ABSTRACT

Black henbane (Hyoscyamus niger) is a member of the nightshade family and an invasive species that grows world-wide, including in Canada. Black henbane is toxic due to its tropane alkaloid contents: hyoscyamine, scopolamine (hyoscine), and atropine. We present two cases of unintentional, acute henbane poisoning. A 65-year-old woman and her 71-year-old husband presented to the emergency department with tachycardia, confusion, hallucinations, and urinary retention after eating a plant thought to be a parsnip from their garden, later identified by family as black henbane. During admission, the woman developed an asymptomatic new left bundle branch block with no other signs of ischemia. Both patients were managed supportively; their toxidromes resolved within 36-48 hours. These cases illustrate the rapid antimuscarinic effects associated with black henbane poisoning. This is the first report describing a new left bundle branch block in the context of black henbane poisoning. However, no published reports of sodium channel activity with any of the constituents was found. Increased public information is needed to educate individuals on the recognition of these mimic plants, as well as the dangers of ingestion, given their ubiquity in private gardens.

Introduction

Black henbane (Hyoscyamus niger), a worldwide invasive nightshade, contains hyoscyamine, scopolamine (hyoscine), and atropine throughout [Citation1]. These competitive central and peripheral receptor antagonists have profound antimuscarinic effects [Citation2]. Peripheral signs occur first, followed by central nervous system (CNS) effects with large ingestions [Citation2]. We present two cases of acute, unintentional poisoning.

Case report 1

Pre-hospital events

A 65-year-old woman ingested the cooked root of an “odd parsnip” from her garden. The plant was immature and flowerless. She vomited within 10 min of ingestion. A friend brought her to the hospital along with a sample leaf of the presumed parsnip.

Course in hospital

She arrived to the emergency department (ED) 1 h post-ingestion. She initially had a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 15 and vital signs as follows: temperature (T) 36.9 degrees C, heart rate (HR) 104 beats/min, blood pressure (BP) 125/79 mmHg, respiratory rate (RR) 20 breaths/min, and oxygen saturation (O2 Sat) of 100%. She was initially alert and oriented to person, place, and time, but subsequently, she became forgetful and agitated (climbing out of bed and pulling at intravenous) with scattered thoughts, had visual hallucinations of animals, mydriasis (6 mm bilaterally and sluggishly reactive), dry mucous membranes, warm and dry skin, and urinary retention (bladder volume of more than 940 mL via bladder scan). Her GCS was not calculated at that time.

Her initial electrocardiogram (ECG) showed tachycardia, bigeminy, and non-specific ST-T changes. All other investigations (complete blood count; electrolyte panel; venous blood gas; liver function tests; troponin concentrations; serum ethanol, acetaminophen, and salicylates) were normal. She was treated with intravenous fluids (initially 125 mL/h of 0.9% normal saline for 18 h then maintenance fluids 75 mL/h for 17 h) and lorazepam (1 mg sublingually) due to multiple attempts to pull out her intravenous.

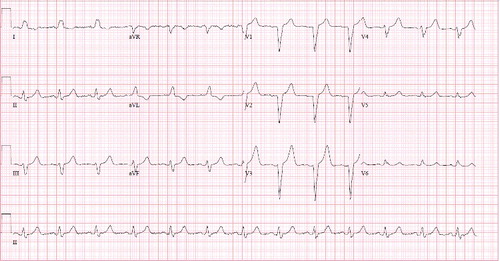

Her memory difficulty and hallucinations fluctuated throughout the admission until these subsided at 27 h. Shortly thereafter (28.5 h), her rhythm changed on telemetry, which prompted a repeat ECG that showed a widened QRS complex (123–132 ms) and a new left bundle branch block (LBBB) (See for this ECG). Her last normal sinus rhythm ECG was at 25 h; the initial ECG was at 1 h with a total of four normal sinus rhythm ECG's prior to her LBBB. She was given repeated doses of 1 L of D5W and 150 mmol of sodium bicarbonate intravenously at 100 mL/h with potassium chloride coverage for a total of 24 h after she developed the LBBB (and after the discontinuation of maintenance fluids as above). This narrowed the QRS slightly (120–130 ms). The rest of her symptoms resolved at 45 h.

Cardiology was consulted and found no signs of ischemia or infarct. She was discharged on day 3.

Post-hospital events

She described fatigue and “fuzziness” for three weeks post-ingestion. At the outpatient cardiology follow up, she still had an asymptomatic LBBB on her ECG but, normal further cardiac investigations (normal echocardiogram and myocardial perfusion imaging with no signs of ischemia or reduced ejection fraction).

Case report 2

Pre-hospital events

The 71-year-old previously healthy husband of the female patient ingested the same plant.

Course in hospital

He arrived to the ED 4 h post-ingestion. He had a GCS of 13 (E4 M6 V3) initially, though he rapidly declined over 2 h to a GCS of 9 (E2 M5 V2), and vital signs as follows: T 37.4 degrees C, HR 131 beats/min, BP 157/80 mmHg, RR 24 breaths/min, and O2 Sat of 95%. He also had disorientation, profound agitation (reacting to external stimuli, restless, thrashing, combative), visual hallucinations of animals, mydriasis (5 mm bilaterally), dry mucous membranes, warm and dry skin, mild urinary retention (bladder volume of more than 200 mL via bladder scan), tremulousness, and unsteady gait; he fell several times prior to arrival. His trauma exam revealed a small, 1 cm laceration to the head.

His initial ECG showed sinus tachycardia. All investigations (complete blood count; electrolyte panel; liver function tests; serum ethanol, acetaminophen, and salicylates; CT head) were normal, apart from a transient metabolic alkalosis on venous blood gas. He did not experience any dysrhythmias.

He experienced hallucinations for 17 h. He was treated with IV fluids (2.5 L bolus of 0.9% normal saline followed by 125 mL/h for a total of 29 h) and nine doses of intravenous lorazepam (total of 10 mg). He was physically restrained for 16 h due to agitation. While physostigmine was considered given this patient's profound agitation and physical/chemical restraint requirement, it is a special access medication with Health Canada and not readily available in our province. His toxidrome eventually resolved and he was therefore discharged on day 2.

Post-hospital events

He remained amnestic to these events months later and felt fatigued for three weeks afterwards.

Discussion

Black henbane has large, foul-smelling leaves – reportedly a “sickly, fishy smell”; a thick, fleshy taproot; and yellow flowers with purple veins [Citation3,Citation4] ( and depict black henbane plants, however they are not of the actual plant that was ingested).

Figure 2. Black henbane flowers courtesy of Nicole Kimmel – Weed Specialist, Alberta Agriculture and Forestry.

Figure 3. Several black henbane plants courtesy of Nicole Kimmel – Weed Specialist, Alberta Agriculture and Forestry.

Similar unintentional ingestions (mistaken for a parsnip) have been reported in other case reports [Citation5–7]. One case had black henbane seeds mixed with poppy seeds at a bakery causing unintentional ingestions [Citation8]. Other cases mentioned intentional ingestions for euphoric effects or as an Ayurvedic drug [Citation9–11].

Treatment varies widely. Anecdotal use of gastric lavage [Citation12] and/or physostigmine [Citation13] was reported with various degree of success. Moreover, children with antimuscarinic symptoms after black henbane ingestion tend to leave hospital within 48 h with supportive care alone [Citation5].

There is a paucity of recent case reports of black henbane ingestion, with the last published in 2007. Hallucinations are common amongst reports [Citation5]. Cardiac effects appear rare, with only one article mentioning dysrhythmias without describing them in more detail [Citation14].

The lack of confirmatory testing is a limitation of this report. However, the patients’ daughter easily identified the leaf as black henbane using her occupational knowledge. Both patients had similar courses exhibiting the antimuscarinic toxidrome consistent with other black henbane exposures.

These cases illustrate the rapid antimuscarinic effects of black henbane poisoning consistent with the previous literature. This is the first report describing a new LBBB in black henbane poisoning; though, we have been unable to find reported sodium channel activity of any constituents of black henbane. Therefore, the connection, if any, is unclear. Supply–demand mismatch is another possible reason for this patient's LBBB. Increased public information regarding recognition of these toxic mimic plants is necessary given their ubiquity, even in private gardens.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Nicole Kimmel for the black henbane images as well as Mark Yarema and Nora MacLeod-Glover for their review and guidance. Furthermore, we would like to thank these two patients for graciously allowing us to write this report.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Canadian Biodiversity Information Facility. Black henbane (common name) [Internet]. Can Poisonous Plants Inf Syst. 2013 [ cited 2016 Dec 18]. Available from: http://www.cbif.gc.ca/eng/species-bank/canadian-poisonous-plants-information-system/all-plants-common-name/black-henbane/?id=1370403267061.

- Barceloux DG. Medical toxicology of natural substances: foods, fungi, medicinal herbs, plants, and venomous animals. Hoboken (NJ): Wiley; 2008.

- Genders R. Scented flora of the world. London (UK): Robert Hale Ltd; 1977. Available from: https://books.google.ca/books?id=kkUNAQAAMAAJ.

- Alberta Invasive Species Council. Fact sheet – Black Henbane [Internet]. Alberta Invasive Species Council. 2014. Available from: https://www.abinvasives.ca/fact-sheets.

- Alizadeh A, Moshiri M, Alizadeh J, et al. Black henbane and its toxicity – a descriptive review. Avicenna J Phytomedicine. 2014;4:297–311.

- Grieve M. Henbane. In: Leyel, CF, editor. A Modern Herbal: Volume 1. New York (NY): Dover Publications, Inc; 1971. p. 406.

- Spoerke DG, Hall AH, Dodson CD, et al. Mystery root ingestion. J Emerg Med. 1987;5:385–388.

- Stefánek J, Dufincová J, Vychytil P, et al. Mystery of mydriatic pupils. Vnitr Lek. 2000;46:808–810. Czech.

- Tugrul L. Abuse of henbane by children in Turkey. Bull Narc. 1985;37:75–78.

- Sands JM, Sands R. Henbane chewing. Med J Aust. 1976;2:55, 58.

- Aparna K, Joshi AJ, Vyas M. Adverse reaction of Parasika Yavani (Hyoscyamus niger Linn): two case study reports. Ayu. 2015;36:174–176.

- Doneray H, Orbak Z, Karakelleoglu C. Clinical outcomes in children with hyoscyamus niger intoxication not receiving physostigmine therapy. Eur J Emerg Med. 2007;14:348–350.

- Urkin J, Shalev H, Sofer S, et al. Henbane (Hyoscyamus reticulatus) poisoning in children in the Negev. Harefuah. 1991;120:714–716. Hebrew.

- Vidović D, Brecić P, Haid A, et al. Intoxication with henbane. Lijec Vjesn. 2005;127:22–23. Croatian.