Abstract

Caffeine induces neurological effects at high doses. However, the duration and extent of neurological manifestations with respect to serum theophylline and caffeine concentrations is unknown. A 19-year-old woman suffering from severe caffeine overdose showed signs of neurological effects that persisted for more than 60 h despite hemodialysis and the normalization of caffeine and theophylline concentrations. Although serum theophylline and caffeine concentrations can be used to monitor the effect of severe caffeine overdose, central nervous system toxicity may persist after the concentrations normalize.

Introduction

Caffeine is a widely recognized psychostimulant compound with a long history. It is widely available in stores and online without a prescription as an additive in consumer products such as supplements, energy drinks, and sleep-preventing medications; this has led to a corresponding increase in patients with caffeine toxicity [Citation1]. Caffeine induces central nerve excitability, smooth muscle relaxation, cardiac muscle stimulation, and diuresis. The enhancement of these effects can cause headache, irritability, insomnia, hallucinations, delirium, and coma [Citation2]. This is concerning because the cardiovascular effects of caffeine, especially ventricular tachycardia, can cause of death [Citation2]. In spite of cases of caffeine intoxication with neurological effects reported, the detailed course of neurological effects is unknown, and the relationship between serum caffeine and theophylline concentrations is unclear. Hospital laboratories in North America often measure theophylline on site but usually outsource caffeine tests.

I report a rare case of caffeine overdose in which the neurological effects persisted more than 60 h despite the normalization of caffeine and theophylline concentrations.

Case report

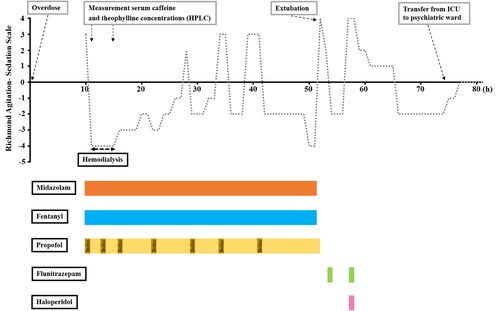

A 19-year-old woman with prolonged agitation and ventricular tachycardia after ingesting approximately 7.2 g of pure caffeine anhydrous, was transferred from another hospital to our hospital. The patient had no past medical or psychiatric history and was not on medications. Her vital signs were temperature 36.4 °C, pulse 93 bpm, and blood pressure 76/47 mmHg. Blood tests were normal. Ventricular tachycardia, present prior to admission to our hospital, had resolved. There were no physical or psychological factors that could have caused her symptoms. Thus, we diagnosed her with sympathomimetic toxidrome. Despite gastric lavage at the other hospital, the patient's blood caffeine concentration was ∼113 μg/mL (approximately 10 h post overdose), resulting in prolonged agitation and ventricular tachycardia. After hemodialysis (4 h), the caffeine concentration declined to 31 ug/mL while theophylline was undetectable. Blood caffeine and theophylline concentrations were measured using high performance liquid chromatography. After hemodialysis, serum caffeine and theophylline concentrations declined (), and the patient returned to sinus rhythm. However, her symptoms of restlessness and agitation (Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale score of +2 to +4) persisted for more than 60 h after caffeine intake. Sedatives were used to treat agitation and impulsivity during that period. While at the Intensive Care Unit, she received midazolam (0.03–0.18 mg/kg/hr intravenously [IV]), fentanyl (1–2 μg/kg/hr IV), and propofol (0.5–3 mg/kg/hr IV with a bolus dose of 2 mg/kg). The administration of sedatives was required for more than 50 h, since the patient became agitated whenever they were reduced. After extubation and transfer out of the ICU, she received flunitrazepam (8 mg IV) and haloperidol (1 mg IV). Although a certain therapeutic efficacy was achieved, the patient was moved from the ICU to the psychiatric ward, to monitor possible relapses. However, there was no recurrence of the neurological effects. illustrates her clinical course.

Table 1. Changes in serum caffeine and theophylline concentrations before and after hemodialysis.

Discussion

Caffeine is a mild central nervous stimulant, rapidly absorbed through the intestinal tract after oral ingestion. Normally, it has a half-life of 4–6 h; but in cases of overdose, the half-life extends to approximately 15 h. In spite of cases of caffeine intoxication with neurological effects reported, the detailed course of neurological effects and the association between their duration and the serum caffeine concentrations is unknown.

Kitamura et al. [Citation3] reported that caffeine blood levels do not correlate with intensity of central nervous system excitatory effects. Xanthine derivatives (e.g. paraxanthine, theobromine, and theophylline) are products of caffeine metabolism that are believed to have effects similar to those of caffeine. Xanthine derivatives may account for persistent psychiatric symptoms when caffeine concentrations fall. In the present case, the blood concentration of theophylline was below sensitivity after hemodialysis. However, the actual blood concentration of xanthine derivatives may have been higher because caffeine is primarily metabolized to paraxanthine; while only ∼4% of caffeine is metabolized to theophylline [Citation3]. In addition, whether the patient had other illnesses (e.g. psychiatric disorders and ICU delirium) is unknown.

Kapur et al. reported on a patient who overdosed on 20 g of caffeine pills; that patient had blood caffeine and theophylline concentrations of 72.5 µg/mL and 2.8 µg/mL, respectively [Citation4]. Our case, together with that report, suggests that the ratio of caffeine to theophylline is approximately 1/25. Thus, we conclude that blood theophylline concentrations can be used for monitoring caffeine overdoses, but whether they can used for therapeutic monitoring requires further research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Davies S, Lee T, Ramsey J, et al. Risk of caffeine toxicity associated with the use of ‘legal highs’ (novel psychoactive substances). Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68(4):435–439.

- Simone C, Mariarosaria A, Vittorio F, et al. Caffeine-related deaths: manner of deaths and categories at risk. Nutrients. 2018;10:611.

- Kitamura J, Miyabe H, Uenishi N, et al. Two cases of fatal caffeine poisoning. J Jpn Soc Emerg Med. 2014;17:711–715.

- Kapur R, Smith MD. Treatment of cardiovascular collapse from caffeine overdose with lidocaine, phenylephrine, and hemodialysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27(2):253.e3–253.e6.