Abstract

This paper explores how everyday aesthetics shape and are shaped within dementia care settings. The authors draw upon research that explored the significance of clothing and textiles in care home settings, to identify the varied and complex aesthetic experiences of people with dementia. The study was carried out using a series of creative, sensory and embodied research methods working with people with dementia and care home staff. Findings demonstrate that aesthetics are important in care homes at a number of levels. People with dementia discussed personal aesthetic preferences and demonstrated such preferences through embodied practices. Attending to aesthetics facilitated moments of togetherness between people with dementia and care home staff, creating person-centred encounters outside task-orientated conversations. This paper supports the importance of everyday aesthetics within dementia care settings and demonstrates that greater attention should be paid to this, to reconsider and enhance not only the look and feel of care homes and everyday items, including clothing, but also dementia care practice more broadly.

Background

This paper presents research exploring the significance of clothing and textiles to people with dementia living in a care home (Fleetwood-Smith Citation2020; Fleetwood-Smith, Tischler, and Robson Citation2021), to reveal the varied ways in which people with dementia engage with aesthetics. It identifies the potential that attending to everyday aesthetics has in enhancing dementia care settings.

Dementia is an umbrella term used to describe a number of diseases that affect the brain. Over 200 subtypes of dementia have been identified (Stephan and Brayne Citation2010) and prevalent forms of dementia include: Alzheimer’s disease, dementia with lewy bodies and vascular dementia. The condition is characterized by a progressive decline in cognition and, although there are individual variations, common symptoms include memory loss, problems with concentration, difficulty carrying out daily tasks and issues with communication (NHS Citation2020). Current figures estimate that 70% of the UK care home population are people with dementia (Alzheimer’s Society Citation2021).

Despite growing attention to the design of health and social care settings (see e.g. All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing Citation2017; Arts Council England Citation2007; Chaudhury and Cooke Citation2014; Chaudhury et al. Citation2018; Craig Citation2017; Ludden et al. Citation2019) there is limited literature exploring the interrelationship between conceptualisations and manifestations of dementia, the everyday aesthetics of care home settings and the impact of this on those who inhabit these spaces.

This paper first explores how everyday aesthetics and conceptualisations of dementia are connected, before presenting findings that demonstrate how people with dementia engage with aesthetics and the implications that this has in reconsidering and reimagining care home settings.

Aesthetics of the everyday

Research demonstrates that people with dementia express preferences when viewing artworks, identifying that aesthetic responses can be preserved in people with the condition (Halpern et al. Citation2008). Aesthetic appreciation is not limited to fine art, with Saito (Citation2007) arguing that greater attention must be paid to the aesthetics of the everyday. Everyday aesthetics expands contemporary Western discourse, moving beyond the tendency to equate aesthetics with philosophy of art (Saito Citation2019). Attention to everyday aesthetics broadly attends to the things, activities, routines and interactions with people that constitute our daily lives (Saito Citation2019). Saito (Citation2007) claims that a person’s sensory experience of a space, the things within a space and how they are encountered and perceived form a person’s aesthetic experience (e.g. the texture of bed-sheets or the look, feel and weight of cutlery). Hence, aesthetics is considered a sensory experience (Heywood Citation2017). Sensory experience, in the context of dementia, is particularly important as people with the condition are at risk of sensory deprivation and can become increasingly reliant on sensory cues due to difficulties with language and communication as the condition progresses (Cohen-Mansfield et al. Citation2015). Sensory deprivation can occur due to, for instance, limited access to sensory stimuli and changes to sensory acuity and this can negatively impact a person’s quality of life. Hence, Jakob, Collier, and Ivanova (Citation2019) claim that multisensory stimulation should be an essential part of dementia care practice, to support people with dementia to live as well as possible.

Attending to aesthetics in daily life, Saito argues, involves viewing it as a moral, social, political and ethical issue (Saito Citation2017). For example, Taylor (Citation2000) states that ‘poorly designed buildings’ show little care for the people who will inhabit them. In contrast, sensitively designed objects and environments demonstrate care and can enrich peoples’ lives (Saito Citation2007). We recognize that such examples invite critique around, for example, aesthetics, functionality, usability, accessibility and suitability for the end-users. They are also intertwined with notions of taste, which involves complex socio-cultural factors. Hence, we draw upon Saito’s (Citation2017, ch1) work and consider everyday aesthetics in a ‘value-neutral way… because the power of the aesthetic can affect us positively or negatively’. For instance, Saito (Citation2017, ch1) writes, ‘if the humdrum nature of daily life is a dreary drudgery, it does not render it anesthetic; rather, it is still an aesthetic texture of everyday life, though negatively experienced’. When discussing aesthetics, we refer to ‘aesthetic preferences’, ‘aesthetic experiences’ and ‘aesthetic sensibilities’ explored through the lens of everyday aesthetics (Saito Citation2007, Citation2017, Citation2019).

Recent materiality studies connect with Saito’s (Citation2007, Citation2017, Citation2019) work and demonstrate that the built environment, everyday objects and health technologies, ‘make’ and ‘shape’ care practices, thus affecting the quality of life of those using health and social care settings (see e.g. Buse, Martin, and Nettleton Citation2018; Buse and Twigg Citation2018; Cleeve Citation2020; Cleeve, Borell, and Rosenberg Citation2020; Latimer Citation2018; Lee and Bartlett Citation2021). Nettleton et al. (Citation2020, 153) interrogate architectural practice when designing a care home and consider how specific materials are selected to ‘encode quality and values of care’ into the buildings. From the making of care homes to everyday items within them, materiality studies demonstrate the significant role that everyday items have in these spaces. For example, Lee and Bartlett (Citation2021) identify the significance of personal and functional items in people’s lives. Their concept of ‘material citizenship’ demonstrates how object-person relations are important and allow people with dementia to maintain their ‘identity and influence how they are perceived’ (Lee and Bartlett Citation2021, 1482). Further, Lovatt (Citation2018, Citation2021) explores how care home residents create a sense of home when living in a care setting, arguing that non-human actors (e.g. objects and artefacts) are not passive vessels of meaning, but that meaning emerges through ongoing social and material interactions. For instance, residents used items such as photographs to interact with people and develop relationships. Social care settings are therefore shaped by social and material interactions that are processual, dynamic and fluid.

In this paper, aesthetics are explored and considered as relational, and we examine how aesthetics can shape and are shaped within the context of dementia care settings. Relational approaches to dementia care consider how people and things are interconnected (Hatton Citation2021) and identify the importance of sensory, embodied, material encounters (Kontos, Miller, and Kontos Citation2017).

Dementia, selfhood and the care home

Traditional conceptualisations of dementia contribute to, influence, and shape the aesthetics of dementia care settings (including care homes). Historically, the social and clinical care of people with dementia has been characterized by biomedical and deficit models of dementia i.e. losses associated with cognitive impairments, and the management of ‘difficult’ behaviours, through control, containment and pharmacology (Dupuis et al. Citation2012). Alongside this, the decline of cognitive function in people with dementia has led to the prevalent view that the condition leads to a loss of self (identity). These deficit-orientated perspectives contributed to the development of care settings that predominately supported containment and reduction of behaviours symptomatic of the condition. For example, Tsekleves and Keady (Citation2021) note that the focus on the medical and clinical needs of people with dementia has neglected their emotional needs or broader aspects of quality of life. They argue that greater research is needed to explore the interrelationship between the physical environment and, for instance, positive engagement in an activity.

Care homes are complex settings involving communal living and blurred ‘boundaries’ between public and private spaces (e.g. Buse and Twigg Citation2014; Cleeve Citation2020). Health and safety requirements necessitate the use of objects such as hand sanitizing gel, latex gloves, stainless-steel medicine trolleys and surfaces (or materials) that are easy-to-clean and hardwearing, engendering an institutional and sterile look, smell and feel (Brawley Citation2006; Campbell Citation2019). Thus, despite care providers frequently citing their provision of ‘homelike’ environments, conservative perspectives and priorities such as efficiency and infection control have shaped what care homes look and feel like. This results in people struggling to navigate places deemed homely but that ‘resemble[d] more of a hospital’ (Craig Citation2017, S2343).

The importance of design in health and social care settings is reflected in the growing number of ‘dementia-friendly design’ guidelines and recommendations (e.g. Greasley-Adams et al. Citation2012; Halsall and MacDonald Citation2015; Timin and Rysenbry Citation2010). Dementia-friendly environments are broadly defined as settings that consider the organizational, social and physical places that impact upon the person with dementia in order to support meaningful engagement in everyday life (Davis et al. Citation2009). Davis et al. (Citation2009) recommend that care homes should enable spontaneous meaningful engagement using varying everyday objects and materials within the setting, for example, vases with flowers for residents to arrange. Similarly, Feddersen (Citation2014), examines the importance of sensory design for people with dementia. For instance, they note that, ‘for a room to truly evoke a particular feeling, requires the orchestration of a whole collection of specific sensory impressions, for example the pleasant smell of flowers, soothing music in the background or a nice place to sit and relax’ (Feddersen Citation2014, 20). These recommendations connect with the ways in which Craig (Citation2017) posits that the careful design of social care settings can be an ‘enabler’ due to the social and material interactions it can facilitate.

The built environment and items within those settings can also act as a ‘barrier’ and negatively affect people. For example, Fleetwood-Smith (Citation2020) found that wearing the ‘wrong’ items of clothing negatively affected individuals whereby they may undress at inappropriate moments such as mealtimes, want to change their clothing, decline certain items, disguise items or refuse to leave their bedrooms. The extent to which aesthetics are perceived and experienced as positive or negative (Saito Citation2017) is nuanced, yet it is important to consider how loss-oriented perspectives impact the design and use of clothing, objects and activities in the care home setting. For instance, clothing designed for people with cognitive impairments (including dementia) has been found to prioritize cost-effectiveness, functionality and efficiency over aesthetics (Iltanen and Topo Citation2007a, Citation2007b; Iltanen-Tähkävuori, Wikberg, and Topo Citation2012). Moreover, Jakob and Collier (Citation2017) state that some multisensory environments designed for people with dementia appear juvenile, thus compromising individual dignity and perpetuating stigma associated with the condition. Similarly, products designed for people with dementia can appear juvenile in form, through the use of primary colours, imagery associated with childhood and the use of materials that resemble and feel like those used to make toys. Thus, the ways in which loss-orientated perspectives permeate the form and appearance of items are important, as these shape how items are used and engaged with. Additionally, Niedderer et al. (Citation2017) note that such perspectives also inform the types of activities offered to people with dementia. For example, activities are often designed to occupy people with dementia, giving people ‘something to do’, rather than supporting meaningful engagement, e.g. an activity of their own choosing. Deficit-orientated perspectives have also been found to drive the development of certain products, as Smith and Mountain (Citation2012) claim, recent technologies typically address issues of safety, security and monitoring rather than facilitating enjoyable engagement.

Over the past thirty years the biomedical model of dementia has been challenged and many oppose the notion that the self deteriorates in those with dementia. These advances develop understandings of selfhood and inform dementia care practice (e.g. Kitwood Citation1997; Kelly Citation2010; Kontos, Miller, and Kontos Citation2017; Sabat Citation2001, Citation2005). Instrumental to the authors’ current project has been increased attention to the role of the body in the construction and manifestation of the self, i.e. embodied selfhood. The notion of embodied selfhood challenges views of identity to understand that a person is unique, and that their wishes and desires are experienced and communicated through the body (Kontos Citation2015; Kontos and Martin Citation2013; Kontos, Miller, and Kontos Citation2017). This is significant as it demonstrates the need to attend to the embodied experiences of people with dementia, for instance, exploring embodied actions (e.g. gestures, movements) as expressive, rather than behaviours to be managed.

Approaching dementia through an embodied relational lens (Hatton Citation2021; Kontos, Miller, and Kontos Citation2017) connects with salutogenic approaches to designing health and social care settings for people with dementia (Fleming, Zeisel, and Bennett Citation2020). To summarize, a salutogenic approach to design centres on three elements: comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness (Golembiewski Citation2010). Comprehensibility refers to a person’s ability to read the environment, meaning that settings should enable individuals to make sense of their lives and circumstances; manageability to control and agency through a built environment that enables people to manage their everyday physical needs; and meaningfulness refers to enriching environments that support desires, personal connections and emotional needs.

Innovations in design for people with dementia have demonstrated the opportunities that approaches centred on promoting positive, meaningful engagement offer people with dementia. For example, the LAUGH project (see e.g. Treadaway, Fennell, and Taylor Citation2020; Treadaway et al. Citation2018) involves working with people with dementia, their loved ones and care workers to develop products that promote joyful connections. Their sensory product HUG™, originally designed for a person living with late-stage dementia, is a soft, wearable object that contains embedded electronics to mimic the feel of being hugged. The product has received widespread acclaim for the comfort it brings to some people with dementia. Similarly, a collaboration between Relish, the University of Central Lancashire, and the Alzheimer’s Society developed The Fidget Widget® (UCLan Citation2019), a series of carefully designed wooden objects created to provide sensory stimulation and enhance wellbeing. The notion that these items have been designed to promote joy, sensory engagement and meaningful connections is of interest when reimagining the aesthetics of the care home, its purpose and design.

Despite growing attention to the design of health and social care environments, there is limited research that explores everyday aesthetics within dementia care settings and the impact of this on care home residents. Drawing upon dementia studies, dementia care research and innovative design practices (see e.g. Buse and Twigg Citation2013, Citation2014, Citation2018; Jakob, Collier, and Ivanova Citation2019; Jakob et al. Citation2017; Kontos Citation2015; Kontos et al. Citation2017; Lee and Bartlett Citation2021; Niedderer et al. Citation2017; Smith and Mountain Citation2012; Treadaway et al. Citation2020, Citation2018; Tsekleves and Keady Citation2021), the current study examined everyday clothing and textile practices to identify holistic approaches to dementia care. Findings revealed how people with dementia engage with everyday aesthetics.

The current study was underpinned by the concept of embodied selfhood and a focus on relational approaches to care, thus emphasizing the role of people with dementia as active agents. This led to the careful design of research methods that supported people with dementia to participate in the study as fully as possible.

Methods

Research was carried out using a number of creative, sensory and embodied research methods over three interlinked cycles of study. The approach was underpinned by Pink’s (Citation2015) Sensory Ethnography (SE). SE draws upon traditional ethnographic techniques: it involves viewing the body as a source of knowledge and is informed by an understanding of the interconnected senses (Howes Citation2005), meaning that, for instance, visual observations are relevant due to the connection with the other senses. SE therefore incorporates innovative methods that go beyond listening and watching, to employ the use of multiple media (Pink Citation2015).

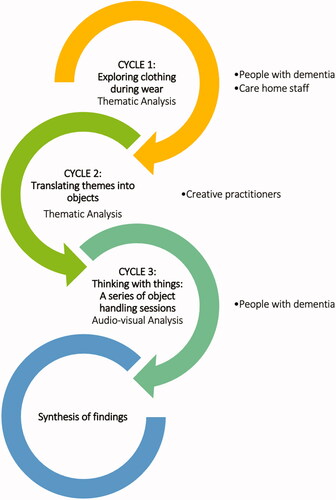

The following interlinked cycles of study were carried out. See Interlinked Cycles of Study for an overview.

Figure 1. Interlinked cycles of study (Fleetwood-Smith et al. Citation2021).

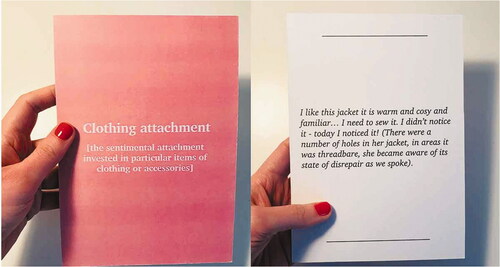

Figure 2. Example of a thematic card (Fleetwood-Smith et al. Citation2021).

CYCLE 1: Exploring clothing during wear using multisensory research encounters

Multiple concurrent semi-structured observations and interviews i.e. multisensory research encounters, were carried out to explore clothing during wear. The sensorial element to the encounters involved participants (both care home staff and people with dementia) engaging with items in their immediate vicinity e.g. their clothing and accessories (e.g. Buse and Twigg Citation2014; Iltanen and Topo Citation2015). The cycles of study aimed to explore how clothing could be considered in the holistic care of people with dementia. Due to the focus on everyday clothing practices, participants were invited to explore their clothing and accessories at the time of the interview, although in some cases participants chose to bring specific items such as perfume or jewellery to an encounter. Up to six encounters were carried out with each participant and the repetition elicited rich insights into everyday clothing practices.

CYCLE 2: Translating themes into objects, images and materials

The second cycle of study built upon findings from CYCLE 1. The themes are broadly summarized as follows: (1) the appearance and feel of clothing; (2) embodied, habitual clothing practices; (3) everyday creativity and clothing (clothing as a tool for expression); (4) clothing and possession attachment and (5) clothing as a tool with which to explore the unacknowledged. CYCLE 2 involved working with creative practitioners who had expertise in working with people with dementia, to examine how CYCLE 1’s thematic findings could be re-interpreted into a series of objects, images and materials. Creative practitioners’ expertise included: visual arts, ceramics, theatre design and music. Their involvement is treated as confidential as they were research participants in the study. Each practitioner took part in one research encounter in which CYCLE 1’s findings were presented as thematic cards. The thematic cards were used as elicitation tools to explore potential design ideas. The cards were inspired by the use of cultural probes (or design probes) within design research (Wallace et al. Citation2013; Woodward Citation2020).

This cycle was informed by the work of Chamberlain and Craig (Citation2013, Citation2017), who used artefacts to work with older people to generate knowledge. Their work underpinned this project’s approach to working with creative practitioners to select and design objects, images and materials. CYCLE 2 resulted in the creation of three themes i.e. ‘playful’, ‘narrative’ and ‘dramatic’, that informed the design of objects, images and materials subsequently used in CYCLE 3. The process of designing and selecting the objects, images and materials was inspired by detailed recommendations from creative practitioners, who suggested the use of certain fabrics (e.g. wools, silks, velvets), specific colours (e.g. a bright, bold contrasting palette) and particular objects (e.g. accessories or clothing that showed signs of wear). The process was also informed by creative practitioners’ different approaches to engaging with people with dementia, which ranged from creating personalized boxes of materials and promoting individual engagement to creating an exhibition-like display to encourage group interactions and responses.

CYCLE 3: Thinking with things: a series of object-handling sessions

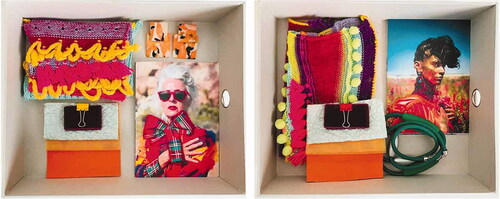

This cycle of study – a series of object-handling sessions – built upon the themes identified in CYCLE 1 and findings from 2. The method involved repurposing the use of object-handling sessions, typically a psychosocial intervention for people with dementia (see e.g. Camic et al. Citation2019; Thomson and Chatterjee Citation2016), as a research method. Participants with dementia were invited to take part in small groups of two or three participants in each of the three object-handling sessions. Each session involved the use of different objects, images and materials, which were presented to participants according to each theme. For example, the ‘playful’ session involved individual boxes to support personal engagement with items, whilst the ‘narrative’ sessions involved a curated table of items to promote shared interactions and discussions. Sessions were videorecorded to enable exploration of both verbal and embodied expressions (e.g. gestures, movements). shows an example box of objects, materials and images used in a ‘playful’ session.

Figure 3. Two of the “playful” session boxes (Fleetwood-Smith et al. Citation2021).

The use of videorecording when working with people with dementia is sensitive (Campbell and Ward Citation2017) and the process was carefully navigated. Sessions took place in a private room to ensure confidentiality. Each session was facilitated by the lead author, who is experienced at leading creative workshops with people with dementia and was supported by a member of care home staff. Consent was revisited prior to and during each session to ensure that participants were happy to take part and to be videorecorded for the purpose of the research.

Participants

This research involved working with 6 members of care home staff, 6 creative practitioners and 11 people in early-to-moderate stages of dementia. The thematic findings presented in this paper refer specifically to the data collected with people with dementia. Participants provided demographic information for the purpose of analysis. Participants with dementia identified as female, ages ranged from 79 to 90 years old. Participants identified as White British, Egyptian, Turkish and White American. Where reference to participants is made, codes have been used to ensure confidentiality. Note that the use of codes, instead of pseudonyms, was carefully considered in an attempt to keep participants’ voices and experiences their own without adding a potential layer of meaning using certain pseudonyms (see e.g. Lahman et al. Citation2015).

Analysis

Analysis took place during each cycle of study. Each analytic process varied according to each cycle of study. CYCLE 1 involved an inductive, iterative six-phase reflexive thematic analysis process (see e.g. Braun and Clarke Citation2019; Braun et al. Citation2018). The approach moved beyond examining the semantic content of the data and sought to identify and examine underlying ideas, assumptions and conceptualisations. Analysis during CYCLE 2 involved attending to explicit meanings within the data to identify particular strategies or techniques used by creative practitioners to select specific materials, images and objects for use in CYCLE 3. An adapted version of Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) thematic stages of analysis was used for this process. CYCLE 3 involved an interpretative audio-visual analysis. The approach drew upon Pink’s (Citation2011) approach to videorecordings in ethnographic research, Kristensen’s (Citation2018) embodied video analysis and Braun et al.’s (2019) reflexive thematic analysis process. Six iterative phases of analysis were carried out and phases involved watching and re-watching the video footage with and without audio (in 30–60 s intervals), analysing written notes and exploring the data (e.g. watching the complete footage).

Data from each cycle of study was synthesized, following an altered reflexive thematic analysis process (see e.g. Braun and Clarke Citation2019; Braun et al. Citation2018). The themes presented have been extracted from synthesized data.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for this research was granted by an NHS Research Ethics Committee reference 18/LO/1707. Each cycle of study had an associated recruitment phase. Care home staff were recruited using adverts in the care home, presentations and drop-in information sessions hosted at the study site. Creative practitioners were recruited via the study team’s arts and health practitioner networks. The research team relied upon the expertise of care home managers to identify potential participants with early-to-moderate dementia. The lead author was introduced to potential participants by a member of staff and then worked closely with each individual using written and visual information sheets designed for those with dementia (DEEP Citation2013). Consent was revisited after inclusion in the research. For example, the lead researcher would explain the research, what it involved and ask the participant whether they were willing to take part at the outset of each encounter. Where a potential participant was assessed as not having capacity, the researcher worked with a personal consultee (i.e. a spouse, relative or friend), or where an appropriate person was not identified, a nominated consultee (e.g. member of care staff). Consultees were given an information sheet and were asked to advise what the potential participant’s wishes and feelings would be about taking part in the research. In these cases, a short accessible information leaflet was used, designed for with people with dementia, who were included if they agreed to take part and written consultee assent was obtained.

Findings

The following themes ‘Negotiating the ‘aesthetic fit in the care home,’ ‘Taste: The look and feel’ and ‘Designing with textiles’ demonstrate the varied ways in which individuals engaged with aesthetics in the care home. These themes were extracted from the synthesized data and are a result of the three cycles of study. Anonymized participant verbatim and researcher notes are used to illustrate the findings.

Negotiating ‘aesthetic fit’ in the care home

Firstly, people with dementia negotiated the ‘aesthetic fit’ of ‘things’ within the care home. This finding draws upon Woodward’s (Citation2007) notion of ‘aesthetic fit’ i.e. the process women undergo when selecting what to wear and the extent to which it fits with their sense of self. Participants engaged with a similar process, negotiating the extent to which items did or did not ‘belong’ in the care home. For example, P5 (PWD) conceptually situated herself alongside others in the care home through her appearance:

I think that my clothes are on par with everyone else that is in the same position as me … well here and nearby here… not everybody has big earrings and things like that, so you have to counter that in. P5 (PWD)

The researcher was wearing large resin hoop earrings that the participant had talked about earlier in the research encounter. She seemed to insinuate that she did not need to think about wearing such items of jewellery, as other residents did not. [researcher notes]

Much like P5 (PWD), P3 (PWD) distinguished the care home from other places when she commented on the shoes that the researcher was wearing:

P3 (PWD): ‘And the shoes, beautiful – very nice and they are wasted here’ she said, as she pointed to the researcher’s bronze boots.

Researcher: ‘Wasted here?’

P3 (PWD): ‘Yes, you should keep them for some smart place, darling.

The examples suggest something of an unspoken ‘uniform’ within the care home. This practice indicates that clothing within the care home became characteristic of the standardized institutional setting and was identified according to whether or not it fitted with the aesthetics of the care home.

Taste: the look and feel

During CYCLE 3’s object-handling sessions, participants with dementia expressed personal aesthetic preferences informed by taste and individual experiences in response to the materials, objects and images used, referring to both what the items looked like and how they felt. The textile samples used in the ‘Playful’ sessions were polarizing: many participants did not like them. For example, P23 (PWD), when handling and talking about one of the samples said, ‘There’s too much going on’. Similarly, P19 (PWD) said that some of the samples were ‘too busy’ with ‘too many colours’. Moreover, when comparing a single-coloured sample with a multicoloured one, P19 (PWD) preferred the former and said, ‘less is more’. shows the multicoloured textile samples used in the sessions.

Participants expressed preferences for some of the textile samples and talked about whether they would like to wear or use certain items. For instance, when given a tactile postcard on which there was a pair of knitted woollen gloves, P20 (PWD) said,

‘Put it this way…I would only wear gloves like that for throwing snowballs! It’s not dressy, it’s very, very casual – very wide fingers as opposed to a dressy one which is always shaped.’ As she was talking, she traced the shape of her fingers as though demonstrating a slim tapered glove.

Furthermore, when P21 (PWD) and P22 (PWD) explored a light yellow, hand-knitted mohair jumper in a ‘narrative’ session, they talked about who may wear it:

P22 (PWD): ‘Oh, that’s lovely! Oh, gorgeous, yes.’ She held the jumper up by the shoulders and then laid it across on her knee, stroking the soft mohair knit.

P21 (PWD) watched P22 (PWD) explore the jumper and said, ‘Lightweight and adorable and I haven’t even touched it yet!’ P22 (PWD) then passed the jumper to P21 (PWD) for her to feel it.

P21 (PWD), laying the jumper on her knee and stroking it, said, ‘It’s lightweight, it feels very pleasant – very much more like baby clothes – I think that you may have noticed that I am not a baby!’

Researcher: ‘Yes… What do you think about the colour?’

P21 (PWD): ‘Not my favourite.’ She held the jumper up by the shoulders for P22 (PWD) to look at it, as though inviting her to comment on the colour as well.

P22 (PWD): ‘Yes, I think it is lovely and certainly I would wear it myself if it fitted.’

The responses from P21 (PWD) and P22 (PWD) demonstrate that participants may like a particular item without wanting to wear it themselves e.g. P21 (PWD) thought that the jumper was suitable for a baby, whilst P22 (PWD) was more concerned that it would not fit her. The associations between items, who might wear them and how was demonstrated by P22 (PWD) when she showed the group how she would wear a scarf:

She folded the square scarf on the diagonal, creating a triangle. She then held the two ends located on the longest side of the triangle, and twisted, wrapping the scarf on itself, leaning forward in her chair as she placed the scarf around the back of her neck. She loosely tied the scarf at her neck and gently tucked the ends of the scarf into her cardigan. ‘Like that’, she said, in response to the researcher’s earlier question about how one could wear the scarf. She then sat back in the chair and patted the scarf in place.

This engagement with the scarf was embodied: the participant’s hands knew how to fold, twist and tie the scarf in place. She did not talk through the process. This small incident demonstrates how aesthetic preferences are performed through the body.

Designing with textiles

This finding refers to how participants’ preferences regarding the look and feel of textiles influenced how they engaged with and designed with certain fabrics. During the ‘dramatic’ object-handling sessions, participants were presented with a range of fabrics to explore, select and use to create designs on a mannequin (dressmaker’s stand) with the researcher. This elicited specific responses regarding fabrics. For example, P20 (PWD) and P19 (PWD) discounted using a certain fabric due to its weight:

P20 (PWD) leant over looking at P19 (PWD)’s fabrics and picked up a green jacquard fabric:Footnote1 ‘Now, I don’t think this is a dress material – this is more furnishing – I would not advise that for wearing…’

P19 (PWD): ‘No, you’re correct…quite right.’

P20 (PWD): ‘It is for furnishing…’

Researcher: ‘How can you tell?’

P20 (PWD): ‘It is too heavy’, she said as she held on to the fabric. She turned to P19 (PWD), letting her feel the fabric.

P19 (PWD): ‘Yes, I agree’.

P20 (PWD): ‘And it’s heavy, it’s a heavy pattern’. She patted the fabric firmly and placed it on the table.

In a further session, P20 (PWD) explored how a knitted textile sample could be used:

P20 (PWD) held the knitted textile sample and turned it over, talking as she did so: ‘Something like that there…’ She seemed to be exploring what the piece could be used for … ‘What could we use it for?’ … She carefully analysed the textile sample, exploring the weight of it, balancing it across the palms of her hands. She ran her hands over the surface, examining the feel and texture of the knit… she then invited everyone to engage with the sample, holding the item up. ‘You see?’ … looking at the sample and talking quietly to herself… ‘It isn’t a pocket’. P20 (PWD)

In a different session, P22 (PWD) had a clear idea for the design she wanted to create and ensured that the researcher and care home staff produced what she envisaged:

P22 (PWD): ‘Have it as a pleated skirt’. She held the fabric up, assessing how much fabric there was… ‘Because there is quite a lot [of] it’.

She leant forward in her chair, reaching the waist of the mannequin, and holding the fabric in place. The researcher and supporting member of care home staff proceeded to pin the fabric in place, creating pleats.

Researcher: ‘What does that look like?’

P22 (PWD) pulled a face, as though she was unsure as to what to say.

P22 (PWD): ‘Well, it looks as if you haven’t finished it, I’m afraid’.

The researcher altered the drape of the fabric on the mannequin. P22 (PWD) watched closely and, as the researcher moved the fabric, said, ‘Yeah, that’s it!’

When selecting fabrics, participants considered the suitability of the material, the amount of fabric available and to what extent their designs looked and felt ‘right,’ thus demonstrating aesthetic sensibilities. These encounters were powerful in enabling staff and residents to work together, engaging in conversations around aesthetics, taste and style. Such moments disrupted the power imbalance of the traditional caring relationship i.e. the position of the resident as a person to be ‘cared-for’ and the member of staff as the ‘carer,’ permitting a sense of togetherness in which individuals were together outside the ‘realm’ of the care home. These encounters enabled individuals to learn about one another through sharing ideas and working with the materials.

Discussion

When discussing findings, the authors embrace the subjective nature of this project and do not seek to make generalizations. In line with the research methodology, the findings presented are context-specific, illuminating experiences and practices at a specific site, with a specific population.

Participants engaged with aesthetics in different ways. Clothing was categorized according to the aesthetics of the care home, as it was placed and ‘marked’ according to whether or not it ‘belonged’ in the environment. For example, participants suggested that particular items of clothing did not belong in the setting. This relates to Cleeve’s (Citation2020) findings that items are often tangibly ‘marked’ i.e. identified to indicate ownership and invites reconsideration of standardized and task-oriented environments to assess how a care home may or may not promote certain aesthetics.

Discussions around aesthetics enabled care home staff and residents to be together outside the realm of the care home, facilitating interactions outside of task-orientated conversations. The impact of such encounters may be powerful in enhancing relational approaches to care and concurs with the use of creative approaches to develop the dementia care workforce (Basting Citation2020; Windle et al. Citation2020). For example, the ways in which participants expressed aesthetic preferences through their bodies (e.g. the considered tying of the scarf mentioned above) could inform care practices around supporting individuals’ dress. Creative and caregiving practices alike constitute sensory, affective encounters. Thompson’s (Citation2020, 36) notion of an ‘aesthetics of care’ draws parallels between these practices to promote reimagining health and social care settings.

Participants’ attention to aesthetics connects with existing literature (e.g. Buse and Twigg Citation2016, Citation2018; Halpern et al. Citation2008; Windle et al. Citation2018) and invites reconsideration of the design of clothing and objects for this population. Specific items are typically created to meet cognitive and practical needs, and thus aesthetics are defined by such needs (Iltanen and Topo Citation2007a, Citation2007b; Mahoney, LaRose, and Mahoney Citation2015). This study demonstrates that people with dementia attend to aesthetics, performing preferences through their bodies and discussing aesthetic preferences. As such, findings concur with existing evidence that supports the active participation of people with dementia in design-led research projects (e.g. Craig and Fisher Citation2020; Jakob, Manchester, and Treadaway Citation2017; Ludden et al. Citation2019; Treadaway et al. Citation2020; Tsekleves and Keady Citation2021).

Attending to embodied, sensory experiences has vast implications when reimagining everyday items within the care home, and thus the potential that sensory design (Heywood Citation2017; Lupton and Lipps Citation2018) has when renegotiating dementia care settings and dementia care practice. For example, artefacts that promote sensory experiences can be stimulating and engaging, enabling different forms of personal, meaningful engagement (Jakob, Collier, and Ivanova Citation2019; Treadaway et al. Citation2018; Tsekleves and Keady Citation2021). Yet it is not only the design of an item that is important, as researchers highlight (e.g. Jakob, Manchester, and Treadaway Citation2017; Tsekleves and Keady 2021): collaboration with stakeholders is essential to address potential concerns surrounding aspects such as the purpose, design and use of new products.

Conclusion

Attention to the impact of everyday aesthetics is largely neglected within dementia care. This paper expands knowledge through identifying and demonstrating how people with dementia engage with everyday aesthetics in a care home. Greater attention should be paid to aesthetics within care environments to improve the design and use of everyday items such as clothing, but also the provision of activities, opportunities for engagement and relational approaches to care. This reflects Tsekleves and Keady’s (Citation2021) call for the design of dementia care settings to re-centre from safety issues to emphasizing comfort and connects with salutogenic approaches to design (Fleming, Zeisel, and Bennett Citation2020). As well as implications for settings and items designed for care home residents, findings relate to broader conceptualisations of dementia e.g. loss of selfhood. Engagement with everyday aesthetics positions people with dementia as embodied beings with agency, and this is essential when reimagining dementia care (e.g. Dowlen et al. Citation2021; Kontos et al. Citation2017; Zeilig et al. Citation2019).

Despite the limitations of this study (i.e. that it was carried out at one site and all participants with dementia were female), the contributions this work makes are valuable, as they illuminate the importance of everyday aesthetics within a dementia care setting and identify its potential in dementia care practice. Future studies should involve diverse communities and work with people in a range of dementia care environments so that findings may enhance the lives of those with the condition and be useful to a wide range of staff.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all those who participated in and supported this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rebecka Fleetwood-Smith

Rebecka Fleetwood-Smith’s background is in fashion textile design and psychology. Broadly, her research focusses on the role of the arts, design, and creativity in promoting health and wellbeing. Twitter: @rfleetwoodsmith

Victoria Tischler

Victoria Tischler is a Chartered Psychologist and Associate Fellow of the British Psychological Society. Her research focusses on creativity, mental health and developing multisensory interventions. Twitter: @victischler

Deirdre Robson

Deirdre Robson is a critical and contextual studies lecturer in higher education. Her research focuses on art, museum studies and the art market.

Notes

1 Jacquard fabric is a patterned double-sided fabric woven on a loom; the pattern is created during the weaving process.

References

- All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing. 2017. The Inquiry Report. Creative Health: The Arts for Health and Wellbeing. Accessed 6 June 2021. https://www.culturehealthandwellbeing.org.uk/appg-inquiry/

- Alzheimer’s Society. 2021. Facts for the Media. Accessed 6 June 2021. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-us/news-and-media/facts-media.

- Arts Council England. 2007. A Prospectus for Arts and Health. Department of Health and Arts Council England. Accessed 11 May 2022. https://www.artshealthresources.org.uk/docs/a-prospectus-for-arts-and-health/

- Basting, A. 2020. Creative Care: A Revolutionary Approach to Dementia and Elder Care. New York: Harper Collins.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (4): 589–597. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806.

- Braun, V., V. Clarke, G. Terry, and N. Hayfield. 2018. “Thematic Analysis.” In Handbook of Research Methods in Health and Social Sciences, edited by P. Liamputtong, 843–860. Singapore: Springer.

- Brawley, E. 2006. Design Innovations for Aging and Alzheimer’s: Creating Caring Environments. New York: Wiley.

- Buse, C., D. Martin, and S. Nettleton. 2018. “Conceptualising ‘Materialities of Care': Making Visible Mundane Material Culture in Health and Social Care Contexts.” Sociology of Health & Illness 40 (2): 243–255. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12663.

- Buse, C., and J. Twigg. 2013. “Dress, Dementia and the Embodiment of Identity.” Dementia (London, England) 12 (3): 326–336. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301213476504.

- Buse, C., and J. Twigg. 2014. “Looking ‘Out of Place’: Analysing the Spatial and Symbolic Meanings of Dementia Care Settings through Dress.” International Journal of Ageing and Later Life 9 (1): 69–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.3384/ijal.1652-8670.20149169.

- Buse, C., and J. Twigg. 2016. “Materialising Memories: Exploring the Stories of People with Dementia through Dress.” Ageing and Society 36 (06): 1115–1135. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X15000185.

- Buse, C., and J. Twigg. 2018. “Dressing Disrupted: Negotiating Care through the Materiality of Dress in the Context of Dementia.” Sociology of Health & Illness 40 (2): 340–352. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12575.

- Camic, P., S. Hulbert, and J. Kimmel. 2019. “Museum Object Handling: A Health-Promoting Community-Based Activity for Dementia Care.” Journal of Health Psychology 24 (6): 787–798. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316685899.

- Campbell, S. 2019. “Atmospheres of Dementia Care: Stories Told through the Bodies of Men.” PhD diss., University of Manchester.

- Campbell, S., and R. Ward. 2017. “Videography in Care-Based Hairdressing in Dementia Care: Practices and Processes.” In Social Research Methods in Dementia Studies: Inclusion and Innovation, edited by J. Keady, L.C. Hydén, A. Johnson, and C. Swarbrick, 96–119. Oxon: Routledge.

- Chamberlain, P., and C. Craig. 2013. “Engaging Design – Methods for Collective Creativity.” In Human-Computer Interaction, Part I, HCII 2013, edited by M. Kuruso LNCS 8004, 22–31. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Chamberlain, P., and C. Craig. 2017. “HOSPITAbLe: Critical Design and the Domestication of healthcare.” In Proceedings of the 3rd Biennial Research Through Design Conference, chaired by C. Speed and I. Lambert, 114–130. Edinburgh: National Museum of Scotland. https://figshare.com/articles/HOSPITAbLe_critical_design_and_the_domestication_of_healthcare/4746952

- Chaudhury, H., and H. Cooke. 2014. “Design Matters in Dementia Care: The Role of the Physical Environment in Dementia Care Settings.” In Excellence in Dementia Care, edited by M. Downs and B. Bowers. 2nd ed. 144–158. UK: Open University Press.

- Chaudhury, H., H. A. Cooke, H. Cowie, and L. Razaghi. 2018. “The Influence of the Physical Environment on Residents with Dementia in Long-Term Care Settings: A Review of the Empirical Literature.” The Gerontologist 58 (5): e325–e337. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw259.

- Cleeve, H. 2020. “Markings: Boundaries and Borders in Dementia Care Units.” Design and Culture 12 (1): 5–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2020.1688053.

- Cleeve, H., L. Borell, and L. Rosenberg. 2020. “(in)Visible Materialities in the Context of Dementia Care.” Sociology of Health & Illness 42 (1): 126–142. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12988.

- Cohen-Mansfield, J., M. Dakheel-Ali, M. S. Marx, K. Thein, and N. G. Regier. 2015. “Which Unmet Needs Contribute to Behavior Problems in Persons with Advanced Dementia?” Psychiatry Research 228 (1): 59–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.03.043.

- Craig, C. 2017. “Imagined Futures: designing Future Environments for the Care of Older People.” The Design Journal 20 (sup1): S2336–S2347. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2017.1352749.

- Craig, C., and H. Fisher. 2020. “Journeying through Dementia: The Story of a 14-Year Design-Led Research Enquiry.” In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Design4Health, edited by K. Christer, C. Craig and P. Chamberlain, 105–117. Sheffield: Lab4Living.

- Davis, S., S. Byers, R. Nay, and S. Koch. 2009. “Guiding Design of Dementia Friendly Environments in Residential Care Settings: Considering the Living Experiences.” Dementia 8 (2): 185–203. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301209103250.

- DEEP. 2013. “Writing Dementia-Friendly Information.” DEEP, November. http://dementiavoices.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/DEEP-Guide-Writing-dementia-friendly-information.pdf.

- Dowlen, R., J. Keady, C. Milligan, C. Swarbrick, N. Ponsillo, L. Geddes, and B. Riley. 2021. “In the Moment with Music: An Exploration of the Embodied and Sensory Experiences of People Living with Dementia during Improvised Music-Making.” Ageing and Society: 1–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X21000210.

- Dupuis, L. S., E. Wiersma, and L. Loiselle. 2012. “Pathologizing Behavior: Meanings of Behaviors in Dementia Care.” Ageing Studies 26 (2): 162–173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2011.12.001.

- Feddersen, E. 2014. “Learning, Remembering and Feeling in Space.” In Lost in Space: Architecture and Dementia, edited by E. Feddersen and I. Lüdtke, 14–24. Basel: Walter de Gruyter GmbH.

- Fleetwood-Smith, R. 2020. “Exploring the Significance of Clothing to People with Dementia Using Sensory Ethnography.” PhD diss., Univeristy of West London.

- Fleetwood-Smith, R., V. Tischler, and D. Robson. 2021. “Using Creative, Sensory and Embodied Research Methods When Working with People with Dementia: A Method Story.” Arts & Health : 1–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2021.1974064.

- Fleming, R., J. Zeisel, and K. Bennett. 2020. World Alzheimer Report 2020: Design Dignity Dementia: Dementia-Related Design and the Built Environment Volume 1. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International.

- Golembiewski, J. 2010. “Start Making Sense: Applying a Salutogenic Model to Architectural Design for Psychiatric Care.” Facilities 28 (3/4): 100–117. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/02632771011023096.

- Greasley-Adams, C., A. Bowes, A. Dawson, and L. McCabe. 2012. Good Practice in the Design of Homes and Living Spaces for People with Dementia and Sight Loss. Accessed 12 May 2022. https://www.artsandhealth.ie/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/good_practice_in_the_design_of_homes_and_living_spaces_for_people_living_with_dementia_and_sight_loss_final.pdf

- Halpern, Andrea R., Jenny Ly, Seth Elkin-Frankston, and Margaret G. O'Connor. 2008. “I Know What I Like": Stability of Aesthetic Preference in Alzheimer's Patients.” Brain and Cognition 66 (1): 65–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2007.05.008.

- Halsall, B., and R. MacDonald. 2015. Volume 1: Design for dementia: A Guide with Helpful Guidance in the Design of Exterior and Interior Environments. Liverpool: The Halsall Lloyd Partnership. http://www.hlpdesign.com/images/case_studies/Vol1.pdf

- Hatton, N. 2021. Performance and Dementia. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51077-0.

- Heywood, I. 2017. Sensory Arts and Design. London: Bloomsbury Academic

- Howes, D. 2005. Empire of the Senses: The Sensual Cultural Reader. Oxford: Berg.

- Iltanen, S., and P. Topo. 2007a. “Ethical Implications of Design Practices. The Case of Industrially Manufactured Patient Clothing in Finland.” In Nordic Design Research Conference Proceedings. Stockholm: Konstfack.

- Iltanen, S., and P. Topo. 2007b. “Potilasvaatteet, Pitkäaikaishoidossa Olevan Ihmisen Toimijuus ja Etiikka – Vaatesuunnittelijoiden Näkemyksiä. [Patient Clothing, Agency of the Persons in Long-Term Care and Ethics – Designers’ Views. Abstract in English].” Gerontologia 21 (3): 231–245.

- Iltanen, S., and P. Topo. 2015. “Object Elicitation in Interviews about Clothing, Design, Ageing and Dementia.” Journal of Design Research 13 (2): 167–184. doi:https://doi.org/10.1504/JDR.2015.069759.

- Iltanen-Tähkävuori, S., M. Wikberg, and P. Topo. 2012. “Design and Dementia: A Case of Garments Designed to Prevent Undressing.” Dementia 11 (1): 49–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301211416614.

- Jakob, A., and L. Collier. 2017. “Sensory Enrichment for People Living with Dementia: increasing the Benefits of Multisensory Environments in Dementia Care through Design.” Design for Health 1 (1): 115–133. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/24735132.2017.1296274.

- Jakob, A., L. Collier, and N. Ivanova, 2019. “Implementing Sensory Design for Care-Home Residents in London.” In Proceedings of the International MinD Conference: Designing with and for People with Dementia, edited by K. Niedderer, G. Ludden, R. Cain, and C. Wölfel, 109–122. Dresden: Technische Universität Dresden.

- Jakob, A., H. Manchester, and C. Treadaway. 2017. “Design for Dementia Care: Making a Difference.” In Design + Power, 7th Nordic Design Research Conference Proceedings. Oslo: Nordes.

- Kelly, F. 2010. “Recognising and Supporting Self in Dementia: A New Way to Facilitate a PersonCentred Approach to Dementia Care.” Ageing and Society 30 (1): 103–124. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X09008708.

- Kitwood, T. 1997. Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Kontos, P. 2015. “Dementia and Embodiment.” In Routledge Handbook of Cultural Gerontology, edited by J. Twigg and W. Martin, 173–181. London: Routledge

- Kontos, P., and W. Martin. 2013. “Embodiment and Dementia: Exploring Critical Narratives of Selfhood, Surveillance, and Dementia Care.” Dementia (London, England) 12 (3): 288–302. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301213479787.

- Kontos, P., L. K. Miller, and A. Kontos. 2017. “Relational Citizenship: supporting Embodied Selfhood and Relationality in Dementia Care.” Sociology of Health & Illness 39 (2): 182–198. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12453.

- Kristensen, L. K. 2018. “Peeling an Onion’: layering as a Methodology to Promote Embodied Perspectives in Video Analysis.” Video Journal of Education and Pedagogy 3 (1): 1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40990-018-0015-1.

- Lahman, M., K. Rodriguez, L. Moses, K. Griffin, B. Mendoza, and W. Yacoub. 2015. “A Rose by Any Other Name is Still a Rose? Problematizing Pseudonyms in Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 21 (5): 445–453. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800415572391.

- Latimer, J. 2018. “Afterword: Materialities, Care, 'Ordinary Affects', Power and Politics.” Sociology of Health & Illness 40 (2): 379–391. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12678.

- Lee, K., and R. Bartlett. 2021. “Material Citizenship: An Ethnographic Study Exploring Object-Person Relations in the Context of People with Dementia in Care Homes.” Sociology of Health & Illness 43 (6): 1471–1485. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13321.

- Lovatt, M. 2018. “Becoming at Home in Residential Care for Older People: A Material Culture Perspective.” Sociology of Health & Illness 40 (2): 366–378. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12568.

- Lovatt, M. 2021. “Relationships and Material Culture in a Residential Home for Older People.” Ageing and Society 41 (12): 2918–2953. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X20000690.

- Ludden, G. D. S., T. J. L. van Rompay, K. Niedderer, and I. Tournier. 2019. “Environmental Design for Dementia Care - Towards More Meaningful Experiences through Design.” Maturitas 128: 10–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.06.011.

- Lupton, E., and D. Lipps. 2018. The Senses: Design beyond Vision. New York: Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum and Princeton Architectural Press

- Mahoney, D. F., S. LaRose, and L. E. Mahoney. 2015. “Family caregivers' perspectives on dementia-related dressing difficulties at home: The preservation of self model.” Dementia (London, England) 14 (4): 494–512. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/147130121350182.

- Nettleton, S., D. Martin, C. Buse, and L. Prior. 2020. “Materializing Architecture for Social Care: Brick Walls and Compromises in Design for Later Life.” The British Journal of Sociology 71 (1): 153–167. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12722.

- NHS. 2020. Dementia Guide: Symptoms of Dementia. NHS. Accessed 3 August 2020. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/dementia/about/.

- Niedderer, K., I. Tournier, D. Colesten-Shields, M. Craven, J. Gosling, J. A. Garde, M. Bosse, B. Salter, and I. Griffioen. 2017. “Designing with and for People with Dementia: Developing a Mindful Interdisciplinary Co-Design Methodology.” In Proceedings of the IASDR (International Associations of Societies of Design Research) International Conference 2017. University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati. doi:https://doi.org/10.7945/C2G67F.

- Pink, S. 2011. “Multimodality, Multisensoriality and Ethnographic Knowing: Social Semiotics and the Phenomenology of Perception.” Qualitative Research 11 (3): 261–276. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111399835.

- Pink, S. 2015. Doing Sensory Ethnography. 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications.

- Sabat, S. 2001. The Experience of Alzheimer’s Disease: Life through a Tangled Veil. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Sabat, S. 2005. “Capacity for Decision-Making in Alzheimer’s Disease: Selfhood, Positioning and Semiotic People.” Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 39 (11-12): 1030–1035. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01722.x.

- Saito, Y. 2007. Everday Aesthetics. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Saito, Y. 2017. Aesthetics of the Familiar: Everyday Life and World-Making. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199672103.001.0001.

- Saito, Y. 2019. “Aesthetics of the Everyday.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Accessed 12 May 2022. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aesthetics-of-everyday/.

- Smith, S. K., and G. A. Mountain. 2012. “New Forms of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) and the Potential to Facilitate Social and Leisure Activity for People Living with Dementia.” International Journal of Computers in Healthcare 1 (4): 332–345. doi:https://doi.org/10.1504/IJCIH.2012.051810.

- Stephan, B., and C. Brayne. 2010. “Prevalence and Projections of Dementia.” In Excellence in Dementia Care: Research into Practice, edited by M. Downs and B. Bowers, 9–35. Berkshire: Open University Press.

- Taylor, N. 2000. “Ethical Arguments about the Aesthetics of Architecture.” In Ethics and the Built Environment, edited by W. Fox, 193–206. London: Routledge.

- Thompson, J. 2020. “Towards an Aesthetics of Care.” In Performing Care: New Perspectives on Socially Engaged Performance, edited by A. Fisher and J. Thompson, 36–48. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Thomson, M. J. L., and H. J. Chatterjee. 2016. “Well-Being with Objects: Evaluating a Museum Object-Handling Intervention for Older Adults in Health Care Settings.” Journal of Applied Gerontology : The Official Journal of the Southern Gerontological Society 35 (3): 349–362. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464814558267.

- Timin, G., and N. Rysenbry. 2010. Design for Dementia. Accessed 12 May 2022. https://rca-media2.rca.ac.uk/documents/120.Design_For_Dementia.pdf

- Treadaway, C., J. Fennell, and A. Taylor. 2020. “Compassionate Design: A Methodology for Advanced Dementia.” In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Design4Health, edited by K. Christer, C. Craig and P. Chamberlain, 667–673. Amsterdam: Lab4Living.

- Treadaway, C., J. Fennell, A. Taylor, and G. Kenning. 2018. “Designing for Playfulness through Compassion: Design for Advanced Dementia.” In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Design4Health, edited by K. Christer, C. Craig, and D. Wolstenholme, 275–285. Sheffield: Lab4Living.

- Tsekleves, E, and J. Keady. 2021. Design for People Living with Dementia. Oxon: Routledge

- UCLan. 2019. Innovative New Toolkit Helps Those Living with Dementia. Accessed 11 May 2022. https://www.uclan.ac.uk/news/innovative-new-toolkit-helps-those-living-with-dementia

- Wallace, J., J. McCarthy, P. C. Wright, and P. Olivier. 2013. “Making Design Probes Work.” In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, chaired by W. Mackay, S. Brewster, and S. Bødker, 3441–3450. New York: Association for Computing Machinery. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/2470654.2466473.

- Windle, G., K. Algar-Skaife, M. Caulfield, L. Pickering-Jones, J. Killick, H. Zeilig, and V. Tischler. 2020. “Enhancing Communication between Dementia Care Staff and Their Residents: An Arts-Inspired Intervention.” Aging & Mental Health 24 (8): 1306–1315. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1590310.

- Windle, G., K. Joling, T. Howson-Griffiths, B. Woods, H. C. Jones, P. van de Ven, A. Newman, and C. Parkinson. 2018. “The Impact of a Visual Arts Programme on Quality of Life, Communication and Well-Being of People Living with Dementia: A Mixed-Methods Longitudinal Investigation.” International Psychogeriatrics 30 (3): 409–415. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610217002162.

- Woodward, S. 2007. Why Women Wear What They Wear. Oxford: Berg Publishers

- Woodward, S. 2020. Material Methods: Researching and Thinking with Things. London: Sage

- Zeilig, H., V. Tischler, M. van der Byl Williams, J. West, and S. Strohmaier. 2019. “ Co-Creativity, Well-Being and Agency: A Case Study Analysis of a Co-Creative Arts Group for People with Dementia.” Journal of Aging Studies 49: 16–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2019.03.002.