Abstract

Methotrexate toxicity following intravenous (IV) methotrexate is well reported, but there is less information on accidental daily dosing of a prescribed weekly dose of oral methotrexate. A 70 year old female presented following accidentally taking 20 mg methotrexate for five days, with multiple oral ulcers, thrombocytopenia (platelets 80 x 109/L [reference range[RR]:150-400 x 109/L]) and an alanine aminotransferase 820 U/L [RR:10-35 U/L]. Methotrexate was undetectable [<0.04 µmol/L]. She was treated with folinic acid, 15 mg orally and then 15 mg IV every six hours. She became progressively pancytopenic, with the lowest counts occurring days 3-6: Hb, 87 g/L, platelets, 22 x 109/L, neutrophils, 0.0 x 109/L [RR:2-8 x 109/L] and white cell count, 0.6 x 109/L [RR:4-11 x 109/L]. She received 2 units of platelets, filgrastim 300 mcg daily for days 3-7 and IV ceftazidime/gentamicin for a fever. On day 6, her platelet and neutrophil counts began to recover, and her ALT was almost normal on discharge day 9. She had alopecia in the 3 months post-discharge. Our patient developed severe toxicity, consistent with complete absorption and cellular uptake of methotrexate, with slow cellular elimination. She was treated with folinic acid, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor and blood product transfusions.

Introduction

Methotrexate is a competitive folic acid antagonist, most commonly used in chemotherapy and for the treatment of autoimmune diseases [Citation1]. Large datasets in both the United States and Australia have identified errors in dosing frequency as an important cause of severe and potentially fatal toxicity [Citation2–4]. While the effects of acute toxicity following intravenous (IV) methotrexate therapy are well known [Citation5], there are few case reports describing the effects of accidental daily dosing of the oral formulation. The focus in these reports is on methods of preventing dosing errors, rather than descriptions of the clinical effects and patient management. We describe a case of accidental daily methotrexate dosing leading to severe toxicity and discuss the important differences between the clinical course and management of toxicity due to accidental daily dosing versus that of acute toxicity.

Case report

A 70 year-old female was referred to hospital by her local medical officer following accidental daily dosing of methotrexate 20 mg for five days, rather than the prescribed 20 mg weekly dosing. The methotrexate had been commenced 6 weeks prior as a steroid-sparing agent for management of her temporal arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica. Her background history otherwise included type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension and recently diagnosed pulmonary emboli. Her other medications included metformin XR 500 mg twice daily, rivaroxaban 20 mg daily, candesartan 16 mg daily, hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg daily, rosuvastatin 10 mg daily and prednisolone 15 mg daily. She also received azithromycin 500 mg daily several days prior to her presentation for a sore throat.

She presented to her local medical officer with multiple oral ulcers and a sore throat resulting in decreased oral intake secondary to pain. The patient realised she had been accidentally taking methotrexate daily for the past five days due to a mistake in packing her weekly pillbox. On presentation to hospital she denied any other symptoms and her vital signs were all within normal range. She was admitted to hospital, received folinic acid 15 mg orally and then commenced on folinic acid 15 mg IV every six hours.

Her initial laboratory investigations were white cell count (WCC) 6.0 x 109/L [reference range (RR): 4-11 x 109/L], neutrophils 5.5 x 109/L [RR: 2-8 x 109/L], haemoglobin (Hb) 118 g/L [RR: 115-165 g/L], platelets 80 x 109/L [RR: 150-400 x 109/L]. She had a normal full blood count one week prior. She had elevated alanine aminotransferase 820 U/L [RR: 10-35 U/L], aspartate aminotransferase 495 U/L [RR: 10-35 U/L] and gamma-glutamyl transferase 52 U/L [RR: 5-35 U/L], all of which had been normal one month prior. Serum methotrexate was undetectable [<0.04 µmol/L] on admission, approximate 24 h after the last dose.

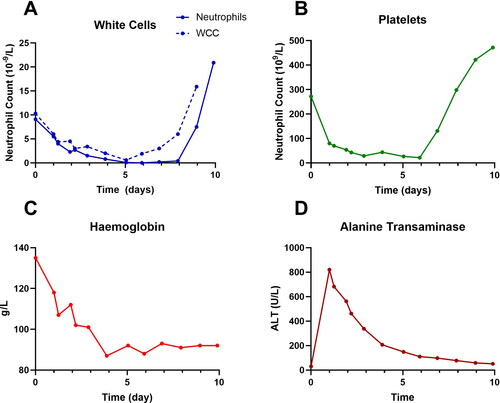

She became progressively pancytopenic, with the lowest blood cell counts occurring between days 3 and 6 for Hb at 87 g/L, platelets at 22 x 109/L, neutrophils at 0.0 x 109/L and WCC at 0.6 x 109/L (). She received 2 units of platelets on days 2 and 5 for thrombocytopenia, and filgrastim 300 mcg daily subcutaneously from day 3 to day 7 for neutropenia. She developed an isolated temperature of 38 °C on day 5 and was treated with IV ceftazidime (2 g every 8 h) and gentamicin (320 mg daily) for 3 days, though no source of infection was identified. She also developed diarrhoea during the admission and subsequent mild hypokalaemia [potassium 3.1 mmol/L [RR 3.5-5.2 mmol/L], which was treated with oral potassium supplementation.

Figure 1. Plots of white cell count and neutrophils (A), platelets (B), haemoglobin (C) and alanine transaminase (ALT) versus time.

Her treatment was further complicated by ongoing need for anticoagulation in the context of recently diagnosed pulmonary embolus and an exacerbation of her temporal arteritis, treated successfully with an increased dose of prednisolone. On day 6, her platelet and neutrophil counts began to recover (), and filgrastim was ceased on day 8 when the neutrophil count was > 1.0 x 109/L. She subsequently experienced a rebound elevation in platelets (472 x 109/L) and WCC (43.6 x 109/L), with neutrophils of 20.9 x 109/L at time of discharge on day 9. The had almost completely normalised by discharge.

Following discharge, she had ongoing rebound leukocytosis with the WCC peaking at 93.8 x 109/L four days after ceasing filgrastim. Her LFTs were normal one month post-discharge, but the WCC did not normalise until two months post-discharge. She also had moderate alopecia during the three months following discharge. Written consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report.

Discussion

Our case highlights the marked difference in toxicity between accidental oral daily therapeutic doses (instead of weekly) and the minimal effects with single oral overdose ingestions, with important implications for prognosis and treatment [Citation6].

The reason for the difference in toxicity between acute overdose and accidental daily dosing is that oral absorption of methotrexate is saturable, with significantly decreased bioavailability at doses over 25 mg/day [Citation1, Citation6, Citation7], and serum concentrations drop rapidly to being undetectable after 24 h, because of a rapid distribution half-life of 2 h and an elimination half-life of 6 to 8 h [Citation6]. The cellular uptake of methotrexate is also saturable [Citation8], so in an acute overdose most of the dose is not absorbed and only a small amount is taken up by cells [Citation6]. With repeated accidental daily ingestions, each dose is fully absorbed and completely taken up by the cells, resulting in accumulation and much greater total exposure. The intracellular elimination half-life of methotrexate active metabolites is 1 to 4 weeks, allowing sufficient excretion to achieve steady therapeutic dosing, if administered weekly [Citation6]. However, with accidental daily administration, this prolonged intracellular elimination half-life results in increased overall exposure.

The slow uptake and elimination from cells, the target site for methotrexate, means that serum methotrexate concentrations do not reflect the severity of toxicity. Serum methotrexate concentrations will be undetectable, while intracellular concentrations will be much higher. This was seen in our patient with undetectable serum methotrexate despite severe toxicity.

Folinic acid, the biologically active form of folic acid, is the main treatment for methotrexate toxicity. Folinic acid decreases the toxic effects of methotrexate via two mechanisms. Methotrexate and folinic acid (not folic acid) compete for the same saturable active transporters for both gastrointestinal absorption [Citation1, Citation6] and cellular uptake [Citation9]. With oral methotrexate toxicity the first dose of folinic acid is administered orally to compete with gastrointestinal absorption of methotrexate [Citation6]. In cases in which there is detectable serum methotrexate, folinic acid by any route will decrease intracellular uptake of methotrexate [Citation9].

The more important role of folinic therapy is to provide activated folic acid (tetrahydrofolate), bypassing methotrexate antagonism, which is essential for purine and pyrimidine synthesis () [Citation6, Citation7]. With repeated daily methotrexate toxicity, the near-complete cellular uptake of methotrexate results in intracellular toxicity and deficiency in activated folic acid. IV folinic acid administration is preferred because of the low oral bioavailability of folinic acid [Citation1, Citation6, Citation7].

In 12 previously published cases of accidental daily dosing of methotrexate, the most frequently reported manifestations are oral ulceration (usually the earliest and presenting complaint), mild hepatitis, pancytopenia and acute renal failure () [Citation10–15]. The majority of deaths were due to infection [Citation11, Citation12, Citation15] with one death documented secondary to multi-organ failure [Citation15], and one unspecified cause of death [Citation12]. A range of folinic acid regimes were used [Citation10, Citation11, Citation13–15], and in cases in which no folinic acid was given, this was based on undetectable methotrexate concentrations () [Citation15].

Table 1. Cases of accidental daily dosing of methotrexate in the existing literature.

Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) was given in three cases, despite neutropenia occurring in all but one case [Citation11, Citation13, Citation14]. In our case, there was a large rebound in the WCC and persistently elevated WCC, suggesting that G-CSF may not be required in all cases, or a lower dose. Platelets were only given in one case [Citation14]. The use of antimicrobials was reported in five of the 12 cases [Citation10, Citation11, Citation13, Citation14], though the indication was unclear. Antimicrobials may have been given in the other seven cases, but it was unclear [Citation15].

Despite potential life-threatening toxicity with accidental daily dosing of methotrexate prescribed weekly, there is limited information on the clinical course and treatment. Our patient took 20 mg for five days, and consistent with the complete absorption and cellular uptake of methotrexate each day, she developed severe toxicity. There was undetectable serum methotrexate concentrations because methotrexate is rapidly eliminated over 24 h. She was successfully treated with oral folinic acid and then repeated IV doses to replace activated folate. G-CSF and blood product transfusions were given to manage pancytopenia, and antibiotics administered for fevers in the context of neutropenia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Tian H, Cronstein BN. Understanding the mechanisms of action of methotrexate: implications for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2007;65(3):1–6.

- Cairns R, Brown JA, Lynch AM, et al. A decade of Australian methotrexate dosing errors. Med J Aust. 2016;204(10):384–384. doi: 10.5694/mja15.01242.

- Moore TJ, Walsh CS, Cohen MR. Reported medication errors associated with methotrexate. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(13):1380–1384. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/61.13.1380.

- Thompson JA, Love JS, Hendrickson RG. Methotrexate toxicity from unintentional dosing errors: calls to a poison center and death descriptions. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(6):1246–1248. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2021.06.210120.

- Howard SC, McCormick J, Pui CH, et al. Preventing and managing toxicities of high-dose methotrexate. Oncologist. 2016;21(12):1471–1482. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0164.

- Chan BS, Dawson AH, Buckley NA. What can clinicians learn from therapeutic studies about the treatment of acute oral methotrexate poisoning? Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2017;55(2):88–96. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2016.1271126.

- Smith SW, Nelson LS. Case files of the New York city poison control center: antidotal strategies for the management of methotrexate toxicity. J Med Toxicol. 2008;4(2):132–140. doi: 10.1007/BF03160968.

- Galivan J. Transport and metabolism of methotrexate in normal and resistant cultured rat hepatoma cells. Cancer Res. 1979;39(3):735–743.

- Kremer JM. Toward a better understanding of methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(5):1370–1382. doi: 10.1002/art.20278.

- Bookstaver PB, Norris L, Rudisill C, et al. Multiple toxic effects of low-dose methotrexate in a patient treated for psoriasis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(22):2117–2121. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070676.

- Kalyanpad Y, Kharkar V, Khopkar U, et al. Methotrexate a double edged sword – effect of methotrexate in patients of psoriasis due to medication errors. IJCRR. 2017;9(20):10–13. .

- Moisa A, Fritz P, Benz D, et al. Iatrogenically-related, fatal methotrexate intoxication: a series of four cases. Forensic Sci Int. 2006;156(2–3):154–157. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.12.031.

- Singh A, Handa AC. Medication error- a case report of misadventure with methotrexate. J Nepal Med Assoc. 2018;56(211):711–715. doi: 10.31729/jnma.3538.

- Sweet JM, Holstege CP. Bone marrow failure from medication error: diagnosis by history, not biopsy. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(15):1911–1912. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.15.1911.

- Sinicina I. Fehler bei der verordnung—so kann methotrexat tödlich wirken. [prescribing errors – how methotrexate can kill]. MMW Fortschr Med. 2011;153(40):42–46. [German]. doi: 10.1007/BF03368859.