ABSTRACT

Background

Craniofacial pain (CFP) poses a burden on patients and health care systems. It is hypothesized that ketamine, an N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, can reverse central sensitization associated with causation and propagation of CFP. This systematic review aims to assess the role of ketamine for CFP.

Methods

Databases were searched for studies published up to September 26, 2022, investigating the efficacy of ketamine for adults with CFP. Primary outcome was the change in pain intensity at 60 min postintervention. Two reviewers screened and extracted data. Registration with PROSPERO was performed (CRD42020178649).

Results

Twenty papers (six randomized controlled trials [RCTs], 14 observational studies) including 670 patients were identified. Substantial heterogeneity in terms of study design, population, dose, route of administration, treatment duration, and follow-up was noted. Bolus dose ranged from 0.2–0.3 mg/kg (intravenous) to 0.4 mg/kg (intramuscular) to 0.25–0.75 mg/kg (intranasal). Ketamine infusions (0.1–1 mg/kg/h) were given over various durations. Follow-up was short in RCTs (from 60 min to 72 h) but longer in observational studies (up to 18 months). Ketamine by bolus treatment failed to reduce migraine intensity but had an effect by reducing intensity of aura, cluster headache (CH), and trigeminal neuralgia. Prolonged ketamine infusions showed sustainable reduction of migraine intensity and frequency of CH attacks, but the quality of the evidence is low.

Conclusion

Current evidence remains conflicting on the efficacy of ketamine for CFP owing to low quality and heterogeneity across studies. Ketamine infusions are suggested to provide sustained improvement, possibly because of prolonged duration and higher dosage of administration. RCTs should focus on the dose–response relationship of prolonged ketamine infusions on CFP.

RÉSUMÉ

Contexte: La douleur crânio-faciale représente un fardeau pour les patients et les systèmes de soins de santé. L’hypothèse a été émise que la kétamine, un antagoniste du récepteur N-méthyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), peut inverser la sensibilisation centrale associée à la causalité et à la propagation de la douleur crânio-faciale. Cette revue systématique vise à évaluer le rôle de la kétamine dans la douleur crânio-faciale.

Méthodes: Les bases de données ont été consultées pour y repérer les études publiées jusqu’au 26 septembre 2022 qui portaient sur l’efficacité de la kétamine chez les adultes atteints de douleur crânio-faciale. Le critère de jugement principal était le changement de l’intensité de la douleur 60 minutes après l’intervention. Deux évaluateurs ont examiné et extrait les données. L’inscription auprès de PROSPERO a été réalisée (CRD42020178649).

Résultats: Vingt articles (six essais contrôlés randomisés, 14 études observationnelles) incluant 670 patients ont été répertoriées. Une hétérogénéité considérable en matière de devis d’étude, de population, de dose, de voie d’administration, de durée du traitement et de suivi a été notée. La dose bolus variait de 0,2 à 0,3 mg/kg (voie intraveineuse) à 0,4 mg/kg (voie intramusculaire) et à 0,25-0,75 mg/kg (voie intranasale). Les perfusions de kétamine (0,1-1 mg/kg/h) étaient administrées sur différentes durées. Le suivi était court dans les études contrôllées randomisées (de 60 min à 72 h) mais plus long dans les études observationnelles (jusqu’à 18 mois). La kétamine par traitement bolus n’a pas réussi à réduire l’intensité de la migraine mais a eu un effet en réduisant l’intensité de l’aura, la céphalée en grappe et la névralgie du trijumeau. Les perfusions de kétamine prolongées ont montré une réduction durable de l’intensité de la migraine et la fréquence des crises de CH, mais la qualité des données probantes est faible.

Conclusions: Les données probantes actuelles demeurent contradictoires sur l’efficacité de la kétamine pour la douleur crânio-faciale en raison de la faible qualité et de l’hétérogénéité des études. Il est suggéré que les perfusions de kétamine procurent une amélioration soutenue, peut-être en raison de leur durée prolongée et de leur posologie d’administration plus élevée. Les essais contrôlés randomisés devraient se concentrer sur la relation dose-réponse des perfusions prolongées de kétamine sur la douleur crâno-faciale.

Introduction

Description of the Condition

Craniofacial pain (CFP) is common, with a lifelong incidence of 96%, and poses a significant burden on patients’ quality of life and the health care system.Citation1–4 Despite the availability of a variety of treatment modalities, many patients experience unsatisfactory pain relief and/or adverse effects from existing pharmacological interventions or cannot afford expensive treatments.Citation3,Citation5

It is hypothesized that CFP syndromes share a mechanism of central sensitization as a cause for pain. Central sensitization is characterized by an increase in neuronal excitability secondary to repetitive stimulation of the nociceptive C-fibers in the trigeminocervical complex and the brain, which is mediated by the activation of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors.Citation6–8 Activation of the NMDA receptors plays a major role in ongoing pain, opioid-induced hyperalgesia, and mood dysregulation, and it is considered the principal receptor involved in the phenomena of central sensitization and “wind-up,” resulting in hyperalgesia, allodynia, and spontaneous pain.Citation9,Citation10 This central sensitization can be reversed by blockade of these receptors by noncompetitive NMDA antagonists such as ketamine.Citation6,Citation7,Citation10,Citation11

Ketamine is a chemical derivative of phencyclidine with analgesic, dissociative, and psychomimetic properties.Citation12 Its primary mechanism of action is as a noncompetitive antagonist of the NMDA receptors residing in the central nervous system.Citation10,Citation13 Ketamine is a versatile drug that can be administered via many routes, including intravenous (IV) and intramuscular (IM) but also oral, intranasal, inhalation, topical, and rectal, rendering it an easy agent for out-of-hospital care. It can be given as a single bolus or infusion or a combination of both. Although its potency is comparable to that of opioids, ketamine has a much better safety profile and is less likely to lead to development of tolerance. Possible adverse effects of ketamine include hypertension and tachycardia, hallucinations, and hepatic toxicity with chronic exposure.Citation14

Ketamine has successfully been used in the treatment of complex chronic pain states such as complex regional pain syndrome and neuropathic pain,Citation11 but its therapeutic role in CFP has not been completely established. Therefore, the objective of this systematic review was to evaluate the efficacy of ketamine for the treatment of CFP and examine its effects on pain-associated domains.

Methods

Registration

This systematic review was conducted according to the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration and was reported as per the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. The protocol of this systematic review was registered with PROSPERO (ID CRD42020178649).

Data Sources and Search Strategy

We conducted a comprehensive search of the literature from inception to February 1, 2020. Updated searches were conducted over the same databases and clinical trial registries on November 3, 2020, and September 26, 2022, with the assistance of a medical information specialist (M.E.).

The following databases were searched: Embase (1947–), MEDLINE (1946–), MEDLINE ePubs, In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2005–), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (1991–), and PubMed-NOT-MEDLINE. We also searched Web of Science Core Collection (1900–; Clarivate Analytics) and Scopus (1960–; Elsevier). Clinical trial registries, ClinicalTrials.Gov, and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform were searched to identify trials.

We restricted our search to human subjects with moderate-to-severe pain. For Embase, MEDLINE, Cochrane CENTRAL, and Scopus, both controlled vocabulary terms (Embase-Emtree; MEDLINE-MeSH) and text word searching were conducted for each of the following segments: (“ketamine” or related synonyms) AND (“headache” or “migraine” or “cluster headache” or “facial pain” or “short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT)” or “short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with cranial autonomic symptoms (SUNA)” or “trigeminal neuralgia” or “trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia (TAC)” or “occipital neuralgia” or “cephalalgia” or other related terms). The most recent Ovid Medline search strategy and the MEDLINE search strategy are provided in Appendix 1.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

The studies were screened for eligibility based on title, abstract, and subsequently full manuscript. Studies were included if they met the selection criteria as listed below.

Population

This review included studies of human subjects ≥18 years of age with a CFP (primary headache or neuropathic facial pain) diagnosis that fit the criteria of the International Classification of Headache Disorders third edition.Citation15 Studies that investigated effects of ketamine on a mixed population of patients with pain for which data on CFP could not be extracted separately were excluded. No restrictions were put in terms of chronicity, frequency, or duration of the attack. An initial restriction of including participants with only moderate-to-severe pain was waived at the start of the title screening process because of fear of selection bias.

Intervention

The intervention was defined as bolus/infusion administration of ketamine of any dose or administration type (IV, IM, subcutaneous, intranasal, epidural, sublingual, rectal, oral). Studies in a perioperative setting and/or with mixed combinations of ketamine with another drug were excluded. There was no limit on the duration of treatment or number of treatments.

Comparator

Comparators included no treatment, placebo treatment, or conventional medical management, which could include pharmacological, physical, psychological, and/or interventional therapies.

Outcome

The primary outcome was the change in intensity of pain assessed on a numeric rating scale (NRS)/visual analog scale (VAS) at 60 min after the intervention. Secondary outcomes included (1) positive response (defined as a reduction in pain score by ≥30% from baseline at 60 min after the intervention) and effect of ketamine infusion on (2) pain intensity (NRS/VAS) at any time after the intervention up to 6 months posttreatment, (3) adverse effects, (4) functional outcome, (5) quality of life, (6) mood, and (7) patient satisfaction. The threshold of >30% pain relief has been demonstrated to constitute clinically meaningful improvement.Citation16 The initial restriction of 6 months’ follow-up time was extended to 18 months at the time of data collection.

Study Selection Process

All citations were independently screened on title and abstract for eligibility by two reviewers (Y.H. and P.K.) as per the inclusion criteria. CovidenceCitation17 was used as a systematic review management tool. Papers of interest were then full-text screened. Of the selected papers, data were independently extracted by two reviewers (T.M. and M.P.). Any disagreement was resolved through discussion with the senior author (P.K.).

Data Extraction

The reference data, populations, and outcomes were extracted from the articles into prespecified tables on a standardized data collection form in Word that was pilot tested before use. Extracted data for each study included general characteristics (publication year, design, number of arms), patient characteristics (number, demographics, and sample size), clinical information (diagnosis, duration, pain intensity), details of intervention and comparator (dose and administration regimen), data on primary and secondary outcomes of interest, follow-up time points, and adverse effects.

Assessment of Quality as Risk of Bias

Two review authors (Y.H. and M.P.) independently assessed the risk of bias for randomized controlled trials using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool 2.0.Citation18 Any disagreement was resolved through discussion with the senior author (P.K.). The Robins-I was used to assess the risk of bias in observational studies.Citation19 For case reports/case series, the Quality Appraisal Tool for Case Series was used.Citation20

Data Synthesis and Analysis

We narratively synthesized the characteristics of all studies that met inclusion criteria. Study characteristics and treatment details were summarized. For continuous data, means (or medians) and standard deviations (or interquartile ranges or ranges) were extracted. No meta-analysis was performed because of the heterogeneity of data, low quality, and small sample sizes of included studies.

Results

Search Results

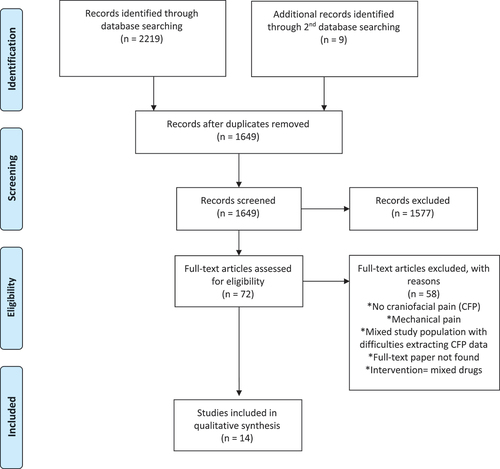

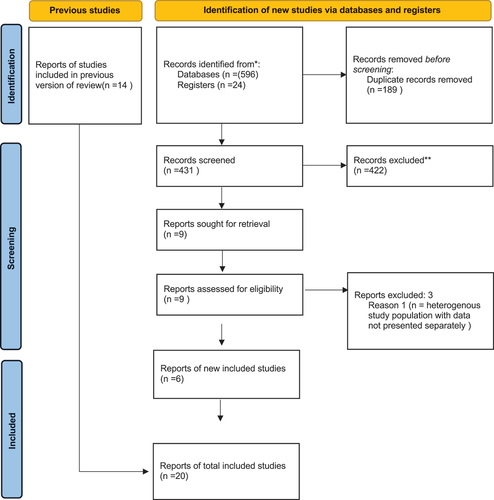

A total of 2080 unique articles were retrieved from all searches, of which 1956 were excluded at the screening stage. During the initial search, 72 full texts were assessed for eligibility, of which 14 papers were deemed to meet all eligibility criteria for inclusion in this review (). During the following searches, 9 additional full texts were selected and assessed, of which 6 papers met all eligibility criteria for inclusion in this review ().

The 20 papers included in our review, reporting on 670 patients in total, included the following studies: Six randomized controlled trials (RCTs)Citation21–26 and 14 observational studies, of which 5 were prospective cohort studies,Citation27–31 3 were retrospective cohort studies,Citation32–34 3 were case series,Citation35–37 and 3 were case reports, were includedCitation38–40 ().

Table 1. Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review: participants, interventions, comparators, and outcome measures.

Table 2. Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review: Follow-up times, outcomes, and adverse effects.

Risk of Bias for Included Studies

The results for assessment of the risk of bias for the included RCTs are listed in Appendix 3. The overall risk of bias was deemed to have “some concerns” for two of the RCTsCitation24,Citation25 and “high risk of bias” for the remaining four RCTs.Citation21–23,Citation26 The risk of bias assessment of the included nonrandomized trials showed one study of low risk of bias,Citation30 one study of moderate risk of bias,Citation33 two studies deemed to have a serious risk for bias,Citation27,Citation32,Citation34 and two studies that demonstrated a critical risk of biasCitation28,Citation29,Citation31 (Appendix 4). The quality of the two case series was moderateCitation35,Citation36 and one was of high qualityCitation37 (Appendix 5).

Study Characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the 670 patients reported in the 20 included studies are summarized in . The use of ketamine for the treatment of primary headache was discussed in 17 studies (n = 616), including 5 RCTsCitation22–26 and 12 observational studies (6 nonrandomized trialsCitation29–34 and 6 case series/case reports).Citation35–40 Three studies (n = 54) reported the use of ketamine for treatment of neuropathic facial pain, including 1 RCTCitation21 and 2 prospective observational studies.Citation27,Citation28

Primary Headaches

Demographics and Pain Profiles of Participants in the Included Studies

We found five RCTs including 299 patients with primary headaches: migraine, tension-type headaches, and cluster headaches (63% females, 18–65 years) ().Citation22–26 Baseline pain intensity ranged from VAS of 56/100 to 95/100.Citation22,Citation24–26

We found 12 observational studies including 317 patients (50% females) with the following diagnoses: chronic migraine (CM; n = 222), cluster headache (CH)–episodic (n = 17) or chronic (CCH; n = 57), short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT; n = 4), medication overuse headache (MOH; n = 37), and new daily persistent headache (NDPH; n = 17).Citation29–40 Baseline pain intensity was moderate to severe in all observational studies. The duration of headache history was only provided in 3 studies.Citation23,Citation30,Citation37

Details of the Ketamine Treatment

Route of Administration and Dosing

Treatment with a singleCitation23–26,Citation31 or doubleCitation22 or fiveCitation30 boluses of ketamine was investigated in seven papers. Five papers (three RCTs, one cohort study, one case series; n = 245) looked into the effect of and intranasal bolus of ketamine compared to midazolam,Citation23 diphenhydramine,Citation22 ketorolac,Citation26 or no comparator.Citation30,Citation35 Bolus dose ranged from 0.25 to 0.75 mg/kg. Ketamine was administered as an IV bolus in two RCTs.Citation24,Citation25 Bolus dose ranged from 0.2 to 0.3 mg/kg and comparators were placeboCitation25 or prochlorperazine with diphenhydramine.Citation24

The effect of IV ketamine infusions was reported in ten observational studies (including 283 patients).Citation29,Citation31–34,Citation37,Citation40 Patient population in these studies was mixed and included patients with CM and CH. Infusions were given over dosages ranging from 0.1 to 1 mg/kg/h over various durations (ranging from a single 1-h infusion up to infusions for up to 6 h on nine consecutive days). Two studies had a comparator (lidocaine).Citation31,Citation34

Duration of Follow-Up

The follow-up time in the RCTs ranged from 60 minCitation25,Citation26 to 72 h posttreatment,Citation22,Citation24 with one additional trial specifying only that follow-up occurred for six consecutive migraine attacks.Citation23 The follow-up time for the observational studies was longer, ranging from immediately posttreatment,Citation30,Citation34–36 to 1 week,Citation37 1 month,Citation31,Citation32 3 months,Citation33,Citation38–40 and 18 monthsCitation29 after treatment.

Outcome

Impact on Migraine Pain Intensity

Four studies (all RCTs) investigated the analgesic effect of ketamine bolus treatment on migraine intensity,Citation22,Citation24–26 and five studies (all observational studies) investigated ketamine infusions.Citation31–36

Of the four RCTs investigating the analgesic efficacy of ketamine bolus treatment, only one RCT demonstrated superiority of ketamine compared to the comparator (ketorolac), providing significant pain relief up to 2 h posttreatment.Citation26 The three other RCTs failed to demonstrate superiority of ketamine compared to placebo, metoclopramide, or midazolamCitation22,Citation23,Citation25 ().

In stark contrast, all of the five observational ketamine infusion studies (n = 233) reported significant pain improvement at the end of the infusion period.Citation31–34,Citation36 Infusions of solely ketamine were given for 8 hCitation36 to 5 days in a row.Citation32,Citation33 In two studies, the effect of multiday ketamine infusion was compared to multiday lidocaine infusion.Citation31,Citation34 In the studies with lidocaine as a comparator, both groups were associated with significant pain reduction at the end of the infusion as compared to baseline, although the difference between groups was significant in favor of lidocaine in one studyCitation34 and in favor of ketamine in the other study.Citation31

Only three out of five papers reported long-term outcomes. Two studies noted a positive effect up to 1Citation32 and 3 months.Citation33 In the third paper, patients had returned back to their baseline pain at 1-month follow-up.Citation31

Impact on Aura Attack during Migraine

Only one RCT investigated the effect of ketamine and midazolam on length and severity of aura compared to placebo.Citation23 The severity of the aura was significantly improved by ketamine compared to placebo. However, both agents were equally effective in reducing the median duration of the attack compared to placebo. In a case series of 11 patients with familial hemiplegic migraine treated with 25 mg intranasal ketamine, 5 patients experienced an improvement of aura duration and severity for all 14 attacks treated. Three patients experienced a return of aura symptoms after initial improvement.Citation35

Impact on Pain Relief and Attack Frequency of TAC Headaches

All seven studies including patients with TAC (n = 76) reported a resolution or reduction in the attack frequency after ketamine treatment. An immediate but short-lasting effect was noted after bolus treatmentCitation30 and an immediate to sustained effect was noted after ketamine infusion.Citation29,Citation34,Citation37–40 Patients were reported to have more than a 50% reduction in attack frequency for 6 weeksCitation38 to complete resolution of attacks for 6 weeksCitation34,Citation37,Citation38 up to 3 months.Citation39,Citation40

Effect on Pain-Associated Domains (Functional Outcome, Sleep, Quality of Life)

Only one RCT reported on the effect of ketamine on pain-associated domains. No significant difference in functional disability scores (rated on a 4-point scale), measured 30 min posttreatment, between the IV ketamine bolus and placebo groups was identified.Citation25

Patient Preference/Satisfaction

Only three papers reported on patient satisfaction and/or preference for ketamine versus the comparator using an NRS.Citation22,Citation24,Citation25 In only one study was a significant difference identified, in favor of prochlorperazine.Citation24

Impact of Ketamine on Intake of Pain Medication

A few studies commented on change in use of rescue medication during or following ketamine treatment. Although not statistically significant, two RCTs demonstrated that a smaller proportion of patients in the ketamine group needed rescue medication during the infusion compared to the comparator.Citation22,Citation25 Two case series mentioned a reduction in dose and/or discontinuation of analgesics following ketamine infusion, but further details were not provided.Citation38,Citation39

Adverse Effects and Complications of Ketamine Infusion

Approximately 70% of patients across all studies experienced side effects related to ketamine infusions; however, most were mild and resolved with decreased rate or ending the ketamine infusion. Side effects included dizziness, sedation, and blurred vision’ One patient’s ketamine infusion was stopped because the patient experienced suicidal thoughtsCitation32 and one patient preferred to stop ketamine because of the side effects.Citation33 One additional patient developed an asymptomatic elevation in liver enzymes.Citation32 None of the patients needed to be hospitalized because of intolerable side effects such as feelings of insobriety, confusion, nausea and vomiting, hallucinations, and tachycardia.

Facial Pain

Demographics and Pain Profiles of Participants in the Included Studies

Of three studies including 54 patients (85% females, 29–89 years), one crossover RCT (n = 30)Citation21 and one small observational study (n = 7)Citation28 examined the use of ketamine for patients with trigeminal neuropathy. Another small observational study (n = 17) included patients with neuropathic orofacial pain (not specified).Citation27 Baseline pain intensity was moderate to severeCitation21,Citation28 or not provided.Citation27 The duration of pain ranged from 6 months to 28 years.

Details and Outcome of Ketamine Treatment

In the three studies, all patients received a single bolus of ketamine 0.4 mg/kg. One study compared ketamine to IM pethidine 1 mg/kg.Citation21 In two studies, the bolus treatment was followed by 4 days of oral ketamine.Citation21,Citation27 Follow-up duration was short in these studies and ranged from 60 min after ketamine IM bolusCitation21,Citation27,Citation28 to 3 days after oral treatment.Citation21,Citation27 Ketamine demonstrated a significant immediate improvement of facial pain in two studies for the duration of follow-up (3 days).Citation21,Citation27 It was noted that those responding to IM ketamine also reported pain relief with oral ketamine.Citation21,Citation27 The adverse events profile was similar as reported in the primary headache studies.

Discussion

Despite recent evolutions in pharmacological and interventional management of patients with CFP, many patients continue to experience a significant reduction in quality of life, thereby imposing a significant burden on the health care system. We therefore conducted this systematic review to evaluate the evidence on the role of ketamine for patients with headache and/or facial pain.

Impact on Headache and Facial Pain

Although we evaluated 5 RCTs and 12 observational studies, evidence remains conflicting on the efficacy of ketamine for treatment of primary headaches. This is likely due to the limited study quality, moderate to high risk of study bias, confounding and substantial heterogeneity across studies in terms of study design, patient populations, details of ketamine treatment, and (lack of) follow-up. Only 2 of the 5 RCTs demonstrated a significant immediate effect of ketamine on the intensity of pain and aura of migraine relief in the emergency room,Citation23,Citation26 and the remaining RCTs failed to demonstrate a significant effect of ketamine on headache intensity compared to various comparators. On the other hand, all observational studies demonstrated a significant reduction in migraine pain intensity and duration, as well as decreased frequency and intensity of CH attacks immediately postintervention that lasted for up to 3 months postinfusion. The difference in these findings may be explained as follows. First, it may be attributed to the shorter administration times and/or lower dose of ketamine bolus treatment in the RCTs, because nearly all observational studies explored single-/multiple-day ketamine infusions. The typical doses for chronic pain IV ketamine treatment are 0.2 to 0.75 mg/kg (bolus), 0.5 to 2 mg/kg/h (infusion), 0.1 to 0.5 mg/kg for IM administration, and 0.2 to 1 mg/kg for intranasal administration, which is higher than what was administrated in the RCTs.Citation10 A high dosage and extended administration (infusions) of ketamine have been associated with better pain relief in patients with chronic pain.Citation41 Similar conclusions were made in the consensus guidelines on the use of IV ketamine infusions for chronic pain.Citation10 Future research in patients with primary headache should therefore focus on investigating the effect of high-dose and repeated administration of ketamine in a randomized controlled setting. Second, most RCTs had a mixed patient population, including patients with acute and chronic headache of migraine, cluster, and MOH types, which increased study heterogeneity, potentially affecting the outcome. Lastly, the 5 papers that did show a positive outcome of ketamine bolus treatment investigated patients solely with TAC, and bolus treatment failed in studies on patients with chronic migraine. This difference in outcome could be explained by a difference in pathophysiology, where TAC is driven by changes in the sphenopalatine ganglion, which potentially is more susceptible for the ketamine effect.

The evidence on ketamine for neuropathic facial pain is scarce but appears promising. Intramuscular ketamine was associated with significant improvement in two out of three studies on patients with trigeminal neuropathy,Citation21 and a tendency for continued pain relief with oral ketamine after initial IV/IM treatment was also noted.Citation21,Citation27 This treatment option of oral ketamine should be further explored because this could be a valuable therapy for patients in remote areas with limited access to health care facilities.

Effect on Pain-Associated Domains

Although the International Classification of Headache Disorders third edition diagnostic criteria for CFP are widely accepted and recommended,Citation42 a majority of the papers did not mention use of this validated instrument for diagnosis. This is a weakness that needs to be addressed to avoid misclassification bias and improve generalizability of the study results. Though a handful of studies examined patient satisfaction/preference and the need for rescue medications, most papers in this review did not mention use of validated tools to evaluate the effect of ketamine on pain-associated domains (sleep, mood, quality of life) in addition to its analgesic efficacy. This is surprising because the importance of evaluating pain-related domains in clinical and research settings is established, and validated tools to evaluate these domains are available.Citation43 Ketamine has been demonstrated to have an effect on sleep and mood and could therefore potentially improve patients’ quality of life even if pain intensity is unchanged.Citation44,Citation45

Safety

It is widely accepted that ketamine is associated with adverse psychomimetic, cardiovascular, and gastrointestinal effects resulting from its activity on a variety of substrate receptors including NMDA, acetylcholine, opioid, monoamine, and histamine.Citation10 The incidence of reported ketamine-induced side effects in the included papers was high regardless of type of administration or dose and only included psychomimetic effects. Most side effects were mild and resolved after decreasing the dose or ending treatment. Although central nervous system effects appear to be dose dependent when ketamine is used in anesthetic doses, the evidence is not as clear for subanesthetic regimens, beyond a yet-to-be-determined threshold.Citation10 In our review, no clear difference was noted in the incidence of side effects when comparing high to low doses. Most patients experienced hallucinations, which resolved after cessation of treatment, and one patient experienced suicidal thoughts. Based on the America Psychiatric AssociationCitation44 guidelines on the use of ketamine, a history of psychosis is a contraindication for administration of subanesthetic IV ketamine.

Strengths and Limitations

We found one other systematic review on the efficacy of ketamine for headaches, with evidence found in RCTs that were primarily focused on bolus administration of ketamine for acute headache pain relief.Citation46 The authors concluded that the benefit of ketamine for headache treatment is unclear but that long-term follow-up and different ketamine dosages in patients with chronic pain should be explored. Therefore, our systematic review attempted to take a closer look at the larger amount of evidence in observational trials that focused on ketamine infusions. Our review demonstrated that prolonged ketamine infusions can indeed significantly and sustainably reduce migraine intensity and frequency of CH attacks. This provides promising evidence, and this temporal and dose-dependent relationship should be further explored in new high-quality trials. To our knowledge, no attempt has been made to systematically gather evidence regarding the effects of ketamine on facial pain.

This review has several limitations. Most of the studies included in this review reported observational data, with inherent high risk of confounding and bias. Further, the heterogeneity across papers was substantial, with large differences in dosing, duration and route of administration, and comparators, which made comparison challenging and precluded a meta-analysis. Lastly, this review did not assess the long-term benefits and harms of ketamine for the treatment of CFP owing to lack of data in the literature.

A high-quality placebo-controlled RCT investigating the effect and safety of high-dose and/or prolonged ketamine infusion treatment on refractory headache pain and pain-associated domains would be the logical next step to investigate ketamine’s potential in the treatment of CFP. Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses of this evidence show that infusions of ketamine 1 mg/kg/h are associated with greater and sustained pain relief compared to one-off bolus and low-dose infusion regimens.Citation10 However, adverse effects of ketamine are common and could limit dose escalation, and the potential long-term risks of repeated administration of high doses of ketamine need to be further investigated.

Conclusions

Current evidence on the efficacy of ketamine for treatment of CFP remains conflicting, precluding the ability to make any recommendations. This is likely due to the limited study quality, moderate to high risk of study bias, and substantial heterogeneity across studies in terms of study design, patient populations, details of ketamine treatment, and (lack of) follow-up. Ketamine bolus treatment showed significant reduction of migraine aura severity, TAC intensity and frequency, and trigeminal neuropathic pain but failed to reduce migraine intensity or duration. The included observational trials suggest that ketamine infusion treatment has an immediate and sustained benefit on headache pain intensity, possibly because of the prolonged duration of treatment and higher dose of administration. Most papers failed to evaluate the effect of ketamine on pain-associated domains. RCTs are required that focus on the dose–response relationship and immediate and long-term effects of prolonged ketamine treatment on CFP and pain-associated domains.

Authorship Statement

Study conception and design: YH and ME; drafting of the article: YH and MP; research into, design of, and execution of database search strategies: ME; management and curation of database results, write-up of search methodology; ME; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation: YH, TM, MP, PK; review and editing of manuscript: all authors.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (20.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (22.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (20.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (20.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (29.6 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (340.4 KB)Disclosure Statement

YH received the Early Career Investigator Pain Research Grant from the Canadian Pain Society for the KetHead study “A Multi-Center Randomized Controlled Trial of Efficacy and Safety of Intravenous Ketamine for Chronic Daily Headaches: The KetHead Study.” All other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/24740527.2023.2210167.

References

- Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Lipton RB, Scher AI, Steiner TJ, Zwart J-A. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:193–17. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01288.x.

- Ananthan S, Benoliel R. Chronic orofacial pain. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2020 Apr;127(4):575–88. doi:10.1007/s00702-020-02157-3.

- Burch RC, Loder S, Loder E, Smitherman TA. The prevalence and burden of migraine and severe headache in the United States: updated statistics from government health surveillance studies. Headache. 2015;55(1):21–34. doi:10.1111/head.12482.

- Stokes M, Becker WJ, Lipton RB, Sullivan SD, Wilcox TK, Wells L, Manack A, Proskorovsky I, Gladstone J, Buse DC, et al. Cost of health care among patients with chronic and episodic migraine in Canada and the USA: results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). Headache. 2011 Jul-Aug;51(7):1058–77. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01945.x.

- Bendtsen L, Zakrzewska JM, Heinskou TB, Hodaie M, Leal PRL, Nurmikko T, Obermann M, Cruccu G, Maarbjerg S. Advances in diagnosis, classification, pathophysiology, and management of trigeminal neuralgia. Lancet Neurol. 2020 Sep;19(9):784–96. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30233-7.

- Chichorro JG, Porreca F, Sessle B. Mechanisms of craniofacial pain. Cephalalgia. 2017 Jun;37(7):613–26. doi:10.1177/0333102417704187.

- Hoffmann J, Storer RJ, Park J-W, Goadsby PJ. N-Methyl-d-aspartate receptor open-channel blockers memantine and magnesium modulate nociceptive trigeminovascular neurotransmission in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2019;50:2847–59. doi:10.1111/ejn.14423.

- Hoffmann J, Baca SM, Akerman S. Neurovascular mechanisms of migraine and cluster headache. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2019 Apr;39(4):573–94. doi:10.1177/0271678X17733655.

- Cohen SP, Liao W, Gupta A, Plunkett A. Ketamine in pain management. Adv Psychosom Med. 2011;30:139–61.

- Cohen SP, Bhatia A, Bhaskar A, Schwenk ES, Wasan AD, Hurley RW, Viscusi ER, Narouze S, Davis FN, Ritchie EC, et al. Consensus guidelines on the use of intravenous ketamine infusions for chronic pain from the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, the American Academy of Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(5):521–46. doi:10.1097/AAP.0000000000000808.

- Orhurhu V, Orhurhu MS, Bhatia A, Cohen SP. Ketamine infusions for chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesth Analg. 2019;129:241–54. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000004185.

- Adams HA. Mechanisms of action of ketamine. Anaesthesiol Reanim. 1998;23:60–63.

- Orser BA, Pennefather PS, MacDonald JF. Multiple mechanisms of ketamine blockade of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:903–17. doi:10.1097/00000542-199704000-00021.

- Zanos P, Moaddel R, Morris PJ, Riggs LM, Highland JN, Georgiou P, Pereira EFR, Albuquerque EX, Thomas CJ, Zarate CA Jr, et al. Ketamine and ketamine metabolite pharmacology: insights into therapeutic mechanisms. Pharmacol Rev. 2018 Jul;70(3):621–60. doi:10.1124/pr.117.015198.

- Headache classification committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) the international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018 Jan;38(1):1–211. doi:10.1177/0333102417738202.

- Farrar JT, Young JP Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94:149–58. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00349-9.

- Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation. Melbourne, Australia. www.covidence.org.

- Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng H-Y, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi:10.1136/bmj.l4898.

- Sterne JAC, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savovic J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, Henry D, Altman DG, Ansari MT, Boutron I, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi:10.1136/bmj.i4919.

- Moga C, Guo B, Schopflocher D, Harstall C. Development of a quality appraisal tool for case series using a modified Delphi technique. Edmonton (Canada): Institute of Health Economics; 2012.

- Rabben T, Skjelbred P, Oye I. Prolonged analgesic effect of ketamine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor inhibitor, in patients with chronic pain. J Pharmaol Exp Ther. 1999;289:1060–66.

- Benish T, Villalobos D, Love S, Casmaer M, Hunter CJ, Summers SM, April MD. The THINK (Treatment of headache with intranasal ketamine) trial: a randomized controlled trial comparing intranasal ketamine with intravenous metoclopramide. J Emerg Med. 2019 Mar;56(3):248–57. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.12.007.

- Afridi SK, Giffin NJ, Kaube H, Goadsby PJ. A randomized controlled trial of intranasal ketamine in migraine with prolonged aura. Neurology. 2013;80:642–47. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182824e66.

- Zitek T, Gates M, Pitotti C, Bartlett A, Patel J, Rahbar A, Forred W, Sontgerath JS, Clark JM. A comparison of headache treatment in the emergency department: prochlorperazine versus ketamine. Ann Emerg Med. 2018 Mar;71(3):369–77. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.08.063.

- Etchinson A, Bos L, Ray M, McAllister K, Mohammed M, Park B, Phan A, Heitz C. Low-dose ketamine does not improve migraine in the emergency department: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. West J Emerg Med. 2018 Nov;19(6):952–60. doi:10.5811/westjem.2018.8.37875.

- Sarvari HR, Baigrezaii H, Nazarianpirdosti M, Meysami A, Safari-Faramani R. Comparison of the efficacy of intranasal ketamine versus intravenous ketorolac on acute non-traumatic headaches: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Head Face Med. 2022 Jan 3;18(1):1. doi:10.1186/s13005-021-00303-0.

- Rabben T, Øye I. Interindividual differences in the analgesic response to ketamine in chronic orofacial pain. Eur J Pain. 2001;5(3):233–40. doi:10.1053/eujp.2001.0232.

- Mathisen LC, Skjelbred P, Skoglund LA, Oye I. Effect of ketamine, an NMDA receptor inhibitor, in acute and chronic orofacial pain. Pain. 1995 May;61(2):215–20. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(94)00170-J.

- Granata L, Niebergall H, Langner R, Agosti R, Sakellaris L. Ketamin i. v. zur Behandlung von Clusterkopfschmerz: eine Beobachtungsstudie [Ketamine i. v. for the treatment of cluster headaches: an observational study]. Schmerz. 2016 Jun;30(3):286–88. German. doi:10.1007/s00482-016-0111-z. PMID: 27067225.

- Petersen AS, Pedersen AS, Barloese MCJ, Holm P, Pedersen O, Jensen RH, Snoer AH. Intranasal ketamine for acute cluster headache attacks-results from a proof-of-concept open-label trial. Headache. 2022 Jan;62(1):26–35. doi:10.1111/head.14220.

- Schwenk ES, Torjman MC, Moaddel R, Lovett J, Katz D, Denk W, Lauritsen C, Silberstein SD, Wainer IW. Ketamine for refractory chronic migraine: an observational pilot study and metabolite analysis. J Clin Pharmacol. 2021 Nov;61(11):1421–29. doi:10.1002/jcph.1920.

- Pomeroy JL, Marmura MJ, Nahas SJ, Viscusi ER. Ketamine infusions for treatment refractory headache. Headache. 2017;57:276–82. doi:10.1111/head.13013.

- Schwenk ES, Dayan AC, Rangavajjula A, Torjman MC, Hernandez MG, Lauritsen CG, Silberstein SD, Young W, Viscusi ER. Ketamine for refractory headache: a retrospective analysis. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018 Nov;43(8):875–79. doi:10.1097/AAP.0000000000000827.

- Ray JC, Cheng S, Tsan K, Hussain H, Stark RJ, Matharu MS. Intravenous lidocaine and ketamine infusions for headache disorders: a retrospective cohort study. Front Neurol. 2022 Mar;9(13):842082. doi:10.3389/fneur.2022.842082.

- Kaube H, Herzog J, Käufer T, Dichgans M, Diener HC. Aura in some patients with familial hemiplegic migraine can be stopped by intranasal ketamine. Neurology. 2000 Jul 12;55(1):139–41. doi:10.1212/wnl.55.1.139. PMID: 10891926.

- Lauritsen C, Mazuera S, Lipton RB, Ashina S. Intravenous ketamine for subacute treatment of refractory chronic migraine: a case series. J Headache Pain. 2016 Dec;17(1):106. doi:10.1186/s10194-016-0700-3.

- Moisset X, Giraud P, Meunier E, Condé S, Périé M, Picard P, Pereira B, Ciampi de Andrade D, Clavelou P, Dallel R. Ketamine-magnesium for refractory chronic cluster headache: a case series. Headache. 2020 Nov;60(10):2537–43. doi:10.1111/head.14005.

- Moisset X, Clavelou P, Lauxerois M, Dallel R, Picard P. Ketamine infusion combined with magnesium as a therapy for intractable chronic cluster headache: report of two cases. Headache. 2017 Sep;57(8):1261–64. doi:10.1111/head.13135.

- Aggarwal A. Ketamine as a potential option in the treatment of short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing. Natl Med J India. 2019 Mar-Apr;32(2):86–87. doi:10.4103/0970-258X.275347.

- Shiiba S, Sago T, Kawabata K. Pain relief in short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache with conjunctival injection and tearing syndrome with intravenous ketamine: a case report. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2021 Mar;30(1):35–38.

- Maher DP, Chen L, Mao J. Intravenous ketamine infusions for neuropathic pain management: a promising therapy in need of optimization. Anesth Analg. 2017;124:661–74. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000001787.

- Ashina S, Olesen J, Lipton RB. How well does the ICHD 3 (Beta) help in real-life migraine diagnosis and management? Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016 Dec;20(12):66. doi:10.1007/s11916-016-0599-z.

- Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Jensen MP, Katz NP, Kerns RD, Stucki G, Allen RR, Bellamy N, et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2005;113(1–2):9–19. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012.

- Sanacora G, Frye MA, McDonald W, Mathew SJ, Turner MS, Schatzberg AF, Summergrad P, Nemeroff CB, American Psychiatric Association (APA) Council of Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments. A consensus statement on the use of ketamine in the treatment of mood disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Apr 1;74(4):399–405. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0080.

- Song B, Zhu JC. Mechanisms of the rapid effects of ketamine on depression and sleep disturbances: a narrative review. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Dec;14(12):782457. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.782457.

- Chah N, Jones M, Milord S, Al-Eryani K, Enciso R. Efficacy of ketamine in the treatment of migraines and other unspecified primary headache disorders compared to placebo and other interventions: a systematic review. J Dent Anesth Pain Med. 2021 Oct;21(5):413–29. doi:10.17245/jdapm.2021.21.5.413.