ABSTRACT

Background

The Canadian Pain Task Force recently advanced an action plan calling for improved entry-level health professional pain education. However, there is little research to inform the collaboration and coordination across stakeholders that is needed for its implementation.

Aims

This article reports on the development of a stakeholder-generated strategic plan to improve pain education across all Canadian physiotherapy (PT) programs.

Methods

Participants included representatives from the following stakeholder groups: people living with pain (n = 1), PT students and recent graduates (n = 2), educators and directors from every Canadian PT program (n = 24), and leaders of Canada’s national PT professional association (n = 2). Strategic priorities were developed through three steps: (1) stakeholder-generated data were collected and analyzed, (2) a draft strategic plan was developed and refined, and (2) stakeholder endorsement of the final plan was assessed. The project was primarily implemented online between 2016 and 2018.

Results

The plan was developed through five iterative versions. Stakeholders unanimously endorsed a plan that included five priorities focusing on uptake of best evidence across (1) national PT governance groups and (2) within individual PT programs; (3) partnering with people living with pain in pain education; (4) advocacy for the PT role in pain management; and (5) advancing pain education research.

Conclusion

This plan is expected to help Canadian stakeholders work toward national improvements in PT pain education and to serve as a useful template for informing collaboration on entry-level pain education within other professions and across different geographic regions.

Introduction

Pain is a leading international cause of personal suffering, disability, and health care expenditure.Citation1,Citation2 The Canadian Pain Task Force recently completed a three-phase process that culminated in the publication of a National Action Plan that aims to address the challenge of pain in Canada.Citation3 This plan includes six overarching strategies, one of which focuses on improving how health providers are trained to understand, assess, and manage pain.Citation3 Past work shows that health professional pain education contributes to improved knowledge, attitudes, and management-related behavior.Citation4 Targeting pain education within entry-level education holds important long-term potential to facilitate population-level improvement in the health of people living with pain by helping to educate a new generation of health providers who are better able to provide evidence-based pain management.Citation5

Previous research has helped provide an important foundation for improving entry-level pain education. For instance, a set of core pain management competencies was developed to serve as high-level educational outcomes for interprofessional health education programs.Citation6 National and international surveys of entry-level health education programs have established the need for improving pain education by revealing an overall lack of curricula content and time dedicated to pain education across different professions programs, including medicine, nursing, and physiotherapy (PT).Citation7–12 Other work has created pragmatic guidelines and reported on exemplar programs illustrating how pain management competencies can be integrated within individual health professions programs.Citation13–16

However, an important challenge that remains underaddressed within the pain education literature includes potential avenues for facilitating collaboration across the different stakeholders within health professions. Within each profession there are multiple and diverse stakeholders that are directly or indirectly involved and/or invested in pain education. For instance, clinical educators and students are directly involved in pain-related teaching and learning and may be influenced by important upstream and downstream stakeholders. In this context, people living with pain can be considered downstream stakeholders because they may receive treatment from newly trained clinicians but are not always positioned to influence how clinical students learn about pain. Immediately upstream to pain educators are program administrators who coordinate curricula and who are well positioned to influence the curricula and resources available for pain education. Further upstream are stakeholders that help govern the profession and regulate professional education. These include the regulators that set standards for entry-to-practice licensure and accreditation of health education programs as well as professional associations that advocate on behalf of the profession. Though each of these stakeholders is invested in pain education, there is very little research that addresses how these groups might approach the coordination required to achieve the type of population-level change that is called for within the national pain strategy.

Our group has recently started to work toward this goal within the context of Canadian entry-level PT programs. Physiotherapists (PTs) are vital primary health care providers in the context of pain, and their expertise focuses on nonpharmacological management, which has been specifically called for within the National Action Plan. Our previous work has shown that, similar to other health education programs across other regions, there are major discrepancies in how pain management competencies are integrated across Canadian PT training programs. Our recent national survey of all Canadian PT entry-level programs revealed an eightfold difference in the amount of time dedicated to pain education across programs (ranging from 8 to 65 h).Citation10 Moreover, the overall mean time allocated to pain education across Canadian programs (24.9 h) was lower than the mean time reported across PT programs in both the United States (31 h) and the United Kingdom (37.5 h).Citation9–11

In 2016, our group convened a national stakeholder workshop that aimed to facilitate stakeholder collaboration in improving PT pain education across the country. We recently reported on this workshop,Citation17 which established stakeholder consensus on the need to improve PT pain education across Canada, and began to explore the barriers, facilitators, and preliminary strategies that influence how stakeholders might work together to achieve this improvement. This initial workshop was intended to lay the foundation for subsequent work with the same stakeholders to develop a national strategic plan for improving pain education.Citation17 The purpose of the current article is to report on the development process of this strategic plan and its outcome. The broader goal of this reporting is to help generate a literature base that can be used to inform how stakeholders in other health professions and/or located within other geographic regions might approach strategic planning and collaborative efforts to improve how pain education is integrated across their entry-level training programs.

Methods

Methodological Approach and Theoretical Framework

The project used a stakeholder-centered, integrated knowledge translation approach that sought to improve health outcomes by involving all relevant stakeholders throughout the research process.Citation18–20 In the context of this work, stakeholders related to PT pain education were integrated within the research team. Consistent with our previous national stakeholder workshop,Citation17 the Knowledge To Action (KTA) framework was used to inform this work. Briefly, the KTA framework is designed to describe and inform how knowledge is created and translated into practice.Citation21,Citation22 The KTA describes a seven-step action cycle that characterizes the process related to knowledge translation. Step 4 of the action cycle addresses the selection, tailoring, and implementation of knowledge translation interventions. This work was broadly anchored within this step of the action cycle because the overarching purpose of the strategic plan was to serve as a foundation for guiding stakeholders in the development and implementation of specific knowledge translation interventions to improve entry-level pain education. This study was approved by Research Ethics Board of McGill University’s Faculty of Medicine (A11-B56-15B), and all participants provided verbal informed consent during the audio-recorded interviews. Participants who attended the initial in-person workshop also provided written informed consent.

Participants

provides an overview of the participants who were involved in developing and approving the strategic plan. Participants represented stakeholder groups including people living with pain, PT students and recent graduates, PT pain educators, PT program directors, and leaders associated with the national PT professional association. Individual participants were invited based on their ability to represent national stakeholder groups. Two stakeholder groups were invited but declined to participate in the development of the strategic plan. These included the national accreditor for Canadian PT programs (Physiotherapy Education Accreditation Canada) and the national organization that coordinates PT regulators across the country (The Canadian Alliance of Physiotherapy Regulators). These stakeholders abstained due to their concern for a potential conflict of interest in relation to their roles within the profession as autonomous evaluators; these same stakeholder groups also abstained from endorsing the previously reported consensus statement related to this initiative.Citation17 These groups represent two of the four stakeholder groups that form the National Physiotherapy Advisory Group (NPAG) that governs the PT profession in Canada; the other two NPAG members (The Canadian Council of Physiotherapy University Programs and The Canadian Physiotherapy Association) participated in the present work, as well as our previous research in this area.Citation17

Table 1. Description of stakeholders that participated in the strategic plan development

Consistent with an integrated knowledge translation approach, the authors of this article included members of the PT pain educator (G.B., L.C., J.H., J.M., K.P., D.W., T.W.) and PT program director (B.S., Y.T.L.) stakeholder groups, as well as knowledge translation researchers without direct affiliation with these groups (A.B., A.T.). The lead research team members (A.B., G.B., J.M., A.T., Y.T.L., D.W., T.W.) identified potential participants who were outside of the authorship group, and the lead author (T.W.) invited them to participate. PT pain educators were associated with a previously established national network of pain educators that included representation from each of the PT programs in Canada and helped initiate this line of research.Citation17 The lead author presented the project to The Canadian Council of Physiotherapy University Programs and invited all PT directors to participate. The Canadian Physiotherapy Association and their affiliated National Student Assembly had previously been connected to this line of work. The lead author invited representatives from these organizations to participate in this project.Citation17 Similarly, the participant who was representing people living with pain had been previously involved in related research activities and was invited by the lead author to continue to participate in this project.

Procedure

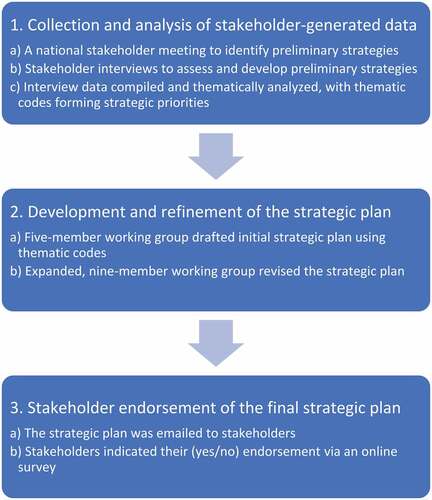

The final stakeholder-endorsed strategic plan was developed through three sequential steps (depicted in ): (1) Stakeholder-generated data were collected and analyzed. (2) A draft strategic plan was developed and refined, based on stakeholder input. (3) Stakeholder endorsement of the final strategic plan was assessed. Step 1 was initiated in 2016 and Step 3 was completed in 2018. Aside from an initial in-person workshop that was held in Montreal, all other collaborative aspects of the project were implemented online or over the phone.

Collection and Analysis of Stakeholder-related Data

Data were collected through two phases (i.e., 1a and 2b from ) and analyzed through a third phase (). The first phase () was previously reported and consisted of a national stakeholder meeting to build consensus on the importance of pain education and to identify barriers, opportunities, and strategies for improving PT pain education across the country.Citation17 The second phase () consisted of subsequent stakeholder interviews. Appendix A includes an overview of how strategic priorities evolved over the course of strategic plan development. Strategies that emerged from the national stakeholder workshop are listed under the heading of “Version 1” within Appendix A. To summarize, these strategies included integrating International Association for the Study of Pain competencies within national standards and regulatory policy, encouraging the development of best teaching practices among PT pain educators across the country, partnering with people living with pain, building increased awareness of the need to improve pain education, and setting clear goals and outcomes to guide national collaboration on improved PT pain education.

Stakeholder interviews () were used to assess support and further develop these workshop-generated strategies. An interview guide was developed by three members of the authorship team (G.B., J.M., T.W.). It was initially piloted with two other team members (Y.T.L., D.W.) and determined to be functioning as expected. This interview guide is described in Appendix B. To summarize, interview questions focused on evaluating stakeholder perceptions of the workshop-generated strategies, including suggestions for amendments, relevance of strategies to stakeholder priorities, and barriers and facilitators related to implementation. All stakeholders described in were invited to participate in an interview and were sent the interview guide. All interviews were conducted with individual stakeholder representatives, with the exception of one group interview with four members of The Canadian Council of Physiotherapy University Programs. This group interview was suggested by council members to increase the feasibility of integrating multiple perspectives from this national committee. Interviews were designed to last approximately 1.5 h. All interviews were audio-recorded and were administered either over the phone or online using video conference software (Zoom).

Interviews were administered by three members of the research team (G.B., J.M., T.W.), with two team members involved in each interview. One team member led the interview, and both team members took field notes on the content of the conversation. Following the interviews, both team members examined each other’s notes to ensure their alignment with the content of the interview and that no key ideas were missed. An interviewer not involved in the interview reviewed the audio recordings and field notes to resolve any discrepancies.

Interview data were compiled and thematically analyzed () following qualitative description.Citation23 Qualitative description is rooted in subjectivism and seeks to understand a phenomenon, a process, or the perspectives and worldviews of participants.Citation24 Qualitative description aligned with our data analytic goals of providing a rich and literal description of participants’ perspectives, while striving to adhere to the verbatim data as closely as possible.Citation23 Other common qualitative methodologies were not well aligned with the goals of this study, because they do not aim to address culture (ethnography), lived experience (phenomenology), or theory building (grounded theory).Citation25 Data were analyzed using a combination of deductive and inductive coding. First, a coding framework was created based on the five workshop-generated strategies. Data were then categorized into each of these themes. In addition, data that did not fit within the five workshop-generated strategies were analyzed separately to determine whether new themes emerged. The members of the three-member interview team each independently reviewed the interview notes to identify and thematically code all content that related to the previously identified strategies for improving PT pain education and content unrelated to the a priori identified strategies. Pairs of reviewers then compared their codes and discussed discrepancies. A third member of the research team was consulted if any discrepancies could not be resolved. The three-member interview team met frequently throughout the analysis process to participate in reflexive dialogue.Citation26,Citation27 Once all interview data were analyzed, these thematic codes were used as the basis of the strategic plan. The strategic priorities associated with these codes are listed as Version 2 in Appendix A.

Development and Refinement of the Draft Strategic Plan

A five-member working group () was formed to draft the initial strategic plan (G.B., J.M., Y.T.L., D.W., T.W.). Strategic priorities were based on thematic codes. The intended goal was to draft strategic priorities that would provide stakeholders with high-level direction for improving PT pain education yet be sufficiently flexible to support stakeholder autonomy and engagement. Once the initial strategic plan was drafted, it was emailed to all stakeholders for feedback and suggestions for improvement. Stakeholders were also invited to join the working group to directly participate in further refining the strategic plan. Four additional stakeholders (L.C., J.H., K.P., B.S.) responded to this invitation and joined the expanded, nine-member working group (, 2b). Stakeholders shared their feedback either via email, phone conversation, or video chat (Zoom). Feedback was compiled in a shared online document (Google Doc) that was accessible to all working group members. Working group members met regularly via video conference (Zoom) to discuss and integrate this feedback. Once all working group members were satisfied with the strategic plan, it was emailed to each of the participating stakeholders for endorsement (, 3a).

Assessment of Stakeholder Endorsement of the Final Strategic Plan

A single-item online survey question was used to assess stakeholder endorsement of the strategic plan (, 3b); participants could indicate whether they supported or did not support the strategic plan or whether they abstained. The lead author oversaw the voting process and emailed the online survey to all stakeholders listed in . Voting took place between June 8 and September 12, 2018. Each of the participating stakeholders representing people living with pain, PT students and recent graduates, PT pain educators, and the national PT professional association independently casted their vote for the strategic plan. Members of the Canadian Council of Physiotherapy University Programs considered the plan during a regularly scheduled committee meeting and cast their votes in the context of this meeting.

Results

Participation in Stakeholder Interviews

A total of 14 stakeholders were interviewed. This included all of the participating stakeholders representing people living with pain, PT students and recent graduates, and the national PT professional association (as described in ). This also included three representatives of PT pain educators and six representatives of PT program directors from across the country (four of these representatives were interviewed together in one group interview).

Strategic Plan Development

Appendix A shows how the five strategies from the Pain Education in Physiotherapy workshop evolved into the final priorities included in the final stakeholder-endorsed strategic plan. Each strategic priority went through multiple iterative versions before being finalized; these are presented in . To summarize, key changes relating to strategic priority 1 included modifying the strategy to ensure sufficient autonomy of NPAG members by being less prescriptive about what content should be included within national governance documents. Key changes relating to strategic priority 2 included being more prescriptive about the competencies that PT pain educators identified as being important for their teaching; educators indicated their support for targeting the interprofessional core competencies that are integrated within the PT curriculum guidelines of the International Association for the Study of Pain.Citation6 Key changes relating to strategic priority 3 included adding further specificity regarding how and why partnerships with people living with pain should be developed. Key changes relating to strategic priority 4 included expanding the targets of advocacy work to stakeholders outside of the PT profession. Key changes relating to strategic priority 5 included expanding the scope of this priority to include the advancement of research addressing pain education.

Table 2. Number of iterative versions involved in the development of each strategic priority

Voting Outcome and Finalized Strategic Plan

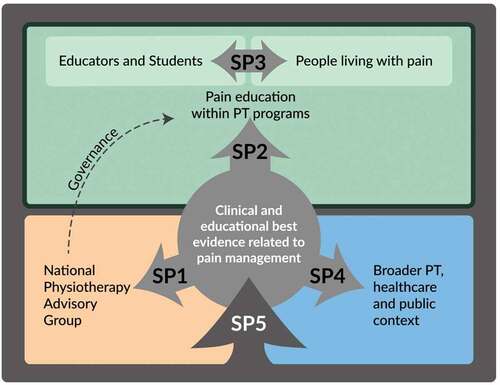

All stakeholder representatives unanimously voted to endorse the strategic plan. The final stakeholder-endorsed version of the strategic plan is presented in . aims to visually depict each of the priorities included in the strategic plan.

Figure 2. Strategic priorities (SP) included in the Pain Education in Physiotherapy Strategic Plan. SP1 supports stakeholder groups that govern the physiotherapy (PT) profession in Canada (i.e. National Physiotherapy Advisory Group members) by identifying and addressing best evidence related to pain education. SP2 integrates evidence-based pain management competencies and encourages best educational practices within individual physiotherapy programs. SP3 supports partnerships with people living with pain in planning and implementing educational strategies. SP4 promotes evidence-based advocacy regarding the value of PTs in effective pain management. SP5 promotes research and evaluation in relation to pain education and strategic plan implementation.

Discussion

This article describes a consensus-building approach involving multiple stakeholders in the development of a national strategic plan for improving pain education across entry-level PT programs in Canada. Our collaborative approach integrated a wide range of stakeholders, with representation of people living with pain, PT students and recent graduates, as well as PT educators, PT program directors, and national PT leaders. The development of this national strategic plan provides a novel contribution to the literature on pain education in the health professions by illustrating how collaboration can be achieved across such a diverse group of stakeholders. The first strategic priority focuses on supporting stakeholder groups that govern the PT profession in Canada (i.e. NPAG members) by identifying and addressing best evidence related to PT pain management. The International Association for the Study of Pain provides an important synthesis of this evidence and makes recommendations for inclusion within entry-level PT education.Citation28 The NPAG was a critically important partner in developing this strategic priority, because this entity is responsible for the national curriculum guidelines, accreditation, and licensing standards for PTs across Canada. One goal in generating this strategic priority was to ensure support for the autonomy of NPAG members in how they governed the profession. portrays this relationship using an indirect arrow; though NPAG members are actively supported, their governance decisions are not directly within the scope of this strategic priority. Interestingly, NPAG members had different interpretations of how this autonomy should influence their participation in this work. The two NPAG members that are more directly involved in regulation and accreditation opted to not participate in this process, whereas the two members that were involved in leadership and promotion of the PT programs and the profession did participate. This may result in increased opportunities for working with NPAG members to integrate best evidence within curriculum guidelines, while potentially introducing barriers to integrating similar evidence within accreditation standards and entry-to-practice examinations. Other work in the area of U.S. medical education suggests similar challenges in integrating best evidence within their entry-to-practice examinations.Citation29 It is likely that full integration of regulatory stakeholders will be a common challenge across professions and regions.

The second strategic priority brings the focus of implementing evidence-based pain education to the level of the educators themselves and prioritizes sharing of best practices, resources, barriers, and facilitators to ensuring that all physiotherapy trainees are exposed to similarly high-quality pain education.Citation30,Citation31 This priority is aligned with the goals of previous work that aims to illustrate and model how best evidence can be integrated within individual entry-level PT programs.Citation13,Citation14 The priority extends this work by pointing to how collaboration might occur to facilitate these types of changes across institutions. The context of PT education in Canada may make this priority more achievable than other, more populous, countries. For instance, Canada has a relatively small number of university-based professional PT training programs (e.g. approximately 5% of the 250 accredited programs in the United States) and the director and lead pain educator associated with each of these programs endorsed this strategic plan. As a result, meaningful and transformative engagement with all training programs in Canada is likely an achievable goal. This makes Canada a very attractive context for novel and innovative education initiatives.

The third strategic priority endorses the collaborative participation of people in pain in co-designing pain education curricula and building educational strategies that place the patient at the center of effective clinical care. Specifically, this strategy aims to avoid tokenism of people living with pain by placing them on an equal level with educators and future clinicians. One challenge in implementing this plan will be to develop a pragmatic and feasible model for guiding these relationships. The Patients as Partners framework may serve as a useful template that could be adapted to the context specific needs of PT pain education.Citation32 Equitable engagement will also require adequate financial resources to support the work done by these partners, something that has been identified as a barrier in prior patient-partnered initiatives,Citation33 further emphasizing the need for sustainable funding to ensure successful implementation of the plan.

The fourth priority emphasizes advocacy, both within and outside of the PT profession, around the potential added value of PTs in effective pain management. Recent work in this area has highlighted the multilevel nature of the barriers and facilitators related to uptake of evidence-based approaches pain management.Citation34 Within the PT context, the emphasis has primarily focused on advocating for improved pain management in the context of the ongoing opioid crisis. For instance, in 2017 the American and Canadian PT associations issued a joint statement that advocated for increasing the PT role within the nonpharmacological management of pain in an effort to combat the opioid epidemic.Citation35 Yet, despite this and related work, there are still important barriers within and outside the profession that may limit these efforts. For instance, PTs often report low levels of confidence in managing patients with complex forms of chronic pain,Citation36–39 and patients seeking care report important barriers to engaging in nonpharmacological treatments, such as restricted access or funding, reduced motivation for self-management, and limited perceived efficacy of these interventions.Citation40 These provider and patient barriers may have an interactive effect that further limits the availability and use of effective nonpharmacological management options. Future research in this area should explore the role that improved entry-level education may play in mitigating these barriers.Citation41 For instance, enhanced professional education may help new graduates become stronger advocates for nonpharmacological management, which in turn may help limit some of the external barriers to care.

The fifth and final priority focuses on the importance of research and evaluation of the effectiveness of any new curriculum, education, or training strategies.Citation42 Evaluation is an important part of any rigorous implementation and/or knowledge translation strategy.Citation21,Citation22 It should be targeted to optimize valid capture of important domains. Conversation around this priority focused on strategies for evaluating student performance outcomes in relation to pain education interventions. Participants indicated an appetite for going beyond metrics of quantity or checkbox-type surveys of content toward focusing on true acquisition of clinical competencies. Miller’s competency framework may provide a valuable scaffolding around which to build curriculum and also a useful framework for evaluating outcomes.Citation43 Miller’s pyramid delineates four levels of competency assessment (Knows, Knows how, Shows how, Does). Consistent with the consensus statements established by stakeholders involved in this work,Citation17 student and clinical outcomes were deemed the most important outputs of this initiative. Thus, this framework facilitates the development of evaluation strategies to capture competency at each level of Miller’s pyramid, from standardized paper-based tests to observational practice evaluations and audits.

In addition to evaluating student-related pain education outcomes, this strategic priority encourages a more comprehensive approach to assessing the overarching implementation process related to this initiative. A multilevel implementation framework, such as the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research,Citation44 would be well suited for this task. Such a framework would enable in-depth consideration of factors related to a potential pain education intervention, as well as the participating stakeholders and their context. The recently expanded version of this framework could also be used to help structure the implementation, assessment, and reporting of project-related interventions.Citation45

Though the content and implementation of this strategic plan is tailored to a Canadian PT context, the integrated KT process that was utilized in this work is likely transferable to other contexts. We expect that including both upstream and downstream stakeholders will be a common asset in developing meaningful change across other geographic regions and professions. People living with pain, students and new graduates, and educators each provide unique and valuable insights into what change is needed, and engaging program administrators and national regulators is critical to facilitating implementation. With this type of stakeholder engagement, the reported process could likely be tailored to fit the idiosyncratic needs of other training programs in different regions and across different professions.

Readers are encouraged to also consider some of the limitations related to this work. For instance, this project had a PT-centric focus that did not include other health professions. This approach corresponds to our central objective of developing a strategic plan that targets change within the PT profession and will likely contribute to an increased sense of professional ownership and engagement with this initiative moving forward. However, engagement with other health professionals—particularly those who hold influence within this field of work—is crucial to implementing pain education and to the advocacy work outlined in strategic priority 4; clearly, this will be an essential aspect of future work in this area. Furthermore, though this work builds on other consensus-based initiatives related to pain education by including often overlooked stakeholders (such as people living with pain and health professional students), it could be improved by further integrating participants from other marginalized groups in an effort to maximize equity, diversity, and inclusiveness. Lastly, one inherent vulnerability of using a stakeholder-based approach to develop a national strategic plan is that there remains ambiguity in who will “take charge” of the implementation and oversight of the plan. Though the authors of this article are committed to continuing to lead, facilitate, and coordinate this work, the ultimate success of this plan will be a function of continued stakeholder engagement and involvement.

Conclusion

In summary, a national stakeholder-generated strategic plan was developed for improving pain education across Canadian PT programs. This plan focuses on uptake of best evidence across national governance and within individual PT programs, partnership with people living with pain, advocacy for the PT role in pain management, as well as increased research, evaluation, and reporting on advancements in this domain. This process and outcome may serve a useful template to facilitate improved pain education across other professions and geographic regions.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed written and verbal consent to participate in this project was obtained prior to the start of this study. Ethics approval number: A11-B56-15B.

Disclosure statement

Timothy H. Wideman has received financial compensation for providing continuing education training on pain management for health professionals.

David M. Walton has previously provided paid continuing professional development sessions for clinicians working in pain management, provides third-party consultation, and has a small stake in a pain evaluation startup company (Actic AI Inc.) in London, Ontario; is co-holder of a Canadian patent for a panel of blood markers intended for use in chronic pain risk and prognosis screening; and either currently or within the past 5 years has received grant funding from arm’s-length public funders, including the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation, the Canadian Pain Society, the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, and the Canadian Pain Network/Chronic Pain Centre of Excellence; all such relationships existed prior to undertaking the current project and/or will not be affected by the results described herein.

Lisa Carlesso has received honoraria from EPA Health and the Canadian Orthopaedic Foundation.

All other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Goldberg DS, McGee SJ. Pain as a global public health priority. BMC Public Health. 2011;770(11).

- Rice AS, Smith BH, Blyth FM. Pain and the global burden of disease. Pain. 2016;157(4):791 796. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000454.

- Canada H. An action plan for pain in Canada. Ottawa (ON); 2021. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/corporate/about-health-canada/publicengagement/external-advisory-bodies/canadian-pain-task-force/report-2021-rapport/reportrapport-2021-eng.pdf

- Mankelow J, Ryan C, Taylor P, Atkinson G, Martin D. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of biopsychosocial pain education upon health care professional pain attitudes, knowledge, behavior and patient outcomes. J Pain. 2022;23(1):1–24. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2021.06.010.

- National Institutes of Health. National pain strategy - A comprehensive population health-level strategy for pain. National Institutes of Health. 2016. https://iprcc.nih.gov/sites/default/files/HHSNational_Pain_Strategy_508C.pdf

- Fishman SM, Young HM, Arwood EL. Core competencies for pain management: results of an interprofessional consensus summit. Pain Med. 2013;14(7):971–81. doi:10.1111/pme.12107.

- Watt-Watson J, McGillion M, Hunter J, Choiniere M, Clark AJ, Dewar A, Johnston C, Lynch M, Morley-Forster P, Moulin D, et al. A survey of prelicensure pain curricula in health science faculties in Canadian universities. Pain Res Manag. 2009;14(6):439. doi:10.1155/2009/307932.

- Mezei L, Murinson BB. Pain education in North American medical schools. J Pain. 2011;12(12):1199–208. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2011.06.006.

- Hoeger Bement MK, Sluka KA. The current state of physical therapy pain curricula in the United States: a faculty survey. J Pain. 2015;16(2):144–52. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2014.11.001.

- Wideman TH, Miller J, Bostick G, Thomas A, Bussieres A, Wickens RH. The current state of pain education within Canadian physiotherapy programs: a national survey of pain educators. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(9):1332–38. doi:10.1080/09638288.2018.1519044.

- Briggs EV, Carr ECJ, Whittaker MS. Survey of undergraduate pain curricula for healthcare professionals in the United Kingdom. Eur J Pain. 2011;15(8):789–95. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.01.006.

- Briggs EV, Bettelli D, Gordon D, Kopf A, Ribeiro S, Puig MM, Kress HG. Current pain education within undergraduate medical studies across Europe: advancing the provision of pain education and learning (appeal) study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(8):e006984. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006984.

- Hoeger Bement MK, St Marie BJ, Nordstrom TM, Christensen N, Mongoven JM, Koebner IJ, Fishman SM, Sluka KA. An interprofessional consensus of core competencies for prelicensure education in pain management: curriculum application for physical therapy. Phys Ther. 2014;94(4):451–65. doi:10.2522/ptj.20130346.

- Hush JM, Nicholas M, Dean CM. Embedding the IASP pain curriculum into a 3-year pre licensure physical therapy program: redesigning pain eduction for future clinicians. Pain Rep. 2018;3(2):e645. doi:10.1097/PR9.0000000000000645.

- The British Pain Society. A practical guide to incorporating pain education into pre-registration curricula for healthcare professionals in the UK. London; 2018. https://www.britishpainsociety.org/static/uploads/resources/files/BPS_Pre-registration_Practical_Guide_Feb_2018_1wsCBZo.pdf.

- Royal College of Nursing. RCN Pain knowledge and skills framework for the nursing team. RCN. 2015. https://www.britishpainsociety.org/static/uploads/resources/files/RCN_KSF_2015.pdf

- Wideman TH, Miller J, Bostick G, Thomas A, Bussières A. Advancing pain education in Canadian physiotherapy programmes: results of a consensus-generating workshop. Physiother Can. 2018;70(1):24–33. doi:10.3138/ptc.2016-57.

- Graham ID, Tetroe JM. Getting evidence into policy and practice: perspective of a health research funder. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Journal de l’Academie Canadienne de Psychiatrie de L’enfant Et de L’adolescent. 2009;18:46–50.

- Ross S, Lavis J, Rodriguez C, Woodside J, Denis JL. Partnership experiences: involving decision-makers in the research process. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2003;8(2):26–30. doi:10.1258/135581903322405144.

- Walter I, Davies H, Nutley S. Increasing research impact through partnerships: evidence from outside health care. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy. 2003;8(2_suppl):58–61. doi:10.1258/135581903322405180.

- Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, Robinson N. Lost inn knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(1):13–24. doi:10.1002/chp.47.

- Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham I. Defining knowledge translation. CMAJ. 2009;181(3–4):165 168. doi:10.1503/cmaj.081229.

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health. 2000;23(4):334–40. doi:10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G.

- Caelli K, Ray L, Mill J. “Clear as mud”: toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2003;2(2):1–13. doi:10.1177/160940690300200201.

- Bradshaw C,S, Doody O. Employing Atkinsona qualitative description approach in healthcare research. Glob Qual Nurs Res. 2017;4:1–8.

- Barry CA, Britten N, Barbar N, Bradley C, Stevenson F. Using reflexivity to optimize teamwork in qualitative research. Qual Health Res. 1999;9(1):26–44. doi:10.1177/104973299129121677.

- Koch T, Harrington A. Reconceptualizing rigour: the case for reflexivity. J Adv Nurs. 1998;28(4):882–90. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00725.x.

- IASP curriculum outline on pain for physical therapy. International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). 2021. https://www.iasp-pain.org/education/curricula/iasp-curriculum-outline-on-pain-for-physical-therapy/

- Fishman SM, Carr DB, Hogans B, Cheatle M, Gallagher RM, Katzman J, Mackey S, Polomano R, Popescu A, Rathmell JP, et al. Scope and nature of pain- and analgesia-related content of the United States medical licensing examination (USMLE). Pain Med. 2018;19(3):449–59. doi:10.1093/pm/pnx336.

- Thomas A, Bussières A. Knowledge translation and implementation science in health professions education: time for clarity? Acad Med. 2016;91(12):e20. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001396.

- Thomas A, Bussières A. Towards a greater understanding of implementation science in health professions education. Acad Med. 2016;91(12):e19. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001441.

- Karazivan P, Dumez V, Flora L, Pomey M-P, Del Grande C, Ghadiri DP, Fernandez N, Jouet E, Las Vergnas O, Lebel P. The patient-as-partner approach in health care: a conceptual framework for a necessary transition. Acad Med. 2015;90(4):437–41. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000603.

- Pomey M-P, Hihat H, Khalifa M, Lebel P, Néron A, Dumez V. Patient partnership in quality improvement of healthcare services: patients’ inputs and challenges faced. Pxj. 2015;2:29–42.

- Ng W, Slater H, Starcevich C, Wright A, Mitchell T, Beales D. Barriers and enablers influencing healthcare professionals’ adoption of a biopsychosocial approach to musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review and qualitative evidence synthesis. Pain. 2021;162(8):2154–85. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002217.

- American Physical Therapy Association, Canadian Physiotherapy Association. Joint CPA APTA statement: north American collaboration to address opioid epidemic. APTA. 2017. https://www.apta.org/article/2017/01/27/joint-cpa-apta-statement-opioid-epidemic

- Synnott A, O’Keeffe M, Bunzli S, Dankaerts W, O’Sullivan P, O’Sullivan K. Physiotherapists may stigmatise or feel unprepared to treat people with low back pain and psychosocial factors that influence recovery: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2015;61(2):68–76. doi:10.1016/j.jphys.2015.02.016.

- Overmeer T, Linton SJ, Boersma K. Do physical therapists recognize established risk factors? Swedish physical therapists’ evaluation in comparison to guidelines. Physiotherapy. 2004;90(35–41.

- Bishop A, Foster NE. Do physical therapists in the United Kingdom recognize psychosocial factors in patients with acute low back pain? Spine. 2005;30(11):1316–22. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000163883.65321.33.

- Zangoni G, Thomson OP. ‘I need to do another course’ - Italian physiotherapists’ knowledge and beliefs when assessing psychosocial factors in patients presenting with chronic low back pain. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice. 2017;27:71–77. doi:10.1016/j.msksp.2016.12.015.

- Becker WC, Dorflinger L, Edmond SN, Islam L, Heapy AA, Fraenkel L. Barriers and facilitators to use of non-pharmacological treatments in chronic pain. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(a):41. doi:10.1186/s12875-017-0608-2.

- Bessette J, Généreux M, Thomas A, Camden C. Teaching and assessing advocacy in Canadian physiotherapy programmes. Physiother Can. 2020;72(3):305–12. doi:10.3138/ptc-2019-0013.

- Kern DE. Curriculum development: an essential educational skill, a public trust, a form of scholarship, an opportunity for organizational change. Qatar: Presented at Weill Cornell College of Medicine; 2014.

- Miller G. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65(9):A63–S67. doi:10.1097/00001888-199009000-00045.

- Kirk MA, Kelley C, Yankey N, Birken SA, Abadie B, Damschroder L. A systematic review of the use of the consolidated framework for implementation research. Implement. Sci. 2016;11(72).

- Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Opra Widerquist MA, Lowery J. Conceptualizing outcomes for use with the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR): the CFIR outcomes addendum. Implementation Science. 2022;17(1):7. doi:10.1186/s13012-021-01181-5.

Appendix A.

Evolution of strategic priorities

Table 3. Stakeholder-endorsed strategic plan for improving pain education in Canadian PT programs

Appendix B.

Stakeholder interview guide

What were your broad thoughts on the strategies generated within the Pain Education in Physiotherapy workshop?

Can you identify any additional strategies?

What strategies are of particular interest/relevance to your stakeholder group?

Why?

What are strategies are not of particular interest/relevance to your stakeholder group?

Why?

How might you approach implementation of the strategies that are of interest/relevance to your group?

What are the most important next steps for strategies that are of interest/relevance to your group?

From the perspective of your stakeholder group, what are the most important barriers/facilitators for these next steps?

How can these barriers be best addressed?

How can these facilitators be taken advantage of?