ABSTRACT

Memory biases for previous pain experiences are known to be strong predictors of postsurgical pain outcomes in children. Until recently, much research on the subject in youth has assessed the sensory and affective components of recall using single-item self-report pain ratings. However, a newly emerging focus in the field has been on the episodic specificity of autobiographical pain memories. Still in its infancy, cross-sectional work has identified the presence of various memory biases in adults living with chronic pain, one of which concerns the lack of spatiotemporal specificity. Moreover, a recent prospective longitudinal study found that adults scheduled for major surgery who produced fewer specific pain memories before surgery were at greater risk of developing chronic postsurgical pain up to 12 months later. The present review draws on this research to highlight the timely need for a similar line of investigation into autobiographical pain memories in pediatric surgical populations. We (1) provide an overview of the literature on children’s pain memories and underscore the need for further research pertaining to memory specificity and related neurobiological factors in chronic pain and an overview of the (2) important role of parent (and sibling) psychosocial characteristics in influencing children’s pain development, (3) cognitive mechanisms underlying overgeneral memory, and (4) interplay between memory and other psychological factors in its contributions to chronic pain and (5) conclude with a discussion of the implications this research has for novel interventions that target memory biases to attenuate, and possibly eliminate, the risk that acute pain after pediatric surgery becomes chronic.

RÉSUMÉ

Les biais de mémoire concernant les expériences douloureuses antérieures sont connus pour être de puissants prédicteurs de la douleur post-chirurgicale chez les enfants. Jusqu'à récemment, la plupart des études sur ce sujet menées auprés des jeunes évaluaient les composantes sensorielles et affectives du souvenir en utilisant des auto-évaluations de la douleur comportant un seul énoncé. Cependant, la spécificité épisodique des souvenirs autobiographiques de la douleur a récemment fait son apparition en tant que nouveau centre d’intérêt dans le domaine. Bien qu’ils en soient encore à leurs premiers balbutiements, des travaux transversaux ont déterminé que divers biais de mémoire étaient présents chez les adultes vivant avec la douleur chronique, dont l’un concerne le manque de spécificité spatiotemporelle. De plus, une étude longitudinale prospective récente a révélé que les adultes en attente d’une chirurgie majeure qui avaient moins de souvenirs spécifiques de la douleur avant la chirurgie étaient plus à risque de développer de la douleur post-chirurgicale chronique jusqu’à 12 mois plus tard. La présente étude s’appuie sur cette étude pour souligner la nécessité de mener des études similaires sur les souvenirs autobiographiques de la douleur au sein de la population chirurgicale pédiatrique. Nous (1) faisons un survol de la littérature sur les souvenirs de la douleur chez les enfants et soulignons la nécessité de poursuivre la recherche sur la spécificité de la mémoire et sur les facteurs neurobiologiques liés à la douleur chronique, ainsi qu’un survol (2) du rôle important des caractéristiques psychosociales des parents (et des fréres et sœurs) dans le développement de la douleur chez les enfants, (3) les mécanismes cognitifs qui sous-tendent la mémoire surgénérale et (4) l’interaction entre la mémoire et d’autres facteurs psychologiques qui contribue à la douleur chronique et (5) concluons par une discussions sur les implications de cette étude pour les interventions novatrices qui ciblent les biais de mémoire pour atténuer, et possiblement éliminer, le risque que la douleur aigue aprés une chirurgie pédiatrique devienne chronique.

Introduction

The term “pain memory” has been used to refer to various phenomena in the field of pain. First introduced by Dennis and MelzackCitation1 to explain the persistence of pain behaviors in a rodent model of deafferentation, it was later used in a human context by Katz and MelzackCitation2 to describe phantom limb sensations and pains in limb amputees that closely resembled those that they had experienced in the limb before amputation and that persisted despite removal of the affected limb. The authors distinguished between two memory components underlying these experiences: The somatosensory component, which refers to unconscious, nondeclarative/implicit memories, and the cognitive component, pertaining to declarative/explicit memories characterized by conscious retrieval processes responsible for contextualizing painful experiences, sometimes through recollections of specific events. Since its introduction 31 years ago, investigation into the latter has led to the discovery that certain aspects of declarative memory are in fact distorted in chronic pain,Citation3 often with compromising implications for postsurgical pain outcomes in adults and in youth.Citation4,Citation5 As such, it is unsurprising that a growing area in the field of chronic pain has focused on the study of various types of memory biases (i.e., differences in the way people remember information) and their effects on individuals’ pain trajectories. The term pain memory has subsequently been used in a different context to refer to patients’ declarative memories of how intense their pain was when it was first experienced.Citation4–6 The usage of the term henceforth refers to this definition.

Chronic postsurgical pain (CPSP) is a common manifestation of chronic pain that develops as a consequence of surgery.Citation7 In youth, approximately 15% to 25% of patients go on to develop moderate to severe pain that persists years after surgery.Citation8–10 Given its high incidence and morbidity, research on the development of pediatric CPSP is critical to improving our understanding of the condition itself and also to serve as a useful general model for studying how, why, and in whom pain becomes chronic. Moreover, identifying the causal, modifiable risk factors involved in CPSP is crucial because it can aid in the ultimate goal of developing effective prevention and management strategies.Citation11

One factor that has been shown to predict CPSP in children is their memory for pain. At present, much of what is known about memory in chronic pain stems from studies conducted in adults. The paucity of research in pediatric populations underscores an urgent need for prototypical investigation. Nevertheless, the available literature can shed light on potentially shared mechanisms and provide valuable insight into the lifelong transmission of chronic pain. Furthermore, the research that has been conducted on pain memories in youth has predominantly assessed memory by comparing responses on single-item pain measures administered at the time of the inciting painful event and again at the time of recall. Though this approach taps the memory’s sensory and affective components, it does not assess the spatiotemporal and perceptual qualities that are integral to autobiographical memory. The present review introduces a novel perspective by drawing on a broader understanding of autobiographical memory with the aim of describing strategies to advance our assessment, methodology, and understanding of children’s memory for postsurgical pain that have implications for preventing and/or managing pain using specific memory-enhancing interventions. We focused our search on overgeneral memory (OGM) and included all the studies on OGM in chronic pain that we could find. We searched PubMed central using “OGM AND pain” and “autobiographical memory AND pain.” For the former, the search led to 5 articles, which we reviewed, and we included 3 of the articles we thought were relevant. With the latter, we retrieved 48 articles, of which we included 6. We also searched the reference sections of relevant papers for additional articles. The above searches were limited to empirical articles using adult or pediatric samples as well as animal studies and included only articles published in English.

We begin with an introduction to the development of autobiographical memory. This is followed by a discussion of several findings from neuroimaging studies that implicate changes in specific memory-related brain regions as risk factors for the development of adult CPSP. As a general rule, we refer to the relevant adult literature when similar work on youth has not been published. Returning to the cognitive–behavioral realm, we provide an overview of the current state of research on children’s memory for pain as it applies to CPSP. Considering the important role of parents in children’s pain development, we then address parent–child reminiscing in the context of autobiographical memory for postsurgical pain. Next, we introduce certain biases in autobiographical memory, such as reduced spatiotemporal specificity and its manifestation in chronic pain, as well as the role of anxiety and catastrophizing in predicting these biases. Finally, we discuss intervention implications and provide suggestions for future research.

Development of Autobiographical Memory

Autobiographical memory refers to a declarative memory system comprising specific past events (episodic memory) and factual knowledge about oneself and the world (semantic memory).Citation12,Citation13 These two components are highly interdependent and often influence each other at various stages of memory processing.Citation14,Citation15 Autobiographical memory is necessary for our ability to perform various fundamental, non-mnemonic functions such as directing future behavior through imagination, problem solving, and decision making.Citation16–20 It allows us to maintain a positive self-imageCitation21 and sense of self-continuity over time,Citation22,Citation23 foster and sustain social relationships with others,Citation24,Citation25 regulate negative emotionality,Citation17,Citation26 think creatively,Citation27,Citation28 and solve problems efficiently.Citation29

The episodic component of autobiographical memory is defined by autonoetic consciousness, which is the ability to mentally project oneself across time to “re-experience” specific events from the past and to imagine the future.Citation13 Rather than being exact replicas of prior experiences, episodic memories entail reconstructive processes that are prone to error.Citation30–33 That is, episodic memory is considered to be the product of binding accurate event details with relevant semantic or schematic knowledge and details from other events in order to fill gaps in remembering and make memories more coherent.Citation30,Citation34 Therefore, the way in which people remember and interpret their life experiences, to a great extent, depends on their preexisting knowledge and preconceptions about the world.Citation31 On one hand, this can lead to biases that result in memory distortions.Citation35 However, prior knowledge can also act to enhance new memories by integrating episodes within an existing semantic network.Citation36,Citation37 Younger children have a smaller repertoire of semantic knowledge to draw on, and this might be one reason why they are generally more susceptible to false memories and suggestibility.Citation38 Though the inexact nature of memory retrieval might appear fundamentally disadvantageous, a memory system that is constructive in nature serves an adaptive role, because it allows individuals to categorize information, generalize knowledge across tasks, and imagine and simulate personal future events.Citation16,Citation39

Throughout early life, episodic autobiographical memory is associated with a more gradual developmental trajectory than semantic memory.Citation40 In particular, infants develop semantic autobiographical memory before episodic memory,Citation41,Citation42 with the former potentially providing a foundation for the latter.Citation43 Because of what has been called “infantile amnesia” and ”childhood amnesia,” beginning around 6 years of age, humans show an inability to recall episodic memories for events from before the age of 2 to 4.Citation42,Citation44–47 A prospective study by Peterson et al.Citation46 found that in a sample of children aged 4 to 9 years old, younger children forgot most of their baseline memories, with the greatest amount of forgetting occurring in the first 2 years, whereas older children did not. Younger children also had more inconsistencies in their memories at subsequent assessments 2 and 8 years later. These findings suggest that age 6 to 7 years seems to be a defining point for children’s ability to remember and maintain consistency in the recollections of their earliest memories. Interestingly, other prospective studies by this research group have shown that as children get older, they postdate their memories for events that were previously assigned earlier dates. Therefore, it is possible that our earliest memories may be even older than we believe.Citation48,Citation49 An alternative hypothesis on the etiology of infantile/childhood amnesia posits that immaturity of certain memory-related structures (e.g., dentate gyrus of the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex) during these early developmental years precludes memories from forming in the first place.Citation42,Citation50 The emergence of episodic memory later on in early childhood is often attributed to the maturation of these brain structures, along with influences from higher-order cognitive abilities such as executive functioning,Citation51 language development,Citation52 sense of selfCitation53 and theory of mind,Citation54,Citation55 and cultural and social factors.Citation41,Citation52

Age-related improvements in autobiographical memory begin to emerge after early childhood. Episodic memory develops gradually across childhood into early adolescence, either withCitation51 or without semantic memory (as well as other basic cognitive abilities).Citation40 One study assessed autobiographical memory and memory for everyday events in youth between 8 and 16 years of age.Citation56 In line with previous findings, the results showed temporal increases in memory, with a larger effect for episodic than semantic details. Females retrieved more episodic but not semantic details than males, although this difference decreased when retrieval was facilitated by probing questions from the experimenter. Taken together, with one possible exception, these studies support the suggestion that among children and adolescents, autobiographical memory improves with age, with greater earlier increases in episodic than semantic memory.

Neural Substrates of Autobiographical Memory as Risk Factors for the Transition to Chronic Pain

Mechanisms underlying synaptic plasticity in memory and learning resemble those responsible for initiating and maintaining chronic pain states.Citation57 In particular, similarities have been noted between hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP) and hyperalgesia-associated central sensitization in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord.Citation58,Citation59 LTP has also been observed at C-fiber synapses in the spinal dorsal horn.Citation59,Citation60 LTP at both hippocampal and spinal C-fiber synapses leads to changes in dendritic spine shape with implications for neuropathic pain.Citation61

In addition, the N-terminal truncated form of protein kinase C zeta (PKMζ) is an atypical protein kinase C considered essential for sustaining late-stage LTP and long-term memory.Citation62 The maintenance of these memories is disrupted by zeta inhibitory peptide.Citation63 Interestingly, PKMζ is also necessary for maintaining chronic pain states through spinal nociceptive plasticity, and the same inhibitory action of this molecule by zeta inhibitory peptide reverses persistent pain hypersensitivity.Citation64 These findings raise the possibility of a common mechanism in the maintenance of LTP, memory, and chronic pain.Citation65

Recent neuroimaging studies in adults have found that the neural substrate of episodic autobiographical memory, the hippocampus and associated structures, undergoes morphological and volumetric changes in chronic pain. In one study, individuals with subacute back pain were followed for 3 years and assessed by magnetic resonance imaging at five time points (baseline, 8, 28, 56, 156 weeks). The results showed that smaller hippocampal and amygdala volumes at the baseline assessment were risk factors for the transition to chronic pain 3 years later.Citation66 Transition to chronic back pain was also associated with changes in functional connectivity within the anterior hippocampus and between it and other cortical brain regions such as the medial prefrontal cortex and cingulate gyrus, suggesting possible disruptions in emotional learning.Citation67 What remains unknown but equally important are the mechanisms underlying baseline levels of smaller hippocampal volume in the adult patients of this study. There is evidence that exposure to life stressors in early childhood is a risk factor for smaller hippocampal volume later in life.Citation68 Therefore, when studying brain mechanisms and the subsequent development of pain, it is important to consider the influence of other circumstances or factors that might contribute to explaining the relationship. Another study found that nearly 80% of adults with chronic low back pain remembered previously experienced pain as more intense than originally rated, and this memory bias was associated with expansion of an area in the left posterior hippocampus.Citation69 In the only pediatric study we found, children (9–13 years) with complex regional pain syndrome had a smaller volume of gray matter in the hippocampus, among other brain regions, than sex and age-matched healthy controls.Citation70

Chronic pain has been proposed to reflect a state of extinction-resistant emotional learning characterized by the acquisition and accumulation of negative memories associated with the experience of pain.Citation71 Consistent with this suggestion, learning and memory formation in adults involves hippocampal neurogenesis, which also has been linked to the development and maintenance of chronic pain. This suggests that hippocampal associative learning might contribute to persistence of pain.Citation72 Moreover, a study in rodents with neuropathic pain showed that the downregulation of dorsal hippocampal circuitry, a region responsible for declarative and spatial memory processes, caused increased pain behaviors.Citation73 The authors of this study suggested that deactivating dorsal hippocampal circuitry might disrupt the extinction of declarative memories of pain, thereby permitting pain to persist.

In summary, evidence of overlapping brain circuitry between pain, memory, and emotion, as well as the structural and functional changes in this circuitry that predict pain chronicity, raises the possibility that the cognitive processes associated with dorsal hippocampal activity, such as autobiographical memory, might be causally involved in the transition from acute to chronic pain.

Children’s Memory for Postsurgical Pain

Until recently, much of the research in children has focused on investigating the accuracy of individuals’ recollections about painful experiences based on single-item self-report pain measures such as a 0 to 10 numeric pain rating scale (NRS) or 10 cm visual analogue scale for pain intensity and pain affect or anxiety. One approach has been to calculate the difference between the youth’s recall of pain intensity and the initial pain score obtained when the youth was in pain.Citation74 Higher difference scores are taken as an indication of an “exaggeration in negative memory” in which the memory of pain is greater than initial pain. Others use the terms “negatively biased pain memory” when the NRS score for recalled pain is higher than the initial pain score and “positively biased pain memory” when the initial NRS pain score is higher than recalled score.Citation6

In youth, remembering painful events in a negative way is associated with worse postsurgical pain outcomes where children’s memory for postsurgical pain intensity has been found to be a stronger predictor of reported pain levels 5 months after the surgery than the initial pain ratings.Citation5 Furthermore, in a prospective longitudinal study of 237 children who underwent various surgical procedures, Noel et al.Citation6 demonstrated that children who developed negatively biased memories for pain intensity 1 year after surgery had more intense pain at 6- and 12-month follow-up than those with accurate or positive memories. Psychological factors played an important role in this relationship, where higher levels of baseline anxiety sensitivity and pain catastrophizing in the days after surgery while in hospital (i.e., 48 to 72 hours) predicted adolescents’ negatively biased memories at the 12-month follow-up. Parallel findings are evident in a previous study where parental anxiety and higher levels of postsurgical pain predicted negatively biased pain memories in young children undergoing tonsillectomy.Citation75 Similarly, child and parent pain catastrophizing have also been shown to be associated with biased pain memory development in adolescents undergoing spinal fusion and pectus repair.Citation76 Although these findings highlight the importance of memory biases in children’s pain outcomes, this method of assessing pain memories is somewhat limited in that it reduces memory for pain intensity or pain affect to a deviation from the original score or to a partial correlation coefficient controlling for initial pain measured using a simple single-item NRS or visual analogue scale. A widely overlooked area in the study of pain, including pediatric postsurgical pain, has to do with the episodic quality of the autobiographical memories themselves as generated by narrative descriptions.

Parent–Child Reminiscing about Past Pain

Children’s autobiographical memories do not develop in a vacuum. Reminiscing (i.e., talking about past events) with parents creates a powerful sociocultural context in which children’s memories can be retrieved, recalled, and reconstructed. Developmental psychology studies have repeatedly demonstrated that parent–child reminiscing predicts a host of developmental outcomes.Citation77 Children of mothers who reminisce about past distressing events using an elaborative reminiscing style (i.e., detailed discussions about the past characterized by open-ended questions, new information, and emotion-laden language) in comparison to a repetitive style (i.e., use of closed-ended questions, frequent switches between topics, focus on facts as opposed to emotions) develop more detailed, coherent, and evaluative autobiographical memories.Citation78,Citation79 These children also go on to have better developmental outcomes in emotional regulation, cognition, and social competence.77,Citation80–82 Novel work by Noel et al.Citation83 linked parent–child reminiscing about a recent surgery to certain types of pain memory biases. A sample of 112 children undergoing tonsillectomy and their parents reminisced about the tonsillectomy 2 weeks after surgery. Children of parents who introduced new details about the surgery, used more positive emotion-related words (e.g., happy, laughing), and used fewer pain-related words (e.g., hurt, sore) remembered their pain accurately or in a less distressing way (i.e., recalled less pain compared to the initial report). These results suggest that elements of elaborative reminiscing contribute to optimal pain memory development.Citation83

Parent reminiscing style is amenable to change. Interventions aimed at teaching parents how to reminisce elaboratively resulted in more optimal developmental outcomes.Citation84 It was hypothesized that there might be more constructive ways for children and their parents to reminisce about past pain to alter how children remember their past pain.Citation85 Findings from this research were used to inform the development of a novel parent-led memory-reframing intervention.Citation86 In a randomized controlled trial, 65 young children who were scheduled to undergo tonsillectomy and one of their parents were randomly assigned to a memory-reframing intervention or an active control group. In the intervention group, parents were taught to reminisce about past pain by focusing on positive aspects of pain, using fewer pain-related words, reducing negative exaggerations about past pain, and praising the child for their bravery and pain-related coping skills to foster pain-related self-efficacy. The results showed that children in the intervention group developed more accurate or positively biased memories for their pain intensity on the first day after surgery compared to the control group. These findings provide preliminary evidence that teaching parents to implement certain reminiscing elements can have a positive impact on their children’s memories for pain after surgery. The study did not, however, find any effect of the intervention on children’s memories for pain that occurred on the day of their surgery, which could be attributable to residual effects of general anesthesia on memory during the immediate recovery stage.Citation86 Consequently, this intervention was found to be both feasible and acceptable. Further research is needed to examine its efficacy in larger samples as well as the intervention’s potential to prevent CPSP.

Both parent and child attachment styles are associated with the formation and retrieval of children’s autobiographical memories (i.e., encoding, elaborating, retrieving, and reporting).Citation87 The influence of attachment styles on autobiographical memory is particularly powerful for attachment-related memories (i.e., memories of events that involve parent–child interactions and/or emotion regulation).Citation87 Attachment styles have been also studied in the context of parent–child reminiscing. The latter has been conceptualized as one of the manifestations of attachment security.Citation88 Parents of securely attached children reminisced about distressing experiencesCitation89 using high levels of emotional availability and elaboration.Citation90 In contrast, parents of insecurely attached children reminisced in a repetitive and topic-switching manner.Citation90 Given that children’s memories for past events involving pain are distressing and usually involve parent–child interaction, as well as emotion regulation, parent and child attachment status may play a key role in the formation of children’s memories for past pain.

Existing research has established the associations between attachment styles and chronic pain onset and maintenance in adult populations.Citation91 Less is known about the contribution of attachment styles to pediatric chronic or persistent postsurgical pain. Attachment models highlight and explain some of the vulnerability (e.g., insecure attachment styles) and maintenance (e.g., maladaptive coping strategies, ongoing attachment-related anxiety) factors in pediatric chronic pain.Citation92,Citation93 Compared to pain-free peers, youth with chronic functional pain were more likely to have at-risk attachment patterns and unresolved loss and/or trauma.Citation93 Future investigations of pediatric CPSP and associated memory biases should assess attachment styles, as well as intergenerational transmission of trauma, to elucidate their role, as well as therapeutic potential, in pediatric postsurgical pain trajectories.

Overgeneral Memory Bias

An autobiographical memory bias that has not been widely studied but is slowly gaining traction in chronic pain research concerns differences in autobiographical memory specificity.Citation94–98 According to the self-memory system model of autobiographical memory organization,Citation99 memories are stored and retrieved in a hierarchy of levels of representation that is arranged from general to specific. During recollection, the memory search begins at the highest, most general level of conceptual themes and lifetime periods (e.g., “my 20s”) before proceeding to intermediately general memories of repeated (e.g., “every time I stub my toe”) and extended (“My back ached for a week after my surgery”) events and ultimately ends with the lowest tier of the hierarchy, which is event-specific knowledge (“I felt relieved and pain-free the day I left the hospital”). The habitual tendency not to recollect specific memories from the final level is known as an overgeneral memory bias. This phenomenon is well established in mental health disorders such as depression, posttraumatic stress disosrder (PTSD), and complicated grief,Citation100–102 including in children and adolescents; there is strong evidence that OGM is associatedCitation103–105 with and even predictive of depression in youth.Citation106,Citation107 Common tools for assessing autobiographical memory specificity typically involve tasks that assess participants’ abilities to freely recall specific events, sometimes in response to neutral or emotional cue words or incomplete sentence stems. Memory responses are then coded for the presence or absence of a temporally specific event and the number of each type of memory is summed to yield a composite score that represents the overall degree of specificity or OGM in an individual’s retrieval style.

Overgeneral Memory Bias in Chronic Pain

To our knowledge, OGM has yet to be examined in youth with chronic pain, because we were unable to find any published studies on the topic. In the adult literature, four studies have examined autobiographical memory specificity in individuals with chronic pain, all of which employed cross-sectional designs.Citation94–98 Three of these identified an OGM bias in patients with chronic pain,94,95,97 whereas the fourthCitation81 did not, largely because of methodological problems described below.

Liu et al.Citation94 administered the Chinese version of the Autobiographical Memory TestCitation108 (AMT) to a sample of 170 healthy controls and 176 outpatients with heterogenous chronic pain conditions for a minimum of 6 months. Participants were asked to describe the first specific personal event that came to mind in response to seeing positive and negative cue words. In line with the standard AMT protocol, nonspecific responses were followed by a probe from the experimenter. After controlling for symptoms of depression and anxiety, compared to the healthy controls, participants who had chronic pain generated a greater number of overgeneral memory independent of cue type. Accounting for the same covariates, outpatients also showed slower overall retrieval latency (time to initial response), with a nonsignificant trend toward slower response times for positive cue words than for negative cue words. As would be expected, patients with chronic pain had significantly more symptoms of depression and anxiety, and lower pain self-efficacy scores predicted OGM across all patients. The authors concluded that the patients with chronic pain displayed distortions in autobiographical memory, which, together with the statistically nonsignificant delay in accessing positively cued memories, reflects an affective avoidance mechanism for regulating negative emotionality. Thus, individuals with chronic pain might find it more difficult to confront experiences associated with intense or negative emotions and therefore avoid recalling these specific memories.

Quenstedt et al.Citation95 used an online version of the Sentence Completion for Events from the Past TestCitation109 and a future-oriented equivalentCitation110 to assess specificity in memories and future imagination, respectively, in patients with chronic pain. Eighty-four participants with self-reported chronic pain and 102 self-identified healthy controls generated specific memories and plausible personal future events in response to neutral sentence stems. Controlling for symptoms of depression and anxiety, the results not only corroborated previous findings of an overgeneral memory bias in individuals with chronic pain when recollecting the past but also showed the novel finding of an overgeneral memory bias when imagining personal events in the future. This observation aligns with the previously mentioned notion that the cognitive processes involved in future thinking overlap with those that underlie autobiographical memory.16,19,Citation111 The authors of this study did not report correlations between performance on the memory and future thinking tasks. However, given what is known about the role of autobiographical memory processes in shaping our self-representations and future goals, it is likely that these same processes play an important role in healing and recovery from chronic pain.Citation17,Citation98

The third study, by Vucurovic et al.,Citation97 investigated patients with fibromyalgia (>6 months’ duration) and their self-defining memories: a subset of autobiographical memories that correspond to one’s sense of identity and establish continuity in our personal life narratives. These memories are vivid and well-rehearsed, often encompassing an individual’s central goals in life and internal conflicts.Citation112,Citation113 The results showed that relative to healthy controls, patients with fibromyalgia exhibited significantly increased OGM (among other memory differences, discussed in a subsequent section).

The fourth studyCitation96 recruited a Norwegian sample of 43 patients with diverse chronic pain conditions and compared those with and without PTSD on autobiographical memory using the AMT. In contrast to Liu et al.,Citation94 the results failed to show differences between the two groups or a significant relationship between the extent of pain and memory specificity, although it did reveal another type of memory bias in which the memories were of more negative emotionality. The study by Siqveland et al.Citation96 has several limitations, acknowledged by the authors themselves, that might explain the absence of differences in autobiographical memory. First, the sample size was very small, potentially precluding sufficient power to detect real effects. Moreover, the participants in the study had moderate-to-severe chronic pain. As a result, it is possible that the entire sample may have had more overgeneral memory, which would not have been detected due to the absence of a healthy control group.

Taken together, these findings suggest that people living with a chronic pain condition such as fibromyalgia might experience certain distortions in their sense of self that contribute to the maintenance of their pain. Overall, with one exception,Citation96 the few published studies suggest that OGM plays an important role in chronic pain, with some evidence extending to individuals’ identities, emotional self-regulation abilities, and future imaginings.

Need for Prospective Longitudinal Research on Memory Specificity in Pediatric Chronic Postsurgical Pain

Until recently, longitudinal studies have not been conducted to evaluate the temporal relationship between autobiographical memory quality and the development of chronic pain over time. A study from our lab addressed these gaps by following a sample of 98 adults scheduled for major surgery over the span of a year.Citation98 Participants were administered the AMT before and 1 month after surgery, when they were asked to describe specific memories in response to a series of positive and pain-related cue words that were verbally presented by the experimenter.Citation98 After controlling for known risk factors for chronic pain (preexisting pain, psychological distress, age, and sex), individuals who produced fewer context-specific pain-related memories before surgery, as well as those who had slower response times for pain memories, were at greater risk of developing chronic pain 1, 3, 6, and 12 months later. The authors proposed that the characteristic preoccupation with abstract lifetime themes and categories of events related to pain associated with OGM might perpetuate self-schemas that become intertwined with painCitation114 and, in turn, initiate and/or maintain the pain itself. Conversely, the tendency to retrieve specific pain-related memories is posited to provide individuals with more concrete contextual, sensory, and perceptual information that serves to disconfirm potentially vague and inaccurate self-beliefs. Upon repeated activation, these perceptual details might contribute to a more adaptive schematic base that is conducive to recovery. Referring back to the literature on emotions, it is also possible that similar mechanisms of rumination, avoidance, and executive functioning impede the search for a specific and personal pain-related memory in individuals who show a cognitive bias for pain-related information. As discussed in the next section, an important line of future research will be to explore the prospective relationships between these psychological elements associated with OGM in youth with chronic pain.

Explaining the Link between OGM and Chronic Pain: the CarFAX Model

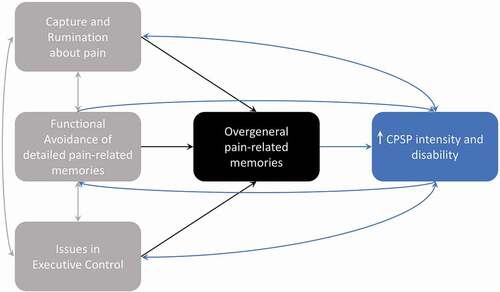

The cognitive processes associated with rumination, avoidance, and poor executive control, either separately or in combination, have been posited to interfere with the search for a specific memory and to cause retrieval to remain fixed at the overgeneral level of the autobiographical knowledge base.Citation115 The first component of the proposed CaRFAX model, capture and rumination (CaR), occurs when self-relevant cues activate repeated retrieval of general memories, thereby “capturing” the individual in a ruminative process that interferes with the search for a specific memory. Next, specific memories associated with unpleasant or intense emotional experiences are avoided to prevent activating intense and negative emotions in what is termed functional avoidance (FA). Finally, limitations in executive control (X) such as working memory and inhibition of irrelevant information can also impede event-specific retrieval. This model has been examined extensively in adults with mental health conditions, but it has not received much attention in the pediatric literature.

Two studies showed that negative rumination is linked to OGM in children.Citation104 In one study, negative self-beliefs significantly predicted OGM generated in response to positive and negative cue words.Citation116 Park et al.Citation117 showed that teenagers with major depressive disorder exhibited increased OGM for negative cues after undergoing a rumination manipulation when compared to participants in a distraction condition. The observed bias for negative cues in particular aligns with the notion that individuals with negative self-beliefs are particularly susceptible to capture errors.Citation104 Regarding executive functioning, findings in children with OGM are mixed. Two studies failed to find any associations between a cognitive measure of inhibition and OGM,Citation118,Citation119 whereas another found that inhibitory control on a measure of temperament and self-regulation mediated the relationship between depressive symptoms and OGM in primary school children.Citation120 Additionally, adolescents with a history of maltreatment but no mental health disorders who were living in residential child care were found to have fewer specific memories and lower working memory scores on the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children IV Total Digit Span and Arithmetic subtests.Citation121 Valentino et al.Citation119 found that category fluency (the ability to retrieve semantically related words) but not letter fluency (the ability to quickly generate words beginning with the same letter) uniquely explained variance in the number of overgeneral memory. Another study, however, did not find this relationship.Citation103 Finally, to our knowledge, functional avoidance has yet to be explored in children. It should be noted that when investigating these three mechanisms in pediatric populations, age is an important factor to consider. For example, adolescents tend to exhibit greater rumination than preadolescents,Citation122–126 and this behavior increases with age.Citation127 Conversely, challenges with executive control are more prevalent in younger children likely due to maturational factors, because working memory capacity and inhibition generally increase across childhood and into early adolescence.Citation128–132 As such, different stages of development should be accounted for in future research on OGM and its associated processes.

Research on OGM and its mechanisms in individuals with chronic pain is still very much in its infancy (see for a CaRFAX model proposed to explain the development of CPSP). Moreover, not one longitudinal study or pediatric study has been published on the subject. A recent cross-sectional study by Liu et al.Citation129 compared a sample of 331 adults with chronic pain to 333 healthy controls on their performance on the AMT and Working Memory Index. Participants with chronic pain scored significantly lower on memory specificity and on working memory. Working memory scores also mediated the relationship between pain and OGM. In addition, the study of individuals with fibromyalgia that assessed self-defining autobiographical memoriesCitation97 found that along with an OGM bias, patients’ memories incorporated less personal significance, were less likely to shift from negative to positive affect, and were more negative but less intense than those of healthy controls.Citation97 Altogether, these results were interpreted to reflect a distorted sense of self fueled by functional avoidance of specific memories.

Figure 1. CaRFAX Model in Chronic Postsurgical Pain. Processes of Capture and Rumination, Functional Avoidance and Issues with Executive Control are posited to, either independently or through interaction, lead to overgeneral memories (OGM) about prior pain-related experiences. According to this model, individuals who develop a consistent OGM bias have poorer prospects for recovery and worse pain trajectories after undergoing major surgery. The development of chronic postsurgical (CPSP) reinforces negative cognitive patterns, emotional states, and other mental health issues consistent with processes involving rumination about pain-related topics, avoidance of detailed aspects of pain-related memories, and executive control issues (e.g., working memory, attentional control and behaviours, inhibition, shifting, and self-regulation), all of which facilitate a positive feedback loop that maintains overgeneral memory and ultimately, chronic pain. Adapted with permission from Williams.Citation115

Though the CaRFAX model has not been evaluated in children with chronic pain, some of the processes that comprise the model have been shown to play an important role in pediatric patients with acute pain postsurgery. Pain catastrophizing, defined as rumination about, magnification of the threatening aspects of, and feelings of helplessness in the face of pain, is a psychological risk factor for CPSP in children.Citation130–132 Noel et al.Citation76 examined the role of pain catastrophizing in the development of children’s and parents’ memories for pain after pediatric major surgery (e.g., spinal fusion, pectus repair) using a longitudinal design. The results showed that parents’ catastrophizing, specifically magnification and rumination about their child’s pain, predicted children’s negatively biased memories for pain-related distress and parents’ negatively biased memories for children’s initial pain intensity, respectively. Moreover, though parents’ catastrophizing directly correlated with pain memories, children’s pain catastrophizing did not have a direct association with their own or their parents’ pain memories. Rather, children’s preoperative helplessness about pain was indirectly related to their own and their parents’ pain memories through the mediating effect of children’s emotional distress during the acute recovery period. Additionally, parents’ ruminations about their child’s pain correlated with greater pain intensity in the child during the acute postsurgical period, which in turn was associated with children developing more distressing memories of their pain. Parents’ trait anxiety has previously been shown to predict more negatively biased memories for pain-related fear in children even when the child’s own preoperative anxiety did not.Citation133 As such, these findings emphasize the need to assess parents’ own affective states and memories of pain when investigating these factors in pediatric populations.

Child and parent pain catastrophizing has also been shown to be associated with children’s pain-related attention and avoidance behaviors.Citation134 In a sample of healthy children, those who reported greater pain magnification and whose parents reported greater rumination and helplessness were more likely to divert attention away from pain faces. Moreover, these children with higher attentional avoidance showed greater behavioral avoidance, determined by their lower pain tolerance during a cold pressor task. Prior work has also found subclinical deficits in executive functioning on neuropsychological measures in adolescents with chronic pain, where pain catastrophizing was found to relate to working memory and sustained attention.Citation135 Indeed, alterations in executive functioning are well established in youth with chronic pain. A recent study showed that relative to healthy controls, adolescents with chronic pain between the ages of 13 and 17 years scored significantly lower on neuropsychological tests and behavioral measures for working memory and divided attention, alternating attention, inhibition, and cognitive and emotional regulation.Citation136 Previous research has also demonstrated that one’s social context can interact with attention to affect negatively biased memories for pain. In a study with healthy children, longer fixation on pain faces in an eye-tracking task was associated with an overestimation of pain-related fear assessed 2 weeks after the child completed a painful cold pressor task.Citation137 Importantly, this relationship was moderated by lower levels of parental verbalizations that did not focus on the child’s pain. Based on these findings, the authors suggested that parent and child factors should be studied in tandem when considering memory biases that emerge in chronic pain.

In light of these findings and what is known about the psychological effects associated with chronic pain in children, it is possible that similar CaRFAX mechanisms observed in adult OGM exist in children undergoing surgery. A worthwhile avenue of future pediatric research in CPSP would be to elucidate the role of OGM and its associated mechanisms, as well as the interactions between them. There is a need to explore the prospective relationship between these CaRFAX elements and chronic pain and for prospective studies to address whether this model applies to nonclinical, at-risk adult and child populations who have not yet developed chronic pain, such as those undergoing surgery or with injuries. Also of importance for future research, considering the complex interplay among these processes, would be to assess parental (and sibling) cognitive–affective factors in relation to children’s own cognitive, psychological, and memory characteristics.

Biases in Autobiographical Memory Content Related to Pain and Surgery

Cross-sectional studies on autobiographical memory in adults have found that individuals with various chronic pain conditions tend to recall more pain-related contentCitation95,Citation138 and exhibit a bias in which they recall memories with more negative emotional valence.96,Citation140,141 In regard to valence, it has been suggested by some that it is current pain, not chronic pain per se, that contributes to negative emotionality.Citation139 An early study by Wright and MorleyCitation138 found that in a small sample of patients with chronic pain, memories including pain-related information were accessed more quickly by patients than in healthy controls. In addition, as previously mentioned, self-defining autobiographical memories in patients with fibromyalgia were more negative but less intense than those of healthy controls.Citation97 Unlike the other studies, individuals did not differ in the amount of pain-related content. A prospective longitudinal study conducted by Waisman et al.Citation98 assessed autobiographical memory using the AMT in adults undergoing major surgery. One of the results of this study showed that relative to individuals who produced fewer memories, those who recalled more memories with surgery-related content 1 month after surgery were more likely to develop pain up to a year later. Taken together, these findings implicate a mood congruency effect in individuals with chronic pain similar to that observed in people with emotional disorders,95,139,140 where one’s current affective state enables less effortful access to memories of similar content and emotionality.Citation141

Memory and Identity in the Context of Chronic Pain

According to the self-memory system theory, an individual’s goals and self-representations guide memory retrieval toward cognitively and emotionally compatible information.Citation99 Evidence for this model largely stems from research in which individuals with various mental health disorders show a bias for recalling memories and imagining future events that match their current mood states.Citation100 Recent findings that people with chronic pain tend to generate pain-related information when remembering the past and imagining the future further indicate that these biases might extend beyond memory and have important implications for well-being.Citation95

Consistent with this line of thought, pain enmeshment theoryCitation114 proposes that an individual’s emotional adjustment to pain depends on the extent to which aspects of their self-image are “enmeshed” or intertwined with pain. This model originated from the observation that individuals with chronic pain, who also show substantial associated distress, tend to exhibit cognitive biases in attention, memory, and interpretation processes. The authors posited that these biases were the result of an overlap between the self, pain, and illness schemas. Support for these cognitive biases in youth with chronic pain is mixed.Citation142 Very few studies have investigated pain-related attentional biases in this population and findings are equivocal, in some cases identifying increased attendance to pain-related stimuliCitation143,Citation144 and in others failing to observe any attentional bias.Citation145 Discrepancies in findings between studies, especially in regard to memory biases, might in part be attributable to methodological problems where measures used to capture these abilities in adults are not always appropriate for children or adolescents (e.g., recalling word lists, as is often done in adults, as opposed to actual pain experiences, which would be more appropriate for younger individuals).Citation142 However, identity development in adolescents is linked to chronic pain in complicated ways. For example, chronic pain can rob young people of their individuality or, conversely, provide them with reasons to identify more strongly with unique characteristics of themselves that are unrelated to their diagnosis.Citation146 Whereas some adolescents might experience a growth in emotional maturity as a result of living with chronic pain, others feel deprived of their sense of autonomy.Citation146 Pain enmeshment theory was later expanded using the framework of self-discrepancy theory,Citation147,Citation148 which postulates that individuals self-regulate to account for discrepancies between different aspects of the self; namely, the actual self (aspects of the self as they currently are), the ideal self (aspects of the self as one would like them to be), and the ought self (aspects of the self that one thinks they should have). According to this model, discrepancies between the actual and ideal self are expected to lead to depression, whereas disparities between the actual and ought self lead to agitation. The authors suggested that individuals living with chronic pain are more likely to experience emotional maladjustment when they view pain as the reason why they cannot attain their desired selves. This notion was later tested and supported by Morley et al.Citation149 in a study of 89 adults with chronic pain who reported characteristics of their current self, their hoped-for self, and their feared-for self. Participants also reported the extent to which their future selves depended on the presence or absence of pain. The results showed that the number of characteristics of the hoped-for self that were deemed attainable even in the presence of pain was negatively correlated with depression and positively correlated with pain acceptance scores.Citation149 Thus, the more accepting a person was of their pain, the less the pain interfered with a positive self-image. Similar findings emerge in adolescents with chronic pain who tend to generate more negative affect, insight, and self-discrepancy words when describing their imagined future.Citation150

Intervention Prospects

The literature reviewed above highlights an important role for autobiographical memory biases in the development of CPSP, which, if causal, could have important implications for pre- and postsurgical intervention strategies. In terms of memory specificity, pain management programs involving cognitive therapies could focus on altering patients’ retrieval styles to focus more on specific rather than general pain-related memories. From a preventive standpoint, individuals undergoing major surgery who are at risk of chronic pain might benefit from completion of these specificity-enhancing interventions in the period before or acutely after surgery before pain becomes chronic. Memory Specificity Training (MeST) is one example of a validated intervention program that shows promise for the prevention and treatment of mental health disorders through memory modification.Citation151,Citation152 The program uses cued recall to reframe individuals’ memories to be more specific while inhibiting generalization. It is typically conducted in a group format and incorporates psychoeducation sessions about autobiographical specificity and situational factors that impede specificity. MeST improves autobiographical memory specificity and, to a lesser extent, reduces symptoms of depression. In a distressed sample of 23 bereaved adolescent Afghan refugees, it was found that even after controlling for depression scores, MeST significantly enhanced autobiographical memory specificity relative to a passive control group.Citation153 The bereaved individuals also had significantly fewer depressive symptoms at a 2-month follow-up session relative to controls. A meta-analysis by Barry et al.Citation151 concluded that MeST is associated with substantial benefits such as improved problem-solving and lower hopelessness. However, to date, MeST results have been short-lived and often not sustained at follow-up.

Though preferentially retrieving overgeneralized knowledge at the expense of specific memories unequivocally leads to poorer mental health and well-being, the ability to recall abstract memories in and of itself is beneficial and even essential.Citation151 Abstracting knowledge into schematic representations and drawing on reserves of positive and negative experiences facilitates the acquisition of important life lessons that ultimately shape identity formation and guide decision making.Citation151,Citation154 Memory Flexibility Training is an intervention that builds on this premise by training participants to efficiently switch between specific and nonspecific memories within the MeST paradigm.Citation155 Overall, Memory Flexibility Training has been found to be effective for ameliorating symptoms in individuals with major depressive disorder and PTSD.Citation155–158

Another experimental episodic specificity induction also led to improved well-being across various measures.Citation159 Individuals undergoing the specificity induction showed significant improvements in means-ends problem solving by engaging in more relevant steps compared to those who completed a control induction.Citation160 Additionally, individuals in the induction group showed larger decreases in anxiety for worrisome future events, improved outlook on potential outcomes, and decreased perceived difficulty coping with negative outcomes.

In sum, specificity training appears to have beneficial outcomes for memory and a host of other processes essential to daily functioning and well-being. If autobiographical memory specificity is indeed discovered to be a causal factor for the development of CPSP, these forms of training could have important implications for health and pain outcomes in individuals undergoing surgery. Youth with chronic pain who have comorbid mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, and PTSD are known to be at higher risk for worsening painCitation161–165 and poorer responsiveness to pain-related interventions.Citation130,Citation166–168 By simultaneously targeting chronic pain and other mental health problems, memory specificity training could prove to be an effective method for optimizing treatment outcomes. However, to effectively target co-occurring mental health disorders and the underlying processes that initiate or maintain both conditions, a “one-size-fits-all” approach is insufficient and tailored treatments are necessary. For this reason, future research should disentangle the unique contributions of OGM from other psychological factors that maintain chronic pain in order to facilitate identification of specific memory areas to target in individuals with diverse etiologies for their pain. An increased focus on autobiographical memory specificity can also be incorporated into psychotherapies that show efficacy for chronic pain from both preventative and treatment standpoints. Cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT) is an effective, commonly used modality for people living with chronic pain into which memory interventions can be easily integrated.Citation169 It may also be possible to enhance autobiographical memory specificity with mindfulness-based stress reduction, acceptance and commitment therapy, as well as other psychotherapy modalities. A key component of CBT for chronic pain involves cognitive restructuring in which individuals’ maladaptive cognitions are challenged, often by drawing on specific memories for evidence, and subsequently modified and replaced with more accurate representations of the self and the world. Particular attention can be paid to the episodic qualities of specific pain experiences when employing cognitive reframing techniques. Furthermore, specificity training could also be used to improve memory for the CBT sessions themselves, in order to enhance therapy outcomes.Citation170 Finally, because adults who undergo surgery and develop pain may have a self-concept centered around these experiences,Citation98,Citation114 psychotherapy interventions could also address the content of patients’ memories by reappraising maladaptive preoccupation, restructuring memories to be more positive or accurate, and setting goals for the future.

Directions for Future Research in Pediatric Chronic Postsurgical Pain

There is a pressing need for further pediatric research in several areas of autobiographical memory and chronic pain. shows a nonexhaustive list of some of the memory processes relevant to the pain literature along with common assessment measures and associated memory biases. Some of these memory types are specific to pain (negatively biased pain memories), whereas others are not (memory specificity and episodic richness) but nonetheless have relevance to people with chronic pain conditions.

Table 1. A nonexhaustive list of memory processes, assessment instruments, and biases warranting study in chronic postsurgical pain.

Prospective longitudinal designs would help to determine the temporal relationship between OGM and the onset of CPSP and elucidate whether autobiographical memory quality is a risk/protective factor for the condition. These results should also be validated using alternative methods. Most studies that investigate memory specificity, and almost all studies in chronic pain described above, assess OGM using some variation of the AMT. Though the AMT is a popular and reliable tool,Citation109,Citation171 it has certain limitations that should be taken into consideration and addressed in future research. First, the AMT is not considered sensitive to OGM in nonclinical populations without mental health conditions.Citation171 For example, expected correlations between AMT specificity and depression scores for nondepressed individuals have been shown to be absent and, in some cases, even positive.Citation109 It is thought that in clinically depressed individuals, an overgeneral style is the dominant mode of retrieval that, with time, becomes increasingly more difficult to inhibit. However, in cases where this cognitive pattern is less potent, it might be easier for individuals to overcome, especially when they are explicitly told to do so in the instructions.Citation109 As such, the typical AMT task would fail to capture these sorts of at-risk individuals.

The Sentence Completion for Events from the Past Test is a more sensitive measure that was designed to address and circumvent these limitations.Citation109 However, both tasks still require participants to provide brief descriptions of a single event, typically within a short time interval. The lack of opportunity to elaborate yields descriptions that tend to be very short, often making it difficult for scorers to reliably interpret. Furthermore, responses are scored in a dichotomous fashion where whole memories are categorized as either specific or nonspecific. This approach treats episodic and semantic components of autobiographical memory as categorically distinct and isolated systems, artificially deconstructing whole responses as belonging to either one or the other. Doing so neglects the natural co-occurrence of these two components during discourse and is not consistent with neurocognitive theories that emphasize their interdependence.Citation15 Therefore, a better alternative would be to use tasks such as the Autobiographical Interview/Children’s Autobiographical InterviewCitation56,Citation172 that allow for elaborative, free recall and more nuanced scoring techniques that segment, categorize, and quantify details pertaining to both types of memory within a single autobiographical narrative. Such an approach could provide a more informative look into the relative patterns of deficits and preservation in individuals’ pain memories in future research. If differences in the degree of episodicity exist, the underlying mechanisms driving this relationship would warrant further investigation. Based on research in adult samples with emotional disorders, CaRFAX mechanisms of rumination, avoidance, and executive functioning are compelling starting points for future studies in youth. Primarily, it is of interest to examine whether these mechanisms can explain OGM in pediatric CPSP and, if so, whether they are also meaningful contributors in nonclinical or at-risk samples. Given developmental differences in memory and other aspects of cognitive and psychological development, age is an important factor to take into consideration. Pairing this method of memory narrative elicitation with the more common approach of comparing recall to initial pain reports using single-item pain scales is important because it would further our understanding of the relationship between OGM and negative memory biases and, as a result, contribute a more nuanced model of memory bias in CPSP.

Though the literature on parent–child reminiscing demonstrates robust effects of parents’ elaboration reminiscing styles on children’s emotional adjustment and pain memories, to our knowledge, there is no research on how the quality of parents’ autobiographical memories about pain or surgery might influence the recollection styles and well-being of their children. A possible line of investigation could involve examining parents’ and children’s narratives of their own painful and surgical experiences to assess whether the ways in which children process these events relate to their parents’ narrative styles. Similarly, it would be interesting to compare parents’ and children’s memory descriptions of the child’s surgical experience and to relate the degree of specificity and content in each of their recollections to the child’s postsurgical pain outcomes.

Finally, considering the utility of autobiographical memory in other cognitive, emotional, and social functions, future research could explore how these other domains are affected in chronic pain, particularly in child and surgical patients. It is possible that certain differences might be observed in abilities that are known to necessitate intact episodic autobiographical memory processing in adults, such as future imagination and problem solving.Citation16,Citation29 These functions are integral to establishing feelings of self-efficacy and maintaining a stable sense of self, especially in times of hardship; they enable individuals to set goals and envision attainable and positive futures for themselves. Within the context of pain, the common disruption of these functions severely hinders patients’ abilities to lead a full life and recover from their afflictions. As such, understanding relative difficulties in these areas could help identify new treatment targets and guide efforts aimed at preventing and managing children’s postsurgical pain.

Summary and Highlights

The accuracy with which youth remember sensory and affective components of painful events has been shown to predict their postsurgical pain outcomes.Citation5,Citation6

Psychosocial factors play an important role in the relationship between memory for pain and postsurgical outcomes, including the individual’s own psychological factors, as well as the familial context in which youth reminisce about, and more generally discuss, their painful experiences.6,75,83,86

An area of study in pain research that has largely been neglected concerns the spatiotemporal specificity and phenomenal characteristics of individuals’ autobiographical memories. In addition to showing preoccupations with pain-related content and differences in memory valence, a handful of recent cross-sectional studies in adults has identified an overgeneral memory bias among individuals with chronic pain, whereby autobiographical memories are devoid of specific events.94,95,97,130

One prospective, longitudinal study found autobiographical memory specificity to protect against the development of chronic postsurgical pain in adults.Citation98

We call on future research to investigate these processes in pediatric populations. If found to be consistent with the adult literature, the study of memory biases and memory processes could point to an important new avenue for prevention or treatment strategies in individuals vulnerable to developing or living with chronic postsurgical pain, respectively.

Concluding Remarks

Memory biases for pain-related experiences robustly predict pain outcomes in children undergoing major surgery. Thus far, a predominant focus in the literature has been on children’s recall for prior pain assessed using self-report pain ratings and the influence of these memories on future pain trajectories. Recollections of postsurgical pain being more intense than originally reported predict worse long-term pain outcomes for children and adolescents. However, a newly emerging line of inquiry in the study of chronic pain concerns the quality of autobiographical memories themselves. Still in its early stages, cross-sectional work has identified alterations in the specificity and content of autobiographical memories in individuals with chronic pain. Moreover, a recent prospective study found that highly generalized personal memories about pain that were generated before surgery as well as preoccupations with surgery in postoperative recollections predicted the development of CPSP in adults up to 1 year after surgery. These findings indicate an important relationship between the tendency to recollect memories that lack specificity and the initiation or maintenance of chronic pain after a stressful life event like major surgery. Our recommendation is to investigate these mechanisms in pediatric populations undergoing surgery. If similar patterns exist, memory-based interventions could prove effective in the effort to prevent lifelong transmission of chronic pain. It will also be important to link the various memory biases to alterations in hippocampal structure and functioning given this brain region’s pivotal role in the processing and maintenance of autobiographical memory as well as its similar, more recently discovered function in chronic pain. These relationships should be assessed in conjunction with other common cognitive biases pertaining to attention and interpretation, because they might be implicated in pediatric chronic pain as well. Finally, considering the important role of socialization, and especially parental socialization, in children’s processing of distressful and painful information, research into parents’ and children’s narrative styles could further elucidate memory-driven contributions to CPSP. In the more than 40 years since the term “pain memory” was coined, it has evolved to describe a heterogeneity of memory biases observed in chronic pain. Appreciating these multifaceted conceptualizations can aid us in developing a more complete picture of the phenomenon and, it is hoped, advance our goal of preventing children’s postsurgical pain from becoming chronic.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Dennis SG, Melzack R. Self-mutilation after dorsal rhizotomy in rats: effects of prior pain and pattern of root lesions. Experimental Neurology. 1979;65(2):412–421. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-4886(79)901080)901080

- Katz J, Melzack R. Pain “memories” in phantom limbs: review and clinical observations. PAIN. 1990;43(3):319–336. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(90)90029D)90029D

- Redelmeier DA, Katz J, Kahneman D. Memories of colonoscopy: a randomized trial. PAIN. 2003;104(1–2):187–194. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3959(03)000034)000034

- Noel M, Chambers CT, McGrath PJ, Klein RM, Stewart SH. The influence of children’s pain memories on subsequent pain experience. PAIN. 2012;153(8):1563–1572. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2012.02.020

- Noel M, Rabbitts JA, Fales J, Chorney J, Palermo TM. The influence of pain memories on children’s and adolescents’ post-surgical pain experience: A longitudinal dyadic analysis. Health Psychology. 2017;36(10):987–995. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000530

- Noel M, Rosenbloom B, Pavlova M, Campbell F, Isaac L, Pagé MG, Stinson J, Katz J. Remembering the pain of surgery 1 year later: a longitudinal examination of anxiety in children’s pain memory development. PAIN. 2019;160(8):1729–1739. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001582

- Schug SA, Lavand’homme P, Barke A, Korwisi B, Rief W, Treede R-D, IASP Taskforce for the Classification of Chronic Pain. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic postsurgical or posttraumatic pain. PAIN. 2019;160(1):45–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001413

- Fortier MA, Chou J, Maurer EL, Kain ZN. Acute to chronic postoperative pain in children: preliminary findings. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2011;46(9):1700–1705. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.03.074

- Pagé MG, Stinson J, Campbell F, Isaac L, Katz J. Identification of pain-related psychological risk factors for the development and maintenance of pediatric chronic postsurgical pain. Journal of Pain Research. 2013;6:167–180. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S40846

- Sieberg CB, Simons LE, Edelstein MR, DeAngelis MR, Pielech M, Sethna N, Hresko MT. Pain prevalence and trajectories following pediatric spinal fusion surgery. The Journal of Pain. 2013;14(12):1694–1702. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2013.09.005

- Price TJ, Basbaum AI, Bresnahan J, Chambers JF, De Koninck Y, Edwards RR, Ji R-R, Katz J, Kavelaars A, Levine JD, et al. Transition to chronic pain: opportunities for novel therapeutics. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 2018;19(7):383–384. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-018-0012-5

- Tulving E. Episodic and semantic memory. In: Tulving, E., Donaldson, W. editors. Organization of memory. Oxford, England: Academic Press; 1972. p. xiii, 423–xiii, 423.

- Tulving E. Episodic memory: from mind to brain. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:1–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135114

- Greenberg Daniel L, Verfaellie M. Interdependence of episodic and semantic memory: Evidence from neuropsychology. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2010;16(5):748–753. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617710000676

- Svoboda E, McKinnon MC, Levine B. The functional neuroanatomy of autobiographical memory: a meta-analysis. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44(12):2189–2208. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.05.023

- Addis DR, Wong AT, Schacter DL. Remembering the past and imagining the future: common and distinct neural substrates during event construction and elaboration. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45(7):1363–1377. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.10.016

- Jing HG, Madore KP, Schacter DL. Worrying about the future: An episodic specificity induction impacts problem solving, reappraisal, and well-being. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General. 2016;145(4):402–418. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000142

- Pillemer DB, Wink P, DiDonato TE, Sanborn RL. Gender differences in autobiographical memory styles of older adults. Memory. 2003;11(6):525–532. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210244000117

- Schacter DL, Addis DR. The cognitive neuroscience of constructive memory: remembering the past and imagining the future. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2007;362(1481):773–786. doi:https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2007.2087

- Sheldon S, Vandermorris S, Al-Haj M, Cohen S, Winocur G, Moscovitch M. Ill-defined problem solving in amnestic mild cognitive impairment: Linking episodic memory to effective solution generation. Neuropsychologia. 2015;68:168–175. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.01.005

- Wilson AE, Ross M. From chump to champ: People’s appraisals of their earlier and present selves. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80(4):572–584. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.80.4.572

- Bluck S, Alea N. Remembering being me: The self continuity function of autobiographical memory in younger and older adults. In: Sani, F, editor. Self continuity: Individual and collective perspectives. NewYork, NY, US: Psychology Press; 2008. p. 55–70.

- Conway MA. Memory and the self. Journal of Memory and Language. 2005;53(4):594–628. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2005.08.005

- Alea N, Bluck S. I’ll keep you in mind: The intimacy function of autobiographical memory. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2007;21:1091–1111. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1316

- Alea N, Bluck S. Why are you telling me that? A conceptual model of the social function of autobiographical memory. Memory. 2003;11:165–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/741938207

- Williams JMG, Barnhofer T, Crane C, Herman D, Raes F, Watkins E, Dalgleish T. Autobiographical memory specificity and emotional disorder. Psychological Bulletin. 20070103;133(1):122. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.122

- Madore KP, Addis DR, Schacter DL. Creativity and memory: Effects of an episodic-specificity induction on divergent thinking. Psychological Science. 2015;26(9):1461–1468. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615591863

- Roberts RP, Addis DR. A common mode of processinggoverning divergent thinking and future imagination. In: Jung, RE, Vartanian, O, editors. The Cambridge handbook of the neuroscience of creativity. NewYork, NY, US: Cambridge University Press; 2018. p. 211–230. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316556238.013

- Peters SL, Fan CL, Sheldon S. Episodic memory contributions to autobiographical memory and open-ended problem-solving specificity in younger and older adults. Memory & Cognition. 2019;47(8):1592–1605. doi:https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-019-00953-1

- Bartlett FC. Remembering: A study in experimental and social psychology. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press; 1932. p. xix, 317.

- Bernstein DM, Loftus EF. The consequences of false memories for food preferences and choices. Perspectives on psychological science. 2009;4(2):135–139. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01113.x

- Loftus EF, Miller DG, Burns HJ. Semantic integration of verbal information into a visual memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Learning and Memory. 1978;4(1):19–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.4.1.19

- Schacter DL. Searching for memory: The brain, the mind, and the past. New York, NY, US: Basic Books; 1996. p. xiii, 398.

- Alba JW, Hasher L. Is memory schematic? Psychological Bulletin. 1983;93(2):203–231. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.93.2.203

- Schacter DL, Guerin SA, St. Jacques PL. Memory distortion: an adaptive perspective. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2011;15(10):467–474. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2011.08.004

- Bransford JD, Johnson MK. Contextual prerequisites for understanding: Some investigations of comprehension and recall. Journal of Verbal Learning & Verbal Behavior. 1972;11(6):717–726. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(72)800069)800069

- Craik FIM, Tulving E. Depth of processing and the retention of words in episodic memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1975;104(3):268–294. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.104.3.268

- Bruck M, Ceci S. The suggestibility of children’s memory. Annual Review of Psychology. 1999;50:419–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.419

- McClelland JL, McNaughton BL, O’Reilly RC. Why there are complementary learning systems in the hippocampus and neocortex: insights from the successes and failures of connectionist models of learning and memory. Psychological Review. 1995;102(3):419–457. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.102.3.419

- Piolino P, Hisland M, Ruffeveille I, Matuszewski V, Jambaqué I, Eustache F. Do school-age children remember or know the personal past? Consciousness and Cognition. 2007;16(1):84–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2005.09.010