Abstract

This article reports 36 in-depth interviews with patients (n = 20) and family members of palliative care patients (n = 16), during an inpatient stay within one of four contemporary palliative care facilities. Interviews were conducted to understand how patients and families felt the built environment supported their experience of palliative care, and the ways that it did not. Over the past decade, a growing body of literature has sought to understand how architectural design can support wellbeing within palliative care settings. Yet, despite evidence that promotes the prioritization of privacy, homeliness, and nature, the sheer complexity of hospital procurement often results in compromises to the successful implementation of best design practice. Here we argue that a deeper understanding of what these environmental affordances mean to patients being treated for a terminal illness, and to their families, may encourage a necessary re-examination of the ease with which these provisions are compromised relative to considerations of risk, cost, or convenience (in building construction and/or maintenance). Importantly, our findings confirm that privacy, homeliness, and nature do not operate in isolation but in accord to shape experiences of palliative care.

Introduction

The fundamental orientation of palliative care differs from almost all other forms of medical treatment; rather than providing a cure, palliative care aims to help patients ‘live their life as fully and as comfortably as possible’ following the diagnosis of a terminal illness, and to support family members during this time (Palliative Care Australia Citation2022). In Australia, palliative care services cater to a spectrum of patient needs, spanning those who require inpatient care for symptom management, whether temporary or long-term, and caring for those who are at the end of life. In 2003, physicians Mount and Kearney (Citation2003, 657) famously redefined the concept of healing for palliative care, stating that ‘it is possible to die healed’ and that such healing can be facilitated through the provision of ‘a secure environment grounded in a sense of connectedness’. In seeking this connectedness, palliative care focuses on the patient within the wider context of their family; this manifests as a desire to support family members through their experiences of loss while concurrently providing care to the patient (Adams Citation2016; McLaughlan et al. Citation2022; Steele and Davies Citation2015; Wright et al. Citation2010). While it is broadly accepted that the way a healthcare facility is designed can support the delivery and overall experience of palliative care (Gardiner et al. Citation2011; Hajradinovic et al. Citation2018; McLaughlan and Kirby Citation2021; Rowlands and Noble Citation2008; Zadeh et al. Citation2018), architect and theorist Sarah McGann (Citation2016) has drawn attention to the extent to which physical space can all too easily undermine the achievement of palliative care’s distinct ‘philosophy of care’. Taking this philosophy of care as our starting point, this study aimed to understand how patients and families felt that the built environment supported their experience of palliative care, or did not. This article reports 36 in-depth interviews with patients (n = 20) and family members of palliative care patients (n = 16), during an inpatient stay within one of four contemporary palliative care facilities.

The literature on designing for palliative care identifies salient examples of the kinds of compromises to which McGann refers above. Homeliness, for example, is recognized as a crucial contributor to the quality of life of patients and their families during hospitalization (Bradshaw, Playford, and Riazi Citation2012; Brereton et al. Citation2012; Gardiner et al. Citation2011; Hajradinovic et al. Citation2018; Rasmussen and Edvardsson Citation2007; Rowlands and Noble Citation2008; Timmermann et al. Citation2015; Zadeh et al. Citation2018). This quality is often associated with matters of interior design where things like vinyl flooring, the presence of medical equipment, or fluorescent lighting are frequently seen as sources of discomfort; while colour schemes, non-institutional materials and furnishings, and the presence of personal belongings are seen as making a space feel more homely (Collier, Phillips, and Iedema Citation2015; Gardiner et al. Citation2011; Kilgour, Bourbonnais, and McPherson Citation2015; McLaughlan and Richards Citation2023; Timmermann et al. Citation2015; Ulrich et al. Citation2008). Yet, despite the recognized importance of homeliness, multiple factors continue to obstruct the attainment of homelier palliative care environments. The inclusion of less institutional furniture and materials are often thought to be restricted owing to concerns of infection risk. As a nurse observed within a study by Gardiner et al. (Citation2011, 164):

People want a more homely environment but … [with] infection control and all the guidelines and protocol … you can’t get a homely setting in a clinical setting. I mean we used to have a lovely great big settee upstairs but because it wasn’t wipeable, it didn’t meet infection control, we can’t have it.

In the decade since Gardiner’s study, technological advances in antimicrobial coatings for carpets and upholstery materials should have all but alleviated this problem; the fact that it persists is the result of a far more complex set of factors related to the procurement and ongoing management of hospital buildings. Standardized cleaning protocols and the expectation of uniform design standards, within and across hospital sites, means that palliative care units must often conform with the stricter requirements of higher acuity areas, such as cardiology and emergency departments. Further obstacles arise from ingrained procurement processes that, in both the Australian and UK contexts, favour established supply chains that restrict the choices available to architects and designers (McLaughlan and George Citation2022; McLaughlan and Kirby Citation2021). It is within this broader context of hospital design and procurement that we suggest a deeper understanding of what environmental qualities matter most to palliative care patients and their families – and of the reasons why these matter – may help to refocus design decisions away from concerns of risk, cost, or convenience, and back towards concerns of patient and family wellbeing.

Architectural context of the study

The four facilities where the research took place are representative of typical Australian inpatient facilities for palliative care; and were selected for their geographical proximity, given the impact of COVID-19 travel restrictions at the time of data collection. The respective bed sizes of these four facilities were 11, 12, 17 and 25-beds. The four facilities shared commonalities relative to location, building type, room type and access to nature. Two were located on general hospital grounds (one inner-city, one suburban), but occupied buildings separate from the main hospital building. Two were located independently of general hospital sites but co-located with rehabilitation facilities (both in suburban locations). Two facilities were located on the second floor of the building but with views to surrounding landscape or to large street trees (in the case of the inner-city hospital), and both had outdoor gardens at ground level that patients could access. Two were single-story facilities, with direct access from the patient room to the surrounding landscape, and where that landscape occurred within a central courtyard or formed small courtyards between the building edge and site’s (fenced) perimeter boundary. All facilities had a mix of single and double-occupancy patient rooms, but where single rooms were predominant.

All four facilities had a similar aesthetic appearance owing to a confluence of construction dates and recent refurbishment; three of the four were constructed between 1988 and 1991, while the fourth consisted of an amalgamation of a 1964 hospital building with a more contemporary addition. All four facilities had undergone recent cosmetic refurbishment, occurring between 2016 and 2019. Accordingly, in providing reasonable levels of privacy, achieved largely through the provision of single rooms, family room/s and accessible garden space/s, these four facilities are consistent with contemporary recommendations in designing for palliative care (Brereton et al. Citation2012; Hajradinovic et al. Citation2018; Kayser-Jones et al. Citation2003; Miller, Porter, and Barbagallo Citation2022; Rowlands and Noble Citation2008; Zadeh et al. Citation2018). Further, while homeliness remains an important though imprecise design recommendation, and thus difficult to qualify, all four facilities aspired to provide an atmosphere more homely than hospital like. For these reasons, the study provided the opportunity to go beyond a simple understanding of the value of these environmental provisions toward a deeper understanding of the collective impact of these factors in shaping experiences of palliative care.

Method

Interviews followed a two-part format where an initial discussion focussed on understanding the experiences of patients and family members in different inpatient care settings. This began with general questions about the participant’s (or their family member’s) length of stay and any previous experiences of hospitalization, both at the interview site and at other hospitals. Participants were asked to describe what they felt were the most salient features of their room, and how they felt about the hospital environment generally. A series of discussion prompts were used, such as, how the room was occupied on a typical day; do patients spend most of their time in bed, or in a chair by the window; do they go out to the garden on a regular basis? Participants were asked how long visitors stayed and how the room is occupied during visits; where do people sit, and can the room accommodate more than one visitor comfortably? Pandemic related visitor restrictions varied across our data collection, however, all facilities tried to accommodate small family groups wherever it was safe to do so. This had a limited impact on our data collection as experiences of large (or extended) family groups could not be captured by the study, however, most participants were able to speak to us about visitation by small groups of immediate family and close friends. Similarly, where large family rooms were provided at the participating sites, access to these was closed over the duration of our study.

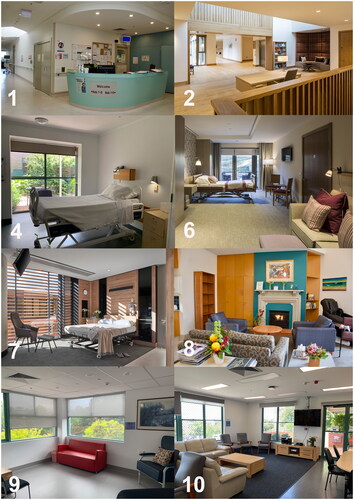

The second part of the interview employed a photo-elicitation method (Bates Citation2019; Harper Citation2002). Participants were shown 12 images depicting different design approaches to palliative care spaces and asked what they thought of each image (). Where further prompts were required, participants were asked if there was anything they liked or didn’t like about that image, and where a participant had no comment to make about an image, the interviewer moved onto the next photograph. Of the 12 images, 3 depicted circulation spaces, 4 depicted patient rooms, and 5 depicted communal family (or lounge) room spaces typically provided on palliative care wards. Seven of the 12 images depicted standard or typical Australian palliative care wards (6 of those from the recruitment sites themselves) while the remaining 5 images were sourced from recently constructed hospice projects within Australia and internationally. This approach recognizes that non-architects are not always able to imagine what is possible within hospital design, or to clearly articulate what kinds of architectural aesthetics or features they might prefer. Photo-elicitation thus provides a visual prompt to stimulate a deeper engagement by presenting participants with alternative scenarios that allow them to reflect on the space they are currently occupying. The 12 images were selected from an initial sample of 100 images sourced from photographs taken for this study and international examples of contemporary palliative care facilities obtained via an internet search. The first author independently narrowed the sample down to 24 images, which were then discussed by both authors with a third colleague until consensus regarding the 12 images was reached, with a view to obtaining a variation of design approaches across the image set.

Figure 1. Eight of the 12 images used in the photo-response interviews shown in the order they were presented to participants. Photographer credits for each image as follows are as follows: authors (images 1,4,8,9,10); ©keith hunter (images 2,6); ©peter clarke (image 7).

Recruitment and data collection

A purposive recruitment strategy was used to identify patients with experience of inpatient palliative care environments, or their family members. Any participant who was not in significant pain and capable of providing consent was able to participate. Initial approaches were made by nominated medical staff (the treating physician, the nurse unit manager, or research staff associated with the palliative care service). An introductory letter was used for this initial approach and, where interest was shown, a contact telephone number was provided to the lead researcher who followed up to schedule an interview. A Participant Information Sheet was provided to participants and any questions were answered before interviews began. Three participants decided not to participate in the interviews due to changes in circumstance (either the health of the patient deteriorated, or they returned home from hospital); another four chose not to for undisclosed reasons. Where participants preferred, interviews with patients and family members were conducted concurrently (7 interviews were conducted in pairs, with the remaining 22 interviews conducted with individuals). The interviews were conducted between 28 April 2021 and 26 May 2022 by the first author via Zoom or in person (relative to participant preference); verbal consent was obtained and captured via the Zoom/audio recording. Ethics was granted by the human research ethics committee of the first author’s university, alongside the respective ethics committees for each hospital site (University of Newcastle, approval no. H-2019-0056).

Data analysis

The interviews were transcribed on a progressive basis by the second author as a way of becoming familiar with the data. The transcripts were added to NVivo and analysed following a ‘qualitative descriptive’ approach (Sandelowski Citation2000). Initial coding was conducted on the corpus by the second author. This consisted of identifying discrete ideas about palliative care environments, typically including comments about the physical environment coupled with specific behaviours or emotions. Both authors regularly conversed as the analysis developed, and once the initial coding was finalized, a series of themes were agreed upon and then further refined through re-readings of the data.

Findings

Twenty patients and 16 family members were interviewed; this included 14 patient and 9 family member interviews conducted individually, alongside 7 interviews conducted in pairs where participants were related. While demographic data was not collected from patients or family members, of the 20 patients interviewed, 10 were male and 10 were female. Of the family members, 13 were female while only 3 were male. In terms of the relationship of those 16 family members, 7 were the daughter of a patient, 6 were the wife, 2 were the husband of a patient, and 1 was the son. Most of the patients interviewed had been hospitalized for symptom management; only two were nearing the end of life. However, six of the nine family members interviewed individually acknowledged that the patient to whom they were related was nearing the end of life. Lengths of stay varied for participants from 2 days to 56 days (8 weeks), with a median of 21 days (3 weeks), and an average of 17. At the time of the interviews, only three patients were in shared (or 2-bed) wards, with the remaining patients in single occupancy rooms, however, another five patients confirmed prior inpatient experiences involving shared accommodation. A further 10 patients or family members confirmed that they/their family member had prior inpatient stays but did not elaborate on whether those were in single or multiple occupancy rooms. While participants were not asked to confirm their age, all patients who participated appeared to be in their mid-50s or older, with the oldest patient volunteering that they were 95 years of age. This was similar for patients that family members spoke to the interviewer about; the exception was one participant whose husband was in his mid-40s and represented the youngest patient discussed within this study. Participants were not asked to confirm their medical diagnoses, however, seven participants volunteered that their/their family member’s diagnosis was cancer.

In line with established design recommendations for palliative care, privacy, homeliness, and nature featured prominently within our interview data even though participants were not specifically questioned about these things. What this data made evident was both the importance of these environmental attributes and the ways that these overlap – or operate in accord – to shape experiences of palliative care. In this section we present each theme in turn to elucidate the complexity and nuance of each.

Privacy is valued by patients and family but also contributes to homeliness

While the single occupancy rooms were appreciated by many patients for the privacy they afforded, interview data highlighted different settings and circumstances in which privacy is desired in palliative care settings. This provides a compelling argument for single occupancy rooms but importantly also for the provision of spaces to support privacy beyond the patient room. Single occupancy rooms enabled patients and their visitors to talk more freely, be out of view of others, and be free from disturbances caused by others. Shared rooms, conversely, gave rise to discomfort. Patients reported feeling obligated to observe a level of politeness in the presence of other patients and their visitors:

I find I don’t like disturbing other people. I don’t like getting up in the night and having to use the bathroom, or if I can’t sleep, having the television on; so, having a room to myself is much better.

Once you get into hospital, you seize up, because you can’t do anything privately. … You know, all of a sudden, you’ve got to go [to the toilet], and you’ve got to… gingerly move the handle to see if your door’s locked, but if [the other patient] forgot to lock it, you catch them at the wrong time.

As well as a consciousness of others, single-occupant rooms were also described as enabling freedom from disturbances caused by others and the care environment generally. ‘Because you’re coming from your home into a hospital environment that is just so loud and noisy, and things are going on 24-7…’.

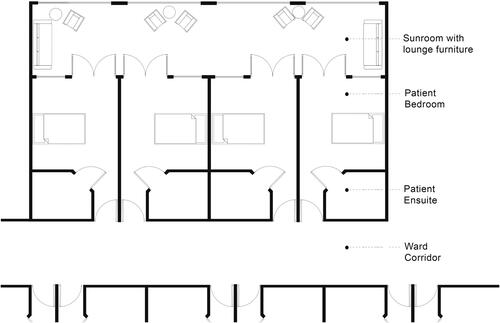

While single-occupancy rooms met several of the privacy needs desired by patients, they were limited in their ability to meet the privacy needs of family members. One relative explained the difficulty of finding a quiet space to update distant family members over the telephone, and even to talk to medical staff: ‘I couldn’t really talk … I literally had to go downstairs and leave the building and that was difficult. … Sometimes the difficult conversations I’ve had have been in a hallway… I’ve just stood in the hallway’. Family members highlighted the personal distress they felt in feeling forced to have conversations with medical staff in front of patients because there was nowhere else suitable to have them. ‘Sometimes I’ve had to have [these conversations] in the room with my mum, which I didn’t want to do. … Then my mum will be like, ‘Oh, am I dying?’ Like, she’s right there, you know?’ When family members need to converse with medical professionals or other relatives, or even take work-related phone calls, outdoor and indoor communal areas or dedicated consultation rooms can enable these kinds of conversations to take place away from the bedside, rather than within the confines of a thoroughfare or in the presence of a loved one. We observed a successful example of such a spatial provision, it was an enclosed veranda space shared between four single-occupancy patient rooms, which patients and family members said was like a living room in feel and function. Participants explained that this space was more comfortable for receiving visitors than the bedroom, was more private than a large communal lounge, and provided a welcome reprieve from spending so much time in the bedroom while still being close enough to not miss the doctor on their rounds ().

Figure 2. A Plan of an enclosed veranda space shared between four single occupancy rooms as a way of providing semi-private spaces beyond the bedroom. Drawing by authors. Plan is not shown to scale; included to delineate spatial proximities only.

Where patients occupied shared rooms, spaces provided beyond the bedroom supported intimate conversations they didn’t feel they could have in the room itself. A husband and wife interviewed together relayed that they’d go down to the garden to talk to each other, or to take phone calls from relatives. ‘We find that we can talk down there because nobody else is down there and we have a bit of privacy’. Another patient commented, ‘sometimes you just can’t talk in front of other people’. Patients and family members suggested that feeling unable to have ‘sensitive conversations’ caused distress. Yet it should be recognized that, in the context of palliative care, everyday conversations may be just as important as loved ones near the end of life as those we might deem ‘sensitive’, that is to say, space should be available for all conversations to be held comfortably. This points to the need for spaces that patients and families can inhabit beyond the patient room, in which they can engage with each other without also engaging with the wider hospital community at the same time. While communal lounges are often provided on palliative care wards for this purpose, the lack of intimacy that can be associated with some of these spaces should be recognized. The response of one family member in relation to Image 10 (see ) was revealing of this; the photograph depicted a large lounge room and the participant said, ‘[with] the u-shaped chair configuration, it looks like there’s about to be some sort of hand-holding Kumbaya sessions, you know, it looks depressing’. Another family member, reflecting on Image 2 (see ), an entrance foyer that featured an upholstered alcove space in the background, said:

There are some great ideas for comfy spaces in those photos …Something a bit more homely so that you can go to a corner with whoever you’re with, you know, a patient, and just sit and feel like you’re in a comfy sort of lounge room.

Homeliness is about appearances and about supporting the rituals of home

Homeliness is about appearances, as much evidence-based design literature suggests, but our interview data confirmed that it is also about creating the conditions that enable rituals of home to be practiced within the hospital. The latter implicates the need for different kinds of spaces, or different ways of approaching the design of hospital environments, to support such rituals. When asked to identify, from the photographs, which elements of an environment participants felt communicated an atmosphere of homeliness, colours, materials and furnishings, alongside more transient elements such as the presence of reading materials in communal areas were all listed. The reverse was also true, patients and family members expressed a clear aversion to qualities perceived as too clinical or hospital-like. When participants reflected on their lived experiences across a range of hospital environments, certain materials – such as the example of vinyl – could be seen to heighten discomfort for family members and patients alike. One family member regarded carpeted rooms as more comfortable than vinyl as they perceived carpet as ‘clinical [and] plastic-y’, and felt less ‘like you’re in an examination room about to undergo a procedure’. This participant went on to explain, that vinyl flooring was also distressing for her mother, who ‘immediately went, ‘Oh my god, I hate this room… [It] stressed her out quite a bit, and she wanted to change rooms’. Similarly, furniture selections, and how these were accommodated within a space, could be seen to make patients families feel more comfortable or, contrarily, feel as if they should move on quickly. In response to Image 6 (see ), one family member commented that the room appeared:

set up for visitors. Some places don’t even have an extra chair … so this makes you feel welcome, the fact that you’ve got two of certain things makes you feel that you’re welcome there, and I think a couch makes you feel a little bit more relaxed… Some places don’t really make you feel welcome, like it’s just for the patient.

What emerges from this data is that homeliness does not operate simply as visual aid to comfort, material choices and spatial layouts have both psychological and physical impacts; these can either enable or prohibit certain behaviours, extending to impacts on the length and quality of time spent with family members and other visitors. As one participant commented in response to Image 9 (see ), ‘I don’t like that red lounge [chair], I mean, who’d be sitting on that? They’re not comfortable anyway. If you wanted to put your head back, you’d be putting your head on the windowsill’. Thus, it wasn’t just about the appearance of the chair, it was the way it would force the body to sit, which the patient felt would be uncomfortable and unhomely. Many participants suggested that uncomfortable furniture and cramped or stuffy rooms made it difficult to visit or be visited. As another family member observed, ‘I’m in the hospital maybe five or six hours a day… I know you don’t want me to just sit on a basic, clinical chair’. Another participant suggested that softer flooring would enable her children to play on the ground during visits, which meant that visitations could last longer. ‘Even just some carpet for [my son] to lie down and just play with Lego or do some drawing… there’s no real space for him to play in or be in’. Multiple stories confirmed that the discomfort caused by furniture, cramped and stuffy rooms resulted in family members cutting short their visits or visiting less frequently than they otherwise would. Yet it wasn’t simply about visitation, materials were seen to have other functional dimensions. For one patient vinyl flooring was a barrier to getting out of bed, for fear of its slipperiness and hardness. ‘[Mum] got scared to get out of bed when it wasn’t carpet because she felt like she was going to slip. She needed to have these special socks’. With carpet, on the contrary, ‘she’s got more confidence… I’ve noticed she’s more open to physio when there’s carpet because she can put her feet down, and she has less anxiety, not thinking she’s going to fall’.

The re-enactment of rituals of home relative to sleeping arrangements came up repeatedly in the interview data. Although the interviews were conducted in facilities with standard-sized hospital beds, two of the images depicted a bariatric hospital bed which many participants assumed was a double bed and this frequently prompted positive responses (refer Image 7, ). ‘What’s good about it is that it’s like being at home, [where] you don’t have a hospital bed… that’s a queen bed [and] that’s excellent’. Other homelike rituals that featured prominently were sharing meals, snacking and watching television, and having visits with pets. Often these comments revolved around not having sufficient space and furniture in patient rooms or communal areas to be able to comfortably accommodate these activities.

Nature supports perceptions of homeliness and extends opportunities for privacy

While views to nature were appreciated by patients, interview data revealed that natural, outdoor spaces also provided valuable opportunities for privacy, further supporting rituals of home, and contributed to perceptions of homeliness. For designers, this confirms the value of views to nature but also the proximity – and thus ease of accessibility – of outdoor spaces. Connectivity, in this sense, means being able to connect with the outside world, either via a view or opportunities for the physical inhabitation of garden spaces. Our interviews revealed experiences of the natural that are therapeutic in different ways. Having windows that frame views onto natural elements are counter to expectations of hospital environments and this can have a positive influence:

Because it’s nature … it’s a natural thing. … I’m not in a cement box, where I can’t look out, or I look out and all I see is a brick wall. There are Mynabirds… doves… lizards… I watch the mushrooms grow. … It’s just something that takes away from being in a cement box… I find myself just looking outside, watching what’s going on outside. It just distracts you from your illness … And I would miss it if it weren’t there.

Having openable windows or doors in patient rooms also afforded connectivity with the exterior; this was seen as particularly important where patients had mobility issues. ‘I’m paralysed from my legs down, so I can’t go outside. But that open door gives me that feeling that I am kind of involved in the outside world’. A lack of connectivity to nature could also be seen to impact the time family members felt they could stay on the ward. One participant told us that the difficulty of accessing outdoors areas meant that ‘I feel I can only stay here for a maximum of five hours before I need to just leave and have some fresh air’.

Where participants were able to leave the ward, opportunities to get outside into the garden spaces were highly valued by patients and family members. As one relative commented, ‘as far as we’re concerned, fresh air is the most important thing. It keeps you going … it motivates you… When we get outside Mum doesn’t even need the oxygen’. Outdoor areas were recognized as useful for accommodating larger group congregations during visits which would not otherwise be possible, but also as more comfortable spaces for visits to take place. ‘When you have visitors, three or four can sit [out] there and have a nicer time and they don’t feel like they’re going to a funeral or to […] hospital just because someone is dying’.

Distance, however, played a significant role in the frequency with which patients and families used hospital gardens, or didn’t. One relative described an experience during a previous stay in different hospital, that involved having to travel ‘down four floors, along the complete length of [the hospital], and then down and out again’. Where accessing gardens was difficult or inconvenient, or where families perceived the garden was too far from medical staff, they were less likely to use these spaces.

What our data also revealed, however, was a willingness to compromise on nature views in respect of other desirable homely affordances. In the example of Image 7 (see ), which featured a larger (bariatric) bed but also overlooked an adjacent building, patient responses were almost unanimous that they would be happy to forgo a nature view for a situation where a larger bed and ample sunshine was provided:

I don’t think [a nature view] matters when you’ve got the things that I notice––that is the double bed scenario, like the ability for someone to come in in the night next to you, if you want… I think even though it doesn’t have a nature view, [the room has] a good feel to it.

Discussion

In our own prior research, based on the observations of palliative care staff and architects experienced in the design of these facilities, we hypothesized that homeliness should be considered as more than an aesthetic quality and should, instead, support families to replicate the routines and rituals of home. Thus, this is about more than simple material choices – or things that ‘look’ homely – it is about providing spaces and furniture with homely affordances. Further, that access to nature supports and enhances palliative care experiences in significant ways that a simple view to nature cannot (McLaughlan and Kirby Citation2021; Wong et al. Citation2023). While our interviews with patients and families confirm these hypotheses, this data further advances an understanding of how privacy, homeliness and nature operate, not in isolation, but in accord to shape experiences of palliative care.

While notions of homeliness are prevalent in health environment literature (Brereton et al. Citation2012; Rasmussen and Edvardsson Citation2007; Rowlands and Noble Citation2008; Timmermann et al. Citation2015; Zadeh et al. Citation2018), as Miller, Porter, and Barbagallo (Citation2022) recently pointed out, this tends to be determined in terms of static environmental elements or qualities that either make a space feel homely through redolence; or, in their absence, clinical or institutional. However, the concept of ‘home’, and hence of homeliness, is extraordinarily broad and notoriously difficult to pin down (McLaughlan and Richards Citation2023). In the context of healthcare design literature, implicit or explicit definitions of homeliness have tended to be based on static environmental elements and have tended to ignore the relationality of people and places and the temporal processes that ultimately lead to feelings of at-homeness (Ewart and Luck Citation2013; Steenwinkel, Baumers, and Heylighen Citation2012). Duque et al. (Citation2019, 213) make a similar point when they speak about the importance of patterns of behaviour in healthcare environments as a crucial and often-overlooked ‘element of care that contributes significantly to bringing the feeling of “home”’. Although spaces are indeed made homely through homelike décor, it is also possible that they become homely as occupants enact ordinary rituals of home life.

What our data highlighted is that a homely appearance is often inextricably tied to a homely affordance. Affordances are actions or behaviours that spaces enable or incite, as a function of their spatial or material characteristics (Withagen et al. Citation2012). Affordances were first brought to light in the 1970s lectures of architect-theorist Herman Hertzberger, who argued that the efforts of spatial designers should be concentrated on accommodating and incentivizing the widest possible spectrum of potential actions (Hertzberger Citation2005, 158–162). While this notion has been explored across educational facilities, office buildings, and acute hospital settings (Bardenhagen and Rodiek Citation2016; Choi and Bosch, Citation2013; Young and Cleveland Citation2022), we suggest it deserves more attention in the context of palliative care. Recognizing, for example, that materials have agency extending beyond how they look could change the nature of the conversations about design in this context. Throughout our interviews, there was a sense of the real physical and psychological impact that homely or clinical qualities can have on patients and their visitors, as well as their relationships with each other. Examples of visitors cutting short their stays - because children had no space to play; because rooms lacked fresh air; because furniture was uncomfortable; or the appearance of the facility caused distress - demonstrated that the environment can have a tangible impact on the time that patients and family members spend together, alongside the quality of that time. While materials and furnishings may exhibit similar affordances within palliative care to those we see within other healthcare settings, we suggest these become more significant in this context, where the therapeutic focus is on helping a patient to ‘die healed’ and where the desire to support family members through their experiences of loss is intrinsic to the philosophy of care itself (Adams Citation2016; Mount and Kearney Citation2003; McLaughlan et al. Citation2022; Palliative Care Australia Citation2022).

Privacy is necessary for enacting rituals of home and while the need for privacy is well documented within palliative care literature, the current focus tends to be limited to meeting these needs via a single-occupancy room (Brereton et al. Citation2012; Gardiner Citation2011; Hajradinovic et al. Citation2018; Miller, Porter, and Barbagallo Citation2022; Rowlands and Noble Citation2008; Wong et al. Citation2023). This does not go far enough. There are a variety of situations in which the need for privacy arises, such as when patients and relatives wish to have conversations out of earshot of others, when patients are particularly ill or would like to behave without concern for disturbing others, or with the freedom of not being watched – such as when partners wish to simply be comfortable in each other’s company. Processual ideas of homeliness extend from the more and less mundane rituals through which people make homes, such as snacking, sharing meals, sharing a bed, or watching television, to idiosyncratic habits and socially and culturally specific rituals and religious customs (Buse, Martin, and Nettleton Citation2018; Giddens Citation1991; McGann Citation2016; McLaughlan and Kirby Citation2021; McLaughlan and George Citation2022; Miller, Porter, and Barbagallo Citation2022). But homeliness is not simply about what is done, but also the way that things are done; as McGann (Citation2016, 18) has observed, ‘In domestic space we would very reluctantly walk into a neighbour’s bedroom for a chat while they lay there semi-clothed’. Certainly, in the case of the semi-enclosed verandah space discussed in the previous section, patients and family members confirmed the added comfort of having this space beyond the bedroom to receive visitors. As well as contributing to feelings of at-homeness in care environments, these active, ritualized practices are also coping mechanisms, which are ‘bound up with how anxiety is socially managed’ (Giddens Citation1991, 46). The kind of privacy required to meaningfully support these rituals is not a matter of single-occupant or multi-occupant rooms, but one of the auxiliary spaces beyond the patient room, such as exterior courtyards, gardens, balconies, communal seating areas, or private consultation rooms. Without access to such auxiliary spaces and the types of privacy they afford, patients, family members, and medical staff are forced into situations in which dignity and wellbeing can be compromised.

Strengths and limitations

Wong et al. (Citation2023, 6) recently identified, that in the literature on designing for palliative care, there is ‘an over reliance on the views of staff and family members as proxy informants for patient views and feelings’. Notwithstanding the value of such studies, speaking directly with patients about the design of hospital environments is a strength of this study, providing greater insight into the meaning of various environmental affordances for patients themselves. Conversations with architects who work in palliative care have observed the value of these kinds of deeper understandings of the patient experience in helping them to shift decision making away from the drivers of risk, cost, or convenience, to refocus decision making on matters relevant to patient wellbeing (McLaughlan and Richards, Citationin press).

A limitation of this study was that few patients nearing the end of life were interviewed. This is not uncommon among palliative care studies and reflects a reticence to impose during a patient’s last days, or in situations where they are unwell; our ethics approval precluded the recruitment of patients who were in significant pain. Yet, other scholars have pointed to the importance of gathering views from patients nearing the end of life as a person’s needs and preferences often change as they more closely approach death (MacArtney et al. Citation2015; Bell, Somogyi-Zalud, and Masaki Citation2010). Further limitations may have arisen from the decision to allow patients and family members to participate in an interview together. This decision was made in response to patient and family member requests and while it did not appear to significantly alter the kinds of responses obtained (when compared to the interviews conducted with individuals), we cannot confidently know whether participants censored certain feelings or opinions given the presence of their loved one. A final limitation of this study is that concerns of safety did not feature in these discussions. This is a result of the participant groups included, as previous research with palliative care staff confirmed that ensuring patient safety within hospital settings is of the upmost importance (McLaughlan et al. Citation2022).

Conclusion

Privacy, homeliness, and nature have long been recognized as beneficial within palliative care settings, but appreciating the extent to which these operate in accord to shape experiences of palliative care is important. The expectation that homeliness should go beyond simple appearances and, instead, support the rituals of home, is an idea we have argued for previously. However, the extent to which the provision of privacy contributes to homeliness; and to which nature supports both perceptions of homeliness and extends opportunities for privacy has not been previously recognized within the literature on designing for palliative care. More importantly, our data makes clear the impact of these environmental affordances on both the quality and quantity of time that families can spend together within a hospital setting. This is critical when designing to accommodate patients at the end of life. Patients and family members have needs for privacy that a single occupancy room cannot provide; spaces to support privacy beyond the patient room are necessary yet these often take the form (and appearance) of something closer to community recreation space than a more intimate, domestic living room. Material choices and spatial layouts have psychological and physical impacts. The implications of ignoring these impacts – be that preventing a young child from spending time with their hospitalized parent because there's no space to play quietly, or an adult from staying an extra few hours with their loved one because the room is too stuffy, or the furniture too uncomfortable – these realities should weigh heavily on designers and decision makers. Particularly so when decision making turns, as it invariably does within the complex process of hospital procurement, to questions of risk, cost, or what might be most convenient in terms of building construction and/or maintenance.

Acknowledgements

The following people generously offered their time in providing expert guidance to this 3-year research project and/or assisting with the recruitment of participants: Professor Jennifer Philip, Associate Professor Emma Kirby, Associate Professor Richard Chye, Frances Bellemore, Noula Basides, Professor Josephine Clayton, Joyce Baye, Dr Sarah Moberley, Dr Rachel Hughes, Associate Professor Peter Poon, and Linda Jay.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rebecca McLaughlan

Dr Rebecca McLaughlan is an Australian Research Council DECRA Research Fellow and Senior Lecturer at the University of Sydney, and a Registered Architect. Her research takes place at the intersections of architectural practice and the design of care environments, including palliative, paediatric and mental healthcare.

Kieran Richards

Dr Kieran Richards is a Research Associate at the University of Sydney. His research interests include the work of Deleuze and Guattari, and the relationship of healthcare design to wellbeing.

References

- Adams, A. 2016. “Home and/or Hospital: The Architectures of End-of-Life Care.” Change over Time 6 (2): 248–263. https://doi.org/10.1353/cot.2016.0015

- Bardenhagen, E., and S. Rodiek. 2016. “Affordance-Based Evaluations That Focus on Supporting the Needs of Users.” Herd 9 (2): 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/1937586715599760

- Bates, V. 2019. “Sensing Space and Making Place: The Hospital and Therapeutic Landscapes in Two Cancer Narratives.” Medical Humanities 45 (1): 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2017-011347

- Bell, C. L., E. Somogyi-Zalud, and K. H. Masaki. 2010. “Factors Associated with Congruence between Preferred and Actual Place of Death.” Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 39 (3): 591–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.07.007

- Bradshaw, S. A., E. D. Playford, and A. Riazi. 2012. “Living Well in Care Homes: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies.” Age and Ageing 41 (4): 429–440. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afs069

- Brereton, L., C. Gardiner, M. Gott, C. Ingleton, S. Barnes, and C. Carroll. 2012. “The Hospital Environment for End of Life Care of Older Adults and Their Families: An Integrative Review.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 68 (5): 981–993. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05900.x

- Buse, C., D. Martin, and S. Nettleton. 2018. “Conceptualising ‘Materialities of Care’: Making Visible Mundane Material Culture in Health and Social Care Contexts.” Sociology of Health & Illness 40 (2): 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12663

- Choi, Y.-S., and S. J. Bosch. 2013. “Environmental Affordances: Designing for Family Presence and Involvement in Patient Care.” HERD 6 (4): 53–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/193758671300600404

- Collier, A., J. L. Phillips, and R. Iedema. 2015. “The Meaning of Home at the End of Life: A Video-Reflexive Ethnography Study.” Palliative Medicine 29 (8): 695–702. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216315575677

- Duque, M., S. Pink, S. Sumartojo, and L. Vaughan. 2019. “Homeliness in Health Care: The Role of Everyday Designing.” Home Cultures 16 (3): 213–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/17406315.2020.1757381

- Ewart, I., and R. Luck. 2013. “Living from Home.” Home Cultures 10 (1): 25–42. https://doi.org/10.2752/175174213X13500467495726

- Gardiner, C., L. Brereton, M. Gott, C. Ingleton, and S. Barnes. 2011. “Exploring Health Professionals’ Views regarding the Optimum Physical Environment for Palliative and End of Life Care in the Acute Hospital Setting: A Qualitative Study.” BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 1 (2): 162–166. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2011-000045

- Giddens, A. 1991. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Hajradinovic, Y., C. Tishelman, O. Lindqvist, and I. Goliath. 2018. “Family Members’ Experiences of the End-of-Life Care Environments in Acute Care Settings – A Photo-Elicitation Study.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being 13 (1): 1511767. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2018.1511767

- Harper, D. 2002. “Talking about Pictures: A Case for Photo Elicitation.” Visual Studies 17 (1): 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725860220137345

- Hertzberger, H. 2005. Lessons for Students in Architecture. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers.

- Kayser-Jones, J., E. Schell, W. Lyons, A. E. Kris, J. Chan, and R. L. Beard. 2003. “Factors That Influence End-of-Life Care in Nursing Homes: The Physical Environment, Inadequate Staffing, and Lack of Supervision.” The Gerontologist 43 (suppl_2): 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/43.suppl_2.76

- Kilgour, K. N., F. F. Bourbonnais, and C. J. McPherson. 2015. “Experiences of Family Caregivers Making the Transition from Home to the Palliative Care Unit: Weighing the 2 Sides.” Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing 17 (5): 404–412. https://doi.org/10.1097/NJH.0000000000000178

- MacArtney, J. I., A. Broom, E. Kirby, P. Good, J. Wootton, P. M. Yates, and J. Adams. 2015. “On Resilience and Acceptance in the Transition to Palliative Care at the End of Life.” Health 19 (3): 263–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459314545696

- McGann, S. 2016. The Production of Hospice Space: Conceptualising the Space of Caring and Dying. London: Routledge.

- McLaughlan, R., and B. George. 2022. “Unburdening Expectation and Operating between: Architecture in Support of Palliative Care.” Medical Humanities 48 (4): 497–504. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2021-012340

- McLaughlan, R., and E. Kirby. 2021. “Palliative Care Environments for Patient, Family and Staff Wellbeing: An Ethnographic Study of Non-Standard Design.” BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 2021: bmjspcare-2021-003159. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-003159)

- McLaughlan, R., and K. Richards. 2023. “Beyond Homeliness: A Photo-Elicitation Study of the ‘Homely’ Design Paradigm in Care Settings.” Health & Place 79 (1): 102973.

- McLaughlan, R., and K. Richards. In press. “Evidence and Architectural Competency within the Healthcare Procurement Ecosystem.” Ardeth 10: Competency. accepted for publication September 2022.

- McLaughlan, R., K. Richards, R. Lipson-Smith, A. Collins, and J. Philip. 2022. “Designing Palliative Care Facilities to Better Support Patient and Family Care: A Staff Perspective.” Herd 15 (2): 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/19375867211059078

- Miller, E. M., J. E. Porter, and M. S. Barbagallo. 2022. “The Physical Hospital Environment and Its Effects on Palliative Patients and Their Families: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis.” Herd 15 (1): 268–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/19375867211032931

- Mount, B., and M. Kearney. 2003. “Healing and Palliative Care: Charting Our Way Forward.” Palliative Medicine 17 (8): 657–658. https://doi.org/10.1191/0269216303pm848ed

- Palliative Care Australia. 2022. “What is Palliative Care?” Accessed from: https://palliativecare.org.au/resource/what-is-palliative-care/

- Rasmussen, B. H., and D. Edvardsson. 2007. “The Influence of Environment in Palliative Care: Supporting or Hindering Experiences of ‘at-Homeness.” Contemporary Nurse 27 (1): 119–131. https://doi.org/10.5555/conu.2007.27.1.119

- Rowlands, J., and S. Noble. 2008. “How Does the Environment Impact on the Quality of Life of Advanced Cancer Patients? A Qualitative Study with Implications for Ward Design.” Palliative Medicine 22 (6): 768–774. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216308093839

- Sandelowski, Margarete. 2000. “Whatever Happened to Qualitative Description?.” Research in Nursing & Health 23 (4): 334–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G.

- Steele, R., and B. Davies. 2015. “Supporting Families in Palliative Care.” In Oxford Textbook of Palliative Nursing, edited by N. Coyle, and B. R. Ferrell. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Steenwinkel, I., S. Baumers, and A. Heylighen. 2012. “Home in Later Life.” Home Cultures 9 (2): 195–217. https://doi.org/10.2752/175174212X13325123562304

- Timmermann, C., L. Uhrenfeldt, M. T. Høybye, and R. Birkelund. 2015. “A Palliative Environment: Caring for Seriously Ill Hospitalized Patients.” Palliative & Supportive Care 13 (2): 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1017/S147895151300117X

- Ulrich, Roger S., Craig Zimring, Xuemei Zhu, Jennifer DuBose, Hyun-Bo Seo, Young-Seon Choi, Xiaobo Quan, and Anjali Joseph. 2008. “A Review of the Research Literature on Evidence-Based Healthcare Design.” Herd 1 (3): 61–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/193758670800100306

- Withagen, R., H. J. de Poel, D. Araújo, and G. J. Pepping. 2012. “Affordances Can Invite Behavior: Reconsidering the Relationship between Affordances and Agency.” New Ideas in Psychology 30 (2): 250–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2011.12.003

- Wong, K., R. McLaughlan, J. Philip, and A. Collins. 2023. “Designing the Physical Environment for Inpatient Palliative Care: A Narrative Review.” BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 13 (1): 45–51. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-003087

- Wright, A. A., N. L. Keating, T. A. Balboni, U. A. Matulonis, S. D. Block, and H. G. Prigerson. 2010. “Place of Death: Correlations with Quality of Life of Patients with Cancer and Predictors of Bereaved Caregivers’ Mental Health.” Journal of Clinical Oncology 28 (29): 4457–4464. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3863

- Young, F., and B. Cleveland. 2022. “Affordances, Architecture and the Action Possibilities of Learning Environments: A Critical Review of the Literature and Future Directions.” Buildings 12 (1): 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12010076

- Zadeh, R. S., P. Eshelman, J. Setla, L. Kennedy, E. Hon, and A. Basara. 2018. “Environmental Design for End-of-Life Care: An Integrative Review on Improving the Quality of Life and Managing Symptoms for Patients in Institutional Settings.” Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 55 (3): 1018–1034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.09.011