ABSTRACT

Background

Continuing professional development is an important means of improving access to effective patient care. Although pain content has increased significantly in prelicensure programs, little is known about how postlicensure health professionals advance or maintain competence in pain management.

Aims

The aim of this study was to investigate Canadian health professionals’ continuing professional development needs, activities, and preferred modalities for pain management.

Methods

This study employed a cross-sectional self-report web survey.

Results

The survey response rate was 57% (230/400). Respondents were primarily nurses (48%), university educated (95%), employed in academic hospital settings (62%), and had ≥11 years postlicensure experience (70%). Most patients (>50%) cared for in an average week presented with pain. Compared to those working in nonacademic settings, clinicians in academic settings reported significantly higher acute pain assessment competence (mean 7.8/10 versus 6.9/10; P < 0.002) and greater access to pain specialist consultants (73% versus 29%; P < 0.0001). Chronic pain assessment competence was not different between groups. Top learning needs included neuropathic pain, musculoskeletal pain, and chronic pain. Recently completed and preferred learning modalities respectively were informal and work-based: reading journal articles (56%, 54%), online independent learning (44%, 53%), and attending hospital rounds (43%, 42%); 17% had not completed any pain learning activities in the past 12 months. Respondents employed in nonacademic settings and nonphysicians were more likely to use pocket cards, mobile apps, and e-mail summaries to improve pain management.

Conclusions

Canadian postlicensure health professionals require greater access to and participation in interactive and multimodal methods of continuing professional development to facilitate competency in evidence-based pain management.

RÉSUMÉ

Contexte: Le développement professionnel continu est un moyen important d’améliorer l’accès à des soins efficaces pour les patients. Bien que le contenu lié à la douleur ait augmenté de manière significative dans les programmes préalables à l’autorisation d’exercer, on sait peu de choses sur la façon dont les professionnels de la santé après licenciés améliorent ou maintiennent leurs compétences en matière de gestion de la douleur.

Objectifs: Étudier les besoins, les activités et les préférences de développement professionnel continu des cliniciens canadiens en matière de gestion de la douleur.

Méthodes: Enquête Web transversale d’auto-évaluation.

Résultats: Le taux de réponse au sondage était de 57 % (230/400). Les répondants étaient principalement des infirmières (48 %), des diplômés universitaires (95 %), des employés en milieu hospitalier universitaire (62 %), avec ≥11 ans d’expérience après l’obtention du permis (70 %). La plupart des patients (> 50 %) pris en charge dans une semaine moyenne présentaient des douleurs. Comparativement à ceux qui travaillent dans des milieux non universitaires, les cliniciens en milieu universitaire ont signalé une compétence d’évaluation de la douleur aiguë significativement plus élevée (moyenne de 7,8/10 contre 6,9/10; P < 0,002) et un meilleur accès aux consultants en gestion de la douleur (73 % contre 29 %; P < 0,0001). La compétence d’évaluation de la douleur chronique n’était pas différente entre les groupes. Les principaux besoins d’apprentissage comprenaient la douleur neuropathique, la douleur musculo-squelettique et la douleur chronique. Les modalités d’apprentissage récemment achevées et préférées étaient respectivement informelles et basées sur le travail: lecture d’articles de journaux (56 %, 54 %), apprentissage indépendant en ligne (44 %, 53 %) et participation à des visites à l’hôpital (43 %, 42 %); 17 % n’avaient effectué aucune activité d’apprentissage de la douleur au cours des 12 derniers mois. Les répondants hors les médecins et ceux employés dans des milieux non universitaires étaient plus susceptibles d’utiliser des cartes de poche, des applications mobiles et des résumés par e-mail pour améliorer la gestion de la douleur.

Conclusions: Les professionnels de la santé canadiens après l’obtention du permis d’exercice ont besoin d’un meilleur accès et d’une plus grande participation aux méthodes interactives et multimodales de développement professionnel continu pour faciliter la compétence en gestion de la douleur fondée sur des données probantes.

Introduction

Inadequate knowledge and skills among practicing health care professionals (HCPs) are persistent barriers to effective pain management and positive patient outcomes.Citation1 Due to the growing prevalence and societal burden of pain, continuing professional development (CPD) has emerged as an important means of improving access to evidence-based pain care.Citation2 However, some HCPs continue to express discomfort in addressing pain concerns due to unmet learning needs, which may contribute to poor outcomes.Citation3 Despite efforts to increase knowledge of pain prevention and management among prelicensure HCPs, there is scant understanding of postlicensure initiatives to advance and/or maintain evidence-based pain practice.Citation4 Understanding postlicensure HCPs’ pain education needs, activities, and preferred learning modalities is an important starting point for the development of effective competency based CPD pain resources.

Internationally, millions of individuals suffer from pain each year as a result of disease, trauma, and surgery.Citation5 Although pain is among the most common reasons patients seek medical attention, the management of pain remains inadequate across settings, with a substantial proportion of patients reporting unrelieved pain.Citation6 Up to 75% of patients report moderate to severe acute painCitation7 and up to 60% of patients experience chronic pain following common surgical procedures.Citation8 Some individuals seek the help of more than one HCP for chronic pain diagnosis and treatment. However, other individuals may choose not to seek medical assistance due to a perceived lack of provider expertise or empathy.Citation9 Poorly managed chronic pain carries both human and economic costs for individuals, families, and society because it undermines patients’ ability to participate in relationships, education, and employment. Chronic pain is also more frequently experienced in populations affected by social and economic inequities, which may exacerbate health disparities and the incremental costs to health systems.Citation10,Citation11

CPD is an umbrella term for a range of activities undertaken by HCPs to acquire the knowledge and skills needed to deliver high-quality care throughout their careers.Citation3 CPD activities relevant to pain may include but are not limited to formal courses (e.g., classroom learning, online courses, workshops), informal activities (e.g., reading journal articles, attending professional conferences), and work-based learning (e.g., hospital rounds, case discussions).Citation4 CPD has traditionally focused on passive delivery formats typified by experts providing learning content in a lecture format.Citation12 More recently, CPD has progressed toward competency-based CPD, which moves beyond conceptual knowledge gain (e.g., input) toward an individual’s capacity to successfully and empathically perform a task (e.g., outcome). One example is Project ECHO (the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes), which uses telemedicine to connect HCPs working in rural or nonacademic settings with pain specialists, aiming to enhance their competencies in helping people to manage their chronic pain.Citation13 Project ECHO is characteristic of competency-based CPD in its use of active problem solving, real-world cases, application of evidence-based guidelines, and feedback mechanisms.Citation3

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) has endorsed the interprofessional pain consensus competencies for prelicensure HCP training that address the IASP four pain curricula domains: multidimensional nature of pain, pain assessment and measurement, management of pain, and clinical conditions.Citation14 The pain competency framework includes recommendations for active learning methods such as objective appraisal of performance and personalized learning feedback. Although developed for prelicensure HCPs, the pain competency framework has been identified as an ideal approach for thinking about knowledge gaps among licensed HCPs.Citation4 Despite prior research identifying the success of continuing education in pain, HCPs report variable access to CPD resources aligned with their self-identified learning needs, preferred learning formats, and perceptions of quality.Citation15,Citation16 CPD educators, health care organizations, and accrediting bodies would benefit from further insight regarding HCP learning needs and preferences to determine how best to meet those needs.

The University of Toronto Center for the Study of Pain (UTCSP), a collaborative partnership of the Faculties of Medicine, Nursing, Dentistry, and Pharmacy at the University of Toronto, upholds a mission to create and disseminate knowledge on pain across the life span and foster clinical excellence through interdisciplinary collaboration.Citation17 To meet its goal to develop educational programs in pain, the UTCSP Education Subcommittee sought to better understand Canadian postlicensure clinicians’ CPD needs with regard to pain. The specific study objectives were to describe HCPs’ self-identified pain learning needs according to the IASP competency framework, recent continuing education activities, and preferred learning modalities and explore individual HCP characteristics that may inform future CPD opportunities. We hypothesized that HCPs working in academic (i.e., university-affiliated) hospital settings would have greater access to pain knowledge resources, and therefore different self-rated pain assessment competencies and learning needs, in comparison to those working in nonacademic hospitals or other settings.

Methods

Overview

We conducted a self-administered, cross-sectional, deidentified web survey of licensed Canadian HCPs’ pain CPD needs, activities, and preferred learning modalities. We aimed to include diverse postlicensure HCPs employed in a hospital or outpatient setting at the time of the survey.

Survey Development

Seven clinician-scientists generated survey items: three nurses, one physician, two dentists, and a physiotherapist. In addition to participant demographics (e.g., professional role, care setting, patient populations), survey items pertained to self-rated acute and chronic pain assessment competency, evidence-based pain appraisal and management resources, and future areas for professional development organized according to the four pain competency domains.Citation14 Item reduction for the survey occurred through an iterative process among the study investigators. The survey was then sent to five pain experts who were not involved in item generation for face and content validity, discriminability, utility, and clarity.Citation18 Five different clinicians participated in cognitive interviews to confirm comprehension and congruence of domains and items and to determine the 10-min time to survey completion (Supplement 1).Citation19

Sample and Methodology

We estimated a definitive sample size for this survey derived from a UTCSP-Interfaculty Pain Curriculum (IPC) member database of approximately 400 clinicians including nurses, physicians, pharmacists, dentists, and diverse allied health professionals. These members had previously registered with the UTCSP to participate in research and educational opportunities. Assuming a population of this size, a 95% confidence level, and a margin of error of 5%, it was estimated that 196 clinicians would be needed to complete the survey. Delivery and management of the survey was accomplished using SurveyMonkey, a secure web-based application designed exclusively to support data capture for survey studies.Citation20 The survey items had a multiple-choice response format with the exception of two self-rating scales (0–10) for pain assessment competence, where 0 indicated not competent and 10 indicated highly competent. We followed the modified Dillman method, which aims to maximize survey response and minimize project bias.Citation21 This included an introductory e-mail informing eligible respondents of the forthcoming survey, a personalized e-mail with survey link, and three reminder e-mails for nonresponse. In addition, we used the UTCSP website and Twitter account to increase awareness of the survey. There was no compensation for survey participation.

Ethics

The study received approval from the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board (#36505). The web survey preamble outlined the purpose of the survey, data collection, and management strategies including the protection of privacy, and the anticipated time commitment to complete all items. Respondents were required to acknowledge their consent to participate to access the survey.

Analysis

Survey data were downloaded from SurveyMonkey to Microsoft Excel (v16.63.1) for analysis. Reponses to each question were collated and analyzed by comparing groups defined by work setting (academic versus nonacademic) for professional role, highest level of education, years of professional work experience, number of patients cared for each week, self-reported pain assessment competency, access to pain specialists, and CPD activities and preferences. Categorical data were summarized as frequencies and percentages. Continuous data were summarized using mean ± standard deviations. The chi-square and/or Fisher’s exact tests were used to examine differences between groups. An independent statistician performed all analyses using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. To improve the transparency of reporting, we followed the Consensus-Based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (Supplement 2).Citation22

Results

Over an eight-week period (December 2018 and January 2019), a total of 230 HCPs completed the survey, resulting in a 57% return rate. Respondents were nurses (registered nurses and/or nurse practitioners; 47.5%), pharmacists (16.5%), physicians (13.0%), physiotherapists (10.8%), occupational therapists (4.3%), dentists (3.9%), and other health professionals (3.0%). The majority were university educated (95%), employed in an academic hospital setting (62%), with ≥11 years (70%) postlicensure clinical experience (). Education and years of experience did not differ significantly between HPCs working in academic compared to nonacademic settings. Patient groups encountered in practice included adults (93%), older adults (80%), adolescents (36%), and infants/children (25%); 19% worked with all patient groups in their current role (). Those working in nonacademic settings more often cared for high volumes of patients (>100) in an average week compared to those in academic settings (P = 0.004). However, regardless of work setting, most patients (>50%) cared for in an average week reported pain, with musculoskeletal problems predominating.

Table 1. Respondent characteristics across academic and nonacademic settings.

Table 2. Patient conditions.

Pain Assessment and Treatment

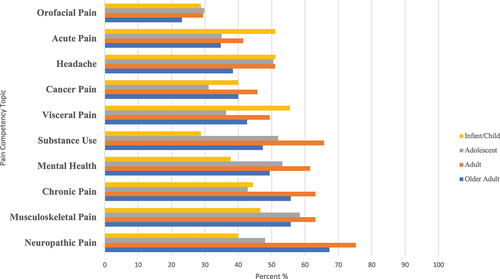

Respondents employed in academic settings had significantly higher self-rated acute pain assessment competence (7.8/10 versus 6.9/10; P = 0.002) compared to those employed in nonacademic settings. There was no difference in chronic pain assessment competence between the group settings (). Across respondent categories, the reported range of tools routinely used to assess patients included unidimensional self-report pain scales (31%–84%), behavioral pain scales (2%–29%), and multidimensional pain scales (15%–27%). Resources used alone or in combination to make treatment choices by all categories of respondents included patient self-report (73%), patient goal setting (61%), and professional consultation (53%); protocols (44%), guidelines (43%), and standardized clinical order sets (40%) were used less frequently (). Over half (56%) of all respondents reported having access to an acute pain specialist/team to facilitate treatment; however, slightly less than half (46%) had access to a chronic pain specialist/team. Those employed in academic hospital settings had significantly greater access to acute (73% versus 29%; P = 0.0001) and chronic (57% versus 27%; P = 0.0001) pain specialists ().

Figure 1. Self-reported acute and chronic pain assessment competency across academic and nonacademic settings.

Table 3. Pain assessment and management resources.

Pain Competency Development Needs

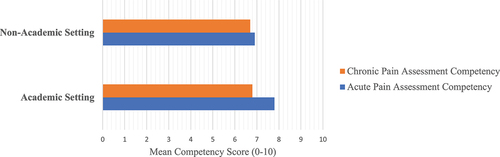

Self-identified pain development needs organized by the pain competency domains included (1) “multidimensional nature of pain” domain: pain physiology (59%), consequences of pain (50%), and pain theory (48%); (2) “assessment and measurement of pain” domain: pain assessment tools/scales (60%), interprofessional collaboration (57%), and tool reliability/validity (52%); (3) “management of pain” domain: psychological/cognitive methods (57%), pain management planning (54%), and pharmacological methods (54%; ). For development needs related to the fourth domain, “populations/clinical conditions,” the top conditions identified were neuropathic pain for older adults (67%) and adults (75%), musculoskeletal pain (58%) for adolescents, and visceral pain (55%) for infants/children ().

Table 4. Pain competency development needs.

Completed CPD Activities and Preferences

In the 12-month period immediately preceding survey completion, the most frequent CPD activities related to pain were reading journal articles (56%), online independent learning (44%), and attending hospital rounds (43%); 17% had not completed any pain learning activities (). There was no significant difference in CPD preference according to academic work setting, professional role, education, or years of experience for reading journal articles or online independent learning. Participation in hospital rounds was preferred by respondents employed in academic settings (P = 0.007). Nonphysicians (e.g., nurses, pharmacists, dentists, and allied health professionals), when compared to physicians, had a significantly greater preference for attending formal courses (P = 0.02) and receiving e-mail updates summarizing the latest pain evidence (P = 0.01). Those with experience of ten years or less (P = 0.04) and those without a graduate degree (P = 0.03) preferred attending international and local conferences, respectively. There were no significant differences in preference across respondent categories for use of internet resources, including online courses, social media sites, or live webcasts. Across academic and nonacademic work categories, tools perceived as potentially useful for advancing evidence-based pain treatment at the point of care included mobile apps (35%–51%), pocket cards (21%–38%), e-mail updates (18%–33%), and video instruction (11%–41%); however, pocket cards and/or e-mail updates were more frequently preferred by those working in nonacademic settings ().

Table 5. Comparison of completed and preferred learning modalities across academic and nonacademic settings.

Table 6. Comparison of pain tool preferences across academic and nonacademic settings.

Discussion

In our survey of Canadian HCPs, we found self-reported CPD learning needs related to pain distributed across all IASP competency domains. The results supported how the IASP endorsed pain competencies are a relevant framework for beginning to consider CPD needs/interests among postlicensure HCPs. Respondents reported that more than half of all patients encountered in an average week presented with pain; this finding emphasizes the importance of knowledgeable HCPs to ensure safe and effective pain management. Most reported moderate competency in assessing acute pain and routine use of unidimensional pain assessment tools. Competency in appraising chronic pain was lower, albeit not significantly lower, than for acute pain. Multidimensional pain appraisal tools were not routinely incorporated into practice. Recently completed pain learning activities and future learning preferences were most often informal (e.g., reading journal articles, attending conferences) and work-based (e.g., hospital rounds) in nature.

As hypothesized, HCPs working in academic settings had greater access to resources such as pain specialists/teams and higher self-rated acute pain competency in comparison to peers working in nonacademic settings. The knowledge and skill to assess both acute and chronic pain are a critical component of accurate pain classification and a core IASP-endorsed competency. Our results demonstrate room for improving HCP skill and confidence, particularly in chronic pain assessment, which is important in the context of an aging population and growing prevalence of complex pain conditions.Citation23 Primary care providers report chronic pain as one of the most challenging conditions to treat, yet it is given limited attention in any HCP curriculum in relation to the societal burden it imposes.Citation24 Up to 25% of Canadians have chronic pain, which is associated with functional and social impairment. HCP interest in learning more about multidimensional pain appraisal is relevant for diagnosing chronic pain and understanding its treatment options.

The top identified condition for continuing knowledge development among those caring for adult and older adult populations was neuropathic pain, which has a high impact on quality of life and increasing prevalence in North America.Citation25 Compared with other pain issues, neuropathic pain is likely to be rated as more severe.Citation26 Symptoms of neuropathic pain such as burning, numbness, and allodynia can be difficult for patients to describe. This may be particularly true of institutionalized older adults, who often experience self-report incapacities.Citation27 Taken together, these issues may contribute to problems diagnosing neuropathic pain outside of specialty settings. Moreover, the modest to moderate benefit of conventional analgesics for neuropathic pain may factor into treatment uncertainties among HCPs and lack of pain relief among patients.Citation28 HCP trainees in Canada have limited exposure to patients with persistent chronic pain conditions. This training gap may leave them unclear about appropriate care in practice.Citation29

The most frequently identified competency development needs for those caring for adolescents and children/infants were musculoskeletal pain and visceral pain, respectively. Drivers of help-seeking for musculoskeletal pain appear to be severe pain intensity and limited activity; up to 37% of children and adolescents report visiting a clinician for such pain in the past year.Citation30 Similarly, abdominal (e.g., visceral) pain is a common problem among children.Citation31 Those experiencing chronic abdominal pain report significantly lower quality of life compared to their healthy counterparts and are more frequently absent from school.Citation32 There is emerging evidence that children and adolescents who report persistent pain are at increased risk of chronic pain as adults.Citation30 These commonly presenting pain conditions represent practical learning needs and a likely opportunity to influence both practice and patient outcomes through targeted CPD.

Years in practice is not necessarily a determinant of competence in pain management.Citation33 Instead, HCPs’ capacities to successfully deliver patient-centered pain care are predicated upon foundational training and an environment that supports continuous professional development.Citation4 Current IASP recommendations include multidisciplinary and interprofessional learning approaches, whereby shared understandings of pain mechanisms and biopsychosocial concepts contribute to collaborative and comprehensive patient treatment.Citation34 The informal approaches reported by respondents in this study (e.g., reading journal articles) may be ineffective in changing or reinforcing one’s capacity to perform a task. Effective professional development experiences are most often interactive, multimodal, and cyclic and incorporate performance feedback.Citation35 This aligns with growing scientific evidence that passive implementation strategies are less effective than active ones.Citation36 Therefore, it is appropriate for HCPs to reflect on the IASP competency domains to identify priority learning needs and effective modalities for enhanced care delivery.Citation37

Improving HCP skill and confidence in assessment and managing pain is important for equitable health outcomes. In Ontario, Canada’s most populated province, approximately 55% of all hospital beds are in large (nonacademic) community hospitals, defined as having more than 100 beds. These community hospitals provide medical and surgical care to >65% of all patients in the province annually.Citation38 In contrast, the majority (91.3%) of multidisciplinary specialist pain clinics that provide access to multimodal care for people living with chronic pain are concentrated in large urban cities, with almost two-thirds (64.9%) being university affiliated.Citation39 In our study, the lower reported HPC access to acute and chronic pain specialists in nonacademic work settings may unintentionally contribute to either failure or delay in the implementation of evidence-based pain management. This issue may exacerbate known inequities in pain treatment and outcomes,Citation11 especially for those in rural settings who may experience additional barriers to accessing health care.Citation40

The Canadian Pain Task Force was established in 2019 to better understand and address the needs of people living with chronic pain.Citation1 The Canadian Pain Task Force strongly recommends that health professionals continually develop the competencies they require to successfully provide effective pain care. The wide range of learning needs identified in our study point to the importance of health system investment and organizational leadership facilitation of CPD in pain. When CPD is driven solely by professional registration requirements, it can lead to a dissociation from lifelong learning.Citation41 For many HCPs, personal motivation, real-world patient care needs, and preference for workplace learning are important drivers of CPD.Citation42 Strong enabling leadership and a culture of inquiry are important for translating evidence into clinical practice.Citation43 This may be particularly important in nonacademic and rural/remote clinical settings, which may lack a range of resources (e.g., pain specialist/teams, education staff, researchers) that are more readily available in larger urban settings. HCPs working in rural settings may experience barriers to leaving their region to attend CPD opportunities, thus pointing to the importance of organizational investment in workplace learning.

The potential of digital CPD modalities to improve HCP access to learning opportunities has been recently accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Since 2020, in-person meeting restrictions and pandemic-related travel embargoes have limited access to conventional CPD opportunities such as local, national, and international conferences and hospital rounds/case discussions. HCPs have responded positively to digital conferences and e-learning courses because they can be less costly and taken at time suited to their schedule.Citation44 These changes may align with advances in clinical learning sciences, which now emphasize how flexible learning opportunities can increase participation.Citation45 Application of knowledge and feedback mechanisms can be incorporated in digital learning so that participants can reflect upon their developing knowledge and skill.Citation33 Digital formats can also reinforce knowledge uptake through recurrent access to learning content. Both academic and nonacademic health care institutions should consider implementation of digital CPD opportunities in pain management.

Strengths of the study include the interprofessional survey design, high survey return rate, and the inclusion of diverse groups of HCPs. Aspects of our survey methods leave open the possibility that our findings do not represent the larger population of Canadian HCPs; participants may overrepresent nurses, those with greater years of professional experience, and HCPs working in academic hospital settings. The eight-week response period may have biased results to early responders and the web-only administration format may exclude those who do not regularly check e-mail or are less comfortable with online interactions. Tailoring items and response frames to each HCP group and/or clinical population could have enhanced relevance. Although we evaluated the face and content validity of the survey, some items may not have been understood equally. As with all surveys, self-reported practices may not align with actual practices. Finally, our survey predated the COVID-19 pandemic, which means that learning needs may have evolved.

Conclusion

In this cross-sectional survey of Canadian postlicensure HCPs, respondents frequently encountered patients experiencing pain. They identified their learning needs to improve the management of complex and persistent pain conditions. IASP-endorsed interprofessional pain competencies offer a productive framework for assessing HCP learning needs and identifying domains for targeted knowledge development. Greater access to CPD and pain experts using a number of learning modalities is warranted to facilitate evidence-based pain management and optimal patient outcomes.

Author Contributions

All authors meet the ICMJE requirements for authorship. All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design, data acquisition, data analysis, and interpretation of data. All authors were involved in drafting, revising, and approving the final article.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (309.6 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (36.4 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank the clinicians who participated in this survey for their dedication to pain practice, education, and research. The authors acknowledge Renata Musa for her assistance with this study.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/24740527.2022.2150156

Additional information

Funding

References

- Canada Health Canada. Chronic pain in Canada: laying a foundation for action : a report by the Canadian pain task force, June 2019. Health Canada = Santé Canada; 2019.

- Rice ASC, Smith BH, Blyth FM. Pain and the global burden of disease. Pain. 2016;157(4):791–12. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000454.

- Davis DA D, McMahon GT. Translating evidence into practice: lessons for CPD. Med Teach. 2018;40(9):892–95. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1481285.

- Devonshire E, Nicholas MK. Continuing education in pain management: using a competency framework to guide professional development. PAIN Rep. 2018;3(5):e688. doi:10.1097/PR9.0000000000000688.

- Gatchel RJ, Reuben DB, Dagenais S, Turk DC, Chou R, Hershey AD, Hicks GE, Licciardone JC, Horn SD. Research agenda for the prevention of pain and its impact: report of the work group on the prevention of acute and chronic pain of the federal pain research strategy. J Pain. 2018;19(8):837–51. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2018.02.015.

- Mills S, Torrance N, Smith BH. Identification and management of chronic pain in primary care: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(2):22. doi:10.1007/s11920-015-0659-9.

- Gan TJ, Habib AS, Miller TE, White W, Apfelbaum JL. Incidence, patient satisfaction, and perceptions of post-surgical pain: results from a US national survey. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(1):149–60. doi:10.1185/03007995.2013.860019.

- Gan TJ. Poorly controlled postoperative pain: prevalence, consequences, and prevention. J Pain Res. 2017;10:2287–98. doi:10.2147/JPR.S144066.

- Mann EG, VanDenKerkhof EG, Johnson A, Gilron I. Help-seeking behavior among community-dwelling adults with chronic pain. Can J Pain. 2019;3(1):8–19. doi:10.1080/24740527.2019.1570095.

- Webster F, Rice K, Katz J, Bhattacharyya O, Dale C, Upshur R. An ethnography of chronic pain management in primary care: the social organization of physicians’ work in the midst of the opioid crisis. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(5):e0215148. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0215148.

- Craig KD, Holmes C, Hudspith M, Moor G, Moosa-Mitha M, Varcoe C, Wallace B. Pain in persons who are marginalized by social conditions. Pain. 2020;161(2):261–65. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001719.

- Levinson W, Wong BM. Aligning continuing professional development with quality improvement. CMAJ. 2021;193(18):E647–E648. doi:10.1503/cmaj.202797.

- Carlin L, Zhao J, Dubin R, Taenzer P, Sidrak H, Furlan A. Project ECHO telementoring intervention for managing chronic pain in primary care: insights from a qualitative study. Pain Med Malden Mass. 2018;19(6):1140–46. doi:10.1093/pm/pnx233.

- Fishman SM, Young HM, Lucas Arwood E, Chou R, Herr K, Murinson BB, Watt-Watson J, Carr DB, Gordon DB, Stevens BJ, et al. Core competencies for pain management: results of an interprofessional consensus summit. Pain Med Malden Mass. 2013;14(7):971–81. doi:10.1111/pme.12107.

- Pott O, Blanshan M, AS HKM, Baasch Thomas BL, Cook DA. What influences choice of continuing medical education modalities and providers? A national survey of U.S. physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2021;96(1):93–100. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003758.

- Price S, Reichert C. The importance of continuing professional development to career satisfaction and patient care: meeting the needs of novice to mid- to late-career nurses throughout their career span. Adm Sci. 2017;7(2):17. doi:10.3390/admsci7020017.

- University of Toronto Centre for the Study of Pain. [ Accessed 2022 February 2]. http://sites.utoronto.ca/pain/research/interfaculty-curriculum.html

- Bolarinwa OA. Principles and methods of validity and reliability testing of questionnaires used in social and health science researches. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2015;22(4):195–201. doi:10.4103/1117-1936.173959.

- Desimone LM, Le Floch KC. Are we asking the right questions? Using cognitive interviews to improve surveys in education research. Educ Eval Policy Anal. 2004;26(1):1–22. doi:10.3102/01623737026001001.

- SurveyMonkey: the world’s most popular free online survey tool. SurveyMonkey. [ Accessed 2022 June 1]. https://www.surveymonkey.com/

- Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: the tailored design method, 4th Edition | Wiley. 4th ed. Hoboken (New Jersey): Wiley; 2014.

- Sharma A, Minh Duc NT, Luu Lam Thang T, Nam NH, Ng SJ, Abbas KS, Huy NT, Marušić A, Paul CL, Kwok J, et al. A consensus-based checklist for reporting of survey studies (CROSS). J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(10):3179–87. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-06737-1.

- Health Canada. Canadian pain task force report: march 2021. Published May 5, 2021. [ Accessed 2022 February 2]. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/about-health-canada/public-engagement/external-advisory-bodies/canadian-pain-task-force/report-2021.html

- Johnson M, Collett B, Castro-Lopes JM. The challenges of pain management in primary care: a pan-European survey. J Pain Res. 2013;6:393–401. doi:10.2147/JPR.S41883.

- Smith BH, Hébert HL, Veluchamy A. Neuropathic pain in the community: prevalence, impact, and risk factors. PAIN. 2020;161(Supplement 1):S127. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001824.

- Smith BH, Torrance N, Bennett MI, Lee AJ. Health and quality of life associated with chronic pain of predominantly neuropathic origin in the community. Clin J Pain. 2007;23(2):143–49. doi:10.1097/01.ajp.0000210956.31997.89.

- Mbrah AK, Nunes AP, Hume AL, Zhao D, Jesdale BM, Bova C, Lapane KL. Prevalence and treatment of neuropathic pain diagnoses among U.S. nursing home residents. Pain. Published online October 26, 2021;163(7):1370–77. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002525

- Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, McNicol E, Baron R, Dworkin RH, Gilron I, Haanpää M, Hansson P, Jensen TS, et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: systematic review, meta-analysis and updated NeuPSIG recommendations. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(2):162–73. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70251-0.

- Rice K, Ryu JE, Whitehead C, Katz J, Webster F. Medical trainees’ experiences of treating people with chronic pain: a lost opportunity for medical education. Acad Med. 2018;93(5):775–80. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002053.

- Kamper SJ, Henschke N, Hestbaek L, Dunn KM, Williams CM. Musculoskeletal pain in children and adolescents. Braz J Phys Ther. 2016;20(3):275–84. doi:10.1590/bjpt-rbf.2014.0149.

- Raymond M, Marsicovetere P, DeShaney K. Diagnosing and managing acute abdominal pain in children. JAAPA Off J Am Acad Physician Assist. 2022;35(1):16–20. doi:10.1097/01.JAA.0000803624.08871.5f.

- Korterink JJ, Diederen K, Benninga MA, Tabbers MM. Epidemiology of pediatric functional abdominal pain disorders: a Meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(5):e0126982. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0126982.

- Hassan S, Stevens B, Watt-Watson J, Switzer-McIntyre S, Flannery J, Furlan A. Development and initial evaluation of psychometric properties of a Pain Competence Assessment Tool (PCAT). J Pain. 2022;23(3):398–410. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2021.09.002.

- IASP Interprofessional Pain Curriculum Outline. International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). [ Accessed 2022 February 2]. https://www.iasp-pain.org/education/curricula/iasp-interprofessional-pain-curriculum-outline/

- Lockyer J, Bursey F, Richardson D, Frank JR, Snell L, Campbell C. Competency-based medical education and continuing professional development: a conceptualization for change. Med Teach. 2017;39(6):617–22. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2017.1315064.

- Longtin C, Décary S, Cook CE, Tousignant-Laflamme Y. What does it take to facilitate the integration of clinical practice guidelines for the management of low back pain into practice? Part 2: a strategic plan to activate dissemination. Pain Pract Off J World Inst Pain. 2022;22(1):107–12. doi:10.1111/papr.13032.

- Cervero RM, Gaines JK. The impact of CME on physician performance and patient health outcomes: an updated synthesis of systematic reviews. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2015;35(2):131–38. doi:10.1002/chp.21290.

- DiDiodato G, DiDiodato JA, McKee AS. The research activities of Ontario’s large community acute care hospitals: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):566. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2517-4.

- Choinière M, Peng P, Gilron I, Buckley N, Williamson O, Janelle-Montcalm A, Baerg K, Boulanger A, Di Renna T, Finley GA, et al. Accessing care in multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities continues to be a challenge in Canada. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2020;45(12):943–48. doi:10.1136/rapm-2020-101935.

- Ge E, Su M, Zhao R, Huang Z, Shan Y, Wei X. Geographical disparities in access to hospital care in Ontario, Canada: a spatial coverage modelling approach. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1):e041474. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041474.

- Hughes E. Nurses’ perceptions of continuing professional development. Nurs Stand R Coll Nurs G B 1987. 2005;19(43):41–49. doi:10.7748/ns2005.07.19.43.41.c3904.

- King R, Taylor B, Talpur A, Jackson C, Manley K, Ashby N, Tod A, Ryan T, Wood E, Senek M, et al. Factors that optimise the impact of continuing professional development in nursing: a rapid evidence review. Nurse Educ Today. 2021;98:104652. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104652.

- Manley K, Jackson C. The Venus model for integrating practitioner-led workforce transformation and complex change across the health care system. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26(2):622–34. doi:10.1111/jep.13377.

- Remmel A. Scientists want virtual meetings to stay after the COVID pandemic. Nature. 2021;591(7849):185–86. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-00513-1.

- Lewis KO, Cidon MJ, Seto TL, Chen H, Mahan JD. Leveraging e-learning in medical education. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2014;44(6):150–63. doi:10.1016/j.cppeds.2014.01.004.