Abstract

Apraclonidine, a weak alpha-1-agonist and strong alpha-2-agonist, is commonly used in the evaluation of anisocoria related to Horner’s Syndrome (HS) in the form of an ophthalmic solution. Apraclonidine is a polar derivative of clonidine favored in the management of ocular hypertension given its comparative efficacy yet decreased incidence of systemic side effects, postulated to be secondary to the decreased permeability of apraclonidine across the mature blood-brain barrier. Despite the favorable adverse effect profile in adults, our case report illustrates that apraclonidine may lead to systemic side effects in infants, especially those less than 6 months of age. Adverse symptoms reported include lethargy, transient hypertension, bradycardia, bradypnea and hypoxia. Parents of infants treated with apraclonidine should receive warning of these potential adverse effects. Outcomes are generally benign. Pediatric and emergency providers should be aware of the potential for apraclonidine to cause an otherwise alarming presentation of a lethargic infant.

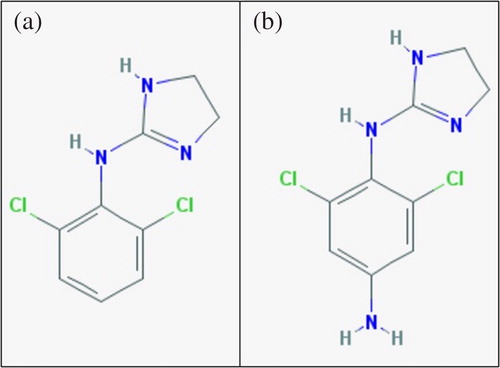

Apraclonidine, a weak alpha-1-agonist and strong alpha-2-agonist chemically similar to clonidine (), is used to evaluate anisocoria related to Horner’s syndrome (HS) [Citation1]. Pediatric HS is most commonly idiopathic or postsurgical, but may indicate neuroblastoma or other brainstem processes warranting evaluation [Citation2]. The anisocoria of HS occurs from interruption of the ipsilateral sympathetic innervation to the pupillary dilators, leading to unopposed parasympathetic-mediated miosis. This sympathetic denervation then results in upregulation of alpha-1 receptors on the iris dilator muscle. Bilateral administration of topical apraclonidine may reverse HS anisocoria by binding these hypersensitive alpha-1 receptors compared to physiologic anisocoria in which the alpha-2 activity produces no change or even mild pupillary constriction [Citation1]. Apraclonidine has replaced topical cocaine as the standard agent to evaluate for pediatric HS due to its ease of availability and the generalized hesitancy of parents in using a controlled substance as a diagnostic tool [Citation2].

Figure 1. Two-dimensional chemical structures of clonidine (a) and apraclonidine (b), both alpha-2 agonists. National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Database; CID = 2216, https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/2216 (accessed 2018 Oct 10).

A 4-month-old female infant was referred to ophthalmology for evaluation of anisocoria first noted at 2 months age. She was otherwise asymptomatic prior to her appointment. She received one drop to each eye of 1.0% (0.5 mg/drop) apraclonidine ophthalmic solution and was diagnosed with physiologic anisocoria. After the appointment, she appeared excessively sleepy at home and was unable to maintain alertness to complete breastfeeding sessions.

She came to the pediatric emergency department 10 hours after apraclonidine administration for evaluation of lethargy. On arrival, she was hypertensive to 114/49 with a heart rate of 120 beats per minute, temperature 36 °C, respiratory rate of 32 and had 100% peripheral oxygen saturation on room air. She appeared somnolent but was arousable to physical stimuli, awakening only while being examined and quickly falling back asleep. Her physical exam was otherwise non-focal. Family remained for 4 hours of observation. Prior to discharge her hypertension resolved, and she nursed successfully, though she remained sleepier than usual. She appeared neurologically normal on follow up with her pediatrician the next day.

On review of the current literature, we found only one case series detailing adverse effects of topical apraclonidine when used in the diagnosis of HS in infants [Citation3]. Watts et al. described a 5-month-old who presented similarly with lethargy, hypertension, bradycardia, shallow respirations and hypoxemia that resolved completely after 8 hours. The authors learned of seven additional cases of apraclonidine use in infants by pediatric ophthalmologists. Three cases had no recognized side effects, three cases had drowsiness of undefined length and one 10-week-old had lethargy lasting 10 hours. In addition to HS, the use of 0.5% (0.25 mg/drop) topical apraclonidine has been reported in the evaluation of children with glaucoma. One retrospective review reported lethargy associated with use in 3 of 75 studied patients; all three children were less than or equal to 4 months of age [Citation4].

In 2009, Becker et al. reported on 200 children under age 5 years with somnolence or lethargy after ophthalmic brimonidine exposure [Citation5]. Most had observation in the ED or at home with telephonic follow up with the poison center. Only 28 were hospitalized, and 11 received naloxone. The authors opined that role of naloxone in treating alpha-2 agonist drug toxicity was unclear [Citation5].

Apraclonidine may have a more favorable adverse effect profile in adults compared to its parent drug clonidine due to lower permeability of apraclonidine across the blood-brain barrier [Citation6]. Central alpha-2 effects predominate in pediatric overdose of clonidine and other topical imidazoline-derivatives with toxidromes characterized by central nervous system depression, respiratory depression and cardiovascular instability [Citation5,Citation7,Citation8]. In contrast, systemic effects are absent with peripherally-acting apraclonidine use in adult safety studies [Citation6]. However, our report adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting apraclonidine may lead to central side effects in infants, especially in those less than 6 months of age. This case is the second describing lethargy, hypertension and bradypnea in infants in association with topical apraclonidine use and the first reporting symptoms lasting >14 hours. These reports align with new molecular evidence that suggests developing cerebral vessels appear to be fragile, rendering young brains more vulnerable to drugs that are solely peripheral actors in adults [Citation9].

No approved antidote is currently available for use in alpha-2 agonist toxicity. Poison centers may often recommend naloxone with varying results. In 2018, Seger and Loden reported that high dose naloxone better reverses somnolence and avoids morbidity associated with intubation for symptomatic clonidine toxicity [Citation10].

Medical providers using apraclonidine should be aware of the potential for producing somnolence and lethargy in infants. Parents of infants exposed to apraclonidine should receive warning of the adverse effects and should receive ample anticipatory guidance regarding when to present for evaluation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Morales J, Brown SM, Abdul-Rahim AS, et al. Ocular effects of apraclonidine in Horner syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:951–954.

- Bacal D, Levy S. The use of apraclonidine in the diagnosis of Horner syndrome in pediatric patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:276–279.

- Watts P, Satterfield D, Lim MK. Adverse effects of apraclonidine used in the diagnosis of Horner syndrome in infants. J Aapos. 2007;11:282–283.

- Wright T, Freedman S. Exposure to topical apraclonidine in children with glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2009;18:395–398.

- Becker ML, Huntington N, Woolf AD. Brimonidine tartrate poisoning in children: frequency, trends, and use of naloxone as an antidote. Pediatrics 2009;123:e305–ee31.

- Yuksel N, Güler C, Çaglar Y, et al. Apraclonidine and clonidine: a comparison of efficacy and side effects in normal and ocular hypertensive volunteers. Int Ophthalmol 1992;16:337–342.

- Eddy O, Howell J. Are one or two dangerous? Clonidine and topical imidazolines exposure in toddlers. J Emerg Med. 2003;25:297–302.

- van Velzen AG, van Riel AJHP, Hunault C, et al. A case series of xylometazoline overdose in children. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2007;45:290–294.

- Saunders NR, Liddelow SA, Dziegielewska KM. Barrier mechanisms in the developing brain. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:46.

- Seger DL, Loden JK. Naloxone reversal of clonidine toxicity: dose, dose, dose. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2018;56:873–879.