Abstract

Glycopyrronium is an antimuscarinic drug that is available in a moist towelette preparation for the treatment of primary axillary hyperhidrosis, which is characterized by excessive sweating on the palms, soles of feet, and axillary region. Antimuscarinic toxicity is uncommon with therapeutic use. A 25-year-old female presented to the emergency department with urinary retention and visual changes after initiating topical glycopyrronium tosylate therapeutically. She was tachycardic with a heart rate of 115 beats/min and required a Foley catheter for urinary retention of over 1200 mL. She received 1.5 mg physostigmine for antimuscarinic symptoms and her heart rate improved. Despite treatment, she required a Foley catheter for four days with eventual improvement. This case demonstrates side effects of an unusual preparation of glycopyrronium and the need to take a detailed topical medication history in patients with antimuscarinic symptoms.

Keywords:

Introduction

Glycopyrrolate, or glycopyrronium, is an antimuscarinic drug that is used in both the operative setting and in palliative care. It’s antimuscarinic effects are mediated via antagonism at both M1 and M3 receptors. Secretion from sweat glands is primarily mediated through M3 receptors [Citation1]; therefore, glycopyrrolate is used for the management of hyperhidrosis [Citation2]. Primary axillary hyperhidrosis (PAH) affects 4.8% of the population and is characterized by sweating in excess of the amount needed to maintain normothermia in the axillary region [Citation3]. Qbrexza® (glycopyrronium tosylate) is a topical formulation of glycopyrronium which is FDA approved for PAH. The package insert lists urinary retention as a warning [Citation4], however, an open label study evaluating adverse effects with use of topical glycopyrronium found antimuscarinic effects to be uncommon [Citation5]. Here, we report a case of antimuscarinic toxicity from therapeutic use of topical glycopyrronium tosylate treated with physostigmine.

Case report

A 25-year-old female with a past medical history of PAH presented to the emergency department with anxiety, the inability to urinate, and blurry vision in bright light of three days duration. She was prescribed Qbrexza® (2.4% glycopyrronium tosylate) moist towelettes for hyperhidrosis and reported using 1 sheet daily as directed. Vital signs were: heart rate 115 beats/min, temperature 37.2 C (99.0 °F), respiratory rate 18 breaths/min, blood pressure 118/80 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation of 97% on room air. Physical examination revealed 6 mm sluggishly reactive pupils, dry and flushed skin, dry mucus membranes, tachycardia, absent bowel sounds, and a distended, palpable bladder. She was alert and oriented. Urinary catheterization revealed 1,200 mL of urine. An electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia with a QRS duration of 80 msec and QTc of 464 msec (Bazett). Blood work including a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, acetaminophen, and salicylate concentrations were unremarkable. A glycopyrronium concentration was not obtained as this was not immediately available. The patient received 1.5 mg of intravenous physostigmine over 5 min with improvement in her heart rate and anxiety. She required a Foley catheter at discharge for persistent inability to void. The glycopyrronium was discontinued. At follow up four days later, she had a complete recovery and the Foley catheter was removed.

Discussion

PAH results from abnormal autonomic nervous system activity and is stimulated by emotional triggers, resulting in excess sweating. The underlying pathophysiology of this disorder is not completely understood. Treatment aims at decreasing sweat production via duct closure or through reduction of acetylcholine transmission at the muscarinic receptor. This is achieved with topical aluminum salts, botulinum toxin, iontophoretic treatments, and antimuscarinic compounds [Citation6]. Antimuscarinic agents like glycopyrronium work via competitive inhibition of acetylcholine at the muscarinic receptor, such as the M3 receptor in glandular tissue, ultimately resulting in decreased glandular activity and perspiration [Citation6].

The antimuscarinic effect of glycopyrronium at glandular tissue is desired in PAH to reduce perspiration however the other widespread antimuscarinic effects are undesirable. Antimuscarinic toxicity is characterized by tachycardia, mydriasis, urinary retention, decreased gastrointestinal activity, decreased saliva and sweat production as well as delirium [Citation7]. Symptomatic antimuscarinic toxicity requiring treatment is uncommonly reported with the therapeutic use of topical glycopyrronium tosylate [Citation5]. Mild symptoms, such as dry mouth and mydriasis are reported more commonly, at approximately 24%. Urinary retention is rare, occurring in 1.5% of patients [Citation2]. A longer, open-label study found a higher rate of urinary hesitancy at 4.2% [Citation5]. Topical glycopyrronium is to be applied once daily to the axilla only, with prompt hand washing after application. With improper use, side effects such as dry mouth, mydriasis, hoarse voice, and anisocoria occur [Citation8]. Our patient reported that she used the topical glycopyrronium as directed.

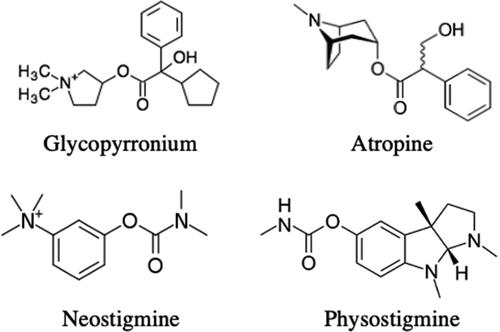

Antimuscarinic toxicity is treated with physostigmine, a reversible acetylcholinesterase inhibitor (AChEI). Physostigmine has a tertiary structure and is typically reserved for antimuscarinic delirium as it will cross the blood brain barrier. Glycopyrronium is a quaternary ammonium compound () and therefore is not expected to cross the blood brain barrier or cause central nervous system (CNS) effects [Citation1]. Our patient did not present with CNS effects. Given the severity of her symptoms, however, this patient received physostigmine with an aim of eliminating a urinary catheter at discharge. Glycopyrronium has a half-life of 2-3 h when given orally. In volunteer studies, half-life of topical glycopyrronium was unable to be determined due to low systemic concentrations but is recommended for once daily use [Citation4,Citation9]. Intravenous physostigmine has a half-life of 40 min and a duration of effect up to 90 min [Citation10]. Unfortunately, even after a sustained resolution of her tachycardia and other antimuscarinic effects, her urinary retention persisted, requiring a urinary catheter at discharge. Urination is mediated primarily through M3 receptors [Citation1], therefore her lack of improvement in urination points to ongoing M3 blockade. She was not given further physostigmine given the risk of bradycardia and adverse CNS effects.

Figure 1. Structures of quaternary ammonium compounds, glycopyrronium (antimuscarinic) and neostigmine (AChEI), compared with tertiary ammonium compounds, atropine (antimuscarinic) and physostigmine (AChEI).

Other treatment options for antimuscarinic toxicity when physostigmine is unavailable include neostigmine and rivastigmine. Neostigmine is also a reversible AChEI, but its quaternary ammonium structure limits CNS penetration. Neostigmine is equal in potency to physostigmine and would have been an acceptable alternative in this patient but was unavailable in this case [Citation1]. Neostigmine is given via slow IV administration of 0.5–2 mg, similar to physostigmine [Citation10]. Although neostigmine is specifically used for urinary retention, it is unclear if neostigmine would have improved this patient’s urinary retention to a greater extent than physostigmine [Citation11]. Rivastigmine is an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor used to treat Alzheimer’s disease and is available in capsules and patches. In contrary to neostigmine, it will cross the blood brain barrier. Dosage of rivastigmine for anticholinergic delirium is 3–6 mg every hour until resolution of symptoms. Dosing of patch formulation is not described. Use of rivastigmine capsules is limited by delirious patients’ ability to take oral medications [Citation12,Citation13].

When taking a medication history, patients often fail to disclose non-traditional medications, such as over-the-counter medications and topical agents. With new emerging formulations of traditional medications, it is important to ask about topical preparations, both prescribed and over the counter, in patients with antimuscarinic symptoms.

Conclusions

Topical glycopyrronium tosylate, although uncommonly reported, causes significant antimuscarinic toxicity with therapeutic use.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

References

- Brown JH, Brandl K, Wess J. Muscarinic receptor agonists and antagonists. In: Brunton LL, Hilal-Dandan R, Knollmann BC, editors. Goodman & gilman’s: the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 13th ed. New York (NY): McGraw-Hill Education; 2017.

- Glaser DA, Hebert AA, Nast A, et al. Topical glycopyrronium tosylate for the treatment of primary axillary hyperhidrosis: Results from the ATMOS-1 and ATMOS-2 phase 3 randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(1):128–138.e2.

- Liu V, Farshchian M, Potts GA. Management of primary focal hyperhidrosis: an algorithmic approach. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20(5):523–528.

- Qbrexza (glycopyrronium tosylate) [package insert]. Menlo Park (CA): Demira, Inc.; 2018.

- Glaser DA, Hebert AA, Nast A, et al. A 44-week open-label study evaluating safety and efficacy of topical glycopyrronium tosylate in patients with primary axillary hyperhidrosis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20(4):593–604.

- Lakraj AA, Moghimi N, Jabbari B. Hyperhidrosis: anatomy, pathophysiology and treatment with emphasis on the role of botulinum toxins. Toxins (Basel). 2013;5(4):821–840.

- Rumack BH. Anticholinergic poisoning: treatment with physostigmine. Pediatrics. 1973;52(3):449–451.

- Al-Holou SN, Lipsky SN, Wasserman BN. Don’t sweat the blown pupil: anisocoria in patients using qbrexza. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(10):1381.

- Pariser DM, Lain EL, Mamelok RD, et al. Limited systemic exposure with topical glycopyrronium tosylate in primary axillary hyperhidrosis. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2021;60(5):665–676.

- Kearney TE. Chapter 223. Physostigmine and neostigmine. In: Olson KR, editor. Poisoning & drug overdose. 6th ed. New York (NY): The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012.

- Senapathi TGA, Wiryana M, Subagiartha IM, et al. Effectiveness of intramuscular neostigmine to accelerate bladder emptying after spinal anesthesia. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2018;14:1685–1689.

- Van Kernebeek MW, Ghesquiere M, Vanderbruggen N, et al. Rivastigmine for the treatment of anticholinergic delirium following severe procyclidine intoxication. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2021;59(5):447–448.

- Hughes AR, Moore KK, Mah ND, et al. Letter in response to Rivastigmine for the treatment of anticholinergic delirium following severe procyclidine intoxication. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2021;59(9):855–856.