ABSTRACT

Background

Spinal fusion surgery is a common and painful musculoskeletal surgery performed in the adolescent population. Despite the known risk for developing chronic postsurgical pain, few perioperative psychosocial interventions have been evaluated in this population, and none have been delivered remotely (via the Internet) to improve accessibility.

Aims

The aim of this single-arm pilot study was to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of the first Internet-based psychological intervention delivered during the perioperative period to adolescents undergoing major spinal fusion surgery and their parents.

Methods

Thirteen adolescents (M age = 14.3; 69.2% female) scheduled for spine fusion surgery and their parents were provided access to the online psychosocial intervention program. The program included six lessons delivering cognitive-behavioral therapy skills targeting anxiety, sleep, and acute pain management during the month prior to and the month following surgery. Feasibility indicators included recruitment rate, intervention engagement, and measure completion. Acceptability was assessed via quantitative ratings and qualitative interviews.

Results

Our recruitment rate was 81.2% of families approached for screening. Among participating adolescent–parent dyads, high levels of engagement were demonstrated (100% completed all six lessons). All participants completed outcome measures. High treatment acceptability was demonstrated via survey ratings and qualitative feedback, with families highlighting numerous strengths of the program as well as areas for improvement.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that this online psychosocial intervention delivered during the perioperative period is feasible and acceptable to adolescents and their parents. Given favorable feasibility outcomes, an important next step is to evaluate the intervention in a full-scale randomized controlled trial.

RÉSUMÉ

Contexte: La chirurgie de fusion vertébrale est une chirurgie musculo-squelettique courante et douloureuse pratiquée chez la population adolescente. Malgré le risque connu de développer une douleur post-chirurgicale chronique, peu d’interventions psychosociales périopératoires ont été évaluées chez cette population, et aucune n’a été dispensée à distance (par Internet) pour améliorer son accessibilité.

Objectifs: L’objectif de cette étude pilote à un seul volet était d’évaluer la faisabilité et l’acceptabilité de la premiére intervention psychologique sur Internet destinée aux adolescents subissant une chirurgie majeure de fusion vertébrale et à leurs parents, dispensée pendant la période périopératoire.

Méthodes: Treize adolescents (âge M = 14,3 ; 69,2 % de filles) devant subir une chirurgie de fusion vertébrale et leurs parents ont eu accés au programme d’intervention psychosociale en ligne. Le programme comprenait six leçons permettant d’acquérir des compétences de thérapie cognitivo-comportementale ciblant l’anxiété, le sommeil et la prise en charge de la douleur aiguë pendant le mois précédant et le mois suivant la chirurgie. Les indicateurs de faisabilité comprenaient le taux de recrutement, l’engagement dans l’intervention et la réponse aux questionnaires de mesure des résultats. L’acceptabilité a été évaluée au moyen d’évaluations quantitatives et d’entretiens qualitatifs.

Résultats: Notre taux de recrutement était de 81,2 % des familles approchées pour le dépistage. Parmi les dyades adolescents-parents participantes, des niveaux élevés d’engagement ont été démontrés (100 % ont terminé les six leçons). Tous les participants ont rempli les questionnaires de mesure des résultats. Une acceptabilité élevée du traitement a été démontrée par le biais de sondages et de rétroaction qualitative, les familles mettant en évidence de nombreux points forts du programme ainsi que les points à améliorer.

Conclusions: Ces résultats indiquent que cette intervention psychosociale en ligne dispensée pendant la période périopératoire est faisable et acceptable pour les adolescents et leurs parents. Étant donné les résultats de faisabilité favorables, une prochaine étape importante consistera à évaluer l’intervention dans le cadre d’un essai contrôlé randomisé à grande échelle.

Introduction

Spinal fusion surgery is a common and painful musculoskeletal surgery performed in the adolescent population for idiopathic spinal deformities (e.g., scoliosis). Studies demonstrate that most youth undergoing spinal fusion experience moderate to high pain intensity immediately after surgery and are at risk for having persistent postsurgical pain.Citation1–6 Of particular concern is that up to 20% of youth have persistent postsurgical pain, often accompanied by functional limitations and impairments in health-related quality of life.Citation7–10 Identifying risk factors for persistent postsurgical pain is an active area of investigation, and studies have found that acute pain in the immediate postsurgical period as well as psychosocial risk factors predict the transition from acute to chronic postsurgical pain.Citation7,Citation8,Citation11–14

Building from this work, Rabbitts et al.Citation15 proposed a biopsychosocial conceptual model of the transition from acute to chronic postsurgical pain (CPSP) in adolescents, defined as pain that impacts quality of life persisting at least 3 months after surgeryCitation11,Citation16 They identified several modifiable psychosocial risk factors that can be targeted perioperatively to reduce the occurrence of CPSP and improve health outcomes, including adolescent anxiety, sleep disruption, parental distress, and low pain self-efficacy. Psychosocial interventions are urgently needed to improve postsurgical pain outcomes for youth and to prevent the transition from acute to chronic postsurgical pain. To date, a small body of literature exists on psychological interventions for postoperative pain in youth. In a recent systematic review by Davidson et al.Citation17 psychological interventions as a whole were effective in reducing children’s self-reported pain in the short term. However, unfortunately, data on the effects of psychological interventions on longer-term pain outcomes (including CPSP) were limited.Citation17

Opportunities exist before and following surgery to provide psychological interventions to youth and families, yet resources are not typically available in the perioperative model to provide this type of care.Citation18 Qualitative research with adolescents, families, and health care providers identified a need for and gaps around psychosocial preparation and pain self-management for youth undergoing major surgery.Citation19 However, families identified limited time and the burden of perioperative appointments as potential barriers to participating in a perioperative program, endorsing interest in web-based or mobile applications to enable participation.Citation19 Digital health interventions using web-based and mobile applications have been successfully used to deliver psychological interventions to other pediatric populations,Citation20,Citation21 and thus we anticipated they would also be relevant and feasible for youth undergoing spinal fusion surgery.

The primary aim of this single-arm pilot study was therefore to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of an Internet-based psychological intervention delivered during the perioperative period to youth undergoing spinal fusion for idiopathic spinal deformities and their parents. Intervention strategies followed a cognitive-behavioral framework and addressed three primary targets: anxiety/distress (adolescent and parent), sleep, and acute pain management, with specific skills training delivered during the pre- and postoperative periods. We hypothesized that intervention feasibility would be demonstrated through (1) reaching at least a 50% recruitment rate of the study population, (2) high treatment engagement as shown by completion of at least five of six lessons and telephone calls with study coaches by 75% of the sample, and (3) retaining at least 80% of youth in the study with complete assessments. We also expected that participants would rate the intervention as highly acceptable on self-report measures and qualitative interviews but may also have suggestions for modifying the program.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Setting

Participants included 13 adolescents (69.2% female) ages 12 to 17 years who were scheduled for elective inpatient spinal surgery (spine fusion) at a university-affiliated children’s hospital in the northwestern region of the United States and their parent/caregiver (i.e., 13 adolescent–parent dyads, n = 26 participants). The standard of care at this hospital included a preoperative visit at the anesthesia clinic to complete preanesthesia medical evaluation; a preoperative appointment at the surgery clinic to complete medical history, physical exam, and surgical consent, a postprocedure phone call on postdischarge day 3; and surgery appointments at approximately 1, 3, 6, and 12 months postsurgery.

Participants were recruited from July 2017 to November 2017. Data collection for the study was completed in April 2018. The study was approved by the Seattle Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board, Seattle Washington (IRB approval Number STUDY00000679). Parents provided written consent and adolescents provided written assent prior to any research procedures.

Recruitment

Study staff identified adolescents with scheduled spine fusion surgery meeting inclusion criteria from automated reports generated from the electronic medical record at a university-affiliated children’s hospital. Potential youth participants and their parents were mailed a study flyer and invitation letter informing them of study eligibility. Study staff contacted families at least 4 to 8 weeks before surgery to complete eligibility screening and enrollment via phone.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were (1) ages 10 to 18 years and (2) scheduled for elective spine fusion surgery for idiopathic scoliosis or kyphosis. Potential participants were excluded if they (1) had chronic or complex health conditions such as cancer, neurodegenerative or neurological disorders, or a prior history of major surgery; (2) had major psychiatric condition requiring inpatient care; (3) had a cognitive or developmental delay; (4) were unable to read English well enough to complete questionnaires or the study intervention; or (5) did not have personal Internet access on any device (e.g., phone, computer).

Trial Design and Procedures

This was a single-arm pilot feasibility study of an Internet-based psychosocial intervention including presurgery and postsurgery intervention phases. The preoperative intervention phase began 4 to 6 weeks before scheduled surgery and the postoperative phase began 1 week postsurgery. Youth and parents completed a baseline assessment before receiving the intervention (T1: baseline/4–8 weeks before surgery). Participants completed a second and third assessment following completion of the presurgical and postsurgical intervention phases, respectively (T2: midintervention/1 week before surgery; T3: postintervention/6–8 weeks postsurgery). A final follow-up assessment was completed 3 months postsurgery (T4).

All study assessments were completed online using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture)Citation22 via e-mail/text survey links and included standardized measures. REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies. Participants received e-mail or phone reminders by study staff to complete survey measures. Participants received gift card incentives for completing study assessments.

Description of Intervention

All adolescents and parents were provided access to the Internet-based psychosocial intervention program. There were separate adolescent and parent versions of the program. The intervention was built in REDCap, with links to lessons sent every 1 to 2 weeks to participants via e-mail in each intervention phase at the beginning of the lesson window (see ). The core components of the program followed a cognitive-behavioral therapy framework where participants learn about the link between behavior, thoughts, and feelings and were intended to address three primary targets: anxiety (teen and parent), sleep, and pain coping skills. In the preoperative period, the core strategies included thought restructuring, thought stopping, relaxation strategies (e.g., deep breathing, imagery), and sleep hygiene, and in the postoperative period the core strategies included behavioral activation, activity pacing, and several relaxation strategies (e.g., mindful breathing, “mini relaxation”). Postoperative content also included select cognitive-behavioral strategies taught in the preoperative intervention phase that were reviewed and applied to the postoperative context (e.g., thought replacement, sleep hygiene; see for further details).

Table 1. Summary of adolescent and parent intervention timing and content.

The content was developed by an interdisciplinary team including patient representatives as well as experts in pediatric perioperative and pain medicine, pediatric psychology, and remotely delivered psychological interventions. The content was further informed by patient, parent, and provider stakeholder input.Citation19 The program included six core lessons developed separately for children and parents: three delivered during the presurgical phase and three delivered during the postsurgical phase. An accompanying behavioral assignment was given at the end of each lesson to assist participants in skills practice and acquisition (e.g., “Practice your deep breathing skill several times each day”); assignment completion was not tracked. Content included text and pictures and provided a combination of didactic instruction and narrative examples incorporated throughout the program. The focus of each lesson was relevant to the timing of the perioperative period (e.g., “Getting ready for the hospital” and “Coping at home after surgery”).

To supplement the Internet intervention, support was provided through coaching calls (5–10 min by phone) following each lesson. Study coaches were PhD-level postdoctoral psychology fellows with previous experience in cognitive-behavioral therapy for pain management. Coaches encouraged participants to practice the skills taught within the course and identify ways to apply skills to their individual/family context. To standardize interactions with participants, coaches followed a study coach manual and were supervised by a licensed clinical psychologist.

Lessons were designed to take approximately 20 to 30 min to complete for a total treatment time of approximately 120 to 180 min with an additional 30 to 60 min of coach contact time.

Adolescent Version

The adolescent version of the psychosocial intervention provided instruction in cognitive-behavioral strategies intended to ameliorate anxiety/distress, improve sleep, and reduce pain. Specifically, adolescent lessons included psychoeducation on pain and recovery and instruction in cognitive skills (e.g., recognizing stress, thought restructuring), relaxation training (e.g., deep breathing, mindfulness), behavioral strategies (e.g., activity pacing, pleasant activity scheduling), and sleep hygiene (optimizing sleep duration and sleep quality).

Parent Version

The parent version of the intervention provided instruction in cognitive-behavioral strategies to reduce parent anxiety/distress and support their teen’s recovery and use of coping strategies. Specifically, parent lessons delivered instruction in cognitive strategies (e.g., thought restructuring), relaxation strategies (e.g., deep breathing), as well as on parent preparation before surgery (e.g., gathering information, talking to your teen before surgery), strategies for recovery following surgery (e.g., the importance of parent self-care), and operant strategies to support their teen’s use of coping skills (e.g., reinforcement, praise).

Measures

Demographic Characteristics

Parents reported on their relationship to the adolescent, household income, education, and race/ethnicity. Parents also reported on their child’s sex, age, and race.

Program Feasibility

Program feasibility was assessed using (1) study recruitment/enrollment statistics, (2) intervention engagement, and (3) rate of completion of study time points and assessments. The recruitment rate and enrollment rate were computed from schedule and screening data. Treatment engagement was measured by the number of completed intervention lessons in the presurgical and postsurgical program and the number of completed coaching calls. Retention and assessment completion were measured by the percentage of youth completing each of the four assessment time points and the completion of survey measures.

Program Acceptability

Program acceptability was assessed using quantitative and qualitative data. Youth and parent participants completed a five-item program evaluation survey to provide quantitative ratings of program acceptability, including items related to convenience, usefulness, accessibility, and understandability. Participants completed the program evaluation survey following completion of the presurgical and postsurgical lessons (i.e., as part of their T2 and T3 assessments). All items were scored on a 5-point Likert rating scale, with higher scores indicating greater acceptability and satisfaction.

All parent and teen participants who completed the online program were invited to participate in an optional qualitative interview to assess program satisfaction and obtain feedback. Of the 12 dyads (one family was withdrawn; see ”Intervention Engagement and Adherence” below for further details), one family could not be contacted and four families declined participation in the qualitative interviews. Thus, a total of seven parents and seven adolescents agreed to participate and completed interviews. Qualitative interviews included a semistructured set of questions and probes intended to elicit participants’ experiences with and feedback on the program’s components (e.g., skills) and general structure (e.g., coaching calls) of the program. Interviews were conducted by a postdoctoral fellow in pediatric psychology. Parents and adolescents were interviewed separately by phone and all interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed.

Questionnaire Measures

Primary measures included adolescent report on pain severity, pain interference, and health-related quality of life. Secondary measures included adolescent report on anxiety (State–Trait Anxiety Inventory–State Scale; 20 itemsCitation23) sleep quality (Adolescent Sleep Wake Scale; 10-item short versionCitation24), and pain coping skills (Pain Coping Questionnaire; 39 itemsCitation25). Parents also reported on parental distress using the Brief Symptom Inventory (18-item versionCitation26). Because the current study aimed to determine feasibility, we examined the rate of measure completion at each time point and present baseline data on the following primary measures to describe the study sample.

Pain Intensity and Interference

Youth completed one item from the PROMIS Pain Intensity scale (Pediatric Version)Citation27 measuring average pain intensity over the previous 7 days with an 11-point numerical rating scale ranging from 0 to 10.Citation28 To capture pain interference, youth completed the PROMIS Pain Interference scale (PROMIS-PI; Pediatric version),Citation27 an eight-item measure assessing the degree to which pain interfered with youths’ daily activities in the past 7 days.

Health-Related Quality of Life

Health-related quality of life was assessed with the widely used Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) Short Form measuring self-reported physical and psychosocial health in the preceding 7 days (Acute VersionCitation29). Youth indicate perceived difficulty in physical, school, social, and emotional health domains with responses indicated on a 5-point scale, ranging from never to almost always. The measure yields a total health score ranging from 1 to 100 (higher scores indicate better health-related quality of life).

Data Analysis Plan

Data analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). For our primary aim, we conducted descriptive statistics to examine indicators of program feasibility and participants’ quantitative ratings of program acceptability. Specifically, we computed the percentage of the available sample recruited and enrolled in the study as well as percentage completion of the four assessment time points and completion of survey measures. Treatment engagement was measured by the number of completed intervention lessons (out of six) as determined by REDCap usage data. We used our tracking database to compute the number of completed coaching calls for each adolescent and parent participant and calculated the proportion of the sample completing at least five calls.

Qualitative interviews were coded using semantic thematic analysis following the guidelines of Braun and Clarke.Citation30 The qualitative coding team was composed of a psychologist with experience in cognitive-behavioral therapy and pediatric pain management, a pain medicine physician with experience in working with youth undergoing major surgery including spine fusion, and an undergraduate student in psychology. Before initiating coding, the team reviewed the interview transcripts to become familiar with the data. Two primary coders created initial codes by organizing text into meaningful groups using NVivo v.10.Citation31 Next, the two coders worked together to group similar codes into subcategories and then the subcategories were grouped into overarching themes. At each stage of coding, the codes, categories, and themes were recorded in a codebook that included operational definitions and representative quotes. Using this codebook, the coders worked together to achieve consensus. When there was disagreement, a third study team member arbitrated. Using this process, 100% agreement was achieved at each stage of coding.

Sample Size

Because this was a pilot study, a sample size calculation was not performed. Consulting guidelines for pilot studiesCitation32,Citation33 a sample size of 13 adolescent–parent dyads (n = 26) was deemed adequate to provide information on feasibility and acceptability.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the sample are summarized in . Participants included 13 adolescent–parent dyads. Adolescents were between the ages of 12 and 17 years (M = 14.3, SD = 1.4) and predominantly female (69.2%) and white (69.2%). At baseline (prior to the surgery or intervention), adolescents reported mild pain intensity (M = 3.00, SD = 0.41). PROMIS-derived T-scores indicated adolescents reported slightly elevated pain interference (M = 54.3, SD = 7.8), with around one-fourth (23.1%) reporting pain interference levels 1 SD above the mean (i.e., a T-score of ≥60). Moreover, 38.1% (n = 5) reported significant impairments in health-related quality of life (i.e., total score on PedsQL <74.9).

Table 2. Sample baseline characteristics (n = 13 parent–adolescent dyads).

Feasibility

Recruitment and Enrollment Rate

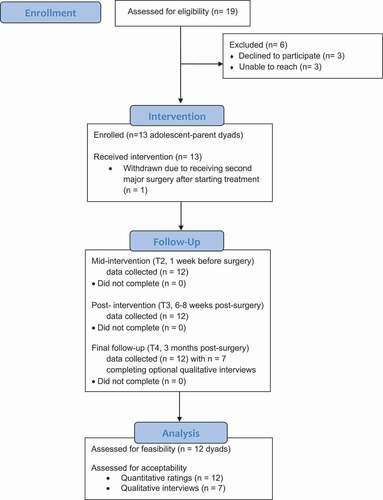

shows a CONSORT (Consolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials) diagram depicting the flow of study participants and summarizing recruitment and engagement at each step of this pilot feasibility trial. Study staff identified 19 potentially eligible families via surgery schedules and electronic medical records of adolescents. The research staff was unable to reach 3 of the potentially eligible families. Of the 16 potential families who were reached, all met inclusion criteria and were invited to participate. Three families declined participation, with reasons including lack of interest (n = 2) and lack of time (n = 1). The remaining 13 families or parent–adolescent dyads (n = 26) enrolled in the study (overall recruitment/enrollment rate = 68.4%; enrollment rate among those approached = 81.2%). Thus, we exceeded our first indicator of feasibility based on our recruitment rate metric of at least 50%.

Intervention Engagement and Adherence

Engagement in the online intervention program was excellent, with all 13 adolescent–parent dyads (100%) completing all three lessons of both the adolescent and parent preoperative intervention phase. One family was withdrawn from the study before completing the second postoperative phase of the intervention due to the adolescent needing to undergo an unanticipated second surgery (reoperation of the spine). Of the remaining 12 dyads, 100% completed all three lessons of the postoperative intervention phase. During the intervention, 91.7% of adolescents (n = 11/12) and 83.3% of parents (n = 10/12) completed at least five out of six telephone coaching calls (adolescents: M = 5.3, SD = 1.4, range = 1–6; parents: M = 5.2, SD = 1.5, range = 1–6). Thus, we met our second metric for feasibility based on our treatment engagement exceeding a 75% completion rate for lessons and coaching calls.

Assessment Completion

Assessment completion was excellent (see CONSORT diagram). All 13 (100%) enrolled dyads completed their baseline (T1, 4–8 weeks before surgery) and second assessments (T2, 1 week before surgery). As described above, one family was withdrawn from the study prior to the postoperative intervention phase. Of the remaining 12 dyads, 100% completed the third (T3, postintervention/6–8 weeks postsurgery) and fourth (T4, 3-month follow-up/postsurgery) follow-up assessments. Thus, we exceeded our third feasibility metric of at least 80% for retention of the sample and assessment completion.

Intervention Acceptability

Quantitative Feedback

Overall, adolescents and parents rated the intervention to be acceptable. The mean item-level scores on the program evaluation survey ranged from 3.2 to 4.9 for the presurgical program and from 3.0 to 4.6 for the postsurgical program, corresponding to moderate to high ratings of acceptability on average (see ; item range 0−5).

Table 3. Program evaluation: Quantitative ratings on intervention acceptability.

Qualitative Feedback

As shown in , ten themes emerged that describe participants’ experiences using the psychosocial intervention. Identified themes were organized into the following topic areas for reporting purposes: (1) intervention components (i.e., lesson/skills), (2) general program structure, and (3) suggestions for improvement.

Table 4. Program evaluation: Qualitative feedback on intervention acceptability.

Five themes emerged highlighting the helpfulness and perceived benefit of the program’s delivery of several treatment components/skills, specifically: (1) cognitive and relaxation skills helped adolescents and parents cope with stress, (2) cognitive and relaxation skills helped adolescents cope with pain during recovery (3), strategies for improving sleep were beneficial both before surgery and during recovery, (4) activity pacing and goal-setting were used to gradually return to regular activities, and (5) parents valued strategies to encourage self-care. Two themes related to the perceived helpfulness of the general structure of the program were identified: (1) families found narratives relatable and validating and (2) families appreciated the flexibility of the online program. Though feedback was highly positive overall, participants provided suggestions for improvement with the most consistent feedback related to (1) rethinking timing and reducing the length of the first postoperative lesson, (2) reducing repetitive lesson content, and (3) enhancing program accessibility and interactivity.

Adverse Events

No adverse events were spontaneously reported during the study. As noted above, one adolescent participant needed to undergo major second surgery during the study period and thus the family was subsequently withdrawn from the study but allowed access to the intervention.

Discussion

The goal of this pilot study was to examine the feasibility and acceptability of an Internet-based perioperative psychosocial treatment program to reduce acute and chronic postoperative pain among adolescents undergoing major surgery. Our findings confirmed feasibility across several metrics, including adequate recruitment and retention rates, high treatment engagement, and excellent assessment completion and retention. These data demonstrate our ability to effectively recruit patients and deliver an intervention program during both the preoperative and postoperative phases, a highly demanding time for families. Moreover, the intervention program was well received by adolescents and parents according to quantitative ratings and qualitative feedback. Families highlighted numerous strengths of the program as well as notable areas for improvement.

To our knowledge, this is the first pilot feasibility study of an Internet-delivered psychosocial intervention for adolescents undergoing major surgery. Despite the known risk for developing persistent postsurgical pain (CPSPCitation7,Citation34), very few perioperative psychosocial interventions have been evaluated in this population, and none have been delivered remotely via the Internet.Citation17 There are programs delivered through smartphone applications to provide pain management strategies to adolescents focused on reducing acute postoperative pain,Citation35 although program outcome data have not been published. Our intervention program is unique in targeting a broader range of known risk factors for the transition from acute to chronic pain, including adolescent and parent anxiety and sleep disturbance. The development of a flexible, accessible, and low-cost intervention delivered via remote technology to adolescents undergoing major surgery has the unique potential for widespread dissemination and broad reach, overcoming significant barriers related to access and family burden of in-person psychosocial interventions. Additional strengths of this pilot study include the development of both adolescent and parent versions of the intervention program, implementation during the preoperative and postoperative periods, and the use of quantitative and qualitative metrics to evaluate intervention acceptability.

Despite several strengths, this study also carries notable limitations. A single-arm pilot design was chosen to prioritize the evaluation of feasibility and acceptability, as is appropriate for research on newly developed interventions.Citation36 However, this study design and the small sample size do not allow for an evaluation of treatment efficacy. The lack of a control group further limits the ability to determine the feasibility of randomization. We did not include a longer-term follow-up assessment and thus could not evaluate retention rate beyond 3 months. Moreover, five adolescent–parent dyads (42% of the sample) did not participate in the optional qualitative interview portion of the study. Finally, the majority of the sample comprised white females who underwent a single type of surgery at a single medical center in the northwestern United States. Although the sample demographics are representative of youth undergoing surgery,Citation37 findings may not generalize to a more diverse population or those undergoing other types of major surgeries. Future studies will be needed to ensure that intervention engagement and acceptability remains high in more racially and socioeconomically diverse samples.

Given findings highlighting the feasibility and acceptability of this Internet-delivered psychological intervention program, an important next step is to evaluate the efficacy of the intervention in a full-scale randomized controlled trial. Indeed, given the favorable feasibility outcomes, we revised intervention components and developed a fully functional smartphone application and website to deliver the intervention in a multisite, fully powered randomized controlled trial (NCT04637802, ClinicalTrials.gov). For further details and trial protocol, please see Rabbitts et al.Citation38 The larger trial uses a 2 × 2 factorial design to separately evaluate the two intervention phases (preoperative and postoperative) in order to expand understanding of the optimal timing of intervention delivery. Moreover, the trial uses an active comparator as a control: a psychoeducational program that provides information to families about preparation for and recovery from surgery but does not include direct training in cognitive-behavioral strategies. No major changes were made to the eligibility criteria or study intervention length; however, the final follow-up assessment was extended to 6 months to understand the durability of intervention effects in preventing the transition from acute to chronic pain.

Based on qualitative feedback from families, we made several modifications to enhance program features and delivery while maintaining the core intervention content. Most notable, the original program (previously delivered through REDCap) was transformed to be delivered via a mobile app for adolescents and a website for parents (called SurgeryPal), thus enhancing intervention accessibility and flexibility. We also reduced the length of the lessons and included several interactive features, including guided skill practice; symptom tracking, which triggers personalized “For You” content; and multimedia components (e.g., videos of parents and adolescents describing experiences and use of skills). Coaching calls were removed from the protocol to improve intervention scalability; instead, features unique to digital health platforms such as personalized notifications were included to encourage skill use and program completion. Moreover, based on participant feedback, we amended the delivery timing of the first postsurgical lesson from 1 week to 3 weeks after surgery to reduce participant burden during the immediate recovery period. For a more detailed description of the SurgeryPal app and website, see Rabbitts et al.Citation38

There is an urgent need for effective and accessible psychosocial interventions for adolescents undergoing major surgery. The current study presents the first evaluation of a promising online psychosocial intervention delivered during the perioperative period to adolescents undergoing major surgery and their parents. Preliminary evidence demonstrates the high feasibility and acceptability of the intervention. The program’s content and online format were well received by families, and participant feedback was used to modify intervention elements and create an interactive digital health mobile app (for adolescents) and website (for parents) for the fully powered randomized controlled trial. Completion of the larger trial will be a crucial next step in understanding whether the SurgeryPal program effectively prevents CPSP and improves longer-term health outcomes among youth, with the potential for widespread integration into perioperative care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the adolescent and parent participants who enrolled in this study for their dedication to pain research. The authors acknowledge Kristen Daniels for her assistance with database preparation and analyses.

Disclosure of Interest

Caitlin B. Murray does not have any conflicts of interest. Anthea Bartlett does not have any conflicts of interest. Alagumeena Meyyappan does not have any conflicts of interest. Tonya M. Palermo does not have any conflicts of interest. Rachel Aaron does not have any conflicts of interest. Jennifer Rabbitts does not have any conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Rabbitts JA, Groenewald CB, Tai GG, Palermo TM. Presurgical psychosocial predictors of acute postsurgical pain and quality of life in children undergoing major surgery. J Pain. 2015;16:226–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2014.11.015.

- Pagé MG, Stinson J, Campbell F, Isaac L, Katz J. Pain-related psychological correlates of pediatric acute post-surgical pain. J Pain Res. 2012;5:547. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S36614.

- Connelly M, Fulmer RD, Prohaska J, Anson L, Dryer L, Thomas V, Ariagno JE, Price N, Schwend R. Predictors of postoperative pain trajectories in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2014;39(3):E174–E181. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000000099.

- Voepel-Lewis T, Caird MS, Tait AR, Malviya S, Farley FA, Li Y, Abbott Md, van Veen T, Hassett AL, Clauw DJ. A high preoperative pain and symptom profile predicts worse pain outcomes for children after spine fusion surgery. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(5):1594–602. doi:https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000001963.

- Bailey KM, Howard JJ, El-Hawary R, Chorney J. Pain trajectories following adolescent idiopathic scoliosis correction: analysis of predictors and functional outcomes. JBJS Open Access. 2021;6(2):e20.00122. doi:https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.OA.20.00122.

- Ferland CE, Parent AJ, Saran N, Ingelmo PM, Lacasse A, Marchand S, Sarret P, Ouellet JA. Preoperative norepinephrine levels in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma correlate with pain intensity after pediatric spine surgery. Spine Deformity. 2017;5(5):325–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jspd.2017.03.012.

- Rabbitts JA, Fisher E, Rosenbloom BN, Palermo TM. Prevalence and predictors of chronic postsurgical pain in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2017;18(6):605–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2017.03.007.

- Chidambaran V, Ding L, Moore DL, Spruance K, Cudilo EM, Pilipenko V, Hossain M, Sturm P, Kashikar-Zuck S, Martin LJ. Predicting the pain continuum after adolescent idiopathic scoliosis surgery: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Pain. 2017;21(7):1252–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1025.

- Julien-Marsollier F, David R, Hilly J, Brasher C, Michelet D, Dahmani S. Predictors of chronic neuropathic pain after scoliosis surgery in children. Scand J Pain. 2017;17(1):339–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2017.09.002.

- Rosenbloom BN, Pagé MG, Isaac L, Campbell F, Stinson JN, Wright JG, Katz J. Pediatric chronic postsurgical pain and functional disability: a prospective study of risk factors up to one year after major surgery. J Pain Res. 2019;12:3079. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S210594.

- Williams G, Howard RF, Liossi C. Persistent postsurgical pain in children and young people: prediction, prevention, and management. Pain Rep. 2017;2(5):e616. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/PR9.0000000000000616.

- Pagé MG, Stinson J, Campbell F, Isaac L, Katz J. Identification of pain-related psychological risk factors for the development and maintenance of pediatric chronic postsurgical pain. J Pain Res. 2013;6:167. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S40846.

- Rabbitts JA, Palermo TM, Zhou C, Meyyappan A, Chen L. Psychosocial predictors of acute and chronic pain in adolescents undergoing major musculoskeletal surgery. J Pain. 2020;21(11–12):1236–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2020.02.004.

- Ocay DD, Li MMJ, Ingelmo P, Ouellet JA, Pagé MG, Ferland CE. Predicting acute postoperative pain trajectories and long-term outcomes of adolescents after spinal fusion surgery. Pain Res Manage. 2020;2020:1–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/9874739.

- Rabbitts JA, Palermo TM, Lang EA. A conceptual model of biopsychosocial mechanisms of transition from acute to chronic postsurgical pain in children and adolescents. J Pain Res. 2020;13:3071. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S239320.

- Werner MU, Kongsgaard UE.Defining persistent post-surgical pain: is an update required? BJA: British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2014;113(1):1–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aeu012 .

- Davidson F, Snow S, Hayden JA, Chorney J. Psychological interventions in managing postoperative pain in children: a systematic review. Pain. 2016;157(9):1872–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000636.

- Rabbitts JA, Kain Z. Perioperative care for adolescents undergoing major surgery: a biopsychosocial conceptual framework. Anesth Analg. 2019;129(4):1181–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000004048.

- Rabbitts JA, Aaron RV, Fisher E, Lang EA, Bridgwater C, Tai GG, Palermo TM. Long-term pain and recovery after major pediatric surgery: a qualitative study with teens, parents, and perioperative care providers. J Pain. 2017;18(7):778–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2017.02.423.

- Lau N, Waldbaum S, Parigoris R, O’Daffer A, Walsh C, Colt SF, Yi-Frazier JP, Palermo TM, McCauley E, Rosenberg AR. eHealth and mHealth psychosocial interventions for youths with chronic illnesses: systematic review. JMIR Pediatr Parenting. 2020;3(2):e22329. doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/22329.

- Fisher E, Law E, Dudeney J, Eccleston C, Palermo TM. Psychological therapies (remotely delivered) for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011118.pub3.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010.

- Spielberger, CD. Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory for children. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1973.

- Essner B, Noel M, Myrvik M, Palermo T. Examination of the factor structure of the Adolescent Sleep–Wake Scale (ASWS). Behav Sleep Med. 2015;13(4):296–307. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2014.896253.

- Reid GJ, Gilbert CA, McGrath PJ. The pain coping questionnaire: preliminary validation. Pain. 1998;76(1):83–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00029-3.

- Franke GH, Jaeger S, Glaesmer H, Barkmann C, Petrowski K, Braehler E. Psychometric analysis of the brief symptom inventory 18 (BSI-18) in a representative German sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17(1):1–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0283-3.

- Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, Amtmann D, Bode R, Buysse D, Choi S. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011.

- Mara CA, Kashikar-Zuck S, Cunningham N, Goldschneider KR, Huang B, Dampier C, Sherry DD, Crosby L, Farrell Miller J, Barnett K, et al. Development and psychometric evaluation of the PROMIS pediatric pain intensity measure in children and adolescents with chronic pain. J Pain. 2021;22(1):48–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2020.04.001.

- Chan KS, Mangione-Smith R, Burwinkle TM, Rosen M, Varni JW. The PedsQL™: reliability and validity of the short-form generic core scales and asthma module. Med Care. 2005;43(3):256–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200503000-00008.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Castleberry A. Pharmacy students’ ability to think about thinking. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(8). doi:https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe788148.

- Julious SA. Sample size of 12 per group rule of thumb for a pilot study. Pharm Stat. 2005;4(4):287–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pst.185.

- Birkett MA, Day SJ. Internal pilot studies for estimating sample size. Stat Med. 1994;13(23–24):2455–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.4780132309.

- Batoz H, Semjen F, Bordes-Demolis M, Bénard A, Nouette-Gaulain K. Chronic postsurgical pain in children: prevalence and risk factors. A prospective observational study. BJA. 2016;117(4):489–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aew260.

- Birnie KA, Campbell F, Nguyen C, Lalloo C, Tsimicalis A, Matava C, Cafazzo J, Stinson J. iCanCope PostOp: user-centered design of a smartphone-based app for self-management of postoperative pain in children and adolescents. JMIR Formative Res. 2019;3:e12028. doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/12028.

- Czajkowski SM, Powell LH, Adler N, Naar-King S, Reynolds KD, Hunter CM, Laraia B, Olster DH, Perna FM, Peterson JC, et al. From ideas to efficacy: the ORBIT model for developing behavioral treatments for chronic diseases. Health Psychol. 2015;34(10):971. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000161.

- Rabbitts JA, Groenewald CB. Epidemiology of pediatric surgery in the United States. Pediatr Anesth. 2020;30(10):1083–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.13993.

- Rabbitts JA, Zhou C, de la Vega R, Aalfs H, Murray CB, Palermo TM. A digital health peri-operative cognitive-behavioral intervention to prevent transition from acute to chronic postsurgical pain in adolescents undergoing spinal fusion (SurgeryPalTM): study protocol for a multisite randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2021;22:1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-021-05596-9.