ABSTRACT

Background

As Canada continues to address challenges related to the opioid crisis, individuals suffering from opioid use disorder (OUD) can be especially vulnerable to physical and psychological destabilization after surgery. Adopting a harm reduction approach postoperatively can be a success factor for safe recovery and satisfactory analgesia.

Purpose

We present the case of a 40-year-old patient (referred to as DC) with OUD using illicit fentanyl, heroin, and oxycodone preoperatively and admitted for an elective liver resection for steroid-induced hepatoma. Despite a preoperative anesthesia assessment and the initiation of a standard balanced multimodal analgesic regimen, suboptimal analgesia was evident in the first 24 h postoperatively. This lack of analgesic efficacy precipitated DC’s use of illicit self-injected intravenous (IV) opioid and significant emotional distress. To address this, a nurse practitioner and anesthesiologist within the Toronto General Hospital acute and transitional pain program and the surgical team quickly met and adopted a harm reduction approach to manage DC’s postoperative pain and emotional distress. The ultimate goal was to eliminate self-administration of illicit IV opioids and prevent DC from attempting to leave hospital against medical advice. Following an interprofessional team discussion that included DC, IV fentanyl was offered via a patient-controlled analgesia pump to DC’s satisfaction (exceeding standard settings), providing acceptable pain relief. To our knowledge, DC did not self-administer additional illicit drugs during the remainder of hospitalization.

Outcome

This harm reduction approach resulted in DC’s safe recovery, achievement of postoperative functional milestones, and continued engagement with outpatient pain treatment.

RÉSUMÉ

Contexte: Alors que le Canada continue de faire face aux défis de la crise des opioïdes, les personnes souffrant de troubles liés à l’utilisation d’opioïdes (TUO) peuvent être particulièrement vulnérables à la déstabilisation physique et psychologique après une chirurgie. L’adoption d’une approche de réduction des méfaits en postopératoire peut être un facteur de réussite pour un rétablissement sûr et une analgésie satisfaisante.

Objectif: Nous présentons le cas d’un patient de 40 ans (appelé DC) atteint de TUO faisant usage de fentanyl, d’héroïne et d’oxycodone illicites en préopératoire et admis pour une résection hépatique élective pour un hépatome induit par des stéroïdes. Malgré une évaluation anesthésique préopératoire et l’instauration d’un schéma analgésique multimodal équilibré standard, une analgésie sous-optimale était évidente dans les 24 premières heures postopératoires. Ce manque d’efficacité analgésique a précipité l’utilisation par DC d’opioïdes illicites auto-injectés par voie intraveineuse (IV) et une détresse émotionnelle importante. Pour résoudre ce problème, une infirmière praticienne et l’anesthésiste du programme de douleur aiguë et transitionnelle de l’Hôpital général de Toronto et l’équipe chirurgicale se sont rapidement rencontrés et ont adopté une approche de réduction des méfaits pour gérer la douleur postopératoire et la détresse émotionnelle de DC. L’objectif ultime était d’éliminer l’auto-administration d’opioïdes IV illicites et d’empêcher DC de tenter de quitter l’hôpital contre l’avis médical.

À la suite d’une discussion d’équipe interprofessionnelle à laquelle DC a participé, le fentanyl IV par pompe analgésique contrôlée par le patient à la satisfaction de DC (au-delà des paramètres standard) a été proposée, ce qui lui a procuré un soulagement de la douleur acceptable. À notre connaissance, DC ne s’est pas auto-administré de drogues illicites supplémentaires pendant le reste de l’hospitalisation.

Résultat: Cette approche de réduction des méfaits a permis à DC de se rétablir en toute sécurité, d’atteindre des jalons fonctionnels postopératoires et d’assurer son engagement continu envers le traitement de la douleur en ambulatoire.

Introduction

Participant and Setting

In the preoperative anesthesia assessment clinic, The Toronto General Hospital has a mechanism to identify patients presenting for surgery consuming high-dose opioids and/or those who self-identify as recreational drug consumers. Once this has been identified, both the acute and transitional pain teams are notified. DC was therefore known to the acute pain service and had disclosed preoperatively the consumption of up to 3 g of illicitly sourced fentanyl and heroin daily. He consumed this mostly intravenously. DC was also in a supervised methadone maintenance program, requiring 200 mg methadone per day for opioid agonist treatment. DC presented to our hepatic surgery specialists to undergo an extended liver resection for a medication-induced hepatoma and had an otherwise insignificant health history. DC was also assessed by the Transitional Pain Service (as requested by his surgical team) preoperatively to determine the best perioperative management course and to receive preoperative pain education prior to surgery and to discuss the implications of his opioid use disorder (OUD) on his perioperative care, a situation that is becoming more common as the illicit opioid crisis continues to worsen.

Preoperative Anesthesia Assessment

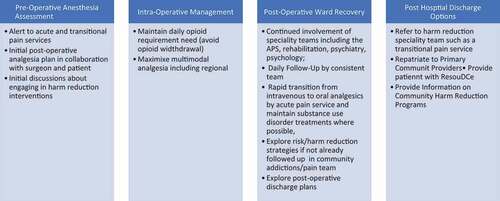

Preoperatively, discussions among the patient, specialists of the acute and transitional pain services (anesthesiologists and a nurse practitioner), and the surgical team identified that the patients would require comprehensive multimodal analgesia including suitable regional interventions. Additionally, they all recognized that harm reduction interventions would be necessary postoperatively, including close opioid monitoring as well as prevention of withdrawal and reduction of psychological distress. describes this critical period, during which patient education regarding postoperative pain management and harm reduction intervention was provided.

Figure 1. Perioperative pain and substance use disorder clinical pathway developed for patients at Toronto General Hospital

Specific harm reduction strategies discussed at this point preoperatively included a motivational interviewing style using a nonjudgmental approach. That is, providers conscientiously adopted a patient-centered conversation style to elicit information and reinforce DC’s motivation to adhere to the harm reduction plan postoperatively. DC responded to this approach, enabling the care team to further address education pertaining to pain relief and the unintended consequences of self-administered unprescribed medication postoperatively. Essential during this preoperative visit was the connection established by the pain service health professionals, by whom DC would also be evaluated postoperatively. This plan for consistency in care providers was reassuring to DC.

Postoperative analgesic options were also discussed during this anesthesia assessment. Collectively, the anesthesia and surgical teams agreed to avoid neuraxial analgesia because the expected remnant liver would be less than 85% and this could result in complex coagulopathy. Based on the size and location of the tumor, a “Mercedes-Benz” incision was expected. Clear land markings for abdominal wall catheter placement for local anesthetic infusion remained unclear. Intravenous ketamine was offered and declined by DC due to previous hallucinations. Intravenous lidocaine was also considered at this point, and the dose for the same was lowered to account for a lower liver volume and its ability to metabolize lidocaine. Additional limitations included the reduced reliance on other conventional evidence-based analgesics including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications and acetaminophen from both anticoagulation and liver function considerations in the context of the liver resection. Given these restrictions, the patient was going to be reliant on intravenous (IV) opioid patient-controlled analgesia postoperatively.

Postoperative Ward Recovery

Postoperatively, DC followed a typical recovery period trajectory. He was initially monitored in our postanesthetia recovery room for the first few hours. This was followed by transfer to the ward, where he was placed in a step-down room with the required vital signs, hemodynamic, and fluid monitoring typical for this procedure. His postoperative analgesic regimen included a continuous IV lidocaine infusion of 1 mg/kg/h, 30 mg of oral ketamine four times per day (this route was less hallucinogenic for him), and IV patient-controlled fentanyl. His opioid agonist treatment (methadone 200 mg per day) was restarted as soon as he was able to receive oral medication (at approximately 48 h postoperative). This was also divided in to three doses per day to leverage its benefit.

On postoperative day 1, DC was assessed by the pain service nurse practitioner, who was involved in organizing his postoperative ward recovery (described in ). DC disclosed having self-administered heroin intravenously. He reported injecting heroin due to fear of uncontrolled pain and trusted that the heroin would help him cope and prevent withdrawal. He reported moderate surgical pain at rest and on occasion severe upon movement, the latter of which was relieved with the use of IV patient-controlled fentanyl. He did not exhibit any signs or symptoms of opioid withdrawal (Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale score <4). Notably, he indicated that knowing the pain service team preoperatively and their consistent follow-up postoperatively instilled trust that he would be able to safely disclose the choice of self-injection.

DC also reported significant psychological distress due to this hospitalization and that coping with the postoperative recovery was much more challenging than he had anticipated. DC expressed feeling stigmatized by the care team. He attributed this to the questions he was asked by his care providers about his requirement of fentanyl but did not describe any other health provider behaviors suggesting judgment toward him. He described health provider questions related to his use of fentanyl—specifically requiring more than was available every 4 h—as frustrating, and this almost caused him to leave hospital against medical advice.

Motivational interviewing strategies were used to validate DC’s experience of stigmatization, evaluate the decision to leave against medical advice (AMA), and collaborate on strategies to improve pain management. The risks of leaving AMA were addressed with DC, including a worsening postoperative recovery trajectory and/or death. Additional options for pain management and opioid withdrawal were discussed. Ultimately, a harm reduction approach was adopted by the ward pharmacists, nurses, surgical team, and pain specialists in extensive consultation with DC (see ). This approach addressed several elements of his care, the first of which was pain relief. All health providers agreed that the patient could continue to use liberal amounts of IV patient-controlled fentanyl in a monitored environment. This included removing the 4-h limit on the amount of fentanyl he was originally prescribed. A 4-h limit on a patient-controlled analgesia device is typical and a strategy to prevent excessive use that could result in sedation. Additionally, the clinically feasible addition of multimodal analgesia was evaluated daily. The second element of this harm reduction approach included modification of the environment, including consistency in health care providers. This meant that designated members of each profession involved in his care would care for him on a consistent basis throughout the day and night. This level of predictable staffing and established relationships with care providers contributed to DC not feeling as though he needed to leave AMA.

On a daily basis, DC required approximately 200 μg/h of IV patient-controlled fentanyl (60 μg per patient self-administration dose), six times the typical self-administered “safe” doses. He continued to have high opioid requirements for the first three to four postoperative days, using up to 4 g of IV fentanyl in the absence of respiratory support or sedation. Intravenous lidocaine was also provided to the patient for analgesia and opioid sparing benefit at a dose of 60 mg/h. As soon as DC was able to tolerate sips of clear fluid (approximately 48 h postoperative), and in the absence of anemia, oral celecoxib was added to his regimen, as well as a daily dose of methadone administered in a manner to also provide analgesic benefit (daily dose divided in to three). DC was in a step-down unit the first two days, with more regular respiratory and hemodynamic monitoring compared to a regular surgical ward.

DC’s recovery progressed smoothly without any further illicit fentanyl or heroin. He reported feeling supported emotionally and endorsed having trust in the health care providers in relation to their prioritization of his recovery and pain management as their primary goal. Once deemed stable from the surgical recovery perspective, DC continued recovery on the regular ward. The consistency in health care providers was helpful in reinforcing DC’s confidence that his recovery was a priority. DC was able to achieve functional recovery milestones steadily and was able to ambulate by the second day postoperative. To the teams’ knowledge, no further self-administered illicit fentanyl or heroin occurred prior to discharge. His dose of methadone was changed to 100 mg twice a day in preparation for hospital discharge (matched to his outpatient dose). Upon discharge, the patient took one dose of methadone to take home and was repatriated with the methadone prescriber in the community for follow-up.

A key achievement for our organization was the implementation of a customized harm reduction approach in the perioperative period. In addition to the analgesia provided, our success was addressing with the patient what would be safe to use in the perioperative period and engaging in a trusting, nonjudgmental, and open dialogue, including the possibility of additional harm reduction measures following hospital discharge. The patient expressed consideration of rotation in opioid agonist treatment (i.e., transition to Suboxone) at some point in the future, meaning that DC was currently in the precontemplative phase for this transition. DC had declined the same previously. At the time of hospital discharge, options as an outpatient for both pain relief and treatment of his opioid use disorder were reviewed with him.

Post Hospital Discharge Options

DC remained in hospital approximately three weeks, a typical recovery for the extensive life-saving surgery performed. At the time of hospital discharge, DC decided to return to his opioid agonist therapy provider in the community and did not need the help of the Transitional Pain Service team. His surgical recovery was monitored at timely intervals as determined by the surgical team, the first of these at two weeks postdischarge. During the visits with his surgeon, DC expressed being able to maintain a satisfactory quality of life, physical functioning, and a slow but continued reduction in the use of illicit opioids. DC was again offered the services of the Toronto General Hospital Transitional Pain Service but he identified a harm reduction clinic close to his home and chose to pursue continued medical treatment through them with the aim of integrating psychological help long-term.

Discussion

This case report identifies the important intersection of pain management, OUD, and the necessity of harm reduction interventions in the postoperative recovery period. As patients with OUD and the overdose crisis continue to challenge the Canadian health care system, surgeons, anesthesiologists, and nurse practitioners in perioperative settings will be required to provide individualized harm reduction interventions perioperatively. This type of implementation will be a challenge in some institutions. Hospitalized patients with OUD continue to report feelings of stigmatization.Citation1 Between 25% to 30% of patients using illicit opioids will also discharge themselves from hospital AMA and have higher rates of mortality and morbidity, often requiring rehospitalization.Citation2,Citation3 In the case of DC, self-discharge from hospital in the early postoperative recovery period would have resulted in significant harm and possibly death.

We identified key aspects of DC’s care that we may not have fully appreciated a priori and these will benefit us for future patient care. First, a more comprehensive preoperative harm reduction strategy could have been more impactful. Though DC had met with the surgical and pain services to discuss management of his opioid medications and strategies to prevent withdrawal and provide pain relief, minimal attention was paid to his fears around these topics. He disclosed these fears postoperatively, including anxiety and fear around adequate analgesia, resulting in self-administration of an illicit substance. Patients known to have catastrophic thinking and anxiety also have a higher risk of OUD.Citation4,Citation5,Citation15 DC’s fears could potentially have been mitigated by preoperative cognitive behavioral therapy or mindfulness session because these fears/emotions ultimately triggered his use of illicit substances in the immediate postoperative period. DC’s postoperative distress due to his fears around adequate pain control and concerns regarding stigmatization by staff as well as severe postoperative pain likely contributed to IV heroin use on postoperative day 1. In the future, a more thorough preoperative understanding of patients’ fears and anxieties as well as an understanding of personal coping strategies could facilitate better postoperative psychological outcomes. Secondly, we underestimated the educational needs of the ward interprofessional staff in caring for a patient with OUD. We learned that clear communication in advance of the patient’s arrival could have mitigated some of the early postoperative issues that arose and that contributed to DC’s feeling of being stigmatized. Key relational and psychological support strategies need to be established early and are essential for a smooth and successful in-hospital recovery. These support strategies are intensive and multidisciplinary (medical and nursing staff, rehabilitation specialists, pain specialists and psychologists). Nursing education regarding harm reduction and the use of these have shown to benefit patients with various substance use disorders.Citation6 We have recognized this as an area of capacity building among nurses in our organization, as we encounter more patients who require invasive interventions and who have concurrent OUD.

Despite initial discussions addressing the changes in DC’s physiology postoperatively and the need for hemodynamic and fluid monitoring, DC was determined to leave hospital due to perceptions of stigma from health care providers and the perception of inadequate pain relief. The pain medicine nurse practitioner and anesthesiologist adopted a collaborative, patient-centered approach using interventional and relational strategies from motivational interviewing and general supportive counseling. These strategies involved fostering a nonjudgmental environment with active validation of the patient’s need for an alternative pain management approach. Both of the aforementioned interventions have yielded positive results in other patients,Citation7,Citation8 and we focused on the elements of self-efficacy, postoperative recovery, and the patient’s engagement in health care plans. Following motivational interviewing and general supportive counseling offered by the pain service nurse practitioner and anesthesiologist, DC was able to arrive at the decision to remain in-hospital. Follow-up from the pain service involved multiple visits during the day and overnight with consistent providers. Although the postoperative recovery period was not a suitable time period for introduction of additional opioid agonist treatment for harm reduction, the patient was able to arrive at a point of contemplation and accepted resources offered to him as an outpatient. At the time of hospital discharge, DC indicated that the essential success factor in his recovery was the opportunity to engage in authentic open discussions that addressed harm reduction and pain relief in a balanced, nonjudgmental, and collaborative manner.

This article highlights the need for providers to adopt strategies to reduce stigma and enhance patient engagement during the perioperative period. Though this holds true for all patients, it is particularly critical for individuals who already hold themselves to be marginalized, such as those with OUD. These individuals might be best served by multidisciplinary perioperative care, including enhanced psychological assessment and intervention. Brief psychological assessment can identify perceptions of stigma and invalidation and determine readiness for behavioral change. Motivational interviewing on the part of the multidisciplinary team, pre- and postoperatively, can then be used to enhance patient engagement, encourage adherence to collaborative harm reduction strategies, and plan for challenges that may arise during the postoperative period. Even an single session of motivational interviewing has received extensive support as a means to enhance patient self-efficacy, readiness to change, and treatment adherence.Citation9,Citation10 Moreover, the collaborative, patient-centered motivational interviewing approach can foster a nonjudgmental, validating, positive relationship with the care team after surgery. Adoption of these relational strategies was a key component in the development of rapport with DC, which was necessary for the implementation of harm reduction postoperatively.

presents a pathway created by our team for patients struggling with a substance use disorder and presenting to our surgical teams to help guide the engagement of available services for DC. This pathway was used to complement the postoperative enhanced recovery after surgery guidelines that our organization has adopted.Citation11,Citation12,Citation13,Citation14 An essential missing element in these enhanced recovery after surgery guidelines is the recognition that they may not serve patients with OUD. A key learning for our team was the understanding of the need for intense and individualized services for patients in the future for whom surgery is necessary to achieve expected postoperative recovery milestones, reduce stigma, and keep them in-hospital. Included in this was the opportunity to introduce tangible harm reduction interventions. This pathway was beneficial in guiding our entire team to help DC achieve a safe and comfortable recovery period. We have continued to successfully utilize this pathway for other patients with OUD undergoing expected and unexpected surgery.

Ethics Consent

DC provided written informed consent to have this report published.

Research Ethics Board

The University Health Network Research Ethics Board was appraised of this case report and advised that research ethics board approval was not required in a publication involving fewer than three patients. Nonetheless, we ensured that the patient was aware of the publication and protection of his identity and we received a signed approval from the patient for the same. During the consent process the patients was offered the opportunity to review the manuscript prior to publication and declined to do so. The participant also declined to take a copy of the consent form that was offered. The participant additionally allowed the research team at their discretion to present this case as a learning opportunity to students and clinicians.

Disclosure Statement

Salima S. J. Ladak has not declared any conflicts of interest. Gonzalo Sapisochin has not declared any conflicts of interest. P. Maxwell Slepian has not declared any conflicts of interest. Hance Clarke has not declared any conflicts of interest.

References

- Knaak S, Mantler E, Szeto A. Mental illness-related stigma in health care: barriers to access and care and evidence based solutions. Health Care Manage Forum. 2017;30(2):111–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0840470416679413.

- Lianping T, Lianlian T. Leaving the hospital against medical advice among people who use illicit drugs: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):e53–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302885.

- Sclar DA, Robison LM. Hospital admission for schizophrenia and discharge against medical advice in the United States. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12:2.

- Bartlett R, Brown L, Shattell M, Wright T, Lewallen L. Harm reduction: compassionate care of persons with addictions. Med Surg Nurs. 2013;22:349–58.

- Martel M, Wasan AD, Jamison RN, Edwards RR. Catastrophic thinking and increased risk for prescription opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;132:335–41.

- Katz J, Weinrib A, Fashler S, Katznelson R, Shah B, Ladak S, Jiang J, Li Q, McMillan K, Santa Mina D, et al. The Toronto General Hospital transitional pain service: development and implementation of a multidisciplinary program to prevent chronic postsurgical pain. J Pain Res. 2015;8:695–702. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S91924.

- Alfandre DJ. “I’m going home”: discharges against medical advice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(3):255–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.4065/84.3.255.

- Hah JM, Trafton JA, Narasimhan B, Krishnamurthy P, Hilmoe H, Sharifzadeh Y, Huddleston JI, Amanatullah D, Maloney WJ, Goodman S. Efficacy of motivational-interviewing and guided opioid tapering support for patients undergoing orthopedic surgery (MI-Opioid Taper): a prospective, assessor-blind, randomized controlled pilot trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;28:100596. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100596.

- Berman AH, Forsberg L, Durbeej N, Källmén H, Hermansson U. Single-session motivational interviewing for drug detoxification inpatients: effects on self-efficacy, stages of change and substance use. Subst Use Misuse. 2010 Feb 1;45(3):384–402. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/10826080903452488.

- Palacio A, Garay D, Langer B, Taylor J, Wood BA, Tamariz L. Motivational interviewing improves medication adherence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2016 Aug;31(8):929–40.\. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3685-3.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Enhancing motivation for change in substance use disorder treatment. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2019. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series No. 35. SAMHSA Publication No. PEP19-02-01-003.

- Taha S. Best practices across the continuum of care for treatment of opioid use disorder. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction; 2018.

- Agarwal V, Divatia J. Enhanced recovery after surgery in liver resection: current concepts and controversies. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2019;72(2):119–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.4097/kja.d.19.00010.

- Melloul E, Hubner M, Scott M, Snowden C, Prentis J, Dejong C, Garden O, Farges O, Kokudo N, Vauthey J, et al. Guidelines for peri-operative care for liver surgery: enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) society recommendations. World J Surg. 2016;40(10):2425–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-016-3700-1.

- Morasco B, Turk D, Donovan M, Dobscha S. Risk for opioid misuse among patients with a history of substance use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;127(1–3):193–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.032.