Abstract

Objectives

To define the care cascade for patients with serious injection drug use related infections (SIRI) in a tertiary hospital system and compare outcomes of those who did and did not participate in an opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment referral program.

Methods

The medical records of patients admitted with both OUD and SIRI including endocarditis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, epidural abscess, thrombophlebitis, myositis, bacteremia, and fungemia from 2016-2019 were retrospectively reviewed. Patient demographics, clinical covariates, 90-day readmission rates, and outcomes data were collected. We compared data from those who were successfully referred to outpatient care through Engaging Patients in Care Coordination (EPICC), a peer recovery specialist-run OUD treatment referral program, to those who did not receive outpatient referral.

Results

During the study period 334 persons who inject opioids were admitted with SIRI. Fourteen admitted patients died and were excluded from the analysis. The all-cause readmission rate was lower among patients referred to the EPICC program (18/76 [23.7%]) compared to those not referred to EPICC (100/244 [41.0%]) (OR 0.44; 95% CI 0.25–0.80).

Conclusion

An OUD care cascade evaluation for patients with SIRI demonstrated that referral to peer recovery services with outpatient OUD treatment was associated with reduced 90-day readmission rate.

Introduction

The opioid crisis is spurring a concurrent epidemic of life-threatening injection drug use (IDU) related infections. Persons who inject drugs (PWID) experience increased rates of blood-borne infections such as Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and the viral hepatitides [Citation1]. Importantly, PWID also have increased risk for serious injection related infections (SIRI) such as infective endocarditis, osteomyelitis, epidural abscesses and septic arthritis. Some regions of the United States have seen up to 12-fold increases in infective endocarditis [Citation2–4]. Recent work demonstrates improved outcomes in PWID with invasive infections when addiction medicine consultants are included in their in-hospital care [Citation5, Citation6].

Barnes-Jewish Hospital (BJH) began offering addiction medicine consultations for PWID admitted with invasive bacterial infections in 2016. Since initiation, more providers are aware of the service but consultation is still not mandatory. One year later, the Engaging Patients in Care Coordination (EPICC) program was formed. EPICC is an outreach program for patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) across the St. Louis metropolitan region that provides recovery coaching and bridge services between the inpatient encounter and post-discharge care, with the goal of facilitating outpatient follow-up and medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD).

Building on the successful HIV care cascade model, which enabled unified public health interventions, some have suggested applying a similar care cascade to OUD [Citation7, Citation8]. Proposed care cascade models focus on emphasizing progressive stages specific to those already identified as having OUD [Citation6]. For patients with IDU-related infections this would include initiation of MOUD, engagement in care, and ultimately retention in care including counseling and other psychosocial services. The objective of this study was to describe the care cascade for patients with SIRI in a quaternary care hospital and compare outcomes to those who did not participate in the care cascade.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort analysis of PWID who used opioids and were admitted with SIRI between January 2016 and July 2019 to BJH, a 1400-bed, academic, quaternary center in St. Louis, Missouri. Those who received an infectious diseases consultation for endocarditis, epidural abscess, septic arthritis, Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia, thrombophlebitis, myositis, fungemia, or osteomyelitis/discitis were identified and verified by medical record review as described previously () [Citation5]. Admission records were then individually reviewed by an author for substance use patterns and retention in care data (L.R.M., A.U., and D.B.L.). EPICC referral data were abstracted from the medical provider notes or from the list of patients in the EPICC database. Retention in care data were available only for patients referred to the EPICC program which connects admitted patients to outpatient treatment centers across the St. Louis region. The EPICC program is available 24 h per day at the discretion of the treating team. When EPICC is contacted, a recovery coach is dispatched within 24 h to see the patient at bedside, schedule outpatient follow-up, and provide intranasal naloxone. Patients are free to contact their recovery coach at any time. Engagement in post-discharge care was defined as working with a recovery coach or attending a post-discharge visit at any EPICC treatment facility within the first 30 days after hospital discharge. We defined continuation on MOUD at 30- and 90-days as attending a clinic visit with a prescription for buprenorphine or attendance at a methadone clinic.

Table 1. ICD-9 and ICD 10 codes used to screen for infectious complications of substance use.

Patient demographics, clinical covariates, 90-day readmission rates, and outcomes data were also collected. We compared data from patients successfully referred to outpatient care through the EPICC program to those who were not referred to EPICC. We defined successful referral as finding the patient in a database kept by EPICC meaning that a member of the treating team called this outside organization with the patient’s name and biographical data thereby completing the referral. Due to the retrospective design of this study, the reasons patients were not referred to EPICC were unavailable. Demographic and clinical characteristics were compared using Fisher’s exact tests and Mann-Whitney U test for categorical variables and continuous variables, respectively. This study was approved by the Washington University Institutional Review Board with a waiver of consent due to its retrospective observational design.

Results

Cohort demographics

Our cohort of patients included 334 PWID admitted to BJH with SIRI between January 2016 and July 2019. Fourteen patients died during hospital admission and were excluded from analysis. The remaining 320 patients were included in the analysis. provides the demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort. Patients successfully referred to the EPICC program for linkage to outpatient OUD treatment in the St. Louis area were more likely to be African American (56.6% vs. 39.3%; p = 0.008) and identify as unhoused (26.3% vs. 9.8%; p < 0.001) than those who were not referred. HCV infection was more common (86.8% vs. 60.2%; p < 0.001) in the EPICC referral group compared to those not referred. Other comorbidities were comparable between the two groups. No significant differences in the type of SIRI was identified between the referral and non-referral groups. EPICC referral was more common among those with an addiction medicine consultation (90.7% vs. 33.6%; p < 0.001). No patients in this cohort chose to receive naltrexone.

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of patients who inject opioids admitted with serious injection related infections (SIRI).

Outcomes of OUD care cascade

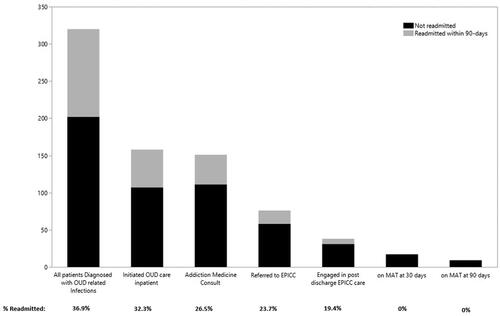

Time-points in our care cascade include diagnosis of OUD in the setting of a SIRI, initiation of MOUD during the inpatient encounter, engagement in post-discharge care, as well as 30- and 90-day retention on MOUD (). Significant drop-offs in retention within the care cascade occurred between initiation of MOUD during the inpatient encounter, referral to post-discharge care through EPICC, and engagement in post-discharge care (). Of the 320 patient admissions included in this review, 158 initiated MOUD during the inpatient encounter and 76 were referred to post-discharge care through the EPICC program.

Figure 1. SIRI, serious injection related infection; OUD, opioid use disorder; MOUD, medication for opioid use 2 disorder; EPICC, engaging patients in care coordination.

Retention at each step in the care cascade was associated with improved outcomes. Of the 158 patients who received MOUD, 51 (32.3%) were readmitted within 90 days compared to 67 of 162 patients (41.4%) not started on MOUD (OR 0.68; 95% CI 0.43–1.07). The all-cause readmission rate was lower among patients referred to the EPICC program (18/76 [23.7%]) compared to those not referred (100/244 [41.0%]) (OR 0.44; 95% CI 0.25–0.80). Continued treatment with MOUD after discharge was associated with reduced readmissions at each time-point.

Discussion

We have described an OUD care cascade in a retrospective cohort of 320 patients admitted with SIRI between 2016 and 2019. Our results reveal a protective effect of engagement in post-discharge OUD care for patients with SIRI. They also highlight a concerning drop-off between inpatient OUD care and engagement in outpatient care. This work provides an important road-map for future efforts in this area.

Our data demonstrate that this crucial service provides tangible readmission benefits for patients who are referred to the program and continue to engage with the care coordination service following discharge. As such, it would benefit healthcare systems to invest resources to improve retention in outpatient treatment.

Frameworks for the cascade of care are most notably outlined by Williams et al. [Citation7]. Their framework includes several steps – primary prevention, secondary prevention (screening for those at risk of OUD), diagnosis, engaging patients in care, initiation of MOUD, 6-month retention, and finally, remission [Citation7]. Important barriers to remaining in care include housing status, involvement with the justice system, non-substance related psychiatric comorbidity, patient beliefs regarding MOUD and treatment of substance use disorders, and concurrent use of other drugs [Citation7].

Limitations of this study include its single center retrospective design. Substance use patterns vary widely across different geographic areas including both rural and urban populations, and these patterns may influence engagement in post-discharge care [Citation9]. Data on patients who were offered MOUD but declined treatment may not be captured by documentation review. This population may also be different than those patients who were successfully referred for EPICC follow up. Many patients in the cohort were not referred to EPICC and due to the study design the reason for non-referral was unavailable but may indicate an area where care can be improved. Lack of referral may have been due to lack of awareness of the service, geographic constraints, or due to the patient declining. Addiction medicine consultation appeared to be associated with patients being referred to EPICC, however, more than half of the cohort who received this consult were not referred. Furthermore, data for care engagement and MOUD retention were only available if patients attended a center or clinic participating in the EPICC program. Regardless, our data demonstrate the benefit of offering a model of care to hospitalized patients with OUD and SIRI that includes appropriate follow up.

Despite data demonstrating the significant benefit of MOUD on mortality and infection incidence [Citation10, Citation11], significant gaps remain in incorporating MOUD into inpatient and outpatient care of patients with injection-related infections.

Conclusion

We describe a care cascade for OUD in patients with SIRI and identify key areas for future interventions. Engagement in this care cascade is associated with reduced 90-day readmission rate. Initiation of MOUD for admitted patients with SIRI and connecting them to outpatient treatment has the potential to improve outcomes and should be offered to all patients. Further work should identify the causes of patients discontinuing engagement in the care cascade.

Acknowledgements

Alison Kraus, MS, and Jennifer Brophy, ScM.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no financial benefits or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Larney S, Peacock A, Mathers BM, et al. A systematic review of injecting-related injury and disease among people who inject drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;171:39–49.

- Schwetz TA, Calder T, Rosenthal E, et al. Opioids and infectious diseases: a converging public health crisis. J Infect Dis. 2019;220(3):346–349.

- Ronan MV, Herzig SJ. Hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and associated serious infections increased Sharply, 2002-12. Health Aff (Millwood)). 2016;35(5):832–837.

- Fleischauer AT, Ruhl L, Rhea S, et al. Hospitalizations for endocarditis and associated health care costs among persons with diagnosed drug dependence – North Carolina, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(22):569–573.

- Marks LR, Munigala S, Warren DK, et al. Addiction medicine consultations reduce readmission rates for patients with serious infections from opioid use disorder. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(11):1935–1937.

- Englander H, Dobbertin K, Lind BK, et al. Inpatient addiction medicine consultation and post-hospital substance use disorder treatment engagement: a propensity-matched analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(12):2796–2803.

- Williams AR, Nunes EV, Bisaga A, et al. Development of a cascade of care for responding to the opioid epidemic. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2019;45(1):1–10.

- Yedinak JL, Goedel WC, Paull K, et al. Defining a recovery-oriented cascade of care for opioid use disorder: a community-driven, statewide cross-sectional assessment. PLoS Med. 2019;16(11):e1002963.

- SAMHSA. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. 178. 2013. [cited 2020 Dec 22]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHnationalfindingresults2012/NSDUHnationalfindingresults2012/NSDUHresults2012.htm.

- Larochelle MR, Bernson D, Land T, et al. Medication for opioid use disorder after nonfatal opioid overdose and association with mortality: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(3):137–145.

- Wakeman SE, Larochelle MR, Ameli O, et al. comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1920622.