Abstract

A 30-year-old male had an occupational exposure while measuring selenomethionine. He left work due to onset of nausea, weakness and vomiting. He showered and changed clothes at home. Due to continued worsening of symptoms, four hours post-exposure he was brought to an urgent care center (UCC), where he was immediately transported via ambulance to an emergency department (ED). He was noted by UCC and ED staff to have a strong noxious chemical odor. The patient deteriorated rapidly requiring intubation, and PEEP with 100% O2. Naloxone, dextrose, bicarbonate, fluid resuscitation and dopamine infusion were administered. Twenty minutes after arrival, the patient experienced asystole. Resuscitation was not successful. Postmortem blood selenium concentration was 11,000 µg/L. A multi-agency hazmat investigation occurred. The UCC and the patient’s home were locked down. Twenty-four personnel were quarantined on-site for 7 h. Eight employees of the UCC underwent decontamination and transport to an ED for evaluation. Family members and immediate responding officers were quarantined on-site. Volatile methylated forms of selenium excreted in breath and sweat and not residual selenomethionine powder likely caused the chemical odor reported by the ED staff. Secondary contamination of ED personnel is a risk from self-presentation by symptomatic patients after a chemical exposure. Secondary contamination of ED personnel is unlikely from a powdered substance after presentation of a patient who has showered and changed clothes but given the unknown nature at the time, Hazmat Incident Commanders may decide to exercise an abundance of precaution.

Introduction

Occupational injuries involving chemical exposures are common [Citation1]. However, occupational chemical incidents that contaminate emergency personnel and emergency departments are infrequent [Citation2, Citation3]. Larson et al. describe four events over a 6-year period in which medical facilities were either shut down or evacuated due to secondary contamination [Citation2]. Despite guidelines and preparation, such incidents continue to occur.

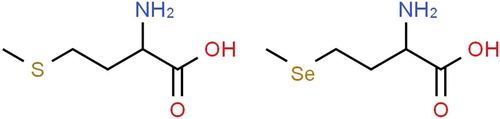

We report a case of a rapidly fatal occupational exposure to the amino acid L-selenomethionine () resulting in a multi-agency hazardous materials (hazmat) response and subsequent closure of an urgent care clinic [Citation4, Citation5]. There have been no previous reported human fatalities from selenomethionine. The case report is exempt from review or consent in accord with our IRB.

Case report

A 30-year-old male arrived at work at a vitamin and supplement factory. During his shift, he was asked to measure out 10.5 g of L-selenomethionine (CAS 3211-76-5) while wearing gloves and safety goggles. Upon opening the sealed bag-container, the white L-selenomethionine powder blew back onto him contaminating his clothes and skin and leading to inhalation of the powder. No decontamination occurred at the plant, and he soon began to complain of nausea and light-headedness. He asked to leave work, and within 30-45 min post exposure his wife brought him home in a private vehicle. At home he removed his clothes and reportedly showered. His symptoms worsened with vomiting, increased shortness of breath, and weakness. Approximately 4 h post exposure with his condition continuing to worsen his wife brought him to an urgent care center (UCC), which immediately transported him via ambulance to a nearby hospital. Upon arrival at the hospital emergency department (ED), the initial exam showed an obtunded patient who could verbalize his name. His wife provided a material safety data sheet (MSDS) on selenomethioine that the patient had brought from the workplace. Initial vital signs were heart rate 80–120 BPM, BP 100/50 mmHg, and oxygen saturation 75% with rapid (30-40/minute) shallow respirations. There was a strong noxious “chemical” odor noted by UCC, transport and ED staff. He received naloxone without effect. His oxygen saturation remained below 93% despite endotracheal intubation and ventilation with 100% oxygen. An EKG showed atrial fibrillation. Abnormal chemistries included venous pH 7.01, glucose 17 mg/dL (0.94 mmol/L), bicarbonate 12 mEq/L, BUN 14 mg/dL, and creatinine 1.51 mg/dL. Despite resuscitation efforts including IV sodium bicarbonate, IV dextrose, dopamine infusion, and repeated attempts at electrical cardioversion, his blood pressure and heart rate rapidly declined to asystole within 20 min after ED arrival. Further resuscitation efforts were not successful.

Initially the patient reported to the UCC staff that he had been exposed to a chemical at work. UCC staff reported a very strong noxious odor. Given the patient’s smell and rapid decline with transfer to an ED, a multi-agency hazmat investigation began at the UCC and the patient’s home. The UCC was locked down and 24 personnel were quarantined on-site for over 7 h. Eight employees of the UCC with potential direct patient contact underwent decontamination and transport to the nearby emergency department for evaluation and were later released. The patient’s home was also locked down, and family members and immediate responding officers were quarantined on-site for 9 h.

Autopsy revealed pulmonary edema, frothy fluid and blood in pulmonary parenchyma, and sections of the trachea with denuded epithelium. Sections of the esophagus showed focal areas with loss of epithelium and coagulative necrosis. Sections of the stomach showed focal areas of coagulative necrosis and the duodenum showed diffuse coagulative necrosis. Postmortem testing of blood showed selenium 11,000 µg/L (population range < 160 µg/L), methadone 0.18 µg/mL (therapeutic range 0.1-0.4 µg/mL) and trazodone 0.18 µg/mL (therapeutic range < 2.0 µg/mL). Urine selenium concentrations were 25,000 µg/L (reference < 200 µg/L) and 42,000 µg/g creatinine (reference < 25 µg/g creatinine). The decedent had prescriptions for and was taking methadone and trazodone therapeutically.

Discussion

The selenium (Se) concentrations in this patient are consistent with previous selenium fatalities involving different forms of selenium after ingestion and a single occupational inhalation fatality summarized in [Citation6–15]. To our knowledge, this is the first reported fatality due to an organoselenium: selenomethionine. In lambs, after acute oral exposure, selenomethionine produces a higher serum and blood Se concentrations compared with sodium selenite but appears slightly less toxic [Citation6]. However, selenomethionine produces significantly higher myocardium Se levels than selenite [Citation16]. The primary cause of selenium fatalities is a consequence of refractory hypotension and cardiopulmonary collapse [Citation17].

Table 1. Selenium related fatalities.

Secondary contamination of ED personnel and ED facilities is a risk from self-presentation by symptomatic patients after a chemical exposure without prior decontamination. This secondary contamination can lead to staff injuries, and costly evacuations or even closures [Citation2, Citation3]. Staff education and training, regarding proper decontamination techniques including self-protection with appropriate personal protective equipment, should be delivered on a routine basis. In this case, the chemical odor reported by the ED staff was likely caused by volatile methylated forms of selenium excreted in breath and sweat and not residual selenomethionine powder, considering the patient had reportedly showered and changed clothes after leaving work [Citation18, Citation19]. While the methylated selenium moieties are volatile and produce noticeable odor from poisoned patients, the amounts produced by a patient are clinically insignificant and insufficient to produce secondary contamination [Citation18, Citation20]. Without initially knowing the extent of the chemical exposure, the ED closures and decontamination measures taken in this case may be justified [Citation2, Citation3]. However, in hindsight, the ED closure and staff quarantine were likely not necessary, due to the low risk of secondary exposure from off-gassing of methylated selenium metabolites via breath and sweat [Citation18].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Orr MF, Wu J, Sloop SL, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Acute chemical incidents surveillance – Hazardous substances emergency events surveillance, Nine States, 1999-2008. MMWR Suppl. 2015;64(2):1–9.

- Larson TC, Orr MF, Auf der Heide E, et al. Threat of chemical contamination of emergency departments and personnel: an uncommon but recurrent problem. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2016;10(2):199–202.

- Horton DK, Orr M, Tsongas T, et al. Secondary contamination of medical personnel, equipment and facilities resulting from hazardous materials events, 2003-2006. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2008;2(2):104–113.

- Available from: https://www.deseret.com/2010/1/20/20365530/saratoga-springs-man-dies-after-chemicalaccident#women-check-their-phones-during-a-police-quarantine-at-an-intermountain-instacare. [last referenced 2019 Apr 11]

- Available from: https://www.deseret.com/2010/1/21/20365693/questions-surround-death-of-saratoga-springsman-exposed-to-chemical. [last referenced 2019 Apr 11].

- Schellmann B, Raithel HJ, Schaller KH. Acute fatal selenium poisoning. Arch Toxicol. 1986;59(1):61–63.

- Hunsaker DM, Spiller HA, Williams D. Acute selenium poisoning: Suicide by ingestion. J Forensic Sci. 2005;50(4):942–946.

- Quadrani DA, Spiller HA, Steinhorn D. fatal case of gun blue ingestion in a toddler. Vet Human Toxicol. 2000;42(2):96–98.

- Matoba R, Kimura H, Uchima E, et al. An autopsy case of acute selenium (selenious acid) poisoning and selenium levels in human tissues. Forensic Sci Int. 1986;31(2):87–92.

- Pentel P, Fletcher D, Jentzen J. Fatal acute selenium toxicity. J Forensic Sci. 1985;30(2):556–562.

- Lech T. Suicide by tetraoxoselenate (VI) poisoning. Foren Sci Intern. 2002;130(1):44–48.

- Williams R, Ansford A. Acute selenium toxicity: Australia’s second fatality. Pathol. 2007;39(2):289–290.

- See KA, Lavercombe PS, Dillon J, et al. Accidental death from acute selenium poisoning. Med J Austr. 2006;185(7):388–389.

- Spiller HA, Pfiefer E. Two fatal cases of selenium toxicity. Foren Sci Intern. 2007;171(1):67–72.

- Chomchai C, Sirisamut T, Silpasupagornwong U. Pediatric fatality from gun bluing solution: the need for a chemical equivalent of the one-pill-can-kill list. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95(6):821–824.

- Tiwary A, Stegelmeier BL, Panter KE, et al. Comparative toxicosis of sodium selenite and selenomethionine in lambs. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2006;18(1):61–70.

- McAdam PA, Levander OA. Chronic toxicity and retention of dietary selenium fed to rats as D- or L-selenomethionine, selenite or selenate. Nutri Res. 1987;7(6):601–610.

- Wilber CG. Toxicology of selenium. Clin Toxicol. 1980;17(2):171–230.

- Ganther HE. Pathways of selenium metabolism including respiratory excretory products. Inter J Toxicol. 1986;5:1–5.

- Barceloux DG, Barceloux D. Selenium. Clin Toxicol. 1999;37:145–172.