Abstract

Diphenhydramine (DPH) is a lipophilic inverse agonist at the histamine receptor. Overdoses usually present with anticholinergic symptoms. Wide-complex tachycardia decompensating into cardiovascular collapse may occur in larger overdoses. Here we report a patient who developed ventricular dysrhythmias after ingestion of 83 mg/kg of diphenhydramine, went into cardiovascular collapse that was rescued with early administration of intravenous lipid emulsion.

Introduction

Diphenhydramine (DPH) is a lipophilic histamine inverse agonist that readily crosses the blood-brain barrier [Citation1]. It is commonly referred to as an antihistamine, a usage we follow in this report. DPH is the most commonly reported antihistamine taken in overdose; however, fatal ingestions are rare [Citation2]. Large DPH ingestions are associated with wide-complex tachycardia, seizures, and death [Citation3,Citation4], reflecting its sodium channel blocking (type IA antidysrhythmic), antimuscarinic, and serotonergic properties.

Intravenous lipid emulsion (ILE) was first described as a rescue agent for cardiovascular collapse from lidocaine and bupivacaine [Citation5]. Case reports suggest it may rescue cardiovascular collapse from other lipid-soluble or cardioactive drugs, including DPH, beta-blockers [Citation6], calcium channel blockers [Citation7], quetiapine and sertraline [Citation8], as well as parasiticides and herbicides [Citation9]. However, cardiac arrest occurred within one minute after administering ILE in 2 cases of cardiogenic shock after massive diltiazem ingestion [Citation8]. Systematic research on the efficacy for ILE outside local anesthetic toxicity is lacking, although there is a recent systematic review of preclinical data [Citation10]. In 2011, the American College of Medical Toxicologists made no recommendation for or against the use of ILE [Citation9].

Here, we report a case of a patient refractory to standard treatment after a massive diphenhydramine ingestion in whom ILE averted cardiovascular collapse.

Case presentation

A 30-year-old 90 kg female with schizophrenia presented to our Emergency Department after an intentional ingestion of DPH. The patient was in her usual state of health until her family found her one hour prior to arrival with generalized shaking next to a newly purchased and completely empty bottle of Benadryl™. The estimated ingestion was 300 × 25 mg capsules (7.5 grams total, 83 mg/kg). The patient’s home medications include fluphenazine, lithium, ziprasidone, temazepam, and lansoprazole, all of which were accounted for.

Actions in the field. Emergency medical services (EMS) found the patient obtunded, hypotensive (no blood pressure recorded), and with a wide complex tachycardia (rate 190 beats per minute). En route she had 2 witnessed generalized seizures for which she received by IV 2 mg lorazepam, 150 mg amiodarone, and 500 mL 0.9% saline bolus.

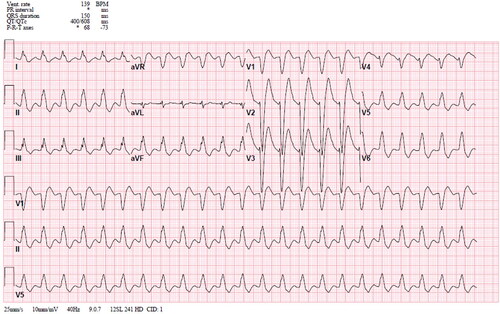

Actions in the Emergency Department (ED). The patient arrived to the ED obtunded after less than 10 min in transit. Her initial axillary temperature was 36.2 C, heart rate 155 beats per minute, respiratory rate 30 breaths per minutes, blood pressure 151/66 mm Hg, and fingerstick glucose 173 mg/dL. Her physical exam was notable for minimally reactive, dilated pupils (6–7 mm) with horizontal nystagmus, flushed dry skin, shallow respirations, and no response to painful stimuli. She underwent endotracheal intubation and received a IV bolus of 150 mEq (3 × 50 mL of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate) and was then started on an infusion of sodium bicarbonate (150 mEq sodium bicarbonate diluted in 850 mL water with 5% dextrose) at 100 mL/hr, after which her heart rate decreased to the 130 s. Her initial EKG () demonstrated a wide complex tachycardia (QRS 150 ms, QTc 608 at 139 bpm). She received an additional 100 mEq of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate and underwent gastric lavage with a 16 Fr orogastric tube and 3 L normal saline total with the removal of copious pink pill sediment. An EKG after these interventions demonstrated a heart rate of 129 bpm, QRS duration 134 ms and QTc of 475 ms. Poison control recommended continued supportive care. Her laboratory studies were remarkable for bicarbonate 14 mEq/L, potassium 3.7 mEq/L, Mg 2.1 mEq/L (anion gap 25 mEq/L, delta gap 1.1). An arterial blood gas drawn after intubation and sodium bicarbonate administration demonstrated pH 7.44, pCO2 47 mm Hg, pO2 244 mm Hg, HCO3 31 mEq/L. Serum ethanol, salicylate, and acetaminophen concentrations were undetectable.

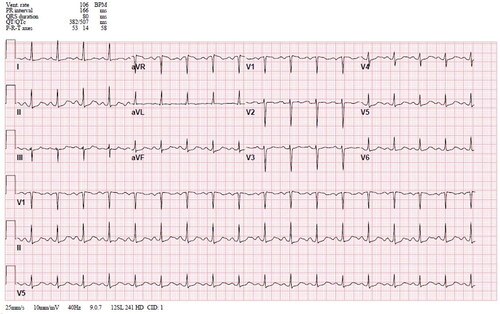

Thirty-five minutes later, the patient became hypotensive with a systolic blood pressure of 90/54 mmHg, measured by peripheral cuff. A repeat EKG was unchanged from the immediately previous one. She received a 120 mL bolus of 20% IV lipid emulsion (Intralipid®) based upon a dosing weight of 80 kg. Less than 1 min later, the patient converted to a narrow complex rhythm at an improved rate (QRS 80 ms, QTc 507 at 106 BPM, ), and her blood pressure improved to 135/92 mm Hg. She received an IV lipid emulsion infusion at 0.25 mL/kg/min over 12.5 min (total infusion 250 mL after the bolus) and was continued on the sodium bicarbonate infusion at 100 mL/hr. The patient remained sedated with midazolam at 10 mg/hr and fentanyl at 25 mcg/hr, and was admitted to the intensive care unit. In the ICU, she received an additional infusion of 10 mL/h (approximately 0.002 mL/kg/min) over the next 8 h for total dose of 80 mL in the ICU). The rationale for the dosing of this second infusion was not documented. Between the ED and the ICU, her combined total dose of ILE was 450 mL.

Figure 2. Electrocardiogram 30 min after initiation lipid emulsion bolus, demonstrating narrowing of QRS complex, narrowing of the QTc interval, and improvement of heart rate.

Actions in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). On arrival in the ICU a propofol infusion at 50 mcg/kg/min was added for sedation. Her initial ventilator settings were assist-control mode, volume-cycled, with a tidal volume of 450 mL, RR of 16 per minute, FiO2 of 100%, and a PEEP of 5 cm H2O. The lipid emulsion infusion was discontinued 7 h after initiation due to hemodynamic improvement. An EKG 2 h after discontinuation demonstrated maintenance of sinus rhythm, rescue of QRS duration and partial rescue of QTcB prolongation (from 608 ms with heart rate of 66 bpm to 507 ms (70 bpm) to 538 ms (86 bpm)). The sodium bicarbonate infusion was continued overnight. The following morning, a third ECG (10 h after discontinuation of lipid therapy) demonstrated a heart rate of 93 beats per minute, QRS of 82 ms and QTc of 499 ms. The sodium bicarbonate infusion was discontinued, and the patient was extubated, neurologically intact. Her lipase was elevated at 721 U/L the next morning. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis was not performed. The patient developed no signs of respiratory distress nor any abdominal pain. She remained hemodynamically stable for the rest of her hospital admission. On the third day of ICU admission, a final ECG demonstrated a heart rate of 93 beats per minute, QRS of 80 ms and QTc of 495 ms. She was subsequently transferred to the behavioral health unit.

Discussion

We present the case of a 30 year-old woman on multiple psychiatric medications who presented obtunded with a wide-complex tachycardia that devolved into cardiogenic shock one hour after a likely overdose of diphenhydramine. Her nearly immediate response to lipid emulsion suggests that ILE was pivotal in her resuscitation, although she received many other medications simultaneously and was on a sodium bicarbonate infusion before, during, and after lipid emulsion therapy. We did not obtain serum diphenhydramine concentrations because the clinical scenario was highly suggestive of and exam findings consistent with a diphenhydramine-dominant ingestion.

This patient received 250 mEq 8.4% sodium bicarbonate and a sodium bicarbonate infusion at a rate of 100 mL/hr for approximately 30 min before receiving ILE. After the second bolus her heart rate decreased and QRS improved, but she remained hypotensive with a prolonged QTc. It is unlikely that the sodium bicarbonate precipitated an intracellular shift of potassium that prolonged the QT. Her serum potassium concentration, drawn in between the sodium bicarbonate and lipid emulsion boluses, was 4.2 mmol/L.

ILE is most studied for the treatment of cardiovascular toxicity from local anesthetics [Citation11,Citation12]. Its use for other lipophilic or sodium channel blocking drugs has been described in case reports [Citation13]. Diphenhydramine in overdose behaves as a Vaughn-Williams type IA sodium channel blocker. The mechanism of action of ILE is best understood in the treatment of local anesthetic toxicity [Citation14,Citation15]. Most overdoses in which published cases report benefit of ILE involve lipid soluble xenobiotics, suggesting a similar mechanism of benefit for lipid emulsion therapy in those cases.

Our case illustrates that lipid emulsion therapy can reverse hypotension and dysrhythmias precipitated by DPH toxicity that could otherise devolve into cardiac arrest, similar to two prior case reports [Citation16,Citation17]. These case reports and ours suggest that ILE may have use earlier in resuscitation, paralleling an assertion that lipid emulsion is most beneficial for cardiac arrest from local anesthetics if given close to peak serum concentration of the local anesthetic [Citation14,Citation18]. A systematic review may better establish the role of lipid emulsion therapy in cardiotoxicity from DPH ingestion.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Hoffman RS, Howland MA, Lewin NA, et al. Goldfrank’s toxicologic emergencies (ebook). New York, NY, USA: McGraw Hill Professional; 2014.

- Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2017 annual report of the American association of poison control Centers' National Poison Data System (NPDS): 35th annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2018;56(12):1213–1415.

- Abdelmalek D, Schwarz ES, Sampson C, et al. Life-threatening diphenhydramine toxicity presenting with seizures and a wide complex tachycardia improved with intravenous fat emulsion. Am J Ther. 2014;21:542–544.

- Nishino T, Wakai S, Aoki H, et al. Cardiac arrest caused by diphenhydramine overdose. Acute Med Surg. 2018;5(4):380–383.

- Whiteman DM, Kushins SI. Successful resuscitation with intralipid after marcaine overdose. Aesthet Surg J. 2014;34(5):738–740.

- Brumfield E, Bernard KRL, Kabrhel C. Life-threatening flecainide overdose treated with intralipid and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33:1840.e3–1840.e5.

- French D, Armenian P, Ruan W, et al. Serum verapamil concentrations before and after Intralipid® therapy during treatment of an overdose. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49(4):340–344.

- Finn SDH, Uncles DR, Willers J, et al. Early treatment of a quetiapine and sertraline overdose with Intralipid®. Anaesthesia. 2009;64(2):191–194.

- American College of Medical Toxicology. ACMT position statement: interim guidance for the use of lipid resuscitation therapy. J Med Toxicol. 2011;7:81–82.

- Fettiplace MR, Pichurko AB. Heterogeneity and bias in animal models of lipid emulsion therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Toxicol. 2020:1–11.

- Dix SK, Rosner GF, Nayar M, et al. Intractable cardiac arrest due to lidocaine toxicity successfully resuscitated with lipid emulsion. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(4):872–874.

- Levine M, Hoffman RS, Lavergne V, et al. Systematic review of the effect of intravenous lipid emulsion therapy for non-local anesthetics toxicity. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2016;54(3):194–221.

- Cevik SE, Tasyurek T, Guneysel O. Intralipid emulsion treatment as an antidote in lipophilic drug intoxications. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(9):1103–1108.

- Fettiplace MR, Lis K, Ripper R, et al. Multi-modal contributions to detoxification of acute pharmacotoxicity by a triglyceride micro-emulsion. J Control Release. 2015;198:62–70.

- Fettiplace MR, Weinberg G. The mechanisms underlying lipid resuscitation therapy. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(2):138–149.

- Cherukuri SV, Purvis AW, Tosto ST, et al. IV lipid emulsion infusion in the treatment of severe diphenhydramine overdose. Am J Case Rep. 2019;20:758–763.

- Abdi A, Rose E, Levine M. Diphenhydramine overdose with intraventricular conduction delay treated with hypertonic sodium bicarbonate and IV lipid emulsion. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15(7):855–858.

- Dureau P, Charbit B, Nicolas N, et al. Effect of intralipid® on the dose of ropivacaine or levobupivacaine tolerated by volunteers: a clinical and pharmacokinetic study. Anesthesiology. 2016;125(3):474–483.