Abstract

The evaluation of a patient after Crotalinae envenomation requires assessment of local and systemic signs and symptoms in conjunction with laboratory data. Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is an emerging modality used to evaluate soft tissue changes associated with snake envenomations around the world. However, more data are needed to characterize sonographic findings of snake envenomation. Our study used POCUS to evaluate the depth of soft tissue injury, involvement of the muscles/tendons, and the proximal edge of envenomation. This was a prospective observational study evaluating the sonographic characteristics of Crotalinae envenomation. The eight patients enrolled in the study included one envenomated by a Western diamondback (Crotalus atrox), and the others were envenomated by copperheads (Agkistrodon contortrix). All the patients demonstrated initial subcutaneous cobblestoning on POCUS at the bite site. All digit envenomations revealed edema in the tendon or tendon sheath. None of these cases required acute surgical intervention. There were no sonographic signs of envenomation found below fascia or muscle. Four of the eight patients had POCUS findings of cobblestoning proximal to the edge of envenomation palpated on the extremity. The clinical significance of this is unknown.

Introduction

Crotalinae snake envenomations frequently present to the hospital during spring, summer, and autumn seasons. Treatment of these envenomations are variable depending on the experience of the clinician and species of the snake [Citation1]. Antivenom therapy is indicated for proximal progression of soft tissue injury or hematologic toxicity [Citation2]. Compartment syndrome is often feared due to overlapping signs and symptoms, but is rarely encountered. This fear occasionally results in surgical consultation despite the lack of evidence for the efficacy of fasciotomy [Citation3].

Non-invasive evaluation of the depth and proximal spread of soft-tissue injury from Crotalinae envenomation with point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) will be helpful to treating clinicians when determining the most appropriate course of treatment. One group described sonographic findings of pit viper envenomation in central California [Citation4]. Their findings included subcutaneous edema, fluid in tendon sheaths, finger pulp disruption, and fasciculations. Although once limited, POCUS is now a ubiquitous resource in emergency departments, allowing for a non-invasive, repeatable diagnostic evaluation.

This investigation aimed to further characterize POCUS findings of predominantly copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix) envenomations in central Virginia. We focused on the depth of soft-tissue injury above or below the fascia or tendon sheath, at the site of envenomation, and at the proximal edge of envenomation of the limb.

Methods

Study design

This was a prospective observational study evaluating the sonographic characteristics of Crotalinae envenomation, approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Setting and population

We conducted our study at Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center, a large urban tertiary trauma center in Richmond, Virginia. The vast majority of Crotalinae envenomations in our region are copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix). However, our study included envenomation from rattlesnakes and cottonmouth snakes. Inclusion criteria consisted of patients greater than six years old presenting with signs and symptoms of Crotalinae envenomation. Signs and symptoms of Crotalinae envenomation include swelling, tenderness, pain at the bite site and hematologic abnormalities such as thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy. Exclusion criteria included patient refusal, dry bites, pregnancy and police custody or incarceration.

Study protocol

We identified patients through calls to the Virginia Poison Center, or direct consultation from the emergency department or in-patient hospital service. We collected a convenience sample of patients based on investigator availability. Board-certified emergency medicine physicians involved in the study performed the ultrasound after informed consent. The ultrasound examination included acquisition of images at the puncture site, contralateral limb at the same location and proximal edge envenomation. The investigator determined the proximal line of envenomation by making a subjective assessment through palpation and delineation of pain. Once identified, investigators used an 8-mHz linear array probe to acquire images in the longitudinal and transverse planes.

Measures

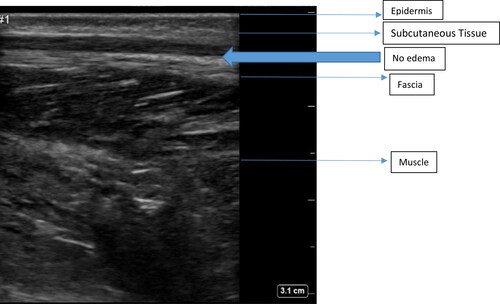

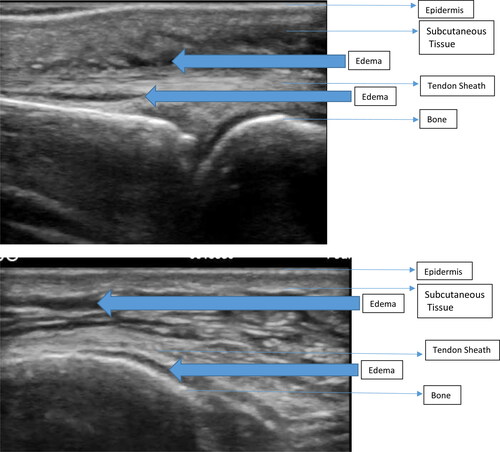

We recorded measurements and clinical data without patient identifiers. Patient data included: time of POCUS evaluation, estimated species of the snake, age, gender, antivenom use and analgesics administered. Laboratory data included: lowest reported hematologic indices including platelet count, fibrinogen and PT/PTT. Sonographic data included: presence of edema in the subcutaneous space, depth of edema, and any signs of edema deeper than the subcutaneous space. We used water bath ultrasound to describe presence of edema in the tendon or tendon sheaths for digit envenomations. We also performed POCUS on the contralateral limb at the same anatomic site for comparison. Additionally, we documented sonographic findings at the proximal line of envenomation. We repeated the same ultrasound study (if feasible) before hospital discharge.

Our primary endpoint was to describe the sonographic signs of Crotalinae envenomation. Our secondary endpoints included the depth of soft-tissue changes seen on ultrasound including signs of injury extending beyond the subcutaneous space into fascia and muscle. Lastly, we aimed to determine whether or not sonographic findings were present proximal to the line of envenomation. We summarized the data using descriptive statistics.

Results

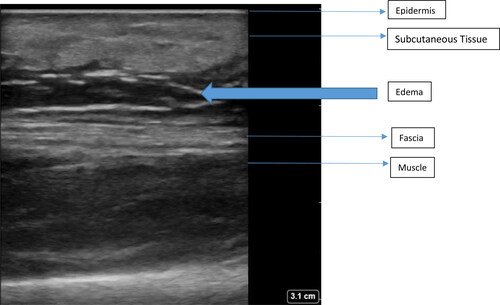

The study enrolled eight patients during a 29 month study period. Of these, 6 were male, and the median age of the participants was 45 years (range: 21–71). All patients received treatment with a median of four vials (4–12) of Crotalidae Polyvalent Immune Fab (CroFab®, BTG International, Conshohocken PA; Fab AV). The decision to treat with Fab AV was made before the ultrasound examination. The snake species included one captive Western diamondback (Crotalus atrox) and the others were copperheads (Agkistrodon contortrix). Five of the bites involved digits. The median time post-envenomation until initial POCUS was 6.5 h (range 3–21) and only three had a documented discharge POCUS. All the patients had subcutaneous cobblestoning at the bite site () compared to the non-envenomated limb (). Physical examination revealed soft tissue swelling with no associated blebs or vesicles. All digit envenomations demonstrated edema in the tendon or tendon sheath ( and 4). Of the non-digit envenomations, there was no edema below the fascia or muscle. Four of the eight patients had POCUS findings of cobblestoning proximal to the edge of envenomation with a median distance of 3 cm (range 0–13). All hematological indices were within normal limits. One patient underwent hand debridement and small tissue flap five weeks post-envenomation for a non-healing wound. There were no patients with concerns for compartment syndrome and compartment pressures were not measured.

Discussion

As expected, all the patients demonstrated subcutaneous edema at the bite site compared to the unaffected side. Crotalinae snake venom contains cytotoxins that create pores in the cell membrane leading to apoptosis. It also contains metalloproteinases that contribute to endothelial damage and inflammatory response [Citation5]. Our predominantly copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix) envenomations had similar sonographic findings of cobblestoning and edema above the fascia as described by Vohra and colleagues from rattlesnake envenomations in central California [Citation4].

A series of envenomations from South Africa also described the sonographic findings of subcutaneous and muscle edema [Citation6]. They used POCUS to evaluate people presumably envenomated by puff adder (Bitis arietans) and Mozambique spitting cobra (Naja mossambica). These snakes are from different families, but their venom contains similar cytotoxic components as the American Crotalinae species. They compared the dimensions of the subcutaneous and muscle tissue with the non-envenomated limb. They expressed this as a coefficient in which a ratio of one indicated no difference in size. They found the subcutaneous coefficient expanded to twice the value of the muscular compartment. Their one patient with an outlying coefficient was bitten by a puff adder (B. arietans), had 60 h of edema, and underwent fasciotomy because of elevated compartment pressures.

Vohra et al. and our study both described digit envenomation with edema of the tendon sheath [Citation6]. Despite edema involving a tendon, our patients did well clinically without acute surgical intervention. However, over a month after envenomation, a patient did have poor wound healing and required a small skin flap. Vohra et al. reported a good outcome in their patient with finger tendon edema as well.

Finally, our series demonstrated that patients frequently had cobblestoning proximal to the edge of the edema palpated on the surface of the skin, a characteristic not described in prior studies. The clinical significance of this finding is not currently known and requires additional study.

Limitations

This was a small convenience sample of patients which limits the generalizability of our findings. A larger sample size would more accurately describe sonographic findings and assist in grading the degree of envenomation and clinical decision making. All the patients in our study received treatment with Fab AV. Our protocol for patients envenomated by copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix) snakes included our local typical method of a four-vial bolus to achieve control, no maintenance, and limb elevation. We cannot comment on the utility of POCUS in patients envenomated by other snake species, or those not requiring Fab AV or without limb elevation, or with the full Fab AV regimen or Crotalidae immune F(ab’)2 (Equine) antivenom. Although we did not perform enough repeat ultrasound examination on discharge, there may be a benefit in looking at the progression of ultrasound findings to determine “control” or recurrence of envenomation.

Conclusion

Evaluation of the soft tissue effects of Crotalinae envenomated extremities with POCUS uniformly revealed subcutaneous edema that did not include fascia or large muscles. None of the envenomated digits that showed edema of the tendon and tendon sheath required acute surgical intervention. POCUS identified signs of envenomation proximal to the physical exam findings, however, the clinical significance of this is unknown.

References

- Lavonas EJ, Ruha AM, Banner W, et al. Unified treatment algorithm for the management of crotaline snakebite in the United States: results of an evidence-informed consensus workshop. BMC Emerg Med. 2011;11:2.

- Walker JP, Morrison RL. Current management of copperhead snakebite. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212(4):470–474; discussion 474–5.

- Cumpston KL. Is there a role for fasciotomy in Crotalinae envenomations in North America? Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49(5):351–365.

- Vohra R, Rangan C, Bengiamin R. Sonographic signs of snakebite. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2014;52(9):948–951.

- Gasanov SE, Dagda RK, Rael ED. Snake venom cytotoxins, phospholipase A2s, and Zn2+-dependent metalloproteinases: mechanisms of action and pharmacological relevance. J Clin Toxicol. 2014;4(1):1000181.

- Wood D, Sartorius B, Hift R. Ultrasound findings in 42 patients with cytotoxic tissue damage following bites by South African snakes. Emerg Med J. 2016;33(7):477–481.