion of the ‘individualisation’ of a football injury and how it is experienced within this context. (Wiese-Bjornstal Citation2010; Truong et al. Citation2020)

Participants commonly defined an injury based on its consequences on performance as an individualised process. This is in line with what has been described in other high-performance sporting contexts. (Bolling et al. Citation2018, Citation2020) Within this context, the players’ focus is on achieving peak performance and increasing team success chances. Indeed, the influence of injuries on individual and team performance has already been documented. (Eirale et al. Citation2013; Hägglund et al. Citation2013; Raysmith and Drew Citation2016; Drew et al. Citation2017) Identifying an injury definition that aligns with the stakeholder’s perceptions has practical and real-world significance.(Shrier Citation2020) Monitoring performance-limiting injury problems through the self-reported impact of an injury on performance provide means to develop context-driven injury risk-mitigating strategies to reduce performance-limiting injuries. Ultimately, Maltese National team players play football to perform, and so, focusing on maximising performance may help improve player and coach’s compliance with injury risk mitigation measures. (West et al. Citation2020)

Injury management – it is a process

Want to empower players? Guide and educate them to self-manage their injuries

There is little acknowledgement of athletes’ perception of injuries within the sports medicine field and, consequently, experience in managing injuries. It is generally assumed that athletes are passive recipients who are continually dependent on health practitioners to manage their injuries. (Ardern et al. Citation2016) Our findings indicate that players manage their symptoms before reporting them. This behaviour, influenced by the way pain is perceived, was described as a learning process, with players implementing self-management strategies that they had learnt over time through experiencing injuries.

If injury risk mitigation and management is a learning process for the player, this highlights an untapped resource, that needs to be drawn upon and utilised within this context. Considering an injury as a process, influenced by the socio-ecological context, clinicians should adopt an individualised approach. In reporting an injury, clinicians should situate the player within the social context, (Truong and Whittaker Citation2020) guiding and supporting them through their own self-management decisions. As sports injury prevention is a learning process, (Bolling et al. Citation2020) educating players in dealing with injuries empowers them and enhances their sense of self-efficacy in self-management. (Wierike et al. Citation2013) Moreover, given previous experience is a prime modulator of injury perception and management, younger players can be supported by experienced players leading them by example, enhancing the process of self-management.

Want to improve injury reporting? Build and develop trustworthy relations with each player!

Our findings indicate that injured players possess a great deal of power in deciding to report their injuries, with this decision influenced by a multitude of socio-ecological factors. In this regard, socio-ecological factors in reporting decisions become a fundamental issue in the study of epidemiology. (Corman et al. Citation2019) Self-reported methods are dependent on honest information. However, identification of whether athletes report the truth in self-reported measures is still a challenge. A lack of honesty may threaten the effectiveness of the ISS, with possible underestimation of injury outcomes (e.g. incidence and severity). Given that attempts have concentrated on altering the athlete’s injury reporting behaviour through educating resources with limited success, (Barboza et al. Citation2017; Bromley et al. Citation2018) there is a need to revisit how Maltese injured players conceptualise disclosure in their context is required.

Modifying all socio-ecological factors that influence injury reporting is a big task. (Ivarrson et al. Citation2019) Still, based on the current findings, within a culture of injury risk acceptance, a trusting relationship is necessary for Maltese players to report their injuries. This trusting relationship is based upon open communication between the player and support staff. From this perspective, the clear identification of socio-ecological factors and their use within the injury management process could represent a novel approach in athlete-centred care. For instance, in light of masking injuries, support staff should open safe communication lines to foster supportive interpersonal relationships with their players. (Burns et al. Citation2019) As relationships develop, honesty in injury reporting becomes a powerful attribute to gauge a player’s injury risk. This is a fundamental component to enhance epidemiological data quality, thereby promoting effective player care. (Barboza et al. Citation2017; Bromley et al. Citation2018)

Want to optimise player performance? As one team, pull the rope in the same direction!

Participants acknowledged that injury risk acceptance is part and parcel of participation within this high-performance context. The multiple socio-ecological factors fuel this risk-taking behaviour. Accordingly, the benefits of teamwork and communication between team stakeholders during the injury risk management decision-making process were highlighted. Evidence suggests that consistent internal communication in the team plays a critical role in mitigating the risk of injuries. (McCall et al. Citation2016; Ekstrand et al. Citation2019b) To this end, implementing an ISS within this context should promote communication by focusing on the shared goal of performance optimisation. This enables a uniform narrative that delivers clear and consistent messages, enhancing the process of shared-decision making. (Verhagen and Bolling Citation2015) The aim is to optimise player care through individualised adjustments to the injury management process, thereby maximising the player’s performance. (Drew et al. Citation2017) Ultimately, this approach can be visualised as a partnership between support staff and the player, enhancing the player’s self-management process.

How do we achieve this? – A call for action

The above-discussed aspects indicate that optimising players’ performance necessitates a supportive environment in which they are guided in managing their injury, they feel safe in reporting their injury, and where shared-decision making is the normal routine practice. Creating this environment within this context is not a passive task. Rather, it calls for support staff to upskill their leadership skills, communicate effectively, build trustworthy relations, and promote positive group dynamics. (Tayne et al. Citation2020; Thornton Citation2020; Verhagen et al. Citation2020) After all, players are not machines waiting to be ‘serviced’ but social beings who strive to be healthy in a context where optimal performance is rewarded. (Truong and Whittaker Citation2020; Verhagen et al. Citation2020)

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is that it employed triangulation of data sources, including players, coaches, and health professionals, to cover a wide range of perceptions. It also included both males and females, providing means to view sports injuries from both sexes. Also, the sample’s nature can be considered a strength of this study, as national football team stakeholders are an understudied population within the sports injury prevention field. On another note, only perceptions from stakeholders of the Maltese national football were included. While this may be considered as a strength of this study, as the implications serve to enhance the practices of the stakeholders, the transferability of the encountered themes to other contexts has to be made cautiously. The wide range of perceptions and experiences with their thick and rich description allows the reader to determine these findings’ transferability to their contexts.

Conclusion

Based on the current findings, the study provides novel insights into the development and implementation of an ISS within the context of the Maltese national football team. An ISS should not be seen as an end in itself but as an active process, readily applying the aforementioned strategies. The inclusion of perceived performance outcome measures in implementing an ISS provides a nuanced view of how to monitor injury outcomes. This provides measures to develop context-driven injury risk mitigation measures focusing on performance optimisation. This study also provides insights into how perceived injuries are reported and managed, acknowledging the influence of socio-ecological factors on these processes. In considering an injury as a process influenced by the socio-ecological context, support staff play an essential role in (i) guiding, supporting and empowering players in their process of injury management; (ii) fostering trusting-relationship with players to encourage injury reporting; and (iii) communicating and collaborating with all involved stakeholders, allowing for shared-decision making in mitigating injury risks in real-time. Therefore, this process necessitates ongoing interaction between all stakeholders to optimise players’ injury risk mitigation and management.

Author contributions

All authors assisted in conceiving and designing the study: SV, IM, EV and CB. Data Collections: SV. Data Analysis: SV and CB. Data review and interpretation: all authors. Manuscript preparation, revisions and approval for the final version: all authors

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Malta Football Association for providing the chance to conduct the study with its own stakeholders and Ms. Alessia Schembri for providing assistance in the translation of quotes from Maltese to English. This work was supported by the Maltese Tertiary Education Scholarship Scheme (TESS), however it did not have any role in the conduct of the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ardern CL, Bizzini M, Bahr R. 2016. It is time for consensus on return to play after injury: five key questions. Br J Sports Med. 50(9):506–508. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095475.

- Bahr R, Clarsen B, Wayne D, et al. 2020. International Olympic Committee consensus statement: methods for recording and reporting of epidemiological data on injury and illness in sport 2020 (including STROBE extension for sport injury and illness surveillance (STROBE- SIIS)). Br J Sports Med. 54(7):372–389. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2019-101969

- Barboza, S. D., Bolling, C. S., Nauta, J., Mechelen, W. Van, & Verhagen, E. 2017. Acceptability and perceptions of end-users towards an online sports-health surveillance system. British Med J Open Sport & Exercise Med. 3:e000275. doi:10.1136/bmjsem-2017-000275

- Bekker, S., Bolling, C., H Ahmed, O., Badenhorst, M., Carmichael, J., Fagher, K., Hägglund, M., Jacobsson, J., John, J. M., Litzy, K., H Mann, R., D McKay, C., Mumford, S., Tabben, M., Thiel, A., Timpka, T., Thurston, J., Truong, L. K., Spörri, J., … Verhagen, E. A. 2020. Athlete health protection: why qualitative research matters. J Sci Med Sport. 23(10):898–901. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2020.06.020

- Bolling, C., Delfino Barboza, S., van Mechelen, W., & Pasman, H. R. 2020. Letting the cat out of the bag: athletes, coaches and physiotherapists share their perspectives on injury prevention in elite sports. Br J Sports Med. 54(14):871–877. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2019-100773

- Bolling, C., Delfino, S., Willem, B., & Roeline, H. 2018. How elite athletes, coaches, and physiotherapists perceive a sports injury. Translational Sports Medicine. 1:17–73. doi:10.1002/tsm2.53

- Braun V, Clarke V. 2020. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol. 1–25. doi:10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Braun V, Clarke V, Weate P. 2017. Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In: Smith B, Sparkes AC, editors. Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise. (pp. 213–227). Routledge

- Bromley, S., Drew, M., Talpey, S., McIntosh, A., & Finch, C. 2018. Collecting health and exposure data in Australian Olympic combat sports: feasibility study utilizing an electronic system. J Med Internet Res. 20(10):1–12. doi:10.2196/humanfactors.9541

- Burns L, Weissensteiner JR, Cohen M. 2019. Supportive interpersonal relationships: a key component to high-performance sport. Br J Sports Med. 53(22):1386–1389. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-100312.

- Clarsen B, Bahr R. 2014. Matching the choice of injury/illness definition to study setting, purpose and design: one size does not fit all! Br J Sports Med. 48(7):510–512. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-093297.

- Clarsen, B., Bahr, R., Myklebust, G., Andersson, S. H., Docking, S. I., Drew, M., Finch, C. F., Fortington, L. V., Harøy, J., Khan, K. M., Moreau, B., Moore, I. S., Møller, M., & Nabhan, D. 2020. Improved reporting of overuse injuries and health problems in sport: an update of the Oslo Sport Trauma Research Center questionnaires. Br J Sports Med. 54(7):390–396. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2019-101337

- Corman, S. R., Adame, B. J., Tsai, J. Y., Ruston, S. W., Beaumont, J. S., Kamrath, J. K., Liu, Y., Posteher, K. A., Tremblay, R., & van Raalte, L. J. 2019. Socio-ecological influences on concussion reporting by NCAA Division 1 athletes in high-risk sports. PLoS One. 14(5):1–23. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2019-101539

- Drew MK, Raysmith BP, Charlton PC. 2017. Injuries impair the chance of successful performance by sportspeople: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 51(16):1209–1214. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096731.

- Eirale, C., Tol, J. L., Farooq, A., Smiley, F., & Chalabi, H 2013. Low injury rate strongly correlates with team success in Qatari professional football. Br J Sports Med. 47(12):807–808. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2012-091040

- Ekegren CL, Donaldson A, Gabbe B, Finch C F. 2014. Implementing injury surveillance systems alongside injury prevention programs: evaluation of an online surveillance system in a community setting. Injury Epidemiology. 1(1):1–15. doi:10.1186/s40621-014-0019-y

- Ekegren CL, Gabbe BJ, Finch CF. 2016. Sports injury surveillance systems: a review of methods and data quality. Sports Medicine. 46(1):49–65. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0410-z.

- Ekstrand, J., Krutsch, W., Spreco, A., Van Zoest, W., Roberts, C., Meyer, T., & Bengtsson, H. 2019a. Time before return to play for the most common injuries in professional football: a 16-year follow-up of the UEFA Elite Club Injury Study. Br J Sports Med. 1–6. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2019-100666

- Ekstrand, J., Lundqvist, D., Davison, M., D’Hooghe, M., & Pensgaard, A. M. 2019b. Communication quality between the medical team and the head coach/manager is associated with injury burden and player availability in elite football clubs. Br J Sports Med. 53(5):304–308. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-099411

- Esteve, E., Clausen, M. B., Rathleff, M. S., Vicens-Bordas, J., Casals, M., Palahí-Alcàcer, A., Hölmich, P., & Thorborg, K. 2020. Prevalence and severity of groin problems in Spanish football: a prospective study beyond the time-loss approach. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 30(5):914–921. doi:10.1111/sms.13615

- Fuller, C. W., Ekstrand, J., Junge, A., Andersen, T. E., Bahr, R., Dvorak, J., Hägglund, M., McCrory, P., & Meeuwisse, W. H. 2006. Consensus statement on injury definitions and data collection procedures in studies of football (soccer) injuries. Br J Sports Med. 40(3):193–201. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2005.025270

- Fuller, C. W., Molloy, M. G., Bagate, C., Bahr, R., Brooks, J. H. M., Donson, H., Kemp, S. P. T., Mccrory, P., Mcintosh, A. S., Meeuwisse, W. H., Quarrie, K. L., & Wiley, P. 2007. Consensus statement on injury definitions and data collection procedures for studies of injuries in rugby union. Br J Sports Med. 41(5):328–331. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2006.033282

- Hägglund, M., Waldén, M., Bahr, R., & Ekstrand, J. 2005. Methods for epidemiological study of injuries to professional football players: developing the UEFA model. Br J Sports Med. 39(6):340–346. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2005.018267

- Hägglund M, Waldén M, Ekstrand J. 2009. UEFA injury study—an injury audit of European Championships 2006 to 2008. Br J Sports Med. 43(7):483–489. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2008.056937.

- Hägglund, M., Walden, M., Magnusson, H., Kristenson, K., Bengtsson, H., & Ekstrand, J. 2013. Injuries affect team performance negatively in professional football: an 11-year follow-up of the UEFA champions league injury study. Br J Sports Med. 47(12):738–742. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-092215

- Hammond, L. E., Lilley, J. M., Pope, G. D., & Ribbans, W. J. 2014. ‘We’ve just learnt to put up with it’: an exploration of attitudes and decision-making surrounding playing with injury in English professional football. Qualitative Res Sport, Exercise Health. 6(2):161–181. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2013.796488

- Hammond, L. E., Lilley, J. M., Pope, G. D., Ribbans, W. J., & Walker, N. C. 2011. Considerations for the interpretation of epidemiological studies of injuries in team sports: illustrative examples. Clinical J Sport Med. 21(2):77–79. doi:10.1097/JSM.0b013e318201a7ab

- Ivarsson, A., Johnson, U., Karlsson, J., Börjesson, M., Hägglund, M., Andersen, M. B., & Waldén, M. 2019. Elite female footballers’ stories of sociocultural factors, emotions, and behaviours prior to anterior cruciate ligament injury. Int J Sport Exercise Psychol. 17(6):630–646. doi:10.1080/1612197X.2018.1462227

- Junge A, Derman W, Schwellnus M. 2011. Injuries and illnesses of football players during the 2010 FIFA World Cup. Br J Sports Med. 45:8. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2010.079905

- Junge A, Dvorak J. 2007. Injuries in female football players in top-level international tournaments. Br J Sports Med. 41(SupplI):i3–i7. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2007.036020.

- Junge A, Dvorak J. 2015. Football injuries during the 2014 FIFA World Cup. Br J Sports Med. 49(9):599–602. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-094469.

- Junge, A., Dvorak, J., Graf-Baumann, T., & Peterson, L. 2004. Football injuries during FIFA tournaments and the Olympic games, 1998–2001: development and implementation of an injury- reporting system. Am J Sports Med. 32(1Suppl):80S–9. doi:10.1177/0363546503261245

- Klein, C., Luig, P., Henke, T., & Platen, P. 2019. Injury burden differs considerably between single teams from German professional male football (soccer): surveillance of three consecutive seasons. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 28(5):1656–1664. doi:10.1007/s00167-019-05623-y

- Malmqvist, J., Hellberg, K., Möllås, G., Rose, R., & Shevlin, M. 2019. Conducting the pilot study: a neglected part of the research process? Methodological findings supporting the importance of piloting in qualitative research studies. Int J Qualitative Methods. 18:1–11. doi:10.1177/1609406919878341

- McCall A, Dupont G, Ekstrand J. 2016. Injury prevention strategies, coach compliance and player adherence of 33 of the UEFA Elite Club injury study teams: a survey of teams’ head medical officers. Br J Sports Med. 50(12):725–730. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095259.

- Morgan DL. 2014. Pragmatism as a paradigm for social research. Qualitative Inquiry. 20(8):1045–1053. doi:10.1177/1077800413513733.

- Mountjoy, M., Junge, A., Alonso, J. M., Clarsen, B., Pluim, B. M., Shrier, I., van den Hoogenband, C., Marks, S., Gerrard, D., Heyns, P., Kaneoka, K., Dijkstra, H. P., & Khan, K. M. 2016. Consensus statement on the methodology of injury and illness surveillance in FINA (aquatic sports). Br J Sports Med. 50(10):590–596. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095686

- Nilstad A, Bahr R, Andersen T. 2014. Text messaging as a new method for injury registration in sports: a methodological study in elite female football. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 24(1):243–249. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2012.01471.x.

- Orchard, J. W., Ranson, C., Olivier, B., Dhillon, M., Gray, J., Langley, B., Mansingh, A., Moore, I. S., Murphy, I., Patricios, J., Alwar, T., Clark, C. J., Harrop, B., Khan, H. I., Kountouris, A., Macphail, M., Mount, S., Mupotaringa, A., Newman, D., … Finch, C. F. 2016. International consensus statement on injury surveillance in cricket: a 2016 update. Br J Sports Med. 50(20):1245–1251. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096125

- Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. 2015. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration Policy Mental Health Mental Health Ser Res. 42(5):533–544. doi:10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

- Pluim, B. M., Fuller, C. W., Batt, M. E., Chase, L., Hainline, B., Miller, S., Montalvan, B., Stroia, K. A., Weber, K., & Wood, T. O. 2009. Consensus statement on epidemiological studies of medical conditions in tennis. Br J Sports Med. 43(12):893–897. doi:10.1097/JSM.0b013e3181be35e5

- Raysmith BP, Drew MK. 2016. Performance success or failure is influenced by weeks lost to injury and illness in elite Australian track and field athletes: a 5-year prospective study. J Sci Med Sport. 19(10):778–783. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2015.12.515.

- Roderick M, Waddington I, Parker G. 2000. Playing hurt: managing injuries in English professional football. Int Rev Sociol Sport. 35(2):165–180. doi:10.1177/101269000035002003.

- Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. 2018. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 52(4):1893–1907. doi:10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

- Shrier I. Consensus statements that fail to recognise dissent are flawed by design: a narrative review with 10 suggested improvements. 2020. Br J Sports Med. Published Online First 30 September. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2020-102545.

- Smith B, McGannon K. 2017. Developing rigor in qualitative research: problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. 11(1):101–121. doi:10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357.

- Sparkes AC, Smith B. 2014. Qualitative research methods in sport, exercise and health: from process to product. (pp. 83–114). Routledge

- Stubbe, J. H., Van Beijsterveldt, A. M. M. C., Van Der Knaap, S., Stege, J., Verhagen, E. A., Van Mechelen, W., & Backx, F. J. G. 2015. Injuries in professional male soccer players in the Netherlands: a prospective cohort study. J Athl Train. 50(2):211–216. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.64

- Tayne S, Hutchinson MR, O’Connor FG, et al. 2020. Leadership for the Team Physician. Curr Sports Med Rep. 19(3):119–123. doi:10.1249/JSR.0000000000000696.

- Thornton JS. 2020. Athlete autonomy, supportive interpersonal environments and clinicians’ duty of care; as leaders in sport and sports medicine, the onus is on us: the clinicians. Br J Sports Med. 54(2):71–72. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2019-100783.

- Timpka, T., Alonso, J., Jacobsson, J., Junge, A., Branco, P., Clarsen, B., Kowalski, J., Mountjoy, M., Nilsson, S., Pluim, B., Renström, P., & Rønsen, O. 2014a. Injury and illness definitions and data collection procedures for use in epidemiological studies in athletics (track and field): consensus statement. Br J Sports Med. 48(7):483–490. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-093241

- Timpka, T., Jacobsson, J., Bickenbach, J., Finch, C. F., Ekberg, J., & Nordenfelt, L. 2014b. What is a sports injury? Sports Medicine. 44(4):423–428. doi:10.1007/s40279-014-0143-4

- Truong B, Whittaker. 2020. Removing the training wheels: embracing the social, contextual and psychological in sports medicine. Br J Sports Med. 12. Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102679.

- Truong, L. K., Mosewich, A. D., Holt, C. J., Le, C. Y., Miciak, M., & Whittaker, J. L. 2020. Psychological, social and contextual factors across recovery stages following a sport-related knee injury: a scoping review. Br J Sports Med. 1–11. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2019-101206

- Van Mechelen W, Hlobil H, Kemper HC. 1992. Incidence, Severity, Aetiology and Prevention of Sports Injuries. Sports Medicine. 14(2):82–99. doi:10.2165/00007256-199214020-00002.

- Verhagen E, Bolling C. 2015. Protecting the health of the @hlete: how online technology may aid our common goal to prevent injury and illness in sport. Br J Sports Med. 49(18):1174–1178. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-094322.

- Verhagen, E., Mellette, J., Konin, J., Scott, R., Brito, J., & McCall, A. 2020. Taking the lead towards healthy performance: the requirement of leadership to elevate the health and performance teams in elite sports. British Med J Open Sport & Exercise Med. e000834. doi:10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000834

- Walden M, Hägglund M, Ekstrand J. 2007. Football injuries during European Championships 2004–2005. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 15(9):1155–1162. doi:10.1007/s00167-007-0290-3.

- Werner, J., Hägglund, M., Ekstrand, J., & Waldén, M. 2019. Hip and groin time-loss injuries decreased slightly but injury burden remained constant in men’s professional football: the 15-year prospective UEFA Elite club injury study. Br J Sports Med. 53(9):539–546. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2017-097796

- West SW, Clubb J, Torres-Ronda L, et al. 2020. More than a metric: how training load is used in elite sport for athlete management. Int J Sports Med. Oct 19. doi:10.1055/a-1268-8791.

- Wierike, S. C. M., Sluis, A. Van Der, & Visscher, C. 2013. Psychosocial factors influencing the recovery of athletes with anterior cruciate ligament injury: a systematic review. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 23(5):527–540. doi:10.1111/sms.12010

- Wiese-Bjornstal D. 2010. Psychology and socioculture affect injury risk, response, and recovery in high-intensity athletes: a consensus statement. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 20(Supp2):103–111. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01195.x.

- World Health Organisation. 2001. The international classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva: WHO. 18:237. doi:10.1097/01.pep.0000245823.21888.7

- Yoon YS, Chai M, Shin DW. 2004. Football injuries at Asian tournaments. Am J Sports Med. 32(1_suppl):36S–42S. doi:10.1177/0095399703258781.