ABSTRACT

Introduction/Aim

Primary care providers (PCPs), who provide the bulk of care for patients with chronic noncancer pain (CNCP), often report knowledge gaps, limited resources, and difficult patient encounters while managing chronic pain. This scoping review seeks to evaluate gaps identified by PCPs in providing care to patients with chronic pain.

Methods

The Arksey and O’Malley framework was used for this scoping review. A broad literature search was conducted for relevant articles on gaps in knowledge and skills of PCPs and in their health care environment for managing chronic pain, with multiple search term derivatives for concepts of interest. Articles from the initial search were screened for relevance, yielding 31 studies. Inductive and deductive thematic analysis was adopted.

Results

The studies included in this review reflected a variety of study designs, settings, and methods. However, consistent themes emerged with respect to gaps in knowledge and skills for assessment, diagnosis, treatment, and interprofessional roles in chronic pain, as well as broader systemic issues including attitudes toward CNCP. A general lack of confidence in tapering high dose or ineffective opioid regimes, professional isolation, challenges in managing patients with CNCP with complex needs, and limited access to pain specialists were reported by PCPs.

Discussion/Conclusions

This scoping review revealed common elements across the selected studies that will be useful in guiding creation of targeted supports for PCPs to manage CNCP. This review also yielded insights for pain clinicians at tertiary centers for supporting their PCP colleagues as well as systemic reforms required to support patients with CNCP.

RÉSUMÉ

Introduction/Objectif: Les prestataires de soins primaires, qui fournissent la majeure partie des soins aux patients souffrant de douleur chronique non cancéreuse, font souvent état de lacunes dans leurs connaissances, de ressources limitées et de rencontres difficiles avec les patients dans le cadre de la prise en charge de la douleur chronique. Cet examen de la portée vise à évaluer les lacunes identifiées par les prestataires de soins primaires dans la prestation de soins aux patients souffrant de douleur chronique.

Méthodes: Le cadre d’Arksey et O’Malley a été utilisé pour cet examen de la portée. Une vaste recherche documentaire a été menée pour trouver des articles pertinents sur les lacunes dans les connaissances et les compétences des prestataires de soins primaires et dans leur environnement de soins de santé pour la prise en charge de la douleur chronique, avec de multiples dérivés de termes de recherche pour les concepts d’intérêt. Les articles de la recherche initiale ont été examinés pour leur pertinence, ce qui a donné 31 études. L’analyse thématique inductive et déductive a été adoptée.

Résultats: Les études incluses dans cette revue reflétaient une variété de devis, de milieux et de méthodes d’étude. Cependant, des thèmes récurrents ont émergé en ce qui concerne les lacunes dans les connaissances et les compétences concernant l’évaluation, le diagnostic, le traitement et les rôles interprofessionnels dans la douleur chronique, ainsi que des problèmes systémiques plus larges, y compris les attitudes à l’égard de la douleur chronique non cancéreuse. Un manque général de confiance dans les traitements opioïdes à dose élevée ou inefficaces, l’isolement professionnel, les difficultés de prise en charge des patients atteints de douleur chronique non cancéreuse ayant des besoins complexes et l’accès limité aux spécialistes de la douleur ont été signalés par les prestataires de soins primaires.

Discussion/Conclusions: Cet examen de la portée a révélé des éléments communs aux études sélectionnées qui seront utiles pour guider la création de soutiens ciblés pour les prestataires de soins primaires dans le cadre de la prise en charge de la douleur chronique non cancéreuse. Cette revue a également fourni des informations aux cliniciens de la douleur des centres tertiaires pour soutenir leurs collègues prestataires de soins primaires ainsi que les réformes systémiques nécessaires pour soutenir les patients atteints de douleur chronique non cancéreuse.

Introduction

Significance of Primary Care in Treating Chronic Pain

Family physicians, general practitioners, nurse practitioners (NPs), clinical nurse specialists, and physician assistants are all considered primary care providers (PCPs)Citation1 and are often the first point of contact for the majority of patients with chronic noncancer pain (CNCP) in Canada. CNCP is generally defined as pain persisting beyond the normally expected time for healing, with 3 months as the typical threshold for a diagnosis of chronic pain.Citation2 Given that nearly one in five individuals in Canada experience CNCP, treating pain is a significant proportion of the care delivered by PCPs.Citation3–9 These providers offer an early point of contact with the health care system for patients with chronic pain; they provide comprehensive care, and they can also identify patients who are in need of specialist care.Citation10 With the increasing complexity of primary care and expectations of stronger opioid stewardship since the 2017 Canadian Guidelines for Opioid Therapy and Chronic Noncancer PainCitation11 publication, a need to assess the challenges faced by PCPs in providing the bulk of care to patients living with CNCP exists.

Background

PCPs often receive inadequate education and training in treating and managing chronic pain.Citation12–14 Even those PCPs who receive exposure to diagnosing and treating chronic pain may find it difficult to translate this knowledge into optimal outcomes for a multitude of reasons, including lack of reliable and objective measures of pain, concerns about adverse effects of analgesic treatments, and limitations in contact time with patients.Citation15–17 It is therefore not surprising that individuals experiencing CNCP often feel that their complaints are addressed with skepticism, lack of understanding, rejection, belittlement, or blame or labeled with diagnoses such as somatic symptom disorder that implies that their pain is a psychological construct.Citation18 Health care professionals struggle to understand the subjective nature of pain, often finding difficulty in correlating pain complaints with objective findings on physical examination and investigations, and have difficulty empathizing with patients’ suffering when secondary gain may be a consideration.Citation19 Further, fears of contributing to opioid dependence and causing harm to patientsCitation19 are relevant concerns in the management of CNPC. Prescribing of opioids in high doses, a practice more prevalent in the past that continues to cast a shadow in current management of CNCP, is now known to carry significant risks and complications and adds complexity in CNCP care.Citation20

PCPs are often expected to provide comprehensive CNCP care regardless of whether their training has equipped them with the tools to do so.Citation21 This can lead to professional frustration and less-than-ideal outcomes for patients with CNCP.Citation22 Medical and nursing schools historically have not allocated significant time to teach assessment and management of pain, which has resulted in suboptimal knowledge and skill levels of PCPs treating patients with CNCP, a problem that potentially compromises patient care.Citation21

Rationale for This Review

Though the Pain Medicine specialty training program of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of CanadaCitation23 is a welcomed new addition to the postgraduate training landscape, access to advanced pain specialists historically has been limited, and the bulk of chronic pain management is delivered by PCPs.Citation24 There is a current need to understand the challenges faced by PCPs after the recent substantive shift in opioid prescribing practices, the concurrent growth of pain medicine, and the present impetus to advance care for CNCP in Canada with the recent release of the Canadian Pain Task Force recommendations.Citation25

Aims

The broad aims of this scoping review were to provide an overview of the perspectives of Canadian PCPs in managing CNCP, identify gaps in the existing literature, and explore the potential to use the results of this review in the future to guide continuing medical education curricula and other supports for PCPs.Citation26,Citation27

We considered a scoping review of literature followed by a discussion of the available evidence as appropriate for this topic. Scoping reviews seek to map emerging literature in terms of its volume, nature, and characteristics. In contrast to systematic reviews, scoping reviews do not answer a focused research question.Citation26 Scoping reviews further differ from systematic reviews in that they address broader topics in which different study designs may be applicable, and thus the heterogeneous nature of available literature on this subject justifies this approach of synthesizing evidence.Citation28 Furthermore, though a scoping review has been done on PCP opioid prescribing safety measures,Citation29 also covered in part by various publications at different time points and in multiple regions of Canada, this subject has not yet been extensively reviewed. Our review is therefore one of the first comprehensive syntheses to assimilate evidence on primary care perspectives on the management of CNCP pain.

Materials and Methods

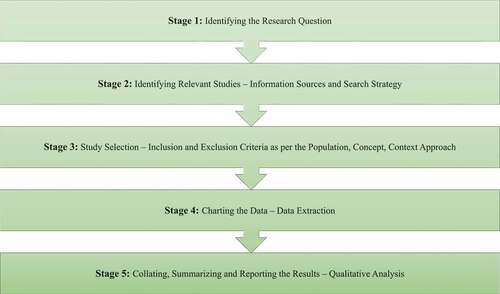

This scoping review was informed by the framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley,Citation26 which was updated by Levac and colleagues.Citation27 We conducted this review as per the five stages of the Arksey and O’Malley framework: identifying the research question (stage 1), identifying relevant studies (stage 2), study selection (stage 3), charting the data (stage 4), and collating, summarizing, and reporting the results (stage 5; ).Citation26 The reporting of this scoping review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Scoping Reviews guidelines.Citation30 The focus of this review was on comprehensiveness rather than depth, as recommended for scoping reviews.Citation26 This scoping review relies on published research in the public domain and therefore did not require research ethics board review; because it also does not include living human participants, this exempted the need for informed consent.

Stage 1: Identifying the Research Question

The primary objective of this review was to identify gaps reported by PCPs in managing CNCP, which included knowledge and skills but also systemic barriers and overarching attitudes and beliefs around CNCP. The secondary objective was to identify approaches reported for addressing these gaps with knowledge translation strategies, approaches to change attitudes and beliefs about people living with CNCP, and examining ways in which tertiary pain centers can optimize shared care of patients with PCPs.

Stage 2: Identifying Relevant Studies—Information Sources and Search Strategy

The information specialist (M.F.E.) conducted a systematic search of the following databases from their inception via the Ovid platform: MEDLINE ALL (1946–), Embase Classic/Embase (1947–), Cochrane Central Registry of Controlled Trials (1995–), and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2005–). CINAHL Complete (via the EbscoHOST platform, 1982–) was also searched. The trial registries ClinicalTrials.Gov (National Institutes of Health) and World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Platform were also searched. Dissertations were sought using the ProQuest Digital Dissertations International database. Lastly, books or book chapters were sought using the UHN’s Summon OneSearch discovery service. All databases and trial registries were searched on the same day, January 2, 2020. Update searching over all databases and registries was conducted on May 12, 2021.

The search process followed the Cochrane HandbookCitation31 and the Cochrane Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention ReviewsCitation32 for conducting the search. The PRESS guideline for peer-reviewing the search strategies,Citation33 drawing upon the PRESS 2015 Guideline Evidence-Based Checklist, was used to avoid potential search errors.

To develop comprehensive search strategies, preliminary searches were conducted, and full-text literature was mined for potential keywords and appropriate controlled vocabulary terms (such as Medical Subject Headings for MEDLINE and EMTREE descriptors for Embase). The Yale MeSH AnalyzerCitation34 was used to facilitate the MeSH and text word analysis, using target citations provided by the team.

The search strategy concept blocks were built on the following topics: (primary care physicians or related terms) AND (chronic pain or related terms) AND (questionnaires or surveys or related terms) AND (Canada, including all provinces and territories) using both controlled vocabularies and text word searching for each component. Searches were limited to English language.

The Ovid MEDLINE ALL search strategy is provided in .

Supplemental Google Scholar searching was conducted by other members of the team, starting with the following search string: (“primary care physicians” OR “primary care doctors” OR “family physicians” OR “family doctors”) AND “chronic pain” AND (questionnaire OR survey) AND Canada. The first 200 resulting citations from Google Scholar were reviewed.

Lastly, team members also hand-searched reference lists of selected articles to identify additional potentially relevant articles.

Stage 3: Study Selection—Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

A population, concept, context approach was followed for this scoping review.Citation35 The population of interest included Canadian PCPs including family physicians, general practitioners, nurse practitioners, and their medical learners. Publications with allied health professionals and other medical specialties were included if a participant cohort was clearly identified as PCPs. Medical learners were included as a population that could provide insights into the base education of chronic pain care that PCPs then eventually rely upon in the absence of dedicated postgraduate training. We focused on studies only in the Canadian context given important differences between countries in health care systems, including at primary and tertiary levels, and in pain education curricula between Canada and other jurisdictions. The concepts of interest were gaps in the PCPs’ knowledge and skills, barriers in addressing CNCP, and/or reported strategies for improving CNCP management. The context was patients with CNCP including chronic pain in cancer survivors; studies on acute pain, cancer pain, and palliative care were excluded. Because the goal was foremost to understand the gaps and barriers experienced by PCPs, articles focused on patient perspectives were not included in this article, although these would be highly valuable for subsequent consideration as a separate review.

Eligible study designs were primary empirical studies, including qualitative studies, case reports, case series, observational studies (prospective, retrospective, and using questionnaires or surveys), randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, and conference abstracts. Editorials and opinion pieces were not included.

Abstracts identified within each search were imported into Rayyan, an evidence synthesis data management software, and duplicates were removed. Articles were screened independently by two reviewers (M.E. and V.M.), who reviewed titles and abstracts for relevance and eligibility. A subsequent full-text review of each article that passed the initial screening was completed independently and in duplicate, and conflicts were resolved through discussion, consensus, and input from the senior author (A.B.).

Stage 4: Charting the Data—Data Extraction

Data extraction tables were constructed and pilot-tested prior to use. Comprehensive extraction of the data into was performed and the accuracy of extracted data was verified by the first two authors (V.M., M.E.) independently. The data extracted and summarized in the table included study characteristics such as author, year, study type, number of participants, the setting/research theme, a summary of methods, and relevant results.

Table 1. A summary of studies on PCPs’ (family physicians, general practitioners, nurse practitioners, and medical learners) perceptions of gaps in treating chronic pain included in the review.

Stage 5: Collating, Summarizing and Reporting the Results—Qualitative Analysis

We adopted Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis for this scoping review.Citation37 Specifically, we performed a reflexive, semantic, inductive, and deductive approach, which will be explained herein. The authors remained reflexive of their social and diverse professional locations and how these backgrounds informed the research project, from conception to manuscript preparation. Semantic (the meaning in language) relationships between included articles’ concepts were explored. Data were coded inductively without an a priori conceptual framework, in keeping with our research aims to provide an overview of PCPs in managing CNCP and to identify gaps in the literature.Citation37 We subsequently deductively coded the data using the CanMEDS framework for discussion purposes and as a means by which to inform future education program development.

An iterative step-by-step thematic analysis was performed by two of the authors (V.M. and M.E.), where the included articles were first read in full in order to find patterns, followed by open coding of the data. Braun and Clarke defined a code as a “feature of the data (semantic content or latent) that appears interesting to the analyst and refers to ‘the most basic segment, or element, of the raw data or information that can be assessed in a meaningful way regarding the phenomenon.’”Citation38 These codes were subsequently grouped into categories, based on conceptual similarities, followed by grouping into emerging themes.Citation37 An iterative approach ensued where each reviewer subsequently ensured that each theme was coherent and representative of all of the data.Citation36 Subsequently, the two authors compared emerging themes and came to consensus on a common coding framework.Citation37 The common coding framework was subsequently applied to all articles included within this scoping review.Citation37

For credibility, confirmability, and dependability,Citation37,Citation39 the research team triangulated all independently coded emerging codes, subthemes, and themes to create the final coding book, and the senior author reviewed all codes, subthemes, and emerging themes, ensuring accuracy and consistency between the included manuscripts and the available literature.Citation40 The researchers also took memos throughout the research cycle to document reflections around data inclusion and analysis. Coding was iterative in nature, meaning that any newly emerging codes and themes were reviewed against all included articles, ensuring that data extraction was complete.

Results

Search Results

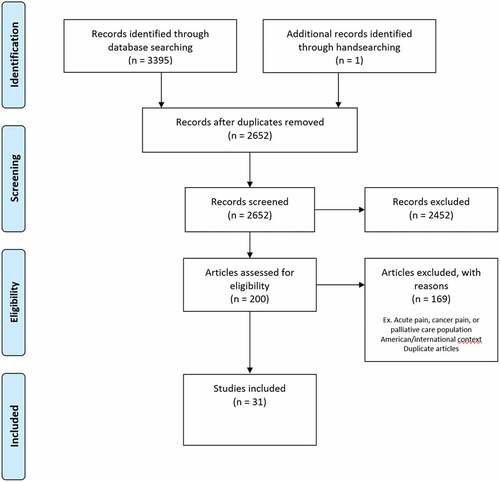

Our search strategy initially identified 3395 articles, and 743 of these articles were removed as duplicates. Another 2452 articles were excluded because of lack of relevance, and the full texts of the remaining 200 articles were assessed for eligibility based on the inclusion criteria previously outlined. Thirty-one of these articles, published between January 2006 and May 2021, met inclusion criteria for this scoping reviewCitation15–17,Citation20,Citation24,Citation41–66 (). It became apparent during initial article screening that some studies would have met the aforementioned inclusion criteria from the era of high-dose opioid prescribing in the 2000s, in which the medical literature at that time was critical of physicians hesitant to prescribe higher “therapeutic doses.” Education suggestions for PCPs from such studies often emphasized increasing opioids for CNCP beyond what would be accepted in current guidelines as best practice. The authors therefore decided that, in the present-day context, such studies would not contribute useful information to this scoping review. Three such studies were identified and excluded.Citation67–69

Characteristics of Included Studies

A summary description of studies included in this review is presented in . All of these studies represent Canadian PCPs surveyed or interviewed either in in-person workshops, in tele-conferences, by mail, or through online platforms. Of the 31 included studies, 10 (32%) used a qualitative study design,Citation15,Citation16,Citation20,Citation45,Citation46,Citation52,Citation54,Citation57,Citation60,Citation64 16 (52%) used a quantitative design (one randomized controlled trial,Citation48 one randomized experimental design,Citation65 14 cross-sectional surveys,Citation17,Citation24,Citation42,Citation43,Citation47–49,Citation53,Citation55,Citation56,Citation59,Citation61–63), and 5 (16%) studies used mixed methods.Citation41,Citation44,Citation51,Citation58,Citation66 All studies described the methods used to obtain data, and all but two studiesCitation46,Citation62 provided the number of participants. The number of PCP participants in these studies ranged from 6 to 710, for a total of 4389 PCPs out of 5063 participants. A subanalysis of included studies found that four of the included studies were penned by authors from Québec and focused exclusively on PCPs within Québec, with Quebec participants totaling 889, or 20% of the total PCPs captured by this scoping review.Citation16,Citation49,Citation56,Citation61 Additional difficulty in quantifying numbers of participants from Québec may have been captured in the 9 studies targeting PCPs across Canada, of which only 2 studies reported actual numbers of participants from Québec, capturing a further minimum of 77 PCPs from Québec, with likely additional unreported participants from Québec in the other pan-Canadian studies.Citation44,Citation59

All included studies explored PCPs’ perspectives on managing chronic pain. Eighteen articles focused exclusively on physicians’ perceptions,Citation15,Citation24,Citation42–46,Citation48,Citation50,Citation51,Citation53,Citation54,Citation56,Citation59,Citation61,Citation64–66 and one article focused exclusively on nurse practitioners’ perspectives.Citation47 The remaining articles discussed perspectives of family physicians, while also including nurse practitionersCitation20,Citation41,Citation60,Citation62,Citation63 and allied health care workers including physician assistants,Citation20,Citation41,Citation60 nurses,Citation16,Citation20,Citation22,Citation41,Citation54,Citation60 pharmacists,Citation16,Citation20,Citation41,Citation49,Citation58,Citation60 dentists,Citation58 social workers,Citation20,Citation41,Citation60 physiotherapists,Citation16,Citation20,Citation41,Citation60 occupational therapists,Citation20,Citation41,Citation60 psychologists,Citation16,Citation41 chiropractors,Citation41 kinesiologists,Citation41 and dietitians.Citation41 The PCPs in the studies ranged from recently graduated physicians and NPs to those with up to 49 years of experience.Citation41 Most geographical regions of Canada were represented, with nine studies surveying physicians all across CanadaCitation17,Citation24,Citation42,Citation44,Citation51,Citation59; other studies included participants from specific provinces: Newfoundland and Labrador,Citation64 Nova Scotia,Citation16,Citation46 British Columbia,Citation53 Alberta,Citation65 Saskatchewan,Citation62 Quebec,Citation16,Citation49,Citation56,Citation61 and Ontario.Citation15,Citation20,Citation41,Citation43,Citation45,Citation47,Citation48,Citation50,Citation52,Citation54,Citation57,Citation60,Citation63,Citation66

Methods of evaluation for the 21 quantitative and mixed methods studies included a questionnaire or a survey to obtain participant responses.Citation10,Citation17,Citation24,Citation41–44,Citation47–51,Citation53,Citation55,Citation56,Citation58,Citation59,Citation61–63,Citation66 The mixed methods studies allowed for open-ended responses on the questionnaires.Citation43,Citation44,Citation47,Citation51,Citation59 The study implementing a randomized controlled trial design with both groups completing a workshop and the intervention group receiving an additional 10 weeks of e-mail case discussions also used a blinded assessor postintervention to assess participants’ knowledge following the intervention.Citation51 Of the 10 studies employing a qualitative design, 5 used semistructured interviews,Citation15,Citation45,Citation46,Citation54,Citation64 3 used focus group interviews,Citation16,Citation20,Citation60 and 2 used an open-ended interview style.Citation52,Citation57

Unifying Themes in Studies

Eight common themes were identified and grouped under the following four overarching themes: pain medicine competencies and practice, interprofessional collaboration, attitudes and therapeutic relationship skills, and strategies to reduce gaps in care ().Citation48,Citation52,Citation55,Citation48,Citation52,Citation55,Citation58

Table 2. Scoping review inductive coding and emerging themes.

Theme I: Pain Medicine Competencies and Practices

Improving Pain Assessment and Appropriate Pharmacological Management

In general, both in surveys and with in-depth interviews, PCPs reported challenges with assessing painCitation49,Citation53 and navigating modalities of treatment for CNCP.Citation15,Citation45,Citation49,Citation51,Citation62,Citation64 PCPs described struggling with assessing and quantifying patients’ pain in the absence of clear biomarkers or imaging findings supporting a diagnosis of pain.Citation15,Citation49,Citation54,Citation57 Multiple studies included in this review found that validated scales to measure the intensity of pain were not universally employed.Citation15,Citation16,Citation24,Citation42,Citation49 PCPs also reported difficulty with proposing differential diagnoses for chronic pain syndromes.Citation56 However, PCPs acknowledged the importance of recognizing and treating common comorbidities associated with chronic pain, such as anxiety and depression.Citation15,Citation16,Citation42,Citation49,Citation54,Citation56

Standardized assessment tools and clinical practice guidelines, along with staff education and support for implementation, were considered helpful by NPs in managing painCitation16,Citation47; however, only 50% of NPs reported using clinical practice guidelines developed by other non–nurse practitioner health professional groups.Citation47 Despite awareness of existing tools and guidelines, many PCPs revealed in a semistructured interview that they had limited functional knowledge of or practice in using them.Citation16 An exception to this observation was awareness of opioid prescribing guidelines, which surveyed PCPs commonly reported implementing in their practice.Citation42,Citation59

Across studies, PCPs also reported uncertainty in executing a stepwise approach to pain management in choosing appropriate pain medications to prescribe to patients,Citation20,Citation44,Citation57 including determining when opioids were appropriate.Citation16,Citation20,Citation44,Citation49,Citation50,Citation56,Citation57 One survey assessed PCPs’ pharmacological knowledge in pain management and found that many clinicians were not aware of adverse effects of commonly used analgesics.Citation17 However, other surveys found that PCPs had concerns around overmedicating patients and adverse effects of medications, particularly in elderly patients and patients with cognitive impairments.Citation47,Citation49,Citation56

Advancing Opioid Prescribing Practices, Including Deprescribing Strategies

Transitions from pro-opioid CNCP Management Toward Deprescribing

The theme dominating PCPs’ practice challenges revolved around managing opioids for patients with CNCP. PCPs interviewed in two qualitative studies reported feeling unsupported in the transition from a time when opioids were recommended for treating CNCP to the current opioid crisis and guidelines recommending de-escalation of prescribed doses of opioids.Citation15,Citation57

Lack of knowledge and resources for opioid prescribing has translated into gaps in implementation of new guidelines and created new barriers in treating CNCP effectively. Some PCPs used a strict approach to opioid prescribing, including regimented use of opioid contracts and requiring objective evidence of pain as an indication to prescribe opioids, which was reported to complicate the provider–patient relationshipCitation15,Citation45,Citation46,Citation50,Citation56,Citation58 Despite guidelines supporting the practice of tapering opioids in patients who fail to achieve pain management goals with high doses of opioids, PCPs often did not take this approach,Citation15,Citation55 though some surveyed PCPs interpreted guidelines as mandating opioid tapering.Citation59 PCPs in several qualitative studies described challenges in deprescribing opioids in patients on high doses because patients often resisted this and expressed fear of exacerbation of their pain,Citation15,Citation20,Citation57,Citation59 and prescribers reported lack of knowledge in opioid deprescribing.Citation62,Citation64 PCPs interviewed also reported lacking appropriate knowledge and skill resources to assist patients in managing withdrawal symptoms during opioid tapers, often leading patients to return to previous high doses.Citation15 Many studies reported that being aware of the risks of opioid misuse increased PCPs’ hesitancy in prescribing themCitation15,Citation44,Citation45,Citation48,Citation55,Citation57; studies indicated that PCPs wanted more education on risks and benefits of various opioids,Citation15,Citation20,Citation49,Citation55,Citation57 and use of long-acting opioids elicited concerns from PCPs in one qualitative study about the risk of addiction despite lack of evidence that long-acting opioids increased risk of addiction compared to short-acting opioids.Citation45 PCPs also expressed concerns that some patients with CNCP tend to exaggerate pain in order to obtain opioids.Citation16,Citation49,Citation52,Citation57 Conversely, PCPs interviewed were more comfortable prescribing opioids when patients expressed anxiety or avoidant behavior with respect to starting opioids.Citation15 One PCP reported that “knowing the patient” strengthened their confidence that opioids may optimize function based on the patient’s beliefs around opioids, mental health comorbidities, and addiction risk.Citation15

There were some differences between the approach to prescribing opioids for less- and more-experienced PCPs. More-experienced PCPs reported recognizing their patients’ concerns and behaviors about opioids to reduce enforcement measures in opioid prescribing.Citation15,Citation45 Less-experienced PCPs reported more frequent use of the 2017 Canadian Guideline for Opioids for CNCP than more experienced PCPs,Citation15,Citation45,Citation57 exercising more caution initiating opioids, and expressed fear of disciplinary action from professional regulatory bodies for inappropriate prescribing.Citation15,Citation20,Citation55,Citation57 Several studies reported criticism of the Canadian guidelines for opioids due to the absence of strong evidence, clear and actionable strategies, and the unavailability of the recommended resources to support avoidance or the use of lower doses of opioids.Citation15,Citation45,Citation57,Citation59

Screening for Opioid Misuse

Surveys found that only 20% PCPs used validated tools to screen for the risk of opioid misuse prior to initiating opioids,Citation17,Citation56 and another 20% did not routinely screen their patients’ opioid regimes.Citation17 A survey from 2018 documented an increased trend in the use of opioid risk tools and screening as compared to 8 years prior.Citation42 Further, in four studies, monitoring with surveillance measures, such as urine drug screening, was deemed stressful by PCPs and was reported to create tension between the PCP and the patient.Citation15,Citation20,Citation45,Citation56 Monitoring opioid effectiveness by assessing for functional improvement in patients with CNCP was acknowledged by PCPs as an important factor in guiding opioid prescribing,Citation44,Citation55 and in three studies, PCPs acknowledged that opioid prescriptions should be connected to goals of functional improvement beyond pain control.Citation24,Citation43,Citation57 PCPs also agreed that clear treatment goals should be established with patients prior to initiating opioids for treating CNCP.Citation44,Citation49

Attitudes and Perceptions Toward Opioid Prescribing and CNCP Management

In qualitative interviews, some PCPs questioned whether CNCP management, including opioid prescription, should be their responsibility,Citation45 and other PCPs expressed the realistic concern that patients may be denied adequate treatment if PCPs do not manage their patients’ CNCP.Citation15,Citation20 A common reason for referral to pain clinics was PCPs’ concerns about opioids; however, some PCPs reported frustration with pain clinics that at times prescribe high doses of opioids for CNCP that PCPs did not feel comfortable managing or continuing to prescribe.Citation48 PCPs also reported that patients were often initiated on opioids by other prescribers such as surgeons or pain specialists, with instructions to follow up with their PCP, creating difficulty for PCPs when deciding whether to refill patients’ requests for opioids.Citation15,Citation45,Citation54,Citation55 This was perceived by the PCPs as offloading responsibility without adequate communication or guidance,Citation45 resulting in disorganized care and poor outcomes for patients, such as dependency, illegal drug use, or unintentional withdrawal.Citation15

Nonpharmacological Interventions to Manage Pain

PCPs primarily treated patients with pharmacological therapies such as opioids, antidepressants, and anticonvulsants, whereas the use of nonpharmacological treatments such as engaging allied health colleagues was low in surveys, even if patients were able to fund these treatments.Citation24,Citation44 PCPs expressed interest in learning about the role of nonpharmacological pain treatment opportunities, such as cognitive behavior therapy, to manage CNCP.Citation15,Citation42,Citation44,Citation49,Citation59 One survey found that the most frequent nonpharmacological treatment modality utilized by PCPs for treating CNCP was psychotherapy, with 20% of PCPs exercising this option.Citation24 Referrals for consultations to physiotherapists, chiropractors, and osteopaths were reported by PCPs to improve patient self-management and satisfaction, as well as reduce the need for medications and consultations with PCPs.Citation16 However, PCPs felt that their attempts to encourage patients to adopt lifestyle modifications, such as weight reduction, were often met with resistance from patients, who expressed preference for pharmacological therapy in one qualitative survey.Citation57 Nevertheless, by empowering patients to be active participants in their own care, PCPs found it feasible to support them through lifestyle changes.Citation16,Citation57

Geographical and financial limitations were significant barriers to PCPs prescribing nonpharmacological interventions.Citation15,Citation20,Citation44,Citation46,Citation57,Citation59,Citation62,Citation64 PCPs interviewed reported a greater likelihood of prescribing opioids to patients of low socioeconomic status compared to less affordable nonpharmacological interventions, such as physiotherapy, massage, and psychotherapy.Citation57

Theme II: Interprofessional Collaboration

Challenges in Building Interprofessional Collaborations

PCPs expressed feeling unsupported in their endeavors to manage CNCP patients within the broader health care system,Citation45,Citation54,Citation62,Citation64 and this was perceived as impeding guideline-concordant care.Citation45,Citation54 The absence of multidisciplinary care in many clinical settings was believed by PCPs in two qualitative studies to be related to the experience of professional isolation.Citation15,Citation16 NPs felt that one of the major barriers to effective CNCP management was poor collaboration with physicians, and trusting relationships between NPs and physicians was perceived as a major facilitator by PCPs.Citation47 PCPs also reported relying on consultations with other physicians, pharmacists, nurses, and pain specialists to formulate treatment plans for CNCP.Citation15,Citation47 PCPs highlighted the need to collaborate with pharmacists in particular to provide effective treatment for patients.Citation16,Citation47 Physicians interviewed also endorsed primary care nurses being trained in pain management to support an multidisciplinary approach,Citation16 because nursing staff are increasingly relied upon by physicians to assess CNCP and evaluate adverse effects of pain medications.Citation15

PCPs interviewed who worked in a multidisciplinary environment were more confident in prescribing practices and CNCP management strategies.Citation15 Focus group discussions found that PCPs generally felt interprofessional education sessions were useful learning for managing patients with CNCP,Citation58,Citation60 provided opportunities to be better acquainted with their colleagues and respective areas of expertise, and aided the development of a common language on the topic of pain.Citation16,Citation60 Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) was quoted as an example of an interdisciplinary collaboration, in which multiple disciplines convene simultaneously for case-based learning, with the goal of “creating a community” of health professionals; this allows for regular interaction and has been found beneficial by PCPs in chronic pain education and management.Citation20,Citation41,Citation60 After participating in an interprofessional education workshop, most participants in a study indicated that they involved other health care professionals more frequently in managing CNCP.Citation20,Citation41,Citation58,Citation60

Deficits in Local and Regional Resources

There was a general consensus from PCPs in studies included in this review about the lack of available resources and access to specialists to support effective pain management.Citation15,Citation42,Citation45,Citation54,Citation59,Citation62,Citation64 A lack of clearly defined referral and care paths and limited information on available resources such as pain specialists and multidisciplinary pain treatment clinics were identified as possible reasons for these limitations in semifocused interviews.Citation16,Citation54 Long wait times, with the median being 6 monthsCitation16 but ranging as long as 3 to 5 years,Citation15,Citation16,Citation20,Citation46,Citation48,Citation55 were identified as a barrier to effective care for patients with CNCP. One study found that long wait times negatively affected patients, because they experienced higher pain intensity, functional interference, psychological distress (depression and suicidal ideation, anxiety, anger), and poorer quality of life.Citation16 Other barriers to referral to pain clinics included lack of specialized treatments outside of the context of formal pain clinics, distance from patients’ residences to the pain clinics, inability of pain clinics to offer frequent follow-up visits, and initiation of high-dose opioids by pain clinics that PCPs were not comfortable with continuing to prescribe.Citation48

One qualitative study suggested that providing good care for patients with complex CNCP would require significant transformation of the health care system.Citation54 PCPs opined that challenges posed by low socioeconomic status of patients with CNCP impacted available treatment options.Citation57,Citation59 Five studies reported that PCPs felt the cost of medications was a major barrier in delivering effective pain management.Citation20,Citation43,Citation44,Citation46,Citation55 Additionally, limited services available outside of major urban centers impacted patients with CNCP in rural areas, who often had more difficulty accessing recommended resources, such as physiotherapy.Citation20,Citation57

Theme III: Attitudes and Therapeutic Relationships

Therapeutic Relations between PCPs and Patients with CNCP

A common theme emerged in many studies of PCPs feeling challenged by balancing adequate analgesia with opioids against avoiding potential conflicts with patients or complications such as misuse and addiction.Citation15,Citation20,Citation45,Citation46,Citation54,Citation57,Citation59 In one qualitative study, PCPs reported struggling with refusal to prescribe opioids to patients.Citation57 Interviews with PCPs indicated that they had difficulty creating a trusting relationship with their patients with CNCP because of the difficulty in judging the legitimacy of patients’ requests for opioids.Citation15,Citation52,Citation54,Citation57 PCPs interviewed often felt torn between the goal of reducing patients’ suffering secondary to lack of effective treatments and ongoing pressure to avoid opioids.Citation15,Citation57

In two qualitative interviews, PCPs described having to engage with patients’ needs outside of CNCP and physical health, including mental health and social issues such as poverty and marginalization; this contributed to PCPs’ loss of job satisfaction, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization.Citation54,Citation57 Some PCPs interviewed found it difficult to trust pain statements from patients with depression or other mental health concerns, and they delegitimized pain complaints in the presence of psychiatric issues.Citation15,Citation54

PCPs also identified the term “chronic” in CNCP as discouraging, because it implies the inability to cure the patient’s pain, evoking dismay and annoyance from patients and underscoring CNCP as a “nuisance” condition.Citation52 Patients with CNCP frequently missing appointments was “frustrating” to some PCPs, even though PCPs realized that patients with CNCP may be dealing with significant life challenges outside of appointments.Citation15,Citation54

One qualitative study found that PCPs had difficulty navigating broader systemic inequalities affecting patients, resulting in dismissive and stigmatizing perceptions.Citation54 Further, some PCPs expressed that “patients’ complex social needs are outside the scope of biomedical expertise, and patients with CNCP should not expect PCPs to resolve their problems.”Citation54 The work associated with caring for patients taking opioids was termed by interviewees as “babysitting” rather than “caring,” implying a disconnect from a reciprocal therapeutic PCP–patient relationship.Citation57 Medical trainees interviewed in another qualitative study reported struggling with the legitimacy of the patient’s experience, because it was difficult to know how to appropriately respond and treat the patient when a patient’s pain cannot be measured and quantified except through the patient’s own narrative.Citation52

Patients with CNCP were often viewed by PCPs as passive care consumers rather than active partners in their treatment.Citation16 It was suggested in one qualitative study that patients’ empowerment needs were often not adequately addressed, and many patients were simply unaware of self-management strategies available to improve their CNCP.Citation16 There was often a discrepancy in PCPs’ perceptions of adequate pain management; one survey indicated that 82% of physicians were satisfied with their patients’ treatment plans; however, almost the same number of patients with CNCP (79%) noted that their ongoing pain was severe enough that it interfered with their function.Citation43

Significantly more time is spent with patients with CNCP compared to patients with other ailments,Citation43,Citation54 so a commonly reported barrier to effectively managing CNCP was lack of time.Citation44,Citation47,Citation54,Citation57,Citation59,Citation62 PCPs reported avoiding opioids due to time required to adequately manage initiation, monitoring, and tapering, and they felt it was a type and volume of work they were unequipped to handle.Citation15,Citation16,Citation49,Citation55,Citation57

Training Exposures and Attitudes toward CNCP for Medical Trainees

Twelve (46%) studies in this review highlighted PCPs reporting a lack of training in medical school or higher training in treating CNCP.Citation16,Citation20,Citation46–49,Citation51,Citation53,Citation55–57,Citation59,Citation64 PCPs expressed disappointment in medical training that emphasized curing (over caring for) patients as the cornerstone of good medical practice.Citation49,Citation52 They were also concerned that opioids were taught as the gold standard for pain management while a growing opioid-phobic medical culture urges avoidance of opioids altogether for treating CNCP.Citation15,Citation20,Citation45,Citation57 Medical students interviewed reported insufficient exposure to patients with CNCP, leading them to believe that such patients were “difficult,” and encounters with these patients were perceived to be challenging unpleasant tasks rather than a learning opportunity.Citation52 In this same qualitative study, PCPs reported perceiving previous supervisors and preceptors shielding them from patients with CNCP, giving the impression that such patients had limited educational value.Citation52 In one needs assessment survey, fewer than 10% of PCPs surveyed had taken a course involving CNCP in the past year,Citation61 and another survey reported that 65.7% of PCPs pursued continuing medical education in other topics.Citation54 The absence of a unified training program for PCPs providing a comprehensive approach to treating CNCP was also identified.Citation16,Citation20,Citation47,Citation48,Citation50,Citation57 In several qualitative studies, early-career PCPs expressed their interest in learning about skills and strategies necessary for safe opioid prescribing, navigating difficult conversations, and reinforcement of their ability to provide guideline-concordant care.Citation15,Citation45,Citation57 However, one of these studies stated that the educational strategies to disseminate guideline recommendations may be inadequate unless they address the interpersonal aspects of patient–provider interactions and PCPs develop skills needed to navigate the multidisciplinary system.Citation11 It was noted in two qualitative studies that current medical education curricula do not prepare PCPs to address the pressing needs of patients with CNCP related to low socioeconomic status but rather that the narrative continues to focus on the dangers of opioids themselves, instead of on adverse social conditions leading to widespread exposure to opioids.Citation54,Citation57

Theme IV: Strategies to Reduce Gaps in Care

Models cited as successful in addressing some gaps of care included Project ECHO interactive tele-mentoring,Citation49,Citation53,Citation56 interprofessional education workshops,Citation49,Citation53,Citation56 online learning modules,Citation59 teleconsultations/electronic consultations,Citation63,Citation65,Citation66 and streamlining referral pathways with clear tiered approaches to accessing tertiary pain care, such as Quebec’s Pain Centers of Expertise.

PCPs who attended Project ECHO tele-mentoring sessions reported an increase in overall confidence in managing patients with CNCP, citing decreased stress, learning from interprofessional colleagues, and feeling more empathetic toward their patients during clinical encounters.Citation20,Citation41,Citation60 ECHO was regarded as an insightful program to learn about responsible opioid prescribing, weaning, and deprescribing.Citation20,Citation41 However, PCPs attending workshops on treating CNCP preferred face-to-face interactive learning, including conferences and lectures.Citation49,Citation53,Citation56 Workshops highlighting interactive, interdisciplinary, patient-centered continuing education programs were perceived as necessary to fill knowledge gaps, foster mutual acquaintances, develop common discourses among local health care providers, and facilitate appropriate transmission of information among clinicians.Citation16,Citation20,Citation49,Citation51 Another survey reported small groups, online learning, or archived videos as preferred learning formats.Citation59

Alternative means of knowledge transfer was noted in three studies examining telephone consultations or electronic consultations (e-consults) for specific patients whom PCPs had referred to tertiary pain centers.Citation63,Citation65,Citation66 The study that incorporated a randomized control design comparing telephone consultations and usual care found no significant differences in patient outcomes, but PCPs reported satisfaction with the timely feedback on cases and found value in this means of knowledge transfer.Citation65 In another study, e-consults were found to be beneficial in suggesting a new or additional course of action in 74% of cases, with a median response time of 1.9 days, demonstrating a means with which pain clinics may have improved waitlists and PCPs receive timely feedback.Citation63 In a subsequent quality initiative examining e-consults, patients selected from the tertiary pain center waitlists that were appropriate for e-consults (i.e., did not request interventions, did not involve cancer cases or complex regional pain syndrome, or did not require physical examination) were offered e-consults.Citation66 Twenty-six percent of PCPs indicated that they were interested in this service, and 39% of PCP referrals were found by pain specialists to have questions that could at least be partially be managed by e-consults, demonstrating a practical means with a potential to reduce waitlists.Citation66 PCPs expressed high satisfaction rates with both telephone and e-consults as timely for their patients and an effective means of knowledge transfer.Citation63,Citation65,Citation66

Other means of supporting PCPs involves creating efficiencies within the larger health care system. The creation of pain centers of expertise with an integrated and hierarchical continuum of chronic pain services with designated local primary care clinics, designated regional secondary pain clinics, and tertiary centers with multidisciplinary pain treatment centers linked to affiliated rehabilitation centers significantly reduced wait times for patients with CNCP in Quebec.Citation16 This model enabled implementation of standardized consultation forms and evidence-based practice guidelines for the treatment of various types of CNCP syndromes, provided PCPs with tools to virtually discuss challenging clinical patient scenarios with pain specialists, and introduced new communication tools.Citation16

Discussion

This scoping review identified and synthesized the available literature in understanding PCPs’ perspectives on gaps in care in treating CNCP, including knowledge, skills, attitudes, and health care systems. Our review found 31 publications with consistent themes that could be mapped under four overarching themes: pain medicine competencies and practices, interprofessional collaboration, attitudes and therapeutic relationships, and strategies to reduce gaps in care. The perceived void of care options following the shift in opioid prescribing expectations was the challenge reported with the highest frequency, followed by the need for knowledge around pain assessment, nonpharmacological management, and interprofessional collaboration. The need for additional regional supports, means with which to effectively manage patient encounters to maximize limited time, and ongoing attitudes challenging therapeutic relationships with patients, beginning in basic medical education and carrying over into clinical practice, were consistently reported by PCPs across multiple studies in various regions of Canada. The secondary objective of this review was also achieved through identifying strategies identified by PCPs as useful in reducing some of these gaps in care, predominantly in knowledge dissemination and improving access to specialty care.

The four themes identified were deductively coded using the CanMEDS framework as a practical means of reorganizing themes and outlining ways in which medical education at different stages, both prior to entering and throughout practice, can address gaps in care identified by PCPs (). As an educational framework, the overarching goal of CanMEDS is to improve patient care by outlining abilities physicians should acquire to meet the needs of the patients they serve.Citation70 This was felt to aptly complement this scoping review in highlighting roles that PCPs and specialist colleagues need to address in medical education to holistically address gaps identified by PCPs in caring for patients with CNCP. The use of educational frameworks as a bridge between continuing health professions education intended to address complex issues and desired outcomes has been well described in other closely related chronic pain initiatives as a means for achieving demonstrable high-quality changes with regard to patient and population outcomes.Citation71,Citation72 Though CanMEDS is a framework centered around medical education, it is notable that there are strong parallels to the domains described in the National Nursing Education Framework for nursing education.Citation71 It was thus felt to be conceptually transferable.

Table 3. Deductive coding for the scoping review using the CANMeds framework.

With regard to pain medicine education, addressing practice issues in pain assessment, opioid prescribing/deprescribing, and other pharmacological/nonpharmacological management was a clear and frequently reported topic in almost all studies.Citation15–17,Citation20,Citation24,Citation41–50,Citation52–59,Citation62,Citation64 A stronger pain curriculum in both undergraduate and postgraduate medical education and continuing medical education courses enhancing these skills would also fulfil the CanMEDS role of “medical expert.”

The domain of interprofessional collaboration was present in many of the delivery models reporting high rates of satisfaction, such as Project ECHOCitation16,Citation41,Citation60 and Joint Adventures,Citation51 and continues to be an underutilized aspect of managing CNCP. Given the issues of limited access to pain specialists and resources, finding ways to weave the skills of many health professionals in treating patients with CNCP is clearly a valuable adjunct to not just improving patient care but also reducing professional isolation.Citation15,Citation16,Citation41,Citation60 Innovative knowledge transfer strategies, whether tele-mentoring or use of technology with e-consults, can both foster increased capacity in PCPs and reduce demand on limited tertiary specialty pain clinics.Citation20,Citation60,Citation63,Citation66 A shared care model in treating CNCP may also lead to a community of support that enables stronger provider–patient relationships,Citation16,Citation20,Citation41,Citation47,Citation58,Citation60 supporting clinicians’ growth in the CanMEDS role of “collaborator.”

Maximizing local and regional resources also falls under the CanMEDS role of “health advocate.” Though a suggested first step is to reduce disparities in specialized pain care access by increasing the capacity of PCPs to manage CNCP more effectively on their own, more work needs to be done by pain experts and health systems in streamlining referral pathways to access tertiary resources, with Quebec providing one such example.Citation16 Sharing expertise between pain medicine specialists and PCPs with ongoing support for PCPs and patients from tertiary pain centers is one approach in improving care of a challenging and undertreated chronic pain population and reducing professional isolation for PCPs.Citation10,Citation41,Citation63,Citation65,Citation66 This type of initiative also demonstrates the CanMEDS role of “leader” and is worth consideration for adoption in other parts of Canada. Further, though it was not the purpose of this review to speak to challenges of chronic pain management in the international context, because there will certainly be differences attributable to culture, sociopolitical values, economic differences, and variations in medical practice and other factors, international readers may find elements of this review that resonate with some aspects of providing care in their respective countries and thus may find it a useful document to reflect on means with which to address gaps in CNCP care as well.

This also leads to an argument for the growth needed in the role of the CanMEDS role of “communicator,” in which those pain experts providing tertiary care need to provide strong direct communication to PCPs in active shared care of patients with CNCP and present clear plans at time of patient discharge from tertiary care programs. Further, pain experts need to continue to consider ways of reducing prolonged wait times for patients with CNCP, perhaps in part by engaging in the process of educating PCPs in pain medicine, whether through continuing education and mentorship opportunities or on an individual case-by-case basis through virtual consultations with PCPs.Citation20,Citation41,Citation63,Citation65,Citation66 This may minimize less complex patient referrals to tertiary centers and increase overall resources for patients with CNCP in general.

This review found that development of therapeutic relationship skills was also desired by PCPs, b ecause the CNCP population continues to be perceived as a more challenging group of patients,Citation15,Citation20,Citation45,Citation46,Citation52,Citation54,Citation57,Citation59 and this theme is more relational in nature, perhaps requiring a reflection of values in medical training. Several of the publications included in this review highlighted attitudes PCPs have about patients with CNCP and the need for better training in early medical education to shift some of the negative attitudes that learners are exposed to.Citation15,Citation52,Citation54,Citation57 These findings point toward the root causes of reportedly challenging therapeutic relationships with patients with CNCP because of the hidden curriculum in medical education.Citation52 Medical learners need to have exposure to patients with CNCP early on in their training to ensure that they develop skills to manage pain, focusing on “care” not “cure,” and to enlighten learners that these patients do not represent something to be avoided but rather a learning opportunity.Citation49,Citation52 This baseline expectation of higher standards of behavior with respect for the diverse challenges faced by patients with CNCP care reflects the characteristics of the CanMEDS role of “professional.”

With regard to preferred delivery models for continuing education of CNCP identified in this review, participants reported a preference for interactive face-to-face workshops over online learning,Citation49,Citation53,Citation56 with the element of developing a support community for PCPs considered important.Citation41 Using multiple ways of learning and continually evaluating the outcomes of their work with dedication to lifelong learning help foster the growth of the CanMEDS role of “scholar.” It would be valuable to consider further scholarly research in this area to expand conceptual thinking, based on models of continuing education, as to why these delivery models are preferred and why they may be more effective in addressing the identified gaps.

Limitations

There are some limitations of this scoping review. First, we did not conduct an extensive gray literature search outside of Google Scholar, which may have elicited further perspectives useful to informing the research question. Second, limiting our search to publications in the English language might have excluded articles published in French as the other official Canadian language, but we noted on subanalysis that this review includes representation of perspectives from the province of Quebec. Third, we excluded literature exploring patient perspectives on what PCPs need to learn about chronic pain, which arguably is an important view on delivering patient-centered care and could easily be considered as a companion review in the future. Fourth, we excluded articles from our results with a tone that was critical of PCPs from the era of high-dose opioid prescribing, but some may argue that these perspectives may still be informative, even though these may no longer be considered best practice. The lens of the CanMEDS framework used to describe how reported gaps translate into opportunities for improvement in patient care from a medical point of view may not be wholly reflective of the values and abilities some subgroups of PCPs, such as nurse practitioners, identify with and assumes a degree of overlap of care values. Last, the use of a scoping review approach, though providing a broad snapshot of the current literature, sacrifices depth and detail that could potentially be valuable in understanding the minutiae of PCPs challenges with managing CNCP. A systematic review would perhaps be a valuable future step in addressing specific questions that arise as a result of this scoping review.

Conclusion

In our scoping review of PCPs perspectives on barriers in the provision of CNCP care, we found consistent themes emerging in the Canadian literature. Though many of these themes represent anticipated challenges, this review is important in uniting findings from many PCP voices and advancing advocacy for PCPs within our respective regions, as well as at a national level, as we seek to act on recommendations made by the Canadian Pain Taskforce to address chronic pain. Further research may be useful in developing conceptual thought around continuing medical education models effective for PCPs and for addressing large-scale population health problems such as CNCP.Citation73 As patients on high-dose opioids become less commonplace, educational needs will shift, but this review may also be a valuable starting point in further developing undergraduate medical education and continuing education programs. Our results also highlight themes going beyond provider-level knowledge gaps in CNCP care, including shifts needed in attitudes that will optimize patient–provider relationships and systemic issues that currently contribute to challenges experienced both by patients and their PCPs. Actionable initiatives geared toward transforming knowledge, skills, and attitudes can be informed by the issues outlined in this review, which, if combined with system-level changes, can improve outcomes of patients with CNCP in an otherwise underserviced patient population.

This scoping review brings together a cumulative body of literature on Canadian PCP perspectives from coast to coast on various gaps in the provision of CNCP care at a time we collectively seek not just to simply emerge from an opioid crisis but also to move forward with the work proposed by many researchers who came before us in improving the care of patients living with CNCP.

Author Contributions

All authors made significant contributions toward the execution of this scoping review. AB conceptualized the methodological design of this review and provided guidance to the research team. All authors contributed toward the development and refinement of scoping review questions. VM and ME screened all articles, with the results and discrepancies reviewed with AB. GL provided support in developing and articulating the study’s methodology. MFE supported the search methodology development and execution. AS provided inputs for editing the manuscript. The final version of this article was approved by all authors.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Peters AL. The changing definition of a primary care provider. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Dec 18;169(12):875–27. doi:10.7326/M18-2941.

- IASP Taxonomy working Group. Classification of chronic pain ( Second Edition) [Internet]. 2011. [accessed 2022 Aug 24]. https://www.iasp-pain.org/publications/free-ebooks/classification-of-chronic-pain-second-edition-revised/?ItemNumber=1673&navItemNumber=677]

- Henry JL. The need for knowledge translation in chronic pain. Pain Res Manag. 2008 Dec 01;13(6):465–76. doi:10.1155/2008/321510.

- Schopflocher D, Taenzer P, Jovey R. The prevalence of chronic pain in Canada. Pain Res Manag. 2011 Dec 1;16(6):445–50. doi:10.1155/2011/876306.

- Primary Health Care. [Internet]; 2021. [accessed 2022 Mar 31]. https://www.cihi.ca/en/primary-health-care

- Croft P, Blyth FM, Van der Windt D. Chronic pain epidemiology: from aetiology to public health; 2011.

- Mäntyselkä PT, Turunen JH, Ahonen RS, Kumpusalo EA. Chronic pain and poor self-rated health. JAMA. 2003 Nov 12;290(18):2435–42. doi:10.1001/jama.290.18.2435.

- Dubois MY, Follett KA. Pain medicine: the case for an independent medical specialty and training programs. Acad Med. 2014 June 1;89(6):863–68. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000265.

- Harle CA, Bauer SE, Hoang HQ, Cook RL, Hurley RW, Fillingim RB. Decision support for chronic pain care: how do primary care physicians decide when to prescribe opioids? A qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2015 Apr 14;16(1):48–015. doi:10.1186/s12875-015-0264-3.

- Clark AJ, Beauprie I, Clark LB, Lynch ME. A triage approach to managing a two year wait-list in a chronic pain program. Pain Res Manag. 2005 Jan 1;10(3):155–57. doi:10.1155/2005/516313.

- Desveaux L, Saragosa M, Kithulegoda N, Ivers NM. Family physician perceptions of their role in managing the opioid crisis. Ann Fam Med. 2019 Jul 01;17(4):345–51. doi:10.1370/afm.2413.

- Mezei L, Murinson BB. Johns Hopkins pain curriculum development team. pain education in North American medical schools. J Pain. 2011 Dec 1;12(12):1199–208. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2011.06.006.

- O’Rorke JE, Chen I, Genao I, Panda M, Cykert S. Physicians’ comfort in caring for patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. Am J Med Sci. 2007 Feb 1;333(2):93–100. doi:10.1097/00000441-200702000-00005.

- McCarberg BH. Pain management in primary care: strategies to mitigate opioid misuse, abuse, and diversion. Postgrad Med. 2011 Mar 1;123(2):119–30. doi:10.3810/pgm.2011.03.2270.

- Desveaux L, Saragosa M, Kithulegoda N, Ivers NM. Understanding the behavioural determinants of opioid prescribing among family physicians: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2019 May 10;20(1):59–019. doi:10.1186/s12875-019-0947-2.

- Lalonde L, Choinière M, Martin E, Lévesque L, Hudon E, Bélanger D, Perreault S, Lacasse A, Laliberté MC, Priority interventions to improve the management of chronic non-cancer pain in primary care: a participatory research of the ACCORD program. J Pain Res. 2015 Apr 30; 8:203–15. doi:10.2147/JPR.S78177.

- Weinberg E, Baer P Knowledge translation in pain education: is the message being understood? The 2010 annual conference of the Canadian Pain Society: Abstracts. Pain Res Manag. 2010 Apr 1;15(2):73–113.

- Werner A, Malterud K. It is hard work behaving as a credible patient: encounters between women with chronic pain and their doctors. Soc Sci Med. 2003 Oct 1;57(8):1409–19. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00520-8.

- Esquibel AY, Borkan J. Doctors and patients in pain: conflict and collaboration in opioid prescription in primary care. Pain. 2014 Dec 1;155(12):2575–82. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2014.09.018.

- Carlin L, Zhao J, Dubin R, Taenzer P, Sidrak H, Furlan A. Project ECHO telementoring intervention for managing chronic pain in primary care: insights from a qualitative study. Pain Med. 2018 June 1;19(6):1140–46. doi:10.1093/pm/pnx233.

- Watt-Watson J, McGillion M, Hunter J, Choiniere M, Clark AJ, Dewar A, Johnston C, Lynch M, Morley-Forster P, Moulin D, et al. A survey of prelicensure pain curricula in health science faculties in Canadian universities. Pain Res Manag. 2009 Dec 1, 14(6):439–44. doi:10.1155/2009/307932.

- Webster F, Bremner S, Oosenbrug E, Durant S, McCartney CJ, Katz J. From opiophobia to overprescribing: a critical scoping review of medical education training for chronic pain. Pain Med. 2017 Aug 1;18(8):1467–75. doi:10.1093/pm/pnw352.

- Objectives of Training in the Subspecialty of Pain Medicine [Internet]; 2018. [accessed 2022 Mar 31]. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwiy1834vM_wAhUIPK0KHbSaCnQQFjABegQIBRAD&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.royalcollege.ca%2Frcsite%2Fdocuments%2Fibd%2Fpain-medicine-otr-e.pdf&usg=AOvVaw1u53IEmRV-3CtHVL7eSRmF.

- Baer P. Current patterns in chronic non-cancer pain management in primary care. Canadian Pain Society abstracts, 2012 Pain Res Manag. 2012 June 01;17(3):180–233.

- An Action Plan for Pain in Canada [Internet]: Health Canada; [Internet] 2021 [Internet]. [accessed 2022 Jul 14]. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/corporate/about-health-canada/public-engagement/external-advisory-bodies/canadian-pain-task-force/report-2021-rapport/report-rapport-2021-eng.pdf.

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. 2005 Feb 01; 8(1):19–32.

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010 Sept 20;5(1):69–5908. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

- Mays N, Roberts E, Popay J. Synthesizing research evidence. In: Fulop N, Allen P, Clarke A, Black N, editors. Studying the organisation and delivery of health services: research methods. London: Routledge; 2001. p. 188–221.

- Pittman G, Morrell S, Ralph J. Opioid prescribing safety measures utilized by primary healthcare providers in Canada: a scoping review. J Nurs Reg. 2020;10(4):13–21. doi:10.1016/S2155-8256(20)30009-0.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Oct 02, 169(7):467–73. doi:10.7326/M18-0850.

- Higgins J, Green S, (editors. Cochrane handbook for systemic reviews of interventions version 6.2 [updated Feb 2021]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2021.

- Higgins J, Lasserson T, Chandler J, Tovery D, Churchill R. Methodological expectations of Cochrane intervention reviews. Version 1.05. London: Cochrane; 2016.

- McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C, PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Jul 1; 75:40–46. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021.

- The Yale MeSH analyzer. [Internet]. New Haven. CT: Cushing/Whitney Medical Library. 2021 cited 2019 December 19 http://mesh.med.yale.edu/

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. The Joanna Briggs institute reviewers’ manual 2015: methodology for JBI scoping reviews. Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2015.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. In: Qualitative research in psychology. Routledge; 2006. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Boyatzis R. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. Sage; 1998. p. 63.

- Roze Des Ordons AL, Lockyer J, Hartwick M, Sarti A, Ajjawi R. An exploration of contextual dimensions impacting goals of care conversations in postgraduate medical education. BMC Palliat Care. 2016 Mar 21;15(1):34–016. doi:10.1186/s12904-016-0107-6.

- Lincoln YS. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills (CA): Sage Publications; 1985. ID: 11467836.

- Furlan AD, Zhao J, Voth J, Hassan S, Dubin R, Stinson JN, Jaglal S, Fabico R, Smith AJ, Taenzer P, et al. Evaluation of an innovative tele-education intervention in chronic pain management for primary care clinicians practicing in underserved areas. J Telemed Telecare. 2019 Sep 1; 25(8):484–92. doi:10.1177/1357633X18782090.

- Furlan AD, Diaz S, Carol A, MacDougall P, Allen M. Self-reported practices in opioid management of chronic noncancer pain: an updated survey of Canadian family physicians. J Clin Med. 2020 Oct J Nurs Reg 14;9(10):3304. doi:10.3390/jcm9103304

- Baer P Patterns and trends in the management of pain in primary care: a practice audit. the 2010 annual conference of the Canadian Pain Society: Abstracts. Pain Res Manag 2010 Apr 1;15(2):73–113.

- Chow R, Saunders K, Burke H, Belanger A, Chow E. Needs assessment of primary care physicians in the management of chronic pain in cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2017 Nov 1;25(11):3505–14. doi:10.1007/s00520-017-3774-9.

- Goodwin J, Kirkland S. Barriers and facilitators encountered by family physicians prescribing opioids for chronic noncancer pain. Family Medicine Forum Research Proceedings 2017: Abstracts Can Fam Physician. 2018 Feb 1;64(2):S1.

- Kaasalainen S, DiCenso A, Donald FC, Staples E. Optimizing the role of the nurse practitioner to improve pain management in long-term care. Can J Nurs Res. 2007 June 1;39(2):14–31.

- Lakha SF, Yegneswaran B, Furlan JC, Legnini V, Nicholson K, Mailis-Gagnon A. Referring patients with chronic noncancer pain to pain clinics: survey of Ontario family physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2011 Mar 01;57(3):e106–12.

- Lalonde L, Leroux-Lapointe V, Choinière M, Martin E, Lussier D, Berbiche D, Lamarre D, Thiffault R, Jouini G, Perreault S. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about chronic noncancer pain in primary care: a Canadian survey of physicians and pharmacists. Pain Res Manag. 2014 Oct 1;19(5):241–50. doi:10.1155/2014/760145.

- Midmer D, Kahan M, Marlow B. Effects of a distance learning program on physicians’ opioid- and benzodiazepine-prescribing skills. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006 Jan 1;26(4):294–301. doi:10.1002/chp.82.

- Petrella RJ, Davis P. Improving management of musculoskeletal disorders in primary care: the joint adventures program. Clin Rheumatol. 2007 Jul 1;26(7):1061–66. doi:10.1007/s10067-006-0446-4.

- Rice K, Ryu JE, Whitehead C, Katz J, Webster F. Medical trainees’ experiences of treating people with chronic pain: a lost opportunity for medical education. Acad Med. 2018 May 1;93(5):775–80. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002053.

- Squire P, Irving G. The pain champion project: evaluation of a 12-week interactive learning program to improve family medicine care of chronic pain patients. J Pain. 2009;10(4, Supplement):S20. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2009.01.085.

- Webster F, Rice K, Bhattacharyya O, Katz J, Oosenbrug E, Upshur R. The mismeasurement of complexity: provider narratives of patients with complex needs in primary care settings. Int J Equity Health. 2019 Jul 4;18(1):107–19. doi:10.1186/s12939-019-1010-6.

- Allen MJ, Asbridge MM, Macdougall PC, Furlan AD, Tugalev O. Self-reported practices in opioid management of chronic noncancer pain: a survey of Canadian family physicians. Pain Res Manag. 2013 Aug 1;18(4):177–84. doi:10.1155/2013/528645.

- Roy É, Côté RJ, Hamel D, Dubé PA, Langlois É, Labesse ME, Thibault C, Boulanger A. Opioid prescribing practices and training needs of Québec family physicians for chronic noncancer pain. Pain Res Manag. 2017;2017:1365910. doi:10.1155/2017/1365910.

- Webster F, Rice K, Katz J, Bhattacharyya O, Dale C, Upshur R. An ethnography of chronic pain management in primary care: the social organization of physicians’ work in the midst of the opioid crisis. PLoS One. 2019 May 1;14(5):e0215148. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0215148.

- Allen M, Macleod T, Zwicker B, Chiarot M, Critchley C. Interprofessional education in chronic non-cancer pain. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2011 May 01;25(3):221–22. doi:10.3109/13561820.2011.552134.

- Busse JW, Douglas J, Chauhan TS, Kobeissi B, Blackmer J. Perceptions and impact of the 2017 Canadian guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain: a cross-sectional study of Canadian physicians. Pain Research and Manag. 2020 Feb 17;2020:8380171. doi:10.1155/2020/8380171.

- Hassan S, Carlin L, Zhao J, Taenzer P, Furlan AD. Promoting an interprofessional approach to chronic pain management in primary care using project ECHO. J Interprof Care. 2020 Mar;09:1–4.

- Julien N, Ware M, Lacasse A. Family physicians and treatment of chronic non-cancer pain: an educational needs assessment. 36th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Canadian Pain Society: Abstracts. Pain Res Manag. 2015 June 1;20(3):164–67.

- Wingert K, Hosain J, Tupper S, Vanstone J, Jacqueline Myers B, Cameron Symon B, Murray Opdahl M Care provider needs assessment of chronic non-cancer pain management. 30 Th Annual Resident Scholarship Day Abstract Book:74.

- Liddy C, Smyth C, Poulin PA, Joschko J, Rebelo M, Keely E. Improving access to chronic pain services through eConsultation: a cross-sectional study of the Champlain BASE eConsult service. Pain Med. 2016;17(6):1049–57. doi:10.1093/pm/pnw038.

- MacLean C, Heeley T, Versteeg E, Asghari S. Barriers to opioid deprescription in rural Newfoundland and Labrador: findings from pilot interviews with rural family physicians; 2020.

- Clark AJ, Taenzer P, Drummond N, Spanswick CC, Montgomery LS, Findlay T, Pereira JX, Williamson T, Palacios-Derflingher L, Braun T. Physician-to-physician telephone consultations for chronic pain patients: a pragmatic randomized trial. Pain Res Manag. 2015 Dec 1;20(6):288–92. doi:10.1155/2015/345432.

- Poulin PA, Romanow HC, Cheng J, Liddy C, Keely EJ, Smyth CE. Offering eConsult to family physicians with patients on a pain clinic wait list: an outreach exercise. J Healthc Qual. 2018 Oct 1;40(5):e71–6. doi:10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000117.

- Scanlon MN, Chugh U. Exploring physicians’ comfort level with opioids for chronic noncancer pain. Pain Res Manag. 2004 Jan 1;9(4):195–201. doi:10.1155/2004/290250.

- Morley-Forster PK, Clark AJ, Speechley M, Moulin DE. Attitudes toward opioid use for chronic pain: a Canadian physician survey. Pain Res Manag. 2003 Jan 1;8(4):189–94. doi:10.1155/2003/184247.

- Boulanger A, Clark AJ, Squire P, Cui E, Horbay GL. Chronic pain in Canada: have we improved our management of chronic noncancer pain? Pain Res Manag. 2007 Jan 1;12(1):39–47. doi:10.1155/2007/762180.

- CanMEDS: Better standards, better physicians, better care. [Internet]; 2021. [accessed 2021 May 20]. https://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/canmeds/canmeds-framework-e

- Sud A, Doukas K, Hodgson K, Hsu J, Miatello A, Moineddin R, Paton M. A retrospective quantitative implementation evaluation of safer opioid prescribing, a Canadian continuing education program. BMC Med Educ. 2021 Feb 12;21(1):101. doi:10.1186/s12909-021-02529-7.